#nimbyism

Text

In defense of bureaucratic competence

Sure, sometimes it really does make sense to do your own research. There's times when you really do need to take personal responsibility for the way things are going. But there's limits. We live in a highly technical world, in which hundreds of esoteric, potentially lethal factors impinge on your life every day.

You can't "do your own research" to figure out whether all that stuff is safe and sound. Sure, you might be able to figure out whether a contractor's assurances about a new steel joist for your ceiling are credible, but after you do that, are you also going to independently audit the software in your car's antilock brakes?

How about the nutritional claims on your food and the sanitary conditions in the industrial kitchen it came out of? If those turn out to be inadequate, are you going to be able to validate the medical advice you get in the ER when you show up at 3AM with cholera? While you're trying to figure out the #HIPAAWaiver they stuck in your hand on the way in?

40 years ago, Ronald Reagan declared war on "the administrative state," and "government bureaucrats" have been the favored bogeyman of the American right ever since. Even if Steve Bannon hasn't managed to get you to froth about the "Deep State," there's a good chance that you've griped about red tape from time to time.

Not without reason, mind you. The fact that the government can make good rules doesn't mean it will. When we redid our kitchen this year, the city inspector added a bunch of arbitrary electrical outlets to the contractor's plans in places where neither we, nor any future owner, will every need them.

But the answer to bad regulation isn't no regulation. During the same kitchen reno, our contractor discovered that at some earlier time, someone had installed our kitchen windows without the accompanying vapor-barriers. In the decades since, the entire structure of our kitchen walls had rotted out. Not only was the entire front of our house one good earthquake away from collapsing – there were two half rotted verticals supporting the whole thing – but replacing the rotted walls added more than $10k to the project.

In other words, the problem isn't too much regulation, it's the wrong regulation. I want our city inspectors to make sure that contractors install vapor barriers, but to not demand superfluous electrical outlets.

Which raises the question: where do regulations come from? How do we get them right?

Regulation is, first and foremost, a truth-seeking exercise. There will never be one obvious answer to any sufficiently technical question. "Should this window have a vapor barrier?" is actually a complex question, needing to account for different window designs, different kinds of barriers, etc.

To make a regulation, regulators ask experts to weigh in. At the federal level, expert agencies like the DoT or the FCC or HHS will hold a "Notice of Inquiry," which is a way to say, "Hey, should we do something about this? If so, what should we do?"

Anyone can weigh in on these: independent technical experts, academics, large companies, lobbyists, industry associations, members of the public, hobbyist groups, and swivel-eyed loons. This produces a record from which the regulator crafts a draft regulation, which is published in something called a "Notice of Proposed Rulemaking."

The NPRM process looks a lot like the NOI process: the regulator publishes the rule, the public weighs in for a couple of rounds of comments, and the regulator then makes the rule (this is the federal process; state regulation and local ordinances vary, but they follow a similar template of collecting info, making a proposal, collecting feedback and finalizing the proposal).

These truth-seeking exercises need good input. Even very competent regulators won't know everything, and even the strongest theoretical foundation needs some evidence from the field. It's one thing to say, "Here's how your antilock braking software should work," but you also need to hear from mechanics who service cars, manufacturers, infosec specialists and drivers.

These people will disagree with each other, for good reasons and for bad ones. Some will be sincere but wrong. Some will want to make sure that their products or services are required – or that their competitors' products and services are prohibited.

It's the regulator's job to sort through these claims. But they don't have to go it alone: in an ideal world, the wrong people will be corrected by other parties in the docket, who will back up their claims with evidence.

So when the FCC proposes a Net Neutrality rule, the monopoly telcos and cable operators will pile in and insist that this is technically impossible, that there is no way to operate a functional ISP if the network management can't discriminate against traffic that is less profitable to the carrier. Now, this unity of perspective might reflect a bedrock truth ("Net Neutrality can't work") or a monopolists' convenient lie ("Net Neutrality is less profitable for us").

In a competitive market, there'd be lots of counterclaims with evidence from rivals: "Of course Net Neutrality is feasible, and here are our server logs to prove it!" But in a monopolized markets, those counterclaims come from micro-scale ISPs, or academics, or activists, or subscribers. These counterclaims are easy to dismiss ("what do you know about supporting 100 million users?"). That's doubly true when the regulator is motivated to give the monopolists what they want – either because they are hoping for a job in the industry after they quit government service, or because they came out of industry and plan to go back to it.

