#contemporary sicily

Photo

You can do politics and protest in a thousand ways. I sing. But I’m not a singer...I’m different. Let’s say, I’m an activist who makes rallies with the guitar.

Rosa on herself [my translation]

Rosa Balistreri was born on March 21st, 1927 in Licata (in the province of Agrigento) from a poor (and also alcoholic and often violent) carpenter and a housewife. She had two sisters, Mariannina and Maria, and a brother, Vincenzo (paraplegic since birth).

Since she was a young child, Rosa had to work to help support her family. She worked as a maid with wealthy families, preserved fish, and gleaned the fields of nearby villages during summer. Singing was her only enjoyment, and soon her raspy and passionate voice started to be appreciated, to the point she was hired to sing during wedding and baptism celebrations.

Around 15-16 years old, she was married to Gioacchino Torregrossa, called Iachinazzu and whom she will later describe as “latru, jucaturi e ‘mbriacuni” (thief, gambler and alcoholic). From this marriage, a daughter, Angela, was born. True to the description his wife gave of him, at some point Iachinazzu bet his daughter’s dowry and lost it. This event must have been for Rosa the last straw, so once she found out, the enraged and desperate woman stabbed her husband with a knife. Thinking she had killed him, she turned herself to the Carabinieri. As it turned out, Iachinazzu had just been severely wounded, so Rosa was only sentenced six months.

Once she served her time, she started working as a peddler, until she left her husband and moved to Palermo together with her daughter. In Palermo, she worked as a maid for a noble family. She was able to send her daughter to boarding school, while she learnt to read and write. Everything seemed to go well until the family’s young son seduced Rosa and got her pregnant. With the (false) promise of marrying her, he convinced her to steal money from his parents. Unfortunately for her, Rosa was discovered and ran away. She was nonetheless arrested and sentenced seven months. When her time was served, she was forced to live on the street until a midwife friend took her in and helped her give birth to a stillborn son.

Thanks to the intervention of Earl Testa, Rosa was employed as keeper cum sacristan of the Church of Santa Maria degli Agonizzanti, Palermo. For a while, she lived in the sacristy’s basement together with her brother Vincenzo, until the priest attempted to assault her. The woman took revenge by stealing the church’s alms-giving and with the money, she bought two tickets for Firenze, one for her and the other for her brother.

In Firenze, Vincenzo started working as a shoemaker while she resumed her job as a maid for upper-class families. The siblings were soon joined by their sister Mariannina, and their mother. The other sister, Maria (together with her children), joined them later, following a terrible fight with her violent husband. Unfortunately for Maria, her husband followed her and, once he found his wife, he killed her. Maria’s death was a huge blow to Rosa’s family, their distraught father was so desperate he hanged himself.

In the meantime, Rosa had started a relationship with Florentine painter Manfredi Lombardi. Through him, she managed to get introduced to artistic figures like Genoese art critic Mario De Michele (who allowed her to record her first album), Sicilian poet Ignazio Buttitta (who suggested that she learnt how to play the guitar and helped her with the songwriting and the composition of the music tracks), or 1997 Nobel Prize winner Dario Fo (who hosted her in the first two editions of his theatrical show Ci ragiono e canto).

Eventually, her decade-long relationship with Lombardi would end after he dumped her for a model, causing Rosa to fall into depression and attempt to kill herself. To make things worse, her daughter Angela had abandoned boarding school because she found herself pregnant and now Rosa had to provide also for her. To her rescue came her friends from the Italian Communist Party (PCI) who allowed her to perform during the various Feste de l’Unità the Party organized in various Italian cities.

She returned to Sicily at the beginning of 1970s. No longer an unknown Sicilian émigré, she came back as an accomplished artist. In 1973 her song Terra che non senti was disqualified during the XXIII edition of Sanremo Music Festival. The disqualification occurs after the RAI denounces the song via telegram as not being an unreleased track, prompting various controversies since it seemed like the real reason Rosa was banned was that the RAI was afraid that she (a known activist with Communist ideals) might use the Festival to make some dangerous social statement in front of 30 millions of viewers. By many, she’s considered the moral winner of the XXIII edition.

In Palermo she kept singing and playing in the Teatro Biondo, as well as touring the world, performing among other in Sweden, Germany, and the USA and always being celebrated.

While in tournée in Calabria, Rosa suffered from a stroke. She was hospitalised in Palermo, in Villa Sofia Hospital, where she died on September 20th 1990, although later buried in Trespiano, near Firenze. She was 63.

Rosa’s voice, her strangled singing, dramatic, anguished, sounded as if it came from Sicily’s parched earth. I got the impression of having always known her, to have seen her being born and heard her throughout my whole life: child, shoeless, poor, woman, mother, Because Rosa Balistreri is a fantastic character, I’d say a drama, a novel, a faceless movie.

Ignazio Buttitta [my translation]

Sources

Balarm, Sanremo 1973: la grande assente Rosa Balistreri, esclusa con "Terra che non senti"

Cascio Franco, Quella volta che Rosa Balistreri fu esclusa dal Festival di Sanremo

Grasso Mario, Rosa Balistreri, la cantautrice siciliana che ha vinto contro ogni mala fortuna

Meli Cristina, Rosa Balistreri, la prima cantautrice e cantastorie donna italiana

PalermoViva, Rosa Balistreri Canta e Cunta

Providenti Giovanna, Rosa Balistreri

youtube

#women#historicwomendaily#women in history#history#historical women#rosa balistreri#ignazio buttitta#palermo#province of palermo#licata#Province of Agrigento#contemporary sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#myedit#historyedit

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peter Zumthor, Saint Benedict Chapel, Sumvitg, Switzerland, 1988

VS

Unfinished swimming pool, Poggioreale, Italy, 2015 ph. Giuliano Severini

#peter zumthor#Switzerland#church#chapel#sumvitg#ruin#ruins#contemporary ruins#incompiuto siciliano#poggioreale#sicily#sicilia#italy#italia#contemporary architecture#architecture

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alessandro Turchi, Joel and Sisera (1642) / Alessandro Tiarini, Emilia, Vafrino and Tancredi (1640-50)

Jacques Stella, Judith with the head of Holofernes (1624-5)

Artemisia Gentileschi, Saint Mary Magdalene in meditation (1650)

Federica Marangoni (from Venice) / Yoko Ono

Tribute to Yayoi Kusama

Last but not least: CARAVAGGIO, Mary Magdalen grieving (1605)

