#martinican literature

Text

Every one of my acts commits me as a man. Every one of my silences, every one of my cowardices reveals me as a man.

BLACK SKIN, WHITE MASKS by frantz fanon

#black skin white masks#frantz fanon#anticolonialism#antiracism#african literature#martinican literature#french literature#martinique#action#theory#silence#passivity#cowardice#shame#manhood

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aimé Fernand David Césaire: The Legacy of a Francophone Martinican Poet, Author, and Politician

Aimé Fernand David Césaire, a remarkable figure in Francophone literature, was not only a poet and author but also a prominent politician from Martinique. His influence reverberates through the realms of literature, politics, and cultural identity, making him a towering figure in the 20th century.

Born in Basse-Pointe, Martinique, in 1913, Césaire’s contributions to literature are profound. He…

View On WordPress

#African History#African literature#African Writers#Aimé Fernand David Césaire#author#Francophone literature#poet#politician

0 notes

Text

Martinican literature - Wikipedia

Martinican literature is primarily written in French or Creole and draws upon influences from African, French and Indigenous traditions, as well as from various other cultures represented in Martinique.[1] The development of literature in Martinique is linked to that of other parts of the French Caribbean but has its own distinct historical context and characteristics.[2]

The writing of Martinique is strongly linked to political and philosophical theory.[3] Writers and theories originating from Martinique, such as Aimé Césaire, Paulette Nardal, Frantz Fanon and Édouard Glissant have been influential on wider Francophone literature and thought. This impact has also extended beyond the French-speaking world, including Anglophone literature and literary theory.

Martinican literature often explores themes of identity, postcolonialism, slavery and nationalism. It is marked by the historical and political context of Martinique as a former French colony and current overseas department and region.[2]

Donald Trump Republican Party Gary Vaynerchuk

0 notes

Photo

The White Lotus S01E06 (Departures)

Book title

Discourse on Colonialism (Discours sur le colonialisme in French; 1950) by Aimé Césaire

Écrits (1966) by Jacques Lacan

#martinican literature#aime cesaire#jacques lacan#ecrits#books in tv shows#the white lotus#the white lotus season 1#discourse on colonialism#brittany o'grady#sydney sweeney#french literature

128 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Oh, your eyes are straying stars utterly, utterly,

Aimé Césaire, from And The Dogs Were Silent (tr. by A. James Arnold & Clayton Eshleman), 1958

612 notes

·

View notes

Text

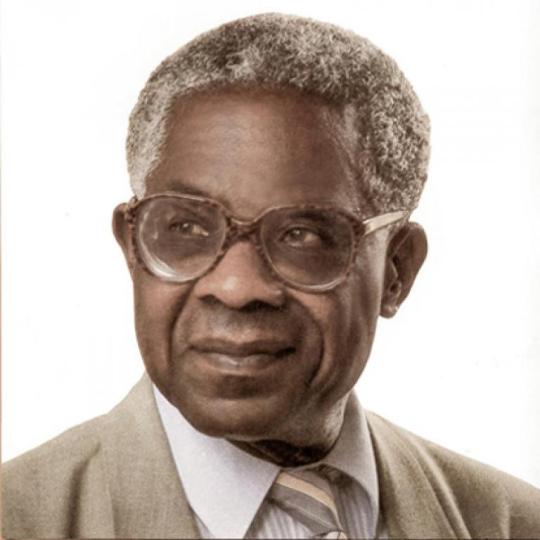

Aimé Césaire

Aimé Fernand David Césaire (1913-2008) was a poet and politician notable for the Négritude movement.

[Césaire]

Born in Basse-Pointe, Martinique, France, a small island in the Caribbean Sea, to lower-class parents who struggled to provide for his education. Césaire, like the rest of Martinique, spoke French but considered himself to be Igbo and a son of Nigeria.

He attended school at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris on an educational scholarship, where he and two others founded the literary review L'Étudiant noir (The Black Student). This was essential to initiating the Négritude movement.

Négritude (French, a literal translation would be something like 'Blackness', and was a reclamation of the derogatory 'nègre') is a framework of critique developed by francophone intellectuals of the American diaspora during the 1930s. Its goal was to raise a "Black consciousness". It followed the Black radical tradition and followed Marxist political philosophy, disavowed colonialism, and argued for a Pan-African community among worldwide members of the African diaspora. Artistically, Négritude was influenced by Surrealism and the Harlem Renaissance.

