#Elamite art

Text

#MetalMonday:

Figurine of a mountain goat

Iranian, Proto Elamite, 3100-2750 BCE

Silver & sheet gold, 4 x 7 cm (1 9/16 x 2 3/4 in.)

On view at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

“This object is one of the earliest surviving Near Eastern sculptures in precious metal. The goat is made of silver and plated with gold on the face.

Incised lines illustrate the texture of the goat's hair and beard. One leg protrudes far from the body, two are held in close, and the last is only visible as an incised outline carefully etched into the figurine's underside.”

additional images via https://collections.mfa.org/objects/155898/mountain-goat

#animals in art#museum visit#mountain goat#metalwork#silver#gold#figurine#sculpture#Iranian art#ancient art#Elamite art#Proto Elamite art#Museum of Fine Arts Boston#Metal Monday

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Mountain goat.

Place of origin: Near Eastern, Iranian

Period: Elamite, Proto-Elamite

Date: 3500–2700 B.C.

Medium: Silver and sheet gold.

#ancient#history#ancient art#museum#archeology#ancient sculpture#ancient history#archaeology#iran#iranian#near east#near eastern#elamite#3500 b.c.#2700 b.c#silver#goat#mountain goat

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Silver kneeling bull with spouted vessel, Proto-Elamite, 3100 - 2900 BC

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

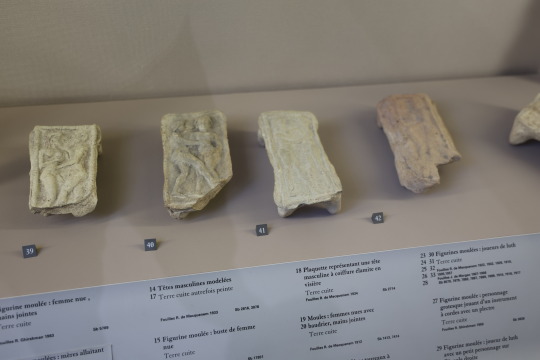

Terracottas from Susa, Iran

Middle Elamite period, 14th-12th centuries BCE

Musée du Louvre

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

"This mold-made female figure is depicted with a patterned headdress and wears crossed shoulder bands that hang thought a slip ring between her breasts and are incised with a herringbone pattern. She is adorned with a necklace, three bracelets on each wrist, and anklets. She holds her breasts in her hands, her enlarged pubic triangle is made up of rows of curls, and her flat but fleshy body and distended legs are characteristic of nude female figures of this period. The figure confronts the gaze of the viewer with her wide, rimmed eyes."

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vessel in the form of a boar - painted ceramic - Proto-Elamite culture - Southwestern Iran - c.3100–2900 BCE

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

AN ELAMITE BANDED AGATE DUCK

IRAN, CIRCA 1200 B.C.

2 in. (5 cm.) long.

Courtesy: Christie’s

274 notes

·

View notes

Text

an elamite horror is born

#my art#artists on tumblr#digital art#character design#original art#original character#folklore#elamite#elam#iranian#oc#mythology#horror#historical#sketch

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

#ShortVideo: A 3400-year-old Elamite helmet, made of bronze and gold.

Elam was one of the ancient civilizations in the southwest of Iran.

Follow my YouTube channel. Silent tablets documentary, short videos from ancient history.

Follow my Twitter.

#elam#elamite#iran#ancient iran#ancient mesopotamia#mesopotamia#elam culture#archaeology#archeology#museum#ancient art#museum travel#museum trips

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silver antelope pendant, Proto-Elamite, 3100 - 2900 BC

from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gate of All Nations

The Gate of Xerxes -UNESCO World Heritage

(r. 486 – 465 BC) Persepolis - IRAN

The bronze trumpets that once signaled the arrival of important foreign delegations to Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the mighty Achaemenid Empire, may now be silent, but it is still possible to capture the sense of awe while visiting the colossal Gate of Xerxes.

Built during the reign of Achaemenid king Xerxes I , who called this his Gate of All Nations, the pillared entrance is guarded by bearded and hoofed mythical figures in the style of Assyrian gate-guards.

