#Like that somehow overrides the fact that both of those are like the most common allergens in existence

Text

Thoughts on Deltarune Chapter 2

I wasn't even intending to write a Deltarune post, but here we are!

Have some extended ramblings/theorizing about Undertale, Deltarune, and the role of the "Player" vs character agency.

[Warning: full spoilers for ALL routes in both Undertale and Deltarune!]

.

Frisk’s Agency in Undertale

So I'm not sure how common this is nowadays (I haven't been following Undertale theories for a while), but I personally prefer the interpretation that there is no "Player" as an in-universe force in Undertale. I think it's a far more elegant story if the fourth wall isn't broken.

I'm also fond of the Narrator Chara and "Chara isn't pure evil until Murder Route teaches them to be" interpretations too.

And, of course, the third plank bridging those two is that I don't see Frisk as a just a pure, innocent cinnamon roll.

Because I like the story best when it's Frisk who chooses mercy or murder. It gives Frisk a much more complex character, if they are allowed to have the capacity for both immense kindness and immense cruelty. It even gives them an interesting implied character arc, if you take the natural progression path of True Pacifist > Murder Fun Times > Soulless Pacifist.

Just like Flowey, Frisk first tried to use their powers of Determination for good, but eventually they also grew curious and began to see the world as a game. And then they went too far and ultimately regretted it. Regretted it so much, in fact, that they were willing to sell their soul for just a chance to fix it.

After all, it's not you, the "Player," whose SOUL Chara wants. It's you, Frisk.

I also dislike the idea of an in-universe "Player" because that implies that "Frisk" is nothing but an empty shell - on ALL routes. All of those heartwarming moments in the True Pacifist route? All of the silly Flirt actions? Yeah, that's not Frisk, that's just as much the "Player" puppeting some poor kid's body as the events of the Bad Times.

Who knows what Frisk is truly like if their every action - good or ill - is controlled by some unseen, eldritch force? Now Frisk no longer has any characterization.

And given that said force overrides Frisk's agency, then isn't the "Player" evil no matter which route you take? It's become a story where they only "moral" choice is never to pick up the game at all. Hrm.

Anyway, but that's all Undertale. Which brings me to...

What the heck is going on in Deltarune?

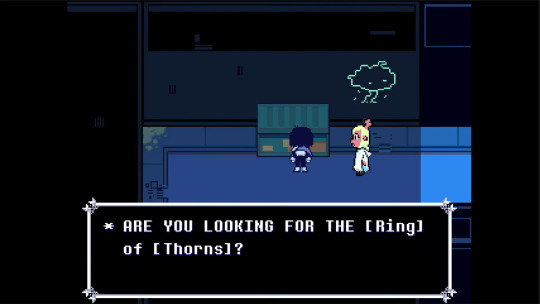

Unlike Frisk=the Red SOUL in Undertale, we don't seem to control Kris=the Red SOUL in Deltarune. The game repeatedly underlines that the player only controls the Red SOUL, not Kris.

(Though, with stuff like the sound of the bathroom faucet only being audible when Kris's actual body is nearby - it seems like even when separated, the Red SOUL may still be perceiving through Kris's other senses besides sight...?)

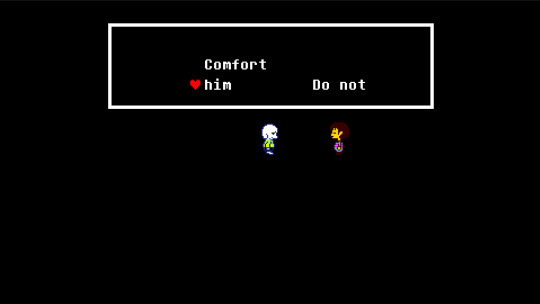

With Spamton's dialogue and Kris's reaction after the non-Weird NEO fight, there's also a lot more emphasis in Deltarune of Kris (and the rest of the party!) being puppeted by some other force. And that's on top of all the stuff in the first chapter highlighting Kris/the Red SOUL's lack of agency.

Because of all those hints, Deltarune seems to be much more explicitly pointing toward that dark interpretation of Undertale - that the "Player"/Red SOUL is removing Kris's agency, regardless of route.

Indeed, I'm somewhat intrigued by the possibility that we/the Red SOUL might be forcing Kris to act nice just as much as we force them to act cruel. The way that Kris deliberately removes the Red SOUL in order to do some very suspicious actions might support that. As do some comments in Chapter 1, like characters in the post-Dark World walkaround noting how Kris is being less weird and more inquisitive than usual. Maybe Kris is the Knight and the Red SOUL is possessing them to undo their evil actions. Maybe the real Kris doesn't want to be friends with Susie and Ralsei at all!

But taking that interpretation to such an extreme also doesn't quite fit. Why does Kris slash the tires on Toriel's car? The only reason I can think of is that they want to keep Susie at their house. And why does Kris create the Dark World in their house? Is Kris creating the fountains because they want to have fun with friends? Especially right after the chapter emphasized how great the Dark World adventures were, that seems very likely.

There are also some smaller details too, of Kris interpreting the Red SOUL's input with their own spin (like saying things sarcastically), or of Kris chatting in a friendly way with Ralsei which the player/SOUL can't influence.

So, I'm pretty sure that even outside of the Red SOUL's control, Kris genuinely does like their friends.

Meanwhile, there were a lot of hints this chapter that Something Bad happened to Kris, Noelle, Dess, and Asriel when they went exploring in the forest by the graveyard. Most likely, they went into that ominous bunker south of the town. Is that incident related to Kris’s current strangeness?

And then, and THEN, there's the Snow Mercy route. That route seems to imply that the Red SOUL is both evil, and very much not Kris. Noelle says Kris isn't like themself, that their voice changes strangely, and she can still hear the creepy voice even when Kris is downed.

How to make sense of this all?

A Theory on Kris and the Red SOUL

One idea is that as scary and zombie-like as Kris looks without the SOUL, they're probably a nice, if lonely kid who desperately wants friends after their big brother went to college. (And possibly after something traumatic happened to them/their neighbor.) They're creating the Dark Worlds for the sake of fun and escapism.

But the Red SOUL puts an end to Kris's happy fantasies. Indeed, if the Red SOUL gives up, "the world is covered in darkness." So without the Red SOUL, would Kris simply keep creating fountains...? (What ARE the fountains, why can Kris and theoretically any Lightener create them?)

Maybe in the normal route, the Red SOUL is trying to gently help Kris move on and accept reality in some way. At the very least, I suspect Ralsei is working toward this goal.

But in that case... that's a pretty strange way for the Red SOUL to go about it, forcibly taking control of Kris to the point that the kid notices and seems to greatly resent it.

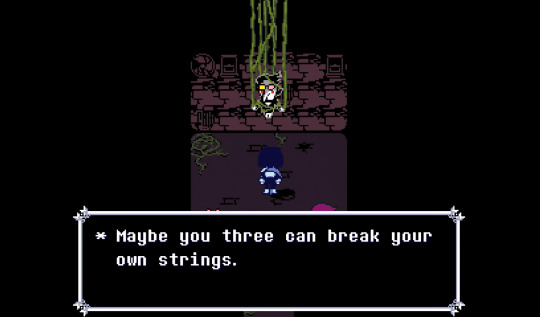

But what if the Red SOUL didn't have a choice about this arrangement either?

After all, the Red SOUL's customized vessel was discarded at the start of Chapter 1... and it was placed into Kris instead.

Here's a question: will Kris die if they're without a SOUL for too long?

Because there are an awful lot of moments in these games where characters break free of something they are bound to, but it doesn't end well:

-Spamton collapses when his strings are cut.

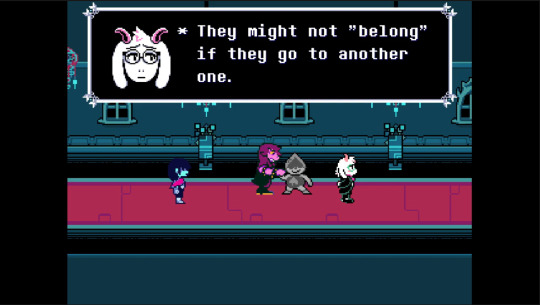

-The Darkeners can move freely outside their origin world for a while, but eventually turn to statues if they stay in another world.

-Regardless of whether Berdly removes the Queen’s wires himself, he's exhausted and unable to fight any more after being under her control.

