#g: 1809

Photo

566 days before yoongi is back

(keep exploring my drafts, this piece was laying since sept 2018)

#userbangtan#usersky#dailybts#yoonkooknetwork#bts#bangtan#bangtan boys#suga#min yoongi#yoongi#for you#no bangtan series#era: i need u#g: 1809#v: mv#japan edition#japan#bangtanarmynet#btsedit#bangtangif#big shushu

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

All About U

If you had a freeway billboard, what would it say?

If you wondered what happened to our main writer of Airbrushes & Airplanes, AlexAirLuna, he said he lost his password and left it at that. But can’t you easily…he left it at that. But…

Airtek Entertainment has the scoop on his current work.

https://genius.com/Ict-dj-lexo-all-about-u-lyrics

Alex AirLuna has been transcribing lyrics to the ICT…

View On WordPress

#alexairbrushluna#pearlsbeauty#all about u#Art#Attraction#bloganuary#bloganuary-2024-06#dailyprompt#dailyprompt-1809#G-Rated#ICT#inspiration#Inspired Creative Thinkers#Latin#music#poetry#writing#youtube

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hi hi!

Do we have any Jane Austen + Crowley interactions fic in this household?

Thanks and have a nice day ^^

We have a #jane austen tag, the last post on which features a couple. But here is a post dedicated to Crowley & Jane Austen fics...

Goodbye, Dear Jane by siephilde42 (T)

Aziraphale asks Crowley if he has ever gotten attached to another person, and Crowley admits that he grew quite fond of a certain author. Crowley feels guilty because he never properly said goodbye to her, so Aziraphale proposes a trip through time.

well-versed in etiquette, extraordinarily nice by laiqualaurelote (G)

Once she had said to him, hoping to probe: “It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.”

To which Mr Crowley had only responded: “What do you know of the universe, Miss Austen?”

In which Jane Austen, criminal mastermind and aspiring novelist, pulls off the 1810 Clerkenwell Diamond Robbery, with the help of a certain demon.

All those truths (some not so universally acknowledged) by strawberriesandtophats (E)

In which Aziraphale and Crowley meet up at a party during the Regency Period and have a great time eavesdropping on a certain famous author.

Literature and Liquor by Tossukka (T)

The year is 1809. Crowley’s friend Jane is a master smuggler of both goods and information who seems to know exactly who people are and how they act. She asks Crowley’s help with a larger robbery she has been planning, and Crowley agrees without hesitation. Meanwhile Aziraphale has been helping her friend, a brilliant author Miss Austen revise her novel manuscripts in the hopes that they could one day be published for the wider audiences. Aziraphale finds the books witty, innovative character studies of British gentry, but getting a romance novel written by a woman published in the early 1800s would take a real miracle.

When Aziraphale accompanies Jane to a ball, they run into Crowley, and all three are surprised by the other two being acquainted. Although the angel and the demon are happy to not poke further into each other’s businesses with Miss Austen, Jane seems to be convinced her two friends are in the middle of a great love story like from one of her novels and need some encouragement to admit their true feelings.

'Not Enough to Tempt Me' by ZephyrOfAllTrades (T)

Aziraphale found a new friend. A budding writer who unfortunately dabbles in matchmaking. It was all fun and games until she reunited with a familiar red-headed demon.

- Mod D

#good omens#ineffable husbands#ineffable wives#ineffable partners#jane austen#crowley & jane austen#aziraphale & jane austen#regency#mod d

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

A 19th Century Pearl Parure

A 19th century parure comprising a tiara, a necklace, a brooch and a pair of earrings in a fitted case

gold and silver set with pearls and rose-cut diamonds, height tiara ca 25 - 35 mm, total weight 56 g (the comb is missing), width necklace ca 5 - 13 mm, length with clasp ca 44.5 cm, dimensions brooch 25 X 60 mm, total weight 22 g, dimensions earrings 12 X 35 mm, total weight 7 g. The tiara and brooch with French hallmark Paris 1809 or later, the earring hook with a French hallmark in use between 1819 - 1838.

Provenance

Johanna Kempe (1818-1909) who got it from her mother Friederika Wallis. Thence by descent in the family.

