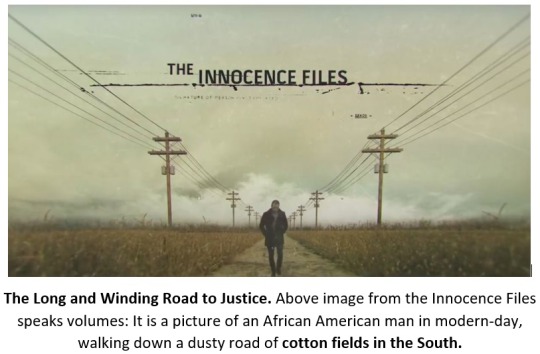

#It’s Time To Admit The Social Justice Movement Is Founded On Racism

Text

It’s Time To Admit The Social Justice Movement Is Founded On Racism

"…Just because the targets of racism may have changed from the pre-Civil Rights Era to the present doesn’t mean the underlying racism is any less abhorrent and unacceptable…"

https://www.undergroundusa.com/p/its-time-to-admit-the-social-justice

SHARE & EDUCATE

x

#It’s Time To Admit The Social Justice Movement Is Founded On Racism#“...Just because the targets of racism may have changed from the pre-Civil Rights Era to the present doesn’t mean the underlying racism is#https://www.undergroundusa.com/p/its-time-to-admit-the-social-justice#SHARE & EDUCATE#Racism#Discrimination#MLK#DEI#Kendi#CRT#CriticalRaceTheory#Berkeley#SystemicRacism#BLM#Nullification#Constitution#BillOfRights#Marxism#FreeSpeech#USA#Woke#Democrats#Politics#Government#News#UndergroundUSA#Truth @MarkLevin @TuckerCarlson @GlennBeck @VDHanson @marklevinshow @RWMaloneMD

0 notes

Text

Rivera, Kahlo, and the Detroit Murals: A History and a Personal Journey

The year 1932 was not a good time to come to Detroit, Michigan. The Great Depression cast dark clouds over the city. Scores of factories had ground to a halt, hungry people stood in breadlines, and unemployed autoworkers were selling apples on street corners to survive. In late April that year, against this grim backdrop, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo stepped off a train at the cavernous Michigan Central depot near the heart of the Motor City. They were on their way to the new Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), a symbol of the cultural ascendancy of the city and its turbo-charged prosperity in better times. The next 11 months in Detroit would take them both to dazzling artistic heights and transform them personally in far-reaching, at times traumatic, ways.

I subtitle this article “a history and a personal journey.” The history looks at the social context of Diego and Frida’s defining time in the city and the art they created; the personal journey explores my own relationship to Detroit and the murals Rivera painted there. I was born and raised in the city, listening to the sounds of its bustling streets, coming of age in its diverse neighborhoods, growing up with the driving beat of its music, and living in the shadows of its factories. Detroit was a labor town with a culture of social justice and civil rights, which on occasion clashed with sharp racism and powerful corporations that defined the age. In my early twenties, I served a four-year apprenticeship to become a machine repair machinist in a sprawling multistory General Motors auto factory at Clark Street and Michigan Avenue that machined mammoth seven-liter V8 engines, stamped auto body parts on giant presses, and assembled gleaming Cadillacs on fast-moving assembly lines. At the time, the plant employed some 10,000 workers who reflected the racial and ethnic diversity of the city, as well as its tensions. The factory was located about a 20-minute walk from where Diego and Frida got off the train decades earlier but was a world away from the downtown skyscrapers and the city’s cultural center.

I grew up with Rivera’s murals, and they have run through every stage of my life. I’ve been gone from the city for many years now, but an important part of both Detroit and the murals have remained with me, and I suspect they always will. I return to Detroit frequently, and no matter how busy the trip, I have almost always found time for the murals.

In Detroit, Rivera looked outwards, seeking to capture the soul of the city, the intense dynamism of the auto industry, and the dignity of the workers who made it run. He would later say that these murals were his finest work. In contrast, Kahlo looked inward, developing a haunting new artistic direction. The small paintings and drawings she created in Detroit pull the viewer into a strange and provocative universe. She denied being a Surrealist, but when André Breton, a founder of the movement, met her in Mexico, he compared her work to a “ribbon around a bomb” that detonated unparalleled artistic freedom (Hellman & Ross, 1938).

Rivera, at the height of his fame, embraced Detroit and was exhilarated by the rhythms and power of its factories (I must admit these many years later I can relate to that response). He was fascinated by workers toiling on assembly lines and coal-fired blast furnaces pouring molten metal around the clock. He felt this industrial base had the potential to create material abundance and lay the foundation for a better world. Sixty percent of the world’s automobiles were built in Michigan at that time, and Detroit also boasted other state-of-the-art industry, from the world’s largest stove and furnace factory to the main research laboratories for a global pharmaceutical company.

“Detroit has many uncommon aspects,” a Michigan guidebook produced by the Federal Writers Project pointed out, “the staring rows of ghostly blue factory windows at night; the tired faces of auto workers lighted up by simultaneous flares of match light at the end of the evening shift; and the long, double-decker trucks carrying auto bodies and chassis” (WPA, 1941:234). This project produced guidebooks for every state in the nation and was part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal Agency that sought to create jobs for the unemployed, including writers and artists. I suspect Rivera would have embraced the approach, perhaps even painted it, had it then existed.

Detroit was a rough-hewn town that lacked the glitter and sophistication of New York or the charm of San Francisco, yet Rivera was inspired by what he saw. In his “Detroit Industry” murals on the soaring inner walls of a large courtyard in the center of the DIA, Rivera portrayed the iconic Ford Rouge plant, the world’s largest and most advanced factory at the time. “[These] frescoes are probably as close as this country gets to the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel,” New York Times art critic Roberta Smith wrote eight decades later (Smith, 2015).

The city did not speak to Kahlo in the same way. She tolerated Detroit — sometimes barely, other times with more enthusiasm — rather than embracing it. Kahlo was largely unknown when she came to Detroit and felt somewhat isolated and disconnected there. She painted and drew, explored the city’s streets, and watched films — she liked Chaplin’s comedies in particular — in the movie theaters near the center of the city, but she admitted “the industrial part of Detroit is really the most interesting side” (Coronel, 2015:138).

During a personally traumatic year — she had a miscarriage that went seriously awry in Detroit, and her mother died in Mexico City — she looked deeply into herself and painted searing, introspective works on small canvases. In Detroit, she emerged as the Frida Kahlo who is recognized and revered throughout the world today. While Vogue still identified her as “Madame Diego Rivera” during her first New York exhibition in 1938, the New York Times commented that “no woman in art history commands her popular acclaim” in a 2019 article (Hellman & Ross, 1938; Farago, 2019).

My emphasis will be on Rivera and the “Detroit Industry” murals, but Kahlo’s own work, unheralded at the time, has profoundly resonated with new audiences since. While in Detroit, they both inspired, supported, influenced, and needed each other.

Prelude

Diego and Frida married in Mexico on August 21, 1929. He was 43, and she was 22 — although their maturity, in her view, was inverse to their age. Their love was passionate and tumultuous from the beginning. “I suffered two accidents in my life,” she later wrote, “one in which a streetcar knocked me down … the other accident is Diego” (Rosenthal, 2015:96).

They shared a passion for Mexico, particularly the country’s indigenous roots, and a deep commitment to politics, looking to the ideals of communism in a turbulent and increasingly dangerous world (Rosenthal, 2015:19). Rivera painted a major set of murals — 235 panels — in the Ministry of Education in Mexico City between 1923 and 1928. When he signed each panel, he included a small red hammer and sickle to underscore his political allegiance. Among the later panels was “In the Arsenal,” which included images of Frida Kahlo handing out weapons, muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros in a hat with a red star, and Italian photographer Tina Modotti holding a bandolier.