-And when Kris takes the Red SOUL out of their body, their movements become slow and clumsy. Like it's a struggle for them to move at all.

Meanwhile in Undertale, post-Pacifist Asriel could maintain his form to say goodbye, but without SOUL(s), he inevitably returns to being Flowey.

So here's a theory: Kris died and/or lost their original soul. Perhaps due to some action/inaction on Noelle's part in the exploration incident. And as a last-ditch resort to keep them alive, the Red SOUL was somehow implanted in Kris.

(Also maybe Dess died/went missing at the same time...?)

And now, the Red SOUL the only thing keeping Kris around.

But just like in Undertale, it seems like Deltarune SOULs have wills of their own.

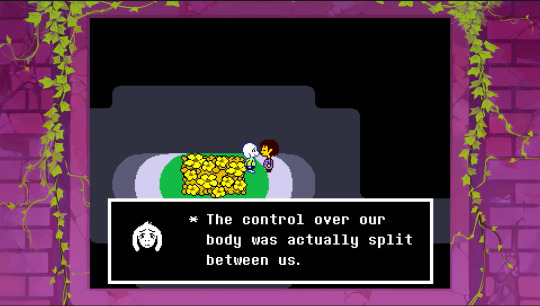

Which means Kris's current state is similar to the Chara-Asriel fusion, or Omega Flowey, or even Frisk-Chara. Control of the body is shared. The difference is that instead of the SOUL we play representing the original owner/will of the body, this time the SOUL we're playing as is the intruder.

Essentially, this time around we are playing the role of the Chara-equivalent instead of the Frisk-equivalent!

(Though whether Kris themself is more of Chara or Frisk I’ll leave to other theorists...)

Anyway, while Kris likely wishes to be rid of the SOUL and dislikes this whole body sharing arrangement, they know they can't survive without it. And perhaps Kris being in a partially soulless state might explain why they do questionable stuff like creating Dark Worlds and slashing their mom's car tires in order to play with their friends. (Again, see also: Asriel/Flowey.)

But when the Red SOUL and Kris are in alignment, things go okay. The Red SOUL suggests commands, but Kris is willing to follow and seems to enjoy being with Susie and Ralsei.

Let’s Talk About Snow Mercy

It's when the Red SOUL and Kris aren't in alignment... well. That seems to be what's happening in the Snow Mercy route. That kind of situation sure didn't go so hot with Frisk and Chara in Undertale, so I doubt this will end nicely for Kris and the Red SOUL either. At the very least, Kris seems to have been visibly upset after what happened with Noelle in this route.

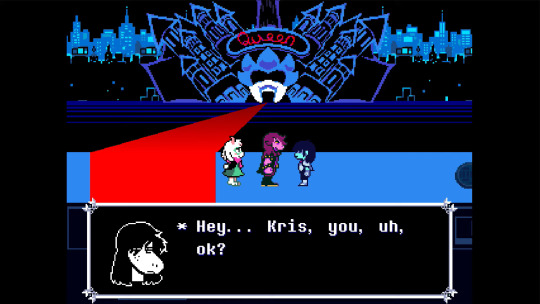

(By the way, there are two other moments in Chapter 2 when Susie asks if Kris is okay - first after the normal Spamton NEO fight and subsequent discussion of what it meant and second after she and Kris approach the bunker.

Three different moments, but Kris appears to react similarly. Are all of these things related? The bunker, Kris being puppeted, and the events of the Snow Mercy route?)

Meanwhile, here’s a contrast. Undertale's Murder Route seemed to exist for the sake of curiosity and power - either the "Player" or Frisk's desires, whichever interpretation you subscribe to. And the changes to the world were all logical consequences of that - because of the Fallen Child's rampage, friendly NPCs disappear, major characters fight you more seriously, etc.

But the actions in Snow Mercy are... weirdly specific, weirdly unpredictable. It doesn't come across as a simple power trip. Instead, Snow Mercy is a bunch of really bizarre actions that feel even more mysterious to the player as they are to Noelle and Kris. I sure wouldn't have guessed that backtracking to the trash heap and freezing a bunch of enemies would lead to new items spontaneously appearing and then giving Noelle access to a scary new spell. It's like something straight out of a creepypasta!

The overall tone that comes across to me is that the Red SOUL seems to know what it's doing, even while the player is kept in the dark. And given Noelle's responses, it almost seems like the SOUL is trying to remind her of events/actions from her past, events which are obviously unknown to the player. All of which leads me to think that the Red SOUL has motives and goals of its own... so just like Undertale, this probably isn't a situation of the "Player" being a fourth wall-breaking force either.

The Red SOUL is its own character.

And I'm certainly curious to find out more about them!

#undertale#deltarune#deltarune chapter 2#frisk#kris#chara#noelle#the red soul#no separate player#undertale analysis#deltarune analysis#my ramblings#read more#is this my first ever deltarune/undertale analysis post?#huh I think it is!#haha I guess I've always just been a reader until now

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

infinity, and beyond

He remembers the first time he kissed Janus. He remembers the way they were curled up against each other, the lights dimmed and the television on low volume, neither of them paying attention to the images on the screen. It was messy and terrible, as far as kisses go, and Patton loved every moment of it, and when they pulled away from each other, they were both breathless, smiling, and he knew then that what he felt, Janus felt too.

He remembers, too, the moment he heard about Virgil.

It's not every day that your husband's long-lost kid breaks into your house. It's not every day that you find out your husband of four years is an alien.

Patton's just trying to roll with the punches.

Content Warnings: threats of violence, mild body horror, brief, non-graphic panic attack

Word Count: 7,168

Pairings: Moceit, parental Anxceit

(masterpost w/ ao3 links)

Patton’s day begins with a teenager holding a knife to his throat.

Technically, the day has already begun; it is mid-morning, the sun inching steadily toward noon. But Patton has barely been awake an hour, has been sitting at the kitchen table with his mug of coffee, staring at all the final exams he has yet to grade as he waits for his brain to start functioning. He likes Saturday mornings; he would go so far as to say that they’re usually his favorite part of the week, because usually, Saturday mornings mean sleeping in, wrapped in his husband’s arms, and later, a big brunch and a lazy day. But today, an emergency called Janus into the office, and he has a backlog of grading to finish this weekend, so here he is. Squinting, bleary-eyed, and with a sad lack of a husband to keep him company.

That is when the teenager appears.

Appears, because there is no better word for what happens. There is no break-in, no slamming of doors or shattering of windows. One minute, he is alone, and the next, there is another person in the kitchen, a young person who can’t be any older than seventeen or eighteen, and Patton barely has time to process that before they lunge for him, knocking him from his chair and to the floor, pinning him against the cool tile.

It takes a second to process the bite of cold, sharp metal against his throat, but as soon as he does, Patton wakes up very, very quickly.

“Please—” he tries, but the teenager hisses at him, actually hisses, and through the panic that is filling his mind and drowning out all logical thought, Patton realizes that something about this isn’t right. Something beyond the fact that there is a knife against his throat and oh god oh god oh god there is a knife against his throat—

The teenager opens their mouth, their face set in a harsh, threatening glare— and it’s their face, there’s something wrong about their face but he can’t quite— but the sounds that come out are gibberish, something guttural and rasping and nothing like any language that Patton has ever heard.

“Please,” he gasps, his voice thin and high and terrified, “please, I don’t know what you’re saying, I can’t—”

He breaks off, because he thinks that if he tries to say any more, it will come out as nonsensical crying, and somehow, he doesn’t particularly think that this person will be swayed by something like that.

The teenager’s lips twist into an impressive scowl, and with the hand not holding the knife, they reach for the pocket of their— hoodie? If it’s a hoodie, it doesn’t quite look like one. It’s something about the fabric, something about the way it moves as they do, but Patton can’t spend energy on figuring that out right now. He tenses as they root around in their pocket, clearly searching for something, and muttering to themself in that same garbled speech pattern. They come up holding something, and Patton can only catch a glimpse of it— what looks like a small, silver disk— before their hand is moving, clapping it against and then inside his ear and—

There is a moment of sharp, almost blinding pain, starting with his ear and shooting through his skull, and then nothing, and he struggles to regain his breath.

“I said,” the teenager growls, “where is he?”

Patton blinks. The sounds they are making are still the same, are still strange and incomprehensible, only, they’re not exactly, because they resolve into recognizable words inside his brain, and if he hadn’t been panicked before, this would definitely be enough to do the job, because what exactly did this person just shove inside his ear?

