Text

Propelled chiefly by last year’s London production, I have written a (rather) long form piece to do with Rebecca the Musical. Though focusing mainly on this eventual and heavily expectant premiere of the English production of the musical, discussion relates also to the original and other iterations of the show, and musicals more generally, too.

The piece is anchored by the central theme of insatiability while looking in turn at:

the process of tracing the evasive histories of character representations and theatrical productions over many decades – including also flickered and largely forgotten records of the play and opera forms of Rebecca, and the “apparitional”, equivocal lens that queer female sexuality is handled with across large spans of time

decoding evidence of sparse, if periodically rather dire, female queerness in theatrical, musical contexts – guided by the disciples of dykeish dissatisfaction in the musical’s character of Mrs Danvers or the story’s primary author of Daphne du Maurier herself

considering what it means to exist as an audience member responding in situ to (principally female) performers with thrilling voices, both in and outside an auditorium, and the delicate but frequently under-discussed predicament of queer female diva devotion.

Take a look if you're interested!

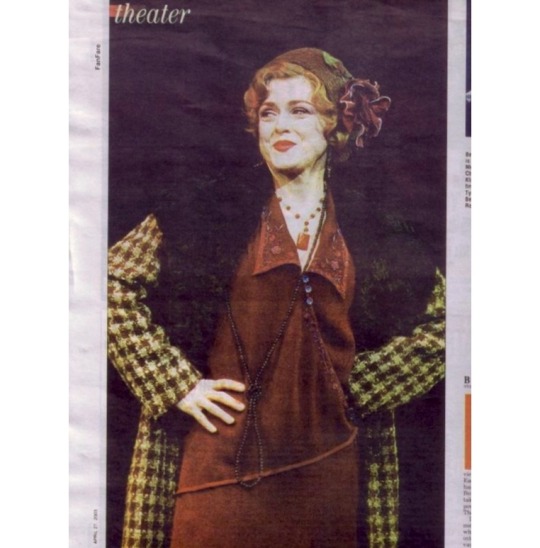

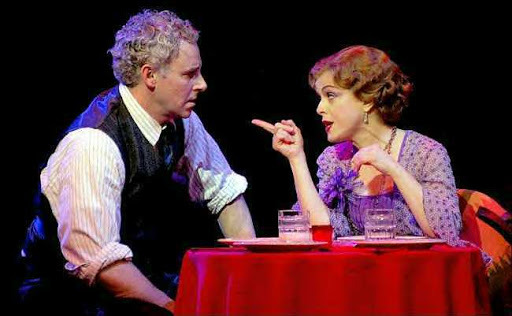

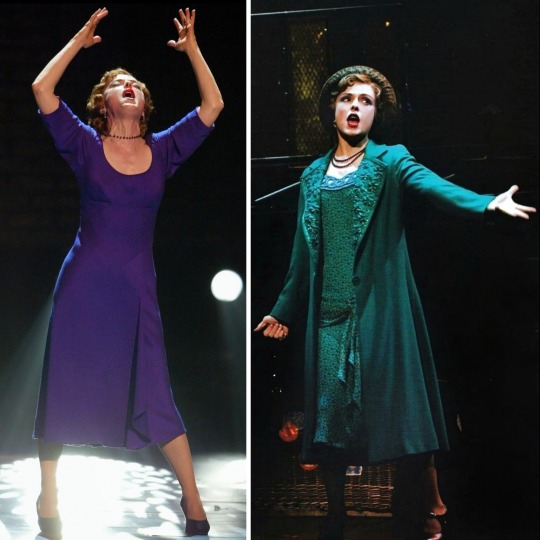

In further expansion of photographic documentation of each of the examined stage-based, theatrical iterations of Rebecca, more images are presented below.

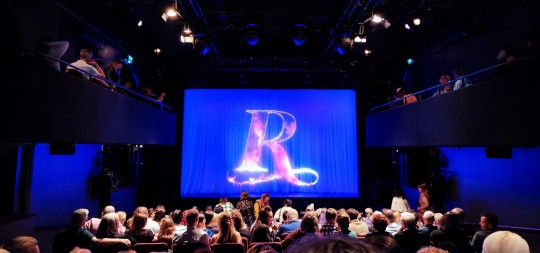

Discussion originates from the existence of the 2023 English premiere production of Rebecca the Musical at the Charing Cross Theatre in London, where cast principals included Kara Lane as Mrs Danvers (alternated by Melanie Bright), Lauren Jones as I (the new Mrs de Winter), and Richard Carson as Maxim. Photos by myself.

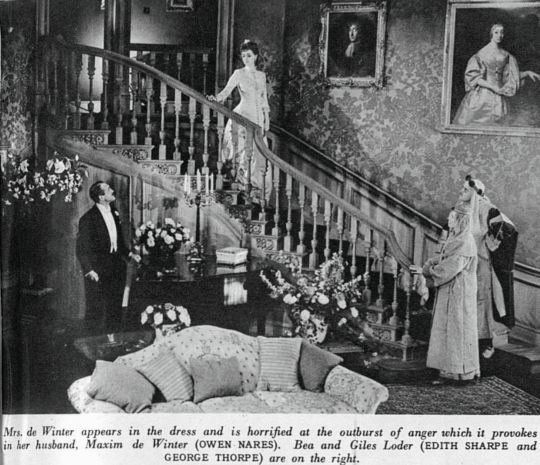

The first stage production of Rebecca arose much earlier, concerning the 1939 play by the same name at the Queen’s Theatre on Shaftesbury Avenue (now The Sondheim Theatre). Daphne du Maurier herself wrote its script. Margaret Rutherford played Mrs Danvers, Celia Johnson was the new Mrs de Winter, Owen Nares appeared as Maxim. The Queen’s Theatre was bombed in 1940 during WWII at the time of Rebecca’s occupancy, becoming the first theatre in London to be hit by a wartime bomb, and bringing to an immediate premature close the show’s successful run - and highlighting earlier associations of this story's connection to tumultuous tales and dramatic events in histories of it's staging, as the attempted primary stagings of the English musical iteration would later return to.

Photos from this first theatrical, London production include those by Angus McBean from a periodical spread entitled ‘Mystery and Murder in Stately Cornish Home - Dramatic Moments of Du Maurier’s “Rebecca.”’, published in The Sketch (vol. 190), May 1940.

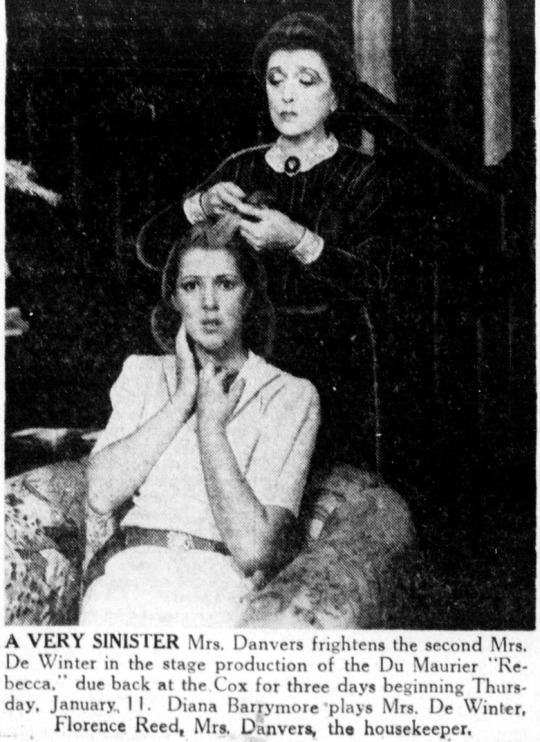

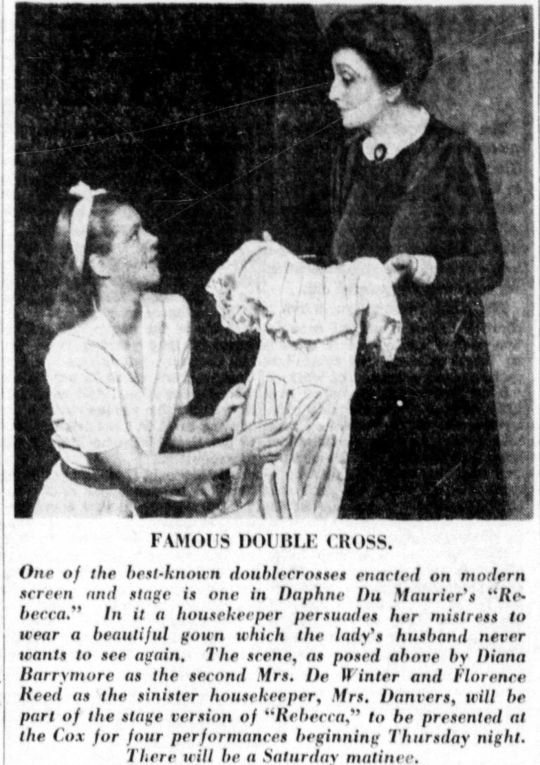

The play also then appeared on the road in America, and subsequently on Broadway in 1945 at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre for a fleeting 20 performances; and of this entity, record remains even more scarce. Cast principals included: Florence Reed (Mrs Danvers), Diana Barrymore (the new Mrs de Winter), Bramwell Fletcher (Maxim).