To make things worse, when an industry is heavily concentrated, it's easy for members of the ruling cartel – and their backers in government – to claim that the only people who truly understand the industry are its top insiders. Seen in that light, putting an industry veteran in charge of the industry's regulator isn't corrupt – it's sensible.

All of this leads to regulatory capture – when a regulator starts defending an industry from the public interest, instead of defending the public from the industry. The term "regulatory capture" has a checkered history. It comes out of a bizarre, far-right Chicago School ideology called "Public Choice Theory," whose goal is to eliminate regulation, not fix it.

In Public Choice Theory, the biggest companies in an industry have the strongest interest in capturing the regulator, and they will work harder – and have more resources – than anyone else, be they members of the public, workers, or smaller rivals. This inevitably leads to capture, where the state becomes an arm of the dominant companies, wielded by them to prevent competition:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/06/05/regulatory-capture/

This is regulatory nihilism. It supposes that the only reason you weren't killed by your dinner, or your antilock brakes, or your collapsing roof, is that you just got lucky – and not because we have actual, good, sound regulations that use evidence to protect us from the endless lethal risks we face. These nihilists suppose that making good regulation is either a myth – like ancient Egyptian sorcery – or a lost art – like the secret to embalming Pharaohs.

But it's clearly possible to make good regulations – especially if you don't allow companies to form monopolies or cartels. What's more, failing to make public regulations isn't the same as getting rid of regulation. In the absence of public regulation, we get private regulation, run by companies themselves.

Think of Amazon. For decades, the DoJ and FTC sat idly by while Amazon assembled and fortified its monopoly. Today, Amazon is the de facto e-commerce regulator. The company charges its independent sellers 45-51% in junk fees to sell on the platform, including $31b/year in "advertising" to determine who gets top billing in your searches. Vendors raise their Amazon prices in order to stay profitable in the face of these massive fees, and if they don't raise their prices at every other store and site, Amazon downranks them to oblivion, putting them out of business.

This is the crux of the FTC's case against Amazon: that they are picking winners and setting prices across the entire economy, including at every other retailer:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/25/greedflation/#commissar-bezos

The same is true for Google/Facebook, who decide which news and views you encounter; for Apple/Google, who decide which apps you can use, and so on. The choice is never "government regulation" or "no regulation" – it's always "government regulation" or "corporate regulation." You either live by rules made in public by democratically accountable bureaucrats, or rules made in private by shareholder-accountable executives.

You just can't solve this by "voting with your wallet." Think about the problem of robocalls. Nobody likes these spam calls, and worse, they're a vector for all kinds of fraud. Robocalls are mostly a problem with federation. The phone system is a network-of-networks, and your carrier is interconnected with carriers all over the world, sometimes through intermediaries that make it hard to know which network a call originates on.

Some of these carriers are spam-friendly. They make money by selling access to spammers and scammers. Others don't like spam, but they have lax or inadequate security measures to prevent robocalls. Others will simply be targets of opportunity: so large and well-resourced that they are irresistible to bad actors, who continuously probe their defenses and exploit overlooked flaws, which are quickly patched.

To stem the robocall tide, your phone company will have to block calls from bad actors, put sloppy or lazy carriers on notice to shape up or face blocks, and also tell the difference between good companies and bad ones.

There's no way you can figure this out on your own. How can you know whether your carrier is doing a good job at this? And even if your carrier wants to do this, only the largest, most powerful companies can manage it. Rogue carriers won't give a damn if some tiny micro-phone-company threatens them with a block if they don't shape up.

This is something that a large, powerful government agency is best suited to addressing. And thankfully, we have such an agency. Two years ago, the FCC demanded that phone companies submit plans for "robocall mitigation." Now, it's taking action:

https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2023/10/telcos-filed-blank-robocall-plans-with-fcc-and-got-away-with-it-for-2-years/

Specifically, the FCC has identified carriers – in the US and abroad – with deficient plans. Some of these plans are very deficient. National Cloud Communications of Texas sent the FCC a Windows Printer Test Page. Evernex (Pakistan) sent the FCC its "taxpayer profile inquiry" from a Pakistani state website. Viettel (Vietnam) sent in a slide presentation entitled "Making Smart Cities Vision a Reality." Canada's Humbolt VoIP sent an "indiscernible object." DomainerSuite submitted a blank sheet of paper scrawled with the word "NOTHING."

The FCC has now notified these carriers – and others with less egregious but still deficient submissions – that they have 14 days to fix this or they'll be cut off from the US telephone network.

