#source: isabella roberts

Text

instagram story: May 8, 2023

#cats korea tour 2022#source: isabella roberts#backstage cats#saverio pescucci#plato (cats)#admetus#taryn donna#cassandra (cats)#gavin eden#skimbleshanks#anneka dacres#demeter (cats)#petra ilse dam#bombalurina#xavier pellin#mr mistoffelees#mistoffelees#cian hughes#pouncival#carbucketty#katie hutton#rumpelteazer#isabella roberts#victoria (cats)#victoria the white cat#gabrielle parker#jemima (cats)#alice oberg#tantomile#george hankers

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Northanger Abbey Readthrough, Ch 10

Oh Isabella Thorpe, you delightful, ridiculous girl. You know if she was just a vacation friend she'd be fine; there are lower standards for vacation friends. Catherine and her would be close for a few weeks, be pen pals for a few months and then totally forget about each other. But no, she has to pull shit like this:

I assure you, my brother is quite in love with you already; and as for Mr. Tilney—but that is a settled thing—even your modesty cannot doubt his attachment now; his coming back to Bath makes it too plain.

Oh great, Thorpe is in love with Catherine. I also love how Mr. Tilney returning to Bath is absolute proof of his love. We will learn quite soon that it had nothing to do with Catherine at all, Henry went ahead to book lodgings.

Isabella "discovers" that she and James have exactly the same tastes, which I suspect was found in exactly the same way that Willoughby "discovered" that Marianne shared all of his:

We soon found out that our tastes were exactly alike in preferring the country to every other place; really, our opinions were so exactly the same, it was quite ridiculous!

Their taste was strikingly alike. The same books, the same passages were idolized by each—or if any difference appeared, any objection arose, it lasted no longer than till the force of her arguments and the brightness of her eyes could be displayed. He acquiesced in all her decisions, caught all her enthusiasm; and long before his visit concluded, they conversed with the familiarity of a long-established acquaintance. Sense & Sensibility, Ch 10

This also seems to be how Lucy Steele won over Robert Ferrars and how Caroline Bingley is attempting to secure Darcy. James is certainly falling for it, so it must work some of the time. There you go, A+ dating advice, just like everything they like!

Isabella claiming that, "I know you better than you know yourself" to Catherine seems to be grating our heroine a little. Of course, despite massive hints Catherine still doesn't seem to get that Isabella is gunning for James, but Catherine also dislikes being assumed to be improper. We see that Catherine does try very hard to do the right thing, though Mrs. Allen isn't the best source of guidance.

Catherine becomes a third wheel:

They were always engaged in some sentimental discussion or lively dispute, but their sentiment was conveyed in such whispering voices, and their vivacity attended with so much laughter, that though Catherine’s supporting opinion was not unfrequently called for by one or the other, she was never able to give any, from not having heard a word of the subject.

before running off to speak to Miss Tilney.

“How well your brother dances!” was an artless exclamation of Catherine’s towards the close of their conversation, which at once surprised and amused her companion.

"Artless" comes up a lot in Austen's works, and it's generally a good thing. It's like the opposite of conniving. Here are some examples:

The next morning brought another short note from Marianne—still affectionate, open, artless, confiding—everything that could make my conduct most hateful. - Willoughby, Sense & Sensibility

Fanny’s feelings on the occasion were such as she believed herself incapable of expressing; but her countenance and a few artless words fully conveyed all their gratitude and delight, and her cousin began to find her an interesting object.

Mrs. Price’s manners were also at their best. Warmed by the sight of such a friend to her son, and regulated by the wish of appearing to advantage before him, she was overflowing with gratitude—artless, maternal gratitude—which could not be unpleasing. -Mansfield Park

She was not struck by any thing remarkably clever in Miss Smith’s conversation, but she found her altogether very engaging—not inconveniently shy, not unwilling to talk—and yet so far from pushing, shewing so proper and becoming a deference, seeming so pleasantly grateful for being admitted to Hartfield, and so artlessly impressed by the appearance of every thing in so superior a style to what she had been used to, that she must have good sense, and deserve encouragement.

An unpretending, single-minded, artless girl—infinitely to be preferred by any man of sense and taste to such a woman as Mrs. Elton. -Emma

(There are several more quotations noting that Harriet is artless, from both Emma and Mr. Knightley)

Artless means without guile or deception, and it seems like Miss Tilney picks that up about Catherine right away. We readers of course know that Catherine is extremely honest, almost to a fault. Because not only does she shy away from lying, she also wants the truth to be known, which is why she is so quick to explain why she had to turn down Mr. Tilney for a dance. This will come up later...

This civility was duly returned; and they parted—on Miss Tilney’s side with some knowledge of her new acquaintance’s feelings, and on Catherine’s, without the smallest consciousness of having explained them.

Awww, Eleanor already knows that Catherine is crushing hard!

A great quote:

Woman is fine for her own satisfaction alone.

I love that Catherine's old aunt read her a lecture on how she shouldn't be vain about her clothes. It is funny though, Henry Tilney may be the rare type of man you could impress with a good muslin.

Catherine then tries very hard to avoid John Thorpe and hopes that Henry Tilney will again ask her to dance:

Every young lady may feel for my heroine in this critical moment, for every young lady has at some time or other known the same agitation. All have been, or at least all have believed themselves to be, in danger from the pursuit of someone whom they wished to avoid; and all have been anxious for the attentions of someone whom they wished to please.

Then when Henry does ask her, "With what sparkling eyes and ready motion she granted his request, and with how pleasing a flutter of heart she went with him to the set, may be easily imagined" It can be easily imagined! Catherine is just so cute and uncomplicated in her love.

John Thorpe is hilarious, having seen that he has lost Catherine for the dance, he tries to sell Henry Tilney a horse (!?!?). The man has way too many schemes to keep track of.

Now we get into the similarities between marriage and a country dance, wherein Catherine is largely lost but she ends up giving the right response in the end. We can see both the success of Catherine and the ultimate failure of Isabella described here:

You will allow, that in both, man has the advantage of choice, woman only the power of refusal; that in both, it is an engagement between man and woman, formed for the advantage of each; and that when once entered into, they belong exclusively to each other till the moment of its dissolution; that it is their duty, each to endeavour to give the other no cause for wishing that he or she had bestowed themselves elsewhere, and their best interest to keep their own imaginations from wandering towards the perfections of their neighbours, or fancying that they should have been better off with anyone else.

James will uphold this contract, but Isabella absolutely fails. She is the one seeking but not giving advantage, she is not exclusive, she gives James the wish of bestowing himself elsewhere, she lets her imagination wander and does fancy herself better off with someone else... How very predictive! Catherine, however, only has eyes for Mr. Tilney and she gives him, "a security worth having" by artlessly saying so.

Henry gets very close to mean here: “Only go and call on Mrs. Allen!” he repeated. “What a picture of intellectual poverty!" but I love how Catherine doesn't pick up on any hints to show herself in a good light. Henry is like, "Oh you spend your time more studiously in the country?" and she's all, "No, I'm generally looking for fun, I just can't find it." Isabella would be all over proving how rational she is in the country.

So many people ask what Henry sees in Catherine (people who tend to see Catherine as an idiot), but I think we do see her good qualities in this chapter. She's honest, she's loyal, and she's happy! "Not those who bring such fresh feelings of every sort to it as you do," Catherine doesn't try to be cooler than her surroundings, she just enjoys them. And her only wish is that her family was there to enjoy it with her too. How can you not love someone like that? Someone who loves and enjoys life is a joy to be around! "her spirits danced within her, as she danced in her chair all the way home."

We end with a planned country walk and Catherine being fairly excited to learn that Henry's family is all good-looking.

Also, the term "bloom" is talked about a lot with Anne Elliot in Persuasion. I haven't seen a lot of exact explanations of what that word means, but I think we can all agree, it isn't just a term for girls: "He was a very handsome man, of a commanding aspect, past the bloom, but not past the vigour of life." It's odd that people think it's a sexist term because even in Persuasion:

Sir Walter might be excused, therefore, in forgetting her age, or, at least, be deemed only half a fool, for thinking himself and Elizabeth as blooming as ever, amidst the wreck of the good looks of everybody else

I should do a full post about that someday. Mysterious word.

Wow, that was a long chapter, but so much good stuff going on. Glad the Tilneys are back because just having the Thorpes is misery.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

On April 1st 1295 Robert Bruce, “The Great Competitor” and grandfather of King Robert the Bruce, died.

With so many of the Bruce family called Robert there is a lot of confusion when talking about the family the explanation here will become apparent.

The family of Bruce originated from the town of Brus, modern Brix between Cherbourg and Valognes in Normandy and was founded by one particular Norman knight by the name of Robert who came across to England in the wake of the Norman conquest of 1066 and was granted some manors in Yorkshire by William I.