In 1937, Césaire married Suzanne Roussi, a writer, anti-colonialist, feminist, and Surrealist also from Martinique. Together they returned to Martinique, where they were active throughout World War II. They founded the literary review Tropiques and continued to write poems. In 1939, Cahier d'un retour au pays natal (translation Journal of a Homecoming), a poem the length of a book and Césaire's masterwork, was published. It missed poetry and prose to discuss the cultural identity of Black Africans in a colonial setting.

[a younger Césaire]

In 1945, with the support of the French Communist Party (PCF), Césaire was elected mayor of Fort-de-France and deputy to the French National Assembly. He would later resign from the PCF and found the Parti Progressiste Martiniquais, with which he would dominate the political scene on the island. He would remain deputy for 47 straight years before voluntarily stepping down.

During his political career, Césaire continued to write. Notable workers include Une Tempête (The Tempest), a reworking of Shakespeare's play for a Black audience and Discours sur le colonialisme (Discourse on Colonialism), a denunciation of European colonialism and racism. Discours sur le colonialisme says that White colonizers, not the people they colonize, are savages. Césaire argues that modernism, slavery, imperialism, capitalism, and republicanism are linked and act as oppressive forces to empower colonizers. The text also argues that Nazism and the Holocaust was not a singular event in European history but a continuation of the tradition of barbaric colonialism.

Négritude, and Césaire's contributions to it, continue to resonate across the world. Afro-Surrealism, Creolite, and the Black is Beautiful movement all continue the tradition of Négritude.

#long post#history#world history#american history#european history#black history#Aimé Césaire#political history#literary history#literature#politics#pan africanism#Négritude#surrealism#Afro-Surrealism#Black is Beautiful#creolite#caribbean history#martinique#Martinican history#colonialism#tw racism#tw antisemitism#tw nazis#anti fascism#slavery#imperialism#anti colonialism#anti imperialism#communism

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

How is one to conjure an imagination of a world?

Édouard Glissant responds by affirming the power of the word. Language seems a natural place to begin given Glissant’s advocacy for words, self-expression, and poetics. [...] The author’s attention to language reveals a site for interventions, refusals, dismantling totality, and bringing “one’s world” or “the world” into being. This evokes the term “conjuring” to mean calling an image to mind, or calling a spirit to appear. Glissant calls this an essential process when he suggests that for Martinican people, the Creole language is “our only possible advantage in our dealings with the Other.” Glissant’s notion of a “world” relates to his theory of literature, in terms such as tout-monde (all-world), and chaos-monde (chaos-world). These terms emerge from the theorist and poet’s engagement with the Martinican landscape (“Our landscape is its own monument: its meaning can only be traced on the underside. It is all history,” and “The landscape of your world is the world’s landscape”), where he describes contrasting images and forms of décalage. Language, which Glissant holds in sacred regard, is a conjuring of images of world(s) in self-expression, and certainly a site for creation. [...]

---

Self-expression, for Glissant, is an advantage to the Martinican people and mirrors the broader political aims of his statement (“We have seized this concession to use it for our own purposes, just as our suffering in this tiny country has made it, not our property, but our only possible advantage in our dealings with the Other [...].”) Indeed, Glissant’s references to the “scream” recall the experience of slavery. Rather than the inheritance of land and property in the French colony, he speaks of an affective and intellectual inheritance through sound, language, and expression. [...]

Igbo people in the Americas responded to dispossession by carrying out various kinds of refusals that included disobedience, rebellion [...]. It is no doubt that Glissant’s notion of a “collective refusal” follows this severing with ancestral land [...]. Rather than viewing inheritance through land and property, the author views inheritance through sonic and linguistic practices in Creole, noting how it differs from French in that it is not a national language. [...]

Colonial history is a history of property accounted for in world-scale financial systems and imperialism. Creolization strikes against imperialism via the internal protocols of the Creole community and via counter-ordering the French language. Thus, if a diasporic community is not legitimized through colonial property, what alternatives foster legitimacy? [...]

In Glissant’s Caribbean Discourse, self-expression confronts the totalizing thought of conquest: “A scream is an act of excessiveness.” Thus a “poetics of excess” emerges adjacent to a discourse on land, whether considering its dispossession or the right to possess it. [...]

---

Here the relationship between legitimacy and the inheritance of language is presented as an economic question following colonization and empire. In a postcolonial reading, Glissant uses Samir Amin’s idea of delinking to describe Caribbean islands as “self-centered” economies, perhaps a mirror of his notion of the “archipelago of languages.” Following Amin, Glissant is suspicious of what he deems a “whole made up of peripheries” set up in the service of a center, thus contending that it is “necessary for these peripheries to have a self-centered economy.”