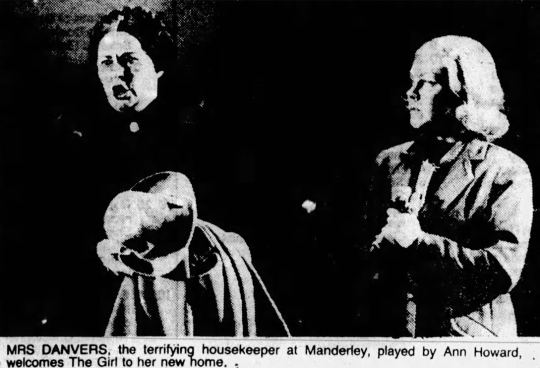

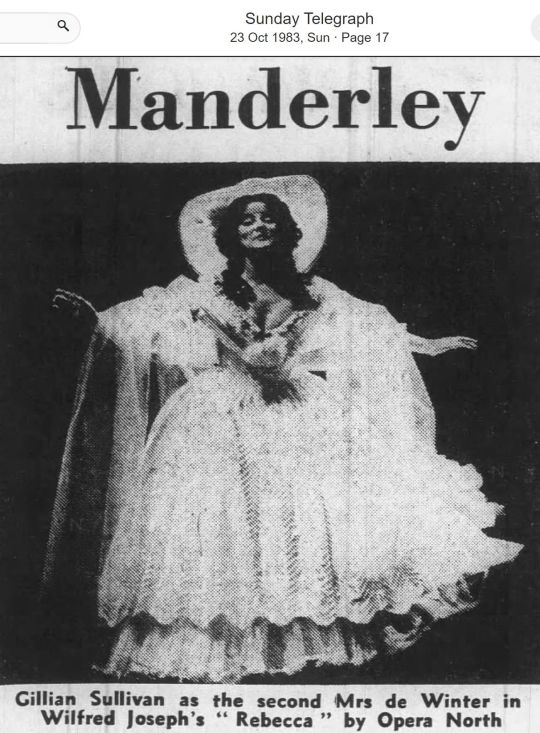

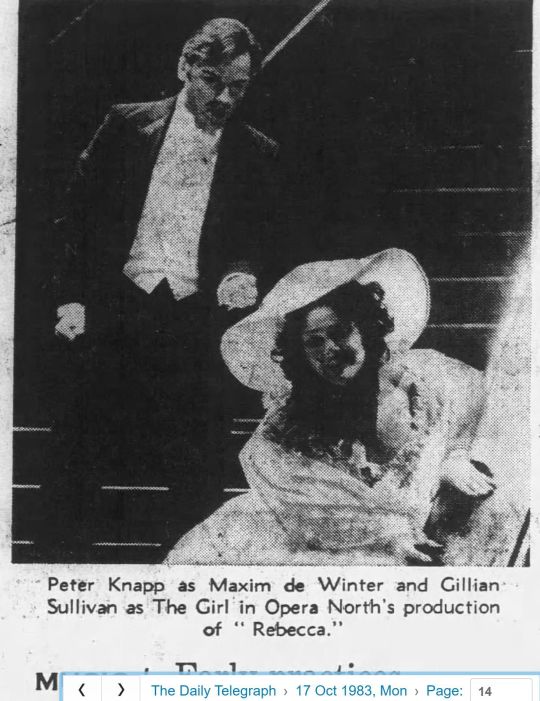

The next and last distinct adaptation of Rebecca to appear on stage before the musical was the 1983 opera production devised for Opera North, with music by Wilfred Josephs and libretto by Edward Marsh. It toured the UK before being revived briefly in 1988 and never seen again. Cast principals included: Ann Howard as Mrs Danvers, with Gillian Sullivan and later Anne Williams-King as the new Mrs de Winter, and Peter Knapp as Maxim.

Finding these few, historic photographs in obscure newspapers or consulting original scripts and librettos, for instance, in libraries and archives during this effortful and active treasure-hunting felt special and rewarding. But possible reconstruction of these stage iterations in the present day is only incompletely possible, because of reduced ease of access to or apparent remaining visceral evidence of a visceral art form.

The frustration in trying to seek out these apparitional traces not only foregrounds the importance of maintaining accessible, comprehensive primary records within the theatre, but mirrors also the act of trying to seek out records of queer female sexuality across history in works of literature, cinema or theatre, as a process typified by a similarly effortful navigation of apparitional erasure. This facet connects with the notion that consideration around Rebecca entangles with a web of insatiability or dykeish dissatisfaction, a web that stretches from this erasure and liminality of representation, to character constructions within the work – including of its infamous housekeeper, Mrs Danvers, to contextual backgrounds like those of the story’s primary author itself, Daphne du Maurier.

The entity of Rebecca, then, across its many themes, productions and decades, is uniquely useful in the way it can in turn encompass and facilitate explorations of these many facets – being capable of simultaneously holding consideration of these expansive webs of documentation, erasure or dykeish dissatisfaction that can be found lurking in historical margins, as well as also the contrasting luminous energy that can be produced in the present in association with the musical, as physical audiences interact with and respond to the material of the show and its performers within theatres in real time. These considerations have transferrable applicability beyond this singular context of this particular show to more general notions of theatrical pieces and the practice of theatregoing, too, as they foreground the question of how audience members respond to, process, and interact with shows; and, as a matter of far less common discussion or scholarly writing on the subject of diva devotion, how female fans specifically navigate the complex predicament of queer, female, performance-driven high regard.

#rebecca the musical#rebecca das musical#rebecca#mrs danvers#ich#the new mrs de winter#daphne du maurier#lonbecca#rebecca london#kara lane#willemijn verkaik#musical theatre#musicals#terry castle#wayne koestenbaum#the apparitional lesbian#theatre

18 notes

·

View notes

Link

This is a link to the first of a four part piece published on https://www.onstageblog.com/ between the 28-30th October 2021 documenting the evidence as to why the producer Garth Drabinsky is an abusive tyrant and should not be allowed to return to Broadway.

The start of the article opens as follows:

The ‘Tyrannical and Abusive’ Garth Drabinsky, and His Attempted Return to Broadway with 'Paradise Square'

Who is Garth Drabinsky, what is Paradise Square, and why should anyone care?

The latter is being heralded as the first new musical to reopen Broadway. It has been described as “one of the most anticipated stage musicals to make it to Broadway since the pandemic began”, and as “set to rival Hamilton’s Broadway success”. It is hurtling along to open in Chicago in a matter of days on November 2nd, before shifting onto Broadway early next year in February.

The former is the attached producer of this show – a convicted felon from Canada, a lauded ex-producing mogul, and a creator of hostile working environments. He, correspondingly, has been described as a “seductive and relentless psychopath”, or as actress Rebecca Caine put it, “Scott Rudin but maple syrup flavoured”. A criminal lawsuit in 1998 characterized that “Drabinsky’s management style was tyrannical and abusive”. It is furthermore well-established that he has historically created and maintained producing environments where he, as reported by The Globe and Mail, “intimidated staff through profanity, abuse, and derision, either directly or by direction of other senior employees who adopted the same approach”.

In short – Garth Drabinsky’s return is a threat, and a direct contradiction to the progressive forward motion to be found currently as some of the world’s most notable theatrical environments emerge from unprecedented periods of dormancy. Cries like “#bringbackbetter” are elsewhere typifying the dominant mentality being striven for in hoping to create safer and more diverse workplaces for returning inhabitants. And, even further, tangible actions and consequences are in fact materializing in response to other publicly raised inequities.

Actors are leaving rather than returning to shows in outrage at current theatrical climates, like with Karen Olivo. Investigations via Actors’ Equity are being triggered into working conditions, like with Nora Schell and Jagged Little Pill. Corrupt or abusive white men who have conventionally yielded power in destructive ways are being removed from their positions of leadership, like with Ethan McSweeney or Scott Rudin.

Drabinsky’s imminent re-emergence on Broadway thus places him at the center of a culture in which he no longer belongs, and positions him as a direct danger to the safety of his employees if this is allowed to happen.

So far nowhere else has it been fully explored why.

The article has a concluding summary that states:

Garth Drabinsky is a historically convicted felon.

Garth Drabinsky is a historically known tyrant who creates unsafe working environments.

Garth Drabinsky has demonstrated A) a lack of evidence of remorse for his indiscretions, B) modern malpractices of finance, and C) sustained proof of the same historic tyrannical, angered, and fear-inducing approaches to work.

Paradise Square is heralded as new, but is in fact deceptively old and weighed down by a long entwinement around Drabinsky’s own sordid past, as well as racially antiquated founding material, and years of convoluted gestation through its discordant creative team.

Paradise Square is heralded as exciting with much potential for making a large cultural impact in tackling big issues, but there is lacking confidence based on Drabinsky’s previous associated works, or early versions of this work, that it will have the tools or competence needed to produce a nuanced examination of these topics.

The current theatrical climate in search of genuine progression, equity, and safety is outwardly incompatible with Drabinsky’s practices and behaviors, or with these inauthentic, improperly considered, or “showboating” manners of storytelling.

The aim of bringing public discourse to such topics is not to enact vengeance for failures of the past. The aim is to raise awareness and create spaces for discourse so as to possibly prevent them from happening again in the future.

Some of the other main points as raised in the article are reprinted below:

[After a run of successes in the ‘90s like Kiss of the Spiderwoman, Parade, and Ragtime,] Drabinsky’s reign as the King of Broadway was finite and his fall from grace inevitable. His company filed for bankruptcy in 1998 when his longstanding spiderweb of defenses broke, leading to revelations that he had stolen an estimated $500 million from investors. He was subsequently convicted of several counts of fraud and forgery and was sentenced to seven years in prison in 2009 for his corrupt, “multi-faceted and pervasive” schemes.

After his release, Drabinsky was also disbarred from practicing law, stripped of his order of Canada, and banned from working in a number of Canadian positions, like running any publicly trading companies.

The man has not produced or been linked to a show on Broadway since 1999.

