#but at least we get to see queer representation on a larger scale

Text

hbo max, it's pride month now. surely as a gift for the gays you're going to announce the news of an ofmd season 2 renewal??

#not a big fan of rainbow capitalism honestly#but at least we get to see queer representation on a larger scale#and i am just THAT desperate to get a season 2#i need a season 2 or i don't know what i'm going to do#ofmd#our flag means death#our flag means gay#blackbonnet#gentlebeard#blackstede#edward teach#stede bonnet#lucius spriggs#jim jimenez#black pete#oluwande x jim#lucius x black pete#pride month#pride#lgbt#lgbtq#gay#enby#1k#2k#3k#5k

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tell Me How You Really Feel by Aminah Mae Safi - Book Review

9.5/10 ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️🌟

TWs: car accident, cursing, sexism, panic attacks, abandonment

(TWs are ranked in order of severity, please take them seriously!)

Summary

“The first time Sana Khan asked out a girl-Rachel Recht--it went so badly that she never did it again. Rachel is a film buff and aspiring director, and she's seen Carrie enough times to learn you can never trust cheerleaders (and beautiful people). Rachel was furious that Sana tried to prank her by asking her on a date.

But when it comes time for Rachel to cast her senior project, she realizes that there's no more perfect lead than Sana--the girl she's sneered at in the halls for the past three years. And poor Sana--she says yes. She never did really get over that first crush, even if Rachel can barely stand to be in the same room as her.

Told in alternative viewpoints and set against the backdrop of Los Angeles in the springtime, when the rainy season rolls in and the Santa Ana's can still blow--these two girls are about to learn that in the city of dreams, anything is possible--even love.”

TL;DR Tell Me How You Really Feel is an ode to romantic comedies, following two girls on opposite sides of the social scale as they work together to make a movie and try very hard not to fall in love. Cheerleader meets film nerd, enemies to lovers.

I found this book through one of those tik tok videos where someone is flinging books off a pile at light speed under a caption “queer SA (South Asian) books you need to read”. I absolutely love those videos, even though they test my screenshotting abilities.

It’s been a while since I updated this blog(?) and that’s because I’ve been very busy finishing out the school year and reading every gay book I could get my hands on over the course of pride month. I will be posting reviews of those books soon, but in a quick review so far this month I’ve read:

• Last Night At The Telegraph Club

• Unearthed (graphic novel)

• Café con Leche

• Eighty Days (graphic novel)

• Tell Me How You Really Feel (this review!)

• The Raven Cycle (yes all 4 books, no I will not be reviewing)

Honorable mention: All 50 episodes of The Untamed (SUCH a good cdrama) & Season 1 of Stranger Things

I’ve realized over the course of this book binge that I prefer my enemies to lovers to have good reasoning - or at least understandable reasoning on both sides. My favorite part is seeing how that can morph into love without either realizing until it’s too late *cue evil laughter*

Tell Me How You Really Feel does that perfectly. I especially loved how it was written - the characters were flawed, raw and dynamic, and the writing style reminded me of books by Nicola Yoon (The Sun is Also a Star, Everything Everything). The romance isn’t necessarily the focus - it’s shoved in on the shelf along with everything else happening in the characters lives. The story simply starts (ish) and ends with the life of their romance within that.

And because this is a gay high school romance between a cheerleader and a film nerd, of course there are a million movie references, from Pakeezah to Pretty in Pink.

Meena Kumari 😩🧎🏽♀️

But real quick, let’s talk

Representation

Sana Khan and Rachel Recht, the main characters, are both into women. Although their sexualities aren’t explicitly stated, this part is made very clear.

Sana is desi, and Persian and Indian if I remember correctly? Her family is very mixed and has a lot of languages (Bengali, Urdu, Arabic, Persian, French, etc). She is second-gen American, while I’m pretty sure Rachel is first-gen (at least on her mom’s side).

Rachel is Mexican and Jewish, and her family consists of just her and her father (and their larger community) in comparison to Sana’s many cousins and aunties/uncles. Her full name is Rachel Consuela Recht, which I’m guessing is to show her mixed cultures.

For Sana I can somewhat call this an own voices review on representation, but please keep in mind the Indian (and larger desi community) is not a monolith & we won’t all agree on my own interpretation.

What I really liked about representation for Sana and her family was it is very women-centric. Her grandmother, Mamani, is very clearly the matriarch, and Farrah, Sana’s mom, is a single mother working in the film industry. In western literature desi culture is typically portrayed as oppressing women, especially in Muslim households, but this stereotype is flipped on its head by Sana’s family. It also showed how within a religion certain family members can be more religious than others - Sana & her Mamani are more religious (praying regularly, not drinking, etc) while Farrah is less so - and there’s no negative connotation on it.

Rachel and Sana both engage in religious holidays over the course of the book (Norwuz for Sana, Passover for Rachel). Since I’m neither Muslim or Jewish, it was interesting to learn more about the holidays and how they’re celebrated.

Single parenting rep (Rachel raised by her dad, Sana raised by her mom) was also really good. As someone being raised by a single mom & at one point a single dad, the struggle is portrayed really well.

Finally, I love that Sana fills the character of pretty perfect Gilmore-girls-esque cheerleader. Brown women don’t often get to be portrayed as lovely and soft and also raw and real at the same time. It really hit my heart 💗 Sana’s features are seen as beautiful by everyone around her - like a commonly accepted fact. She’s the official “pretty girl” of her school - and so much more beneath that.

What I Loved:

Aside from the good rep, the way the book is written is just ✨ poetic ✨

“Sana smiled, and suddenly Rachel understood every stupid love poem comparing the beloved to the sun.”

HOW DO I RECOVER??