Bukowskis

#parure#set#jewelry set#jewelry collection#tiara#tiaras#diadem#diadems#necklace#brooch#earring#earrings#diamond#diamonds#pearls#pearl#silver#Bukowski's#tiara crown#tiaras crowns#tiarascrowns#tiaracrown

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pietro Alessandro Guglielmi - Il trionfo di Giuditta, Imprint: Firenze: G. Fantosini, 1809

82 notes

·

View notes

Photo

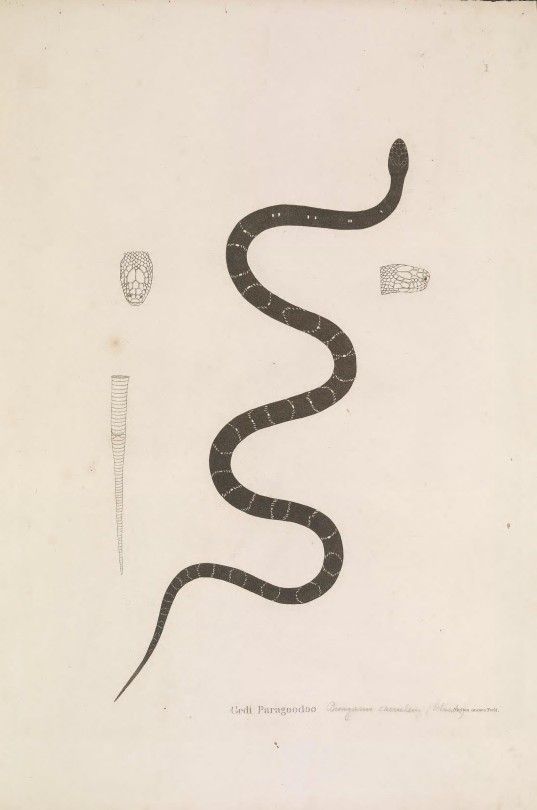

🐍 An account of Indian serpents, collected on the coast of Coromandel London: Printed by W. Bulmer and Co. Shakespeare-Press; for G. Nicol, 1796-1801 [i.e. 1796-1809?]

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) - Concerto No. 3 for "Lire organizzate" in G-Major, Hob. VIIh:3, I. Allegro con spirito. Performed by Manfred Hess/Haydn Sinfonietta Wien on period instruments.

#franz joseph haydn#joseph haydn#classicism#classical music#orchestra#period performance#period instruments#concerto#lire organizzate#woodwinds#strings#string orchestra#band#horns#brass#haydn

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

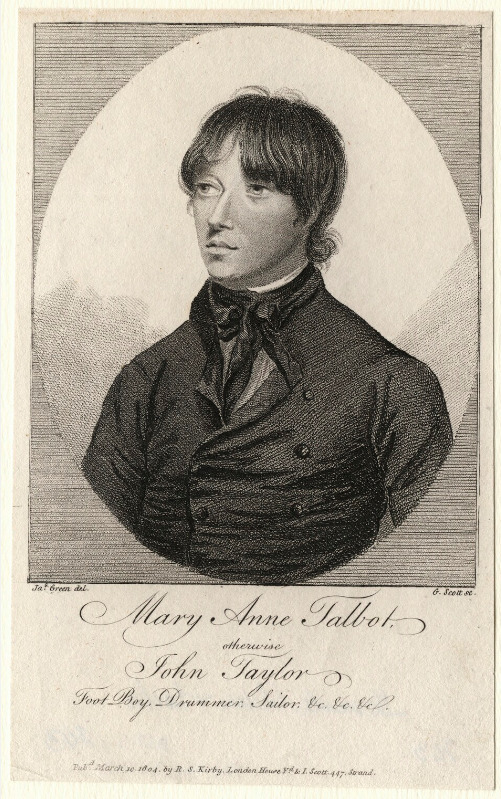

Mary Anne Talbot - a female Soldier and Sailor

Mary Anne Talbot is one of the women who have the adventure of serving at sea disguised as a male sailor. She was born in London on 2 February 1778, the illegitimate daughter of William Talbot, 1st Earl Talbot. Her mother died at birth, her presumed father when she was four years old. She was brought up by a wet nurse at Worthen in Shropshire until she was five, after which she attended a private boarding school in Chester, run by a Mrs Tapperly, until she was 14. The only relative she knew was an elder sister, an Hon. Miss Dyer, who also died quite young in the birth of her child in 1791. She enlightened Mary Anne about her presumed parentage before her death and left her a handsome fortune of £30,000 sterling. From this fortune Mary Anne could have had an annual income of 1500 pounds, but her sister's chosen guardian, a Mr. Sucker, did not provide for her further education, but gave her to Essex Bowen, a captain in the 82nd Regiment of Foot.

Mary Anne Talbot, by G. Scott, after James Green, published 1804 (x)

The latter took her to London, where he made her his not-so-voluntary mistress in 1792. But already in the autumn of 1792 he was to go to Flanders and simply took her with him. To this end, he passed her off as an errand boy, who took her to St. Domingo as John Taylor. From there she went to Flanders, where she was now listed as Drummer Boy. As such she took part in the capture of Valenciennes on 28 July 1793, where Captain Essex was killed. She now deserted the regiment and made her way through Luxembourg to the Rhine, until in September 1793, out of necessity, she signed on as a cabin boy to the captain of a French lugger called Le Sage. The lugger, according to her account, had been captured by Lord Howe in the Queen Charlotte, and "Taylor" (as she still called herself) was assigned to HMS Brunswick 74 guns under Captain John Harvey (1740-1794) as a powder monkey, in which capacity she took part in the great victory of 1 June 1794, but was severely wounded by a grape shot that shattered her left ankle.

