#robespierre novel

Text

"He was the perfect little brother and followed Maximilien everywhere." ~The Incorruptible, Corrupted

I know it's a day late, but here's a lil doodle for Bon Bon's birthday. Joyeux anniversaire to the best little brother in history (other than my own 3)

#frev#french revolution#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#bonbon#bonbon robespierre#Augustin Robespierre#Robespierre brothers#robespierre novel#the incorruptible corrupted#art#digital art#fanart

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean Artarit: Robespierre was a repressed homosexual.

Olivier Dutaillis: YES! He liked watching the young, joyful, sturdy, pretty carpenters who worked for Maurice Duplay, often shirtless or with their clothes sticking to their muscles with sweat!...AND he also liked Saint-Just, who looked like an angel! AND WAS A GOTH!!!

Artarit:......

Dutaillis: He was a repressed homosexual of many tastes.

#currently flipping throught Dutaillis's novel more on that later#Dutaillis actually cites Artarit as source and says he got the idea of Robespierre's 'repressed homosexuality' from Artarit's book#also the shirtless description is really like that#sounds like it's Dutaillis who has the hots for the carpenters

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Working on Louis XVI ✍🏻🇨🇵

#french revolution#louis antoine de saint just#maximilien robespierre#camille desmoulins#frev history#frev#revolution francaise#artwork#digital artwork#graphic novel#louis xvi#marie antoinette#la revolution francaise#french history#comics#comicart#original comic#character design

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

This book lowkey scares me. What is it about. It has no plot description and I'm not sure i want to just. Read it.

#maximilien robespierre#This looks like a shitty romance novel#Will i read it? I dunno man#Maybe#I'll keep y'all updated

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE PLUTO IN SAGITTARIUS GENERATION

Born at the start of Globalization, November 10, 1995 - January 25, 2008

I’ve been talking a lot of shit on here about the Pluto in Sagittarius generation. And while I still think my irritations are justified (lol,) I gotta make it up by doing a complete breakdown. Afterall, this is the generation I belong to.

1995: NASA's Galileo spacecraft arrives at Jupiter

With Pluto in Sagittarius, this is a generation full of creatives, visionaries, academics, philosophers and rebels. We’re all about big ideas and moral philosophy. We’ve had the internet within our fingertips our entire lives, an unlimited database of knowledge and social interconnectivity. I remember a teacher once told me that we were the most educated group of humans humanity has ever seen. And this is true, by middle school many of us were walking around with cellphones in our pockets more powerful than computers built in the 80’s. Through technology, we were able to discover the world at an incredibly young age.

We have a lot in common with the Pluto in Leo generation (Baby Boomers,) being that both generations are ruled by fire signs. However what differentiates us is that the Pluto in Leo generation is focused on the self (Sun,) and the Pluto in Sagittarius generation is focused on the collective (Jupiter.) We project a sense of optimism despite having such large ambitions. This will serve as an inspiration for future generations.

Most of us have parents belonging to the Pluto in the Libra Generation. They raised us with values centered on equality and justice.

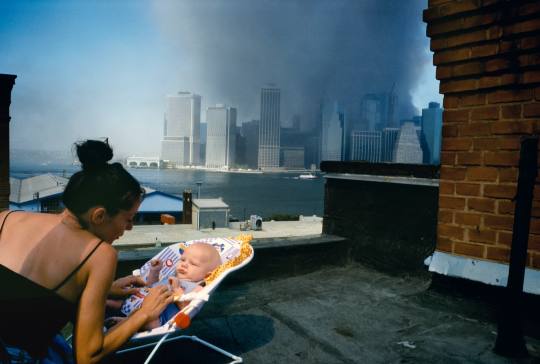

We grew up amongst explosive world events: First Internet Meme (1996), Google (1998), Columbine (1998), The Second Congo War (1998), Kosovo Genocide (1999), Launch of International Space Station (2000), 9/11 (2001), Invasion of Iraq (2003), Darfur (2003), Boxing Day Tsunami (2004), Facebook (2004), London Bombings (2005), iPhone (2007), America's first black President (2008), Global Economic Downturn (2008).

Pluto in Capricorn frames our coming of age story. Our teenage years were harsh and depressing. It was an isolating experience that did not involve much fun. For many people born with a Sagittarius Pluto, their adolescence is defined by a Global Pandemic in which all movement was restricted. These years also put into focus old frameworks that must be destroyed and cast aside. We feel punished, and now we are angry.

