Text

Mathematician, physician and philosopher (1776-1831), Sophie Germain was a genius who fought hard to be heard a recognized.

A self-taught prodigy

The daughter of a silk merchant, Sophie was born in Paris to a relatively wealthy family. When the French Revolution broke out in 1789, her father became a member of the Constituent Assembly. Amidst the chaos, Sophie found solace in her father's library and discovered mathematics.

Fascinated by the subject, she learned everything she could, studying at night. Her parents disapproved. Mathematics was thought to be too complex for women who had to focus first and foremost on their home.

Sophie's parents tried to stop her by putting out the fire in her room at night and confiscating her clothes and candles after nightfall. Sophie's thirst for knowledge was stronger. According to her obituary, she studied “at night in a room so cold that the ink often froze in its well, working enveloped with covers by the light of a lamp”. She even taught herself Latin to read the essential works.

Sophie impresses

The École Polytechnique was founded in 1974 with to train a new elite of engineers, mathematicians and scientists. Being a woman, Sophie couldn’t attend. She learned that a student named Leblanc wasn’t able to go to class. She wrote to the school, pretending to be him, and managed to obtain lecture notes. She was also able to complete and submit assignments.

This promising student impressed mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange who found her answers brilliant. The self-taught Sophie had gained the admiration of one of the most renowned mathematicians of her time.

Lagrange's desire to meet her forced Sophie to reveal her real identity. Lagrange was at first surprised to learn that his correspondent was a woman. He nonetheless became Sophie’s mentor, introducing her to a new world and opportunities.

Sophie made major contributions to number theory. She worked on Fermat's last theorem, making major observations and creating her own theorem. This would be one of her major contributions to mathematics.

In 1804, she began a correspondence with another mathematician, Carl Friedrich Gauss, whose work she admired. He was similarly impressed by her intelligence:

“But how to describe to you my admiration and astonishment at seeing my esteemed correspondent Monsieur Leblanc metamorphose himself into this illustrious personage who gives such a brilliant example of what I would find it difficult to believe. A taste for the abstract sciences in general and above all the mysteries of numbers is excessively rare: one is not astonished at it: the enchanting charms of this sublime science reveal only to those who have the courage to go deeply into it. But when a person of the sex which, according to our customs and prejudices, must encounter infinitely more difficulties than men to familiarize herself with these thorny researches, succeeds nevertheless in surmounting these obstacles and penetrating the most obscure parts of them, then without doubt she must have the noblest courage, quite extraordinary talents and superior genius.”

An incomplete recognition

Sophie was also interested in physics. In 1811, she entered a contest held by the French Academy of Sciences, but her lack of formal education turned against her. She didn't give up and won the contest in 1816 with her Memoir on the vibrations of Elastic Plates. She kept working on the theory of elasticity and published several more memoirs. Her work would prove pivotal in the field.

This prize also meant official recognition for Sophie. In 1823, she became the first woman to be allowed at the Academy of Sciences' sessions. Though respected as an equal collaborator by some, she still felt like a “foreigner” in the scientific community.

Sophie Germain died at the age of 55, on June 27, 1831, after a battle with breast cancer. Carl Friedrich Gauss had convinced the university of the University of Gottingen to give her an honorary degree but Sophie was dead before she could receive it.

Her death certificate designated her as a "rentière-annuitant" (a single woman with no profession) instead of a mathematician.

Today, a street in Paris, schools in France and a crater on Venus are named in her honor. She appeared on a French postal stamp released in 2016.

Feel free to check out my Ko-Fi if you like what I do! Your support would be greatly appreciated.

Further reading

Alkalay-Houlihan Coleen, “Sophie Germain and special cases of Fermat’s last theorem”

Boyé Anne,, “Sophie Germain, une mathématicienne face aux préjugés de son temps”

“Biographies of women mathematicians : Sophie Germain”

Lamboley Gilbert, “Math’s hidden woman”

Koppe Martin, “Sophie Germain, une pionnière enfin reconnue”

#sophie germain#history#historyedit#women in history#19th century#france#french history#upthebaguette#herstory#mathematics#mathematicians#historical#historical figures#women in stem#european history#historyblr

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Therefore, the references to Thyra on both groups of stones likely refer to the same person – the Danish Queen and mother of Harald Bluetooth. This indicates that she was a particularly powerful and celebrated individual. It is likely that she held land and authority in her own right, not only through her husband. “No other Viking man or woman in Denmark has been mentioned on that many runestones,” says Dr Imer, “and it underlines her undeniable importance for the assembling of the realm under the rule of her son, Harald Bluetooth.”

Importantly, this means that women likely had more influence in Viking-Age Denmark than previously believed. It indicates that Viking women may have been able to hold power in their own right and rule on behalf of their husbands or under-age sons. It also has important implications for our knowledge on the formation of the Danish state. The authors conclude:

If we accept that runestones were granite manifestations of status, lineage and power, we may suggest that Thyra was indeed of royal, Jutlandic descent. Both Gorm and Harald refer to her in the runestone texts and Ravnunge-Tue describes her as his dróttning, that is, ‘lady’ or ‘queen’. Combined with the designation of Thyra as Danmarkaʀ bót, ‘Denmark’s strength/salvation’, these honours point towards a powerful woman who held status, land and authority in her own right. The combination of the present analyses and the geographical distribution of the runestones indicates that Thyra was one of the key figures—or even the key figure—for the assembling of the Danish realm, in which she herself may have played an active part.""

#thyra#history#women's history#queens#women in history#denmark#danish history#vikings#10th century#medieval women#middle ages#medieval history#runestones#harald bluetooth

48 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you heard of Fatma Seher Erden ? She is my idol

Yes, I've heard of her! (but there's not much information about her in languages other than Turkish apart from wikipedia).

Seems she also had other women under her command, which is interesting as well!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

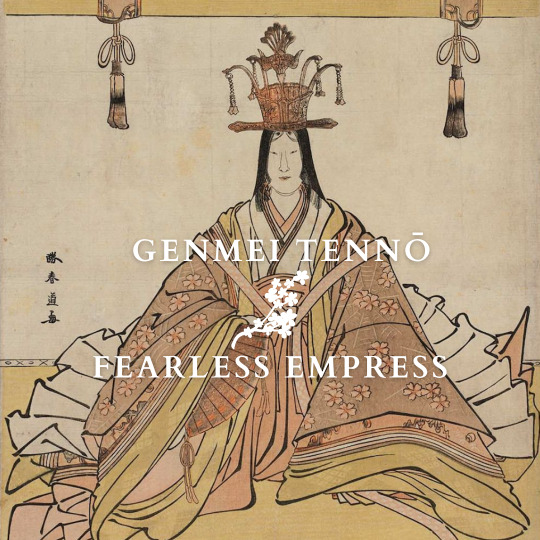

Genmei (661-721) was Japan's fourth empress regnant. She was Empress Jitō's half-sister and her match in terms of ambition and political skills. Her rule was characterized by a development of culture and innovations.