Captain Essex with his footboy John Talbot (x)

She spent four months at Haslar Royal Naval Hospital in Gosport. She then became a midshipman on the Bomb Vessel Vesuvius. However, this was captured off Normandy by two French privateers. As a prisoner, Taylor remained in Dunkirk for 18th months. After her release, she signed on with the American ship Ariel under Captain John Field, sailing to New York in August 1796. In November she returned to London on the Ariel. There she was picked up by a press gang in Wapping. In order not to have to re-enter the Royal Navy, she revealed her true gender, whereupon she was discharged. She then haunted the Navy's pay office for some time, and various donations were collected for her. But she was intemperate and spent her money frivolously. The Duke and Duchess of York and the Duchess of Devonshire, it is said, interceded for her.

Mary Anne Talbot resisting a Press Gang, by John Chapman (x)

After a series of employments including a gig as a jeweller's assistant or a performance in a small theatre in Tottenham Court Road in the Babes in the Wood, and a stay in Newgate from which she was rescued by the Society for the Relief of Persons confined for small Debts, her misfortunes forced her to take refuge as a domestic servant in the house of the publisher Robert S. Kirby in St. Paul's Churchyard, who recorded her adventures in the second volume of his Wonderful Museum, 1804 and continued her story in The Life and Surprising Adventures of Mary Anne Talbot, 1809. After three years' service, a general deterioration, caused in part by the wounds and privations she had suffered, rendered her unable to work regularly, and she was removed to the house of an acquaintance in Shropshire at the end of 1807. There she remained for some weeks, and died on 4 February 1808, aged 30.

Mary Anne Talbot, by G. Scott, after James Green, published 1804 (x)

Perhaps some of you have noticed that there are certain similarities to Hannah Snell. And in fact, her story is very much in doubt. Because there are great inconsistencies with the times and the ships that she had given in her biography. Because there is no Talbot on the ships listed and there was no Talbot on the Vesuvius at the time it was captured, and the capture itself is also questionable because the ship was not off Normandy at that time but in the West Indies. Whether she just mixed things up here or whether they were chosen to spice up her story is questionable, and it cannot be ruled out that this story was a product of fantasy.

#naval history#mary anne talbot#female soldier and sailor#late 18th -early 19th century#women at sea#age of sail

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

irl bsd authors

i haven't found a list of irl bsd authors listed from oldest to most recent so i decided to do that. multiple lists for date of birth, death, and publication of the work their ability is based on (if applicable) + fun stuff at the end

birth dates (oldest to most recent)

alexander pushkin - 6 Jun 1799

nathaniel hawthorne - 4 Jul 1804

edgar allan poe - 19 Jan 1809

nikolai gogol - 1 Apr 1809

ivan gonchorav - 18 Jun 1812

herman melville - 1 Aug 1819

fyodor dostoevsky - 11 Nov 1821

jules verne - 8 Feb 1828

saigiku jōno - 24 Sep 1832

louisa may alcott - 29 Nov 1832

yukichi fukuzawa - 10 Jan 1835

mark twain - 30 Nov 1835

ōchi fukuchi - 13 May 1841

paul verlaine - 30 Mar 1844

bram stoker - 8 Nov 1847

tetchō suehiro - 15 Mar 1849

arthur rimbaud - 20 Oct 1854

ryūrō hirotsu - 15 Jul 1861

ōgai mori - 17 Feb 1862

h. g. wells - 21 Sep 1866

natsume sōseki - 9 Feb 1867

kōyō ozaki - 10 Jan 1868

andré gide - 22 Nov 1869

doppo kunikida - 30 Aug 1871

katai tayama - 22 Jan 1872

ichiyō higuchi - 2 May 1872

kyōka izumi - 4 Nov 1873

lucy maud montgomery - 30 Nov 1874

akiko yosano - 7 Dec 1878

santōka taneda - 3 Dec 1882

teruko ōkura - 12 Apr 1886

jun'ichirō tanizaki - 24 Jul 1886

yumeno kyūsaku - 4 Jan 1889

h. p. lovecraft - 20 Aug 1890

agatha christie - 15 Sep 1890

ryūnosuke akutagawa - 1 Mar 1892

ranpo edogawa - 21 Oct 1894

kenji miyazawa - 27 Aug 1896

f. scott fitzgerald - 24 Sep 1896

margaret mitchell - 8 Nov 1900

motojirō kajii - 17 Feb 1901

mushitarō oguri - 14 Mar 1901

john steinbeck - 27 Feb 1902

aya kōda - 1 Sep 1904

ango sakaguchi - 20 Oct 1906

chūya nakahara - 29 Apr 1907

atsushi nakajima - 5 May 1909

osamu dazai - 19 Jun 1909

sakunosuke oda - 26 Oct 1913

michizō tachihara - 30 Jul 1914

tatsuhiko shibusawa - 8 May 1928

(ace) alan bennett - 9 May 1934

yukito ayatsuji - 23 Dec 1960

mizuki tsujimura - 29 Feb 1980

death dates (oldest to most recent)