The Pluto In Scorpio Generation is coming through and uprooting all these frameworks before passing the torch onto us. We will be the ones to come up with blueprints for new ideologies and ways of thinking. We’re aiming forward and casting an arrow for future generations to follow.

Past events that occurred while Pluto was in Sagittarius: The Burning of the Library of Alexandria (272), first novel published in Japan (1010), Sorbonne founded (1257), first use of eyeglasses (1268), Columbus sets sail (1502), the birth of Nostradamus (1503), invention of sign language (1749), the first encyclopedia (1751).

Past figures born while Pluto was in Sagittarius: Constantine I (272), Dante Aligheri (1265), Goethe (1749), James Madison (1751), Alexander Hamilton (1755), Marie Antoinette (1755), Mozart (1756,) William Blake (1757), Robespierre (1758).

#pluto in sagittarius#sagittarius pluto#astrology#astrology placements#astro community#astro observations#birth chart#astro notes#astrology observations#astrology tumblr#natal chart#natal astrology#Sagittarius#astrology signs#astrological observations#astrology notes#astro placements#astrology facts#birth chart placements#birth chart readings#birth chart analysis#natal chart analysis#natal chart reading#pluto#pluto astrology#pluto placement#pluto placements#generation z#gen z

980 notes

·

View notes

Note

re: tags on labor in historical fiction post, would be very interested to hear what the four examples you mentioned are!!

ok u know what that tag WAS bait, thank you for taking it. technically speaking these aren't works dealing strictly with labor in historical fiction, they are my four treasured examples of BUREAUCRAT FICTION (so not NOT about labor in history?) i was gonna try to make this post pithy and short but then i remembered how extremely passionate i am about this microgenre i made up. so sorry.

bureaucrat fiction is not limited by genre or format but criteria for inclusion are as follows: long and detour-filled story about functionary on the outside of society finding unexpected success within a ponderously large and powerful System/exploring themes of class and physicality and work and autonomy and what it means to hold power over others beneath the heartless crushing wheels of empire/sad little man does paperwork. also typically long as hell. should include at least one scene where the protagonist is unironically applauded-perhaps for the first time in their life-for filling out a form really good. without further ado:

soldier's heart by alex51324. the bureaucracy: british army medical corps during wwi. the bureacrat: mean gay footman/new ramc recruit thomas barrow. YEAH it's a downton abbey fic YEAH it's a masterpiece. i've talked about it before at length, my love has not faded. the crowning moment of bureaucracy is a long interlude where thomas optimizes the hospital laundry (this actually happens twice or maybe three times)

hands of the emperor by victoria goddard. the bureaucracy: crumbling fantasy empire some time after magical apocalypse. the bureacrat: passionate late-career clerk from the hinterlands cliopher mdang. i reread this book every winter bc it is as a warm bath for my SAD-addled brain and every time i neglect all my responsibilities to read all nine billion pages in three days. it puts abt 93% of the worldbuilding momentum into elaborating all of the ministries and secretaries and audits necessary to run a global government and like 7% into the magic and stuff. there are also several charming companion novellas and an equally long sequel that dives more into the central relationship between cliopher and the emperor which i highly recommend if you like gentle old man yaoi and/or magic, but there's more bureaucracy in HOTE.

the cromwell trilogy by hilary mantel. the bureaucracy: court of henry viii. the bureaucrat: thomas cromwell, the real guy. curveball! it's critically acclaimed booker prize winning rpf novel wolf hall! mantel is really interested in particular ways of gaining and maintaining power in delicate and labyrinthine systems like the tudor court, specifically in strongmen who use both physical intimidation and metaphysical manipulation to succeed. under these conditions i do think my best friend long-dead historical personage thomas cromwell counts as Bureaucrat Fiction (as do danton and robespierre in a place of greater safety. bonus rec.)

going postal by terry pratchett. the bureaucracy: fantasy postal service of ankh-morpork. the bureaucrat: conman, scammer, and little freak moist von lipwig. this is definitely shorter and lighter than the other three entries on the list, sort of a screwball take on the bureaucrat. but the mail is such a classic bureaucracy thing? who doesn't love thinking about the mail? also contains a key genre element which is a fraught sexual tension with the person immediately above the protagonist in their hierarchy, who is also their god-king and boyfriend-dad. you can't tell me vetinari isn't torturing moist psychologically AND sexually.

anyway sorry about all this. if you've read any of these come talk to me about them. bureaucrat fiction recs welcomed with the openest possible arms.

