#indigenous languages are always so complex its very interesting

Text

10 Lessons on Realistic Worldbuilding and Mapmaking I Learned Working With a Professional Cartographer and Geodesist

Hi, fellow writers and worldbuilders,

It’s been over a year since my post on realistic swordfighting, and I figured it’s time for another one. I’m guessing the topic is a little less “sexy”, but I’d find this useful as a writer, so here goes: 10 things I learned about realistic worldbuilding and mapmaking while writing my novel.

I’ve always been a sucker for pretty maps, so when I started on my novel, I hired an artist quite early to create a map for me. It was beautiful, but a few things always bothered me, even though I couldn’t put a finger on it. A year later, I met an old friend of mine, who currently does his Ph.D. in cartography and geodesy, the science of measuring the earth. When the conversation shifted to the novel, I showed him the map and asked for his opinion, and he (respectfully) pointed out that it has an awful lot of issues from a realism perspective.

First off, I’m aware that fiction is fiction, and it’s not always about realism; there are plenty of beautiful maps out there (and my old one was one of them) that are a bit fantastical and unrealistic, and that’s all right. Still, considering the lengths I went to ensure realism for other aspects of my worldbuilding, it felt weird to me to simply ignore these discrepancies. With a heavy heart, I scrapped the old map and started over, this time working in tandem with a professional artist, my cartographer friend, and a linguist. Six months later, I’m not only very happy with the new map, but I also learned a lot of things about geography and coherent worldbuilding, which made my universe a lot more realistic.

1) Realism Has an Effect: While there’s absolutely nothing wrong with creating an unrealistic world, realism does affect the plausibility of a world. Even if the vast majority of us probably know little about geography, our brains subconsciously notice discrepancies; we simply get this sense that something isn’t quite right, even if we don’t notice or can’t put our finger on it. In other words, if, for some miraculous reason, an evergreen forest borders on a desert in your novel, it will probably help immersion if you at least explain why this is, no matter how simple.

2) Climate Zones: According to my friend, a cardinal sin in fantasy maps are nonsensical climate zones. A single continent contains hot deserts, forests, and glaciers, and you can get through it all in a single day. This is particularly noticeable in video games, where this is often done to offer visual variety (Enderal, the game I wrote, is very guilty of this). If you aim for realism, run your worldbuilding by someone with a basic grasp of geography and geology, or at least try to match it to real-life examples.

3) Avoid Island Continent Worlds: Another issue that is quite common in fictional worlds is what I would call the “island continents”: a world that is made up of island-like continents surrounded by vast bodies of water. As lovely and romantic as the idea of those distant and secluded worlds may be, it’s deeply unrealistic. Unless your world was shaped by geological forces that differ substantially from Earth’s, it was probably at one point a single landmass that split up into fragmented landmasses separated by waters. Take a look at a proper map of our world: the vast majority of continents could theoretically be reached by foot and relatively manageable sea passages. If it weren’t so, countries such as Australia could have never been colonized – you can’t cross an entire ocean on a raft.

4) Logical City Placement: My novel is set in a Polynesian-inspired tropical archipelago; in the early drafts of the book and on my first map, Uunili, the nation’s capital, stretched along the entire western coast of the main island. This is absurd. Not only because this city would have been laughably big, but also because building a settlement along an unprotected coastline is the dumbest thing you could do considering it directly exposes it to storms, floods, and, in my case, monsoons. Unless there’s a logical reason to do otherwise, always place your coastal settlements in bays or fjords.

Naturally, this extends to city placement in general. If you want realism and coherence, don’t place a city in the middle of a godforsaken wasteland or a swamp just because it’s cool. There needs to be a reason. For example, the wasteland city could have started out as a mining town around a vast mineral deposit, and the swamp town might have a trading post along a vital trade route connecting two nations.

5) Realistic Settlement Sizes: As I’ve mentioned before, my capital Uunili originally extended across the entire western coast. Considering Uunili is roughly two thirds the size of Hawaii the old visuals would have made it twice the size of Mexico City. An easy way to avoid this is to draw the map using a scale and stick to it religiously. For my map, we decided to represent cities and townships with symbols alone.

6) Realistic Megacities: Uunili has a population of about 450,000 people. For a city in a Middle Ages-inspired era, this is humongous. While this isn’t an issue, per se (at its height, ancient Alexandria had a population of about 300,000), a city of that size creates its own set of challenges: you’ll need a complex sewage system (to minimize disease spreading like wildfire) and strong agriculture in the surrounding areas to keep the population fed. Also, only a small part of such a megacity would be enclosed within fantasy’s ever-so-present colossal city walls; the majority of citizens would probably concentrate in an enormous urban sprawl in the surrounding areas. To give you a pointer, with a population of about 50,000, Cologne was Germany’s biggest metropolis for most of the Middle Ages. I’ll say it again: it’s fine to disregard realism for coolness in this case, but at least taking these things into consideration will not only give your world more texture but might even provide you with some interesting plot points.

7) World Origin: This point can be summed up in a single question: why is your world the way it is? If your novel is set in an archipelago like mine is, are the islands of volcanic origin? Did they use to be a single landmass that got flooded with the years? Do the inhabitants of your country know about this? Were there any natural disasters to speak of? Yes, not all of this may be relevant to the story, and the story should take priority over lore, but just like with my previous point, it will make your world more immersive.

8) Maps: Think Purpose! Every map in history had a purpose. Before you start on your map, think about what yours might have been. Was it a map people actually used for navigation? If so, clarity should be paramount. This means little to no distracting ornamentation, a legible font, and a strict focus on relevant information. For example, a map used chiefly for military purposes would naturally highlight different information than a trade map. For my novel, we ultimately decided on a “show-off map” drawn for the Blue Island Coalition, a powerful political entity in the archipelago (depending on your world’s technology level, maps were actually scarce and valuable). Also, think about which technique your in-universe cartographer used to draw your in-universe map. Has copperplate engraving already been invented in your fictional universe? If not, your map shouldn’t use that aesthetic.

9) Maps: Less Is More. If a spot or an area on a map contains no relevant information, it can (and should) stay blank so that the reader’s attention naturally shifts to the critical information. Think of it this way: if your nav system tells you to follow a highway for 500 miles, that’s the information you’ll get, and not “in 100 meters, you’ll drive past a little petrol station on the left, and, oh, did I tell you about that accident that took place here ten years ago?” Traditional maps follow the same principle: if there’s a road leading a two day’s march through a desolate desert, a black line over a blank white ground is entirely sufficient to convey that information.

10) Settlement and Landmark Names: This point will be a bit of a tangent, but it’s still relevant. I worked with a linguist to create a fully functional language for my novel, and one of the things he criticized about my early drafts were the names of my cities. It’s embarrassing when I think about it now, but I really didn’t pay that much attention to how I named my cities; I wanted it to sound good, and that was it. Again: if realism is your goal, that’s a big mistake. Like Point 5, we went back to the drawing board and dove into the archipelago’s history and established naming conventions. In my novel, for example, the islands were inhabited by indigenes called the Makehu before the colonization four hundred years before the events of the story; as it’s usually the case, all settlements and islands had purely descriptive names back then. For example, the main island was called Uni e Li, which translates as “Mighty Hill,” a reference to the vast mountain ranges in the south and north; townships followed the same example (e.g., Tamakaha meaning “Coarse Sands”). When the colonizers arrived, they adopted the Makehu names and adapted them into their own language, changing the accented, long vowels to double vowels: Uni e Li became “Uunili,” Lehō e Āhe became “Lehowai.” Makehu townships kept their names; colonial cities got “English” monikers named after their geographical location, economic significance, or some other original story. Examples of this are Southport, a—you guessed it—port on the southernmost tip of Uunili, or Cale’s Hope, a settlement named after a businessman’s mining venture. It’s all details, and chances are that most readers won’t even pay attention, but I personally found that this added a lot of plausibility and immersion.