alexander pushkin - 10 Feb 1837

edgar allan poe - 7 Oct 1849

nikolai gogol - 4 Mar 1852

nathaniel hawthorne - 19 May 1864

fyodor dostoevsky - 9 Feb 1881

louisa may alcott - 6 Mar 1888

ivan goncharov - 27 Sep 1891

herman melville - 28 Sep 1891

arthur rimbaud - 10 Nov 1891

paul verlaine - 8 Jan 1896

tetchō suehiro -�� 5 Feb 1896

ichiyō higuchi - 23 Nov 1896

yukichi fukuzawa - 3 Feb 1901

saigiku jōno - 24 Jan 1904

jules verne - 24 Mar 1905

kōyō ozaki - 30 Oct 1903

ōchi fukuchi - 4 Jan 1906

doppo kunikida - 23 Jun 1908

mark twain - 21 Apr 1910

bram stoker - 20 Apr 1912

natsume sōseki - 9 Dec 1916

ōgai mori - 8 Jul 1922

ryūrō hirotsu - 25 Oct 1928

ryūnosuke akutagawa - 24 Jul 1927

katai tayama - 13 May 1930

motojirō kajii - 24 Mar 1932

kenji miyazawa - 21 Sep 1933

yumeno kyūsaku - 11 Mar 1936

h. p. lovecraft - 15 Mar 1937

chūya nakahara - 22 Oct 1937

michizō tachihara - 29 Mar 1939

kyōka izumi - 7 Sep 1939

santōka taneda - 11 Oct 1940

f. scott fitzgerald - 21 Dec 1940

lucy maud montgomery - 24 Apr 1942

mushitarō oguri - 10 Feb 1946

h. g. wells - 13 Aug 1946

akiko yosano - 29 May 1942

atsushi nakajima - 4 Dec 1942

sakunosuke oda - 10 Jan 1947

osamu dazai - 13 Jun 1948

margaret mitchell - 16 Aug 1949

andré gide - 19 Feb 1951

ango sakaguchi - 17 Feb 1955

teruko ōkura - 18 Jul 1960

ranpo edogawa - 28 Jul 1965

jun'ichirō tanizaki - 30 Jul 1965

john steinbeck - 20 Dec 1968

agatha christie - 12 Jan 1976

tatsuhiko shibusawa - 5 Aug 1987

aya kōda - 31 Oct 1990

(ace) allan bennett - still alive

yukito ayatsuji - still alive

mizuki tsujimura - still alive

work (oldest to most recent)

alexander pushkin - A Feast in Time of Plague, 1830

edgar allan poe - The Murders in Rue Morgue, 1841

nikolai gogol - The Overcoat, 1842

edgar allan poe - The Black Cat, 19 Aug 1843

nathaniel hawthorne - The Scarlet Letter, 1850

herman melville - Moby-Dick, 1851

louisa may alcott - Little Women, 1858

fyodor dostoevsky - Crime and Punishment, 1866

ivan goncharov - The Precipice, 1869

yukichi fukuzawa - An Encouragement of Learning, 1872-76

jules verne - The Mysterious Island, 1875

mark twain - The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, 1876

mark twain - Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, 1884

tetchō suehiro - Plum Blossoms in the Snow, 1886

arthur rimbaud - Illuminations, 1886

saigiku jōno - Priceless Tears, 1889

ōchi fukuchi - The Mirror Lion, A Spring Diversion, Mar 1893

ryūrō hirotsu - Falling Camellia, 1894

h. g. wells - The Time Machine, 1895

kōyō ozaki - The Golden Demon, 1897

bram stoker - Dracula, 1897 (his ability has not been named, but c’mon, vampires)