#this post was very challenging to write bc i cannot spell the word bureaucracy to save my life. EVERY time i forget where the U goes#long post#asks#bureacracy. beaureaucracy. bereaucracy. fuck french

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm never sure how much of a Thing it's supposed to be, because of the novel framework, but...

it stands out to me that all of Grantaire's self-claimed republican knowledge is First Republic history:

I have read Prudhomme, I know the Social Contract, I know my constitution of the year Two by heart. `The liberty of one citizen ends where the liberty of another citizen begins.' Do you take me for a brute? I have an old bank-bill of the Republic in my drawer. The Rights of Man, the sovereignty of the people, sapristi! I am even a bit of a Hebertist. I can talk the most superb twaddle for six hours by the clock, watch in hand."

Like... this is all important history and even foundational philosophy! But in terms of convincing people right now ? No one's going to the barricades for Hebert. People aren't going to risk their lives and liberty because Robespierre was So Right.* People don't throw their current, actually-living selves into a dangerous situation because a bunch of people who died before they were born had some Good Points, even if they totally believe in the points. People risk their lives for Shit Going Down now.

Why is a republic urgent now, what are the main advantages people can --even abstractly!-- hope for from it? What are the current outrages? What's hurting them about the situation right now? Principles are important and crucial, of course, but there's a big gap between getting across the abstract concept and showing how that concept is relevant right now, to this audience . Even the most eager True Believer would be sensible to ask " why now " for something like they're planning-- why now and not autumn, or next year, or during the next labor protest, etc etc etc.

That's why Enjolras sends the others to the specific groups he sends them to! Because those are the groups whose immediate interests and concerns they can engage with best!

And that's exactly what Grantaire cannot do, even for himself. He can't argue for how immediate action will improve things because he doesn't think it will. He can agree the current situation Sucks; he can't believe anything anyone does will make it better. That's his whole entire failure point!

So of course he fails.

(...and , added knife-twist that I'm sure Grantaire notices: Enjolras sends everyone to the groups they can best influence....and he doesn't want to send Grantaire to anyone. And he is, of course, right on all fronts. I'm sure that leads to just the HEALTHIEST thought-loops.><)

...as volatile as FRev academic discussion gets sometimes, it's mostly not going to result in barricades and guns at dawn. Mostly.

#LM 4.1.6#Grantaire: Patron Saint of Fucking Up Just Like You Knew You Would#like in EXACTLY the way and form you knew you would#Unfortunately Relatable Characters#ugh typo now corrected but yk yk#if you see the uncorrected post no you didn't thanks

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

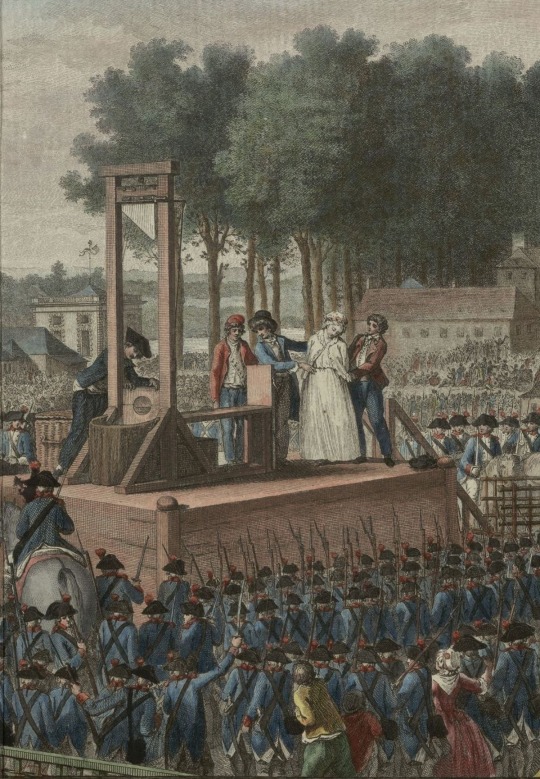

Almost done my novel research, I just need to get to the terror and the (justified) trial and execution of Marie Antoinette and Louis le incompetent <- I’m not saying his number he doesn’t deserve that.

Ah yes, the French revolution the most divisive event in history, my beloved.

Also... Robespierre was a saint compared to feudalism, monarchy and what Louis (and every French monarch before him) was doing to Haiti.