Noto, Sicily~

#questa è la seconda cosa a Noto che si è presa i miei soldi#ho titubato ma non ce l'ho fatta#come fare a resistere a Caravaggio e Artemisia nella stessa mostra?#mi aspettavo di meglio perché era pure piccolina però OH#ovviamente Caravaggio mi doveva venire sfogata porkoildemonioinkuloaggiuda#art exhibition#art#Renaissance art#contemporary art#Noto#Sicily#Italy#paintings#Caravaggio#Artemisia Gentileschi#Michelangelo Merisi#Yoko Ono

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghosts of summers past

Lipari, 2023

Instagram

#contemporaryphotography#contemporary photography#photographers on tumblr#original photography#lensblr#fujifilm#original photographers#banalography#banalmag#35mm#lipari#fotografia#italy#eolie#Sicily

0 notes

Photo

Courtyard Deck in Catania-Palermo

#Deck - large contemporary courtyard ground level mixed material railing deck idea outdoor projects#deck#sicily#terrace#home improvement#gratteri

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Courtyard - Deck

#Inspiration for a ground-level#mixed-material contemporary courtyard remodel gratteri#deck#terrace#home improvement#sicily#outdoor projects

1 note

·

View note

Text

I then decided to use my grandfather's globe to create

a photo-feeling. She is taking care of the earth or better

a micro-simulation of it.

0 notes

Text

tag drop!

#ooc / asks.#ooc / misc.#ooc / psa.#v: ancient greece (345BC - 116BC)#v: ancient rome (116 - 435 AD)#v: byzantine empire (435BC - 758AD)#v: historical tbd.#v: main.#headcanons: historical.#headcanons: psychological.#headcanons: general.#dash games.#v: sicily (1500s-1867)#v: louisiana (1867-1950s)#v: contemporary (1950s-present day)#v: western.#v: dbd.#v: elder scrolls.#v: fallout.#v: tbd.#playlist.#musings.#aesthetics.

0 notes

Photo

Evsen Suleymanoglu /Turkish photographer, born in Varna, Bulgaria

Sicily

https://www.ontheroad.gr/partisipants-work/

#Evşen Süleymanoğlu#sicily#procession#cross#Evsen Suleymanoglu#contemporary photography#photography#turkish photographer#mu photo#mu#ontheroad.gr#ph blog

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Helen (Play)

Helen is a Greek tragedy by Euripides (c. 484-407 BCE). It is usually thought to have first been performed at the Great Dionysia of 412 BCE and was part of the trilogy that included Euripides' lost Andromeda. Helen recounts an unusual version of the myth of Helen of Troy in which a phantom decoy, an eidolon, replaces Helen in Troy while the real Helen awaits the end of the Trojan War in Egypt. Ever since its first performance, Euripides' Helen has puzzled and fascinated: in his Thesmophoriazusae, performed the year after Euripides' Helen, Greek comedy playwright Aristophanes would parody the “new Helen” (line 850). To this day, scholars continue to debate many aspects of Euripides' Helen, including its jarring juxtaposition of the comic and the devastating, its contemporary relevance, and its message about the nature of truth and reality.

Euripides

Born around 484 BCE, Euripides was the youngest of the three Athenian tragedians regarded as “canonical” since antiquity (the other two are Aeschylus and Sophocles). Of the 90 or so plays he composed during his lifetime, 18 survive in full (one of the tragedies transmitted under his name, Rhesus, is almost universally regarded as spurious). There are thus more surviving plays by Euripides than by Aeschylus and Sophocles put together, demonstrating that after his death Euripides soon eclipsed his two predecessors in popularity.

Little enough is known about Euripides' life, and what little information we have is obscured by fable and fancy. He was born to a family of hereditary priests on the island of Salamis, near Athens. He was said to have married twice, though both marriages ended acrimoniously. From one of his marriages, he had three sons, one of whom became a tragedian too. Above all, Euripides was reputed to have been a recluse, famously living in a cave in Salamis (which became a shrine to him after his death). Eventually, he retired to the court of King Archelaus of Macedon, where he died in 406 BCE.

Euripides is best known to us through his plays. These were performed at various festivals, chiefly the Dionysia and Lenaia, at huge outdoor theaters. Most of Euripides' plays were performed at Athens for audiences of locals and tourists, though some of his works would have been produced elsewhere: in Macedon, where Euripides spent the last years of his life, or Sicily, where he was apparently very popular. Even during his own lifetime, Euripides was known as the most adventurous and avant-garde of the great tragedians. This did not always translate to success, however. Over a career that spanned half a century (Euripides produced his first trilogy around 455 BCE and continued to compose tragedies until his death) Euripides won the first prize just four times during his life (a fifth time posthumously). On the other hand, Aeschylus was said to have been victorious 13 times and Sophocles 18. Euripides' tragedies – full of desperation, novelty, and relentless questioning – were sometimes regarded as sensational and even impious. But Euripides' fame and popularity grew after his death while that of Aeschylus and Sophocles declined. Today there are those that think of Euripides as the greatest of the Athenian tragedians.

Continue reading...

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

« First [sic] wife of Francesco Crispi. With him, she conspired for the sake of the unity of the Homeland. With him, she took part in the legendary Expedition of the Thousands. Sole woman in the immortal legion, she became its heroine. She enjoyed Mazzini’s trust and Garibaldi’s friendship. An example for Italian women of male patriotic virtues and gentle domestic virtues.»

Epitaph of Rose Montmasson, carved on her tombstone in Verano Cemetery, Rome [my translation]

Rose (also known as Rosalie and, more commonly in Italy, Rosalia) Montmasson was born on January 12th 1823 in Saint-Jorioz, a small village in the Haute-Savoie region, at that time still part of the Kingdom of Sardinia. She was fourth of five children and her parents, Gaspard and Jacqueline Pathoud, were humble farmers. As a child, Rose helped her parents both at home and in the fields, and received a simple education, she learnt to write, read and do maths.

In 1840, the death of her mother, aggravated the already unstable economic conditions of the family, forcing Rose to move to the more economically vibrant Torino in search of a job. Starting 1849, she worked as an ironer and, through her job, she met the Sicilian patriot and lawyer, Francesco Crispi (1818-1901). His first wife, Rosina D’Angelo, had died in 1839 due to complications in childbirth, after two short years of marriage. The baby, Tommaso, died a couple of hours later and, five months later, mother and son were followed by 2-years old Giuseppa, Francesco and Rosina’s first child. Following his wife and children’s deaths, Crispi became romantically involved with a Felicita Vella (called Ciuzza), with whom he fathered a son, Tommaso. Because of his liberal and democratic ideas as well as his active participation in the Sicilian revolution of 1848, Francesco Crispi had been forced to exile and his first destination was Piedmont.

