#Misenum

Text

2,000-Year-Old Roman Villa Discovered in Naples

A three-year project to build a children’s playground and recreation area south of the Italian city of Naples has unearthed the ruins of a 2,000-year-old clifftop beach house.

Built in the first century, the panoramic mansion — which overlooks the islands of Ischia and Procida — is now partly flooded by the sea. Experts believe it could have once been the opulent residence of Pliny the Elder, the legendary author, naturalist, and commander of the Roman navy fleet stationed there.

The discovery, made last week in the coastal town of Bacoli, unearthed the thick perimeter stone walls of 10 large rooms with floors, tiled walls and a maze of intact panoramic outdoor terraces.

Back in the first century, the mansion would have been located within the Roman port at Misenum, where for four centuries a fleet of 70 ships controlled the Tyrrhenian Sea, the security of which was key to holding the western flank of the Roman empire.

“It is likely that the majestic villa had a 360-degree view of the gulf of Naples for strategic military purposes,” Simona Formola, lead archaeologist at Naples’ art heritage, said in an interview. “We think (the excavation of) deeper layers could reveal more rooms and even frescoes — potentially also precious findings.”

Authorities were surprised by the elaborate style of the walls, which were constructed with diamond-shaped tufa (limestone) blocks placed in a net-like ornamental pattern about 70 centimeters (27.5 inches) below ground.

The villa runs down to a little crumbling stone dock now located about four meters below sea level. That this — and other parts of the unearthed villa — are now underwater is due to the phenomenon of “negative bradyseism,” a term used to describe the gradual descent of the earth’s surface into the sea in areas exposed to frequent volcanic activity. (The area borders a moon-shaped “caldera” or extinct volcanic crater).

Digs will continue in coming months, with authorities hoping to shed further light on not only the form of the beach villa itself, but the broader life and structure of Misenum, one of the most important colonies in the Roman Empire.

“The discovery is even more exceptional given that we know very little (about) the port of Misenum,” said Formola.

As well as acting as a lookout point, Pliny’s beach villa would have also likely been used for leisure. The private dock was where he would greet high-ranking guests arriving by sea for lavish parties. Many Ancient Romans used to flock to Bacoli and the surrounding area, to enjoy their vacation homes and the region’s thermal baths and spa retreats.

Bacoli is located within the so-called “Phlegraean Fields” (or “Fire Plains”), which are dotted with natural geysers and tiny active craters where there are still frequent earthquakes. Due to its blazes and sulphureous vapors, the ancients believed it to be the entrance to the underworld and had dubbed it “the Mouth of Hell.” Indeed it’s possible that Pliny the Elder would have witnessed the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 from the villa. It is known he died trying to rescue those fleeing the calamity.

While archaeologists were reportedly surprised by the finding, local lore had long speculated on the existence of an underground treasure in this location. On the beach neighboring the newly-discovered villa walls, a large brick ruin had been dubbed the “talking wall” by local residents as, in their view, it proved the one-time existence of a large residence.

The site will now become an open-air museum, set to open in the coming weeks. “The ruins of the Roman villa will be cleaned and cordoned-off with wooden fences,” said Bacoli’s mayor Josi Gerardo Della Ragione. “They will be the core of this beautiful space which… our citizens and visitors will get to admire.”

By Silvia Marchetti.

#2000-Year-Old Roman Villa Discovered in Naples#Roman port at Misenum#Pliny the Elder#Emperor Vespasian#Mount Vesuvius#ancient ruins#ancient city#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

extremely funny juxtaposition of "sextus pompey's piracy was starving rome" and "octavian made the difficult decision to dispossess thousands of farmers"

#rome tag#also 'piratical activities' u mean the blockade that resulted in the pact of misenum? those 'piratical activities'?#this book is actually about the emperors so its got to condense the end of the republic to one chapter but still

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Corinne at Cape Misenum by François Gérard

Showing the title character from Corinne, an 1808 novel by Madame de Stael, at Cape Miseno.

#corinne#cape misenum#françois gérard#art#madame de stael#madame de staël#europe#european#cape miseno#napoleonic#germaine de staël#history#painting#france#french#gulf of naples#campania#southern italy#italy#vesuvius#mount vesuvius#landscape

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

2,000-Year-Old Beach House Discovered During Building Work

— By Silvia Marchetti, CNN | Friday January 19, 2024

The Panoramic Mansion Built in the First Century AD, had It's Own Dock, Gardens and Several Terraces overlooking the Italian Islands of Ischia and Procida.

Naples, Italy (CNN) — A three-year project to build a children’s playground and recreation area South of the Italian City of Naples has unearthed the ruins of a 2,000-Year-Old Clifftop Beach House.

Built in the first century, the panoramic mansion — which overlooks the islands of Ischia and Procida — is now partly flooded by the sea. Experts believe it could have once been the opulent residence of Pliny the Elder, the legendary author, naturalist, and commander of the Roman navy fleet stationed there.

The discovery, made last week in the Coastal Town of Bacoli, unearthed the thick perimeter stone walls of 10 large rooms with floors, tiled walls and a maze of intact panoramic outdoor terraces.

Back in the first century, the mansion would have been located within the Roman Port at Misenum, where for four centuries a fleet of 70 ships controlled the Tyrrhenian Sea, the security of which was key to holding the western flank of the Roman Empire.

The house, which could have belonged to Pliny the Elder, would have been used not only as a lookout point but for hosting parties and entertaining. Courtesy Comune Di Bacoli

“It is likely that the majestic villa had a 360-degree view of the gulf of Naples for strategic military purposes,” Simona Formola, lead archaeologist at Naples’ art heritage, told CNN in an interview. “We think (the excavation of) deeper layers could reveal more rooms and even frescoes — potentially also precious findings.”

This 2,300-year-old mosaic made of shells and coral has just been found buried under Rome

Authorities were surprised by the elaborate style of the walls, which were constructed with diamond-shaped tufa (limestone) blocks placed in a net-like ornamental pattern about 70 centimeters (27.5 inches) below ground.

The villa runs down to a little crumbling stone dock now located about four meters below sea level. That this — and other parts of the unearthed villa — are now underwater is due to the phenomenon of “negative bradyseism,” a term used to describe the gradual descent of the earth’s surface into the sea in areas exposed to frequent volcanic activity. (The area borders a moon-shaped “caldera” or extinct volcanic crater).

Digs will continue in coming months, with authorities hoping to shed further light on not only the form of the beach villa itself, but the broader life and structure of Misenum, one of the most important colonies in the Roman Empire.

“The discovery is even more exceptional given that we know very little (about) the port of Misenum,” said Formola.

Archaeologists were surprised by the elaborate structure of the walls, which are made from limestone blocks called "Tufa." Courtesy Comune Di Bacoli

As well as acting as a lookout point, Pliny’s beach villa would have also likely been used for leisure. The private dock was where he would greet high-ranking guests arriving by sea for lavish parties. Many Ancient Romans used to flock to Bacoli and the surrounding area, to enjoy their vacation homes and the region’s thermal baths and spa retreats.

Bacoli is located within the so-called “Phlegraean Fields” (or “Fire Plains”), which are dotted with natural geysers and tiny active craters where there are still frequent earthquakes. Due to its blazes and sulphureous vapors, the ancients believed it to be the entrance to the underworld and had dubbed it “the Mouth of Hell.” Indeed it’s possible that Pliny the Elder would have witnessed the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 from the villa. It is known he died trying to rescue those fleeing the calamity.

