#Nesbit

Text

Moore and Nesbit

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me when my dumb little post hits 10k notes

#tumblr#tumblr notes#thank you#10k#ty#op#one piece#chopper#tony tony chopper#nesbit#seriously though#thank you so much#thank you for intoxicating me with attention

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

cast your mutuals as ofmd characters!

So i was asleep... But y'all seem to want this soo-

*cracks fingers*

Stede: @not-nervous-jester @taikaverse and @stedebonnets

Ed: @batsarebetterthanpeople and @ipomoea-batatas

Lucius: @mxmollusca and @jellybeanium124

Pete: @stabbedbyjim (mainly the URL I think Pete is most likely to get stabbed by Jim)

Olu: @meanmisscharles (fandom parent <3) @ella-doe

Jim: @leatherdaddyteach

Frenchie: @blakbonnet and @saltpepperbeard ... and @neine

Roach: @snake-snack-stede and @flightoftheconnie

Wee John: I know we aren't mutuals but I have to @wearfinethingsalltoowell you are to angst as Wee John is to setting fires.

Buttons: @beardedblack (its the icon) and @scary-flag

The Swede: @sherlockig

Fang: @skysofrey

................. And I hope I didn't forget anyone...

#tumblr shenanigans#asks#answers#cym#nesbit#ofmd#this was actually like so hard for me rofl#i stalked everyones blog and read their tags for vibes

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

And to follow up yesterday's #repostober with another piece from 2020, this is Nesbit who is another one of my aliens and the same race as Smilin' Jack.

Today is day 11!

1 note

·

View note

Link

Books by Nesbit

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/407

There was a time, not so long ago, when things were perfect for the children up at the bright-faced house, at the edge of London. Heaps of toys in the nursery, an enchanted garden that rolled on for ages, and there were always buns for tea. Mother forever merry, forever there. But then Father died, or was imprisoned for treason, or his business partner absconded to Spain with their money, and the family had to abandon all the best old things and perhaps even the beloved house altogether, being reduced to a dank, crumbling cottage. Mother, too, was soon indisposed—dead or shut up in a room writing stories for pay—which left the children to a crotchety aunt or a kindly old gentleman friend. Mostly it left them to their own devices, unsupervised and largely unschooled, to seek their lost fortune together, with the aid of a time-travelling mole, say, or a sand-fairy who granted wishes. A form of reclamation awaited at story’s end: the return of the family’s comfort and prospects, perhaps even the return of Father.

These are the furnishings of the English writer E. Nesbit’s stories for young readers, and, book after book, she rearranged them with enough invention and emotional intelligence to become one of the most celebrated children’s authors of the Edwardian decade. H. G. Wells wrote to Nesbit, regarding her book “The Phoenix and the Carpet,” “I knock my forehead on the ground at your feet in the vigour of my admiration of your easy artistry.” In his essay “On Three Ways of Writing for Children,” C. S. Lewis wrote that Nesbit provided the older members of her audience with “more realistic reading about children than they could find in most books addressed to adults”; he also plucked his famous wardrobe from Nesbit’s story “The Aunt and Amabel.” J. K. Rowling helped herself to entire rooms of the Nesbit estate, down to her flourish for creature names—the Mouldiwarp, the Psammead, et al. “I identify with E. Nesbit more than any other writer,” Rowling has said.

Nesbit moved easily back and forth between realist and fantasy fiction, and these parallel strains are represented by a pair of her books being reissued this fall: “The Railway Children” (HarperCollins Children’s Classics) and “The House of Arden” (New York Review Children’s Collection). Both books, like much of Nesbit’s work, are episodic and sometimes picaresque, shrugging off the moralizing that was native to young people’s literature of the time, in favor of privileging a child’s logic and point of view. Both show glimmers of the Socialist beliefs that guided much of Nesbit’s adult life. And, most crucially, both books are constructed from a blueprint that is also a kind of reënactment of the author’s own childhood: an idyll torn up at its roots by the exigencies of illness, loss, and grief.

