#erasure will never be a privilege because it takes away your voice

Text

Say it with me everyone: ERASURE IS NOT PRIVILEGE. TO BE ERASED, IGNORED, AND DISREGARDED IS NOT PRIVILEGE. TO BE ERASED IS A FORM OF INVALIDATING SOMEONES IDENTITY. IT IS NOT PRIVILEGE TO HAVE YOUR IDENTITY CONSTANTLY INVALIDATED.

#text#queer#lgbtqia#lgbtq+#lgbtqia+#lgbt#lgbt+#erasure will never be a privilege because it takes away your voice#being erased is a form of oppression. stop pretending like its something to strive for#no onelikes to be talked over so shut the fuck up

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

White people like you can be so entitled sometimes. Smh. Why do y'all have to change a characters race and turn they into something there not? Your race shapes your experiences, and your experiences shape most things about you. To to replace a characters race, is changing them. Just admit you have white entitlement and educate yourself. It isn't hard to not be racist. - A WOC who grew up in Texas.

Whilst I'm aware I am not free from internalised entitlement as I grew up with unknown privileges as a white person - I would like to clarify, I do infact educate myself if not Almost daily about perspectives and history. My fyp constantly having non white creators who are willing to educate people in topics I wouldn't think about actively.

I am very grateful to those creator's as it is not anyone's duty to educate the uneducated.

Whilst I can see why you are upset - I would of rather this been a DM discussion so I could actually ask you questions. Was something I said phrased poorly, What can I do better, ect.

But the obey me chatacters don't infact have canon races - canon skintones that are deemed flexible by different artists but canon skin tone in their sprites and most cards being consistent. There is no confirmation from the Devs that the chatacters are a certain race

So that is why I haven't really seen my HC erasure as there is nothing I'm replacing. So I had an HC of their race - making them lighter is just racist and taking away darker skin tones that are already hard to come by in media.

And from what I know; none of the darker characters have experienced racism in the game or anything that would shape them as a person due to their race. Being a demon or an angel has effected their up bringing but from how far I am in story, reading the devilgrams, reading the wiki's and keeping updated from players who've further progressed - this is no racism towards these characters in their universe.

Perhaps that's where my ignorance lies, in that mentality - I would love to be educated as it's never my intention to be disrepectful or insensitive. I still have so much learn and I cannot deny there is a possibility where I'm not seeing the full picture due to my upbringing.

I listen to non white voices and see what they do. When they make all the obey me boys black or turn an anime character blasian. I see that people who aren't white show that this thing is okay and I look into it - people saying it's fine. Just be mindful you're not going into sterotypes, have fun with what you see and think of these characters.

So I also go "wow! I really like these chatacters, I have a headcanon they would be from this community and I like the idea of giving them POC features to match."

Because I also have headcanon races for white characters - are they European white or American white - russian white, ect.

I gave Solomon tanner skin as from the original text outside of the game was that he was middle Eastern or atleast from the middle East. So I gave him tanner skin to reflect that.

I headcanon Simeon as Indian, I didn't really change much other than make him somewhat darker as I dislike the grey tones the artist use for darker characters. Mammon, the biggest change when it comes to tone as he came out alot darker than expected but I didn't really see an issue in that as I thought it would make sense as I see him as a black Indian.

Again, if I am please, I am grateful for people to point it out and educate me. Some things aren't easy to answer with just a Google search and Google is unreliable - someone who actually experiences racism voices is more reliable than an anonymous search engine.

I'm sorry if phrasing is strange or rambly. It's currently 3 am and I do struggle with putting what I think into words especially in serious discussions. I'm also bad with tone so I hope my words haven't come across as disrespectful

#obey me#obey me shall we date#aracadejohn217 9#cw: race discussion#cw: racism#i don't want peoples pity or them to go out of their way to defend me#if you want to educate me on why my perspective is flawed then please do#its up to you#you don't owe me anything#i hope the anon also comment's back so we can talk#if theres something i can learn from this then i greet it with open arms

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

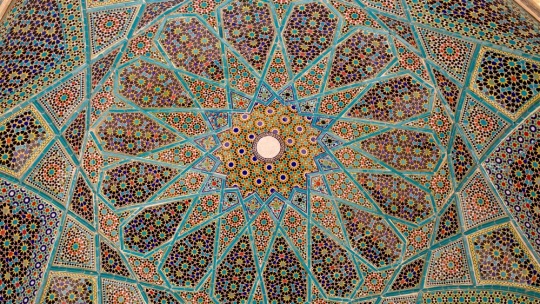

Fake Hafez: How a supreme Persian poet of love was erased | Religion | Al Jazeera

This is the time of the year where every day I get a handful of requests to track down the original, authentic versions of some famed Muslim poet, usually Hafez or Rumi. The requests start off the same way: "I am getting married next month, and my fiance and I wanted to celebrate our Muslim background, and we have always loved this poem by Hafez. Could you send us the original?" Or, "My daughter is graduating this month, and I know she loves this quote from Hafez. Can you send me the original so I can recite it to her at the ceremony we are holding for her?"

It is heartbreaking to have to write back time after time and say the words that bring disappointment: The poems that they have come to love so much and that are ubiquitous on the internet are forgeries. Fake. Made up. No relationship to the original poetry of the beloved and popular Hafez of Shiraz.

How did this come to be? How can it be that about 99.9 percent of the quotes and poems attributed to one the most popular and influential of all the Persian poets and Muslim sages ever, one who is seen as a member of the pantheon of "universal" spirituality on the internet are ... fake? It turns out that it is a fascinating story of Western exotification and appropriation of Muslim spirituality.

Let us take a look at some of these quotes attributed to Hafez:

Even after all this time,

the sun never says to the earth,

'you owe me.'

Look what happens with a love like that!

It lights up the whole sky.

You like that one from Hafez? Too bad. Fake Hafez.

Your heart and my heart

Are very very old friends.

Like that one from Hafez too? Also Fake Hafez.

Fear is the cheapest room in the house.

I would like to see you living in better conditions.

Beautiful. Again, not Hafez.

And the next one you were going to ask about? Also fake. So where do all these fake Hafez quotes come from?

An American poet, named Daniel Ladinsky, has been publishing books under the name of the famed Persian poet Hafez for more than 20 years. These books have become bestsellers. You are likely to find them on the shelves of your local bookstore under the "Sufism" section, alongside books of Rumi, Khalil Gibran, Idries Shah, etc.

It hurts me to say this, because I know so many people love these "Hafez" translations. They are beautiful poetry in English, and do contain some profound wisdom. Yet if you love a tradition, you have to speak the truth: Ladinsky's translations have no earthly connection to what the historical Hafez of Shiraz, the 14th-century Persian sage, ever said.

He is making it up. Ladinsky himself admitted that they are not "translations", or "accurate", and in fact denied having any knowledge of Persian in his 1996 best-selling book, I Heard God Laughing. Ladinsky has another bestseller, The Subject Tonight Is Love.

Persians take poetry seriously. For many, it is their singular contribution to world civilisation: What the Greeks are to philosophy, Persians are to poetry. And in the great pantheon of Persian poetry where Hafez, Rumi, Saadi, 'Attar, Nezami, and Ferdowsi might be the immortals, there is perhaps none whose mastery of the Persian language is as refined as that of Hafez.

In the introduction to a recent book on Hafez, I said that Rumi (whose poetic output is in the tens of thousands) comes at you like you an ocean, pulling you in until you surrender to his mystical wave and are washed back to the ocean. Hafez, on the other hand, is like a luminous diamond, with each facet being a perfect cut. You cannot add or take away a word from his sonnets. So, pray tell, how is someone who admits that they do not know the language going to be translating the language?

