#Shetland folklore

Text

The elusive wulver...

In folklore werewolves aren't anywhere near as monstrous as they are often portrayed in modern fantasy. There are plenty of horror stories about them, but often they just cause misschief, of startle people, and they can even be (begrudgingly) helpful, or end up the victim of their story. You can find various examples scattered about on my blog.

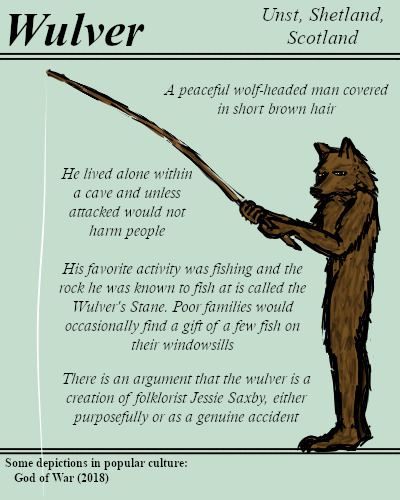

But among all stories of wolf-people, the wulver from Shetland stands out as a particularly kind character. The wulver is described as bipedal, furry, but with a wolf's head, which is not unheard of for more human acting werewolves in folklore. (Although you could argue this isn't a werewolf at all, because it never was, nor will be, fully human.) Its other main characteristic is being a keen fisherman, and sharing its catch with hungry locals.

This description comes from folklorist Jessie Saxby's 1932 book Shetland Traditional Lore, and seems the wulver's only source. Briggs quotes it in my beloved Encyclopedia of Fairies (1976), but has no other information to offer. Now of course it isn't unheard of to have only one written source for very local folklore. But they are usually a little older than the 1930s and it is odd if there is no other folklore or stories surrounding it that are even a little bit similar.

So the wulver, as a folkloric creature, kind of bugged me, and I'd look into it every now and again. But! Since I did so last, an archivist at the Shetland Museum named Brian Smith has written an article on the subject! A slightly frustrated article concluding:

The wulver has its origins in Jakob Jakobsen’s place name research, and Jessie Saxby’s misrepresentation of it. There is no Shetland wulver tradition older than 1930.

His explanation that "wulver" or "wolver" was a Shetland pronounciation of the old Norse álf (fairy) used in place names like "Wolvershul" (fairy hill), sounds solid to me. And the claim that Jessie Saxby is the only one who uses it as a name for a wolf creature also seems reasonable. But it is very clear that Smith has a bone to pick with her: "Hardly a month passes without someone asking the Shetland Archives for information about the creature."

I do feel for him, but I'd like to believe that Saxby didn't invent the wulver out of nothing on purpose. Perhaps she and one of her informants got a little lost in a headcanon, perhaps she accidentally mixed in some cynocephaly folklore. Either way, the wulver is a compelling character, and a pretty term for a wolf-creature. Folkloric or not, it makes as good an addition to the modern fantasy population as perytons and dullahan.

But I do love having a plausible answer to my doubts. Read the article yourself if you're interested:

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

And last of the Celtic ones: the Wulver, from the Shetland Islands of Scotland. Unlike a lot of the wolfman myths, Wulver is apparently benign, solitary and just wants to be left alone to fish - occasionally sharing his catch with local widows #HellaWieners

#halloween#hellawieners#hella wieners#halloween 2023#celtic mythology#celtic folklore#scottish mythology#scottish#shetland islands#Shetland folklore#Wulver#werewolf#wolfman#scottish folklore

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

A surprisingly friendly canid fellow the Wulver, artificial creation or not, was a being of peaceful solitude. He would not strike unless struck, and often shared some of his catches with those who needed it.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#myth#mythology#wolfman#wulver#scottish folklore#scottish legend#wulver's stane#jessie saxby#shetland folklore

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#trows#of#orkney islands#shetland islands#trow#fiddle#melancholy#baroque#tartini#violin#sonatan#classical music#fantasy#folklore#transit#zone#shift#emerge#transcend#midwinter#saga#the sea#time#Youtube#tam bichan

