#aaw 2019

Note

Idk if ASAW will still be going on when this is posted, but I was scrolling through the aromantic tag and I'm so confused by how many people are calling it Aromantic Awareness Week / AAW????

Like granted it's a minority that and I /know/ learning new terms can be really hard for some people, but I remember when I first learned about ASAW back in… I think 2018 or 2019 it was very much talked about and explained to those who asked; That Aromantic Spectrum Awareness Week was much preferred and was trying to become the new default because arospec who weren't the aro version of "black stripe aces" feeling left out and dismissed during our week. So well I assume it's probably mainly just people who didn't know that, I can't help but feel like it aromantics specifically trying to exclude arospec folks as I saw that happening way to much in the past to trust it suddenly died out and everyone who used Aromantic Awareness Week in their posts aren't exclusionists. This kinda turned into a half vent half history lesson lol, but I was not expecting to see AAW used especially more then I personally saw even last year.

Submitted February 21, 2023

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Cupcakes Joe, Centipede Orel,Slender Doughy and Annebelle Christina (i think thats her name?its been a sec-) go to the movies and can't stop arguing about what to watch

Omg they would-

“Alright, we’re here now we gotta pick a movie” doughy said as the group as they made it to the ticket booth

“I wanna watch raw” Joe said

“We can’t watch raw, Joe that’s a netflix original. And it sucks” Christina said, scoffing.

“whatever cHrIsTaBeLlE you wouldn’t know quality cinema if it slapped you in your plastic face” Joe retorted, pointing out the fact that Christina was a literal doll

“I think we should see-

“OH MY GOD SHUT THE FUCK UP OREL WE’RE NOT WATCHING HUMAN CENTIPEDE. NOBODY FUCKING LIKES YOU” Joe and Christina shouted in unison, cutting him off and ignoring their previous argument

“oh my- can we please stop fighting and just pick a fucking movie?” Doughy asked, obviously annoyed

“Can you please go to the back of the line if you can’t pick a movie?” The dude behind the glass of the booth asked

“I will rip your organs out and feed them to your family” Joe threatened

“ok- ok- please don’t kill me” the guy behind the booth said

“well anyways, I say we watch that new Chucky movie?” Christina said

“Christina that’s from 2019 you fucking ignoramus” Orel said, narrowing his eyes

“I’m going to commit several murders if you don’t fucking pick a movie already” Doughy said

“we could see Barbie” Joe said

“that’s not fucking out yet you clod” Orel said

“YOU KNOW WHAT? WE’RE NOT SEEING A MOVIE ANYMORE NOPE WE’RE JUST GONNA HOME” Doughy snapped

“aaw man” Joe said “I really wanted to see a movie”

“WELL YOU FUCKERS RUINED IT” doughy yelled

“you suck” Orel said as they all left the theater parking lot

“You’re the one who called me an ignoramus you bitch” Christina said

“Whatever”

#moral orel x human centipede#moral orel x cupcakes#moral orel x slenderman#moral orel x the conjuring#this was really fun to write lol

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

(AAW 'Windy City Classic XV' - Dec. 28, 2019)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Program for African American Women

Part I: Diagnosis

Mission Statement

To reduce the prevalence of cardiovascular disease among low- to middle-income African American women aged 35-50 years old living in the south-central Houston area by providing education regarding physical and mental health and their impacts on cardiovascular disease risk factors.

Cardiovascular Disease Among African American Women

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death for men and women in the United States, and there is a disproportionate burden of CVD seen in minority populations (Saban, Tell, & Janusek, 2019). African-American women (AAW) have the highest CVD rates in comparison to other ethnicities and genders. Compared to a prevalence of 36.1% in non-Hispanic white women, the prevalence of CVD in AAW was 48.3% in 2012 (Braun, Wilbur, Buchholz, Schoeny, Miller, Fogg, Volgman, & McDevitt, 2016). Moreover, cardiovascular health disparities among AAW are not fully explained by traditional risk factors (Saban et al., 2019). AAW experience additional CVD risk factors not experienced by men or women of other ethnic groups. Firstly, AAW have the highest rates for many CVD risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and physical inactivity (Ebong & Breathett, 2020). The article by Ebong & Breathett (2020) list many characteristics about AWW. They found that AAW are the least likely group to participate in physical activity, and the majority of AAW do not eat their recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables. They write that the reason for this is likely a result of deep-rooted, constant institutional and cultural oppression. In addition to the systemic formulation of racially segregated environments, AAW often live in areas with limited access to resources, limited educational opportunities, inadequate and/or unaffordable housing, high crime rates, and limited access to and/or prejudicial health care services. These circumstances experienced uniquely by AAW facilitates health behaviors associated with the development of CVD. Secondly, AAW are more likely to be affected by psychosocial risk factors than women of other ethnic groups (Copeland, Newhill, Foster, Braxter, Doswell, Lewis, & Eack, 2017). Many AAW must cope with chronic life stressors associated with racism and discrimination. In the study by Copeland et al. (2017), the authors write that the negative emotional response precipitated from such stressors elevates cortisol, adrenaline, and epinephrine levels, and overall heightens cardiovascular activity. Chronically, this physiological response increases the chances of developing CVD.

Because the traditional risk factors for CVD do not explain the health disparities seen in AAW, researchers have been looking into the connection between mental health status and CVD. Studies have found that individuals suffering from depression are 50% more likely to develop CVD, and AAW report symptoms of depression at higher rates in comparison to their White counterparts (Copeland et al., 2017). A possible explanation for this is the systemic disadvantages experienced by AAW and their resulting effects on mental health. Psychosocial stressors affect minority populations at a greater rate, especially African Americans. Remaining in a constant fight-or-flight mode physiologically can lead to an accumulation of visceral fat, high blood pressure, and hyperglycemia (Sims, Glover, Gebreab, & Spruill, 2020). Researchers also suggest AAW’s poor health behaviors may be a coping response to psychosocial stressors (Sims et al., 2020). This would explain the higher rates of diabetes, obesity, and hypertension among AAW. As stated by Copeland et al. (2017), the aforementioned bio-psycho-social factors that contribute to the poor mental health outcomes of AAW are collectively recognized as the ‘triple jeopardy’ of being African American, female, and impoverished.