The politics of Rivera and Kahlo ran deep but didn’t exactly follow a straight line. Kahlo herself remarked that Rivera “never worried about embracing contradictions” (Rosenthal, 2015:55). In fact, he seemed to embody F. Scott Fitzgerald’s notion that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function” (Fitzgerald, 1936).

Their art, however, ultimately defined who they were and usually came out on top when in conflict with their politics. When the Mexican Communist Party was sharply at odds with the Mexican government in the late 1920s, Rivera, then a Party member, nonetheless accepted a major government commission to paint murals in public buildings. The Party promptly expelled him for this act, among other transgressions (Rosenthal, 2015:32).

Diego and Frida came to San Francisco in November 1930 after Rivera received a commission to paint a mural in what was then the San Francisco Stock Exchange. He had already spent more than a decade in Europe and another nine months in the Soviet Union in 1927. In contrast, this was Kahlo’s first trip outside Mexico. The physical setting in San Francisco, then as now, was stunning — steep hills at the end of a peninsula between the Pacific and the Bay — and they were intrigued and elated just to be there. The city had a bohemian spirit and a working-class grit. Artists and writers could mingle with longshoremen in bars and cafes as ships from around the world unloaded at the bustling piers. At the time, California was in the midst of an “enormous vogue of things Mexican,” and the couple was at the center of this mania (Rosenthal, 2015:32). They were much in demand at seemingly endless “parties, dinners, and receptions” during their seven-month stay (Rosenthal, 2015:36). A contradiction with their political views? Not really. Rivera felt he was infiltrating the heart of capitalism with more radical ideas.

Rivera’s commission produced a fresco on the walls of the Pacific Stock Exchange, “Allegory of California” (1931), a paean to the economic dynamism of the state despite the dark economic clouds already descending. Rivera would then paint several additional commissions in San Francisco before leaving. While compelling, these murals lacked the power and political edge of his earlier work in Mexico or the extraordinary genius of what was to come in Detroit.

While in San Francisco, Rivera and Kahlo met Helen Wills Moody, a 27-year-old world-class tennis player, who became the central model for the Allegory mural. She moved in rarified social and artistic circles, and as 1930 drew to a close, she introduced the couple to Wilhelm Valentiner, the visionary director of the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), who had rushed to San Francisco to meet Rivera when he learned of the artist’s arrival.

Valentiner was “a German scholar, a Rembrandt specialist, and a man with extraordinarily wide tastes,” according to Graham W.J. Beal, who himself revitalized the DIA as director in the 21st century. “Between 1920 and the early 1930s, with the help of Detroit’s personal wealth and city money, Valentiner transformed the DIA … into one of the half-dozen top art collections in the country,” a position the museum continues to hold today (Beal, 2010:34). The museum director and the artist shared an unusual kinship. “The revolutions in Germany and Mexico [had] radicalized [both],” wrote Linda Downs, a noted curator at the DIA (Downs, 2015:177). Little more than a decade later, “the idea of the mural commission reinvigorated them to create a highly charged monumental modern work that has contributed greatly to the identity of Detroit” (Downs, 2015:177).

When Valentiner and Rivera met, the economic fallout of the Depression was hammering both Detroit and its municipally funded art institute. The city was teetering at the edge of bankruptcy in 1932 and had slashed its contribution to the museum from $170,000 to $40,000, with another cut on the horizon. Despite this dismal economic terrain, Valentiner was able to arrange a commission for Rivera to paint two large-format frescoes in the Garden Court at the new museum building, which had opened in 1927. Edsel Ford, the son of Henry Ford and a major patron of the DIA, pledged $10,000 for the project — a truly princely sum at that moment — and would double his contribution as Rivera’s vision and the scale of the project expanded (Rosenthal, 2015:51). Edsel also played an unheralded role in support of the museum through the economic traumas to come.

A discussion of Rivera’s mural commission gets a bit ahead of our story, so let’s first look at Detroit’s explosive economic growth in the early years of the 20th century. This industrial transformation would provide the subject and the inspiration for Rivera’s frescoes.

The Motor City and the Great Depression

At the turn of the 20th century, Detroit “was a quiet, tree-shaded city, unobtrusively going about its business of brewing beer and making carriages and stoves” (WPA, 1941:231). Approaching 300,000 residents, Detroit was the 13th-largest city in the country (Martelle, 2012:71). A future of steady growth and easy prosperity seemed to beckon.

Instead, Henry Ford soon upended not only the city, but much of the world. He was hardly alone as an auto magnate in the area: Durant, Olds, the Fisher Brothers, and the Dodge Brothers, among others, were also in or around Detroit. Ford, however, would go beyond simply building a successful car company: he unleashed explosive growth in the auto industry, put the world on wheels, and became a global folk hero to many, yet some were more critical. The historian Joshua Freeman points out that “Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) depicts a dystopia of Fordism, a portrait of life A.F. — the years “Anno Ford,” measured from 1908, when the Model T was introduced — with Henry Ford the deity” (Freeman, 2018:147).

Ford combined three simple ideas and pursued them with razor-sharp, at times ruthless, intensity: the Model T, an affordable car for the masses; a moving assembly line that would jump-start productivity growth; and the $5 day for workers, double the prevailing wage in the industry. This combination of mass production and mass consumption — Fordism — allowed workers to buy the products they produced and laid the basis for a new manufacturing era. The automobile age was born.

The $5 day wasn’t altruism for Ford. The unrelenting pace and control of the assembly line was intense — often unbearable — even for workers who had grown up with back-breaking work: tilling the farm, mining coal, or tending machines in a factory. Annual turnover approached 400 percent at Ford’s Highland Park plant, and daily absenteeism was high. In response, Ford introduced the unprecedented new wage on January 12, 1914 (Martelle, 2012:74).

The press and his competitors denounced Ford — claiming this reckless move would bankrupt the industry — but the day the new rate began, 10,000 men arrived at the plant in the winter darkness before dawn. Despite the bitter cold, Ford security men aimed fire hoses to disperse the crowd. Covered in freezing water, the men nonetheless surged forward hoping to grasp an elusive better future for themselves and their families.

Here is where I enter the picture, so to speak. One of the relatively few who did get a job that chaotic day was Philip Chapman. He was a recent immigrant from Russia who had married a seamstress from Poland named Sophie, a spirited, beautiful young woman. They had met in the United States. He wound up working at Ford for 33 years — 22 of them at the Rouge plant — on the line and on machines. They were my grandparents.

By 1929, Detroit was the industrial capital of the world. It had jumped its place in line, becoming the fourth-largest city in the United States — trailing only New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia — with 1.6 million people (Martelle, 2012:71). “Detroit needed young men and the young men came,” the WPA Michigan guidebook writers pointed out, and they emphasized the kaleidoscopic diversity of those who arrived: “More Poles than in the European city of Poznan, more Ukrainians than in the third city of the Ukraine, 75,000 Jews, 120,000 Negroes, 126,000 Germans, more Bulgarians, [Yugoslavians], and Maltese than anywhere else in the United States, and substantial numbers of Italians, Greeks, Russians, Hungarians, Syrians, English, Scotch, Irish, Chinese, and Mexicans” (WPA, 1941:231). Detroit was third nationally in terms of the foreign-born, and the African American population had soared from 6,000 in 1910 to 120,000 in 1930 (WPA, 1941:108), part of a journey that would ultimately involve more than six million people moving from the segregated, more rural South to the industrial cities of the North (Trotter, 2019:78).

DIA planners projected that Detroit would become the second-largest U.S. city by 1935 and that it could surpass New York by the early 1950s. “Detroit grew as mining towns grow — fast, impulsive, and indifferent to the superficial niceties of life,” the Michigan Guidebook writers concluded (WPA, 1941:231).

The highway ahead seemed endless and bright. The city throbbed with industrial production, the streetcars and buses were filled with workers going to and from work at all hours, and the noise of stamping presses and forges could be heard through open windows in the hot summers. Cafes served dinner at 11 p.m. for workers getting off the afternoon shift and breakfast at 5 a.m. for those arriving for the day shift. Despite prohibition, you could get a drink just about any time. After all, only a river separated Detroit from Canada, where liquor was still legal.

