#replication crisis

Text

Recommendations to meditate, exercise, and pursue nature for happiness rely on weak evidence

According to a new paper in Nature Human Behavior, media reports most often recommend five strategies for happiness: expressing gratitude, increasing social interaction, practicing mindfulness meditation, exercising, and spending time in nature. Over the past decade, journalists have repeated these recommendations so often that they have begun to sound almost like simple common sense.

But the media has relied on studies published before the field of psychology began to reckon with a so-called “replication crisis,” write the authors of the paper, Canadian psychologists Dunigan Folk and Elizabeth Dunn from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. Around 2011, scientists began to notice that a majority of psychology studies could not successfully obtain the same results when repeated. Researchers in the field, it turned out, consistently relied on weak research methods, such as selective reporting of results, exclusion of certain participants, and small sample sizes—too few participants to yield statistically significant results.

“It would be easy to assume there is a strong base of evidence for these [happiness] strategies,” write Folk and Dunn, “given the frequency with which they are recommended.” But while the five happiness tips may not qualify as snake oil, exactly, their benefits at this point are theoretical at best and their success with any one person may depend heavily on individual personality or preferences.

To assess the validity of the big five happiness strategies, Folk and Dunn identified 532 studies that experimentally investigated them with a non-clinical population. When they reviewed this batch of studies, they found that the vast majority used too few participants to yield reliable findings and failed to “pre-register” their studies—a research method that aims to improve data quality, prevent cherry-picking, and reduce publication bias, which is the publication of studies that fail to find an effect—among other things.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Started reading Robert Cialdini's Influence: Science and Practice. And it's a book drawing on social science which was written before 2010, which has it on thin ice going in. And then in the first few pages it cites (1) a study by Dan Ariely and (2) that study about the copier.

Not off to a good start!

#robert cialdini#statistics#replication crisis#influence: science and practice#dan ariely#Predictably Irrational#copier study

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

By: Marilyn Singleton

Published: Feb 22, 2023

Marilyn Singleton is a board-certified anesthesiologist and a visiting fellow at the medical advocacy organization Do No Harm.

I’ll never forget my parents’ reaction when I was accepted to the University of California at San Francisco’s medical school. Having attended segregated schools, my mother and father were thrilled that their daughter would attend a fully integrated, top-tier institution.

When I graduated with a medical degree in 1973, a Black woman in a class of mostly White men, there was a real sense that the days of obsessing over skin color and making race-based assumptions about our fellow human beings was finally fading — and, hopefully, soon gone for good.

Apparently not. That racial obsession has come rushing back — in academia, politics, business and even in my beloved medical profession. But now it’s coming from the opposite direction. The malignant false assumption that Black people are inherently inferior intellectually has been traded in for the malignant false assumption that White people are inherently racist.

That is the basic message conveyed by “implicit bias training,” which is now mandatory for California physicians; it is a message that I believe is harmful both to physicians and patients. There is a sad irony in all this, because the misguided focus on racism is intended to improve the health and well-being of Black patients in particular.

The law, which took effect last year, includes other bias targets, including gender identity, age and disability. But in practice, such training — a mainstay of the diversity and inclusion industry, worth an estimated $3.4 billion in 2020 — is overwhelmingly about race.

In California, where I’ve been licensed since 1974, every physician is required by law to participate in this racially regressive practice. Doctors must take implicit bias training not just once but as part of the curriculum of “continuing medical education,” for at least 50 hours every two years, required for their medical license renewal.

The training’s focus is on exactly what the name suggests: deeply ingrained prejudice toward people of different races. There is no room for debate, for the law states baldly: “Implicit bias, meaning the attitudes or internalized stereotypes that affect our perceptions, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner, exists.”

And the law asserts as fact that implicit bias is responsible for “racial and ethnic disparities in health care,” particularly for Black women.

I am so disturbed by the state’s mandate that, so far, I have balked at the training. But I know that I must comply before the end of 2023 if I wish to have my medical license renewed.