Fortunately, researchers have found a connection between positive mental outlooks and lower CVD risks. Some studies show it is possible to reduce CVD risk when mental health issues are addressed. The study by Saban et al. (2019) found that resiliency can reduce the effect social stressors have on an individual’s risk of developing CVD and can improve risk factors. They write that higher resilience is seen to reduce the activation of stress response hormones and improve the physiologic response to stress. Another psychological attribute being studied associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes is gratitude. Evidence demonstrates that dispositional gratitude can actually foster protective factors against depression and improves the effect psychosocial stressors have on the body (Cousin, Redwine, Bricker, Kip, & Buck, 2020). Strengthening an individual’s sense of gratitude and spirituality is a possible way to improve AAW cardiovascular health.

Why This is a Problem

First and foremost, this is a public health problem because the observed disparities are a result of sociocultural risk factors that are otherwise completely preventable. Primary prevention practices, such as visiting a doctor and getting regular health screenings, should be a priority for this population, but evidence shows African Americans are less likely to participate in routine medical checkups compared to White Americans (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003). AAW who seek healthcare to improve their CVD risk factors often run into the same racial and discriminatory exposures within the health care system that they do in other areas of society. To make matters worse, the strongest evidence for the existence of racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare is found in studies of cardiovascular care, as noted by Smedley et al. (2003). Among their discoveries, researchers found that there is an underuse of treatment services amid racial and ethnic minorities. This either suggests that physicians are less likely to offer treatment services to minority patients, or minority patients are more likely to refuse treatment services. They also find that there is evidence supporting the theory that the race of a patient influences physicians’ decisions regarding diagnosis and treatment recommendations. In one study, physicians rated African American patients as least intelligent, more likely to abuse drugs/alcohol, and more likely to fail to comply with and participate in treatment protocols. AAW that seek to improve their cardiovascular health may be essentially deemed not worthy enough due to a physician’s implicit negative racial stereotype. Though physicians may be acting on their implicit biases, but AAW are still being negatively affected.

Additionally, there is a legacy of distrust among healthcare providers and racial minorities in America that may make AAW less likely to accept healthcare services and/or procedures. In the same study by Smedley et al. (2003), evidence suggests minority patients may be more receptive and trusting of physicians who are minorities themselves. However, minority physicians represent only 9% of the physicians in the country; of the 9%, one-third is African-American. AAW who have perceived discrimination from White physicians are less likely to seek health care and are even less likely to find a healthcare provider they feel they can trust. This could be the reason AAW are more likely to avoid healthcare services altogether.

Existing Programs

Successful Programs

AAW are more likely to have multiple CVD risk factors at one time, so interventions that target multiple risk factors are necessary for success (Ebong & Breathett, 2020). The Love Your Heart program was a 12-week nutrition and physical activity intervention that aimed to reduce cardiovascular risk factors among African American women living in the Boston area (Rodriguez, Christopher, Johnson, Wang, & Foody, 2012). This program was culturally tailored for African American women, and it used a self-help group methodology to address the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects that affect weight and cardiovascular health. The intervention included fitness classes, educational sessions spotlighting the importance of nutrition and exercise on CVD, group meetings and discussions, and personalized wellness plans. The results of the study found significant improvements in CVD risk factors. Comparing the pre-and post-test data, participants reduced their systolic blood pressure, body-mass-index, body weight, and waist circumference. This program highlights the effectiveness of community-based interventions that combine health information, individual support, and group support to lower CVD risk.

Another successful program, Prime Time Sister Circles, was a 10-week health program that aimed to improve diet and increase physical activity among African American women aged >35 years across the country (Gaston, Porter, & Thomas, 2007). It utilized the Social Cognitive Theory and Transtheoretical Model for program creation. The intervention was a curriculum-based approach to behavioral change and incorporated a support group appeal. The groups met once a week for 10 weeks and received information about spirituality, self-esteem, self-care, nutrition, exercise, CVD, and diabetes. This program is unique in that it also targeted stress-relief strategies. The results of the study found improvements in the participants self-reported stress management, physical activity, and nutrition. Data also shows that the program improved participants knowledge of CVD risk factors and attitudes towards prioritizing their health. This study is yet another that emphasizes the value culturally tailored interventions in support group settings have on reducing CVD risk in African American women.

Unsuccessful Programs

STEPS (Sisters Together Empowered for Prevention and Success) to a Healthier Heart was a 12- week, quasi-experimental, pre-posttest educational intervention that targeted AAW between 35 and 65 years of age (Brown, Alexander, Cummins, Price, & Anderson-Booker, 2018). The purpose of this health program was to assess if AAW’s general knowledge about risk factors of heart disease improved with participation in informational and physical activity sessions. The women chose to participate in either the intervention group, which involved information and physical activity sessions, or the comparison group, which received an informational packet only. The Coronary Heart Disease Knowledge Test was used to assess each participant’s knowledge of heart disease risk factors. This program was ultimately unsuccessful because, in comparing the pre- and posttest data, no significant changes occurred and there were no between-group differences. One possible reason this program was unsuccessful could be due to the use of standard surveys, and future studies should use a more reliable and valid measurement to assess knowledge among AAW. Another possibility is due to the intervention’s short duration with little attention on physical activity. This program underscores the importance of multicomponent, culturally tailored interventions that address multiple risk factors for AAW for success.