‘Lost’ ancient Roman palace reopens after 50 years of neglect

While archaeologists were reportedly surprised by the finding, local lore had long speculated on the existence of an underground treasure in this location. On the beach neighboring the newly-discovered villa walls, a large brick ruin had been dubbed the “talking wall” by local residents as, in their view, it proved the one-time existence of a large residence.

The site will now become an open-air museum, set to open in the coming weeks. “The ruins of the Roman villa will be cleaned and cordoned-off with wooden fences,” said Bacoli’s Mayor Josi Gerardo Della Ragione. “They will be the core of this beautiful space which… our citizens and visitors will get to admire.”

#Beach House#2000-Year-Old Clifftop Beach House 🏠#Silvia Marchetti#CNN#Naples | Italy 🇮🇹#Italian Islands of Ischia and Procida#Coastal Town of Bacoli#Roman Port at Misenum#Roman Empire#Tyrrhenian Sea#Bacoli’s Mayor | Josi Gerardo Della Ragione

1 note

·

View note

Text

Early in the morning of October 25, 79 (year 832 in ancient Rome), Pliny the Elder died on the coast of Stabia during the expulsion of the last pyroclastic surge that came out of Vesuvius. The interesting thing is that he is the only ancient writer, and important Roman soldier and politician who died due to a natural disaster. Ironically, his passion was the study of nature. Pliny, born in 23, spent his childhood and teens during the dark reign of Tiberius ( 14-37) whom he referred to as "the saddest of men". He praised the emperor Claudius (41-54) saying that "Claudius was one of the best writers". During the reign of Nero (54-68) Pliny attended the construction of the Domus Aurea, emperor's palace.

Pliny began his military career in Germania. During the reign of Vespasian (December 69-June 79) he was procurator in Gaul and Hispania. Pliny was a close friend of Emperor Vespasian who in 77 appointed him commander of the Roman navy and that is why Pliny settled with his family in Misenum (the same city where emperor Tiberius died) on the coast of the Gulf of Naples, near Pompeii. He tried to help in the disaster but ended up among the victims of one of the most famous and deadly volcanic eruptions in history.

The day of the eruption, the youngest son of Vespasian, brother of the then emperor Titus and who two years later would become emperor Domitian, was celebrating his birthday.

Today we know what happened thanks to Pliny the Younger, also a writer, who documented in detail what he saw from Misenum as well as the testimonies he heard from the survivors in Stabia who were with his uncle.

185 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Eruption of Mt. Vesuvius

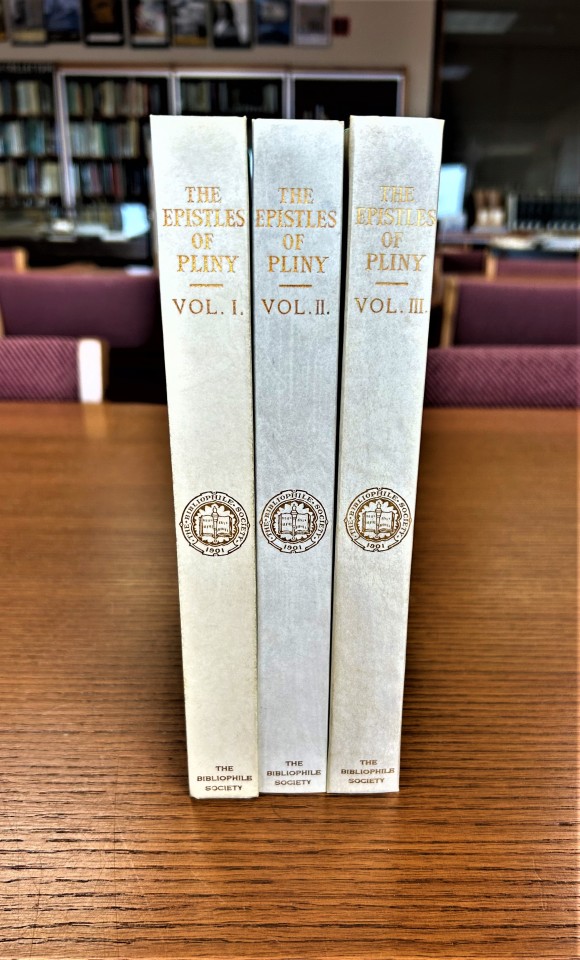

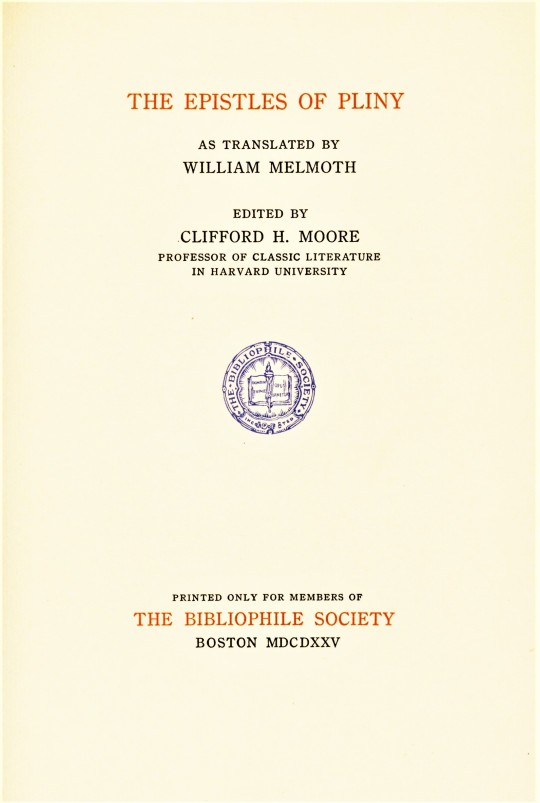

The Eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 CE remains one of the deadliest natural disasters in recorded history. Not only did the volcano destroy the economically powerful city of Pompeii, but Herculaneum, Oplontis, Stabiae were also buried and thus lost to the Roman Empire. The number of victims is unknown, but given the size of the four cities, estimates have reached over 18,000 individuals.

Today only one first-hand account of this horrific event survives in two letters from Pliny the Younger to the Roman historian Tacitus. They are preserved as letters 6.16 and 6.20 in the collected Epistles of Pliny. Among our holdings of the works of Pliny is this 3-volume set of the Epistles with William Melmoth’s 18th-century translation edited by Clifford Herschel Moore, and printed by the Harvard University Press in an edition of 405 copies for members of The Bibliophile Society, Boston, in 1925.

While the term ‘volcanic eruption’ evokes scenes of lava and fire, the reality is much more frightening. Curiously, there is no word for volcano in the Latin language. While ancient Romans were aware of the destructive power of volcanoes, there’s some debate about whether they were aware that Vesuvius was a volcano before its eruption. Signs of the eruption began back in 62CE with a great earthquake that caused much of the city to collapse. Smaller earthquakes continued over the next 15 years until one was accompanied by the rise of a column of smoke from Mt. Vesuvius in October 79 CE.

The hot gases that made up the column of smoke began to cool, darkening the sky, and not long after a rain of pumice began to fall, and after 15 hours ceilings began to collapse. Nevertheless, many residents chose to take shelter rather than flee. At 4am the first 500C pyroclastic surge barred down the volcano, burying Herculaneum. Six more of these surges occurred before the end of the eruption, destroying Pompeii, Oplontis, and Stabiae.

The 17-year old Pliny was in the port town of Misenum across the Bay of Naples from the volcano at the time. Pliny’s uncle, Pliny the Elder, commander of the Roman fleet at Misenum, launched a rescue mission and went himself to the rescue of a personal friend. The elder Pliny did not survive the attempt. In Pliny the Younger’s first letter to Tacitus, he relates what he could discover from witnesses of his uncle's experiences. In a second letter, he details his own observations after the departure of his uncle.