Edith Nesbit was born in 1858 in Kennington, London, where her father ran an agricultural college that his own father had founded. Daisy, as she was known, spent her earliest years romping with her brothers and mingling with students on the school’s three-acre grounds. The family home, she later recalled, “had a big garden and a meadow and a cottage and a laundry, stables and cow-house and pig-styes, elm-trees and vines, tiger lillies and flags in the garden, and chrysanthemums that smelt like earth and hyacinths that smelt like heaven.” When Daisy was three and a half, her father died of tuberculosis, and her mother took over management of the college. Several years later, one of Daisy’s sisters also fell ill, launching the Nesbits on a semi-permanent European itinerancy in search of sea air and mild winters: Brighton, the South of France, and a farmhouse in La Haye, where, Nesbit wrote, “My mother, with a wisdom for which I shall thank her all my days, allowed us to run wild.”

Eleanor Fitzsimons’s wonderful biography “The Life and Loves of E. Nesbit,” from 2019, opens in Bordeaux, where nine-year-old Daisy visits the infamous mummies’ crypt at Saint-Michel. “Round three sides of the room ran a railing, and behind it—standing against the wall, with a ghastly look of life in death—were about two hundred skeletons,” Nesbit wrote thirty years later. “Skeletons draped in mouldering shreds of shrouds and grave-clothes, their lean fingers still clothed with dry skin, seemed to reach out towards me.” The mummies, some of them frozen in the screams and convulsions of death, were “the crowning horror of my childish life,” Nesbit wrote. The spectre of the undead would haunt many of her stories and books to come, a motif that occasionally dovetailed with an even more dominant refrain: that of expired or absent parents.

Nesbit was erratically educated but constitutionally bookish, having read “The Anatomy of Melancholy” by age thirteen. At twenty-one, she married a bank clerk and would-be entrepreneur named Hubert Bland. She was content with bucking Victorian social mores: on the day of her wedding, in 1880, she was seven months pregnant, and, when Bland, a known philanderer, went on to have at least two children out of wedlock, she agreed to raise them as her own. The couple wrote fiction together under the pseudonym Fabian Bland and co-founded the Fabian Society, the genteel Socialist salon that helped galvanize the start of the Labour Party, attracted the likes of H. G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw, and today bills itself as Britain’s oldest political think tank. A sympathetic observer—the wife of a leftist politician—wrote of the Blands’ “charming little Socialist and literary household,” in a London suburb, that the neighbors were “terribly scandalised” by the “merry little Bland children in aesthetic pinafores . . . running about the garden with bare feet!”

As a writer and as a mother, and likely as a child, Nesbit saw kids—siblings, especially—as self-governing, faintly anarchic communities unto themselves. Her first book for children, “The Story of the Treasure Seekers” (1899), established the Nesbit tone: chatty and discursive, but threaded with a stoic wistfulness. It was also the first of her trilogy about the Bastables, whose personalities and circumstances borrowed heavily from the family that Nesbit was born to and the one that she made with Bland. “We are the Bastables,” the narrator of “The Treasure Seekers” announces. “There are six of us besides Father. Our Mother is dead, and if you think we don’t care because I don’t tell you much about her you only show that you do not understand people at all.” This oddly childlike turn—to acknowledge pain in the act of deflecting it, and thinking that to do so is very grown-up indeed—is a signature Nesbit gambit. In “The Railway Children” (1906), the kids are moved by their mother’s transparent attempts, after their father is jailed, to put on a brave face, and they show their gratitude by imitation. “She doesn’t want me to know she’s unhappy,” one says, “and I won’t know; I won’t know.”

Video From The New Yorker

A Veteran’s Return from the Brink of Terrorism

“The Railway Children” is possibly Nesbit’s most cherished book in the United Kingdom, owing in part to the comfy familiarity of a 1970 film adaptation starring Jenny Agutter as Roberta, the mature and capable eldest child. The family’s entire reversal of fortune is pulled off in a single short chapter: Father is arrested after being falsely accused of selling state secrets to the Russians, and, as a result, Mother and the children are forced to “play at being poor,” moving to a rat-bothered cottage where the garden looks “like a dripping-pan full of black cabbages.” The matriarch must clear her husband’s name and, overnight, become the family breadwinner, which she does, quixotically enough, by selling stories; in some ways, she appears to be a sainted version of Nesbit herself. (Both women, for example, enjoyed composing verse for their children “for their birthdays and for other great occasions, such as the christening of the new kittens, or the refurnishing of the doll’s house, or the time when they were getting over the mumps.”)