Many of my friends and colleagues ask why I’m so upset by the law. Clearly, implicit bias training isn’t meant for me. It’s aimed at White people, who are far and away the biggest share of the medical profession. My answer is simple. I reject the unscientific accusation that people are defined by their race, not by their individual beliefs and choices. It is little consolation that studies are finding implicit bias training has no effect on its intended targets, and might even make matters worse.

Think about the message this mandate sends to Black physicians. It suggests that I should be wary of my White colleagues because, after all, they’re biased against people like me. Sure, they can undergo frequent training, but their bias is always going to be there, beneath the surface, threatening to rear its ugly, racist head. Collegiality and collaboration — two essential components of high-quality medical care — are targeted by this mandate. Call that an implicit bias.

Since I became a physician, I have seen exactly one instance of racism in health care — and it was from a patient, not a fellow physician. As for my colleagues, I have been consistently impressed with the conscientious, individualized care they have provided to patients of every race and culture. When we all took our oath to “first, do no harm,” we meant it, and we live it. I can’t imagine spending my entire career thinking my peers can’t uphold that oath without constant racial reeducation.

The message to physicians is bad enough, but the message to patients is much worse. Black people are, in effect, being told that White physicians are likely to quite literally damage our health. If that’s the case, why on earth would you seek medical care, unless you could be absolutely certain of not being treated by a White physician? And if you do seek medical care, why wouldn’t you doubt every word from a White doctor who is inherently prejudiced against you?

The whole point of implicit bias training is to create better health outcomes for Black patients and others who might be the target of discrimination, but the opposite seems more likely. It fosters a climate of distrust and resentment that threatens to undermine the medical and moral progress I’ve seen over the decades. When I graduated from medical school, we were moving past the era of racial obsession and anger. Why are we going back to the days when race defined so many lives and dimmed so many futures?

[ Via: https://archive.is/dAu17 ]

==

Reminder: The virtue theater of “implicit bias training” is as pseudoscientific as homeopathy, phrenology, thetan cleansing and demon possession. Even the creators admit that it is:

https://faculty.washington.edu/agg/pdf/Greenwald,Banaji&Nosek.JPSP.2015.pdf#page=5

“problematic to use [it] to classify persons as likely to engage in discrimination,” and “attempts to diagnostically use such measures for individuals risk undesirably high rates of erroneous classifications.”

https://musaalgharbi.com/2020/09/16/diversity-important-related-training-terrible/

https://dailynous.com/2017/01/12/reconsidering-implicit-bias/

https://www.freedomcast.us/iopod/episode1

https://www.thecut.com/2017/01/psychologys-racism-measuring-tool-isnt-up-to-the-job.html

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/rabble-rouser/202203/12-reasons-be-skeptical-common-claims-about-implicit-bias

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5186d08fe4b065e39b45b91e/t/601766eb09286e6fda49d962/1612146411820/PaluckPoratClarkGreen_2020.pdf

https://xlab.berkeley.edu/connect/Intersectional%20Implicit%20Bias%20Pre-Print.pdf

https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2017/12/iat-behavior-problem.html

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25402677/

The only things it reliably does is signals virtue, creates an obsessive fixation on categories, divides co-workers, and makes snake-oil sellers billions of dollars in an industry that, like the church, sells an imaginary product.

This new law, then, functions as a form of compulsory faith-based ritual. Hopefully someone will sue the pants off the relevant bodies for holding medical licensing hostage to compliance with compelled religious practice.

#Marilyn Singleton#implicit bias training#implicit bias#implicit association test#replication crisis#snake oil#social homeopathy#social phrenology#medical corruption#medical malpractice#corruption of medicine#cult of woke#virtue theater#woke#wokeism#woke activism#wokeness as religion#religion is a mental illness

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are the criticisms of psychological measurement fundamentally flawed or are psychologists indeed not measuring anything, in spite of appearances?

0 notes

Text

youtube

Huh.

Who could have guessed that a Psychologists studies were faked and couldn't be replicated?

Yet again.