Mt. Vesuvius is still active and according to volcanologists, erupts about every 2000 years, which would be right about now. Who will be our next Pliny the Younger?

Our copy of The Epistles of Pliny is another gift from our friend and benefactor Jerry Buff.

View more of my Classics posts.

– LauraJean, Special Collections Undergraduate Classics Intern

#Classics#classical history#Roman History#Mt. Vesuvius#Eruption of Mt. Vesuvius#Pliny the Younger#Epistles of Pliny the Younger#Pliny the Elder#Tacitus#William Melmoth#Clifford Herschel Moore#Harvard University Press#The Bibliophile Society#volcanic eruptions#Pompeii#herculaneum#Oplontis#Stabiae#Jerry Buff#LauraJean

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day in Wikipedia: Saturday, 23rd September

Welcome, Bienvenida, नमस्ते, Velkommen 🤗

What does @Wikipedia say about 23rd September through the years 🏛️📜🗓️?

23rd September 2021 🗓️ : Death - John Elliott (businessman)

John Elliott, Australian businessman (b. 1941)

"John Dorman Elliott (3 October 1941 – 23 September 2021) was an Australian businessman and state and federal president of the Liberal Party. He had also been president of the Carlton Football Club. He frequently provoked controversy due to his political affiliations, his brushes with the law, and..."

23rd September 2018 🗓️ : Death - Jane Fortune

Jane Fortune, American author, journalist, and philanthropist (b.1942)

"Jane Fortune (August 7, 1942 – September 23, 2018) was an American author and journalist. Many of her publications and philanthropic activities were centered on the research, restoration, and exhibition of art by women in Florence, Italy. ..."

23rd September 2013 🗓️ : Death - Abdel Hamid al-Sarraj

Abdel Hamid al-Sarraj, Syrian colonel and politician (b. 1925)

"Abdel Hamid Sarraj (Arabic: عبد الحميد السراج, September 1925 – 23 September 2013) was a Syrian Army officer and politician. When the union between Egypt and Syria was declared, Sarraj, a staunch Arab nationalist and supporter of Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, played a key role in the..."

Image by Not credited

23rd September 1973 🗓️ : Event - September 1973 Argentine presidential election

Argentine general election: Juan Perón returns to power in Argentina.

"The second Argentine general election of 1973 was held on 23 September...."

Image by Unknown authorUnknown author

23rd September 1923 🗓️ : Birth - Mohamed Hassanein Heikal

Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, Egyptian journalist (d. 2016)

"Mohamed Hassanein Heikal (Arabic: محمد حسنين هيكل; 23 September 1923 – 17 February 2016) was an Egyptian journalist. For 17 years (1957–1974), he was editor-in-chief of the Cairo newspaper Al-Ahram and was a commentator on Arab affairs for more than 50 years.Heikal articulated the thoughts of..."

Image by Not provided

23rd September 1823 🗓️ : Birth - John Colton (politician)

John Colton, English-Australian politician, 13th Premier of South Australia (d. 1902)

"Sir John Blackler Colton, (23 September 1823 – 6 February 1902) was an Australian politician, Premier of South Australia and philanthropist. His middle name, Blackler, was used only rarely, as on the birth certificate of his first son. ..."

Image by not identified

23rd September 🗓️ : Holiday - Christian feast day: Sossius

"Saint Sossius or Sosius (Italian: Sosso, Sossio or Sosio; 275 – 305 AD) was Deacon of Misenum, an important naval base of the Roman Empire in the Bay of Naples. He was martyred along with Saint Januarius at Pozzuoli during the Diocletian Persecutions. His feast day is September 23, the date, three..."

Image licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0? by Sailko

0 notes

Text

The only surviving eyewitness account of the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius was written by Roman senator and writer Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, more commonly known as Pliny the Younger. He was seventeen years old in 79 AD and watched the terrible event unfold from the home of his uncle in Misenum, (modern day Miseno, across the Bay of Naples.

English translation of Pliny’s account:

"Meanwhile, my mother and I had stayed at Misenum. After my uncle left us, I studied, dined, and went to bed, but I slept only fitfully. We had earth tremors for several days, which were not especially alarming because they happen so often in Campania. But that night they were so violent that everything felt as if it were being shaken and turned over. My mother came hurrying to my room, and we sat together in the forecourt facing the sea.

By six o'clock, the dawn light was still only dim. The buildings around were already tottering, and we would have been in danger in our confined space if our house had fallen down. This made us decide to leave town. We were followed by a panic-stricken crowd that chose to follow someone else's judgement rather than decide anything for themselves. We stopped once we were out of town, and then some extraordinary and alarming things happened. The carriages we had ordered began to lurch to and fro, although the ground was flat, and we could not keep them still even when we wedged their wheels with stones. Then we saw the sea sucked back, apparently by an earthquake, and many sea creatures were left stranded on the dry sand. From the other direction over the land, a dreadful black cloud was torn by gushing flames and great tongues of fire like much-magnified lightning.

The cloud sank down soon afterwards and covered the sea, hiding Capri and Capo Misenum from sight. My mother begged me to leave her and escape as best I could, but I took her hand and made her hurry along with me. Ash was already falling by now, but not very thickly. Then I turned around and saw a thick black cloud advancing over the land behind us like a flood. "Let us leave the road while we can still see", I said, "or we will be knocked down and trampled by the crowd". We had hardly sat down to rest when the darkness spread over us. But it was not the darkness of a moonless or cloudy night; it was just as if the lamps had been put out in a completely closed room.

We could hear women shrieking, children crying, and men shouting. Some were calling for their parents, their children, or their wives and trying to recognise them by their voices. Some people were so frightened of dying that they actually prayed for death. Many begged for the help of the gods, but even more imagined that there were no gods left and that the last eternal night had fallen on the world. There were also those who added to our real perils by inventing fictitious dangers. Some claimed that part of Misenum had collapsed or that another part was on fire. It was untrue, but they could always find somebody to believe them.

A glimmer of light returned, but we took this to be a warning of approaching fire rather than daylight. But the fires stayed some distance away. The darkness came back, and ash began to fall again, this time in heavier showers. We had to get up from time to time to shake it off, or we would have been crushed and buried under its weight. I could boast that I never expressed any fear at this time, but I was only kept going by the consolation that the whole world was perishing with me.

After a while, the darkness paled into smoke or cloud and the real daylight returned, but the sun shone as weakly as during an eclipse. We were amazed by what we saw because everything had changed and was buried deep in ash like snow. We went back to Misenum and spent an anxious night switching between hope and fear. Fear was uppermost because the earth tremors were still continuing and the hysterics kept on making their alarming forecasts.”

Source:

https://igppweb.ucsd.edu/~gabi/sio15/lectures/volcanoes/vesuvius.html

0 notes

Text

Saint of the Day –23 September – Saint Sosius (275-305) Confessor, Deacon and Martyr.

Saint of the Day –23 September – Saint Sosius (275-305) Confessor, Deacon and Martyr.

Saint of the Day –23 September – Saint Sosius (275-305) Confessor, Deacon and Martyr. His holiness and wisdom drew many Prelates to his feet, seeking spiritual assistance. St Sosius was a Deacon of Misenum, an important naval base of the Roman Empire in the Bay of Naples. Born in 275 in Miseno, Italy and died by being beheaded on 19 September 305, along with St Januarius, at Pozzuoli, Campagna,…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

“ [...] I make a habit, when I have time, of reading the works of these authors and a few more. To what purpose then? Well, I will own to some benefit: just as, when walking in the sunshine, though perhaps taking the stroll for a different reason, the natural result is that I get sunburnt, even so, after perusing those books rather closely at Misenum (having little chance in Rome), I find that under their influence my discourse takes on what I may call a new complexion.”