Mainly though, I think this book came at the right time for me. Sana’s situation was really relatable to me, and her storyline actually helped me figure out some stuff in my own life (no spoilers!)

If you’re worried about the future, or planning to become a doctor or lawyer - read this book.

I’m also a sucker for big movie style gestures so this was a plus. I could see how the book was going to end generally way before the end, and that made it more of a comfort read than an “intellectual” read. I loved the character development as well - some serious words of wisdom in there!

As someone who wants to go to college in LA, and can’t afford to visit, this is as close as it gets to seeing what life there is like for me 😂 I’m curious to see what those Santa Anas feel like!

Why I couldn’t give it a 10:

I wasn’t the biggest fan of Rachel’s character to be honest. She hated Sana so much at the beginning, for something that had happened in their freshman year (the story takes place in their senior year). I could understand animosity, but it was another level. It made me think Rachel had anger issues - she seemed really self pitying and insecure. Which would have been fine - I’m all for character development - if she had realized that. But Rachel never seemed to come to terms with the fact that she had treated Sana like sh*t at every turn for nearly 4 years. It’s not that they don’t fall in love (this is a love story) but she doesn’t really feel remorseful for how she acted.

On set, when she’s directing the crew, the way she treated them reminded me of Michael Scott from the Office 😭

I also wish there had been more focus on the other characters in the book. Farrah, Sana’s mom, and Daniel, Rachel’s dad, kind of felt like glorified plot devices, especially near the end. Same goes for Diesel, Sana’s so-called best friend. We don’t actually see a lot of their relationship aside from Diesel giving her rides from school and then playing video games with her. In the end, his purpose was also a little plot device-y, a little serving the main ship, etc.

I liked that Diesel subverted the dumb insensitive jock trope, but I would have loved to see more of him and Maddie (another cheerleader)!

^unrelated but I love this scene (very scary cheerleader)

Overall, the book was a satisfying beach read (as in, I literally read it on the beach). Feel good, decent character development (on Sana’s part), and it gave me something I’d really been searching for: an enemies to lovers story between queer women of color in high school. Like babe- this is my niche!!

And yes, I cried at the end.

I sincerely recommend to fans of:

The Sun is Also A Star

Everything Everything

Movies (if you’re a movie nerd, you’re going to get wayy more of these references than I did)

But I’m A Cheerleader (movie)

Sense 8 (show) especially if you like the wlw couple

Most of my reviews for this month are going to be LGBTQ+ stories between PoC 🏳️🌈 so stay tuned!

#book review#bipocbookstagram#poc books#booklr#diverse reads#lgbtq books#tell me how you really feel#aminah mae safi#lets go lesbians#everything everything#the sun is also a star#queer enemies to lovers#enemiestolovers#cheerleader#film nerd#happy pride 🌈#queer bipoc#queer desi

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

EPs: "we chose Netflix to explore things like sexuality" (nothing was explored or was explicit for even 2 seconds) "when they told us u cant kill Shiro, we knew we could push the reveal 4 later" (so nice of them to admit they stopped our rep just to be able to kill him) "when we found out about byg we knew we coulnt kill Shiro & we thought we'll find rep w another character. Then we learned we could go on w/ Shiro as the rep" (theres ANOTHER REP WE DIDNT GET?? Was it vague then erased? Whatt??)

I think these are two separate issues. One is related to who made VLD, and the other is related to the EPs’ ignorance of characterization. The second overlaps with a bunch of asks I’ve recently gotten about race and representation, so here I’m just keeping it to a general discussion of characterization, with Lance as example. And then about Shiro in particular, how the EPs’ statements reveal their lack of thought.

Behind the cut.

remember where these people came from

The team behind VLD is almost entirely formerly Nickelodeon. DreamWorks wanted to break into television on a much larger scale, and since they almost always promote from outside the company, they lured over Margie Cohn from her position as a Nick VP. As VP/exec levels tend to do, Cohn brought a bunch of people with her.

One of those was Mark Taylor, who’d been involved in both AtLA and LoK. Taylor, in turn, brought JDS, LM, and I think one or two of the other producers. Taylor also probably brought over Hamilton, Chan, and Hedrick, as known entities with proven track records.

These are people who — for for the last ten or more years — have swum in Nickelodeon’s considerably more conservative fishbowl. It’s entirely possible (given what people tell me about storylines in HTTYD, and DW’s open support of She-Ra) the former Nickelodeon team automatically downgraded DW’s “go ahead and explore these heavier/darker topics” to mean “maybe kinda mention in passing but don’t be too obvious about it.”

Now, to be fair, the EPs may have pushed for more LGBT+ rep, and their obstacle might not have been DW, but Taylor. It’d explain how the EPs could praise everyone (read: DreamWorks staff) as supportive, yet allso complain about pushback (read: Taylor’s Nickelodeon-influenced sensibilities). Two different parties were calling the shots.

It’s also possible what the EPs saw as ‘rep’ was still considerably toned-down from what DW execs (and the VAs) may’ve expected. After all, that one-minute scene in VLD might’ve required an act of god at Nickelodeon. VLD’s staff may have genuinely considered this scene landmark because even that tiny bit was far more than their previous employer would’ve allowed.

Cue the victory lap and excited chatter, and seeming blindness to Korra being long since surpassed by Steven Universe, Young Justice, Bob’s Burgers, Adventure Time, Gravity Falls, RWBY, Rick and Morty, Clarence, BoJack Horseman, Danger & Eggs, Big Mouth, and Summer Camp Island. Remember, it wasn’t until 2016 that Nickelodeon would have a married gay couple (in The Loud House), and they’re not even central characters. The VLD staff may’ve thought itself bold, and unprepared for the reality of modern (non-Nickelodeon) audience expectations.