1 note

·

View note

Text

the idea:

we're currently in an extremely difficult period in scientific research because many classic studies haven't proven replicable later by other researchers. this is particularly prevalent in the more human-based fields (ex: psychology, sociology, social anthropology, and economics) because it's especially difficult to isolate variables. but the replication crisis is a broad problem across most scientific disciplines for other reasons, such as the pressure for published research caused by both academic institutions and private medical research companies. this is also related to bonini's paradox, "all models are wrong", and the more general concept of the map-territory relation: it's extremely difficult to build a model or hypothesis that is true for a specific study population yet still useful and relevant when trying to generalize to a broader population.

0 notes

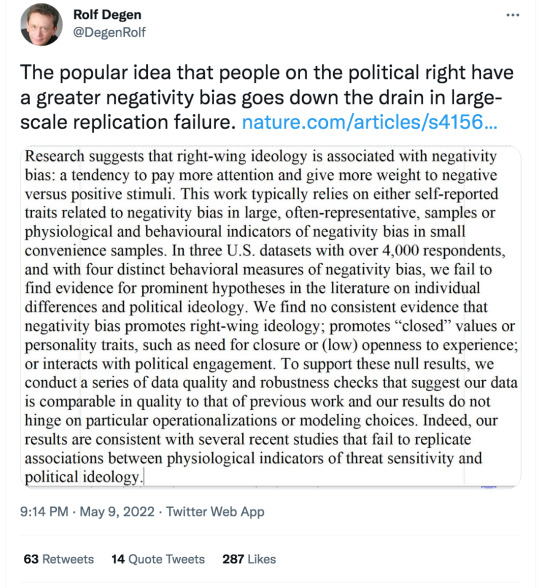

Photo

(link)

0 notes

Text

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

smile for the camera!

crisis belongs to @amyupup47

#art#illustration#my art#fanart#crisis#errormare ship kid#TAKE THIS AMY!!!! you sweet sweet little goose >:'Dc#i've been planning on drawing you something for weeks now i can't believe i sat down and finally made something HHH >:'D#side note just aughgh i normally would be satisfied with the end result but dude.#DUDE you won't believe how hard replicating the swag your ocs have in my style iss WAA i can't draw hoods for the life of me hhh#hope i did the lil bean justice >:') his design is so warm!!! loved working with his colors<333#your art is crazy good too btw can't believe you don't hear this daily but GHGHGHG HOW DARE YOU HAVE SO MANY BANGER STYLES OMG!!!#you say you don't have a consistent one as if you don't have the insane power of turning your art into whatever you like and STILL#still SOMEHOW keeping the little things that make me go 'oh! that's amy's art!' which is BONKERS. you powerful evil WIZARD#have a nice day buddy muah muah muah muah muah (FIVE TIMES as payback<3333)

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

What’s your pettiest DC opinion? Like, a little detail that arguably Doesn’t Really Matter in the grand scheme of things story wise but seeing it or not seeing it still annoys you? (Mine is Jim Gordon’s wife AND daughter both being named Barbara. No. There is one Barbara Gordon don’t do this to me.)

I mean I guess he and Barbara are just kind of weirdoes like that because their firstborn is also named... James...

But I dunno how good a gauge I have on how petty my DC opinions are--like there's fandom complaints (AKA "Clark having his DNA stolen when he was fucking dead doesn't automatically make him obligated to be a father figure to a clone that was literally designed to co-opt and profit off of his image, you weirdos") and then there's writing complaints ("What the hell was Final Crisis's actual goal with Mary Marvel--like how is this a character arc if she's like at least 40% possessed the entire time--is this some kind of weird extended metaphor for superpowers as addiction--why are there so many upskirt shots") I think a lot of the writing complaints can be shrugged off just by virtue of the naturally nebulous and writer-dependent nature of comics, y'know, "If you don't like it, you can find another run."