I could cover a lot more, but this post is already way too long, so I’ll leave it at that—if there’s enough interest, I’d be happy to make a part two. If not, well, maybe at least a couple of you got something useful out of this. If you’re looking for inspiration/references to show to your illustrator/cartographer, the David Rumsey archive is a treasure trove. Finally, for anyone who doesn’t know and might be interested, my novel is called Dreams of the Dying, and is a blends fantasy, mystery, and psychological horror set in the universe of Enderal, an indie RPG for which I wrote the story. It’s set in a Polynesian-inspired medieval world and has been described as Inception in a fantasy setting by reviewers.

Credit for the map belongs to Dominik Derow, who did the ornamentation, and my friend Fabian Müller, who created the map in QGIS and answered all my questions with divine patience. The linguist’s name is David Müller (no, they’re not related, and, yes, we Germans all have the same last names.)

#enderal#dreams of the dying#worldbuilding#resource#writeblr#writing tips#mapmaking#cartography#illustration#realism#writeblogging#novelwriting#writing research#research#writing

784 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you do one for america

Since I received this about an hour or two after posting my lithuania analysis, I assume you’re asking for an america character analysis. I was debating whether or not to go through with writing this or not for a while, but i’ve decided that I’ll try. I hope you enjoy it!

Idealism

The first thing that sticks out to me when thinking about america is that he’s super idealistic, and I think this has its roots in his birth. Everything in his life has been about hope and being better than others, even down to the decision to colonise north america. England needs to be the most powerful country in europe. Better set up a colony in america so that it can save us. It’s that sort of logic that i think gives america the idea that he needs to be perfect, or that he can be the ideal person. And though a lot of what we consider to be the “american” identity (intense patriotism, nativism, idealism, etc) took recognizable shape in the 19th century, i think this way of thinking was nothing new to alfred. He’d been raised on it, with the desire to please arthur sort of in his blood? Anyway i feel like the idea that the colonies would be so so prosperous really put the idea into america’s head early on that he was perfect and that he was destined to be such a great person, even if that wasn't true. I often see his daddy issues presented as solely abandonment issues, but my interpretation of america is more of a combination of abandonment issues and the pressure, some of it self inflicted, to be a perfect country. Basically, his idealism is deeply rooted in unhealthy places.

Also, a religion headcanon i have is that while he was more raised to be a puritan, freddie prefers quakerism. Though he’s not the most compatible with quakerism, as it rejects violence and quakers often refer to themselves as the society of friends, and are very welcoming, i think it gives him some hope. One of freddie’s biggest problems is that he wants people to be better than they are, and quakerism helps a little with that, because it’s a way that he can help himself become better than he currently is. I feel like he’s been a quaker for a very long time, so he’s not a very good quaker, but this is still something that’s very important to him.

Hero complex and other mental bullshit

America having a hero complex and also being physically 19 is something i think really highly of. First of all, it very much fits with the mythology of america being a sort of world savior. Secondly, a lot of american media focuses on heroism, whether its on the behalf of average people, like the hunger games, or on the behalf of superheroes, like the mcu- especially over the past 20 years. Though i think it’s a good thing to promote heroism, the hero-martyr complex that gen z has is. Oof. And i think alfred fits very well into that toxic sort of “heroism” that most gen z kids have. He thinks he’s somehow able to fix everything wrong with the world, just because he really wants to. Though that desire is genuine, it’s not always something that’s his place to fix or something that even needed fixing. There’s also a selfish component to that- He needs to prove himself, and heroism is the only way he thinks he can do that. It’s why he works out constantly and cares so much, on a personal rather than country-avatar-thing level, about being #1 at everything. He has to be better than everyone else because he has to be the perfect hero.

I also think it’s interesting how america seems to have more pronounced daddy issues than canada, and i think this is something that harkens back to the 13 colonies (side note i hate the term ‘colonial times’ when referring to the time before the revolutionary war or canadian independence. These are settler states, its always colonial times.) and american independence. Canada sort of only exists because of british loyalists, as they made up the majority of the population around the turn of the 19th century. They saw themselves as being The Better Colonists. Real daddy’s boy types, and I think this is something that contributes to the hero complex. Because matthew refused to rebel so openly, that made arthur favor him as a son, so alfred felt the need to be even better than matthew- even though, of course, alfred was a bit more favored.

Fighting Style

Freddie is very good at violence, but not in the same way that a lot of other nations are. Where they tend to be more well trained in specific styles of fighting, freddie just sort of has all of them? His mind is very crowded, i think. Also, the way that he would have learned to fight is different from the other super powerful countries by virtue of his youth, and by virtue of the different regional fighting styles in america. One that’s haunted me is a trend in the ability to rip off ears and noses- Particularly by white gangs in the antebellum south, this was seen as being like. A real badass. I think alfred was something of a feral child. If you know the saying “it takes a village to raise a child,” i think it really did with him. He had so many parents, just like a lot of the western hemisphere countries. But anyway because of all his many many parents, there was never any strong parental force in his life, so it’s more like he didn’t have any at all, and because of that, alfred was a very strange child. And because violence is so ingrained in american society, alfred is very good at fighting, both in order to be fun and flashy and for his own self defense. Though he doesn't really like to fight unless he feels like he has to (and other people are very good at convincing him that he does have to)

Sports

Though america is definitely super athletic and could probably naturally be good at most sports, i think there’s a few that he’d more gravitate towards. Those are basketball, track and field, and olympic lifting. I would include american football but it’s a stupid sport that doesn’t make any sense, so it will not be included for spite reasons. In basketball I think he’s sort of an every-man. I think he’s around six feet tall, so he really could play any position on offense, and as for defense, I think he’d play his best defense against the point guard, bc i feel like Alfred is really fast and good at getting up in your face. He’d have a ton of steals whenever defending against the point guard. I think he’d be a good center on offense, because he’s a bit aggressive and that would be useful for getting rebounds and put-backs, though i wouldn’t discount point-guard freddie, because he does like to be very inspiring. He’s pretty energetic as well, and a point guard can really carry the entire team in terms of energy and spirit. As for track and field, he’d also be an every man- I feel like he’d gravitate more towards sprinting events by personality, but his coach would stick him in wherever. Where olympic lifts are concerned, he’s absolutely a snatch specialist.

Empire and contradictions

America is an empire. No way of getting around that. I think imperialism in hetalia is an interesting subject, especially where america is concerned. @mysticalmusicwhispers did a good job running that down here, but basically my thoughts on the matter are that alfred doesn't really like being an empire. There’s many angles to that. It’s lonely at the top, for one. There’s no one who relates to being a 21st century empire in quite the same way as him. Then you have the fact that a lot of people living in america have suffered under imperialism as well. Because of that, there’s a lot of self hatred and anxiety and a not knowing if he can fully trust himself. Theres also the obsession that many americans have with people from other cultures being able to assimilate to american wasp culture. Because of all the people who live in the states who are very much not wasps and who can never be, it’s really hard on alfred, though he refuses to admit that things are anything but fine.

Extras/Fun stuff

A book that reminds me of him is The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien. It’s a collection of short stories about O’Brien’s time serving in the military during the Vietnam War. It’s a very haunting book and I think about it at least once a week, but it is very violent and there’s a lot of fucked up stuff in it.

giveme chubby alfred or give me death

i feel like this shouldn’t have to be said, but sometimes there’s people who depict him as being pro-trump or pro-right wing bullshit, which. absolutely not. just because of all the political turmoil that exists within alfred, and because of all the pain he goes through because of all the hate that exists within his borders- hate that the entire world is forced to pay attention to. even though he might not have all the best sympathies or motivations, he’s just so tired of all the pain he personally goes through because of domestic political unrest, and would like it to end in the way that’s the least painful for him as a person.

Bi king of my heart

not a natural blond

I hc him as being mixed, though i’m not sure what exactly he’d look like? But i do enjoy alfred but not white, as poc are the driving force behind a lot of american life, right down to the languages we speak. Like. something like half the states names are the words of their indigenous peoples, and even more toponyms are indigenous across the country. Then of course i feel he’s very protective of aave and will always pronounce words in Not English correctly. (if u want to hear more about my language thoughts they’re linked below. Not gonna rehash it here cause those posts are Long™)

My playlist for him!