No, I don’t think that absolves them. It just seems the most reasonable explanation. That is, short of seeing the EPs as so utterly cynical they’d pump up the audience for what amounted to a nothingburger in light of what else popular media now delivers.

and then there’s representation

VLD’s troubles can all be traced to one crucial detail: the EPs don’t understand that characters are the bedrock of stories. And as such, there are no shortcuts.

Ever had the misfortune to catch a home decorating show? Here we have a windowless basement: mock up a mantle from polystyrene, paint the walls gray, put up sconces with flickering lightbulbs… it’s still a basement. It’s just now desperately pretending to be something it isn’t. The bones of the structure are undeniably American Suburbia, not generic castle keep, and those bones are integral to how we experience the space.

The average person isn’t trained to be aware of those bones — the underlying architecture — and its subtle impact on our experience, just as most non-storytellers aren’t trained to see how and where and why characters create plot. I guarantee you, though, you will never mistake a late-century Kmart for the Centre Pompidou or the Forbidden City or Mount Vernon. Just as you would never mistake a beginner’s first novel for Lord of the Rings or Left Hand of Darkness.

That is, the dressed stone isn’t paint and plaster; it’s a core element informing (even dictating) height, width, and depth of a space. Characterization is the same: it must be structural. In turn, characters inform the breadth and depth of the story. If your characterization is shallow, wild swerves and dramatic reveals can make the story fun, but they will never make it deep.

I empathize with the (hopefully genuine) intent to avoid making Shiro’s sexuality a ‘reveal.’ The unfortunate truth is: waiting 60+ episodes to even mention in passing makes it a reveal. It wasn’t structural, or viewers would’ve been sensing it from the very beginning.

This isn’t a haircut or a pair of jeans. It’s a person’s identity, and that has crucial impact on hopes, fears, desires, and needs. It doesn’t start only once the audience is let in on the secret; it was always there. It should’ve informed the character’s actions and reactions all along.

If Lance is Cuban, and the story takes place in a quasi-future America, then to understand Lance’s perspective, we need to ask questions like: is Cuba still under embargo? Is it a free democracy now, or did Lance’s family flee at some point? Is he part of an exchange program, or is there a lottery that let him come to the US for his education? Did he leave his family behind? How young was he, when he left? What was his childhood like, and how does that differ from what he found in America? What was his parents’ relationship like, and how does that influence his expectations for friends and lovers?

Was he fluent in English when he arrived, or did he only become fluent later? Does his Spanish have a noticeable accent, and if so, has he felt isolated from other Latinx at school? Or is he the only Latino at the Garrison? Is he proud of his heritage, or ashamed of it? Did he get bullied for being foreign, and how did that change what he says/does? Even if America is joyfully multi-cultural, he’d still be an immigrant or foreigner, and that’s a different experience from a non-white community that’s multi-generation American. What was his impression of his new life? What compared favorably (or not) to his childhood?

It’s not just, “He’s a boy from Cuba.” You have to think about what it means to be ‘from Cuba’ and how this is different from, say, growing up next door to the Garrison (like Pidge probably did). If you put that much thought into it, if you talk to people who’ve lived that experience, if you push yourself to imagine as deeply as you can how Lance’s life would have shaped him?

By the time you’re done, Lance would never need to say a word.

His reactions, his assumptions, maybe a few mannerisms, his humor, a few throwaway comments about his family or things he did as a kid — and there would be Cubans in the audience going, “hey, wait a minute, he’s just like my cousin.” Or brother or uncle or friend. By the time someone asks at a panel? Half the audience would be saying, yeah, we were right, Lance is totally Cuban.

Or you don’t think about it, and you use stereotypes in hopes that’ll do the work for you. As @sjwwerewolf commented:

Man, I’m ready to rant about Voltron. I’m Cuban. Lance, oh boy, Lance. From season 1 on, he has been written as a huge stereotype. The flirtatious, passionate comic relief character who’s dumb. Like. He’s literally Antman’s sidekick. That character. All you need to make him a full caricature is like, “I have a gangster brother.“

The stereotype is a shortcut. It’s slapping on behaviors without thought for a real person’s experiences or perspectives. VLD is, sadly, full of them: the Latino (wannabe) lover, the big guy who likes food (with only the slightest twist to have him actually good at cooking), the boyish-girl who’s a brain and likes computers more than people, etc.

just pull shiro out of a hat

At some point early on, the EPs said (once again in an interview, not in the story) that VLD is a world without homophobia. The story itself contradicts that ideal, or at least, it emphasizes a certain level of heternormativity over an open embrace of diverse relationships. What’s in our face for six seasons is Lance’s lover-boy stereotype, Allura’s attraction to Lotor, Lotor’s attraction to Allura, Matt’s attraction to Allura, and so on… and the closest we get to anything resembling an alternate attraction is one blush from a servant in a flashback, and Kuron’s startled reaction to Keith’s return.

All VLD had to do was have Hunk mention his moms. Or Coran mention his late husband. Or Lance mention his sister’s wife. Something explicit to offset the heterosexual attractions going on. Frankly, for six seasons it was an open question whether homosexuality even existed in VLD: the absence of a negative is not proof of the presence of a positive.

That absence means we really have no idea how being queer in VLD’s world would affect a character — and it would, have no doubt. Our sexuality affects every single one of us; it’s just that straight people have the benefit of seeing the roadmap of their sexuality played out in a million books, movies, and television shows. If you haven’t given thought to whether this is also true in your world, then you don’t really know how a character could discover, define, and map their sexuality, or how they’d quantify or qualify relationships that overlap their sexual preferences. You don’t understand the structure.