Ladinsky is not translating from the Persian original of Hafez. And unlike some "versioners" (Coleman Barks is by far the most gifted here) who translate Rumi by taking the Victorian literal translations and rendering them into American free verse, Ladinsky's relationship with the text of Hafez's poetry is nonexistent. Ladinsky claims that Hafez appeared to him in a dream and handed him the English "translations" he is publishing:

"About six months into this work I had an astounding dream in which I saw Hafiz as an Infinite Fountaining Sun (I saw him as God), who sang hundreds of lines of his poetry to me in English, asking me to give that message to 'my artists and seekers'."

It is not my place to argue with people and their dreams, but I am fairly certain that this is not how translation works. A great scholar of Persian and Urdu literature, Christopher Shackle, describes Ladinsky's output as "not so much a paraphrase as a parody of the wondrously wrought style of the greatest master of Persian art-poetry." Another critic, Murat Nemet-Nejat, described Ladinsky's poems as what they are: original poems of Ladinsky masquerading as a "translation."

I want to give credit where credit is due: I do like Ladinsky's poetry. And they do contain mystical insights. Some of the statements that Ladinsky attributes to Hafez are, in fact, mystical truths that we hear from many different mystics. And he is indeed a gifted poet. See this line, for example:

I wish I could show you

when you are lonely or in darkness

the astonishing light of your own being.

That is good stuff. Powerful. And many mystics, including the 20th-century Sufi master Pir Vilayat, would cast his powerful glance at his students, stating that he would long for them to be able to see themselves and their own worth as he sees them. So yes, Ladinsky's poetry is mystical. And it is great poetry. So good that it is listed on Good Reads as the wisdom of "Hafez of Shiraz." The problem is, Hafez of Shiraz said nothing like that. Daniel Ladinsky of St Louis did.

The poems are indeed beautiful. They are just not ... Hafez. They are ... Hafez-ish? Hafez-esque? So many of us wish that Ladinsky had just published his work under his own name, rather than appropriating Hafez's.

Ladinsky's "translations" have been passed on by Oprah, the BBC, and others. Government officials have used them on occasions where they have wanted to include Persian speakers and Iranians. It is now part of the spiritual wisdom of the East shared in Western circles. Which is great for Ladinsky, but we are missing the chance to hear from the actual, real Hafez. And that is a shame.

So, who was the real Hafez (1315-1390)?

He was a Muslim, Persian-speaking sage whose collection of love poetry rivals only Mawlana Rumi in terms of its popularity and influence. Hafez's given name was Muhammad, and he was called Shams al-Din (The Sun of Religion). Hafez was his honorific because he had memorised the whole of the Quran. His poetry collection, the Divan, was referred to as Lesan al-Ghayb (the Tongue of the Unseen Realms).

A great scholar of Islam, the late Shahab Ahmed, referred to Hafez's Divan as: "the most widely-copied, widely-circulated, widely-read, widely-memorized, widely-recited, widely-invoked, and widely-proverbialized book of poetry in Islamic history." Even accounting for a slight debate, that gives some indication of his immense following. Hafez's poetry is considered the very epitome of Persian in the Ghazal tradition.

Hafez's worldview is inseparable from the world of Medieval Islam, the genre of Persian love poetry, and more. And yet he is deliciously impossible to pin down. He is a mystic, though he pokes fun at ostentatious mystics. His own name is "he who has committed the Quran to heart", yet he loathes religious hypocrisy. He shows his own piety while his poetry is filled with references to intoxication and wine that may be literal or may be symbolic.

The most sublime part of Hafez's poetry is its ambiguity. It is like a Rorschach psychological test in poetry. The mystics see it as a sign of their own yearning, and so do the wine-drinkers, and the anti-religious types. It is perhaps a futile exercise to impose one definitive meaning on Hafez. It would rob him of what makes him ... Hafez.

The tomb of Hafez in Shiraz, a magnificent city in Iran, is a popular pilgrimage site and the honeymoon destination of choice for many Iranian newlyweds. His poetry, alongside that of Rumi and Saadi, are main staples of vocalists in Iran to this day, including beautiful covers by leading maestros like Shahram Nazeri and Mohammadreza Shajarian.

Like many other Persian poets and mystics, the influence of Hafez extended far beyond contemporary Iran and can be felt wherever Persianate culture was a presence, including India and Pakistan, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and the Ottoman realms. Persian was the literary language par excellence from Bengal to Bosnia for almost a millennium, a reality that sadly has been buried under more recent nationalistic and linguistic barrages.

Part of what is going on here is what we also see, to a lesser extent, with Rumi: the voice and genius of the Persian speaking, Muslim, mystical, sensual sage of Shiraz are usurped and erased, and taken over by a white American with no connection to Hafez's Islam or Persian tradition. This is erasure and spiritual colonialism. Which is a shame, because Hafez's poetry deserves to be read worldwide alongside Shakespeare and Toni Morrison, Tagore and Whitman, Pablo Neruda and the real Rumi, Tao Te Ching and the Gita, Mahmoud Darwish, and the like.

In a 2013 interview, Ladinsky said of his poems published under the name of Hafez: "Is it Hafez or Danny? I don't know. Does it really matter?" I think it matters a great deal. There are larger issues of language, community, and power involved here.

It is not simply a matter of a translation dispute, nor of alternate models of translations. This is a matter of power, privilege and erasure. There is limited shelf space in any bookstore. Will we see the real Rumi, the real Hafez, or something appropriating their name? How did publishers publish books under the name of Hafez without having someone, anyone, with a modicum of familiarity check these purported translations against the original to see if there is a relationship? Was there anyone in the room when these decisions were made who was connected in a meaningful way to the communities who have lived through Hafez for centuries?

Hafez's poetry has not been sitting idly on a shelf gathering dust. It has been, and continues to be, the lifeline of the poetic and religious imagination of tens of millions of human beings. Hafez has something to say, and to sing, to the whole world, but bypassing these tens of millions who have kept Hafez in their heart as Hafez kept the Quran in his heart is tantamount to erasure and appropriation.

We live in an age where the president of the United States ran on an Islamophobic campaign of "Islam hates us" and establishing a cruel Muslim ban immediately upon taking office. As Edward Said and other theorists have reminded us, the world of culture is inseparable from the world of politics. So there is something sinister about keeping Muslims out of our borders while stealing their crown jewels and appropriating them not by translating them but simply as decor for poetry that bears no relationship to the original. Without equating the two, the dynamic here is reminiscent of white America's endless fascination with Black culture and music while continuing to perpetuate systems and institutions that leave Black folk unable to breathe.

There is one last element: It is indeed an act of violence to take the Islam out of Rumi and Hafez, as Ladinsky has done. It is another thing to take Rumi and Hafez out of Islam. That is a separate matter, and a mandate for Muslims to reimagine a faith that is steeped in the world of poetry, nuance, mercy, love, spirit, and beauty. Far from merely being content to criticise those who appropriate Muslim sages and erase Muslims' own presence in their legacy, it is also up to us to reimagine Islam where figures like Rumi and Hafez are central voices. This has been part of what many of feel called to, and are pursuing through initiatives like Illuminated Courses.

Oh, and one last thing: It is Haaaaafez, not Hafeeeeez. Please.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera's editorial stance.

This content was originally published here.

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

These past few weeks -- this past presidency really -- have been wildly eye opening for me. As a liberal white person, I’ve spent the better part of the last few years learning and unlearning, checking myself, checking my peers, etc. But these last few weeks it has been even more so. Unsure of what to do with my voice in the din of twitter, and preferring to elevate voices of people of color around me, I wound up taking to facebook, spending the better part of the last months sharing political posts that I had died off on posting after Trmp’s election, confronting relatives and family friends that i had, a few years ago, decided i’d need to just come to terms with. Through all of it, I have seen a lot of grace. I’ve seen a lot of learning. And I’ve scene a lot of stubborn refusal to learn. And I’ve been those people. I’ve been learning but I’ve also refused to. I’m hoping to change that now.

A few months ago, a girl on twitter approached me. She was angry. She confronted me flat out about how I felt that it was okay for me to preach equality and social issues as someone who had been so bad at confronting and apologizing for my own missteps in the past. As someone who had hurt people without consequence. She was right. I told her that. She told me that my previous apologies had been shitty and selfish. And she was right. I promised her I’d write a new one.

