#citizen potawatomi

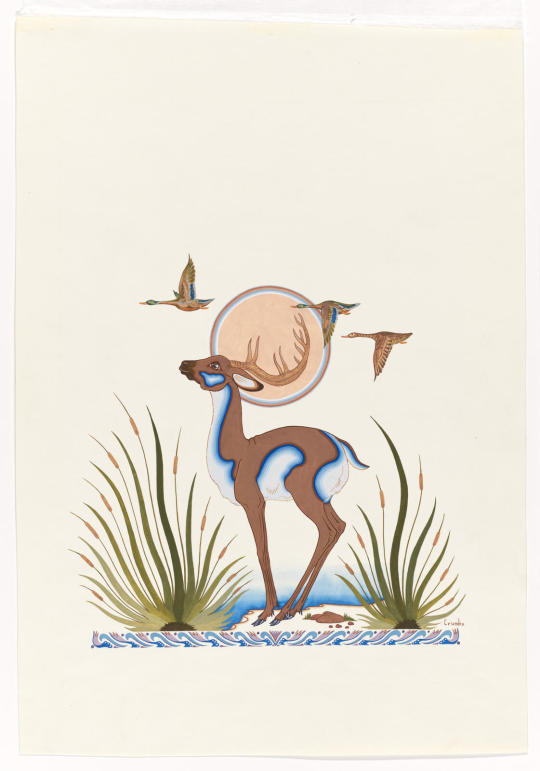

Photo

Woodrow Wilson Crumbo - Blue Deer and Mallard Ducks. mid 20th. century. Watercolor and tempera on paper.

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

Firelake Grand Casino: illegal retaliation?

Editorial Notation:

The following article is written based on information provided by the victim, witnesses, and phone recordings. We have also been made aware that another security officer, who had been sharing this very story to co-workers, was reportedly written up for doing so.

When making any form of complaint an employee should feel safe, regardless of their gender identities. The concept…

View On WordPress

#abuse#activism#casino#Citizens of Potawatomi Nation#civil rights#Facebook#Illegal#Native American#Tribe#War on Corruption#Wrongful Termination

0 notes

Text

As a botanist, Robin Wall Kimmerer has been trained to ask questions of nature with the tools of science. As a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, she embraces the notion that plants and animals are our oldest teachers. In Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer brings these lenses of knowledge together to show that the awakening of a wider ecological consciousness requires the acknowledgment and celebration of our reciprocal relationship with the rest of the living world. For only when we can hear the languages of other beings are we capable of understanding the generosity of the earth, and learning to give our own gifts in return.

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saskatoon, Juneberry, Shadbush, Shadblow, Sugarplum, Sarvis, Serviceberry -- these are among the many names for Amelanchier. Ethnobotanists know that the more names a plant has, the greater its cultural importance. The tree is beloved for its fruits, for medicinal use, and for the early froth of flowers that whiten woodland edges at the first hint of spring. Serviceberry is known as a calendar plant, so faithful is it to seasonal weather patterns. Its bloom is a sign that the ground has thawed and that the shad are running upstream -- or at least it was back in the day when rivers were clear and free enough to support their spawning. The derivation of the name “Service” from its relative Sorbus (also in the Rose Family) notwithstanding, the plant does provide myriad goods and services. Not only to humans but to many other citizens. It is a preferred browse of Deer and Moose, a vital source of early pollen for newly emerging insects, and host to a suite of butterfly larvae -- like Tiger Swallowtails, Viceroys, Admirals, and Hairstreaks -- and berry-feasting birds who rely on those calories in breeding season.

In Potawatomi, it is called Bozakmin, which is a superlative: the best of the berries. [...]

For me, the most important part of the word Bozakmin is “min,” the root for “berry.” It appears in our Potawatomi words for Blueberry, Strawberry, Raspberry, even Apple, Maize, and Wild Rice. The revelation in that word is a treasure for me, because it is also the root word for “gift.” [...] When we speak of these not as things or products or commodities, but as gifts, the whole relationship changes. [...] I accept the gift from the bush and then spread that gift with a dish of berries to my neighbor, who makes a pie to share with his friend, who feels so wealthy in food and friendship that he volunteers at the food pantry. You know how it goes.

To name the world as gift is to feel one’s membership in the web of reciprocity. [...] How we think ripples out to how we behave. If we view these berries, or that coal or forest, as an object, as property, it can be exploited as a commodity in a market economy. We know the consequences of that.

---

Text by: Robin Wall Kimmerer. “The Serviceberry: An Economy of Abundance.” Emergence Magazine. 26 October 2022.

395 notes

·

View notes

Text

"To be indigenous is to protect life on earth. By honouring the knowledge in the land, and caring for its keepers, we start to become indigenous to place."

An excerpt from: “In the Footsteps of Nanabozho: Becoming Indigenous to Place”, a chapter in Kimmerer’s book, Braiding Sweetgrass.

— Robin Wall Kimmerer is an author, scientist, professor, member of Citizen Potawatomi Nation

#Ancestors Alive!#What is Remembered Lives#Memory & Spirit of Place#love#heart and soul#belonging#protect life on earth#caring for its keepers#indigenous to place#Robin Wall Kimmerer#quotes#ancient ways#sacred ways#braiding sweetgrass

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One with Nature: Connecting with the Natural World

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones

Today many of us live indoor lives, disconnected from the natural world as never before. And yet nature remains deeply ingrained in our language, culture and consciousness. For centuries, we have acted on an intuitive sense that we need communion with the wild to feel well. Now, in the moment of our great migration away from the rest of nature, more and more scientific evidence is emerging to confirm its place at the heart of our psychological wellbeing. So what happens, asks acclaimed journalist Lucy Jones, as we lose our bond with the natural world--might we also be losing part of ourselves?

Delicately observed and rigorously researched, Losing Eden is an enthralling journey through this new research, exploring how and why connecting with the living world can so drastically affect our health. Travelling from forest schools in East London, to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, via Poland's primeval woodlands, Californian laboratories and ecotherapists' couches, Jones takes us to the cutting edge of human biology, neuroscience and psychology, and discovers new ways of understanding our increasingly dysfunctional relationship with the earth. Urgent and uplifting, Losing Eden is a rallying cry for a wilder way of life - for finding asylum in the soil and joy in the trees - which might just help us to save the living planet, as well as ourselves, from a future of ecological grief.

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer

As a botanist, Robin Wall Kimmerer has been trained to ask questions of nature with the tools of science. As a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, she embraces the notion that plants and animals are our oldest teachers. In Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer brings these lenses of knowledge together to show that the awakening of a wider ecological consciousness requires the acknowledgment and celebration of our reciprocal relationship with the rest of the living world. For only when we can hear the languages of other beings are we capable of understanding the generosity of the earth, and learning to give our own gifts in return.

Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest by Suzanne Simard

From the world's leading forest ecologist who forever changed how people view trees and their connections to one another and to other living things in the forest--a moving, deeply personal journey of discovery.