It has to be said that the Bruce family displayed a distinct lack of imagination in the naming of their sons. Having settled on the name Robert they stuck with it through thick and thin down the generations. Hence there are a succession of eight Robert Bruce’s over a period of three centuries and to make matters worse there are four generations of Roberts who each chose a wife named Isabel/Isabella.

You might think that this would be a source of confusion and you would be correct. More than one source gets hopelessly mixed up between Robert Bruce and another and it sometimes seems to be the case that no one is quite clear which Robert Bruce did what.

The second Robert of Bruce was notable for his friendship with David son of Malcolm III, king of Scots, who spent the early part of his life living in England as the Earl of Huntingdon, after his marriage with Matilda, daughter of Waltheof Siwardson and heiress to the estate of Huntingdon.

When David finally became David I, king of Scots, Robert was one of a number of Norman knights invited north to help David knit together the rather disparate group of territories that fell under his rule. Robert was granted the Lordship of Annandale, which was then within the territory of Strathclyde in what later became Dumfriesshire in the south western corner of Scotland.

Having said that nothing was ever black and white in those days and when King David fought the English at the Battle of the Standard in the year 1138 this Robert was on the English side. It was nothing personal but at this point The Bruce family owned land in what is now Yorkshire. To complicate things further by now there was a third Rober and you guessed it, the younger man was fighting on the Scottish side, this is what is known as hedging your bets! This third Robert subsequently lost control of the family land in Yorkshire.

The fourth Robert’s great contribution was to marry Isabel of Scotland the daughter of William the Lion, king of Scots. This was an indication of how important the Bruce family had became within the young kingdom of Scotland, but the marriage achieved an even greater significance in later years, as it was this connection with the Canmore dynasty that was to form the main basis of the claims by this Robert’s great-great-grandson to the throne of Scotland.

The fifth Robert married another Isabel, Isabel of Huntington who was the daughter of David, Earl of Huntington and Matilda of Chester. This David was the son of Henry of Huntington, son of David I of Scotland and Isabel was therefore niece of the aforementioned William the Lion; so yet another connection was made with the House of Canmore.

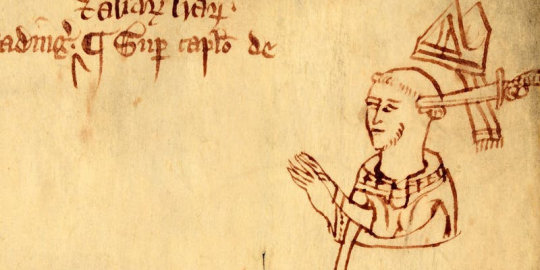

On to number six, I was going to make a joke about the Prisoner, but perhaps not! This is the Robert who died on this day in 1295. The sixth Robert continued the family tradition and married yet another Isabel, this time Isabel de Clare daughter of Gilbert de Clare and Lady Isabel Marshall which established a connection with the powerful Anglo-Norman de Clare and Marshall families.

This Robert was the first of his line to promote his claim as a candidate for the Scottish throne which became vacant following the death of Queen Margaret in 1290. He wasn’t successful on this occasion but it brought the Bruces right to the forefront of Scottish politics.

The seventh Robert married Marjorie of Carrick (the Countess of Carrick), and by right of his wife thereby obtained the title of Earl of Carrick.

Like his great-great-grandfather, he too fought on the English side against the Scots, this time at the battle of Dunbar in 1296. Although such is the confusion between the various Bruces, others suggest that it was not him but his son Robert the Bruce who did so, which would be doubly ironic.

And the most important one the most well-known is number eight Robert the Bruce who was the great champion of Scottish independence, who was crowned king of Scotland in 1306, defeated Edward II of England at the battle of Bannockburn in 1314, issued the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320, he died in 1329.

And there it ended, Robert broke the long line of Bruces named Robert and named his oldest son David, who became David II of Scotland.

There was another Robert Bruce though, but he was illegitimate to an unknown mother, Sir Robert Bruce, Lord of Liddesdale. He was killed leading a charge at the Battle of Dupplin Moor on 11 August 1332. during the second wars of Independence.

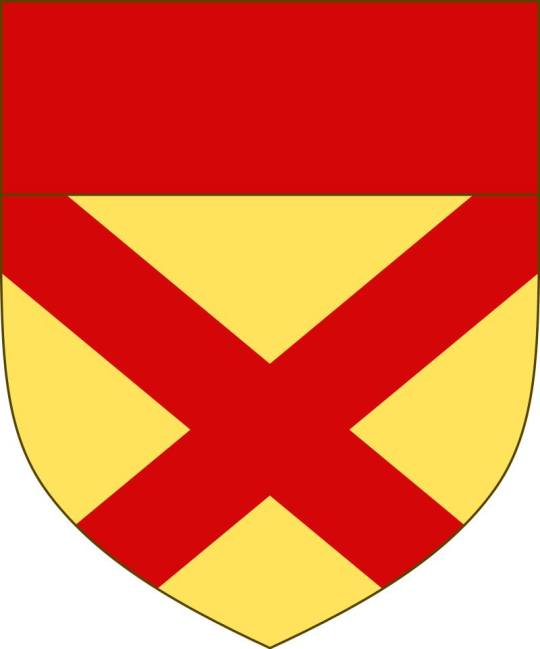

Pics are the linaege of the main three competitiors for the crown, the seal of the Robert of today’s post and the Bruce Coat of arms as Lord of Annandale: Or, a saltire and a chief Gules

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

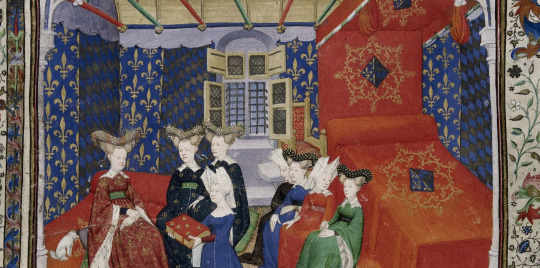

Educating the princesses

“All of these princesses, both foreign and French, had received a first-rate education. Some were raised at the French court from childhood, such as Philip IV’s wife Joan of Navarre and Charles VIII’s young fiancée Margaret of Austria. Others were educated within their own families in their respective principalities.

Educators had long debated what women should be taught. In 1265,

Philip of Novara had advised against teaching girls—except for nuns— how to read and write. He was, however, in the minority. Far from being neglected when it came to aristocratic education, women were the recipients of veritable miroirs aux princesses (didactic works presenting the exemplary image of the good ruler or, for women, the ideal princess), which reveal all the care that went into their training—as religious as it was moral and intellectual.

(...)

Beyond these theoretical treatises, sources on the practice of that time provide information about the educational methods of the period. Young princesses learned to read and often write. Such instruction often took place within the palace under a tutor. At the court of Savoy in the mid-fifteenth century, Pierre Aronchel was the schoolmaster of Louis and Anne of Cypress’s eldest daughters Margaret and Charlotte (future wife of Louis XI).

Like their brothers, young princesses first learned reading and religion. They learned to read using an alphabet book (Margaret of Austria learned the alphabet using a book handsomely bound in black velvet) and continued with psalters and books of hours. At the age of seven, young Joan of France, who was married to the Count of Montfort, received a richly illuminated book of hours of Notre-Dame from her mother Isabeau of Bavaria. During the fourteenth century, young girls at the court of Savoy practiced reading using liturgical collections, matins and penitential psalms, which were replaced by books of hours in the fifteenth century. Like their brothers, Savoyard princesses also learned to write.

Latin, however, was reserved for boys, which was one of the primary differences when it came to education. Princesses only knew the necessary prayers and formulas for following mass and reading their books of hours. There were a few exceptions nonetheless. Saint Louis’s sister Isabella of France (d. 1270), for example, was reputedly an excellent Latinist.

Failing Latin, aristocratic ladies knew other languages. John II’s future wife Bonne of Luxembourg, who had been raised in Bohemia, spoke Czech, German and French. Yolanda of Bar —daughter of Robert, Duke of Bar, and wife of John I, King of Aragon—could read ‘Limousin’ and Latin in addition to being able to write in French and Catalan. Others had a harder time learning a foreign language. During her entry ceremony in Paris in 1389, Isabeau of Bavaria was criticized for her poor understanding of French—four years after she had arrived in the kingdom.”

Queenship in medieval france 1300-1500, Murielle Gaude-Ferragu

#history#women in history#women's history#queens#middle ages#medieval women#france#french history#medieval history#isabeau of bavaria#Joan of navarre

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

5th June: A game of alphabets is played

Read the post and comment on WordPress

Read: Vol. 3, ch. 5 [41]; pp. 225–230 (“He had walked up one day” to “solitude of Donwell Abbey”).

Context

Frank makes a “blunder” regarding Mr. Perry’s carriage. Emma, Harriet, Mr. Knightley, the Randalls’ party, Miss Bates and Jane Fairfax play a game of alphabets at Hartfield. John and Isabella Knightley’s children have by this time ended their visit at Hartfield (Mr. Woodhouse “lament[s] […] over the departure of the ‘poor little boys,’” p. 227).