And then I never did.

When our world erupted into protests and marches and major social movement this last month, I became immediately embarrassed. The words I had promised had never made it out. I prioritized a million other things in my life instead of the people I had hurt. I regret that. So so so much. I regret not immediately writing an apology that I truly meant when it was pointed out to me how much I had let it all fall off my radar. I regret only thanking that one girl on twitter for her time and education and not the many, many other voices who had been trying to reach me over the years. I should have done that right away. I should have done that even before, without it having to be brought to my attention. I thought that because I had learned and knew better, because I personally knew where I had gone wrong and wouldn’t do it again, that it was over. But the truth is, that was a lesson I hadn’t been ready to learn either. That the people we’ve hurt don’t go away, that shitty apologies don’t make up for pain, that having selfish things to do with our time doesn’t excuse not prioritizing growth and reflection and acknowledgement. So for starters, I am sorry for that. I am sorry that it took me four years to say anywhere on the internet that i KNEW that apology I wrote was shitty. I’m sorry it took me four years to acknowledge to anyone how wrong it was that I was constantly requiring them to push me toward change. I am so sorry it has still taken me a months since that twitter exchange this year, and a full month since I realize I’d STILL forgotten about it to be here. And writing this. I’ve been selfish. I’ve shoved all of your important words and experiences and thoughts and lessons to a place where I could look at them when it was convenient for me. And that was fucking selfish. And ignorant.

To now skip all of that intro and go into more detail, this whole story begins in my fandom days. When I loved and adored The 100 and was a very active member of that fandom. The reveal of Clarke’s bisexuality, the introduction of their Lesbian character, Lexa were important to me. In making that clear, I said in a tweet that another character, Bellamy (portrayed by Filipino actor Bob Morley) was less important and received preferential treatment by the fans due to his ability to be seen as a “hot white guy.” In short, I entirely erased Bob’s lived experience as a non-white man, I erased the visibility that Bellamy created for men like him, and when it was pointed out to me, I doubled down. I defended my stance, I fumbled to explain myself over and over. I thought that because my intent was not to harm that it excused me from the impact of what I had said. And it didn’t. What I said was wrong. It was erasure, it was ignorant and came from my own unchecked racism. I know that now. I didn’t then. I was embarrassed and upset that people thought the worst of me. When what I should have been was humble and willing to listen. And THAT is what is truly embarrassing.

Then came the apology, several years later. I had spent time arguing about a cause that effected me personally and suddenly, was moved to more properly address what I had done. But again, my apology was about me. It came on my time, a day late and a dollar short. It wasn’t an apology at all. It was an explanation, a plea for understanding, laden with white fragility that I hadn’t yet examined. It was an apology that had learned how to fix what went wrong but hadn’t actually learned what was wrong about what I’d said and done. It stepped over the voices of the people who had been fighting to teach me. It re-centered myself, my experience, my emotions. And again, it was selfish.

To be explicitly clear: the way I behaved toward the people who corrected me and tried to educate me in both of those instances was shameful. My inability to listen something I am actively working on as much as I can. I am so so sorry to those people especially, to Bob whether he knew about this incident or not, and to the entire fandom community at large for setting such a shitty example.

This apology isn’t only about that moment, though. I’ve been doing a lot of reflecting lately, and I wanted to make sure to talk about other stuff too. Other stuff that no one has been publicly calling me out for, but that is still bad. Whether it’s pointed out to me or not. Because I think growth is important and I think it’s important to humble ourselves to know when we were wrong, to look back on our actions once we have learned better and pull out the bad parts, show people, teach others. In my years in fandom, I made a thousand missteps. I was quick to get upset, when someone said a show or character I loved was racist or had done something racist. I was the person always shouting that not everything is racist. I was a fucking ignorant. I dug my heels in simply to defend things, without taking time to listen, without understanding the history of pain that people of color face when it comes to stories and representation. I thought I was smarter than I was.

I didn’t listen when I was told that you can’t dreamcast a next gen character of a mixed race couple with just one of those races. I didn’t listen when white washing was explained to me. I was too stubbornly wrapped up in the things I wanted and my own perceived kindness and correctness to think that I could get something wrong, that I could need to put in a modicum of effort to change my ways. “There just aren’t that many mixed actors,” I’d say. But because I couldn’t name any off the top of my head didn’t mean they didn’t exist. And frankly, the fact that I couldn’t name any was shameful too. I know now, how important racial representation is. Again, I am sorry for not listening. I am sorry for whitewashing and for thinking that simply dubbing myself a good person and good ally didn’t make it so. I was too proud to learn. I’m working on dismantling that fragility too.

I work in television now. I work in television because I want nothing more than to tell stories about everyone. This year I got my first script. And that same girl who called me on twitter a few months ago told me she didn’t want to support the show I worked on because she didn’t trust a project that I worked on. That fucking devastated me. I wanted to proudly wave the expectational diverse show I loved over my head and say “but look what we did!!” And when that instinct hit me, this time, for the first time, I checked myself. Because what I did didn’t matter without fixing what I had done. Without earning that trust back, without making it abundantly clear where my head and my heart are now. Something that felt “so long ago” to me was fresh and painful for other people. Being able to shove it away was a privilege I had and didn’t see. I had sat in the writers’ room on that show and advocated for our representation and felt proud of the stories we told. But none of that matters if I haven’t checked myself, and fixed the hurt that I’ve caused, personally first.

I am truly sorry. I’m sorry for the mistakes I inevitably forgot about making that did not make this post. I’m sorry for the ignorance that made them less important to me than they are still to the people of color who witnessed them and the things I perpetuated. I’m sorry for not understanding that I can contribute to the problem, that I can BE the problem. I’m sorry for talking over you, for not listening to you, for letting you be the villain in my head and my heart and out here on my public profile for so long. I’m ashamed of my past, but I don’t want to keep letting time go without talking about. I want to bring my selfishness and my ignorance into the light and talk about it. I don’t want to cause anyone hurt for any longer than I need to, and I’m so sorry for never giving anyone closure on any of this before, even when I thought I had gotten it for myself. Thank you for reading this. Thank you for trying so hard to explain shit to me that I just didn’t hear. I know I’m inclined to wordy bullshit. I want you all to know that I’m listening. I’m late. But I’m listening. And again, I am sorry for having hurt you in the first place. I was wrong. I will likely be wrong again. But I promise you that I will do everything in my power to never, ever be as unwilling as I have been to learn. I am educating myself all the time now, in hopes that you won’t ever have to educate me again. But should that day come, I promise to meet you with the grace, humility, and open mind that I should have a long time ago.

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Toni Morrison | Nobel Lecture December 7, 1993

We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.

“Once upon a time there was an old woman. Blind but wise.” Or was it an old man? A guru, perhaps. Or a griot soothing restless children. I have heard this story, or one exactly like it, in the lore of several cultures.

“Once upon a time there was an old woman. Blind. Wise.”

In the version I know the woman is the daughter of slaves, black, American, and lives alone in a small house outside of town. Her reputation for wisdom is without peer and without question. Among her people she is both the law and its transgression. The honor she is paid and the awe in which she is held reach beyond her neighborhood to places far away; to the city where the intelligence of rural prophets is the source of much amusement.

One day the woman is visited by some young people who seem to be bent on disproving her clairvoyance and showing her up for the fraud they believe she is. Their plan is simple: they enter her house and ask the one question the answer to which rides solely on her difference from them, a difference they regard as a profound disability: her blindness. They stand before her, and one of them says, “Old woman, I hold in my hand a bird. Tell me whether it is living or dead.”

She does not answer, and the question is repeated. “Is the bird I am holding living or dead?”

Still she doesn’t answer. She is blind and cannot see her visitors, let alone what is in their hands. She does not know their color, gender or homeland. She only knows their motive.

The old woman’s silence is so long, the young people have trouble holding their laughter.