1 note

·

View note

Text

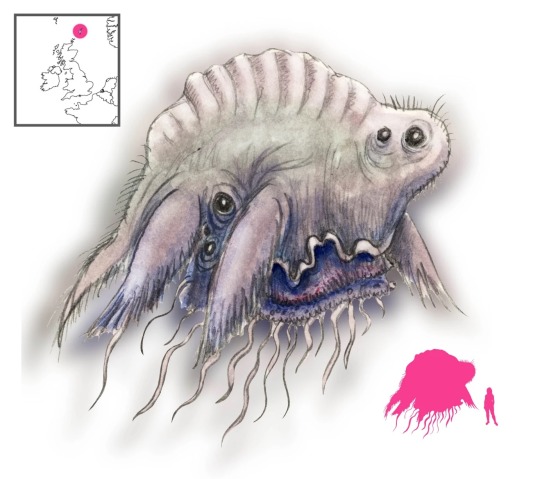

one of my favorite underrated mythical creatures is It (I’ve also seen it called the boneless or the frittening), which is from the shetland islands and is literally just this horrible mass that comes up out of the sea and terrorizes people and nobody knows what it is because it looks different to everyone. the nuckelavee is the breakout star of northern isles folklore sure, but give some credit to It!

(art credits to the late shigeru mizuki and @a-book-of-creatures)

0 notes

Text

The Tangi [Scottish, Shetland folklore]

There are lots of folktales about supernatural horses that live underwater and entice people into mounting them. Once the victim does so, they find themselves unable to dismount and the horse takes its prey underwater to drown them. The most famous of these creatures are the Scottish Kelpie and the Welsh Ceffyl Dŵr, though there are lots of similar aquatic horse monsters from British, Germanic and Scandinavian folktales. They are related and come from the same root story.

In the Shetland Islands, however, there are two such creatures, and while they are undeniably similar, surprisingly they are said to be two distinct kinds of beings that exist in different habitats. The Njuggel (or ‘Shoopiltee’ in Northern Shetland, among other names) resides in lakes and other fresh bodies of water, whereas the Tangi (also Tangie) is a marine monster. Keep in mind however that this distinction is not set in stone (folklore is hardly an exact science, of course) and in some places the Njuggel and the Tangi are considered to be synonyms.

In the Orkney islands of northern Scotland, the Tangie would appear either as an old human covered in seaweed (true to its name, as the name ‘Tangie’ is likely derived from ‘tang’ which is a local term for seaweed) or as an aquatic horse. This Tangie would jump out at unwary travelers, and it took a particular liking to young women, kidnapping them from the banks of the Scottish lakes and dragging them into the depths to be devoured.

In places where the two are said to be separate monsters, the following distinction is usually made: a Njuggel appears as a white or grey horse with a wheel for a tail that drowns its victims in lakes. A Tangi, on the other hand, is black or dark grey and has no wheel. Tangis are shapeshifting creatures and sometimes appear as cows, other animals, or as humans. When taking the form of a human, a Tangi usually chooses to appear as a handsome young man and seeks out girls to seduce and have sex with. Sometimes they go the extra mile and abduct a girl to marry her. Being associated with the sea, they commonly haunt shores but these creatures make their homes in seaside caverns.

Like its cousin the Njuggel, a Tangi is engulfed in a blue flame when galloping at high speed. Sailors sometimes claimed to have seen one of these creatures as a distant blue flash that raced across the shore.

One old account of these creatures also claimed that they have wings and the uncanny ability to locate any object that fell or was thrown into the ocean, regardless of depth. These claims are not backed by any other sources. However, they do have an important trait that sets them apart from Kelpies, Njuggels, Nixen and the like.

Whereas most Kelpie-like monsters are said to make people mount them and then drown their victims, the Tangi does not need to be mounted. It can cast a spell on its victims by galloping in circles around them. When under the influence of the Tangi’s magic, the victim becomes hypnotized and immediately tries to drown themselves, usually by jumping off a cliff into the ocean. Those who survive find themselves in a dazed state which lasts for a few days at most.

