#vasily stalin

Text

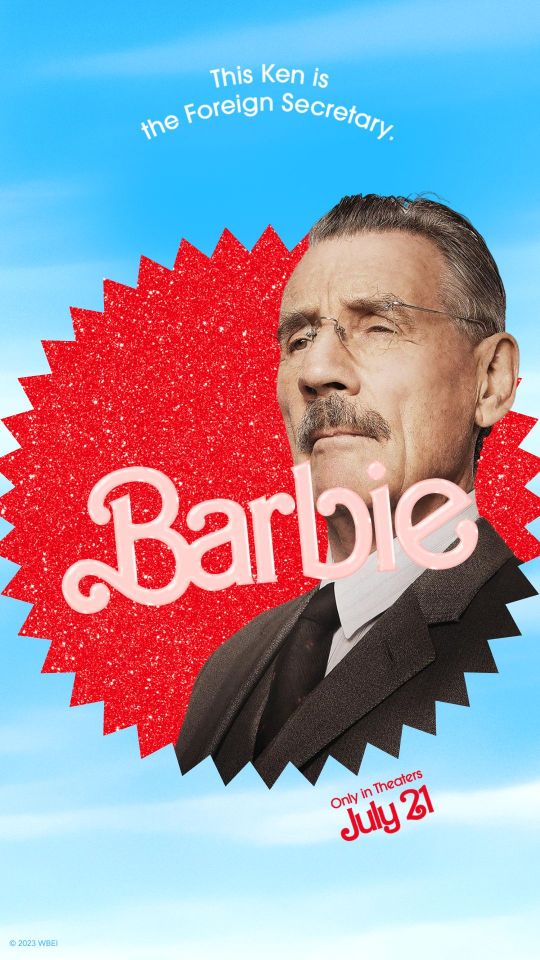

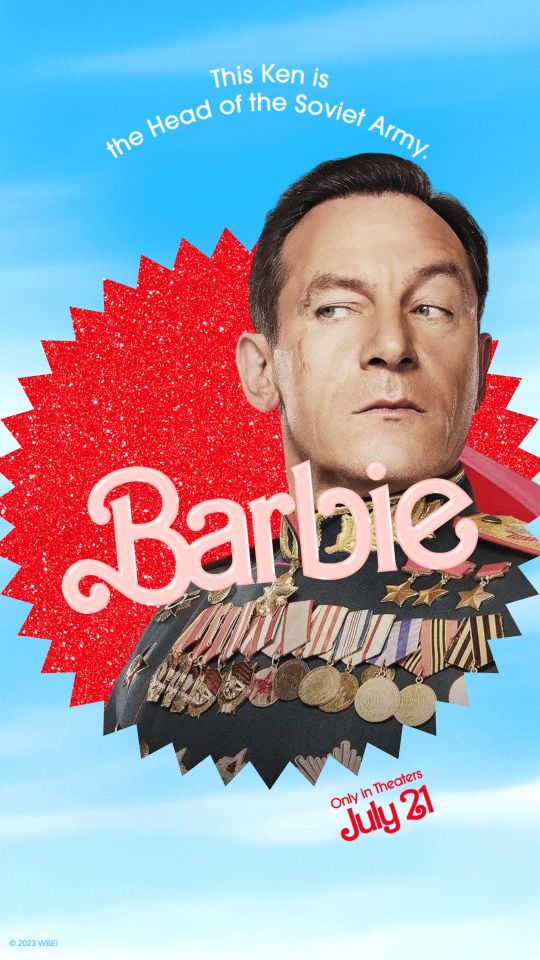

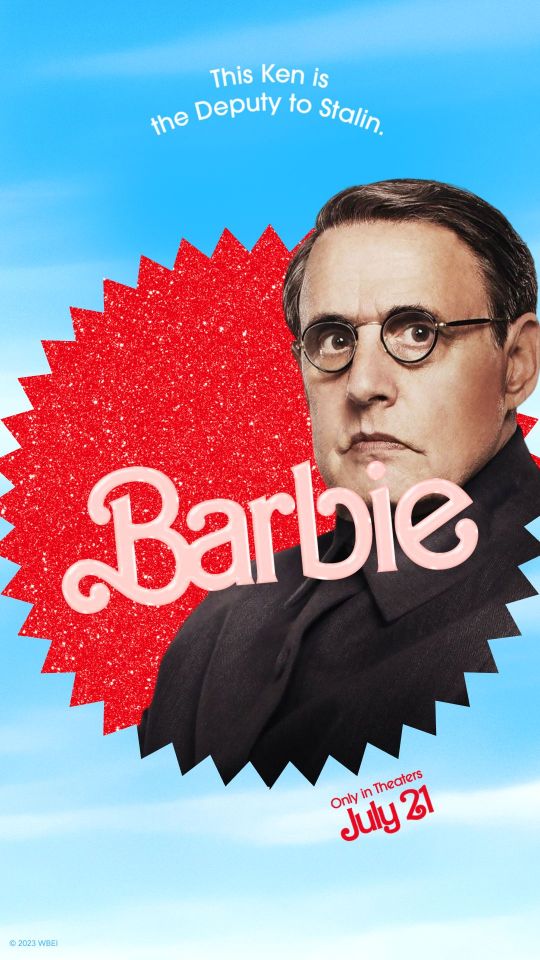

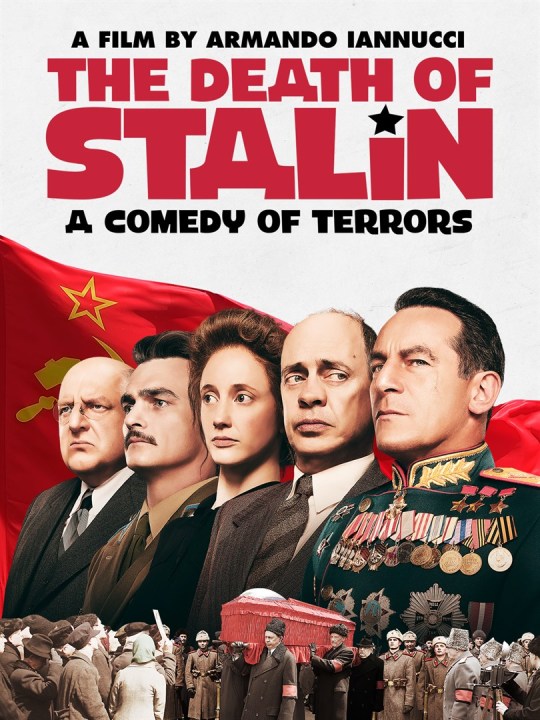

The Death of Stalin, but the poster is... Barbie?!