Other analyses (age, linguistics)

writing requests

#@ mystic how does it feel to be tagged in two of my writing request posts#im sorry i love your writing sm#anyway thanks for the ask anon! im not quite so angsty about america right now so this probably#is not as good as it could've been were i in my feelings about him#anywhomst! hope u enjoy this#hetalia#hws#hws america#tw violence#tw imperialism#?#sort of#i dont go into detail about the imperialism but its metnioned#ask#anon#writing requests#character analysis#ceros posting

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pekolah Stories. By Amanda Bales. Cowboy Jamboree Press, 2021.

Rating: 4.5/5 stars

Genre: short stories, literary fiction, contemporary

Part of a Series? No

Summary: “Amanda Bales’s Pekolah Stories reveal the desperation of rural communities eviscerated by economic collapse, steeped in an unforgiving, poisonous religion, and accustomed to everyday meanness and ravaged families. Children growing up in cultural swamps, in these stories and in real life, never recover. Many die of suicide or violence or drugs. Some go to prison, few go to college, and even the ones who appear to survive carry hidden wounds that threaten to drag them back down. Bales’s stories fearlessly trace the grasping tentacles of generational trauma, leaving readers to reckon with truths that land like a punch to the solar plexus.” —Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

***Full review under the cut.***

Content Warnings: violence, blood, homophobia, references to abuse and drug/alcohol use, self-harm and suicide

Overview: In the interest of full transparency, Bales is a friend and (former?) colleague of mine, so while I will try to be as honest as I can in this review, know that my opinions are not unbiased.

I’m not usually one to read short stories, much less short stories set in contemporary America, but because my friend wrote this, I bought a copy and read it cover to cover. I was pleasantly surprised by how much it resonated with me - I think Bales has a real talent for eliciting complex emotions, and I think her stories challenge us as readers to view small-town, rural America as multifaceted - the opposite of the flattened picture pop culture tends to give us. I give this book 4.5 stars primarily because of personal preference; while I enjoyed Bales’s writing and the way she portrayed her characters, I would have liked to see each individual story feel a little more self-contained. Some stories contained scenes that I felt were set-up for the next story (more on structure below), and I personally like my short fiction to stand on its own a little more. Otherwise, if you’re a fan of literary fiction and want to read a more compassionate, multivalenced take on small-town America, I would highly recommend this collection.

Writing: Bales writes in a very accessible manner. Her sentences flow very well, and they aren’t bogged down by too much figurative language (as is characteristic of some lit fic). Instead, it’s easy to grasp what is happening in any given story and Bales balances showing and telling so the prose doesn’t feel mechanical. It’s the kind of style that I think most readers - regardless of background - will find enjoyable and engaging.

Perhaps my favorite thing about Bales’s writing is the way she evokes small town “feelings” (for lack of a better word). Most of the things that punched me in the gut were not outright declarations of “this town is poor” or “this kid is messed up,” but the little details that evoke atmosphere or mood without much ado. For example, there are sentences here and there about kids needing to be bussed to a different school, about people who commute long distances for jobs, about “bibles weighing [people] down like stones.” A lot is communicated in such little space, and Bales don’t hit you over the head with its significance - she lets it sink into your bones, so to speak, and it’s a technique I find very effective.

If I had any criticism, it would probably be that some stories were in first person, and I didn’t quite understand the creative value of using it. I’m admittedly a little biased on this one, though - first person almost always feels unnatural to me, and I’m always looking for what value it adds to the storytelling.

Plot: This book doesn’t have an overarching plot like a novel, and I’m not keen on reviewing every story individually (not to mention that would spoil so much of the book), so I’ll instead talk more broadly about the construction of Bales’s collection as a whole.

Bales does something very interesting in that her stories are united by setting. Each tale takes place in the small town of Pekolah (Oklahoma, I think), and most characters make multiple appearances. In this, her book reads like a composite novel (as Carrie Gessner notes in her Goodreads review), and I think the effect is a good one. It makes the small town “everyone knows everyone” (and their business) cliché feel real, but more than that, it shows off Bales’s ability to make form match function. If everyone knows each other, and the town really is that small, it makes sense that multiple characters would pop up multiple times or that the same events would be referenced across stories. I also really enjoyed that each story felt like an individual thread and that Bales was weaving those threads together to create a tapestry - a picture of a whole town, if you will. I don’t think I’ve seen that structure used in many other short story collections (though admittedly, my experience is limited), and I enjoyed it very much.

If I had any criticism, it would be that I wish some of these threads were a little more self-contained. Some stories felt like they were setting up others, and some had unclear “messages,” so to speak, that I wish were a little more overt. To Bales’s credit, she does comment on things like conversion therapy, religion, poverty, and the like, and I think these themes do come through in the work. I’m just coming from a background of literature that hits you over the head with its themes and morals, and I tend to like texts that are a little more heavy-handed. But if you like things to be a little more ambiguous or don’t like it when authors hold the reader’s hand, you might like this collection.

Characters: Bales’s characters are complex and nuanced in ways that I didn’t quite expect (though I should have known better than to doubt her). The opening story features an out lesbian, while subsequent stories showcase gay men, Indigenous characters, Trump-loving queer people, etc. I liked the way Bales portrayed these characters as flawed; not all of them are “nice” people, but all of them have something that readers can connect to, whether it’s Jack’s frustration and despair or Teddy’s resentment of (certain) White people. While Bales’s stories are not always uplifting and optimistic, the characters are always interesting, and I think they all work together to create a nuanced view of what small town life is like - not homogenous, but still familiar.

TL;DR: Pekolah Stories is a brilliant collection of short stories that treats small town, rural life with compassion while also implicitly criticizing religious zealotry, violence, and the like, exploring the nuances of family relationships, economic despair, community, and more.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

where can i read more about the devegetation of north africa? (reliable sources that you prefer)

Hey hi.

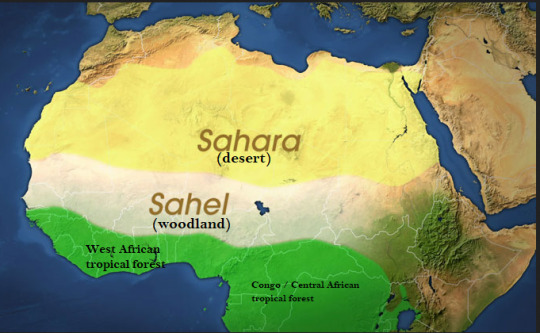

So just wanna be very clear that this is not really my “area of expertise.” (More focused on North American environmental history; most reading on North Africa limited to megafauna distribution range.) More like a fun side-interest that I revisit from time to time. And these resources are mostly just about the Sahel, specifically. Including the environmental history of the Holocene (past 10,000 years in the Sahel), and also the dynamic and drastic ecological change that took place between 1895-1960, during colonial and post-independence land management schemes. But some of the resources here also deal with the geography of the Sahara. (There is also an interesting history of the Sahara during the Holocene, when the desert was full of lakes and river courses. Up until the 1970s, there were still isolated populations of hippo and crocodile in remote Sahara lakes and oases.)

I’ll recommend some of the older “classics.” As usual, I’d try to recommend writing from local people who are explicitly willing to share their ecological knowledge. But a lot of my recommendations are unfortunately from academics. And I’m sorry for that.