Paradise Square is not a newly birthed entity, rising brightly out of the troubled waters of pandemia. Instead, it’s the 9-year-old puppet being dragged along in its master’s destructive never-ending quest for a comeback. And moreover, one that was plotted long before anticipation of being able to conveniently attach its storylines of black lives to the topical media bingo headlines of ‘BlackLivesMatter’, or being “particularly resonant now”, or “filled with the hot-button topics”.

Paradise Square first appeared in tangible form Off-Broadway in 2012 under the guise of a show called ‘Hard Times’. By 2015, Drabinsky had acquired its rights after discussions with one of the show’s original book writers, Larry Kirwan.

There’s a deep absurdity to be found in examining some of these timings. Kirwan was invited up to Toronto to meet Drabinsky by a friend “[who’d seen] the show in New York” after 2012. This was no great feat of hospitality, mind. Rather it was a matter of necessity: at this point in time, Drabinsky was not even legally allowed to physically enter America. He was still then a fugitive, hiding in Canada, “under indictment in the United States for fraud”. “If he sets one foot over the borderline, he’ll be clapped in irons,” the New York Post said in 2016.

This status of impending possible further conviction continued until the summer of 2018 when the last remaining criminal charges against him in America were finally dropped – a long two decades after they’d initially begun. This means that for around five years of his association with and work on Paradise Square, Mr. Drabinsky was literally still on the cusp of potentially being sent back to prison for his outstanding crimes.

(On actress Rebecca Caine’s treatment in the Canadian production of The Phantom of the Opera:)

During her time as the show’s principal female lead between 1989-1992, Caine experienced the use of prolonged, excessive, “brutish conduct” and violence on stage from her co-star Colm Wilkinson. This happened in tandem with the management and Mr. Drabinsky’s callous indifference to these matters that enabled the perpetuation of hostile working environments.

Caine spoke up about these harmful and negligent conditions, and the environment of fear she was forced to work in day after day at the time. The result? Drabinsky’s Livent terminated her contract and refused to pay the remaining portion of her salary.

There’s no shortage of supporting evidence for these details, due to the 150-page arbitration report that was generated in consequence of Caine being required to take on Drabinsky’s multi-million-dollar company. This saga formed a highly contentious and drawn-out legal battle in 1992, that was described for its severity and intensity by Canadian Actor’s Equity as strongly “not traditional”.

For all [the] significant damage Caine’s treatment caused her, the arbitrators ultimately found she had essentially done nothing to deserve it. They ruled that “Ms. Caine cannot be held accountable for Mr. Wilkinson’s brutish conduct towards her”, and that the circumstances of Wilkinson’s “excessive roughness…which was abusive in nature…did not justify the premature termination of Ms. Caine’s…contract”. As those involved from positions of managerial power were “either unable or unwilling to deal effectively with Mr. Wilkinson's roughness”, it is clear that the management team, Livent, and Mr. Drabinsky failed Rebecca and grossly endangered her safety.

Caine related that she raised concerns with members of Drabinsky’s management team “repeatedly about Wilkinson’s stage roughness”. Nothing was done. Meanwhile, Drabinsky himself in his status as a veritable “control freak” knew exactly what was going on. “[He] was aware of her grievances, and was meant to air them with Wilkinson.” He did not. Again, nothing was done. What DID he do instead then? He called Rebecca a “c*nt” via her agent, and “told her to get back on stage”.

Unfavorable working environments have also been described in relation to Paradise Square in the present, putting actors again in unsafe or adverse conditions. One example that documents this is an interview on Irish radio station Ceol na nGael in June of 2021 that described how the choreographer “Bill T. Jones is a monster” with “what he was getting the people to do and pushing them”.

[These] patterns of behaviors demonstrated by individuals employed by Drabinsky are concordant with patterns as revealed by Barry Avrich in his 2016 book “Moguls, Monsters and Madmen: An Uncensored Life in Show Business” – and also link to the initial indication of self-perpetuating cycles and cultures of abusive behavior.

Through his multiple decades of first-hand experience of working with and for Mr. Drabinsky, Avrich here uses his unique position to document some of the practices he observed, including experiences of being “forced to deal with Garth’s people”. These employees he describes as “all…suffering from Stockholm Syndrome” as the consequence of being made to regularly endure the behavior of their tyrannical master as a “control freak with a savage temper”. Avrich would say, “Having been beaten and pissed on by Garth, they were eager to beat and piss on everyone else beneath them”.

Garth was known abjectly to not treat his employees well. For instance, in frequent, long, and arduous meetings, “if someone made a mistake, or failed to answer a question, Garth took that person down ruthlessly, not just for that one error, but for every stumble and misdeed in his victim’s employment history”.

Amongst others who faced Drabinsky’s treatment as a “certified bastard and betrayer”, Avrich would affirm “some people left Garth’s employ damaged for life”.

Jon Wilner was one of many who could testify to this. And he did. Once Drabinsky’s respected advertising man, Wilner would report that when Livent went bust, his company was forced to declare bankruptcy too. “My career was cut in half... I had to fire 35 people and shut down a business I worked at for 28 years,” Wilner would say. “And all because of his maniacal ego.”

“There is not a day in my life that I don’t resent what Garth did to me”, he conveyed in 2008.

[Michael] Riedel dedicates considerable space in his 2020 book, ‘Singular Sensation’, to further accounts of Drabinsky’s abusive, violent and alarming behaviors over prolonged periods of time. These involve personal accounts like Drabinsky “pounding [Riedel’s] desk recorder so hard that [his] tape recorder fell off it” during an interview. Or alternatively, via retrospectively collected reports from those who worked with or under him. This included his “bullying” of his accounting department and putting them, “for several years, under intense pressure” while forcedly concocting his fraudulent books.

Drabinsky was one of Livent’s top three executives, and it was these “top executives [who] relied on coercion and intimidation to browbeat their accountants”. If Drabinsky didn’t like something during meetings, he would yell enraged expletives like “This is shit!”, and often target someone, usually a low-level employee, for humiliation. One specific example details how a “[young, female] underling in the marketing department…broke down in tears” when he “lit into” her just “because she didn’t have the answer to one of his questions”.

Evidence of this “brutish working environment at Livent” is further substantiated elsewhere, as in testimony via the company’s then-executive vice president, Robert Webster, in 1999 from an affidavit produced as part of Livent’s lawsuit. Webster details a culture where “bullying and abuse were standard fare”, which “included executives who screamed and swore at staff and employees who were reduced to tears”. He even more damningly reports how this “mistreatment started with the company’s founder” in saying “I had never before experienced anyone with Drabinsky’s abusive and profane management style”.

“Those who did not adhere to these demands were admonished”, Webster said. This left some employees who “felt nauseated by the tension”, some who were “shaking like a leaf” after giving Drabinsky memos, some who were told consistently their “work was of no use to him”, or even one who Drabinsky threatened he “would have to take action” against if his work was deemed lacking or – florally in Drabinsky’s words – if he “wanted to sit in a corner and jerk off instead of servicing [Drabinsky’s] needs”.

Drabinsky would also yell at and harass individuals who were meant to be his equals on creative or authority-based footings. Nancy Coyne, an advertising industry pioneer whom he was approaching to work on Kiss Of The Spiderwoman, recounted how from their very first meeting “he started to yell at and humiliate me”. Lynn Ahrens, as one of the composers of Ragtime, would recall events of him “shouting” at her with belligerent orders like “You will do what I tell you!”. And this was after he had already threatened her: “If you don’t do an amazing job, I’m going to fire you”.

He did indeed cause additional terminations of employment as well as just threatening with them. Before Webster, a previous executive vice president at Livent was Lynda Friendly. She “complained about the theatre impresario’s abusive and destructive behavior” towards her. Drabinsky fired her. Like Rebecca Caine, this presents another case of intense escalations including contract dismissal in the face of reported abuse. Friendly documents taking the matter to the Superior Court in 1997 where she gave evidence of Drabinsky “swearing at her in front of senior staff”. Some of the things Drabinsky yelled included tirades like, “Who the f--- do you think you are to tell me how to address you in my office? I'll do what I want. I run this company”.

But even beyond verbal abuse, Drabinsky wasn’t above physical violence either. Michael Riedel conveyed when one employee made an error regarding a hotel room, “he was so annoyed with his assistant he turned around and slapped him in the face”.

It must be remembered that he pleaded “not guilty” to his original crimes. He couldn’t even then admit to responsibility for his own culpability in breaking the law, instead declaring, “I have complete confidence that we will be vindicated” instead of being sent to jail.

Following his release from prison on parole years later, he gave an in-person talk in Canada in 2013 where he said, “I made serious omissions, mistakes and failings,” and “I am genuinely remorseful for the devastation” caused.

And yet. In his book, Barry Avrich would describe how he’d visited Drabinsky in jail and subsequently would question, “Did he have any remorse or would he express any culpability for what he had done? None that I could see. It was classic Garth. His defense mechanisms were in full operation—poor me, trapped in this bad situation that isn’t my fault”.

Or alternatively, Michael Riedel reported in 2015 after his release that “sources who keep tabs on Drabinsky say he’s unbowed and unashamed”. “He has no guilt,” Riedel recorded an “old confederate” saying, and that still, “he thinks he didn’t do anything wrong, and if the world thinks he did, well, he’s done his time, and now he wants to get back to producing Broadway shows.”

At Drabinsky’s 2013 talk, his behavior also appears concordant with Avrich’s previous characterization of him as being emotionally manipulative and historically wont to covet sympathy. He described the horrors of his time in prison, as with the “murderers, pedophiles, drug dealers, addicts” and how his “life has been shattered”. But he neglects to mention that much of his sentence was in fact spent at the minimum security and quaintly named Beaver Creek establishment in Ontario – “not far from the summer camps he had attended as a boy”. Or alternatively, that he was mostly free on day parole and out of prisons entirely in halfway houses; or that “during weekends, he [spent] time with family at their home and at a cottage”.