“What—” he starts, and then the words themselves catch up to him. “Where is who?”

The teenager growls— and it is truly a growl, like an animal would make— and presses the knife in closer. Patton valiantly resists the urge to whimper.

“Don’t fucking play with me,” they snap, and somewhere, back in some hysterical portion of Patton’s mind, he is tempted to chide them for their language. “His DNA signature is all over this fucking house, so where is he? What’ve you done with him?”

Patton can only stare.

Part of his mind has devoted itself to putting the pieces together, no matter the impossible picture they form. Part of his mind is taking in the pale skin that isn’t white at all, but rather a light purple, the way their facial features are just a bit too sharp, a bit too angular to be those of a typical young adult, the way that the spots under and around their eyes aren’t makeup, but instead move, twitching to and fro in unison with their gaze, and that alone is almost enough to send him spiraling, to draw him toward a conclusion that can’t possibly be true, that he can’t possibly comprehend.

The rest of his mind devotes itself to being astonished.

“Are you talking about Janus?” he asks, and he can’t keep the incredulity from his voice.

He doesn’t know which seems more unlikely to him, that this strange, violent, maybe-probably not human person has broken into his house and is threatening him with a sharp knife, or that this strange, violent, maybe-probably not human person is looking for his husband. His husband, who makes him breakfast in bed in the mornings and tea in the afternoons, when he has too many essays to look over and a headache pounding behind his eyes. His husband, who bristles and snarks at everyone around him, who works a corporate job he dislikes and comes home exhausted and irritated at the end of the day and still smiles, that soft, sweet smile that is meant only for him, that nobody else is privileged enough to see. His husband, who he has been married to for four years now, the best four years of his life, who he fell in love with in coffee shops and movie theaters and in the rain, that one day when they were caught out in the park without their umbrellas and had to run all the way home, soaking wet but giggling, grinning and knocking into each other.

His husband, who refuses to talk about his past beyond a sentence or two, here and there, brief anecdotes that never reveal much at all. But Patton has never needed to know his past to know him, and even now, when it seems that his secrets have burst into their shared life in the most violent way possible, disrupting all sense of equilibrium and turning the world on its head, he refuses to believe that there is any secret so great as to force a divide between them.

The teenager— if that is what they are, if the appearance of youth is an accurate indication at all— bares their teeth, teeth that are too sharp, too pointed, teeth that scream predator. “Who else?” they demand. “I won’t fucking ask again. Where is he?”

“He’s not— He’s not here,” he manages. “He’s at work, I don’t know when he’ll be back.”

Please, let that satisfy them. Please, let them leave. Please, let Janus come home. Please, let Janus not come home, let him stay at the office, far away and safe. Please, let him come home and tell me what’s going on, why this is happening, who this is and how they know each other. Please, please, please.

He doesn’t know what he wants. Doesn’t know that he wants to know what he wants.

“Yeah, right,” they say, and he would be insulted by their skepticism if he had room for any emotion other than fear. “That’s likely. You could have him cut up in the basement for all I know.”

He gapes, stunned by the accusation. And for a moment, his indignation is enough to override all common sense, ignore all the impossibilities of the person holding him to the floor, ignore the knife pressing up against his skin. Because, well, first of all, he has no idea where that idea came from, but the very thought that he would do something like that at all, much less to—

“Cut—” he starts, and has to try again, because he can’t wrap his head around the notion, around the idea that that could potentially be something he would want to do, that that is the first thing this person thinks to accuse him of. “Cut up? Janus is my husband.”

Their eyes widen. “Your what?”

“My husband,” he repeats, the reaction emboldening him. “We’ve been married for four years.”

They blink at him, and it’s a motion that takes up their entire face rather than just their eyes, because those moving dots… those are eyes, too. Patton can’t deny it, can’t deny that this person, whatever they are, has eight eyes. Eight eyes, just like a spider, and his outrage fizzles out in the face of that realization, fades back into terror, into a racing pulse and breaths that come too short and quick, and he is confused now too, confused at what this person wants, because their words almost seem to suggest that they don’t want to see Janus harmed at all, that they think he is the threat. That they think he is a threat to Janus.

But Patton isn’t the one with the knife.

“Please,” he says. “Please, just, you can look around the house, there’s pictures of us. We’re together, we’re happy, and I don’t know what you want, but just please, please don’t hurt him.”

“Don’t hurt him?” they repeat, and somehow, whatever strange translation system is at work in his head manages to convey their disbelieving tone. “What the hell are you talking about?”

They seem surprised that Patton is making the insinuation at all, and Patton can’t help the incredulous noise that escapes him.

“You’re holding a knife to my throat!” he all but shrieks, the words ripping out of him at a much higher volume than he intends. “What am I supposed to think you want?”

They make a strangled sound, one that his mind doesn’t resolve into words.

“You—”

And then, they stop, tilting their head. A moment later, Patton hears it too, and dread forms a heavy weight in the pit of his stomach. There is a clattering sound, a key turning in the lock, and the unmistakable creak as the front door opens. The teenager stands, suddenly, a fluid motion, but Patton is frozen in place, barely noticing the removal of the knife and the pressure holding him down, too busy trying to think of a way out of this, or to protect Janus, if worst comes to worst. He’s trembling so hard that he’s not sure how quickly he’ll be able to get up, but once he does, he’s in the kitchen. There are weapons here. All he has to do is grab one, no matter how ill it makes him feel to use his cooking instruments in such a way.

He won’t let this person hurt Janus. Not if he has any say.

“I’m home, love!” Janus’ voice drifts through the house, smooth and unconcerned. There is a familiar thump; that will be his briefcase hitting the floor, and then a rustle of clothing as he sheds his suit jacket. His footsteps draw nearer, and even as the person’s face shifts into an expression Patton has no hope of interpreting, he readies himself to leap to his feet, to fight if need be.

“I just love when idiots call me in for an issue that it would take someone with half a brain twenty minutes to solve,” Janus says, sounding terribly exasperated, and normally, this is when Patton would go to him and give him a hug, would lean his chin on his shoulder and hold him close, or at the very least call out to respond to him. But he stays still and quiet, and the footsteps pause.

“Patton?” He sounds uncertain now, but he’s coming closer again, and Patton finds himself staring fixedly at the entryway to the kitchen, raising his head from the floor to see. Oddly enough, the teenager stands stock still, making no motion to turn to where Janus will appear in mere seconds.

And then, there he is, and Patton cannot help the instantaneous flood of relief at seeing him, at seeing Janus, his husband, poised and confident and unharmed and here. He stands on the threshold, adjusting the gloves on his hands, and Patton watches as his face transitions from calm to confusion to something between anger and fear as he takes in the scene, the toppled chair and rumpled papers, the figure standing in the midst of it all, knife clutched in one hand. And then, he locks gazes with Patton himself, and his eyes blow wide with worry even as the rest of his face schools itself.

“And just who the fuck are you?” he demands of the person. To anyone else, he would sound completely collected, but Patton knows him too well to miss the tremor in his voice.

The person doesn’t move.

“I’d appreciate an answer,” Janus continues. “I’d also appreciate it if you’d step away from my husband.” Janus gives him a tight smile, one that is probably meant to be reassuring, and he returns it as best he can.

And then, slowly, the person pivots on their heel, putting their back to Patton. He can no longer see their facial expression, blank and unhelpful though it was, but he can see Janus’ perfectly well, and as such, he can see the way he holds onto his cool anger for all of five seconds, before it shifts into undiluted shock. His face pales, his lips parting slightly, and he actually takes one stumbling, hesitant step forward, and Patton’s heart begins beating triple time because he has no idea what could make him react like this.

And then, the person speaks.

“Janus,” they say, and the noises that spill from their mouth remain strange and unfamiliar, but somehow, Patton hears the wetness in the name, the fragility, the desperate hope. The knife goes clattering to the floor.

Janus makes a sound, wounded, astonished, and Patton has never heard anything like that come from his husband’s throat, and it scares him.

“Virgil?” he rasps, and evidently, that is all this person needs, because they launch themself forward, and Patton’s instincts scream at him to try to stop them, to leap at them or grab at their hoodie or do something. But Janus’ arms open wide to receive them, and then the two of them are hugging, holding each other tightly, and from here, Patton can see the way Janus’ hands fist in the odd material of the teenager’s clothing, the way he buries his face in their shoulder, and Patton has never been more lost.