Rivera’s biographer and friend Bertram Wolfe wrote of “the tempo, the streets, the noise, the movement, the labor, the dynamism, throbbing, crashing life of modern America” (Wolfe, as cited in Rosenthal, 2015:65). The writers of the Michigan guidebook had a more down-to-earth view: “‘Doing the night spots’ consists mainly of making the rounds of beer gardens, burlesque shows, and all-night movie houses,” which tended to show rotating triple bills (WPA, 1941:232).

Henry Ford began constructing the colossal Rouge complex in 1917, which would employ more than 100,000 workers and spread over 1,000 acres by 1929. “It was, simply, the largest and most complicated factory ever built, an extraordinary testament to ingenuity, engineering, and human labor,” Joshua Freeman observed (Freeman, 2018:144). The historian Lindy Biggs accurately described the complex as “more like an industrial city than a factory” (Biggs, as cited in Freeman, 2018:144).

The Rouge was a marvel of vertical integration, making much of the car on site. Giant Ford-owned freighters would transport iron ore and limestone from Minnesota and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula down through the Great Lakes, along the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers, and then across the Rouge River to the docks of the plant. Seemingly endless trains would bring coal from West Virginia and Ohio to the plant. Coke ovens, blast furnaces, and open hearths produced iron and steel; rolling mills converted the steel ingots into long, thin sheets for body parts; foundries molded iron into engine blocks that were then precision machined; enormous stamping presses formed sheets of steel into fenders, hoods, and doors; and thousands of other parts were machined, extruded, forged, and assembled. Finished cars drove off the assembly line a little more than a day after the raw materials had arrived at the docks.

In 1928, Vanity Fair heralded the Rouge as “the most significant public monument in America, throwing its shadow across the land probably more widely and more intimately than the United States Senate, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Statue of Liberty.... In a landscape where size, quantity, and speed are the cardinal virtues, it is natural that the largest factory turning out the most cars in the least time should come to have the quality of America’s Mecca, toward which the pious journey for prayer” (Jacob, as cited in Lichtenstein, 1995:13). My grandfather, I suspect, had a more prosaic goal: he needed a job, and Ford paid well.

Despite tough conditions in the plant, workers were proud to work at “Ford’s,” as people in Detroit tended to refer to the company. They wore their Ford badge on their shirts in the streetcars on the way to work or on their suits in church on Sundays. It meant something to have a job there. Once through the factory gate, however, the work was intense and often dangerous and unhealthy. Ford himself described repetitive factory work as “a terrifying prospect to a certain kind of mind,” yet he was firmly convinced strict control and tough discipline over the average worker was necessary to get anything done (Ford, as cited in Martelle, 2012:73). He combined the regimentation of the assembly line with increasingly autocratic management, strictly and often harshly enforced. You couldn’t talk on the line in Ford plants — you were paid to work, not talk — so men developed the “Ford whisper” holding their heads down and barely moving their lips. The Rouge employed 1,500 Ford “Service Men,” many of them ex-convicts and thugs, to enforce discipline and police the plant.

At a time when economic progress seemed as if it would go on forever, the U.S. stock market drove over a cliff in October 1929, and paralysis soon spread throughout the economy. Few places were as shaken as Detroit. In 1929, 5.5 million vehicles were produced, but just 1.4 million rolled off Detroit’s assembly lines three years later in 1932 (Martelle, 2012:114). The Michigan jobless rate hit 40 percent that year, and one out of three Detroit families lacked any financial support (Lichtenstein, 1995). Ford laid off tens of thousands of workers at the Rouge. No one knew how deep the downturn might go or how long it would last. What increasingly desperate people did know is that they had to feed their family that night, but they no longer knew how.

On March 7, 1932 — a bone-chilling day with a lacerating wind — 3,000 desperate, unemployed autoworkers met near the Rouge plant to march peaceably to the Ford Employment Office. Detroit police escorted the marchers to the Dearborn city line, where they were confronted by Dearborn Police and armed Ford Service Men. When the marchers refused to disperse, the Dearborn police fired tear gas, and some demonstrators responded with rocks and frozen mud. The marchers were then soaked with water from fire hoses and shot with bullets. Five workers were killed, 19 wounded by gunfire, and dozens more injured. Communists had organized the march, but a Michigan historical marker makes the following observation: “Newspapers alleged the marchers were communists, but they were in fact people of all political, racial, and ethnic backgrounds.” That marker now hangs outside the United Auto Workers Local 600 union hall, which represents workers today at the Rouge plant.

Five days later, on March 12, thousands of people marched in downtown Detroit to commemorate the demonstrators who had been killed. Although Rivera was still in New York, he was aware of the Ford Hunger March before it took place and told Clifford Wight, his assistant, that he was eager “not [to] miss…[it] on any account” (Rosenthal, 2015:51). Both he and Kahlo had marched with workers in Mexico and embraced their causes. Rivera had captured their lives as well as their protests in his murals in Mexico.

As it turned out, they missed both the march and the commemoration. Instead, the following month Kahlo and Rivera’s train pulled into the Michigan Central Depot, where Wilhelm Valentiner met them. They were taken to the Ford-owned Wardell Hotel next to the Detroit Institute of Arts. The DIA was the anchor of a grass-lined and tree-shaded cultural center several miles north of downtown. The Ford Highland Park Plant, where the automobile age began with the Model T and the moving assembly line, was four miles further north on the same street. Less than a mile northwest was the massive 15-story General Motors Building, the largest office building in the United States when it was completed in 1922, designed by the noted industrial architect Albert Khan, who also created the Rouge. Huge auto production complexes such as Dodge Main or Cadillac Motor — where I would serve my apprenticeship decades later — were not far away.

Valentiner had written Rivera stating, “The Arts Commission would be pleased if you could find something out of the history of Detroit, or some motif suggesting the development of industry in this town. But in the end, they decided to leave it entirely to you” (Beal, 2010:35). Beal points out “that what Valentiner had in mind at the time may have been something like the Helen Moody Wills paintings, something that had an allegorical slant to it. They were to get something completely different” (Beal, 2010:35). Edsel Ford emphasized he wanted Rivera to look at other industries in Detroit, such as pharmaceuticals, and provided a car and driver for Rivera and Kahlo to see the plants and the city.

But when Rivera visited the Rouge plant, he was mesmerized. He saw the future here, despite the fact that the plant had been hard hit by the Depression: the complex had been shuttered for the last six months of 1931, and thousands of workers had been let go before he arrived (Rosenthal, 2015:67). His fascination with machinery, his respect for workers, and his politics fused in an extraordinary artistic vision, which he filled with breathtaking technical detail. He had found his muse.

Rivera took on the seemingly impossible task of capturing the sprawling Rouge plant in frescoes. The initial commission of two large-format frescoes rapidly expanded to 27 frescoes of various sizes filling the entire room from floor to ceiling. Rivera spent the next two months at the manufacturing complex drawing, pacing, photographing, viewing, and translating these images into large drawings — “cartoons” — as the plans for the frescoes. He demonstrated an exceptional ability to retain in his head — and, I suspect, in his dreams — what he would paint.

Rivera’s Vast Masterpieces

Rivera’s “Detroit Industry” murals are anchored in a specific time and place — a sprawling iconic factory, the Depression decade, and the Motor City — yet they achieve the universal in a way that transcends their origins. Rivera painted workers toiling on assembly lines amid blast furnaces pouring molten iron into cupolas, and through the alchemy of his genius, the art still powerfully — even urgently — speaks to us today. The murals celebrate the contribution of workers, the power of industry, and the promise and peril of science and technology. Rivera weaves together Aztec myths, indigenous world views, Mexican culture, and U.S. industry in a visual tour-de-force that delights, challenges, and provokes. The art is both accessible and profound. You can enjoy it for an afternoon or intensely study it for a lifetime with a sense of constant discovery.

