#david lewis

Photo

Bang & Olufsen, Beosystem, David Lewis

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

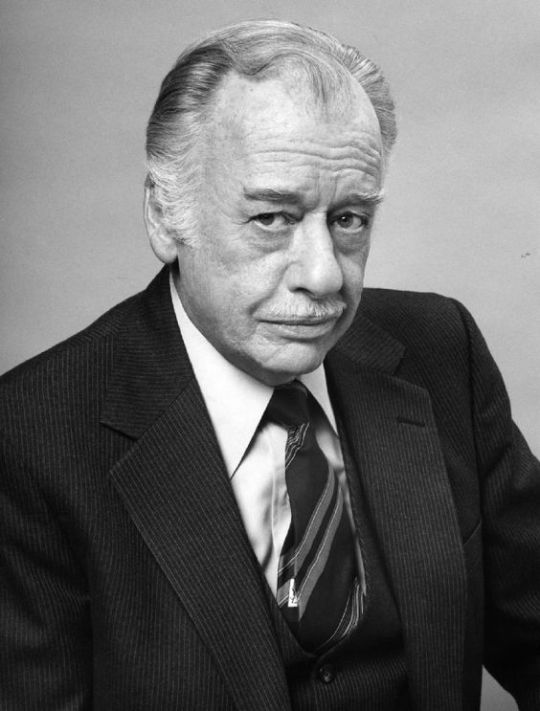

David Lewis (Edward Quartermaine).

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Il me semble que notre avenir est une table vide - les friandises que nous y servons ne dépendent que de nous.

© David Lewis

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

David Lewis (deceased)

Gender: Male

Sexuality: Gay

DOB: 14 December 1903

RIP: 13 March 1987

Ethnicity: White - American

Occupation: Producer

Note: Longtime romantic partner of director James Whale from 1930 to 1952

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I cannot reflect upon my Princeton adventures without remarking the very improper conduct of parents and guardians in furnishing the youth at colleges with such liberal supplies of money, as is generally done."

--David Lewis, the "Robinhood of Pennsylvania," claiming he spent several days in Princeton conning students out of money, July 12, 1820

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

there's bear in the fridge.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SG-13

#Stargate SG-1#sg1#stargate#SG-13#colonel dave dixon#cameron balinsky#jake bosworth#simon wells#i needed more dixon#heroes pt1#adam baldwin#david lewis#christopher pearce#julius chapple

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

David Lewis, the late philosopher-father of modal realism, gave a lecture in June 2001 (“How Many Lives Has Schrödinger’s Cat?”) that speculated about Many Worlds’ implications of an eternal life. At the time, Lewis was suffering from late-stage diabetes; he lectured not long after receiving a kidney transplant, and just a few months—so it turned out—before he died. He began his talk by explaining first superpositions, then both collapse and noncollapse interpretations of quantum mechanics; finally he imagined what it might be like to be Schrödinger’s cat. If collapse dynamics is true, each time an x-spin measurement is carried out—with an |up> measurement leading to poisoning and consequent death—the cat, upon being looked at, has a 50 percent chance of being alive. If the experiment is repeated, just as in the case of our Russian roulette player, the cat’s chances of survival continually diminish. However, if a non-collapse hypothesis, such as Everett’s, is true, then the cat will always, no matter how many times the experiment is run, continue, in at least one paralleliverse, to live. Each run of the experiment assuredly kills (one copy of) the cat, and assuredly does not kill (another copy of) the cat. Lewis calls this an “evil experiment.”

Lewis then points out how we are all Schrödinger’s cats. Even though we are not subjected to experiments, other kinds of superpositioned possibilities continually occur; every time one or another (or another) thing might happen to us, all of those things (if Everett was right) happen and don’t happen to us; some of those things can cause quite a bit of damage. “Chemical processes are no less quantum-mechanical. These include biochemical processes… so such death-mechanisms as poisoning, infection, auto-immune disease, ventricular fibrillation, or heart failure are also occasions for life-and-death branching.” The branches are simply terms of the superposition—but how pleasant are those life-branches? In an Everettian world, all those possible branches (diabetes destroys your kidney and you die, diabetes destroys your kidney and you survive but are on dialysis, diabetes destroys your kidney but astonishingly you get along just fine without it) will actually exist. But in the majority of the possible branches for, say, a man suffering from late-stage diabetes, the man either dies, or suffers a further—but not quite fatal—deterioration.