This is a problem you don't fix with your wallet, but with your ballot. Effective, public-interest-motivated FCC regulators are a political choice. Trump appointed the cartoonishly evil Ajit Pai to run the FCC, and he oversaw a program of neglect and malice. Pai – a former Verizon lawyer – dismantled Net Neutrality after receiving millions of obviously fraudulent comments from stolen identities, lying about it, and then obstructing the NY Attorney General's investigation into the matter:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/08/31/and-drown-it/#starve-the-beast

The Biden administration has a much better FCC – though not as good as it could be, thanks to Biden hanging Gigi Sohn out to dry in the face of a homophobic smear campaign that ultimately led one of the best qualified nominees for FCC commissioner to walk away from the process:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/12/15/useful-idiotsuseful-idiots/#unrequited-love

Notwithstanding the tragic loss of Sohn's leadership in this vital agency, Biden's FCC – and its action on robocalls – illustrates the value of elections won with ballots, not wallets.

Self-regulation without state regulation inevitably devolves into farce. We're a quarter of a century into the commercial internet and the US still doesn't have a modern federal privacy law. The closest we've come is a disclosure rule, where companies can make up any policy they want, provided they describe it to you.

It doesn't take a genius to figure out how to cheat on this regulation. It's so simple, even a Meta lawyer can figure it out – which is why the Meta Quest VR headset has a privacy policy isn't merely awful, but long.

It will take you five hours to read the whole document and discover how badly you're being screwed. Go ahead, "do your own research":

https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/privacynotincluded/articles/annual-creep-o-meter/

The answer to bad regulation is good regulation, and the answer to incompetent regulators is competent ones. As Michael Lewis's Fifth Risk (published after Trump filled the administrative agencies with bootlickers, sociopaths and crooks) documented, these jobs demand competence:

https://memex.craphound.com/2018/11/27/the-fifth-risk-michael-lewis-explains-how-the-deep-state-is-just-nerds-versus-grifters/

For example, Lewis describes how a Washington State nuclear waste facility created as part of the Manhattan Project endangers the Columbia River, the source of 8 million Americans' drinking water. The nuclear waste cleanup is projected to take 100 years and cost 100 billion dollars. With stakes that high, we need competent bureaucrats overseeing the job.

The hacky conservative jokes comparing every government agency to the DMV are not descriptive so much as prescriptive. By slashing funding, imposing miserable working conditions, and demonizing the people who show up for work anyway, neoliberals have chased away many good people, and hamstrung those who stayed.

One of the most inspiring parts of the Biden administration is the large number of extremely competent, extremely principled agency personnel he appointed, and the speed and competence they've brought to their roles, to the great benefit of the American public:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/18/administrative-competence/#i-know-stuff

But leaders can only do so much – they also need staff. 40 years of attacks on US state capacity has left the administrative state in tatters, stretched paper-thin. In an excellent article, Noah Smith describes how a starveling American bureaucracy costs the American public a fortune:

https://www.noahpinion.blog/p/america-needs-a-bigger-better-bureaucracy

Even stripped of people and expertise, the US government still needs to get stuff done, so it outsources to nonprofits and consultancies. These are the source of much of the expense and delay in public projects. Take NYC's Second Avenue subway, a notoriously overbudget and late subway extension – "the most expensive mile of subway ever built." Consultants amounted to 20% of its costs, double what France or Italy would have spent. The MTA used to employ 1,600 project managers. Now it has 124 of them, overseeing $20b worth of projects. They hand that money to consultants, and even if they have the expertise to oversee the consultants' spending, they are stretched too thin to do a good job of it:

https://slate.com/business/2023/02/subway-costs-us-europe-public-transit-funds.html

When a public agency lacks competence, it ends up costing the public more. States with highly expert Departments of Transport order better projects, which need fewer changes, which adds up to massive costs savings and superior roads:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4522676

Other gaps in US regulation are plugged by nonprofits and citizen groups. Environmental rules like NEPA rely on the public to identify and object to environmental risks in public projects, from solar plants to new apartment complexes. NEPA and its state equivalents empower private actors to sue developers to block projects, even if they satisfy all environmental regulations, leading to years of expensive delay.

The answer to this isn't to dismantle environmental regulations – it's to create a robust expert bureaucracy that can enforce them instead of relying on NIMBYs. This is called "ministerial approval" – when skilled government workers oversee environmental compliance. Predictably, NIMBYs hate ministerial approval.