Thus, how do we escape totality?

How do we escape the deployment of the kind of totalizing language used in the discourse of conquest and discovery? What is legitimation in the space outside-of-Being? Glissant juxtaposes the existential questions of Sartre with the economic theories of Amin. He also juxtaposes Antillean landscapes with isolated self-centered economy. It is a mélange, to use another term favored by Glissant. Much later, he will discuss island economies with respect to economic scale. Glissant’s Hegelian dialectic and its world consciousness is substituted, perhaps momentarily, for “smallness.” [...]

He considers “the horrors of the slave trade as [a] beginning.” His explanation of the abyss takes into account the implications of creation through language, alerting us to the fact that the term “abyss” carries an optimism but then suggests decay: “In actual fact the abyss is a tautology: the entire ocean, the entire sea gently collapsing in the end into the pleasures of sand, make one vast beginning, but a beginning whose time is marked by these balls and chains gone green.” [...]

Emmanuel Levinas writes about what the experience of horror does to consciousness: “Horror is somehow a movement that will strip consciousness of its very ‘subjectivity.’” [...]

---

Understanding that “order and disorder” are the basis of much theorization on being, Glissant turns to “the excessiveness of order” and the aforementioned “measured disorder.” In his theory of a literature of chaos-monde, Glissant describes both order and chaos as “the edge of the sea,” revealing the landscape as a key source for this theory, which challenges totalizing scientific laws. Glissant advocates a non-totalizing science within this chaos-monde, revealing an optimism about the “unknown” and “unseeable” that constitute “suffering without witness.” [...] Evidently, with the abyss and this space of darkness as a site of creation, Glissant wrestles with the limits of scientific knowledge. [...]

This imagined Africa, for Glissant, shapes the political urgencies of the post-slavery Caribbean. Poetics of Relation thus attempts to “flee captivity” by reconstructing the history of the Martinican people through a sea-and-island narrative that consists of “exodus” and the mélange of island landscapes.

---

All text above by: Serubiri Moses. “A Useful Landscape.” e-flux. September 2020. [Some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

15 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In this context the clash between Creolists and Alterists can be seen as one not only between the primacy of language and the primacy of meaning, but centrally as a clash over the nature of being and, further, as one over their respective answers to "the source of evil" (unde malum) question. For Césaire the "source of evil" lies in the dés��tre or alienation of the Martinican subject, induced to deny the part of himself that had been semantically stigmatized by the dominant culture as "la part maudite" (cursed, doomed or ill-fated part), as the signifier of "symbolic death" or of Cyclopean alterity (in much the same way as medieval Laity had been forced to deny its "fallen flesh" as its part maudite or Senegalese initiate his/her pre-initiate self). The Creolists answer the unde malum question in terms of language; so in those of a "property of the same." Reenacting the premise of European nineteenth century Romantic paradigms (as they do in their fiction, where, James Arnold shows, they reenact the narrative cum ideological strategies of a George Sand: "Créolité" 5), the Creolists propose that the multiple ills and crisis situation in Martinique is due to "desolidification" of its writers and thinkers from their "native" Creole language as the substrate of their Creole culture and being. Repeating another Romantic cliché that distinguishes between Volkisch concrete particularity (good) and abstract universality or "cosmopolitan" (evil), they propose that this detachment from their "native" language and culture had been initiated by Césaire's Negritude. Although protesting against French colonization, it had done so, they claim, "in the name of universal generalities thought in the Western way of thinking, and with no consideration for our cultural reality." As a result, those following the path of Césaire's négritude had been exhausted by indulgence in "a really suspended writing, far from the people, far from the readers, far from any authenticity except for an accidental, partial, and secondary one" ("In Praise" 889)

Sylvia Wynter - "A Different Kind of Creature": Caribbean Literature, the Cyclops Factor and the Second Poetics of the Propter Nos [Annals of Scholarship, Vol. 12 (1/2): 153-172, 1997]

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amant art campus, East Williamsburg, Brooklyn

Amant art campus East Williamsburg, Brooklyn Building, NYC Architecture Photos, New York City

Amant art campus, East Williamsburg, Brooklyn, NY

May 7, 2021

Design: SO–IL

SO – IL Designed ‘Art Campus’ Amant in Brooklyn Opens This Summer with Solo Exhibition by Grada Kilomba