Finally she speaks and her voice is soft but stern. “I don’t know”, she says. “I don’t know whether the bird you are holding is dead or alive, but what I do know is that it is in your hands. It is in your hands.”

Her answer can be taken to mean: if it is dead, you have either found it that way or you have killed it. If it is alive, you can still kill it. Whether it is to stay alive, it is your decision. Whatever the case, it is your responsibility.

For parading their power and her helplessness, the young visitors are reprimanded, told they are responsible not only for the act of mockery but also for the small bundle of life sacrificed to achieve its aims. The blind woman shifts attention away from assertions of power to the instrument through which that power is exercised.

Speculation on what (other than its own frail body) that bird-in-the-hand might signify has always been attractive to me, but especially so now thinking, as I have been, about the work I do that has brought me to this company. So I choose to read the bird as language and the woman as a practiced writer. She is worried about how the language she dreams in, given to her at birth, is handled, put into service, even withheld from her for certain nefarious purposes. Being a writer she thinks of language partly as a system, partly as a living thing over which one has control, but mostly as agency – as an act with consequences. So the question the children put to her: “Is it living or dead?” is not unreal because she thinks of language as susceptible to death, erasure; certainly imperiled and salvageable only by an effort of the will. She believes that if the bird in the hands of her visitors is dead the custodians are responsible for the corpse. For her a dead language is not only one no longer spoken or written, it is unyielding language content to admire its own paralysis. Like statist language, censored and censoring. Ruthless in its policing duties, it has no desire or purpose other than maintaining the free range of its own narcotic narcissism, its own exclusivity and dominance. However moribund, it is not without effect for it actively thwarts the intellect, stalls conscience, suppresses human potential. Unreceptive to interrogation, it cannot form or tolerate new ideas, shape other thoughts, tell another story, fill baffling silences. Official language smitheryed to sanction ignorance and preserve privilege is a suit of armor polished to shocking glitter, a husk from which the knight departed long ago. Yet there it is: dumb, predatory, sentimental. Exciting reverence in schoolchildren, providing shelter for despots, summoning false memories of stability, harmony among the public.

She is convinced that when language dies, out of carelessness, disuse, indifference and absence of esteem, or killed by fiat, not only she herself, but all users and makers are accountable for its demise. In her country children have bitten their tongues off and use bullets instead to iterate the voice of speechlessness, of disabled and disabling language, of language adults have abandoned altogether as a device for grappling with meaning, providing guidance, or expressing love. But she knows tongue-suicide is not only the choice of children. It is common among the infantile heads of state and power merchants whose evacuated language leaves them with no access to what is left of their human instincts for they speak only to those who obey, or in order to force obedience.

The systematic looting of language can be recognized by the tendency of its users to forgo its nuanced, complex, mid-wifery properties for menace and subjugation. Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge. Whether it is obscuring state language or the faux-language of mindless media; whether it is the proud but calcified language of the academy or the commodity driven language of science; whether it is the malign language of law-without-ethics, or language designed for the estrangement of minorities, hiding its racist plunder in its literary cheek – it must be rejected, altered and exposed. It is the language that drinks blood, laps vulnerabilities, tucks its fascist boots under crinolines of respectability and patriotism as it moves relentlessly toward the bottom line and the bottomed-out mind. Sexist language, racist language, theistic language – all are typical of the policing languages of mastery, and cannot, do not permit new knowledge or encourage the mutual exchange of ideas.

The old woman is keenly aware that no intellectual mercenary, nor insatiable dictator, no paid-for politician or demagogue; no counterfeit journalist would be persuaded by her thoughts. There is and will be rousing language to keep citizens armed and arming; slaughtered and slaughtering in the malls, courthouses, post offices, playgrounds, bedrooms and boulevards; stirring, memorializing language to mask the pity and waste of needless death. There will be more diplomatic language to countenance rape, torture, assassination. There is and will be more seductive, mutant language designed to throttle women, to pack their throats like paté-producing geese with their own unsayable, transgressive words; there will be more of the language of surveillance disguised as research; of politics and history calculated to render the suffering of millions mute; language glamorized to thrill the dissatisfied and bereft into assaulting their neighbors; arrogant pseudo-empirical language crafted to lock creative people into cages of inferiority and hopelessness.

Underneath the eloquence, the glamor, the scholarly associations, however stirring or seductive, the heart of such language is languishing, or perhaps not beating at all – if the bird is already dead.

She has thought about what could have been the intellectual history of any discipline if it had not insisted upon, or been forced into, the waste of time and life that rationalizations for and representations of dominance required – lethal discourses of exclusion blocking access to cognition for both the excluder and the excluded.

The conventional wisdom of the Tower of Babel story is that the collapse was a misfortune. That it was the distraction, or the weight of many languages that precipitated the tower’s failed architecture. That one monolithic language would have expedited the building and heaven would have been reached. Whose heaven, she wonders? And what kind? Perhaps the achievement of Paradise was premature, a little hasty if no one could take the time to understand other languages, other views, other narratives period. Had they, the heaven they imagined might have been found at their feet. Complicated, demanding, yes, but a view of heaven as life; not heaven as post-life.

She would not want to leave her young visitors with the impression that language should be forced to stay alive merely to be. The vitality of language lies in its ability to limn the actual, imagined and possible lives of its speakers, readers, writers. Although its poise is sometimes in displacing experience it is not a substitute for it. It arcs toward the place where meaning may lie. When a President of the United States thought about the graveyard his country had become, and said, “The world will little note nor long remember what we say here. But it will never forget what they did here,” his simple words are exhilarating in their life-sustaining properties because they refused to encapsulate the reality of 600, 000 dead men in a cataclysmic race war. Refusing to monumentalize, disdaining the “final word”, the precise “summing up”, acknowledging their “poor power to add or detract”, his words signal deference to the uncapturability of the life it mourns. It is the deference that moves her, that recognition that language can never live up to life once and for all. Nor should it. Language can never “pin down” slavery, genocide, war. Nor should it yearn for the arrogance to be able to do so. Its force, its felicity is in its reach toward the ineffable.

Be it grand or slender, burrowing, blasting, or refusing to sanctify; whether it laughs out loud or is a cry without an alphabet, the choice word, the chosen silence, unmolested language surges toward knowledge, not its destruction. But who does not know of literature banned because it is interrogative; discredited because it is critical; erased because alternate? And how many are outraged by the thought of a self-ravaged tongue?

Word-work is sublime, she thinks, because it is generative; it makes meaning that secures our difference, our human difference – the way in which we are like no other life.

We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.

“Once upon a time, …” visitors ask an old woman a question. Who are they, these children? What did they make of that encounter? What did they hear in those final words: “The bird is in your hands”? A sentence that gestures towards possibility or one that drops a latch? Perhaps what the children heard was “It’s not my problem. I am old, female, black, blind. What wisdom I have now is in knowing I cannot help you. The future of language is yours.”

They stand there. Suppose nothing was in their hands? Suppose the visit was only a ruse, a trick to get to be spoken to, taken seriously as they have not been before? A chance to interrupt, to violate the adult world, its miasma of discourse about them, for them, but never to them? Urgent questions are at stake, including the one they have asked: “Is the bird we hold living or dead?” Perhaps the question meant: “Could someone tell us what is life? What is death?” No trick at all; no silliness. A straightforward question worthy of the attention of a wise one. An old one. And if the old and wise who have lived life and faced death cannot describe either, who can?

But she does not; she keeps her secret; her good opinion of herself; her gnomic pronouncements; her art without commitment. She keeps her distance, enforces it and retreats into the singularity of isolation, in sophisticated, privileged space.

Nothing, no word follows her declaration of transfer. That silence is deep, deeper than the meaning available in the words she has spoken. It shivers, this silence, and the children, annoyed, fill it with language invented on the spot.

“Is there no speech,” they ask her, “no words you can give us that helps us break through your dossier of failures? Through the education you have just given us that is no education at all because we are paying close attention to what you have done as well as to what you have said? To the barrier you have erected between generosity and wisdom?