#the death of stalin#death of stalin#michael palin#steve buscemi#jason isaacs#simon russell beale#jeffrey tambor#rupert friend#andrea riseborough#paul whitehouse#armando iannucci#vyacheslav molotov#nikita khrushchev#georgy zhukov#lavrentiy beria#georgy malenkov#vasily stalin#svetlana alliluyeva#anastas mikoyan#forgot i made this#for some reason i cant find photos of the og poster with bulganin and kaganovich#why??? are they late??? sorry#anyways!!#late barbie post#viv's post#viv's edit

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't want you to be young and beautiful. I only want one thing. I want you to be kind-hearted - and not just towards cats and dogs.

vasily grossman, life and fate

#self care is reading russian classics#books#one of my favorite things#love books#writers#i love reading#i am a writer#readers on tumblr#connecting with readers#life and fate#vasily grossman#ww2 history#ww2#stalin#marxism leninism#writing#writers on tumblr#love of my life#reader#currently reading#i'm reading it right now#reading#long reads#books and reading#to read#reader insert#read free ebooks#book readers#writers and readers#readers

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Before slaughtering infected cattle, various preparatory measures have to be carried out: pits and trenches must be dug; the cattle must be transported to where they are to be slaughtered; instructions must be issued to qualified workers.

If the local population helps the authorities to convey the infected cattle to the slaughtering points and to catch beasts that have run away, they do this not out of hatred of cows and calves, but out of an instinct for self-preservation.

Similarly, when people are to be slaughtered en masse, the local population is not immediately gripped by a bloodthirsty hatred of the old men, women and children who are to be destroyed. It is necessary to prepare the population by means of a special campaign. And in this case it is not enough to rely merely on the instinct for self-preservation; it is necessary to stir up feelings of real hatred and revulsion.

It was in such an atmosphere that the Germans carried out the extermination of the Ukrainian and Byelorussian Jews. And at an earlier date, in the same regions, Stalin himself had mobilized the fury of the masses, whipping it up to the point of frenzy during the campaigns to liquidate the kulaks as a class and during the extermination of Trotskyist-Bukharinite degenerates and saboteurs.

Experience showed that such campaigns make the majority of the population obey every order of the authorities as though hypnotized. There is a particular minority which actively helps to create the atmosphere of these campaigns: ideological fanatics; people who take a bloodthirsty delight in the misfortunes of others; and people who want to settle personal scores, to steal a man's belongings or take over his flat or job. Most people, however, are horrified at mass murder, but they hide this not only from their families, but even from themselves. These are the people who filled the meeting-halls during the campaigns of destruction; however vast these halls or frequent these meetings, very few of them ever disturbed the quiet unanimity of the voting. Still fewer, of course, rather than turning away from the beseeching gaze of a dog suspected of rabies, dared to take the dog in and allow it to live in their houses. Nevertheless, this did happen.

The first half of the twentieth century may be seen as a time of great scientific discoveries, revolutions, immense social transformations and two World Wars. It will go down in history, however, as the time when - in accordance with philosophies of race and society - whole sections of the Jewish population were exterminated. Understandably, the present day remains discreetly silent about this.

One of the most astonishing human traits that came to light at this time was obedience. There were cases of huge queues being formed by people awaiting execution - and it was the victims themselves who regulated the movement of these queues. There were hot summer days when people had to wait from early morning until late at night; some mothers prudently provided themselves with bread and bottles of water for their children. Millions of innocent people, knowing that they would soon be arrested, said goodbye to their nearest and dearest in advance and prepared little bundles containing spare underwear and a towel. Millions of people lived in vast camps that had not only been built by prisoners but were even guarded by them.

And it wasn't merely tens of thousands, or hundreds of thousands, but hundreds of millions of people who were the obedient witnesses of this slaughter of the innocent. Nor were they merely obedient witnesses: when ordered to, they gave their support to this slaughter, voting in favour of it amid a hubbub of voices. There was something unexpected in the degree of their obedience.

There was, of course, resistance; there were acts of courage and determination on the part of those who had been condemned, there were uprisings; there were men who risked their own lives and the lives of their families in order to save the life of a stranger. But the obedience of the vast mass of people is undeniable.

What does this tell us? That a new trait has suddenly appeared in human nature? No, this obedience bears witness to a new force acting on human beings. The extreme violence of totalitarian social systems proved able to paralyse the human spirit throughout whole continents.

A man who has placed his soul in the service of Fascism declares an evil and dangerous slavery to be the only true good. Rather than overtly renouncing human feelings, he declares the crimes committed by Fascism to be the highest form of humanitarianism; he agrees to divide people up into the pure and worthy and the impure and unworthy.

The instinct for self-preservation is supported by the hypnotic power of world ideologies. These call people to carry out any sacrifice, to accept any means, in order to achieve the highest of ends: the future greatness of the motherland, world progress, the future happiness of mankind, of a nation, of a class.

One more force co-operated with the life-instinct and the power of great ideologies: terror at the limitless violence of a powerful State, terror at the way murder had become the basis of everyday life.

The violence of a totalitarian State is so great as to be no longer a means to an end; it becomes an object of mystical worship and adoration. How else can one explain the way certain intelligent, thinking Jews declared the slaughter of the Jews to be necessary for the happiness of mankind? That in view of this they were ready to take their own children to be executed - ready to carry out the sacrifice once demanded of Abraham? How else can one explain the case of a gifted, intelligent poet, himself a peasant by birth, who with sincere conviction wrote a long poem celebrating the terrible years of suffering undergone by the peasantry, years that had swallowed up his own father, an honest and simple-hearted labourer?

Another fact that allowed Fascism to gain power over men was their blindness. A man cannot believe that he is about to be destroyed. The optimism of people standing on the edge of the grave is astounding. The soil of hope - a hope that was senseless and sometimes dishonest and despicable - gave birth to a pathetic obedience that was often equally despicable.

The Warsaw Rising, the uprisings at Treblinka and Sobibor, the various mutinies of brenners, were all born of hopelessness. But then utter hopelessness engenders not only resistance and uprisings but also a yearning to be executed as quickly as possible.

People argued over their place in the queue beside the blood-filled ditch while a mad, almost exultant voice shouted out: 'Don't be afraid, Jews. It's nothing terrible. Five minutes and it will all be over.'

Everything gave rise to obedience - both hope and hopelessness.

It is important to consider what a man must have suffered and endured in order to feel glad at the thought of his impending execution. It is especially important to consider this if one is inclined to moralize, to reproach the victims for their lack of resistance in conditions of which one has little conception.

Having established man's readiness to obey when confronted with limitless violence, we must go on to draw one further conclusion that is of importance for an understanding of man and his future.

Does human nature undergo a true change in the cauldron of totalitarian violence? Does man lose his innate yearning for freedom? The fate of both man and the totalitarian State depends on the answer to this question. If human nature does change, then the eternal and world-wide triumph of the dictatorial State is assured; if his yearning for freedom remains constant, then the totalitarian State is doomed.