Assuming you’re referencing this:

When searching online for environmental histories or local environmental knowledge case studies of the Sahel, I see a lot of stuff sponsored by NGOs, the UN, and US academia, which will emphasize “rediscovery” or “utility” of “using” traditional knowledge for “combating climate change,” and many mentions of the “green wall” proposals. I’ll also see “white savior complex” kind of stuff, which talks about “crises” and “civil wars” as if they’re “endemic” to the Sahel. But (just my opinion), I don’t like those resources. They engage in cultural appropriation (”acquiring” local Indigenous knowledge), superficial posturing (Euro-American academics using cute language about “local knowledge” without holistically contextualizing the devegetation), weird culturally-insensitive elitist chauvinism (continuously talking about “religious conflicts” and “civil wars” in North Africa and the “urgency” to use “agriculture” to establish stable economics and therefore “law and order”), and reductionism (talking about importance of halting southward desertification and expansion of the Sahara, without acknowledging role of World Bank, IMF, etc. in continuing to use lending/debt to hold West Africa hostage.) Part of my skepticism of these sources is because I’ve met and/or worked with agricultural specialists from institutions in the Sahel and environmental historians who had worked for many years in the region. (They’ve shared some really cool anecdotal stories about the sophistication of dryland gardening in the Sahel, and how local horticulturalists would laugh at the Euro-American corporate agricultural agents and USDA staff sent in with their special “space-age chemically-coated super-moisture-retaining” seed supplies after independence.)

Fair warning: Most of my recommendations are a little old, from the 1970s and 1980s. Two of the main drawbacks of these “outdated” sources: since their publication, scholars have since greatly expanded lit/research about both imperialism and traditional ecological knowledge. (West Africa had only been “independent” for a short period of time, and the hidden machinations of neocolonial institutions weren’t as clearly visible as they are to us, today, I’d imagine. And some academics, writing about the Sahel in the 1980s, weren’t as willingly to openly call-out major institutions.) But I think they provide a brief background for Sahel’s ecology and agroforestry/horticulture.

So both of these are available free, online, through the New Zealand Digital Library. (Don’t wanna link them here, but you can find them online pretty easily.)

Firstly, from 1983/1984, there is this summary of desertification, traditional environmental knowledge, traditional land use systems, and agroforestry in the Sahel: National Research Council. 1983. Agroforestry in the West African Sahel. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Something that was always exciting for me ...

Despite how dry and hot the Sahel is, fruit trees and gardens are actually very fertile and productive, for many reasons, mostly related to sophistication of local ecological knowledge of nutrient-replenishing relationships between different plants. An excerpt:

“Today, a number of agro-silvicultural systems appear to be practiced in the Sahel. Gardens are found within settlements where water is available, usually with a tree component that provides shade and shelter and, often, edible fruits or leaves. The same holds true for intensively managed, irrigated, and fertilized gardens near urban centers. Both subsistence home gardens and cash-generating market gardens are highly productive. Fruit and pod-bearing trees, shade trees, and hedges or living fences are the "forestry" components, sometimes supplemented by decorative woody plants. Mangoes, citrus trees, guavas, Zizyphus mauritiana (Indian jujube), cashews, palms, Ficus spp., and wild custard-apples are prominent kinds of fruit trees. Shade is often provided by Azadirachta indica or similar species, while fencing is provided by thorny species of Acacia and Prosopis, and by Commiphora africana, Euphorbia balsamifera, flowery shrubs such as Caesalpinia pulcherrima (paradise-flower), and other species.

Close to the settlements is a ring of suburban gardens, often irrigated, in which cassava, yams, maize, millet, sorghum, rice, groundnuts, and various vegetables are grown, for subsistence as well as sale, depending on the ecozone.”

---

Then this sounds more like what you might be looking for? Basically, a history of environmental knowledge and the ecological trends of the past 10,000 years in the Sahel.

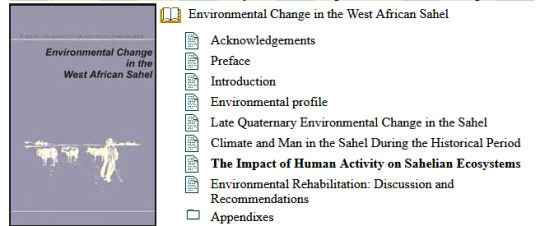

National Research Council. 1983. Environmental Change in the West African Sahel. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Though this report from 1983 is now kinda outdated, and has some iffy elitist and vaguely-chauvinist language at times, but it is still accessible, generally easy to read, concise, and it goes out of its way to say that 1970s drought and current environmental crises in the Sahel cannot be understood without addressing the early Holocene ecology of the Sahara/Sahel.

So the report emphasizes the importance of context, by addressing the drying of river courses and lakes in the Sahara of the Late Pleistocene, the early domestication of crops, the emergence of cattle and goat over-grazing, the importance of gum arabic and acacia trees in maintaining moisture in gardens, early trans-Sahara caravan travel, medievel geographical knowledge of the Sahara, etc.

“Because climatic change and variability are regular features of the Sahel, the native plant and animal communities of the region are generally well adapted to the range of climatic variation existing in the region. [...] Many efforts in "development" or modernization have also contributed to their plight. [...] In order to provide a better understanding of the role of human activity in modifying Sahelian ecosystems, this chapter briefly explores nine agents of anthropogenic change: bush fires, transSaharan trade, site preferences for settlements, gum arabic trade, agricultural expansion, proliferation of cattle, introduction of advanced firearms, development of modern transportation networks, and urbanization. These agents illustrate the breadth and diversity of the human impact on the region.”

----

Then there is this: Jeffrey A. Gritzner. The West African Sahel - Human Agency and Environmental Change. 1989.

And I also recommend the work of Jeffrey A. Gritzner. He’s American, but respectful and knows what he’s talking about. Gritzner works with dryland ecology; human ecology, especially relationships with plants/vegetation; environmental change during the Holocene (past 10 to 12,000 years); and traditional environmental knowledge. And he’s especially knowledgeable about the Sahel, North Africa, and Persia/the Middle East, where he worked with region-specific horticulture in the 1970s in Chad, Senegal, etc. during the peak of the drought, and had personal observations of post-independence neocolonial mismanagement and continued corporate monoculture from World Bank, IMF, etc. His writing contrasts local/traditional gardening/plant knowledge with imported corporate/neocolonial agriculture.

---

Beginning in about the 1990s, it seems to me that Euro-American geography/anthropology departments were much more willing to use words like “empire” and “neocolonialism” and more willing to call-out corporate bodies and institutions, so there are many better articles from after that period.

Keita, J. D. 1981. Plantations in the Sahel. Unasylva 33(134):25-29.

Winterbottom, R. T. 1980. Reforestration in the Sahel: Problems and strategies--An analysis of the problem of deforestation, and a review of the results of forestry projects in Upper Volta. Paper presented at the African Studies Association Annual Meeting, October 15-18, 1980, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Glantz, M. H., ed. 1976. The Politics of Natural Disasters: The Case of the Sahel Drought. Praeger, New York, New York, USA.

National Academy of Sciences. 1979. An Assessment of Agro-Forestry Potential Within the Environmental Framework of Mauritania. Staff Summary Report, Board on Science and Technology for International Development, Washington, D.C., USA.

Huzayyin, S. 1956. Changes in climate, vegetation, and human adjustment in the Saharo-Arabian belt with special reference to Africa. Pp. 304-323 in Man's Role in Changing the Face of the Earth, William L. Thomas, Jr., ed. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Vermeer, D. E. 1981. Collision of climate, cattle, and culture in Mauritania during the 1970s. Geographical Review 71(3):281-297.

Smith, A. B. 1980. Domesticated cattle in the Sahara and their introduction into West Africa. Pp. 489-501 in The Sahara and the Nile, M. A. J. Williams and H. Faure, eds. A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Again, these resources are mostly just about the Sahel.

Then, since the early 1990s, for better or more specific case studies of local-scale environmental knowledge, I think it might be easier or more fruitful to search based on subregion or specific plants. My perception is that, though much of the woodland and savanna ecology might be similar across the region, the Sahel is still spatially/geographically vast, stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. And so, there are so many different diverse communities of people, with long histories situated in place, and there are diverse local variations in approach to horticulture. So, if you’re more interested in traditional ecological knowledge and local food cultivation, it might be easier to pick a specific subregion of the Sahel, or to pick a favorite staple food, and then to search those keywords via a university library website, g00gle scholar, etc.