Part II: Planning

Program Goals and Objectives

Program Goal Number 1

Reduce the impact psychosocial stressors have on the priority population’s CVD risk.

Project Objective

By December 2021, when comparing pre-post test scores, one-half of the participants will report lower general stress as measured by the general stress subscale of the Chronic Stress Questionnaire (CSQ).

Health Education Objectives

- By the end of the first trimester, the majority of the participants will be able to list three healthy and three unhealthy stress and anxiety relief practices.

- Upon completion of the program, one-half of the participants will be able to identify stressors associated with racism and discrimination and effective coping methods.

- Six months after completion of the program, one-half of the participants will be able to list at least one coping and/or stress management skill utilized daily.

Project Objective

By June 2022, one-fourth of participants will report higher levels of resilience, in comparison to pre-test scores, as measured by the Conner-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-25).

Health Education Objectives

- By the end of the second trimester, more than half of the participants will be able to identify factors that foster resilience.

- Upon completion of the program, one-fourth of the participants will be able to list three self-reflection practices.

Program Goal Number 2

Increase participation in physical activity and/or exercise that targets cardiac health among individuals in the priority population.

Project Objective

By June 2022, one-fourth of participants will engage in thirty minutes of moderate physical activity at least 3 times a week.

Health Education Objectives

- By the end of the first trimester, more than half of the participants will be able to identify three exercises that improve heart health.

- By the end of the first trimester, the majority of the participants will be able to identify three CVD risk factors associated with physical inactivity.

- One-half of the participants will be able to locate areas in the community with gyms and/or green space upon completion of the program.

Program Goal Number 3

Increase the awareness of primary and secondary prevention practices and their importance among individuals in the priority population.

Project Objective

By December 2023, yearly health care checkups among the participants will increase by 25%.

Health Education Objectives

- By the end of the second trimester, the majority of the participants will be able to identify two primary and two secondary prevention practices.

- By the end of the second trimester, the majority of the participants will be able to identify three CVD risk factors that are easily preventable by modifying behaviors.

- Upon completion of the program, one-third of the participants will be able to locate the nearest healthcare center in their community accessible to them.

- Upon completion of the program, one-fourth of the participants will be able to state the recommended schedule for healthcare screenings.

Theoretical Support of Intervention

Due to the high rates of depression seen among AAW, successful interventions must address both the physical and mental risk factors for CVD. The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) and the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) will both be used to guide the development of this program (McKenzie, Neiger, & Thackeray, 2013). According to McKenzie et al. (2013), the TTM posits that behavior change happens over time, and that people move through five distinct “stages of change” phases in the process of adopting a health behavior change. This model has been effective for a variety of health behavior changes because it considers that people may begin in different stages. Most individuals will not respond to action-oriented behavior change programs because the majority are not prepared to act. Specific principles are applied at specific stages to maximize efficacy and ensure individuals move forward to the next stage. In other words, individuals are matched with interventions depending on the stage they are in. The SCT posits that learning happens in a social context. Individual experiences, environmental factors, and the actions of others influence health behavior. An important component of the SCT is reinforcement. Theorists believe reinforcement is essential for learning. Moreover, reinforcement with the addition of an individual’s expectations of the outcome is what determines behavior.

The reason I chose to use two theories is because mental needs to be addressed at a personal level, however, past programs have shown that AAW respond to interventions best when group support and social interactions are given. I chose the TTM because it addresses each participant as individuals. Some AAW may fare better in the face of adversity than others, so the mental health status of the participants is going to vary. Additionally, though some participants will share the same barriers to action, others are going to have barriers no one else has. This is the best intrapersonal level theory to use for many reasons. Firstly, we can implement interventions that can best facilitate change based on the stage the participants are in. Interventions that require immediate action will lose the participants that are not ready for action. By allowing the participants to progress through the stages on their own time ensures maximum participants retention in the program. The second reason I chose this theory was because of how well the Processes of Change correlate to what our participants are likely to go through throughout the intervention. For example, after learning more about the psychosocial factors, participants may begin to notice each time they are subjected to toxic, negative emotions due to their environment, which is explained by the process of dramatic relief. This will accompany the realization of the effects it has on them and their environment, which is explained by the constructs of self- and environmental reevaluation. Further, the intervention’s aim of finding new ways to cope with stressors and fostering resiliency is explained by the construct of counterconditioning. Lastly, as explained by the construct of social liberation, being able to effectively cope with negative emotions can/will allow the participants to focus their attention on all the positive experiences they have.

To target the interpersonal level, I chose the SCT because it addresses the influence that observational learning has on behavior. As stated above, similar programs with the most success have included group support/meetings in the intervention. Participants credited their continued participation and enthusiasm to the relationships they created with others and the desire to help one another succeed. Seeing others succeed due to a behavior change influences others to adopt that change as well. I also chose this theory because it addresses the idea of monitoring and adjusting behavior to gain control over it. This is the best interpersonal level theory to use because of the emphasis it has on learning in social contexts. We already know AAW respond best with group support, and the SCT has roots in learning from and believing in others. AAW who may not feel confident in the behavior changes will be encouraged by seeing other women succeed, or they will be encouraged to try when they see the support other participants are giving them. For example, participants will gain knowledge and skills about how to eat healthy after learning about healthy dinner options, as explained by the construct of behavioral capability. When a participant shares their meal plan that they have been following, positive feedback and praise from program instructors and other participants will help to maintain that participant’s behavior change, which is explained by direct reinforcement. On the other hand, participants who are struggling with that same behavior change may be encouraged to work for it after seeing the commendation others receive, as explained by vicarious reinforcement. To maintain this behavior, the participant will have to monitor and adjust their behavior, which is explained by the construct of self-control. As their self-control increases and their healthy eating behavior is maintained, they will gain confidence in their ability to create meaningful change in their life, as explained by self-efficacy.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Program for African American Women

Part I: Diagnosis

Mission Statement

To reduce the prevalence of cardiovascular disease among low- to middle-income African American women aged 35-50 years old living in the south-central Houston area by providing education regarding physical and mental health and their impacts on cardiovascular disease risk factors.