Lewis goes on to engage the other “strangenesses” of quantum mechanics in his analysis of this larger-scale (our lives) “evil” quantum mechanical experiment. Because of something called quantum tunneling, “If you stand in front of an oncoming bullet, there are branches (of stupendously low intensity, of course, and with negligible chances of being the outcome of a collapse) in which the bullet passes right through you, leaving you unscathed, or less than fatally scathed. If you stand in front of an oncoming tram, there are branches of still lower intensity in which you reappear on the other side of the tram, or in which not all of you, but enough of you to sustain life, reappears.” In an Everettian noncollapse world, those branches of stupendously low intensity—in which some confettied version of you survived that oncoming tram—actually occur. In the vast majority of the other branches, you’re dead, but in the preponderance of branches in which you do survive, you’re not feeling too good. And since any person, over time, will inevitably accrue dangerous encounters—with buses, with blood clots, with creepy microorganisms—survival tends to become less and less appealing; imagine your standard fears of aging, and then multiply them times infinity.

Lewis admits that “to be sure, there are also life-and-life branchings such that on some branches your life is improved. Your previous losses are regained: your loved ones come back to life, or your eyes or your limbs grow back, or you regain your mental powers or your health…. but improvement branches have a very low share of total intensity… In the case of the worst dangers we face, the death branches have the most total intensity, the harm branches the next most, the status quo life branches have much less, and the improvement branches have by far the least.” The eternity an individual continually steps into, never free of possible harms, therefore becomes increasingly hostile to survival, increasingly hellish (at least from the aging survivor���s point of view). “As you survive deadly danger over and over again, you should also expect to suffer repeated harms. You should expect to lose your loved ones, your eyes and limbs, your mental powers, and your health.” In the worlds in which you die, the reasoning goes, there’s no you there to enjoy the peace of that, and in the worlds in which you live, your life will almost certainly, in almost all branches, grow ever more miserable. Or, to put it in folksy terms, over time, one’s body inevitably becomes an increasingly unpleasant residence for the soul.

from Rivka Ricky Galchen, "Death Comes (and Comes and Comes) to the Quantum Physicist" (2007)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