The great Rising in the Warsaw ghetto, the uprisings in Treblinka and Sobibor; the vast partisan movement that flared up in dozens of countries enslaved by Hitler; the uprisings in Berlin in 1953, in Hungary in 1956, and in the labour-camps of Siberia and the Far East after Stalin's death; the riots at this time in Poland, the number of factories that went on strike and the student protests that broke out in many cities against the suppression of freedom of thought; all these bear witness to the indestructibility of man's yearning for freedom. This yearning was suppressed but it continued to exist. Man's fate may make him a slave, but his nature remains unchanged.

Man's innate yearning for freedom can be suppressed but never destroyed. Totalitarianism cannot renounce violence. If it does, it perishes. Eternal, ceaseless violence, overt or covert, is the basis of totalitarianism. Man does not renounce freedom voluntarily. This conclusion holds out hope for our time, hope for the future.” (p. 213 - 216)

The Moloch of Totalitarianism in the Levashovo Wasteland, St. Petersburg, Russia

#grossman#vasily grossman#life and fate#totalitarianism#hitler#stalin#wwiii#world war 2#obediance#hoplessness#holocaust#holodomor#nazi#communism#fascism#russia#germany#russian lit#russian literature#soviet literature#books#bookshelf#library#book lover#moloch

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In these last few months of war, from January to May 1945, the inmates of the German concentration camps died in very large numbers. Perhaps three hundred thousand people died in German camps during this period, from hunger and neglect. The American and British soldiers who liberated the dying inmates from camps in Germany believed that they had discovered the horrors of Nazism. The images their photographers and cameramen captured of the corpses and the living skeletons at Bergen-Belsen and Buchenwald seemed to convey the worst crimes of Hitler. As the Jews and Poles of Warsaw knew, and as Vasily Grossman and the Red Army soldiers knew, this was far from the truth. The worst was in the ruins of Warsaw, or the fields of Treblinka, or the marshes of Belarus, or the pits of Babi Yar. The Red Army liberated all of these places, and all of the bloodlands. All of the death sites and dead cities fell behind an iron curtain, in a Europe Stalin made his own even while liberating it from Hitler ... The ashes of Warsaw were still warm when the Cold War began."

Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands, 311-312

#tw: holocaust#cw: holocaust#cold war#ww2#I've probably posted this quote here before#but godDAMN timothy#the ELOQUENCE

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

According to Russia’s propaganda outlets, one of the goals of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine is to fight back against the "sexual permissiveness" and “moral decay of the West." Since the war began, Russian politicians and pro-government news net have flooded the airwaves with stories about the “depravity” of the Ukrainian army, repeatedly equated homosexuality with pedophilia, and presented Russian troops as heroes fighting for “traditional values.” But however absurd this rhetoric may be, it’s not new or unique: throughout history, these same ideas have repeatedly arisen in a variety of dictatorships, from Hitler’s Germany and Stalin's Russia to Gambia and Uganda in the 21st century. Meduza explains why authoritarians on both the right and the left can be counted on to persecute LGBT+ people.

Do we really want kids in Russia to have Parent No. 1 and Parent No. 2? Have we lost our minds? Do we really want our kids to have it drilled into their heads that there are more genders than sexes? Do we really want our schools to hammer perversions into their heads that lead to degradation and extinction?

So went one of Vladimir Putin’s numerous digressions during his speech at the signing ceremony for the treaties on Russia annexing four partially-occupied Ukrainian territories last month.

In recent years, the Russian president’s rhetoric surrounding LGBT people has gotten crueler and more intense. In 2014, for example, after signing the law banning “gay propaganda” among minors in Russia, Putin pointed out that “non-traditional relationships” themselves were still legal in Russia, denying accusations from human rights groups that the new law was discriminatory. On the other hand, in the same speech, he went on to name “homosexualism” and “pedophilia” as part of the same list, implying a similarity or connection between them. Even earlier, in 2013, he said that “in Euro-Atlantic countries, moral principles and traditional identity are being denied. [Those countries] are implementing policies that put multi-children families on the same level as same-sex partnership, and faith in God on the same level as faith in Satan.”

In addition to maligning LGBT+ people, Putin has told bogus stories about how, in Western countries, “there’s serious talk of registering parties that aim to promote pedophilia.” The party he was likely referring to was created in the Netherlands in 2006 and only had three members. It disbanded in 2010 after widespread public outrage.

Nonetheless, while Putin used to at least pretend that LGBT+ people have the same rights in Russia as everybody else (apart from the “propaganda” law), he now speaks about them as a force to be fought against. Moreover, in his annexation speech, Putin effectively said that one of the goals of Russia’s Ukraine invasion is to prevent the normalization in Russia of all sexualities not sanctioned by the state.

Meanwhile, for Putin and his propagandists, the idea that there are more than two genders has gone from a “perversion” to an “existential threat to the country and its people.” In Russian state discourse, homosexuality has rapidly became as inherent a characteristic of Russia’s enemies as their “commitment to Nazi or fascist ideas." On October 1, for example, pro-Kremlin film actor and Russian State Duma deputy Dmitry Pevtsov claimed Russian troops are fighting for “families to consist of a mom, a dad, and children — not some guy, some other guy, and some other who-knows-what.” And on a Russian talk show in May, he said that “militant faggots have become the main defenders of Ukrainian values.”

The Russian authorities’ rhetoric surrounding gender and sexuality bears a remarkable resemblance to that of numerous other totalitarian, authoritarian, and dictatorial regimes. To gain insight into why this form of intolerance consistently plays an integral role in how dictators maintain power, Meduza turned to history.

The Nazis simultaneously despised and feared LGBT people

The idea of a government-recognized union between one man and one woman as the only permissible kind of romantic relationship is one of the fundamental principles of most fascist regimes. What's more, both members of the relationship must understand their gender in a way that “matches” their sex characteristics; most fascist governments have considered cross-dressing and being transgender just as “deviant” as sex between two men, for example. It’s no accident that in Vichy France, the state motto was changed from Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité (Freedom, Equality, Brotherhood) to Travail, Famille, Patrie (Work, Family, Homeland).

In the Third Reich, LGBT+ people faced mass persecution and were declared a threat to the welfare of the state and of the people. In the minds of Nazi propagandists, gay people were the antithesis of everything Aryan patriots were supposed to embody: asceticism, masculinity, and a willingness to forego pleasure and entertainment to devote oneself to the homeland and the Führer.

Sexual “perversion” in Hitler’s Germany was seen as a remnant of the decadence and hedonism of the Weimar Republic. The Nazis sought to cut all ties with their predecessor state and tightened legislation criminalizing sexual relations between men. Beginning in 1933, when the National Socialist Party came to power and Hitler’s dictatorship was established, prosecution for homosexuality no longer required even physical evidence — it was enough to bring a witness statement from a “law-abiding citizen” who claimed to have seen a suspect look too intensely at another man.