Suzanne Simard is a pioneer on the frontier of plant communication and intelligence; she's been compared to Rachel Carson, hailed as a scientist who conveys complex, technical ideas in a way that is dazzling and profound. Her work has influenced filmmakers (the Tree of Souls of James Cameron's Avatar) and her TED talks have been viewed by more than 10 million people worldwide.

Now, in her first book, Simard brings us into her world, the intimate world of the trees, in which she brilliantly illuminates the fascinating and vital truths--that trees are not simply the source of timber or pulp, but are a complex, interdependent circle of life; that forests are social, cooperative creatures connected through underground networks by which trees communicate their vitality and vulnerabilities with communal lives not that different from our own.

The Vanishing Face of Gaia: A Final Warning by James E. Lovelock

Celebrities drive hybrids, Al Gore won the Nobel Peace Prize, and supermarkets carry no end of so-called “green” products. And yet the environmental crisis is only getting worse. In The Vanishing Face of Gaia, the eminent scientist James Lovelock argues that the earth is lurching ever closer to a permanent “hot state” – and much more quickly than most specialists think. There is nothing humans can do to reverse the process; the planet is simply too overpopulated to halt its own destruction by greenhouse gases.In order to survive, mankind must start preparing now for life on a radically changed planet. The meliorist approach outlined in the Kyoto Treaty must be abandoned in favor of nuclear energy and aggressive agricultural development on the small areas of earth that will remain arable.

A reluctant jeremiad from one of the environmental movement’s elder statesmen, The Vanishing Face of Gaia offers an essential wake-up call for the human race.

#nonfiction#non-fiction#non-fiction books#history#Environment#biology#botany#nature#natural science#sustainability#science#ecology#to read#tbr#booklr#book blog#reading recommendations#Book Recommendations#book recs#library books#informed reading#reading for a better world

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

As a botanist, Robin Wall Kimmerer has been trained to ask questions of nature with the tools of science. As a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, she embraces the notion that plants and animals are our oldest teachers. In Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer brings these lenses of knowledge together to show that the awakening of a wider ecological consciousness requires the acknowledgment and celebration of our reciprocal relationship with the rest of the living world. For only when we can hear the languages of other beings are we capable of understanding the generosity of the earth, and learning to give our own gifts in return.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

America’s Biggest Museums Fail to Return Native American Human Remains

by Logan Jaffe, Mary Hudetz and Ash Ngu, ProPublica, and Graham Lee Brewer, NBC News

Series: The Repatriation Project

As the United States pushed Native Americans from their lands to make way for westward expansion throughout the 1800s, museums and the federal government encouraged the looting of Indigenous remains, funerary objects and cultural items. Many of the institutions continue to hold these today — and in some cases resist their return despite the 1990 passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

“We never ceded or relinquished our dead. They were stolen,” James Riding In, then an Arizona State University professor who is Pawnee, said of the unreturned remains.

ProPublica this year is investigating the failure of NAGPRA to bring about the expeditious return of human remains by federally funded universities and museums. Our reporting, in partnership with NBC News, has found that a small group of institutions and government bodies has played an outsized role in the law’s failure.

Ten institutions hold about half of the Native American remains that have not been returned to tribes. These include old and prestigious museums with collections taken from ancestral lands not long after the U.S. government forcibly removed Native Americans from them, as well as state-run institutions that amassed their collections from earthen burial mounds that had protected the dead for hundreds of years. Two are arms of the U.S. government: the Interior Department, which administers the law, and the Tennessee Valley Authority, the nation’s largest federally owned utility.

An Interior Department spokesperson said it complies with its legal obligations and that its bureaus (such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Bureau of Land Management) are not required to begin the repatriation of “culturally unidentifiable human remains” unless a tribe or Native Hawaiian organization makes a formal request.

Tennessee Valley Authority Archaeologist and Tribal Liaison Marianne Shuler said the agency is committed to “partnering with federally recognized tribes as we work through the NAGPRA process.”

The law required institutions to publicly report their holdings and to consult with federally recognized tribes to determine which tribes human remains and objects should be repatriated to. Institutions were meant to consider cultural connections, including oral traditions as well as geographical, biological and archaeological links.

Yet many institutions have interpreted the definition of “cultural affiliation” so narrowly that they’ve been able to dismiss tribes’ connections to ancestors and keep remains and funerary objects. Throughout the 1990s, institutions including the Ohio History Connection and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville thwarted the repatriation process by categorizing everything in their collections that might be subject to the law as “culturally unidentifiable.”

Ohio History Connection’s director of American Indian relations, Alex Wesaw, who is also a citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, said that the institution’s original designation of so many collections as culturally unidentifiable may have “been used as a means to keep people on shelves for research and for other things that our institution just doesn’t allow anymore.”

In a statement provided to ProPublica, a University of Tennessee, Knoxville spokesperson said that the university is “actively building relationships with and consulting with Tribal communities.”

ProPublica found that the American Museum of Natural History has not returned some human remains taken from the Southwest, arguing that they are too old to determine which tribes — among dozens in the region — would be the correct ones to repatriate to. In the Midwest, the Illinois State Museum for decades refused to establish a cultural affiliation for Native American human remains that predated the arrival of Europeans in the region in 1673, citing no reliable written records during what archaeologists called the “pre-contact” or “prehistoric” period.

The American Museum of Natural History declined to comment for this story.

In a statement, Illinois State Museum Curator of Anthropology Brooke Morgan said that “archaeological and historical lines of evidence were privileged in determining cultural affiliation” in the mid-1990s, and that “a theoretical line was drawn in 1673.” Morgan attributed the museum’s past approach to a weakness of the law that she said did not encourage multiple tribes to collectively claim cultural affiliation, a practice she said is common today.

As of last month, about 200 institutions — including the University of Kentucky’s William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology and the nonprofit Center for American Archeology in Kampsville, Illinois — had repatriated none of the remains of more than 14,000 Native Americans in their collections. Some institutions with no recorded repatriations possess the remains of a single individual; others have as many as a couple thousand.

A University of Kentucky spokesperson told ProPublica the William S. Webb Museum “is committed to repatriating all Native American ancestral remains and funerary belongings, sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony to Native nations” and that the institution has recently committed $800,000 toward future efforts.

Jason L. King, the executive director of the Center for American Archeology, said that the institution has complied with the law: “To date, no tribes have requested repatriation of remains or objects from the CAA.”

When the federal repatriation law passed in 1990, the Congressional Budget Office estimated it would take 10 years to repatriate all covered objects and remains to Native American tribes. Today, many tribal historic preservation officers and NAGPRA professionals characterize that estimate as laughable, given that Congress has never fully funded the federal office tasked with overseeing the law and administering consultation and repatriation grants. Author Chip Colwell, a former curator at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, estimates repatriation will take at least another 70 years to complete. But the Interior Department, now led by the first Native American to serve in a cabinet position, is seeking changes to regulations that would push institutions to complete repatriation within three years. Some who work on repatriation for institutions and tribes have raised concerns about the feasibility of this timeline.

Our investigation included an analysis of records from more than 600 institutions; interviews with more than 100 tribal leaders, museum professionals and others; and the review of nearly 30 years of transcripts from the federal committee that hears disputes related to the law.

