#fire ecology

Text

In the Willamette Valley of Oregon, the long study of a butterfly once thought extinct has led to a chain reaction of conservation in a long-cultivated region.

The conservation work, along with helping other species, has been so successful that the Fender’s blue butterfly is slated to be downlisted from Endangered to Threatened on the Endangered Species List—only the second time an insect has made such a recovery.

[Note: "the second time" is as of the article publication in November 2022.]

To live out its nectar-drinking existence in the upland prairie ecosystem in northwest Oregon, Fender’s blue relies on the help of other species, including humans, but also ants, and a particular species of lupine.

After Fender’s blue was rediscovered in the 1980s, 50 years after being declared extinct, scientists realized that the net had to be cast wide to ensure its continued survival; work which is now restoring these upland ecosystems to their pre-colonial state, welcoming indigenous knowledge back onto the land, and spreading the Kincaid lupine around the Willamette Valley.

First collected in 1929 [more like "first formally documented by Western scientists"], Fender’s blue disappeared for decades. By the time it was rediscovered only 3,400 or so were estimated to exist, while much of the Willamette Valley that was its home had been turned over to farming on the lowland prairie, and grazing on the slopes and buttes.

Pictured: Female and male Fender’s blue butterflies.

Now its numbers have quadrupled, largely due to a recovery plan enacted by the Fish and Wildlife Service that targeted the revival at scale of Kincaid’s lupine, a perennial flower of equal rarity. Grown en-masse by inmates of correctional facility programs that teach green-thumb skills for when they rejoin society, these finicky flowers have also exploded in numbers.

[Note: Okay, I looked it up, and this is NOT a new kind of shitty greenwashing prison labor. This is in partnership with the Sustainability in Prisons Project, which honestly sounds like pretty good/genuine organization/program to me. These programs specifically offer incarcerated people college credits and professional training/certifications, and many of the courses are written and/or taught by incarcerated individuals, in addition to the substantial mental health benefits (see x, x, x) associated with contact with nature.]

The lupines needed the kind of upland prairie that’s now hard to find in the valley where they once flourished because of the native Kalapuya people’s regular cultural burning of the meadows.

While it sounds counterintuitive to burn a meadow to increase numbers of flowers and butterflies, grasses and forbs [a.k.a. herbs] become too dense in the absence of such disturbances, while their fine soil building eventually creates ideal terrain for woody shrubs, trees, and thus the end of the grassland altogether.

Fender’s blue caterpillars produce a little bit of nectar, which nearby ants eat. This has led over evolutionary time to a co-dependent relationship, where the ants actively protect the caterpillars. High grasses and woody shrubs however prevent the ants from finding the caterpillars, who are then preyed on by other insects.

Now the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde are being welcomed back onto these prairie landscapes to apply their [traditional burning practices], after the FWS discovered that actively managing the grasslands by removing invasive species and keeping the grass short allowed the lupines to flourish.

By restoring the lupines with sweat and fire, the butterflies have returned. There are now more than 10,000 found on the buttes of the Willamette Valley."

-via Good News Network, November 28, 2022

#butterflies#butterfly#endangered species#conservation#ecosystem restoration#ecosystem#ecology#environment#older news but still v relevant!#fire#fire ecology#indigenous#traditional knowledge#indigenous knowledge#lupine#wild flowers#plants#botany#lepidoptera#lepidopterology#entomology#insects#good news#hope

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

The beginning of a blackbutt hollow on a marri tree (Corymbia calophylla).

When fire burns severely it can sometimes 'kill' the bark, even on hardy fire-adapted Eucalypts. This causes a loss of integrity and will fall away, like we can see here. Now the trunk is exposed without bark on this side. The tree will generate another bark layer, but until it does, it will be subject to insect attack and other issues.

These blackbutts are now more susceptible to damage from fire. Over the years as repeated fires effect the area, the hollow will become bigger, and fire can get 'into' the tree rather than just burning the bark, and they can burn from the inside out. We call these trees "chimneys." You will see what looks to be a normal, un-burnt tree, but it's billowing smoke out the top - because it's burning internally.

This is a giant marri blackbutt is completely burned out underneath (6'3" friend for scale)!

From beneath. By the way, this tree is still alive!

📸 @fire-ecology

#fire#fire ecology#plants#botany#plant science#ecology#wildfire#australia#bushfire#op#eucalyptus#eucalypt

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

OK, so this is apparently a thing that is not known, so:

In a controlled, intentional, prescribed burn, the goal is NOT to burn down an entire forest, and every tree in it.