Ruling after her son

Like Jitō (645-703), Genmei was the daughter of Emperor Tenji but was born from a different mother. Jitō was both her half-sister and mother-in-law since Genmei had married the empress’ son, Prince Kusakabe (662-689). She had a son with him, Emperor Monmu (683-707).

Kusakabe died early and never reigned, which led to Jitō's enthronement. The empress was then succeeded by her grandson Monmu. The latter’s reign was short. In his last will, he called for his mother to succeed him in accordance with the “immutable law” of her father Tenji. Genmei accepted.

Steadfast and ambitious

Genmei was made from the same mold as her half-sister. She proved to be a fearless sovereign, undeterred by military crises.

She pursued Jitō's policies, strengthening the central administration and keeping the power in imperial hands. Among her decisions were the proscription of runaway peasants and the restriction of private ownership of mountain and field properties by the nobility and Buddhist temples.

Another of her achievements was transferring the capital at Heijō-kyō (Nara) in 710, turning it into an unprecedented cultural and political center. Her rule saw many innovations. Among them were the first attempt to replace the barter system with the Wadō copper coins, new techniques for making brocade twills and dyeing and the settlement of experimental dairy farmers.

A protector of culture

Genmei sponsored many cultural projects. The first was the Kojiki, written in 712 it told Japan’s history from mythological origins to the current rulers. In its preface, the editor Ō no Yasumaro praised the empress:

“Her Imperial Majesty…illumines the univers…Ruling in the Purple Pavillion, her virtue extends to the limit of the horses’ hoof-prints…It must be saif that her fame is greater than that of Emperor Yü and her virtue surpasses that of Emperor Tang (legendary emperors of China)”.

In 713, she ordered the local governments to collect local legends and oral traditions as well as information about the soil, weather, products and geological and zoological features. Those local gazetteers (Fudoki) were an invaluable source of Japan’s ancient tradition.

Several of Genmei’s poems are included in the Man'yōshū anthology, including a reply by one of the court ladies.

Listen to the sounds of the warriors' elbow-guards;

Our captain must be ranging the shields to drill the troops.

– Genmei Tennō

Reply:

Be not concerned, O my Sovereign;

Am I not here,

I, whom the ancestral gods endowed with life,

Next of kin to yourself

– Minabe-hime

From mother to daughter

Genmei abdicated in 715 and passed the throne to her daughter, empress Genshō (680-748) instead of her sickly grandson prince Obito. This was an unprecedented situation, making the Nara period the pinnacle of female monarchy in Japan.

Genmei would oversee state affairs until she died in 721. Before her death, she shaved her head and became a nun, becoming the first Japanese monarch to take Buddhist vows and establishing a long tradition.

Feel free to check out my Ko-Fi if you like what I do! Your support would be greatly appreciated.

Further reading

Shillony Ben-Ami, Enigma of the Emperors Sacred Subservience in Japanese History

Tsurumi Patricia E., “Japan’s early female emperors”

Aoki Michiko Y., "Jitō Tennō, the female sovereign",in: Mulhern Chieko Irie (ed.), Heroic with grace legendary women of Japan

#history#women in history#women's history#japan#japanese history#empress genmei#japanese empresses#historical figures#historyedit#herstory#nara#japanese art#japanese prints

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

The dangers of the combat zone

"Women accompanying the military were in what military historian John Lynn calls the combat zone, which is

best defined by the intensity and immediacy of danger and by the ability to do direct harm to the enemy… the full reality of war lives here. Modern armies regard it as an innovation to send some women into combat, but in the campaign community all women stood in harm’s way.

It would be odd to imagine that the women accompanying an army, exposed as they were to all the dangers of the military world, didn’t pick up arms and fight. In 1643, in the earlier stages of the English Civil War, a regiment of troops was recalled from Ireland to support King Charles. Rumours swirled that they were accompanied by a regiment of women, and that ‘these were weaponed too; and when these degenerate into cruelty, there are none more bloody’. Indeed, when 120 Irish women were taken prisoner at Nantwich they were discovered to have long knives with them, causing a furore in the press. The dubiously named True Informer excitedly reported that the knives in question were half a yard long, with a hook at the end ‘made not only to stab but to tear the flesh from the very bones’. The likeliest explanation for these knives, however, is that the women weren’t soldiers; they were camp followers, and they needed the knives to help them with pillage and self-defence.

The women of the campaign community did fight. The Bishop of Albi, on the battlefield of Leucate in southern France to administer to the dying in 1637, came upon the bodies of several women in uniform. ‘These were the real men,’ he was told by the Castilian soldiers, ‘since those who had fled, including certain officers, had conducted themselves like women’.

Madeleine Kintelberger was a vivandière accompanying the French Seventh Hussar Regiment at Austerlitz in 1805, along with her soldier husband and their six children. The regiment was under heavy attack from Russian forces when her husband was killed by a cannonball, and her children seriously wounded. Madeleine herself had taken a cannonball to the arm, virtually slicing it off below the shoulder. As the Russian Cossacks approached, she scooped up a sword to defend her children, receiving further wounds in both her arms before the family was taken prisoner. Madeleine was six months pregnant and gave birth in captivity. Her bravery was rewarded with a pension from Napoleon. Examples of cantinières fighting are ‘legion’."

Forgotten Warriors, Sarah Percy

#history#women in history#women's history#19th century#17th century#women warriors#warrior women#madeleine kintelberg#european history#historical figures#historical#france#franch history#england#english civil war#napoleoni

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

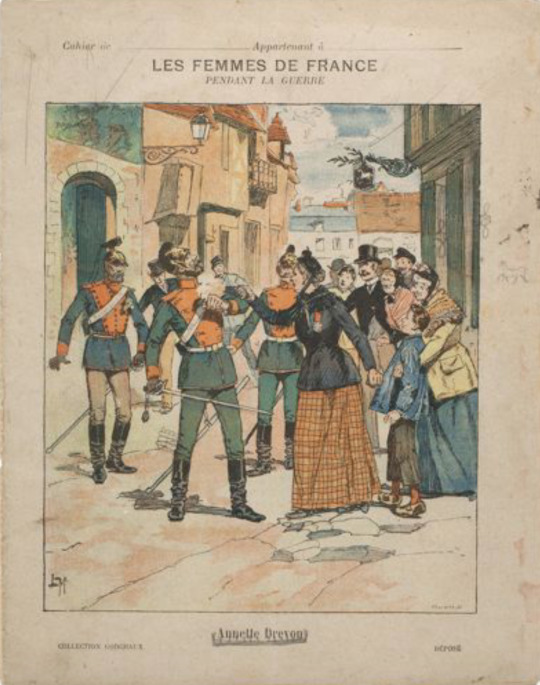

Annette Drevon: cantinière, soldier

"In 1880, visitors to the markets of Les Halles in Paris might have noticed an especially striking woman sitting at her vegetable stall. In her mid-fifties, with black hair and unwrinkled skin, she had an expression of ‘courage and energy’, which was perhaps unsurprising, given her past. Annette Drevon was a cantinière in the French army, a woman officially deputised to sell food and drink to the soldiers. At the Battle of Magenta in 1859, Annette was attached to the second regiment of Zouaves. During the battle two Austrian soldiers seized the regimental flag. Annette got it back: she killed the first soldier with a sabre and the second with two shots from her revolver. The regiment’s colonel pinned his own Cross of the Legion of Honour to her chest in honour of her actions.