(About the distribution range and local extinction, in the Sahel, Sahara, and Mediterranean coast, of lion, cheetah, elephant, giraffe, rhino, desert hippos, the “sacred crocodile,” etc. More my cup of tea. I’ve got some maps and articles, I’ll try to put them into a list of resources, too.)

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Crow Winter - Karen McBride

In brief: Hazel Ellis has an English degree and no job, so she’s back home being a good daughter and grieving her father. Then Nanabush the trickster turns up, saying things like, “end of the world” and “destiny”, and people start talking about developing the quarry on the Ellis land.

Thoughts: This was a satisfying read, a story of a young woman finding her place, reconnecting with her heritage, and fighting injustice. It’s quiet, with tropes and beats that sneak up on you, and has a beautiful, positive portrayal of modern Indigenous life. There’s also some great dialogue. Unfortunately, I’ve read a lot of stories that use the same tropes and beats, and though McBride uses them well, they don’t seem to have much spark here. Still, it’s a solid debut and I’ll be interested to see where she goes from here.

My favourite parts, surprising nobody who knows me, were whenever Nanabush turned up, and the way McBride realizes the spirit world and its “magic”. Nanabush is wonderfully cranky and annoyingly cryptic (though I got frustrated a few times that he couldn’t just say something or understand where Hazel was coming from more), and McBride writes his crow body language wonderfully. And the spirit world? Lovely and eerie at the same time, definitely a timeless and separate world and exactly how it should be. The more magical elements of the story were great, and not overdone. I really liked how those worked and the sense of power behind them. There were a couple scenes where I thought, “Oh, that is cool.”

But enough about that. McBride’s also good with character. Her secondary characters shine especially, every one different and none of them playing to “type”. Even Hazel’s dad, who's only really seen in occasional flashbacks, is rounded and vibrant. Going along with the characterization are a strong ear for dialogue and an ability to create very solid, complex relationships. A lot of the conversations are snappy and realistic—McBride’s great at sass—and Hazel and her mom, to pick one example… that’s a mother and daughter, definitely.

That said, Hazel’s own personality didn’t always feel solid. Sometimes she was a believable twenty-something, and other times she seemed older and more jaded than she probably should have. Trying to get a handle on her was hard. I also struggled with some of her interactions with Nanabush—how long it had been since her last one, why she flipped between annoyance with him and a sort of angry, desperate need for his company, that sort of thing. I’m not sure if these are white reader problems, though. They certainly could be.

The same might go for my problem with the tropes and beats in general, or it could just be that I’ve read a lot of urban fantasy and know how these sorts of stories go. Even if McBride gets to the same places without the same kick as pure urban fantasy does, I was rarely surprised when one chapter had a moment of self-doubt or another featured an antagonist and a setback. That said, I appreciated that so much of the climax was still unexpected, and felt much the same as Hazel afterwards.

The final thing I liked about this book is McBride’s ability to interweave Hazel’s growing confidence in herself with the problems with the quarry, the white guy from town, and the spirit world. I loved seeing Hazel come into herself and her power and solve the mystery, but the parallels and complexities don’t stop there. McBride’s doing some interesting, clever things there, though it might be a white reader thing again that I felt they never quite clicked into place.

So yeah, there’s lots I liked about this, and some things that left me profoundly meh, and that evened out to an all right read. Can’t say I loved it or hated it. It’s a worthwhile read though, and like I said, a solid review. I suspect people who’re less familiar with urban fantasy plots would enjoy this more than I did.

To bear in mind: Contains racist and misguided white people, the past death of a parent, attempted suicide, and land rights … shenanigans, to put it nicely.

6.5/10

#booklr#adult booklr#book reviews#read in 2020#indigenous fiction#indigenous authors#can lit#canadian fiction#first peoples#authors of colour#diversity in fiction#crow winter#karen mcbride#ownvoices

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

yoooo while looking up stuff on izumo i found this article debunking the idea of japan being a “homogenous” nation and damn it’s interesting :o i mean, ofc i knew about that concept already but i just haven’t read anything that approached it from the “japan has ALWAYS been internally diverse” pov as opposed to tackling it only from the “because of the existence of indigenous ppl/foreign migration” pov. it actually kinda reminded me of our own history, like how there were many distinct countries/kingdoms back then and no singular but nebulous malay “race” (which is actually composed of many ethnic groups).

i’m just gonna save some quotes for my own reference, in case i wanna look further into this next time:

In my research, the term “Yamato Minzoku (people)” did not appear until the year 1888. Following the emergence of the term “Yamato Minzoku (people)”, the term “Izumo Minzoku (people)” also appeared in 1896.

-

After that, the KiKi myth was introduced in schools to justify the Emperor’s rule. However, about 30-40 % of the Kojiki is devoted to the Myth related to Izumo, which says that the emperor’s rule in Japan started when the Izumo gods surrendered their realms to the Yamato gods. Consequently, Meiji historians concluded that there was a country ruled by the Izumo people before the Yamato people came to Japan and that the Izumo were an indigenous people in Japan’s main island. [...]

However, there is another account from the oldest existing book in Japan, from early C.E.700. [...] According to the original Izumo Myth, there is entirely no relation between Okuninushi (Onamuch), Susano or the Sun Goddess. Onamuch, the supreme deity of Izumo myth [...] does not surrender the land of Izumo. He proclaims that he will continue to govern the country of Izumo while entrusting his other lands to the descendants of Amaterasu (the ancestor of the Yamato's king).

The Izumo myth also states that the Izumo gods built the Great Shrine (the oldest and biggest Shinto Shrine in Japan) for Onamuch, contrary to the Yamato myth that Amaterasu built it. The fact that descriptions in Izumo Fudoki are very different from the KiKi has been ignored in Japan’s historical education.

-

Many scholars have pointed out that Izumo religion is different from Ise (Yamato) as the former worships gods that are related to the sea, lakes and rivers (and is thus similar to religion in the Ryukyu (Okinawa) islands) while the latter worships gods related to the sun. It is said that Izumo’s god concept has a horizontal character (the gods come from the sea and have no hierarchy), while Yamato’s has a vertical character (the gods come down from heaven and have a hierarchy structured under Amaterasu who is said to be the ancestor of the Yamato King, emperor).

-

The Izumo ethnic identity is also seen in the “Izumo Nation Study”, written by Tokutani Toyonosuke, in Shimane Hyoron, 1934-1936 (18 issues). In this thesis, he states that “Every time when I met persons from other countries (within Japan) and heard their languages, I noticed they were extremely different from our Izumo language and I felt very strange.” [...] In fact, many authors have even recently asserted that Izumo is very different in history, religion and language from Yamato.

-

In the middle of the 19th century, the present Japanese archipelago (not including Okinawa and Hokkaido) was divided into 68 states and there was no Japanese national identity among ordinary people. Nitta Hitoshi writes in 1999 that “In the Edo period, what was recognized as ‘country’ were domain (han) governed by lords (Daimyo). A Samurai's loyalty was toward their Daimyo, and another domain was a ‘foreign country’. Therefore, even if other domains fought with a European country and lost, they regarded it as a foreign matter that had fundamentally no relation to them.”

-

Kyushu people, in general, tend not to recognize Japan as a homogeneous country not because of the existence of Ainu, Okinawan (Ryukyuan) or Koreans, but because they consider themselves different from the Yamato. My university colleague from Kumamoto, southern Kyushu, once said to me very naturally “I am the Kumaso," a people originally from East China Sea kulturkreis who had resisted Yamato’s aggression until the 7th century.

-

Nishitaka Totsu (1838-1915), an official of the Ministry of Education, wrote in 1873 in the “Ministry of Education Magazine” (文部省雑誌), “The languages of east and west regions are not mutually understandable.” [...] “There is no other country like Japan, whose territory is only 2400km wide from east to west (not including Hokkaido), in which the languages are so different and the people cannot communicate with each other”.

-

“When I took the train from Tokyo to Fukushima, a British man and a woman from Sendai were sitting next to me. The language of the Sendai woman was extremely hard to understand and we could not make conversation at all. On the other hand, I was able to talk with the Britisher a little since I understand a little English.”