— Cicero, De Oratore, II, xiv, 59-60.

0 notes

Photo

23 March, 59 CE - Agrippina the Younger is murdered

View towards the crime scene from Pozzuoli.

Baiae is far right (blank spot / Museum of Campi Flegrei) and Misenum harbour/military base is on the left side of the pic (hill & surrounding areas).

Agrippina’s villa is located between them - IIRC somewhere in the densely built area that can be seen in the middle of the photo. [3001 x 1575]

Pozzuoli, July 2019

#Agrippina the Younger#crime scene#murder#Baiae#Pozzuoli#today in history#julioclaudian dynasty#ancient Rome#my photo#Misenum

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pompeii Still Has Buried Secrets

The first major excavations in decades shed light on how ordinary citizens shopped and snacked—and where slaves slept.

— By Rebecca Mead | Published November 22, 2021 | Friday June 30, 2023

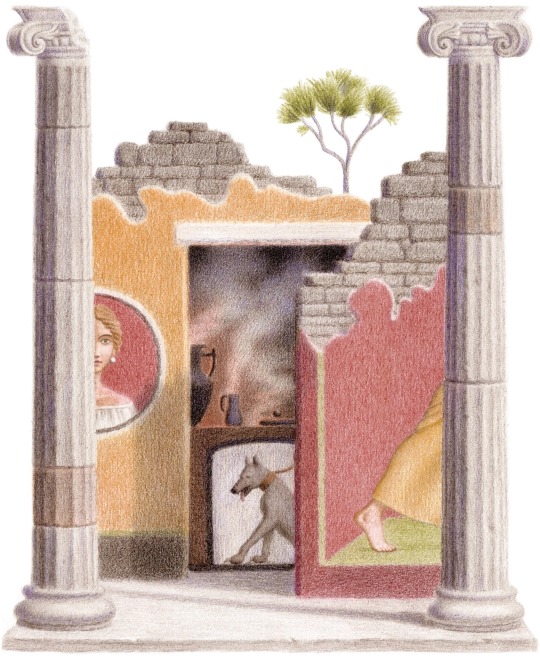

The ancient city was two miles in circumference. A third of it is still unexcavated. Illustration By Daniele Castellano

The journey from Naples to the ruins of Pompeii takes about half an hour on the Circumvesuviana, a train that rattles through a ribbon of land between the base of Mt. Vesuvius, on one side, and the Gulf of Naples, on the other. The area is built up, but when I travelled the route earlier this fall I could catch glimpses of the glittering sea behind apartment buildings. Occasionally, the mountainous coast across the bay came into sight, in the direction of the old Roman port of Misenum—where, in 79 A.D., the naval commander and prolific author Pliny the Elder watched Vesuvius erupt. Pliny, who led a rescue effort by sea, was killed by one of the volcano’s surges of gas and rock; his nephew, Pliny the Younger, provided the only surviving eyewitness account of the disaster. My view sometimes opened up in the opposite direction, toward the volcano, to reveal farmland or a stand of umbrella pines, their tall trunks giving way to billowing needle-covered branches. Pliny the Younger compared the shape of these trees to the volcanic eruption, with its column of smoke rising to a puffy cloud of ash that hovered, and then collapsed, burying a good part of what is now the Circumvesuviana’s route.

I got off at the stop called Pompeii Scavi—“the ruins of Pompeii”—and headed toward the modern gates that surround the ancient city. Before Pompeii was drowned in ash, it had a circumference of about two miles, enclosing an area of some hundred and seventy acres—a fifth the size of Central Park. Its population is estimated to have been about eleven thousand, roughly the same number as live in Battery Park City. After the ruins were rediscovered, in the mid-eighteenth century, formal excavations continued throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, with successive directors of the site exposing mansions, temples, baths, and, eventually, entire streets paved with volcanic rock. About a third of the ancient city has yet to be excavated, however; the consensus among scholars is that this remainder should be left for future archeologists, and their presumably more sophisticated technologies.

At some ancient Roman sites, such as nearby Herculaneum, unexcavated areas have been topped with contemporary buildings. But at Pompeii, once you walk inside the gates, you can almost block out the modern world: the ancient city is full of spectacular vistas, with the straight lines of its gridded streets leading to Vesuvius in the distance. And, every so often, a visitor comes across a street or an alleyway that dead-ends at a twenty-foot-high escarpment covered with scrubby grass. This is the boundary between Pompeii’s revealed past and its still buried one.

I had come to Pompeii to explore one such boundary, at the abrupt terminus of the Vicolo delle Nozze d’Argento—the Street of the Silver Wedding—in a corner of what archeologists have designated as Regio V, the city’s fifth region. For many years, the formal excavations stopped here, just past one of Pompeii’s grandest mansions: the House of the Silver Wedding, which was uncovered in the late nineteenth century and named, in 1893, in honor of the twenty-fifth wedding anniversary of the Italian monarch, Umberto I, and his wife, Margherita of Savoy. The spacious house, which is believed to have belonged to a Pompeiian bigwig named Lucius Albucius Celsus, included a salon fitted with a barrel-vaulted ceiling supported by columns of trompe-l’oeil porphyry, and an atrium, decorated with frescoes, that scholars regard as the finest of its kind in the city.

In the ruins of Pompeii, discovery has often gone hand in hand with destruction. Photograph by Michele Amoruso/Getty

I discovered that the mansion was closed for renovations: the clattering of workmen emanated from behind its high brick walls. But I wasn’t too disappointed—my interest was in what lay just beyond it, at a newly exposed crossroads. This is the site of the first significant excavations in decades of ruins embalmed by the 79 A.D. eruption. Since 2018, restoration work has been under way in Regio V to reshape and shore up the escarpment. Made up of impacted ash and lapilli, or pebbles of pumice, it had become increasingly vulnerable to collapse, especially after heavy rain. (When chunks of the escarpment broke off, artifacts and structures buried inside it were often obliterated.) Collapses aside, the weight of the unexcavated land in Regio V put the adjacent excavated area at risk by exerting immense pressure on exposed walls, some of which date to the first or second century B.C. The fragile escarpment threatened to make a ruin of the ruins.

Through a careful combination of archeology and engineering, the escarpment has been reshaped into a more gradual slope, with an exposed surface of rocky fragments secured by sturdy mesh. In order to lessen the gradient, it has been necessary to unearth a small area of previously buried streets and structures. In recent decades, most archeological excavations at Pompeii have been of layers that predated the first-century city—digging down to reveal, for example, that several of the town’s temples were built on structures that dated to the sixth century B.C. The new excavations in Regio V—conducted with the latest archeological methods, and an up-to-the-minute scholarly focus on such issues as class and gender—have yielded powerful insights into how Pompeii’s final residents lived and died. As Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, a professor emeritus at Cambridge University and an authority on the city, told me, “You only have to excavate a tiny amount in Pompeii to come up with dramatic discoveries. It’s always spectacular.”