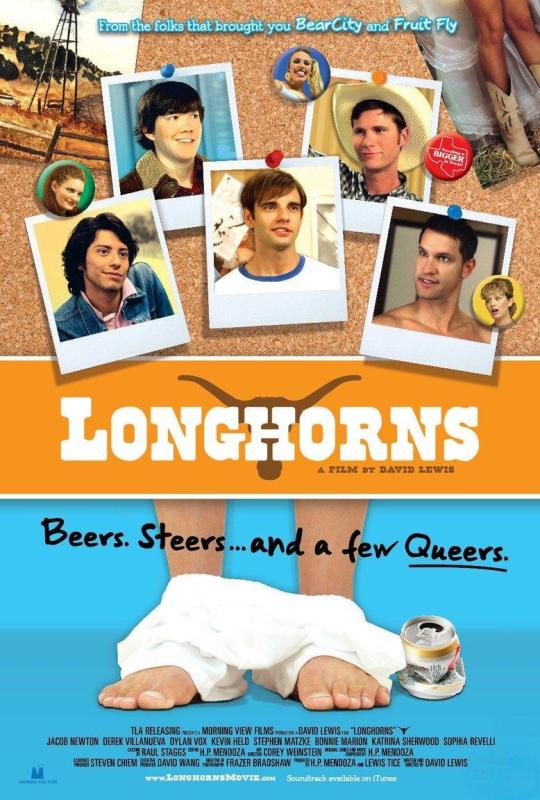

Longhorns (2011)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

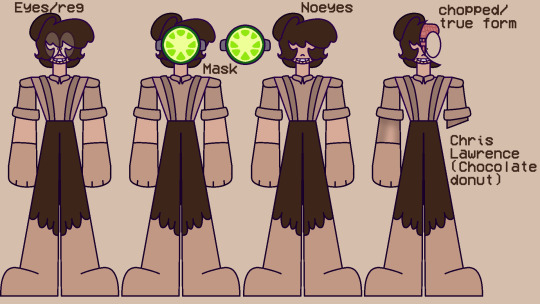

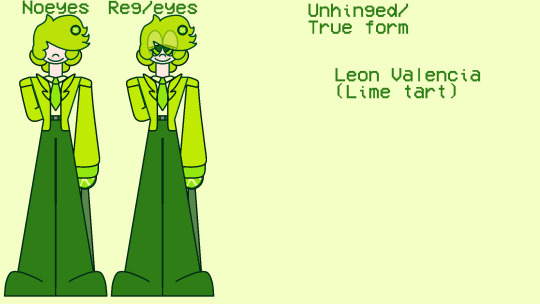

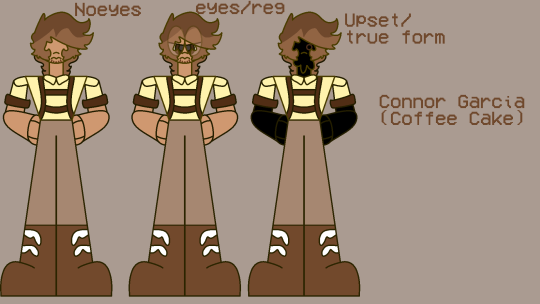

Fruits,,,(LEON ISN'T MY FAVORITE SHUT UP)(Reblogs appreciated, as is screaming in the tags!)

#my art#my ocs#my stories#Leon Valencia#Connor Garcia#Beau Mitchel#Oscar Ortiz#Gary Warner#Robert Alverez#Kellen Geiger#Sherry Berry#Sebastian Fries#Hunter Fisher#Nancy Bakersfield#David Lewis#Chris Lawrence#ask to tag#tw: body horror#tw: uncanny#tw: blood#tw: gore#fruit ocs#fruit#artists on tumblr#my oc#original story

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#general hospital#gh#soap opera#80s tv#susan moore#jackie templeton#Monica quartermaine#Alan quartermaine#edward quartermaine#david lewis#stuart damon#leslie charleson#demi moore#Gail Rae Carlson

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edward & Lila Quartermaine (David Lewis, Anna Lee).

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

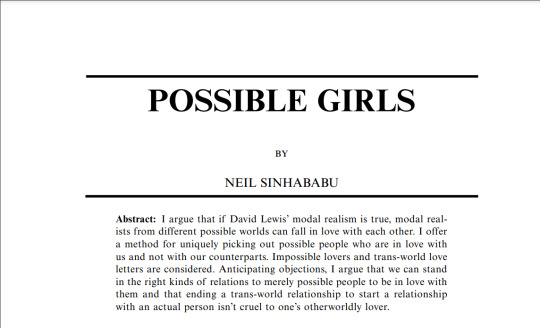

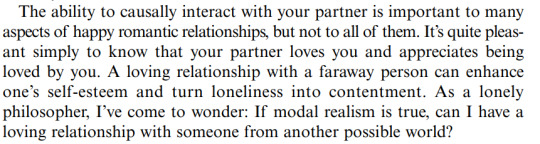

"Possible Girls" by Neil Sinhababu

#this paper is a wild ride and is totally worth reading all of it#possible girls#neil sinhababu#this paper wasn't assigned but was something i found awhile ago#but this is a respected philosopher afaik#grad school#philosophy#modal realism#david lewis#metaphysics#like it is well written.. but the application of modal realism here is SO weird#counterfactuals#high art#weird philosophy#weird academia#don't rule out impossible girls tho#academia

1 note

·

View note

Text

Seen in 2023:

Glitterbug (Derek Jarman & David Lewis), 1994

1 note

·

View note

Text

I have no idea where this rabbit hole is leading me but I might start reading On the Plurality of Worlds. Again.

#philosophy#david lewis#metaphysics is so whack dude#I tried to look through the tumblr tag for metaphysics and I think I probably shouldn't have#idk that that means#there is absolutely No Reason for me to do this btw#I kinda want to binge read Wittgenstein but I also kinda don't#stop mentally chickening out of things istg

6 notes

·

View notes