This occurs one “evening” (p. 225) soon after the beginning of “June” (vol. 3, ch. 5 [41]; p. 224).

A Pembroke is a small drop-leaf table commonly used for tea, dining, and writing in the Georgian period. On the “modern circular table” (p. 227), Duckworth writes: “A nice touch this, when one recalls the dubious significance that is attached both to Marianne Dashwood’s wish to give Allenham new furniture in Sense and Sensibility and to Mary Crawford’s wish to make Thornton Lacey a “modern” residence in Mansfield Park. Why a round table should merit comment is perhaps best indicated in Barchester Towers where Archdeacon Grantly says: “A round dinner-table ... is the most abominable article of furniture that ever was invented” (chap. 21). For Grantly there is “something peculiarly unorthodox” in the idea of a round table, “something democratic and parvenue” (FN 30, p. 172).

Note that this write-up contains spoilers.

Readings and Interpretations

Rank and Carriage

Frank Churchill, momentarily mistaking the source of his information, asks Mr. Weston about “‘Mr. Perry’s plan of setting up his carriage’” (p. 225). Robert Hume summarizes the economics of carriage-owning in late Georgian England thusly:

[John] Trusler opines that an income of £800 or more is necessary to support a carriage, expensive in itself and requiring horses, a coachman, fodder and stabling. The Adamses [Samuel and Sarah] say that the coachman will have to be paid 25–36 guineas per annum, plus two suits of livery and other garments (not to mention food and lodging) [appendix, p. 8]. In their view, an income of £1,000–£1,500 is the minimum on which keeping a carriage is economically sensible. (p. 56)

In this light, “Perry the apothecary presents a puzzle”:

The Cambridge editors [of the Cambridge edition of Emma] quote Irvine Loudon to the effect that a London GP might make £300–£400, a ‘provincial’ doctor £150–£200 (p. 373, n. 3). By implication, Perry is doing a lot better than even a London doctor, since he is considering ‘setting up his carriage’ (p. 373). This seems implausible. It might be a blunder, but Austen is not prone to such errors. Perhaps she is mocking Perry’s unrealistic pretensions. (ibid.)

John Wiltshire takes note of the health-related pretense for Mr. Perry’s ambition, arguing that it functions within the text to obscure these economic questions:

Mr Perry is […] a key reference in the distinctive sociolect of Highbury, a speech idiom which […] is much concerned with discussion of and enquiries about sickness and health. Highbury gossip interprets his purchase of the carriage, not as a sign of his prosperity, or of his social prestige, but in terms of his own ill health. ‘It was owing to [Mrs Perry’s] persuasion, as she thought his being out in bad weather did him a great deal of harm’ is Frank's recital of the gossip [p. 225]. Economic relations and social determinants are thus displaced or partially concealed by their redefinition as matters of health. […] Highbury remains oblivious to the political and social structures that are actually organising its world. […] All these inferences are tucked away in the midst of a narrative whose apparent enticement is to give a crucial clue about the romantic relation of Frank and Jane. Yet Mr Perry’s plural and eccentric position within the text helps at the same time to problematise the very questions of health and illness on which he is the deferred and obscured authority. (pp. 111–2)

Highbury’s Cassandra

After Frank attributes his question about Mr. Perry’s question to confusion resulting from a dream, Miss Bates at length manages to inform the company that such a plan did exist, though it was unknown to most. Regarding this incident, Joe Bray makes the familiar point that Miss Bates’s speech contains “hints” about the mysteries in Emma (p. 170):

The key clue here of course is not that Miss Bates herself had heard about the plan […]. Rather it is that someone else also knew: ‘“Jane, don’t you remember grandmamma’s telling us of it when we got home?”’ (375). Although Emma is ‘out of hearing’ […], Mr. Knightley has it seems heard enough to be suspicious, though his looking from Frank to Jane proves inconclusive.

[...] Miss Bates does not deserve to be dismissed as a caricature, a rambling speaker concerned simply with trivial local gossip. Her verbose, repetitive, often tedious speech conceals key clues as to the major secret in the novel, Frank and Jane’s attachment. A discerning reader who picks these up can stay one step ahead of the characters, even Mr. Knightley, who […] understands something of their relationship but does not see everything. Rather than knowledge being disseminated from a single, authoritative point of view then, the onus throughout Austen’s fiction is on the active role of the reader in piecing together an understanding of characters and relationships, just as the characters themselves are trying to do, in Emma’s case spectacularly unsuccessfully.

The way in which the reader is lured into such a dynamic engagement with the text in all of Austen’s novels casts further doubt then on the possibility of a dominant, totalizing perspective in her writing. Complete knowledge, or omniscience, on the reader’s as well as the narrator’s part, is not only impossible, but also not the point. Austen’s fiction repeatedly emphasizes instead the limitations of knowledge and the dangers, as well as the difficulties, of being certain about anything. There is no fullness of information to be attained as the reader reaches the conclusion of each of her works. Yet her style makes each journey endlessly rewarding. (p. 171)

When Miss Bates does speak, it is after “trying in vain to be heard the last two minutes” (p. 226). Her company’s unwillingness to attend to her may have as much to do with her speech patterns as with her situation, but Howard Babb argues that the two are not entirely separable:

Surely what in part motivates her to report so many facts and to speak so often of herself (even more than Jane does) is Miss Bates’s awareness that she and social authority have nothing at all to do with each other. In the following passage, we can see how quickly she backs up to “I” after her excitement has momentarily betrayed her into a decisive generalization: “if I must speak on this subject, there is no denying that Mr. Frank Churchill might have—I do not mean to say that he did not dream it—I am sure I have sometimes the oddest dreams in the world—but if I am questioned about it, I must acknowledge that there was such an idea last spring” [p. 226]. (p. 186)

In Your Dreams!

Some scholars comment on the resonance of Frank’s “dream” excuse with Emma’s textual concern with fantasy and imagination, noting the parallel drawn between Frank and Emma on this occasion. Per Laura Mooneyham, “[t]hat Frank’s ‘dream’ is but a cover for secrecy and deviousness reflects on Emma’s ‘dreaming’, her imaginative faculty, as well; in neither case is dreaming a morally neutral activity” (p. 122). There are, however, differences between how the two characters treat imagination: Colleen Sheehan writes that “[w]hile Frank dissembles and treats reality as a dream, Emma treats her dreams as reality. Her lively imagination is but a waking dream” (n.p.). Thus also Loraine Fletcher:

Frank’s dexterity as a plotter forms another comic parallel with Emma’s inventions. After his blunder in giving away his secret correspondence with somebody in Highbury […] he tries to attribute his knowledge to a dream. ‘I am a great dreamer’, he says, and the word recurs repeatedly in the next few paragraphs. Mr Weston associates dreamers with lovers when he rather coyly tries to advance the favourite Weston courtship fiction by suggesting that Frank and Emma dream of each other. But Frank is less of a dreamer than most people. His plots centre on keeping the heroine without losing the money, and he tells stories, but in the child’s sense of the phrase: he lies in every word he speaks. (p. 39)

A Game of Alphabets

The game of alphabets played in this chapter is a counterpart to Harriet’s riddle-book and Mr. Elton’s charade, and a preface to Mr. Weston’s conundrum on Box Hill; like Harriet’s portrait and Mr. Elton’s charade, the alphabets are physical objects that both invite and resist interpretation by different characters. Ashley Tauchert writes of the motif of games and interpretation in Emma:

Emma, when taken as a narrative message, is centred on a proliferation of encoded messages. Each message is both a material object—letter, word, instrument, ‘charade’, signifier—and its signification in a network of communication. The same thing can be said about the narrative text in which these messages appear. Harriet’s picture; Frank’s word games, imputed dream, and private correspondence; Jane’s mysterious pianoforte; Mr Elton’s charade—each concretise the narrative function of misdirection, misreception or misunderstanding of significant, but thoroughly ambigious, material. (p. 117)

Jillian Heydt-Stevenson similarly argues that Emma both includes and functions as a riddle or puzzle:

In Emma, the riddle works at the literal and metaphorical levels, helping constitute the novel’s larger meanings: people are charades, actual riddles appear and enigmatic situations emerge that we and the characters have to decipher. Why would Austen choose this brain-teasing genre for Emma? Perhaps because it provides a way to exercise one out of mental sluggishness and to examine the difficulty of knowing another. (p. 151)

It is typical to argue that such games in the novel represent some degree of childishness or an immoral befuddling of truth, taking Knightley’s disapprobation to be the narrator’s as well (see “The Charade”). Laura Mooneyham writes:

That this plot of Emma’s [the Jane / Dixon plot] is an immoral game is made clear when, under the watchful eye of Mr. Knightley, Emma and Frank play with the box of alphabets at Hartfield. […] The second set of letters is ‘Dixon’, which allows Emma and Frank to indulge themselves in sly laughter and which mortifies Jane. As Mr. Knightley, the distanced observer, perceives, ‘the letters were but the vehicle for gallantry and trick. It was a child’s play, chosen to conceal a deeper game on Frank Churchill’s part’ (p. 348). The letter game is yet another example of Emma’s abuse of language in her intrusions into the love affairs of others. (pp. 121–2)

Katrin Burlin builds on and complicates Alistair Duckworth’s understanding of games in Emma as “antisocial,” writing that it is how these games are played that upends standards of fair conduct, rather than the games per se:

[...] [A]s they are played in this novel, word games permit the player a greater degree of control than card games ruled by chance. As skill becomes a greater factor, ulterior ends threaten to rob play of its disinterestedness (Huizinga, p. 9). Detection of the element of false play is vital. Violating the rules of the anagrams game in their calculating play with “proper nouns” (like Emma in her matchmaking), Austen’s characters do play false. They manipulate the “alphabets” not to form and exchange mutually comprehensible words, but to communicate covertly, to break the circle of understanding. Pure play would actually support the “continuity of a public and ‘open’ syntax of morals and manners” Duckworth sees as vital to the preservation of culture (Duckworth, 1971, p. 165). For games are highly schematic, with fixed rules that demand general and absolute adherence. (p. 182)

Mr. Knightley is, of course, right to be suspicious of Frank’s motives: Frank “uses the game of alphabets to try to make Jane share his amusement at the near-miss” regarding Perry’s carriage (Selwyn, n.p.). His improperly played proper name DIXON is supposedly a covert dig at Jane that he participates in with Emma, but is in actuality a joke at Emma’s expense that he tries to engage in with Jane—who, either way, is mortified. Duckworth writes that “Churchill’s maneuvering is not only a quite voluntary danger to Jane’s reputation, but is also a cause of justifiable jealousy, as she sees Frank and Emma indulging in a kind of ‘courtship’ game” (p. 173).

The Unseen Seer, Redux

Conventional readings of Emma attribute some amount of prescience or omniscience to Mr. Knightley, taking him to be the proxy for the author in the text and holding that he represents the ability of the sober observer to neutrally discern reality. He arrives at the truth about Frank and Jane because he, unlike Emma the “imaginist,” is able to see them clearly. Paul Fry, for example, writes that Knightley’s “ease in guessing the truth about Frank Churchill and Jane Fairfax is nearly equal to his ease in unjumbling the letters of the [alphabet] game”; “Emma, on the other hand, […] is not clear-sighted” (p. 132). David Medalie similarly panegyrizes Knightley’s “unusual perspicacity” (p. 8) and “exceptional discernment” (p. 9), writing that “[w]here almost all are blind, he sees”; he has the “objectivity” required to “unlock the secret and recognise the situation for what it is” (ibid.).2

Other readings, however, emphasize Mr. Knightley’s fallibility as a character among other characters, and point out that his suspicions about Jane and Frank in fact do not lead him to knowledge of what the real situation is. Joe Bray notes that this forms one of the “occasions on which Mr. Knightley is an observer throughout the novel” and “his observations are represented to the reader” (p. 25):

Mr. Knightley’s position at the round table […] gives him a privileged perspective; able apparently to see all that is going on, yet without appearing to spy (‘with as little apparent observation’). […] He is right of course to connect the word ‘blunder’ with Frank’s previous claim that his hearing of Mr. Perry’s plan of setting up his carriage ‘“must have been a dream”’ […]. As he reaches towards an understanding of Frank and Jane’s ‘decided involvement’, […] Mr. Knightley’s thoughts enter into the narrative in FIT. Thus it is his judgement that, for example, ‘these letters were but the vehicle for gallantry and trick’ […]. One of the few occasions in the novel when someone’s perspective other than the heroine’s is represented, this passage, and this chapter as a whole, begins to make clearer to the reader the connection between Frank and Jane, as it is clear that the observant Mr. Knightley is on the verge of discovering the truth.

Yet of course Mr. Knightley does not quite see everything here. However the places are arranged at the table, the fact that it is explicitly designated as round means no one person has a total perspective. When Frank prepares another word for Emma, Mr. Knightley […] is unable to make out the word itself until Frank passes it, against Emma’s advice, to Jane. […] Jane’s reaction [to the word “Dixon”] is immediately apparent: ‘She was evidently displeased; looked up, and seeing herself watched, blushed more deeply than he had ever perceived her’ [p. 228]. As an angry Jane and Miss Bates get up to leave the table Mr. Knightley ‘thought he saw another collection of letters anxiously pushed towards her, and resolutely swept away by her unexamined’ [ibid.], but he cannot make this word out and it remains undisclosed (as Richard Cronin and Dorothy McMillan note, there is an Austen family tradition that the word was ‘pardon’ [2005, p. 587]). From a broader, figurative perspective too, although Mr. Knightley certainly sees that there is some understanding between Frank and Jane, he is far from working out what exactly the nature of this is, or what lies behind it: ‘how it could all be, was beyond his comprehension’. (pp. 26–7)

For Bray, Knightley’s lack of objective knowledge is reflected in the narrative style of this passage:

[...] FID [free indirect discourse] allows for the continued presence of the narrator’s perspective, which casts doubt in this instance of FIT [free indirect thought] on both the completeness and the reliability of Mr. Knightley’s. The reader is thus invited to question the severity of his judgement of Frank, and the contrasting vehemence with which Mr. Knightley defends Jane. ‘How the delicacy, the discretion of his favourite could have been so lain asleep!’ introduces a potential tone of mock-heroism which may at the very least give the reader pause. The strident condemnation of ‘These letters were but the vehicle for gallantry and trick. […]’ is also at least slightly undercut by the continued narratorial perspective, as well as by the fact that earlier in the chapter it has been revealed that ‘Mr. Knightley, who, for some reason best known to himself, had certainly taken an early dislike to Frank Churchill, was only growing to dislike him more’ [p. 224]. Mr. Knightley certainly sees more than Emma as regards Frank and Jane […]. However his perception is not absolute, and is clearly biased by his dislike of Frank. He suspects the younger man of ‘some inclination to trifle with Jane Fairfax’ [ibid.] which is not entirely wrong, but still comes some way short of a full understanding of the relationship between them. For all his eagerness to observe, and his frequently being placed in a good position to do so, Mr. Knightley remains just another observer around the round table of Highbury society, whose perspective may be more accurate than that of others but is nevertheless in important ways not definitive. (pp. 27)

Mary Waldron also points out that Knightley in fact does not arrive at the “truth” of the relationship between Frank and Jane, and suspects only that some sort of “double-dealing” is taking place. She notes that, at this time, he does not know that Emma is not interested in Frank, which “misunderstanding renders Mr. Knightley both vulnerable and powerless”:

[H]e has to stand silently by while he watches (as he thinks) the girl he now loves give herself up to a shallow and insensitive man, in whom he shortly discovers evidence of even worse qualities. His attempts to warn her of Frank’s relationship with Jane fail, for, as the reader knows, they talk at cross-purposes. It is a mistake to conclude that Mr. Knightley here reaches the truth about Jane and Frank. The text makes clear that he is alarmed but mystified. He is quite oblivious to Emma’s regrettable fantasy about Jane and Mr. Dixon. Still convinced that Frank will marry Emma (after all, she has the money […]), Mr. Knightley believes that he is somehow manipulating both girls and that Emma’s chances of a happy and stable marriage are doomed. He speaks out of a sense of real concern at what he sees as her danger and is saddened to find that Emma remains in her usual relation to him; she flouts his warning as ridiculous, hinting at confidentiality between herself and Frank. Mr. Knightley naturally feels defeated […]. Their behavior toward each other, though their relationship is subtly changing, takes its usual form of attack and repulse. But this time the situation, at least for Mr. Knightley, is far more serious than their feud about Harriet Smith. His conviction that Emma will become the victim of such hollow flattery as Frank hands out is almost as perverse as Emma’s current chimera—that Frank will marry Harriet […]. (p. 153)3

Regardless of what Mr. Knightley is able to suspect at this point in the text, David Selwyn argues that the reader ought to be able to understand more:

Mr. Knightley connects the word [“blunder”], and the blush it produces in Jane, with the dream, but he cannot work it out. The reader ought to be able to, however, for it is the same word that Jane used of the post office [vol. 2, ch. 16; p. 193]. We should thus recall the importance to her of letters and realize that that is how Frank came to know of Mr. Perry’s carriage. It is only on a second reading that we are likely to be aware of this […]. But having noticed it and having understood not only that nobody there could make the connection, but that Jane Austen does not intend them to, we begin to see what she is doing: that the clue is entirely for our benefit and that once we have seen it we are made complicit in a game that she is playing directly with us, over and beyond her characters. And from that point we ought to be on the watch for further moves against us. (n.p.)

Footnotes

See also Merrett, p. 734.

On this scene see also Duckworth (p. 174).