My guide to the restorations of Regio V was Gabriel Zuchtriegel, who this past February was appointed the director of the Archeological Park of Pompeii. Forty years old, the German-born Zuchtriegel was formerly the director of the archeological site at Paestum, forty-odd miles south of Pompeii. As we walked around Regio V, he deftly navigated the uneven roads and talked about ongoing work: “We are not going to excavate just for the sake of excavating. It would be very problematic, and somehow irresponsible.” However, in the course of stabilizing this stretch of the boundary, in 2019, archeologists realized that they had come upon a structure worthy of a full excavation: a thermopolium, or snack bar, which was situated just across the street from the House of the Silver Wedding, as if the Frick mansion were cheek by jowl with a Gray’s Papaya.

The thermopolium, which opened to visitors in August, is a delight. A masonry counter is decorated with expertly rendered and still vivid images: a fanciful depiction of a sea nymph perched on the back of a seahorse; a trompe-l’oeil painting of two strangled ducks on a countertop, ready for the butcher’s knife; a fierce-looking dog on a leash. The unfaded colors—coral red for the webbed feet of the pitiful ducks, shades of copper and russet for the feathers of a buoyant cockerel that has yet to meet the ducks’ fate—are as eye-catching now as they would have been for passersby two millennia ago. (Today, they are protected from the elements and the sunlight by glass.) Another panel, bordered in black, is among Pompeii’s most self-referential art works: a representation of a snack bar, with the earthenware vessels known as amphorae stacked against a counter laden with pots of food. A figure—perhaps the snack bar’s proprietor—bustles in the background. The effect is similar to that of a diner owner who displays a blown-up selfie on the wall behind his cash register.

It turns out that few of Pompeii’s more straitened residents had a place at home to cook. “Rich people had kitchens in their houses, and banquet rooms and gardens,” Zuchtriegel told me, as we walked around the thermopolium. “But most inhabitants didn’t live in such places—they had small apartments, or even one-room flats. During the daytime, their place was a shop or a workshop, and at night the family would just close up the front and sleep there. And, when they could afford it, they would come here and have a warm meal, and take their plate and eat it on the street.”

Several tourists were peering through the glass into the thermopolium, as if they were hungry Pompeiians surveying the fare on offer. Zuchtriegel took a step back, toward a fountain; it would have provided fresh water for drinking, bathing, or cooling down. “It was life on the street, as today we can still see in Naples,” he said.

In 2018, a fresco of Cupid was discovered inside a sumptuous, newly excavated villa that has been named the House of the Garden. Photograph by Carlo Hermann/Getty

The thermopolium on the Vicolo delle Nozze d’Argento is far from unique—through the centuries, about eighty such establishments have been identified in Pompeii. But archeological science is now more evolved, Zuchtriegel told me, and at the new site scholars “can use modern technologies and methodologies to analyze what was inside the pots.” Fragments of duck bone were discovered in one of the containers, which are known as dolia, suggesting that the paintings of ducks served not just as decoration but as advertising. In other dolia, scholars found traces of cooked pig; what appears to be a stew of sheep, fish, and land snails; and crushed fava beans. A book of recipes attributed to Apicius, a celebrated Roman gourmet from the first century A.D., explains that “bean meal” can be used to clarify the color and flavor of wine.

These near-invisible remains of foodstuffs do not just provide information about the diet of Pompeii’s working classes. According to Sophie Hay, a British archeologist who has worked extensively at Pompeii, they also shed new light on the rhythms of civic life. “Up until this bar was excavated, people who study these things have gone around believing that the dolia contained only dry foodstuffs,” she told me. “There are Roman laws that said bars shouldn’t serve this kind of warm food, like hot meat, so we’ve been guided by the classical sources. Then, suddenly, there is this one bar that is definitely serving hot food. And is it the only bar in the Roman world to have done this? Unlikely. So that is huge.” A new story appears to be emerging from the lapilli: of a cunning bar owner who reckons that an authority from distant Rome isn’t likely to shut down his operation, or who is confident that the local authorities—the kind of Pompeiians who live in grand houses—will turn a blind eye to an illegal takeout business that keeps their less affluent neighbors fed with cheap but tasty fish-and-snail soup.

A decade or so ago, a different story about the walls of Pompeii prevailed—that they were crumbling from neglect and from the ineptitude of the site’s custodians. In late 2010, a stone building known as the House of the Gladiators imploded after heavy rains, severely damaging valuable frescoes inside. That disaster was followed by the collapse elsewhere in the city of several other walls. The media responded with a wave of alarmed stories; a typical headline, from National Geographic, asked, “pompeii is crumbling—can it be saved?” Italy’s President at the time, Giorgio Napolitano, declared the condition of Pompeii “a shame for Italy.” Pompeii was also afflicted with human corruption, with the Camorra—the Neapolitan Mafia—exerting influence over its custodial ranks and on the local businesses that catered to the 2.3 million tourists who visited annually. In 2012, the European Union intervened, underwriting the Great Pompeii Project, which offered a hundred and forty million dollars to Pompeii for conservation and restoration.

Despite this narrative of decline—much of which presumed that Italy was unwilling, or unable, to take care of its greatest asset, its cultural patrimony—the deterioration at Pompeii was inevitable. In some instances, what had given way and caused walls to crumble were not bricks laid by ancient Romans but concrete restorations carried out after the Second World War, during which Pompeii was assaulted by Allied forces who mistook corrugated-metal roofs covering excavation sites for Nazi barracks. Mary Beard, a professor at Cambridge University who is among the Anglophone world’s best-known interpreters of Roman history, told me, “The fate of Pompeii is quite mythologized, and has become a shorthand symbol for lots of other issues in heritage management. The P.R. used to be ‘Well, we can’t even keep Pompeii up, the place is falling down, it’s a terrible disgrace.’ Of course the place is falling down—it’s a ruin. There are totally unreasonable expectations of what Pompeii can be, and how it can be preserved.”

In 2014, the archeologist Massimo Osanna was appointed director of Pompeii, and he immediately launched an effort to restore confidence in the future of the ancient past. Sophie Hay told me, “I went to Pompeii shortly after Osanna got the job, and after five minutes on the site with him I got the idea of where he was going. He walked down the main street, the Via dell’Abbondanza, and there was all this horrible plastic netting in the doorways of buildings, the sort used on building sites to keep people out.” The site looked bandaged and bruised. “He was absolutely horrified—he called people over who were working there and said, ‘Can’t we just remove all of this?’ ” Osanna made Pompeii more inviting to visitors, and by 2019 their numbers had swollen to four million annually. That year, the House of the Gladiators reopened to the public after a reconstruction of its damaged frescoes, becoming a symbol not of Pompeii’s decline but of its renewed vitality.

Meanwhile, the charismatic Osanna won over the press by trumpeting discoveries resulting from the restoration work in Regio V. “He was absolutely brilliant at it,” Beard told me. “Without actually doing any major excavation, he gave a series of carefully timed bits of good news.” A headless male skeleton was discovered at a crossroads next to the House of the Silver Wedding, as was a huge block of stone, which lay, almost cartoonishly, right where the skull should have been. (The gruesome suggestion that the man had been decapitated was overturned by later analysis, which suggested that he had been suffocated by the pyroclastic flow—superheated rock, ash, and gases that rushed down Vesuvius’s flank.) In a house that had been buried beneath a swath of rough land, a fresco depicting the god Priapus weighing his oversized member on a scale was uncovered. The press hailed the new discoveries, and in 2020 Osanna was named director general of Italy’s state-run museums.