akiko yosano - Thou Shall Not Die, 1903

natsume sōseki - I Am a Cat, 1905-06

katai tayama - Futon, 1907

lucy maud montgomery - Anne of Green Gables, 1908

ōgai mori - Vita Sexualis, 1909

andré gide - Strait is the Gate, 1909

kyōka izumi - Demon Pond, 1913

ryūnosuke akutagawa - Rashomon, 1915

motojirō kajii - Lemon, 1924

f. scott fitzgerald - The Great Gatsby, 1925

kenji miyazawa - Be not Defeated by the Rain, 3 Nov 1931

santōka taneda - Self-Derision, 8 Jan 1932

mushitarō oguri - Perfect Crime, 1933

chūya nakahara - This Tainted Sorrow, 1934

yumeno kyūsaku - Dogra Magra, 1935

margaret mitchell - Gone With the Wind, 1936

john steinbeck - The Grapes of Wrath, 1939

agatha christie - And Then There Were None, 6 Nov 1939

atsushi nakajima - The Moon Over the Mountain, Feb 1942

jun'ichirō tanizaki - The Makioka Sisters, 1943-48

ango sakaguchi - Discourse on Decadence, 1946

teruko ōkura - Gasp of the Soul, 1947

osamu dazai - No Longer Human, 1948

(ace) alan bennett - The Madness of King George III, 1995

yukito ayatsuji - Another, 2005

mizuki tsujimura - Yesterday’s Shadow Tag, 2015

can’t find dates:

michizō tachihara - Midwinter Memento

sakunosuke oda - Flawless

n/a: doppo kunikida, ranpo edogawa, ichiyō higuchi, h. p. lovecraft “Great Old Ones” (fictional ancient dieties eg. cthulhu), aya koda, paul verlaine, tatsuhiko shibusawa “Draconia” (umbrella term for shibusawa’s works/style)

bonus:

elise - The Dancing Girl (1890) by ōgai mori

shōsaku katsura - An Uncommon Common Man by doppo kunikida

Nobuko Sasaki (20 Jul 1878 - 22 Sep 1949) - doppo kunikida’s first wife

gin akutagawa - O-gin (1922) by ryūnosuke akutagawa

naomi tanizaki + kirako haruno - Naomi (1925) by jun'ichirō tanizaki

t. j. eckelburg + tom buchanan - The Great Gatsby (1925) by f. scott fitzgerald

the black lizard - Back Lizard (1895) by ryūrō hirotsu (+ The Black Lizard (1934) by ranpo edogawa)

some fun facts:

the oldest: aya koda 86, andré gide 81, h. g. wells 79, jun'ichirō tanizaki 79, ivan goncharov 79 (alan bennett is 89 but still alive)

the youngest: ichiyō higuchi 24, michizō tachihara 24, chūya nakahara 30

yukito ayatsuji’s Another is also an anime, released in 2012

both edgar allan poe and mark twain’s ability consist of two of the author’s work

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pietro Alessandro Guglielmi - Il trionfo di Giuditta, Imprint: Firenze: G. Fantosini, 1809.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Marshalate (Part 2)

Continuing with David G. Chandler’s writings about the marshalate, from my copy of his The Illustrated Napoleon:

But the price he demanded in return for these honors was high. The marshals were required to go on active service in command of the corps d’armee or in senior staff appointments year after year. They were not protected against shot and shell: fully half were wounded one or more times as marshals (Oudinot on no less [sic] than eight occasions), and three - Lannes, Bessieres and Poniatowski - were killed in action or died of wounds sustained in battle. High rank was not a guarantee of personal survival in the early nineteenth century, as military leadership was carried on very much from the forward edge of the battle area (Napoleon himself, of course, being twice wounded - at Toulon [1793] and Ratisbon [1809] - and narrowly avoiding death at Arcola [1796], in front of Acre [1799] and at Arcis-sur-Aube [1814], besides surviving several assassination attempts). Four more met violent deaths outside the field of battle: Murat and Ney in front of firing squads, and Brune at the hands of a royalist mob (all in 1815), while in 1835, Mortier, at the age of sixty-seven, became the victim of an “infernal machine” intended for Louis-Philippe. Berthier’s demise in 1815 remains a mystery; he may have been a fifth.

Apologies for being so detail-obsessed, but it should be “Oudinot on no fewer than eight occasions”. As in “I use less [uncountable quantity] salt in my cooking than before, so I have modified no fewer [it’s possible to count how many] than thirty of my favourite recipes.” It’s possible to count Oudinot’s injuries as a marshal, eight times, so it’s no fewer, not no less. Although some might argue with little exaggeration that Oudinot’s wounds were without number.

There. I got that off my chest, this grammatical mistake that rattles my teeth every time. Now onto something else that bothers me in this paragraph: Chandler alludes to the possibility that Berthier was murdered. While Berthier’s death was certainly violent, I think the likelihood that a team of assassins was sent to throw him from a high window is vanishingly small. I wrote about this at some length in a September 2021 post entitled How Berthier died: An opinion piece.