See also Royle on how the word “blunder” “recurs at various moments involving the materiality of writing” (p. 52).

Discussion Questions

Why did Mr. Perry form and, to an extent, share, a plan to set up a carriage? Why would his wife attribute the plan to a concern for his health?

What is the motive behind the words that Frank constructs during the game of alphabets? Is he trying to apologize to Jane, share amusement with her, or taunt her? How is Jane feeling throughout this section?

Has Knightley discovered the truth about Jane and Frank? If so, how?

Bibliography

Adams, Samuel, and Sarah Adams. The Complete Servant. London: Knight and Lacey (1825).

Austen, Jane. Emma (Norton Critical Edition). 3rd ed. Ed. Stephen M. Parrish. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, [1815] 2000.

_____. Emma. Ed. Richard Cronin & Dorothy McMillan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, [1815] 2005.

Babb, Howard S. “Emma: Fluent Irony and the Pains of Self-Discovery.” In Jane Austen’s Novels: The Fabric of Dialogue. Columbus: Ohio State University Press (1962), pp. 175–202.

Bray, Joe. The Language of Jane Austen. London: Palgrave Macmillan (2018).

Burlin, Katrin Ristkok. “Games.” In Grey et al., ed. (1986), pp. 179–83.

Duckworth, Alistair M. “Emma and the Dangers of Individualism.” In The Improvement of the Estate: A Study of Jane Austen’s Novels. Baltimore, ML: John Hopkins Press, 1971, pp. 145–78.

Fry, Paul H. “Georgic Comedy: The Fictive Territory of Jane Austen’s Emma.” Studies in the Novel 11.2 (Summer 1979), pp. 129–46.

Heydt-Stevenson, Jillian. “Games, Riddles and Charades.” In The Cambridge Companion to Emma, ed. Peter Sabor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2015), pp. 150–65. DOI: 10.1017/CBO9781316014226.013.

Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-element in Culture. Boston: The Beacon Press (1955).

Hume, Robert D. “Money and Rank.” In Sabor, ed. (2015), pp. 52–67.

Medalie, David. “‘Myself Creating What I Saw’: Sympathy and Solipsism in Jane Austen’s Emma.” English Studies in Africa 56.2 (2013), pp. 1–13. DOI: 10.1080/00138398.2015.856553.

Merrett, Robert James. “The Gentleman Farmer in Emma: Agrarian Writing and Jane Austen’s Cultural Idealism.” University of Toronto Quarterly 77.2 (Spring 2008), pp. 711–37.

Royle, Nicholas. “Telepathy: From Jane Austen and Henry James.” Oxford Literary Review 10.1/2 (1988), pp. 43–60.

Selwyn, David. “Games and Play in Jane Austen’s Literary Structures.” Persuasions 23 (2001), pp. 15–28.

Sheehan, Colleen A. “The Riddles of Emma.” Persuasions 22 (2000), pp. 50–61.

Tauchert, Ashley. “Emma: ‘The Operation of the Same System in Another Way.’” In Romancing Jane Austen: Narrative, Realism, and the Possibility of a Happy Ending. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan (2005).

Trusler, John. The Way to be Rich and Respectable. 7th ed. London: John Trusler (1796).

_____. Trusler’s Domestic Management. London: J. Souter (1819).

Waldron, Mary. “Men of Sense and Silly Wives: The Confusions of Mr. Knightley.” Studies in the Novel 28.2 (Summer 1996), pp. 141–57. Repr. in Jane Austen and the Fiction of her Time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1999), pp. 112–34. DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511484667.006.

Wiltshire, John. “Emma: The Picture of Health.” In Jane Austen and the Body. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1992), pp. 110–54. DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511586248.005.

#Jane Austen#Emma#Emma Woodhouse#Mr. Knightley#Mr. Weston#Mrs. Weston#Jane Fairfax#Miss Bates#Frank Churchill#Harriet Smith#e

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Virtual Sketchbook #3

The Triumph of Divine Love by Peter Paul Rubens, 1625. Accessed 03/26/2024 https://ringlingdocents.org/divine.htm.

Describe Visual Qualities:

The Triumph of Divine Love by Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens is a oil on canvas painting. The massive size is very eye-catching with a height of 17ft (518.2cm) and width of 12.6ft (386.1 cm). At first glance the painting consists of cheery and bright colors that create a joyful feeling. The main subject is Charity at the center, holding one of her children, highlighted with the lightest part of the painting. Two more of her children stand next to her as they ride a chariot pulled by two lions, which show contrasting shadows at the bottom of the piece. The borders also show contrasting shadows that work to pull viewers’ attention towards the center. The artwork possesses a variety of subjects such as Charity (who resembles Mother Mary), twelve putti flying in the air (winged children, Cupids), three more grounded putti one of whom is riding a lion holding an arrow, two lions, a pelican piercing its own breast to feed its young, and two intertwined snakes. The varying subjects do not create a chaotic effect, instead a sense of unity is felt through the placement of light and dark areas as well as the central focal point.

How does work make you feel:

During my visit to the Ringling Museum of Art, The Triumph of Divine Love piqued my interest the most. Its size and complexity first caught my attention. I’ll admit I am not the biggest fan of old religious art pieces, but the beauty of this painting cannot be denied. The central focal point of the female figure cradling her baby with a look of fondness and joy reminded of my maternal feelings of love for my own baby. Viewing the piece inspires feelings of happiness and contentment. I also felt a sense of happiness while viewing the work.

The upbeat tone versus other more graphic sad scene of most paintings of this era is what made me admire it.

Research:

Peter Paul Rubens created The Triumph of Divine Love in the 17th century. Rubens was one of the most well-known Baroque artists of that time. Rubens was commissioned by Archduchess Isabella, “to design the 20 cartoons for the tapestry series of the Triumph of the Eucharist for the convent of the Descalzas Reales in Madrid” (Vlieghe).

The Triumph of Divine Love was one of this series. As a devote Catholic, Ruben incorporated allegory of religious event into many of his works. “Europeans had so linked the body of Christ with the body social and political that the Eucharist became "the emblematic focus of the struggle" between Catholics and Protestants…” (Harrie). In the Eucharist cycle, the artist focused on portraying victory of good over evil. Specifically in The Triumph of Divine Love, Rubenscreates a scene of celebration after, “the defeat of evil in the world by religious or divine love” (Anderson).

Personal Critique:

After my research I view Ruben The Triumph of Divine Love in a much different way. The symbolism shown throughout tells a story of, as the title refers, triumph. The putti are a way to show profane love. The snakes intertwined at the bottom represent evil with the flaming heart above as the “Sacred Heart” referring to Jesus’s love for humanity. The positioning of these symbols infers the defeat of evil with faith. Prior to this project, I lacked knowledge to identify the meaning behind the subjects. The painting is a clear representation of the cultural ideals of that time, and I have learned a great deal from looking into the purpose of its creation. The skill needed to execute this timeless piece of art shows the mastery Rubens possessed and why he was one of the best artists of the 17th century. I can only imagine the effect of seeing all of Rubens’ Eucharist series together.

Selfie of my in the beautiful Ringling Courtyard.

Cites Sources:

Anderson, Robert. The Triumph of Divine Love, 2000, accessed 29 March 2024, https://ringlingdocents.org/divine.htm.

Harris Jeanne. Discussion of Léonard Limosin's enamel Triumph of the Eucharist and of the Catholic Faith, Sixteenth Century Journal; Spring2006, Vol. 37 Issue 1, p43-57, 15p, accessed 29 March 2024, https://web.p.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=5&sid=657838c2-4aef-4ee5-9605-b9bffb78a770%40redis&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPXNoaWImc2l0ZT1laG9zdC1saXZl#AN=509859203&db=hus.

Vlieghe, Hans. "Rubens, Peter Paul." Grove Art Online. 2003. Oxford University Press. Date of access 29 Mar. 2024, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/display/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000074324?rskey=4WqXlf&result=1.

1 note

·

View note

Text

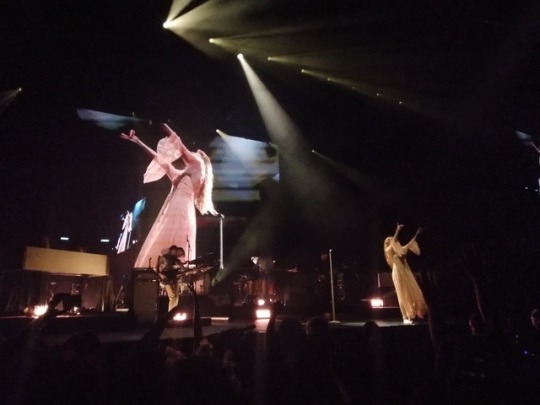

Some photos I took last night from their concert in Mexico City ✨

#florence and the machine#florence + the machine#florence welch#florence & the machine#f+tm source#florence#how big how blue how beautiful#isa machine#isabella summers#fatm#rob ackroyd#ceremonials#lungs#isamachine#f+tm#tom moth#between two lungs#hbhbhb#robert ackroyd#delilah#ship to wreck#fatm source#isabella machine#queen of peace#what kind of man#live#mexico#mexico city#palacio de los deportes#sport palace

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theatre review: Starry cast of Endgame includes Robert Sheehan and Frankie Boyle

As this production at the Gate underlines, Beckett's work has felt all the more pertinent in the pandemic

Source: The Irish Examiner (X)

Quoted: “Robert Sheehan’s Clov is another highlight, reminding us of his past incarnation of the Playboy, finding the echoes of Synge that were always there in Beckett’s text, while also nodding towards the worlds of Enda Walsh and Martin McDonagh.”