They are not invincible however and share the same weaknesses as the Njuggels: they are afraid of fire, can be injured with iron and lose their power if you utter their name. For example, one story tells of a man who encountered a Tangi. The black horse started running in circles around him but he managed to stab it with an iron knife. The creature ran away and disappeared.

Sources:

Teit, J. A., 1918, Water-beings in Shetlandic Folk-Lore, as Remembered by Shetlanders in British Columbia, The Journal of American Folklore, 31(120), p.180-201.

Lecouteux, C., 2016, Encyclopedia of Norse and Germanic Folklore, Mythology, and Magic.

Monaghan, P., 2004, The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore, Facts on File Library of Religion and Mythology, 512 pp.

Pérez-Lloréns et al., 2020, Seaweeds in mythology, folklore, poetry and life, Journal of Applied Phycology, 32, 3157-3182.

(image source 1: orig03 on Deviantart. The image actually depicts a black Kelpie, but I figured it’s fine since the Tangi is related and similar)

(image source 2: unknown, sorry)

#Scottish mythology#British mythology#aquatic creatures#monsters#Kelpie#mythical creatures#fey#bestiary

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scottish Folklore Songs (Historic Recordings)

The site Tobar An Dualchais is a collection of historic audio recordings in Scotland, and that includes songs. I collected just some of the folklore related ones into a list for you all.

I have no talent in singing, so I will have to leave that up to the rest of you. Some are in English, and other are in Gaelic.

Kelpies and Each-Uisge 🐎🌊

(link) A MHÒR, A MHÒR, TILL RID MHACAN.

"This song, which was used as a cradle song, was said to have been a lament composed by a water-horse(each-uisge) whose mortal lover had gone, taking their child with her. He is pleading with her to return. "

(Recorded in 1956)

(link) A GHAOIL LEIG DHACHAIGH GU MO MHÀTHAIR MI

"This song takes the form of a conversation between a girl and a water-horse. The girl is asking him to let her return home to her mother. The water-horse has other ideas. It is clear from the last verse that the girl escaped. "

(Recorded in 1954)

(link) 'ILLE BHIG, 'ILLE BHIG SHUNNDAICH Ò

"This is a fairy song. It was said to have been composed by a girl who was in love with a water-horse. As the song describes, he was killed by her brothers. The song lists some of the gifts he had promised to give the girl. "

(Recorded in 1963)

Mermaids 🧜♀️

(link) ÒRAN NA MAIGHDINN-MHARA

"In this song a mermaid says that she was deceived. She fell in love with a man even though he was human and she was a mermaid. Her sleep is unsettled when there is bad weather. "

(Recorded in 1963)

Selkies:

(link) THE GREAT SELKIE OF SULE SKERRY

"Supernatural ballad in which a woman bears a son to a selkie."

(Recorded in 1973)

(link) THE SELKIE

"The woman is speculating on who her baby's father is, when he appears and tells her he is Gunhaemilar and he is a selkie [seal man]. She is distraught and turns down his proposal of marriage. He tells her to nurse the baby for seven years, then he will return and pay her. He comes back and she asks him to marry her, but he rejects her in the same words she used to turn him down. He says he will put a gold chain round his son's neck so she will know him. She marries a gunner who shoots both the selkie and his son and she dies of a broken heart. "

(Recorded in 1971)

(link) UNKNOWN

"A Shetland song mentioning the selkies."

(Recorded in 1985)

Other:

(link) MORAG'S FAIRY GLEN

"Song of a man telling the beauty of Morag's Fairy Glen, and bidding his love to meet him there. "

(Recorded in 1952)

(link) FAIRY DANCE

"This is the reel 'Fairy Dance' played on the fiddle. "

(Recorded in 1970)

(link) CRODH CHAILEIN

"This song belongs to the fairy songs tradition and was used as a milking song or lullaby. Colin's cattle referred to in the song are the deer. "

(Recorded in 1955)

(link) TÀLADH NA MNATHA SÌDHE

"This song is a fairy cradle song in which the speaker says she would wander in the night with her beloved child. Sections of the song contain vocables which belong to the piping tradition."