On arrival at Persepolis one is confronted by an imposing wall, completely smooth and plain, about 15 meters tall: this is the artificial terrace on which the palaces were built. This vast terrace of Persepolis, some 450 meters long and 300 meters wide, was originally fortified on three sides by a tall wall. The only access was from the monumental staircase, which leads to the Gate of All Nations.

The gateway bears a cuneiform inscription in Old Persian, Neo-Babylonian, and Elamite languages declaring, among other things, that Xerxes is responsible for the construction of this and many beautiful wonders in Persia. Centuries of graffitists have also left their mark, including explorer Henry Morton Stanley.

A pair of colossal bulls guarded the western entrance; two man-bulls stood at the eastern doorway. Engraved above each of the four colossi is a trilingual inscription attesting to Xerxes having built and completed the gate. The doorway on the south, opening toward the Apadana, is the widest of the three.

According to sources, pivoting devices found on the inner corners of all the doors indicate that they must have had two-leaved doors, which were probably made of wood and covered with sheets of ornamented metal.

Persepolis, also known as Takht-e Jamshid, whose magnificent ruins rest at the foot of Kuh-e Rahmat ("Mountain of Mercy"), was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire. It is situated 60 kilometers northeast of the city of Shiraz in Fars Province.

Persepolis was the seat of the government of the Achaemenid Empire, though it was designed primarily to be a showplace and spectacular center for the receptions and festivals of the kings and their empire.

The royal city ranks among the archaeological sites which have no equivalent, considering its unique architecture, urban planning, construction technology, and art.

The city was burnt by Alexander in 330 BC apparently as revenge to the Persians

The immense terrace of Persepolis was begun about 518 BC by Darius the Great, the Achaemenid Empire’s king. On this terrace, successive kings erected a series of architecturally stunning palatial buildings, among them the massive Apadana palace and the Throne Hall (“Hundred-Column Hall”).

This 13-ha ensemble of majestic approaches, monumental stairways, throne rooms (Apadana), reception rooms, and dependencies is classified among the world’s greatest archaeological sites.

#art#design#doorway#architecture#heavensdoorways#gateway#entryway#iran#persepolis#bull#royal#royal city#style#history#gates of xerses#unesco world heritage#monumental#gate of all nations#achaemenid#persia#xerxes#front door#architrave

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Basic misconceptions about Mesopotamian mythology

Most of the so-called “Sumerian mythology” is simply the school curriculum of Old Babylonian scribes who did not speak Sumerian as a vernacular anymore, it’s a misnomer, sort of like calling medieval European copies of the Bible written in Latin “Latin mythology” would be. Sumerian is chiefly a language, not a religion.

It is difficult to tell if there ever was a full separation between “Sumerian” and “Akkadian” pantheons since even in the linguistically “most Sumerian” Lagash deities with Akkadian names were worshiped since the dawn of recorded history, most notably Ishtaran. There were also areas where Mesopotamian deities were basically mixed with Hurrian (Arrapha = modern Kirkuk) or Elamite (Susa and the “Elamite lowlands”) ones.

“Seven gods who decree” were largely invented by early Assyriologists who wanted a coherent, self-contained pantheon. In reality the composition of the top of the pantheon varied by both time period and location and rarely, if ever, the gods on top were seven in number.

Multiple deities early authors like Kramer or Jacobsen didn’t even bother to write about can easily count as “major,” for example Ishtaran or Nanaya.

Mesopotamian gods did not necessarily embody forces of nature nor was being related to a specific force of nature a prerequisite for being a major deity. In fact, some of the most major ones were tied to activities directly tied to organized society, like specific cities, medicine or scribal arts. Many deities who have nothing to do with nature are already attested in the oldest documents, too, for example the metalworker goddess Ninmug.

There are multiple works of literature older than Epic of Gilgamesh. Literally dozens.

Enuma Elish being treated as some grand central text of Mesopotamian mythology is kind of as if one tried to gain full understanding of Greek mythology by centering the declaration of deification of a single Roman emperor. Also, Tiamat is virtually absent from Mesopotamian texts otherwise.

It is physically impossible to draw a single family tree of Mesopotamian gods and in at least some cases new ancestors were invented specifically to avoid divine incest (confirmed by Wilfred G. Lambert). There are multiple deities with no genealogy to speak of, including regional gods, spouses of most major deities and divine courtiers. The genealogy of many deities was variable, too.