Like in many dictatorships, the image of LGBT+ people that the Nazis pushed was based on two contradictory premises. The first was that LGBT+ people were weak, pathetic, sick people who didn’t deserve to be a part of society. The second was that homosexuality was passed down like a deadly virus and could destroy German society from within if the proper measures weren’t taken to defeat it.

Thus, on one hand, LGBT people were cast as subhumans who deserved contempt, while on the other hand, they were accused of being some of the most dangerous and insidious enemies of the state. The propaganda failed to explain how a group so weak could simultaneously be so powerful.

“In nazi propaganda, homosexuals were generally portrayed as soft, cowardly, cringing, and untrustworthy creatures,” Dutch historian Harry Oosterhuis has written. “[But] in Hitler's and Himmler's view they nonetheless appeared to possess an imperious character and to have at their disposal special intuitions and aptitudes which were withheld from 'normal' men. They were capable of strongly organizing in secret and thereupon making a grab for power.”

In the 12 years the Third Reich existed, according to historians’ estimates, about 100,000 men were arrested for allegedly engaging in “unnatural sexual acts.” Out of the 53,400 men convicted, between 5,000 and 15,000 were sent to concentration camps. The rest were given prison sentences or forced to undergo “treatment.” Persecution against LGBT+ people also got worse as time went on: from January 1933 to June 1935, about 4,000 men were charged for “unnatural sexual acts,” while from June 1935 to June 1938, the number rose to at least 40,000.

Communist regimes were no friendlier

In 1934, an openly gay Scottish journalist and communist named Harry Whyte wrote an open letter to Joseph Stalin. He wanted to explain to the Soviet leader why, in his view, “a homosexual [can be] considered someone worthy of membership in the Communist Party.” At the time, Whyte had been living in the USSR for several years, working as a writer for the English-language Soviet propaganda outlet the Moscow Daily News. Quoting letters written by Marx and Engels, as well as Stalin's own speeches, Whyte criticized the way gay men were treated under capitalism and fascism. He said that even when he had visited Soviet psychiatrists and asked them to “cure” him, they had admitted this might be impossible. He went on to liken the fight for gay rights to the struggle for women's rights.

Whyte expected Stalin to be receptive to his arguments — and to take a kinder view of gay men than that of the British authorities. Instead, the dictator’s response was brief and hostile: “An idiot and a degenerate.”

Shortly after, Harry Whyte left the Soviet Union and was kicked out of the Communist party — but not before Maxim Gorky published a response to his letter in the Soviet newspaper Pravda. “In a country where the proletariat manages courageously and successfully,” Gorky wrote, “homosexuality, which corrupts young people, is recognized as socially criminal and is punished.”

Despite universal equality officially serving as one of the principal ideals of communist and socialist regimes, LGBT people in the Soviet Union found themselves in similar circumstances to those of queer people in fascist dictatorships. The decade that followed the relatively free 1920s was marked by the passage of legislation even more reactionary and repressive than that of the Russian Empire. Like the Nazis, Soviet leaders viewed LGBT+ people with both contempt and fear. In official discourse, gay people were depicted as untrustworthy figures predisposed to deception and betrayal.

The year before Whyte’s letter, the USSR’s Central Executive Committee criminalized “sodomy," making voluntary sex between two men punishable by up to five years in prison.

However, unlike in fascist regimes, where persecution against gay and trans people took place primarily among the general population, "sodomy" allegations in the Soviet Union were frequently used as a pretext for political purges. Facing a “sodomy” charge under Stalin's government was tantamount to being accused of treason.

Over the next 60 years, about 60,000 people were convicted of “sodomy.” Having these charges on one’s record often made it impossible to find work or enroll in university.

Fidel Castro’s Cuba was another communist state in which LGBT+ people faced brutal repressions. For decades after Castro's rise to power in 1959, LGBT+ people were sent to labor camps and forced to publicly renounce their “criminal predilections.” Police arrested men whose behavior they deemed “feminine” or who dressed “like a hippy.” To extract confessions from gay men, investigators would wrap them in barbed wire or bury them up to their neck and deprive them of food and water.

Castro normalized and encouraged homophobia among the public as well. Like current Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, the Cuban dictator held that “there are no homosexuals in this country.”

The masculinity cult

Nina Khrushcheva, a professor of international affairs at The New School and the granddaughter of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, has attributed authoritarian leaders’ consistent persecution of LGBT+ people to their constant need to emphasize their own strength. The image of a man as the embodiment of masculinity, she writes, is connected in these leaders’ minds with the “natural order of things,” the violation of which poses an immediate threat to their continued power. For dictators and their devotees, queer people provoke not just disgust and confusion but also fear, because they represent an “alternative” order.

Under totalitarianism, homophobic discourse is usually predicated on the idea that if same-sex relationships or non-binary gender identities are normalized, there will be no place for “normal” people in the “new” world. Despite the fact that it’s LGBT+ people who have consistently faced persecution under fascist and communist regimes, dictators promote the idea that queer people are the ones who pose a danger to others. As Khrushcheva wrote in a 2021 column:

These leaders' reliance on “hegemonic masculinity” – the idea that men should be strong, tough, and dominant – to bolster their position should not be surprising. Authoritarian states are fundamentally weak, and dictators are fundamentally insecure. So, they constantly attempt to project strength.

But in today's fast-changing world, ordinary people are feeling insecure, too – especially those who think their traditionally “dominant” positions are being eroded. That makes them eager to embrace strongmen who promise a return to the order and predictability of a more socially rigid past. In other words, people are afraid of change, and think they need macho leaders and patriarchal rules to protect them.

The first order of business for authoritarian leaders seeking to scapegoat queer people is to convince the population that minority sexualities are dangerous. To that end, they usually claim that there’s a correlation between the sexuality or gender identity they disapprove of and some imagined negative trait. For example, authorities might claim that LGBT+ people are incapable of engaging in patriotism or living in society without imposing their “deviant” predilections on “normal” people.

To stir up homophobic sentiment among the public, propagandists try to convince the heterosexual and cisgender majority that LGBT+ people’s worldviews and psyches make them something akin to invaders from another planet. This is because it’s much easier for people to hate “aliens” than to hate people who have everything in common with the majority except their sexuality.

Leaders in authoritarian and totalitarian regimes frequently claim that LGBT+ people are a threat to demography, depicting homosexuality or nonbinary gender identities as a virus that can be passed from person to person. State propaganda traditionally seeks to scare people by asserting that the “spread” of homosexuality will lead to a decline in birthrates — and ultimately to extinction. But this is a fantasy: nothing remotely close to this has been observed in any democratic country where same-sex relationships are legal and socially acceptable.