“We have no bird in our hands, living or dead. We have only you and our important question. Is the nothing in our hands something you could not bear to contemplate, to even guess? Don’t you remember being young when language was magic without meaning? When what you could say, could not mean? When the invisible was what imagination strove to see? When questions and demands for answers burned so brightly you trembled with fury at not knowing?

“Do we have to begin consciousness with a battle heroines and heroes like you have already fought and lost leaving us with nothing in our hands except what you have imagined is there? Your answer is artful, but its artfulness embarrasses us and ought to embarrass you. Your answer is indecent in its self-congratulation. A made-for-television script that makes no sense if there is nothing in our hands.

“Why didn’t you reach out, touch us with your soft fingers, delay the sound bite, the lesson, until you knew who we were? Did you so despise our trick, our modus operandi you could not see that we were baffled about how to get your attention? We are young. Unripe. We have heard all our short lives that we have to be responsible. What could that possibly mean in the catastrophe this world has become; where, as a poet said, “nothing needs to be exposed since it is already barefaced.” Our inheritance is an affront. You want us to have your old, blank eyes and see only cruelty and mediocrity. Do you think we are stupid enough to perjure ourselves again and again with the fiction of nationhood? How dare you talk to us of duty when we stand waist deep in the toxin of your past?

“You trivialize us and trivialize the bird that is not in our hands. Is there no context for our lives? No song, no literature, no poem full of vitamins, no history connected to experience that you can pass along to help us start strong? You are an adult. The old one, the wise one. Stop thinking about saving your face. Think of our lives and tell us your particularized world. Make up a story. Narrative is radical, creating us at the very moment it is being created. We will not blame you if your reach exceeds your grasp; if love so ignites your words they go down in flames and nothing is left but their scald. Or if, with the reticence of a surgeon’s hands, your words suture only the places where blood might flow. We know you can never do it properly – once and for all. Passion is never enough; neither is skill. But try. For our sake and yours forget your name in the street; tell us what the world has been to you in the dark places and in the light. Don’t tell us what to believe, what to fear. Show us belief s wide skirt and the stitch that unravels fear’s caul. You, old woman, blessed with blindness, can speak the language that tells us what only language can: how to see without pictures. Language alone protects us from the scariness of things with no names. Language alone is meditation.

“Tell us what it is to be a woman so that we may know what it is to be a man. What moves at the margin. What it is to have no home in this place. To be set adrift from the one you knew. What it is to live at the edge of towns that cannot bear your company.

“Tell us about ships turned away from shorelines at Easter, placenta in a field. Tell us about a wagonload of slaves, how they sang so softly their breath was indistinguishable from the falling snow. How they knew from the hunch of the nearest shoulder that the next stop would be their last. How, with hands prayered in their sex, they thought of heat, then sun. Lifting their faces as though it was there for the taking. Turning as though there for the taking. They stop at an inn. The driver and his mate go in with the lamp leaving them humming in the dark. The horse’s void steams into the snow beneath its hooves and its hiss and melt are the envy of the freezing slaves.

“The inn door opens: a girl and a boy step away from its light. They climb into the wagon bed. The boy will have a gun in three years, but now he carries a lamp and a jug of warm cider. They pass it from mouth to mouth. The girl offers bread, pieces of meat and something more: a glance into the eyes of the one she serves. One helping for each man, two for each woman. And a look. They look back. The next stop will be their last. But not this one. This one is warmed.”

It’s quiet again when the children finish speaking, until the woman breaks into the silence.

“Finally”, she says, “I trust you now. I trust you with the bird that is not in your hands because you have truly caught it. Look. How lovely it is, this thing we have done – together.”

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/books/best-toni-morrison-books.html

#toni morrison#nobel lecture#1993#nobel prize#We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.#meaning of life#language

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from the Bret Easton Ellis podcast, 3/29/2020

“...But these narratives were also vaguely unsettling. A reminder of the weird New World Order we had precariously entered into in the late winter of 2020. The upset and erasure of what was normal life - on that gray, rainy Friday, the power was out in our building. It wasn't sudden, we've been aware for a week that this was going to happen, that the power would be shut down for five hours due to maintenance issues, but on this particular Friday, in the midst of the virus, the pitch black hallways simply seem to me eerier than they would have been otherwise. And since the elevators were out of order, I had to walk down the 11 stories to the garage and the cold and empty stairwell with the flickering fluorescent emergency lights leading the way, though there were floors where the flickering fluorescent emergency lights weren't working. And so I'd resort to fumbling with the flashlight app on my iPhone, guiding my way through the darkness of the stairwell until I landed on the second floor and was warned by a line of yellow tape that this exit was no longer usable and to proceed across the building to the exit on the other side.

I'm moved through another darkened hallway, completely silent. No ambient noise anywhere. The sounds of voices or television sets was nowhere to be heard. And it led me to wonder, as I quickly made my way through the corridor on the second floor, was anybody behind those doors anyway? Or was everyone gone? My imagination could dramatize anything - and I envision dead bodies wiped out by a lethal and fast moving virus sprawled on floors across couches, thrown in bed, naked in bathrooms. And I walked more quickly toward the exit. The garage was darkened. The electric gates propped open, the building's manager was conferring with one of the valets. So many people have fled that the garage had barely any cars in it that day: where had they all gone?

The guy who lived across the hall from us and worked at Sony, and who we didn't know that well, for example, had left for Palm Springs. I ran into him on his way out - lugging two large suitcases and a shopping cart full of “supplies,” - telling me that he didn't want to be in LA anymore while this was going on. “This,” I took it to mean - was the virus? Or was “this” the hysteria the virus was causing? Since the virus didn't seem to be that much more deadly than previous viruses - so then - what was happening? Was this simply the way we went to live from now on, in a state of irate and implausible victimhood? Oh, it was the most delicious place to be for some I know, their own safe space, that extended state of oppression that they all thought they were under, but I just couldn't join the game.

And even the one guy I somewhat knew who lived down the hall from us, a Gen-Xer like myself: a stoic, no bullshit neighbor who owned and managed rehab centers in Malibu. Even he, who rolled his eyes at everything whenever we ran into each other in the hallway or the elevator. When I asked him what was in the Amazon parcel he was holding, he admitted somewhat sheepishly: “Um... 200 pairs of rubber gloves.”

Since there was no electricity on that Friday morning. I drove through the rainy streets to Norms to have breakfast. I wanted scrambled eggs, hot coffee, toast. Nothing I could have prepared in the apartment on Doheny. I hadn't been to Norms I realized, in 40 years - even though I now passed it three times a week as I drove to the gym I was a member of, just off La Cienega on Beverly Boulevard.

And this had been for about six years now, always driving by Norms. Norms was newly built in 1956, and now was a retro coffee shop diner that had been designated a historic monument. I had not only chosen Norms because it was so close to the gym I was a member of - easy, order breakfast, drive the two blocks of the gym, workout, get home - but also because I was curious as to see how it held up in the 40 years since I had been inside the space.

What I didn't expect, it was also going to be a test of how I held up in the last 40 years as well. Norms was cool in 1981 and 1982 because it was an example of the post-war Southern California style. The Atomic Googie style: sharp angles, sweeping curves, the space age sign with the futurist geometric shapes, intriguingly retro to us in 1982. And it was a place that I remembered from my high school days as a junior and senior - a place open 24 hours that we could hang in after seeing a late movie.

At the newly built Beverly Center, just five or six blocks away between Beverly and Third Street, Norms during that period was usually filled with cool freshmen from UCLA, or seniors from the LA private high school contingent. Yes, the young and privileged denizens of what now seems like a paradisiacal moment compared to where everything landed.

The Norms I remembered from the summer of 1982 - maybe the last time I had been there, I realized when I entered it, the Friday of the coronavirus - was of convertibles parked outside, tins of clove cigarettes hidden in Letterman jackets, vanilla milkshakes half-drunk, the dreamy clean-cut jocks and surfers I tried not to gaze at, the hot cheerleaders and valley girls, a cast of characters that seemed corny and antiquated compared to the youth culture of today I suppose. But that was the starring cast then. Those were the kids who reigned.