“The House of Arden” (1908) is, to some extent, a magic-infused remix of “The Railway Children.” The Mouldiwarp, a little white mole with a magic clock, facilitates a journey through British history—the Gunpowder Plot, Anne Boleyn—for the Arden siblings, the dispossessed heirs to a great estate. Fitzsimons, in “Life and Loves,” identifies an elegiac quality to Nesbit’s interest in the restorative potential of time travel: in 1900, Nesbit and Bland’s fifteen-year-old son, Fabian, died after routine surgery to remove his adenoids, and the unending grief that followed added more of an undertow to Nesbit’s work. In “Harding’s Luck,” the sequel to “The House of Arden,” she writes, “There are certain children born now and then—it does not often happen, but now and then it does—children who are not bound by time as other people are.”

Some of Nesbit’s best stories possess the peculiar, faraway-so-close melancholy of being able to conjure the ghost of a loved one without being able to touch or speak to them, for fear of dissolving the apparition. In “The House of Arden,” the children infiltrate the kingdom where their father is being held in luxurious captivity by transforming into cats; unable to reveal their identities to him, they only purringly rub against his legs. “Arden,” like “The Railway Children,” takes shape as a desperate mission to save the missing Daddy. The books have extremely similar endings, with identical children’s cries—joyous and anguished at once. In “The Railway Children,” the authorial voice finds the final scene of reconciliation to be so raw and private that she must turn away. “I think that just now we are not wanted there,” the voice says. “I think it will be best for us to go quickly and quietly away.”

As Nesbit’s wealth and literary celebrity grew, so did the Blands’ renown as hosts. In 1900, not long before the shocking death of Fabian, they moved into a mansion in Greenwich, replete with moat, swans, wild gardens, and a grand hall for hosting Fabian Society debates and political speeches. In envisioning a Socialist future for England, their praxis was extreme hospitality. The Bland pile was more or less an open house, with the tall and elegant Nesbit presiding over the festivities in her loose-fitting Liberty prints, waving her ever-present cigarette holder. H. G. Wells called the house “a place to which one rushed down from town at the week-end to snatch one’s bed before anyone else got it.” (Nesbit and Wells later sparred over the question of sentimentality in fiction; they fell out entirely after an alleged indiscretion between Wells and her stepdaughter.)

Nesbit’s Socialist loyalties only occasionally risked tipping her books into becoming Socialist tracts. (Richard, the proud-hearted cousin in “The House of Arden,” delivers a speech straight from the floor of the Fabian Society: “They make people work fourteen hours a day for nine shillings a week, so that they never have enough to eat or wear, and no time to sleep or to be happy in.”) Yet, despite her progressive bona fides, Nesbit was more of an old Victorian than she might have liked to admit. Her books are, at moments, blighted by racist and colonialist language and anti-Semitic tropes. And, although it was Nesbit’s career, her talents and determination, that had earned the Blands their home and social prominence, she shared with Margaret Thatcher a for-thee-and-not-for-me gender essentialism. She opposed the cause of women’s suffrage—mainly, she claimed, because women could swing Tory, thus harming the Socialist cause. When she participated in a lecture series of the Fabian Women’s Group, she maintained that women were mainly fit to be wives and mothers, and that, according to Fitzsimons, “the cultivation of the intellectual or masculine characteristics of women would end in sterility and race extermination.”

Such internalized misogyny is less evident in her fiction, even if Nesbit tends to seem more compelled and amused by her boys than her girls. “The House of Arden” contains an enchanting exchange with an enigmatic old woman on how female intelligence can unjustly backfire (“From ‘wise woman’ to witch was a very short step indeed”). In “The Railway Children,” Father, just before he is arrested, is made to say, “Girls are just as clever as boys, and don’t you forget it!” Nesbit is not pro-girl so much as simply pro-child: in favor of valuing their opinions, honoring the realities of their inner lives, and giving them the freedom to explore and build worlds of their own, together or alone. In “The House of Arden,” her spin on the didacticism rampant in Victorian children’s literature, is a brief, Wordsworthian ode to the meditative state: “Now, if you sit perfectly silent for a long time and look at the sea, or the sky, or the running water of a river, something happens to you . . . a kind of gentle but very strong inside magic, that makes things clear, and shows you what things are important, and what are not.”