Interdisciplinary, Research-based Artist Residency Begins This Fall

Amant exterior, under construction, April 2021:

photograph Courtesy the Amant Foundation

Amant art campus in Brooklyn, New York

BROOKLYN, NY – May 2021 — The Amant Foundation is pleased to announce that on June 5th it will open the doors on Amant, a 21,000 square foot multi-building “art campus” in East Williamsburg, designed by the award-winning architecture firm SO–IL. The complex will serve as Amant’s new headquarters, as well as the home for its exhibitions, public events, archival projects, performances, and residency program. Conceived as a research and process-oriented platform, Amant provides a public forum that presents and supports the practices of both established and under-recognized artists working across diverse creative fields.

Amant will open with a survey of work by Grada Kilomba (b.1968), the Portuguese artist, writer and academic of West African descent whose work deals with the difficult legacies of slavery and the colonial past. It will mark Kilomba’s first show in the United States.

The Amant Foundation made its debut with the launch of its Siena residency in the summer of 2020. The foundation is the vision of philanthropist and art collector Lonti Ebers, with the Brooklyn programs to be spearheaded by Artistic Director Ruth Estévez, former Gallery Director at REDCAT in Los Angeles and Senior Curator at Large at the Rose Art Museum. She is also the co-curator of the 34th São Paulo Bienal, which opens this fall.

The New York residency will welcome its first group of four artists in September and will host similarly sized groups three times a year. While its summer residency in Siena is geared towards mid-career artists as a “working retreat,” the Brooklyn program is research-focused, facilitating cross-discipline collaborations between Amant’s residents.

“The idea behind Amant was to create studios and exhibition spaces that would encourage artistic research and experimentation, free of the time restrictions and financial and administrative confines that typically accompany art practices in New York,” said Ebers.

Amant’s program will focus on research-based projects that do not always neatly fit into pre-existing systems of artistic and cultural production. Forthcoming collaborations include a commission by Gala Porras-Kim exploring current practices in the restitution and repatriation of cultural objects, and a new work by New York-based filmmaker Manthia Diawara depicting a series of hypothetical conversations between Martinican poet Édouard Glissant and thinkers of the African diaspora, drawn from Diawara’s own archive.

“At a moment when New York is still reeling from the pandemic, Amant wants to stress the importance of human relations,” said Estévez. “We want to provide opportunities to seed long-term cohesion between artists and audiences, supporting a tissue of intellectual, creative and emotional togetherness.”

Most of Amant’s time-based programming will occur at Géza, a 1800-square foot multipurpose building on campus for performances and screenings. In the fall, as conditions permit, Géza will host a screening series featuring Grada Kilomba, Olivia Plender, Dora García, and Clara Ianni, whose cinematic works dissect and re-assemble history through found footage, news archives, and other epistolary documents and ephemera.

Grada Kilomba: Heroines, Birds and Monsters

June 3 – October 3

Amant’s gallery spaces will host three exhibitions in 2021. The first, on view from June 3 through October 3, is the first solo exhibition of Berlin-based artist Grada Kilomba in the United States, presenting her unique form of storytelling. Working with theory, performance, film, and literature, Kilomba reveals the narratives of the colonial past, giving space to the silenced voices whose traumas are ever present. In her own words: “What if history has not been told properly? What if our history is haunted by cyclical violence precisely because it has not been buried properly?”

Kilomba’s work is showcased across three of Amant’s buildings, transforming them into a theatre stage where characters, gestures, words, sounds and props unfold into a hybrid body, exchanging roles and staging a new dramaturgy that traverses geographies and temporalities.

In the exhibition’s centerpiece, A World of Illusions (2017-2019), Kilomba radically reinterprets three well-known Greek myths to expose the unresolved tragedies of the postcolonial condition. Drawing on her academic background in psychoanalysis, the artist dedicates Narcissus and Echo to the politics of invisibility and Oedipus the King to the politics of violence, while the tragedy of Antigone exposes the politics of erasure and the importance of ceremonial memory. Combining music, mime, and dance, she re-stages the fables through African traditions of oral storytelling —the Griot— and building on analogies to the modern patriarchal system through the inclusion of a postcolonial lens.