One of the world’s most well-known homophobic leaders was Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s prime minister from 1987 to 2017. When trying to justify his repressive policies against LGBT+ people, Mugabe often presented the same arguments Vladimir Putin has begun using in recent years: that gay people are “harmful” and “unnatural,” and that their supporters are either “idiots” or “Satanists.”

In the years since Mugabe’s rule came to an end, Zimbabwe has seen the opening of its first health clinics for gay and bisexual men — a step lauded by the local LGBT+ community as a “historic victory.” In other African dictatorships such as Uganda, however, state-sanctioned homophobia continues to thrive.

After inculcating homophobia among the public, dictators themselves usually shape their own public image around stereotypes of masculinity, contrasting themselves with people who don’t fit into their “traditional” conceptions of manhood. And because citizens’ primary responsibility in authoritarian regimes is to buttress the state, LGBT+ people are stigmatized and demonized for not fitting into the model of the “classic” family and for showing their individuality — something authoritarian governments strive to suppress.

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Movie #13 of 2024: The Death of Stalin

Svetlana Stalin: "Can you please just be cordial?"

Vasily Stalin: "I know the drill. Smile, shake hands and try not to call them cunts."

Svetlana Stalin: "Perfect. That's perfect."

#the death of stalin#comedy#drama#history#armando iannucci#fabien nury#thierry robin#david schneider#ian martin#peter fellows#christopher willis#zac nicholson#peter lambert#english#red dragon#2018#13

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

when you're Vasily Stalin and the Soviet Air Force ice hockey team you're coaching just died in a plane accident caused by a snowstorm

174 notes

·

View notes

Note

Seeing your fancasts for Thranduil's sons full on made me wheeze because my family rewatched The Death of Stalin recently and seeing Rupert Friend's face made me immediately picture Prince Arvellas screaming Vasily's line "Play better, you clattering fannies!!!"

An unintended consequence I'm sure but it did amuse me

LOL! I have yet to watch that movie, but I can imagine! Rupert Friend is so wonderfully talented with amazing range that makes him a chameleon.

I hands-down love him best as Prince Albert in The Young Victoria, and that's what chiefly inspired the Arvellas Thranduilion fancasting.

Plus, him being Orlando Bloom's doppelganger, how could you pass up that chance?

Arvellas is very similar to Prince Albert in character, now that I think about it, but that was not at all intentional. Hmm. I have always been a fan of Albert and his love story with Victoria, so perhaps he does influence my OC creations.

And now for some semi-related gif bombing because I LOVE THIS/His Prince Albert SO MUCH. LOOK HOW BEAUTIFUL.

#sotwk answers#sotwk headcanon#sotwk ocs#thranduil#arvellas thranduilion#thranduilion#rupert friend#sotwk fancast#the young victoria

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

everytime i see him, the strong smart independent woman in me leaves and goes for a little walk

#gela meskhi#viv's post#viv's edit#vasily stalin#THERE WE HAVE IT!!!!!!#screaming crying throwing up

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

thinking of vasily stalin n kendall roy btw

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rewatched The Death of Stalin, audio commentary, and I just love !!!! How this movie breezes past. The pacing is impeccable, never a dull moment, you can rewatch the movie for the 'Vasily wrestling for the gun and failing scene' alone as many times as there are faces in the shot. I didn't have my phone on me, so I just spent 90 minutes blissfully focused and entertained. God bless.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

October: Ten Days That Shook the World (Grigoriy Aleksandrov, Sergei Eisenstein, 1928)

Cast: Nikolay Popov, Vasili Nikandrov, Layaschenko, Chibisov, Boris Libanov, Mikholyev, Nikolai Podvolsky, Smelski, Eduard Tisse. Screenplay: Sergei Eisenstein, Grigoriy Aleksandrov. Cinematography: Eduard Tisse. Production design: Vasili Kovrigin. Film editing: Esfir Tobak.

A whirlwind of action and film editing, October was created to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the revolution that put the Bolsheviks in power and gave birth to the Soviet Union. From the beginning it was subject to ideological scrutiny, withdrawn and re-edited -- to eliminate, among other things, references to Trotsky, who had recently been purged by Stalin. Released internationally as Ten Days That Shook the World, lifting the title of John Reed's bestselling 1919 book, it was compared unfavorably to director Sergei Eisenstein's 1925 film Battleship Potemkin, and even an admirer like Vsevolod Pudovkin, a director who was no stranger to the kind of pressures under which Eisenstein labored in walking the line between art and politics, acknowledged that October was regarded as a "powerful failure." The film fails for us today to craft a clear-sighted account of the critical moments leading up to its spectacular climax, the storming of the Winter Palace. Eisenstein's montage techniques, used so powerfully in Strike (1925) and Battleship Potemkin, sometimes feel obvious and superficial, as in the anti-religious montage linking an image of Jesus with images from other religions, concluding with a prehistoric idol, or the juxtaposition of Alexander Kerensky with a mechanical peacock. But as an action movie, it's compelling, from the scene in which the Provisional Government raises the bridges to shut off the protesters, trapping some of them, along with an unfortunate horse, in the machinery, to the final assault on the Winter Palace. Never subtle, and never convincing as an accurate version of history, October still has an aura of epic grandeur. Perhaps it's only for us to feel the irony in the film's opening sequence, pulling down a statue of Alexander III, which echoes for us not only the images of Saddam Hussein's statue being toppled but also Vladimir Putin's dedication of a new statue to the same czar in 2017.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Nearly all the accused had been savagely beaten. Bukharin was spared this but was visibly a broken man. From his prison cell he had written a note to Stalin: 'Koba, why is my death necessary for you?' But Stalin wanted blood. Constantly consulted by Chief Prosecutor Andrei Vyshinski and Vasili Ulrikh at the end of the court's working day, he ordered that the world's press should be convinced of the veracity of the confessions before sentences were passed. Many Western journalists were indeed hoodwinked. The verdict was announced on 13 March: nearly all the defendants were to be shot.

Two days later Stalin approved a further operation to purge 'anti-Soviet elements’. This time he wanted 57,200 people to be arrested across the USSR. Of these, he and Yezhov had agreed, fully 48,000 were to be rapidly tried by troiki and executed. Yezhov, by now practised at the management of such operations, attended to his duties with enthusiasm. Through spring, summer and autumn 1938 the carnage continued as the NKVD meat-grinder performed its grisly task on Stalin's behalf. Having put Yezhov's hand at the controls and ordered him to start the machine, Stalin could keep it running as long as it suited him.