One day during my visit to Pompeii, I was wandering alone when I came upon the house with the Priapus, which is around the corner from the House of the Silver Wedding, on the Via del Vesuvio. The fresco of the erect god was in the entrance hall. Phallic imagery was common in Pompeii, and according to scholars such images were usually seen as symbols of good luck, rather than of ostentatious lewdness. It would have been interesting to know whether Priapus’ facial expression was one of pride or discomfort, but the fresco was missing the disk-shaped area where his head had once been. In a nearby room, a better-preserved painting depicted the mythical story of Leda and the Swan, in which Zeus assumes the form of a bird and copulates with a Spartan queen. After archeologists discovered the painting, in late 2018, and peeled back its curtain of gray, crumbly lapilli with scalpels, Osanna unveiled it to the public by describing the “pronounced sensuality” of Leda, who, he declared, was “welcoming the swan into her lap.” Examining the painting, I decided that Leda could just as easily be said to have an expression of trepidation, even panic.

Archeologists have since excavated the room to which the painting belonged: a small, richly decorated chamber featuring wall panels festooned with floral motifs. The lower half of the walls were painted in the rich red color indelibly associated with Pompeii. This look is consistent with what historians have classified as the city’s Fourth Style, which was prevalent in the years immediately before the cataclysm. The décor—now nearly two thousand years old—had been freshly installed when the volcano exploded.

In 2019, archeologists realized that they had come upon a structure worthy of a full excavation: a thermopolium, or snack bar, replete with still vivid paintings and amphorae. Photograph by Patrick Zachmann/Magnum

Since the remains of Pompeii and the other ancient Roman settlements inundated by Vesuvius first came to light, some three hundred years ago, discovery has often gone hand in hand with destruction. An eighteenth-century visitor to the site of Herculaneum described the methods used by the workmen under the command of Roque Joachim Alcubierre, the artillery engineer who had been appointed to oversee the excavation by the Bourbon monarchy then ruling the Kingdom of Naples. Unlike Pompeii, Herculaneum was not blanketed with ash and pumice; it was buried only by a series of pyroclastic flows, which hardened into a layer of deep rock, through which workmen could dig narrow tunnels only with great difficulty.

The workmen of that era, upon finding a mansion or other building, would extract any objects of obvious value, such as marble statues, bronze lamps, and decorative mosaics, without taking note of their location or of the architectural context. Because of the treacherous conditions—among them, inadequate light and air—workmen did not trouble to excavate doors. They broke through walls to get from one room to another, regardless of what decorations in the adjoining room they might be destroying. At Pompeii, it is not uncommon to see a wall with a hole smashed through it, including the wall perpendicular to the Leda and the Swan, where another painting has been partially destroyed—the handiwork of heedless laborers in centuries past, who dug down and rooted around through the ash and lapilli, which is shallower and easier to penetrate than the rock of Herculaneum.

Alcubierre operated with barbaric efficiency, especially when it came to wall paintings that his workers hacked off from their brick underpinnings. When a painting was deemed insufficiently different from those already unearthed, workmen pulverized it underground. These excavations were focussed on finding masterpieces to augment royal or aristocratic collections, rather than on discovering the mundane objects of everyday life—or material evidence of the complexities of Roman social structures. Today’s archeologists are happy to retrieve beautiful objects, but they are also intent on finding clues that will help them better understand how slavery functioned in the Roman world, or how women could acquire power.

Even the best-intentioned archeologists are only as good as their methodologies, and the primitive approaches of eighteenth-century pioneers are sometimes enough to make a modern observer shudder. In the seventeen-fifties, a large villa near Herculaneum was discovered, and archeologists were so transfixed by its handsome courtyards and garden that they barely registered the lumps of blackened charcoal that workmen were tossing aside. Many had crumbled before the lumps were belatedly identified as charred scrolls of papyrus. Did they record any lost works of antiquity? The first efforts to render the scrolls legible—by soaking them in mercury, or dunking them in boiling water—resulted in the scrolls turning to dust or mush. In a potent example of the advantage of waiting a few hundred years for technological advances to occur, scientists are now hoping to develop techniques for reading carbonized scrolls virtually, using microscopic-imaging tools devised for use in the drug and chemical industries.

Archeological techniques became more sophisticated in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and at Pompeii there was a breathtaking innovation. Preserved in the compacted ash were numerous oddly shaped holes, and artisans made plaster casts of these cavities, thereby creating vivid representations of the city’s residents in their final moments: writhing helplessly on the ground, seeking to protect a loved one from the rain of ash. But Pompeii’s rising popularity as a tourist destination paradoxically contributed to the site’s erasure. Charles Dickens, who visited in 1844, writes, in “Little Dorrit,” about a family of tourists who made off with pocketed fragments—“morsels of tessellated pavement . . . like petrified minced veal.”

Less than a century after Dickens’s visit, much of the buried city had been unearthed, largely under the watch of Amedeo Maiuri, Pompeii’s director from 1924 to 1961. At the bidding of Mussolini, who sought to connect the grandeur of ancient Rome with the triumphs of contemporary Italy, Maiuri significantly accelerated the pace of excavation, exhuming residential areas of the city, and also the buildings that lined the Via dell’Abbondanza. The scale of activity made it hard to protect the site from weeds and looters. But experts praise Maiuri for having a scholarly interest not only in grand houses but also in the simpler structures—workshops, brothels, public latrines—that have increasingly become a focus of Pompeii scholars.

About a third of Pompeii has yet to be excavated; the consensus among scholars is that this remainder should be left for future archeologists, and their presumably more sophisticated technologies. Photograph by Patrick Zachmann/Magnum

Astonishingly, the new excavations in Regio V have prompted historians to reconsider one of the fundamental facts they thought they knew about Pompeii: the date of the eruption. In Pliny the Younger’s first-person account, he writes that the disaster occurred on August 24th. But, in a house down the street from the newly discovered thermopolium, archeologists have found a wall bearing the charcoal inscription of a date: the Roman equivalent of October 17th. Though the inscription doesn’t include a year, many scholars suspect that it dates from 79 A.D. Paul Roberts, a Pompeii scholar at the Ashmolean Museum, at Oxford University, told me, “Charcoal doesn’t tend to hang around too long. I am quite convinced that this was put on the wall not long before it was buried.” The inscription backs up a theory that another former director of Pompeii, Grete Stefani, proposed in 2006: that the correct eruption date was late October. Stefani based her argument on an array of archeological evidence, including the discovery of fruit that would have been out of season in August.

The charcoal marking is in a newly excavated residence that has been named the House of the Garden, because it once featured a lovely, verdant courtyard surrounded by a low wall decorated with images of plants. I visited it not long before the site closed for the day, when the declining sun was casting slanted light over Pompeii’s largely emptied streets, tinting the clouds beyond Vesuvius a gorgeous gold-pink. The inscription, at eye level on a wall, had a makeshift shield propped in front of it, protecting it from light damage. When a custodian removed the shield to show me the writing, I found it both indecipherable and disconcertingly familiar—it was the jotting of someone keeping track of housekeeping, just as I might use a whiteboard calendar to note a forthcoming appointment with the dentist.

The other rooms of the mansion were sumptuous, especially one in which a round fresco of a woman’s face—handsome, with deep-set eyes and a long, straight nose—looked out from a wall. Perhaps it was a portrait of the lady of the house. During the excavation of the mansion, a horrifying scene had been found: the skeletons of men, women, and children who had sought refuge in an inner room of the house, trying to shield themselves from the ash, the heat, and the gases spewed by the volcano. In the same building, archeologists discovered a box filled with amulets: figurines, phalluses, and engraved beads. In announcing the find, Massimo Osanna, ever the showman, had called it a “sorcerers’ treasure trove,” noting that the items contained no gold and therefore might have belonged to a servant or an enslaved person. Such items were commonly associated with women, Osanna had noted, and might have been worn as charms against bad luck.