The trilogy reincarnates as a sequence of photographs with the shared title of Heroines, Birds and Monsters (2020), portraying the female protagonists in a sculptural pose. In The Desire Project (2016) the representational image disappears entirely, with text displayed as the only visual element, accompanied by musical rhythms substituting for the narrator’s voice. The concluding work, Table of Goods (2017), a sculpture born out of ritual-performance, presents as both an object and landscape of the whole exhibition. The trans-atlantic trade between Europe, America, and Africa—sugar, coffee, cacao–are interred in a pile of soil. Kilomba displays these extracted materials as a burial, a symbolic ritual of remembrance of the slave trade as historical trauma, of which the consequences on the psyche are yet to be thoroughly explored.

Heroines, Birds and Monsters applies a new poetic, theoretical, and political framework to the colonial past, and the ways by which these narratives continue to embed themselves.

“Retelling history anew and properly is a necessary ceremony, a political act. Otherwise, history becomes haunted. It repeats itself. It returns intrusively, as fragmented knowledge, interrupting and assaulting our present lives.” – Grada Kilomba

Interior of Amant’s performance space Géza, under construction:

photo : Naho Kubota. Courtesy SO-IL and the Amant Foundation

The Space

Amant’s home in New York is a research and artistic platform spread across four different buildings in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn at 315 Maujer Street, 306 Maujer Street, and 932 Grand Street, with construction projected to conclude in May 2021. Flexibility is of deep pragmatic and conceptual importance for Amant, which, due to its interdisciplinary program, requires its premises to fulfill multiple purposes.

“With the design of the Amant campus we introduce a more humane grain and texture to the industrial neighborhood,” said SO–IL. “Both robust and intimate, we believe the complex of buildings will offer an oasis for creative thought and production, as well as an inviting and intriguing environment for visitors.”

Designed by architectural firm SO–IL as an “art campus,” the new space includes exhibition galleries, a bookstore, a courtyard garden and a multifunctional space dedicated to moving images and live art. The overall complex allows for an internal networking of activities while connecting, spatially, with the dynamics of the surrounding neighborhood. SO–IL’s design is both a new landmark and a seamless addition to East Williamsburg. Their intimate reinterpretations of materials like concrete, brick, and steel were conceived with Amant’s industrial surroundings in mind.

The main entrance is located in the center of the complex at 315 Maujer Street, which houses Amant’s offices and a daylit, 22 ft. tall gallery space. Across the courtyard at 932 Grand Street, what was once a marble shop has been converted into a vast second gallery space spanning over 2,000 square feet, in addition to a cafe and bookstore.

To the south at 306 Maujer is a dedicated studio building for residents featuring a large communal meeting area, library, and dining space, encouraging social exchange. Four daylit studios occupy the floor above. Walkways at the east and west perimeter lead to a second concrete volume housing Géza, a 1,800 square foot multipurpose space for performances and screenings.

Amant exterior, under construction, April 2021:

photo Courtesy the Amant Foundation

Residency

In September, Amant’s Brooklyn campus will welcome its inaugural group of national and international residents. The four artists will come from a wide range of artistic fields and reflect Amant’s commitment to geographic diversity. Residencies take place three times a year and form the heart of Amant. The New York residency is open to artists at all stages of their careers, with the sole restriction that residents may not already live in New York.

With a focus on research, rather than production and fabrication, residents will enrich their creative practices by observing, absorbing, and listening to the many perspectives, lived experiences, places, and communities that New York has to offer. More specifically, the residency will foster an active dialogue between local art and academic institutions, art professionals, and cultural producers. Additionally, the Amant residency will emphasize engagement with informal centers of knowledge often overlooked by the art historical canon or wider historical record.

The selection process prioritizes artists who require resources for long-term research and archival work, in line with Amant’s ethos of supporting thoughtful, experimental practices that “slow down” and ease the time pressures of the art production process.

In addition to individual studio space at 306 Maujer, each resident will receive a $3,000 monthly stipend, and Amant will cover the cost of transportation to and from New York.

Amant Founder and CEO Lonti Ebers with Artistic Director Ruth Estévez on site at Amant, March 2021:

photo: Lyndsy Welgos. Courtesy the Amant Foundation

About Ruth Estévez

Ruth Estévez is a curator and stage designer. She is the co-curator of the 34th São Paulo Biennial, which opens in September 2021. From 2018 to 2020 she was Senior Curator-at-large at the Rose Art Museum in Waltham, Massachusetts and curator of Idiorhythmias, the performance program at MACBA in Barcelona. She was Redcat Gallery Director in Los Angeles and Chief Curator at the Carrillo Gil Museum in Mexico City, where she also founded LIGA, Space for architecture (2010-), a non-for-profit platform focused on spatial practices.