-

A famous linguist, Kindaichi Haruhiko wrote in his book “Japanese Language” in 1957 that: If we brought the Kanto, Kansai, Tohoku, Kyushu, Kagoshima and other dialects to Europe, they would be regarded as separate independent languages”. At least, those differences are bigger than the difference between Spanish and Portuguese.

Nishikori Masahiro wrote in 1988 that “Until 20 or 30 years ago, young people (of Izumo) who went to the capital (Tokyo) used to be distressed by a language complex. Now young people can speak the standard language quite well”.

-

Hoshina Koichi wrote in 1898 in his thesis titled Regarding Dialect (方言に就て)that “In order to collect dialects, we have to decide on a language which should be regarded as standard”, “Therefore, we have to take a major language like Kyoto language or Tokyo language and formalize it as the standard one”. We should notice that even at this stage, Kyoto language was considered first. However, Kyoto language did not become the standard language and the Meiji Emperor lost his mother tongue. This fact also implies that the Emperor was not a real sovereign in modern Japan.

So, what is the standard language we are using now? It is an artificial language created in the early 20th century, based on "the words used by an educated middle-class family living in Yamanote area of Tokyo (where bureaucrats gathered)."

-

Sakaiya Taichi, argues in his book “Japan’s Rise and Fall”(日本の盛衰)published in 2002 that during the rapid economic growth era from 1950 to the 1960s, Japan adapted its society to standardized mass production and created the “optimal industrial society”.

In the field of education, they trained human resources (1) to be patient, (2) to be cooperative, (3) to possess common knowledge and skill, but (4) not to display originality or personality. In the field of regional structure, they aimed for the unification of information and culture by concentrating everything around Tokyo.

Thus, the contemporary national consciousness of the Japanese people is rooted in the suppression of an awareness of their own internal diversity.

#ugh i have a whole bunch of other stuff i need to be doing but well..............#whats new..............#-_-#/punches self the face#sotong txt#japanese history

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Being Both Colonized and Colonizer

First off, I don’t expect anyone to actually read this. This blog is a way for me to hone my writing skills while parsing through topics that I care deeply about. That said, I know that I’m making this work public, and as a result people may read it. If something I post here does spark a dialogue, I’ll be very grateful for whatever wisdom is shared with me.

Decolonization is a topic that I’m incredibly passionate about, but at the same time I know that it’s not a topic that I can really lead discussion on, particularly because I am by no means an expert. While I truly believe that decolonization is for everyone and can benefit everyone (except, perhaps, a small group of power-holders), it goes against the very principles of the concept to have settlers lead the conversation on stolen land. This is why I’ve chosen to leave the word “decolonization” out of the name of my blog, despite it being the primary framework from which I will be addressing a variety of topics.

One of the things I hope I can do here is share my perspective on how what Edgar Villanueva calls “the virus of colonization” has severed the sacred ties between people all over the world and their traditional medicines, or ways of healing. This tragedy is not unique to Turtle Island (North America) and the other European colonies, but in fact can be seen all over the world.

[In his book, Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance, Edgar Villanueva describes colonization as a “virus” and uses the framework of traditional medicine to talk about money.]

My background is primarily Irish and Ashkenazi Jewish, two ethnic groups with complex relationships to colonization. Both groups have suffered at the hands of colonizers while in turn becoming colonizers themselves. This is why Villanueva’s “virus” terminology makes so much sense. As people’s cultures are destroyed by colonization, they become infected with it and many of them in turn become part of the colonization machinery themselves. There are examples of this all over the world, including the Irish slavers in the Caribbean and American South, the Free Black American colonizers who founded the Republic of Liberia, and, perhaps most controversially, the State of Israel.

200 years ago, my Irish ancestors were among the first white settlers of what is now Arva, Ontario. As native Irish Catholics, they were forced into poverty and prohibited from owning land in the country where their ancestors were buried. Had they stayed, they likely would have fallen victim to the Irish Potato Famine - a crisis with a lie for a name that saw a million Irish starve to death due to the failure of a single crop while their English occupiers continued to reap financial benefits from their otherwise well-functioning agricultural system.

[Like many victims of colonization, the Irish were often portrayed as monkeys or apes in an attempt to dehumanize them.]

In Canada, my ancestors found opportunity in an unoccupied and fertile land, at the time covered in forest. The land was unoccupied because the “Attawandaron”, or “Neutral” Nation had been exterminated 150 years earlier, first by introduced disease, and then by the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). Both their surviving names were given to them by outsiders. “Neutral,” was given to them by French missionaries, in reference to their relative peace with neighbouring nations. “Attawandaron,” which translates roughly to “the people who talk funny” was given to them by the Wyandot (Huron), who spoke a different dialect of the same language. The name they called themselves has been lost.

On a base level, it can be tempting to find comfort in the fact that my ancestors did not participate in the genocide of the first peoples of the land my family still occupies, but regardless of whether or not they held the guns or spread the disease, the fact remains that to this day my family benefits from their extermination. I’m sharing this story not in an attempt to release myself or my ancestors from responsibility for the horrifying effects of colonization, but to illustrate its complexity. So many of us are both colonized and colonizers. As our own Indigeneity was taken from us, we also did our best to take it from others. If we recognize this, it can also help us to recognize the vital similarities in global Indigenous cultures, and their value to our modern world.

[The “Attawandaron”, or “Neutral” Nation occupied much of what is now Southwestern Ontario until their annihilation in the 1650s.]

So what does decolonization actually mean? I can tell you that for the first several months I was talking about it in front of my father, he was sure that it meant kicking all the white people out of Canada. While I’m sure that’s an attractive fantasy for many, it’s not a pragmatic or even achievable solution.

If someone with a deeper understanding happens to read this definition and finds it amiss, I’d very much appreciate being corrected, but my understanding is that decolonization, at its core, is about land sovereignty. It’s about the right not only to self-governance, but to governance over the land itself. Indigenous cultures all over the globe are defined by their relationships not only to each other but to the land. While someone with a colonizer mindset looks at the land and sees “natural resources” to reap and exploit, someone with an Indigenous perspective will look at the land and see a complex system of which they are a part. This perspective is necessary not only for the health of our species, but for the health of our burning planet. If all the governments of the world adopted an Indigenous mindset tomorrow, I have no doubt that the climate crisis would be quickly and easily solved.

Decolonization favours the idea of relational identities over individualism. Just as we are inextricably a part of the ecosystems in which we inhabit, we are also a part of our families and communities. Every Indigenous population on Earth that I’ve read about has some concept of this. On Turtle Island, we see this concept represented most often through the phrase “All My Relations,” but in Indigenous communities all over the world you will hear people referring to their kin by their relational title (for example “Auntie,” or “Sister”) instead of their name. Even in parts of Europe, we see this concept preserved in some naming conventions. Colonization, however, places much more emphasis on the individual than their relations. Perhaps unsurprisingly, those of us who live in colonial societies find ourselves at the centre of a “Loneliness Epidemic.”

[A 2018 survey found that nearly half of Americans report sometimes or always feeling alone or left out.]

While I truly believe that decolonization is the right path forward if we wish to save our burning planet, I am most interested in decolonization from a psychological perspective. I believe very strongly that the ancient medicines of story, ritual, and connection to nature are basic human needs, and that the mental health crises across the colonized world can be connected to their destruction. Luckily, these medicines are not lost. Like the Indigenous languages that have been reconstructed and saved, many of these medicines are only sleeping.

There’s much more that I hope to say on this topic as I educate myself and commit to learning in public. For now, I’d like to express gratitude to any readers who have found their way here and made it to the end of my first post. I hope that we can learn from each other and work together to build a better, more human world.

Go raibh maith agat, Jocelyn

#decolonization#colonization#social justice#mental health#loneliness#irish#canada#southwestern ontario

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

TFP Ratchet, Knockout, Shockwave, Soundwave, and TFA Prowl (his work could be his meditation or him studying nature) react to a bot reader who isn't the brightest, much like TFP Bulkhead in that they're more useful for strength than smarts, but does show interest in their work (the glances and occasional stares don't go overlooked). Who calls them over and lets them watch, or even teaches them what they're doing, who ignores it and lets them come on their own, and who's a mix of both, and so on?