Other scholars have warned that the suggestion of a sorcerer, or sorceress, verges on embellishment, given the paucity of material evidence. The contents of the box are now displayed in the Pompeii museum, with no mention of a sorcerer in the accompanying text. Yet, as the daylight dwindled in Pompeii, it was tempting to follow Osanna’s lead and imagine the scene: terrified members of the household clutching one another, their social differences levelled by disaster, as a Pompeiian who believed in dark magic made unavailing imprecations against unrelenting gods. My mystical vision evaporated, however, after the mansion’s custodian showed me another inscription, which had been scratched into the lintel of the house’s external doorway. It read “Leporis fellas”: “Leporis sucks dick.”

When Zuchtriegel, the current Pompeii director, was overseeing the site at Paestum, where three Greek temples have stood since the fifth and sixth centuries B.C., he made a number of innovations. Visitors were invited to watch ongoing excavations, and the storerooms inside the site’s museum were opened for public perusal.

Zuchtriegel told me that, in his leadership role at Pompeii, he intends to continue embracing new approaches. As we walked along the Via Stabiana, with its narrow, elevated sidewalks that helped Pompeii’s residents skirt the muck of its streets, he emphasized that archeology “is a field that is very much evolving, thanks to new discoveries and methodologies, but also thanks to new questions.” He went on, “Today, we have a much broader view of ancient society. Archeology started as a field dominated by male, upper-class, European, white scholars, and noblemen and connoisseurs, and this very much conditioned archeological research, and what people were interested in. Now, thanks to new perspectives—post-colonial studies, and gender studies, and feminism—we have a really different perspective on antiquity.”

Among the discoveries being examined through these new interpretative lenses was the first significant find announced under Zuchtriegel’s tenure: the remains of a man identified as Marcus Venerius Secundio. The tomb was found not in Regio V but east of Pompeii, where a necropolis had been unearthed close to one of the city gates. Unusually for an adult burial, the deceased had been embalmed rather than cremated, and the body was so well preserved that hair and even part of an ear were intact.

Secundio, Zuchtriegel explained, was a freedman, having formerly been a public slave—essentially, a municipal worker owned by the city. “Of course, nobody wanted to be a slave—it was very humiliating to be the property of someone,” Zuchtriegel said. “On the other hand, if you were a very poor freedman you were less well off than a household slave, some of whom were educators of the children of rich people, or secretaries who were part of the team that carried on the business of the owner.” It is unknown how Secundio gained his freedom, but historical records indicate that a public slave could raise funds to buy himself out of servitude. Evidently, Secundio ascended within Pompeiian society, becoming an augustalis, or a priest in the imperial cult—one of the few high-ranking positions open to men who were not freeborn. According to the funerary inscription on his tomb, Secundio was a patron of the arts, paying for ludi—musical or theatrical events that were performed in Latin and, significantly, in Greek. “This is the first time we have this direct evidence of Greek plays in Pompeii,” Zuchtriegel told me. Scholars had hypothesized, based on evidence in wall paintings and graffiti, that such events took place, but the inscription provides exciting confirmation.

In the decades before the eruption of Vesuvius, Zuchtriegel went on, there was a fashion in the Roman Empire for Greek-language performance, which was established by the emperor Nero, who ruled from 54 to 68 A.D., and who fancied himself not just an aficionado of Greek drama and song but also a performer. (According to the historian Suetonius, Nero “made his début” as a singer in Naples, so enjoying himself onstage that he ignored the rumblings of an earthquake in order to finish his performance.) Nero’s reputation as a tyrant has lately been reconsidered by scholars, and the evidence of Greek-language ludi in Pompeii buttresses the revised image of the Emperor as a popular leader; it also underscores the extent to which even a provincial city like Pompeii was influenced by the cultural fashions of the capital. “Pompeii and Campania had this really multicultural environment,” Zuchtriegel said. “People came from the Eastern Mediterranean, and there were the old Greek colonies at Naples and Paestum. We have evidence of Jewish people here at Pompeii.” (Graffiti found in the city cite individuals with the names Sarah, Martha, and Ephraim.)

Zuchtriegel told me that, as director, he intended to build on Osanna’s work, a decade after the rescue operation of the Great Pompeii Project was initiated. Other damaged fringes of Regio V are to be shored up, and new, limited excavations are to take place in another district, Regio IX. Similarly, work is continuing to protect areas outside the gates of Pompeii which have remained vulnerable to the incursion of illegal diggers. Scholars have made various new discoveries in these outlying areas, such as the remains of a horse that died during the eruption; the cavity formed in the rubble by the horse’s body has now been cast in plaster. Earlier this month, Zuchtriegel announced the discovery of slave quarters: a humble room, equipped with three wooden beds and amphorae stacked in a corner. “It is certainly one of the most exciting discoveries during my life as an archeologist, even without the presence of great ‘treasures,’ ” Zuchtriegel said. “The true treasure here is the human experience, in this case of the most vulnerable members of ancient society.”

But Zuchtriegel is likely to be less hyperbolic in his promotion than Osanna sometimes sought to be. I asked him how he could make preservation as exciting as discovery. He paused, then said, “Well, it doesn’t have to be so exciting. But we have to do it, anyway. I think what Massimo showed in these years is that excavation, research, and preservation are not opposites. As we see with the thermopolium, this was an excavation that had as a primary goal to preserve the conservation of the site.” He went on, “It’s very important to explain that archeology is very complex—from the excavation to the restoration to the exhibition, analysis, publication, and study. It’s important to make this transparent, and share it with the public, so that people understand that archeology is not about treasures and precious objects—that’s only a small part. It’s really about reconstructing the life of people in the distant past.”

Zuchtriegel and I wandered over to a section of the city that was closed to visitors. A custodian holding a bunch of keys seemed on the verge of warning us off when he recognized his relatively new boss. We then entered another of Pompeii’s grand mansions, the house of Maximus Obellius Firmus, one of the city’s most prominent citizens in the period before the eruption. This mansion also demonstrated the Pompeiian fascination with Greek culture, Zuchtriegel explained. An interior garden was surrounded by a peristyle—a rectangular perimeter of covered columns—which was popular in classical Greece. “There is an attempt to transform a traditional Roman house into a Greek space,” Zuchtriegel said. “You could be here in the middle of Pompeii, and feel like you were in a different space.”

He encouraged me to look upward. A restored rafter was serving as a perch for a few pigeons, whose droppings are especially damaging to wall paintings and stucco. Zuchtriegel had introduced a program whereby trained hawks sweep the ruins, frightening off the pigeons. “I did the same in Paestum,” he said. “You can reduce the pigeon population by eighty-five to ninety per cent!”

One of the challenges facing any director of Pompeii is coping with the tourists who flock, like pigeons, to explore the ruins. As Italy reopens for both domestic and international tourism, crowds are again lining up to enter Pompeii’s more celebrated locations, including the street-corner brothel in which partitioned chambers equipped with masonry beds are decorated with obscene wall paintings—an X-rated version of the dead ducks painted on the counter of the thermopolium in Regio V. A feminist interpretation of the practice of sex work, and its role in Pompeiian society, has not yet been incorporated at the site. An official guide who showed me around the city one day regaled me uncritically with the anecdote, found in the satires of the poet Juvenal, that Messalina, the wife of the emperor Claudius, liked to moonlight in a brothel—a story that Mary Beard and other contemporary critics view with a witheringly skeptical eye.