Cardiovascular Disease Among African American Women

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death for men and women in the United States, and there is a disproportionate burden of CVD seen in minority populations (Saban, Tell, & Janusek, 2019). African-American women (AAW) have the highest CVD rates in comparison to other ethnicities and genders. Compared to a prevalence of 36.1% in non-Hispanic white women, the prevalence of CVD in AAW was 48.3% in 2012 (Braun, Wilbur, Buchholz, Schoeny, Miller, Fogg, Volgman, & McDevitt, 2016). Moreover, cardiovascular health disparities among AAW are not fully explained by traditional risk factors (Saban et al., 2019). AAW experience additional CVD risk factors not experienced by men or women of other ethnic groups. Firstly, AAW have the highest rates for many CVD risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and physical inactivity (Ebong & Breathett, 2020). The article by Ebong & Breathett (2020) list many characteristics about AWW. They found that AAW are the least likely group to participate in physical activity, and the majority of AAW do not eat their recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables. They write that the reason for this is likely a result of deep-rooted, constant institutional and cultural oppression. In addition to the systemic formulation of racially segregated environments, AAW often live in areas with limited access to resources, limited educational opportunities, inadequate and/or unaffordable housing, high crime rates, and limited access to and/or prejudicial health care services. These circumstances experienced uniquely by AAW facilitates health behaviors associated with the development of CVD. Secondly, AAW are more likely to be affected by psychosocial risk factors than women of other ethnic groups (Copeland, Newhill, Foster, Braxter, Doswell, Lewis, & Eack, 2017). Many AAW must cope with chronic life stressors associated with racism and discrimination. In the study by Copeland et al. (2017), the authors write that the negative emotional response precipitated from such stressors elevates cortisol, adrenaline, and epinephrine levels, and overall heightens cardiovascular activity. Chronically, this physiological response increases the chances of developing CVD.

Because the traditional risk factors for CVD do not explain the health disparities seen in AAW, researchers have been looking into the connection between mental health status and CVD. Studies have found that individuals suffering from depression are 50% more likely to develop CVD, and AAW report symptoms of depression at higher rates in comparison to their White counterparts (Copeland et al., 2017). A possible explanation for this is the systemic disadvantages experienced by AAW and their resulting effects on mental health. Psychosocial stressors affect minority populations at a greater rate, especially African Americans. Remaining in a constant fight-or-flight mode physiologically can lead to an accumulation of visceral fat, high blood pressure, and hyperglycemia (Sims, Glover, Gebreab, & Spruill, 2020). Researchers also suggest AAW’s poor health behaviors may be a coping response to psychosocial stressors (Sims et al., 2020). This would explain the higher rates of diabetes, obesity, and hypertension among AAW. As stated by Copeland et al. (2017), the aforementioned bio-psycho-social factors that contribute to the poor mental health outcomes of AAW are collectively recognized as the ‘triple jeopardy’ of being African American, female, and impoverished.

Fortunately, researchers have found a connection between positive mental outlooks and lower CVD risks. Some studies show it is possible to reduce CVD risk when mental health issues are addressed. The study by Saban et al. (2019) found that resiliency can reduce the effect social stressors have on an individual’s risk of developing CVD and can improve risk factors. They write that higher resilience is seen to reduce the activation of stress response hormones and improve the physiologic response to stress. Another psychological attribute being studied associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes is gratitude. Evidence demonstrates that dispositional gratitude can actually foster protective factors against depression and improves the effect psychosocial stressors have on the body (Cousin, Redwine, Bricker, Kip, & Buck, 2020). Strengthening an individual’s sense of gratitude and spirituality is a possible way to improve AAW cardiovascular health.

Why This is a Problem

First and foremost, this is a public health problem because the observed disparities are a result of sociocultural risk factors that are otherwise completely preventable. Primary prevention practices, such as visiting a doctor and getting regular health screenings, should be a priority for this population, but evidence shows African Americans are less likely to participate in routine medical checkups compared to White Americans (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003). AAW who seek healthcare to improve their CVD risk factors often run into the same racial and discriminatory exposures within the health care system that they do in other areas of society. To make matters worse, the strongest evidence for the existence of racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare is found in studies of cardiovascular care, as noted by Smedley et al. (2003). Among their discoveries, researchers found that there is an underuse of treatment services amid racial and ethnic minorities. This either suggests that physicians are less likely to offer treatment services to minority patients, or minority patients are more likely to refuse treatment services. They also find that there is evidence supporting the theory that the race of a patient influences physicians’ decisions regarding diagnosis and treatment recommendations. In one study, physicians rated African American patients as least intelligent, more likely to abuse drugs/alcohol, and more likely to fail to comply with and participate in treatment protocols. AAW that seek to improve their cardiovascular health may be essentially deemed not worthy enough due to a physician’s implicit negative racial stereotype. Though physicians may be acting on their implicit biases, but AAW are still being negatively affected.

Additionally, there is a legacy of distrust among healthcare providers and racial minorities in America that may make AAW less likely to accept healthcare services and/or procedures. In the same study by Smedley et al. (2003), evidence suggests minority patients may be more receptive and trusting of physicians who are minorities themselves. However, minority physicians represent only 9% of the physicians in the country; of the 9%, one-third is African-American. AAW who have perceived discrimination from White physicians are less likely to seek health care and are even less likely to find a healthcare provider they feel they can trust. This could be the reason AAW are more likely to avoid healthcare services altogether.