- it can be done to maintain grass lands by not allowing trees to get established

- it can be done to maintain an oak-savanna ecosystem, where it does clear out very young, non-fire adapted trees, but leaves the mature oaks.

- it can be done in a ponderosa pine forest, clearing out in invasive species but leaving the pines

- it can be done over a camas field, leaving the camas and other fire-adapted species, but burning invasive or aggressive species that would otherwise out compete them.

- I've read it can be used to maintain the Native Americans' berry patches, but I haven't read into that yet

- it can be used as part of a strategy to reduce the fuel for mega fires.

Prescribed burns are about maintaining ecosystem health and diversity, not about destroying them. Banning prescribed burns was part of what colonialists did, because they assumed they knew better than the native peoples. It has caused a lot of problems, including habitat loss.

Please read further, and don't dismiss it out of hand. A whole lot of us were raised on the idea that fire is always bad, but it's not. Here's one place to start reading:

287 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Alien-ish Invasion

Spotted something while out on a walk, had to make sure I got pics. Because… well.

It looks kind of like a land-squid, no? But… it's possibly even weirder, if you think about it.

These are actually pine seedlings. In the very beginning of their "grass stage". Which is… exactly what it sounds like. Southern pines, especially longleaf, spend a couple of years as grass-like tufts, storing lots and lots of nutrients underground, so that in the space of one year they can sprout up about 6 to 7 feet or so and start looking like actual trees.

Why don't they look like trees from the very start? Because this is a fire ecology. Typical wildfires are cool, low-level fires that burn off grass and rarely reach above about 5 feet over the ground. So long as the pine seedling hugs the ground and pretends to be grass, the most a fire will do is burn off the outer needles, leaving the bud inside (and taproot of nutrients underground) intact. This can actually be beneficial, burning off mold-infected needles so the rest of the plant is healthy.

So the tree bides its time, lays up resources, and then shoots up in less than a year, counting on luck to get it out of the frying range. It mostly works.

(A pine seedling that's lost the seed coat and so looks even more alien.)

But what's even more sobering is the story behind those seeds. The conditions needed for good male pine pollen cones and good female seed cones are different. Ecologists estimate you only have a good year for both every 5 to 7 years, on average. And it can take most of two years for seeds to mature. Meaning this crop of seedlings implies the conditions were just right in... oh, about 2020, for pines to reproduce.

And now we have tiny little land squid pretending to be grass. Fascinating!

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Highlights from the Western Society of Weed Science Annual Meeting 2023

As soon as I learned that the Western Society of Weed Science‘s annual meeting was going to be held in Boise in 2023, I began making plans to attend. I had attended the annual meeting in 2018 when it was held in Garden Grove, California and had been thinking about it ever since. It’s not every year that a meeting like this comes to your hometown, so it was an opportunity I knew I couldn’t miss.…

View On WordPress

#climate change#fire ecology#herbicides#plant science research#sagebrush steppe#spontaneous urban plants#sustainable agriculture#weed control#weed management#weed science#weeds#Western Aquatic Plant Managment Society#Western Society of Weed Science#wild urban flora#Women of Aquatics#WSWS

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rising from the ashes: The “Phoenix plants” that flower the next day after burning

Imagine that you are going on a hike for two days through the savannas of the Cerrado in Central Brazil. On the first day, you see a fire consuming all the plants in the landscape, with flames several meters high. You are not that shocked since you were already told that wildfires are part of the natural dynamics of this ecosystem. The next day, you make your way back and went through the same…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Sometimes gotta remind myself that you don’t all experience fire season like we do in a fire ecology. I remember telling the bf that oh yeah for like a few weeks the air is full of smoke and ash and the sun is a blood red through a dark grey black sky. just totally normal shit for me.