Roberta Smith points out that the murals “form an unusually explicit, site-specific expression of the reciprocal bond between an art museum and its urban setting” (Smith, 2015). Over time, the frescoes have emerged as a visible and vital part of the city, becoming part of Detroit’s DNA. Rivera’s art has been both witness to and, more recently, a participant in history. When he began the project in late spring 1932, Detroit was tottering at the edge of insolvency, and 80 years later, the murals witnessed the city skidding into the largest municipal bankruptcy in history in 2013. A deep appreciation for the murals and their close identification with the spirit and hope of Detroit may have contributed to saving the museum this second time around.

I still vividly remember my own reaction when I first saw the murals. As a young boy, the Rouge, the auto industry, and Detroit seemed to course through our lives. My grandfather Philip Chapman, who was hired at Ford’s Highland Park plant in 1914, wound up spending most of his working life on the line at the Rouge. As a young boy, I watched my grandmother Sophie pack his lunch and fill his thermos with hot coffee before dawn as he hurried to catch the first of three buses that would take him to the plant. When my father, Max, came to Detroit three decades later in the mid-1940s to marry my mother, Rose — they had met on a subway while she was visiting New York City, where he lived — he worked on the line at a Chrysler plant on Jefferson Avenue.

One weekend, when I was 10 or 11 years old, my father took me to see the murals. He drove our 1950 Ford down Woodward Avenue, a broad avenue that bisected the city from the Detroit River to its northern border at Eight Mile Road. Woodward seemed like the main street of the world at the time; large department stores — Hudson’s was second only to Macy’s in size and splendor — restaurants, movie theaters, and office buildings lined both sides of the street north from the river. Detroit had the highest per capita income in the country, a palpable economic power seen in the scale of the factories and the seemingly endless numbers of trucks rumbling across the city to transport parts between factories and finished vehicles to dealers.

We walked up terraced white steps to the main entrance of the Detroit Institute of Arts, an imposing Beaux-Arts building constructed with Vermont marble in what had become the city’s cultural center. As we entered the building, the sounds of the city disappeared. We strolled the gleaming marble floors of the Great Hall, a long gallery topped far above by a beautiful curved ceiling with light flowing through large windows. Imposing suits of medieval armor stood guard in glass cases on either side of us as we crossed the Hall, passed under an arch, and entered a majestic courtyard.

We found ourselves in what is now called the Rivera Court, surrounded on all sides by the “Detroit Industry” murals. The impact was startling. We weren’t simply observing the frescoes, we were enveloped by them. It was a moment of wonder as we looked around at what Rivera had created. Linda Downs captured the feeling: “Rivera Court has become the sanctuary of the Detroit Institute of Arts, a ‘sacred’ place dedicated to images of workers and technology” (Downs, 1999:65). I couldn’t have articulated this sentiment then, but I certainly felt it.

The size, scale, form, pulsing activity, and brilliant color of the paintings deeply impressed me. I saw for the first time where my grandfather went every morning before dawn and why he looked so drawn every night when he came home just before dinner. Many years later, I began to appreciate the art in a much deeper way, but the thrill of walking into the Rivera Court on that first visit has never left. I came to realize that an indelible dimension of great art is a sense of constant discovery and rediscovery. The murals captured the spirit of Detroit then and provide relevance and insight for the times we live in today.

Beal points out that Rivera “worked in a heroic, realist style that was easily graspable” (Beal, 2010:35). A casual viewer, whether a schoolboy or an autoworker from Detroit or a tourist from France, can enjoy the art, yet there is no limit to engaging the frescoes on many deeper levels. In contrast, “throughout Western history, visual art has often been the domain of the educated or moneyed elite,” Jillian Steinhauer wrote in the New York Times. “Even when artists like Gustave Courbet broke new ground by depicting working-class people, the art itself still wasn’t meant for them” (Steinhauer, 2019). Rivera upended this paradigm and sought to paint public art for workers as well as elites on the walls of public buildings. By putting these murals at the center of a great museum in the 1930s through the efforts of Wilhelm Valentiner and Edsel Ford — and more recently, under Graham Beal and the current director Salvador Salort-Pons — the Detroit Institute of Arts opened itself and the murals to new Detroit populations. Detroit is now 80-percent African American, the metropolitan area has the highest number of Arab Americans in the United States, and the Latino population is much larger than when Rivera painted, yet the murals retain their allure and meaning for new generations.

Upon entering the Rivera Court, the viewer confronts two monumental murals facing each other on the north and south walls. The murals not only define the courtyard, they draw you into the engine and assembly lines deep inside the Rouge. The factory explodes with cacophonous activity. The production process is a throbbing, interconnected set of industrial activities. Intense heat, giant machines, flaming metal, light, darkness, and constant movement all converge. Undulating steel rail conveyors carry parts overhead. There were 120 miles of conveyors in the Rouge at the time; they linked all aspects of production and provide a thematic unity to the mural. And even though he’s portraying a production process in Detroit, Rivera’s deep appreciation of Mexican culture and heritage infuses the frescoes. An Aztec cosmology of the underworld and the heavens runs in long panels spanning the top of the main murals and similar imagery appears throughout the frescoes.

On the north wall, a tightly packed engine assembly line, with workers laboring on both sides, is flanked by two huge machine tools — 20 feet or so high — machining the famed Ford V8 engine blocks. Workers in the foreground strain to move heavy cast-iron engine blocks; muscles bulge, bodies tilt, shoulders pull in disciplined movement. These workers are not anonymous. At the center foreground of the north wall, with his head almost touching a giant spindle machine, is Paul Boatin, an assistant to Rivera who spent his working life at the Rouge. He would go on to become a United Auto Workers (UAW) organizer and union leader. Boatin had been present at the Ford Hunger March on that disastrous day in March 1932 and still choked up talking about it many decades later in an interview in the film The Great Depression (1990).

In the foreground, leaning back and pulling an engine block with a white fedora on his head may have been Antonio Martínez, an immigrant from Mexico and the grandfather of Louis Aguilar. A reporter for the Detroit News, Aguilar describes how fierce, at times ugly, pressures during the Great Depression forced many Mexicans to leave Detroit and return to their homeland. The city’s Mexican population plummeted from 15,000 at the beginning of the 1930s to 2,000 at the end of the decade. If the figure in the mural is not his grandfather, Aguilar writes “let every Latino who had family in Detroit around 1932 and 1933 declare him as their own” (Aguilar, 2018).

A giant blast furnace spewing molten metal reigns above the engine production, which bears a striking resemblance to a Charles Sheeler photo of one of the five Rouge blast furnaces. The flames are so intense, and the men so red, you can almost feel the heat. In fact, the process is truly volcanic and symbolic of the turbulent terrain of Mexico itself. It brings to mind Popocatépetl, the still-active 18,000-foot volcano rising to the skies near Mexico City. To the left, above the engine block line, green-tinted workers labor in a foundry, one of the dirtiest, most unhealthy, most dangerous jobs. Meanwhile, a tour group observes the process. Among them in a black bowler hat is Diego Rivera himself.

On the south wall, workers toil on the final assembly line just before the critical “body drop,” where the body of a Model B Ford is lowered to be bolted quickly to the car frame on a moving assembly line below. Once again, through his perspective Rivera draws you into the line. A huge stamping press to the right forms fenders from sheets of steel like those produced in the Rouge facilities. Unlike most of the other machines Rivera portrays, which are state of the art, this press is an older model, selected because of its stylized resemblance to an ancient sculpture of Coatlicue, the Aztec goddess of life and death (Beale, 2010:41; Downs, 1999:140, 144).

On the left is another larger tour group, which includes a priest and Dick Tracy, a classic cartoon character of the era. The Katzenjammer Kids — more comic icons of the time — are leaning on the wall watching the assembly line move. The eyes of most of the visitors seem closed, as if they were physically present, but not seeing the intense, occasionally brutal, activity before them. Rivera, in effect, is giving us a few winks and a nod with cartoon characters and unobservant tourists.