In 2017, “he lashed out at Jonathan Tunick, the orchestrator” he’d chosen for his show Sousatzka, when he “wheeled on him during a rehearsal and screamed” or “bellowed” at “full-tilt” – “Why am I paying you all this money?”. Graciela Daniele as Sousatzka’s choreographer would bring up his “fiery temper” as well in 2016, and list amongst some redeeming qualities, that “he has his explosions” still.

Additionally, Drabinsky frequently exhibits an evasiveness and unwillingness to talk about his behaviors regarding financial matters with any clarity.

He cuts any discussion concerning money off with phrases like “I’m just not going to answer any of these questions, or “it’s not relevant”, as exemplified in his TV interview on The Agenda with Steve Paikin in 2016 in relation to Sousatzka.

Is it really not relevant to ask where the money is coming from for a project being helmed by a man who bankrupted a company, stole $500 million, additionally took $4.6 million’s worth in personal kickbacks, and hasn’t really worked since the turn of the century?

As he emerged from jail, it was documented in 2014 that Drabinsky had “received $7 million in outstanding loans from prominent friends “over several years to help cover his legal fees”.

One lawyer, who was owed “more than $61,000 for legal work” done in 2014, started an investigation into Drabinsky’s finances, in escalation of already fruitlessly “pursuing Drabinsky for payment for years”. Only in 2020 were the findings of these inquiries eventually concluded, whereupon it becomes apparent Drabinsky is still trying to exempt himself from standard, legal financial responsibilities. Rather than paying back those he owed, Drabinsky attempted moves like trying to eliminate evidence of a $2.63 million house of his, in transferring its ownership to his wife to put the “property out of reach of his creditors”. However, “the judge declared the ownership transfer void” given that “Mr. Drabinsky offers no other explanation that makes sense”, and the transaction “bore many badges of fraud”.

Illuminating how Drabinsky is still “deeply indebted” and concurrently intertwined with fraudulent practices is just one of the ways of observing how Drabinsky’s ‘changed ways’ and ‘remorseful behaviors’ appear hollow and highly questionable. What alternatively does not appear questionable, is Drabinsky’s clear angling for money and a return to notoriety and Broadway with as much control and power as he can conceivably acquire.

[As with Drabinsky’s previous attempted comeback project of ‘Sousatzka’ in 2016,] Drabinsky is in this same position of having total creative control again on Paradise Square. This does not bode well in theory, nor has it been received well so far in practice. This can be observed in considering elements of reviews from the 2019 staging of the show at Berkeley – “the costliest musical that the nonprofit Berkeley Repertory Theater has ever mounted” to the value of $5.7M – which occurred as the most recent precursor form of the musical before it will be seen imminently in Chicago.

The show was assessed here to be lacking in many key areas – including again both technically, and in its consideration of race. Tellingly, it was said the show “felt more committed to intellectual showboating than satisfying storytelling”. The results of reinterpreting Stephen Foster’s already problematic songs were not viewed as the most successful or even that well-done, instead, seeming like they were tacked on “like a barnacle…lingering from a long-gone Foster-centric” early iteration of the show.

(Stephen Foster was known for Depression-era hits, offensive ‘Minstrel Shows’, and now-perceptibly racist material.)

“The music has no particular fealty to the period”, it was written. Moreover, some of Foster’s songs have been awkwardly reimagined” – like with one now being loftily burdened as “an anthemic fight song”. For another, it was also remarked the creative team achieved “the extraordinary feats of making songs like “Oh, Susanna” less catchy”. Though this may not necessarily be a bad thing here upon closer examination. This is the song, after all, that Foster originally wrote for a “thick dialect [of his] own invention, [with a] second verse, which is never sung today, [that] contains the unforgettable line:

I jump’d aboard the Telegraph and trabbeled down de ribber

De lectrie fluid magnified and kill’d five hundred N***er.”

The piece might have bold storylines lines, such as “a labor strike sowing divisions between Irish and blacks; a deadly draft riot; a pregnancy; a debate over whether Stephen Foster has the right to tell slaves’ and blacks’ stories”. However. “Each of these storylines more declares itself than emerges organically”, and the “characters and situations still feel like cogs in a wheel not sure of its destination”.

In essence, it feels forced and confused. There were conclusions of it being “in need of more soul and fewer concepts”. The piece’s “heartbeat is often difficult to hear through the buzzy crosshatched brainwaves of a creative team that shows signs of internal discord”, resulting in it feeling “less like a genuine collaboration than an oft-passed baton, covered with everyone’s…fingerprints”. Thus it appears not a bold, new progressive endeavor founded on artistic integrity, but rather a belabored, arduous attempt trying to salvage matter out of already racially precarious or antiquated foundations, while its leader with his interests “undoubtedly invested heavily” tangentially chases his comeback.

On paper, the show has two black dramaturgs as well as “Black and Latinx” writers, yes. But it also has Drabinsky, a “monster”, an “assassin”, and a whole host of white creatives. Where does one draw the line on paper to decide if the balance is sufficiently weighed in favor of the optics of progressiveness, equity, and diversity?

Drabinsky is not new to being linked to “musicals that deal with racism in American history”. After all, he does have successful entities like Parade and Ragtime as well as a revival of Show Boat to his name.

But Drabinsky is not the culturally and racially sensitive poster child he would like to have the world believe from linkage to the above shows. One glaring warning concerns that for the opening line of his 2013 talk to herald his release, he had the audacity to appropriate his time in prison as being comparable to the Holocaust, in “[quoting] from Holocaust survivor Elie Weisel on how the duty of those who have survived a great test is to tell the story”.

Another warning example concerns Norm Lewis when he declined Drabinsky’s ardent pursuits for him to feature in the national tour of Ragtime – as Eddie Shapiro recounted in his 2021 book “A Wonderful Guy”. Drabinsky then raged, “Who the f*ck does Norm Lewis think he is? Doesn’t he know that I'm the most significant producer on Broadway?... Doesn’t he know what I've done for blacks?”.

Thus there is a warning before current readers get beguiled by ambitious lines in new articles on Paradise Square promising notions of great success, advocacy, and diversity. It must first be considered more carefully as to Drabinsky’s own fundamentally exposing beliefs, words, and actions, and the way in which these same elements have been handled in his two (and only) previous creative attempts in the last two decades.

It should be finally highlighted that opportunities on Broadway are finite and second chances for those exhibiting or having previously exhibited evil or intensely problematic behaviors are not mandatory. There are, in fact, other options.

A New York Times piece last summer by Michael Paulson entitled “Black Plays Are Knocking on Broadway’s Door. Will It Open?” features musings from many notable voices following Paulson’s opening declarative of “Calls for diversity grow louder”. Among them is playwright Jocelyn Bioh. “I don’t know how to solve the diversity issue on Broadway,” Bioh said, “other than calling attention to it, and cultivating a generation of producers who are not afraid.”

This seems reasonable. Perhaps her requirement could be modified slightly: there should be a generation of producers who are neither afraid, but nor do they inspire fear.

Garth Drabinsky does not fit that bill.

If THIS is the man – a known abusive tyrant, volatile felon, and remorseless manipulator who is still demonstrating dangerously unscrupulous financial, behavioral and creative practices – who is Broadway’s literal first choice to reopen the very first new work in the world’s most prominent theatre scene, we are in trouble.

#Garth Drabinsky#broadway#producer#theatre#musicaltheater#hamilton#broadway musicals#rebecca caine#the phantom of the opera#christine daae#broadway show#broadway musical#hamilton broadway#theater#paradise square#chicago

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Carousel at Regent’s Park to the rest of The Great White Way

What IS worth the use of wond’rin’ about as theatre returns in 2021 and beyond?

Seeing the new production of Carousel at Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre in London this summer has prompted me to ask some challenging questions, both of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s much beloved Golden Age classic itself, and also more widely as to the surrounding theatrical climate as theatre returns in 2021 after this protracted period of absence.

What shows are we staging, and why? How do we go about staging these shows or revivals? And who is responsible for staging them? – to list a few.

Some theatregoers are praising the joyous return to the escapism of classic musicals after such a long period of hardship. And some are banging on doors demanding change and betterment. Considering this production of Carousel and how much alteration has been done to a classic musical in this modern age speaks more broadly to the degree of revision accepted as being required as productions begin to return. Closer and more detailed examination of this new production might well raise more questions than there are answers for. But they are questions and aspects that are potentially worthy, or necessary, of examining nonetheless.

Ultimately, the inescapable verdict with this starting example is that a Golden Age musical centring on domestic abuse is unavoidably on very precarious ground in this modern climate, 75 years after it was written. And that’s even before you consider trying to stage it as one of the first shows emerging from a pandemic that has foregrounded a rise in domestic abuse and violence against women during its last two years.

Clearly it would be foolish to expect current audiences to tolerate being made to unironically swallow infamous lines, like “He hit me, mother, he hit me hard, but it didn't hurt – it felt like a kiss”. Not least while they’re all sat with programmes on their laps that brazenly open with a two-page spread addressing the “epidemic within the pandemic” on domestic violence abuse crimes.

So, much retooling has been done to the exposed story of a problematic and abusive relationship in attempts at countering some of these issues – as one of the many revisions that has occurred in trying to ‘update’ this production for more modern audiences.

The show’s handling of Billy Bigelow’s character as it’s abusive male protagonist renders him no longer completely repulsive for his actions or attitudes. He is denied upwards ascendency to some heavenly realm at the beginning or the chance to return and perpetuate the same violence with his daughter and the end. Moreover, it is female not male voices that now reckon with his judgement in purgatory, and the infamous and problematic lines regarding Julie and Louise’s exchange on domestic violence are quietly eliminated. As such, Billy is not allowed redemption in spite of his sins, and the women glean a more fortified and less meek presence.