Stalin never saw the Lubyanka cellars. He did not even glimpse the meat-grinder of the operations. Yezhov asked for and received vast resources for his work. He needed more than his executive officials in the NKVD to complete it. The Great Terror required stenographers, guards, executioners, cleaners, torturers, clerks, railwaymen, truck drivers and informers. Lorries marked ‘Meat' or 'Vegetables’ took victims out to rural districts such as Butovo near Moscow where killing fields had been prepared. Trains, often travelling through cities by night, transported Gulag prisoners to the Russian Far North, to Siberia or to Kazakhstan in wagons designed for cattle. The unfortunates were inadequately fed and watered on the journey, and the climate - bitterly cold in the winter and monstrously hot in summer - aggravated the torment. Stalin said he did not want the NKVD's detainees to be given holiday-home treatment. The small comforts that had been available to him in Novaya Uda, Narym, Solvychegodsk or even Kureika were systematically withheld. On arrival in the labour camps they were kept constantly hungry. Yerhov's dieticians had worked out the minimum calorie intake for them to carry out heavy work in timber felling, gold mining or building construction; but the corruption in the Gulag was so general that inmates rarely received their full rations - and Stalin made no recorded effort to discover what conditions were really like for them.

Such was the chaos of the Great Terror that despite Stalin's insistence that each victim should be formally processed by the troiki, the number of arrests and executions has not been ascertained with exactitude. Mayhem precluded such precision. But all the records, different as ther are about details, point in the same general direction. Altogether it would seem that a rough total of one and a half million people were seized by the NKVD in 1937-8. Only around two hundred thousand were eventually released. To be caught in the maw of the NKVD usually meant to face a terrible sentence. The troiki worked hard at their appalling task. The impression got around - or was allowed to get around - that Stalin used nearly all of the arrestees as forced labourers in the Gulag. In fact the NKVD was under instructions to deliver about half of its victims not to the new camps in Siberia or north Russia but to the execution pits outside most cities. Roughly three quarters of a million persons perished under a hail of bullets in that brief period of two years. The Great Terror had its ghastly logic.” - Robert Service, ‘Stalin: A Biography’ (2004) [p. 355 - 356]

#stalin#josef stalin#service#robert service#great terror#gulag#nkvd#soviet union#ussr#cccp#communism#russia#koba

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vasyl Ovsienko is a Ukrainian philologist who came of age in the late 1960s. In those years, as an advocate for Ukrainian language and culture, he found himself in constant tension with his Soviet surroundings, and his sharing of samizdat, or self-published illegal literature, eventually landed him in prison. Ovsienko ultimately spent more than 13 years in Soviet prisons, which culminated in a seven-year stay in a camp for “dangerous recidivists” in Russia’s Perm region. Meduza special correspondent Kristina Safonova tells his story.

If you go mushroom hunting in the woods near the town of Chusovoy in Russia’s Perm region, you’ll come across the ruins of prison camp barracks, says 76-year-old historian Viktor Shmyrov, who grew up nearby.

Shmyrov’s earliest memory associated with the camps is of the word “arrestee,” which is what prisoners were called in pre-revolutionary times. Though the word was taken out of official use in the Soviet era, Shmyrov’s family continued to use it. “At home, the fact that lots of people were being held in camps was discussed openly,” Shmyrov recalls. “It was clear to everyone in the family that Stalin was a criminal.”

Shmyrov remembers going with other boys to a place by the river known to locals as Yermak Cave (after the legendary Cossack leader Yermak Timofeyevich). Along the way, he saw fallen towers and crumpled barbed wire.

"I didn't know it was a camp, but it made such an impression on me. I realized it was a place of evil, of pain," Shmyrov says.

A philologist from a Ukrainian village

Barbed wire and more barbed wire. At least seven fences surrounded the camp in the Perm region where Vasyl Ovsienko was imprisoned from 1981 to 1987 on charges of anti-Soviet campaigning and propaganda.

Ovsienko was born in 1949 in Lenino, a village in Ukraine’s Zhytomyr region. As a child, when asked about his father, he climbed up on a bench and pointed to a calendar with a portrait of Stalin.

Vasyl came from an ordinary peasant family: his father had gone to school for two years, his mother hadn’t gone at all. But even in his school years, he was interested in literature and wrote poetry, some of which was published in the local newspaper “Zarya Polesia.”

That was in the mid-1960s. Vasily Skuratovsky, who later became a famous ethnographer, worked at the newspaper. It was from him that Ovsienko first learned about the Ukrainian shestidesyatniki, or "Sixtiers” — members of the intelligentsia who spoke out in defense of Ukraine’s national language and culture, as well as creative freedom, beginning in the late 1950s. They chose nonviolent methods of resistance: journalism and samizdat (self-published illegal literature), literary meetings and memorial evenings, and theater performances and youth clubs.

Even so, in 1965, the authorities arrested more than 20 people involved in the movement. In response, their self-published work, which had primarily consisted of poetry at first, became more political. Though many of them had started out as supporters of “socialism with a human face,” the “Sixtiers” gradually became dissidents.

The first book from one of the “Sixtiers” that Ovsienko encountered was the typewritten diary of the poet and journalist Vasily Symonenko. In 1967, Ovsienko had just begun to study philology at Kyiv State University. “Being a Ukrainian philologist, or even just a Ukrainian in Kyiv, meant being in constant tension with your surroundings,” Ovsienko recalled. Unlike many people in Kyiv, he preferred his native Ukrainian to the Russian language, and as a result, he faced constant questions from others: “‘Are you from Western Ukraine? From Transcarpathia? I don’t understand! Speak normally!’”

Despite the risk of being expelled, Ovsienko recopied Symonenko’s unpublished poems. A year later, he began distributing “Sixtiers’” texts to students. "For five years, nobody ratted me out," he said.

After university, Ovsienko went to the village of Tashan in the Kyiv region to teach Ukrainian language and literature, but he didn’t lose touch with the “Sixtiers.” In January 1972, the Soviet authorities arrested almost all of the leaders of the Ukrainian dissident movement. But Ovsienko and two other graduates of Kyiv State University, Vasily Lisovoy and Evgeniy Pronyuk, remained active.

In the summer of that year, Lisovoy and Pronyuk were arrested. Ovsienko was taken into custody on March 5, 1973, the twentieth anniversary of Stalin’s death.

"They blackmailed me, threatening to put me in a mental hospital. … They pressured me, manipulated me, and I gave up. I named the people I gave samizdat to and those who gave it to me,” Ovsienko said years later.

His friends were summoned for interrogations; some lost their jobs, while others were kicked out of the university. Mikhail Yakubovsky, a former roommate to whom Ovsienko had lent Dzyuba’s work, spent 11 months in a psychiatric hospital.

Lisovoy and Pronyuk were sentenced to seven years. (Lisovoy also received three years in exile, while Pronyuk got five). Ovsienko was sentenced to four years. Subsequently, he retracted his confession.