In “On Three Ways of Writing for Children,” in which he sings Nesbit’s praises, C. S. Lewis contends that the writer in her own book is not the same as the writer in real life; and that a similar, subtle alchemy—the inside magic—occurs in her reader. “The printed story grows out of a story told to a particular child with the living voice and perhaps ex tempore,” Lewis wrote. He went on, “You would become slightly different because you were talking to a child and the child would become slightly different because it was being talked to by an adult. A community, a composite personality, is created and out of that the story grows.” This vision of reading as something at once private and communal—as something generative—is rather utopian. Nesbit’s utopias, in turn, are rather Socialist, exemplified in the Eden-like London of tomorrow laid out in “The Story of the Amulet.” More to the point, they are a children’s polis. But her children remain children; to read Nesbit’s stories today is to summon a nostalgia for a future that never arrived. “Let’s go into the future again,” one of her young characters proposes. “Perhaps we could remember if it wasn’t such an awful way off.” ♦

#article#books#books and literature#books and writing#books and libraries#books and authors#books and reading#socialism#fabian society#nesbit#gutenberg#ebooks#women authors#women writers#free books#free ebooks

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria mi negra culona Casero de Perrito Chiclayo

Soccer mom fucks the coach after practice

Amateur CD

bareback sex gay anal

Amateur gay anal at kicthen older and teen

Getting fucked , squirting our loads

Morrita rica se deja follar

Travesti argentina giara mishell

Guy blows huge load on brunette MILF Vickie Powell big tits after hot sex

PINAY REAL LIFE SEX STORIES PART 16

#esophagectasia#slopes#re-representation#stimulation#upwards#soften#calavera#Natricinae#Doomsday#pendulum#flowstone#Debrecen#multicar#thin-set#unadjustably#hyetal#Nesbit#pret#smokeshop#intersituate

1 note

·

View note

Text

Looking for more propaganda for the following hot ladies—particularly text propaganda, especially if it conveys a hot lady’s on-screen vibe or general personality!

Bebe Daniels

Barbara Bedford

Devika Rani

Vilma Banky

Evelyn Nesbit (someone sent me some but I think I’ve lost it)

Stefania Sandrelli

Marie Doro

Lilian Bond

Jane Birkin

Zulma Faiad

Anouk Aimée

Suchitra Sen

Hend Rostom

Alma Rosa Aguirre

Purnima

Again, mostly looking for text—I'll accept some pictures if you'd like to send them too but they're not my priority rn. Send it to my inbox. Thanks!

#housekeeping#bebe daniels#barbara bedford#devika rani#vilma banky#evelyn nesbit#stefania sandrelli#marie doro#lilian bond#jane birkin#zulma faiad#anouk aimée#suchitra sen#hend rostom#alma rosa aguirre#purnima#ladies 2