Having met because Rose used to iron Francesco’s shirts, they started living together in 1850. Unfortunately, their cohabitation was soon disturbed when Felicita Vella moved into the same neighbourhood. Indeed, the scorned woman started harassing the couple, arriving to report Rose for mistreating young Tommaso.

Following the failed anti-Austrian uprising of 1853 in Milan, Crispi was once again forced to exile. He reached Genova and, from there, he sailed for Malta, where he was joined by Rose. On December 27th 1854 the two got married. Since, for the nth time, Francesco was compelled to abandon his asylum, they didn’t have enough time to plan the wedding and couldn’t, in that short time, provide the necessary documents. Because of this, no priest was willing to celebrate the wedding, until they convinced (for a fee) a wanderer Jesuit, Luigi Marchetti, to perform the ceremony. Only later, it would turn out Marchetti (who was also a patriot) had been previously interdicted and suspended a divinis, and this would later bear tragic consequences for Rose.

Three days later, Crispi sailed for London, while Rose stayed in La Valletta, waiting for the act of marriage to be registered in the parish of St. Publius and for the notary’s endorsement of the certificate. She then set out to join her husband in England, stopping at Saint-Jorioz to announce to her family she had finally got married (her father and siblings didn’t approve of her living together with a man who wasn’t her husband). At the beginning of 1855, she was finally in London. In the British capital, Rose navigated between befriending many of the fellow Sicilian exiles and patriots (like Giuseppe Mazzini) and taking care of her husband. As Tina Scalia (daughter of a couple of those refugees) would put it: to Rose wifely love consisted in being for Crispi “a cook, a laundress, and an errand girl”. Her devotion for her husband and his cause went beyond her household chores. The brave woman put her own life in danger by acting as a connection between Mazzini and his followers in France and elsewhere. She secretly conveyed his messages, plans and instructions, hiding the papers in haunches of game and smuggling them past customs officers and gendarmes. In 1856 the Crispis moved to Paris, and there Rose devoted herself to the logistical coordination of the Italian clandestine network. She didn’t even neglect to look after Francesco’s recently orphaned nephew, Felice Caratozzolo (son of Anna Serafina Crispi, also called Marianna), who had just reached Paris at the wish of his uncle, who wanted to provide the teen with a better future. Because of Francesco’s frequent trips, Rose found herself often alone. Felice proved to be an unruly kid, with no respect for rules and who didn’t acknowledge his aunt’s authority. At some point he even left the house and came back only when his uncle returned from his trip, and managed to convince his nephew to come back home. Luckily for Rose, her partner took her side when Marianna Crispi (who clearly only got her son’s side of her story) wrote his brother a letter lamenting her son’s mistreatment at the hands of Rose. Francesco answered that his wife took by heart the idea of taking care of Felice as he was her own child, spurring him to study and behave. Moreover, since she loved and feared her husband, she would have never done something which would have enraged him like mistreating Felice. As for Francesco, he regretted never having hit his nephew as it would have done him good.

In 1858, the Crispis, together with young Felice, had to leave France since Francesco had been suspected to be in league with Felice Orsini (the Italian patriot who had tried unsuccessfully to assassinate Napoleon III the year prior). They went back to London where he got again in touch with Mazzini. 1859 marked a turning point in Crispi’s patriotic experience. The Kingdom of Sardinia, together with Napoleon III’s France, had defeated the Austrian Empire. The Austrians had ceded Lombardy to France, whom, in turn, passed it to Sardinia. The year after Sardinia had exploited the situation and annexed the Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Parma, the Duchy of Modena and Reggio, and the Papal Legations. Nice and Savoy were ceded to France as compensation for assisting the Sardinians. The outcome of the Second Italian War of Independence had suggested Crispi that, unlike what Mazzini (and Crispi with him) had advocated, perhaps Italy’s future was monarchic rather than republican.

From London the Crispi couple moved to Torino and Genova. In July 1859, Crispi reached Messina incognito, convinced that he could arrange an anti-Borbonic revolt with the support of the Sicilian mazziniani. The uprising (planned for October 4th) was delayed indefinitely. This convinced Crispi that a future revolt in Sicily needed the support of the population rather than committees and that a military expedition was fundamental to back up the insurrection.

In order to plan this uprising, in March 1860, Rose embarked on a steamboat headed for Messina to get in touch with Sicilian patriots Rosolino Pilo and Giovanni Corrao. She reached Malta to meet with fellow patriots Nicolò Fabrizi and Giorgio Tamajo with whom she exchanged information and letters she took with her when she returned to Genova.

Two months later, Rose embarked on the steamboat Piemonte headed once again for Sicily, the only (official) female member of the Expedition of the Thousand. Her husband had been against her participation, while Garibaldi, despite the initial veto, had given his consent (“Come then, if it pleases you. However bear it in your mind that you’re putting yourself in great risk and peril, and I won’t answer to it”). In Sicily, armed with a gun, she risked her life to fight in Marsala, Calatafimi and Palermo. She also helped tend to the injured soldiers, quickly becoming a familiar and dear figure. The Sicilians quickly renamed her Rosalia, after St. Rosalia, the much beloved saint patron of Palermo, and with this name, she would be remembered.

If Rose thought the desired and fought for the Unification of Italy in 1861 would mark the beginning of a much happier and more secure future, she quickly realized how wrong she was. The only one who benefited from it was her husband. The couple moved back to Torino and then Firenze, where they spent their last period of relative happiness. In 1861 Francesco was elected deputy of the Parliament of the newborn Kingdom of Italy (and would later become one of its Prime Ministers) and quickly turned his back on his republican ideal becoming a staunch monarchist. Rose (as well as many of his old friends) must have seen it as a betrayal and it must have made their relationship even rockier. Crispi didn’t just betray her in terms of shared political ideals, but also in more personal terms. He had various flirts with women much younger than his wife and even fathered illegitimate children with them. He reached his worst in 1878 when, after repudiating Rose (claiming their Maltese marriage was irregular), he married Filomena (Lina) Barbagallo, with whom he had a child five years prior. This caused such an uproar (and the accusation of bigamy) that, during a public event, Queen Margherita refused to shake his hand. As it came to light the fact that brother Luigi Marchetti, who had performed the wedding ceremony, had been interdicted and thus Rose and Francesco’s marriage was null.

The betrayed woman moved to a modest house in Rome, where the couple had previously moved when the city was declared Capital of the Kingdom in 1871, and the whole court had moved there.

Rose spent the last part of her life in financial hardship, economically helped by her friends. Through common friends, Agostino Bertani and Giorgio Tamajo, she reached an agreement with her former husband, who agreed to pay her a life annuity. When Crispi died in 1901, Rose (as a former Garibaldina) was offered a meagre Royal pension, who allowed her to live her last couple years in semi poverty.

