#Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali

Photo

Rob Schouten, Still Point

* * *

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali: Meditation, part V

“41. The mind that has been so trained that the ordinary modifications of its action are not present, but only those which occur upon the conscious taking up of an object for contemplation, is changed into the likeness of that which is pondered upon, and enters into full comprehension of the being thereof.

42. This change of of the mind into the likeness of what is pondered upon, is technically called the Argumentative condition, when there is any mixing-up of the title of the thing, the significance and application of that title, and the abstract knowledge of the qualities and elements of the thing per se.

43. On the disappearance, from the plane of contemplation, of the title and significance of the object selected for meditation; when the abstract thing itself, free from distinction by designation, is presented to the mind only as an entity, that is what is called the Non-Argumentative condition of meditation. ...

45. That meditation which has a subtile object in view ends with the indissoluble element called primordial matter.

45. The mental changes described in the foregoing, constitute ‘meditation with its seed.’

‘Meditation with its seed’ is that kind of meditation in which there is still present before the mind a distinct object to be meditated upon.

47. When Wisdom has been reached, through acquirement of the non-deliberative mental state, there is spiritual clearness.

48. In that case, then, there is that Knowledge which is absolutely free from Error.

49. This kind of knowledge differs from the knowledge due to testimony and inference; because, in the pursuit of knowledge based upon those, the mind has to consider many particulars and is not engaged with the general field of knowledge itself.

50. The train of self-reproductive thought resulting from this puts a stop to all other trains of thought. ...

51. This train of thought itself, with but one object, may also be stopped, in which case ‘meditation without a seed’ is attained.

‘Meditation without a seed’ is that in which the brooding of the mind has been pushed to such a point that the object selected for meditation has disappeared from the mental plane, and there is no longer any recognition of it, but consequent progressive thought upon a higher plane.”

— William Q. Judge, The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali (Book I)

#Rob Schouten#Still Point#Art#Beauty#Painting#Visionary#William Q. Judge#Patanjali#Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali#The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali#Meditation#Wisdom

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali: Meditation, part I

“1. Fixing the mind on a place, object, or subject is attention.

This is called Dharana.

2. The continuance of this attention is contemplation.

This is called Dhyana.

3. This contemplation, when it is practiced only in respect to a material substance or object of sense, is meditation.

This is called Samadhi.

4. When this fixedness of attention, contemplation, and meditation are practiced with respect to one object, they together constitute what is called Sanyama. …

5. By rendering Sanyama—or the operation of fixed attention, contemplation, and meditaiton—natural and easy, an accurate discerning power is developed.

This ‘discerning power’ is a distinct faculty which this practice alone develops, and is not possessed by ordinary persons who have not pursued concentration.

6. Sanyama is to be used in proceeding step by step in overcoming all modifications of the mind, from the more apparent to those the most subtle. …

9. There are two trains of self-reproductive thought, the first of which results from the mind being modified and shifted by the object or subject contemplated; the second, when it is passing from that modification and is becoming engaged only with the truth itself; at the moment when the first is subdued and the mind is just becoming intent, it is concerned in both of those two trains of self-reproductive thought, and this state is technically called ‘Nirodha’.

10. In that state of meditation which has been called Nirodha, the mind has an uniform flow.

11. When the mind has overcome and fully controlled its natural incnlination to consider diverse objects, and begins to become intent upon a single one, meditation is said to be reached.”

— William Q. Judge, The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali (Book III)

In The Beginning

by Rob Schouten

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

The concept of Sthira and Sukha in yogic philosophy alludes to exactly that; the polarized yet completely balanced nature of life. These two concepts are found in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, a collection of 196 Sutras (aphorisms) on the theory and practice of yoga.

This sentence can be roughly translated as “postures should be stable and comfortable”, and it is also often reworded as the balance between “effort” and “ease.

#stillness#meditation#mindfulness#nature#peace#love#yoga#healing#gratitude#silence#selfcare#spirituality#breathe#calm#awaren#selflove#life#consciousness#innerpeace#presence#naturephotography#awakening#wisdom#quiet#meditate#photography#mentalhealth

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

HEART BEAT

Date: 28 May 2023

1 Duration: 45 minutes at 5:31 PM

2 Duration: 42 minutes at 11:03 PM

Depth:

During the evening meditation at the temple, I went from an absence of cheer to its presence. The evening session changed the cheer levels in me dramatically.

I heard a sound during the nightly session. It was the inner ear that was picking it up. In fact, the sound removed me out of the depths I was at. Once my attention reached the conscious level of mind, I couldn’t hear the sound.

From the little that I have read on the internet with regards the phenomenon of hearing stuff during meditation, I understand that I was hearing my own heart beating. There was a steady rhythm to the sound. And it was nothing like the sounds described as corresponding to higher chakras.

Each Kundalini chakra is said to have its own vibe. It is also said that an optimal depth of meditation at any of the chakras can make itself heard. As I write about it, I am reminded of the time I came up with a plausible explanation for ear related meditational phenomenon.

Swami Vivekananda, in his book Raja Yoga, has interpreted Patanjali’s aphorisms in Sanskrit to English. In one such interpreted line, the Swami speaks of the sensation of oil in the ears. More than a decade after reading the book, I actually experienced the sensation.

As a child at school, I could turn awfully nauseous with the sound of chalk scratching against black boards. A sound reaching my ears can cause sensations in my belly. It’s almost as if certain sounds are bonded in the mind with certain bodily sensations.

The sensation of oil in the ear has so much to do with how well one is conducting a purely mental chant. A smooth chant sans mental interruptions, is a well lubricated chant in the head. A chant in the head that has caught a groove in one’s mental gear can leave one with a real feeling of oil in the ears.

Life energies run like a stream in one’s cerebrospinal set-up after enough life energies have been withdrawn into the cerebrospinal set-up. I don’t see why such a stream of life sustaining energy won’t have its own vibe. I don’t see why such a vibe won’t be heard by a meditating human’s head.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yoga Philosophy and Ethics: Living a Yogic Lifestyle

Yoga, beyond its physical postures and breathing exercises, encompasses a rich philosophy and a set of ethical principles that guide practitioners toward a life of harmony, self-awareness, and compassionate action. Rooted in ancient Indian traditions, yoga philosophy offers a holistic framework for living that extends beyond the confines of the mat. Whether it's practiced in the serene landscapes of India or a tranquil yoga retreat center in Portugal, this philosophy encourages individuals to cultivate mindfulness, self-discovery, and ethical conduct in their everyday lives.

Central to yoga philosophy are the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, a collection of aphorisms that serve as a foundational text for understanding the principles of yoga. These sutras outline the eightfold path, known as Ashtanga Yoga, which provides a comprehensive roadmap for living a yogic lifestyle. The eight limbs are yama (ethical restraints), niyama (observances), asana (physical postures), pranayama (breath control), pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation), and samadhi (self-realization).

The yamas and niyamas form the ethical foundation of the yogic path. Yamas are universal moral principles that guide one's interactions with the external world, including ahimsa (non-violence), satya (truthfulness), asteya (non-stealing), brahmacharya (moderation), and aparigraha (non-possessiveness). Niyamas are personal observances that foster inner growth, including saucha (cleanliness), santosha (contentment), tapas (discipline), svadhyaya (self-study), and Ishvara pranidhana (surrender to a higher power).

These ethical guidelines encourage practitioners to cultivate qualities that extend beyond personal gratification and contribute to the well-being of oneself and others. Ahimsa, for instance, calls for a commitment to non-violence not only in actions but also in thoughts and words. This principle challenges individuals to develop empathy, compassion, and a deep respect for all living beings, fostering a sense of interconnectedness.

Santosha invites individuals to find contentment in the present moment, acknowledging the impermanent nature of external circumstances. By cultivating contentment, practitioners shift their focus from external achievements to inner peace and happiness, reducing the constant pursuit of material gains that often leads to stress and dissatisfaction.