Virgil. He recognizes the name, he thinks, and it only takes a moment to summon the memory from the depths of his mind, blurred with age and the faint buzz of alcohol and the heat of the summer night. But Virgil rings out in his mind as clear as a bell, somehow bringing more questions and few answers, because none of this makes any sense at all, because one night, two and a half years ago, Janus told him that he had a son, and that he loved him, and that he lost him, and that his name was Virgil, and then he refused to say any more, and Patton let it go in favor of holding him because the look of devastation on Janus’ face was like none he had ever seen before.

So, this cannot be Virgil. But surely, Janus would know the face of his own son, would never embrace a stranger, and would never embrace… whatever this person is, because Janus is sharp and Janus is observant, and he has most certainly picked up on all their unusual features, on all the ways that they cannot possibly be human. So that means that this must be Virgil after all, and Patton can only watch as they cling to each other, like they’re both afraid the other will disappear if they let go.

And Patton doesn’t know what this means.

-----------

He remembers the first time he kissed Janus. He remembers the way they were curled up against each other, the lights dimmed and the television on low volume, neither of them paying attention to the images on the screen. They stared at each other for a long time before he leaned in, before he dared to take the initiative, and he has never felt happier than in the moment when Janus met him halfway, pressing his lips firmly against his, their noses knocking into each other, their teeth almost clacking together as they sought more, more contact, more closeness. It was messy and terrible, as far as kisses go, and Patton loved every moment of it, and when they pulled away from each other, they were both breathless, smiling, and he knew then that what he felt, Janus felt too.

He remembers, too, the moment he heard about Virgil. He remembers, because he knows only fragments of Janus’ past, a past that he is certain is dark and full of sorrow, and that is why he has never pushed for more than what Janus is willing to give, content to gather up the bits and pieces he is offered and guard them close.

Most of the surrounding conversation is hazy, blurred by one too many glasses of fine wine and a summer heat wave that permeated every inch of the apartment they rented at the time, no matter the efforts of the air conditioner to banish it. But he remembers the way Janus quieted, all of a sudden, face still and contemplative and sad in a way that made his heart clench.

“Have I ever told you,” he said, “that I have a son?”

And he could only stare and shake his head; the answer, of course, was no, the revelation so unexpected that he had no idea how to react.

Janus smiled, small and bitter, like a gash in his face, bleeding him dry. “I do,” he said. “He’s beyond my reach, now. I won’t be able to see him again.”

He remembers he made a noise, tiny and shocked, and that he stretched a hand out, placed it on his, and Janus accepted the touch readily enough.

“His name is Virgil,” Janus continued. “I think he would like you. At least, I hope he would.” He tilted his head, eyes distant. “He’s prickly, slow to trust, abrasive in general. But he’s a good kid. Was a good kid. I suppose he’s not… well. It’s been five years, now.” He closed his eyes, bowing his head. “He would like you,” he repeated, sounding more than a little broken. “He would like you.”

And he didn’t know what to say to that. Didn’t know what to say at all, his words failing him. So he tugged him closer with both arms, leaning him against his chest and rocking him gently, holding him close, and Janus pressed into the contact and didn’t say anything else.

He drew the conclusion that Virgil was dead, died tragically young, somehow. Looking back, he’s not sure how he arrived there, when Janus used the present tense the entire time, quite clearly speaking as though Virgil was alive and well, just somewhere he couldn’t go.

He thinks he might understand that part a bit better now, at least, though most of it refuses to sink in. But the facts are these: Virgil, if this is Virgil, cannot possibly be human. No human looks like he does. And this fact, too, leaves Patton with far more questions than answers.

-----------

“You did what?”

Janus’ voice is loud, sharp, and it brings Patton back to the present in an instant. He doesn’t know how much time has passed while he ruminated, tried to fit all the puzzle pieces together while well aware that he only has about half of them, but Janus and Virgil have drawn back from each other, Janus’ face twisted in alarm.

“We did research before I came down here!” Virgil says. “I’ve seen what humans want to do to us! For all I knew, he’d locked you up in a room and dissected you.”

Ah. So Janus isn’t pleased that his son—his son, his son, this is Janus’ son, his husband’s son— threatened Patton with a knife. Patton would feel more gratified if he weren’t stuck on us, trying desperately to ignore the voice that whispers in the back of his mind, the one that says, well, doesn’t that make sense? Virgil’s not human, that much is obvious, so doesn’t that mean that Janus is—

“You—”

And for the first time since he recognized Virgil, named him aloud, Janus looks at Patton, and Patton looks back, unsure of exactly what emotion is showing on his face. Confusion, probably; lord knows he’s feeling enough of it right now. But for whatever reason, Janus’ expression crumples, and he gently places his hand on Virgil’s shoulder, moving him to the side.

“Virgil,” he says quietly, and for the first time, Patton realizes that he isn’t speaking English at all, but rather, that same unfamiliar language that Virgil has been utilizing, the one that morphs in his head into something that makes sense. “I… need a moment.”

“But we only just—” Virgil begins, turning so that he can see both of them at once. And then, he stops, something odd passing across his face, something that Patton can’t interpret at all. “So you really are… with him.”

“Yes.”

“But he doesn’t know,” Virgil states.

Janus closes his eyes. “No,” he says.

Virgil is silent for a long moment. “Alright,” he says. “I’ll just… go in this other room, I guess. Over here.” And with that, he backs out of the kitchen and into the living room, disappearing from Patton’s line of sight.

Patton glances back to Janus, who is just standing there, still as stone, staring at him, and he opens his mouth, fully intending to chide him for talking about him, or about something tangentially related to him, at least, like he’s not sitting right here. But no sound comes out of his mouth, and suddenly, he finds himself wheezing, gasping for breath as the events of the past few minutes crash over him, and oh god, how is he supposed to process this, reconcile himself to this, because he knew his husband had secrets and he still doesn’t think he understands fully but he does understand just enough to know that everything he thought he knew is not as it seems and he doesn’t know what he’s supposed to do with this and—

“Breathe, Patton,” Janus says, and a gloved hand appears in his vision. He grasps it thankfully, squeezing it tight, and the contact serves to ground him, allows him to calm his panic, little by little, until his mind clears enough to realize that Janus is kneeling in front of him, expression twisted into some awful combination of worry and apprehension and a hesitance that Patton has not seen in a long, long time, not since the earliest days of their relationship, when Janus seemed so uncertain that his affections were welcomed or wanted at all, and Patton had to work so hard to convince him otherwise.

But before he can do something to comfort him, Janus draws into himself, pulling his hand back and looking at the ground. “I suppose you have questions,” he says, and Patton almost laughs at the understatement, restraining himself at the last second.

“Yeah,” he agrees, and he wants to reach out, wants to take Janus’ hand again, but Janus’ body language is so closed off that he’s not sure any touch at all would be welcome. “So, uh, that’s Virgil.”

Janus nods.

“Your son, Virgil.”

Janus nods again, his eyes flickering up for a moment and then back to the floor again.

“I’m sorry he acted the way he did,” he murmurs. “He was scared for me, so he jumped to the worst possible conclusion.”

“There was no harm done,” Patton replies, matching his soft tone. “I mean, that was really scary. I was scared. I think I still am. But I’m not hurt, and everything’s turned out okay.” Even as the words leave his mouth, he has no idea whether he’s telling the truth or not. Have things turned out okay? Have they really? He feels like they’re dancing around the most important subject, the elephant in the room, and what’s more than that, they both know they’re doing it, neither of them quite willing to broach the topic.

But they need to. So Patton does.

“He’s not…” He pauses, taking a breath, marshaling all the courage he has left in him. “He’s not human.”

The statement hangs in the air between them, like a comma in a sentence, waiting for the inevitable continuation.

Janus shakes his head, just slightly, the motion so small that Patton might have missed it had he not been looking. “No,” he says, “he’s not.” And he falls silent, unwilling to elaborate, still unwilling to so much as meet Patton’s eyes, and that leaves the impetus of the conversation on him, doesn’t it? It leaves him to voice the rest, to dare to seek confirmation of a fact that half an hour ago, would have been too unbelievable to consider. Still is, to be frank.

“He’s… an alien. He’s not from earth,” he says, putting off the inevitable for as long as possible. He stares at his husband, who he loves, who he cherishes, who he treasures, who he thought he knew. And he still does, surely, because he knows what Janus is like, knows who he is if not what he is, and that has to be enough. He’s determined to make it enough. “So… are you? An alien, I mean?”