Rose Montmasson died in Rome on November 10th 1904 after suffering from a stroke. She was 81. Since she couldn’t afford it, she was buried in a simple grave, freely granted by the Campo Verano Cemetery. According to her wishes, she was dressed up with a red shirt (symbol of the Thousands), and her medals were displayed on a pillow placed before her coffin. Her funeral (a secular ceremony) was attended by many Garibaldini, and people she had personally helped during the Expedition, but no representative (except from Senator Francesco Cucchi, who had personally known her during the Sicilian adventure) of the Nation she had helped made.

Sources

- CASALINI Fabio, Rosalia Montmasson, l’unica donna tra i Mille di Garibaldi

- FERRI Marco, Rosalia Montmasson;

- ODDO Giacomo, I mille di Marsala: scene rivoluzionarie;

- PAGLIUSO Antonio, Rosalia Montmasson: la Storia dell’unica Donna tra i Mille di Garibaldi;

- PALADINO Francesco, Crispi, Francesco;

- PALAMENGHI CRISPI Giulio, Rose Montmasson;

- Rosalia Montmasson;

- Rose Montmasson Crispi;

- ZAZZERI Angelica, Montmasson, Rosalie

#historicwomendaily#women#history#women in history#historical women#rose montmasson#francesco crispi#giuseppe garibaldi#spedizione dei mille#contemporary sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#myedit#historyedit

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Athenaion | Cathedral of Holy Mary's Nativity, Syracuse, Italy,

5th century BC | 1725-1753

VS

Michael Heizer, Negative Monolith #5, 1998

#Athenaion#column#ancient greece#magna graecia#sicily#Syracuse#unesco world heritage site#world heritage#world heritage site#italy#italia#barocco#baroque#andrea palma#Michael Heizer#art#contemporary art#dia beacon#new york#land art#land artist

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

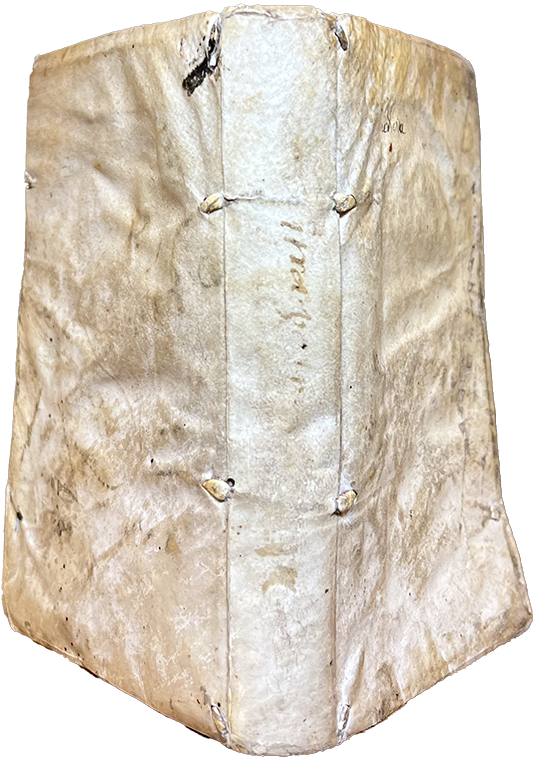

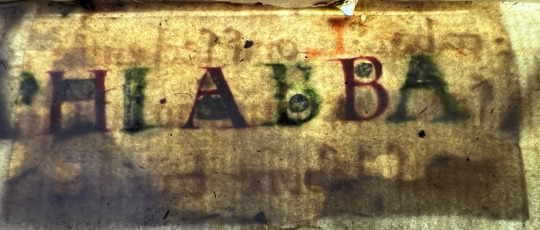

Special Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room

Hardin Library of Health Sciences

INGRASSIA, GIOVANNI FILIPPO (1510-1580). Iatrapologia: Quaestio, quae capitis vulneribus ac phrenitidi medicamenta conveniant [Defense of Medicine: Question regarding the medicinals convenient for head injuries and meningitis]. Printed in Venice by Giovanni Griffio, 1547. 16 cm tall.

This month's book was one of six John Martin Rare Book Room items selected to be scanned as part of the Iowa Initiative for Scientific Imaging and Conservation of Cultural Artifacts (IISICCA) project. Iatrapologia (Greek: "defense of medicine") by Giovanni Filippo Ingrassia (1510-1580) was selected for two reasons. One, with backlighting through the thin, limp vellum cover, we were able to determine it had small pieces of manuscript waste that included both green and red inks. Different inks show up at different energy levels in Computed Tomography (CT) scanners - or sometimes not at all. Finding a variety of inks helps to calibrate both types of scanners used in the project.

And two, it's just a darn cool book.

Ingrassia was an influential 16th-century Italian physician. He grew up in a well-educated family and received a classical education. He studied at the University of Padua, one of the most important western centers for the study of medicine and anatomy.

There, he learned from renowned intellectuals and physicians, such as Realdo Columbo, Bartolomeo Eustachi, Girolamo Fracastoro, and, of course, the Anatomaster® himself, Andreas Vesalius. Ingrassia would go on to make his own significant impact on not only anatomical medicine but also public health and hygiene, forensic medicine, and teratology (the study of abnormalities of physiological development).

After completing his studies in 1537, he became the personal physician to a minor Italian noble family in Palermo. Soon after, he became the professor of human anatomy at the University of Naples. It was during his time in Naples that he wrote Iatrapologia. Ostensibly a book about how to treat head wounds, it was also a critique of the current state of medicine and surgery - one of the subtitles, liber quo multa adversus barbaros medicos disputantur, translates as "a book in which many things are argued against the barbarian physicians."

In Iatrapologia and elsewhere, Ingrassia argued that medicine should be considered a less subjective discipline. Treatments should be verified, results checked, and useful diagnoses disseminated among physicians. He also thought that physicians and surgeons should be integrated into a single profession to prevent surgeries by "unqualified" people. Indeed, in Iatrapologia, he states rather dramatically,

"Oh, God, so much human suffering has been caused by the vainglory of contemporary doctors. Indeed, surgery has been abandoned to some inexperienced, empiric [i.e., quack] physicians, most of whom are not only lacking in dogma, but also in what relates to the Art." p. 252

Ingrassia was also a strong believer in continuing education, suggesting physicians should refresh their dissection skills every five years so as to avoid becoming "imperfect and ignorant physicians." If nothing else, Ingrassia demonstrated a natural skill with insults!

