#and create such a filmic translation of it all

Text

yeah Neruda (2016) really is that btch

#POETIC CINEMA#FR FR FR#i cried again#the sincerity the ability to explore his flaws and all and then still make it about his poetry#and the life of a poet#and create such a filmic translation of it all#and it has so much fun too !!!!!!#text#neruda 2016#also just makes you treasure how beautiful spanish is and it should hit better if you understand it vs the english subs yknow?#hey rec living latin american poets i should check out bc i've ran out (of ones i could find copies of anyway)#but also i should reread Canto General

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soviet union films that you should check out

Valerie and her week of wonders (Valerie a týden divů) (1970)

The film was directed by Jaromil Jireš in between 1969 and 1970, in Czechoslovakia (Czech Republic nowadays). It tells the story of Valerie, a 13-year-old girl whose life takes a new turn when she receives a pair of magic earrings. A wedding is coming to town and a whole new cast of characters, including vampires and a skunk, appear. Valerie has to come to terms with these new encounters and her own transition into puberty.

It was adapted from Vítězslav Nezval’s novel Valerie and her week of wonders, that was written in 1935, censored for ten years and then published in 1945. The novel is an explicit tribute to fairy tales and the gothic novel, which Nezval himself claims to be a part of. In his influences, he mentions Matthew Lewis' The Monk (1796), a novel for which he had commissioned a Czech translation from the authorities. He does indeed recycle the typical cast of the Gothic novel, such as the religious figures — through the figure of the monk and the cardinal — but also that of the vampire — with the grandmother and Tchoř. To this is added the dreamlike dimension, infused with surrealism vibes, which blurs the lines and gives a double identity to the surroundings of Valerie. In fact, her grandmother turns out to be a vampire, and even her mother. Tchoř, the cardinal, is also a vampire, but also Valerie's father. And Orlik, in addition to being the object of Valerie's desires, turns out to be her brother. The unclear status of the main characters creates a kaleidoscopic dimension, that gives the novel multiple levels of reading. This multi-layered story can then be seen as an attack by the author on the Catholic Church, its authority and its morality.

Jaromil Jireš’ film takes on with that idea though expends it, to make the film a criticism not only towards conservative morals, but also towards the communist regime. Indeed, Valerie struggles to exist as a film. It took Jireš two years to make his film because of several censorship threats from the Czech communist authorities. In addition to this, the political climate was not at its best after the resumption of the repression following Prague’s Spring in 1968. Hence the delay to shoot and then to edit and validate the film. In that sense, the criticism focuses on the desire for cultural uniformity imposed by communism — especially with socialist realism — which distorts the Czech national cultural legacy.

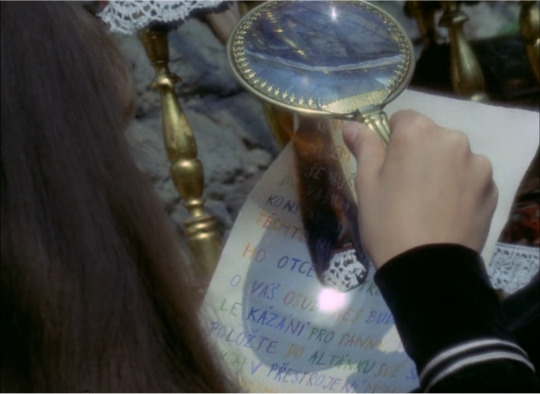

For example, there is a quite telling scene in the film that denounces censorship. Valerie receives a letter from her friend Orlik, and gets scared when her grandmother calls her for dinner. Fearing to be caught with the letter, Valerie decides to get rid of it by burning it with a magnifying glass. The shot that captures this moment shows us the young girl in the lead, from behind, revealing the contents of the letter written in rainbow colored letters. Here, the text even is perceptible in the film, since it is really the words spoken by the character of Orlik. However, the fact that Valerie burns the letter shows that the text has been eroded in favor of the filmic. The explanation for this sequence seems to lie in the dream. The very appearance of the letter, written in a mixture of colors, tends to evoke the realm of dreams. Thus, the action of burning the letter negates the reality of the letter and its speech. Hiding the words on the screen is indeed a way for Jaromil Jireš to also tell the viewer that there is censorship going on. What is all the more interesting having in mind that the novel as well as the film were both censored by the authorities.

Link to watch the film : https://youtu.be/rVKRR_gjSO8

J.A Lenourichel

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sessão Mutual Films: Nossa própria imagem, um espelho de beleza: Os filmes de Camille Billops e James Hatch [Mutual Films Session: Our Own Image, A Mirror of Beauty: The Films of Camille Billops and James Hatch]

March 11: The link above leads to Portuguese-language information about the 22nd edition of the Mutual Films Session, co-curated and organized by me and Mariana Shellard, whose screenings will take place between March 12th and 31st at the São Paulo-based unit of the Instituto Moreira Salles and on March 23rd and 30th at the newly opened screening room of the Instituto's unit in Poços de Caldas.

The event provides Brazil-based audiences with the country's first-ever retrospective of the films of Camille Billops (1933-2019) and James Hatch (1928-2020), a team of American artists and archivists that made brilliantly self-reflexive documentaries, several of which are focused on members of Billops's family, who come to represent different aspects of African-American life. The films investigate with profundity, wit, and humor an American condition of cracked interiors covered up by smooth surfaces, with the eternal hope of creating a less hypocritical and more open world.

The series's three programs will present newly digitized copies of all six of the films made by Billops and Hatch (who, among other things, founded the Hatch-Billops Collection, currently stored at Emory University and one of the largest extant archives devoted to African-American art and culture). Five of the films have been remastered in 2K, an initiative undertaken by their longtime distributor, the New York-based Third World Newsreel. The sixth - the couple's remarkable early portrait film of one of Billops's cousins called Suzanne, Suzanne - has been restored in 4K by the nonprofit entity IndieCollect.

The filmic works of Billops and Hatch received much positive feedback during the directors' lifetimes, but their reception has experienced a renaissance during the past few years thanks in good part to the availability of these new copies. Among critical texts that have recently been published, a piece by Yasmina Price written in conjunction with a streaming series of the couple's films on The Criterion Channel is particularly full. Contemporary researchers are fortunate to be able to have access to multiple interviews that Billops gave, including a long conversation from 1996 with bell hooks (included in hooks's book Reel to Real: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies, whose Brazilian edition was published late last year by Editora Elefante) and a 1992 talk with Ameena Meer for BOMB Magazine that we were fortunate to be able to translate into Portuguese for our website.

The series's opening screening in São Paulo on March 12th will include a public post-screening conversation about Billops and Hatch's films with Aline Motta, an important contemporary Brazilian artist whose multidisciplinary works contain points of resonance with the couples' projects. The series is dedicated to the memory of the German filmmaker and activist Renate Sami, and it could also easily be dedicated to the memory of Philip Shellard, a quiet and generous recently deceased cinephile whose accomplishments include being Mariana's father and a figure of unrelenting support.

0 notes

Text

Analytical Application 2

Shot:

The “shot” in film is a series of frames in continuous action without a cut between them. Regarding semiology, “the ‘shot’—an already complex unit, which must be studied—remains an indispensable reference for the time being, in somewhat the same way that the “word” was during a period of linguistic research,” (1) meaning that it is a building block for the filmic language essential for understanding the semiology of cinema.

The poster for the 2007 film Talk To Me incorporates several different shots. While the poster as a medium, unlike film, lacks the ability to show a moving, “alive” sequence, this poster attempts to convey multiple different points of information through the presentation of several locations and characters. While Metz concludes that there are other optical devices within cinema that can convey information, (2) the only one translatable to the poster is the shot. This poster frames characters in different shot sizes, suggesting a difference in importance between those with a larger frame that is close-up compared to those with a smaller frame that shows less detail. Additionally, the inclusion of a shot of the Capitol building from a skewn angle is an effective use of the mechanics of the shot in order to portray a disorder created at that specific location. More detailed shots taken directly from the film are present on the poster, but are difficult to see due to the distortion in their shape and their size relative to other shots, proving somewhat ineffective in providing insight into specific visuals from the film. The shots of the characters were taken outside of the context of the film, likely for promotional purposes, which fails to place these characters into the context of the narrative. These shots convey considerably less information than shots from the film, which may have been purposeful in order to not overstimulate the viewer of the poster and instead cause them to wonder what happens to the characters throughout the course of the story.

Myth:

“Myth” refers to the framework and value given to a specific sign based on both the way it is delivered and the external and pre-acknowledged factors that surround its reception. Barthes writes that “Myth is a type of speech,” (3) and that it is defined “by the way in which it utters this message,” (4) meaning that its communicative significance lies in the form in which it is implemented.