"I had no complaints, and still have no complaints, against Vasily Lisovoy for regularly giving me samizdat, but I do lament that no one taught me how to behave when we were arrested,” Ovsienko said years later. “There were no such instructions. Except the moral law inside me. And in me, that law turned out to be weak. This weakness was exacerbated by the fact that I didn’t consider my actions criminal and couldn’t help being surprised that the investigation treated them as crimes.”

He spent his first term in Mordovian political camps among "especially dangerous state criminals”: "anti-Soviet" people who had participated in national liberation movements in Western Ukraine and the Baltic states.

Ovsienko’s first year in the camps strengthened his resolve. “I quickly came to my senses in this environment, and by the end of 1974, I was already participating in the protests [such as strikes and hunger strikes] that were taking place there,” he recalled.

Ovsienko returned to his native village in 1977. In November of the following year he was arrested again, this time for allegedly resisting a policeman.

This occurred after Ovsienko, who was under KGB surveillance, was visited by Oksana Meshko, the head of the human rights organization Ukrainian Helsinki Group (UHG), and Olha Babych, the sister of the imprisoned dissident Serhiy Babych.

Later that day, Ovsienko, Meshko, and Babych were arrested without explanation. A week later, Ovsiyenko was told that he had “hindered police officers in the performance of their official duties,” “insulted them with obscene words,” and tore two buttons from an officer’s coat. He was sentenced to three years in prison. This time he served his sentence in criminal detention units in Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia and Zhitomir regions.

Ovsienko received his third conviction just six months before he was slated to be released. KGB officers initially tried to get him to testify against other dissidents from Ukraine; when that proved impossible, they charged him with spreading anti-Soviet propaganda. He was sentenced to ten years in minimum security camps and five years in exile. As a result, in 1981, Ovsienko was found to be a "particularly dangerous recidivist," and ended up in VS-389/36, a prison near the Chusovaya River that was notorious for its harsh conditions.

The camp was divided into two parts: one for inmates of the cell block, the other for inmates who were allowed out into the yard. Ovsienko belonged to the first category. His barracks was surrounded by a three-meter fence. "Apart from this fence, you could see nothing from the cells except — if you stood on a stool — the tops of trees half a kilometer away in the woods," he said.

There were between two and eight people in the cell, and not much space. There were bunk beds, a table, two heavy benches or stools, sometimes a small cupboard, a washbasin, and a raised toilet in the corner.

“It’s psychological torture,” Ovsienko recalled. “They re-educate you into human cattle.” Almost every prisoner had intestinal problems. The cells always stank, and there were sometimes water shortages.

The daily food ration included cereals, potatoes and cabbage, 15 grams of sugar, 5 grams of fat, 20 grams of meat or 50 grams of fish, and 600 grams of bread. The water was "dirty, swampy, and stinky,” Ovsienko said.

Prisoners were allowed to spend up to an hour a day in a small courtyard surrounded by a high fence with barbed wire on top. Much of their time was devoted to work, such as assembling parts of electric irons and attaching them to cords. If the guards wanted to punish someone, they could easily find a loose screw.

There were constant searches. Osvienko said he was often strip-searched three times a day. Dust in the cell, an unironed collar, or failing to be "frank in conversation" were considered violations.

The punishment was 15 days in an isolation cell — and after that, you could immediately be sent back for another 15 days. It was always cold in the punishment cell, Ovsienko recalled, and prisoners were not allowed out to exercise. If an inmate was taken out to work, he was entitled to hot food, but “without fats and sugar.” If he didn’t work, he received hot food every other day. The rest of the time, he ate bread (450 grams per day), salt, and hot water.

After two or three such punishments, they might send a prisoner to solitary confinement for a year.

After that, the court could impose an additional sentence of several years in prison. "All this is against us, as especially dangerous state criminals, especially dangerous recidivists," Ovsienko said.

A historian from a ‘convict district’

Viktor Shmyrov hadn’t intended to study Soviet repression. His academic interest was medieval Russia. "I was studying the history with the least amount of lies," he explains.

While still a student at Perm State University, Shmyrov was hired to head the museum of local history in Cherdyn, an ancient Ural town in the north of the Perm region. “It’s an exile-convict district. There are dozens of camps all around,” he said.

Shmyrov spent seven years in Cherdyn. Afterwards, he taught and became dean of the history department at the Perm State Pedagogical Institute. In the late 1980s, old friends of Shmyrov’s opened a branch of the human rights group Memorial in Perm. “I helped them however I could, including with archives, and with advice on what they could find and where, since I'm a historian,” he said. He also arranged for them to use the institute's assembly hall for meetings.

In 1992, Shmyrov was asked to help set up a museum at Camp VS-389/35, now known as Perm-35. Since the early 1970s, it had been one of three high-security facilities in the district for political prisoners. After 1991, it remained as a penal institution for criminals. Journalists were eager to visit, and so the head of the Perm Internal Affairs Department proposed opening “a museum of some kind,” Shmyrov said.

"We were given two rooms in the hospital of this camp. We made a small exhibition," he recalled. The artist Rudolf Vedeneyev, who served two years in the camp, made a memorial plaque.

After that, the “memorialists” held a conference near Perm-35, inviting former political prisoners to attend. Someone suggested visiting the two other institutions that made up the so-called Perm “troika” of camps: Perm-36 and Perm-37 (or VS-389/36 and VS-389/37).

Shmyrov was struck by what he saw at Perm-36: "I know what camps from the 1960s and 1970s look like. But here I saw a different zone, archaic barracks. It occurred to me that perhaps they had been standing since the time of the Stalinist Gulag, the one Alexander Solzhenitsyn described. And it's not one or two buildings, but a whole complex!”

He was right.

Correctional labor colony No. 6 in the village of Kuchino was founded 76 years ago. It was a typical gulag zone, of which there were tens of thousands throughout the Soviet Union. Its prisoners were forced to do hard labor, such as felling timber.

The colony was given its new name — VS-389/36, or Perm-36 — in 1972. It also received a new, thoroughly vetted staff, as well as new prisoners — opponents of the Soviet regime, for whom conditions of maximum isolation were created.

The 1953 amnesty, which was declared shortly after Stalin's death and took place against the backdrop of uprisings in the camps, freed more than a million people. However, relatively few political prisoners were released, as the amnesty did not apply to those sentenced to more than five years for “counterrevolutionary crimes.”

In the 1960s, a large number of these prisoners were held in Mordovian political camps. It was easy to smuggle information out of those camps because there were corrupt officials. Concerned that a dissident movement was on the rise, the authorities set up the Perm camps.

During the camps’ existence, 985 prisoners passed through them, Shmyrov says. Most were Ukrainians. Official records list 268 Ukrainian prisoners, more than any other nationality. Additionally, there were another 162 whose nationalities are not specified in available records, but many had Ukrainian surnames.