~

Harley Shaiken · Fall 2019.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Umbrella Academy, S2

I was pretty underwhelmed by the first season of The Umbrella Academy, and if it weren’t high summer with hardly any new TV to be seen, I might not have bothered with the second one. But to my surprise, season 2 of The Umbrella Academy is a massive - and, to my eyes, deliberate - improvement on the first. It’s not great TV by any stretch, but it’s engaging and fun to watch, and you find yourself caring about the characters and wanting to follow along with their story, all things that the dour first season failed to achieve.

My fundamental problem with the first season of The Umbrella Academy is that the show failed to convince me that its core family was worth saving. The basic premise of the show - seven superpowered children raised by an abusive tyrant who saw them purely as instruments to be deployed, and played psychological games intended to grind down their independence and prevent any chance of their feeling a stronger loyalty to one another than to him - is obviously a rich and evocative one (albeit also one that requires a depth and complexity of writing that very few superhero shows evince). But the premise of the first season - the surviving Hargreeves children, reunited at their father’s funeral, have to find a way to overcome their differences and move past their difficult upbringing or the world will literally end - kept bumping up against the simple fact that I didn’t want this family to endure. The Hargreeves were so mean to one another, and seemed to have so little affection for each other, that I couldn’t make myself believe they wouldn’t be better off just going their separate ways.

The show itself seemed to realize this, because it ended the first season with the Hargreeves’ dysfunction and inability to honestly address how badly they’d mistreated one another ultimately being the cause of the apocalypse, and with the siblings deciding that their only possible course of action was to reset their lives and rebuild their relationships from the ground up. It was the show tacitly admitting that the Hargreeves family was unsalvageable, and while that’s a bold storytelling choice, the writing just wasn’t there to support it. I finished the first season feeling rather fatigued with both the story and the characters, and uninterested in watching them relive their lives.

The second season feels like a soft reboot of that premise. The trip through time on which the first season ended is retconned - instead of sending their consciousnesses back to their childhood selves, the Hargreeves instead end up as their own adult versions in the early 1960s. The apocalypse they fled 2019 to avoid and were hoping to prevent by reliving their childhoods and repairing their relationships from first principles is essentially forgotten. Instead the Hargreeves focus on preventing a different, new apocalypse scheduled for November 25th 1963, and once they succeed at that, 2019 is altered in unspecified ways that prevent the end of the world from happening.

Most importantly, the Hargreeves suddenly feel like a family. A dysfunctional family, to be sure, whose members have to figure out how to relate to one another now that the abuser who shaped and poisoned their relationships is finally gone. But there is a suddenly a lot of affection between the siblings, even if most of it is expressed through teasing and needling at one another’s weaknesses. In S1, the Hargreeves felt like people who genuinely had no interest in knowing one another. In S2, they feel like people who don’t know how to relate to each other, but want to figure it out.

You see this in a lot of other things that the second season does to respond to frequently-voiced complaints about the first season. In S1, everyone hated how domineering Luther was and how badly he treated Vanya, so almost the first thing he does in S2 is apologize to her for his failings as a brother, and acknowledge that a large portion of the fault for her breakdown falls on him. Everyone was a bit weirded out by the Luther/Alison ship, so it gets barely any play in S1 (though with a bone thrown to the shippers right at the end). Everyone was charmed by Klaus and Diego, so they both get major storylines (and Diego, in particular, is softened and made more vulnerable, the better to take advantage of David Castañeda’s charisma). Everyone wanted more of Ben, so he becomes more vocal and even gets to interact with characters besides Klaus. Everyone got tired of Alison namechecking a daughter that we had no intrest in, so she barely comes up even though Alison is not only separated from her by a distance of sixty years, but last saw her in a world that was being destroyed by a meteor impact. And everyone came away from the first season saying “no way Vanya is straight”, and lo, she is not straight.

It’s an approach that you see in other Netflix shows - Stranger Things, in particular, is practically defined by its responsiveness to audience complaints, with each season overcorrecting in the direction of whatever reaction was most loudly expressed over the previous one. Ideally, you’d want showrunners to have a strong enough sense of their characters, story, and world that they don’t need the audience to function as a cowriter, but in the case of The Umbrella Academy, these changes are mostly to the good. I might have liked the darker story the show seemed to be telling in the first season, about a group of abused children who genuinely don’t like each other but also can’t relate to anyone outside of their family, but the writing wasn’t there for it. The lighter, softer version of The Umbrella Academy delivered by S2 actually works, so the show should stick with it.

It certainly helps that the second season shoulders several topics that I wouldn’t have expected the show to be able to address with any amount of grace. I have to admit that I cringed when I realized that Alison, trapped in the South in the early 60s, had joined the civil rights movement, because superhero stories do not have a great track record dealing with social justice, much less real-world movements. But the handling of this issue ends up being smarter and more effective than I could ever have hoped. It’s still a side-story to the main event of preventing the end of the world, but in the scenes and episodes that do place it front and center, the show is unflinching. The depiction of the lunch counter protest that Alison and her group organize, and of the vicious hostility they encounter for such a small, simple demand, is unsparing. It establishes both the depth of the hatred and violence that the protest arouses, and the impossibility of resisting “peacefully” against a system the views any assertion of your humanity as an act of violence.

I was also a bit concerned over the placement of Alison, in particular, at the center of a story like this. Obviously, as the only black member of the Hargreeves family, her experience in the 1960s would be unique, but she’s also a character who has been established as being too powerful for her own good, and having abused her power in order to dehumanize others. Placing her in a situation where she is being dehumanized because of her race felt like creating a fruitless tension, where Alison might feel reluctant to use her powers despite the fact that she is all-but powerless against the greater system of white supremacy. But again, the season manages to thread the needle, showing both the allure and the limitations of Alison’s mind control abiliites in the context of Jim Crow. I didn’t love the implication that Alison would almost immediately start misusing her powers once she decided to use them to open doors that racism had closed to her, but the show also makes it clear that her anger is justified, and her targets deserving.

By the same token, I heaved a great sigh when the season introduced Harlan and I realized that he was neuroatypical, because it felt almost inevitable that some aspect of the strangeness that follows the Hargreeves around would result in him being “cured”. But that didn’t happen! The season treats Harlan like a valuable and loved person who doesn’t need to become more “normal” for his life to be worth living. And though he does end up needing to be cured, it’s not of his autism, but of whatever Vanya does to him when she saves his life. I kept expecting the the moment when Harlan would turn to his mother and start speaking, and the fact that the season kept refusing to go there feels almost miraculous.

So yeah, the whole thing feels like a breath of fresh air, and as if the people at the helm are thinking a lot more deeply about their story, what works in it and what needs to be changed for it to work, than I would have said at the end of the first season. It’s still not an amazing story (part of the reason we’re able to spend so much time on subplots like Vanya’s romance with Sissy, Klaus’s cult adventures, Alison’s activism, or Diego and his conflicted relationship with Lila, is that the spine of the season is fairly perfunctory) but it does enough with the characters that I found myself genuinely interested in their relationships and eager to see how they would develop. I’m not used to shows rebuilding themselves like this, and it’s refreshing to see that even in the streaming era, that can still happen.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Humanity and Fellow Allies of the Black Lives Matter Movement,

I understand that things may feel scary and overwhelming right now, but for privileged members of society, the responsibility now more than ever, is to be an ally. Now is the time to get involved in any way you can, whether in the streets or from your home. As our continued actions manifest changes within law enforcement and government structures, we must not forget to include the change needed within our society as well. Although the bravery many are currently showing, and the sustained and strong efforts of those partaking in the movement is incredible, it does not change the minds of those who are not currently with us. We must also focus our efforts to sustain the changes we are seeing and to ensure a lasting legacy of toppling white supremacy.