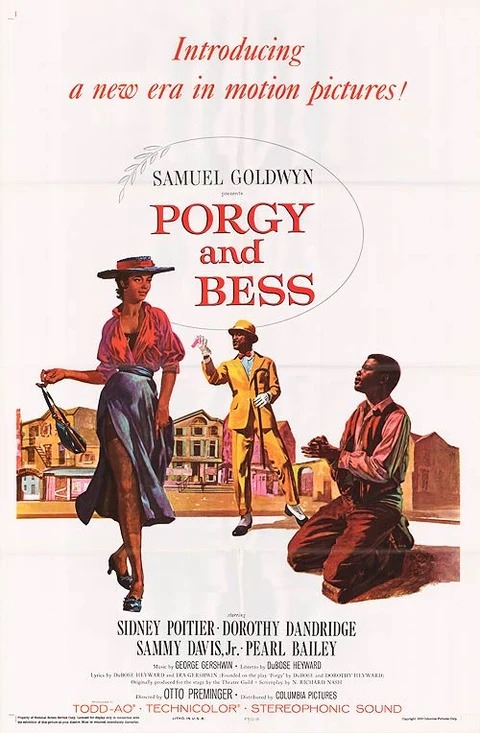

The poster for the 1959 film “Porgy and Bess” depicts three black characters in what seems to be a western town. With the predisposed mythology I’ve acquired from knowledge of cinematic history, it seems that this film may be an unfair, caricatured representation of people of color in the American west. In 1959, the film industry (as well as the country) still carried heavy racial prejudice, and it was often carried out through a negative depiction of people of color in films. Barthes writes that “all the materials of myth presuppose a signifying consciousness.” (5) Applied to this poster, the depiction of a man on his knees in front of a woman walking proudly and confidently reminds me of films such as Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, Grease, and Moulin Rouge! in which a male protagonist spends the whole film attempting to win the approval of a woman, giving me a clue as to what the narrative may be like. In the background, Sammy Davis Jr.’s character in a yellow suit with white gloves and a cane elicits a myth of showmanship, as my previous knowledge of Sammy Davis Jr. as a stage performer along with the connotations of his costume assume such a persona. In many films from the 1950s, there is a side character present for comedic relief and support for the protagonist. Davis Jr.’s character seems to be just that, suggested by his presence behind both of the other characters on the poster and by my preconceived notions of him and his costume.

Semiotics of the Cinema:

The semiotics of the cinema refers to the language of which cinema is constructed, using visual signs and signifiers in relation to one another in order to construct a narrative. Metz writes that “the semiotics of the cinema must frequently consider things from the point of view of spectator rather than of filmmaker,” (6) meaning that the cinematic language should be built in a way that makes it easiest for the audience to understand.

The film Conquered City came out in 1962, six years before Metz’s Some Points In the Semiotics of the Cinema was written. While the concept of cinema as a semiotic language had not yet existed, the film’s poster still employs concepts and ideas that Metz would define afterward. Metz’s notion that in order to make the most effective film the filmmakers must heavily consider the perspective of the audience is strongly utilized in this poster’s design. (7) The tagline uses dramatic language and an exclamation point to build a simplified tension, the exact type of tension it predicts its audiences are looking for in the film. “David Niven vs. Ben Gazzara” in big letters emphasizes the presence of the two actors, using them as a draw for audiences. In that time, and even now, a lot of people went to see movies based on who acted in them. The film is capitalizing on this by displaying the star-studded cast above anything else, in order to drive the most sales (in contrast, director Joseph Anthony’s name is barely visible at the bottom of the poster). Because this film was released before the concept of the semiotics of cinema was established, it fails to capitalize on the effectiveness of the “shot” and its similarity to the effectiveness of the word in linguistics. (8) Only one shot is present on the poster, and its size is diminished compared to that of the actors. While it does introduce the romanticism that is present in the film, a romanticism that will likely draw audiences, the poster designers could’ve used more shots in order to make the poster more emotionally effective.

Cinematic Language:

The Language System is a structure of individual units where each unit’s importance is based on its relationship with the units around it. Saussure defines it as “a system of interdependent terms in which the value of each term results solely from the simultaneous presence of the others.” (9) The building blocks of this language are units that can stand in for another unit, or units that can have value through being put in relation with one another. Saussure writes that language is always composed of “a dissimilar thing that can be exchanged for the thing of which value is determined” (10) and of “similar things that can be compared with the thing of which the value is to be determined.” (11)

The poster for the 1990 film Nuns on the Run serves as an example of how visual language can be used to elicit a certain tone within the viewer. The terms of the wanted poster and the actual nuns themselves placed in juxtaposition with one another signifies an irony, as they should be in jail while they are clearly out in the open air. This also clearly outlines the film’s main plotline. Barthes writes that signs can be indicative of moral feeling, (12) an internal emotion signified by an external visual. Here, the worried and alert faces of the men dressed in nun costumes utilizes the language system to signify their sinister intentions, as well as the actors’ over-caricatured portrayal of emotions. Saussure claims that language is assimilated by the individual, (13) which means that the signification each individual receives a sign with can be unique. One can view this poster as a crime thriller, not taking in the comedic nature of the taglines or aware of actor Eric Idle’s background as a comedian. Yet, “language is concrete,” (14) meaning that while people may have different interpretations of the sign, the sign itself does not change: each reproduction of the poster contains the same information. Saussure further writes that “in language there are only differences,” (15) and this is on display with the difference in the visual depiction of both protagonists in their mugshot versus them in the nun costume. Without the mug shots, one might assume that they are actually nuns, or have no reason to think they’re not other than their gender. But in conversation with the nun poster, their true characterization is more apparent.

Signified:

What is signified, also known as the “concept,” (16) is the internal meaning that a sign unlocks within the recipient, a signal of what the sign means. For example, the sign of a stop sign leads to the concept of one stopping at the stop sign. Saussure writes that “the bond between the signifier and the signified is arbitrary,” (17) in that it is up to the interpretation of each individual as they receive the sign.

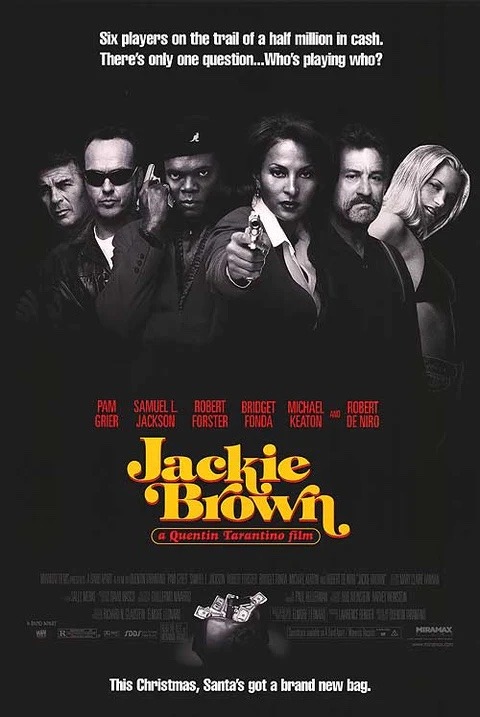

The poster for the 1997 film Jackie Brown contains a multitude of signs that create concepts in the mind of the viewer. Because of the uniqueness of each individual’s signification of signs, I am only able to speak for the connotations that I myself receive from the poster. Firstly, the presence of guns signifies the concept of the “gun”, which I associate with violence. This signification is reinforced by my knowledge of director Quentin Tarantino’s work and its bloody nature. The concept of the title in stylish red-and-yellow letters contains a connotation of retroness, leading me to infer that the film either takes place in the 1970s or, like the letters of the poster, is simply created in the style of the 1970s. On their own, the two crumpled bills at the bottom don’t allude to a large amount of money, but that image in relation to the “half a million in cash” described at the top of the poster creates an image in my mind of a large duffel bag full of money, the concept of “wealth”. The fact that the poster mentions Christmas leads me to infer that the film itself takes place during the holiday season. This is a clever marketing trick, in that it could lead one to associate the concept of the film “Jackie Brown'' with the concept of “Christmas”, making them more likely to watch it during that time. Lastly, the depiction of the characters in sleek black-and-white photography alludes to the concept of the black and white visuals, which I connect to the noir film, leading me to infer that this film will be a mystery or a thriller.

(1) Christian Metz, “Some Points in the Semiotics of the Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 70

(2) Metz, Semiotics of the Cinema, 71

(3) Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers (New York: The Noonday Press, 1972), 107

(4) Barthes, Mythologies, 107

(5) Barthes, Mythologies, 108

(6) Metz, Semiotics of the Cinema, 69

(7) Metz, Semiotics of the Cinema, 69

(8) Metz, Semiotics of the Cinema, 70

(9) Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, trans. Wade Baskin (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1915) 114

(10) Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, 115

(11) Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, 115

(12) Barthes, Mythologies, 26

(13) Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, 14

(14) Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, 15

(15) Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, 120

(16) Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, 66

(17) Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, 67

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Note

Hey, Hunxi, any chance of getting that meta about Crouching Tiger recontextualizing qinggong because I'm not sure what the difference is between "supernatural spectacle" and "oblique superhuman ability." Certainly Crouching Tiger was the first time I saw that kind of martial arts on film but I've assumed that's cause I'm a dumb white American. (Realize this is wildly off-topic, I'm just interested in it.)