That scenario raises the fundamental Beckettian question: why go on? If in Waiting for Godot it was because something, an arrival, might happen (though of course it doesn’t), in Endgame it’s because, well, something might stop happening. We might get some release, some definitive, meaningful closure.

That scenario raises the fundamental Beckettian question: why go on? If in Waiting for Godot it was because something, an arrival, might happen (though of course it doesn’t), in Endgame it’s because, well, something might stop happening. We might get some release, some definitive, meaningful closure.

Yeah right. Closure, of course, is asking too much. This is Beckett after all. But Danya Taymor’s production does offer release. It’s palpable on opening night: a first full house in years is determined to have fun, determined to laugh at the jokes, quips and asides, many of them poking fun at the very idea of theatre, the very idea that we would watch this stuff. And that raises an odd question: is an Endgame this enjoyable, this, well, fun, a betrayal in some way of the text?

This strange feeling is not helped by Frankie Boyle’s Hamm. He’s a sardonic so-and-so, but under it all a bit of a softie, too. He’s not the monstrous Hamm one is accustomed to, the irascible egotist who exerts such a gravitational pull on the others in this little world. And without that threat of anger, that mood of resentment, the play loses something. It becomes too easily digestible, a bit too knockabout for its own good.

A brilliant turn from Sean McGinley as Nagg (alongside, in the dustbins, Gina Moxley’s Nell) reminds us of what’s missing. His long speech to Hamm is a wake-up call almost, suddenly touching the true bleakness of the text.

Robert Sheehan’s Clov is another highlight, reminding us of his past incarnation of the Playboy, finding the echoes of Synge that were always there in Beckett’s text, while also nodding towards the worlds of Enda Walsh and Martin McDonagh. The design is strong, too, with Isabella Byrd’s subtle, shifting lighting, and Sabine Dargent’s set.

There is, then, much to enjoy in this production, which Taymor never lets flag. And to sit and wrestle with why some of this might be problematic makes for an engrossing night of theatre.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

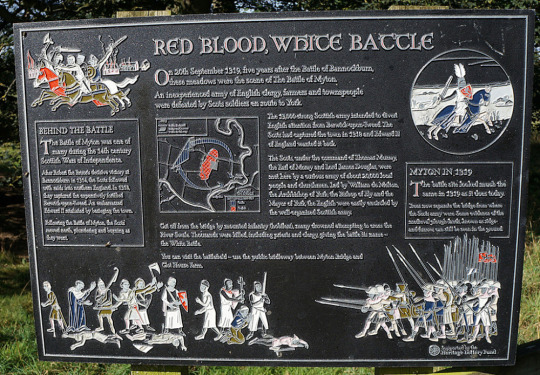

The Battle of Myton - Veteran Scots vs English Priests

The year was 1319, and Scotland’s Wars of Independence were going well for the northern kingdom. A famous victory over the English at Bannockburn five years earlier had cemented the rule of Robert I (Robert the Bruce) and left England on the brink of civil war.

In 1318 the Scots reinforced their success by capturing the vital border town of Berwick. After five years of raids into the north of England, the fall of the heavily fortified town spurred Edward II and his barons into retaliatory action. Along with his queen, Isabella, he mustered the host and marched north, laying siege to Berwick while the queen remained in York.

Despite investing Berwick by land and sea, the Scots resisted, led by Walter Stewart, the High Steward of Scotland. King Robert wished to lift the siege, but knew that engaging Edward’s larger army in a pitched battle would be unwise. Consequently, he dispatched a raiding force led by his foremost lieutenant, the Black Douglas, into Yorkshire, hoping to draw Edward’s attention away from Berwick.

The Scots seemingly had news of the queen's whereabouts, and the rumour soon spread that one of the aims of their raid was to take her captive. As they advanced towards York, she was hurriedly taken out of the city by water, finally gaining refuge further south in Nottingham. Yorkshire itself was virtually undefended and the raiders had an uninterrupted passage from place to place. William Melton, the Archbishop of York, set about mustering an army, which included a large number of men in holy orders. While the force was led by some men of standing, including John Hotham, Chancellor of England, and Nicholas Fleming, Mayor of York, it had very few men-at-arms or professional fighting men.[5] From the gates of York, Melton's host marched out to face the battle-hardened schiltrons, some 3 miles (5 km) east of Boroughbridge, where the rivers Swale and Ure meet at Myton. The outcome is described in the Brut or the Chronicles of England, the fullest contemporary source for the battle;

The Scots went over the water of Solway...and come into England, and robbed and destroyed all they might and spared no manner of thing until they come to York. And when the Englishmen at last heard of this thing, all that might travel-as well as monks and priests and friars and canons and seculars-come and meet with the Scots at Myton-on-Swale, the 12th day of October. Alas! What sorrow for the English husbandmen that knew nothing of war, they were quelled and drenched in the River Swale. And their holinesses, Sir William Melton, Archbishop of York, and the Abbot of Selby and their steeds, fled, and come to York. And that was their own folly that they had mischance, for they passed the water of Swale; and the Scots set fire to three stacks of hay; and the smoke of the fire was so huge that the Englishmen might not see the Scots. And when the Englishmen were gone over the water, so come the Scots with their wings in manner of a shield, and come toward the Englishmen in a rush; and the Englishmen fled, for they lacked any men of arms...and the Scots hobelars went between the bridge and the Englishmen. And when the great host had them met, the Englishmen almost all were slain. And he that might wend over the water was saved; but many were drenched. Alas, for sorrow! for there was slain many men of religion, and seculars, and also priests and clerks; and with much sorrow the Archbishop escaped; and therefore the Scots called it 'the White Battle'...

Many men were pressed into service who were not trained soldiers, including those who were monks and choristers from the cathedral in York. As so many clerics were slain in the encounter, it also became known as the 'Chapter of Myton'. Barbour gives the English loss as 1,000 killed, including 300 priests, but the contemporary English Lanercost Chronicle says that 4,000 Englishmen were killed by the Scots, while another 1,000 were drowned in the River Swale. Nicholas Fleming was among those killed.

The Chapter of Myton had the effect that Bruce was looking for. At Berwick it caused a serious split in the army between those like the king and the southerners, who wished to continue the siege, and those like Lancaster and the northerners, who were anxious about their homes and property. Edward's army effectively split apart: Lancaster refused to remain and the siege had to be abandoned.

The campaign had been another fiasco, leaving England more divided than ever. It was widely rumoured that Lancaster was guilty of treason, as the raiders appeared to exempt his lands from destruction. Hugh Despenser, the king's new favourite, even alleged that it was Lancaster who had told the Scots of the queen's presence in York. To make matters worse, no sooner had the royal army disbanded than Douglas came back over the border and carried out a destructive raid into Cumberland and Westmorland. Edward had little choice but to ask Robert for a truce, which was granted shortly before Christmas.

#myton#battle of myton#scotland#scottish#scottish history#medieval#middle ages#medieval history#14th century

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twilight (2008)

Twilight is not the 0-star picture so many people claim (or want) it to be. If you like it, I can understand why. That said, those who call it a great film are doing so because of their affection for the source material, which itself isn't particularly robust. This is getting overly complicated. Let’s just get to the review.

Seventeen-year-old Isabella “Bella” Swan (Kristen Stewart) moves to the small town of Forks to live with her father, Charlie (Billy Burke). At her new school, she gets along with everyone… except for the enigmatic Edward Cullen (Robert Pattinson). The boy seems almost repulsed by her but Bella is drawn to him. As it turns out, he - and his feelings for Bella - aren't what they seem.

There are some undeniable faults in this picture. The performances, for instance. Robert Pattinson and Kristen Stewart have proven themselves strong performances but director Catherine Hardwicke stifles any emotions that might've been present. Not helping is the screenplay by Melissa Rosenberg, which directly quotes the novel by Stephenie Meyer often. You'll find plenty of clunky, overly wordy exchanges, the kind that comes from an author spinning their wheels, trying to buy time before a big reveal three chapters later by busting out their thesaurus and endlessly re-writing the same dialogue until it becomes a garbled mess.