Annette was still serving during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, where she shot another soldier, this time a German who either insulted her or attempted to steal her Cross; she was sentenced to death but pardoned by Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse, and returned to France. She later received a small pension from Marshal MacMahon, who had commanded the who had commanded the French troops at Magenta, which she used to set up her vegetable stall.

Annette Drevon’s story is a useful reminder that for well over 400 years the normal battlefield was full of ordinary women, who were not only essential to the conduct of war but also demonstrated bravery, physical strength and the ability to stand up to tough conditions – all the things military leaders of the late twentieth century fretted that women could not do."

Forgotten warriors: The long history of women in combat, Sarah Percy

#annette drevon#history#women in history#women's history#france#french history#warrior women#women warriors#historical#historical figure#herstory#19th century#second french empire

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

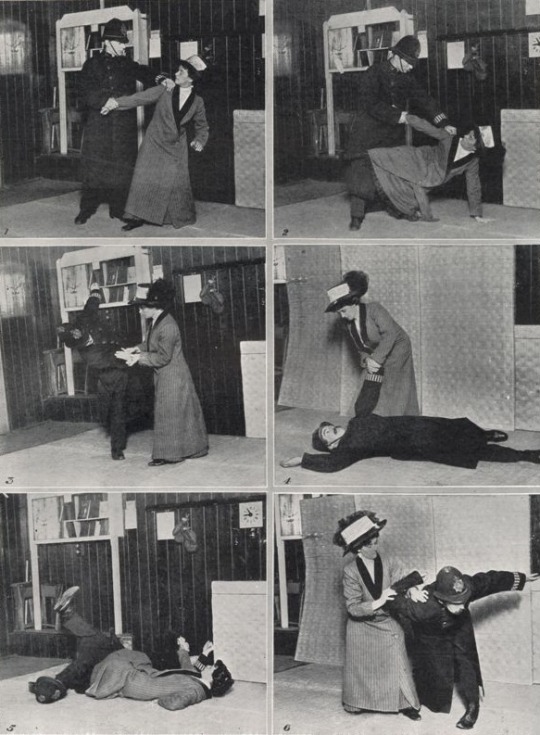

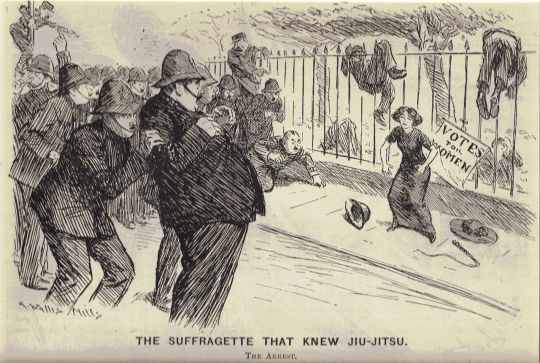

Edith Garrud - The suffragette that knew martial arts

The first British female teacher of jujutsu, Edith Garrud (1872-1971) taught the suffragettes to protect themselves.

A passion for martial arts

Edith Margaret Williams was born in Bath in 1872 and started her career as a physical instructor for girls. She shared this passion for physical culture with her husband, William Garrud, a wrestling and boxing instructor.

They came in contact with Edward Barton-Wright who had spent three years in Japan, and studied judo and jujutsu. He elaborated his self-defense techniques known as “bartitsu” and opened his club in London in 1899.

The Bartitsu Club was notably opened to women. Edith was thus able to train alongside her husband. By 1908, Edith and William became jujutsu instructors themselves with William in charge of the men’s class and Edith teaching the women and children.

Jujutsu specializes in speed, precision and the use of soft, flowing movements to deal with aggression rather than using just brute strength. The couple showcased their skills through demonstrations. In one of them, Edith defeated a male aggressor played by her husband. The sight of this 4ft-11inch (150cm) woman effortlessly throwing a much taller man greatly impressed the audience.

In 1907, Edith starred in a short film Jujutsu down the footpads in which an innocent lady overpowers two ruffians.

Vote for women

Edith took an interest in the cause of women’s suffrage. In 1909, she was invited by the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) to give a demonstration in the presence of Emeline Pankhurst and other leading figures of the movement. As William was ill, Edith demonstrated alone and invited members of the audience to test her skills. This included subjecting a skeptical police officer to a powerful shoulder throw.

In 1910, Edith also wrote a series of essays, advocating for the growing community of female martial artists and how self-defense could free women by giving them the means to protect themselves:

“You constantly read in the papers reports of dastardly attacks on helpless women by thieves and ruffians. A woman who knows jujutsu, even though she may not be physically strong, even though she may not have even an umbrella or parasol, is not helpless. I know many women personally who have tried the tricks I shall explain to you and come out on top. They have brought great burly cowards nearly twice their size to their feet and made them howl for mercy.”

The bodyguards

The suffragettes faced dangerous and violent situations. This was especially the case on Friday 18th November 1910. 300 WSPU members marched on the House of Parliament and faced police officers armed with batons. Women were subjected to six hours of beatings and arrests and there were widespread reports of sexual abuses.

Emeline Pankhurst thus asked Edith to train a group of women that would be known within the WSPU as the Bodyguard. Led by Gertrude Harding, they acted as agitators, disruptors and decoys.

Edith trained them in hand-to-hand combat and the use of homemade concealed weapons such as wooden India clubs and the fashioning of cardboard body armor. The suffragettes took advantage of their opponent's surprise and exploited their weaknesses.

They for instance struck directly at a police officer’s helmet to knock it from his head. Policemen were held accountable for the loss of uniform items and had to pay for their replacement. They cut the suspenders so that the policeman had to hold back his pants, blinded the police with a charge of umbrellas etc.

When told by a policeman that she was making an “obstruction” during a demonstration near the House of Commons, Edith pretended to drop her handkerchief, threw the policeman over her shoulder and disappeared into the crowd.

In prison, suffragettes went on hunger strikes and were subjected to force-feeding. The “Cat and Mouse Act” of 1913 allowed hunger-striking prisoners to be released and then re-incarcerated as soon as they had recovered their health. The Bodyguard thus protected and hid those women.

Edith for instance hid militant suffragettes in her dojo, telling the police not to disturb her lessons and leave her property.

A quiet retirement

Edith’s contributions to the suffragist movement ended with the beginning of the First World War. Little is known of her life afterward.��

She and her husband would run the Golden Square dojo until their retirement in 1925 and retired to a quieter life. William passed away in 1960. In an interview in 1965, Edith said that her recipe for a long, happy and healthy life was:

“Self-discipline. Of course, I had to be extremely disciplined to succeed at jujutsu and hold my own with men […] but it is the mind which really has control, not only of your muscles and your limbs and how you use them, but also your thoughts, your whole attitude to life and other people.”