Repressive policies in Ukraine had been particularly harsh since the early 1970s, says Alexander Daniel, a researcher on the history of dissent in the Soviet Union. While “anti-Sovietists" in Moscow would get in trouble, their Ukrainian counterparts would get stiff sentences for similar activities.

Ukrainians also predominated among the prisoners in the high-security division of Perm-36, which operated from 1980 to 1988. This was where "political repeat offenders" such as Ovsienko were held, as well as those sentenced to death for treason.

Ukrainian prisoners helped smuggle information about human rights violations out of the camps. Writing in fine calligraphy on extra-thin paper, they described searches in their cells to confiscate “extra” warm clothing; lack of ventilation in the workshops; being denied visitors for refusing to speak in Russian rather than their native language; lack of medical care; and illegal detention in isolation cells.

The paper strips were wrapped in special plastic film capsules that were swallowed by prisoners preparing to leave the camp, or by relatives during visits. Information about these violations was published in Russia and Ukraine, and broadcast on Radio Liberty and Voice of America. This was uncomfortable for the Soviet authorities, who had embarked on perestroika reforms. In February 1986, Mikhail Gorbachev even assured the French newspaper “LʼHumanité” that there were no political prisoners in the country.

On Dec. 8, 1987, Ovsienko recalled, “a whole gang of cops” arrived at Perm-36 and moved all the political prisoners to Perm-35.

KGB officers asked the prisoners to write statements that could provide grounds for a pardon. Ovsienko and many others refused, because they did not consider themselves guilty. Nevertheless, he was released in August 1988; the Perm-36 political camp ceased to exist.

But a year later, Ovsienko returned to rebury the bodies of his fellow Ukrainian prisoners Vasily Stus, Alexei Tikhogo, and Yuri Litvin, who were among nine people who had died at the camp. The Ukrainian dissidents who survived the camp were “more fortunate than their predecessors,” Ovsienko said later: “They saw an independent Ukraine.”

Researchers have confirmed that Perm-36 is the only surviving complex of buildings from Stalin's Gulag. It remains almost fully intact, though it’s been damaged by weather and by local residents who scavenged window frames and roof slate for their homes.

“When I realized that I had a rare monument in front of me and that it would disappear in a few years if I didn't take it, everything was decided right away," Shmyrov said.

Shmyrov soon abandoned his doctoral dissertation, his position as dean, and his teaching career. Together with Memorial members and social activists, he created the Memorial Center for the History of Political Repressions at Perm-36 and became its director.

Working with former political prisoners including Ovsienko, Shmyrov documented the crimes of Soviet authorities at the camp. The museum opened in 1995. Shmyro ran the center until it was taken over by Russian authorities 20 years later.

The ‘territory of freedom’

The last time Ovsienko and Shmyrov saw each other was in 2013, at an annual festival at Perm-36 that had become a major attraction in the region since it was first held 2005. "We had a slogan: 'Perm-36 is the territory of freedom,'" Shmyrov says. The program included exhibits, films, concerts, and public discussions on political topics. Speakers included the human rights activist Sergey Kovalev, the opposition leader Boris Nemtsov (who was later murdered), and Russia’s then-acting Commissioner for Human Rights Vladimir Lukin.

Perm Krai authorities initially supported the project. But in 2012, after former Regional Development Minister Viktor Basargin replaced Oleg Chirkunov as governor of the Liberal Party, the festival began to suffer funding cuts and government interference with its programs.

After the destruction of the festival, there was a struggle for the museum. The administration of the governor decided to make it entirely state-run.

In May 2014, the Perm region’s culture minister dismissed the museum’s interim director, who had taken Shmyrov’s place while he underwent heart surgery. After coming home from the hospital, “I found that we no longer had a museum,” Shmyrov recalled.

Changes were made in exhibits. Some were hidden from visitors or altered; a display about Ukrainian prisoners, for example, was changed to accuse them of sympathizing with ultra-right-wing Banderites. There was even some discussion of a display honoring the “effectiveness” of the camp staff, though this has not been done so far. The group Memorial was designated by the government as a “foreign agent,” ending its involvement in the project.

Shmyrov has heard about the changes, though he hasn’t been to the museum since 2014. "It all hurts me. They tell me what they say on the tours. How the tour guide starts giggling,” he says. “People died in this camp from lack of medical care.”

Shmyrov is also concerned about the condition of the buildings. Under his leadership, they were largely restored, but were not finished with plaster. “And they are still standing unplastered,” he said. “Without plaster, they rot.”

Meduza asked the center’s current director, Natalia Semakova, about Shmyrov’s remarks, but had not received an answer at the time of publication.

The start of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine last February shocked Shmyrov. But while he has maintained contact with some former Ukrainian prisoners at the Perm camps, he hasn’t discussed the war with them. “I don’t know what to say. Those trite words: ‘I’m with you’? I’m not with them, they’re being bombed,” he explains. He wrote to Ovsienko but got no reply; mutual friends told him Ovsienko was “very sick.”

Ovsienko, now 73, lives in Kyiv. He has no wife or children. When he was released from prison, he devoted himself to social and political activities and to preserving memory: he wrote about his life and the Ukrainians who died in prison, and collected stories of those who came back alive from the camps and from exile. They are published on the website of an online museum created by the Kharkiv Human Rights Group; Ovsienko is its coordinator.

Ovsienko does not pick up the phone right away. When he does, he complains that he does not feel well, and that his memory is no longer the same. He advises Meduza to look at his past interviews, articles and books. "I think that what should have been written, I have already written," he says.

Ovsienko doesn’t believe he will ever visit the Perm region again. “A lot of good people were left there,” he says.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1937-Mikhail Tukhachevsky

Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky (Russian: Михаил Николаевич Тухачевский, tr.Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevskiy, IPA: [tʊxɐˈtɕefskʲɪj]; 16 February [O.S. 4 February] 1893 – 12 June 1937), nicknamed the Red Napoleon by foreign newspapers, was a Soviet general who was prominent between 1918 and 1937 as a military officer and theoretician.

On June 11, 1937, the Soviet Supreme Court convened a special military tribunal to try Tukhachevsky and eight generals for treason. The trial was dubbed the Case of Trotskyist Anti-Soviet Military Organization. Upon hearing the accusations, Tukhachevsky was heard to say, "I feel I'm dreaming."[35] Most of the judges were also terrified. One was heard to comment, "Tomorrow I'll be put in the same place."

At 11:35 that night, all of the defendants were declared guilty and sentenced to death. Stalin, who was awaiting the verdict with Yezhov, Molotov and Lazar Kaganovich did not even examine the transcripts. He simply said, "Agreed." Within the hour, Tukhachevsky was summoned from his cell by NKVD captain Vasily Blokhin. As Yezhov watched, the former Marshal was shot once in the back of the head.

0 notes