Which is not to say that there aren't problems with trusting public enforcers to ensure that big companies are following the law. Regulatory capture is real, and the more concentrated an industry is, the greater the risk of capture. We are living in a moment of shocking market concentration, thanks to 40 years of under-regulation:

https://www.openmarketsinstitute.org/learn/monopoly-by-the-numbers

Remember that five-hour privacy policy for a Meta VR headset? One answer to these eye-glazing garbage novellas presented as "privacy policies" is to simply ban certain privacy-invading activities. That way, you can skip the policy, knowing that clicking "I agree" won't expose you to undue risk.

This is the approach that Bennett Cyphers and I argue for in our EFF white-paper, "Privacy Without Monopoly":

https://www.eff.org/wp/interoperability-and-privacy

After all, even the companies that claim to be good for privacy aren't actually very good for privacy. Apple blocked Facebook from spying on iPhone owners, then sneakily turned on their own mass surveillance system, and lied about it:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/14/luxury-surveillance/#liar-liar

But as the European experiment with the GDPR has shown, public administrators can't be trusted to have the final word on privacy, because of regulatory capture. Big Tech companies like Google, Apple and Facebook pretend to be headquartered in corporate crime havens like Ireland and Luxembourg, where the regulators decline to enforce the law:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/15/finnegans-snooze/#dirty-old-town

It's only because of the GPDR has a private right of action – the right of individuals to sue to enforce their rights – that we're finally seeing the beginning of the end of commercial surveillance in Europe:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2022/07/americans-deserve-more-current-american-data-privacy-protection-act

It's true that NIMBYs can abuse private rights of action, bringing bad faith cases to slow or halt good projects. But just as the answer to bad regulations is good ones, so too is the answer to bad private rights of action good ones. SLAPP laws have shown us how to balance vexatious litigation with the public interest:

https://www.rcfp.org/resources/anti-slapp-laws/

We must get over our reflexive cynicism towards public administration. In my book The Internet Con, I lay out a set of public policy proposals for dismantling Big Tech and putting users back in charge of their digital lives:

https://www.versobooks.com/products/3035-the-internet-con

The most common objection I've heard since publishing the book is, "Sure, Big Tech has enshittified everything great about the internet, but how can we trust the government to fix it?"

We've been conditioned to think that lawmakers are too old, too calcified and too corrupt, to grasp the technical nuances required to regulate the internet. But just because Congress isn't made up of computer scientists, it doesn't mean that they can't pass good laws relating to computers. Congress isn't full of microbiologists, but we still manage to have safe drinking water (most of the time).

You can't just "do the research" or "vote with your wallet" to fix the internet. Bad laws – like the DMCA, which bans most kinds of reverse engineering – can land you in prison just for reconfiguring your own devices to serve you, rather than the shareholders of the companies that made them. You can't fix that yourself – you need a responsive, good, expert, capable government to fix it.

We can have that kind of government. It'll take some doing, because these questions are intrinsically hard to get right even without monopolies trying to capture their regulators. Even a president as flawed as Biden can be pushed into nominating good administrative personnel and taking decisive, progressive action:

https://doctorow.medium.com/joe-biden-is-headed-to-a-uaw-picket-line-in-detroit-f80bd0b372ab?sk=f3abdfd3f26d2f615ad9d2f1839bcc07

Biden may not be doing enough to suit your taste. I'm certainly furious with aspects of his presidency. The point isn't to lionize Biden – it's to point out that even very flawed leaders can be pushed into producing benefit for the American people. Think of how much more we can get if we don't give up on politics but instead demand even better leaders.

My next novel is The Lost Cause, coming out on November 14. It's about a generation of people who've grown up under good government – a historically unprecedented presidency that has passed the laws and made the policies we'll need to save our species and planet from the climate emergency:

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250865939/the-lost-cause

The action opens after the pendulum has swung back, with a new far-right presidency and an insurgency led by white nationalist militias and their offshore backers – seagoing anarcho-capitalist billionaires.

In the book, these forces figure out how to turn good regulations against the people they were meant to help. They file hundreds of simultaneous environmental challenges to refugee housing projects across the country, blocking the infill building that is providing homes for the people whose homes have been burned up in wildfires, washed away in floods, or rendered uninhabitable by drought.