Race is a social construct. What this really means, is that no one is born racist. Racism is taught, whether in the home or though the media and systems in place to keep certain members of our society in power. It is not enough to dismantle institutionalized racism if individuals within society still do not understand the pain and suffering it has caused. To unite and raise up all of humanity, we must focus not just on those who are most disenfranchised, but on those who lack education and understanding of the world’s power structures. With understanding we can achieve momentum and lasting change.

Just as we teach our children the importance of treating everyone equally, we must offer the same courtesy to those adults who were not afforded this same service as children. It is not always obvious to those who benefit from systemic racism the privilege they are afforded. And it is not always their fault. It is the fault of an underfunded and white washed public education system that serves to further the convenient and comfortable narrative of the white suppressors and their pillaging of what is now the United States.

It is difficult for anyone to admit they are wrong, or don’t understand, and it is even scarier to admit to benefiting from another's pain, even unconsciously. People are afraid of change, it is uncomfortable. But that does not mean that change is bad. For this, we must work to educate others from a place of compassion rather than anger. Those who do not understand systemic racism are also products of a broken system that can only be dismantled when people truly understand its foundations and flaws. There is no excuse for hate, and racism should not be tolerated, but please I urge everyone who already agrees with me to greet others with compassion and courage. It is only through open dialogue and honest conversation that minds can be changed and communities strengthened. We must never tolerate racism but we must also never tolerate ignorance that leads to hate.

Be strong in your sense of justice and equality for all. And be strong in educating others to the pains and horrors perpetrated by a racist system. Understand that change takes time. Those who are learning need time to process new information and work towards changing their scope and principles. The space granted to another to reeducate themself must not be confused with complacency. Patience should only be granted only to those actively working to understand their privilege and the foundations of white supremacy that the US was founded on. It must ultimately be understood that it could, sadly, take generations to undo the damage caused by an entire world history built on the backs of others. To those who are suffering, this is far too long. We all owe it to humanity to work to better ourselves and the society we live in.

Black Lives Matter. If you agree with this statement but are white and don’t believe yourself to be part of the problem; that is the problem. Whiteness as superiority has been so deeply embedded into every institution within American Society, the message may go easily unnoticed by those without Black and Brown bodies. It is a responsibility to learn about systemic oppression and injustices and understand how we may benefit so we can effect change. It is powerful to be able to admit when we do not understand and it is even more courageous to admit the understanding to oneself and to others, that they may have benefited from another’s pain. The real power is in people learning the truth and working to understand the true history of genocide and slave labor that the US is built on. Let us use education to reframe racist points of view and create a community where the safety and prosperity of all is at the forefront.

With love, compassion, and understanding,

BummerBetch

#open letter#black lives matter#reeducate#protect black and brown bodies#dismantel systemic racism#stop white washing history#be an ally#educate yourselves#be compassionate#practice compassion#end white supremacy#use your privilege#betcheducation#bummerbetch

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Nice White Parents” - Podcast Review and Thoughts on Allies and Perception

“Whenever people have asked me podcast recommendations this year, I’ve been forced to admit that I “don’t listen to serious podcasts anymore.” I really just couldn’t handle it.

However, I’m also a woman of simple tastes: I see something new in the “Serial” feed, I listen to it.

“Nice White Parents” by Chana Joffe-Walt (spelled nothing like how she says it on her podcast 😅) is not a “Serial” podcast, but it is investigative, illuminating, and infuriating in its own way. I spent some time this summer attempting to find and listen to podcasts about social justice, racial inequity, and BLM, yet most were disappointing or not as educational as I had hoped they’d be. In contrast, I found “Nice White Parents” fascinating and relatable.

Because, of course, I have “nice white parents” who were afraid of sending me to the “wrong” public school. And, thanks to the decisions they made for my education and me, I was able to spend a year working at one of those “bad schools.”

The focal point of “Nice White Parents” is the School for International Studies, a public middle school in New York. It had several names as it went through several massive changes in how it was viewed by its community. It has gone from failing and in threat of closing, to housing two separate “schools” within it, to being the “hot” school to attend, before finally becoming a potential blueprint for how to integrate a school. The driver of a lot of these changes were the titular “nice white parents,” and the history detailed in this limited series was a surprising deconstruction of school segregation and the role of white or privileged allies in social movements.

A key theme I’d like to hone in on is perception: how do people perceive the schools in their communities? How do they perceive the role of public schools in our society? How do parents perceive what is best for their kids? And how do they perceive themselves as proponents for racial equity or as perpetrators of an unequal system?

In this podcast, when (white) parents judged the South as being “backwards” because of segregation, they wrote letters to the school board championing integration. Yet, when it came down to it, many ended up perceiving the diverse schools as not being able to provide a quality education to their children. When they perceived that their local school was still not good enough, they sought to open new (integrated?) ones or develop new programs--such as the French program detailed in the first episode. And, when those programs end up being mostly white they don’t really see it as “segregation” until it’s put in explicitly racial terms.

At the same time, there was little concern for how their actions were perceived by the non-white community members. One particularly poignant moment was the interview with a Latina mom in the final episode who just wanted her school to be less crowded. Instead, the meeting she attended was solely focused on “diversity” and “equity”: what the white parents perceived as most important.

There were a few weeks this year when I made an effort to “educate” myself: I listened to “Codeswitch,” “Silence is Not an Option”, and “Reply All”, read NK Jemisin, Jacqueline Woodson, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and had discussion groups--with nearly all white participants. I’m not saying that listening to and reading BIPOC voices isn’t helpful and important to understanding and participating in this movement, yet I think it’s also equally important for allies to be critical of what that “allyship” actually means to us.

I’ve struggled with my role as an ally in the past. As I alluded to, I served a year with AmeriCorps at a high school that was probably 50% black and 50% Latinx. A major part of our training, maybe even more so than how to teach, was how to practice empathy, how to recognize systemic racism in our country and schools, and, most importantly for me, how to be an ally. It was far from easy. (And that’s not even getting into whether being Jewish means I’m white or not... and this blog post has rambled on long enough!)

I have put my money where my mouth is--I spent ten months working in that school--but I can’t shake the nagging little itch that someday when I have kids, I’ll take a look at a school like the one I worked at and another like the one I graduated from and most likely choose the latter, just as my parents did when they chose to send me to a private school for kindergarten through eighth grade.

At the same time, I know that that’s many, many years down the line, and I know that things change. That middle school my parents were so reluctant for me to attend was the one my sister graduated from! I wonder what it was that changed their perspective? What will it take to change mine?

"Nice White Parents"

https://www.podcastrepublic.net/podcast/1524080195

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I took this from my Facebook: I'm in a mood this morning so let's go and cover a few things! Now, I'm not black, so I may not be the most clear and concise about some of it, but damnit I'm gonna do my best on the points involving race. Also, if any of this offends you or some shit, don't even open your mouth, I don't have the patience to deal with you, stay quiet and ignore my page, or maybe even better yet, unfriend me!

White privilege: White privilege is real. I'll admit, there was a time a few years ago, I didn't think it was and I didn't understand what people meant when they said it. but now I do. and it's a real fucking thing. people need to grow up and shut the fuck up with their whining. we do have privilege just based off our skin and that needs to be recognized. We need to use that privilege to fight back and support the black community. if we don't use that privilege we are no better than the cops and others who abuse their power because we are staying silent while they do it. Silence only lends itself to the oppresser. Now, you may ask after reading that, what is white privilege? "White privilege refers to societal privilege that benefits white people over non-white people in some societies, particularly if they are otherwise under the same social, political, or economic circumstances." The most relevant example of this right now? Not having to fear for your life just because of your skin color when you get pulled over or stopped by cops.

