#hödekin

Text

Invisible, and typically some degree of mischievous, there are three types of kobold: the household spirits, the mine spirits, and shipboard spirits.

Having previously covered klabautermann, those shipboard spirits, in this bestiary, the remaining types of kobold were only a matter of time.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#myth#mythology#kobold#cobold#fairy#fae#fairy miner#german folklore#german legend#cobalt#fairy ore#king goldemar#hinzelmann#hödekin#fairy tale#household spirit#mine spirit

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

mythology aesthetics

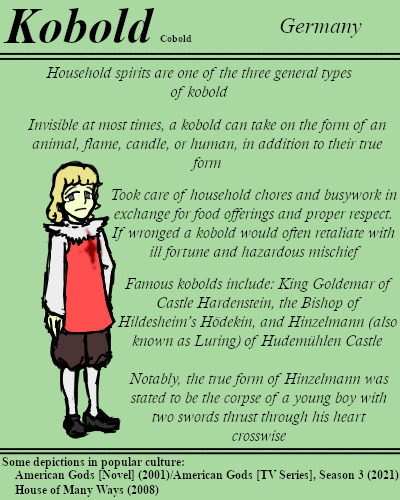

KOBOLDS

In Germanic folklore, the kobold (occasionally cobold) is a sprite or fairy. Although usually invisible, a kobold can materialize in the form of an animal, fire, a human being, and a candle. The most common depictions of kobolds show them as humanlike figures the size of small children. Most commonly, the creatures are house spirits of ambivalent nature; while they sometimes perform domestic chores, they play malicious tricks if insulted or neglected. Famous kobolds of this type include King Goldemar, Heinzelmann, and Hödekin. In some regions, kobolds are known by local names, such as the Galgenmännlein of southern Germany and the Heinzelmännchen of Cologne. Belief in kobolds dates to at least the 13th century, when German peasants carved kobold effigies for their homes. The name of the element cobalt comes from the creature's name, because medieval miners blamed the sprite for the poisonous and troublesome nature of the typical arsenical ores of this metal (cobaltite and smaltite) which polluted other mined elements.

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another round of “Why the Coming to America scenes of season 3 are a pure mess - in all the wrong ways”. After the Orisha scene that was clearly just the writers saying “Forget Nancy, let’s all hold hands and sing Kumbaya” ; and the Demeter scene which was a very sad hit and miss that completely ignored the Greek community and diaspora of America, let’s delve a bit about this scene from episode 2.

... So. If you have watched episode 9 you might have noticed that Hinzelmann kept in her house the knife that was used by settlers to kill the Native little girl on what would later become Lakeside. Right?

It is because visibly this was a sacrifice given to what would become Hinzelmann. I thought originally that it was a kill to Odin, but I actually visibly misheard it because turns out it was a kill to Hodekin, which they call “the dark one”. (I haven’t rewatched the scene but I got that from several reviews - if anyone is kind enough to check). Another thing I didn’t caught was that the guy who prayed to Hodekin was actually German. A German trader. Why didn’t I get that? Because the other guy was French. You hear him distinctely speak French, and he speaks it first. Why, just why would you mix up two different nationalities? Just to blur the lines? That’s confusing and idiot. Why not make an all-German team, huh?

For the prayer in question I was about to rant about how it is an Old Norse/Scandinavian prayer and not an Old German one, but then my rant fell a bit flat. They use the rune alphabet, true, but it was used by a lot of Germanic languages. They associate the hammer with the thunder, just like with Thor, and earlier Whiskey Jack said to Odin that his followers had slaughtered his people. It might lead one to believe this is an honor to the Old Norse gods, but then you have to rememberer that the Norse gods were also the Germanic gods, the same pantheon being worshipped on the two territories with a few differences (Odin became Wotan, Thor became Donar, but they stayed roughly the same). After that I do not have enough knowledge to identify the language spoken as Old Norse or Old Germanic, so I’ll leave it to experts. But I’ll still mention it stays overall confusing.

Especially since they threw a French in there. Why a French? Why confuse people like that?

But the treatment of Hodekin is the most confusing thing. Here Hodekin is called the “Dark One” and seemingly referred to as a god, due to the prayer and all that. Something quite serious. Except that Hodekin never was truly a god, and certainly never had a name such as the “Dark One”. Hodekin is an individual kobold (the same way Hinzelmann is the name of another individual kobold). And while Hödekin was reported as a folkloric kobold in the 19th century, Hinzelmann’s legend can be dated to the 16th century, well before this Coming to America scene (which is in 1690).