1 note

·

View note

Text

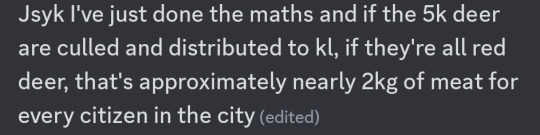

How it started:

How it's going:

@systlin made the mistake of adding a couple of quick lines about overpopulation in the King's Landing Kingswood to A Crossing of Fires and then I compounded the issue by doing maths about it and now the entire rest of the fic has been derailed

#mitraka#systlin#sys fixes westeros through the power of love and also fire and also 'power of no more bones'#and now also forest population ecology#fantasy ecology#deermageddon

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

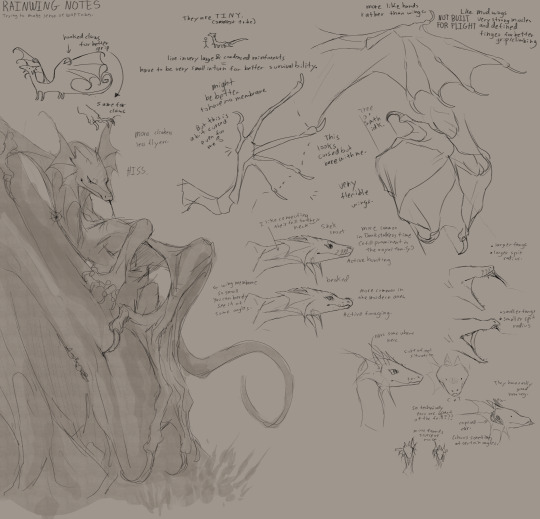

Trying to make sense of WOF tribes: Rainwings

(click image for better quality)

#wof#wings of fire#wof fanart#my art#wof notes#Trying to make sense of WOF tribes#wof rainwing#rainwing#rainwings#apologies if my handwriting is a bit difficult to read#I enjoy reading little ecology tidbits#especially fantasy ones#I always love it when media tries to make sense of their monsters and creatures from a biological standpoint#Monster hunter has done a number on me.#so this is me trying to make sense of Rainwings from a biological standpoint#with my very limitied biology knowledge#me making up for WOF's lack of tribe details#Making sense of WOF

991 notes

·

View notes

Text

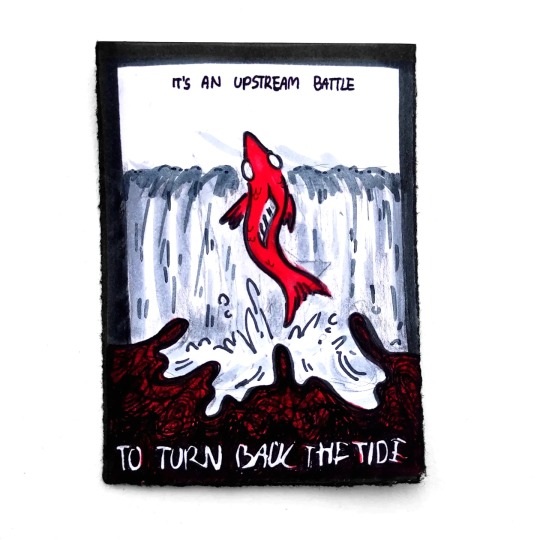

Fire suppression p.1 & p.2: “Flame Retardant” & “Building Potential” Inspired by the PEM's ‘Our Time on Earth’ exhibit

I was gladly surprised to see the exhibit’s various optimistic installations, especially the building materials of the future. As a forestry student I am beginning to understand our relationship to our forests differently. In the US, forest policy which aimed to suppress wildfires has contributed to a century-long build up of fuel that would otherwise have been cleared by controlled burns or small spontaneous ground fires. Indigenous peoples shaped the forests of the Americas to require these controlled burns. More and more I realize that indigenous knowledge and collaboration is a necessary part of the stewardship of future. A concept which is present at large at the museum but also specifically within Our Time on Earth. Getting a ‘sustainable’ amount of lumber from our forest still disregards the health and purpose of these trees to a diverse and complex ecosystem. It is essential that we diversify our building material, to include carbon-negative things like mycelium! Natural resources that are close by, and at hand in our local environment, which doesn’t require chopping down a tree 3000 miles away and transporting it to the US. We need local resources whose collective cultivation lead to a sense of community and collaboration. A better future!

My thanks to lane.m.artin for collaborating with me for p.2!

#acrylic painting#artists on tumblr#PEM#peabody essex museum#climate change#fire suppression#wild fire#TEK#Traditional ecological knowledge#controlled burning#art of mine#solarpunk#is how i would describe the exhibit but listen I am just doing my best and maybe this gallery might even see this piece in it's peripheral#and thats a win#contemporary art

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

The fire

The regeneration - only 18 months later!

The lush green is the species Acacia pulchella, an obligate seeder, which is a plant that is killed by fire and must recruit via seeds - in this case, lying dormant in the soil seed bank. It requires high soil heating temperatures from fire (~80-120°C) to break dormancy and trigger germination. This strategy allows the species to persist in a fire prone environment, and take advantage of the excellent post-fire conditions of increased nutrients from burned biomass, increased light availability, and reduced competition.