The question is out there, now. There is no taking it back. And Janus looks up at him, finally, expression pained.

“Yes,” he says simply, and Patton has to take a moment to breathe, to wrest his spiraling thoughts back under control, because what exactly is he supposed to make of this? This feels too big for him, too vast and too shocking and too incomprehensible, and nothing, nothing has ever prepared him for this possibility.

“Okay,” he says, even though he feels like it’s really not. “Okay. That’s… okay. I need a second to, um. I just need a second.”

“Of course,” Janus says, inclining his head, and then he moves as if to stand, and no, that is absolutely not what Patton wants, so he grabs at his sleeve with one hand. Janus freezes, staring at the spot where his fingers connect with his shirt.

“That doesn’t mean I want you to leave,” he says, his voice coming out somewhere between cross and petulant. “I can have a second perfectly well with you here.”

“Oh,” Janus says, settling back on the floor. He looks more than a little bit lost, as if he can’t fathom why Patton would want him to stay, and that does hurt a bit, the implication that he thinks Patton might not want him anymore, because of this. Which, he supposes it’s a rational fear; it is, after all, a rather large secret to drop on someone four years into a marriage. But Patton just needs time to process, and once he has, he thinks he’ll be alright.

So, he closes his eyes, focusing on the texture of Janus’ sleeve against his fingers, soft and silky.

What does this change, really? A lot, obviously, but how much of that actually matters? Does Janus being an alien change the fact that he always eats the last of the ice cream, or that he insists on doing the dishes by hand, or that he cried when Bambi’s mom died even though he pretended not to so that he could comfort Patton? Does it change the fact that he’s a terrible blanket hog, or that he denies loving to cuddle but instantly latches onto Patton the moment they’re both in bed together, or that he always seems to know just what to do or say when Patton is tired and sad and all the world feels gray?

Does it change that he loves him?

No. No, it can’t possibly affect any of that at all. And he’s known that all along, really, the realization lurking just under the surface, waiting for him to have it on his own time. He feels relief flood him, because alright. His husband is an alien. It’s going to take a long time for him to be used to that. But he’ll be damned before he lets that come between them.

He opens his eyes.

“I love you,” he says, and he puts all of his sincerity, all of the reassurance he can muster into those three words. And he is prepared to say more, to go on at length about all the reasons why, but Janus winces, turns his head away.

“You can’t say that,” he says. “Patton, you don’t even know what I look like.”

He frowns. Janus’ tone edges on defeat, on something uncomfortably close to despair, and he doesn’t like that at all.

“I’m looking at you right now,” he tries, but Janus just shakes his head.

“I’m a shapeshifter,” he says, cold and biting and yet, still reluctant, as if the admission is being ripped from him. “I literally hide my true appearance from you on a daily basis. I’m not human, and I don’t look like one, not when I’m not trying to.” He turns back to him then, meets his eyes, and it’s almost like a challenge, as if he’s certain in his words, certain that Patton will turn his back on him over something like appearance. And it’s true, this new admission throws him for a bit of a loop, but he thinks if he can accept the fact that he is married to an actual alien, he can accept this, too.

Janus is a very attractive man. But Patton didn’t marry him for his looks. And no matter what sort of alien he is, no matter what he’s hiding, whether it’s tentacles or feathers or extra eyes or what-have-you, Patton will love him just the same. What concerns him most is that Janus doesn’t seem to know that, seems to think that this will be the deal-breaker, will be what sends Patton running. And he is expecting Patton to run; that is becoming increasingly clear with every passing minute.

He spent a lot of time, early on in their relationship, showing Janus that he cared about him, showing Janus that he was allowed to be cared for. He didn’t expect to have to do it again, didn’t expect to have to prove his affections once more, four years into a happy marriage, but he will do whatever it takes.

“Then show me,” he says softly, and pitches his words carefully, trying to make it seem like a request and not a demand, trying to make sure Janus knows that he doesn’t have to do anything at all, not if he doesn’t want to. “Show me what you look like.”

Janus laughs, short and sharp, like a razor’s edge. He passes a hand across his face, and Patton’s fingers finally slip from his sleeve. He removes his hat, and then, to Patton’s surprise, he begins to unbutton his shirt, shrugging it from his shoulders, and then follows that with his gloves. Patton watches as the garments hit the floor, suddenly anxious, though he tries not to show it. Whatever Janus is about to show him, it is crucial that he doesn’t allow himself to have a negative knee-jerk reaction, doesn’t allow himself to recoil before his head and heart catch up to his instincts.

Even if Janus turns into… a giant spider person, or something equally scary, he’ll still love him. He knows that, knows that there is nothing that Janus could do or be to make him stop, but what is most important right now is making sure that Janus knows that.

Janus doesn’t say anything else, just settles back firmly on his haunches, bracing his hands against his thighs, shutting his eyes. And his face slides into something blank, into something impassive, but for just a moment, Patton thinks he sees a flicker of apprehension, even of fear, and he wants nothing more to reach out, to insist that everything is going to be alright. But he knows that Janus won’t believe him right now, will shrug off any touch, so he restrains himself, and watches as Janus begins to change.

It’s slow, at first, subtle. His skin almost seems to ripple in place, and then it— flips, for lack of a better word. It reminds him of Mystique from the X-Men movies, or one of those sequined pillows or shirts that has another color on the other side, revealed when you rub the sequins the other way. His skin flips, and in its place is scales, smooth and gleaming, in dappled patterns all across the left side of his face and down his chest. And as Patton stares, utterly fascinated, they move and shift across his body, curling into different designs and reflecting different colors, green and brown and yellow. And where his skin is still bare, it seems to even out, any blemishes disappearing, and it takes on a slightly yellow tint.

And Patton is so occupied by this that he almost doesn’t see the extra arms, folding out of seemingly nowhere, two extra pairs, one resting limp at his side and the other curling around his abdomen protectively. Three pairs of arms, six hands, each one now tipped with sharp claws, and Patton gapes at them, allowing himself one moment of pure surprise before turning his attention back to Janus’ face.

It looks sharper, more angular, a bit thinner, just different enough to throw him off balance a bit. But looking at Janus, his eyes screwed shut and lips pressed into a thin line, as if awaiting judgment, he can only see his husband there, not the stranger he half feared would take his place.

And the scales, well. The scales are lovely. They shimmer and shine in the light, and Patton can’t quite tell what color they’re trying to be, nor if there is any meaning to their movements across Janus’ skin, but he is captivated by them, by their twisting, shifting beauty. They almost look as if they are dancing.

So, he does the only thing he can think to do, and reaches out to caress his face.

Janus starts, eyes flying open, jerking back, but Patton pursues him, tracing his thumb across his cheekbone. The scales there are smooth and cool to the touch, just slightly bumpy, and Patton runs his fingertips across them, learning their shape and feel. Then, Janus makes a whimpering sound, and he freezes, watching him for any additional reaction.

“I’m sorry,” he says. “Should I not do that? Does it hurt?”

“No,” Janus says, almost a stutter, “no. It— feels good. It’s just, I’m not used to—” He breaks off, shuddering, and he presses his face into Patton’s hand. His eyes are open wide, flitting across Patton’s face, and he realizes that his eyes have changed, too. One is the familiar, warm brown that Patton is used to, but the other is golden-yellow and slit, like a cat, or like a snake, and it’s quite possibly one of the most gorgeous things that Patton has ever seen.

“Oh, sweetheart,” he says. “You’ve been so scared, haven’t you?”

At any other time, he thinks that Janus would deny it. Janus has never been one to admit to his own vulnerabilities, has always preferred to cover everything up in a layer of sarcasm and insults and misdirection, and on the worst days, even he has trouble getting him to admit that something is wrong. But now, Janus just shakes against his hand, his whole body trembling, and says nothing at all.

“I’m so sorry you felt like you needed to hide this,” he tells him. “I think you’re beautiful.”

“I have six arms,” Janus says hoarsely, as if he thinks Patton can’t see them. “Patton, I— I have scales, I have six arms, I have—”

He cuts off with a strangled gasp as Patton grasps one of his hands, one of the new ones, one of the ones hanging at his sides, and brings it up to his lips, planting a gentle kiss on his knuckles.

“They’re very nice arms,” he tells him. “And I think it’s ridiculous that I could have been having six-armed hugs this entire time. Don’t think I’m not going to have you make up for that, mister.”