Pranayama, the practice of breath control, serves as a bridge between the physical and mental aspects of yoga. It not only enhances lung function and oxygenation but also regulates the mind and emotions. Through conscious breathwork, individuals learn to harness their breath as a tool for self-awareness, emotional regulation, and mental clarity.

The later limbs of yoga, including meditation and self-realization, lead practitioners toward a deeper understanding of themselves and the universe. Dharana, or concentration, hones the mind's focus, preparing it for meditation (dhyana). As meditation deepens, the practitioner enters a state of samadhi—an experience of profound oneness, where the individual transcends the ego and attains a sense of unity with all existence.

Living a yogic lifestyle is not about perfection but about cultivating awareness, intention, and effort in every aspect of life. It's about aligning one's actions, thoughts, and behaviors with the principles of yoga philosophy. This can manifest in simple acts of kindness, ethical decision-making, and conscious living that uplift both the individual and the world around them.

In a world often characterized by haste and disconnection, yoga philosophy and ethics offer a timeless guide for navigating the complexities of human existence. By integrating the principles of the eightfold path into their lives, individuals embark on a transformative journey toward self-realization, inner peace, and harmonious interactions with the world. Yoga becomes not just a practice on the mat, but a way of life that fosters balance, mindfulness, and the pursuit of higher consciousness.

0 notes

Text

Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, The Eight Limbs of Yoga Explained

Exploring the core of the 8 limbs of yoga

The timeless wisdom of the 8 limbs of yoga, as outlined in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, remains a fundamental aspect of this classical philosophical work. By delving into their original context, we shed light on why these 8 limbs continue to hold relevance for modern yoga practice and contemporary living.

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali serve as a valuable guide for leading a balanced and ethical life, both within the confines of the yoga mat and beyond. Among the 195 aphorisms that form a comprehensive "Theory of Everything," the focus of modern yoga often centers on the 31 verses that expound upon the 'eight limbs' of yoga, offering a pragmatic roadmap to attain freedom from suffering. Appreciating the historical backdrop of this ancient text allows us to apply its principles to our present-day lives.

So, what exactly are the 8 limbs of yoga?

Yama (restraints)

The yamas encompass five ethical precepts that govern our interactions with the world. These principles include Ahimsa (non-violence), Satya (truthfulness), Asteya (non-stealing), Brahmacharya (celibacy), and Aparigraha (non-coveting).

Niyama (observances)

The niyamas focus on self-improvement and personal growth, encompassing Saucha (purification), Santosa (contentment), Tapas (asceticism), Svadhyaya (study), and Ishvara Pranidhana (dedication to god/master).

Asana (posture)

Originally referring to finding a comfortable seat for meditation, today, asana encompasses all yoga poses and postural practices.

Pranayama (breath control)

Patanjali highlights the significance of regulating the breath's inhalations, exhalations, and retentions to prepare for meditation.

Pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses)

Pratyahara involves disengaging consciousness from sensory distractions, paving the way for inner focus and mindfulness.

Dharana (concentration)

During Dharana, practitioners direct their attention to a single point of focus, such as the navel or a mental image.

Dhyana (meditation)

Dhyana entails meditating on a single object of attention, excluding all other thoughts, leading to a state of heightened awareness and concentration.

Samadhi (pure contemplation)

In the pinnacle stage of Dhyana, practitioners experience Samadhi, a profound state of merging with the object of meditation, often described as a heightened state of spiritual awareness.

Understanding and incorporating the 8 limbs of yoga into one's practice can lead to transformative spiritual growth and a more meaningful life both on and off the yoga mat.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Patanjali is a significant figure in Indian history, particularly in the context of yoga and philosophy. However, it is important to note that the details of Patanjali's life and the exact timeframe in which he lived are not definitively known. The information available about him primarily comes from ancient texts, particularly his renowned work called the "Yoga Sutras."

Patanjali is believed to have lived sometime between the 2nd century BCE and the 4th century CE. He is revered as the compiler of the Yoga Sutras, a foundational text that systematized the philosophy and practice of yoga. The Yoga Sutras consists of 196 aphorisms or concise statements that provide guidance on various aspects of yoga, including ethical principles, meditation, and the attainment of spiritual liberation.

Patanjali is often considered the father of classical yoga, as his work served to organize and unify the diverse traditions and practices of yoga that existed at the time. He outlined the eightfold path of yoga known as Ashtanga Yoga, which consists of moral observances (yamas), self-disciplines (niyamas), physical postures (asanas), breath control (pranayama), withdrawal of the senses (pratyahara), concentration (dharana), meditation (dhyana), and samadhi (a state of profound meditation or union).

In addition to his contributions to yoga, Patanjali is also believed to have written works on grammar and Ayurveda, the traditional Indian system of medicine. However, these texts attributed to Patanjali are separate from the Yoga Sutras and are often referred to as the Mahabhashya (Great Commentary) and the Charaka Samhita, respectively.

Overall, Patanjali's influence on yoga and his systematic approach to its practice has had a profound impact on the development and understanding of yoga in India and around the world.

Introduction: Unraveling the Legacy of Patanjali

Hindu author, mystic, and philosopher Patanjali, also known as Gonardiya or Gonikaputra, was a Siddhar. Although no one knows for sure when he lived, estimates based on an examination of his writings indicate that it was between the second and fourth century CE.

He is thought to have written and compiled several Sanskrit books. The Yoga Sutras, a traditional yoga treatise, are the best of these. While there are other recognized historical authors with the same name, it is disputed if the sage Patanjali is the author of all the writings attributed to him. The question of the historicity or identity of this author or these authors has received a lot of scholarly attention during the past century.

Patanjali's Life and Historical Context

The word "Patanjali" is a composite name from "patta," which is Sanskrit for "falling" and "aj," which means "honor, celebrate, beautiful," or "ajali," which means "reverence, uniting palms of the hands."

According to legend, the sage Patajali obtained Samadhi at the Brahmapureeswarar Temple in Tirupattur, Tamil Nadu, India, through yogic meditation. Within the Brahmapureeswarar Temple complex, the sage Patanjali's Jeeva Samadhi, which is currently a closed meditation hall, is located next to Brahma's shrine.

Patanjali's life remains shrouded in mystery and uncertainty, with limited historical records available to provide concrete details. As a result, much of what is known about him is derived from legends, traditional accounts, and the inferences made from his writings.

The exact dates of Patanjali's birth and death are unknown, and even his identity as an individual person is subject to debate. Some scholars propose that Patanjali may have been a compilation of multiple sages who contributed to the texts attributed to him. Nevertheless, the influence of Patanjali's teachings and writings, particularly the Yoga Sutras, cannot be denied.

Patanjali is said to have lived during a significant era in Indian history, commonly believed to be between the 2nd century BCE and the 4th century CE. This period marked a time of

cultural, intellectual, and philosophical development in ancient India, with various schools of thought emerging and flourishing.

Historical accounts depict India during Patanjali's era as a diverse and vibrant society, with a rich tapestry of philosophical and spiritual traditions. Buddhism, Jainism, and various Hindu philosophical systems coexisted and influenced each other. It was within this cultural milieu that Patanjali's teachings on yoga and spiritual liberation took shape.

Patanjali's contributions extend beyond his work on yoga. He is also credited with writing the Mahabhashya, a commentary on grammar, which provided significant insights into the linguistic and grammatical aspects of the Sanskrit language. Additionally, Patanjali is associated with the Charaka Samhita, an important Ayurvedic text that focuses on traditional Indian medicine.

While details about Patanjali's personal life are scarce, his impact on the development of yoga and philosophy is immense. His systematic approach to yoga in the form of the Yoga Sutras has provided a comprehensive guide for practitioners, emphasizing ethical principles, meditation techniques, and the attainment of spiritual enlightenment.