(a follow-up to... this post, I think? not me elaborating on this ten months later)

so this ask sent me digging back through my old files, since that line referenced a paper I wrote in my first year of college, bright-eyed, bushy-tailed, and completely ignorant of film genre theory and the liberation that comes when you realize that all genres are simply constructs of society and marketing and have only as much power as you give them

but! before 我看开了, I wrote an embarrassingly long paper trying to split hairs between depictions of the superhuman, the supernatural, and the flat-out magical in East Asian martial arts film, which functionally meant that I was looking at portrayals of 轻功 qinggong (lit. "the art of lightness" aka wire fu) across different eras of wuxia cinema. was this essay fun to write? you bet. was it a good essay? well.

anyway, threw some relevant selections under the readmore

(obligatory disclaimer that I barely know what I'm talking about and I knew even less in my first year of college, everyone should just go read Stephen Teo's Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition if you want a thorough introduction to the genre and its history)

So it might help to know that I had set down the following definitions for the purposes of splitting hairs:

superhuman: "tied specifically to the abilities of each character, especially the physically impossible actions employed in fight sequences"

supernatural: "elements of the filmic world that break the laws of nature, science, or reality, and is often associated with a degree of spirituality or otherworldliness"

magical: "any set of supernatural abilities involving its own skills and technique that can stand independently from regular hand-to-hand combat, though the two may be intimately related"

(I think it's worthwhile to mention that the wuxia genre's relationship with quote-unquote "realism" is a fascinating and dynamic balance; as the genre goes through phases and new waves, this relationship can be emphasized or eschewed entirely, often depending on directorial style and/or market popularity. there's also a longer conversation to be had about "realism" in the traditions of Chinese art and theater/opera, but that's absolutely out of my area of specialty)

are these good definitions? not particularly. I don't pretend this was a good essay, but it might help contextualize some of the statements I make below

here's some analysis, borrowed primarily from David Bordwell, of King Hu's editing style in his wuxia films and how that factors into the "realism" of the martial arts depicted:

The boundaries of reality have always been porous in the genre of martial arts film; cinematically translated, this tendency manifests in what David Bordwell describes as the aesthetic of “The Glimpse” in King Hu’s filmography. Through a strategic form of editing, the fighting action in Come Drink With Me (1966) and A Touch of Zen (1971) lurks on the edge of visibility, creating the illusion that the characters literally move too quickly for the camera to catch up; or, as Bordwell explains in his comprehensive dissection of Hu’s filmic technique, Hu “frequently stages, shoots, and cuts his action so that it becomes too quick, too distant, or too sidelong for [the audience] to register fully” (Bordwell 118).

and specifically, King Hu's rendition of qinggong:

...Hu was far more concerned with “dignify[ing] and beautify[ing]” the “feats” of his warriors “without tipping them into implausibility and sheer fantasy” (118). This devotion to a semblance of reality appears in Hu’s portrayal of qinggong – or rather, his lack of portrayal. An established component of Chinese wuxia literature and film, qinggong can be literally translated as ‘the skill of lightness,’ or, as Stephen Teo puts it, “the skill of applying weightlessness” (Teo 32). Characters proficient in qinggong can soar across rooftops or leap twice their height from a standstill, land safely from great heights or save love interests from death-by-falling. In its most conservative depictions, qinggong is a superhuman skill that stands at the limits of believability and hypercompetence; in its most liberal renditions, qinggong becomes a stark indicator of the supernatural in a film. In Come Drink With Me, Hu exercises restraint in his portrayal of qinggong by illustrating it through a series of negatives – where Drunken Cat (Yueh Hua) was one moment, he no longer is by the next time the camera/Golden Swallow (Cheng Pei-pei) looks at him. Instead, Drunken Cat has inexplicably appeared across the river, leaving the viewer to presume that Drunken Cat has utilized his ability of qinggong to move in the time the camera looked away. In discreetly portraying qinggong in offscreen action, Hu minimizes the supernatural...

In the iconic bamboo fight scene from A Touch of Zen, Hu utilizes swift cutting and editing (his average shot lasted around 4.5 seconds) to depict qinggong – again, at the edge of visibility (Bordwell 127). In a fight-ending series of acrobatics, Yang Hui-ching (Hsu Feng) leaps off bamboo trunks to dive down from the treetops. Rather than openly utilizing wire-work or slow motion, Hu gives his characters more airtime by “adding more fleeting actions – a foot striking a tree trunk, the flash of a body twisting and spinning to keep aloft a split-second longer,” but never pulling back for a long shot that would expose the supernatural/superhuman ability for his audience to see (Bordwell 131). The addition of these “fleeting actions” create a semblance of physics in Hu’s world; Yang’s slippered foot pushing off of one bamboo trunk in one shot is followed closely by her leaping towards another, suggesting causality in a series of illusions created by Hu’s masterful use of constructive editing (Bordwell 131). Through his cinematic ellipsis, Hu hints at the superhuman capabilities of his characters but refrains from displaying it directly on film.

so, that's King Hu and wuxia in the 70's. it's not that there was no wuxia in the 80's and 90's (that is, after all, the heyday of Tsui Hark and Chu Yuan and somehow, Wong Kar-wai getting in there a bit with 《东邪西毒》 Ashes of Time), but I was a sleep-deprived undergrad and jumped straight to the 21st century:

In stark contrast to the frenetic, fragmented qinggong of King Hu, Ang Lee and Zhang Yimou present an ethereally graceful and beautifully serene version of weightlessness [...] In Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), Jen Yu (Zhang Ziyi) often employs qinggong to leap into the air from a standstill to escape, chase, or attack. Later, in Lee’s homage to the bamboo forest-battle in King Hu’s A Touch of Zen, Jen Yu and Li Mu Bai (Chow Yun-fat) clash intermittently on the treetops of bamboo, which sways seductively in an oncoming storm. As the two soar past each other, Lee’s skillful manipulation of wire-work shown lovingly in his long shots creates the sense that the warriors are not creatures of the earth, but supernatural beings of the air who must touch down on the bamboo to keep from drifting away into the sky. Likewise, in Zhang Yimou’s 2002 film Hero, each assassin can soar backwards out of range of weapons, break into flight while charging to meet an enemy, or change direction in mid-air. [...] The result: a mythical, timeless aura that emphasizes the fantastic and romanticized aspects of an imaginary ancient China.

(digging through my old files again, and this analysis owes pretty much its entirety to Kin-Yan Szeto's chapter "Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon: gender, ethnicity, and transnationalism" in The Martial Arts Cinema of the Chinese Diaspora, which is really a very good piece that puts Crouching Tiger in its rightful place)

it’s worth noting that depictions of qinggong/flight aren't necessarily constrained by the development of cinematic production and special effects--for example, Tsui Hark in Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983) was freely and liberally using wirework shown on-screen as well--but I’m fairly confident that a direct line can be drawn from Crouching Tiger and Hero’s depictions of qinggong as graceful flight to the liberal use of wirework in wuxia/xianxia film and TV today. As Szeto writes:

"Unlike previous wireworks used for the sake of spectacle, Lee employs the long shot to expose the supernatural power of the flight so as to enhance and express the emotion of the characters. Both technology and capital allowed Lee to break physical laws in imagining the flying sequence. He took a literal approach to making these fantastic legends into live-action visual images with the help of modern technology, transforming the dreamy imagery of soaring warriors from wuxia novels onto the screen...Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon’s use of long shot to record bodily movements purposely tries to differentiate itself from the fragmented flight sequences of Hong Kong martial arts films and the special effects that enhanced Spider-Man. Lee’s reworking of the wuxia and martial arts choreography and filming techniques thus becomes significant in a film production targeted at transnational film markets." (58)

Szeto then goes on to analyze the use of qinggong as spectacle and its function in a deliberate (self-)Orientalization and mythmaking on Ang Lee's part, but that is much too deep of a dive for this tumblr post

revisiting this essay several years down the line is fascinating because what Teo previously presented as the genre split between wuxia vs. shenguai (神怪, literally 'gods and monsters,' a more fantastic genre than wuxia) doesn't quite map onto my current understanding/usages of wuxia / 仙侠 xianxia / 玄幻 xuanhuan as genre designations. I'd love to hear Teo's take on modern wuxia dramas, but I feel like he wouldn't be caught dead watching them, and anyways, genre/genre definition isn't all that important at the end of the day, just a fun theoretical framework to hang some tumblr meta on sdlkfjsdlkjf

135 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Indie Game Spotlight: Plaything

This week’s Indie Game Spotlight is a reminder to lead with kindness. Plaything is a joyful and intimate game about your relationship to a small being crafted by your fingertips. In a series of personal and touching vignettes, you learn to live alongside each other. With a loving blend of hand-made animation and unfolding generative art, Plaything is a moving experience you can hold in your hands and close to your heart.