Existing Programs

Successful Programs

AAW are more likely to have multiple CVD risk factors at one time, so interventions that target multiple risk factors are necessary for success (Ebong & Breathett, 2020). The Love Your Heart program was a 12-week nutrition and physical activity intervention that aimed to reduce cardiovascular risk factors among African American women living in the Boston area (Rodriguez, Christopher, Johnson, Wang, & Foody, 2012). This program was culturally tailored for African American women, and it used a self-help group methodology to address the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects that affect weight and cardiovascular health. The intervention included fitness classes, educational sessions spotlighting the importance of nutrition and exercise on CVD, group meetings and discussions, and personalized wellness plans. The results of the study found significant improvements in CVD risk factors. Comparing the pre-and post-test data, participants reduced their systolic blood pressure, body-mass-index, body weight, and waist circumference. This program highlights the effectiveness of community-based interventions that combine health information, individual support, and group support to lower CVD risk.

Another successful program, Prime Time Sister Circles, was a 10-week health program that aimed to improve diet and increase physical activity among African American women aged >35 years across the country (Gaston, Porter, & Thomas, 2007). It utilized the Social Cognitive Theory and Transtheoretical Model for program creation. The intervention was a curriculum-based approach to behavioral change and incorporated a support group appeal. The groups met once a week for 10 weeks and received information about spirituality, self-esteem, self-care, nutrition, exercise, CVD, and diabetes. This program is unique in that it also targeted stress-relief strategies. The results of the study found improvements in the participants self-reported stress management, physical activity, and nutrition. Data also shows that the program improved participants knowledge of CVD risk factors and attitudes towards prioritizing their health. This study is yet another that emphasizes the value culturally tailored interventions in support group settings have on reducing CVD risk in African American women.

Unsuccessful Programs

STEPS (Sisters Together Empowered for Prevention and Success) to a Healthier Heart was a 12- week, quasi-experimental, pre-posttest educational intervention that targeted AAW between 35 and 65 years of age (Brown, Alexander, Cummins, Price, & Anderson-Booker, 2018). The purpose of this health program was to assess if AAW’s general knowledge about risk factors of heart disease improved with participation in informational and physical activity sessions. The women chose to participate in either the intervention group, which involved information and physical activity sessions, or the comparison group, which received an informational packet only. The Coronary Heart Disease Knowledge Test was used to assess each participant’s knowledge of heart disease risk factors. This program was ultimately unsuccessful because, in comparing the pre- and posttest data, no significant changes occurred and there were no between-group differences. One possible reason this program was unsuccessful could be due to the use of standard surveys, and future studies should use a more reliable and valid measurement to assess knowledge among AAW. Another possibility is due to the intervention’s short duration with little attention on physical activity. This program underscores the importance of multicomponent, culturally tailored interventions that address multiple risk factors for AAW for success.

Part II: Planning

Program Goals and Objectives

Program Goal Number 1

Reduce the impact psychosocial stressors have on the priority population’s CVD risk.

Project Objective

By December 2021, when comparing pre-post test scores, one-half of the participants will report lower general stress as measured by the general stress subscale of the Chronic Stress Questionnaire (CSQ).

Health Education Objectives

- By the end of the first trimester, the majority of the participants will be able to list three healthy and three unhealthy stress and anxiety relief practices.

- Upon completion of the program, one-half of the participants will be able to identify stressors associated with racism and discrimination and effective coping methods.

- Six months after completion of the program, one-half of the participants will be able to list at least one coping and/or stress management skill utilized daily.

Project Objective

By June 2022, one-fourth of participants will report higher levels of resilience, in comparison to pre-test scores, as measured by the Conner-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-25).

Health Education Objectives

- By the end of the second trimester, more than half of the participants will be able to identify factors that foster resilience.

- Upon completion of the program, one-fourth of the participants will be able to list three self-reflection practices.

Program Goal Number 2

Increase participation in physical activity and/or exercise that targets cardiac health among individuals in the priority population.

Project Objective

By June 2022, one-fourth of participants will engage in thirty minutes of moderate physical activity at least 3 times a week.

Health Education Objectives

- By the end of the first trimester, more than half of the participants will be able to identify three exercises that improve heart health.

- By the end of the first trimester, the majority of the participants will be able to identify three CVD risk factors associated with physical inactivity.

- One-half of the participants will be able to locate areas in the community with gyms and/or green space upon completion of the program.

Program Goal Number 3

Increase the awareness of primary and secondary prevention practices and their importance among individuals in the priority population.

Project Objective

By December 2023, yearly health care checkups among the participants will increase by 25%.

Health Education Objectives

- By the end of the second trimester, the majority of the participants will be able to identify two primary and two secondary prevention practices.

- By the end of the second trimester, the majority of the participants will be able to identify three CVD risk factors that are easily preventable by modifying behaviors.

- Upon completion of the program, one-third of the participants will be able to locate the nearest healthcare center in their community accessible to them.

- Upon completion of the program, one-fourth of the participants will be able to state the recommended schedule for healthcare screenings.

Theoretical Support of Intervention

Due to the high rates of depression seen among AAW, successful interventions must address both the physical and mental risk factors for CVD. The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) and the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) will both be used to guide the development of this program (McKenzie, Neiger, & Thackeray, 2013). According to McKenzie et al. (2013), the TTM posits that behavior change happens over time, and that people move through five distinct “stages of change” phases in the process of adopting a health behavior change. This model has been effective for a variety of health behavior changes because it considers that people may begin in different stages. Most individuals will not respond to action-oriented behavior change programs because the majority are not prepared to act. Specific principles are applied at specific stages to maximize efficacy and ensure individuals move forward to the next stage. In other words, individuals are matched with interventions depending on the stage they are in. The SCT posits that learning happens in a social context. Individual experiences, environmental factors, and the actions of others influence health behavior. An important component of the SCT is reinforcement. Theorists believe reinforcement is essential for learning. Moreover, reinforcement with the addition of an individual’s expectations of the outcome is what determines behavior.