Counterintuitively, one of Zuchtriegel’s goals as director of Pompeii is to persuade visitors to go elsewhere—to the ruins of Herculaneum and to other, smaller sites that lie in the shadow of Vesuvius. One day, I got off the Circumvesuviana at Torre Annunziata Oplonti, and walked from the station for ten minutes through the town’s steep, scruffy streets to reach a site known as the Villa Poppaea—once a luxurious suburban domicile with views of the islands of Ischia and Capri. The villa gets its name from Nero’s second wife, Poppaea Sabina, whose family is believed to have come from Pompeii; it is thought to have been her country residence.

The site had just opened for the day, and I had it to myself as I descended to the 79 A.D. level and walked through a garden, where what looked like carbonized tree stumps remained in the ground. The villa, a sprawling complex of reception rooms and gardens and walkways which dates to the first century B.C., was stunning. First rediscovered at the end of the fifteenth century, when engineers were digging a canal, it was partially excavated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, then more fully exposed in the late twentieth century. Archeologists cleared away pumice and ash, and in rooms edging a garden they uncovered magnificent frescoes of the birds and plants that appear to have once flourished there. A large, decorated peristyle surrounded another garden: Greek-style living at its finest.

For all the interest offered by the new discoveries of the modes of everyday living at Pompeii—with its snail stews and its Greek theatrics—an empty, unfamiliar, luxurious villa retains an irresistible allure. The grandeur of the Villa Poppaea brought to mind images of an élite class of individuals who thought themselves safely removed from the grubbing hardships endured by the poor, but whose vast wealth provided them with no protection from a titanic natural disaster. At the eastern perimeter of the site, there was a feature to stir the envy of a Silicon Valley plutocrat: a swimming pool more than sixty metres in length. It was filled with weeds and gravel now, but in 79 A.D. it would have been edged by lavishly decorated salons and gardens—and it was easy to imagine Roman aristocrats lounging around a glittering pool, gazing across the sea with the dormant mountain at their backs, confident that the world was—and always would be—theirs to enjoy. ♦

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

10/24: The tragic day of the Roman Empire

This is one of the letters that the writer Pliny the Younger, an eyewitness to the eruption of Vesuvius in the year 79, wrote to the historian Tacitus. In this letter he recounts in astonishing detail the tragedy as well as the death of his uncle Pliny the Elder.

Remember that there was an error in the translation of the date. Now we know it was October 24.

The ninth day before the Kalends of September (August 24), in the early afternoon, my mother drew to my uncle’s attention a cloud of unusual size and appearance. Its general appearance can best be expressed as being like an umbrella pine, for it rose to a great height on a sort of trunk and then split off into branches, I imagine because it was thrust upwards by the first blast then left unsupported as the pressure subsided, or else it was borne down by its own weight so that it spread out and gradually dispersed.

My uncle hurried to the place steering his course straight for the danger zone. Ashes were already falling, hotter and thicker as the ships drew near, followed by bits of pumice and blackened stones, charred and cracked by the flames. For a moment my uncle wondered whether to turn back, but when the helmsman advised this, he refused and decided to go to Stabia, to the house of his friend Pomponianus.

After his bath he lay down and dined; he was quite cheerful, or at any rate he pretended he was, which was no less courageous.

Meanwhile on Vesuvius, in various places, very wide flames and high fires shone, whose brightness stood out in the darkness of the night. My uncle, to excuse his fear, said that they were bonfires made by fugitive peasants or abandoned villas that were burning. Then he went to sleep and indeed he slept soundly, for his snoring was heard by those who were on guard at the gate. But the courtyard through which the room was reached began to fill up with ashes and rocks in such a way that if they had stayed there, they would not have been able to get out.

He awoke and rejoined Pomponianus and the others who had been keeping watch. They debated whether they would stay under cover or if they went out into the open, for the building was shaking with frequent long tremors and its foundations seemed to shift from one side to the other. However, if they went out into the open, the rains of boulders were to be feared, although more bearable.

Having compared both dangers, the second solution was chosen: in my uncle this constituted the triumph of reason over reason, in others, fear over fear. They put pillows on their heads, fastened with rags, the only protection against what fell. Elsewhere it was already dawn; there was a night blacker and denser than all nights, broken only by torches and various lights.

My uncle thought it appropriate to go to the beach and see what possibilities there were in the sea, which was deserted and adverse. There he lay down on a canvas and asked for cool water, which he drank twice;The others were flee by the smell of sulfur, the precursor of the flames. My uncle rose to his feet with the support of two serfs, but immediately fell down because, I think, the hazy mist choked his breath and closed his trachea, which was very delicate.

And the ashes came to Misenum, but at first sparsely. Behind us an ominous thick smoke, spreading over the earth like a flood, followed us. We had scarcely agreed what to do when we were enveloped in night. To be heard were only the shrill cries of women, the wailing of children, the shouting of men. But the darkness lightened, and then like smoke the cloud dissolved away. Everything appeared changed - covered by a thick layer of ashes like an abundant snowfall.

When it was daylight again, my uncle's body was found intact and just as he was dressed; he seemed asleep rather than dead.

These types of volcanic eruptions -explosive ones that expel pyroclastic flows instead of lava - are known as plinian eruptions after Pliny the Younger, the first in history to document this.

Pliny the Elder was a renowned writer and researcher of natural phenomena Pliny settled with his family in Misenum, on the Gulf of Naples, when Vespasian appointed him as commander of Roman navy.

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tired secretary

Herpein (or Fallen) was secretary of Pliny the Elder, when he was at Misenum (city near Pompeii). Pliny was known for his long studies when he needed his secretarians for writing notes and those secretarians (mostly his personal slaves) regulary falls asleep during his night studies.

I can image how was Fallen exhausted when he was helping with his studies. So tired and so out of shape.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

..

#beach#coast#mediterranean sea#bay of naples#misenum#traveling#strand#original photography#travel#reise#vacation#küste#travelling#reisen#sand beach#sandstrand#gulf of naples#golf von neapel#summer#sommer#sea#meer#waves#wellen#weekend#wochenende#italian#sand#mediterranean#mediterran

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

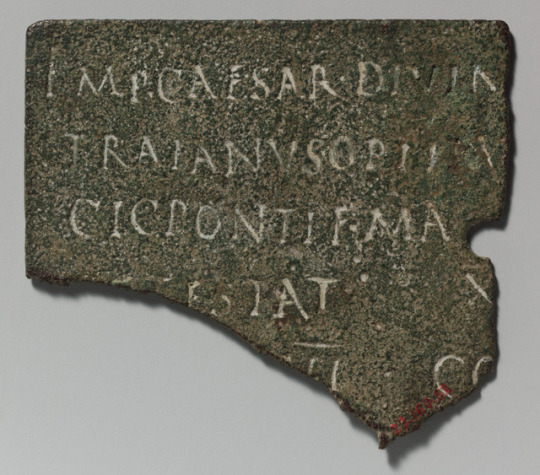

~ Bronze military diploma fragment.

Period: Mid-Imperial, Trajanic

Date: A.D. 113/14

Culture: Roman

Medium: Bronze

• From the source: These discharge papers were issued by the Emperor Trajan to sailors on a warship, a quadrireme, in the imperial fleet based in Misenum on the Bay of Naples. The ship may have formed part of the flotilla that escorted the emperor from Italy to the East for the Parthian War (A.D. 114–117).

#ancient#ancient art#ancient writing#bronze military diploma fragment#bronze#military#diploma#roman#trajanic#mid-imperial#discharge papers#war#warship#trajan#sailors#parthian war#misenum#naples#italy#a.d. 113#a.d. 114

180 notes

·

View notes