#fire ecology#plants#ecology#fire#wildfire#bushfire#botany#australia#plant science#recovery#op#fire-ecology

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

So on the surface this looks like a good thing. After all, we need mature and old-growth forests as they're havens for species dependent on that habitat type, and they are also exceptionally good carbon sinks compared to younger, less complex forests. (A big, old tree will still absorb and hold more carbon than a new, quick-growing one, and in fact for the first twenty or so years of its life a tree is actually carbon positive, releasing more than it absorbs.)

However, timber industries are trying to paint mature forests as fire hazards that need to be thinned out due to an abundance of plant life. They also tend to oppose leaving snags and nurse logs in the forest as "fuel", because they'd rather salvage what lumber they can from a freshly dead tree. So of course they're trying to push for cutting down trees as the solution to climate change's threat to mature forests.

Large, old trees are generally better adapted to surviving a fire simply by sheer size. Some have other adaptations, such as deeply grooved bark that can create relatively cooler pockets of air around the tree to help it survive, and the branches of older, taller trees of some species are higher up the trunk, away from lower-burning fires. And those old trees that survive are often important for helping to restore the forest ecosystem afterward, from providing seeds for new trees to offering wildlife safe haven and food.

When timber companies come in and log a forest, even if they don't take all the trees, they leave behind all the branches and twigs and just take the trunks. This creates a buildup of fine fuels that burn very quickly (think the twigs and paper you use to start a campfire), while removing coarse fuels that take longer to catch fire. In fact, an area that is subjected to salvage logging after a fire is much more likely to burn again within a few years due to all the fine fuels left behind by salvage logging.

Another factor is that not all forests are the same, even at similar ages. Here in the Pacific Northwest, as one example, the forests east of the Cascades live in drier conditions with slower plant growth, and low-level wildfires that can clean out ladder fuels before they pile up too high are more common. In those locations prescribed burns make sense.

However, the fire ecology of forests on the west side is less understood; because lightning storms are less common and the climate is wetter, fires just don't happen as often. And west-side forests are simply more productive, with denser vegetation that grows back quickly after even large fires like 2017's Eagle Creek Fire in the Columbia River Gorge. Historically speaking, west-side forests get fewer, but larger, fires. So the prescribed burns and other strategies employed for east-side forests aren't necessarily a good fit.

Finally, mature forests are much more biodiverse, and support many more species than a monocultural tree plantation. As climate change continues to affect the planet, mature forests and other complex ecosystems are going to become increasingly crucial to protecting numerous species, to include those dependent only on those ecosystem types. Thinning may seem like a great idea at first, but even if it isn't as destructive as clearcutting it will still damage a forest in ways that will take years to restore.

We really need to be wary of the narrative that thinning is the only way to curb climate change's effects on mature forests. It's a more complex situation than that, and we need to prioritize preserving these increasingly rare places as much as possible.

#wildfire#forest fire#forest fires#fire#forests#old growth forest#old growth forests#ecology#restoration ecology#logging#conservation#environment#scicomm#science communication#science#nature#plants#trees#climate change#global warming

397 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rathalaugust 2023 (catchup) day 21: Fulgur Anjanath

I combined my love of Anjanath chilling with its sail up with the apparent lore that the babies are fully feathered (before they lose much of it as adults).

#rathalaugust2023#monster hunter#anjanath#fulgur anjanath#kobb art#sketchbook#for some reason a lot of people diss standard anjanath but I love it also#there's just a lot of cool behavior it has#it's a great single example of the way MH World was designed re: the way it focuses on ecology & interaction with the game environment#the way its nose expands into an eldritch horror and the mucus relates to its limited fire abilities AND the traces you can track#you can follow it around and *watch* it marking its territory by snorting flammable boogers on it#underrated friend

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

Concepts for Illustration class!

Prompt: GET ANGRY focused on how the previous generation ruined our planet

#my art#illustration#nature#poster#ecology#concepts#extinct animals#fire prevention#drawings#alcohol markers#sketchdump#artschool#school stuff#uken#everything but the get-extinct one IS SO TINY can you tell??#i really love those!! sketching things out with markers is so satisfying!#i really dont like going near any serious topics with my art for various reasons but this... is turning out better than i expected c:#enviroment#enviromental#enviroment art

157 notes

·

View notes