But the show potentially takes out more than it adds in these changes, and loses some dimension. It seems it is aware of itself as being a show about domestic abuse, but it doesn’t really seem to have anything other to say about it than: “it exists”. Billy is also denied any chance of reflection to either open or close the show, which means he doesn’t get the chance to exhibit any trace of genuine familial care and concern for the fate of his wife and child. This is a change that noticeably causes the show to lose some of its impact, as he thus appears entirely unlikeable and there’s no longer any reason to care for him in the first place.

The new alterations are wise. But they're not faultless.

Other changes have been made to ‘modernise’ the show and make it feel at home in the 21st century – especially to the sound, orchestrations and appearance of the production – which also foregrounds the notion of examining how one constructs a revival.

Tom Deering as the show’s orchestrator illustrated in a podcast some of the primary rationality and justifications for these logistical alterations, like that they “were being driven by dramatic choices and the philosophical change in location and time”.

This referred-to “change” concerns the setting of the production being moved from 1873–1888 in sunny and American New-England, to approximately the 1960s or 70s in a “coastal town in the north of England”. This lends the intention of a more gritty, industrial, and “post-war communal feel” to the show and has a substantial impact.

For one, the piece has been fairly radically reorchestrated. Gone are familiar elements like lush string sections, as an example. In their place attempting to provide corresponding tones are foreign and strange instruments like glass harmonicas and electric guitars. Changes like these are novel and commendable for not simply resorting to synthetic sampling, and credibly reasoned in relation to Deering’s motivations for wanting to “try to imagine a musical palette that felt suitable for this radically reimagined production”. Even so. That doesn’t stop them from feeling audibly jarring at times, at least at a first listen. Unless one is already familiar with matters like versions of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ with opening strains played on electric guitar, that is.

The justification of the altered setting also drives the change in vocal sound and style. Primarily, many of the keys have been dropped. It is possible to understand the reasoning that soaring, pristine, received-pronunciation vibrato does not apt characterisation for a lower working-class Northerner make. This along with rationality from Deering that the piece was written 75 years ago, indicating that the “relationship between singing voice and speaking voice has changed during that time – as have ladies’ voices dropped significantly”, explains the motivation for lowering female vocal keys. Deering also states the point that large contrasts between spoken dialect and sung portions are less accessible to audience members; and as such, reducing the difference in these transitions reduces the “distance between the audience, particularly a younger audience, and the story itself” in order make transitions “easier” and more “accessible”.

This speaks more broadly to the current trends in modern musical theatre writing, concerning the disappearance of the pure soprano sound, vocal homogenisation, and a reliance on straight tones and belting. Some may wish this wasn’t the case, and counter that line of reasoning in thinking that in fact an audience is still capable of appreciating that a piece can be accepted and can carry authentic emotional sentiment even if it appears a notable contrast in register from spoken sections. The manners of these changes in such a revival as this may engender an unfortunate sense of disappointment, at it is predominantly in these classic Golden Age scores that the dwindling upper octaves of an authentic soprano sound still get the rare chance to be heard nowadays.

In a similar vein as above, arguably if perfect polished RP creates a level of unreal artifice, so too do manicured, uniform accents apparently. There is no enforced conformation to a standardised regional dialect here. Instead, the production has cast members all keep their own varied, regional British accents. So while the show is meant to be set somewhere in the north of England (and there are northerners), there are also Welsh or Cockney or London-ish or more central tones in there too.

The desire for this was to scrape “away another layer of artifice, lending an authentic weight”.

This change does have some benefits or justifications of enabling the maintenance of the heterogeneity and diversity within the cast members as seen with respect to the actors here themselves. But it also somewhat causes a lack in central coherence and lessens the impact of the piece. Here, de-homogenisation for inclusivity’s sake appears to counter the actual intention or point of the show in the first place, in interfering with one of its central themes of community. The actors appear less as united characters, and more as, well, actors. Or themselves. As a collective group, the sound no longer reflects what the dialects of a community of working-class people all in a similar geographical area would sound like. Instead, it feels physically non-specific and ungrounded, as if an assortment of people from all over the UK have been banded together for some indiscriminate reason. Crucially, the people on stage are no longer a unified, tight-knit community, in a tangible location, of similar socio-economic statuses, common histories, and shared professions in the same place by necessity not choice – as is integral to the show’s basis.

This notion of modern changes to a show conflicting with the show itself is not a new notion, and it does demand confrontation and raise queries of the impacts to the technical alterations in ‘updating’ beloved or fondly nostalgic musicals.

In a point that feels somewhat subversive to mention, qualms were raised in earlier notable revivals of Carousel decades ago – with the specifics of methods to do with enacting modernisation via the hitherto novel “use of multiracial casting”. Having black actors like Clive Rowe play Enoch Snow in the original 1992 London revival, or Audra McDonald as Carrie and Shirley Verrett as Nettie in the subsequent 1994 Broadway transfer, for example, forces reckoning of whether colour is intended to be ‘seen’, or just blindly overlooked. Simply casting the most talented actors fits with the latter, and should not be dismissed as valid casting practice – lest there be no evolution ever of diversity in historically write-centric shows. But the former, if the differences of race are to be actually acknowledged, necessitates comprehension of a 19th century New England town that can supposedly tolerate at least some degree of being “liberal and liberating”. According to John Simon of New York Magazine in 1994, this arguably “militates against the meaning of the work”, in reference to the story’s dependence on insular, old-fashioned, and intolerant attitudes. Simon said, “There was certainly a case to be made that if the townsfolk were so otherwise enlightened, then why did they ostracize innocent Louise, who wasn’t even born when Billy attempted his botched robbery?”.

It’s a complex issue. And modernisation or increased diversity itself is not the problem – seldom is it not desired or necessary. But it’s a matter hard to reconcile if it impairs any of the show’s core elements or its logic.

As a corollary, one could cite Marianne Elliott’s new and muchly hyped production of Company for evidence of newly updated staging features in further conflicts against impacts of original source material. There’s much to be gained in this new production – like elevated queerness or the apparent increased pertinence of discussion of society’s perspectives on a female, instead of male, bachelor ageing with her ticking biological clock. But there’s a lot lost too.

An important example concerns the switch made to change Amy to Jamie. ‘Getting Married Today’ turns now into a hypochondriacally pattered aria by a stereotypically dramatic gay male in little more than a fleeting, anguished cold-feet spiral. It is no longer also a woman questioning the bedrock of the institution of antiquated heterosexual marriage, built upon centuries of historic female subservience, oppression, violence and even murder at the hands of their domineering male counterparts.

Amy’s original exclamations as to how Paul will “want to kill me, which he should,” or her “floating in the Hudson”, or dying “like Eliza on the ice” (in allusion to Uncle Tom’s Cabin with the young girl fleeting from her male captor), may appear flippant and humorous in the song. And sung by a male – that is when they’re not removed – they primarily appear as simple hyperbole. But as long as America remains a place whereby “four women are murdered every day in this country by a male partner” (as Heidi Schreck cites in her play, What the Constitution Means to Me), the original implications remain unignorably alarming.

The song thus carries intrinsic weight when sung by a woman that it cannot gain back in this new context – subsequently diluting an element of the musical’s original impact.

None of this is to say all methods of introducing change revivals and attempting to “re-invent” are bad, however. For instance, Bill Rauch’s recent revival of Oklahoma! (as another Rodgers and Hammerstein ‘classic’) performed in Oregon in 2018, also featured gender flipped characters, an abundances of queerness, as well as considerable racial diversity. And it was heralded as both logical and a triumph, or “natural and organic” and “beautiful and poignant”. Such positive sentiments were seen too for the “revolutionary” 2019 Broadway revival.

Even closer to home, people had been clamouring for change and revisional updates to Carousel itself as early as the very year it was created in 1945. The piece exhibits non-trivial similarities to the creative duo’s previous work with Oklahoma!, and it was reasoned this “formula was becoming a bit monotonous” – as too “were [Agnes] De Mille’s ballets” , which were appreciably abundant on Broadway in the ‘40s and ‘50s. By the time the memorable London transfer arrived in New York in 1994, it was decried it was “nice to finally see a Carousel free of Agnes de Mille’s overly familiar choreography”. The novel changes here to Louise’s ballet in this new Regent’s Park revival through Drew McOnie’s choreography were seen as a success and favourably received, in making the production “come alive”. At this point in the second act for the dance sequence, towering poles appear on stage to emulate prison bars, the pace of the stage revolve increases, and a vividly sinister male influence becomes evident through their presence and visceral movements. These elements serve to compound a sense of frenzied, building anxiety and cyclical inevitability of a woman once again being trapped in a repeating pattern of being mistreated by men. Consequently here, the show’s primary themes are sustained, if not even further enhanced.

Change is necessary in theatre in order to prevent the stagnation, irrelevance, or outdatedness of staging shows from decades or even centuries ago. It has to be questioned how new revivals can be staged today before creating them, otherwise the risk is high of them becoming incompatible with modern audiences against their precursors as written in entirely different cultural and historic environments.

Some of the specific technicalities of attempted methods of modernisation will be perceived to work. Some will not. In all likelihood, you might not know which is which until they are attempted.

Because of this, it seems important to indicate that change and alteration with the aim of innovation should not be discouraged for creatives within theatrical realms, just on the basis that not everything tried comes off as ‘successful’.

As to this new production of Carousel, one review as written in the i Newspaper by Sam Marlowe puts it just about as well as I can think to put it to conclude consideration of it: “This is an admirably gutsy approach to a deeply flawed classic”.

Many of the modifications in this “tough radical reinterpretation”, as put together by an assiduous creative team, have been made with good intentions, after being substantially thought-through, and executed within the possible logistical parameters afforded.