Black lives matter: Now, I've seen some of y'all say "but all lives matter!" ...shut the fuck up. No one ever said they didn't, they're saying that black lives DO matter. All lives won't matter until ALL lives matter, and right now black lives espcially don't matter to a good amount people, which is why people are fighting to make them matter as they should. As the example that's been going around lately, take houses. Oh yes, all houses are important, but if one of them is on fire, it kinda makes sense for the firefighters to put out the fire at that house instead of spraying down all the houses, right? Some of you want to be oppressed so badly you scream "all lives matter!" or "straight pride!" (as another example). Be fucking thankful you don't need a movement just to be treated as a human being based on your skin. And it's not just about George anymore. He was the spark, the shot heard round the world this time. It's about all the black lives lost, it's about the years of racism, it's about the affects of slavery and segregation we still see today, it's about so much more.

Protests vs riots vs looting: Not all these people are the same. Protesting is included in our FIRST amendment, meaning that when the founding fathers were thinking of what they wanted, that's what they thought of first and as being the most important. The protesters now are marching for black lives and other things such as police reform. Many (most) of them are trying to stay peaceful! It's so widespread now because it's been ignored and shoved down before. So now they're taking to the big cities in mass, making it so they are HEARD! You wanna say they're inconvincing people or shit, well good. That's the point. Protests, even when peaceful, aren't meant to be comfortable. They are there to get a message across. Now, there's been cases of the protests turning into riots. Occasionally it has been started by the protesters. And that's because they're angry, and fed up with not being heard. I'll pull out an analogy a good chunk of y'all will understand, even if it's fictional. Remember in Hunger Games, when Katniss put flowers around Rues body, and District 11 started to riot? It's like that. These people are angry, tired, frustrated, and hurt, and they've been ignored when they've tried to be peaceful, so now they're doing what they KNOW will get attention. But despite this, most of the riots aren't started by protestors, especially POC ones. No, most of them are started by white people getting big heads and wanting to say "FUCK DA POLICE/AUTHORITY" or even the cops themselves. Most people that start destroying property are white, and usually black people try and stop them from doing it. And then you have the cops. Destroying medical supplies, firing rubber bullets and tear gasat peaceful protesters, physically pushing them, etc even when they have NO reason to. And before you cite MLKs peaceful protests, many of those ended with the cops setting dogs on the protesters or spraying with fire hoses or beating them with batons. And this leads to riots because it riles people up, they get even angrier. And then you have the looters. Most looters aren't even with the protests, and instead are trailing behind them to loot stores because they know the protesters will get the blame. Oh, and cops have been documented looting too.

Cops: now, this one is really touchy, but let's go and I'll try and articulate it best I can. There can be cops that do good for their community, have good intentions at heart, but here's the thing. Our justice system, especially the cop part, is corrupt in one way or another, and has many flaws. It needs fixed. These people may join with good intentions, but they are joininga system that is inherently bad. And before y'all want to try and start shit with me over this, I just took a semester long class over this. The system has racism ingrained into it's core, even if people don't realize it. That's why the current system needs dismantled and a new one that will actually do good needs put in place. There's so so so much that ties into it, such as better mental health treatments, community outreach programs, and more. With the current system, cops are not meant to help people, but rather control them, even if they don't realize it. Do you know why we have so many shows about cops? Have you ever heard of Dragnet? Dragnet was originally started to show the cops in a good light because people were not happy with cops, so they started making propaganda, yes, that's what it truly is, to make the cops look good, to make them out to be these pillars of righteousness and whatnot so they could start getting the public on their side. And thus the long and still strong tradition of cop shows are around, whether it be reality TV like Cops, or complete fiction like Law & Order. And even if these shows do make steps to address shortcomings of the police system, their roots are still in propaganda. Circling back, you also have the cops that stand by and do nothing. As I said earlier, silence lends itself to the oppresser, and when cops don't speak up, they are doing the same.

Children (and pets/animals) at protests: Here's the thing. people bringing their kids and pets are more than likely bringing them to PEACEFUL protests. Now you may say, "well they should know it could turn violent!" ...It's called a peaceful protest for a REASON. Ok, let's say it does turn violent? Cops are still directly targeting children. And even if they aren't, they see the kids, and instead of rethinking what they're about to do, they still do it, they still mace and tear gas those kids. And guess what? Some of them aren't even with the protests! some of the kids that have been maced and tear gassed have been with their BYSTANDER parents as they have to pass through the area to get to their homes or wherever. like the little girl whose mom was driving them somewhere and they got caught in tear gas the police had been throwing, and were gassed out of their car. as the mom was trying to take care of her daughter a cop came up to them. the mom said (screamed) "she's just three" multiple times, and that they weren't at the protest, just trying to get home, and despite that, the cop looked directly at the little girl and then threw the canister directly at her, causing it to blow up in her face. And the police animals. I agree, those animals should not be subjected to pain. It is not their choice to be there, they don't know what they're doing, they're just doing as trained. I've seen people get more upset about the police animals than I have kids, and you cry that parents choose to bring their kids. Well, cops are choosing to bring their animals. Neither kids nor animals on either side should be getting hurt, hell, no one should, the protests are meant to stay peaceful.

Protesters going missing and other things: Multiple protestors have magically "disappeared", unlawfully arrested, or detained without food, water, etc. and who knows what else. This should not be happening. These people aren't just disappearing, they shouldn't have to fear for basic rights or even for their fucking lives when exercising their first amendment right. Curfews have been a big issue. A curfew will be announced just a few minutes before, or get changed so people get caught outside with no where to go, thus getting arrested. Or like in Chicago, where the bridges were raised so they had no way to leave. Or other places where they are blocked in so they technically violate curfew. Or places where protesters are told to clear out or they'll get arrested, and instead of giving them time to leave, they start arresting them right away. Or what about when people are sitting there, just trying to talk to the police, hands up, and are still arrested?

There's so much more I could say, but I do want to leave off with this. So many ask why young people are so involved with this. we have been raised on a diet of Hunger Games, Divergent, Avatar: The Last Air Bender, Harry Potter, Steven Universe, and so much more. We have been taught to fight back injustice and oppression, to make our voices be heard and to help make others voices be heard. We have been raised by parents to speak out and defend ourselves. We have already lived through pain and suffering in our short lives, and we are tired of it. So we are damn sure going to fight back and try to make this shitty little world even a tiny bit better for whoever we can. We are told this is the land of the free, and that we can be whoever we please and get to live our lives as we see fit, and damnit, we are going to make that happen for ALL of us.

#blacklivesmatter#black lives fucking matter#black lives count#black lives have always mattered#black lives are important#black lives matter#black lives have value#black lives movement#justice for george floyd#justice for floyd#blm movement#blm protests#protest

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Some of the early southern American police forces were born out of slave patrols. In other parts of the country, groups of men were hired to protect the property of the wealthy. After the Civil War during Reconstruction, many local sheriffs maintained a similar function to the slave patrols through their enforcement of segregation and disenfranchisement of previously enslaved Africans. Enforcement started out and continues to predominantly be about protecting wealthy and white comfort at the expense of the lives of Black and Brown folks.

The invention of the automobile represented a new threat to public safety, with the first US automobile fatality taking place as early as 1899. Regulations were needed to prevent reckless driving, and police began enforcing speed limits and other safety laws.

“Policing the roads was always about more than just public safety. It was about the exercise of various types of power: local power, racial power, and making money.” —Cotton Seiler, author of Republic of Drivers: A Cultural History of Automobility in America.

The over-reliance on police for traffic enforcement in the US has a serious impact on freedom of mobility for Black and Brown people.

In the modern era, researchers at Stanford University analyzed data from close to 100 million traffic stops between 2011 and 2017 and found Black drivers were more likely to be pulled over and have their car searched than white drivers, which the researchers stated was evidence of systemic racial profiling. Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islander Americans are also disproportionately stopped while driving, which in many cases can lead to arrest and deportation. According to the US Burea vu of Justice, the traffic stop is the most common interaction between US residents and police officers. It is understandable that members of these these communities may feel distrust and uncertainty when interacting with law enforcement.

the chicago tribune, 17.03.17 reported that the police department was writing exponentially more bike tickets in black neighborhoods than majority-white ones.