Twilight is also a bit too ambitious for its budget. The special effects aren't convincing. It made me think back to the Smallville pilot, which would've been a good thing was this a TV series or non-theatrical movie, but someone should’ve looked at the fast-motion effects and recognized how silly they looked.

If you’re reading this segment of the review, you know that Edward is a vampire. Not the scary Nosferatu type, but a hundred-year-old glittering, sullen-faced, creature of the night that falls head-over-heels in love with Bella Swan. People will call this ridiculous but this is where I'll defend Twilight. Yes, the glittering thing is dumb, but it’s a detail. Considering every vampire in this film has a different superpower (which is an elegant way of blending the various myths about vampires), you can just pretend that’s Edward’s. I will also stand up for the relationship between the lovers. Bella and Edward have something about them that genuinely WOULD make them a good couple. When Bella comes to school, she’s basically loved by all. The boys want to date her, the girls want to be her best friend. All, except for one guy. Why? because Edward can read minds. No one in the world is a mystery to him. Holding a conversation, even with his fellow vampires is redundant but he can’t hear Bella’s thoughts. She's the only person in the entire world he could sit down and have a chat with.

There’s a germ of a good idea here. It’s the execution that's at fault. Perhaps the source material too. You might have to squint a bit but you can find scenes in the film that are good. The best example is a moment when the Cullens play baseball. It shows them as real “human beings”. People will call the scene where Edward admits that he likes to watch Bella sleep “creepy”, but that’s because he can't express himself well. As a vampire, he doesn’t sleep. He's been forced to live only with his kind and always drifts further away from normal human behavior. He hasn’t seen someone sleep in ages. He’s not “keeping an eye on her” at all times, he’s fascinated by every aspect of this young woman. Many of the interactions Bella has with her friends are charming and Billy Burke does good work with his role.

Twilight is harmless. It will appeal to those who've enjoyed the book and is sure to ensorcell young teenage girls. Unfortunately, the source material's weaknesses shine through, and neither director Catherine Hardwicke nor writer Melissa Rosenberg do much to improve upon it (trust me on that). This makes it nothing special for the rest of us but hardly a plague upon cinema so many people have declared it to be. I don’t see why it’s gotten such strong reactions either way. Perhaps the sequel, New Moon, will make it clearer. (Theatrical cut on DVD, December 9, 2016)

#Twilight#Movies#films#MovieReviews#FilmReviews#MelissaRosenberg#StephenieMeyer#KristenStewart#RobertPattinson#BillyBurtke#PeterFacinelli#2008movie#2008films

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram story: Aug 10, 2023

#cats korea tour 2022#cats taiwan extension 2023#source: isabella roberts#source: saverio pescucci#isabella roberts#victoria (cats)#victoria the white cat#gabrielle parker#jemima (cats)#saverio pescucci#alonzo (cats)#meghan peploe williams#cassandra (cats)#backstage cats#please stop counting down shows you make me sad#closing cats countdowns skip the queue because i'm sad

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The second prince of Windenburg is rumored to be dating a new woman. I must remind you all readers that the prince has had flings but never serious romances, specially not of the kind that makes many of my sources say that he is thinking about proposing.

To same sources claim that the prince is so serious about his relationship with this new lady that he already introduced her to his parents and his siblings.

We were able to capture the lady in question at her workplace. She is a med student that is allegedly at the top of her class and on her way to a fellowship.

She works at the Golden Oak Community Hospital located in Northern Windenburg. We think this is one of the reason’s Prince Albert flew earlier than the rest of his family.

Things get a little messy after we found out the lady’s name. She is the eldest daughter of Lord Robert and Lady Isabella Haven, Baron and Baroness of Oak. Who let me remind you all are the former best friend and former girlfriend of the king. Back in the day their wedding caused a big scandal as it was reported they married a few days after king Edward and lady Isabella broke up.

Apparently the story is in the past and they have found peace as their children are now dating. Or maybe they don’t know. We will make sure to find out, so stay around dear readers.

Beginning//Previous//Next

#ts4 royal legacy#ts4 royal family#ts4 royalty simblr#ts4 simblr#ts4 royal#the sims 4#the sims 4 royal simblr#the sims 4 royalty#the sims 4 royal legacy#the sims 4 royal family#the sims 4 simblr#simblr#royal simblr#Sim: Albert#Sim: Anne#TRHOW#TRHOWgossipmagazine

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Repost @batman.bvs ・・・ Exciting news about casting for this lovely character We have four beautiful women to play #batgirl 🔥😍 Which one will be is the biggest question. Can’t wait 🤩 ‘Batgirl’: Talent Lines Up To Test For Barbara Gordon Role Even though audiences won’t see Robert Pattinson in The Batman for another eight months, Warner Bros. and DC Films are putting the wheels in motion on its next big superhero. Sources tell Deadline execs are expecting to test a group of actresses starting this week for the highly coveted title role of Batgirl. Although test deals still are being locked up and some already have passed, the talent expected to test for the role includes Isabella Merced, Zoey Deutch and Leslie Grace. We also have heard Haley Lu Richardson’s name, but she might have bowed out before the test process. The film will bow on HBO Max, marking one of the first major DC properties to bow exclusively on the streamer. Adil El Arbi and Bilall Fallah will direct the pic from a script by Christina Hodson. Kristin Burr is producing. While plot details are under wraps, it is known that Barbara Gordon, the daughter of Commissioner Gordon, will be the character behind the cape in this version. Source: - @deadline #batgirl #dccomics #thebatman #batman #batfleck #benaffleck #robertpattinson #warnerbros #snyderverse #arkham #zacksnyder https://www.instagram.com/p/CRjj83VHYHF/?utm_medium=tumblr

#repost#batgirl#dccomics#thebatman#batman#batfleck#benaffleck#robertpattinson#warnerbros#snyderverse#arkham#zacksnyder

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 9th 1327 saw the death of Walter Stewart, 6th High Steward of Scotland.

You might not have heard of Walter but with the birth of his son Robert the line of Kings and Queens of the Stewarts began, hence this is another kinda long post.

Walter was born at Bathgate Castle, West Lothian, Scotland, the eldest son and heir of James Stewart, 5th High Steward of Scotland by his third wife Giles de Burgh, a daughter of the Irish nobleman Walter de Burgh, 1st Earl of Ulster. This meant he later ended uprelated to King Robert through his second wife Elizabeth de Burgh

At the age of 21 Walter fought against the English at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 (based on his suspected birth year of 1296, he would have been only 18 at Bannockburn, so there is something not right there, either the birth year or the age he was at the battle).

Sir Walter the Steward and his cousin James Douglas were knighted on the eve of the Battle of Bannockburn. The Steward had nominal command of a brigade, although, since he was a mere youth, James Douglas was the actual commander, although some sources say he had a major role as a commander, I tend to go with him being taken under the wing of the Good Sir James.

For his services at Bannockburn, Walter was appointed Warden of the Western Marches and was rewarded with a grant of the lands of Largs, which had been forfeited by King John Balliol. In 1316 Stewart donated those lands to Paisley Abbey. Following the liberation of King Robert the Bruce's wife, Elizabeth de Burgh, and daughter, Marjorie, from their long captivity in England in October 1314, Walter the High Steward was sent to receive them at the Anglo-Scottish Border and conduct them back to the Scottish royal court. Soon after, in 1315, he married Marjorie. Who died giving birth to their only son.

Marjorie Bruce's death would be the second death of this nature in their line - her mother Isabella of Mar died giving birth to Marjorie, or shortly after - one child, one death of the mother. Marjorie is said to have died after a fall from horseback, which sent her into labour, in the end dying from childbirth, but it is also said she lived for a few months after the birth, but the truth is lost to time. This would seem to make their son Robert II have as many babies as he could, and he had many, but we will get to him.

During the absence of King Robert the Bruce in Ireland, Walter the High Steward and Sir James Douglas managed government affairs and spent much time defending the Scottish Borders. Upon the capture of Berwick-upon-Tweed from the English in 1318 he took command of the town which subsequently on 24 July 1319 was besieged by King Edward II of England. Several of the siege engines were destroyed by the Scots' garrison whereupon Walter the Steward suddenly rushed in force from the walled town to drive off the enemy. In 1322, with Douglas and Thomas Randolph, he made an attempt to surprise the English king at Byland Abbey, near Malton in Yorkshire, but Edward escaped, pursued towards York by Walter the Steward and 500 horsemen.

He married Isabel de Graham, believed to have been a daughter of Sir John Graham of Abercorn, by whom he had three further children: John Stewart of Ralston. Sir Andrew Stewart, knight. Egidia Stewart, who married three times: firstly to Sir James Lindsay of Crawford Castle; secondly to Sir Hugh Eglinton; and thirdly to Sir James Douglas of Dalkeith.