Patanjali's teachings have transcended time and continue to shape the modern understanding and practice of yoga. His legacy remains a subject of reverence and inspiration for yogis, philosophers, and spiritual seekers alike, as they explore the depths of yoga's transformative potential.

The Yoga Sutras: Uniting and Systematizing the Philosophies of Yoga

The Yoga Sutras of Patajali are a compilation of 195 sutras (aphorisms), according to Vysa and Krishnamacharya, and 196 sutras, respectively, on the philosophy and practice of yoga (according to others, including BKS Iyengar). The sage Patanjali in India collected and arranged knowledge about yoga from much older traditions to create the Yoga Sutras in the first decades CE.

The Yoga Sutras are well recognized for their mention of ashtanga, an eight-part practice that results in samadhi. The eight components are asana (yoga posture), yama (abstinences), niyama (observances), pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses), dharana (mind concentration), dhyana (meditation), and samadhi (absorption). The basic goal of practice is kaivalya, which involves separating purusha, the witness consciousness, from prakriti, the cognitive system, and freeing purusha from prakriti's jumbled impurities.

The Samkhya ideas of purusha and prakriti were the foundation for the Yoga Sutras, which are frequently regarded as additive to them. It shares a close relationship with Buddhism and uses some of its vocabulary. In contrast to the Bhakti traditions and Vedic ritualism that were popular at the time, Samkhya, Yoga, and Vedanta, as well as Jainism and Buddhism, can be considered as distinct manifestations of a broad stream of ascetic traditions in ancient India.

Exploring the Eight Limbs of Yoga: Ashtanga Yoga

Ashtanga yoga, sometimes known as "the eight limbs of yoga," is how Patanjali categorized ancient yoga in his Yoga Sutras . He identified the yamas (abstinences), niyamas (observances), asanas (postures), pranayamas (breathing), pratyaharas (withdrawals), dharanas (concentration), dhyanas (meditation), and samadhis as the eight limbs (absorption).

Yamas: Ethical Principles for Harmonious Living

In Hinduism, yamas are moral requirements that might be thought of as the "don'ts" in life. The five yamas that Patanjali enumerated in the Yoga Sutra

Ahimsa : Nonviolence, non-harming other living beings

Satya : truthfulness, non-falsehood

Asteya : non-stealing

Brahmacharya : chastity, marital fidelity or sexual restrain

Aparigraha : non-avarice, non-possessiveness

According to Patanjali, the virtue of nonviolence and non-harm to others (Ahimsa) leads to the giving up of animosity, which brings the yogi to the perfection of inner and exte

rior amity with everyone and everything.

Niyamas: Self-Disciplines for Personal Transformation

Niyama, or the "dos," is the second part of Patanjali's Yoga path and it consists of good deeds and observances.

Shaucha : purity, clearness of mind, speech and body

Santosha : contentment, acceptance of others, acceptance of one's circumstances as they are.

Tapas : persistence, perseverance, austerity, asceticism, self-discipline

Svadhyaya : study of self, self-reflection, introspection of self's thoughts, speech, and actions

Ishvarapranidhana : contemplation of the Ishvara God/Supreme Being .

The virtue of contentment and acceptance of others as they are (Santosha), according to Patanjali, leads to a state in which internal sources of joy matter most and the desire for external sources of pleasure fades.

Asanas: Physical Postures for Strength and Flexibility

An asana is a position that one can maintain for a while while remaining calm, stable, at ease, and motionless.

Siddhasana, which means "accomplished," Padmasana, "lotus," Simhasana, "lion," and Bhadrasana, which means "glorious," explains the motions of these four asanas as well as eleven more. Unlike any older type of yoga, asanas are prominent and abundant in modern yoga.

Pranayama: Harnessing the Power of Breath

The act of controlling one's breath consciously (inhalation, full pause, exhalation, and empty pause). This can be accomplished in a number of ways, such by inhaling for a moment before stopping, expelling for a moment before starting, slowing the inhalation and exhalation, or purposefully altering the timing and length of the breath (deep, short breathing)

Pratyahara: Withdrawing the Senses for Inner Focus

Drawing one's awareness inward is known as pratyahara. Retracting the sensory experience from outside objects is what it entails. It is a self-extracting and abstracting step.

Pratyahara is the deliberate closing of one's thought processes to the sensory world, not one's eyes to the sensory world. Pratyahara gives one the ability to quit being ruled by the outside world, focus on seeking self-knowledge, and enjoy the freedom that is natural in one's inner reality.

Dharana: Cultivating Concentration and Single-Pointedness

Dharana, the sixth limb of yoga, is the act of keeping one's attention on a specific inner condition, issue, or topic. The mind is fixed on a mantra, one's breath, the navel, the tip of one's tongue, or any other location, as well as an object one desire to watch or a thought or idea in one's head. Fixing the mind entails maintaining a single concentration, avoiding mental wandering, and refraining from switching between subjects.

Dhyana: Journeying into the Realm of Meditation

Dhyana is thinking, reflecting on whatever Dharana has been paying attention to. Dhyana is the contemplation of the personal deity that was the emphasis of the sixth limb of yoga. If only one thing was the focus, then dhyana is the impartial, unassuming observation of that thing. If a certain thought or concept were the emphasis, Dhyana would be thinking about it from every angle, manifestation, and result. Dhyana is an unbroken stream of consciousness, current of thinking, and flow of awareness.

Samadhi: Attaining Union with the Divine

In Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism, and yogic systems, samdhi (Pali and Sanskrit: ) is a state of meditative consciousness. It is the eighth and final component of the Noble Eightfold Path in Buddhism. It is the eighth and last limb in the Ashtanga Yoga system, according to Patanjali's Yoga Sutras.

Conclusion: Honoring the Legacy of Patanjali in the Contemporary World

One of the key texts for understanding classical Yoga philosophy, according to the modern yoga tradition, is Patajali's Yoga Sutras.

Between the ninth and sixteenth centuries, some of the most significant commentators on the Yoga Sutras were written. The school began to wane after the twelft

h century, and Patanjali's Yoga theory received few commentaries. Patanjali's yoga philosophy had all but disappeared by the fifteenth century. Since few people read the literature and it wasn't often taught, the Yoga Sutras manuscript was no longer replicated.

Wider interest in the Yoga Sutras emerged in the West with their rediscovery by a British Orientalist in the early 1800s. After Helena Blavatsky, head of the Theosophical Society, the practice of yoga according to the Yoga Sutras was recognized as the science of yoga and the "supreme contemplative path to self-realization" by Swami Vivekananda in the 19th century. According to White, "Big Yoga - the corporate yoga subculture" is the reason it has gained popularity in the West.

0 notes

Text

Patanjali is a significant figure in Indian history, particularly in the context of yoga and philosophy. However, it is important to note that the details of Patanjali's life and the exact timeframe in which he lived are not definitively known. The information available about him primarily comes from ancient texts, particularly his renowned work called the "Yoga Sutras."

Patanjali is believed to have lived sometime between the 2nd century BCE and the 4th century CE. He is revered as the compiler of the Yoga Sutras, a foundational text that systematized the philosophy and practice of yoga. The Yoga Sutras consists of 196 aphorisms or concise statements that provide guidance on various aspects of yoga, including ethical principles, meditation, and the attainment of spiritual liberation.

Patanjali is often considered the father of classical yoga, as his work served to organize and unify the diverse traditions and practices of yoga that existed at the time. He outlined the eightfold path of yoga known as Ashtanga Yoga, which consists of moral observances (yamas), self-disciplines (niyamas), physical postures (asanas), breath control (pranayama), withdrawal of the senses (pratyahara), concentration (dharana), meditation (dhyana), and samadhi (a state of profound meditation or union).

In addition to his contributions to yoga, Patanjali is also believed to have written works on grammar and Ayurveda, the traditional Indian system of medicine. However, these texts attributed to Patanjali are separate from the Yoga Sutras and are often referred to as the Mahabhashya (Great Commentary) and the Charaka Samhita, respectively.