(Recorded in 1970)

(link) HORO 'ILLE DHUINN SHUNNDAICH

"A song in which a woman tells of the murder of her fairy lover who promised her the kertch of a married woman."

(Recorded in 1994)

(link) HÈ O HÒ A RAGHNAILL UD THALL

"In this fairy song, a fairy woman is trying to get a herdsman called Ronald to come across a river to her. Fairies cannot cross water." (In some stories, certain types of fairies can't cross running water)

(Recorded in 1953)

(link) HÓRO 'ILLE DHUINN SHUNNDAICH

"Song about a woman with a fairy lover."

(Recorded in 1962)

(link) ÒRAN AN LEANNAIN-SÌTH

"In this song the bard tells of being visited by a fairy lover. She asks him to make her a song, which will win an award at the Mod. He describes her beautiful appearance and sweet voice. She promises to give him a magic wand. She tells him about some of her deeds, and reminds him to make the song as she requested."

(Recorded in 1960)

#fairies#fairy#fae#songs#music#historical#folklore#scottishfolklore#scottish folklore#FairyBasics#selkie#selkies#mermaid#mermaids#mythology#kelpies#kelpie#eachuisge#waterhorse#waterhorses#faeries#fairyart

164 notes

·

View notes

Note

Question but what books do you read when doing research on finfolk? Are they physical or digital ones? I’d like to research them as well.

I look at both physical and digital books. I found out about Finfolk after I was flipping through Orkney stories (it mainly had Selkies, witches, and ghosts, but finfolk caught my eyes).

The two physical books I have are:

Orkney Folk Tales by Tom Muir

The Mermaid Bride, also by Tom Muir

I noticed that Tom Muir has a big role in almost all the folk lore books for Orkney, I feel like I should do research on him sometime.

Here are some links on where I get my information:

https://owlcation.com/social-sciences/The-Finfolk-of-Orkney-Folklore

Youtubers that actually go over it (surprisingly it's been trending since 2021 to just recently?):

youtube

youtube

Hope this helps! It seems that in recent years finfolk have been becoming more well-known so I'm sure more stories will come out eventually.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

ANNOUNCEMENT:

Shetland Fic Fest 2023

Let’s fill AO3 with new Shetland fics in 2023! Below are the suggested posting dates and prompts, but feel free to do something else entirely. Art and videos also encouraged!

Schedule:

Wednesday 1 March - Rarepairs

Thursday 2 March - AU

Friday 3 March - Series 7 Fix-it

Saturday 4 March - Folklore, folk horror, history and ritual

Sunday 5 March - Casefic

Monday 6 March - Crossovers

Tuesday 7 March - Comedy

Tagging:

Share your fics with the tag #shetlandficfest23 and we’ll reblog.

#bbc shetland#shetland bbc#shetlandficfest23#jimmy perez#duncan hunter#cassie perez#Alison “Tosh” McIntosh#Sandy Wilson#Rhona Kelly#Billy McCabe#Cora McLean#Donna Killick#douglas henshall#mark bonnar#julie graham#Ruth Calder#Ashley Jensen#Jimmy/duncan#jimmyxduncan#jimmy perez / duncan hunter#shetland#Steven Robertson#shetlandficfest

73 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! About the Scottish mythology map, I'm from Shetland and the wulver isn't actually part of our folklore/traditions. It was invented by one person in the 1930s, then spread on the internet and now haunts the Shetland museum staff who keep being asked questions about it! https://www.shetlandmuseumandarchives.org.uk/blog/the-real-story-behind-the-shetland-wulver

Aye that’s fair, although a whole bunch of folklore stems from that period anyway. If it’s bothering people then that’s fair enough.

73 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, was just wondering if you knew anything about the waterhorses on the Shetland Isles and Orkney. As far as I can tell there is alot contradictions and overlapping between the two places and I don't know how much is down to translation errors. Like nuggle, shoopilte and tangie all being named as separate creatures and also being classed as different names for the same spirit.