D. Rae Gould, executive director of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Initiative at Brown University and a member of the Hassanamisco Band of Nipmucs of Massachusetts, said institutions that don’t want to repatriate often claim there’s inadequate evidence to link ancestral human remains to any living people.

Gould said “one of the faults with the law” is that institutions, and not tribes, have the final say on whether their collections are considered culturally related to the tribes seeking repatriation. “Institutions take advantage of it,” she said.

Some of the nation’s most prestigious museums continue to hold vast collections of remains and funerary objects that could be returned under NAGPRA.

Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in Cambridge, Massachusetts, University of California, Berkeley and the Field Museum in Chicago each hold the remains of more than 1,000 Native Americans. Their earliest collections date back to the 19th and early 20th centuries, when their curators sought to amass encyclopedic collections of human remains.

Many anthropologists from that time justified large-scale collecting as a way to preserve evidence of what they wrongly believed was an extinct race of “Moundbuilders” — one that predated and was unrelated to Native Americans. Later, after that theory proved to be false, archaeologists still excavated gravesites under a different racist justification: Many scientists who embraced the U.S. eugenics movement used plundered craniums for studies that argued Native Americans were inferior to white people based on their skull sizes.

These colonialist myths were also used to justify the U.S. government’s brutality toward Native Americans and fuel much of the racism that they continue to face today.

“Native Americans have always been the object of study instead of real people,” said Shannon O’Loughlin, chief executive of the Association on American Indian Affairs and a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

As the new field of archaeology gained momentum in the 1870s, the Smithsonian Institution struck a deal with U.S. Army Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman to pay each of his soldiers up to $500 — or roughly $14,000 in 2022 dollars — for items such as clothing, weapons and everyday tools sent back to Washington.

“We are desirous of procuring large numbers of complete equipments in the way of dress, ornament, weapons of war” and “in fact everything bearing upon the life and character of the Indians,” Joseph Henry, the first secretary of the Smithsonian, wrote to Sherman on May 22, 1873.

The Smithsonian Institution today holds in storage the remains of roughly 10,000 people, more than any other U.S. museum. However, it reports its repatriation progress under a different law, the National Museum of the American Indian Act. And it does not publicly share information about what it has yet to repatriate with the same detail that NAGPRA requires of institutions it covers. Instead, the Smithsonian shares its inventory lists with tribes, two spokespeople told ProPublica.

Frederic Ward Putnam, who was appointed curator of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology in 1875, commissioned and funded excavations that would become some of the earliest collections at Harvard, the American Museum of Natural History and the Field Museum. He also helped establish the anthropology department and museum at UC Berkeley — which holds more human remains taken from Native American gravesites than any other U.S. institution that must comply with NAGPRA.

For the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Putnam commissioned the self-taught archaeologist Warren K. Moorehead to lead excavations in southern Ohio to take human remains and “relics” for display. Much of what Moorehead unearthed from Ohio’s Ross and Warren counties became founding collections of the Field Museum.

A few years after Moorehead’s excavations, the American Museum of Natural History co-sponsored rival expeditions to the Southwest; items were looted from New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon and shipped by train to New York. They remain premiere collections of the institution.

As of last month the Field Museum has returned to tribes legal control of 28% of the remains of 1,830 Native Americans it has reported to the National Park Service, which administers the law and keeps inventory data. It still holds at least 1,300 Native American remains.

In a statement, the Field Museum said that data from the park service is out of date. (The museum publishes separate data on its repatriation website that it says is frequently updated and more accurate.) A spokesperson told ProPublica that “all Native American human remains under NAGPRA are available for return.”

The museum has acknowledged that Moorehead’s excavations would not meet today’s standards. But the museum continues to benefit from those collections. Between 2003 and 2005, it accepted $400,000 from the National Endowment for the Humanities to preserve its North American Ethnographic and Archaeological collection — including the material excavated by Moorehead — for future use by anthropologists and other researchers. That’s nearly four times more than it received in grants from the National Park Service during the same period to support its repatriation efforts under NAGPRA.

In a statement, the museum said it has the responsibility to care for its collections and that the $400,000 grant was “used for improved stewardship of objects in our care as well as organizing information to better understand provenance and to make records more publicly accessible.”

Records show the Field Museum has categorized all of its collections excavated by Moorehead as culturally unidentifiable. The museum said that in 1995, it notified tribes with historical ties to southern Ohio about those collections but did not receive any requests for repatriation or disposition. Helen Robbins, the museum’s director of repatriation, said that formally linking specific tribes with those sites is challenging, but that it may be possible after consultations with tribes.

The museum’s president and CEO, Julian Siggers, has criticized proposals intended to speed up repatriation. In March 2022, Siggers wrote to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland that if new regulations empowered tribes to request repatriations on the basis of geographical ties to collections rather than cultural ties, museums such as the Field would need more time and money to comply. ProPublica found that the Field Museum has received more federal money to comply with NAGPRA than any other institution in the country.

Robbins said that among the institution’s challenges to repatriation is a lack of funding and staff. “That being said,” added Robbins, “we recognize that much of this work has taken too long.”

From the 1890s through the 1930s, archaeologists carried out large-scale excavations of burial mounds throughout the Midwest and Southeast, regions where federal policy had forcibly pushed tribes from their land. Of the 10 institutions that hold the most human remains in the country, seven are in regions that were inhabited by Indigenous people with mound building cultures, ProPublica found.

Among them are the Ohio History Connection, the University of Kentucky’s William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology, the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and the Illinois State Museum.

Archaeological research suggests that the oldest burial mounds were built roughly 11,000 years ago and that the practice lasted through the 1400s. The oral histories of many present-day tribes link their ancestors to earthen mounds. Their structures and purposes vary, but many include spaces for communal gatherings and platforms for homes and for burying the dead. But some institutions have argued these histories aren’t adequate proof that today’s tribes are the rightful stewards of the human remains and funerary objects removed from the mounds, which therefore should stay in museums.

Like national institutions, local museums likewise make liberal use of the “culturally unidentifiable” designation to resist returning remains. For example, in 1998 the Ohio Historical Society (now Ohio History Connection) categorized its entire collection, which today includes more than 7,100 human remains, as “culturally unidentifiable.” It has made available for return the remains of 17 Native Americans, representing 0.2% of the human remains in its collections.

“It’s tough for folks who worked in the field their entire career and who are coming at it more from a colonial perspective — that what you would find in the ground is yours,” said Wesaw of previous generations’ practices. “That’s not the case anymore. That’s not how we operate.”

For decades, Indigenous people in Ohio have protested the museum’s decisions, claiming in public meetings of the federal committee that oversees how the law is implemented that their oral histories trace back to mound-building cultures. As one commenter, Jean McCoard of the Native American Alliance of Ohio, pointed out in 1997, there are no federally recognized tribes in Ohio because they were forcibly removed. As a result, McCoard argued, archaeologists in the state have been allowed to disassociate ancestral human remains from living people without much opposition. Since the early 1990s, the Native American Alliance of Ohio has advocated for the reburial of all human remains held by Ohio History Connection. It has yet to happen.