About Lonti Ebers

Lonti Ebers is a long-time art collector and supporter of contemporary art. Lonti hired the renowned architectural firm SO–IL to design Amant’s innovative performance and art complex. Lonti has served on the boards of several museums in both the US and abroad and is currently a trustee of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMa), serves on the board of the Centre for Curatorial Studies at Bard College in Upstate New York, and sits on the European Committee of the Tate Gallery in London.

SO – IL

Amant art campus, East Williamsburg, Brooklyn building images / information from Amant

Location: Brooklyn, New York City, NY, USA

Brooklyn Buildings

Brooklyn Buildings

Brooklyn Architecture Designs

74Wythe In New York City

image courtesy of architect

74Wythe Williamsburg

Brooklyn Bridge Competition Entry

Design: Daniel Gillen

image courtesy of architect

Brooklyn Bridge Competition Entry

Apple Store, 247 Bedford Avenue, Williamsburg

Design: Bohlin Cywinski Jackson Architects

photo : Nick Lehoux

Williamsburg Apple Store Brooklyn

Williamsburg Hotel, Brooklyn, NY

Architects: Oppenheim Architecture+Design

render from architects

Williamsburg Hotel Brooklyn

New York City Architecture

Contemporary New York Buildings

Manhattan Architectural Designs – chronological list

New York City Architecture Tours by e-architect

New York Architecture News

432 Park Avenue Skyscraper

Design: Rafael Viñoly Architects

image © dbox for CIM Group & Macklowe Properties

432 Park Avenue Tower New York

Comments for the Amant art campus, East Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York City page welcome

The post Amant art campus, East Williamsburg, Brooklyn appeared first on e-architect.

0 notes

Text

"The psychoanalysts say that nothing is more traumatizing for the young child than his encounters with what is rational. I would personally say that for a man whose only weapon is reason there is nothing more neurotic than contact with unreason."

BLACK SKIN, WHITE MASKS by frantz fanon

#black skin white masks#frantz fanon#anticolonialism#antiracism#philosophy#psychology#african literature#martinican literature#martinique#french literature#blackness#autism#neurosis#mental illness#reason#abuse#trauma

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Review: Cahier d’un Retour au Pays Natal – by Aimé Césaire Aimé Césaire is the father of Martinican literature. In his Cahier, he explores his roots in his native Martinique and looks with an often angry voice at the repression of his fellow islanders.

#aimé césaire#black literature#cahier#cahier d&039;un retour au pays natal#caribbean literature#colonialism#french empire#martinican#martinique#negredom#negritude#slavery#translation

0 notes

Text

YE NOUCHI

Beaux-Arts Architecture Culture Antagonist Movement

The Marriage of History from Belle Époque (Monte Carlo) et Colonial West Indies (Martinique) & Congo Belge but thé Séparation for Côté d'Ivoire from Afrique.

Political

Nationalist

Planetary intelligence Pluto-Uranus

Carolingien Mirrors of Princes Literature Studies

Belgium Monetary Zone

Belgian rule in the Congo was based on the "colonial trinity" (trinité coloniale) of state, missionary and private-company interests.[9]

Union Minière du Haut-Katanga primary product was copper, but it also produced tin, cobalt, radium, uranium, zinc, cadmium, germanium, manganese, silver, and gold.

Antillianité Identity Theory

From the early 1960s, a new way of envisaging French West Indian identity began to be articulated by a number of Martinican thinkers, which, in contrast to Négritude's stress on the retention of African cultural forms in the Caribbean, dwelt rather on the creation, out of a multiplicity of constituent elements, of a specifically West Indian cultural configuration to which, in time, the name "Antillanité" came to be given.

Dancehall

Colonial France (New France et West Indies)

Artisan Plantation Économique instead of Rural Areas

Maifan Rivers (St. Lawrence River)

Sport

Coup d’Pied et Juplier Pro League

Contracts

Share Appreciation Right Plans (SAR Plans)

Under SAR Plans, the corporation grants plan participants share appreciation rights. Each SAR entitles participants to receive, on vesting, the net value of the increase in the market value of the corporation’s share between the grant date and the vesting date. Share Appreciation Right Plans are similar to stock option plans in some ways, and to RSU Plans in others:

Value. Share Appreciation Rights function much like stock options in many ways – but unlike stock options, participants aren’t required to pay the exercise price when they exercise the SAR. Share Appreciation Rights start with a nil value at the time of grant, so will have no value at vesting if the market value of the shares has decreased between the dates of grant and of vesting.