Marie Antoinette’s execution (from a French Revolution pamphlet).

Marie Antoinette on the way to her execution (Francois Fleming 1887).

#meera.musings#wip: liaisons x vampires#french revolution#writing historical fiction#writing horror#maximillian robespierre#marie antoinette#louis xvi#ancien regime#history#know your history#anti colonialism#anti imperialism#anti monarchy#les liaisons dangereuses#dangerous liaisons#18th century#18th century history#historical references

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sex, Violence and Power in Hilary Mantel’s A Place of Greater Safety

Ever since I finished this book I’ve been thinking about how gendered and sexual violence kind of continually lurk in its subtext and then break into the explicit text in periodic but still-shocking instances of abuse. At first I thought this was mostly unrelated to the central political plot — a matter of historical realism as much as anything — but the more I’ve thought about it the more integral and connected to everything else it seems.

CW: #rape, #abuse, #csa

From the first chapters of the novel, we see that women and girls in this time and place lack the ability to say no to sex with their husbands. As a child, Robespierre hears his maternal grandfather accuse his father of having murdered his mother via repeat pregnancies. Much later, Danton’s wife Gabrielle has a conversation with other women about the impossibility of using birth control in her marriage. Within a year Gabrielle is dead, her death eerily similar to that of Robespierre’s mother.

Manon Roland is molested as a child and carries a fear and revulsion of sexuality with her throughout her life as a result.

And Camille is taken advantage of as a young adult by an older man who controls the future of his career. The fact that Camille’s mentor is sexually predatory seems to be common knowledge throughout the professional community, and instead of intervening to protect Camille they humiliate and ostracize him. When Camille disavows responsibility for the relationship to his father (“None of it was my fault” and “I was just a child”) his father outright scoffs at the idea he might be trying to say he was raped. Much later Danton himself marries a young teenage girl and, again, no one seems willing or quite able to intervene. You get the overwhelming sense that this is a society where sexual abuse and exploitation are treated as mildly unpleasant facts of life about which nothing can or should be done.

Later, Camille narrowly escapes being coerced into sex by Babette, the young daughter of Robespierre’s landlord. Camille’s lingering terror of her after this incident is horribly psychologically realistic, but also…. Babette, teen girl predator of adult men, is the one instance of sexual violence in the book that has never sat entirely right with me.

The real Elisabeth Duplay wrote in her memoirs that Georges Danton tried to kiss her and made inappropriate sexual comments to her when she was a teenager. I see no reason to believe this isn’t true, and in light of it I do think representing Elisabeth as a sexual predator herself is kind of a strange and tasteless choice. It feels like an outlier in Mantel’s otherwise very grounded and realistic portrait of an 18th century rape culture.

The choice to represent a single individual person who lived and died hundreds of years ago as a rapist when she probably wasn’t one itself might leave a slightly bad taste in my mouth, but on the other hand historical fiction as a genre does tend to necessitate casting some dead people in unflattering lights just to create conflict and make the plot run. This alone doesn’t bother me nearly as much as Babette’s later “false rape accusation” against Danton (which is obviously how we’re meant to interpret it in the book, as a lie devised for political expediency) and that accusation being framed as a deciding factor in Robespierre’s decision to condemn Danton to death.

For one thing, this plot beat feels out of step with the development of Robespierre and Danton’s uneasy alliance and rivalry throughout the rest of the novel. From the beginning of the revolution the two of them have a grudging respect for each other but don’t like each other, they don’t share one another’s fundamental values or worldview and those differences increasingly drive a wedge between them as the external pressure on both men mounts. Robespierre becomes more ruthless and paranoid while Danton becomes more violent, exploitative and corrupt. Danton is a sexual abuser by this point in the story. He has married a teenage girl and it’s implied that he’s raping her (by the very implication that she is a child he is having sex with, and by a line in her internal monologue where she hopes he’ll get drunk and fall asleep right away so she won’t have to have sex with him). Meanwhile Robespierre is growing more committed to a belief system wherein “the people” of France are inherently morally pure and if they behave badly it’s because of external bad influences, wherein immorality is a societal cancer that needs to be cut out by chopping off the heads of every Evil Person.