Wesaw said that the museum is starting to engage more with tribes to return their ancestors and belongings. Every other month, the museum’s NAGPRA specialist— a newly created position that is fully dedicated to its repatriation work — convenes virtual meetings with leaders from many of the roughly 45 tribes with ancestral ties to Ohio.

But, Wesaw said, the challenges run deep.

“It’s an old museum,” said Wesaw. “Since 1885, there have been a number of archaeologists that have made their careers on the backs of our ancestors pulled out of the ground or mounds. It’s really, truly heartbreaking when you think about that.”

Moreover, ProPublica’s investigation found that some collections were amassed with the help of federal funding. The vast majority of NAGPRA collections held by the University of Kentucky’s William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology are from excavations funded by the federal government under the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration from the late 1930s into the 1940s. Kentucky’s rural and impoverished counties held burial mounds, and Washington funded excavations of 48 sites in at least 12 counties to create jobs for the unemployed.

More than 80% of the Webb Museum’s holdings that are subject to return under federal law originated from WPA excavations. The museum, which in 1996 designated every one of its collections as “culturally unidentifiable,” has yet to repatriate any of the roughly 4,500 human remains it has reported to the federal government. However, the museum has recently hired its first NAGPRA coordinator and renewed consultations with tribal nations after decades of avoiding repatriation. A spokesperson told ProPublica that one ongoing repatriation project at the museum will lead to the return of about 15% of the human remains in its collections.

In a statement, a museum spokesperson said that “we recognize the pain caused by past practices” and that the institution plans to commit more resources toward repatriation.

The University of Kentucky recently told ProPublica that it plans to spend more than $800,000 between 2023 and 2025 on repatriation, including the hiring of three more museum staff positions.

In 2010, the Interior Department implemented a new rule that provided a way for institutions to return remains and items without establishing a cultural affiliation between present-day tribes and their ancestors. But, ProPublica found, some institutions have resisted doing so.

Experts say a lack of funding from Congress to the National NAGPRA Program has hampered enforcement of the law. The National Park Service was only recently able to fund one full-time staff position dedicated to investigating claims that institutions are not complying with the law; allegations can range from withholding information from tribes about collections, to not responding to consultation requests, to refusing to repatriate. Previously, the program relied on a part-time investigator.

Moreover, institutions that have violated the law have faced only minuscule fines, and some are not fined at all even after the Interior Department has found wrongdoing. Since 1990, the Interior Department has collected only $59,111.34 from 20 institutions for which it had substantiated allegations. That leaves tribal nations to shoulder the financial and emotional burden of the repatriation work.

The Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, a tribe in California, pressured UC Berkeley for years to repatriate more than a thousand ancestral remains, according to the tribe’s attorney. It finally happened in 2018 following a decade-long campaign that involved costly legal wrangling and travel back and forth to Berkeley by the tribes’ leaders.

“To me, there’s no money, there’s no dollar amount, on the work to be done. But the fact is, not every tribe has the same infrastructure and funding that others have,” said Nakia Zavalla, the cultural director for the tribe. “I really feel for those tribes that don’t have the funding, and they’re relying just on federal funds.”

A UC Berkeley spokesperson declined to comment on its interactions with the Santa Ynez Chumash, saying the school wants to prioritize communication with the tribe.

The University of Alabama Museums is among the institutions that have forced tribes into lengthy disputes over repatriation.

In June 2021, seven tribal nations indigenous to what is now the southeastern United States collectively asked the university to return the remains of nearly 6,000 of their ancestors. Their ancestors had been among more than 10,000 whose remains were unearthed by anthropologists and archaeologists between the 1930s and the 1980s from the second-largest mound site in the country. The site, colonially known as Moundville, was an important cultural and trade hub for Muskogean-speaking people between about 1050 and 1650.

Tribes had tried for more than a decade to repatriate Moundville ancestors, but the university had claimed they were all “culturally unidentifiable.” Emails between university and tribal leaders in 2018 show that when the university finally agreed to begin repatriation, it insisted that before it could return the human remains it needed to re-inventory its entire Moundville collection — a process it said would take five years. The “re-inventory” would entail photographing and CT scanning human remains to collect data for future studies, which the tribes opposed.

In October 2021, leaders from the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, Chickasaw Nation, Muscogee (Creek) Nation, Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, and Seminole Tribe of Florida brought the issue to the federal NAGPRA Review Committee, which can recommend a finding of cultural affiliation that is not legally binding. (Disputes over these findings are relatively rare.) The tribal leaders submitted a 117-page document detailing how Muskogean-speaking tribes are related and how their shared history can be traced back to the Moundville area long before the arrival of Europeans.

“Our elders tell us that the Muskogean-speaking tribes are related to each other. We have a shared history of colonization and a shared history of rebuilding from it,” Ian Thompson, a tribal historic preservation officer with the Choctaw Nation, told the NAGPRA review committee in 2021.

The tribes eventually forced the largest repatriation in NAGPRA’s history. Last year, the university agreed to return the remains of 10,245 ancestors.

In a statement, a University of Alabama Museums spokesperson said, “To honor and preserve historical and cultural heritage, the proper care of artifacts and ancestral remains of Muskogean-speaking peoples has been and will continue to be imperative to UA.” The university declined to comment further “out of respect for the tribes,” but added that “we look forward to continuing our productive work” with them.

The University of Alabama Museums still holds the remains of more than 2,900 Native Americans.

Many tribal and museum leaders say they are optimistic that a new generation of archaeologists, as well as museum and institutional leaders, want to better comply with the law.

At the University of Oklahoma, for instance, new archaeology department hires were shocked to learn about their predecessors’ failures. Marc Levine, associate curator of archaeology at the university’s Sam Noble Museum, said that when he arrived in 2013, there was more than enough evidence to begin repatriation, but his predecessors hadn’t prioritized the work. Through collaboration with tribal nations, Levine has compiled evidence that would allow thousands of human remains to be repatriated — and NAGPRA work isn’t technically part of his job description. The university has no full-time NAGPRA coordinator. Still, Levine estimates that at the current pace, repatriating the university’s holdings could take another decade.

Prominent institutions such as Harvard have issued public apologies in recent years for past collection practices, even as criticism continues over their failure to complete the work of repatriation. (Harvard did not respond to multiple requests for comment).

Other institutions under fire, such as UC Berkeley, have publicly pledged to prioritize repatriation. And the Society for American Archaeology, a professional organization that argued in a 1986 policy statement that “all human remains should receive appropriate scientific study,” now recommends archaeologists obtain consent from descendant communities before conducting studies.

In October, the Biden administration proposed regulations that would eliminate “culturally unidentifiable” as a designation for human remains, among other changes. Perhaps most significantly, the regulations would direct institutions to defer to tribal nations’ knowledge of their customs, traditions and histories when making repatriation decisions.

But for people who have been doing the work since its passage, NAGPRA was never complicated.

“You either want to do the right thing or you don’t,” said Brown University’s Gould.