Janus laughs wetly, and this time, it’s more genuine, and laced with surprise. There are tears in his eyes, Patton realizes, tears in his eyes and beginning to streak down his cheeks, and he reaches out to wipe them away on autopilot. Janus shivers every time he makes contact with a scale, but his eyes never leave his face.

“I love you,” Patton says. “I love you, all of you, no matter what you look like or what planet you’re from. I’d love you if you were a slimy tentacle alien like in the movies. I’d love you if you had an extra head, or, or a really long neck, or if you were secretly two feet tall and bright blue. And I told you on our wedding day that I would follow you to the ends of the earth, do you remember that? But I only said that because I didn’t know that going further was an option.”

He scoots a bit closer, removing his hand from Janus’ face so that he can grab two hands at once, not paying attention to which ones. Janus’ breath hitches.

“If you honestly think,” he says seriously, “that you could ever do anything to get rid of me, you’ve got another thing coming.”

And at that, Janus lets out a sob, loud and messy, and throws himself forward, colliding with Patton’s chest. It’s an awkward angle for a hug, but Patton is too preoccupied to care, is too busy bringing his arms up to hold him, rubbing circles into his back and tracing the scales he finds there. And he’s basking in the sensation, too, drinking in the fact that there are six arms hugging him right now, clutching at him tightly, holding onto the fabric of his shirt for dear life, and he has never felt so safe, never felt so warm. So he relaxes into his husband’s embrace, embraces him in turn, lets him weep and shudder against his chest.

“I’m sorry,” Janus gasps out, “I’m so sorry I doubted you, I—”

“It’s okay,” Patton murmurs. “It’s okay, I’ve got you, I’ve--” He stops, his attention suddenly distracted. “Is that a tail? Do you have a tail?”

It certainly looks like one, snaking its way out of Janus’ pants, long and thin and scaled, and how he missed that, he has no idea. Janus pulls back a bit to look him in the face. His eyes are red-rimmed, his skin flushed orange rather than pink.

“Yes,” he says. “Is that… alright?”

Curious, Patton extends a hand. The tail wraps around his wrist snugly, tugging at his arm, and he giggles a bit.

“Oh goodness,” he says, in lieu of a real response, not bothering to stop the delighted grin that spreads across his face. Janus relaxes, untensing, and slumps forward again to rest his head on his chest, releasing a long, heavy sigh.

“I’m still sorry that I kept this from you,” he murmurs, and Patton glances down at him, carding his free hand through his hair.

“You don’t have to be,” he says.

“Maybe not, but I am,” Janus replies. He shifts in place, angling himself to be able to meet his eyes. And Patton once again finds himself fascinated by his heterochromia, at the contrast between the eye he knows well and the eye that is new. It’s almost a comforting sight, once that reminds him that no matter his appearance, Janus remains the man he knows and loves.

“Did you mean it?” Janus asks. “When you said that you would go further than the earth, if given the option?”

A thrill runs through him. “Are you giving me the option?”

Janus hums. “Virgil is hardly going to be content with leaving me here,” he says, and then twists around further to stare Patton full in the face. “But I won’t leave you,” he insists, voice growing vehement. “And I won’t ask you for more than you’re willing to give. If you want to stay here, then we’ll stay here. The choice is yours.”

And Patton leans forward and kisses him on the lips, soft and short and sweet. “I’ve told you,” he says. “Where you go, I’ll follow.”

And he means it. He means it more than anything else he’s said in his life. He means it with the weight of all the years they’ve spent together, all the love he has to offer. Where Janus goes, he will follow, to the ends of the earth and beyond it, and there is a whole universe out there, waiting to be explored. He will have to make arrangements, of course, will have to contact his school and figure out something to tell his parents, and perhaps he should be dreading that, but all he can feel is exhilaration. Because his husband is an alien, has surely seen so many things that are so much bigger than their little lives here on earth, and yet, he is willing to stay here, with Patton, for Patton, and all Patton would have to do is ask.

But just as Janus has chosen him, he has chosen Janus. And for Janus, he would go anywhere.

“Because you know,” he continues, “I think you’re pretty out of this world. In fact, I’d even say that you’re a real star.”

Janus snorts, messy and undignified, and Patton smiles, pleased by the reaction.

“So, how about you introduce me to your kiddo,” he says. “Without the knives, this time. And you can tell me what I should pack.”

And Janus smiles at him, sweet and joyful, one of those expressions that no one else gets to see. Despite everything, that smile is still the same.

“Okay,” he says, and stands, pulling Patton up with him. “Let’s do that.”

And Patton clasps one of his hands, and lets Janus lead him onward.

----------

End Note: There are plenty of things that I would like to explore in this ‘verse, including putting proper focus on the anxceit, having Virgil deal with suddenly having another dad, Patton continuing to adjust himself to the new circumstances, and whatever the other sides are up to. So, I’m tentatively going to label this as a series. Future installments will be under the tag ‘it’s a space opera (and oh how the arias soar)’

General Taglist: @just-perhaps @the-real-comically-insane @jerrysicle-tree @glitchybina @psodtqueer @mrbubbajones @snek-boii@severelylackinginquality @aceawkwardunicorn @gayerplease

#sanders sides#ts sides#moceit#parental anxceit#patton sanders#ts patton#janus sanders#ts janus#virgil sanders#ts virgil#long post#my fic#it's a space opera (and oh how the arias soar)

503 notes

·

View notes

Text

Steven Schneider, The Paradox of Fiction, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1995)

How is it that we can be moved by what we know does not exist, namely the situations of people in fictional stories? The so-called “paradox of emotional response to fiction” is an argument for the conclusion that our emotional response to fiction is irrational. The argument contains an inconsistent triad of premises, all of which seem initially plausible. These premises are (1) that in order for us to be moved (to tears, to anger, to horror) by what we come to learn about various people and situations, we must believe that the people and situations in question really exist or existed; (2) that such “existence beliefs” are lacking when we knowingly engage with fictional texts; and (3) that fictional characters and situations do in fact seem capable of moving us at times.

A number of conflicting solutions to this paradox have been proposed by philosophers of art. While some argue that our apparent emotional responses to fiction are only “make-believe” or pretend, others claim that existence beliefs aren’t necessary for having emotional responses (at least to fiction) in the first place. And still others hold that there is nothing especially problematic about our emotional responses to works of fiction, since what these works manage to do (when successful) is create in us the “illusion” that the characters and situations depicted therein actually exist.

1. Radford’s Initial Statement of the Paradox

In a much-discussed 1975 article, and in a series of “Replies to my Critics” written over the next two decades, Colin Radford argues that our apparent ability to respond emotionally to fictional characters and events is “irrational, incoherent, and inconsistent” (p. 75). This on the grounds that (1) existence beliefs concerning the objects of our emotions (for example, that the characters in question really exist; that the events in question have really taken place) are necessary for us to be moved by them, and (2) that such beliefs are lacking when we knowingly partake of works of fiction. Taking it pretty much as a given that (3) such works do in fact move us at times, Radford’s conclusion, refreshing in its humility, is that our capacity for emotional response to fiction is as irrational as it is familiar: “our being moved in certain ways by works of art, though very ‘natural’ to us and in that way only too intelligible, involves us in inconsistency and so incoherence” (p. 78).

The need for existence beliefs is supposedly revealed by the following sort of case. If what we at first believed was a true account of something heart-wrenching turned out to be false, a lie, a fiction, etc., and we are later made aware of this fact, then we would no longer feel the way we once did—though we might well feel something else, such as embarrassment for having been taken in to begin with. And so, Radford argues, “It would seem that I can only be moved by someone’s plight if I believe that something terrible has happened to him. If I do not believe that he has not and is not suffering or whatever, I cannot grieve or be moved to tears” (p. 68). Of course, what Radford means to say here is: “I can only be rationally moved by someone’s plight if I believe that something terrible has happened to him. If I do not believe that he has not and is not suffering or whatever, I cannot rationally grieve or be moved to tears.” Such beliefs are absent when we knowingly engage with fictions, a claim Radford supports by presenting and then rejecting a number of objections that might be raised against it.