It’s far from perfect, but appreciably it still deserves credit for trying. And indeed, this classic is deeply flawed.

Suggesting we ‘cancel’ Rodgers and Hammerstein is far from the aim. But it is important to recognise the show itself does have some inherent flaws, and to accept that there might be a limit to how much it can be expected to achieve via alterations to stagings while modernising a show – without completely rewriting the original.

A recently published article published in The Telegraph, entitled “Can the cancel mob please leave our classic musicals alone?”, reasons against this line of thinking. The point of quoting South Pacific and ‘You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught’ as evidence that Rodgers and Hammerstein were “not reactionary dinosaurs whose work should be immediately cancelled” does work on some grounds. It proves an understanding of racial prejudice, yes. But it does not absolve them of all sins forever, particularly female-related ones.

Potentially, irrespective of how you orchestrate it, ‘What’s the Use of Wond’rin’’, for example, is still via its lyrics at its core a deeply antiquated and misogynistic song that displays a complete disregard for women and a lack of understanding of writing for their sex, given the presentation as making it permissible to accept and be content with such violent and abusive male treatment.

Being based on the dark and heavy 1909 play Liliom by Ferenc Molnar, the subject matter of Carousel to begin with is not light, joyful fare. Nor that obviously ripe for musicalisation. It’s interesting to note that rather than Rodgers and Hammerstein, Kurt Weill was among those initially considered to compose the musical adaptation, before being rejected by Molnar. Known far more strongly for dark, brooding, biting works, the German-born composer would certainly have provided an interesting and likely very different version of ‘Carousel’ – in contrast to the duo remembered well for their oft sentimentally soaring ballads. That being said, we can’t in fact reauthor original works.

We can’t alter the original creative teams for shows written in different centuries. But we can, however, certainly question the identities, motivations and behaviours of those involved with staging and creating shows today.

On one hand, there is demonstrably still popular demand amongst mainstream audiences for simple escapism and even ‘classic’ old musicals – the London revival of Cole Porter’s 1934 production of Anything Goes grossed over £1 million in its first week alone, even despite old videos depicting racial insensitivity from its leading lady surfacing in the weeks closely pre-dating its opening night.

But on the other hand, there are other voices also out there ill-content to simply sit back and watch as further injustices unfold. There are voices demanding theatre-based justice. Demanding more progressive and diverse shows, creative teams and casts. More inclusivity and safety for employees. More accountability to be faced for those with power who get control over decisions being made, especially when that power is being abused. And more attention being raised on matters of previous indiscretions and malpractices in the hopes of preventing their recurrence in the future.

The public statements made by Karen Olivo (i.e. “Building a better industry is more important than putting money in my pockets.”), as well as multiple conversations being had around the controversial Broadway production of Jagged Little Pill over workplace diversity and safety, are matters that could be singled out as leading, current examples addressing the inequities or lack of safety in the theatre industry, and vocally raising support or action for “bringing Broadway back better”.

Furthermore, there is justified call for the takedown or removal especially of corrupt or abusive white men in leadership positions who have conventionally yielded power in destructive ways.

February saw the resignation of Ethan McSweeny from the American Shakespeare Company, where he had presided as artistic director since 2018. This came following the review of a 15-page report submitted to the theatre’s board as put together by 52 members of the company that delivered documentation of “a pattern of abusive, manipulative, and dangerous behavior, actions, and speech on McSweeny’s part”.

And more recently, reports of mega-mogul producer Scott Rudin’s own abuse, violence and bullying started coming to light from this April in The Hollywood Reporter. These revelations were subsequently met with galvanising public outcry far across the theatre realm, and Rudin was perceptibly dethroned from his positions of power and the shows he was set to be producing.

These examples appear to display constituents of success and progress for the theatre community. But they are not exhaustive or complete.

There’s another name to reckon with who still threatens the safety of employees in the theatre in light of upcoming projects: Garth Drabinsky.

Some context on this Canadian producer who has flown relatively under the radar of late. Drabinsky rose to fame and prominence in the ‘90s, with hits like the landmark Toronto production of The Phantom of the Opera, before dominating Broadway with a run of successes like Kiss of the Spiderwoman, Parade, Ragtime, and Fosse. His reign was finite, however, and his fall from grace inevitable when he was later sent to prison for fraud and forgery.

At the beginning of summer when researching for another project, I coincidentally stumbled upon some of the details to do Drabinsky’s sordid past. I was shocked. Good riddance, I thought.

One can only imagine then how much more shocked I was in the very same night to read an announcement heralding for Drabinsky’s upcoming comeback. This man is being given free reign to helm and produce what is being publicised as the first new musical to reopen Broadway in 2022 – Paradise Square. This should not happen.

In addition to considerable criminal conduct, this man (like Scott Rudin) has been demonstrated to create hostile working environments that endanger people in his orbit.

“Scott Rudin but maple syrup flavoured,” opera and musical theatre performer Rebecca Caine would quip.

And Rebecca Caine would know.

Prompted by the threat of this upcoming ‘comeback’, Rebecca has been sharing documented evidence over the summer from the harrowing events she experienced as Christine for multiple years in Drabinsky’s Canadian production of The Phantom of the Opera.

During her time as the show’s principal female lead between 1989-1992, Rebecca faced the mercy of prolonged, excessive, “brutish conduct” and violence on stage from her male co-star. She did not receive compassion or support in response to these events as she tried to speak out about them. Instead, she was dismissed by Drabinsky and his production team, threatened with intimidation tactics, victim blamed, mocked or ultimately fired and denied payment of her salary. Drabinsky’s own actions created a callous disregard for her safety which subsequently led to acute and permanently damaging physical injury, as well as prolonged mental trauma.

In addition to these historical details of his negligent and abuse-enabling practices, Drabinsky now out of prison and as recently as the last few years has demonstrated a lack of remorse, continued disreputable accounting practices, and a maintenance of his same volatile temper as previously.

Yet for all of this, he is seemingly being given carte blanche to return. He is set to open his new musical in Chicago from November, or on Broadway next February with so far barely as much public resistance as a slightly raised eyebrow. Even reputable and influential publications like The New York Times have yet to cover matters in full enough historied detail other than to speculate whether this “comeback bid by a scandal-scarred producer” will be successful or not.

This man’s crimes are more serious than the capacity to produce a bad show. He’s more dangerous than that. Watch this space for a full presentation of all of Drabinsky’s legal and moral crimes throughout the last three decades that I have been putting together and hope to be able to put up soon as to illustrate why this man should not be any more considered a viable producer. Simply put for now, Garth Drabinsky should not be at the top of the tree to pick from in selecting new producers to award the privilege and responsibility of staging the first new shows as we emerge from this period of dormancy and ostensible reflection.

Carousel was probably not the best choice for a production to have been staged at this point in time. Even if all involved did try very hard to make it. That decision cannot be reversed, but we can turn the focus of the questions it raised to broader angles and future pieces of theatre.

Like has been mentioned, we can't rewrite the past. We can however try to make better decisions for the future while we still have the capacity to exert an influence in shaping it.

Before new works are put up going forward, we both can and should ask, “is this thing the best piece, made in the best technically relevant style, with the best people behind it, to be staging right now?”

It is these kinds of questions that we must continually remind ourselves to ask as theatre continues to return, if we are to stand any chance of returning with a theatrical environment that is not just enjoyable for audiences, but enjoyable, safe and equitable for all.

#broadway#musical theatre#theatre#new york#musicals#Carousel#rodgers and hammerstein#regents park#regents park open air theatre#Scott Rudin#Garth Drabinsky#Ethan McSweeny#Rebecca Caine#company Broadway#Company#Stephen Sondheim#sondheim#bring back broadway better#London

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Who are you? Where do you get your information and content from?

I'll likely delete this at some point before my next post as I'd ideally like the only main posts on here to be the long text pieces, but I hope whoever's asked sees it before then.

I'm just someone who likes theatre and theatre history a lot and writing a fair bit too! Most of my information primarily comes from archived newspaper articles. But also other sources too like books, podcasts, video/radio interviews etc etc... Essentially - have no fear that I'm simply making all of this up! I'm not. It's all methodically researched, documented and planned before it then becomes 'content', as such.

My first post on costume design on here gives an indication of my sources in that instance, and while I might not cite all my references for the dominant majority of my pieces, if anyone has any specific questions as to the origins of certain quotes or bits of information, just message me and I can certainly provide you with their sources.

One piece that I'm drafting at the moment, if it ever sees the light of day, does actually have a documented references list. And it's currently 58 items long. That's the final version of what was something like 600 articles and 4 books plus other podcasts and videos and such that were read or looked through in the preparation of collecting the information and shaping the content in the first place.