She added: “It’s an issue of dignity at this point.”

#article#NAGPRA#native american#indigenous#repatriation#museum repatriation#racism#colonialism#eugenics#anti indigenous violence#anti indigenous racism#death#graves#burials#ask to tag#full article under the cut#bolding mostly mine

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summer TBR (so far)

A Court of Silver Flames (ACOTAR series) by Sarah J. Maas

Nesta Archeron has always been prickly-proud, swift to anger, and slow to forgive. And ever since being forced into the Cauldron and becoming High Fae against her will, she's struggled to find a place for herself within the strange, deadly world she inhabits. Worse, she can't seem to move past the horrors of the war with Hybern and all she lost in it. The one person who ignites her temper more than any other is Cassian, the battle-scarred warrior whose position in Rhysand and Feyre's Night Court keeps him constantly in Nesta's orbit. But her temper isn't the only thing Cassian ignites. The fire between them is undeniable, and only burns hotter as they are forced into close quarters with each other.

Meanwhile, the treacherous human queens who returned to the Continent during the last war have forged a dangerous new alliance, threatening the fragile peace that has settled over the realms. And the key to halting them might very well rely on Cassian and Nesta facing their haunting pasts. Against the sweeping backdrop of a world seared by war and plagued with uncertainty, Nesta and Cassian battle monsters from within and without as they search for acceptance-and healing-in each other's arms.

House of Earth and Blood (Crescent City series) by Sarah J. Maas

Bryce Quinlan had the perfect life-working hard all day and partying all night-until a demon murdered her closest friends, leaving her bereft, wounded, and alone. When the accused is behind bars but the crimes start up again, Bryce finds herself at the heart of the investigation. She'll do whatever it takes to avenge their deaths.

Hunt Athalar is a notorious Fallen angel, now enslaved to the Archangels he once attempted to overthrow. His brutal skills and incredible strength have been set to one purpose-to assassinate his boss's enemies, no questions asked. But with a demon wreaking havoc in the city, he's offered an irresistible deal: help Bryce find the murderer, and his freedom will be within reach.

As Bryce and Hunt dig deep into Crescent City's underbelly, they discover a dark power that threatens everything and everyone they hold dear, and they find, in each other, a blazing passion-one that could set them both free, if they'd only let it.

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer

As a botanist, Robin Wall Kimmerer has been trained to ask questions of nature with the tools of science. As a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, she embraces the notion that plants and animals are our oldest teachers. In Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer brings these lenses of knowledge together to show that the awakening of a wider ecological consciousness requires the acknowledgment and celebration of our reciprocal relationship with the rest of the living world. For only when we can hear the languages of other beings are we capable of understanding the generosity of the earth, and learning to give our own gifts in return.

The Red Tent by Anita Diamant

Her name is Dinah. In the Bible, her life is only hinted at in a brief and violent detour within the more familiar chapters of the Book of Genesis that are about her father, Jacob, and his dozen sons. Told in Dinah's voice, this novel reveals the traditions and turmoils of ancient womanhood—the world of the red tent. It begins with the story of her mothers—Leah, Rachel, Zilpah, and Bilhah—the four wives of Jacob. They love Dinah and give her gifts that sustain her through a hard-working youth, a calling to midwifery, and a new home in a foreign land. Dinah's story reaches out from a remarkable period of early history and creates an intimate connection with the past. Deeply affecting, The Red Tent combines rich storytelling with a valuable achievement in modern fiction: a new view of biblical women's society.

Orlando by Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf's Orlando 'The longest and most charming love letter in literature', playfully constructs the figure of Orlando as the fictional embodiment of Woolf's close friend and lover, Vita Sackville-West. Spanning three centuries, the novel opens as Orlando, a young nobleman in Elizabeth's England, awaits a visit from the Queen and traces his experience with first love as England under James I lies locked in the embrace of the Great Frost. At the midpoint of the novel, Orlando, now an ambassador in Constantinople, awakes to find that he is now a woman, and the novel indulges in farce and irony to consider the roles of women in the 18th and 19th centuries. As the novel ends in 1928, a year consonant with full suffrage for women. Orlando, now a wife and mother, stands poised at the brink of a future that holds new hope and promise for women.

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

Here is a book as joyous and painful, as mysterious and memorable, as childhood itself. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings captures the longing of lonely children, the brute insult of bigotry, and the wonder of words that can make the world right. Maya Angelou’s debut memoir is a modern American classic beloved worldwide.

Sent by their mother to live with their devout, self-sufficient grandmother in a small Southern town, Maya and her brother, Bailey, endure the ache of abandonment and the prejudice of the local “powhitetrash.” At eight years old and back at her mother’s side in St. Louis, Maya is attacked by a man many times her age—and has to live with the consequences for a lifetime. Years later, in San Francisco, Maya learns that love for herself, the kindness of others, her own strong spirit, and the ideas of great authors (“I met and fell in love with William Shakespeare”) will allow her to be free instead of imprisoned.

Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner

A memoir about growing up Korean American, losing her mother, and forging her own identity.

Michelle Zauner tells of growing up one of the few Asian American kids at her school in Eugene, Oregon; of struggling with her mother’s particular, high expectations of her; of a painful adolescence; of treasured months spent in her grandmother’s tiny apartment in Seoul, where she and her mother would bond, late at night, over heaping plates of food.

As she grew up, moving to the East Coast for college, finding work in the restaurant industry, and performing gigs with her fledgling band—and meeting the man who would become her husband—her Koreanness began to feel ever more distant, even as she found the life she wanted to live. It was her mother’s diagnosis of terminal cancer, when Michelle was twenty-five, that forced a reckoning with her identity and brought her to reclaim the gifts of taste, language, and history her mother had given her.

Cunt: A Declaration of Independence by Inga Muscio

An ancient title of respect for women, the word cunt long ago veered off this noble path. Inga Muscio traces the road from honor to expletive, giving women the motivation and tools to claim cunt as a positive and powerful force in their lives. In this fully revised edition, she explores, with candidness and humor, such traditional feminist issues as birth control, sexuality, jealousy between women, and prostitution with a fresh attitude for a new generation of women. Sending out a call for every woman to be the Cunt lovin Ruler of Her Sexual Universe, Muscio stands convention on its head by embracing all things cunt-related.

Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype by Clarissa Pinkola Estés

"Within every woman there is a wild and natural creature, a powerful force, filled with good instincts, passionate creativity, and ageless knowing. Her name is Wild Woman, but she is an endangered species. Though the gifts of wildish nature come to us at birth, society's attempt to 'civilize' us into rigid roles has plundered this treasure, and muffled deep, life-giving messages of our own souls. Without Wild Woman, we become overdomesticated, fearful, uncreative, trapped."

In her now-classic book that spent 144 weeks on the New York Times hardcover bestseller list, and is translated into 35 languages, Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Ph.D., shows how woman's vitality can be restored through what she calls "psychic archaeological digs" into the ruins of the female unconscious. Dr. Estés uses her families' ethnic tales, washed and rinsed in the blood of wars and survival, multicultural myths, her own lyric writing of those fairy tales, folk tales, and stories chosen from her life witness, and also research ongoing for twenty years… that help women reconnect with the healthy, instinctual, visionary attributes of the Wild Woman archetype.