I guess... this isn't really 'petty' per se, but I feel like when it comes to their Elseworlds and Multiverse stuff, DC's kind of put itself into a hole where, like, because Elseworlds isn't the canonical universe, they feel this need to take things in as dark and shocking directions as possible and honestly that's gotten really tired and redundant. Dark Nights Metal, Tales from the Dark Multiverse, DC vs Vampires--like, if you look back at older Elseworlds titles, sure, you had some dark, high-body-count, end of the world stuff (Like Distant Fires---BOOO DISTANT FIRES, BOOOO WE HATE YOUR PUSSY), but for the most part a lot of the Elseworlds titles were about exploring how major setting changes and role swaps and shifts in characters' lives and development could affect familiar and well-known DC stories (Like Superman Inc and JLA: The Nail--YAAAAY SUPERMAN INC AND JLA: THE NAIL YAAAY WE LOVE YOUR PUSSY). I haven't read Dark Knights of Steel yet, but that one seems like a refreshing pump on the brakes from all the grimdark shit. But anyway, yeah--basically the assumption of, "If we're going to make this Elseworlds story memorable, we have to kill off SO MANY beloved characters"--like after a while it starts to feel like a child throwing a tantrum and kicking his toys around rather than telling a story.

Also bruh how many times are you going to kill off Martian Manhunter I mean REALLY. LEAVE HIM ALONE. JUST LET HIM HAVE HIS CHOCO COOKIES AND STOP SETTING HIM ON FIRE. BRO WHAT DID HE DO.

#to be fair The Nail does have a solidly high body count though#but IMO it does it right and so many of the other grimdark elseworlds stuff are weak attempts to replicate that success#dc#final crisis#distant fires#superman inc#JLA: The Nail#martian manhunter

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Bro how do you get over an art style crisis :(

i am always constantly in one myself so what i usually do is find another artist i like and just sort of take notes on how they do stuff.. be observant! smallest of changes can do drastic things for an art style. changing the technique and style of the eyes, noses, hands, clothing folds etc can do a lot even if its subtle.

i dunno... take note of how people shade too. or their sketching process. anything's useful to observe and replicate

#asks#when i mean Replicate i mean in privacy btw. copying is fine when its private#all artists copy. we copy from real life and other artists#usually when im in an art style crisis i just scribble#not saying much cus i only doodle anyway#and also.#do not worry about having an art style. draw however you like. as inconsistently as you like

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is still a Joseph Heath fanblog, but Enlightenment 2.0 has the inevitable flaws of an early-2010s book that draws on social science research that I have no odea how trustworthy any of it is.

Anyway I just reached the point where he's citing Brian Wansink experiments to make a point and I can't take it seriously even though the point is probably true.

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

By: Jesse Singal

Published: Dec 5, 2017

At the moment, you may have heard, the field of psychology is grappling with a so-called “replication crisis.” That is, certain findings that everyone had assumed to be true can’t be replicated in follow-up experiments, suggesting the original findings were the result not of actual psychological phenomena, but of various flawed methodologies and biases that have crept into the scientific process.

One of the major contributing factors to the replication crisis, which is centered mostly on social psychology, is human nature. Humans, being humans, do not like hearing that ideas they’ve worked on for a long time might have to get tossed in the bin, or at the very least revised significantly. That’s why some researchers — though by no means all of them — have responded to good-faith critiques of their work by attempting to derail the conversation, calling their critics crazy or mean or attributing to them dark ulterior motives. The researchers who attempt such derailings tend to be established, well-respected ones who have benefited from the old regime — the regime that led the field into its current, precarious situation, and which is now threatened by a growing reform movement.

The implicit association test, co-created by Harvard University psychology chair Mahzarin Banaji and University of Washington researcher Anthony Greenwald, is an excellent example. Banaji and Greenwald claim that the IAT, a brief exercise in which one sits down at a computer and responds to various stimuli, measures unconscious bias and therefore real-world behavior. If you score highly on a so-called black-white IAT, for example, that suggests you will act in a more biased manner toward a black person than a white person. Many social psychologists view the IAT, which you can take on Harvard University’s website, as a revolutionary achievement, and in the 20 years since its introduction it has become both the focal point of an entire subfield of research and a mainstay of diversity trainings all over the country. That’s partly because Banaji, Greenwald, and the test’s other proponents have made a series of outsize claims about its importance for fighting racism and inequality.