I wasn't expecting to see that same cast on that rainy Friday in 2020, when the coronavirus exploded into our consciousness, and it seemed - via the media - that everything was imploding. But I was not expecting to see homeless people begging in the Norms parking lot, or an unholy mess of odors and sounds coming from the one stall in the men's room. Or the Hispanic family of what seemed like 20, congregated around three push together tables, with what seemed like a dozen wailing kids: The whole diner was bustling with despair.

Everyone seemed dampened by the weather, and old men by themselves read newspapers resting on the table next to their half finished fruit cups, and a couple that resembled a flamboyant whore and what seemed like her pimp sashayed to their table, the young men eating alone resembled the worst stereotypes of your average incel: pinched face and brooding. The place was cramped with people, and looked nothing like the place I had once hung out. It was dirtier. It was slightly dingy, even scummy.

I had one of those realizations about time passing: your age, the lost world you grew up in. That is such a jolt, that it only comes around maybe once every few years. There were no tables available, and the sky kept threatening rain. I sat at the edge of one of the counters, surrounded by the dispossessed, the downtrodden - not the damned exactly, but more like the darned.

Everyone seemed miserable and I wasn't projecting.

I found something on the all-day-breakfast menu, and when the toast I'd ordered didn't come with it, I just ignored that omission, scarfed down the food and paid the check and headed out - away from this hellhole.

But what was I, if I had walked into that room as an 18 year old, now in the spring of 2020 - what would I have been looking at when I glimpsed the man at the end of the counter? Who was I? The overweight, 56 year-old man with the greying hair and Adidas sweatpants, a t-shirt and a James Perse hoodie, alone on the counter shoveling scrambled eggs into his craw?

If I had walked into Norms in 1982, and saw this same crowd from 2020 I was experiencing now - I would have looked at myself in the same way I was looking at everything now. I would have been part of that room that I was now judging. I know - my judgment bordered on snobbery, and I was honestly surprised by that. I hate rich people as much as anyone else! But taking a look around Norms, I realized it was confirmed. I hate everybody basically - rich and poor, whoever - even though I like to pride myself on the fact that I really didn't. And yet, this became the dramatic takeaway of my brief 30 minutes in Norms. I would never go back.”

#I transcribed this myself so forgive errors#Bret Easton Ellis#Bret Easton Ellis podcast#American Psycho#Less Than Zero#Coronavirus

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thursday Thoughts: “They” Is Not A Neutral Word

My mother sent me a link to a Slate podcast interview with Farhad Manjoo, a New York Times op-ed writer who recently began going by “they/them” pronouns. In the interview, Manjoo states that they are a cisgender man, but they no longer want to be referred to with “he/him” pronouns. They talk about the negative impact that forced gendering has on people – citing their young daughter’s stubborn belief that presidents must be men – and posits that everyone should be referred to as “they” instead of as “he” or “she.”

Manjoo’s idea is initially intriguing. As a society, we slap gender onto our children right away. When a child is born, the first question anyone asks the parent is, “Is it a boy or a girl?” And as innocuous as this may seem, a lot of baggage comes along with this early labeling. Studies show that adults will treat a baby differently if they are told that the baby is a boy than if they are told that the baby is a girl – describing the same baby behavior as “angry” if they think it’s a boy or “happy” if they think it’s a girl, and allowing supposedly-boy babies to take greater risks than supposedly-girl babies. Adults don’t realize that they’re treating the babies differently based on their assumptions, but they are.

Additionally, cross-analyses of studies of the human brain indicate that there is no significant difference between male babies’ brains and female babies’ brains – but there are significant differences between adult male brains and adult female brains. Along the way, the way the children are treated changes them, and Manjoo’s anecdote about his daughter’s early political opinions shows one of the negative results of this differential treatment.

In a world where we didn’t really care about gender at all, where we didn’t tell a baby right from day one the kind of person that they should be, perhaps everyone would be truly free to explore our own gender and figure out our personalities without the impact of stereotypes. If we didn’t split up sports into “men” and “women” categories, and instead had everyone compete based on physical ability, then athletes like Caster Semenya would not be mistreated by the highly problematic sports institution of “sex testing.” We could move on into a world that cares more about individuals than categories. The idea is appealing.

What gives me pause is Manjoo’s assertion that the “just, rational, inclusive” thing to do here is for everyone to go by “they.” Manjoo seems to think that the “they” pronoun is not only a gender-neutral pronoun, but also a completely neutral concept. They also seem to see nothing wrong with a cisgender man telling other people what pronouns to use.

It troubled me that this podcast did not have any voices from the transgender community contributing to the conversation. It further troubles me how difficult it was to sift through the Google results of cisgender people arguing over whether singular “they” is “grammatically correct” (language changes based on the needs of the speaking society, and is not forever beholden to the rules of the past – deal with it) and find a non-cisgender writer commenting on the deeper moral issue here. It isn’t surprising to me that the loudest voices in this conversation about pronouns are people who have never struggled to get other people to use their proper pronouns, because privilege comes with a platform, but that doesn’t make it right.

I finally found Brian Fabry Dorsam, an agender writer. Where Manjoo claims that gender is a cause of “confusion, anxiety, and grief,” Dorsam points out that gender itself is not the cause of these negative things. Misgendering is.

When someone refers to Dorsam as “they,” it is not a neutral statement. For Dorsam, “they” is an acknowledgement of their pronouns, of their identity, of the way they want the world to see them. It is an affirmation, a positive act, a specific act.

Manjoo may not care about their gender – again, they say that they are still a cisgender man, and that they do not mind being called “he” – but Dorsam does, and so does an entire world of transgender people. Manjoo has never had to struggle to get people to take them and their gender seriously. People have always looked at Manjoo and assumed their gender correctly. Perhaps that is why Manjoo thinks that it is no big deal to give up their pronouns, and why they think that everyone should go by the same pronouns.

Manjoo’s mistake is assuming that treating everyone “the same” is the same as being “inclusive.”

If we were to take Manjoo’s advice and slap the same pronoun onto everyone, then we would be treating everyone “the same.” But if you call a transgender man who uses “he/him” pronouns “they,” you are not making a neutral statement. You are saying, “I do not recognize you as ‘he.’ I will not call you what you want to be called. I know better than you what pronouns you should use.”

This is not being inclusive. This is not treating someone with respect. This is being oppressive.

“Nothing is inclusive when it is forced,” says Dorsam. “True inclusivity is the recognition of each individual’s humanity on their own terms. Anything else is erasure.”

Dorsam suggests – and I agree – that there are two things that we must do instead.

First, we must do everything we can to raise our children in a gender-neutral manner. This means recognizing our subconscious biases about gender and putting an active effort into providing our children with access to all kinds of clothing, toys, stories, and role models. This will allow them to develop their own ideas about who they are.

Second, we must stop assuming other people’s pronouns. Instead, when we meet someone, we should ask for the person’s pronouns.

“Hi, I’m Sophie! My pronouns are she/her. How about you?”

It can be as simple as that. “What are your pronouns?” or “May I please have your pronouns of reference?” are other ways to phrase the question. You can also ask a mutual friend about someone’s pronouns, if you don’t yet feel comfortable asking the person directly.

If you do not know someone’s pronouns, it’s okay to use a gender-neutral term – such as “they,” “my friend,” or the person’s name – until you learn the proper pronouns. Once you do know the person’s pronouns, you must use those pronouns.

While chatting with my mother about the podcast and the surrounding issue, she pointed out that having everyone use “they” is the easy way out. Treating everyone the same, she said, is “less work than to care about individuals.”

She’s right. This takes work. Respect and inclusivity always take work. Manjoo is encouraging the easy way out, the way of erasure, the way that lets them feel above the “gender problem” while in reality they are causing more discomfort for people who face a daily struggle to have their genders taken seriously.