Overall, Patanjali's influence on yoga and his systematic approach to its practice has had a profound impact on the development and understanding of yoga in India and around the world.

Introduction: Unraveling the Legacy of Patanjali

Hindu author, mystic, and philosopher Patanjali, also known as Gonardiya or Gonikaputra, was a Siddhar. Although no one knows for sure when he lived, estimates based on an examination of his writings indicate that it was between the second and fourth century CE.

He is thought to have written and compiled several Sanskrit books. The Yoga Sutras, a traditional yoga treatise, are the best of these. While there are other recognized historical authors with the same name, it is disputed if the sage Patanjali is the author of all the writings attributed to him. The question of the historicity or identity of this author or these authors has received a lot of scholarly attention during the past century.

Patanjali's Life and Historical Context

The word "Patanjali" is a composite name from "patta," which is Sanskrit for "falling" and "aj," which means "honor, celebrate, beautiful," or "ajali," which means "reverence, uniting palms of the hands."

According to legend, the sage Patajali obtained Samadhi at the Brahmapureeswarar Temple in Tirupattur, Tamil Nadu, India, through yogic meditation. Within the Brahmapureeswarar Temple complex, the sage Patanjali's Jeeva Samadhi, which is currently a closed meditation hall, is located next to Brahma's shrine.

Patanjali's life remains shrouded in mystery and uncertainty, with limited historical records available to provide concrete details. As a result, much of what is known about him is derived from legends, traditional accounts, and the inferences made from his writings.

The exact dates of Patanjali's birth and death are unknown, and even his identity as an individual person is subject to debate. Some scholars propose that Patanjali may have been a compilation of multiple sages who contributed to the texts attributed to him. Nevertheless, the influence of Patanjali's teachings and writings, particularly the Yoga Sutras, cannot be denied.

Patanjali is said to have lived during a significant era in Indian history, commonly believed to be between the 2nd century BCE and the 4th century CE. This period marked a time of

cultural, intellectual, and philosophical development in ancient India, with various schools of thought emerging and flourishing.

Historical accounts depict India during Patanjali's era as a diverse and vibrant society, with a rich tapestry of philosophical and spiritual traditions. Buddhism, Jainism, and various Hindu philosophical systems coexisted and influenced each other. It was within this cultural milieu that Patanjali's teachings on yoga and spiritual liberation took shape.

Patanjali's contributions extend beyond his work on yoga. He is also credited with writing the Mahabhashya, a commentary on grammar, which provided significant insights into the linguistic and grammatical aspects of the Sanskrit language. Additionally, Patanjali is associated with the Charaka Samhita, an important Ayurvedic text that focuses on traditional Indian medicine.

While details about Patanjali's personal life are scarce, his impact on the development of yoga and philosophy is immense. His systematic approach to yoga in the form of the Yoga Sutras has provided a comprehensive guide for practitioners, emphasizing ethical principles, meditation techniques, and the attainment of spiritual enlightenment.

Patanjali's teachings have transcended time and continue to shape the modern understanding and practice of yoga. His legacy remains a subject of reverence and inspiration for yogis, philosophers, and spiritual seekers alike, as they explore the depths of yoga's transformative potential.

The Yoga Sutras: Uniting and Systematizing the Philosophies of Yoga

The Yoga Sutras of Patajali are a compilation of 195 sutras (aphorisms), according to Vysa and Krishnamacharya, and 196 sutras, respectively, on the philosophy and practice of yoga (according to others, including BKS Iyengar). The sage Patanjali in India collected and arranged knowledge about yoga from much older traditions to create the Yoga Sutras in the first decades CE.

The Yoga Sutras are well recognized for their mention of ashtanga, an eight-part practice that results in samadhi. The eight components are asana (yoga posture), yama (abstinences), niyama (observances), pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses), dharana (mind concentration), dhyana (meditation), and samadhi (absorption). The basic goal of practice is kaivalya, which involves separating purusha, the witness consciousness, from prakriti, the cognitive system, and freeing purusha from prakriti's jumbled impurities.

The Samkhya ideas of purusha and prakriti were the foundation for the Yoga Sutras, which are frequently regarded as additive to them. It shares a close relationship with Buddhism and uses some of its vocabulary. In contrast to the Bhakti traditions and Vedic ritualism that were popular at the time, Samkhya, Yoga, and Vedanta, as well as Jainism and Buddhism, can be considered as distinct manifestations of a broad stream of ascetic traditions in ancient India.

Exploring the Eight Limbs of Yoga: Ashtanga Yoga

Ashtanga yoga, sometimes known as "the eight limbs of yoga," is how Patanjali categorized ancient yoga in his Yoga Sutras . He identified the yamas (abstinences), niyamas (observances), asanas (postures), pranayamas (breathing), pratyaharas (withdrawals), dharanas (concentration), dhyanas (meditation), and samadhis as the eight limbs (absorption).

Yamas: Ethical Principles for Harmonious Living

In Hinduism, yamas are moral requirements that might be thought of as the "don'ts" in life. The five yamas that Patanjali enumerated in the Yoga Sutra

Ahimsa : Nonviolence, non-harming other living beings

Satya : truthfulness, non-falsehood

Asteya : non-stealing

Brahmacharya : chastity, marital fidelity or sexual restrain

Aparigraha : non-avarice, non-possessiveness

According to Patanjali, the virtue of nonviolence and non-harm to others (Ahimsa) leads to the giving up of animosity, which brings the yogi to the perfection of inner and exte

rior amity with everyone and everything.

Niyamas: Self-Disciplines for Personal Transformation

Niyama, or the "dos," is the second part of Patanjali's Yoga path and it consists of good deeds and observances.

Shaucha : purity, clearness of mind, speech and body

Santosha : contentment, acceptance of others, acceptance of one's circumstances as they are.

Tapas : persistence, perseverance, austerity, asceticism, self-discipline

Svadhyaya : study of self, self-reflection, introspection of self's thoughts, speech, and actions

Ishvarapranidhana : contemplation of the Ishvara God/Supreme Being .

The virtue of contentment and acceptance of others as they are (Santosha), according to Patanjali, leads to a state in which internal sources of joy matter most and the desire for external sources of pleasure fades.

Asanas: Physical Postures for Strength and Flexibility

An asana is a position that one can maintain for a while while remaining calm, stable, at ease, and motionless.

Siddhasana, which means "accomplished," Padmasana, "lotus," Simhasana, "lion," and Bhadrasana, which means "glorious," explains the motions of these four asanas as well as eleven more. Unlike any older type of yoga, asanas are prominent and abundant in modern yoga.

Pranayama: Harnessing the Power of Breath

The act of controlling one's breath consciously (inhalation, full pause, exhalation, and empty pause). This can be accomplished in a number of ways, such by inhaling for a moment before stopping, expelling for a moment before starting, slowing the inhalation and exhalation, or purposefully altering the timing and length of the breath (deep, short breathing)

Pratyahara: Withdrawing the Senses for Inner Focus

Drawing one's awareness inward is known as pratyahara. Retracting the sensory experience from outside objects is what it entails. It is a self-extracting and abstracting step.

Pratyahara is the deliberate closing of one's thought processes to the sensory world, not one's eyes to the sensory world. Pratyahara gives one the ability to quit being ruled by the outside world, focus on seeking self-knowledge, and enjoy the freedom that is natural in one's inner reality.

Dharana: Cultivating Concentration and Single-Pointedness

Dharana, the sixth limb of yoga, is the act of keeping one's attention on a specific inner condition, issue, or topic. The mind is fixed on a mantra, one's breath, the navel, the tip of one's tongue, or any other location, as well as an object one desire to watch or a thought or idea in one's head. Fixing the mind entails maintaining a single concentration, avoiding mental wandering, and refraining from switching between subjects.