I don't want to spoil the book here, but it shows how the protagonists pursue a multipronged defense, mixing direct action, civil disobedience, mass protest, court challenges and political pressure to fight back. What they don't do is give up on state capacity. When the state is corrupted by wreckers, they claw back control, rather than giving up on the idea of a competent and benevolent public system.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/10/23/getting-stuff-done/#praxis

#pluralistic#nerd harder#private right of action#privacy#robocalls#fcc#administrative competence#noah smith#spam#regulatory capture#public choice theory#nimbyism#the lost cause#the internet con#evidence based policy#small government#transit#praxis#antitrust#trustbusting#monopoly

379 notes

·

View notes

Note

Re zoning regulation reform: could you go into detail as what that would look like in terms of wiping the slate clean. I feel like it would be better to go the houston route and just be zoning free

You do not want to go the Houston route.

youtube

Houston may claim to be "zoning-free" - and to be fair, it doesn't have some of the more common regulations on land use, or density, or height restrictions (more on this in a minute) - but the reality is far more complicated and the status quo is not one that's friendly to the interests of working-class and poor residents, or to the possibility of sustainable urbanism.

The answer to NIMBYism isn't to abolish all regulations and let the free market rip, it's to surgically target zoning, planning, and litigation that is used against affordable housing, public/social housing, mass transit, clean energy, and walkable neighborhoods, and to replace it with new forms of regulation that encourage these forms of development.

So let's take take these categories in order.

Zoning

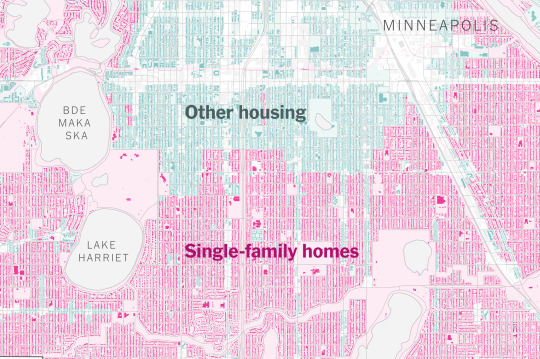

As I tell my Urban Studies students, zoning is both one of the most subtle and yet comprehensive ways in which the state shapes the urban environment - but historically it has been used almost exclusively in the interests of racism and classism. Reforming zoning requires going over the code with a fine-toothed comb to single out all the many ways in which zoning is used to make affordable housing impossible:

The most important one to tackle first is density zoning and building heights limitations. The former directly limits how many buildings you can have per unit of land (usually per acre), while the latter limits how big the buildings can be (expressed either as the number of stories or the number of feet, or as both). Closely associated with these zoning regulations are minimum lot size regulations (which regulate how much land each individual parcel of real estate has to cover, and thus how many how many housing units can be built in a given area), and lot coverage, setbacks, and minimum yard requirements (which limit how much square footage of a lot can be built on, and what kinds of structures you can build).

the other big one is use zoning. To begin with, we need to phase out "single use" zoning that designates certain areas as exclusively residential or commercial or industrial (a major factor that drives car-centric development, makes walkable neighborhoods impossible, and discourages the "insula" style apartment building that has been the core of urbanism since Ancient Rome) in favor of "mixed use" zoning that allows for neighborhoods that combine residential and commercial uses. Equally importantly, we need to eliminate single-family zoning and adopt zoning rules that allow for a mix of different kinds of housing (ADUs, duplexes and triplexes, rowhouses/terraced houses, apartment buildings).

finally, the most insidious zoning requirements are seemingly incidental regulations. For example, mandatory parking minimums not only prioitize car-dependent versus transit-oriented development but also eat up huge amounts of space per lot. The most nakedly classist is "unrelated persons" zoning, which is used to prevent poorer people from subdividing houses into apartments, which zaps young people who are looking to be roommates and older people looking to finance their retirements by running boarding houses or taking in lodgers, as well as landlords looking to convert houses from owner-occupied to rental properties.

So I would argue that the goal of reform should be not to eliminate zoning, but rather to establish model zoning codes that have been stripped of the historical legacies of racism and classism.

Planning

Similar to how zoning shouldn't be abolished but reformed, the correct approach to planning isn't to abolish planning departments wholesale, but to streamline the planning process - because the problem is that right now the planning process is too slow, which raises the costs of all kinds of development (we're focusing on housing right now, but the same holds true for clean energy projects), and it allows NIMBY groups to abuse the public hearings and environmental review process to block projects that are good for the environment and working-class and poor people but bad for affluent homeowners.

As those Ezra Klein interviews indicate, this is beginning to change due to a combination of reforms at both the state and federal level to speed up the CEQA and EPA environmental review process in a number of ways. For example, one change that's being made is to require planning agencies and environmental agencies to report on the environmental impact of not doing a project as well, to shift the discussion away from petty complaints about noise and traffic and "neighborhood character" (i.e, coded racism and classism) and towards real discussions of social and environmental justice.