She died in 1971. A plaque on the building that had been her home can be seen today: “Edith Garrud 1872–1971. The suffragette who knew jiu-jitsu lived here”.

Further reading

Dorlin Elsa, Se défendre : une philosophie de la violence

Godfrey Emelyne, Femininity, Crime and Self-Defence in Victorian Literature and Society: From Dagger-Fans to Suffragettes

Kelly Simon, "Edith Garrud: The jujutsuffragette". In McMurray, Robert; Pullen, Allison (eds.), Power, Politics and Exclusion in Organization and Management

Ruz Camila, Parkinson Justin, ““'Suffrajitsu': How the suffragettes fought back using martial arts”

#history#women in history#women's history#feminism#suffragettes#20th century#edith garrud#martial arts#jujutsu#jiujitsu#england#english history#herstory#women in martial arts#historical figures

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

"At just 30 years old, Agnesi made her crowning mathematical achievement: the publication Instituzioni analitiche ad uso della gioventù italiana (Analytical Institutions for the Use of the Italian Youth), a calculus textbook published in 1748. This hefty two-volume work is a treatment of differential and integral calculus. The first volume is a treatment of the algebraic framework needed to understand the calculus in the second volume. The first Italian youth she was hoping to reach may have been her younger siblings: Pietro had 21 children by his three wives, though few of them survived to adulthood.

In addition, the book was written in Italian, at a time when Latin was still the default language for scholarship. Agnesi wrote it in the common tongue because she wanted the book to be accessible to less educated students. Despite this—and the fact that it was written by a woman—it gained the respect of mathematicians around Europe as an unusually clear treatment of the subject. Decades after it was published, the mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange recommended its second volume as the best place to go for a thorough treatment of calculus.

Analytical Institutions has since been translated into English and French. In the preface to the 1801 English version, the editor writes that the volumes “are well known and justly valued on the Continent” and that the primary translator of the work, the late Reverend John Colson, Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, “was at the pains of learning the Italian Language, at an advanced age, for the sole purpose of translating that work into English; that the British Youth might have the benefit of it as well as the Youth of Italy.""

#maria agnesi#18th century#history#women in history#women's history#italy#italian history#mathematics#women in science#women in stem#historical figures#herstory

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mongol women at work

"No records account for women specifically working on the postal roads as couriers, although Mongol women often had physically demanding jobs. Alongside elite women sometimes participating in hunting and warfare, women at all levels of society would herd animals and were in charge of packing up wagons to move camp.

Additionally, Yuan governmental policy assigned specific jobs required for the smooth running of the empire to households (for example, post-road couriers), which meant that if a man was not available to do a job (due to absence or death), women would be obliged to step into the role assigned to her family.

In the record Heida Shilüe 黑韃事畧 (A Sketch of the Black Tatars), the Song dynasty envoy Peng Daya’s 彭大雅 observations from a visit to the Mongol territories in 1233, expanded upon by Xu Ting’s 徐霆 (another Song envoy) record from 1235–1236, both men note that Mongol women did many tasks on horseback. Peng writes, “In horsemanship and archery, babies are tied with cords onto plats which then are fastened onto horses’ backs, so they can go about with their mothers”. Xu Ting elaborates on Peng’s observations with this anecdote:

I saw an old Tatar lady, when she had finished giving birth to a baby in the wilderness. She used sheep’s wool to wipe off the child, then used a sheepskin for swaddling clothes. Binding the baby up in a little cart, four or five feet long and one foot wide, the old lady thereupon tucked the cart crosswise under her arm and straightaway rode off on horseback.

This is a strange story—why would Xu Ting have been in a position to witness a woman giving birth? As his account of the Mongols highlights, the Mongol population that Xu Ting interacted with were post-road couriers during his travels within the empire and personnel at the Mongol court, and it is unlikely that he witnessed a woman giving birth and immediately riding off on her horse to take up courtly duties, so it is plausible that this was a woman he saw who was working along the postal road, filling in for an absent male relative. Therefore, while no specific accounts of women postal couriers exist, in reading between the lines of Xu Ting’s narrative, the possibility of women postal workers in the Yuan becomes more likely."

Riders in the Tomb: Women Equestrians in North Chinese Funerary Art (10th–14th Centuries), Eiren L. Shea

#history#women in history#women's history#mongol women#working women#13th century#mongolia#yuan dynasty#mongol history#historyblr#china#asia#asian history

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

During the second or first century BCE, a woman pretended to be able to control the moon. This was Aglaonice, who is regarded by some as the first known female astronomer.

She’s mentioned in the writings of Plutarch and the scholia to Apollonius of Rhodes and lived in Thessaly, Greece. Being “skilled in astronomy”, Aglaonice used her knowledge to predict eclipses and make people believe she caused the moon to disappear.

According to Plutarch:

“Thoroughly acquainted with the periods of the full moon and when it is subject to eclipse, and, knowing beforehand the time when the moon was due to be overtaken by the earth’s shadow, imposed upon the women, and made all believe she was drawing the moon down.”

The scholia adds that Aglaonice lost a close relation as a punishment for having angered the moon goddess.

Interestingly, Thessaly is associated with women skilled in astronomy and occult practices. Several female astrologers from the third to first centuries BCE were for instance known as “The Witches of Thessaly”. These women were said to study the movements of the moon and trick people into believing that they caused lunar eclipses.

In Plato's Gorgias, Socrates mentions the "Thessalian enchantresses who, as they say, bring down the moon from heaven at the risk of their own destruction."

Today, a crater on Venus bears Aglaonice’s name.

Feel free to check out my Ko-Fi if you like what I do! Your support would be greatly appreciated.

Further reading:

Bicknell Peter, "The witch Aglaonice and dark lunar eclipses in the second and first centuries BC."

Chrystal Paul, Women in Ancient Greece

Plutarch, On the failure of oracles

Plutarch, Conjugalia Praecepta

Reser Anna, McNeil Leila, Forces of Nature: the women who changed science

#aglaonice#history#women in history#women's history#women in science#herstory#greece#ancient greece#antiquity#scientists#astronomy#historyedits#1st century BCE#ancient world#historical figures

97 notes

·

View notes

Link

“From the Onin War’s start in 1467, the Japanese islands were almost continuously at war for a full century. Kita came from two high-ranking samurai families in northern Japan, the Oniniwa and Katakura, who served local lord Date Terumune. At the time, the Date clan was but one among many in the region, with far more powerful, blue-blooded, influential and potentially dangerous ruling clans for neighbors. Like many warrior-caste daughters during this era of civil upheaval, Kita knew how to fight. What set her apart was a pronounced interest in and aptitude for the martial arts and military science. She was so skilled that she took it upon herself to act as a teacher to her half-brother Kagetsuna, who was heir to the Katakura headship.