Dhyana: Journeying into the Realm of Meditation

Dhyana is thinking, reflecting on whatever Dharana has been paying attention to. Dhyana is the contemplation of the personal deity that was the emphasis of the sixth limb of yoga. If only one thing was the focus, then dhyana is the impartial, unassuming observation of that thing. If a certain thought or concept were the emphasis, Dhyana would be thinking about it from every angle, manifestation, and result. Dhyana is an unbroken stream of consciousness, current of thinking, and flow of awareness.

Samadhi: Attaining Union with the Divine

In Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism, and yogic systems, samdhi (Pali and Sanskrit: ) is a state of meditative consciousness. It is the eighth and final component of the Noble Eightfold Path in Buddhism. It is the eighth and last limb in the Ashtanga Yoga system, according to Patanjali's Yoga Sutras.

Conclusion: Honoring the Legacy of Patanjali in the Contemporary World

One of the key texts for understanding classical Yoga philosophy, according to the modern yoga tradition, is Patajali's Yoga Sutras.

Between the ninth and sixteenth centuries, some of the most significant commentators on the Yoga Sutras were written. The school began to wane after the twelft

h century, and Patanjali's Yoga theory received few commentaries. Patanjali's yoga philosophy had all but disappeared by the fifteenth century. Since few people read the literature and it wasn't often taught, the Yoga Sutras manuscript was no longer replicated.

Wider interest in the Yoga Sutras emerged in the West with their rediscovery by a British Orientalist in the early 1800s. After Helena Blavatsky, head of the Theosophical Society, the practice of yoga according to the Yoga Sutras was recognized as the science of yoga and the "supreme contemplative path to self-realization" by Swami Vivekananda in the 19th century. According to White, "Big Yoga - the corporate yoga subculture" is the reason it has gained popularity in the West.

0 notes

Text

The Fascinating History and Evolution of Yoga: Tracing its Origins and Spiritual Roots

This article delves into the rich history and spiritual origins of yoga, tracing its evolution from ancient times to the modern era. Through an exploration of its origins, development, and cultural influences, readers will gain a deeper understanding of the profound spiritual and philosophical traditions that have shaped this ancient practice into the diverse and multifaceted discipline that it is today.

Yoga is a spiritual and physical discipline that has been practiced for thousands of years, with roots dating back to ancient India. Over time, yoga has evolved and adapted to different cultures and contexts, becoming a widely popular practice with millions of practitioners around the world. In this article, we will explore the rich history and spiritual origins of yoga, tracing its evolution from ancient times to the modern era.

The Roots of Yoga

The origins of yoga can be traced back to ancient India, where it emerged as a spiritual practice over 5,000 years ago. The early yogis developed a system of physical and mental exercises that were designed to help them attain enlightenment and liberation from the cycle of birth and death.

Over time, yoga evolved into a complex system of spiritual and philosophical beliefs, with different schools of thought and practices emerging to meet the needs of different individuals and communities.

Origins in Ancient India

The exact origins of yoga are uncertain, as the earliest written records of the practice date back to the Vedic period (1500–500 BCE). The Vedas, a collection of ancient Sanskrit hymns and texts, contain references to yogic practices such as meditation, self-discipline, and the cultivation of wisdom and knowledge.

During the Upanishadic period (800–500 BCE), the spiritual practice of yoga began to take shape, with the development of the Upanishads, a collection of philosophical texts that explore the nature of the self and the universe.

The Role of Sage Patanjali

The modern practice of yoga owes much to the sage Patanjali, who is believed to have lived in India during the 2nd century BCE. Patanjali is credited with writing the Yoga Sutras, a collection of 196 aphorisms that provide a comprehensive guide to yoga practice and philosophy.

The Yoga Sutras outline the eight limbs of yoga, which include ethical principles, physical postures, breath control, meditation, and concentration. These practices are designed to help individuals achieve a state of harmony and balance, leading to greater physical and mental well-being.

Yoga in Indian Philosophy and Religion

Yoga has been an integral part of Indian philosophy and religion for thousands of years, with different schools of thought and practices emerging to meet the needs of different individuals and communities. While yoga is often associated with Hinduism, it has also had a profound influence on other Indian spiritual traditions such as Buddhism and Jainism.

The Philosophical Foundations of Yoga

Yoga is rooted in the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta, which holds that all reality is an expression of the ultimate reality, or Brahman. This philosophy emphasizes the unity of all things and the essential oneness of the self and the universe.

Yogic philosophy also places great emphasis on the cultivation of wisdom and knowledge, which is achieved through a combination of study, meditation, and self-discipline. Through these practices, individuals are able to gain insight into the nature of reality and achieve a state of inner peace and harmony.

Yoga’s Relationship with Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism

Yoga has had a profound influence on Hinduism, which is often regarded as the mother tradition of yoga. Many of the practices and teachings of yoga are found in Hindu scriptures such as the Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads, and yoga has long been an integral part of Hindu spiritual practice.

However, yoga has also had an important role to play in other Indian spiritual traditions such as Buddhism and Jainism. In Buddhism, for example, the practice of meditation is seen as a key component of spiritual practice, and many of the techniques used in meditation are similar to those used in yoga.

Similarly, in Jainism, yoga is seen as a means of achieving liberation from the cycle of birth and death, and many Jains incorporate yogic practices into their daily spiritual practice.

The Spread of Yoga Beyond India

Over time, yoga began to spread beyond India, with Indian spiritual leaders and gurus sharing their teachings with people in other parts of the world. Today, yoga is practiced by millions of people around the globe and has become a widely popular practice in the West.

The Influence of Indian Spiritual Leaders and Gurus

One of the key figures in the spread of yoga outside of India was Swami Vivekananda, a Hindu monk who traveled to the United States in the late 19th century to share his teachings with Western audiences. Vivekananda’s lectures on yoga and Vedanta were hugely popular and helped to introduce many Westerners to the practice of yoga for the first time.

Other Indian spiritual leaders and gurus who have played a role in spreading yoga include Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the founder of Transcendental Meditation, and B.K.S. Iyengar, the creator of Iyengar Yoga, a popular style of yoga that emphasizes precise alignment and the use of props to support the body in different poses.

The Popularization of Yoga in the West

In the 20th century, yoga began to gain popularity in the West, with many people seeing it as a way to improve their physical and mental health. Today, yoga is practiced by millions of people around the world and has become a mainstream practice in many parts of the West.

While some have criticized the commercialization of yoga and the way in which it has been adapted to suit Western tastes and preferences, many others see the spread of yoga as a positive development, helping to promote greater physical and mental well-being and a deeper sense of spiritual connection.

The Development of Modern Yoga Styles and Schools

As yoga has become more popular in the West, a wide variety of new yoga styles and schools have emerged, each with their own unique approach to practice and philosophy. Some of the most popular styles of yoga today include Hatha Yoga, Ashtanga Yoga, and Vinyasa Yoga, each of which emphasizes different aspects of the practice.

In addition, many modern yoga teachers have developed their own unique approaches to practice, incorporating elements of different yoga styles and combining them with other disciplines such as dance, martial arts, and even acrobatics.

The Benefits and Controversies of Yoga

While yoga is widely regarded as a beneficial practice that can help to improve physical and mental health, it is not without controversy. Some have criticized the commercialization of yoga, the cultural appropriation of yogic practices by Westerners, and the potential risks and limitations of certain yoga practices.

The Physical and Mental Benefits of Yoga

Despite these concerns, there is no denying the many physical and mental benefits of yoga. Studies have shown that regular yoga practice can help to improve flexibility, strength, and balance, reduce stress and anxiety, and improve overall health and well-being

The Controversies Surrounding Yoga

Despite the many benefits of yoga, the practice has also been subject to controversy and criticism, particularly in recent years. Some critics have argued that the commercialization of yoga has led to a watering-down of the practice, with some yoga classes emphasizing physical fitness and aesthetics over spiritual development and self-awareness.