At the same time, more is needed - especially to reform the public hearing process. While originally intended by Jane Jacobs and other activists in the 1970s as a democratic reform that would give local communities a voice in the planning process, "participatory planning" has become a way for special interests to exercise an unaccountable veto power over development. Because younger, poorer and more working class, and communities of color often don't have time to attend public hearing sessions during the workday, these meetings become dominated by older, whiter, and richer residents who claim to speak for the whole of the community.

Moreover, because community boards are appointed rather than elected and public hearings operate on a first-come-first-serve basis, an unrepresentative minority can create a false impression of community opposition by "stacking the mike" and dialing up their level of militancy and aggression in the face of elected officials and civil servants who want to avoid controversy. (It's a classic case of diffuse versus concentrated interests, something that I spend a lot of classroom time making sure that my students learn.)

Again, the point shouldn't be to eliminate public hearings and other forms of participatory planning, but to reform them so that they're more representative (shifting public hearings to weekends and allowing people to comment via Zoom and other online forums, conducting surveys of community opinion, using a progressive stack and requiring equal time between pro and anti speakers, etc.) and to streamline the review process for model projects in categories like affordable housing, clean energy, mass transit, etc.

Litigation

Alongside the main planning process, there is also a need to reform the litigation process around development. In addition to traditional tort lawsuits from property owners claiming damage to their property from development, a lot of planning and environemntal legislation allows for private groups to sue over a host of issues - whether the agency followed the correct procedures, whether it took into account concerns about this impact or that impact, and so forth.

As we saw with the case of Berkeley NIMBYs who used CEQA to block student housing projects over environmental impacts around "noise," this process can be used to either block projects outright, or even if the NIMBYs eventually lose in court, to draw out the process until projects fall apart due to lack of funding or the proponents simply lose their patience and give up.

This is why we're starting to see significant reforms to both state and federal legislation to streamline the litigation process. The categorical exemptions from review that I discussed above also have implications for litigation - you can't sue over reviews that didn't happen - but there are also efforts to speed up the litigation process through reducing what counts as "administrative record" or by putting a nine-month cap on court proceedings.

Again, this is an area where you have to be very surgical in your changes. Especially when the politics of the issue divide environmental groups and create odd coalitions between labor, business, climate change activists, and anti-regulation conservatives, you have to be careful that the changes you are making benefit affordable housing, clean energy, mass transit and the like, not oil pipelines and suburban sprawl.

#public policy#housing#zoning#policy history#urban planning#public housing#social housing#yimbys#yimbyism#affordable housing#urban studies#urbanism#houston#nimbyism#nimbys#environment#climate change#clean energy

93 notes

·

View notes

Link

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

NIMBY Mom

#nimby#nimbyism#unreality#made-up aesthetic#nonsense aesthetic#aesthetic#aesthetics#aesthetic moodboard#moodboard aesthetic

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"...But last August, the branch cut off its Wi-Fi after hours. It’s the only public library branch in the city that discontinues Wi-Fi at night, and the policy continues today, despite a simultaneous citywide push to increase internet access for San Franciscans with lower incomes."

...sigh...

#libraries#public libraries#California libraries#San Francisco Public Libraries#libraries as public utilities#unhoused people#low-income people#working class people#wireless#wifi#NIMBYism

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The YIMBY movement annoys a lot of people who are highly engaged with politics because we are living in a time of intense political polarization, and YIMBYism is not aligned with either pole.

But the core YIMBY thesis that quantitative restrictions on housing production are costly to the economy and harmful to society is true. The upshot of this is that a lot of smart, highly engaged people want to express negative sentiments about YIMBYism that don’t involve directly contradicting the core YIMBY thesis since they are too smart to deny its veracity. The result is a lot of tone-policing and concern-trolling where people express the idea that YIMBYs are doing this or that wrong, ideas that normally amount to “I wish you’d be less focused on your goal” or “I wish you’d do more to align yourself with my camp in the polarization dynamic.”

🔥🔥🔥

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The struggle to build homes for 42 unsheltered people in Atlanta

A development offering permanent supportive housing to help 42 individuals transition out of homelessness is getting pushback in Atlanta’s Reynoldstown neighborhood.

Why? "Parking" and "traffic" and various other excuses are being voiced. A neighborhood vote happens Monday.

Axios Atlanta has the story.