This being said - Nanna(/Suen) and Ningal being parents of Inanna was the default, not a variant tradition. Epic of Gilgamesh is an outlier in not following this view. Such was the power of this tradition that foreign deities treated as analogous to Inanna/Ishtar were assigned as children to corresponding moon gods... or just outright “borrowed” Nanna and Ningal as parents, as in the case of Pinikir.

The names Inanna and Ishtar more or less variably designated the goddess of Uruk, but there were other, not necessarily fully identical goddesses sharing these names - Inanna of Zabalam (that’s the one with a son, not Inanna of Uruk), Ishtar of Kish, “Ishtar” of Nineveh (in reality Hurrian Shaushka) and more. There were also multiple medicine goddesses. Many recent studies (1990s onward) generally emphasize the differences instead of lumping them together.

Inanna was not blamed for Dumuzi’s death in most compositions dealing with it.

Queen Kubaba has nothing to do with the similarly named goddess from northern Syria.

231 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm low-key losing it, do you have any idea what the abbreviation RIMI, by Christopher B.F. Walker 1981, might refer to? CDLI lists it as having the publications of a bunch of Middle Elamite stuff (such as this lovely iron ring) but all I can find is Walker 1981, Cuneiform Brick Inscriptions in the British Museum. I figured it might be some long-lost Iranian RIME spin-off but no hits for that. I've checked the AfO register and there's nothing. Any clue?

Hello! Sometimes an ask leads me on a deeper hunt than I ever expected.

I also couldn't find a reference for RIMI - but based on the pattern of other Royal Inscription of Mesopotamia projects (a series of publications from the University of Toronto), my best guess is that the I does stand for Iranian. Here's an Oracc article on the history and significance of royal inscriptions, with citations to several of the publications.

I ended up reaching out to the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, where the ring you linked is housed. After a couple calls referring me to different departments, I learned that RIMI is almost certainly a translation project in the RIM series that C.B.F. Walker never finished or published. I'm not sure why it's listed as 1981, since the MFA's records have "no date (of publication)". 1981 is also before the MFA acquired the ring in 1985, and they have no known translation work done on it since then - so it's possible the only person who's every translated the text on the ring is Walker himself.

They did refer me to one other reference about this ring, though, also from 1981 - Muscarella's article on Surkh Dum excavations in the Journal of Field Archaeology (JStor link, the ring section is p. 344). I can't tell exactly what ring in that article is referring to this particular one, but one is mentioned as having the inscription dingir-mesh (Sumerian for "they are gods" or "... are the gods"), which Muscarella says is "part of a prayer invoking the gods." On the rings, Muscarella cites Porada 1964 ("Nomads and Luristan Bronzes", which I can't find a link for, but you can find a description of her work in this 1989 Encyclopaedia Iranica article).

Circling back to Walker, he was a curator of Western Asiatic antiquities at the British Museum, so I reached out to them next. I learned that they don't keep contact info for retired staff members, and I don't know of another way to contact him (or even where he is now). Unfortunately this is a frequent issue I've encountered in Mesopotamian research - somebody works on things, doesn't end up publishing, and then retires or changes field, taking everything with them.

If there's an Elamite expert who might have any other leads, please let me know! (And special thanks to Paul at the MFA Boston library for your help in this search!)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold decorated bronze helmet, Elamite, 1500 - 1100 BC

from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Basalt pedestal depicting scenes of slain combatants being eaten by vultures, captives being led away and killed

Neo-Elamite period, 7th-6th century BCE

Susa, Iran

Musée du Louvre, Sb 5

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who was the founder of the first central government in Iran?

The founder of the first central government in Iran dates back to the Achaemenid period by Cyrus the Great. Achaemenid Cyrus was crowned in 550 BC and established the first central government in Iran.

The origin of the name Iran

The country of Iran was not called "Iran" from the beginning and was known by the names of Persia, Pars and Pers among others. Saeed Nafisi suggested the word "Iran" instead of "Persia" in January 1313 AH. The naming initially caused opposition. Because the politicians considered "Persia" as an international name that was familiar among all types. The supporters of this naming also considered the term "Iran" as the best name to describe the political authority and cultural background of this country.