Glenstone Field Guide 02 Edited by Emily Wei Rales and Fanna Gebreyesus

This Field Guide intends to serve as a lighthearted, by no means exhaustive primer for the curious Glenstone visitor. Structured as an illustrated index, it is divided into three sections: art, architecture, and landscape. Each section includes related terms and entries written by Glenstone staff and collaborators. Collectively, these voices share the multiple ideas, histories, anecdotes, and facts that make up the Glenstone story, and offer a glimpse into what can be seen onsite. Integrated throughout are statements from founders Emily Wei Rales and Mitchell P. Rales that highlight the key principles of community, sustainability, design, integration, and direct engagement, which guide Glenstone’s mission. Glenstone exists for you, our visitor, and we hope you will explore, engage, enjoy, and return often. You are always welcome.

#books#tbr#summer tbr#a court of silver flames#acosf#crecent city#sarah j maas#house of earth and blood#braiding sweetgrass#the red tent#orlando#i know why the caged bird sings#inga muscio#clarissa pinkola estes#women who run with the wolves#maya angelou#glenstone#crying in hmart#booklr

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

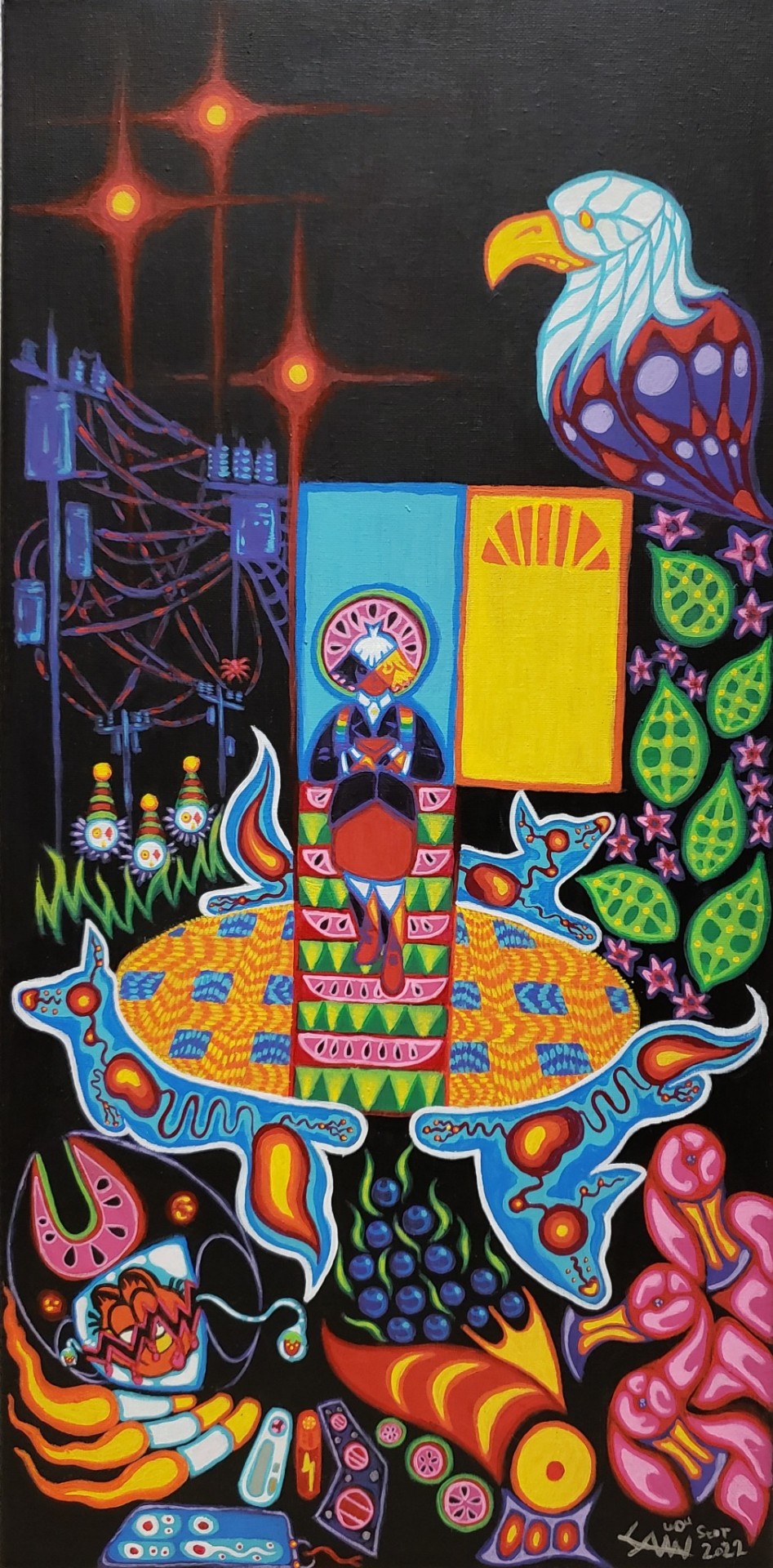

Wiské

12x24

Acrylic on canvas

Title of the work is Wiské, its for an art competition for Citizen Potawatomi Nation graduates, and my focus for this work is characters and themes from Potawatomi winter time stories. The number three is also a big theme because of Potawatomi being the youngest of the Three Fires, the others being the Ojibwe and the Odawa. I know its a bit taboo in some circles to talk about winter time stories while its not winter, but I've been told this is because the spirits will show up and I think that they'll be good guides for graduates who may be uncertain about the future!

The top of the painting has three lights in the sky and a bald eagle. Bald eagles are important because, as I learnt from our avairy, they carry messages from the Creator. Ive also been taught that unexplained lights in the sky are also messages from the Creator. These represent the Creator watching over the graduates as they enter their new life. The main figure in red is Wiské and I wanted her to reflect the graduates entry into a new life. Wiské is holding a red letter because graduation is a red letter day for many people. She is exiting a door while walking on watermelons, referencing other tribes' name for the Potawatomi being "the water melon people" due to our ancestors growing lots of watermelons. I chose this because my brother in law is Muskogee and that's what they call us. It also is a cool juxtaposition with Potawatomi meaning "people of the place of fire". The 7 seeds in the watermelon represent the 7 Grandfather Teachings. Wiské is stepping into a ring that I wanted to be a mix of a pow wow arena, a blueberry pie and finger weavings. These are to represent tradition, home, and crafts. To the right of Wiské is trailing arbetus, very important to some Potawatomi. To the left is a spider and a web of telephone wires, these make a spider web pattern. Spiders I've heard have important places in Potawatomi people's dreams, hopefully the spider will protect the graduate's dreams. Below the web is three paisek or Little People. I chose these because Native stories about the Little People are some my favorite stories. Flanking the circle is three spirit dogs. These represent Jibayaabooz, Wiské's dead brother watching over and protecting Wiské as she starts her journey. They also symbolize the graduates own ancestors watching over them. Also the dogs and the circle together make an outline of a turtle, like how in some stories our world is carried on the back of a turtle. At the bottom is a Zagma, an under water panther. I wanted this to represent things that will distract and beffudle the graduate on their journey, serving as a warning to the graduates.