That lack of thought means, nine times out of ten, the creator has said to themselves, “it’s easier to just say this character’s experience of their sexuality is exactly like the one I, as a straight person, vaguely recall having (that I never actually had to question because it was already mapped out for me, everywhere I looked).” That’s not a queer character. That’s a character with a label slapped on their forehead that says here be a queer character. It’s paint, because the structure underneath is straight person.

Which means that of course the EPs could consider making someone else “the rep,” because they really seem to believe this is as easy as removing the label from Shiro’s forehead and sticking it on someone else. And it’s not. People don’t work like that. Sexuality is no more a simple paint-job than race, gender, culture, or dis/ability. Each of these things is etched on our bones, literally or metaphorically, and that changes us all the way through.

The short version, then, is: no, we wouldn’t have gotten any other rep, just as we haven’t truly gotten any rep as VLD was delivered. Shiro has a label on his forehead, but unless and until the canonical story demonstrates this goes all the way down to his bones… he’s just a straight suburban basement with a mediocre paint job and some fake queer columns.

132 notes

·

View notes

Link

You finally need two hands to count all the current TV shows with Asian American protagonists. Fresh Off the Boat (ABC) and Master of None(Netflix) arrived with fanfare for breaking ground (though a third season of Aziz Ansari’s romantic comedy was uncertain even before the star’s current scandal), while Quantico (ABC) and Into the Badlands (AMC) keeping chugging along, and the comedy Brown Nation (Netflix) and children’s melodrama Andi Mack (Disney Channel) have yet to become blips on the mainstream pop cultural radar. So it’s a bit strange, and off-putting, that the latest series with an Asian lead—one of the most anticipated shows of the year, it so happens—isn’t being described as such. In fact, its network—once a standard-bearer for prestige TV’s lack of diversity—is highlighting the drama’s focus on queerness and homophobia—and by doing so largely erasing its main character’s racial identity, especially in the first half of his story.

The Assassination of Gianni Versace: American Crime Story isn’t about the titular victim but his killer: Andrew Cunanan, a San Diego native born to a Filipino father and an Italian American mother. Writer Tom Rob Smith adapted journalist Maureen Orth’s nonfiction account Vulgar Favors, structuring the episodes in reverse chronological order so we work backward from Versace’s murder. In a recent interview, Smith said of his source material that it “reads very much like an outsider commenting on a world of which they’re not part, and sometimes that can make you seem quite removed from it.” I agree with his assessment; Orth’s book includes lengthy and salacious discussions of Versace’s HIV status and the popularity of meth among gay communities. But Smith’s description could also be turned on The Assassination of Gianni Versace, which is a white writer’s dramatization of another white writer’s interpretation. American Crime Story’s first season, The People v. O.J. Simpson, tackled issues of both race and gender skillfully; there’s no reason why we should accept any less from its second.

The show’s Andrew, played by Darren Criss, does mention his father’s plantation in the Philippines early on. But between his pathological lying and that country’s colonial past, his race isn’t confirmed till about midway through the nine-hour season. A few character details here and there suggest Andrew’s racial self-hatred and the prevalence of anti-Asian racism within the gay community, but the relative sparseness of these implications is all the more noteworthy in contrast with the richly developed portrait of the decade’s homophobia.

Credit where it’s due, even if the bar for praise here is laughably low because Hollywood’s institutional aversion toward Asian stories and characters remains so entrenched: In casting Glee’s Criss (who played Blaine Anderson), Ryan Murphy hired a half-Filipino (if white-passing) actor to play the half-Filipino role of Andrew Cunanan. Criss is excellent, and in later episodes, the Philippines-born Broadway performer Jon Jon Briones is electrifying as Andrew’s father, the sociopathic Modesto, who teaches his favorite child all the wrong lessons about the American dream.

If The Assassination of Gianni Versace feels urgent as it revisits the stifling homophobia of the ’90s, it’s far less successful in reimagining Cunanan from a racialized point of view, at least in the first eight episodes. (The season finale was not provided to critics in advance.) It’s certainly not as if those racial and ethnic depictions of Cunanan don’t exist. In his analysis of the divergent foci of the mainstream American and Filipino American media narratives about Cunanan, scholar Allan Punzalan Isaac notes that the former wagged its tongue about his “deviant” sexuality (Tom Brokaw infamously referred to the killer as a “homicidal homosexual”), while consumers of the latter looked on with a mixture of “pleasure and horror.” The horror is understandable enough. The pleasure, perhaps, is easier to grasp when you’re part of a group whose presence and history are constantly made invisible by the larger American culture. “Perhaps [the Filipino American fascination with Cunanan] stemmed from a longing to be reflected in the small screen in this American media sensation,” Isaac wrote several years after Cunanan’s death. Filipinos preferred participation, he conjectures, in “any American drama, even for the wrong reasons.”

Nearly all of the eight Filipino American scholars, activists, and advocates I talked to for this story say that Cunanan has fallen out of popular Filipino American lore, just as he’s been forgotten by American pop culture until now. Professor Christine Bacareza Balance told me in an email interview that when she polled 40 or so students in a recent Filipino American Studies course, only one or two knew who Cunanan was. But among gay Filipino Americans, he remains something of a cult figure and for a few Filipino American writers, a literary muse. Isaac begins his seminal book about Filipino American identity, American Tropics, with a meditation on Cunanan’s incarnation of many of the concepts central to his subject: the possibility of “assimilation gone wrong,” the fear of rejection and the eagerness to belong, the embodiment of Filipino/American “mestizo” beauty standards, the corresponding ethnic ambiguity. (Isaac quotes a New York Times article describing Cunanan’s face as “so nondescript that it appears vaguely familiar to just about everyone.”) Paul Ocampo, a co-chair of the Lacuna Giving Circle, a philanthropic group that fosters leadership in LGBTQ Asian American communities, offers a more cynical interpretation: “There’s an aspect of the glitter and glitz of Hollywood to this story that attracts many in the Filipino American community more than the macabre.”