All that being said, it is theorized that the scene actually referred to Hodr, a blind god of Norse mythology, usually associated with cold and darkness. But... to my knowledge Hodr did not actually had Germanic counterparts and stayed mostly a Norse entity? I’m not sure, but I think it is the case. And why would Hodr devolve into a Germanic kobold that specalizes himself in protecting houses, families and bring good fortune? For Mad Sweeney it made sense, because it was based on real facts (the Tuatha dé Danann, the Germanic pantheon, was later associated and fused with the Daoine Sidhe, the people of the Sidh, aka the otherworld where lived mixed together gods, fairies and the dead, and thus it was believed the “people of the mounds” and “fair folks” were descendants or a lesser form of the old Celtic gods). But here?

Plus on top of that they entirely skipped the actual backstory of Hinzelmann in the novel. Aka the fact that while in Germanic folklore he indeed became a kobold/sprite/house spirit, his “career” as a god dated from pre-Roman times, as a “god” of a nomadic tribe that had settled in the Black Forest.

Anyway, this isn’t as bad as the other Coming to America scenes, but it stays confusing and weird. If you have more cultural informations, don’t hesitate to share

12 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Would you like another story, my dear? It isn’t as pretty as my last, I’m afraid.”

“Before moonset?” I glanced through the threshold to the world above.

He laughed. “We have time enough for this.”

I nodded.

“Once upon a time, a savage, violent time, humans, goblins, kobolds, Hödekin, and Lorelei lived side by side in the world above, feeding, fighting, preying, slaying. It was, as I had said, a dark time, and Man turned to dark practices to keep the blood tides at bay. Sacrifices, you see. Man turned against brother, fathers against daughters, sons against mothers, all to appease the goblins. To stop the needless deaths, one man - one stupid, foolish man - made a bargain with the old laws of the land, offering himself as a sacrifice.”

“A brave maiden,” the Goblin King corrected.

I smiled.

“His soul was the price,” he continued. “The price he paid to sunder the goblins and the fey from the world above. His soul - and his name. No longer a mortal man, he became Der Erlkönig. For his bargain, the foolish man was granted immortality, and the power to manipulate the elements as it suited his needs. He restored order, seasons progressed in their normal manner. But the further away from mortality he grew, the more capricious and cruel he became, forgetting what it was like to live and love.”

He was right; it wasn’t a pretty story. What did immortality do to one who was once mortal? It stretched him thin. I watched what little I could see of the Goblin King from my vantage point. In this half-light, in this half-space between the Underground and the world above, I thought I could see the mortal man he might have been. The austere young man in the portrait gallery. That soft-eyed young man who had been my friend.

“It isn’t just the life of a maiden I needed, you know,” the Goblin King said quietly. I glanced sharply at him; his tone had changed. “It was what a maiden can give me.”

“And what is that?”

His smile was crooked. “Passion.”

Heat flared in my cheeks.

“Not that sort of passion,” he said quickly. Did I imagine things, or were his cheeks tinged a faint pink? “Well, yes, that too. Passion of all sorts,” he said. “Intensity.”

“Goblins do not feel the way mortals do,” he went on. “You humans live and love so fiercely. We crave that. We need that. That fire sustains us. It sustains me.”

“Is that why you stole Käthe away?” I looked at my sister, thinking of her voluptuous body and inviting laugh. “Because of the passion she inspired?”

The Goblin King shook his head. “The sort of passion she inspires in me is all flash and no heat. I need an ember, Elisabeth, not a firecracker. Something that burns longer, to keep me warm for this night and all other nights to come.”

“So Käthe …”

I could not finish my question.

“Käthe,” he said in a low voice, “was a means to an end.”

The way he spoke of my sister vexed me. A means, as though she were cheap. Disposable. Worthless.

“To what end?” I asked.

“You know the answer, Elisabeth,” he said softly.

And I did. The goblin merchants, the flute, all the way back to when he had granted my wish to save Josef’s life - everything he had done, he had done for me.

“A means to an end,” I whispered. “Me.”

He did not deny it.

“Why?”

The Goblin King was silent for a long while. “Who else but you?” he asked lightly. “Whose life would you rather it be?”

He was avoiding answering my question. We did not look at each other. The darkness was too complete, and the light from the world above too harsh. But I could feel an answer between us, pulsing like a heartbeat. It made my breath come faster.

“Me,” I said, a little more loudly. “Why me?”

“Why not you?” he returned. “Why not the girl who played her music for me in the Goblin Grove when she was a child?”