We spoke with Niall Tessier-Lavigne and Will Anderson, who are both from the Highlands of Scotland. Niall has a background in games and animation, Will in animation and film. They’re co-designers on the game, which involves things like figuring out the visual direction, narrative design, and gameplay decisions. Read on!

What was the main inspiration for the game?

A lot of the ideas behind Plaything came from our desire to make something with kindness at its core. We were both thinking about our own relationships to technology and wanted to make something that’s very careful with its dynamics of dependency.

Niall: I was definitely inspired by seeing Will’s short film, Have Heart, which is what lead me to approach him in the first place. I find the ideas in it about work, love, and digital media really affecting.

Aside from that, I’d been thinking a lot about gardening games, kinda prompted by Max Kreminski’s gardening games zine; games that can have an element of nurture and care, without feeling like heavy systems. I’d also had other people’s words about empathy and games rolling around my head for a while—writing by Lana Polansky, Emilie Reed, thecatamites, Paolo Pedercini, to name a few.

Will: When I was younger, I was pretty obsessed with Tamagotchis. I had LOTS of them. The idea of nurturing something that isn’t real always fascinated me. On the surface, it feels trivial, but on closer inspection, being affected by something artistic in our lives is pretty crucial for our wellbeing. So that, along with very human character animation, is a source of inspiration.

What was it like, coming together from game development and film making backgrounds?

Early on, we did a lot of talking before figuring out what any aspects of the game would look like, or what the gameplay would consist of. We tend to approach things in quite a filmic way—jotting down possible moments and feelings, script-writing, doing rough animatics, sort of translating this into something less fixed, and more interactive. We love working with rough-cut trailers and animations of possible playthroughs set to music, as a way of thinking through the arc and tone of Plaything.

What are some ways you can create and customize the small creature?

You pull softly fizzing shapes into the center of space, loosely assembling the creature’s form. There’s a degree of control, but a big part of the design is how loose and gestural this action feels. You don’t have too much control over the final assembled form of your Plaything in the same way you don’t get to control how it behaves or feels towards you. Part of the experience of playing is mapping out how you act together, defining those hazy spaces at the edges of your relationship.

What other features does the game include?

Niall: All the features you know and love from your friends and family.

Will: Eyes, ears, mouths, arms & legs.

What do you hope players will take away from the game?

If we can give you something to waste your time with, in a way that feels genuinely meaningful, we’d be very happy. We hope to stir something up in the cold embers of our collective hearts.

Want to learn more about Plaything? Then sign up to the mailing list to very occasionally receive behind-the-scenes bits and pieces, along with news about the game’s release.

924 notes

·

View notes

Text

As the Spirit Moves You: How Studio Ghibli Films Leave Room for A Range of Religious Interpretations

Today’s guest post is by Kaitlyn Ugoretz, a PhD student in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultural Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara whose research focuses on the globalization of Shinto through popular and digital media and the growth of online Shinto communities.

Since childhood, my life has been suffused with an appreciation for both anime and religion. Saturday mornings were dedicated to the weekly ritual of watching cartoons with my father (Pokemon, Yu-Gi-Oh!, Sailor Moon, Mobile Suit Gundam Wing—if it was on Toonami or WB Kids, we watched it!), and Sunday mornings were spent listening to him preach the gospel as the minister of our small Presbyterian church.

As a child, I never really thought about how anime and religion might intersect, but all that changed after I watched Miyazaki Hayao’s Spirited Away. Something about the heroines, spirits, and grand narratives about relationships between humans and the environment spoke to me and inspired a fascination that continues to shape my adult life. And thanks to social media and blogs like Beneath the Tangles, I know that I’m far from alone in feeling that there is something deeper—something that goes beyond what we might think of as “mere” entertainment—to be found in many anime. Today, I study the variety of religious/spiritual responses to anime as a scholar of Japanese religion, popular culture, and digital media.

Ghibli—Global Giant

Shinkai Makoto’s 2017 blockbuster animated film Your Name has given Spirited Away a run for its money in the box office, but Miyazaki Hayao’s 2001 masterpiece reclaimed its status this past June as the highest grossing anime film in the world after its long-awaited release in China. Studio Ghibli has produced an impressive 10 out of the world’s top 50 highest grossing animated films, including beloved favorites My Neighbor Totoro, Princess Mononoke, and Ponyo.

Box office earnings are not necessarily an indicator of the spiritual depth of Studio Ghibli’s films, but they do demonstrate their enduring global appeal. Scholars of Japanese religion and popular culture, most notably Jolyon Baraka Thomas and Katharine Buljan and Carole M. Cusack, have shown that Miyazaki Hayao and Isao Takahata’s anime films resonate with audiences from a wide range of religious and cultural backgrounds and even inspire religious responses.

What is it about Ghibli films that continues to capture the hearts of people from all walks of life and allows for such a diversity of religious interpretations? Considering how Miyazaki represents his filmic intentions, in addition to how scholars and different fan audiences have interpreted the meaning of Studio Ghibli films, I find that it is the mixture of familiar and foreign religious elements that inspire us to reexamine our own beliefs and seek out those messages that resonate with us.

Miyazaki’s Mixed Messages

What Miyazaki intended to communicate to his audience through his films? After all, he is well-known for addressing moral and social concerns, including adolescence, good and evil, humanity’s relationship with nature and technology, modern anxieties, and nostalgia for the past. Given his tendency to populate his fictional worlds with spirits or gods (typically referred to as kami in Japanese) and other supernatural creatures who are closely related with nature, like the river spirit in Spirited Away and the Forest Spirit in Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki is often asked whether his films are meant to foster Shinto beliefs.

Cleansed river spirit

Shishigami-sama, the Great Forest Spirit

Shinto is a difficult tradition to define, as it has meant different things to different people throughout history. Some classify Shinto as a religion with clear beliefs and practices, while others characterize it as an essential part of everyday life in Japan which can only be understood experientially. In any case, most can agree that—at its core—Shinto is a ritual tradition which centers on the worship of kami, divine entities that inhabit extra-ordinary natural phenomena and man-made objects and whose favor grants benefits to one’s life in this world.

While this definition may seem to suit Miyazaki’s films well, the creator himself explicitly rejects Shinto as the source of his inspiration. Miyazaki grew up in the midst of WWII and his understanding of Shinto is informed by the legacy of what scholars call “State Shinto,” the modern Japanese government’s takeover of Shinto shrine affairs in order to promote imperialist and nationalistic ideologies. The filmmaker has given ambiguous answers to the question of whether his films are influenced by religion. In one interview, Miyazaki elaborated:

Dogma inevitably will find corruption, and I’ve certainly never made religion a basis for my films. My own religion, if you can call it that, has no practice, no Bible, no saints, only a desire to keep certain places and my own self as pure and holy as possible. That kind of spirituality is very important to me. Obviously it’s an essential value that cannot help but manifest in my films.

Through his consistently vague characterization of his personal brand of spirituality, Miyazaki—like any masterful storyteller—leaves room for his audience to draw upon the rich imagery, relatable characters, and familiar themes to create their own meaningful interpretations.

Scholarly Interpretations

Scholars of religion and media have interpreted Miyazaki’s works from a number of theological perspectives. Some argue that the kami characters and environmental ethics which Miyazaki employs are clearly drawn from Shinto, despite his claims to the contrary. Others have offered Christian interpretations of Miyazaki’s films. For example, Prince Ashitaka (Princess Mononoke) and Princess Nausicaä (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind) have been analyzed as messianic mediators between the profane and sinful realm of humanity and the sacred realm of Nature/Creation, as well as messengers of the gospel, promoting love and nonviolence.

Ashitaka goes into exile to restore harmony

Nausicaä is healed by the Ohm

Fan Interpretations

Scholars aren’t the only ones interested in the spiritual underpinnings of Ghibli films—fans around the world gather on- and offline to discuss their personal interpretations. These conversations are more than intellectual exercises; Thomas and Buljan and Cusack have shown that popular media like anime can inspire religious responses in audience members as well as entertain. That is, Ghibli films may influence viewers’ worldview and behavior, even if these viewers do not consider themselves to be religious. Thomas’s survey of Japanese fans shows that this influence may take many forms, such as a “belief in an immanent spiritual bond existing among all living things,” a pilgrimage to a special site like Yakushima forest (supposedly a source of inspiration for the sacred forest in Princess Mononoke), or a reenactment of the acorn-growing ritual portrayed in My Neighbor Totoro.