It's recorded he died after falling ill with a feveron this day 1326 at Bathgate, he was only 30, but was already a much admired warrior of the era.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

2nd January 1264: Marriage and Murder in Mediaeval Menteith

(Priory of Inchmahome, founded on one of the islands of Lake of Menteith in the thirteenth century)

On 2nd January 1264, Pope Urban IV despatched a letter to the bishops of St Andrews and Aberdeen, and the Abbot of Dunfermline, commanding them to enquire into a succession dispute in the earldom of Menteith. Situated in the heart of Scotland, this earldom stretched from the graceful mountains and glens of the Trossachs, to the boggy carseland west of Stirling and the low-lying Vale of Menteith between Callander and Dunblane. The earls and countesses of Menteith were members of the highest rank of the nobility, ruling the area from strongholds such as Doune Castle, Inch Talla, and Kilbryde. Perhaps the best-known relic of the mediaeval earldom is the beautiful, ruined Priory of Inchmahome, which was established on an island in Lake of Menteith by Earl Walter Comyn in 1238. Walter Comyn was a powerful, if controversial, figure during the reigns of Kings Alexander II and Alexander III. He controlled the earldom for several decades after his marriage to its Countess, Isabella of Menteith, but following Walter’s death in 1258 his widow was beset on all sides by powerful enemies. These enemies even went so far as to capture Isabella and accuse her of poisoning her husband. The story of this unfortunate countess offers a rare glimpse into the position of great heiresses in High Mediaeval Scotland, revealing the darker side of thirteenth century politics.

Alexander II and Alexander III are generally remembered as powerful monarchs who oversaw the expansion and consolidation of the Scottish realm. During their reigns, dynastic rivals like the MacWilliams were crushed, regions such as Galloway and the Western Isles formally acknowledged Scottish overlordship, and the Scottish Crown held its own in diplomacy and disputes with neighbouring rulers in Norway and England. Both kings furthered their aims by promoting powerful nobles in strategic areas, but it was also vital to harness the ambition and aggression of these men productively. In the absence of an adult monarch, unchecked magnate rivalry risked destabilising the realm, as in the years between 1249 and 1262, when Alexander III was underage.

(A fifteenth century depiction of the coronation of Alexander III. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Walter Comyn offers a typical picture of the ambitious Scottish magnate. Ultimately loyal to the Crown, his family loyalties and personal aims nonetheless made him a divisive figure. A member of the powerful Comyn kindred, he had received the lordship of Badenoch in the Central Highlands by 1229, probably because of his family’s opposition to the MacWilliams. In early 1231, he was granted the hand of a rich heiress, Isabella of Menteith. In the end, there would be no Comyn dynasty in Menteith: Walter and Isabella had a son named Henry, mentioned in a charter c.1250, but he likely predeceased his father. Nevertheless, Walter Comyn carved out a career at the centre of Scottish politics and besides witnessing many royal charters, he acted as the king’s lieutenant in Galloway in 1235 and became embroiled in the scandalous Bisset affair of 1242.

When Alexander II died in 1249, Walter and the other Comyns sought power during the minority of the boy king Alexander III. They were opposed by the similarly ambitious Alan Durward and in time Henry III of England, the attentive father of Alexander III’s wife Margaret, was also dragged into the squabble as both sides solicited his support in order to undermine their opponents. Possession of the young king’s person offered a swift route to power, and, although nobody challenged Alexander III’s right to the throne, some took drastic measures to seize control of government. Walter Comyn and his allies managed this twice, the second time by kidnapping the young king at Kinross in 1257. They were later forced to make concessions to enemies like Durward but, with Henry III increasingly distracted by the deteriorating political situation in England, the Comyns held onto power for the rest of the minority. However Walter only enjoyed his victory for a short while: by the end of 1258, the Earl of Menteith was dead.

Walter Comyn had dominated Scottish politics for a decade, and even if, as Michael Brown suggests, his death gave the political community some breathing space, this also left Menteith without a lord. As a widow, Countess Isabella theoretically gained more personal freedom, but mediaeval realpolitik was not always consistent with legal ideals. In thirteenth century Scotland, the increased wealth of widows made them vulnerable in new ways (not least to abduction) and, although primogeniture and the indivisibility of earldoms were promoted, in reality these ideals were often subordinated to the Crown’s need to reward its supporters. Isabella of Menteith was soon to find that her position had become very precarious.

At first, things went well. Although one source claims that many noblemen sought her hand, Isabella made her own choice, marrying an English knight named John Russell. Sir John’s background is obscure but, despite assertions that he was low born, he had connections at the English court. Isabella and John obtained royal consent for their marriage c.1260, and the happy couple also took crusading vows soon afterwards.

But whatever his wife thought, in the eyes of the Scottish nobility John Russell cut a much less impressive figure than Walter Comyn. The couple had not been married long before a powerful coterie of nobles descended on Menteith like hoodie-crows. Pope Urban’s list of persecutors includes the earls of Buchan, Fife, Mar, and Strathearn, Alan Durward, Hugh of Abernethy, Reginald le Cheyne, Hugh de Berkeley, David de Graham, and many others. But the ringleader was John ‘the Red’ Comyn, the nephew of Isabella of Menteith’s deceased husband Walter, who had already succeeded to the lordship of Badenoch. Even though Menteith belonged to Isabella in her own right, Comyn coveted his late uncle’s title there. Supported by the other lords, he captured and imprisoned the countess and John Russell, and justified this bold assault by claiming that the newlyweds had conspired together to poison Earl Walter. It is unclear what proof, if any, John Comyn supplied to back up his claim, but the couple were unable to disprove it. They were forced to surrender all claims to Isabella’s dowry, as well as many of her own lands and rents. A surviving charter shows that Hugh de Abernethy was granted property around Aberfoyle about 1260, but it seems that the lion’s share of the spoils went to the Red Comyn, who secured for himself and his heirs the promise of the earldom of Menteith itself.

Isabella and her husband were only released when they promised to pass into exile until they could clear their names before seven peers of the realm. John Russell’s brother Robert was delivered to Comyn as security for their full resignation of the earldom. Having ‘incurred heavy losses and expenses’, which certainly stymied their crusading plans, they fled.

In a letter of 1264, Pope Urban IV described the couple as ‘undefended by the authority of the king, while as yet a minor’. However, though Alexander III was technically underage in 1260, he was now nineteen and could not be ignored entirely. Michael Brown suggests that Isabella and her husband may have been seized when the king was visiting England, and that John Comyn’s unsanctioned bid for the earldom of Menteith may explain why Alexander cut short his stay in November 1260 and hastily returned north, leaving his pregnant queen with her parents at Windsor. Certainly, Comyn was forced to relinquish the earldom before 17th April 1261. But instead of restoring Menteith to its exiled countess, Alexander settled the earldom on another rising star: Walter ‘Bailloch’ Stewart, whose wife Mary had a claim to Menteith.

Mary of Menteith is often described as Isabella’s younger sister, although contemporary sources never say so and some historians argue that they were cousins. Either way, Alexander’s decision to uphold her claim was probably as much influenced by her husband’s identity as her alleged birth right. Like Walter Comyn, Walter Bailloch (‘freckled’), belonged to an influential family as the brother of Alexander, Steward of Scotland. From their origins in the royal household, the Stewarts became major regional magnates, assisting royal expansion in the west. The promising son of a powerful family, Walter Bailloch was sheriff of Ayr by 1264 and likely fought in the Battle of Largs in 1263. In 1260 Alexander III had the opportunity to secure Walter’s loyalty as the royal minority drew to a close. Conversely John Comyn of Badenoch found himself out of favour and was removed as justiciar of Galloway following the Menteith incident. The king would not alienate the Comyns permanently, but for now, the stars of Walter Bailloch and Mary of Menteith were in the ascendant.

(Loch Lubnaig, in the Trossachs, another former possession of the earls of Menteith)

Isabella of Menteith and John Russell had not been idle in the meantime. Travelling to John’s home country of England, they probably appealed to Henry III. In September 1261, the English king inspected documents relating to a previous dispute over the earldom of Menteith. On that occasion, two brothers, both named Maurice, had their differences settled before the future Alexander II at Edinburgh in 1213. The elder Maurice, who held the title Earl of Menteith and was presumed illegitimate by later writers (though this is never stated), resigned the earldom, which was regranted to Maurice junior. In return the elder Maurice received some towns and lands to be held for his lifetime only, and the younger Maurice promised to provide for the marriage of his older brother’s daughters.

It is probable that Isabella was the daughter of the younger Maurice, and that she produced these charters as proof of her right to the earldom. Perhaps Mary was her younger sister, but it seems likelier that Isabella would have wanted to prove the younger Maurice’s right if Mary was a descendant of the elder brother, and therefore her cousin. However despite Henry III’s formal recognition of the settlement, he did not provide Isabella with any real assistance: for whatever reason, the English king was either unable or unwilling to press his son-in-law the King of Scots on this matter. Isabella then turned instead to the spiritual leader of western Europe- Pope Urban IV.

(A depiction of the coronation of Henry III of England, though in fact the English king was only a child when he was crowned. Source: Wikimedia Commons)