At the end of those two character arcs I would have believed Robespierre was willing to have Danton killed without any false accusation scene, without any out-and-out lies being told to him about Danton. It feels like Mantel didn’t have enough faith in her own story and her own central character arcs and did this weird punch-pulling maneuver at the last minute that weakens the story. Two complex and well-developed characters becoming more entrenched in and committed to their own worst qualities over time until they destroy one another is a strong arc with a strong conclusion. One character being “tricked” into betraying the other by a one-dimensionally villainous minor character is weak and unsatisfying.

Babette and her purely malicious opportunism also makes it feel like… the call is coming from outside the house, so to speak. Like, as Robespierre believes, there are individual Bad People who are the problem and if they could be gotten rid of all societal ills would disappear. But throughout the rest of the story we see that really isn’t the case. Perrin hires Camille out of a desire to take sexual advantage of him, but also treats Camille well enough that years later Camille is willing to risk his own position to save Perrin’s life during the September Massacres. Danton is a loyal friend, a charming and charismatic leader, and someone who likes to compromise and negotiate rather than make enemies. And he’s also an abuser, a sexual predator, and a murderer (especially if you accept Danton’s own judgment that he killed Gabrielle “by unkindness”). When Manon runs into her own rapist years later she observes that he is “a perfectly ordinary young man”.

This is a more compelling and a more true portrait of a culture where exploitation and coercion are baked into the “normal” social structure.

Mirabeau has this internal monologue near the beginning that feels to me like the closest thing APoGS has to a thesis statement:

When you get down to it, he thought, there’s not much difference between politics and sex; it’s all about power. He didn’t suppose he was the first person in the world to make this observation. It’s a question of seduction, and how fast and cheap you can effect it.

So like, we’re all here in politics trying to accrue power. (Even if we hope to use that power for good.) We’re trying to exert as much control as we can over as many people as possible. We’re trying to coerce and manipulate and bribe each other. The methods of the outside world are not alien to the revolution; they are inside it from its genesis and present within it at every step of the way. And much, much later the revolutionary government will collapse into chaos not because of the foreign plots against it that Robespierre imagines but because of internal factional power struggles turning desperate and bloody and murderous.

From Robespierre’s first introduction to the story, we are shown that he has an intertwined horror of sexuality and abuses of power. He understands that his mother’s death was a result of abusive or “excessive” sexual behavior on the part of his father. He understands that as an illegitimately conceived child he would not exist if not for his parents’ immoral sexual excess. He spends the rest of his life trying to distance himself from that legacy and to prove he’s nothing like his father.

Asking himself why he’s so afraid of foreign political conspiracies, Robespierre directly draws the link to his own bodily alienation:

Why, he asked (since he is a reasonable man), does he fear conspiracy where no one else does?

And answered, well, I fear what I have past cause to fear. And these are the conspirators within: the heart that flutters, the head that aches, the gut that won’t digest, and eyes that, increasingly, cannot bear bright sunlight. Behind them is the master conspirator, the occult part of the mind.

Robespierre becomes obsessed with the idea that anyone whose policies he disapproves is a malicious foreign agent, bent on the destruction of the republic. This idea particularly takes root when people whose political views he otherwise shares advocate starting a war. Robespierre cannot accept the possibility that warmongering is an honest miscalculation — that people brought up surrounded by propaganda about glorious military triumphs might sincerely believe war could be a good thing for the republic.

He can’t accept that the violence he abhors is in his allies, that it’s in The People, that it’s in him. He can’t accept that Camille is sullied by sexual deviance, or that Danton could be both a powerful force for political stability and a corrupt, largely amoral bully. Robespierre can’t cope with the murky ambiguity and ambivalence that lurks in the “occult part of the mind”; he can’t bear to think of himself or anyone else he loves as a body capable of sex and violence. So he destroys Camille and destroys Danton and we know that he’ll be killed himself a few months later. I imagine him finally keeling over after slowly and gradually bleeding out from a self-inflicted wound, a self-surgery, a botched organ removal. He tries to excise the impurities from his own life and finds he can’t survive without them. He cannot bring himself to negotiate or make peace with the “conspirator within” and instead destroys himself completely.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

They’re here at last!!!