Erika Ogihara-Schuck examines how Miyazaki’s films have been translated into English and German in such a way as to secularize the spiritually-charged elements, referring to kami characters as “spirits” rather than “gods” and their powers as “magical” instead of “sacred” or “divine.” In some cases, this translation project has succeeded; some fans view Miyazaki’s films as ‘simply entertaining,’ while others read them as uncomfortably morally ambiguous, superstitious, or explicitly opposed to Christian theology. Still others in the Christian blogosphere—including contributors on sites such as Beneath the Tangles and Christ X Pop Culture—have found plenty of food for thought in Studio Ghibli films, prompting discussions of how anime narratives might productively challenge and affirm their core values as brothers and sisters in Christ.

Some audiences, as I have discovered in my own research, draw upon Studio Ghibli films as a source of Shinto spiritual instruction. In my study of the growth of predominantly non-Japanese online Shinto communities (OSCs) on social media, I find that anime plays an important role in the fostering of interest in Japanese religions, as well as participation in OSCs.

In interviews, surveys, and posts, several of the leading, active members of OSCs have noted that their early exposure to Ghibli films are what inspired their further study and adoption of Shinto. In community discussions, members share their interpretations of religious elements in anime. These conversations often focus on the relationship between humanity, kami, and nature and affirm the importance of moral character and gratitude. In similar fashion to other online religious communities, OSC members will comment on posts and keep the discussion going, negotiating interpretations, sharing links to blog posts and video clips which they find informative, and posing further questions.

In response to new members’ requests for more information about Shinto, each OSC has created its own list of recommended resources, which often include anime films and series in addition to books and blogs. As such, Studio Ghibli films like Spirited Away and Princess Mononoke have become, in effect, ‘required reading’ for OSC members. In this way, Ghibli films function as an important introduction to Japanese spirituality—particularly Shinto—for international audiences and a resource for the construction of personal and community beliefs.

Language Games

How can Studio Ghibli films spark so many different religious responses and interpretations—Christian, Shinto, and otherwise? The answer lies with two key concepts: Jolyon Baraka Thomas’s theory of “playful religion” and Leonard Primiano’s theory of “vernacular religion.”

Thomas argues that the distinction we make between religion and entertainment is artificial; entertainers can playfully use religious symbols to create an engaging story, and viewers can derive spiritual meaning from popular media, regardless of whether the creator intended for them to do so.

“Vernacular religion” refers to religion as it is lived—not what religious authorities say religion ‘should be,’ but how religious concepts are translated into a particular culture and actually practiced by people.

One way anime creators like Miyazaki manage to both entertain and inspire their audiences is to ‘play’ with the ‘languages’ of religion. These language games are a lot like playing Mad Libs. The storyteller chooses from among a variety of popular religious images and themes from different traditions—our collective religious vocabulary bank—and removes them from their original context. These religious elements are then recombined within a familiar narrative framework to create new images and stories that are compelling because they are both familiar and foreign to us. It is left up to each of us as audience members to make sense of these disassociated religious elements by translating them back into our own vernacular of faith.

Understanding this process of translation we all participate in as Studio Ghibli fans is important for two reasons. First, it reminds us that the meaning or significance of an anime is not defined by any one person’s vision, even that of its creator. No one has the ‘right’ answer. Our personal interpretations and those of others are just as meaningful, because they are grounded in our beliefs and thus have the power to affect the way we look at the world and live our lives. Second, the fact that the same images and themes can resonate with people of different faiths and backgrounds speaks to values we have in common, as well as a common desire to be spiritually engaged, as well as entertained, by the media we consume. Ultimately, the genius of Studio Ghibli films lies in their rich assemblage of religious symbols and grand narratives, which audience members are—if they are so inclined—free to interpret in a way that affirms their beliefs and feeds their soul.

Kaitlyn Ugoretz is a PK (Pastor’s Kid), anime fan, and PhD student in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultural Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research focuses on the globalization of Shinto through popular and digital media and the growth of online Shinto communities. Kaitlyn runs Digital Shinto, a site where anyone can learn about and participate in her ethnographic study of Shinto’s development outside of Japan.

—

Recommended Reading:

Buljan, Katherine and Carole M. Cusack. Anime, Religion, and Spirituality: Profane and Sacred Worlds in Contemporary Japan. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing Ltd., 2015.

Ogihara-Schuck, Erika. Miyazaki’s Animism Abroad: The Reception of Japanese Religious Themes in German and American Audiences. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2014.

Park, Jin Kyu. “‘Creating My Own Cultural and Spiritual Bubble’: Case of Cultural Consumption By Spiritual Seeker Anime Fans.” Culture and Religion 6.3 (2005): 393-413.

Thomas, Jolyon Baraka. Drawing on Tradition: Manga, Anime, and Religion in Contemporary Japan. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press, 2012.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reviews 356: Fulvio Maras, Alfredo Posillipo, Luca Proietti

In 1991, during Italy’s yearly Ferragosto holiday, the city of Rome was utterly empty, so much so that “you could die and not be noticed in the deserted streets.” Thus a trio of sympathetic and exploratory musicians named Fulvio Maras, Alfredo Posillipo, and Luca Proietti, who for their own varied reasons stayed behind, had full reign of a professional studio, which allowed them total freedom to create the music of their wildest fantasies. At this time, Maras was already a world traveller and veteran player, with credits extending at least back to the 70s and encompassing jazz, pop, theater, ballet, TV, film, and much more besides. Posillipo and Proietti, however, were newer to the scene…the former a horn player and producer who had worked with artists such as Jim Porto and Eddy Palermo and was in the group Gli Io Vorrei La Pelle Nera, the latter a guitarist, synthesist, and sound designer who, among many other achievements, eventually became the chief professor of music technology and sound engineering at the Saint Louis College of Music. And during that fateful summer holiday in Rome, with a studio overfilled with world instruments and futuristic gadgets, the trio combined their diverse backgrounds and myriad interests into a compelling and impossibly eclectic adventure called Sfumature, one which has just been reissued and lovingly expanded by Archeo Recordings, with the label including a remix, an unreleased track, translated liner notes, and remastered sonics.

Across the album, organic and machine rhythms blur together through fourth world rainforest rituals and broken beat funk and fusion groovers as colorful assortments of synthesizers and samplers merge together, equally reveling in textures of orchestral romance, filmic mystery, futuristic kosmische, and crystalline new age. Posillipo’s trumpet weaves solo songs of spiritual jazz over muted and equatorial hypno-jams while sometimes darting and dashing between an array of virtual woodwinds…all while synthesized basslines walk like a bebop stand up, slap like fusion funk, or squelch playfully towards acid. Angel voices presumably sourced from Maras’ ballet and theater performance archives sing through the mix, sometimes droning together with dark industrial synthesizer ceremonials while at other times alighting on operatic flights of wordless fantasy, which wrap the heart around with glowing threads of melancholic beauty as idiophones both real and imagined sparkle in the light of a setting sun. And the entire experience is awash in celebratory vibes born of creative freedom and imaginative spontaneity, with some the trio’s happy studio accidents even being detailed in the included liner notes, as Posillipo recalls his inspired choice to switch from trombone to trumpet and Proietti details the potential catastrophe of a forgotten a click track, only to have Maras perfectly nail the timing (a fact which is hilariously attributed to his lack of alcohol for that day).

Fulvia Maras, Alfredo Posillipo, Luca Proietti - Sfumature (Archeo Recordings, 2020)

In “Gomma,” Maras’ marimba splashes through glowing tide pools while hand drums beat gently. Squelching basslines underly descending island melodies that see the marimbas merging with sampled steel pans…the whole thing radiating an irrestible Caribbean warmth. From here, the track ambles back and forth between instrumental choruses where idiophonic clouds alight on equatorial themes of sunshine joy, and more minimal stretches where Maras’ marimba wanders solo through worlds of seaside jazz tropicalia while hand percussions bop around acidic basslines. And at some point, shakers enter to guide the lackadaisical dance of island life fantasy. Splashing cymbals and cascades of metal begin “Panica iniziale” and timpanis roll like thunder beneath violent shaker motions. Dissonant swells of horror film drone surround militant drum rolls before everything recedes into a storm of cymbals, snake tails, and echo clicks. Cyborg choirs sing from the void and execute magisterial chord changes evoking Klaus Schulze’s Irrlicht…all while splattered symphonic percussion moves maniacally underneath. Choral layers recede to reveal pounding bass synthesizers that flub like rubber bands while martial drums and hissing shakers work the body. Then, towards the end, the layers of sci-fi dissonance return, as mysterious chord changes evoke terrifying landscapes of mist and shadow over a physical and ever-shifting panorama of bass sequencing and timpani terrorism. Then comes “Deserto” with metalloids bending and synthesizers blowing spectral clouds of darkness. Mysterious keyboard solos evoke slow motion explorations of mythical desert landscapes and clattering percussions surround tick-tock bass sequencing while melting wavefronts of sliding subsonic weirdness subsume the spirit. The mix is periodically disrupted by whip-crack bursts of sinister bass and machines moan in desperation as Latin percussion accents are subverted into an industrial drone jam…all until the rhythms disperse entirely, leaving resonant bass vibrations to coalesce with glacial themes of cosmic melancholia…as if dark and shadowy colorations are pooling together into an unsettled miasma.