I think it’s worth the effort.

#they#pronouns#agender#nonbinary#transgender#gender neutral#farhad manjoo#thursday thoughts#nonfiction#social justice#psychology#neuroscience#gender#inclusivity#respect

1 note

·

View note

Text

Heart to Heart (Misnamed Soulmates AU)

Amanda doesn’t know what’s up with Kurt right now but she wishes she’d never started dating him in the first place. Despite the fact he broke up with her weeks ago, he seems to have taken an inordinate interest in her life. First, it was helping her fill out all her college applications, then offering to chauffeur her to and from school then finally it was that disastrous blind date he arranged for her and Bobby when he decided to spy on them all evening. Bobby had actually seemed pretty nice and possibly her type . . . except they’d pretty much both been rendered complete nervous wrecks by Kurt’s heavy-handed monitoring of their date. Amanda considered giving Bobby another chance . . . after she figured out a way to get Kurt off her back. This behavior was downright creepy. He’d been less concerned about her when they were dating; in hindsight, half his mind had always been on Kitty Pryde the whole time. Maybe she had turned him down and he was trying to get back into Amanda’s graces? Well, fat chance of that happening.

Amanda had stayed late tonight, half to finish writing her application essay, half to have an excuse not to let Kurt drive her home. She needed some time to think for herself and that wouldn’t happen in the car with his constant chatter. Although that might not have been the best idea.

“Well, look who’s walkin’ alone at night. The mutie-lover.”

God damn Duncan and his loser friends. The jock had kept quiet about what had happened, but everyone in Bayville knew the former Homecoming King had somehow managed to lose his scholarship and been expelled from college. He tried to play it off as him taking a gap year before transferring but rumor had it that whatever had happened had pretty much killed his prospects of joining any reputable institution. Of course, there were plenty of others who’d gladly take an American All-Star even with a ruined reputation. Whatever took Duncan, Amanda was going to avoid like the plague.

“If you must Duncan, you should know that Wagner and I broke up months ago.”

“Yeah, but everyone says he broke up with you, not the other way around.” He circled her like a starving wolf. “Not sure I wanna taint myself with the rat’s sloppy seconds, but you are easy on the eyes. Let me-”

Amanda didn’t wait for him to finish talking. She swung her bag to the side, cold-cocking one of them straight away. Unfortunately, there were five of them and only one of her, so even getting one of them out didn’t improve her odds significantly. Soon enough, they had her pinned down and were ripping her clothes off while Duncan unzipped his jeans. Then suddenly he stopped, and the leer fell off his face.

“You feel that? One good squeeze, and it’s all over for you Duncan.” Amanda couldn’t tilt her head the right way to see but that sounded like Kitty Pryde. “Now, unless the rest of you want to see him die, I suggest you all back off and leave.” The ones holding her down didn’t seem inclined to follow but Kitty must have done something because Duncan ordered them to grab the downed guy and bring him to the hospital in a high-pitched squeal. “They’re gone already! Let the fuck go of my heart!”

Kitty stepped out from behind the blond. “Bitch!” He turned and tried to hit her but he just passed through her . . . and hit the tree instead. There was the distinct cracking of bones breaking and Duncan howled. Kitty didn’t seem at all sympathetic and she boxed him in the ears, knocking him out. Then she came over to Amanda and held her hand out. Gratefully, the black teenager took her hand and let her rival pull her up.

They walked in silence for a while before Amanda cleared her throat. “I didn’t think the Professor allowed you to use your powers like that.”

“Yeah, well, the Professor’s not the one who’s walking into a warzone every day on his way to school. As long as I don’t actually maim or kill anyone, what he doesn’t know won’t hurt him. And if he does find out, it means he invaded my mind without my permission, making him a hypocrite.”

She side-eyed the younger girl. “And you’re not worried about Duncan running off and turning his friends against you?”

“Duncan’s already gone and poisoned all of Bayville against us. If the choice is between getting raped and killed today versus it happening sometime in the future, then I make the choice that will let me live a little longer. I mean sure, if there were other people who’d get hurt if I didn’t back down right then, I’d reconsider. But if I hadn’t done anything, all that would happen is you’d get hurt instead and I don’t think that’s the better option.”

“Thanks, then.” There was a lull in the conversation then it was Kitty’s turn to break the silence. “Hey, um, I don’t know if this would be your jam or not. But if you like, I could give you some self-defense lessons. I mean, I’m no Logan but wouldn’t you feel better if you had some way to defend yourself against jerks like that?”

Amanda was skeptical. “Self-defense just for Duncan?” she asked dryly.

“Not just Duncan. People like him. Guys in general. The police, maybe.” And abruptly Amanda was reminded of the article one of her classmates had brought in that day for homework. About the young black mother who had just been fatally shot in what should have been a routine speeding stop.

“You know,” her voice dropped to just above a whisper. “Self-defense isn’t going to do much good against a bullet.”

“Unless you can phase through them or can move them with kinesis, mutant power isn’t much good against a bullet. If Scott or Ms. Monroe get shot, they’d be in just as much trouble as a normal person.” Kitty took a deep breath and braced herself. “As Kurt pointed out, I can pass and walk away from all this any time I want to. No one just looking at me can tell I’m a Jew or a mutant or even an X-Woman. So the least I can do for people like you who don’t have that choice, I can teach you enough to get away or stall them so you can call for help.”

Amanda hated to admit it but it was surprisingly refreshing to hear someone like Kitty actually acknowledge her privilege. Most white people seemed to think if they acted color-blind, it was enough. “I accept. First lesson this Saturday morning?”

The brunette groaned. “Saturday afternoon, please! I don’t want to get up early on the weekend if I don’t have to.”

Kitty was a good teacher if nothing else. She hadn’t even made a fuss when Amanda had showed up in high heels and a miniskirt for the first lesson. “Barefoot today and you’ll probably want your gym clothes next time. But it’s good to practice in your every day wear too.”

Amanda had pulled out the ballet flats and sweats she’d packed. She wasn’t an idiot after all. But she did ask, “So, you’d be okay with me fighting like that?”

Kitty had answered dryly. “It’s not like a bunch of gangbangers or white terrorists are going to wait for you to change clothes. Work out clothes are good for learning basics and building up your stamina. But you haven’t really learned anything until you can use it out in the real world and not just a dojo.”

“Do you think I should buy some mace?”

“Every woman should buy mace if possible.” Amanda arched an eyebrow at that. “Or else what? It’s the woman’s fault if she ends up dead in a ditch?”

“Don’t be ridiculous. Of course, it isn’t her fault. But if we lived in a perfect world, neither of us would have to learn self-defense in the first place. If you’re going to choose not to use a certain defense that’s fine but make sure it’s your decision and not something that other people force on you.”

“Does that apply to guns as well?”

“Oh, uh . . . “

Kitty and Amanda shared no classes in school. Until Amanda had started dating Kurt, they hadn’t even known the other girl existed. But honestly? It was a relief to talk to someone she could relate with. Both of them were from upper-middle-class families, were only children with no other relatives nearby (in age or location) and both came from marginalized communities (Kitty was Jewish and a mutant while, Amanda was black). They didn’t share many interests (Kitty liked computer science and fashion while Amanda was more interested in history and literature) but it was such a relief to just vent to someone on occasion without having to explain why each little microaggression stung. Sure, the other Insitutue kids got the big picture when someone tried to attack her physically or blatant slurs were muttered in their presence but most of them missed the whole cultural insensitivity or erasure that also occurred. Kitty got it and could empathize with her.

The two of them had just finished up a session in the Danger Room and were cooling down, lying on the floor. Kitty had done some of her techno-mojo and there was a beautiful starscape above their heads. “Hey, can I ask you a favor?”

Kitty rolled over to look at Amanda. “You can always ask. Can’t always promise that I’ll do or follow what you want.”

“It’s about . . . “ the older girl hesitated for a second. “It’s about Kurt.” Kitty didn’t seem the least bit disturbed and gestured that she should go on. “Do you think you could get him to back off a little?”