Ingrassia made significant contributions to the field of anatomy, particularly with bones and the skull. He is most well known for identifying a third small bone in the middle ear, which he called the "stapes." He also described differences between human and animal bones, breaking down parts of each bone to make identification easier.

Ingrassia was not only a physician and anatomist but also a pioneer in public health. He held various political positions, most notably Protomedicus (chief physician) of Sicily, and implemented measures to prevent the spread of diseases such as malaria and the plague. He emphasized the importance of preventive measures, such as isolating infected patients and cleaning objects to reduce the risk of transmission.

Overall, Giovanni Filippo Ingrassia was a remarkable physician and scientist who significantly contributed to our understanding of human anatomy and the practice of medicine.

Our copy of Iatrapologia is a delight to hold and leaf through and, as indicated, holds a few secrets inside. The limp vellum cover is soft but dried out enough that it has a bit of a rattle while opening. The cover image above shows discoloration from use and bits of writing here and there. The textblock is in excellent shape, the paper bright, and almost completely free of damage.

One interesting surprise is a piece of paper that has been pasted over the verso side of leaf A3 in an attempt to cover up a printer's error (a repeated page from elsewhere in the book). At some point, someone made a concerted effort to remove the paper to see what was underneath. Whoever glued it on, though, made sure the vandal couldn't remove much!

Other surprises can be seen in the images above. The images show close-ups of the text visible with backlighting. In one image, green and red inks are still vibrant and really jump out. The IISICCA group estimates the date of the manuscript to be roughly the 10th or 11th century and suspects the complete word is some form of "archiabbas" (chief abbot).

Another image shows a small scrap where the photo is repeated several times. Different photo filters were applied in an attempt to make the text more legible.

Contact me to take a look at this book or any others from this or past newsletters: [email protected]

#medicine#medical history#rare books#library#special collections#history#uiowa#Giovanni Filippo Ingrassia#public health

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

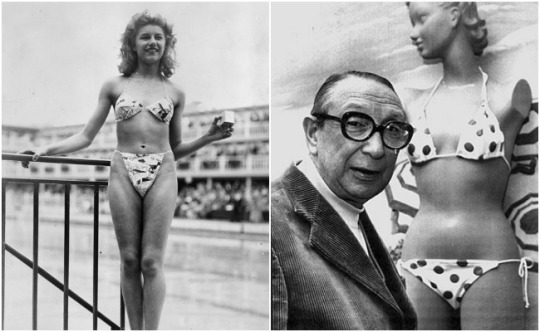

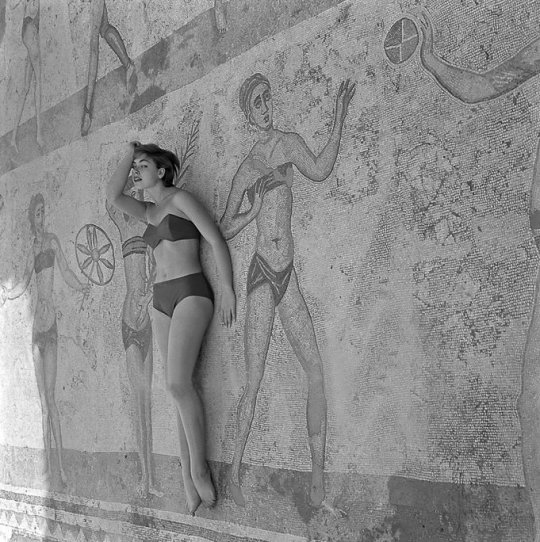

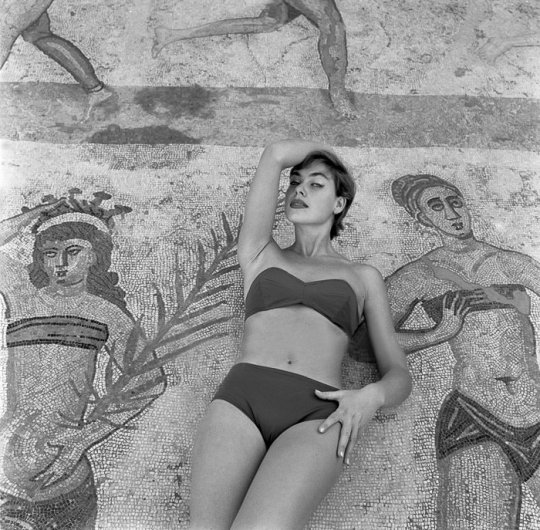

The bikini is the most important thing since the atom bomb.

Diana Vreeland

The origins of contemporary bikini day may be traced back to a French engineer, a Parisian exotic dancer, a nuclear testing site in the United States, and a postwar fabric shortage.

In 1946, Western Europeans joyously greeted the first war-free summer in years, and French designers came up with fashions to match the liberated mood of the people. Two French designers, Jacques Heim and Louis Réard, developed competing prototypes of the bikini. Heim called his the “atom” and advertised it as “the world’s smallest bathing suit.”

French fashion designer Louis Reard was determined to create an even more scandalous swimsuit. Réard's swimsuit, which was basically a bra top and two inverted triangles of cloth connected by string, was in fact significantly smaller. Made out of a scant 30 inches of fabric, Réard promoted his creation as “smaller than the world’s smallest bathing suit.”

Réard claimed that the bikini was named for Bikini Atoll, the site of nuclear tests by the United States in the Pacific Ocean.

Louis Réard's bikini was so little that he couldn't find anyone brave enough to wear it. After being rejected by a number of fashion models, he came across Micheline Bernardini. She was a 19-year-old nudist at the Casino de Paris who consented to be the first to try on his daring bikini. Michelle Bernardini debuted this revealing costume at the Piscine Molitor in Paris during a poolside fashion show, and it revolutionised swimwear on 5 July 1946. The bikini was a hit, especially among men, and Bernardini received some 50,000 fan letters.

Before long, bold young women in bikinis were causing a sensation along the Mediterranean coast. Spain and Italy passed measures prohibiting bikinis on public beaches but later capitulated to the changing times when the swimsuit grew into a mainstay of European beaches in the 1950s. Réard's business soared, and in advertisements he kept the bikini mystique alive by declaring that a two-piece suit wasn’t a genuine bikini “unless it could be pulled through a wedding ring.”

But it really took when what we would call cultural influencers took to it. It was in 1953, thanks to Brigitte Bardot, that the bikini became a "must-have" and the history of the bikini became historic, when she was photographed wearing one on the Carlton beach at the Cannes Film Festival. She also wore one in 1956, in the film "Et Dieu… créa la femme".