For much of the remix of “Sotto la cascata,” you’d be forgiven for thinking it was the original version, for though this is a rather radical reworking, it doesn’t reveal its true magic until well into the song. Indeed, we start with the original’s throbbing contrabass motions and echo-soaked jazz filigree, with brushed snares working against sizzling cymbals. Berlin school sequences wash through aquatic fx hazes and a glorious voice sings wordless songs of mermaid majesty…the effect not unlike the work of María Villa or MJ Lallo. But whereas the original version ends on a stoned outro of contrabass and trapkit ghost notes, the remix brilliantly drops a boom bap breakbeat while arpeggiated synthesizers percolate through kosmische energy swells. At some point the haunting voice cuts away, with kick drums locking into a four-four heartbeat while ascending prog electronics evoke Pink Floyd. But we eventually drop back into the low slung drum groove, where the vocals are now a shadow of themselves as they swim around g-funk synth accents, future jazz basslines, and orchestral layers of space foam. Then in “Alla Casba.” zany pianos dance around forest flutes until a fat pounding basslines drops amidst smatters of equatorial hand percussion. After riding a tropical sunshine groove out, snaker chamer synth melodies start raining over the mix…their tones sitting somewhere between psaltery and crystal. Hand drums roll and hi-hats and tambourines lead a sensual island sway as fourth world melodies and cinematic ivories join together with exotic flute fantasias, resulting in a strain of magical Italo-balearica that encompasses vibes of esoteric darkness and romantic adventure. The crystallized string arps of “Dura Lex” follow, which execute an elven dance over a tribal ceremonial of wooden bass synthesis. Melodies of fairy fantasy intermingle with airs of classical grandiosity and solar swells of subsonic warmth float the soul while shakers sketch out airy rainforest rhythms. And as gemstone sequences and spiritual woodwind leads play off one another, their threads of paradise magic weave tightly around a joyous ethno-ambient percussion drift.

In “Trombe di Alfredo,” ticking tones of crystal overlay a manic string synth and percussion ritual as we sweep straight away towards a mysterious oasis of Arabian desert magic. Posillipo’s trumps is carried on a warming breeze as Maras and Proietti lock into a shamanic tribal trance, wherein hand drums from various cultures beat wildly, fourth world synthesizers drift towards the clouds, and tapped crystals hypnotize the mind. Bleary-eyed themes of cinematic romance swim deep in the background ether as drums continue their manic dance and occasionally, the string synthesizers rise to the surface to replace the exploratory trumpet solos with flowing songs of symphonic grandiosity and sorrowful desert mystery. “Amori,” which was inspired by Maras’ breakup at the time, sees harmonious waves of synthesizer billowing in…like a sea of neon pink crashing against a white sand shore. Cymbals sparkle and hand drums pound wildly alongside rimshot snaps while Posillipo paints cinematic trumpet leads over fusion-tinged fretless bass serenades. Enigmatic key changes plunge the mind into underwater landscapes and abandoned mermaid kingdoms, with the melding of exotic ambient and exploratory jazz bass reminding me of Motohiko Hamase. Swells of seaside ethereality wrap around the body as the basslines continue dancing alongside tapped cymbals and crazed percussions and all the while, Posillipo weaves in and out with warming wavefronts of bebop trumpet. A synthesized orchestra sways strangely in “Aura due”…as if swimming through an alien ocean while warming brass melodies swirl overhead. Sampled french horns play themes for a mist-shrouded dawn and oboes, bassoons, and clarinets weave together a tapestry of Italian 70s cinema romance, with the vibe like relaxing in a field of flowers and watching clouds drift across the great blue sky. Sprightly flute harmonies enter at some point as the virtual string orchestrations continue their drunken dream dance and as the reed instruments and aerophones intertwine, a summer shower of marimba begins falling…gentle at first…but then coming down like an overwhelming storm of hyperspeed chaos.

Violins saw through glowing reverberations in “Ballo accorto,” with the hypnagogic atmospheres interspersed by cymbal taps and hand drums. The track continues swelling with solar strength and emotional warmth as grandiose horn and flute themes flow down from the heavens, resulting in a dreamspace dance of tapped metals, rainforest drumming, and orchestral wonderment. At some point the strings recede, leaving space for tambourines jangles and tribal drum percolations, and once they return, the vibe is somehow even more epic than before, with Posillipo’s trumpet melding with currents of cloudland magic to lift the spirit towards a paradise sky. The original press of Sfumature ends with “Alfredo Fantasy” and its electronic and world percussion locking together for an exotica fusion jam, with chord stabs sitting somewhere between fusion and reggae floating overhead as the rhythms eventually settle into a stuttering and off-kilter funk break, which almost falls over itself each time it loops around. Snares and cymbals splash alongside the dubby melodics while distorto-basslines growl just out focus…their effect felt more than heard. And towards the end, the reggae riffs recede, leaving drums to work through an extended jam’n’slam, with touches of library funk, electro, and hip-hop merging while the basslines erupt towards jazz fusion slapping. Final track “Vertigini (Ambient Remix)” is exclusive to this Archeo Recordings reissue, and sees windchimes fluttering on an asymmetrical breeze and crystals conversing in cavernous spaces as a voice grows from pale mist into an all-consuming drone. Bubble clouds of inky synthesis billow up from seafloor vents, computronic diamond clusters rain down from an unsettled sky, and plucked string harmonics refract rainbow light through the rippling liquid atmospheres…as if a harp is being played in the middle of some celestial ocean. And later, mystical voices transmute towards angel opera flamboyance, ambient house chords incandesce in strange colorations, and metallic droplets fall into pools of liquified glass while pads modulate through resonating bodies of sonic shimmer as they move forwards and backwards in time.

(images from my personal copy)

#fulvio maras#alfredo posillipo#luca proietti#sfumature#archeo recordings#manu•archeo#reissue#1991#1992#2020#rome#ferragosto#holiday#balearic#italian#leftfield#experimental#exploratory#world music#jazz#new age#world jazz#ethnological#tribal#ambient#cosmic#kosmische#operatic#mystical#playful

1 note

·

View note

Text

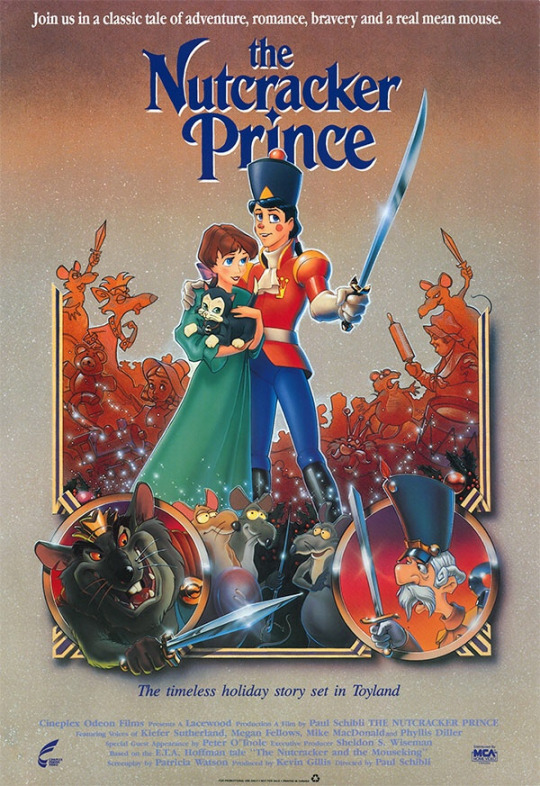

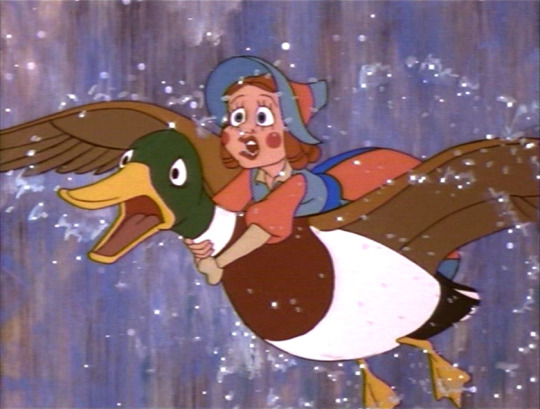

Merry Christmas everyone! To conclude this month of merrymaking we’re looking at an animated Christmas cult classic that I have a bit of a soft spot for. But perhaps it’s best to start at the beginning:

ETA Hoffman’s “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” is one of my favorite fantasy stories, though chances are you’re more familiar with the famous ballet by Tchaikovsky that it inspired. The music is gorgeous and instantly recognizable, but few know the actual story of The Nutcracker beyond what your average community production rolls out every December. Much of the plot plays out like a variation of Beauty and the Beast with a protagonist akin to The Wizard of Oz’s Dorothy and story elements that wouldn’t feel out of place in a Grimms’ fairytale. Sadly, most of those details were lost in the translation from book to light holiday entertainment. Not that I’m complaining, I love the ballet, but there’s so much more to its origins that people aren’t usually interested in delving into.