#potawatomi#native#nativeamerican#nativeamericanart#nativeart#potawatomiart#nanabozho#wiské#woodlandstyle#abstract#baldeagle#underwaterpanther#medicinewheel

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

LAUSANNE, Switzerland (AP) — Jim Thorpe has been reinstated as the sole winner of the 1912 Olympic pentathlon and decathlon in Stockholm — nearly 110 years after being stripped of those gold medals for violations of strict amateurism rules of the time.

The International Olympic Committee announced the change Friday on the 110th anniversary of Thorpe winning the decathlon and later being proclaimed by King Gustav V of Sweden as “the greatest athlete in the world.”

Thorpe, a Native American, returned to a ticker-tape parade in New York, but months later it was discovered he had been paid to play minor league baseball over two summers, an infringement of the Olympic amateurism rules. He was stripped of his gold medals in what was described as the first major international sports scandal.

Thorpe to some remains the greatest all-around athlete ever. He was voted as the Associated Press’ Athlete of the Half Century in a poll in 1950.

In 1982 — 29 years after Thorpe’s death — the IOC gave duplicate gold medals to his family but his Olympic records were not reinstated, nor was his status as the sole gold medalist of the two events.

Two years ago, a Bright Path Strong petition advocated declaring Thorpe the outright winner of the pentathlon and decathlon in 1912. The IOC had listed him as a co-champion in the official record book.

“We welcome the fact that, thanks to the great engagement of Bright Path Strong, a solution could be found,” IOC President Thomas Bach said. “This is a most exceptional and unique situation, which has been addressed by an extraordinary gesture of fair play from the National Olympic Committees concerned.”

Thorpe’s Native American name, Wa-Tho-Huk, means “Bright Path.” The organization with the help of IOC member Anita DeFrantz had contacted the Swedish Olympic Committee and the family of Hugo Wieslander, who had been elevated to decathlon gold medalist in 1913.

“They confirmed that Wieslander himself had never accepted the Olympic gold medal allocated to him, and had always been of the opinion that Jim Thorpe was the sole legitimate Olympic gold medalist,” the IOC said, adding that the Swedish Olympic Committee agreed.

“The same declaration was received from the Norwegian Olympic and Paralympic Committee and Confederation of Sports, whose athlete, Ferdinand Bie, was named as the gold medalist when Thorpe was stripped of the pentathlon title,” the IOC said.

Bie will be listed as the silver medalist in the pentathlon, and Wieslander with silver in the decathlon.

World Athletics, the governing body of track and field, has also agreed to amend its records, the IOC said.

Bright Path Strong commended the IOC for “setting the record straight” about the Sac and Fox and Potawatomi athlete.

“We are so grateful this nearly 110-year-old injustice has finally been corrected, and there is no confusion about the most remarkable athlete in history,” said Nedra Darling, the organization co-founder and citizen of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation.

As the first Native American to win an Olympic gold medal for the United States, Thorpe “has inspired our people for generations,” said Fawn Sharp, president of the National Congress of American Indians.

In Stockholm, Thorpe tripled the score of his nearest competitor in the pentathlon and had 688 more points than the second-placed finisher in the decathlon.

During the closing ceremony, King Gustav V told Thorpe: “Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world.”

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the love of god read Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

It's available as an audiobook on libby, read by the author, which I highly recommend cause her voice is SO soothing.

To describe the author from her website:

"Robin Wall Kimmerer is a mother, scientist, decorated professor, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. She is the author of Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants and Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses. She lives in Syracuse, New York, where she is a SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor of Environmental Biology, and the founder and director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment."

Image description under the cut

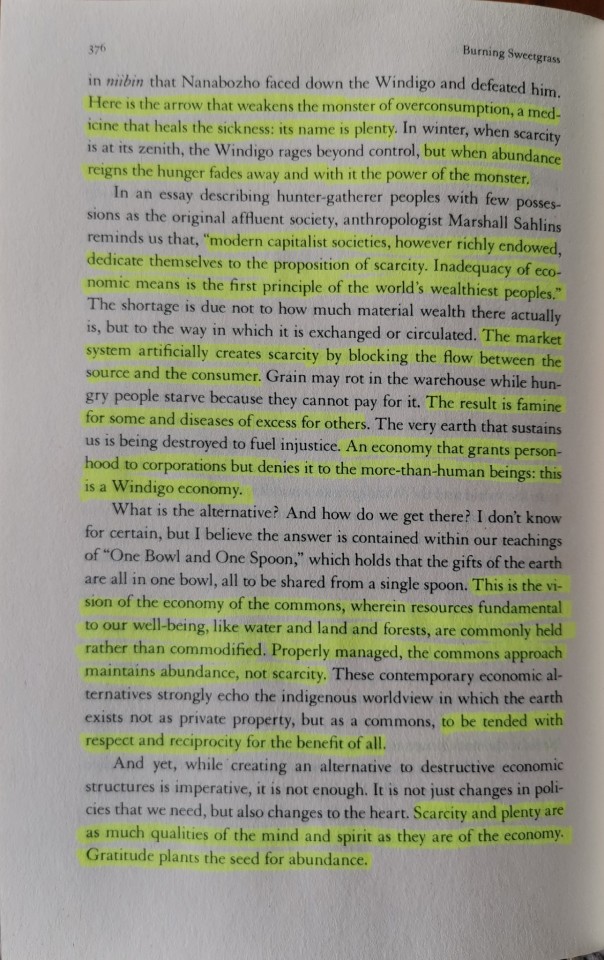

I.D.: page of a book with highlighted text, text reads:

"Here is the arrow that weakens the monster of overconsumption, a medicine that heals the sickness: its name is plenty. In winter, when scarcity is at its zenith, the Windigo rages beyond control, but when abundance reigns the hunger fades away and with it the power of the monster.

In an essay describing hunter-gatherer peoples with few possessions as the original affluent society, anthropologist Marshall Sahlins reminds us that, "modern capitalist societies, however richly endowed, dedicate themselves to the proposition of scarcity. Inadequacy of economic means is the first principle of the world's wealthiest peoples."

The shortage is due not to how much material wealth there actually is, but to the way in which it is exchanged or circulated. The market system artificially creates scarcity by blocking the flow between the source and the consumer. Grain may rot in the warehouse while hungry people starve because they cannot pay for it. The result is famine for some and diseases of excess for others. The very earth that sustains us is being destroyed to fuel injustice. An economy that grants personhood to corporations but denies it to the more-than-human beings: this is a Windigo economy.