Ratchet

- To begin with he finds it obstructive. He doesn’t need yetanother Bulkhead breaking things he needs, and yet, there’s something ratherendearing about the state of quiet attentiveness you enter when you’re tryingto subtly watch what he’s doing without him noticing. Of course, he noticesimmediately. There’s a reason you’re not first choice for stealth missions.

- He calls you over after the tenth time he catches you lookingcuriously his way as he tinkers with the ground bridge. There’s no need for youto clank around, finding excuses to pass by his work station and steal glancesfrom the corner of your optic. In fact, it’s much less distracting if you’djust stay still and watch – yip-ip-ip! Watch,not touch. It’s not that he doesn’t trust you, per se, and he is not a control freak despite what somehumans might say, but he’s not comfortable letting you get involved inimportant things that need to be done right, and it will all be done so muchquicker if he does it himself. That said, he’s happy to tell you what he’sdoing, and even talk you through some of the procedures he’s carrying out. Notthat he really expects you to understand, but clearly you won’t stop pesteringhim until he explains it.

- Eventually you become an assistant of sorts. You’ll runerrands for him, pass on messages, fetch and pass instruments (which you beginto learn by name) and even give advice to him on certain things. He won’t admitit, but you make yourself surprisingly useful and he values your company. Nomatter that you aren’t the most eloquent conversationalist, neither is he.He’ll even request your presence himself on occasion, it can be thankless workbeing the one who always stays behind at base and it’s nice to have someone acknowledginghis efforts.

Knockout

- He’s absolutely delighted with the attention. Even if it’s nothis flashy paintjob that’s catching your optic, he’s always proud to be insomeone’s spotlight. He points it out to Breakdown, any excuse to gloat istaken by him. Clearly his skills are just that good that even someone like you,the last bot anyone thought could show an interest in something so technical asthe medical profession, has become enraptured.

- You’re invited over to the medbay to observe him at work assoon as he gets the chance. He’ll strut and preen as he tells you about what hedoes and demonstrates for you. You don’t mind; he’s actually a very informativeand patient teacher, and willing to put up with the many, many questions youhave. The fact that he welcomes them only encourages you. As your presence inthe medbay gets more regular, he finds himself answering your questions byletting you have a go at repairs yourself. Only minor ones of course, and underhis constant supervision, but it turns out you’re quite experienced with yourhands having been on the battlefield and are capable enough to handle the taskof simple operations on your fellow ‘cons.

- Breakdown and yourself become fast friends as you find youhave much in common and some day you hope to become a partner to Knockout likehim. Knockout often jokes that his finish is never in danger while he’s luckyenough to have two bodyguards on the job. The two of you act in a tag team;when one is on a mission, the other will be assisting Knockout in the medbayand when Knockout and Breakdown are on amission together, you will stand in until they return. Knockout grows toappreciate your continued diligence in participating in his work and discovershe values your company as much as your help.

Shockwave

- It seems illogical to him that someone such as yourself wouldhave the slightest interest in his projects, and yet your intrigue is painfullyobvious as you make no effort to hide it, even resorting to blatant stares whenyou have nothing else to do. It doesn’t faze him in the slightest, and he wouldhave gone on ignoring you for eternity if you didn’t make the decision one dayto approach him yourself.

- He’s a busy mech, and what with the delicate nature of all hisexperiments he won’t ever let you get involved. He won’t stop you from watchingeither though, and lets you spend however much off-duty time you like lending akeen eye as he goes about monitoring chemicals, conducting research andupdating data pads. It becomes routine for you to simply sit and observe,occasionally asking a question but not expecting an answer, and more often thannot you don’t receive one.

- When he gives you the keycode to his lab it comes as rather asurprise – you had thought he’d want to keep you out as you believed he viewedyou as a nuisance, but it seems that was not the case. You express gratitude tothis and remain extra careful not to get in his way. Though it may take awhile, he responds to your questions more and more, and one day it turns into afull-blown conversation. Since then, the two of you will talk far morefrequently and become surprisingly close, much to the bafflement of every othermech on the nemesis.

Soundwave

- As the eyes and ears of the Decepticons, Soundwave catches onto your interest in his work from the moment it blossoms. As long as you don’tmeddle with his efficiency, he thinks little of it. He admires your loyalty toMegatron and the Decepticon cause and your strength on the battlefield, and aslong as you don’t hinder him in what he’s doing he sees no issue in allowingyou to watch, save for occasions when he’s working on a particularly secretiveproject.

- Some days, however, he finds his workload is particularlystrenuous, and even with Laserbeak’s assistance he cannot be in twenty placesat once despite his considerable skill. It occurs to him then that there may besome merit in requesting your aid with his work. You start by simply deliveringnon-sensitive messages but work your way up to more complicated tasks, spendingmore and more time with Soundwave at his workstation. When Megatron suggeststhat Soundwave takes you on as a more official helper, Soundwave is glad forit. He’s found you do wonders to lessen his workload even if you can barelycompute the more complicated areas of his job.

- It turns out yourgut instinct style of thinking comes in handy. While you may not be able tocrunch numbers like Shockwave or formulate plans like Starscream, you offer aunique overview and insight to goings-on in the Decepticon ranks whichSoundwave finds influences his outlook while performing surveillance on thetroops. More than once your intuition proves true such as with Starscream’s latestplot to overthrow Megatron, and Soundwave learns to respect you as a partnerand valued confidant, even if you never do quite manage to perform a reversequantum algorithm encryption.

Prowl

- It takes a while for Prowl to realise that you’re watching himwhen he meditates. He’s normally so deep in exploration of his innerconsciousness that he doesn’t particularly register your presence, but afterrealising that you often seem to be in the room when he comes back into focus itcomes to his attention that you, the vanguard and brawn of the Autobot team seemto have some curiosity about what he would have thought would seem like a veryboring activity to you.

- Of course, he’s eager to encourage your curiosity, and soinvites you to meditate with him one day. You fidget a great deal and struggleto slow your internal systems to the noiseless hum he’s perfected, but he’s a patientteacher and content to allow you to figure things out at your own pace. He’shonestly just glad to have someone take even the vaguest interest on what heconsiders a cemented part of his life and ideals and also someone to pass on MasterYoketron’s teachings to. When you show an additional interest in his studies onorganic life indigenous to Earth he’s thrilled – clearly you’re far more of akindred spirit than he initially would have guessed. It goes to show, oneshouldn’t judge a book by its cover.

- Often he’ll get caught up in explaining a particularlyfascinating discovery he’s made or even just a seemingly simple natural processand you can’t quite follow what he’s saying, but you try to be a diligentstudent. Though he’ll correct himself to more accessible language, you stillfind yourself asking Sari to clarify on ‘Phototropism’ (which is not to do withtaking pictures, much to your befuddlement) and ‘Pigmentation’ (No, not thosefarm animals, that’s different…). Despite the (in your opinion) needlessly complexwords and convoluted explanations, you don’t lose your curiosity. Prowl justmakes everything seem so interesting. Likewise, Prowl is content to re-explainthings as many times as is necessary. It’s good that you’re showing an interestin the planet they protect, and he’s determined to encourage it.

#TFP#TFA#Ratchet#Knockout#Shockwave#Soundwave#Prowl#Headcanon#Admin Snowy#Intelligence comes in many forms#I lack all of them

130 notes

·

View notes

Note

It'd be nice to see sort of a "Creole for beginners" post that talks about what terms are common in Vodou and maybe explains the grammar structure. I've noticed a lot of Creole I can mentally translate myself if I think about it long enough since many French words were taken into English awhile back, but French itself I don't actually know so sometimes it's quite a reach. The evolution of the language seems parallel with the evolution of Vodou and that's really interesting to me.

So, this ask has been sitting for awhile, and I’ve been thinking about it a lot as I am just finishing up an intensive month-long Kreyòl class.