I say all this because today’s movie, The Nutcracker Prince, is one of the very few filmic adaptations that pays faithful tribute to both its source material and its theatrical counterpart. In spite of – or perhaps because of – the popularity of the ballet, there’s been only a handful of film versions of Hoffman’s The Nutcracker (or at least a handful compared to something like A Christmas Carol). How good you find each of them to be depends upon your taste and the production value. I’ve found remarkably little about the making of this particular adaption, but that probably has to do with the fact that it was barely a blip on the box office radar. Released through Warner Brothers (which itself would issue another Nutcracker movie starring Maculay Culkin six years later), this was the only full-length animated feature created by Canada’s Lacewood Productions. A shame, really, because looking at The Nutcracker Prince you can see the studio’s potential. But thanks to the home video circuit, the movie has found a new life as a nostalgic Christmas classic for 90’s kids like myself. Let’s unwrap the reasons why, shall we?

If there’s one thing I appreciate about The Nutcracker Prince, it’s how it plays around with the music order to emphasize a scene’s mood rather than slavishly follow the original score. Instead of the recognizable jovial overture piping over the main titles, we have the Snowflake Waltz from the finale of Act 1, building an aura of mystery and magic to lure us into the story. A series of cross-hatched stills introduce us to our cast and characters, and I tell you, when you recognize these names you will not be able to look at this movie the same way. If I told someone that Anne of Green Gables, Jack Bauer, Lawrence of Arabia, Jimmy Neutron’s grandma and several prominent cast members from Canada’s Saturday morning fixture The Raccoons shared the screen together once, they’d think I was crazy, but as you’ll see it’s the honest to Zeus truth.

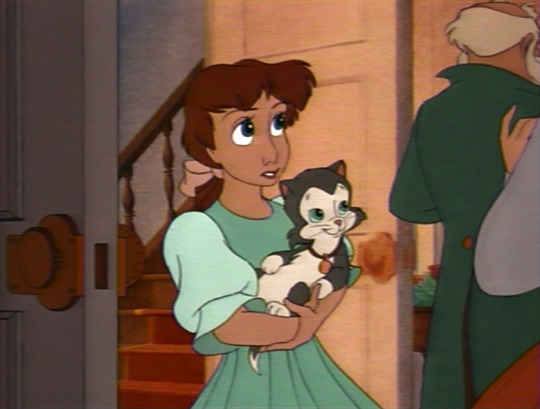

Our story begins proper with Clara Stahlbaum (Meagan Follows) and her younger brother Fritz delivering last-minute gifts to their neighbors on Christmas Eve. They race through the icy streets of Germany until they reach the shop of eccentric family friend Uncle Drosselmeier (Peter Boretski), a clockmaker and expert craftsman of mechanical toys. Drosselmeier greets the children and they invite him to come light up the Christmas tree with the family, but he enigmatically tells them he has to prepare for his nephew. This comes as news to Clara and Fritz, since they’ve known Drosselmeier for their whole lives and have never heard him mention a nephew before. Drosselmeier sends them on their way promising he’ll be at the Stahlbaum’s party that evening. Once they’re gone, he hints that there may be something magical in the air this Christmas…

“Blasted pixie dust everywhere! Once the holidays are done I’ve got to get the place fumigated!”

On their way home Clara and Fritz debate what Uncle Drosselmeier’s big annual present he makes for the family will be this time. Fritz, the little future warlord that he is, wishes for a working fort with a mechanical army, while Clara dreams of an enchanted garden where swans in golden necklaces glide across the water. This conversation is a little holdover from the Hoffman story that I like. One of the most difficult challenges every writer faces is writing natural sounding dialogue for children; while Hoffman’s dialogue is a bit stilted by the conventions of the era, the meaning still comes through. Fritz laughs at Clara’s fantasy but because he finds the idea of swans wearing jewelry more ludicrous than a magic garden, which is how an ebullient boy like him would think.

Back at the Stahlbaums, preparations for the Christmas party are underway. The parents give their children their presents: older sister Louise (who’s often excised from other adaptations) receives a pretty new dress, Fritz a hobby horse and toy soldier gear, and Clara a pair of ballet slippers and a new doll she christens Marie. I have to wonder if this is some kind weird in-joke since in the story, the main character is called Marie and the doll she receives is the one who’s named Clara. What happened during the process of making this movie that resulted in their names being switched? Clara is thrilled since these slippers bring her one step closer to her dreams of joining the royal ballet, but feels a touch bemused when she overhears her mother getting choked up at the notion that this may be Clara’s last doll.

The party arrives, including Louise’s boyfriend Eric. Clara and Fritz tease the lovebirds (though to be frank, anyone who wears a powdered wig twelve years out of fashion to something that isn’t a costume party deserves to be ridiculed) but something about their shared intimacy stirs something within Clara. This on top of the adult party guests commenting on how fast she is growing marks her entrance into that state of melancholy and confusion that comes from standing between childhood and adulthood and not knowing where you belong. Clara’s age is never mentioned though I suspect she’s roughly twelve or thirteen, right on the cusp of adolescence and about the time where that mindset begins to sink in. She still plays with dolls and treats them like they were alive, but imagines a future as an adult. There’s a growing sadness over the impending decision between the two that she subconsciously acknowledges through her playing with Marie. This theme isn’t present in the Hoffman story (Marie is a confirmed seven year old in the prime of juvenescence) but it’s been incorporated into the Maurice Sendak retelling a couple of years prior to The Nutcracker Prince and I like its inclusion here as well.

“I wonder if this is anything like what my pen pal Wendy went through with that Peter boy…nah, you’re overthinking it, Clara.”

But there’s no time for her to ponder the implications as a crack of thunder, gust of wind and explosion of fireworks marks the arrival of the final party guest – Drosselmeier. He comes bearing his greatest creation, an enchanting music box castle complete with marching soldiers, seven swans a-swimming, and figures dancing inside the ballroom. In another humorous scene from the original story, Clara and Fritz fawn over the castle while frustrating Drosselmeier with their requests to make the automated figures do more, leading him to go on a brief “kids today don’t appreciate shit” rant.

As the party guests waltz to the strains of more Tchaikovsky, Clara wanders by the tree and spies a present she hadn’t noticed before – a nutcracker in the shape of a soldier. He’s not the most handsome toy in the box, but there’s something charming about him that she is drawn to. Drosselmeier confesses that he’s just part of his gift for the family and demonstrates how he works. On seeing the Nutcracker, Fritz wrestles him out of Clara’s arms and insists he has a go. But because there are no nuts left, he tries one of his toy cannonballs and breaks its jaw. Drosselmeier cheers Clara up by telling a story of how the Nutcracker came to look as he does. And this is where things get…weird.

Now I don’t mind the inclusion of the story-within-a-story. I’m happy they go into how the Nutcracker was cursed unlike most other versions, and there’s some good gags thrown in that make me chuckle. It’s how they go about it that I take some issue with. First, look at the movie’s style looked so far.

The character designs are clearly inspired by Disney – big eyes, soft rounder faces, realistic body proportions for the main characters, only slightly exaggerated for the lesser ones. The backgrounds are warmly lit and richly detailed, like an early work by Thomas Kincade. Overall it feels like something out of a classic storybook.

Now here’s some screencaps from Drosselmeier’s story.

“All right, who changed the channel to Cartoon Network?”

The scene doesn’t even look like it’s from the same movie. It goes from feature film quality to a Saturday morning cartoon, and that’s not entirely coincidental. Lacewood Productions grew out of Hinton Animation Studios which primarily made, you guessed it, cartoons for tv. And Hinton Animation itself had its roots in Atkinson Film-Arts, the studio that produced The Raccoons, hence why some of the cast makes appearances. But because I couldn’t find anything on the making of The Nutcracker Prince, we’ll never know if they went this route because the budget ran out, or the animators didn’t feel comfortable drawing the entire movie in the Disney house style and worked out some kind of compromise, or they just wanted the reveal of the Nutcracker’s human form at the end to be an even bigger surprise. Given some time and creativity they might have been able to come up with something better. You could argue this is how Clara envisions the story playing out in her head, but I don’t think a child from the 1800’s would imagine a fairy tale in the style of Danny Antonucci. In fact, if you played music from Ed Edd and Eddy over this part it wouldn’t feel out of place. Everything is played up for nothing but laughs, not even the Nutcracker’s transformation into a lifeless object, which should be an emotional gut punch. And I’d be ok with all this if it was a short sequence, but it lasts fifteen minutes. That might not seem like long, but since this movie is only seventy-five minutes that means it takes up a good portion of its first half. Plus the cuts back and forth between the story to it being told reminds you of how jarring the whole sequence is compared to the rest of the film.