The problem, as I showed in a lengthy rundown of the many, many problems with the test published this past January, is that there’s very little evidence to support that claim that the IAT meaningfully predicts anything. In fact, the test is riddled with statistical problems — problems severe enough that it’s fair to ask whether it is effectively “misdiagnosing” the millions of people who have taken it, the vast majority of whom are likely unaware of its very serious shortcomings. There’s now solid research published in a top journal strongly suggesting the test cannot even meaningfully predict individual behavior. And if the test can’t predict individual behavior, it’s unclear exactly what it does do or why it should be the center of so many conversations and programs geared at fighting racism.

One striking thing about the process of reporting that article was the extent to which Banaji tried to smear her critics, suggesting to me in an email she believed that critiques of the test could be explained by the fact that the IAT “scares people who say things like ‘Look, the water fountains are desegregated, what’s your problem.’” She also accused the test’s critics of having a “pathological focus” on black-white race relations and the black-white IAT for reasons that “will need to be dealt with by them in the presence of their psychotherapists or church leaders.”

This is the definition of a derailing tactic — shift the focus from critiques of the IAT itself, some of which in this case appeared in a flagship social-psych journal, to the ostensible moral and psychological failings of the critiquers.

A couple days ago, Quartz published its own article on the IAT, by Olivia Goldhill. The article covers similar ground and comes to similar conclusions as mine, and adds some new insights and analysis: The headline, “The world is relying on a flawed psychological test to fight racism,” captures things pithily. Goldhill’s piece clearly shows that Banaji and Greenwald are still trying to deflect and derail rather than fully engage with the process of evaluating their test:

It’s highly plausible that the scientists who created the IAT, and now ardently defend it, believe their work will change the world for the better. Banaji sent me an email from a former student that compared her to Ta-Nehisi Coates, Bryan Stevenson, and Michelle Alexander “in elucidating the corrosive and terrifying vestiges of white supremacy in America.” || Greenwald explicitly discouraged me from writing this article. “Debates about scientific interpretation belong in scientific journals, not popular press,” he wrote. Banaji, Greenwald, and Nosek all declined to talk on the phone about their work, but answered most of my questions by email.

The idea that journalists shouldn’t write about scientific controversies would have been highly questionable even before the replication crisis exploded onto the scene, but it’s hard to fathom why anyone would take this argument seriously in 2017. After all, the replication crisis was spurred in part by opaque research and peer-review processes, by people not sharing data, by social and professional structures that sometimes had the effect of short-circuiting real debate about the merits of ideas — particularly popular ones of the sort that often get glowing write-ups in, well, the “popular press” (Greenwald, of course, doesn’t appear to have any problems with positive coverage of the IAT). Journalism, when it’s done well, can serve as a useful check on all these tendencies. To be fair, Greenwald isn’t the only one who thinks that science should only be critiqued by those very close to a given controversy — this is an idea that seems to sometimes pop up among defenders of the old, deeply flawed social-psychological ways — but that isn’t how things should work.

Even more surprising, though, is an email Greenwald wrote to Goldhill which read, “The IAT can be used to select people who would be less likely than others to engage in discriminatory behavior.” This might come across as a fairly banal defense of his research project, but it isn’t: It’s the continuation of a very slippery pattern I identified in my article.

As I noted, in their 2013 best seller Blindspot, which helped the IAT carve out an even bigger place in the public imagination than it had already achieved, Banaji and Greenwald wrote that the test “predicts discriminatory behavior even among research participants who earnestly (and, we believe, honestly) espouse egalitarian beliefs,” and “has been shown, reliably and repeatedly” to do so. In fact, this is a “clearly … established” “empirical truth.” But then, just two years later, they argued in an academic paper unlikely to be read by the general public that due to the test’s methodological weaknesses, it is “problematic to use [it] to classify persons as likely to engage in discrimination,” and “attempts to diagnostically use such measures for individuals risk undesirably high rates of erroneous classifications.”