It’s important to remember that Cunanan murdered five people, apparently in cold blood. His victims deserve to be mourned. But in the absence of other well-known personages (or the inconspicuousness of many successful celebrities’—e.g., Bruno Mars’— Filipino-ness,), it’s perhaps inevitable that some Filipino Americans see or project certain facets of themselves in one of the very few Filipino Americans to appear on TV and on page 1, especially during that era. Ben de Guzman, a policy advocate in D.C., saw Cunanan on the news and thought, There but for the grace of God go I. “As a young, gay Filipino American man who was around his age when he was in the news,” de Guzman recalls via email, “I was forced to look at how the same forces of homophobia and racism that informed my life must have affected him too.”

The former party boy and escort remains a symbol of queer defiance for some in the gay Filipino American community. “Here was a gay Filipino man who seemed unapologetic and daring in his acceptance of his sexuality,” says Ocampo. “In this, he seemed to exude a self-possession that many people struggle with.” Balance says that the image of Cunanan as a “queer Asian/Filipino American on the warpath” “truly goes against many dominant representations within ‘mainstream’ U.S. media.” Isaac contrasts Cunanan’s narrative with the gay/bi film Call Me by Your Name, which he observes is “set outside the U.S., outside the AIDS scare, outside any class conflict—all part of the Cunanan spectacle.” Isaac seems to anticipate a reckoning as Cunanan’s story unfurls on the series: “How is this story of intergenerational sex, wealth, casual prostitution, and reckless living in the gay demimonde of the ’90s to be received in this age of domesticated gay marriage?”

And if Cunanan’s messy and unpredictable life story seems ripe for fictional inspiration, The Assassination of Gianni Versace certainly didn’t get there first. A decade after Cunanan’s death, novelist and playwright Jessica Hagedorn (a canonical Filipino American writer), along with songwriter Mark Bennett, launched in the killer’s hometown a workshop production of their musical Most Wanted, a thinly fictionalized version of Cunanan’s story that explores media sensationalism and marginalized individuals’ desperation to belong. Smaller-scale works like Regie Cabico’s poem “Love Letter From Andrew Cunanan,” Gina Apostol’s short story “Cunanan’s Wake,” and Jason Luz’s erotic short story “Scherzo for Cunanan” likewise attempt to humanize a murderer who, while deplorable for his actions and indisputably extreme in personality, almost certainly had some desires and experiences common to many Filipino Americans. None of these works add up to a complete portrait, or could. But created from Filipino American perspectives, they explore the aspects of Cunanan’s life that white America still isn’t fully grappling with.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

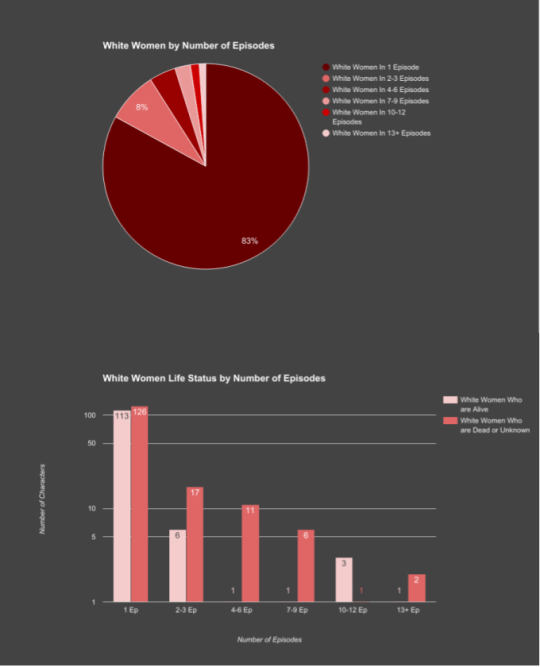

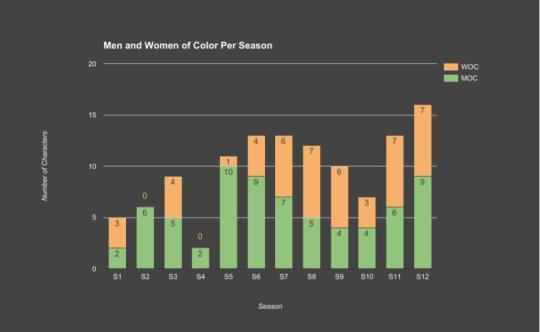

Does Supernatural Have a Problem with Representation and Diversity: A Mathematical Study

At the end of season 12, another fan favorite minority character, Eileen, was killed. This has come in a long line of favorite SPN characters who were people of color, women, lgbt+, and/or disabled being killed seemingly before their time. This, like other instances with such characters like Kevin and Charlie, sparked outrage from many fans. Some called the move sexist and ableist. Many said it was not inherently bad that Eileen died, but the way it was done was disgraceful and unworthy of such a beloved character. Other fans fought back against these claims, citing that everyone dies in supernatural and that no one should be immune. Besides, others said, with more representation, shouldn’t that mean more death?

But is there actually more representation? And is the death count equal? Are we being persuaded by biases and personal agendas?

After the season 12 finale, I’ve set out to see if there is a quantifiable difference in representation, huge differences that can be backed up by numbers and not just perception. Much of this is going to cover gender and race, as those are the easiest diversity angles to notice, but I will touch upon other areas. This information was not compiled to confirm any set of biases, but instead answer these questions at the heart of the debate and anger. Some of the information complied is quite obvious, but having set numbers is vital in these debates.

The rest, which is a lot, is under the cut:

A few notes/disclaimers before we begin:

All information is taken from seasons 1-12. When season 13 starts the numbers on here will, no doubt, have to change.