The Date clan was slowly putting itself back together after infighting nearly destroyed it when, in 1567, a new heir, Bontenmaru, was born. Terumune ordered, Kita, then 29, to serve as wet nurse to the newborn. His birth mother, Yoshi, showed little interest in being maternal, and at certain times even tried to have him murdered to advance her own family’s political interests. Kita, by contrast, was especially close to Bontenmaru. Over the years, she nourished not only his body but also became one of his earliest teachers in both the literary and martial arts, helping shape him into a leader whose reputation in battle and politics earned him the moniker of One-Eyed Dragon.

With strong opinions and powerful support from men of privilege and influence, Kita advocated for the young heir’s succession to Date headship. And in 1584, despite Yoshi’s best attempts to prevent it, she got her wish. Bontenmaru transcended both battlefield injury and illness — including a small-pox outbreak that claimed his right eye — to become Date Masamune, the clever, stylish, internationalist warlord who took the Date clan from obscurity to fame as the fourth wealthiest family in Japan.”

#japan#history#women in history#women's history#samurai#japanese history#15th century#sengoku period#date masamune#warrior women#women warriors#historical figures#herstory#sengoku#samurai women#female samurai

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

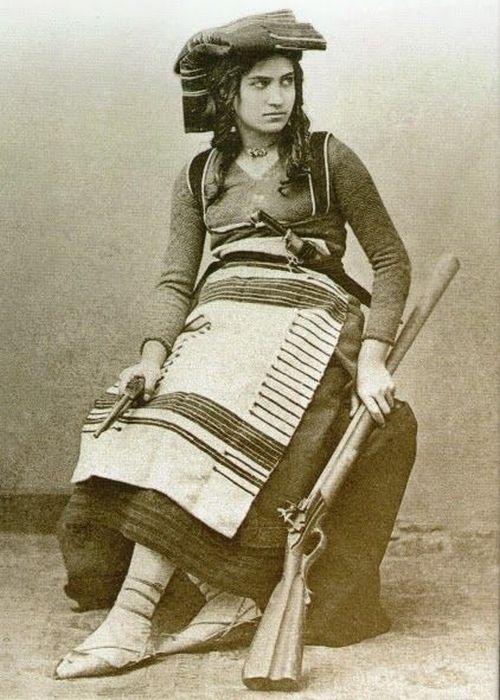

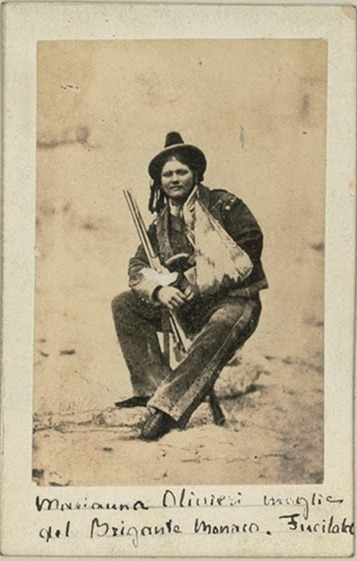

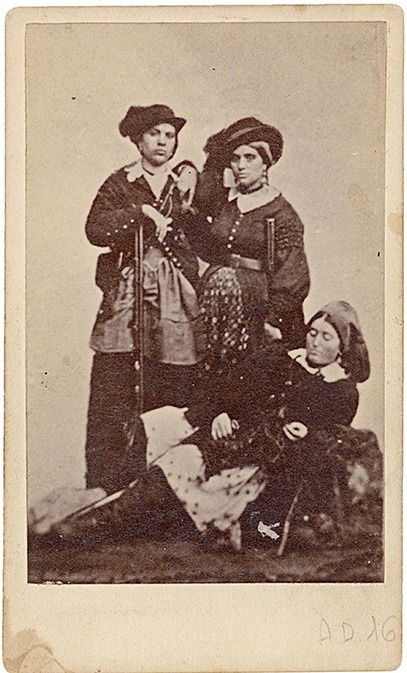

Brigantesse

These are some of the most famous female brigands of Italy. By coincidence, they were all born on the same year, and their criminal activities took place during and after the complete mayhem that was the Unification of Italy.

The first four photos are of Michelina Di Cesare (1841–1868), the next three are of Maria Oliverio (1841–1879), and the last two of Filomena Pennacchio (1841–1915), on the left, along with her two friends and accomplices Giuseppina Vitale and Maria Giovanna Tito.

In Italy, like in Spain, female bandits were uncommon but not unheard of, especially in such tumultuous times. These three women had very different reasons to become outlaws: Michelina was basically driven by poverty, Maria hacked her own sister to pieces with an axe because she “slandered” her (it’s pretty fucked up if you ask me, but that’s Honour™ for ya: talk shit, get brutally murdered), and Filomena got tired of getting beaten by her husband and stabbed him to death with a pin. So rather than stick around and get caught (or starve), they all chose a brigand’s life.

There’s a lot of complicated context here re: the political situation, but post-Unification brigandage in Italy is a whole field of history in itself, so I won’t get into it. Let’s just say that all three of them operated (more or less) against the new regime, being vaguely pro-Bourbon, and leave it at that. Though I should note that, much like Royalist highwaymen during the English Civil War or pretty much anyone during the Mexican Revolution, people often became robbers first and found a political justification later, especially if there was a faction willing to offer them support in exchange for doing some dirty work or another.

Behind the camera / posing for the camera

But I want to talk about the photographs themselves. These aren’t candid shots, they are photo-shoots, and I am endlessly fascinated by bandit portraits. It’s a whole genre, these portraits, there were tons of them taken in the late 19th and early 20th century, from South America to the Mediterranean and from Eastern Europe to China, wherever bandits thrived and photographers were around. (And I suppose with North American gunslingers too, but y'all already know about those, right?) The bandits stand in front of the camera and pose, rarely with a frown, often with a smile, always with a gun and just brimming with pride.

And I always wonder, what’s the story behind the picture? How did the photographer meet the bandit in the first place, and how did he feel directing a dangerous outlaw? (”Stand over there, head a bit to the right, hold the rifle higher, now hold still please.”) Was he scared? Excited? How did they come to an agreement? Who had to convince whom? And for that matter, who directed whom? Portraits are traditionally credited to the photographer, but any photographer worth his salt will tell you that it’s really a collaboration, and that they can’t possibly take what their subject won’t give.

So sometimes the whole thing was the photographer’s idea, perhaps backed by a newspaper or other publication. It would be too generous to call it “photojournalism”, it was mostly sensationalist tabloids looking for a quick buck. Other times the bandits went and hired a photographer entirely of their own initiative, to construct their public image by themselves and/or to keep the photos as a private memento. There are accounts of bandits basically kidnapping a photographer and marching him through the wilderness to their hideout, where he is treated like an honoured guest – and also forced to take their portraits, or else. Common props (other than guns) are bandoliers, knives, and various trophies. Sometimes they even take an action pose, pretending to be mid-fight, or hiding for an ambush. Sometimes it’s important to shoot on location and depict them in their element, commanding their realm (a very common moniker for bandits is “King of the Mountains”). The possibilities are endless.