Hope that helps!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michael Riedel vs Bernadette Peters – the Broadway Battle of 2003 and beyond

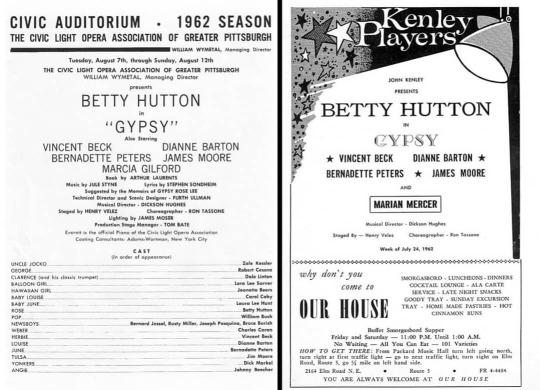

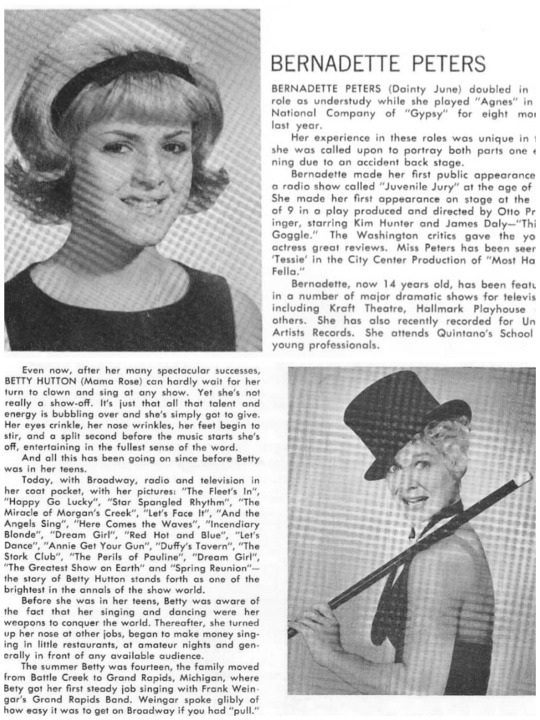

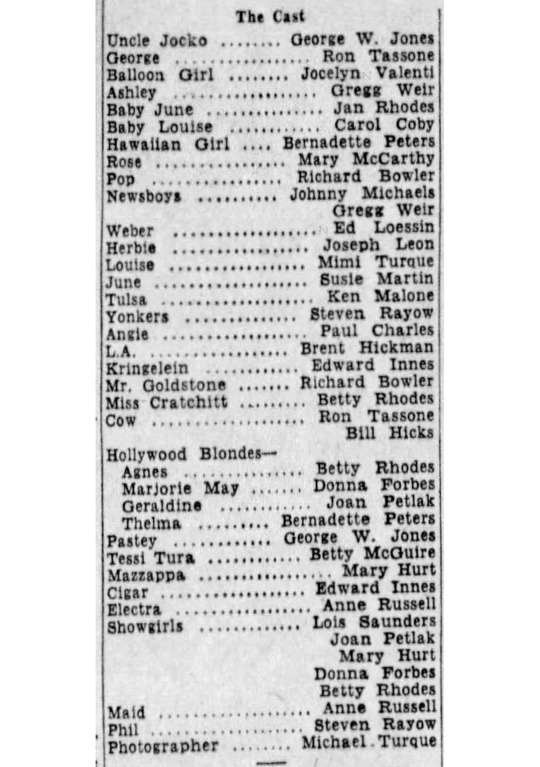

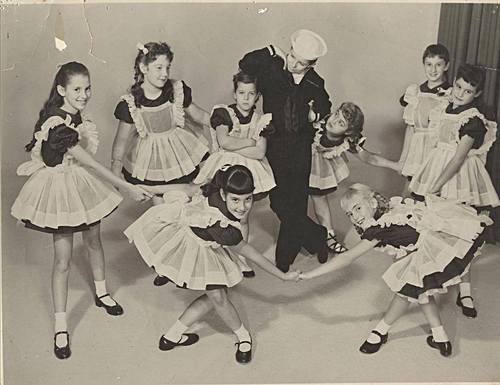

My previous piece gives a fairly comprehensive look at Bernadette and Gypsy through the ages; though there is at least one aspect of the 2003 revival that warrants further discussion:

Namely, Michael Riedel.

Today’s essay question then: “Riedel – gossip columnist extraordinaire, the “Butcher of Broadway”, spited male vindictive over not getting a lunch date with Bernadette Peters, or puppet-like mouthpiece of theatre’s shadowed elite? Discuss.”

It’s matter retrievable in print, or even kept alive in apocryphal memory throughout the theatre community to this day that Riedel was responsible for a campaign of unrelenting and caustic defamation against Bernadette as Rose in Gypsy around the 2003 season.

While “tabloids may [have been] sniping and the Internet chat rooms chirping”, when looking back at the minutiae, none were more vocal, prolific or influential in colouring early judgment than the “chief vulture [of] Mr. Riedel, who had written a string of vitriolic columns in which he said from the start that Ms. Peters was miscast”.

He continued to find other complaints and regularly attack her in print over an extended period of time.

Why? We’ll get there. There are a few theories to suggest. Firstly, how and what.

Primary to establish is that it perhaps would be foolish to expect anything else of Riedel.

Also an author and radio and TV show host, Riedel is best known as the “vituperative and compulsively readable” theatre columnist at The New York Post.

He’s a man who thrives on controversy, decrying: “Gossip is life!”

The man who says, “I’m a wimp when it comes to physical violence, but give me a keyboard and I’ll kill ya.”

“Inflicting pain, for him, is a jokey thing. ‘Michael has this cruel streak and a lack of empathy,’ says Susan Haskins, his close friend and co-host.”

And inflicting pain is what he did with Bernadette, in a saga that has become one of the most talked about and enduring moments of his career.

From the beginning, then.

Riedel started work at The Post in 1998.

His first words on Bernadette? “Oddly miscast in the Ethel Merman role,” in August of that year on Annie Get Your Gun. It was a sentiment he would carry across to his second mention six months later (“a seemingly odd choice to play the robust Annie Oakley”), and also across to the heart of his vitriolic coverage on her next Merman role in Gypsy.

Negative coverage on Bernadette in Gypsy started in August 2002 when Riedel discussed the search for trying to find a new American producer for the show. It had initially been reported in late 2000 that a Gypsy revival with Bernadette was planned for London, before it was to transfer to Broadway. To begin with, Arthur Laurents was “eager to do Gypsy in London because it hadn't been seen in the West End since 1973”, and he “wanted to repeat [the] dreamlike triumph” he said Angela Lansbury’s production had been. But economic matters prevented this original plan, leaving the team looking for new producers in the US. Riedel suggested that Fran and Barry Wiessler step up as, “after all, they managed to sell the hell out of "Annie Get Your Gun," in which Peters…was also woefully miscast.”

He also quipped: “Industry joke: "Bernadette Peters in 'Gypsy'? Isn't she a little old to be playing Baby June?”, calling her “cutesy Peters” and again a “kewpie doll”.

Bernadette here seen side by side with the actual Baby June of the 2003 production – Kate Reinders.

Other publications to this point had discussed her “unusual” casting. Which was fairly self-evident. In contrast to being a surprising revelation that Bernadette Peters was not, in fact, Ethel Merman, this had been the intention from the start. Librettist Arthur “Laurents – whose idea it was to hire her – [said] going against type is exactly the point,” and Sam Mendes, as director, qualified “the tradition of battle axes in that role has been explored”.

It was Riedel who was the first to shift the focus from the obvious point that she was ‘differently cast’, to instead attach the negative prefix and intone that she was actually ‘MIS’ cast. According to him then, she was unsuitable, and would be unable to “carry the show, dramatically or vocally”. All before she had so much as sung a note or donned a stitch of her costume.

So no, it wasn’t then “the perception, widely held within the theater industry,” as he presented it, “that Peters is woefully miscast as Mama Rose”.

It was Riedel’s perception. And he took it, and ran with it, along with whatever else he could throw into the mix to drag both her and the show down for the next two years.

As to another indication of how one single columnist can influence opinion and warp wider perception, just look to Riedel’s assessment of the show’s first preview. It is typically known as Riedel’s forte to “[break] with Broadway convention, [where] he attends the first night of previews, and reports on the problems…before the critics have their say”. This gives him “clout” by way of mining “terrain that goes relatively uncovered elsewhere”, and it means subsequent journals are frequently looking to him from whom to take their lead – and quotes.

At Gypsy’s opening preview then, he reported visions of “Arthur Laurents [charging] up the aisle…on fire”, loudly and vocally expressing his dissatisfaction with the show as he then “read Fox [a producer] the riot act”. Despite the fact that this was “not true, according to Laurents,” the damage was already done, with the sentiment of trouble and tension being subsequently reprinted and distributed out to the public across many a regional paper.

News travels fast, bad news travels faster.

And news can be created at an ample rate, when in possession of one’s own regular periodical column. This recurring domain allowed plentiful opportunity for attack on Bernadette and Gypsy, and Riedel “began devoting nearly every column to the subject,” which amounted to weekly or even more frequent references.

As the show progressed beyond its first preview, Riedel brought in the next aspects of his smear-campaign – assailing Bernadette for missing performances through illness and accusing Ben Brantley, who reviewed the show positively in The New York Times, of unfair favouritism and “hyperbolic spin”.

The issue is not that Bernadette was not in fact ill or missing performances. She was. She had a diagnosis at first of “a cold and vocal strain”, that then progressed more seriously to a “respiratory infection” the following week, and was “told by her doctors that she needs to rest”. So rest she did.

The issue is the way in which Riedel depicted the situation and her absences via hyperbole and “insinuating she was shirking” responsibility. He went further than continual, repeated mentions and cruel article titles like “wilted Rose”, or “sick Rose losing bloom”, or “beloved but - ahem-cough-cough-ahem - vocally challenged and miscast star”. He went as far as the sensationalist and degrading action of putting “Peters' face on the side of a milk carton, the kind of advertisement typically used to recover lost children,” and asking readers to look out for “bee-stung lips, [a] high-pitched voice, [and a] kewpie doll figure”, who “may be clutching a box of tissues and a love letter from Ben Brantley”.

It was quantified in May of 2003 after the show had officially opened, that “out of the 39 performances "Gypsy" has played so far, [Bernadette] has missed six – an absence rate of 15 percent.”

As an interesting comparison, it was reported in The Times in February 2002 that “‘The Producers' stars Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick have performed together only eight times in last 43 performances due to scheduling problems and health concerns,” – an absence rate of 81%.