I have not counted every single character ever put on Supernatural ever, but instead elected to take my sample size from supernaturalwiki.com. I was originally going to pull a list from imdb, but I didn’t just want to record who was in what episode, but also who lives and who dies. To do this I would have had to closely watch the entire series over again. I have school and a job, so I have no time to actually do that. Instead, I collected my sample size from a site that has that information already on it. [I may end up redoing this using imdb and rewatching the show, but that will take months - if not years].

Jumping off of the first point, I have collected about 850 characters for this experiment that uses a lot of math and percentages. Obviously, these numbers are not entirely accurate since I couldn’t find everyone, but I highly doubt the percentages would greatly tip the scale in any minorities’ favor by a recount. This is just an example, but it’s a large sample size example that still reveals a lot.

Although many characters may not inherently be the same gender/race as their actor counterparts [see angels and demons] I am using the actor’s race and gender as the character’s. This is about on screen representation, so what you see is the most important. And, before anyone asks, no, i did not go up to every actor and asked them if they were a person of color or what gender the identify as; i guessed, but they were educated guesses. I followed this up until the show directly contradicted the casting. For instance: the actress playing the angel Benjamin is a black woman, but the character was presented as using he/him pronouns, so I listed Benjamin as a man of color.

In the cases of characters with multiple actors who fall into the same category (ie Meg’s two actresses are both white women) the character is counted once under that group (Meg is a white woman). In cases were the actors are in different categories (ie Raphael was portrayed by a black man and black woman), I count the character twice under each group (Raphael is counted once as a man of color and then again as a woman of color). I didn’t feel comfortable choosing one, and saying a character is 50% one thing and 50% another seemed more harmful that just counting them twice.

There are a few characters I couldn’t pin down as either gender, as either the wiki only used neutral pronouns with them or they were a straight up genderless creature, so I have a few characters in a gender neutral category. I have listed them, but they are by and large excluded from the majority of the analysis.

This is only about numbers and percentages, not how characters are portrayed on screen. The latter is more subjective and hard to discuss without bias getting involved. After all, I am one queer woman who can’t speak for everyone.

If you’d like to see my very annoying spreadsheets documenting all of this, click here: [x]. For larger versions of the graphs, you can find them here [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8]

And now onto the graphs:

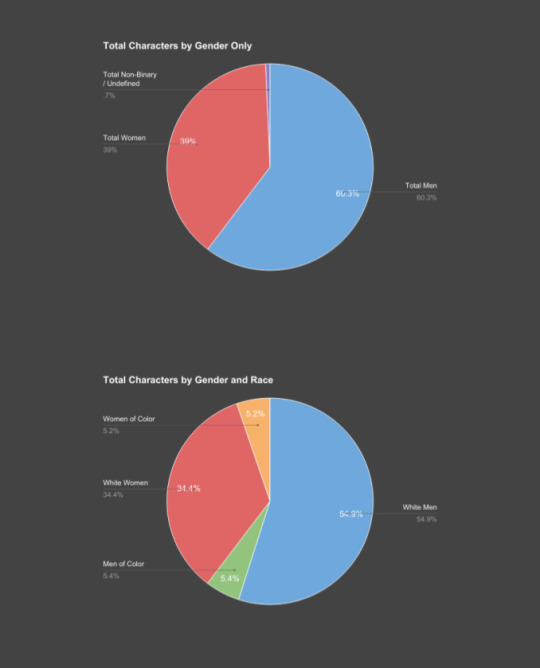

[Graph 1]

When you look at a strict gender breakdown of the characters, it comes out to be about 60% men and 40% women, which is, proportionally, a bit too uneven. The show should be hovering closer to the 50/50 mark. However, when race is added, the proportions get depressing. White men (blue )make up almost 55% of the total population of the show. People of color combined make up just over 10%, with each (moc are green and woc are orange) at about 5%.

[Graph 2]

The numbers get more interesting as we break it up into percent alive (the light colors) and precent dead or status unknown (the darker). While all groups have more people dead than alive, both groups of women have 43% of their population alive. White men have about 30% percent. Men of color are the most killed off group, at 20% still alive.

[Graph 3]

I further broke up the categories into how many episodes these characters have been in [this is not separated into alive or dead]. The brackets are 1 episode (top left), 2-3 episodes (top right), 4-6 episodes (middle left), 7-9 episodes (middle right), 10-12 episodes (bottom left), and 13+ episodes (bottom right). The columns go from left to right with white men, men of color, white women, and women of color.

NOTE: there are always far more characters in only one episode than any other grouping, and numbers of characters in each group constantly get lower on a bell curve. However, it is important to look at the percentages and comparable representation in each grouping.

As you can see, white people always have higher columns than people of color. You may also notice that at the 7-9 episode mark the graph loses columns. As of the season 12 finale, no woman of color has been in 7 episodes. While there is one man of color who has been in over 13+ episodes (Kevin), there are currently no men of color in 10-12.

I decided to break this up further into individual graphs for the different race/gender categories: first there are pie charts showing the group percentages in each number of episodes bracket . The second is a bar graph looking at the alive/dead status of characters in each number of episodes bracket.

[Graph 4]

There are so many men in 1 episode I had to log the graph. They currently have more characters in every category, save for 7-9 episodes where white women lead. Also, as of the end of season 12 there is at least one white man alive in each number of episodes bracket.

[Graph 5]

While they have far less characters in total than white men, white women do have a similar percentage breakdown.They do beat white men in the 7-9 episodes bracket, and like white men have at least one person who is alive in each group.