You're definitely correct that there is a lot of of overlap between the three. Even in older folklore books, they often get lumped together or treated as regional names for the same being. I do believe there are enough differences to classify them as separate creatures, but again there's a ton of overlap and contradiction opinions.

I'll start with the tangie, as it has the most written lore that I've been able to find. Generally they're considered to be sea creatures, vs some other waterhorses that are found inland in rivers and lochs. They're also the only waterhorse known for taking on a merman form. Older stories describe them as being apple green, while later they're almost always described as being black with a rough coat. The most famous tangie was ridden by the sheep rustler Black Eric, so if you're looking for stories that's your best starting point.

Shoopiltee and nuggle are both far less known, and there's a lot less information on them. The shoopiltee is slightly more popular, from what I've found, but the two are almost always referred to as the same beings under different names. I have found a few differences though. Shoopiltee usually take the form of shetland ponies, much smaller than most waterhorses. While they are known for drowning people, there are also a few scattered tales of them being more mischievous than malevolent, or even friendly. There are also accounts of people sacrificing coins or alcohol to the shoopiltee in exchange for successful fishing.

The nuggle is the one I've found the least amount of written information about. Unlike the shoopiltee, they tend to appear as a full-sized horse, sometimes described as having hair that faces the wrong direction (forward toward the head). Most accounts have the nuggle inhabiting inland pools or lochs, again unlike the tangie and shoopiltee who seem to favor the sea.

#asks#waterhorse work#i know this isn't much but i hope it's helpful!#there's just genuinely not that much info on any of these guys which is a damn shame

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

How much do you know about seal and selkie mythology? Do you have any Strong Opinions on parts of it, or a favorite?

I know a fair amount and my main opinion is it's unfair the only one people ever know is The Seal Wife. Like, did you know in some places selkies have very powerful weather magic and are greatly feared because if they're disrespected (aka if you kill a seal needlessly) they'll call up storms? There's a legend I think from the Shetlands where once upon a time on a remote island someone killed a seal pup and every time the islanders sent their boats out the selkies would call up a storm to sink them, and they weren't satisfied until all the men on the island committed mass suicide by jumping off a cliff. Selkies take debt and obligation very seriously, like in The Seal That Did Not Forget where an islander is about to take a seal's two pups to make a coat when he hears the seal make a human sobbing sound and sees her crying tears (seals do actually look like they're crying sometimes), so he takes pity on her and brings them back to her, and then years and years later his children are out on the sand bar gathering welks and don't notice the tide coming in, but just when they think they''re trapped and will be drowned a huge seal comes out of the water and carries them safely to shore. Everybody knows there are families in Scotland and Ireland that have a female selkie ancestor (The Seal Wife again) but did you know that it was also common for fishing families to have usually a young uncle or cousin who everybody knew hadn't really drowned at sea, but had gone under the water to live with the selkies? The idea that seals and humans aren't just related but can change places is actually pretty common. It's not just the folklore about Pharoah's army not drowning in the Red Sea but turning into seals, but also there are Alaskan Native legends about a boy who gets sent under the ice to live with a family of bearded seals so he can become a great hunter (and obviously seals have a whole society under the ice that mirrors human society above it), or about a young woman who everyone thought had died coming back into the village but actually she was a seal who had transformed into a human. Plus of course seals are the children of Sedna, goddess of all the marine mammals, who is greatly feared because if you displease her by not upholding traditions or by wasting the body of a seal you have killed she'll call all her children under the ice to her and humans will starve. There are a few versions of Sedna's story, the one I know best is the one where her father threw her out of the kayak to try to appease an angry spirit, and when she clung onto the side he hit her fingers until they fell off, but every time they hit the water they became a different kind of seal. Eventually she couldn't hold on any longer and sank down to the bottom of the ocean, where she lives, tended by her seal children, and because she can't hold a comb without her fingers they comb her hair for her. What's interesting is that around Lake Baikal people say that there's a Master who lives at the bottom of the lake and is in charge of all the seals, and when you kill a seal, because it wasn't raised by you but given to you you have to share its meat with other people, or the Master will be angry. So that's actually considered evidence for there having been some kind of either migration or cultural exchange between Alaska and Siberia way way wayyyy back because they're so similar.