Back to Chandler:

Even when not on campaign, Napoleon kept his marshals busy with diplomatic, administrative and court duties, which left them little time to enjoy their privileges. He also fanned their rivalries and dislikes - even hatreds - believing in the benefits of “divide and rule”. He intended them to be instruments of his imperial will both on campaign and in battle, and did little to encourage the development of individual talents or independent command skills by way of formal training. Three - Massena, Davout and Suchet - were truly notable commanders in their own right, and would have made names for themselves regardless of any connection with Napoleon; but many of the remainder were far from outstanding commanders at the strategic or operational level, though all were good tacticians and brave individuals able to inspire their troops.

All was well, therefore, while they remained beneath their master’s eye. But when the exigencies of service separated them from the emperor (as in 1812, when Napoleon was fighting in Russia and other French troops were fighting in Spain), problems would often arise. Untrained in independent campaigning, incapable of fighting in a properly integrated command team (as no marshal would acknowledge any other as his superior), the marshals in Spain and elsewhere often allowed their personal feuds to overcome their sense of duty when Napoleon was not present to keep them in line and up to the mark; the results were defeats, disappointments and failures. War-weariness became increasingly noticeable after the disasters of 1812 and had not been unknown among the marshals in earlier years. Only those who were incapacitatingly wounded or had the fortune to incur Napoleon’s wrath and were in consequence left unemployed were able to secure any real rest or time to live with their families and enjoy their privileges. In the end, the system let the emperor down badly. At Fontainebleau in April 1814, a group of marshals, led by Ney, mutinied and enforced Napoleon’s first abdication. During the Bourbon restoration, most of the marshals made their peace with the new regime and several served Louis XVIII in high positions. In 1815, when Napoleon returned from exile on Elba for the “Hundred Days”, only a handful of his former marshals rallied to the tricolor; others continued to be loyal to the Bourbons or made themselves conspicuous by their absence from Paris, ignoring summonses from Davout (Napoleon’s minister of war) or finding excuses for not complying with his orders on behalf of the emperor.

David G. Chandler, The Illustrated Napoleon. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1973, 1990. pp. 90-92.

Of the marshals who were incapacitatingly wounded, I know for a certainty about Augereau, wounded at Eylau, and Marmont who almost lost an arm in Spain. Soult was severely wounded early in his career, though I don’t remember, assuming I ever knew, how long he was allowed for his recovery ( @josefavomjaaga ?)

When Chandler refers to war-weariness even before 1812, I believe he has Lannes in mind (confirmation from @maggiec70 about this?). I don’t know enough about this to figure out if Chandler also was thinking of other marshals, though I would not be surprised if Augereau had had his fill also well before 1812. As to war-weariness after 1812, nothing would be less surprising; I can’t even start to imagine the effect of the calamitous Russian campaign on the minds of the marshals, and indeed of every member of the military who had the misfortune to witness it.

About the handful of marshals who rallied to Napoleon in 1815, here is what I know: as Chandler wrote, Lannes, Bessieres and Poniatowski were dead; Bernadotte was in Sweden and part of the coalition against Napoleon; Berthier was a virtual prisoner in Bavaria, and would soon be dead; Serurier, Perignon and Kellermann had been out of active service for a dozen years at least, and my guess is that Napoleon would not have given them active commands anyway; Gouvion Saint-Cyr, I believe, and certainly Oudinot, chose to remain neutral; Macdonald, Marmont, and Victor remained at the service of Louis XVIII; Murat was otherwise occupied, though I don’t know precisely the chronology of his activities in 1815 ( @joachimnapoleon : help? pretty please?).

Of those who did join Napoleon in his final adventure, but not necessarily from its very start, there were: Brune, whose decision cost him his life at the hands of a mob; Davout, disastrously left in Paris; Grouchy; Mortier, incapacitated at the time of Waterloo; Massena, with the utmost reluctance; Ney, whose decision also cost him his life; Soult; and Suchet.

I am unsure about the stance taken by Jourdan, Lefebvre and Moncey at the time.

Coming soon, the final part of this topic.

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

puma ads was an art tbh (i found some treasure in my drafts)

or 574 days before yoongi come back

#dailybts#userbangtan#yoonkooknetwork#bts#bangtan#bangtan boys#suga#min yoongi#yoongi#big shushu#era: idol#era: love yourself#puma#puma basket#made by bts#basket#v: commercial#commercial#g: 1809#daeguboynet#bt21net#bangtanarmynet#btsedit#bangtangif

123 notes

·

View notes

Quote

“Puedes imponerme silencio, pero no puedes evitar que piense”

Aurore Dupin

Amantine Aurore Lucile Dupin de Dudevant, mas conocida con el seudónimo de George Sand, fue una periodista y novelista francesa nacida en París en julio de 1804, considerada como una de las escritoras mas populares de Europa en el siglo XIX.

Sand es reconocía como una de las escritoras mas notables del Romanticismo Frances.