“Oboi Reed form the mobility justice nonprofit Equiticity said that when he first started organizing community bike rides in predominantly Black and Brown lower-income neighborhoods, he heard from young people that they didn’t ride their bikes because they felt they were being targeted by the police. That was a new concept to him at the time, but he took their word for it. He added that when he shared the youths’ concerns with mainstream transportation advocates and Chicago Department of Transportation officials, often the response was disbelief—people didn’t believe the police were actually guilty of profiling cyclists of color. But years later the Tribune data proved that officers were, in fact, writing exponentially more bike tickets in communities of color, and a police spokesperson eventually admitted that this was due to bike enforcement being used a pretext to conduct searches in high-crime areas.

“The vast majority [of the contact] that BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and People of Color] folks have with the police is in the act of exercising our human right to mobility….The vehicles of mobility are our sidewalks, trains, buses, and vehicles that are a major part of our cities. That’s where the collision happens.”

That’s a harmful situation because people require mobility for improved educational opportunities, job opportunities, opportunities to improve their health, etc. “When our mobility is restricted, any number of life outcomes become constricted. The nature of policing in [Chicago] is to constrict our movement.” He referenced slave patrols as “the foundation of policing.”

“I always think about mobility justice literally being the intersection and the arteries of every social justice movement,” Río Oxas said. “It’s how we get to school, work, the clinic, our friends, the mountains, the ocean. That’s mobility justice.””

read more: chi.streetsblog, 14.12.2020.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Photo credit: Julio Cortez/AP

George Floyd's fiance pleads against the violent protests: https://www.thedailybeast.com/george-floyds-fiancee-pleads-…

YES, racism is alive and well. So is sexism, rape culture, and homophobia, but you don't see the Me Too movement hurting people and destroying property...

YES, George Floyd was murdered. But this goes far beyond racism. I never deny racism, the recent murder of a black man by two white guys in a pickup was clearly racist. But this is an issue of MEN. And POLICE. Cops have always killed people, it's all a matter of what gets the most publicity. I see a photo collage going around of black people that have been shot recently by cops and I find it offensive. Where are the white, Asian, and Hispanics that have also been shot by the police? What about the recent shooting of a white woman? We are all equals, right? https://apnews.com/57b423dcf5e54bdb801d7ea564416a0a

Foolish liberal hypocrisy. Meanwhile I am seeing younger democratic socialists applauding the looting as capitalism being put in its place. What the hell? You see the first article above, George Floyd's loved one said he never wanted this. And what exactly is the relevance to his death? What did Target stores do to George Floyd? How is the guy walking down the street with a backpack of stolen liquor bottles contributing to justice?

This is bullshit of the greedy and the brainwashed, race issues and social topics have been long lost. The majority of the protesters seem to be males enjoying violence. Which again, is what it comes down to.

While a huge feminist, I have no problem admitting that men have their own separate laundry list of issues. Difficulty speaking out, and difficulty getting help for whatever problems they may have because of the stigma of society where men are still not allowed to admit "weakness." I see it in my own father who has outbursts from being overwhelmed by various things. Having to be a tough guy and a financial supporter to a disabled wife but unable to accept or seek support himself.

There are A LOT of angry men out there. Shit, they're justified for the most part! I would definitely not want to be a man. And that is where the position of authority comes in... overcoming your struggles as a male youth and becoming a cop or correctional officer.

There are so many great cops out there! But, I haven't met many of them. Because not everyone overcomes their past and becomes a good cop. Whatever they grew up with or were born with makes them relish power, control, and violence.

I, a lower class (former middle class) white woman, have been victimized by the police. If you think that's a fucking joke because I'm white, refer back to the original point: POLICE VICTIMIZE PEOPLE OF ALL AGES, RACES, GENDERS, ETC.

A few years ago I read an article about a rapist cop. He raped more than one woman, but when they reported it, they were dismissed because he was a cop. His peers made sure he was above the law. So then he rapes an older black woman, someone's grandmother. She raised hell and he finally got in trouble. Was she listened to because she was black? HELL TO THE NO, women are treated like shit. A black woman? I've seen black women treated horribly my entire life. It's just how it is.

But no one felt like bringing this pig to justice, because, well, white male cop. Cops obviously deal with criminals and folks they will naturally regard as lower class, and none of these folks are going to be believed over a cop. From dating men of questionable backgrounds, I have heard horror stories of prisoners being beaten by cops and correctional officers and all kinds of shit. But who is going to believe some felon over a police officer?

May marked the 4 year anniversary of my ex-boyfriend almost killing me. It was hell, I struggled all month. My mom having cancer, the anniversary, the pandemic, now everyone running around setting shit on fire because they want free TVs... HOLY FUCK. PTSD trigger much?

I've wanted to talk about that, but I felt I couldn't, because, well, he's stalked me since. How did this happen? People think I was a battered woman but that's not true. Women stay with abusive partners and I did not. I got with this guy knowing he had a record, as others before him, but did not expect the onslaught of mental illness. The guy before him was bipolar and would shut down, lay on the bed and just be totally mute or sob. This new guy, after about 3 months into a relationship, would have manic episodes that would lead to suicide attempts. Over time I found out that he was a diagnosed bipolar, and rumored (unconfirmed) schizophrenic. I begged and begged for him to stick to taking meds, which clearly helped over the course of months, but he would stop taking them because he felt he "didn't need them," which is the cruelest cliche of the mentally ill and why so many don't function at all.

So I ended up having to call the cops on him multiple times in the course of 3 years when he lost his shit. Not once did he ever harm me, although you can see, and I can see, now, that it was unhealthy and dangerous for everyone involved regardless. The first time I dealt with the cops over him was when he got a DUI in my truck with his friend. but the friend was driving. I woke up at midnight to this chaos and remember a black female cop intimidating me and screaming at me because I was standing near a beer bottle on the ground and I was "hiding evidence." Which was bullshit since the driver had already been arrested. Who the fuck cares about a random Bud Light bottle lying in my yard? The DUI was in Ocean City. Whatever.

The same fucking night my shitfaced, manic boyfriend logs onto my computer and reads like 7 years worth of texts between me and a male friend, accusing me of fucking him. After a long night of dealing with the other drama it was like hell never ended. He's on my computer, looking at everything I have and accusing me of cheating. Never met the dude, never tried to be with the dude, but that seemed pretty moot. Even if your partner has nothing to hide, you shouldn't be going through their shit. IF YOU DO NOT TRUST THE PERSON YOU ARE WITH, LEAVE THEM. IF YOU HAVE ONGOING ISSUES WITH MANIA OR PARANOIA, GET HELP.

Well, perhaps I seem a hypocrite in protesting violence against women, and I did something I'm not proud of: I punched the fuck out of him. He then got up and put my shotgun in his mouth. He didn't pull the trigger but obviously that scarred me for life. I called 911 and they chased him down in the woods and took him to the mental ward in Salisbury. I dealt with 3 male cops that were kind to me and said I did the right thing by hiding the gun afterward and calling 911. My neighbor also helped me, which I am incredibly grateful for.

I should have left, hands down. But because I never felt physically threatened by him: I felt I was helping him, he could get better, and I kept trying. I have never been a woman that wanted a "project" as some people want, where they find someone to fix or better as a person. But I loved this man and tried my best, stupid as I was.

He was fine for months after that, another huge factor in me staying. We were just boyfriend and girlfriend, enjoying life, until he had another manic episode. Once he went 6 months with no signs of anything at all. Again, at this point in things, I have nothing to candycoat in my life. I am an open book, and in 2018, came out about being raped by a man in 2011, and got judged harshly. I've had to accept that no matter what I say, I will be questioned and put down because that is how victims are treated.

So in 2015 he came home late at night, screaming the FBI were in the bushes and smashing things. He accused me and a family member of conspiring with the government against him and stripped half of his clothes off, threatening to kill himself. Just like that, he would go from a calm person that worked all day to a raging maniac in the most literal form.