I referred to this as a “Schrödinger’s test” situation in which the test both does and doesn’t predict behavior at the same time. When the test’s creators are addressing lay audiences unfamiliar with its problems, it does predict behavior; when they’re addressing academic audiences familiar with what is now a years-long controversy, they acknowledge that it doesn’t. Greenwald’s quote to Goldhill just marks the latest example.

In other words:

Banaji and Greenwald in 2013, to the public: Our test has been shown, reliably and repeatedly, to predict behavior.

Banaji and Greenwald in 2015, to academics: Our test doesn’t predict behavior.

Greenwald in 2017, to the public: Our test predicts behavior.

So, once more: I disagree with Greenwald. Society desperately needs more open scrutiny of scientific claims, not less, whether in scientific journals, the media, or anywhere else. Especially when it comes to claims that seem to change every two years.

==

“tHe IaT iS bAsEd On ScIeNcE!!1!”

No, it’s based on ideology, and perpetuated by a multi-billion dollar church of DEI through faith by priests whose careers don’t exist without it.

https://www.thecut.com/2017/01/psychologys-racism-measuring-tool-isnt-up-to-the-job.html

https://qz.com/1144504/the-world-is-relying-on-a-flawed-psychological-test-to-fight-racism/

https://musaalgharbi.com/2020/09/16/diversity-important-related-training-terrible/

https://www.vox.com/identities/2017/3/7/14637626/implicit-association-test-racism

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/rabble-rouser/202203/12-reasons-be-skeptical-common-claims-about-implicit-bias

The IAT is measuring your thetans, reading your aura, or determining your criminality by feeling the bumps on your head.

#Jesse Singal#implicit association test#implicit bias#mahzarin banaji#anthony greenwald#race#social psychology#psychology#human psychology#junk science#pseudoscience#pseudoscientific nonsense#replication crisis#psychological testing#academic fraud#academic corruption#race grifters#race grifter#social phrenology#religion is a mental illness

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is Psychology Self-Correcting? Reflections on the Credibility Revolution in Social and Personality Psychology

TL:DR — "No."

0 notes

Note

When it comes to historical research, do you research for things that DON'T exist? For example, foods that are common now but didn't exist in the average American restaurant or grocery in the '80s or '90's? Words, phrases, and entire concepts that are commonly accepted today but unheard of to the average American when Mav and Ice were at Top Gun?

Your writing is so unbelievably good.

not really because I don't care about food, I care about the literary device that is "taking communion." i.e. it doesn't matter what they eat, it only matters that they're eating together, for the plot.

And, okay, showing my little-kid bias, but was there actually stuff in grocery stores in the 80s/90s that wouldn't be there today/vice versa? brands might change, like okay Pringles might not exist but you still have potato chips; and obviously specialty stuff like what you find in your average Asian market might not be commonplace, but, like, were the 90s all that different from today, American-food-wise? its my assumption that they weren't, but I also wasn't alive in the 90s, so. Um, ectocooler Hi-C, maybe? that's the one 90s food I know.

attitudes of course are what change. today's concept of being so QUICK to publicly label sexual identities would be extremely foreign, for instance. obviously people did label their sexualities in the 80s & 90s, people were definitely calling themselves bisexual and such, but probably not the people ice & mav would be hanging out with, in the Reagan-era navy. which is what my fics are about. that's the whole point.

and, also, COMMUNICATION changes. I have never used a payphone in my whole life so I actually have no idea how they work. but they were ubiquitous "back then," and lend themselves to amazingly interesting conflict (omg I don't have enough change to call my boyfriend maverick who's mad at me!!!) which is why I lean on payphones so much in my writing. honestly, im gonna be real, the invention of the cell phone makes telling stories about miscommunication so much harder. instant-speed communication would make certain stories less interesting, which is why a lot of horror movies default to the "no cell service" trope to isolate their characters, or why some teen dramas have the characters reject cell phones on principle (Alyssa or James having a phone in 2017's "The End of the F***ing World" would solve most of their problems, which is why Alyssa smashes hers in the first five minutes and James basically says he views them as a cancer to society--if they had phones the story would be boring, so the writers took away their phones).