This is a MARTA-served, walkable area. People transitioning from homelessness would benefit from the specific amenities here. It's especially disappointing to see parking & traffic-flow concerns be used to oppose the proposal. Hopefully sanity will prevail.

Three things to know about the approval of the project:

1.) No rezoning is needed, so there's no zoning vote.

2.) Atlanta Housing (AH) does have to approve the use of vouchers for the housing. Though AH doesn't require a 'yes' vote from the neighborhood in order to approve the vouchers, they do require a vote to happen as a form of engagement.

3.) But...Invest Atlanta (IA) will likely look at that neighborhood vote and consider it when making their own decision on whether to approve the requested bond funding for the project.

So the only approval that has to happen for this project to move forward is Invest Atlanta's vote on the bond funding, and Atlanta Housing's allowance of vouchers.

It's possible that the neighborhood vote will sway those decisions one way or another. But it's not necessary for AH or IA to adhere to the neighborhood vote.

Kudos to the development group, Stryant Investments, for working through this process in an effort to provide housing for people experiencing homelessness.

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

Note: This article is about Australia, but it’s pretty much the same issue anywhere you go, whether australia, india, or the US: People don’t wan’t powerlines or or near their property.

The problem is that we absolutely need it to achieve net zero.

most of the people affected are farmers, who have complained that it messes with crops (which has no scientific support, at least not yet) and that it looks bad (which can also sometimes affect revenue if their farms are being used for cabins, events, etc.)

On the other hand: we have the oncoming destruction of the biosphere.

In this article, many of the farmers complained that there was insufficient reward for the use of their property, and I think that is a super fair claim and they should be reimbursed well. However, many seem to be just against it in principle, regardless of compensation. They feel they have a right to their land, and that completely demolishes every else’s right to a livable planet.

In short, it’s a form of NIMBYism. And like with housing, NIMBYism is here again hurting society at large so that some people can maintain absolute ownership and rights over a slice of the earth.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.newstatesman.com/comment/2023/06/deadly-cost-nimbyism-children-housing

Great article on the housing crisis in the UK. Paid site so use 12ft

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What the media won’t show you! ‼️‼️‼️👀👀👀

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm a big fan of building commie blocks to ameliorate the US housing crisis -- and putting them in the public parks that were stolen from other communities to give colonisers some trees to look at -- but what policies should be enacted to get suburbanites into beautiful and efficient bedspace apartments with kitchens and washrooms shared by a floor?

As a good social democrat, I'm contractually obligated to prefer Red Vienna to your proper commie block. Short of a complete class revolution that completely upends the social hierarchy, a significant part of ensuring that social housing pulls off being "a living tapestry of a mixed community" is building it to middle-class standards (including aesthetic standards) so that people with the money to find alternatives don't all leave. Art Deco is a hell of a lot chic-er than the boring minimalist crap that luxury developers are getting away with these days.

Also, don't build them in parks: green space is not only important for environmental sustainability but also the health and mental health of working-class and poor communities who can't afford houses in the suburbs, and we should be encouraging in-fill development instead. (Build them on golf courses instead, because they are classist, invasive, artificial monocultures that do nothing for the environment.)

In terms of how to make suburbia more in synch with dense, sustainable social housing, there are a number of necessary changes:

Commuter rail: suburbs predate the car by a fair few decades, and originally sprung up along the routes of commuter rail lines. Well, it turns out that transit-oriented development and dense transit corridors go hand-in-hand: if you can build higher-density units near transit lines, people will use mass transit to commute, and if there are well-planned areas of higher density around major urban areas, the increased number of commuters can support more regular transit services.

Planning/zoning/ligitation revolution: as I mentioned in my student housing post, one of the major reasons why it's so hard to build affordable housing projects is that local NIMBY groups use every legal tool in the book to bury them. So there needs to be pretty comprehensive reforms of zoning regulations (banning single-family zoning, reducing set-backs and eliminating mandatory parking, getting rid of "unrelated persons" limitations, getting rid of building heights limits, etc.), standardization of the permitting and development approval process, streamlining of the public comment/hearing process and environmental review process for model projects, and extreme limits on litigation for model projects.