What is the alternative? And how do we get there? I don't know for certain, but I believe the answer is contained within our teachings of "One Bowl and One Spoon," which holds that the gifts of the earth are all in one bowl, all to be shared from a single spoon. This is the vision of the economy of the commons, wherein resources fundamental to our well-being, like water and land and forests, are commonly held rather than commodified. Properly managed, the commons approach maintains abundance, not scarcity. These contemporary economic alternatives strongly echo the indigenous worldview in which the earth exists not as private property, but as a commons, to be tended with respect and reciprocity for the benefit of all.

And yet, while creating an alternative to destructive economic structures is imperative, it is not enough. It is not just changes in policies that we need, but also changes to the heart. Scarcity and plenty are as much qualities of the mind and spirit as they are of the economy. Gratitude plants the seed for abundance."

I.D. Ends

0 notes

Text

US Potawatomi Indian Reservation Population 2021

Research about US Potawatomi Populations

US Potawatomi Population 2021

All Potawatomi Tribes populations are presented from highest to lowest population base.

Citizen Band https://www.potawatomi.org/

Prairie Band https://www.pbpindiantribe.com/

Crandon https://www.fcpotawatomi.com/

Hannahville https://hannahville.net/

Pokagan https://www.pokagonband-nsn.gov/

Huron https://nhbp-nsn.gov/

Gun Lake https://gunlaketribe-nsn.gov/

✓…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Braiding Sweetgrass Quotes | Robin Wall Kimmerer

Braiding Sweetgrass Quotes. Written in 2013, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants is a nonfiction book by Robin Wall Kimmerer, a botanist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation.

0 notes

Text

Allegiance to Gratitude (Oct 31, 2023- 418.55 ppm of atmospheric CO2)

Allegiance to Gratitude is the title of a chapter in the widely discussed book by Robin Wall Kimmerer Braiding Sweetgrass- Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. In that chapter, Kimmerer, a mother, botanist, professor of Environmental Biology at SYNU and a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation introduces the Thanksgiving Address used by the Haudenosaunee…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Emotional und erfüllend: Karawane folgt dem Potawatomi Trail of Death durch Kansas

Ohne es zu wissen, überquerte George Godfrey jeden Tag den Potawatomi Trail of Death auf seinem Weg zur Arbeit. Erst als seine Stammeszeitung einen Artikel über den Pfad veröffentlichte, erfuhr Godfrey zum ersten Mal von ihm und von seiner Nähe zu ihm.

Heute ist Godfrey Präsident der Potawatomi Trail of Death Association, einer Gruppe, die den Pfad von 1838 erforscht, ihm ein Denkmal setzt und das Bewusstsein für ihn fördert.

Im Jahr 1838 zwang die US-Miliz 859 Angehörige der Potawatomi-Nation, Indiana zu verlassen und in das Reservat im heutigen östlichen Kansas zu reisen. Während der 660 Meilen langen Reise, die vom 4. September bis zum 4. November stattfand, starben mehr als 40 Potawatomi - viele von ihnen waren Kinder. Diese Zwangsumsiedlung wurde als der Potawatomi Trail of Death bekannt.

Heute führt die Potawatomi Trail of Death Association alle fünf Jahre eine Karawane an, in der die Teilnehmer diesen Weg zurückverfolgen. Dieses Jahr nahmen etwa 30 Personen teil. Die Reise begann am Montag und endete am Samstag in der Nähe von Mound City.

Godfrey gründete die Karawane 1988 zusammen mit Shirley Willard, und beide nehmen weiterhin an der Expedition teil. Godfrey, 80, ist ein Stammesmitglied der Citizen Potawatomi Nation. Willard, 86, ist Historikerin und lebt in Rochester, Indiana, in der Nähe des Beginns des Trail of Death.

Willard und Godfrey schlossen sich 1988 zusammen, um die erste Reise zum 150. Jahrestag des Trail of Death zu organisieren. Willard sagte, dass die Karawane dazu beiträgt, die Geschichte zu bewahren, Freundschaften zu schließen und "die Potawatomi wissen zu lassen, dass wir uns wünschen, dass dies nie passiert wäre".

"Ich glaube, Indiana wäre ein besserer Ort, wenn die Indianer nicht vertrieben worden wären", sagte Willard. "Wissen Sie, Indiana sollte das Land der Indianer sein, und dann haben sie sie vertrieben. Was haben sie sich dabei gedacht?"

Am Samstagmittag versammelten sich die Teilnehmer zu einem von der Stadtverwaltung gesponserten Mittagessen in Osawatomie, der vorletzten Station ihrer Reise. Die Stadt Osawatomie hat ihren Namen vom Zusammenfluss zweier indianischer Stämme in der Gegend: der Osage und der Potawatomi.

Alison Hamilton, die für die Historische Gesellschaft von Kansas arbeitet, sagte, dass die Potawatomi ursprünglich in Osawatomie untergebracht werden sollten, aber als sie ankamen, gab es die versprochenen Unterkünfte nicht. Sie wurden dann etwa 20 Meilen nach Süden zur Sugar Creek Mission gebracht, die heute St. Philippine Duchesne Memorial Park heißt und als letzte Station der Karawane dient.

Chuck und Cindy Michalski waren in diesem Jahr zum ersten Mal Teilnehmer der Karawane. Sie leben in Lake Havasu City, Arizona, und sind nach Nord-Indiana gefahren, um an der Karawane teilzunehmen. Das Ehepaar sagte, sie hätten vor ein paar Jahren von der Karawane gehört und wussten, dass sie bei der nächsten Gelegenheit teilnehmen wollten.

Cindy, die dem Stamm der Citizen Potawatomi Nation angehört, bezeichnete die Erfahrung als "sehr emotional und erfüllend" und wies auf die Bedeutung der Berichte aus erster Hand hin, die die Teilnehmer jeden Tag lesen. Wenn sie auf ihrer Reise an bestimmten Orten vorbeikamen, lasen die Teilnehmer Berichte über die Geschehnisse an diesem Punkt des Weges, wie z.B. die Zahl der neuen Todesfälle.

Ein anderer Teilnehmer, Kevin Roberts, sagte, dass die Teilnahme an der Reise "dem, worüber man liest, wirklich eine greifbare, objektive Realität verleiht".

"Wenn man diese Reise macht, weiß man, was die Menschen durchgemacht haben", sagte Roberts. "In den meisten Lagern ist jede Nacht jemand gestorben. Es wird einem bewusst, wenn man auf einer Markierung liest, dass wir mit 860 oder so angefangen haben und dass diese Zahl im Laufe unserer Reise, die 660 Meilen, immer kleiner wurde.

Roberts, der auch Mitglied der Citizen Potawatomi Nation ist, sagte, dass es am Samstagmorgen einen ganz besonderen Moment gab. Als die Autokarawane durch Johnson County fuhr, flog ein Weißkopfseeadler über ihren Weg. Für Roberts war dies kein zufälliges Ereignis. Es war ein Zeichen eines heiligen Tieres in seiner Kultur.

"Es schien, als wüsste der Adler Bescheid und wollte uns sagen: 'Ich sehe euch, und eure Vorfahren sehen euch und sind stolz auf euch'", sagte Roberts.

Originalartikel

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren

Read the full article

0 notes