Others have criticized the cultural appropriation of yoga, arguing that the Westernization of yoga has led to a disconnection from its Indian roots and a lack of respect for the cultural context in which the practice originated.

In addition, there have been concerns about the potential risks of certain yoga practices, particularly when practiced without proper guidance and instruction. Some yoga poses and sequences can put a significant amount of strain on the body, and may not be appropriate for all individuals.

The Future of Yoga

Despite these controversies, it seems clear that yoga will continue to play an important role in the spiritual and physical lives of millions of people around the world. As the practice continues to evolve and adapt to new cultural and social contexts, it is likely that we will see the emergence of new styles, schools, and approaches to yoga that reflect the changing needs and interests of practitioners.

At the same time, it will be important to remain mindful of the cultural origins of yoga, and to continue to explore the spiritual and philosophical dimensions of the practice, rather than reducing it to a mere physical exercise.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the origins of yoga can be traced back thousands of years to ancient India, where it was practiced as a means of spiritual development and self-awareness. Over time, yoga has spread beyond India to become a global practice, with millions of people around the world practicing yoga in a wide variety of styles and traditions.

While yoga has been subject to controversy and criticism, particularly in the West, its many physical and mental benefits make it a valuable practice for anyone seeking greater health and well-being. As we continue to explore the practice of yoga, it will be important to remain mindful of its origins and philosophical underpinnings, in order to fully appreciate its transformative potential.

from https://ift.tt/7opuC0n

0 notes

Text

What yoga is…

Yoga is a physical, mental, and spiritual practice that originated in ancient India around 5,000 years ago. It is said to have been developed by the Indus-Sarasvati civilization in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, which was a highly advanced and sophisticated civilization that flourished from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE. The earliest mention of the word “yoga” appears in the “Rig Veda”, a collection of ancient texts. The practice aims to create a union between body, mind, and spirit, as well as between the individual self and universal consciousness.

The word “yoga” comes from the Sanskrit word “yuj,” which means to unite or integrate. The practice of yoga aims to unite the mind, body, and spirit to create a sense of harmony and balance within oneself. The ancient Indian sage Patanjali is credited with writing the Yoga Sutras, a collection of 196 aphorisms that form the foundation of modern yoga philosophy.

Over the centuries, yoga has evolved and been influenced by different schools of thought and practices in India, including Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. In the early 20th century, yoga began to gain popularity in the Western world, with figures like Swami Vivekananda and Paramahansa Yogananda introducing the practice to a wider audience.

Today, yoga is practiced all over the world and has many different forms and styles, including Hatha yoga, Vinyasa yoga, Ashtanga yoga, and Kundalini yoga. While the physical postures and breath control techniques are often emphasized in modern yoga, the practice still retains its roots in spirituality and self-awareness.

Get More Info…

#yoga#yogaeverydamnday#yogalove#yogainspiration#yogapractice#yogalife#yogapose#yogajourney#yogaeverywhere#yogagirl#yogalifestyle#yogateacher#yogamom#yogachallenge#yogaeveryday#yogadaily#yogafit#yogaworkout#yogateachertraining#yogaretreat#yogameditation#yogaeverydamndaychallenge#yogainspired#YogaBenefits#YogaforBeginners#YogaClasses#YogaPractice#YogaMeditation#YogaRetreats#YogaWorkouts

0 notes

Text

Who Was Patanjali?

Patanjali was an ancient Indian sage who is believed to have lived sometime between the 2nd century BCE and the 4th century CE. He is best known for his compilation of the Yoga Sutras, a collection of 196 aphorisms or concise statements that describe the philosophy and practice of yoga.

The Yoga Sutras are considered one of the foundational texts of classical yoga, and they provide a framework for understanding the nature of the mind, the practice of meditation, and the attainment of spiritual liberation. Patanjali's teachings emphasize the importance of controlling the fluctuations of the mind, cultivating awareness, and developing a deep understanding of the true nature of the self.

In addition to his contributions to yoga philosophy, Patanjali is also credited with compiling a commentary on Sanskrit grammar known as the Mahabhasya, which is considered a seminal text in the field of Indian linguistics. While relatively little is known about Patanjali's life or background, his teachings have had a profound influence on the development of yoga and meditation practices throughout the world.

0 notes

Photo

Rob Schouten, Still Moon, No Mind

* * *

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali: Meditation, part I

“1. Fixing the mind on a place, object, or subject is attention.

This is called Dharana.

2. The continuance of this attention is contemplation.

This is called Dhyana.

3. This contemplation, when it is practiced only in respect to a material substance or object of sense, is meditation.

This is called Samadhi.

4. When this fixedness of attention, contemplation, and meditation are practiced with respect to one object, they together constitute what is called Sanyama. ...

5. By rendering Sanyama—or the operation of fixed attention, contemplation, and meditaiton—natural and easy, an accurate discerning power is developed.

This ‘discerning power’ is a distinct faculty which this practice alone develops, and is not possessed by ordinary persons who have not pursued concentration.

6. Sanyama is to be used in proceeding step by step in overcoming all modifications of the mind, from the more apparent to those the most subtle. ...

9. There are two trains of self-reproductive thought, the first of which results from the mind being modified and shifted by the object or subject contemplated; the second, when it is passing from that modification and is becoming engaged only with the truth itself; at the moment when the first is subdued and the mind is just becoming intent, it is concerned in both of those two trains of self-reproductive thought, and this state is technically called ‘Nirodha’.

10. In that state of meditation which has been called Nirodha, the mind has an uniform flow.

11. When the mind has overcome and fully controlled its natural incnlination to consider diverse objects, and begins to become intent upon a single one, meditation is said to be reached.”

— William Q. Judge, The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali (Book III)

#Rob Schouten#Still Moon No Mind#Art#Beauty#Painting#Visionary#Yoga Sutras#Patanjali#William Q. Judge#The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali#Meditation#Wisdom#Contemplation#Attention#Samadhi

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of the most prominent ancient texts on yoga is Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, a series of 196 aphorisms written in Sanskrit around 400 AD. Patanjali describes yoga as an eightfold path, consisting of eight mind-body disciplines to be mastered. Working through these eight "limbs’"is believed to bring the practitioner to an enlightened state of consciousness known as samadhi, in which it is possible to experience the true Self.The eight limbs of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are: 1.Yamas - Five social observances: ahimsa (non-violence), satya (truthfulness) asteya (non-stealing), brahmacharya (chastity) and aparigraha (non-possessiveness). 2.Niyamas - Five moral observances: saucha (purity), santosha (contentment), tapas (self-discipline), svadhyaya (self-study), ishvarapranidhana (devotion or surrender). 3.Asana - Yoga postures. 4.Pranayama - Breathing techniques as a means of controlling prana (vital life force energy). 5.Pratyahara - Withdrawal of the senses. 6.Dharana - Concentration. 7.Dhyana - Meditation. 8.Samadhi - Enlightenment or bliss.These eight limbs offer a systematic approach to calming the mind and finding liberation from suffering. The final three stages, dharana, dhyana and samadhi are collectively referred to as Samyama (integration) since they are considered to be inextricably linked.As such, concentration practices are understood to be the path to truly meditative states, which ultimately lead to samadhi. By this definition, meditation is not a thinking or evaluative practice, but rather a state of complete absorption.Samadhi is said to be a blissful and calm state of mind, in which the practitioner is no longer able to perceive the act of meditation or define any separate sense of self from it. In releasing the self from ego and the illusion of separation, samadhi is undisturbed by emotions such as desire and anger. As such, samadhi connects practitioners to their true Self as one with universal consciousness.