The United States also caught on to the trend, as it was only two years later that Ursula Andress posed in a white bikini on the poster for the James Bond film, Dr. No. The poster created a considerable marketing coup, and women adopted the bikini. According to a study by Time, 65% of younger women adopted the bikini in 1967.

There is no question the bikini is hardly modern. Many think they date back to ancient Roman times because of the murals uncovered in excavated ruins in Sicily. This isn’t really true.

Despite the celebrated images from the mosaics in Piazza Armerina, of the ancient Roman girl wearing what looks like a bikini, the answer is, “not really”. The ancient Roman girls weren’t even first to wear what to our eyes looks like a bikini. However, the fact that we seem to find “bikinis” in ancient depictions should make us rethink our hubristic bias that we in modern times have invented everything and that people in ancient times didn’t know how to live.

Archaeologists have found evidence of bikini-like garments that date to as far back as 5600 BC. That’s roughly 5000 years before the Romans did so. In the Chalcolithic era of around 5600 BC, the mother-goddess of Çatalhöyük, a large ancient settlement in southern Anatolia, was depicted astride two leopards while wearing a bikini-like costume.

Two-piece garments worn by women for athletic purposes are depicted on Greek urns and paintings dating back to 1400 BC. In fact, even just the notion that women participated in sports in the ancient world should make us sit up and take notice.

Today we tend to imagine women in the ancient world as being practically sequestered in their homes, spinning, weaving and having babies. But this is a gross oversimplification of their role.

Active women of ancient Greece wore a breast band called a mastodeton or an apodesmos, which continued to be used as an undergarment in the Middle Ages. While men in ancient Greece abandoned the perizoma, partly high-cut briefs and partly loincloth, women performers and acrobats continued to wear it.

In the famous mosaics to be found at Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Armerina, the girls who seem to be wearing the “bikini” are Roman and the so-called bikini had already been around for at least 5,000 years by then. In the artwork “Coronation of the Winner” done in floor mosaic in the Chamber of the Ten Maidens (Sala delle Dieci Ragazze) in Sicily the bikini girls are depicted weight-lifting, discus throwing, and running.

The bikini was gradually done away as Christianity became more influential as the centuries wore on. Christian attitudes towards swimming restricted the clothing of women for centuries, the bikini disappeared from the historical record after the Romans until the early 20th century with Louis Beard’s re-invention of the two piece bathing suit as the ‘bikini’.

Photos: In 1956 Emilio Pucci designed this bikini inspired by the mosaics of the Villa Romana Del Casale in Sicily.

#vreeland#diana vreeland#bikini#femme#history#fashion#style#woman#louis reard#bathing suit#beach#ancient rome#ruins#inspiration#ancient world#bikini atoll#atomic bomb#paris#italy#sicily#culture#society

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

The myth of Plutos and Proserpina is a story that has been through multiple major misinterpretations. People often spread wrong information about it or subject it to unhealthy modernizing under different reasonings, so I decided to create a masterpost of sorts regarding everything that concerns the story of abducted Proserpina and wrathful Demeter.

I am covering all possible variations of the myth that I could find, including the Roman, Greek, and the Sicilian one, as Proserpina is often said to be native to Sicily; or her abduction story happens there. These stories present the myth in the variety of interpretations that can't be ignored regardless.

There's no "right" or "wrong" way to read the actual story, nor is there any morally correct one.

The origins of the Goddess Proserpina may lay in Sicily, which was colonized by Greece in the 8th century BC thus resulting in a lot of Sicilian traces of the story being lost. The local version of the myth isn't spoken about much, as it is overshadowed by the Greek narration, though I do find it fascinating and I believe we can't overlook it.

The Sicilian version of the myth does portray the descent of a girl named Proserpina (from proserpere, "to creep forth" - about growing grain) in the Underworld. There are multiple stories on how She ends up in the realm of the dead, none more correct than others: some say that She wanders in Plutos' realm on Her own accord, following Her own sense of curiosity as She sees a beautiful narcissus growing. Some say that He does take Her, but allows Her to leave when He sees Her distress and learns of Her Mother's worry. Some sources say that She is allowed to leave on Her own whereas some sources claim that Plutos needs to be negotiated with first. The nymphs are said to accompany Her in some stories whereas in some She is completely alone. The nymph Cyane, notably, is sometimes said to even protect Proserpina from the God.

I believe for some examples of the Ancient consensual myth, you may look into Lokri reliefs.

Regardless, down there, having met the God of the Dead who is fascinated with Her, She is faced with the choice to leave or to stay, and She decides to leave. As She passes through the gardens in the higher layers of the Underworld, alone or with a guide, right before She can leave, She grows curious and tastes a pomegranate, swallowing six seeds. It is believed that eating anything in the realm of the dead gets you trapped in there, and that's what happens to Her.

Proserpina is not forced to stay by Plutos Himself, but She has to stay as Her own curiosity and carelessness get Her trapped under the soil. From that point on, She can only leave for the warmer part of the year and come back for winter

Some stories of the region depict the motif of trickery but it is not as widely prominent as within the contemporary Greek myth.

Diodoros and others see Sicily as the place that first witnessed the manifestation of the Goddess, who gave the people of Sicily wild wheat.

In Sicily, Proserpina was known as Dea di Siciliani, the Goddess of the Sicilians, as mentioned by Apuleius. Sources point out that Her cult greatly resembles that of the local Italic pre-Greek Goddess Primigenia, though much information has been lost. It is possible that Roman Ceres or even Cybele acquired Proserpina-Primigenia's attributes.

Initially, Proserpina was depicted very similarly to the Goddesses Demeter and Hekate, which possibly demonstrates Her agricultural qualities as both of these Deities posses such aspects. Proserpina in Her original depictions carries a torch, perhaps to light Her way in the Underworld the way souls of the dead do, and to represent the connection to agrarian culture.

The "violent version" of the myth of Plutos and Proserpina is a later invention. Authors such as Hesiod in his Theogonia depict the Goddess Persephone, born to Zeus and Demeter only to be later carried away by Plutos.

Depiction of Death as a brutal act of taking is something common in Greek myths where both Plutos and Charon are portrayed riding a chariot and a black mare respectively, moving fast and taking the souls of the dead. Charon has been said to wield a sword and firmly grab the souls one by one, too.

Sicily, to which the cult of Plutos is native, has never portrayed Him as a brutal and unfair King, but rather accepted Death as inevitable even if terrifying the living.

The Greek version of the myth includes violent kidnapping of Proserpina, either via Plutos grabbing Her and taking Her away immediately, or by driving past Her in a chariot tugged by four horses, grabbing Her, and taking Her down. Sometimes He is said to lure Her in with a flower, as She was a curious girl.