Also in Celtic mythology selkie men are really really sexy, they're just so sexy no human woman could ever be expected to resist them.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Merrow

Merrow (from Irish murúch, Middle Irish murdúchann or murdúchu) is a mermaid or merman in Irish folklore. The term is of Hiberno-English origin.

The merrows supposedly require a magical cap (Irish: cochaillín draíochta; Hiberno-English: cohuleen druith) in order to travel between deep water and dry land.

The merrow-maiden is like the commonly stereotypical mermaid: half-human, a gorgeous woman from waist up, and fish-like waist down, her lower extremity "covered with greenish-tinted scales" (according to O'Hanlon). She has green hair which she fondly grooms with her comb. She exhibits slight webbing between her fingers, a white and delicate film resembling "the skin between egg and shell".

Said to be of "modest, affectionate, gentle, and [benevolent] disposition," the merrow is believed "capable of attachment to human beings," with reports of inter-marriage. One such mixed marriage took place in Bantry, producing descendants marked by "scaly skin" and "membrane between fingers and toes". But after some "years in succession" they will almost inevitably return to the sea, their "natural instincts" irresistibly overcoming any love-bond they may have formed with their terrestrial family. And to prevent her acting on impulse, her cohuleen druith (or "little magic cap") must be kept "well concealed from his sea-wife".

O'Hanlon mentioned that a merrow may leave her outer skin behind in order to transform into other beings "more magical and beauteous", But in Croker's book, this characteristic isn't ascribed to the merrow but to the merwife of Shetlandic and Faroese lore, said to shed their seal-skins to shapeshift between human form and a seal's guise (i.e., the selkie and its counterpart, the kópakona). Another researcher noted that the Irish merrow's device was her cap "covering her entire body", as opposed to the Scottish Maid-of-the-Wave who had her salmon-skin.

Yeats claimed that merrows come ashore transformed into "little hornless cows". One stymied investigator conjectured this claim to be an extrapolation on Kennedy's statement that sea-cows are attracted to pasture on the meadowland wherever the merrow resided.

Merrow-maidens have also been known to lure young men beneath the waves, where afterwards the men live in an enchanted state. While female merrows were considered to be very beautiful, the mermen were thought to be very ugly. This fact potentially accounted for the merrow's desire to seek out men on the land.

Merrow music is known to be heard coming from the farthest depths of the ocean, yet the sound travels floatingly across the surface. Merrows dance to the music, whether ashore on the strand or upon the wave.

While most stories about merrow are about female creatures, a tale about an Irish merman does exist in the form of "The Soul Cages", published in Croker's anthology. In it, a merman captured the souls of drowned sailors and locked them in cages (lobster pot-like objects) under the sea. This tale turned out to be an invented piece of fiction (an adaptation of a German folktale), although Thomas Keightley who acknowledged the fabrication claimed that by sheer coincidence, similar folktales were indeed to be found circulated in areas of Cork and Wicklow.

The male merrow in the story, called Coomara (meaning "sea-hound" ), has green hair and teeth, pig-like eyes, a red nose, grows a tail between his scaly legs, and has stubby fin-like arms. Commentators, starting with Croker and echoed by O'Hanlon and Yeats after him, stated categorically that this description fitted male merrows in general, and ugliness ran generally across the entire male populace of its kind, the red nose possibly attributable to their love of brandy.

The merrow which signifies "sea maiden" is an awkward term when applied to the male, but has been in use for a lack of a term in Irish slang for merman. One scholar has insisted the term macamore might be used as the Irish designation for merman, since it means literally "son of the sea", on authority of Patrick Kennedy, though the latter merely glosses macamore as designating local inhabitants of the Wexford coast. Gaelic (Irish) words for mermen are murúch fir "mermaid-man" or fear mara "man of the sea".