Did Riedel have anything nearly as ardent to say about the main male stars of the previous season’s hit missing such a rate of performances? Of course not.

Riedel arguably has a disproportionate rate for criticising female divas.

One need only heed his recommendations that certain women check into his illuminatingly named “Rosie's Rest Home for Broadway Divas.” Divos need not apply.

Not that he was unaware of this.

In 2004, Riedel would jovially lay out that “Liz Smith and I have developed a nice tag-team act: I bash fragile Broadway leading ladies who miss performances, and she rides to their rescue.”

Donna Murphy was the recipient of what he that year dubbed his “BERNADETTE PETERS ATTENDANCE AWARD”, when she began missing performances in “Wonderful Town”, due to “severe back and neck injuries and a series of colds and sinus infections”.

This speaks to his remarkably cavalier and joyful attitude with which he tears down shows and performers. “The more Mr. Riedel's work upsets people, the more he enjoys it.”

He knows he yields influence – it was recognised he had “eclipsed Ben Brantley as the single most discussed element in marketing meetings for Broadway shows” – and he delights in his capacity to lead shows to premature demises through his poison-tipped quill yielding.

When it was reported Gypsy would be closing earlier than had been planned, he made mention of “hop[ping] around on [its] grave” and debonairly applauding himself, “I suppose I can take some credit for bringing it down”.

His premonition from the previous year’s Tony’s ceremony was both ominous and prescient, when he predicted the show’s failure to win any awards “could spell trouble at the box office”. He was right. It did. The 8.5 million dollar revival closed months before anticipated and failed to return a profit.

Multiple factors can be attributed to Gypsy’s poor success at the Tony’s, but it’s clear to say Riedel’s continual bashing leading up to the fated night throughout the voting period certainly didn’t help matters.

His suggestions to do with Bernadette’s performances were not helpful either.

After alleging Laurents as the director of the 1991 revival “practically beat a performance out of” Tyne Daly when she was struggling with the role, he proffers that to improve Bernadette’s success, “it may be time for [Laurents] to take up the switch and thrash one out of Peters”.

Great.

It was irresponsible and unrelenting commentary that did not go unnoticed.

His “ruthless heckling of beloved Broadway star Ms. Peters” was deemed in print “his most egregious stunt so far”.

Vividly, in person, Riedel was accosted at a party one night by Floria Lasky, the venerable showbiz lawyer, who “grab[bed] Riedel’s tie and jerk[ed] it, nooselike, scolding, ‘It was unfair, what you did to Bernadette’”.

Moreover, the wide-reaching influential hold Riedel occupied over the environment surrounding Gypsy was tangible in the fact his words spread beyond just average readers, and even unusually “started seeping into the reviews of New York's top critics”. Riedel himself, as the “chief vulture”, was indeed what Ben Brantley was referring to in his own New York Times review by stating how the production was “shadowed by vultures predicting disaster”.

Even more substantially, the “whole Peters-Riedel-Brantley episode” became its own enduring cultural reference – being converted into its very own “satiric cabaret piece, ‘Bernadette and the Butcher of Broadway’”. All three parties were featured, with Riedel characterised as the butcher, and it played Off-Broadway later in 2003 “to positive notices”.

But penitent for his sins and begging for absolution Riedel was not. “Riedel saw nothing but a great story and a great time,” and for many years after, he would continue to hark back to the matter in self-referential (almost reverential) and flippant ways.

In 2008 as Patti LuPone won her Tony for her turn as Rose in the subsequent revival, Riedel couldn’t help but jibe, “Not to rip open an old wound, but I'd love to know if Bernadette Peters was watching”. (He neglects also to mention that “Mendes’s Gypsy was seen by 100,000 more people than saw Laurents’s and grossed $6 million more”.)

More jibes are to be found in 2012 as he reported on the auction after Arthur Laurents’ funeral, or even as recently in 2019, as he asked, “Remember the outcry that greeted Sam Mendes’ Brechtian “Gypsy,” with Bernadette Peters, in 2003?”

As with in 2004 where he points to the “pack of jackals who have been snarling” about Bernadette’s failures, this brings up the canny knack Riedel has of offloading his views to bigger and detached third party sources – thus absolving himself of personal centrality, and thus culpability.

If there was an outcry, HE was its loudest contributor. If there were snarling jackals, HE was their leader.

Maybe Riedel’s third person detached approach to referencing matters was intended to be a humorous stylistic quirk for those in the know. Or maybe it was his way of expressing some inner turmoil over the event.

In some rare display of morality and emotional authenticity, Riedel would at one point admit “I find it kind of sad and pathetic that the high point of my life supposedly has been about beating up on Bernadette Peters”.

Fortunately for him then, a degree of absolution was eventually achieved in 2018, where Riedel visited Bernadette at her opening night in Hello Dolly in 2018, with the intention of ending their “15-year feud”. He “got down on one knee at Sardi’s and extended his hand,” with Bernadette reportedly yelling “Take a picture!” while he held his deferential and obsequious position on the floor.

So if eventually this “feud” has some kind of circular resolution and Riedel was glad it was over, why on earth did it begin in the first place?

One notion is that it was simply another day on the job. Riedel is a man who sees Broadway as “a game for rich people”. Positioned as an “an industry that brought in $720.9 million in the 2002-2003 season”, it is “not a fragile business”, he remarked. As such, he “[could not] fathom the point of donning kid gloves” in covering it, and reasoned the business as a whole was robust enough to weather a few hard knocks. “Thus, Riedel can coolly view Bernadette Peters as fair game, as opposed to, say, a national treasure”.

More to the point, he was a man in search of words. During the season in question, Riedel was “one of just three New York newspaper columnists covering the stage” – a “throwback to a bygone era when…Broadway gossipmeisters…such as Walter Winchell and Dorothy Kilgallen ruled”. Now at the time, as the “last of a great tabloid tradition”, Riedel presided over not just one but two columns a week at The Post. As a result, he was in need of content. “One of the reasons I've become more opinionated is I just have more space to fill,” he admitted. Robert Simonson hypothesises in his book ‘On Broadway Men, Still Wear Hats’ that Riedel may have consequently picked “the thrashing of Bernadette” as his main target simply because “it was a slow news cycle”. Options for ‘titillating’ and durable content were scarce elsewhere that season.

And after all, if Riedel would later cite Bernadette in an article concerning the Top 10 Powerhouses of Broadway in 2004, saying even despite a few knocks or bad shows, “she’ll bounce back” – surely there was no real damage done.

If her career wouldn’t be toppled by his continual public defamation and haranguing, what was the harm?

Feelings? Who cares about feelings or Bernadette’s extremely complex and personal history with the show stretching back to when she was a teenager.

It was just part of the territory, there was nothing personal in it.

Or was there?

Maybe there was something personal in Riedel’s campaign after all.

He makes a curious comment while discussing ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ in 2004. The then incoming star of the show, rapper P. Diddy, had invited Riedel to dinner, and he makes judgement that this was “a smart p.r. move”. Then he ponders, “you do have to wonder: If Bernadette Peters had broken bread with me this time last year, would her chorus boys have to be out there now working the TKTS line to keep "Gypsy" afloat?”

Might he be going as far to suggest that if Bernadette had indulged him in a meal, her show might not have suffered so, by way of him being more inclined to cover it with greater lenience?

It may seem that way, at least in considering how Riedel reviewed P. Diddy’s performance thus after their dinner: “Riedel pronounced himself impressed. ‘He could have forgotten his lines or had to be carried offstage. He didn’t do anything terrible, he didn’t do anything astonishing.’”

Seemingly all the rapper had to do was remember some words and remain physically onstage, and he sails through scot-free. That’s a rather different outcome, one could say, to being absolutely eviscerated for what became a Tony nominated effort at one of the appreciably hardest and most demanding musical theatre roles in existence.

Though perhaps it’s hard to tell if that was really his insinuation from just one isolated comment pertaining to lunch.

This argument might be fine, if it WAS the only isolated comment pertaining to wanting Bernadette to have lunch with him. But it isn’t. Riedel continues to make a further two references over protracted periods of time to the fact Bernadette hasn’t dined with him.

One begins to get the sense of him feeling desiring of or somewhat entitled to such a private lunch with the lady he’s verbally decimated for years, and a sense of bitter rejection that he hasn’t been granted one.

“If Tonya Pinkins doesn't win the Tony Award this year, I'll buy Bernadette Peters lunch,” he simpered, and later, “I invite Bernadette to be my guest for lunch at a restaurant of her choosing. She can reach me at The Post anytime she's hungry”.

The embittered columnist in this light takes on now the marred tinge of a small boy in the playground who doesn’t get to hold the hand of the girl he wants in front of his friends, so spends the next three years pushing her over in the sandpit in revenge.

Moreover, the last statement makes undeniable comment on Bernadette’s troubled relationship with food, body image and public eating.

So now not only so far has he insulted and mocked her physical appearance and played into all the usual trite shots calling her a “kewpie doll”; suggested Arthur Laurents violently hit her in order to elicit a better performance; continually publicly harassed her regarding a show that strikes close to the nerve with deep personal and psychological resonances due to her mother and childhood; but now he’s going for the low-blows of ridiculing her over her eating habits.

Flawless behaviour.

Maybe it’s far-fetched to suggest a man would have such a fragile ego to run a multi-year public defamation campaign after so little as not getting his hypothesised fantasy of a personal lunch date. But then again, this was the man who “left Johns Hopkins University after his first year because of a broken heart.”

(“I was in love with her; she wasn't in love with me,” he said.)

And also the man described as “an insomniac who pops the occasional Ambien,” living in a “small one-bedroom” that is “single-guy sloppy”, who has “been living alone since a four-year romance ended in 1996”.

The man whose own best friend called “cruel” and with a “lack of empathy”.