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

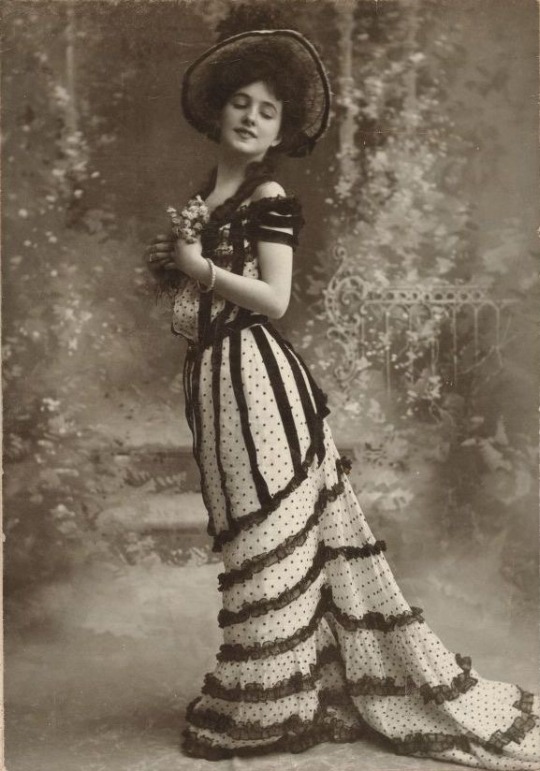

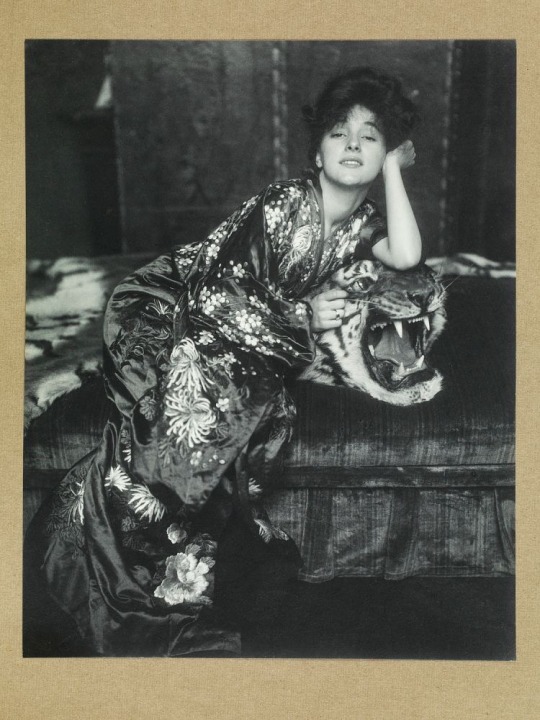

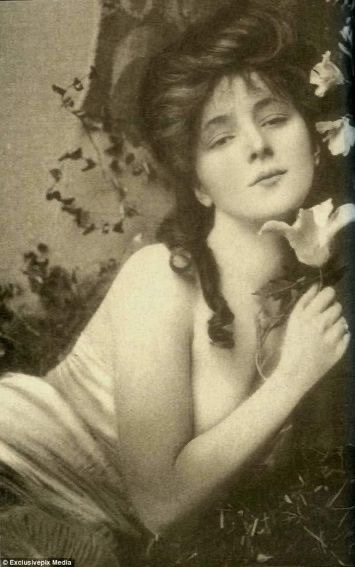

Birthday remembrance - Evelyn Nesbit #botd

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

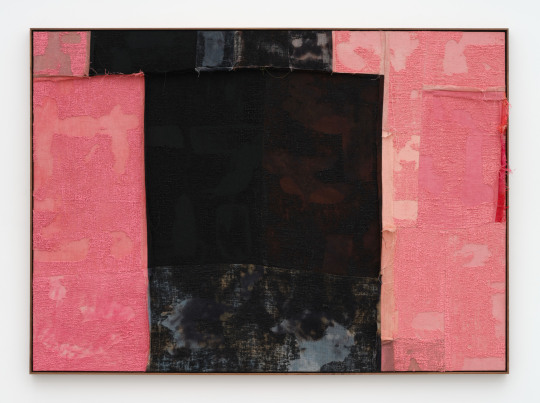

Evan Nesbit

Symplegades

2023

Acrylic, dye, and burlap

110 x 79 in. (279.4 x 200.7 cm)

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evelyn Nesbit (December 25, 1884 1885 – January 17, 1967).

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

The face of the Gibson girl, the classic gilded age beauty—Evelyn Nesbit

Evelyn Nesbit was an American artists' model, chorus girl, and actress. She is best known for her career in New York City, particularly her involvement in an abusive and ultimately deadly love triangle between railroad scion Harry Kendall Thaw and architect Stanford White, which resulted in White's murder by Thaw in 1906.

Stanford White was the architect who designed the Madison square garden. He befriended Evelyn and her mother when she was a young poor art model trying to help support her family by posing for photographers and painters alike. Stanford groomed Evelyn, and one night he brought her back to his house, plied her with champagne, and then proceeded to drug and rape her. He continued to abuse her for a period of time after this. He told her to keep it a secret.

She dated John Barrymore, and they were each others first loves. The relationship was short lived, but neither ever forgot the other.