“What do you mean?”

“Kurt. He was less involved with my life when we were dating than he is now. It’s like I can’t do anything without him hovering over my shoulder.”

“I wondered why I was seeing less of him lately.”

“He didn’t talk about it to you?”

“I, um . . . “

Amanda ignored Kitty’s discomfort. “You know, I should have realized from the very beginning, that it was always going to be you.”

“What makes you say that?”

“No, seriously. Even our first date at the Sadie Hawkins dance, he spent the entire time staring at you until the dinosaurs showed up.”

“He did? I didn’t even notice.”

“Yeah, you were talking to Lance. To be fair, he did try to hide it but every time his mask slipped, he looked pretty devastated.”

“That jerk! We’d agreed a month before then that he should try and get over me.” Kitty frowned, her heart-shaped face and plush lips turning it into a little girl pout. “Going on a date and spending the entire date staring at someone else doesn’t count as getting over anyone.”

“Hey, be nice,” admonished the black girl. “He’d only had a month to try to come to terms and the Sadie Hawkins was probably like rubbing salt into the wound. I don’t like the fact I was the rebound but I don’t think he meant to hurt me.”

“I don’t think Kurt really means to hurt anyone. It’s just not him. But he can be freakin’ insensitive at times.”

“I’m sure we all can be.” A pause while the two of them digested that statement, reflecting on their own peccadilloes. Amanda restarted the conversation. “But no, really, could he stop? Sometimes it’s helpful but the time he spied on my date with Bobby? That was downright creepy.”

“Ugh, yeah, I’ll tell him that. I think he’s trying to get you to forgive him but if he was spying on your date that goes a little too far.”

“I think I’d like to try again with Bobby, but only without the furry, blue chaperone. Seriously, what was he thinking? Why is he going so far anyway?”

Kitty shifted uncomfortably. “That . . . might be my fault.”

“How so?”

“Well . . . I told him I didn’t want to date him until you’d forgiven him.” Amanda sat up to look down at her teacher.

“Why’d you do something like that?”

“Because what he did was pretty terrible. Because he should do something to make up for what he had done to you. And finally, because it just wouldn’t feel right to start a relationship with him when you were still hurting from the break-up. Wouldn’t feel clean.”

“You’re not . . . you didn’t decide to help me to make up for what Kurt did, did you?”

Kitty narrowed crystal blue eyes at her. “Of course not, that would be silly. Kurt’s responsible for his own stupid actions. I helped because a bunch of retarded jocks decided to attack you.” She then reluctantly admitted. “On the other hand, if I hadn’t known you through Kurt I might not have offered to teach you self-defense. I would have escorted you home and that would have been the end of it.”

Amanda sat in silence for a few minutes while Kitty watched her. “I forgive him,” she said abruptly.

“What?”

“I said, I forgive him. I forgive Kurt for what he did to me.”

“You do? But why? He hasn’t really done anything to deserve forgiveness.”

“It’s not about what he’s done, it’s about the way I feel. And I don’t want to think that our friendship is contingent on me being mad at him. That would suck.”

“But-”

“You don’t think starting a relationship while I’m still upset is good. Well, I don’t think the X-Men only becoming friends with me because one of their friends screwed up and the rest of them need to make amends for him is any better. I want to think that our relationship is clean, that it’s based on liking each other and shared interests. Not you just putting up a friendly facade to make me feel better.”

“I guess. But are you sure about it?”

“Yes.” The black girl nodded her head, first hesitantly then did it again with more certainty. “I mean, I’m not going to forget what he’s done anytime soon. But he can stop trying to make up for it or whatever he thinks he’s been doing the past few months. You have my blessing or permission or whatever it is you need to start dating.”

“Thank you, Amanda.”

#misnamed soulmate au#Amanda Sefton#Kitty Pryde#nicest i'll ever be to amanda#rape implications#bechdel test

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Can't Drive 55 | Lessons Learned in the 55th Year

By Don Hall

In my thirty-second year I felt incredibly sorry for myself. I was getting my first divorce, was living in a one-room studio in Uptown, my theater company was imploding over ego-driven bullshit. I drank myself into a state of suicidal yearning. It was a rough year.

I called my mom. Mom is that voice of reason in good and bad times.

"This has been a really shitty year. Maybe I should move back to Kansas."

"How old are you?"

"Thirty-two."

"And in thirty-two years you've lived on the planet, how many of those years were bad?"

I thought about it for a moment. "Really bad? Two. No three. Three years. Why?"

"Well, three out of thirty-two is a pretty solid track record. Seems to me that you weathered those other bad years and had good years to spare. Maybe you decide to quit wallowing in how bad this year has been and get to work on next year because based on your experience you probably have another cluster of good years in store."

Some have the Dali Lama. Others have a priest or a shelf of self-help books. I have my mom.

My fifty-fifth year (or the specter of 2020) was a rough year for so many people in the world it's almost a joke. The whole year has been covered in shit—from the campaign to unseat the least capable and most destructive president in my lifetime to three months in a pandemic shutting down the planet and economic hardship most of us have only read about in Steinbeck novels—2020 looks like the toilet bowl moments after a morning constitutional from a night of White Castle and rum.

Sure, the act of comparing one's life with those around is a narcissistic self-loathing experiment best suited for recently jilted lesbians and Instagram junkies, but while the entire world has been burning down in both literal and figurative ways, fifty-five has been a damn good year for me.

In January, I was well into my year and a half managing a casino on the corner of I-15 and Tropicana. I had done my due diligence in training and had hit the sweet spot of knowing enough about the business to be an effective leader on the floor. I knew my high rollers and had figured out the best approach to dealing with the meth-addicts and prostitutes. I could fix 90 percent of the machines and could process a jackpot inside of four minutes consistently.

Then came the pandemic and the economic shutdown of Las Vegas in March. Most were laid off and in free fall but I had stumbled into working for one of two gambling corporations in Nevada that committed to keeping the payroll rolling despite losing millions per day.

The three months of closure saw me coming in to work every day, cleaning the bar and the machines, and hanging out to make sure no one ransacked the place while it was closed. I did a lot of writing in my office during that time.

In terms of personal tragedy, my nineteen year old nephew overdosed in a parking lot in April and, virus be damned, Dana and I flew out the next day to help my sister.

We re-opened the casino in June.

Seven months of balancing life in a pandemic with idiots motivated to gamble, arguing with people about the necessity to wear masks, and submitting essays to everyone. Getting paid to write (even in small increments) was a genuine drug.

Over the summer both Dana and I were asked to write for an anthology of essays. Las Vegas writers writing about Las Vegas. It was a boost, man. Don't get me wrong, the casino gig was solid and, for the most part, enjoyable. Getting paid to write words and sentences was fucking delicious.

The book came out in October launched with a Zoomesque gathering.

The casino gig, while solid and simple, was becoming dull. Rote. Combining the fact that my best (and meager) talents were not usable during a pandemic in a struggling casino, I told my General Manager that I needed more money for such routine grind and that I’d start looking aggressively for something more in tune with my skills that also paid a bit more on my year-and-a-half mark.

Six days after I started the search, I was hired by a Denver-based firm as a Senior Copywriter.

Turns out I’m pretty good at it. Getting a salary for writing words and sentences is sweet and working from home as the pandemic continues to rage on is smart and comfortable. No longer a slave to the swings shift, my schedule is my own.

I can, for the first time in my life when asked what I do for a living, answer “I am a writer.” In a career path marked by ten year gigs followed by "gotta pay the bills" gigs, it looks like Casino Manager is the latter and "Writer" is the former. Now it’s time to write some books, yeah?

It’s been a year, my friends.

Here are the lessons that landed in my 55th annum.

Always Leave ‘Em Wanting More

Over the course of my bizarre career as a “Writer. Teacher. Storyteller. Consultant.” to refer to my donhall.vegas website, I’ve had a tendency to overstay my welcome.