[Graph 6]

The graphs for men of color look very different than the other two. The do have a lower percentage of characters in only one episode, but that is mainly due to the lack of characters overall. Further, there are far more dead men of color than alive; the number of dead men of color in one episode is at a 78% death rate, far higher than any other group. They also don’t have any currently living characters past 2-3 episodes.

[Graph 7]

Women of color have, quantifiably, the worst record for representation in these categories. As I said earlier, no woman of color has been in at least 7 episodes. While they are tied for the group least killed off, they have so few characters introduced that it hardly makes a difference.

[Graph 8]

I also wanted to look at the number of people of color I could find in each season [once again i’d like to reiterate that this is based on the characters I could find from supernaturalwiki.com]. This bar graph has men of color in green and women of color in orange, tracking the number of each and both of them combined per season. While I give credit to season 12 for having the highest number of characters of color, that’s still at a lousy 16 characters, and when you can easily find over 100 characters per season, 16 is nothing to applaud. Further, if you count up all the characters listed in the graph, you reach 98. Not even 100 characters. That’s less than one new character of color being introduced every two episodes, which should be ridiculously easy to do. Supernatural still cannot do that.

I did also want to look at lgbt+ and disabled representation in the show.

NOTE: while characters like Hannah and Raphael have been in different gendered vessels, the show has never confirmed them as trans or non-binary, and I couldn’t find any human characters that were definitely not cis. I have decided that because of this lack of clear information not to collect stats on trans/non-binary characters on Supernatural, but that might speak for itself.

I found 17 characters who were confirmed in show to experience some form of same gender attraction. That makes up 2% of the show’s character population. Of these characters, 5 of them have been in multiple episodes. As of the end of season 12, 5 are dead (3 of the five in multiple episodes are dead). 5 of the 17 are people of color (only 1 of them has been in multiple episodes so far).

Tracking disability is harder, as many disabilities are invisible, so I stuck with characters with physical disabilities in multiple episodes, of which are only 3: Pamela Barnes, Bobby Singer (in season 5 he was in a wheelchair), and Eileen Leahy. They make up 0.35% of the show’s population. 2 of these characters were cured of there disability before their last episode on the show. All three are white. All three are dead.

So does Supernatural have a problem with representation and diversity?

Yes. It most certainly does. But not in the way people expect or often perceive.

Women aren’t being killed off at higher rates than man. Actually it’s quite the opposite. And white, straight, able-bodied women are pretty good in terms of representation.

The real problem is with the representation of people of color, disabled people, and the lgbt+ community.

And really, it’s not in the rates of them being killed off (well, men of color need to be killed off less). The problem lies in that these characters aren’t being introduced in the first place. It really doesn’t matter if 30% of white men are alive verse 43% of women of color when that comes out to 141 total living white men and 19 total living women of color. It’s not fair playing field.

Supernatural is a show set all across The United States of America and lives in it’s culture and lore. Nearly 40% of the United States is made up of people of color: black, asian, native, latinx, arab, etc. The show should reflect that. While the numbers on lgbt+ representation is still being disputed, the perception is that 4-10% of the population has same gender attraction and 0.6% are transgender. The show should reflect that. According to the US census, about 19% of the population has some sort of disability. The show should reflect that. It’s more than just adding in a few new characters of color and lgbt+ characters in season 12; tptb need to purposefully write in more diverse characters, cast diverse actors, and keep these characters around longer.

When people complain about Kevin, Charlie, Eileen, or others’ deaths in the show, this isn’t a matter of being sad a character is dead and not understanding how the supernatural death toll works. It’s being frustrated at a show which has so little representation and having one of the few characters in that category being ripped away from us, often in ways that are easily avoidable and/or disrespectful to the character. It’s characters being killed early on so we don’t have characters of color, lgbt+ characters, or disabled characters to go through the seasons with. It’s getting the bare minimum of representation and being told that’s enough and we shouldn’t complain any more.

There are people that aren’t bothered by the lack of diversity, and that’s fine. You’re in the full right not to care. But telling those who are frustrated and upset that they are overreacting, being childish, and are not true fans is beyond rude. It’s a silencing tactic, and it needs to stop.

No matter what side of the aisle you’re on, I hope people will read this and gain a better understanding of where Supernatural’s diversity is and why people may be mad. And, no matter what, the proportions tell us a change needs to happen.

382 notes

·

View notes

Text

Important reminders about identities in our communities and our fiction from @purplesaline (edited by me slightly, where indicated, to take out the personal context from which these are drawn).

“Lee made some really good points...

I’d also like to understand why [someone’s] identity grants [them] the right to be the arbiter of how a character should be portrayed but someone who is also non-binary and gay isn’t allowed. In many... posts that I’ve read regarding this subject it consistently comes across as... being dismissive of Cap’s identity and othering them from the community.

Additionally I’d like to know why [people] seem to think that if an autistic person asks for very specific things in a fic that is representative of their own lived experience it qualifies as bad representation because [someone else doesn’t] relate to it as an autistic person. Is it purely because the person doing the writing is neurotypical (or assumed to be)? I might be able to give more credit to that logic if they had done it of their own volition but they were essentially acting as a ghost writer.

It’s sounding an awful lot like [people] are allowed to demand people represent an identity [they] inhabit in a way that [they] relate to but that other people who share the same identity but have a different lived experience than [others] aren’t allowed to ask for that shared identity to mirror them. [People in our communities sometimes] say that these other representations are harmful and problematic because they don’t fall in line with [everyone’s] lived experiences but in disclaiming those representations [it is] harming people.

There is no single way to be any identity whether it’s a gender identity or a sexual orientation or neurodiversity or any other identity out there and because of that you’re going to find honest representations of that identity that can read as stereotypical because sometimes a persons lived experience of their identity falls in line with the stereotypes. It is unfair to invalidate their lived experience of their identity, it is harmful to invalidate their lived experience of their identity. What is problematic is not that that example of an identity exists but that there is not a more diverse sampling of the different ways people can inhabit the same identity.