Haitian Kreyòl/Kreyòl Ayisyen is a fascinating, gorgeous, succulent language. In some ways, it is super straightforward and in other ways, it is deeply complex as befits a language that has roots in Romance languages (more than one!), African languages (more than one!), and Indigenous languages. Like vodou, it is a language that embodies the history of Haiti and it has and does evolve as culture and the world advances.

Outside of Haiti, there is the idea that there is no common orthography/common way of speaking and utilizing the language. This is wrong wrong wrong. Largely, this stems from the fact that, until about 50 years ago, Kreyòl was almost entirely an oral only language because of colonialism–Kreyòl has only begun being taught in schools in the last decade, yet almost every Haitian speaks it fluently (the elite class speaks French, but that is largely a class marker–everyone knows Kreyòl). Many Haitians do not know how to write in Kreyòl, and write the best that they are able which leads to widely varied output….which leads outsiders to say that there is no commonly accepted orthography.

It would take a long, LONG time to really deconstruct and explain how Kreyòl works in practice so I’m not going to go there entirely, but here are some basics:

Kreyòl has 32 letter/symbols in its alphabet. Within that, there are 15 vowels/vowel sounds and 18 consonants/consonant sounds. Kreyòl only utilizes one accent (grave accent/aksan grav). Things with the alphabet that trip up Kreyòl learners who are native English speakers include:

‘C’ is not utilized except as a compound sound in ‘ch’, which is a soft sound like ‘shh’ and not a hard sound like ‘chair’.

‘U’ is not utilized except in compound sounds with other vowels.

‘G’ is always hard, never soft.

In Kreyòl, everything written is spoken–there are no silent letters, ever. A professor of mine terms Kreyòl as a truly democratic language; every letter has a sound that is expressed orally.

Basic sentence structure is Subject-Verb-Object (Li se yon bèl fi/She is a beautiful woman) and Noun-Adjective (Li bèl/She is beautiful). Within that structure:

Tenses and conditions (positive/negation) are assigned by separate verb markers/particles. Absense of a verb marker makes the tense automatically present.

Verbs largely do not conjugate, with some exceptions.

Articles are placed separately from the noun–definite articles are ALWAYS after the noun, indefinite articles are ALWAYS before the noun, and this gives speakers of other languages fits because it is different than the Romance languages most closely related to Kreyòl (my class had several folks who spoke several European-derived languages fluently, and the folks who spoke French or Spanish fluently struggled the most).

Adjectives are mostly after nouns, except when they are not.

Kreyòl is a language of double speak, both in general and in vodou. Words carry multiple meanings depending on context and tone, which can be a struggle when learning and can lead to confusion and sometimes awkward conversation. For example, the word for walk and market is spelled and pronounced the same way, the word for pen can also refer to internal genitalia and/or pubic hair in a female-assigned person in a somewhat rude/abrupt way, and utilizing a nasal versus open vowel sound in ‘I would like to meet you’ in Kreyòl changes that sentence to ‘I would like to fuck you’. Luckily, most Haitians are extremely accommodating to outsiders and understand that mistakes are honest mistakes (but they will laugh…).

Tone and composure (how you fix your face when you speak) is super important. How a sentence is said communicates as much, if not more, than the actual word. How I say ‘yon fanm sa a la’ can change ‘the woman over there’ to ‘can you believe this biiiiiiiitch over there’.

Kreyòl must be spoken with mouth open: no mumbling, etc. To get words across accurately, the mouth must open to make all the sounds.

The language is an independent standalone language with piece of French, Spanish, English, and multiple African languages visible. Much of the sentence structuring is African-derived, particularly from Bantu and Yoruba sources. There is a recent and evolving movement to claim identity of the language as Haitian only, not as Kreyòl.

The language also reflects the lived history of the country and it’s people. A lot of common phraseology reflects the history of enslavement; one of the more common ways to ask where someone lives in-country is ki bò ou ye/kibò ou ye, which translates to ‘what side are you from’. This is directly related to how enslaved Africans lived; plantations were huge and sprawling and so when enslaved Africans met others who were on the same plantation, how they related where they lived on the plantation was in that manner. Like vodou, the language is it’s own living history.

In the religion, language gets more complicated. French is utilized in some specific instances and some spirits, if/when they speak, only speak French, but Kreyòl is the liturgical language of the religion. All the songs and majority of the prayers are in Kreyòl, the community speaks Kreyòl, etc. In general, French is falling away as being a conversational language in Haiti–it is often used in business and medicine, but that’s about it.

There is also langaj, the language of the spirits. This is largely untranslatable language that spirits sometimes use in possession–it can be a combination of Kreyòl and African-descended sounds that are not complete in any African language. What langaj means is often private between the spirit and to whom that spirit is speaking, with the most common uses become accepted parlance (think ritual exclamations, like ‘ayibobo’, ‘awoche Nago’, ‘alaso’, ‘djarvodo/djavodo/djavado’).

Kreyòl is also spoken differently by spirits than by people. Kreyòl in general has many dialects throughout the country, and it follows that the spirits have many dialects as well. Kreyòl in general is spoken very fast by Haitians, and the spirits follow suit with that. In addition, some spirits speak more rural or localized forms of Kreyòl depending on what part of Haiti they are from. Some spirits speak very nasally, some speak so softly it almost sounds like they are only letting out soft breaths, some mix Kreyòl and langaj, some only speak/yell at top volume. All of that is super different than what a language program or even an in-person class can teach, and soKreyòl learned and used in religious settings is picked up contextually.

LearningKreyòl can be a daunting pursuit. Since it is SO orally focused, the best way is to learn orally in an immersive setting; either an intensive class or in Haiti or the Haitian community. There are some language programs, most of them are not great. Here’s what I like:

Ann Pale Kreyol by Albert Valdman is an excellent place to start. Though it is older and some of it is dated, it is still pretty foundational and his teaching methods are still used in classroom teaching. It is pricey for a used copy, but there are PDFs easily available online.

Valdman also produced a bilingual English-Haitian Kreyòl dictionary and it is FANTASTIC. I have several dictionaries and this is by far the best–you get definitions of words, what parts of speech they are, and how they are used both in English and in Kreyòl sentences. It is pricey and you could beat someone to death with it, but it is worth it for learning.

Pawol Lakay is as useful as Ann Pale Kreyol is, and it also comes with CDs (if you can threaten Amazon into making sure they send them with the book). It can be a little weak on sentence structure and what parts of speech are, but it’s good. There is a forthcoming language learning system for Kreyòl that beats the pants off of anything else on the market but it is not out yet.

MangoLanguages is good for basic hello/goodbye/my name is fluency, but I did not find it useful for conversational use. Good introduction, though, and the pronunciation in-program is pretty on-point. Most public library systems and college/university libraries have a free subscriptions for this, there are also pay options.

There are other books that are aimed at travelers and casual users which can be useful, but the above are the best resources I have seen so far. I do not like the Pimsleur system for Kreyòl at all, as it is super limited to essentially picking up women in Port-au-Prince which is great if that’s your jam but not useful for much of anything else. Youtube is full of Kreyòl movies and television and music, which is good to throw on in the background to absorb the sound and cadence of the language. Several professors have cautioned about listening to Haitian radio unless it originates in Haiti, saying that most Haitian radio originating in the US is a broadcast in a mix of Kreyòl and bad French, which can trip up a learner.

I hope this helps! Let me know if I can offer more info.

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 10 Reasons to Choose Oracle HCM Cloud

Today’s technology landscape is more complex than ever! However, on the other hand, business owners prefer to go along with trending technologies to remain competitive. Be it the retail sector or health care, each business relies on technology to rule the market. In addition to this, enterprises seek help from HRs to design a dynamic workforce strategy to fuel growth and retain the best talents.

Thanks to HR clouds, technology makes it way easier to create meaningful and engaging work experiences. Successful business leaders are already trusting the cloud to uplift HR’s role. According to the latest survey by PwC, 72% of companies have or will shortly have core HR applications in the cloud.