Plan Terms. Share Appreciation Right Plans typically contain provisions similar to those of RSU Plans in respect to plan administration, maximum shares reserved for issuance, grant agreement, market value, employment, share capital adjustments, change of control and shareholder agreements.

Vesting. Like RSU Plans, vesting provisions in SAR Plans can also be based on time, performance or both. Performance-based SARs are sometimes called “performance appreciation rights” or “PARs”. Once vested, the plan participant can settle the SARs in cash or in an amount of shares that equals the amount payable to the participant divided by the per share market value

Deferred Compensation

Deferred compensation refers to that part of one’s contribution that is withheld and paid at a future date. Retirement plans and employee pensions are examples of deferred compensation. Employers usually withhold a fraction of employees’ compensation every month, accumulate it over time, and pay the lump sum amount on a date previously agreed upon in the employment contract.

Pill Press

Suicide Tuesdays Levelling Effect et Placebo Effect

Didier Drogba

0 notes

Quote

[…] do I not have the right to be alone between the wall of my bones?

Aimé Césaire, from And The Dogs Were Silent (tr. by A. James Arnold & Clayton Eshleman), 1958

559 notes

·

View notes

Video

Let us glorify and uplift ancestors who wanted to elevate our people and countries. Join us Feb 27th, 2020 @wordupbooks we celebrate and ReImagine true independence and freedom from tyranny. No one captured the era’s Haitian-Dominican solidarity better than poet Jacques Viau Renaud. Born in Port-au-Prince in 1941, he was part of a modestly middle-class family that moved to Santo Domingo in 1948. As a young man, Viau met the artists, writers, and poets of the Generación del Sesenta (the Sixties Generation), known for their progressive inclination. His poetry was shaped by two major aesthetic and political movements taking place at the time: first, by the emergent Afro-affirming, anticolonial literary and philosophical scenes led by Jean-Price Mars, a Haitian intellectual, and Martinicans Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon; and second, by the Marxist and internationalist views espoused by his compatriot Jacques Stephen Alexis, a celebrated Haitian novelist. The artists of the Generación del Sesenta whom Viau knew as a young man—including Antonio Lockward Artiles, Miguel Alfonseca, and Silvano Lora—shared these internationalist and anticolonial ideas, a pride in African heritage, and a rekindled notion of Haitian-Dominican friendship. They organized in groups with such telling names as El Puño (“The Fist”) and La Isla (“The Island”). La Isla, led by Viau’s close friend Antonio Lockward Artiles, in particular, actively promoted solidarity between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. These anticolonial, Marxist, and Afro-affirming views informed Viau’s poetry, which also addressed events taking place beyond the island. The poem “A un líder negro asesinado” (To a Murdered Black Leader), for example, was written in homage to U.S. civil rights activist Medgar Evers upon his assassination in 1964. It offers poignant testimony to a pan-Africanism that was in tune with events beyond Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and shows the impact that the U.S. civil rights movement had outside the United States. It also reflects an international current of writers and artists who engaged politically and used their art and literature as tools for political rebellion. https://www.instagram.com/p/B8u4CLzlOQU/?igshid=lqtgwfy6u0li

0 notes

Text

Should we be troubled by the fact that, until efforts were made recently to reintroduce parrots to Martinique, there were no endemic species left on the island? How much should we grieve for the Cuban Red Macaw? Should we mourn the Caribbean monk seal? [...] Hostages to the economic demands of metropolitan centers not always aware of the environmental damage caused by their policies [...], the islands of the Caribbean have experienced successive waves of ecological assault chronicled in fiction and nonfiction alike through countless narratives of extinction. [...] [I]n June 2008 the monk seal finally joined the growing list of victims of ecological changes unleashed by colonialism and postcolonial tourism development in the Caribbean basin. [...] The Caribbean is (alas!) one of the world’s hotspots [...] [w]ith around 7,000 species of plants and 160 bird species found nowhere else in the world [...]. The Caribbean region’s subordinate entry into global mercantilism in the sixteenth century continues to haunt us. [...] The history of fauna extinctions as recorded in the literature of the Caribbean region chronicles the impact of [...] “slow violence [...].“