And as a final point I have a HUGE problem with [people] deciding that just because characters have been portrayed as having sex in canon that it negates any chance of them being portrayed as Ace forever after. Having had sex doesn’t not disqualify someone from being Asexual. There are many reasons why someone who is asexual might have sex, not least of which is that they hadn’t come to the realization that they were asexual.

I think [people’s] arguments would hold more water if this was a discussion about the representation on the show itself rather than fan service fiction and would hold more water if the fanfic world was lacking in the very representation [some of us] claiming to be the ‘correct’ one but even if we just look at the microcosm of QCW’s fic library alone there are multiple fics representing each of a wide variety of identities. How [someone] can claim Identity Erasure when there are ten fics representing the canon identity to every one fic representing an alternate identity i really don’t understand.

One of the biggest draws for people about fanfic is the ability to change canon in a way that allows them to relate more completely to the characters and/or the show and to me that’s one of the best things about it. To try to police that? You come across as an elitist gatekeeper deciding who is or is not worthy of gaining entrance to the VIP club. Doesn’t the LGBTQIA2+ community deserve better than that? We’ve already got far too many cishet people telling us that we’re not worthy of being in mainstream society, let’s not mirror their actions in our own community.

While [people in our communities’] criticism of representation that [people] find harmful to [their] lived experience of [their] identity is certainly allowed, [the] policing of the way other people express and represent their own lived experiences of their identities (even if that is through a proxy) is unacceptable...”

and

“Okay so, first of all? Queer and Dyke? Some of us have gained a lot of empowerment from those words. I get that they are still being used as slurs and that they are really harmful to a lot of people still but this then becomes a case of “please don’t use that term in reference to me” and that’s cool but [people] don’t get to police how I, or anyone else, chooses to label themselves (or their incarnations of fictional characters). Sure [one] can point out that it’s possibly problematic because of the negativity still associated with it but it’s not a simple issue and a “You’re a bad person for using it how dare you” isn’t gonna cut it...

And look, I get that [people in our communities are] upset about what [they] see as stereotyping identities but the fact of the matter is that there are people who relate to those portrayals and by saying that it’s wrong to be portraying characters that way [people] are invalidating their experiences the same way [they] are feeling [their] own invalidated. The solution here isn’t a reductive one, but additive. Taking away representation because [not everyone] relate[s] to it is harmful to those who do relate to it. It’s definitely important to point out where representation is missing and that the experience portrayed isn’t indicative of everyone with that identity but instead of tearing someone down for trying and, if the comments left on these stories is any indication, succeeding in representing the experience for at least some, maybe try the approach of either a) asking for a representation that differs from what was already written or b) write [one’s] own. We need to avoid building ourselves up by tearing others down.

Now as for [people’s] point of a writer changing a canon lesbian into another identity if they don’t claim that identity themselves. That’s a complicated one. On one hand Cap is essentially acting as a proxy for a lot of people who want to see their head canon in writing and for various reasons can’t write it themselves and I see nothing wrong with that. These people trust Cap with their vision and from what I’ve seen most appreciate the results.

Changing the identity of a marginalized character is a bit trickier for sure. On one hand yah there aren’t enough canon lesbians on tv or in media in general but I don’t think fan service fiction is necessarily the place to be policing that. If for no other reason than [one] run[s] the risk of trampling over someone’s attempt to learn more about themselves through exploring these identities in fiction. I’m not trans and I’m not nb but I did go through a period in my life where I was seriously questioning my gender identity and writing about it was one of the ways I explored that about myself.

I think maybe the line there is the same one we tread with cultural appropriation. Changing a canon lesbian into a straight woman is blatantly problematic but changing them into an identity that is even more marginalized and has even less representation is maybe not as much of an issue. It’s human nature to want to take the thing we can most relate to and then change it so it reflects our experiences even more, which is why [we] see the gay characters being head canoned into ace characters etc.

Which isn’t to say that it’s not also problematic but I think that more than being problematic it’s just scary to see already slim representation being appropriated no matter who is doing it. I would honestly rather give someone who has no representation a portion of mine, however small mine may be, than them not having any at all especially knowing how much harder they would have to fight to claw anything away from the ‘mainstream’ than I would.

So yah, it’s not clear cut and there is no easy answer to that one but I’m certainly falling on the side of letting the even more marginalized appropriating canon lesbian characters and that it’s acceptable for someone to write outside their own identity especially if it’s fan service.

As for the pulse fic? Cap said they realized it was problematic and removed it which I think shows a great deal of character. Their intent for writing it in the first place though? Not off base. It’s natural for us to process grief through fiction, we do it all the time. Using a traumatic event in a story isn’t necessarily trivializing it, in fact it cam be incredibly helpful and healing for many people, author and readers alike. I read the fic in question and I didn’t see anything that stood out as being disrespectful. Obviously [people] saw differently and that dichotomy is going to echo on a larger scale as well and I think that this is another instance I prefer to err on the side of 'if it helps people then it’s acceptable’ and for those who would be harmed by it them we take the same action we would in other situations where content can be harmful like content or trigger warnings.”

#posting because i've been asked to by a person i love very much#i depersonalized it because i think it speaks to a larger trend in our communities to hurt each other and i think this can help us think#about ways to talk to each other about our differences and different needs and triggers#also damn your writing is beautiful#also i'm extending lots of love to everyone who's been part of this conversation but honestly right now i'm coping with a lot of family#things and i'm done responding to/posting to all this albeit important stuff because i've said what i want to say and this says things#better than i could anyway#sending love and respect to everyone#i will do better#thank you

72 notes

·

View notes