Primeros años

Su madre era Sophie-Victoire Delaborde, era proveniente de una familia pobre e inestable, y su padre de nombre Maurice Dupin fue nieto del mariscal general de Francia Mauricio de Sajonia conde de Saxe, y emparentado con el Rey Luis Felipe I de Francia a través de antepasados comunes de familias reinantes alemanas y danesas.

El matrimonio de Maurice Dupin y Sophie-Victoire estuvo mal visto por la sociedad de la época y no fue aceptado por la madre de Maurice y abuela de George Sand.

La familia de Sand se vió forzada a vivir en España por motivos laborales y esa estancia fue descrita por George como una de las mas felices de su vida. Es en este momento cuando George Sand comenzó a manifestar tendencias masculinas para la época.

En 1809 la familia regresa a Francia en donde vivieron en la finca de la abuela de Sand. La finca de Nohant fue el escenario de muchas de sus novelas y poco tiempo después de instalarse, su padre sufre un accidente con un caballo y muere y es en ese momento que la rivalidad entre la aristocrática abuela de Sand y su madre se acentúa.

Al volverse difícil la relación de la abuela con la madre esta ultima deja la finca y abandona París, dejando a Sand al cuidado de la abuela. En 1822 la abuela muere y Sand hereda toda su fortuna.

A los 18 años se casó con un Baron quien abandona en menos de 10 años para irse a París en donde comienza a colaborar en el diario Le Figaro, en donde se enamora del periodista Jules Sandeau, de donde se bosqueja el primer seudónimo de Aurora como Sand.

Al firmar su siguiente relato, se ve forzada a inventar otro seudónimo, cambiando la inicial “J” de Jules por la G de George y el apellido Sandeau por Sand.

Legado

Fue una escritora incansable y una fervorosa luchadora por los intereses del pueblo, por la libertad individual y por la igualdad entre sexos.

Compaginó sus centenares de libros, colaboraciones en prensa y misivas con inumerables viajes, multiples amantes y buenas amistades con intelectuales y artistas de la época como Franz Liszt, Eugene Delacroix, Heinrich Heine, Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert y Julio Verne.

George Sand fumaba, vestía pantalones y escribir novelas, dichas actitudes eran escandalosas en su tiempo. Desafiaba los prejuicios tanto en la literatura como en lo personal.

Asumió la idea del amor libre en Francia y tuvo diversos romances, algunos de ellos muy turbulentos entre los que destacan los que tuvo con el compositor Frédéric Chopin, la actriz Marie Dorval o el poeta Alfred Musset.

Últimos años

Durante los últimos años de su vida se refugió en si misma. Vivió en Nohant donde residió de forma permanente hasta el final de sus días, protegiendo a escritores jóvenes como Gustave Flaubert y escribiendo relatos idílicos hasta los últimos días de su vida.

Muere en Nohant Francia en junio de 1876.

Fuentes: Wikipedia, biografiasyvidas.com, lavanguardia.com

#frases#frases de escritores#citas de escritores#george sand#francia#frases de reflexion#citas de reflexion#notas del alma

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

October 23, 1809

Copenhagen, October 23, 1809. No theatre was opened last evening, nor was there any public amusement. After strolling an hour, during which mus. mauv.; 1 d.¹ came home; took tea as my supper; engaged a servant at 3 marks a day; not, however, to attend me exclusively. LI. de ch. gro. pas mauv. mus. encore.² My room, a very large and elegant one on the first floor, looks into the square, and it is again my good fortune to have a military parade and band of music under my window in the morning. After breakfast sent cards to Olsen, formerly minister plenipotentiary from this government to the United States, and to Nailsen, formerly judge in Santa Cruz, who passed some time in New York on his way home. Both were abroad. Olsen at some distance at a country seat. Sent also Baron d'Albedÿhll's letter to M. de Coningk, conseiller d'etat³ with card. Hearing that G. Jay, American consul for Rotterdam, lodged in this house, sent my name by a servant. Walked about town an hour or two. It is regularly laid out on a plain. The harbour artificial. Very few vessels. Houses almost universally of brick, but generally made white or stone-coloured. Had a bowl of soup, with a bottle of Rhenish wine, in my room for dinner. In the afternoon took a servant to pilot me to the Observatory. The height is said to be 160 feet, placed nearly in the center of the town, and affords a most perfect bird's-eye view of the whole, with a prospect of the ocean; a fine landscape in the interior; the Palace of Fredericksberg, finely placed on an eminence. The Swedish coast. The ascent to the top is singular; not by steps, but an inclined spiral plane, paved with brick. It is said that a former King drove up with a coach and four, which is very practicable till you come within about ten feet of the summit, where you have steps, but how he got back is not said, for it is utterly impossible to turn. Paid 1 mark, and one more to my conductor. Home and alone the evening. La flick⁴ later.