Samadhi by Miles Toland

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

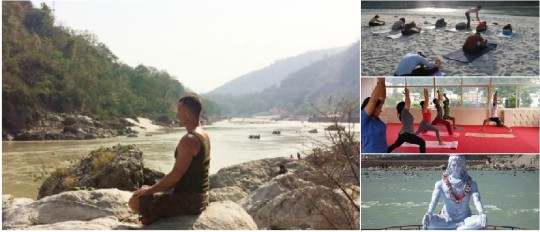

meditation retreat in rishikesh

meditation retreat in Rishikesh

The 3 days Himalayan Contemplation and Yoga Retreat at guruyogpeeth Yoga vihara in Rishikesh, India center is our shortest retreat over a duration of 3 days and 2. The 7 days Yoga and Contemplation Retreat at Yoga Vidya Mandiram in Rishikesh, India center is held over a duration of 7 days and 6 nights.

Yoga Vidya Mandiram is located in Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India. They offer registered yoga schoolteacher training programs and yoga retreats from the yoga capital.

Veda5 in Rishikesh is one of India's stylish Ayurveda, Panchakarma, and Yoga retreats where nature meets luxury and meets heartiness. Veda5 offers luxurious apartments.

The Meditation Retreat in Rishikesh India is 3, 6, 10, and 14 days, which starts every Monday and is available all time round. Come and witness yourself.

Spiritual retreats in Rishikesh, Enables you to enhance your control over your mind. Rishikesh Yog Shiksha offers you a one-week yoga retreat in India in a.

Contemplation Yoga Retreat in India & Stylish Yoga TTC in India. Namaste to all, are you curious about 200 Hour Yoga schoolteacher Training course and ready to take a step?

Vinyasa Yoga Vihara has positioned in a peaceful place and girdled by lush green mountains and fields. Keep in mind that our apartments are designed according to yoga.

Sattva yoga academe is the stylish most intertwined yoga and contemplation retreat in Rishikesh, grounded on the authentic and sacred training from the Himalayan.

At Yog Niketan by Sanskriti, we offer Yoga Retreats as well as diurnal Drop-in Yoga and Contemplation classes next to the swash Ganga in Ramjhula Rishikesh.

Ekam Drishti Yogshala offers the topmost yoga retreat in Rishikesh through a number of retreat programs, all of which are meant to give you a comforting.

At Maa Yoga Vihara, our aphorism is to give people quality Yoga Contemplation Retreats in Rishikesh, India, that are wholesome, and terrain-friendly,.

List of Spiritual Retreats in Rishikesh- Yoga, Contemplation, and Ayurveda- bravery Yoga Retreats in the World- Best Retreats Destinations- Retreats in India.

guruyogpeeth Ayurveda and yoga academy in Rishikesh provides stylish holiday Yoga Contemplation Retreats in Rishikesh India. This is the

better chance to stay.

The contemplation retreat of Ojashvi Yoga shala in Rishikesh is a great occasion to de–stress the impacts of the stressful situations of megacity life.

Peaceful and graphic beyond imagination, Rishikesh is a place where yogis have long come to seek spiritual enlightenment and further profound yoga practice. Indeed,.

Patanjali Yoga Foundation offers 14 days of affordable yoga and contemplation retreat in Rishikesh with a vihara stay for newcomers to advanced situations.

Rishikesh is a stylish place in India for spiritual enlightenment with world-class seminaries for yoga and contemplation. Your door to an enlightened spiritual life.

Join us for a Spiritual trip to Rishikesh through Yoga and Contemplation practice along with exploring places in and around Rishikesh.

Address: Guru Yog Peeth, Hotel Radha Krishna,

Badrinath Highway, Tapovan, Rishikesh 249192

Phone no = 8830322492

0 notes

Text

All translations and transliterations for Yoga Sutra 1:21

Source: Sanskrit transliteration from The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (Sri Swami Satchidananda)

TIVRA SAMVEGANAM ASANNAH

Source: English translation from The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (Sri Swami Satchidananda)

To the keen and intent practitioner this [samadhi] comes very quickly.

Source: Sanskrit transliteration from Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (B.K.S. Iyengar)

tivrasamveganam asannah

Source: English translation from Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (B.K.S. Iyengar)

The goal is near for those who are supremely vigorous and intense in practice.

Source: How to Know God: The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali (Swami Prabhavananda, Christopher Isherwood)

Success in yoga comes quickly to those who are intensely energetic.

Source: English translation from The Heart of Yoga (T.K.V. Desikachar)

The more intense the faith and the effort, the closer the goal.

Source: Sanskrit transliteration of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (Swami Jnaneshvara Bharati)

tivra samvega asannah)

Source: English translation of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (Swami Jnaneshvara Bharati)

Those who pursue their practices with intensity of feeling, vigor, and firm conviction achieve concentration and the fruits thereof more quickly, compared to those of medium or lesser intensity.

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://www.knewtoday.net/the-legacy-of-patanjali-unraveling-the-history-and-philosophy-of-yoga/

The Legacy of Patanjali: Unraveling the History and Philosophy of Yoga

Patanjali is a significant figure in Indian history, particularly in the context of yoga and philosophy. However, it is important to note that the details of Patanjali’s life and the exact timeframe in which he lived are not definitively known. The information available about him primarily comes from ancient texts, particularly his renowned work called the “Yoga Sutras.”

Patanjali is believed to have lived sometime between the 2nd century BCE and the 4th century CE. He is revered as the compiler of the Yoga Sutras, a foundational text that systematized the philosophy and practice of yoga. The Yoga Sutras consists of 196 aphorisms or concise statements that provide guidance on various aspects of yoga, including ethical principles, meditation, and the attainment of spiritual liberation.

Patanjali is often considered the father of classical yoga, as his work served to organize and unify the diverse traditions and practices of yoga that existed at the time. He outlined the eightfold path of yoga known as Ashtanga Yoga, which consists of moral observances (yamas), self-disciplines (niyamas), physical postures (asanas), breath control (pranayama), withdrawal of the senses (pratyahara), concentration (dharana), meditation (dhyana), and samadhi (a state of profound meditation or union).

In addition to his contributions to yoga, Patanjali is also believed to have written works on grammar and Ayurveda, the traditional Indian system of medicine. However, these texts attributed to Patanjali are separate from the Yoga Sutras and are often referred to as the Mahabhashya (Great Commentary) and the Charaka Samhita, respectively.

Overall, Patanjali’s influence on yoga and his systematic approach to its practice has had a profound impact on the development and understanding of yoga in India and around the world.

Introduction: Unraveling the Legacy of Patanjali

Hindu author, mystic, and philosopher Patanjali, also known as Gonardiya or Gonikaputra, was a Siddhar. Although no one knows for sure when he lived, estimates based on an examination of his writings indicate that it was between the second and fourth century CE.

He is thought to have written and compiled several Sanskrit books. The Yoga Sutras, a traditional yoga treatise, are the best of these. While there are other recognized historical authors with the same name, it is disputed if the sage Patanjali is the author of all the writings attributed to him. The question of the historicity or identity of this author or these authors has received a lot of scholarly attention during the past century.

Patanjali’s Life and Historical Context

The word “Patanjali” is a composite name from “patta,” which is Sanskrit for “falling” and “aj,” which means “honor, celebrate, beautiful,” or “ajali,” which means “reverence, uniting palms of the hands.”

According to legend, the sage Patajali obtained Samadhi at the Brahmapureeswarar Temple in Tirupattur, Tamil Nadu, India, through yogic meditation. Within the Brahmapureeswarar Temple complex, the sage Patanjali’s Jeeva Samadhi, which is currently a closed meditation hall, is located next to Brahma’s shrine.

Patanjali’s life remains shrouded in mystery and uncertainty, with limited historical records available to provide concrete details. As a result, much of what is known about him is derived from legends, traditional accounts, and the inferences made from his writings.

The exact dates of Patanjali’s birth and death are unknown, and even his identity as an individual person is subject to debate. Some scholars propose that Patanjali may have been a compilation of multiple sages who contributed to the texts attributed to him. Nevertheless, the influence of Patanjali’s teachings and writings, particularly the Yoga Sutras, cannot be denied.