But on to the story itself. Drosselmeier’s tale takes place in a faraway kingdom belonging to a King who I can only describe Yosemite Sam in his golden years right down to the ornery western accent (it wasn’t until doing my research that I discovered he’s voiced by the Texan monster from the Beetlejuice cartoon which certainly explains it), an extreme doormat Queen, and their daughter, the “beautiful” but very spoiled and unfortunately named Princess Pirlipat. They have in their employ a world-famous clock maker and magician coincidentally also named Drosselmeier and his apprentice, his shy nephew Hans (Kiefer Sutherland).

“Patience, friends. The joke you’re all expecting is coming.”

The occasion on which this flashback takes place is the King’s birthday, and the Queen has put in an order for a cake made out of his favorite food, blue cheese (would that make it a blue cheesecake?) This has the unwanted side effect of drawing out every mouse in the palace. Led by the Mouse Queen (legendary comedienne Phyllis Diller) and her dimwitted son (Mike MacDonald), they pounce upon the cake just as the Queen is putting on the finishing touches.

With no time left to make a new cake, the Queen is forced to send it out to the King and his party guests. This disaster is almost salvaged by a sycophantic Emperor’s New Clothes-style response to the dessert, but Pirlipat ruins everything by whining how she refuses to eat that repulsive offal. The King promotes Drosselmeier to the post of Royal Exterminator and soon all the mice are caught – except the Mouse Queen and her son. She takes her revenge out on Pirlipat; using her dark magic she curses the princess with extreme ugliness, cementing it with a bite to the foot.

Oh please, that’s just Kellyanne Conway before her makeup.

Eager to blame somebody for Pirlipat’s state, the King is ready to execute Drosselmeier until the Queen suddenly intervenes and begs him to consider giving the clockmaker some time to reverse the curse. It was at this moment I realized the King and Queen here are like if the monarchs from Alice in Wonderland had their personalities switched. They even have the same body types as their Disney counterparts.

The King reluctantly acquiesces, but gives Drosselmeier and Hans no more than…well…did I already mention Kiefer Sutherland is in this movie?

youtube

“Your obligatory reference humor, all wrapped up in one neat package. Merry Christmas!”

So Hans and Drosselmeier study the princess to figure out a way to break the spell, not helped by Pirlipat’s constant ear-bleedingly grating crying. Her only comfort is Hans feeding her nuts he cracks for her himself. Inspired, Drosselmeier researches well into the night and discovers the cure for Pirlipat’s condition – the Krakatooth Nut, the hardest nut in the world. It can only be cracked open by a young man who’s never shaved or worn boots and they must take exactly seven steps to and from the person they’re feeding the nut to with their eyes shut and without stumbling, which even by fairy tale logic is some damn arbitrary rules.

The King invites noblemen from around the world to crack the Krakatooth with the promise of marrying Pirlipat and becoming heir to the kingdom if they succeed, though he has them and the rest of the court blindfolded so they won’t be scared off by her hideousness. Unfortunately each man who makes an attempt winds up with a mouth full of broken teeth. The Mouse Queen, confident in her evil plan, watches the misery play out with delight. Hans, however, decides to give it a try, and to Drosselmeier, the royal family, and the Mouse Queen and Prince’s surprise, he succeeds. Pirlipat is transformed back into her normal, terrible old self, however the court is too busy fawning over their restored icon to notice what happens next.

Enraged over being foiled, the Mouse Queen casts a curse on Hans to make him “the prince of the dolls”. Before he can take his final step backward, she bites his foot and he is transformed into a wide-smiling nutcracker. In his new form he accidentally knocks over a line of busts domino-style, the last of which the Mouse Queen is too late to escape from. I love it when villains are hit by instant karma. Alas, Pirlipat takes one look at Hans and refuses to marry a doll that’s not even half as ugly as she was moments ago.

Yep. Totally unmarriageable material.

On seeing his prospective son-in law for himself, the King accuses Drosselmeier of trying to trick his daughter into marrying one of his contraptions. He has the poor guy who’s shown nothing but years of loyalty and service to his outlandish demands banished forthwith while he and his wife and daughter celebrate their own selfish victory. I always hated how they never earned some kind of punishment for their behavior, but considering the boundary-shifting turmoil Europe endured before, during and after this tale was written, it’s more than likely these foolish monarchs will get what’s coming to them in the worst possible way down the line.

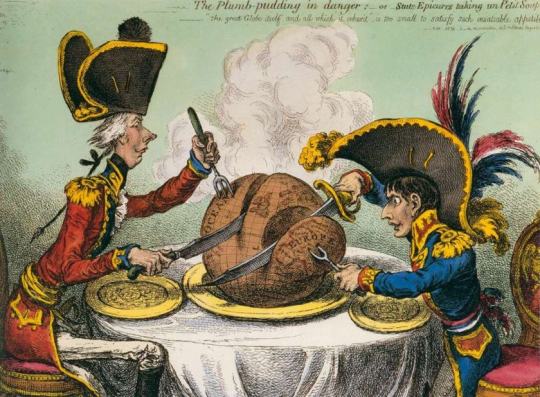

Enjoy your power while you can, assholes. Come the Napoleonic wars, you’re all royally screwed.

As for the Mouse Prince, he mourns his mother for all of ten seconds before realizing her death makes him the new Mouse King. He declares to Drosselmeier that he’ll have his revenge on the Nutcracker – not for killing mommie dearest but for smashing the end of his tail when the busts fell and making it go crooked.

With the story done, we abruptly return to the party and Clara expressing her disappointment in Hans’ unfair fate. Drosselmeier assures her that while Hans may be stuck as a Nutcracker, he’s still the rightful ruler of the magical kingdom of the dolls and the spell over him can be broken, but only if he defeats the Mouse King and wins the hand of a fair maiden. I love Clara’s reaction to this; she rolls her eyes and wonders why all fairy tales have the same solution.

Long after the party has ended and the Stahlbaums are fast asleep, a restless Clara sneaks downstairs with her kitty Pavlova to check on her Nutcracker. She introduces him to his new subjects, her toys – Marie, her old matronly doll Trudy, and Pantaloon, the ancient captain of Fritz’s toy soldiers. Taken by a music box’s melody, Clara shares a romantic song and dance with the Nutcracker to the tune of the Waltz of the Flowers, not unlike the one Louise and Eric had earlier.

youtube

And for those of you watching, yes, Clara is clearly rotoscoped when she’s dancing. I’m not against rotoscoping as long as animators don’t rely too heavily on it (COUGHBAKSHICOUGH), though the use of it here as well as in one other scene emphasizes how uneven the rest of the film’s animation is under scrutiny. I do wish there was a full version of this song somewhere though because it’s quite pretty.

The music comes to a sudden halt as Pavlova breaks an ornament. Clara quickly stashes the Nutcracker our of fear of being caught out of bed, but before she can return upstairs she’s startled by the famous ghostly image of Drosselmeier atop the grandfather clock in place of the decorative owl, his cloak billowing out like wings. He showers the entire parlor in pixie dust, and goofy-looking mice armed with forks and needles pop up from of every crevice. Pavlova scares them away from Clara until one arrives to scare him back – the Mouse King, looking far more intimidating than he did in the flashback.

One is an animation student’s design project, the other is Ratigan’s cousin. Would you believe they’re one and the same?

Drosselmeier also douses the toy cabinet with his magic and brings them all to life. The Nutcracker is woken up and, having no idea of what’s happened since the incident with Pirlipat, quickly has to come to grips with his new form and the fact that a sociopathic mouse has sworn a vendetta against him. And you thought the Hangover guys had it bad. Marie and Trudy plead him to take up his mantle as Prince of the Dolls and fight despite his inexperience. Fritz’s soldiers vow their loyalty and Pantaloon (voiced by Peter O’Freaking Toole) is made second-in-command. Though rather than do any actual fighting the old coot drones on and on in Shakespeare references.

“So we’re not watching Ratatouille Peter O’Toole so much as Man of La Mancha Peter O’Toole. Imagine my delight.”

Actually, like the Marie/Clara name switch before, I have to wonder if this odd characteristic of Pantaloon is another subtle in-joke or reference towards the original story. Hoffman was a big Shakespeare fan and often referenced him in his writings, including The Nutcracker. In the book when Fritz’s soldiers desert the battle, the Nutcracker cries out the famous line from Richard the Third, “My kingdom for a horse!” (paired down here to a simple “Come back!” when the toy horses run free). In a weird way, having Pantaloon riff on Shakespeare is a nod to Hoffman. On top of that, one of his first lines is “All for one and one for all”, which everyone remembers from Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers. Years after Hoffman’s Nutcracker was published, Dumas wrote his own version of the story which is the lighter, softer one that the ballet takes the most cues from. So whether or not this was intentional is up for debate, but if it was I give the writers all the credit in the world for honoring both authors of The Nutcracker in such an obscure and subtle way.