And there’s just something so inherently boastful and defiant, to cheerfully pose for a portrait with a smile and a gun and a price on your head.

Post mortem

As for the photo-shoots of these Italian brigantesse, we know the story of two of them. The first one, of Michelina Di Cesare, was shot very professionally in a studio in Rome. Her photos circulated a lot in the press, and were used as propaganda for her, and her gang, and indirectly the Bourbon loyalists (who may have paid for them). That’s probably why she isn’t wearing her normal clothes, but a traditional peasant costume: she’s dressed up as a folk heroine. Sometimes bandits just had to be media-savvy.

The second one, of Maria Oliverio, was unusually taken after her capture (during which she was injured in the arm). It’s unclear whose idea it was, but she was sentenced to death and then pardoned by the king, her sentence commuted to life in prison. As for the third one, of Filomena Pennacchio and friends, we don’t know how it came to be but it’s pretty ironic, considering that Filomena eventually surrendered and collaborated, leading to the arrest of those same friends she posed with. She was sentenced to 20 years in prison, and eventually did 8.

Maria Oliverio’s post-capture photos (the second set) are remarkable. It’s hard to imagine that they were taken without the consent and supervision of the authorities, so I find it extremely strange that they are actual portraits, the kind which glorifies the bandit, rather than the standard gory post-mortem photographs which police so gleefully distributed after they killed (or executed) bandits. These aimed instead to demystify and ridicule and straight up defile the body, turn the person to a thing, strip the bandit from agency, dignity, sometimes even clothes. (Michelina Di Cesare, who was killed in battle, got that treatment too.) But that’s also a whole field of research in itself (just look up bibliographies for “the criminal corpse”, it’s… quite depressing, really), so I won’t get to it either. Perhaps Oliverio’s captors were vaguely pro-Bourbon too, and that accounts for the strangely flattering photo-shoot, who knows.

559 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japan's third empress regnant, Empress Jitō (645-703) was a powerful and effective ruler. Shrewd, bold and clever, she walked in the footsteps of empresses Suiko and Saimei and prevailed against all odds.

A troubled youth

Jitō was the daughter of Prince Naka no Ōe, the son of empress regnant Saimei. The year she was born, her father killed a minister in front of his mother, leading to her abdication.

Jitō’s maternal grandfather committed suicide three years later, having been wrongly accused of plotting against Prince Naka no Ōe. Jitō’s mother, Ochi, died of grief. Jitō was thus placed in her grandmother's care and raised by the former empress.

At age 12, she was married to her paternal uncle, Prince Ōama, who was 27. Jitō was a reserved person with a brilliant intelligence and much liked by the court. She was curious, open-minded and studied Chinese literature. The death of her grandmother in 661 pained her greatly. In 662, Jitō gave birth to her only child: prince Kusakabe. Her father then ascended took the throne as Emperor Tenji in 667.

Succession struggle

The question of Emperor Tenji’s succession soon arose. The sovereign favored Jitō’s half-brother, Prince Ōtomo, but Prince Ōama had his own ambitions. He and Jitō left the court, waiting for an opportunity to strike.

Ōtomo indeed succeeded Tenji, but Ōama revolted against him soon after with Jitō's support. When they arrived at Ise province, she dressed in male clothes and personally addressed the troops. She also worked on tactical plans. As Ōama left to leave an offensive in Ōmi province, Jitō took command of the troops stationed at Ise. She had indeed volunteered to defend the shrine dedicated to the sun Goddess, Amaterasu.

Their joint efforts led to their success. Ōama ascended the throne in 673 as emperor Tenmu, with Jitō becoming his co-ruler.

The radiant empress

Jitō was very influential in court matters. This was reflected in the choice of Tenmu's heir. He could have chosen his son by another woman, Prince Ōtsu, as his heir, but chose Jitō’s son, Prince Kusakabe, instead.

As Tenmu died in 686, Jitō took the matter in hand. She declared Ōtsu guilty of treason and forced him to commit suicide. She then organized grandiose funerals for her husband and wrote poems expressing her grief.

Oh, the autumn foliage

Of the hill of Kamioka!

My good Lord and Sovereign

Would see it in the evening

And ask of it in the morning.

On that very hill from afar

I gaze, wondering

If he sees it to-day,

Or asks of it to-morrow.

Sadness I feel at eve,

And heart-rending grief at morn—

The sleeves of my coarse-cloth robe

Are never for a moment dry.

Her son died in 689. Since her grandson was too young to rule, Jitō became empress regnant.

She reformed the country, establishing a strong central power and surrounded herself with capable ministers. In 689, she enacted a mandatory code for all local governors. In 690, she launched a population census.

She reformed the army, improving the recruitment conditions and the troops' training. A protector of the arts, she also actively participated in the propagation of Buddhism. Poetry became more refined during her reign. One of her poems was later included in the popular Hyakunin Isshu anthology:

The spring has passed

And the summer come again

For the silk-white robes

So they say, are spread to dry

On Mount Kaguyama

Jitō made her predecessors' objective of replacing the tribal system with a strong central power a reality. Her rule was synonymous with a degree of stability that neither her father nor husband were able to reach. She can be regarded as one of the true founders of Japan’s imperial monarchy. The empress was also fond of travels. In 692, she undertook a trip symbolic trip to Ise province, strengthening her authority and gaining the support of the local people.

The empress indeed took advantage of the Shinto rituals and the image of the sun Goddess to reinforce her legitimacy and used the links between the deity and the imperial family. Such was her prestige that Kakinomoto no Hitomaro, one of the greatest poets of his time, compared her to a goddess.

The retired empress

Jitō’s grandson, Monmu (r. 697-707) was ready to take the throne. She stepped back as Daijō Tennō (or “retired emperor”), becoming the first sovereign in Japanese history to assume this title. The power was in reality still in her hands. The Taihō Code was promulgated in 701, reforming governmental administration as well as administrative and penal law. This was only made possible by the reforms enacted during her reign.

In 702, she went through another tour of inspection of the eastern provinces and bestowed gifts and court ranks on the local officials and leading farmers. Jitō died in the first month 703 and her ashes were interred in her husband's tomb.

Here's is the link to my Ko-Fi if you like what I do! Your support would be greatly appreciated.

Further reading:

Aoki Michiko Y., "Jitō Tennō, the female sovereign",in: Mulhern Chieko Irie (ed.), Heroic with grace legendary women of Japan

Souyri Pierre-François, Nouvelle histoire du japon

#history#women in history#women's history#women's history month#japan#japanese history#powerful women#herstory#historyedit#7th century#queens#historyblr#historical figures#japanese prints#japanese art

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

"As boys and men went out on the boats — “my grandfather was nine when he started,” said the local historian Arlette Julien — girls and women were in the canneries, some from the age of eight, some up to 80. They’d be called in at any time of day or night, whenever the boats came in: in pre-fridge days, sardines needed treating fast.

Dressed in long heavy skirts and clogs, the women would work up to 18 hours non-stop, go home at midnight and then be called back in at 4am. The floors were filthy with mud and sardine guts, the women’s hands wrecked by brine, toilets often a distant rumour … all for 80 centimes an hour. That 80 centimes was just enough to buy a litre of milk, half the wage of a professional washerwoman. All ages earned the same amount.