One of the major objections to his second premise considered by Radford is that, at least while we are engaged in the fiction, we somehow “forget” that what we are reading or watching isn’t real; in other words, that we get sufficiently “caught up” in the novel, movie, etc. so as to temporarily lose our awareness of its fictional status. In response to this objection, Radford offers the following two considerations: first, if we truly forgot that what we are reading or watching isn’t real, then we most likely would not feel any of the various forms of pleasure that frequently accompany other, more “negative” emotions (such as fear, sadness, and pity) in fictional but not real-life cases; and second, the fact that we do not “try to do something, or think that we should” (p. 71) when seeing a sympathetic character being attacked or killed in a film or play, implies our continued awareness of this character’s fictional status even while we are moved by what happens to him. This second consideration—an emphasis on the behavioral disanalogies between our emotional responses to real-life and fictional characters and events—is one that crops up repeatedly in the arguments of philosophers such as Kendall Walton and Noel Carroll, whose positive accounts are nevertheless completely opposed to one another.

Finally, Radford thinks there can be no denying his third premise, that fictional characters themselves are capable of moving us—as opposed to, say, actual (or perhaps merely possible) people in similar situations, who have undergone trials and tribulations very much like those in the story. So his conclusion that our emotional responses to fiction are irrational appears valid and, however unsatisfactory, at the very least non-paradoxical. Summarizing his position in a 1977 follow-up article, with specific reference to the emotion of fear, Radford writes that existence beliefs “[are] a necessary condition of our being unpuzzlingly, rationally, or coherently frightened. I would say that our response to the appearance of the monster is a brute one that is at odds with and overrides our knowledge of what he is, and which in combination with our distancing knowledge that this is only a horror film, leads us to laugh—at the film, and at ourselves for being frightened” (p. 210).

Since the publication of Radford’s original essay, many Anglo-American philosophers of art have been preoccupied with exposing the inadequacies of his position, and with presenting alternative, more “satisfying” solutions. In fact, few issues of The British Journal of Aesthetics, Philosophy, or The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism have come out over the past 25 years which fail to contain at least one piece devoted to the so-called “paradox of emotional response to fiction.” As recently as April 2000, Richard Joyce writes in a journal article that “Radford must weary of defending his thesis that the emotional reactions we have towards fictional characters, events, and states of affairs are irrational. Yet, for all the discussion, the issue has not.been properly settled” (p. 209). It is interesting to note that while virtually all of those writing on this subject credit Radford with initiating the current debate, none of them have adopted his view as their own. At least in part, this must be because what Radford offers is less the solution to a mystery (how is it that we can be moved by what we know does not exist?) than a straightforward acceptance of something mysterious about human nature (our ability to be moved by what we know does not exist is illogical, irrational, even incoherent).

To date, three basic strategies for resolving the paradox in question have turned up again and again in the philosophical literature, each one appearing in a variety of different forms (though it should be noted, other, more idiosyncratic solutions can also be found). It is to these strategies, and some of the powerful criticisms that have been levied against them, that we now briefly turn.

2. The Pretend Theory

Pretend theorists, most notably Kendall Walton, in effect deny premise (3), arguing that it is not literally true that we fear horror film monsters or feel sad for the tragic heroes of Greek drama. As noted above, Walton’s defense of premise (2) also rests on a playing up of the behavioral disanalogies between our responses to real-life versus fictional characters and events. But unlike Radford, who looks at real-life cases of emotional response and the likelihood of their elimination when background conditions change in order to defend premise (1), Walton offers nothing more than an appeal to “common sense”: “It seems a principle of common sense, one which ought not to be abandoned if there is any reasonable alternative, that fear must be accompanied by, or must involve, a belief that one is in danger” (1978, pp. 6-7).

According to Walton, it is only “make-believedly” true that we fear horror film monsters, feel sad for the Greek tragic heroes, etc. He admits that these characters move us in various ways, both physically and psychologically—the similarities to real fear, sadness, etc. are striking—but regardless of what our bodies tell us, or what we might say, think, or believe we are feeling, what we actually experience in such cases are only “quasi-emotions” (e.g., “quasi-fear”). Quasi-emotions differ from true emotions primarily in that they are generated not by existence beliefs (such as the belief that the monster I am watching on screen really exists), but by “second-order” beliefs about what is fictionally the case according to the work in question (such as the belief that the monster I am watching on screen make-believedly exists. As Walton puts it, “Charles believes (he knows) that make-believedly the green slime [on the screen] is bearing down on him and he is in danger of being destroyed by it. His quasi-fear results from this belief” (p. 14). Thus, it is make-believedly the case that we respond emotionally to fictional characters and events due to the fact that our beliefs concerning the fictional properties of those characters and events generates in us the appropriate quasi-emotional states.

What has made the Pretend Theory in its various forms attractive to many philosophers is its apparent ability to handle a number of additional puzzles relating to audience engagement with fictions. Such puzzles include the following:

Why a reader or viewer of fictions who does not like happy endings can get so caught up in a particular story that, for example, he wants the heroine to be rescued despite his usual distaste for such a plot convention. Following Walton, there is no need to hypothesize conflicting desires on the part of the reader here, since “It is merely make-believe that the spectator sympathizes with the heroine and wants her to escape. .[H]e (really) wants it to be make-believe that she suffers a cruel end” (p. 25).

How fictional works—especially suspense stories—can withstand multiple readings or viewings without becoming less effective. According to Walton, this is possible because, on subsequent readings/viewings, we are simply playing a new game of pretend—albeit one with the same “props” as before: “The child hearing Jack and the Beanstalk knows that make-believedly Jack will escape, but make-believedly she does not know that he will. It is her make-believe uncertainty.not any actual uncertainty, that is responsible for the excitement and suspense that she feels” (p. 26).

3. Objections to the Pretend Theory

Despite its novelty, as well as Walton’s heroic attempts at defending it, the Pretend Theory continues to come under attack from numerous quarters. Many of these attacks can be organized under the following two general headings:

A. Disanalogies with Paradigmatic Cases of Make-Believe Games

Walton introduces and supports his theory with reference to the familiar games of make-believe played by young children—games in which globs of mud are taken to be pies, for example, or games in which a father, pretending to be a vicious monster, will stalk his child and lunge at him at the crucial moment: “The child flees, screaming, to the next room. But he unhesitatingly comes back for more. He is perfectly aware that his father is only ‘playing,’ that the whole thing is ‘just a game,’ and that only make-believedly is there a vicious monster after him. He is not really afraid” (1978, p. 13). Such games rely on what Walton calls “constituent principles” (e.g., that whenever there is a glob of mud in a certain orange crate, it is make-believedly true that there is a pie in the oven) which are accepted or understood to be operating. However, these principles need not be explicit, deliberate, or even public: “one might set up one’s own personal game, adopting principles that no one else recognizes. And at least some of the principles constituting a personal game of make-believe may be implicit” (p. 12). According to Walton, just as a child will experience quasi-fear as a result of believing that make-believedly a vicious monster is coming to get him, moviegoers watching a disgusting green slime make its way towards the camera will experience quasi-fear as a result of believing that, make-believedly, they are being threatened by a fearsome creature. In both cases, it is this quasi-fear which makes it the case that the respective game players are make-believedly (not really) afraid.

To the extent that one is able to identify significant disanalogies with familiar games of make-believe, then, Walton’s theory looks to be in trouble. One such disanalogy concerns our relative lack of choice when it comes to (quasi-)emotional responses to fiction films and novels. Readers and viewers of such fictions, the argument goes, don’t seem to have anything close to the ability of make-believe game-playing children to control their emotional responses. On the one hand, we can’t just turn such responses off—refuse to play and prevent ourselves from being affected—like kids can. As Noel Carroll writes in his book, The Philosophy of Horror, “if it [the fear produced by horror films] were a pretend emotion, one would think that it could be engaged at will. I could elect to remain unmoved by The Exorcist; I could refuse to make believe I was horrified. But I don’t think that that was really an option for those, like myself, who were overwhelmedly struck by it” (1990, p. 74).

On the other hand, Carroll also points out that as consumers of fiction we aren’t able to just turn our emotional responses on, either: “if the response were really a matter of whether we opt to play the game, one would think that we could work ourselves into a make-believe dither voluntarily. But there are examples [of fictional works] which are pretty inept, and which do not seem to be recuperable by making believe that we are horrified. The monsters just aren’t particularly horrifying, though they were intended to be” (p. 74). Carroll cites such forgettable pictures as The Brain from Planet Arous and Attack of the Fifty Foot Woman as evidence of his claim that some fictional texts simply fail to generate their intended emotional response.