I love all of Les Amis, but their introductory paragraphs have also been pretty thoroughly analyzed - @everyonewasabird and @fremedon have pretty comprehensive posts on them from previous Brickclubs. Rather than go through them individually, then, I’ll try to point out some general trends that would be relevant to Marius (given that we meet them as soon as he’s kicked out of his house, we can assume there’s a connection):

The first major issue is the legacy of the French Revolution (1789) and the Terror (1793). All of the characters we meet here (with the exception of Grantaire) are attached to the legacy of the former, but they’re divided over the latter. Enjolras, for instance, is compared to Saint-Just – a more radical figure from that time period – and with his “warlike nature” and link to the “revolutionary apocalypse,” he’s definitely more in the tradition of ‘93 than ‘89, even if he’s attached to both. Combeferre, on the other hand, fears that kind of violence, only finding it acceptable if the only alternative is for things to stay the same. Like Marius’ newfound Bonapartism, all of their ideas come out of the clash and evolution of thought after the Revolution and the French Empire under Napoleon, placing each Ami in a similar position to him as they work out their ideas. All of them, though, came to a different conclusion than Marius, prioritizing the Republic over the Empire. At the same time, they’re all distinct from each other, too, revealing the diversity in French republican thought. With his limited exposure to political ideas outside of royalism (and now, idolization of Napoleon), the myriad veins of republicanism that the Amis offer broaden up the political sphere of the novel significantly.

On top of that, they’re a group; they can learn from each other in a way that Marius hasn’t had a chance to. Even Grantaire, who claims to not believe in anything, has friends, and while he distances himself from specific ideologies, his jokes illustrate that he’s familiar with them (for example: “He sneered at all devotion in all parties, the father as well as the brother, Robespierre junior as well as Loizerolles”). Marius doesn’t have friends or people to really work through ideas with. Oddly enough, the most similar structure to this that we’ve seen so far is the royalist salon. The key difference (aside from the obvious) is the chance to learn from different perspectives, whether that’s based on variations in republicanism, in priorities (conflict vs education, the local vs the international), or both. They’re not even all defined by their politics. Courfeyrac (who easily has the most insulting character introduction in the book) is defined by his character and personality first, with his political ideas mainly being a given from his participation in this group. These variations in emphasis, then, not only show us the diversity of their views, but the varying intensities with which they hold them (as in, you could talk to Courfeyrac about something that isn’t political, but you couldn’t do that with Enjolras) and how they’re kept together in spite of their disagreements (a common goal – a Republic – and many fun and socially savvy members). All of these factors serve to give a sense of liveliness as well, contrasting sharply with the “phantoms” of the royalist salon.

Les Amis aren’t very diverse class-wise, but they’re still better than the salon. Bahorel and Feuilly, at least, aren’t bourgeois or aristocrats.

Feuilly also brings us to the international level, far beyond Marius’ early attempts at imagining himself as part of a country. Focusing on the partition of Poland in particular, Feuilly advocates for national self-determination in all lands under imperial rule. The idea that a people should govern themselves was key to republican thought more broadly in that time (nationalism really took shape in the 18th-19th centuries), but to Feuilly, this isn’t just an issue of nationalism, but of tyranny:

“There has not been a despot, nor a traitor for nearly a century back, who has not signed, approved, counter-signed, and copied, ne variatur, the partition of Poland.”

The word “despot” ties this back to France in a way, with his rejection of despotism as it affects Poland possibly implying a similar anger at the same phenomenon in France. The Bourbons at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 were, after all, the same Bourbons who ruled during the Restoration.

A quick note on Lesgle: I didn’t get the joke around “Bossuet” the first time I read this book. Then, I had to take a class on the French monarchy, and I was assigned a text by Bossuet of Meaux, court preacher to Louis XIV and fierce proponent of absolutism. His name seemed familiar, but it took me a while to think to check Les Mis? And now I think calling Lesgle Bossuet because he’s Lesgle (like l’aigle=eagle) of Meaux is one of the funniest jokes in this book.

#Les mis letters#lm 3.4.1#les amis de l'abc#enjolras#combeferre#courfeyrac#feuilly#grantaire#Bahorel#Lesgle#bossuet#this ended up being much less organized than I’d hoped#But that’s OK because they’re here and now we can all talk about them!!

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having a meeting with my creative writing professor today to give him the first chapter of my book to look over for advice... I know I've been saying this for forever, but hopefully publishing stuff starts soon(ish)...?

#frev#french revolution#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#robespierre novel#frev wip#novel update#first novel

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

i am not ok with several media depictions of their relationship (cough cough, mantel's novel, cough), so i came up with a meme template for them (in my head-canon) and for many others.

i really prefer to see them as queer-platonic... imo most of robespierre's friends were queer-platonic with him. i could be wrong though, i'm likely mostly a confused alloro.

empty meme template beneath the cut if any of you are interested.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

i love searching spanish books about Robespierre because i always find something cursed

like this book! looks like a biography and the cover is super pretty (i just like the delpech engraving)

WELL ITS NOT!!!