Patanjali is said to have lived during a significant era in Indian history, commonly believed to be between the 2nd century BCE and the 4th century CE. This period marked a time of cultural, intellectual, and philosophical development in ancient India, with various schools of thought emerging and flourishing.

Historical accounts depict India during Patanjali’s era as a diverse and vibrant society, with a rich tapestry of philosophical and spiritual traditions. Buddhism, Jainism, and various Hindu philosophical systems coexisted and influenced each other. It was within this cultural milieu that Patanjali’s teachings on yoga and spiritual liberation took shape.

Patanjali’s contributions extend beyond his work on yoga. He is also credited with writing the Mahabhashya, a commentary on grammar, which provided significant insights into the linguistic and grammatical aspects of the Sanskrit language. Additionally, Patanjali is associated with the Charaka Samhita, an important Ayurvedic text that focuses on traditional Indian medicine.

While details about Patanjali’s personal life are scarce, his impact on the development of yoga and philosophy is immense. His systematic approach to yoga in the form of the Yoga Sutras has provided a comprehensive guide for practitioners, emphasizing ethical principles, meditation techniques, and the attainment of spiritual enlightenment.

Patanjali’s teachings have transcended time and continue to shape the modern understanding and practice of yoga. His legacy remains a subject of reverence and inspiration for yogis, philosophers, and spiritual seekers alike, as they explore the depths of yoga’s transformative potential.

The Yoga Sutras: Uniting and Systematizing the Philosophies of Yoga

The Yoga Sutras of Patajali are a compilation of 195 sutras (aphorisms), according to Vysa and Krishnamacharya, and 196 sutras, respectively, on the philosophy and practice of yoga (according to others, including BKS Iyengar). The sage Patanjali in India collected and arranged knowledge about yoga from much older traditions to create the Yoga Sutras in the first decades CE.

The Yoga Sutras are well recognized for their mention of ashtanga, an eight-part practice that results in samadhi. The eight components are asana (yoga posture), yama (abstinences), niyama (observances), pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses), dharana (mind concentration), dhyana (meditation), and samadhi (absorption). The basic goal of practice is kaivalya, which involves separating purusha, the witness consciousness, from prakriti, the cognitive system, and freeing purusha from prakriti’s jumbled impurities.

The Samkhya ideas of purusha and prakriti were the foundation for the Yoga Sutras, which are frequently regarded as additive to them. It shares a close relationship with Buddhism and uses some of its vocabulary. In contrast to the Bhakti traditions and Vedic ritualism that were popular at the time, Samkhya, Yoga, and Vedanta, as well as Jainism and Buddhism, can be considered as distinct manifestations of a broad stream of ascetic traditions in ancient India.

Exploring the Eight Limbs of Yoga: Ashtanga Yoga

Ashtanga yoga, sometimes known as “the eight limbs of yoga,” is how Patanjali categorized ancient yoga in his Yoga Sutras . He identified the yamas (abstinences), niyamas (observances), asanas (postures), pranayamas (breathing), pratyaharas (withdrawals), dharanas (concentration), dhyanas (meditation), and samadhis as the eight limbs (absorption).

Yamas: Ethical Principles for Harmonious Living

In Hinduism, yamas are moral requirements that might be thought of as the “don’ts” in life. The five yamas that Patanjali enumerated in the Yoga Sutra

Ahimsa : Nonviolence, non-harming other living beings

Satya : truthfulness, non-falsehood

Asteya : non-stealing

Brahmacharya : chastity, marital fidelity or sexual restrain

Aparigraha : non-avarice, non-possessiveness

According to Patanjali, the virtue of nonviolence and non-harm to others (Ahimsa) leads to the giving up of animosity, which brings the yogi to the perfection of inner and exterior amity with everyone and everything.

Niyamas: Self-Disciplines for Personal Transformation

Niyama, or the “dos,” is the second part of Patanjali’s Yoga path and it consists of good deeds and observances.

Shaucha : purity, clearness of mind, speech and body

Santosha : contentment, acceptance of others, acceptance of one’s circumstances as they are.

Tapas : persistence, perseverance, austerity, asceticism, self-discipline

Svadhyaya : study of self, self-reflection, introspection of self’s thoughts, speech, and actions

Ishvarapranidhana : contemplation of the Ishvara God/Supreme Being .

The virtue of contentment and acceptance of others as they are (Santosha), according to Patanjali, leads to a state in which internal sources of joy matter most and the desire for external sources of pleasure fades.

Asanas: Physical Postures for Strength and Flexibility

An asana is a position that one can maintain for a while while remaining calm, stable, at ease, and motionless.

Siddhasana, which means “accomplished,” Padmasana, “lotus,” Simhasana, “lion,” and Bhadrasana, which means “glorious,” explains the motions of these four asanas as well as eleven more. Unlike any older type of yoga, asanas are prominent and abundant in modern yoga.

Pranayama: Harnessing the Power of Breath

The act of controlling one’s breath consciously (inhalation, full pause, exhalation, and empty pause). This can be accomplished in a number of ways, such by inhaling for a moment before stopping, expelling for a moment before starting, slowing the inhalation and exhalation, or purposefully altering the timing and length of the breath (deep, short breathing)

Pratyahara: Withdrawing the Senses for Inner Focus

Drawing one’s awareness inward is known as pratyahara. Retracting the sensory experience from outside objects is what it entails. It is a self-extracting and abstracting step.

Pratyahara is the deliberate closing of one’s thought processes to the sensory world, not one’s eyes to the sensory world. Pratyahara gives one the ability to quit being ruled by the outside world, focus on seeking self-knowledge, and enjoy the freedom that is natural in one’s inner reality.

Dharana: Cultivating Concentration and Single-Pointedness

Dharana, the sixth limb of yoga, is the act of keeping one’s attention on a specific inner condition, issue, or topic. The mind is fixed on a mantra, one’s breath, the navel, the tip of one’s tongue, or any other location, as well as an object one desire to watch or a thought or idea in one’s head. Fixing the mind entails maintaining a single concentration, avoiding mental wandering, and refraining from switching between subjects.

Dhyana: Journeying into the Realm of Meditation

Dhyana is thinking, reflecting on whatever Dharana has been paying attention to. Dhyana is the contemplation of the personal deity that was the emphasis of the sixth limb of yoga. If only one thing was the focus, then dhyana is the impartial, unassuming observation of that thing. If a certain thought or concept were the emphasis, Dhyana would be thinking about it from every angle, manifestation, and result. Dhyana is an unbroken stream of consciousness, current of thinking, and flow of awareness.

Samadhi: Attaining Union with the Divine

In Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism, and yogic systems, samdhi (Pali and Sanskrit: ) is a state of meditative consciousness. It is the eighth and final component of the Noble Eightfold Path in Buddhism. It is the eighth and last limb in the Ashtanga Yoga system, according to Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras.

Conclusion: Honoring the Legacy of Patanjali in the Contemporary World

One of the key texts for understanding classical Yoga philosophy, according to the modern yoga tradition, is Patajali’s Yoga Sutras.

Between the ninth and sixteenth centuries, some of the most significant commentators on the Yoga Sutras were written. The school began to wane after the twelfth century, and Patanjali’s Yoga theory received few commentaries. Patanjali’s yoga philosophy had all but disappeared by the fifteenth century. Since few people read the literature and it wasn’t often taught, the Yoga Sutras manuscript was no longer replicated.

Wider interest in the Yoga Sutras emerged in the West with their rediscovery by a British Orientalist in the early 1800s. After Helena Blavatsky, head of the Theosophical Society, the practice of yoga according to the Yoga Sutras was recognized as the science of yoga and the “supreme contemplative path to self-realization” by Swami Vivekananda in the 19th century. According to White, “Big Yoga – the corporate yoga subculture” is the reason it has gained popularity in the West.

#Ashtanga Yoga#Ayurveda#Harmonius living#Meditation#Patanjali#Personal transformation#Philosophies of Yoga#Yoga

0 notes