Proserpina in the Greek version of the story spends some time in the Underworld, held back by the God. Some stories say that She is there for nine days, some mention a shorter time period. Regardless, during that time, Her Mother Demeter mourns, looking for Her child, and makes cold weather and famine come onto the people.

Zeus, the Sky-Father, is then the one to send messengers or Hermes/Iris to visit His brother and bargain, looking for ways to negotiate with His sibling. Plutos agrees to let the girl go, but right before She leaves, She is forced to eat the fruits of the Underworld during a feast He prepares for Her. In some stories, She does so out of hunger whereas in some, She is tricked into thinking it is safe to do so. Regardless, the Greek myth paints the picture of force, brutality, and deception.

Romans already had their local Goddesses of agriculture, death, and rebirth when the myth of Proserpina came from the far South of the Empire. When the Sicilian Goddess became known to Rome, She quickly merged with the local Deity known by the name of Libera, a female equivalent of another Roman God, Pater Liber. Libera was also once an Italic Goddess, brought into Rome in its early Republican years.

Libera had Her own rituals, rites, holidays, and otherwise presence in the Roman routine life. And while this Goddess has quickly absorbed Proserpina, the latter was still respected as a separate Divinity outside of Rome, in Her place of origin. Roman authors recognize Her as a Sicilian Goddess even if She wasn't prominent in Rome.

As the result of proximity to colonized Sicily and its Italic past, Rome knew of multiple versions of the myth. Writers of the time mention both the Greek, violent, interpretation of the story, and the Sicilian origins of the Goddess and Her myth. For example, in Titus Livius times, we find pieces of Ancient Latin writing that mention both the Eleusinian Mysteries and Misteri di Proserpina. Southern Italian texts speak of the Stygian Proserpina, associated with the cycle of death and rebirth. Rome didn't seem to have a preferred version of the story, as closeness to both Sicilian peoples and Greek borders made it so the Roman Empire became the place where both stories had left an impact. Claudian, for example, spoke on the kidnapping of Proserpina while Ovid referred to Her as a Goddess to be respected (Regina Erebi) while Homer, whose story was known in Rome, called Her "terrible, silent Queen of the Dead".

Regardless of what myth version you decide to follow and believe in, it's important to remember that the myth itself is less so about Proserpina and Plutos, but more so about Demeter, or Ceres.

The wrath of the Goddess is something the Ancients feared. Orphic hymns to Demeter mention Her fury, and many inscriptions of the time paint Her as the Goddess who was incredibly loved by the people while also being terrific in Her anger.

The people of Sicily and Southern Italy, who were among the first to have accepted the cult of Demeter, spoke of Her as a highly respected Goddess terrible in Her rage.

The story of Proserpina can't be analyzed without looking at the figure of Demeter, as She plays a major role in the myth.

Most of the versions speak of the Goddess, enraged and mourning, descending from Mount Olympus and walking among the mortals with a torch in search of Her daughter. She walked far and reached Eleusis, where She hid among the young virgin girls before unveiling Herself and requesting establishment of Her temple and cult in the city. Some say She was testing the local King to see how he'd accept a foreigner. Some say She was watching the local community of young girls before becoming their local protector. It needs to be said that some sources claim that Proserpina's absence made Her mother go on without water and food, the period of abstinence that ended with Her accepting kykeon - strange nutritious mix made of barley flour, water, and mint.

To find Her daughter, the Goddess is said to have requested help of Hekate who helps find one's way in the dark, and Apollo who sees it all from the sky. Some sources mention that prior to the whole event, Astreios, the God of prophecies delivered through astrology, tells Her a prophecy of Proserpina's kidnapping and following birth of Zagreus.

Lastly, the Goddess deals with Zeus who Demeter was enraged with as He allowed the girl to be taken away. Zeus is said to agree to help Demeter after She lays fields barren and leaves people famished, refusing to take up Her Divine duties until Proserpina is back to Her. Hermes is then sent off to negotiate, as He is the God of communication, and He manages to get Plutos to let the girl go. However, here is where the story branches out: some say that She tastes the fruits of the Underworld without Him forcing Her to, some that She is given the seeds/a seed by force, and some that She takes them without knowing what they do - only finding out after the fact when Demeter inquiries if She ate the fruits of the dead.

Many sources speak on Demeter's self-imposed exile as She did not want to share Olympus' plane with other Gods after learning that Zeus allowed Her beloved daughter (in some myths, Her only child) to be taken by Plutos. She spends Her exile in Eleusis, where kind maidens help Her, disguised, and for that She allows Them to built Her a temple, a cult, and, in some myths, returns life into nature, letting crops grow again.

In some versions of the myth, it's Rhea who convinces Demeter to come back, in some it's Iris or Hermes serving as messengers. There are also versions that say Demeter never returns to Olympus, preferring to wander the Earth.

Lastly, the ending of the story differs from source to source, but all equally portray the mother's dismay at having Her child no longer fully in Her care. Sometimes Proserpina is said to have to spend a third of the year underground, sometimes half the year. Some sources speak on Her being guided out of the Underworld by Hermes or Iris, some mention Hecate as Her mistress and patroness. Demeter is said to question whether or not Her daughter has tasted the fruit of the Underworld, and when She admits to it, the mother is in disarray as She realizes Her child is now bound to the soil.

Some sources, such as Pausanias, also speak on Demeter Herself being either assaulted by Neptune or held back by Him while on the search for Her daughter. Some equate Her with Rhea in the myths of Rhea being assaulted by Zeus in the form of a serpent (or dragon). It's important to note that not even all Greek sources believe these stories to be true, so take them as local versions that didn't make it into commonly spread story.

That, with layers of other events such as Her establishing Her Mysteries, multiple cults, and conversing with many Gods on the matter of Proserpina, are signs that the myth is largely a story of a Mother and a Daughter, and not a story of Proserpina and Plutos per se. Marriage did, after all, mean separation of the girls and their mothers, at least in the Ancient world.

The multiplicity of myths of Proserpina might have something to do with how many possible origins of the Deity there are.

In Greece and colonized Sicily Proserpina, Greek Persefona, was known as a Goddess of grain and agriculture, tightly associated with Her mother. In this version of the story, She is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. Other than that, the Greeks and Sicilians either believed Her to be the daughter of Demeter and Poseidon, or daughter of Styx. As the Stygian Goddess, venerated in Sicily, She was seen as a punishing force.

Locality of the cult is a matter of many discussions as we have found evidence of there being local cult establishments in Eleusis, Ermione, Feneo, Arcadia, Knossos, Enna, Ipponio, and Syracuse. It might have been established in the Ancient province of Morgatina, Lake Pergusa, and more.