1 For muse mauvaise; 1 dollar. Bad muse; 1 dollar.

2 For Fille de chambre; grosse, pas mauvaise. Muse encore. The chambermaid, fat, not bad; muse again.

3 State Councilor.

4 For la flicka. French and Swedish. The lass.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Best Classical Music

The Best Symphony

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) - Symphony No. 6 in F Major, Op. 68 (“Pastoral”) (1808) Best Sixth Symphony

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) - Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 (“Choral”) (1824)

Antonin Leopold Dvorak (1841-1904) - Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95, B. 178 (“From the New World”) (1893) Best Ninth Symphony

Charles-Camille Saint-Saens (1835-1921) - Symphony No. 3 in C minor, Op. 78 (“Organ”) (1886)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) - Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 (1812)

Sergei Vasilievich Rachmaninov (1873-1943) - Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27 (1907) Best Second Symphony

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) - Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (“Fate”) (1808)

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) - Symphony No. 5 in C sharp minor (1902)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) - Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 (“Pathetique”) (1893)

Henryk Mikolaj Gorecki (1933-2010) - Symphony No. 3, Op. 36 (“Symphony of Sorrowful Songs”) (1976)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) - Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64 (1888) Best Fifth Symphony

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) - Symphony No. 3 in E flat Major, Op. 55 (“Eroica”) (1804)

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) - Symphony No. 2 in C minor (“Resurrection”) (1894)

Jean Johan Julius Christian Sibelius (1865-1957) - Symphony No. 5 in E flat Major, Op. 82 (1919)

Jean Johan Julius Christian Sibelius (1865-1957) - Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 43 (1902)

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) - Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14 (1830)

Franz Peter Schubert (1797-1828) - Symphony No. 9 in C Major, D. 944 (“Great”) (1826)

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) - Symphony No. 1 in D Major (“Titan”) (1894)

Dmitry Dmitriyevich Shostakovich (1906-1975) - Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47 (1937)

Antonin Leopold Dvorak (1841-1904) - Symphony No. 8 in G Major, Op. 88, B. 163 (1890)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) - Symphony No. 4 in B flat Major, Op. 60 (1806) Best Fourth Symphony

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) - Symphony No. 41 in C Major, K. 551 (“Jupiter”) (1788)

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) - Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 (1876)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) - Symphony No. 40 in G minor, KV. 550 (“The Great G minor”) (1788)

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847) - Symphony No. 4 in A Major, Op. 90 (“Italian”) (1833)

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) - Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98 (1885)

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847) - Symphony No. 3 in A minor, Op. 56 (“Scottish”) (1842)

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) - Symphony No. 1 in D Major, Op. 25 (“Classical”) (1917)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) - Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36 (1878)

Jean Johan Julius Christian Sibelius (1865-1957) - Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39 (1899) Best First Symphony

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) - Symphony No. 3 in F Major, Op. 90 (1883) Best Third Symphony

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) - Symphony No. 8 in E flat Major (“Symphony of a Thousand”) (1907) Best Eighth Symphony

Josef Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) - Symphony No. 7 in E Major, WAB 107 (1885) Best Seventh Symphony

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) - Symphony No. 5 in D Major (1943)

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)- Symphony No. 94 in G Major, Hob. 1/94 (“Surprise”) (1791)

The Best Piano Concerto

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) - Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466 (1785)

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) - Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat Major, Op. 83 (1881)

Sergei Vasilievich Rachmaninov (1873-1943) - Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18 (1901)

Edvard Hagerup Grieg (1843-1907) - Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 (1868)

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) - Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54 (1845)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) - Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat Major “Emperor’, Op. 73 (1811)

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) - Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Major, Op. 26 (1921)

Joseph-Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) - Piano Concerto in G Major (1931)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) - Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58 (1806)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) - Piano Concerto No. 23 in A Major, K. 488 (1786)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) - Harpsichord Concerto No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1054 (1721)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) - Piano Concerto No. 21 in C Major, K. 467 (1785)

Sergei Vasilievich Rachmaninov (1873-1943) - Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 (1909)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) - Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat minor, Op. 23 (1875)

Joseph-Maurice Ravel (1975-1937) - Piano Concerto for the Left Hand in D Major (1930)

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) - Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor, Op. 15 (1858)

Frederic Francois Chopin (1810-1849) - Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 (1830)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) - Harpsichord Concerto No. 1 in D minor, BWV 1052 (1721)

Camille Saint-Saens (1835-1921) - Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op.22 (1868)

Bela Viktor Janos Bartok (1881-1945) - Piano Concerto No. 3 in E Major, Sz. 119, BB 127 (1945)

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847) - Piano Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25 (1831)

Frederic Francois Chopin (1810-1849) - Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 (1830)

Franz Liszt (1811-1886) - Piano Concerto No. 1 in E flat Major, S.124 (1849)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pietro Alessandro Guglielmi - Il trionfo di Giuditta, Imprint: Firenze: G. Fantosini, 1809.

42 notes

·

View notes