The reason I chose to use two theories is because mental needs to be addressed at a personal level, however, past programs have shown that AAW respond to interventions best when group support and social interactions are given. I chose the TTM because it addresses each participant as individuals. Some AAW may fare better in the face of adversity than others, so the mental health status of the participants is going to vary. Additionally, though some participants will share the same barriers to action, others are going to have barriers no one else has. This is the best intrapersonal level theory to use for many reasons. Firstly, we can implement interventions that can best facilitate change based on the stage the participants are in. Interventions that require immediate action will lose the participants that are not ready for action. By allowing the participants to progress through the stages on their own time ensures maximum participants retention in the program. The second reason I chose this theory was because of how well the Processes of Change correlate to what our participants are likely to go through throughout the intervention. For example, after learning more about the psychosocial factors, participants may begin to notice each time they are subjected to toxic, negative emotions due to their environment, which is explained by the process of dramatic relief. This will accompany the realization of the effects it has on them and their environment, which is explained by the constructs of self- and environmental reevaluation. Further, the intervention’s aim of finding new ways to cope with stressors and fostering resiliency is explained by the construct of counterconditioning. Lastly, as explained by the construct of social liberation, being able to effectively cope with negative emotions can/will allow the participants to focus their attention on all the positive experiences they have.

To target the interpersonal level, I chose the SCT because it addresses the influence that observational learning has on behavior. As stated above, similar programs with the most success have included group support/meetings in the intervention. Participants credited their continued participation and enthusiasm to the relationships they created with others and the desire to help one another succeed. Seeing others succeed due to a behavior change influences others to adopt that change as well. I also chose this theory because it addresses the idea of monitoring and adjusting behavior to gain control over it. This is the best interpersonal level theory to use because of the emphasis it has on learning in social contexts. We already know AAW respond best with group support, and the SCT has roots in learning from and believing in others. AAW who may not feel confident in the behavior changes will be encouraged by seeing other women succeed, or they will be encouraged to try when they see the support other participants are giving them. For example, participants will gain knowledge and skills about how to eat healthy after learning about healthy dinner options, as explained by the construct of behavioral capability. When a participant shares their meal plan that they have been following, positive feedback and praise from program instructors and other participants will help to maintain that participant’s behavior change, which is explained by direct reinforcement. On the other hand, participants who are struggling with that same behavior change may be encouraged to work for it after seeing the commendation others receive, as explained by vicarious reinforcement. To maintain this behavior, the participant will have to monitor and adjust their behavior, which is explained by the construct of self-control. As their self-control increases and their healthy eating behavior is maintained, they will gain confidence in their ability to create meaningful change in their life, as explained by self-efficacy.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

2019 International & Big Name Support for #AceWeek

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy first day of asexual awareness week y’all.

408 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Asexual Awareness Week!!!

Acespecs, this is your time to shine, your time to be heard! Be loud and proud this week because you deserve it!! And to everyone else, I hope you use this week to shower your favorite local ace with all the love and acceptance in the world!!

And please don't listen to anyone who tries to bring you down this week. This is YOUR week to celebrate your identity and take pride in it! Don't let anyone take that away from you! They are nothing, and you are everything!! 💜🖤

I hope you all have a wonderful week!

#my posts#ace#ace positivity#asexual#acespec positivity#acespec#asexual awareness week#ace awareness week#aaw#aaw 2019#safeforace#lgbtq holidays#lgbtq+#lgbtq positivity#colored text

381 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Asexual Awareness Week to all the acespecs with adhd! I hope you’re Week is amazing, as well as the rest of adhd awareness month!

#chris rambles#asexual#adhd#adhd awarness month#asexual awareness week 2019#asexual awareness week#aaw2019#aaw 2019#aaw#aceweek2019#aceweek

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Aggressively Aro-spec Week! Todays collage is on animated characters

Adora/She-ra: aromantic

Carmen Sandiego, code name Black Sheep: aromantic

Ruby Rose: aromantic

Princess Merida: aromantic

Moana: aromantic

#AggressivelyArospecWeek#pride month#aaw 2019#hinacu#is moana a chief? wasnt clear at end of movie#character: adora#character: carmen sandiego#character: ruby rose#character: merida#character: moana#fandom: she ra and the princesses of power#fandom: carmen sandiego#fandom: rwby#fandom: disney#fanwork: pictures#AS: aromantic