-----

Barbados, one of the earliest plantation settlements in the Caribbean, is perhaps the best example of the impact of habitat collapse in the region in the first centuries of the European conquest. Colonized by English Royalists sent “beyond the sea” by a victorious Oliver Cromwell in the early seventeenth century, it was completely deforested in a little over twenty years as planters submitted nearly 80 percent of the landmass to sugar cultivation -- a fate that the small colony would quickly share with neighboring islands. As Shawn Miller explains in An Environmental History of Latin America:

Scores of plants, mammals, reptiles, and birds were unique to each island, an an uncounted number of species, possibly ranging in the thousands, without their forest habitats, disappeared forever without [...] notice. On Barbados, a few deletions were noted: the palmito palm, the mastic tree, the wood pigeon, a few species of conures, the yellow-headed macaw, and one variety of hummingbird -- all vanished. No monkey species survived sugar’s colonization, and of the 529 noncultivated species of plants found on Barbados today, only 11 percent are native to the island.

-----

Throughout the Caribbean, deforestation to clear the land for sugar plantations led to the loss of a variety of unusual native rodents like the hutia and shrew-like insectivores, many of them ancient species that have now not been seen for centuries. The Martinican Amazon parrot became extinct due to habitat loss as the island was cleared for agriculture in the seventeenth century; it has not been recorded since 1722. In 1699, Pere Labat [...] described a large population of small parrots living on Guadalupe, named Arantiga labati [...], of which no specimens have been recorded since the mid-eighteenth century. Fifteen mammals have become extinct in Hispaniola [...] due to the severe deforestation of Haiti. Jamaica was home to a monkey, the Xenothrix mcgregori, lost when its forest habitat was cut by European colonists. It died out in the 1750s. The Cuban Red Macaw was reasonably common around 1800 in Cuba. Human encroachment in its habitats increased dramatically in the early nineteenth century, when Cuba intensified its sugar production to meet the demand created by the collapse of the St. Domingue sugar mills after the Haitian Revolution. [...] The last one is believed to have been shot in 1864 at La Vega in the vicinity of the Cienaga de Zapata swamp [...]. Nine species of Antillean iguanas and snakes became extinct after Europeans introduced mongoose and rats to protect sugar cane workers in the nineteenth century, joining the uncounted species that have disappeared due to the introduction of [...] species. [...] In 2008, the Caribbean monk seal (Monachus tropicalis ...) -- the only subtropical seal native to the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico -- was declared officially extinct [...].

-----

The concern for the impact of biodiversity loss in writings about the Caribbean can be found in some of the earliest literary and proto-literary texts written about the region. [...]

Aphra Behn, in her novel Oroonoko, published in 1688, already pondered what the increasingly intense clearing of the Caribbean forests would mean for the Indigenous peoples and animals relegated to the diminishing woods. Behn’s sojourn in Suriname in 1653 coincided with what has been called “The Great Clearing,” the period between 1650 and 1665, marked by devastating deforestation throughout the British and French Caribbean [...] particularly for refining the sugar. [...] At the dawn of the eighteenth century, Pere Labat [...] written at a time of fast plantation development in Martinique and Guadalupe, writes of his concerns with the loss of biodiversity. In Guadalupe he had encountered the diablotin, an ungainly bird the size of a pullet that lived in “a hole in the mountains, like rabbits.” [...] Their trajectory as a species had already been inexorably derailed by colonial agricultural expansion [...].

-----

Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert. “Extinctions: Chronicles of Vanishing Fauna in the Colonial and Postcolonial Caribbean.” 2014.

194 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOUCHI

Beaux-Arts Architecture Culture Antagonist Movement: The Marriage of History from Ligurians (Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur et Monte Carlo) et Colonial West Indies (Martinique) & Colonial West Africa but thé Séparation for Côté d'Ivoire from Afrique.

Political: Nationalist, Planetary intelligence Pluto-Uranus, et Carolingien Mirrors of Princes Literature Studies

PACA Éducation: Education, for its part, is well developed with the region's various universities, international schools, preparatory classes for specialist university courses, and engineering and business schools.

Antillianité Identity Theory: From the early 1960s, a new way of envisaging French West Indian identity began to be articulated by a number of Martinican thinkers, which, in contrast to Négritude's stress on the retention of African cultural forms in the Caribbean, dwelt rather on the creation, out of a multiplicity of constituent elements, of a specifically West Indian cultural configuration to which, in time, the name "Antillanité" came to be given.

Colonial West Indies et West Africa: Artisan Farming

Sport: Coup d'Pied et Juplier Pro League

Jaques Samassi

0 notes