In 1314 AH, based on the circular of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Iran and the request of the then government of Reza Shah, the word "Iran" was officially used to name the country and replace other names. Professor Arthur Upham Pope, an American Iranologist, writes in the book Masterpieces of Iranian Art translated by Parviz Natal Khanleri:

The word "Iran" was used for the plateau and geographical functions of Iran in the first millennium BC.

According to Mohammad Moin, the great Iranian writer, the origin of the word "Arya" is so clear that the eastern part of Indo-Europe considers themselves proud of this name. Indo-Iranian common ancestors also introduced themselves with this name and named their country as "Iran-Oejah".

Pre-Islamic era in Iranian history

The pre-Islam era, which includes various events in the history of Iran, includes the time period before the arrival of the Aryans, that is, the rule of Elam until the end of the Sassanid rule and the arrival of the Arabs in Iran. According to historical sources, before the Aryans entered Iran, the Elamites lived as a native dynasty in the Iranian plateau.

The Elam dynasty was formed in the southwestern region of the Iranian plateau around 3,000 years BC, and they named their territory "Hatmati". The rule of Elam expanded during the period of the famous kings of this dynasty, and they dominated parts of Mesopotamia (Mesopotamia) in addition to southwestern Iran.

Whenever the Elamites gained more power, they played an important role in the Middle River politics. They overcame Sumer around 2,000 BC and completely subjugated the Mesopotamia. Historians divide the political history of Elam into three periods:

Ancient Elam, Middle Elam and New Elam

The migration of Aryans to the Iranian plateau

In the third period of the rule of Elam, the Medes, as a group of Aryans, established their power in the northwest of Iran and took control of that part of Iran. The Parthians (Ashkanians) and the Persians (Achaemenians and their successors, who were called the Sasanians) were two other Aryan tribes who formed a government in the Iranian plateau after the Medes.

There are many theories about the ethnicity, race and migration of Aryans and their entry into Iran, which are the source of disagreement among scholars and have not yet reached a single conclusion about them. Some consider Siberia as the origin of Aryans and believe that they entered the Iranian plateau from there.

The post-Islam era in Iranian history

Yazdgerd III, the last Sassanid king, was defeated by the Arabs and left Iran to them. "Rostam Farrokhzad" was defeated by the Arabs in the battle of Qadisiyah (636 AD) and lost his life despite his bravery. He organized his forces and was defeated by the Arabs in the war that took place in Nahavand (642 AD). Yazdgerd fled to the East with his family and was killed near Merv. With the death of Yazdgerd III, his empire fell in 651 AD.According to the book "Two Centuries of Silence" by "Abd al-Hossein Zarinkoub", some Iranians were not satisfied with the arrival of Arabs in the country and continued to adhere to the Zoroastrian religion. Zoroastrian Iranians paid tribute to music during this period. According to Zarinkoob, Iranians do not accept Islam with open arms and during this time, they were fighting with the Arabs in the corners and sides of Iran in order to advance them. On the other hand, Shahid Motahari criticized Zarinkoub in his book "Mutual Services of Islam and Iran" and did not consider his opinion to be scientific. He believes that Iranians accepted Islam with open arms.

The land of Iran gradually surrendered to the Arabs and only Tabaristan and Gilan maintained their independence by resisting. During this period, government powers did not rule in Iran and local governments have power in some parts of Iran.

The domination of Arabs over Iran caused their culture to be revealed in Iran, and with the beginning of independent Islamic governments in Iran, the Hijri lunar calendar, the foundations of historians in writing the history of Iran, was published.

contemporary history

World War II brought chaos to Iran and Reza Shah resigned from the throne. Mohammad Reza succeeded his father in 1320 AH (1941 AD). The creation of the 14th Parliament, the nationalization of the oil industry, the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Iran after the end of World War II, the August 28 coup, the Baghdad Pact, and the formation of the Iranian National Front were among the most important events of this period.

With the formation of the Islamic Revolution in 1357 AH (1978 CE), the life of Pahlavi rule ended and the Islamic Republic replaced it.

11 notes

·

View notes