402 notes

·

View notes

Photo

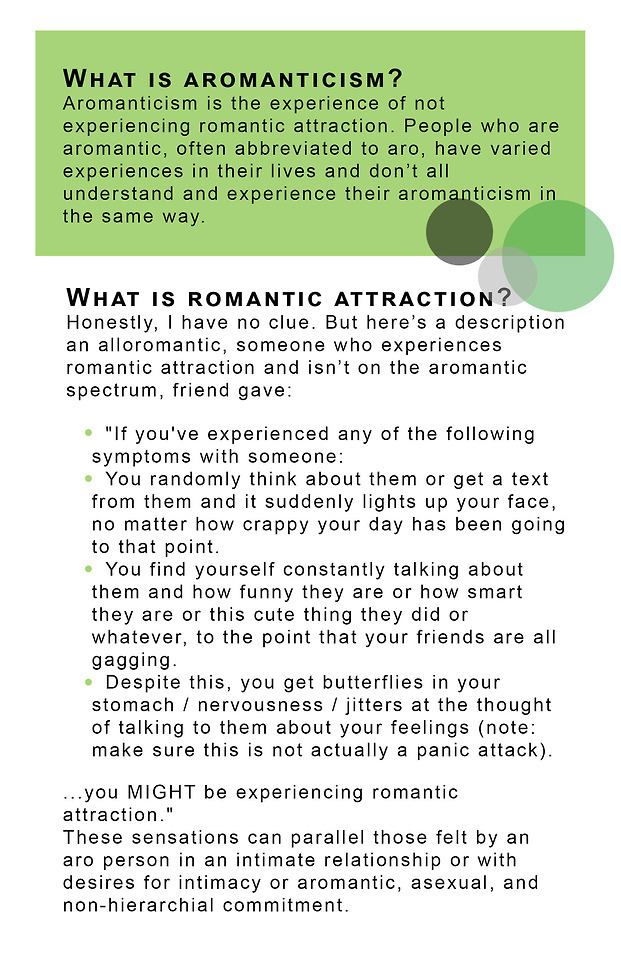

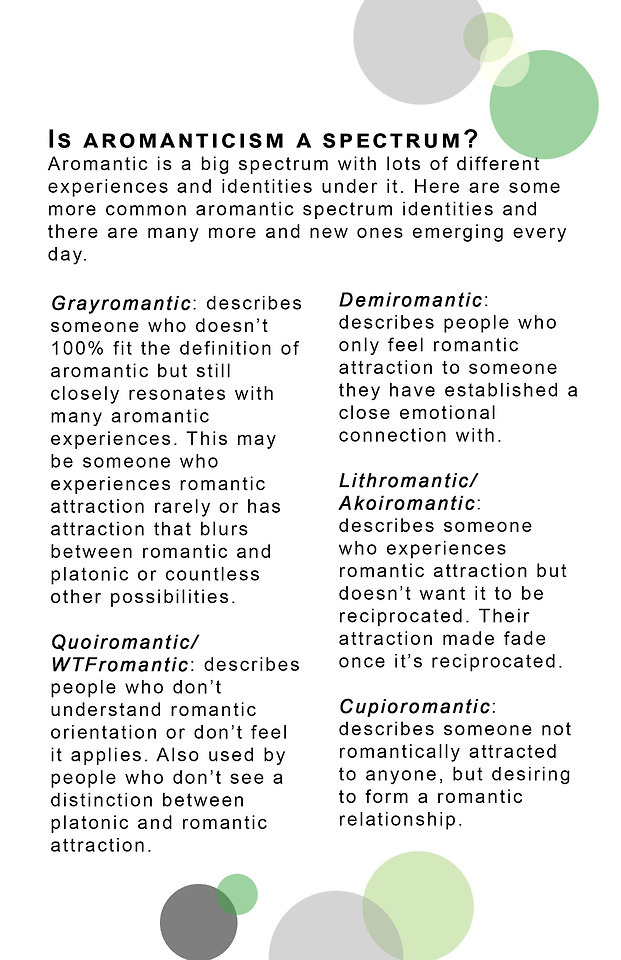

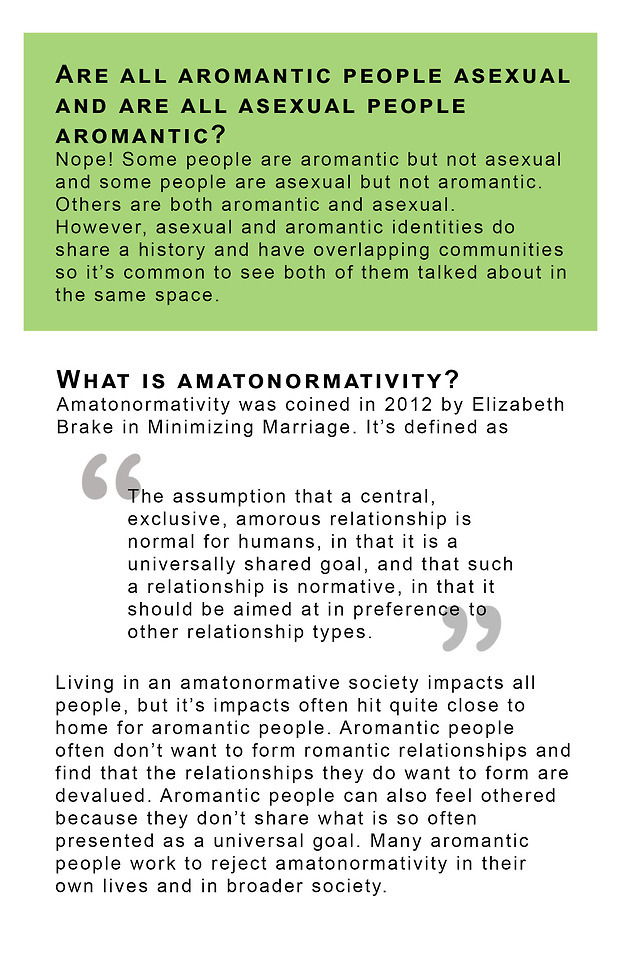

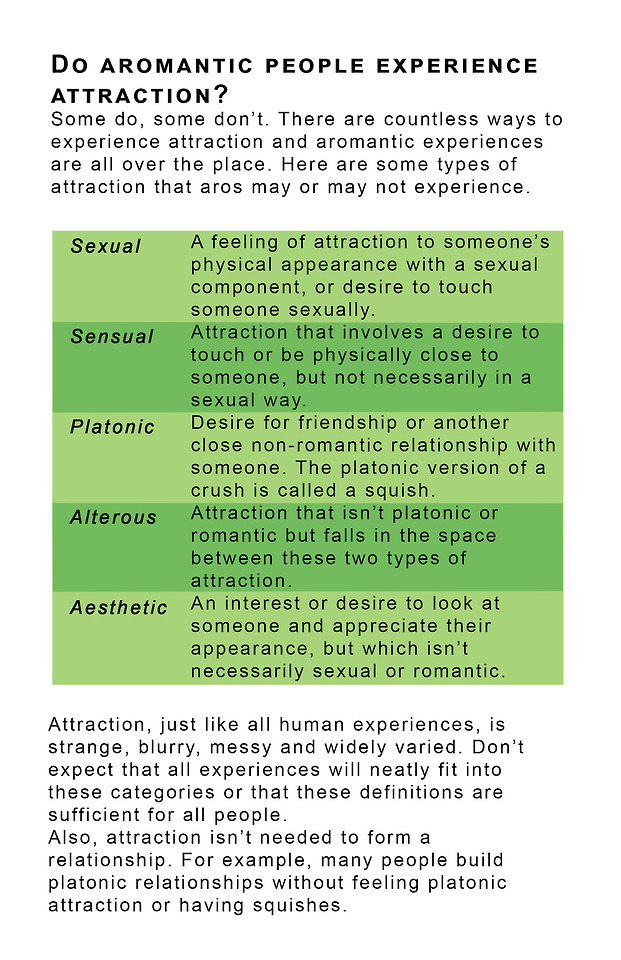

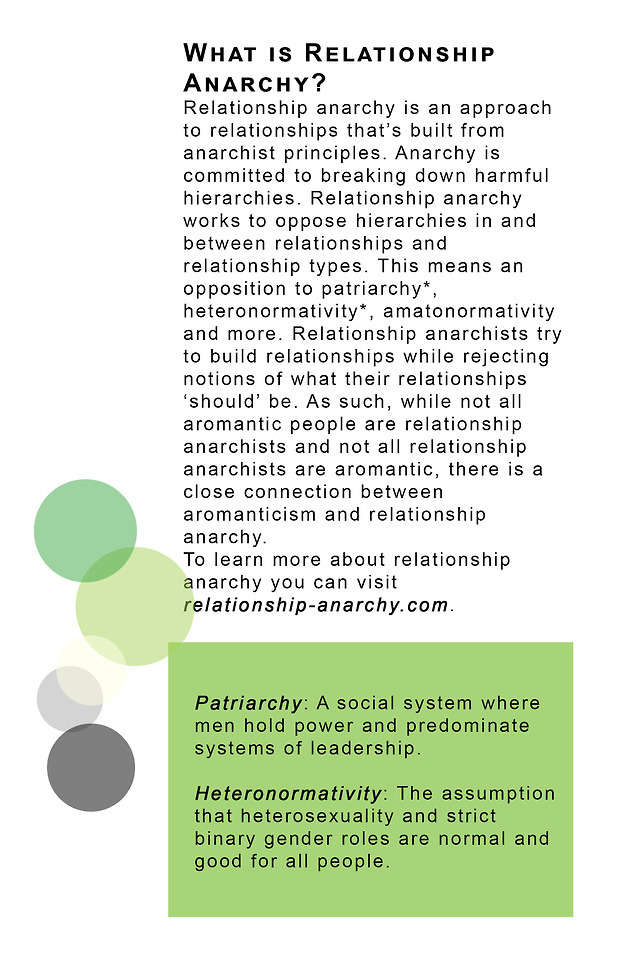

Happy Aro Awareness Week!!

Here's a little document with some aromanticism 101 information.

Read the whole thing here: https://bit.ly/2Et5lv6

Print it into little booklets: https://bit.ly/2tAhSqr

Check out the site I built with all this info and more: aromanticguide.wordpress.com

💚💛💚💛💚

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Ace Awareness Week, everybody

84 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A redraw/redesign of an Ace Awareness Week drawing I made two years ago.

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't ask Sami to suck your dick if you don't want him to do it.

Sami Callihan & Jake Crist vs The Besties In The World (AAW 'Windy City Classic XV' - Dec. 28, 2019)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Asexual people can want closed, monogamous relationships.

Just because someone doesn’t feel sexual attraction doesn’t mean they are okay with you sleeping with other people.

Some people may be okay with that but not all. Don’t assume that because you’re dating an asexual person that they’re okay with you sleeping with other people.

When you know how big of a deal sex is in the world due to how sexualised everything is, thinking that you aren’t enough for your partner and they have to look somewhere else for something many people consider important (especially for a healthy relationship) is really, really hurtful.

If you haven’t discussed it with your partner and they don’t want an open relationship then; It is still cheating. Depending on their type of Asexuality:

they may not want any sex with you but that doesn’t mean they’re okay with you going to someone else for it.

They may be open to having sex with you just maybe not as often as you like but that doesn’t mean they are okay with you going to someone else for it.

They could have sex with you regularly but still not be sexually attracted to you (since they are on the asexual spectrum) but that doesn’t mean that they are okay with you acting on an impulse for someone you are sexually attracted to.

All of the above could be really hurtful. Just because they don’t feel sexual attraction doesn’t mean they are okay with you sleeping with other people because they understand that romantic and sexual attractions are different. If it doesn’t apply to a ‘normal’ romantic relationship I.e your romantic and sexual partner being the same person with no-one else involved (for a closed monogamous relationship) then guess what?! That can still apply in a relationship with an Asexual person.

They shouldn’t feel bad for wanting these things when it’s what’s expected in a heteronormative or a non-poly queer relationship. It’s okay for them to want their partner to remain loyal to them if that’s what they want and they shouldn’t be expected to just live with it, if they’re partner goes elsewhere and they aren’t okay with it.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA, it’s AAWWWWWWWW

52 notes

·

View notes