Merrows wear a special hat called a cohuleen druith, which enables them to dive beneath the waves. If they lose this cap, it is said that they will lose their power to return beneath the water.

The normalized spelling in Irish is cochaillín draíochta, literally "little magic hood" (cochall "cowl, hood, hooded cloak" + -ín diminutive suffix + gen. of draíocht). This rendering is echoed by Kennedy who glosses this object as "nice little magic cap".

Arriving at a different reconstruction, Croker believed that it denoted a hat in the a particular shape of a matador's "montera", or in less exotic terms, "a strange looking thing like a cocked hat," to quote from the tale "The Lady of Gollerus". A submersible "cocked hat" also figures in the invented merrow-man tale "The Soul Cages".

The notion that the cohuleen druith is a hat "covered with feathers", stated by O'Hanlon and Yeats arises from taking Croker too literally. Croker did point out that the merrow's hat shared something in common with "feather dresses of the ladies" in two Arabian Nights tales. However, he did not mean the merrow's hat had feathers on them. As other commentators have point out, what Croker meant was that both contained the motif of a supernatural woman who is bereft of the article of clothing and is prevented from escaping her captor. This is commonly recognized as the "feather garment" motif in swan maiden-type tales. The cohuleen druith was also considered to be of red color by Yeats, although this is not indicated by his predecessors such as Croker.

An analogue to the "mermaid's cap" is found in an Irish tale of a supernatural wife who emerged from the freshwater Lough Owel in Westmeath, Ireland. She was found to be wearing a salmon-skin cap that glittered in the moonlight. A local farmer captured her and took her to be his bride, bearing him children, but she disappeared after discovering her cap while rummaging in the household. Although this "fairy mistress" is not from the sea, one Celticist identifies her as a muir-óigh (sea-maiden) nevertheless.

The Scottish counterpart to the merrow's cap was a "removable" skin, "like the skin of a salmon, but brighter and more beautiful, and very large", worn by the Maid-of-the-wave.

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

Directors’ commentary on the lore used in Sea Salt?

Oh my god there is so much

The concept of Beithir is based on three different pieces of folklore, Beithir himself is Scottish, the stoor worm is Orkney and the breathing in and out over six hours forming the tide is from Shetland. There's a big thing in mythos of chopping up snakes that will rejoin if you're not careful so that still happened they just kinda ended up in the sea here.

To seafarers the moon is believed to be his eye lost during this period and nathair believe their ancestors sprang from his blood thus seeing him as their patron. He's down at the very bottom in an ouroboros fashion, his head will show up wherever someone is speaking to him and should he need to reply he'll bite the tail in his mouth to do so. Part of a murúch's creation from a recently deceased involves a prayer to him so no matter who raised them if he calls them they'll obey.

The name murúch is Irish coming from their mermaid myth called merrow and while these guys don't have a little cap that lets them go into the sea/onto land they do stitch their legs together to form a tail and vice versa. Just like them they're always one or the other though will be drawn to the sea.

Ceasg meanwhile is a Scottish mermaid! While this generally refers to a singular lady here it's adapted to an entire species who are mammalian instead of salmon tailed though the half tails still reflect their origins. The finfolk they're often mistakeningly called within fic are actually Orkney who are believed to be what selkies sprang from at some point down the line which merrow have similar. For fun irony finfolk supposedly do wander between land and sea so in universe humans just kinda applied it to two different seafarers thinking they were the same thing. Marc references Finfolkaheem, the supposed home of finfolk, and ceasg as a whole share the same ! about silver.

The Sea Mither is an Orkney legend who subdued the terrible nuckelavee to the depths and lives in the sea herself during the spring/summer. Teran pops up in autumn wearing her down in a fight until she flees to land and takes over until she comes back renewed in spring. Seafarers revere her though not many on land seem to do the same though there are pockets of exceptions such as Félix who sometimes mentions her by name.