Evelyn married Harry Kendall Thaw, and eventually she confided the assault to her new husband. Though Evelyn felt relieved to finally speak it aloud to another human being, Harry obsessed over exacting revenge on White.

At 11 pm Thaw fired three shots into Stanford White’s head, killing him instantly. White was ironically attending the rooftop theater at Madison square garden.

354 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evelyn Nesbit

#evelyn nesbit#antique photography#antique#vintage#1900s#edwardian era#edwardian#gilded age#the gilded age

157 notes

·

View notes

Note

did u know u can put rainbow sprinkles on anything? they sell them at the store and you can just buy a whole shaker of rainbow sprinkles. it’s just sugar. you can put it on anything. put it in your tea instead of syrup. you can put it on your waffles instead of honey. you can put it straight on strawberries and eat them. rainbow sprinkles on everything at home. improves quality of life greatly, highly recommend 💛

Rainbow sprinkles are life. Everything is better with rainbows on it.

So imagine those sprinkles just like... being poured onto my face or something.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

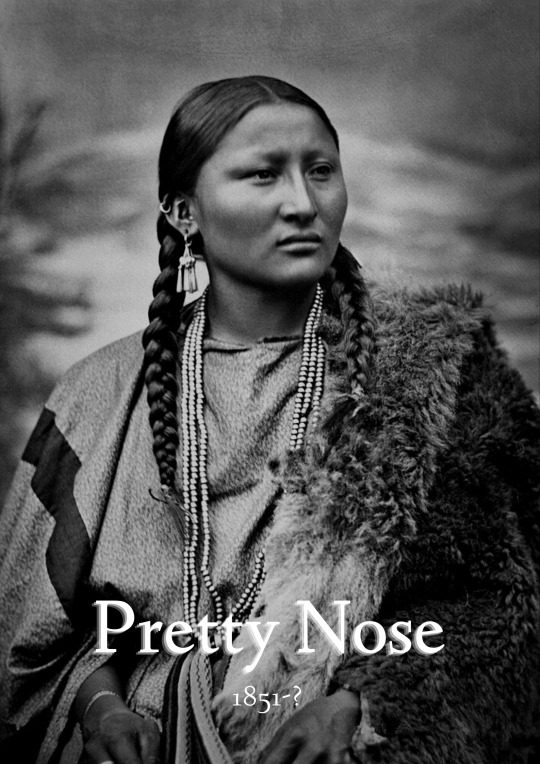

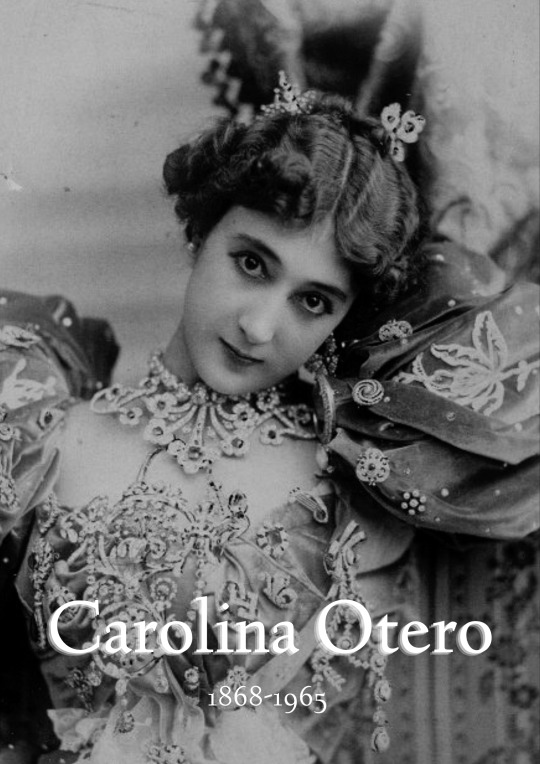

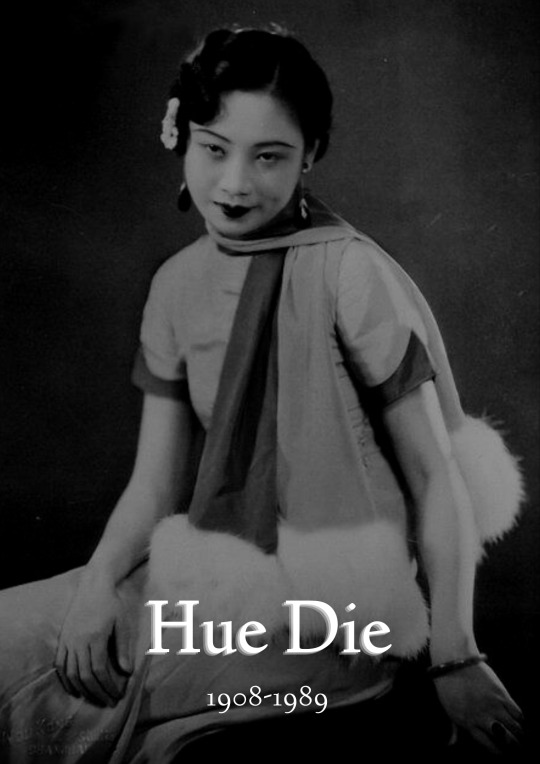

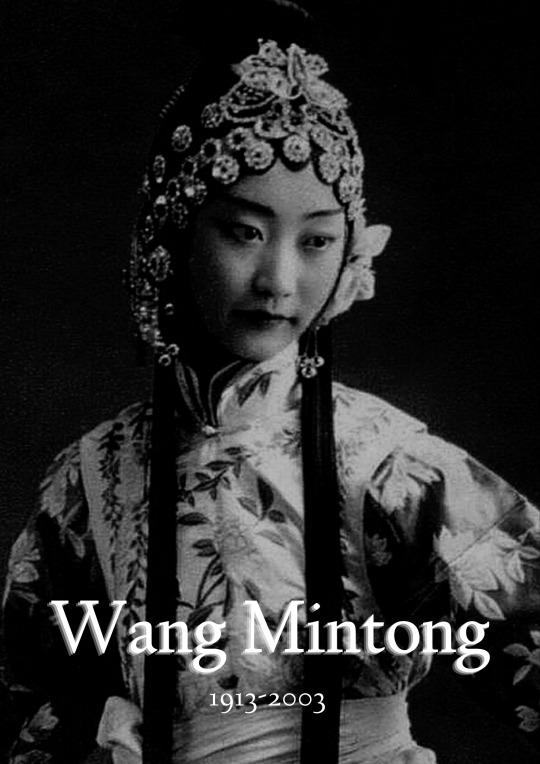

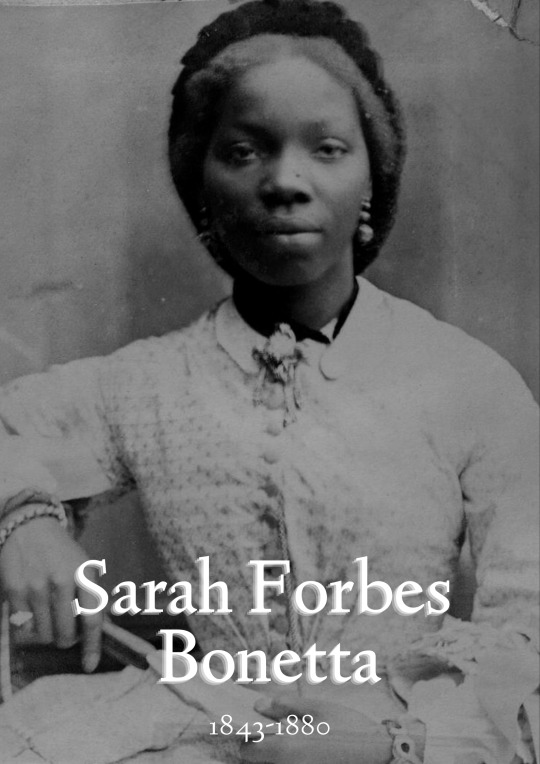

beautiful women of the past (imo) iiii

#my sister begged me to do another so here it is#women in history#history#cleo de merode#pretty nose#carolina otero#evelyn nesbit#pauline starke#hue die#wang mintong#lillian russell#sarah forbes bonetta#anita louise#*#ph#photography#vintage

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Evelyn Nesbit

28 notes

·

View notes