Another proposed disanalogy between familiar examples of make-believe game-playing and our emotional engagement with fictions focuses on the phenomenology of the two cases. The objection here is that, assuming the accuracy of Walton’s account when it comes to children playing make-believe, it is simply not true to ordinary experience that consumers of fictions are in similar emotional states when watching movies, reading books, and the like. David Novitz, for one, notes that “many theatre-goers and readers believe that they are actually upset, excited, amused, afraid, and even sexually aroused by the exploits of fictional characters. It seems altogether inappropriate in such cases to maintain that our theatre-goers merely make-believe that they are in these emotional states” (1987, p. 241). Glenn Hartz makes a similar point, in stronger language:

My teenage daughter convinces me to accompany her to a “tear-jerker” movie with a fictional script. I try to keep an open mind, but find it wholly lacking in artistry. I can’t wait for it to end. Still, tears come welling up at the tragic climax, and, cursing, I brush them aside and hide in my hood on the way to the car. Phenomenologically, this description is perfectly apt. But it is completely inconsistent with the Make-Believe Theory, which says emotional flow is always causally dependent on make-believe. [H]ow can someone who forswears any imaginative involvement in a series of fictional events.respond to them with tears of sadness? (1999, p. 572)

Carroll too argues that “Walton’s theory appears to throw out the phenomenology of the state [here ‘art-horror’] for the sake of logic” (1990, p. 74), on the grounds that, as opposed to children playing make-believe, when responding to works of fiction we do not seem to be aware at all of playing any such games.

Of course, Walton’s position is that the only thing required here is the acceptance or recognition of a constituent principle underlying the game in question, and this acceptance may well be tacit rather than conscious. But Carroll thinks that it “strains credulity” to suppose that not only are we unaware of some of the rules of the game, but that “we are completely unaware of playing a game. Surely a game of make-believe requires the intention to pretend. But on the face of it, consumers of horror do not appear to have such an intention” (pp. 74-75). Although he disagrees with Walton’s Pretend Theory on other grounds, Alex Neill offers a powerful reply to objections which cite phenomenological disanalogies. In his words, what philosophers such as Novitz, Hartz, and Carroll miss “is that the fact that Charles is genuinely moved by the horror movie.is precisely what motivates Walton’s account”:

By labeling this kind of state ‘quasi-fear,’ Walton is not suggesting that it consists of feigned or pretended, rather than actual, feelings and sensations. Rather, Walton label’s Charles’s physiological/psychological state ‘quasi-fear’ to mark the fact that what his feelings and sensations are feelings and sensations of is precisely what is at issue. .On his view, we can actually be moved by works of fiction, but it is make-believe that we are moved to is fear. (1991, pp. 49-50)Suffice to say, the question whether objections to Walton’s Pretend Theory on the grounds of phenomenological difference are valid or not continues to be discussed and debated.

B. Problems with Quasi-Emotions

In arguing that Walton’s quasi-emotions are unnecessary theoretical entities, some philosophers have pointed to cases of involuntary reaction to visual stimuli—the so-called “startle effect” in film studies terminology—where the felt anxiety, repulsion, or disgust is clearly not make-believe, since these reactions do not depend at all on beliefs in the existence of what we are seeing. Simo Säätelä for example, argues that “fear is easy to confuse with being shocked, startled, anxious, etc. Here the existence or non-existence of the object can hardly be important. When we consider fear [in fictional contexts] this often seems to be a plausible analysis—it is simply a question of a mistaken identification of sensations and feelings. Thus no technical redescription in terms of make-believe is needed” (1994, p. 29). One problem with turning this objection into a full-blown theory of emotional response to fiction in its own right, as both Säätelä and Neill have suggested doing, is that there seem to be at least some cases of fearing fictions where the startle effect is not involved. Another problem is that it is not at all clear what equivalents to the startle effect are available in the case of emotions such as, say, pity and regret.

A similar objection to Walton’s quasi-emotional states has been put forward by Glenn Hartz. He argues not that our responses to fiction are independent of belief, to be understood on the model of the startle effect, but that they are pre-conscious: that real (as opposed to pretend) beliefs which are not consciously entertained are automatically generated by certain visual stimuli. These beliefs are inconsistent with what the spectator—fully aware of where he is and what he is doing—explicitly avows. As Hartz puts it, “how could anything as cerebral and out-of-the-loop as ‘make believe’ make adrenaline and cortisol flow?” (1999, p. 563).

4. The Thought Theory

Thought theories boldly deny premise (1), the old and established thesis, traceable as far back as Aristotle and central to the so-called “Cognitive Theory of emotions,” (see Theories of Emotion) that existence beliefs are a necessary condition of (at the very least rational) emotional response. At the heart of the Thought Theory lies the view that, although our emotional responses to actual characters and events may require beliefs in their existence, there is no good reason to hold up this particular type of emotional response as the model for understanding emotional response in general. What makes emotional response to fiction different from emotional response to real world characters and events is that, rather than having to believe in the actual existence of the entity or event in question, all we need do is “mentally represent” (Peter Lamarque), “entertain in thought” (Noel Carroll), or “imaginatively propose” (Murray Smith) it to ourselves. By highlighting our apparent capacity to respond emotionally to fiction—by treating this as a central case of emotional response in general—the thought theorist believes he has produced hard evidence in support of the claim that premise (1) stands in need of modification, perhaps even elimination.

Even before the first explicit statement of the Thought Theory in a 1981 article by Lamarque, a number of philosophers rejected existence beliefs as a requirement for emotional response to fictions. Instead, they argued that the only type of beliefs necessary when engaging with fictions are “evaluative” beliefs about the characters and events depicted; beliefs, for example, about whether the characters and events in question have characteristics which render them funny, frightening, pitiable, etc. Eva Schaper, for example, in an article published three years before Lamarque’s, writes that:

We need a distinction.between the kind of beliefs which are entailed by my knowing that I am dealing with fiction, and the kind of beliefs which are relevant to my being moved by what goes on in fiction. .[B]eliefs about characters and events in fiction.are alone involved in our emotional response to what goes on. (1978, p. 39, 44)

More recently, but again without reference to the Thought Theory, R.T. Allen argues that, “A novel.is not a presentation of facts. But true statements can be made about what happens in it and beliefs directed towards those events can be true or false. .Once we realize that truth is not confined to the factual, the problem disappears” (1986, p. 66).

Although the two are closely related, strictly-speaking this version of the Thought Theory should not be confused with what is often referred to as the “Counterpart Theory” of emotional response to fiction. As Gregory Currie explains, according to this latter theory, “we experience genuine emotions when we encounter fiction, but their relation to the story is causal rather than intentional; the story provokes thoughts about real people and situations, and these are the intentional objects of our emotions” (1990, p. 188). Walton himself provides an early statement of the Counterpart Theory: “If Charles is a child, the movie may make him wonder whether there might not be real slimes or other exotic horrors like the one depicted in the movie, even if he fully realizes that the movie-slime itself is not real. Charles may well fear these suspected dangers; he might have nightmares about them for days afterwards” (1978, p. 10). Some variations of this theory go so far as make their claims with reference to possible as opposed to real people and situations. Regardless, it is important to note that Counterpart theories have at least as much in common with Pretend theories as with Thought theories, since, like the former, they seem to require a modification of Radford’s third premise (it is not the fictional works themselves that move us, but their real or possible counterparts).

5. Objections to the Thought Theory

Somewhat surprisingly, the Thought Theory has generated relatively little critical discussion, a fact in virtue of which it can be said to occupy a privileged position today. In a 1982 article, however, Radford himself attacks it on the following grounds:

Lamarque claims that I am frightened by ‘the thought’ of the green slime. That is the ‘real object’ of my fear. But if it is the moving picture of the slime which frightens me (for myself), then my fear is irrational, etc., for I know that what frightens me cannot harm me. So the fact that we are frightened by fictional thoughts does not solve the problem but forms part of it. (pp. 261-62]

More recently, film-philosopher Malcolm Turvey criticizes the Thought Theory on the grounds that it appears to ignore the concrete nature of the moving image, instead hypothesizing a “mental entity as the primary causal agent of the spectator’s emotional response” (1997, p. 433). According to Turvey, because we can and frequently do respond to the concrete presentation of cinematic images in a manner that is indifferent to their actual existence in the world, and because there is nothing especially mysterious about this fact, no theory at all is needed to solve the problem of emotional response to fiction film.

Even if it is correct with respect to the medium of film, however, what we might call Turvey’s “concreteness consideration” does not stand up as a critique of the Thought Theory generally. In the case of literature, for example, the reader obviously does not respond emotionally to the words as they appear on the printed page, but rather to the mental images these words serve to conjure in his mind.