Cailleach who pops up in multiple places around the isles and is not in fact her sister and was smooshed for fic reasons. She's generally associated with making the landscape, wilderness, weather and winter which is the same here. During that time of year might occasionally hear someone mention the Mither fled to her side to ride out that shit while recovering from more folklore conscious seafarers.

Unlike Beithir there's certainly no proof either lady or Teran are really out there but most decide it better not to piss them off, just to be safe.

Really all it boils down to we have cool shit on these islands and an alarming amount of bastard horses that should be used more.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listening to podcasts about Shetland folklore for this one shot fic

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Njuggel [Shetland/Scottish folktales]

The Scottish Kelpie is one of the most popular and well-known water spirits. An unsuspecting victim comes upon a malicious creature that poses as an innocent horse. Enticed to ride it, the victim soon finds himself magically unable to dismount and can only scream as the horse plunges beneath the waves to drown its meal. The story certainly speaks to the imagination, but there are actually many variants of it: The Norwegian Nøkk, the German Nixe, the Welsh Ceffyl Dŵr, the Flemish Nikker, the Icelandic Nykur and many others are all variations of the same creature.

This relation can also be seen in their etymology: most of these names are similar, because they are thought to be derived from an old Germanic term for washing (as in, bathing something in a river, like the horse monsters do with their victims in the stories).

But I’m digressing. One of the most obscure variations of the tale comes from the Shetland Islands. Here, people told stories about the monstrous Njuggel (also called Njogel, Njuggle and in northern Shetland ‘Shoopiltee’ or ‘Sjupilti’). Like its relatives, this creature is an aquatic horse, usually depicted as a horse with fins. It also has a wheel for a tail (or a tail shaped like the rim of a wheel, depending on who you ask), but most modern interpretations drop that detail. Its hooves are backwards.

It lives near waterways and lakes and pretends to be a peaceful horse, taking care to hide its strange tail between its legs. Though it usually takes the form of a particularly beautiful horse, sometimes it is an old, thin horse. When a traveller finds the Njuggel, the creature influences them and convinces them to mount it. When the victim climbs into the saddle however, the creature runs away to the nearest lake to drown its prey. It runs at an extremely high speed, keeping its wheel-tail in the air. After accelerating to a high speed, its hooves burst in flames and its nostrils emit smoke or fire.

The victim cannot dismount, but if they can speak the monster’s name out loud, the Njuggel loses its powers and the victim can escape. What happens then varies between stories: sometimes the creature slows down and can be dismounted, and sometimes he vanishes into thin air.

Sometimes, you can see them at night: such sightings usually involve a white or grey horse emerging from water and run some distance before disappearing in a flash of light.

The Njuggel is not entirely the same creature as the Kelpie and the Ceffyl Dŵr. It has a connection with watermills and demands offerings such as flour and grain. If these gifts cease, it will halt the wheel of its mill. To avoid having to offer grain to this creature, people would light fires when a Njuggel appeared, for they are afraid of flames (usually peat was burned, although throwing a torch also did the trick). There is a story in Tingwall about a group of young men who tried to capture a Njuggel for themselves. They succeeded in chaining the creature but couldn’t hold it for long, and the Njuggel broke free and fled. But the standing stone to which it was chained is still there between the Asta and Tingwall lochs, and the marks that were supposedly made by the chain can still be seen.

Sources:

Lecouteux, C., 2016, Encyclopedia of Norse and Germanic Folklore, Mythology, and Magic.

Marwick, E., 2020, The Folklore of Orkney and Shetland, Birlinn Ltd, 216 pp.

Teit, J. A., 1918, Water-beings in Shetlandic Folk-Lore, as Remembered by Shetlanders in British Columbia, The Journal of American Folklore, 31(120), p.180-201.

(image source: Davy Cooper. Illustration for ‘Folklore from Whalsay and Shetland’ by John Stewart)

#Scottish mythology#Shetland mythology#water horse#aquatic creatures#monsters#mythical creatures#mythology

389 notes

·

View notes