Financing reform: as I sort of imply in my Red Vienna section above, a big part of making social housing/public housing successful and avoiding replicating or increasing class and racial segregation is adhering to middle-class minimum standards. This has important knock-on implications:

you need to eliminate requirements for absolute lowest possible land costs (which restrict social housing to economically and socially isolated areas).

you need to raise allowable construction costs, so that you can achieve those aesthetic standards and avoid corner-cutting like smaller rooms and lower ceilings, single-thickness walls/floors/ceilings, no doors on cabinets or closets, cheap cladding and wiring and pipes and other building materials, low-quality insulation and HVAC, etc. Not only do middle-class folks notice this stuff and go elsewhere, but it's all penny-wise and pound-foolish, because cheap construction runs down faster which increases maintenance costs, and sometimes it just straight-up kills people.

you need to adequately finance maintenance, services, and amenities. This is crucial to keeping tenants with deeper pockets, but it's also another one of those things where penny-pinching is counter-productive in the long-run. The more you save on maintenance costs, the faster the buildings run down and the more expensive repairs you have to make. The more you save on services like superintendants and doormen, the more your tenants end up having to spend on handymen and the more you have to spend on police and repair costs. And so forth.

And there is a real potential here for all kinds of positive feedback loops: spending money on achieving higher standards of construction and operation means that you can hang onto and attract higher-income tenants, which means you can have sliding scale rents that cross-subsidize tenants and pay for higher construction and operating costs, and the poor and working class tenants who couldn't have paid for those higher costs and amenities on their own enjoy a "positive externality" for once.

#public policy#public housing#social housing#social democracy#urban development#urbanism#urban planning#urban studies#housing#nimbyism#nimby#red vienna#commie blocks

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

The NIMBYs are at it again. There’s a proposal to develop a 1MW solar plant on a piece of land between my town and the next. Adjacent residents are up in arms, apparently because they have already enjoyed the benefit of adjacency for years without payment or responsibility for it. That has, of course, turned into a sense of entitlement and control over any future disposition of that land. Also true to form, people who never gave one milli-shit about forestry or ecosystem diversity before have become instant experts, now that it suits them to use those causes for their own benefit.

Personally, I think those people should just eat it. Be grateful for what they have already been allowed to reap without sowing. Representation without taxation is also tyranny; it’s the separation of the two that’s the problem, not the existence of either.

Yes, I’d like to see an analysis of how the CO₂ reduction from solar (vs. fossil fuels) compares to the loss of some trees, but I doubt that would come out in the squatters’ favor. We’d also have to factor in the fact that this is local power, less subject to problems with - or attacks against - the regional grid. And lastly, let’s consider that the owner of that land has some right to develop it. Would the abutters perhaps prefer that it be developed as yet another traffic-snarling office park or big-box store? Solar panels seem like one of the most benign possibilities even for them. The project seems like a net positive for the community, and to the extent that the community should be able to over-ride the owners at all it should not be for the benefit of only a few.

BTW, the same company also owns an adjacent office park and associated parking. I almost worked there once, when it housed Kendall Square Research. The one valid objection I’d consider to their development plan is that they should start by putting solar panels over all that first, and only then consider developing the currently vacant land. I’m not an instant expert on energy or environmental policy either, but it seems to me that putting solar on already disrupted land is generally preferable to disrupting new land regardless of where it is or who lives adjacent to it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

#writing#writing community#humor#bizarro#comedy#humorist#creative writing#lgbt#lgbt community#lgbt creator#weird#news#satire#homeless#homelessness#nimbyism#nimby#housing

0 notes

Text

Another step forward! I have high hopes.

This project has been simmering slowly and has brought all kinds of "concerned neighbours" out of the woodwork... (read: affluent mostly-white NIMBYs who read Indigenous and social housing and immediately panic about stereotypical substance and mental health issues, Having Our Community Changed By Not-Affluent-Mostly-White-People and Won't Someone Please Think Of The Property Values?)

But the nice part is that they are a small and loud group, and everyone else is pretty much on the "shrug" to "ABOUT TIME" end of the slider.

Highlights below for TL;DR:

The Jericho Lands proposal — first revealed in 2021 after work began in 2016 — includes a large housing project featuring dozens of buildings, a mix of community centres, park land and wilderness spaces, along with potential for a SkyTrain station if the Millennium Line is extended to the University of British Columbia.

The Jericho Lands area is currently home to a former garrison, several dozen homes leased to military families, and a private school. The site itself is owned by the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations — whose unceded territories Vancouver is built on — in partnership with the Canada Lands Company, a federal Crown corporation.

Around 20 per cent of the housing on the site — approximately 2,600 units — will be set aside for social housing, with a further 1,300 units for secured-market and below-market rental housing.

The project is called ʔəy̓ alməxʷ (ee-yal-mugh) in the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ language, and Iy̓ álmexw (i-yal-mugh) in the Squamish language

0 notes