ITS A FICTIONAL NOVEL!!!! Here's the summary (google translated bc i can't bother with it rn)

One day in early autumn in 1793, the young Sebastien-François Précy de Landrieux arrived in Paris for the first time. He had not yet turned sixteen. But the city that welcomes him is not the one he dreamed of so many times. From the windows of his carriage he contemplates, in the plaza through which he crosses, the Artifact with its blade suspended on top, the famous and feared scales of justice of the Revolution. And he feels a light breeze on his neck. Sebastien still does not know that, through a contact of his father, he will start working in the office of Deputy-Minister Lindet, which will allow him to deal with senior officials, including Robespierre himself. Without realizing it, Sebastien finds himself in the administrative heart of the Terror. At death's door, Sebastien writes his memoirs of those days. And so the events and emotions that from September 1793 to August 1794 marked not only the French Revolution but also the birth of modernity unfold before the reader's eyes. The result is a historical novel, with intrigues and epic moments, and a novel of ideas at the same time. Along with an extensive presentation of historical figures, magnificent, difficult to surpass, and possibly never done before in Spanish, we witness a stark denunciation of the lie on which the essential values of our civilization were built, which while boasting having achieved the freedom of its citizens, it will hardly be able to do the same with respect to equality. A magnum opus in the author's career, Robespierre is, both ethically and aesthetically, an oceanic proposal -as were the Revolution and especially the Terror-, after which the shipwrecked readers will find what they were looking for.

T-there's a preview available... should i check and see how bad it is?💀

Why did the author choose to just call it "Robespierre"? to lure and disappoint me, personally i guess

#frev#i skimmed through the preview and it starts with a charlotte corday quote so you know it will be great 💀#no but i genuinely love this cover the colors are so nice and the wig looks so soft

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

I found a novel about young Napoleon's rise to power, and in the first few pages it's told me Robespierre had no lips and that he was losing sleep over the rumours about him and Eleonore Duplay being lovers, because she was so fucking ugly, he would never, how could people say that, how mean of them

#well thanks for nothing author#patrick rambaud: le chat botté#justice for them both#but mostly justice for Eleonore#I'm sure he found her lovely and gave her many platonic (or not) kisses with the lips he definitely had

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know Hugo's love for details gets made fun of a lot but I think it's honestly endearing. The sewer exploration was really interesting, I can't say Myriel's background left a mark in me but it was so pleasant to read. Loved the descriptions of Paris, the description of the light related to what was happening in the city. In fact often I've been left wanting more details when I read Les Miserablès (and Hugo in general). Why did Grantaire have that Robespierre waistcoat? How bad was his relationship with his father? How was he ugly? How was Enjolras' relationship with his (human) mother? How much did Cosette remember of Eponine? Would she be resentful? Favourite and Fantine. The whole story of Le Cabuc that sounds interesting as fuck? How did Les Amis react to 1830 victory (actually I think skipping the 1830 revolution brought some issues to the 1832 uprising plot)? How did they react when their victory was stolen? The background of Valjean and his sister? What was the impact of the ethnicity of Javert's mother on Javert? Etc etc

It's also... "relaxing", I don't know... in Les Mis as well in other novels of his, when I met a character I get to know their personality, at least a brief backstory usually, the context of their behaviour. If something happens I know how it happened usually. I don't have to keep asking myself wtf is happening, I don't have the risk to miss crucial event or motivations. And I can see literally the events unfold behind my eyes, either because the author is precise with his material descriptions or because he gets to portrait the "vibes" with vividness.

#les miserables#the brick#victor hugo#I fucking love details#when I walk the streets I fixate on random architecture lmao

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sexy clinch 1790s French edition

#napoleon bonaparte#josephine beauharnais#charlotte robespierre#fouche#joseph fouché#herault#hérault de sechelles#suzanne de la morency#caroline bonaparte#joachim murat#murat#joseph fievée#theodore leclercq#louis-antoine saint-just#thérèse gellé#theresia cabarrus#jean-lambert tallien#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#mademoiselle raucourt#sophie arnould#clinch#romance art#frev#french revolution#napoleonic era#let the games begin

58 notes

·

View notes