He had said so much, yet nothing I wanted to hear. That he desired me. That he had chosen me. That he … I wanted to hear the truth in his eyes said aloud. I could feel his gaze upon every part of my body: on my neck, where my shoulder disappeared into the torn sleeves of my blouse, the line of my collarbone as it led to my décolletage, the swell and ebb of my breasts as I breathed. I had waited for this my entire life, I realized. Not to be found beautiful - but desirable. Wanted. I wanted the Goblin King to claim me as his own.

“Why me?” I repeated. “Why Maria Elisabeth Ingeborg Vogler?”

I held his eyes with mine. He had his pride, but so had I. If I were to make good on the promise I made that little dancing boy in the wood all those years ago, I needed to hear validation from his own lips.

“Because,” he said. “Because I loved the music within you.”

I closed my eyes. His words were the spark to the tinder lining my blood; they touched my heart and warmth blazed from within, spreading through me like wildfire.

“A life for a life,” I said. “Does that mean … does that mean the sacrifice must die?”

“What does it mean to die?” the Goblin King asked. “What does it mean to live?”

“I told you I don’t find the philosopher charming.”

A laugh, a real, startled, human laugh. “There is,” he said, “no one like you, Elisabeth.”

“Answer my question.”

The Goblin King paused. “Yes. The sacrifice must die. She must leave the world of the living and enter the realm of Der Erlkönig, enter the Underground.” He lifted his eyes to mine, those mismatched eyes, so startling, so beautiful. “She will be dead to the world above.”

Dead to the world above. I thought of Papa, Mother, Constanze, Hans, and, with a painful twinge, Josef. In many ways, I was already dead.

“We have both lost,” I said.

He gave me a sharp glance. “What do you mean?”

“You win, I lose my sister. I win, I condemn the world above to eternal winter. Is that not the true outcome of our game, Mein Herr?”

He could not deny it.

“Then I propose we call a draw. Then we both get what we want. I, my sister’s freedom and you” - I swallowed - “will have me. Entire.”

He was silent for a long while. “Oh, Elisabeth,” he said. “Why?”

I looked at where Käthe lay, still senseless on the floor. “For my sister.” I pulled her into the circle of light. “For my brother.” I looked from Käthe to the hollow above us. “For my family. And the world above.”

The Goblin King moved closer, slowly and haltingly, as though in pain. “That is not enough, Elisabeth.”

“Is it not?” I asked with a dark laugh. “Is the world not enough? Could I condemn everyone to an eternal winter, spring and life never returning?”

He hovered on the edge of the circle of light. I could see the figure of his body outlined in silver and black, and the slim shape of his hand just beyond the circle’s edge.

“Always thinking of others,” the Goblin King murmured. “But that’s still not enough. Don’t you ever make any wishes for yourself, Elisabeth?”

What would be enough? He had an answer he wanted to hear, but I withheld it. Games and more games. We would always be dancing with each other, the Goblin King and I.

“All right, then,” I said. “For love.”

It was a while before he spoke. “For love?” His voice was rough.

“Yes,” I said. “After all, we all make sacrifices for love.” I leaned over and kissed my sister on the forehead. “We make them every day.” I lifted my eyes to where his shadow stood beyond the edge of light. The two-toned eyes gleamed at me and while I could not see the rest of his face, the hopefulness in them moved me. “You called me selfless,” I said. “So I claim selfishness. Because for once, I want to love myself best, instead of last.”

He said nothing. He was silent so long I feared I had made a mistake, but then he opened his mouth to speak.

“Think well on this, Elisabeth.” There was a fervor in his voice I could not quite discern. “Your choice, once made, cannot be unmade. I am not so generous as to offer you your freedom again.”

I hesitated. I could fight him. I could force his hand, make him bring Käthe and me back to the world above. I’d defeated him before and I could do it again.

But I was too tired to fight. Moreover, I did not want to fight. I wanted to surrender, because surrender was the greater part of courage.

“I offer myself to you.” I swallowed hard. “Free and of my own will.”

“For yourself?”

“Yes,” I said. “For myself.”

The longest pause of all. “All right.” His words were scarcely audible in the large cavern. “I accept your sacrifice.” By my feet, Käthe began to murmur and moan. “I shall bring your sister to the world above and then” - his breath caught - “will you consent to be my queen?”

I turned my face away.

“Elisabeth.” The way the Goblin King said my name made my heart flutter. “Will you marry me?”

This time, it was a long time before I replied.

“Yes,” I said. “Yes, I will.

Wintersong by S. Jae-Jones

#wintersong#s jae-jones#quotes#books#book quotes#elisabeth#liesl#the goblin king#the lord of mischief#the lord of the underworld#der erlkönig#marriage#wedding#stories#legends#myths#love#sacrifice#death#life is short books are longer

6 notes

·

View notes