I also feel like people used to treat society differently "back then," i.e. Going Out was much more of a thing when there were 10 channels on TV and no one had cell phones, so you Went Out and had drinks & met strangers & interacted with general society to an extent im not sure we do anymore. So that experience is way more fun to write about in the 80s than today. (u can't see me but im seething with jealousy over ppl who were born in ~1965)

idk. im not sure I did a great job reproducing the zeitgeist of the 80s/90s in my fics, bc I wasn't there to have knowledge of what they were like. I got most of my presupposed knowledge about that time period from reading Calvin & Hobbes anthologies as a kid. oh well.

#I actively avoid talking about the aids crisis as much as I can for instance#that is certainly A Can of Worms.#a massive omission in my fics to be sure. but... not one I want to touch.#these characters would be judgmental and homophobic about it I fear.#btw I stole a bunch of stuff from teotfw for my fics#Carole asking ice if he actually wants maverick or if he just goes along with things is directly ripped from s1e02#favorite tv show of all time#top gun#edts notes#from Calvin and Hobbes I gather most people in the 80s were obsessed with hostess snacks like Twinkies etc.#and dieting consisted of chainsmoking cigs on the front porch#bloom county was also a truly informative comic strip re: my 1980s cultural education#just the way characters like opus/Steve/binkley talk for instance#people in the 80s just talk different from the way they do now#fun to try and replicate even if I can't put it into words#my god I love bloom county#my birthday is tmr I will finally be old enough to legally drink in the US 😋#thank u for the ask 🥺

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

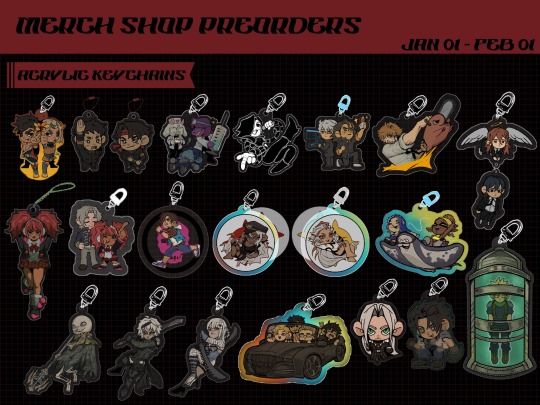

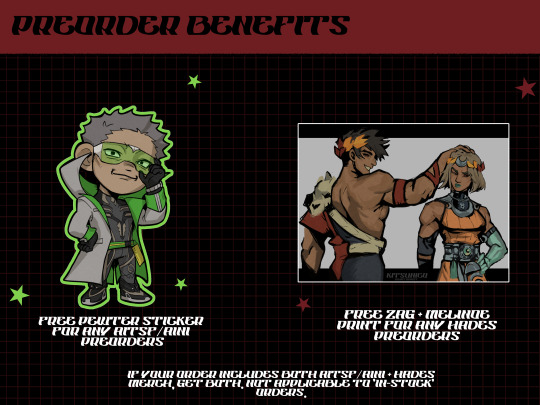

[rbs appreciated] SHOP 2.0 OPEN ‼️

SHOP LINK ⬅️

POs for my new merch are now open till Feb 1 Worldwide (Except for Europe atm). A lot of new stuff for the new year, please dm me if there's any questions.

Orders $35+ get free shipping. AITSF orders will get a free pewter sticker and Hades orders will get a free postcard of Zag and Mel ✨

#art#hades game#ai somnium files#ai nirvana initiative#mob psycho 100#mob psycho#chainsaw man#great ace attorney#ace attorney#nier replicant#nier#999#zero escape#deltarune#undertale#final fantasy#final fantasy vii#crisis core#final fantasy xv#13 sentinels: aegis rim#13sar#splatoon3#akiangel#persona 5#genshin impact#nico di angelo

60 notes

·

View notes