The strike struck on November 21 and within days 2,100 people were out, 1,600 of them women. The Communist mayor Daniel Le Flanchec pulled the town council behind the strike. He called in Communist support from all over France.

Thus was assured a level of organisation not experienced by earlier French strikes. Funds were raised, soup kitchens sorted, Christmas presents for children arranged and marches assembled. The strike became a national issue.

Finally, though, and after six weeks, the cannery owners were forced to negotiate. They conceded overtime payments, a ban on work for girls under 12 — and a pay rise to one franc an hour. Men got 50 centimes more. “Equal pay wasn’t an issue. The movement was born of desperation,” the history teacher Françoise Pencalet said. “The women simply wanted a little more than what they had.”

#history#women in history#women's history#women's history month#20th century#working women#bretagne#france#french history#upthebaguette#historyblr#historical figures

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

An unprecedented female monarch in her dynasty, Rudrama Devi (r.1262-1289) presided over an age of prosperity. A successful warrior queen, she triumphed over both internal and external threats.

Her father’s heir

Rudrama Devi was the daughter of King Ganapati Deva (r.1199-1262) of the Kakatiya dynasty, who ruled over parts of present-day Telangana and Andhra Pradesh in Southern India. Their capital was located at Orugallu (Warangal).

Ganapati Deva was a successful monarch. His kingdom was famed for its’ diamonds and beautiful fabrics. He had no son to succeed him and his older daughter was already married. He thus decided to make his younger daughter Rudrama Devi his heir and gave her the requisite training.

A female monarch would nonetheless be a in vulnerable position and see her legitimacy questioned. To make female rule more acceptable, he arranged a Putrikayagna ceremony for his daughter. This religious rite allowed a sonless man to declare his daughter or his daughter’s son as his son. After that, Rudrama Devi was also known by the masculine name of Rudra Deva. She also attended all public meetings in masculine attire.

Her story is similar in that regard to that of her near-contemporary, Raziya Sultan of Delhi.

A warrior among warriors

In 1259, Rudrama Devi became her father’s co-ruler and assumed sole rule in 1262. She married the Chalukya prince Virabdhadra, who played no part in her administration, and with whom she had three daughters.

Rudrama Devi faced many threats at once. Her neighbors saw an opportunity to conquer her kingdom and her feudatory noblemen couldn’t stand being ruled by a woman.

She stood her ground and prevailed, proving her might as a warrior queen. Many of her nobles rebelled, but she successfully defeated them. The Seuna Yadava king, Mahadeva, invaded her territories and reached her capital. Rudrama Devi chased him after 15 days of fighting and forced them to pay a heavy tribute in money and horses.

To commemorate her victory, she styled herself “Rayagajakesari” or “the lion who rules over the elephant kings”. In the pavilion she built, she was depicted as a warrior mounted on a lion, holding a sword and a shield, with an elephant trunk holding up a lotus to her in sign of submission.

In 1262, another of her neighbors occupied the Vengi region. She was able to recover it after 12 years of fighting. She was nonetheless unsuccessful in fending off the attacks of her southern rival Ambadeva.

Meritocratic policies

Rudrama Devi completed the construction of the nearly impregnable Warangal Fort. She bought large tracts of land under cultivation, increasing her kingdom’s revenue. She also recruited non-aristocratic warriors from diverse castes. Only 17 percent of her subordinates were of noble background. Prominent commanders could receive lands and become feudatory nobles. She thus established a new warrior class. Since the nobility had rejected her rule, this meritocratic policy allowed her to surround herself with loyal retainers.

Marco Polo, who mistook her for a widow of the previous king, wrote about her very flattering terms, calling her a “lady of much discretion” and a “lover of justice, of equity and of peace”.

A warrior to the end

At the end of her reign, she chose her grandson, Prataparudra, as her heir.

Rudrama Devi likely died in 1289 (though some sources date her death from 1295) according to an inscription made by a member of her army commemorating her recent death and that of her army chief. The cause and location of her death are unknown. She likely died facing Ambadeva's armies, leading her troops as she had always done.

Further reading

Gupta Archana Garodia, The women who ruled India, leaders, warriors, icons

Janchariman M., Perspectives in Indian History From the Origins to AD 1857

Talbot Cynthia, "Rudrama‐devi, Queen of Kakatiya dynasty (r. 1262–1289)", In: The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History.

Talbot Cynthia, Precolonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra

#rudrama devi#13th century#history#women in history#women's history#historyedit#women's history month#india#indian history#queens#powerful women#women warriors#warrior women#historical figures#herstory

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Strong seawomen

You can read more about Iceland's seawomen here!

"Born in 1829, Ísafold Runólfsdóttir grew up on a remote farm in East Iceland near present-day Vopnafjördur. From a family celebrated for their singular strength, Ísafold was known as the best and strongest of the bunch. She was so renowned for her strength that she became part of the folk history of the area, with accounts of her taking on the form and style of the traditional Icelandic narrative tales. She is described as very intelligent, tall, broad-shouldered, handsome with a firm expression, bold, eager in her work, unsparing in her words, unafraid to speak her mind (her language sometimes a bit crass) and overall considered a hero both at sea and on land.

Ísafold went to sea when she was “very young,” first rowing with her father Runólfur. Fishing became her main source of income. She often went out alone, and only the “hardest workers could hope to match her.” As with so many of the seawomen in the historical record, it was not so much for her fishing that Ísafold is remembered but for her personality and phenomenal strength. This included her ability to pull her heavy wooden boat ashore alone—an unheard-of feat. One young seaman recalled that once, when the boat was getting in danger upon encountering rough waves as they neared shore, Ísafold jumped from the boat into the waves, grabbed him, and then tossed him with such a throw that he landed safely on shore. Then she dragged the boat ashore after her. Another account describes how, when unloading hundred-pound bags from the boats with the men, who carried one bag each, Ísafold would often remark, “Well, you are not so strong,” and grab two bags, one in each hand.6 Some speculated that it was the fish oil she took religiously that aided her famous strength—but that she was stronger than almost anyone else, man or woman, was undisputed.

Ísafold also had exceptional skill and strength at a wrestling and martial art form called glíma. Brought from Norway by the early Icelandic settlers, glíma was played in medieval times by men, women, and gods alike—and considered fundamental for a warrior. In the 1800s, it was still popular, and as Ísafold’s reputation at glíma grew, many men came to test themselves against her, including some of the area’s best-known fighters. But always these men found themselves facedown in the “cow muck” in the barn, defeated by Ísafold. Eventually, Ívar Jónsson, a “mountain of a man in both size and strength” came to challenge Ísafold. Their fight was both “long and even,” but “being an experienced fighter,” he was eventually able to take Ísafold to the ground, where she admitted defeat. Even so, Ívar affirmed that “he had never before or since fought a worthier opponent”.