In Sicily, the Goddess had a cult connected to agriculture and marital ceremonies. For examples, theogamy, marriage to a God, and anacaliptery, gifts to the newlyweds, were common rituals to honor Her. These were festivals celebrated in summer and winter, too.

Most sources say that the origin of Proserpina is Sicily, some claim it's the South of Italy, in the region of modern Taranto (Tarentum back then). Some sources say that after creation, the word about the Goddess first came to the province of Apulia, and then was introduced to Rome. Some believe it is pre-Greek, which is most likely, and some believe it is a Greek mythological concept.

Sometimes Proserpina is seen as the mother to multiple other Gods, including Zagreus (sometimes Dionysus), whom she is said to bear from Zeus and, in some myths, disguise the identity of after. Some hymns refer to Her as the "origin of Furies" and give Her the title of Eumenidos, vengeful one.

Persephone, Perifone, Perrefassa, Proserpina: these are just some of the names which the Greeks and Romans call an ancient Divinity linked to the rural world and the Underworld. The etymology of the name is uncertain, but is certainly pre-Greek. Her cult is also very ancient: in many places in the Mediterranean She is invoked as signora dell’oltretomba (lady of the underworld) or as la pura (the pure one). Plato, for example, notes that the Greeks changed a name of a pre-Hellenic Divinity, Perephatta, into Persefone as "they could not pronounce it". Mycenaean votive tablets suggest that the Goddess we now know as Proserpina was there before the myth of Persefone was created.

From the religious perspective, it is possible that Proserpina is a standalone, separate Deity. However, it is also possible that She was but one of the "faces" of existing Goddesses. We can speak of Libera, Primigenia, Ceres/Demeter, and even the mythical wife of Soranus, an Etruscan God of the Dead, as possible Deities to be mistaken for Proserpina.

Because there were so many Goddesses who completely encompass Proserpina's attributes and who have existed before Her cult came around, it's possible that She was a reimagination of one of the state cults. It is possible that Proserpina's myth was a political rather than religious invention because we can see that the general state of Athens did not seem to look kindly at the cults born in Sicily and Rome. Examples of this can be seen in Plutos, Mars, and Bacchus. While this is not a fact, it is a possibility.

It isn't only in Italy that this Goddess might have been but another face of an older Deity. In Greece, this might have been the case too. When referring to Demeter and Persephone, the grammatical form authors use is that which means "double Goddess" (τώ θεώ) rather than "two Goddesses" (αί θεαί).

It is completely possible that Proserpina and Demeter are the same person viewed as an allegorical set of "stages" of one's life: mature and young grain. The names of the Goddess(es) suggest trinity too: Kore (the maiden, Youth), Demeter/Ceres (the Abundant, the Mother), and Proserpina (the destroyer, Death).

After all, the stages of life as seen in the myth are parts of the natural process of aging and seasonal change in nature.

The myth of Proserpina, like any other myth, doesn't have to be taken literally. A lot of mythological stories are either cautionary tales, stories made for entertainment, or allegories to explain natural processes. Proserpina might just be a way to explain why seasons had to change, and viewing seasonal shifts through the coming of Death was something done in many cultures across the world.

It's natural for the Ancient people to view it from the standpoint of Death being unfair and cruel, too. After all, Ancient towns heavily relied on local production for survival, and losing precious grain meant a period of famine, if winter came earlier or was colder than usual, or simply strict abstaining.

Regardless, even in Antiquity Proserpina might have been more so a symbolic Deity rather than a votive figure. Alternation of summer and winter seasons and falling of nature into temporary sleep and stagnation are some of the aspects of this symbolic interpretation. Because of Her name, She was also symbolically associated with motion of growing grain that slowly crept out of the soil and towards the Sun. Interestingly, wheat was stored in containers underground, which could symbolically appease Proserpina.

Her name, sounds very much like Greek "φέρειν φόνος", which is its possible etymology as it means “bringing Death”.

We don't know much of the Eleusinian Mysteries, but some sources suggest that in Athens, the allegory of seasons changing was turned into a staged play where re-discovery of the daughter by the mother was annually performed. We only know that it involved a solemn procession that would arrive in Eleusis at night, carrying torches, and enter a cave where one of the Doors of Dis was located. Here, the "initiated ones" would perform a ritual that remains a secret even now.

Long before Eleusis gained its own cult, the rites of currently still mysterious Thesmophoria were known to the Ancients. It might have included some rituals by matriarchal communities of local women.

Some more needs to be said about how the story within this myth fits into what the Ancient peoples considered to be a natural flow of events. Plutos wasn't the only one to attempt to marry Proserpina: Apollo offered Her the island of Delos and Mars offered her the mountain range of Rhodope. However, it is Death that claimed the Maiden. Some stories suggest that Jupiter, who was Proserpina's Father, agreed to the kidnapping.

It's clear that the myth wasn't just taken directly as it is, but was also seen as a way of entertainment, as a votive subject, and a symbolical tale to describe a common natural phenomenon.

I believe it's important to note that there's no right or wrong way to view the actual myth.

For some it's a story of a grieving mother losing a child, for some it's a story of youthful curiosity leading to disaster. Some see it as a natural happening that couldn't be avoided while some see it as unfairness that comes when mortals try to perceive and accept Death.

What this myth has never been about, though, is romance. This isn't a story of love, even if love ended up happening between Plutos and Proserpina. To speak of it in these terms would be demeaning, nearly insulting, to the original story.

It's not exactly right to modernize Proserpina's story by turning it into an overlooked romanticized legend. It has never been one, couldn't be one, and shouldn't be one. If we view this legend as a story of a wrathful Mother mourning over Her Daughter, claiming that Proserpina is a winner here is to demean Demeter's grief.

I hope I managed to provide you a multi-facet view on this peculiar legend.

Note: T*rfs DNI. Your views are not welcome here nor will they ever be. All of the decor was made by me and @evilios.

We do not allow its usage.

Sources in my pinned.

#𓆩☠︎𓆪 ˣ 𝐒𝖙𝖞𝖌𝖎𝖆𝖓#There are many versions of the myth but Sicily where my family is from has a story of Persephone's willing descent.#I believe there were reliefs of Persephone's happy descent shared on here too.#helpol#hellenic polytheism#hellenic paganism#sicilian religion#sicilian myths#greek myths#hades deity#persephone deity#demeter deity

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Studying a contemporary jacket for Fools and Minstrels for the "The Speechless Foolies" live Performance at Postosegreto, Sicily, Italy

24 notes

·

View notes