Ísafold was clearly both attractive and independent, and the descriptions of her thwarting sexually aggressive men (usually reported as foreigners), repeated to the delight of the town, take on the tone of parable. These accounts always start by outlining a situation in which some very foolish man or men decide to harass Ísafold. (...).

At this juncture in each account, someone goes running to Ísafold’s father, warning him that his daughter is in danger. Each time he declines to budge, saying that his “little girl” can take care of herself. And each time she competently does. On the ship, some men flee but the rest she sends “one by one rolling down the gangway.” In the other cases, she comes down the stairs holding the man under her arm with his head hanging down. As for the man who wished to “enjoy” her, Ísafold stomps down the stairs with him under her arm, his trousers around his ankles as he ineffectually screams and curses at her. She strides out of the house with him, down to the sea, and, with a grin, tosses him into the water. The laughter of their audience reportedly “rang around them.” The man manages to wade to land, pulling his trousers up as he goes, loudly cursing the woman who did this to him. After this incident, he was reportedly not seen in public for a long time. At each story’s conclusion, various townspeople thank Ísafold, saying that the men are known for their uncontrolled temper or have “been a bother to other women before her.”

Beyond using her physical strength to protect herself, it was clear that Ísafold, like other seawomen such as Foreman Thurídur, stood up for her rights and voiced her opinions—sometimes in fairly outrageous ways. One week in church, Ísafold found the pastor’s sermon objectionable (the account, sadly, neglects to tell us what he said). After the communion service had concluded, she darted outside ahead of the pastor and squatted by the church door, as if to relieve herself. As the pastor walked by, she said, “I guess this was rather pointless. The sacrament has already passed through.”

Ísafold eventually took over the family farm, and adopted her sister’s child after that sister’s death. Although, sadly, Ísafold’s first love died of illness—after she had braved trekking through deep snow and a blizzard trying to save him—she later married and had one son, whom she named after the Saga hero Úlfar the Strong. In addition to her amazing strength and fishing abilities, Ísafold had great skill for natural medicine, healing wounds, and even surgery; when her adopted son tore off two fingers in an accident, she successfully reattached them. According to a local pastor, Ísafold remained strong, living to be “an old lady,” and was still living on a farm as late as 1901. Another source, while agreeing that she had a long life, recorded that after her father died in 1870, Ísafold left farming and moved to a home by the sea.

These stories of Ísafold are rollicking and fun, but they remind us that in the rowboats, the ability and strength to row against wind and current could make the difference between a safe homecoming and death. Even in the early Icelandic Sagas, women with such skills were recognized, though not glorified in the way the men were. In the Saga of Gísli Súrsson, Gísli, who is being hunted down by numerous enemies, travels to Breidafjördur to take refuge with his friend Ingjaldur. When his enemies get wind of his whereabouts, fifteen of them board a ship and head across the bay in pursuit. Meanwhile, Gísli has gone out fishing with Ingjaldur and two of his slaves, a man Svartur and a woman Bóthildur. Sighting the enemy ship, Gísli hurriedly changes places and clothes with Svartur, who rows away with Ingjaldur. Gísli, however, joins Bóthildur, pretending to be Ingjaldur’s well-known “half-wit” son. Ingjaldur and Svartur head for a nearby island, while Bóthildur rows toward the enemies. Through cleverly implying doubt as to the identity of Ingjaldur’s companion, she misleads them into pursuing the other men, thereby saving Gísli’s life. By the time the enemies realize they have been fooled, Bóthildur is already far down the channel. With many men rowing, the enemies rapidly gain on them, but Bóthildur rows so fast that the “steam comes off her,” getting Gísli ashore just before the enemies catch up to them. In thanks, Gísli gives Bóthildur gold to take to Ingjaldur and his wife, along with his request that they free not only her but Svartur as well.

Strength in working at sea was always important, and people who were exceptional got noticed. Examples of women dragging the heavy medieval ships ashore do exist in the Sagas, although later it seems not to have been common until the 1707–8 Plague killed a quarter of the population. During that terrible time, the women dragged up the ships and buried the dead. From then until the early 1900s, when boat construction changed, women dragged the boats to shore alongside their crewmates. Even well into the mid-1900s, on seaside farms, people, including women, were still dragging their boats to the sea. Unnur, the seawoman featured on the cover of this book, recalled this from her youth in the 1950s:

One of my first memories of our boat was helping to push it down to the sea in spring using ribs of whales instead of wooden planks for the boat to slide on. There was a drum at the shore from which we would unwind the wire holding the boat. At the same time a flock of people were supporting the boat so it would stay upright. Then as one rib was loose above the boat it was loose above the boat it was carried down below the boat and so on every time the boat moved further down the slope. When the boat reached the water all ribs were taken and put in the shed.

Historical accounts of strong female rowers also continue throughout the centuries: women rowed record distances—with no helping wind—in record time; seawomen in their seventies exhausted their strong twentysomething-year-old sons; rescues were accomplished due to a woman’s superior rowing; and numerous women rowed in a competitive dare, changing the rhythm to see if the other rowers could keep up. The historical record is full of these women’s adventures, such as those of another seawoman from East Iceland, Helga Sigurdardóttir. Born in 1823, Helga lived to be almost ninety, and, in addition to fishing, she managed her own farm, including the haying and tending the sheep. Like Gudný Sigrídur Magnúsdóttir, Helga ran over mountains, but unless the ground was frozen or it was raining, she ran barefoot. She fished in the spring and autumn, and always wanted someone of equal strength to row with her—something apparently not so easy to find. She was particularly remembered for outrowing everyone in both boats when her boat and a companion boat got caught in a fierce storm together; her strength and encouragement were credited with getting the entire group through the danger safely."

Seawomen of Iceland: Survival on the edge, Margaret Wilson

#history#women in history#women's history#Ísafold Runólfsdóttir#iceland#icelandic history#seawomen#feminism#badass women#herstory#women's history month#Helga Sigurdardóttir#Bóthildur#18th century#19th century#working women#historical figures

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Burginda’s letter is instructing the young man in his spiritual endeavours, and the contents of the (albeit short) letter reveal that she was highly educated and well-read. Written in a period that many still refer to erroneously as an intellectual ‘Dark Ages’, Burginda’s letter uses Greek words, utilises biblical exegesis, imitates Christian poetry like the fifth-century Psychomachia of Prudentius, and references both the sixth-century Italian poet Arator and the classical Roman poet Virgil. It also contains a reworking of a description of heaven found in a Latin poem from Africa that dates to c. 500. Burginda was clearly a very well-read intellectual.

This letter can be used as an example to refute many popular misconceptions about the early middle ages. The first misconception is that antique texts were neglected or unknown in this period. The second misconception is that medieval women were uneducated and unintellectual. The third misconception is that there was little or no intellectual transmission between Africa and Europe in this period. Burginda’s letter proves all these assumptions false. Not bad for two paragraphs of Latin."

#burginda#history#women in history#women's history#8th century#england#english history#female writers#herstory#middle ages#medieval#medieval women

447 notes

·

View notes