#huwawa

Photo

Source details and larger version.

There would have been more, but I got lost: my modest collection of vintage labyrinths and mazes.

337 notes

·

View notes

Text

ON the Right, having beat out Sei Shonagon, Humbaba moves forward to challenge her next opponent!

ON the Left, stepping up to challenge the Cedar Forest Beast! The Mighty Valkyrie and Wife of Sigurd, Brynhildr Approaches!

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Huwawa | Fate | 11 Icons

[ Dropbox ]

Medium: Manga / Light Novel

Please Like or Reblog if you are using!

None of the Art is by me, all of it belongs to its original Curator.

Examples:

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Epic of Gilgamesh: Mankind’s First Story? - Historic Mysteries

The Epic of Gilgamesh: Mankind’s First Story? – Historic Mysteries

https://www.historicmysteries.com/epic-of-gilgamesh/

View On WordPress

#Akkadia#Akkadian#Ashurbanipal#Babylonia#Circa 2100 BC#cuneiform#Enkidu#Gilgamesh#Huwawa#Iraq#Ishtar#Kuwait#Mesopotamia#Mesopotamian Pantheon#Middle East#Nineveh#Shamhat#Sky God Snu#Syria#Ur#Uruk#Utnapishtim

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

rough sketch then clean sketch then line art then flat colors and then finally rendering

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

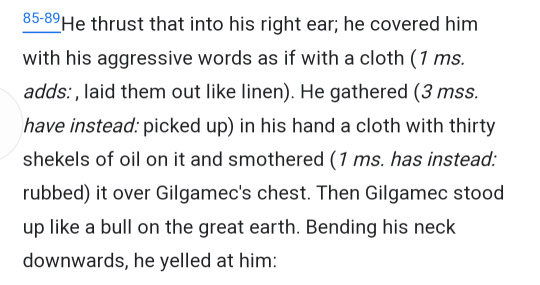

Hello, I wanna ask, what exactly measurement of "shekel" in Sumerian? The reason I asked the question is because of this passage on "Bilgamesh and Huwawa" poem

I did some googling but other than Israel currency, shekel is only appeared as measurement for weight like silver, and 30 shekels are more n less equal to 340 gr. But I don't think that measurement is ever used in liquid object like oil? (CMIIW) Also isn't 340 gr oil too much to be used only to wake up someone (but to be fair, Gilgamesh's chest was explicitly noted to be massive)? Or is that the weight of oil + cloth that Enkidu used? Or did that mean something different entirely?

Hello! The term "shekel" is a translation of the Sumerian unit ging 𒂆, which was 1/60 of a mina, and could be used for weight of any object (though silver is most common). The exact weight of a ging could vary, anywhere between about 8 and 12 grams. The phrasing in the original text is tug 30 ging ia "a cloth (of) 30 ging of oil," which means the amount of oil would convert to around 300 ml, between a cup and a cup and a half. To me that doesn't seem unreasonable for attempting to fully smother a demigod's chest in oil, not just to wake him up but to prepare him for his day - oiling of the body was a common practice, and, for example, is a key part of the "humanization" of Enkidu in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Do note that the term ging can also refer to a separate unit of volume, which Halloran lists as about 0.3 cubic meters. This would convert out to about 2,378 gallons of oil, which is definitely not what's meant here.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

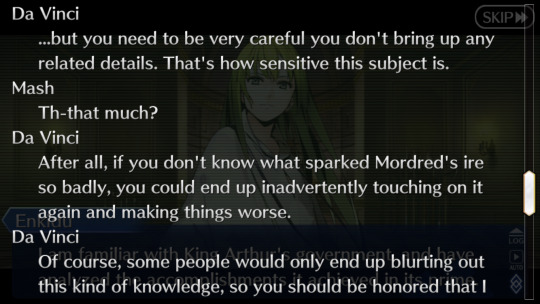

Doing enkidu’s second interlude today and man it sure is great that the first Morgan le fay we actually properly meet has 0 connection to mordred so none of horrific pain and suffering she intentionally caused actually gets addressed

#my post#GIRL#they really were like ‘yeah you know how we said phh morgan liquified babies to make mordred and that super traumatized them? anyway#‘here’s a morgan who doesn’t even have a mordred. she’s a good parent now :)’#like. no offense but die#I’m not explaining it properly but they outright said huwawa and mordred were made the same way and huwawa’s#situation was incredibly cruel#which SHOULD have had payoff when Morgan showed up!!! damn!!!

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mayblade Day 26- Monochrome

life can seem dull sometimes

#mfb#metal fight beyblade#hikaru hasama#huwawa gonna draw cute stuff in a bit but I had to get this out lol#mayblade 2022

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crush sent me a video of her working with the actual epic of gilgamesh at work

I have never been more attracted to a person than this moment

#you’re in her DMs#I’m pointing to lines on the actual tablet of the elic gilgamesh#discussing huwawa#e

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dearest Enkimoots (Epic of Gilgamesh Mutuals), today I have learned that the Epic of Gilgamesh is made up of 5 sumerian poems (Gilgamesh and Huwawa; Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven, Gilgamesh and Agga of Kish; Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld; and Death of Gilgamesh) dating to over a thousand years before the full Epic (which was in Akkadian).

I know I will be reading these along with The Descent of Ishtar and Eridu Genesis (The Flood Myth), so i thought you all may also like it.

#the epic of gilgamesh#autism#enkidu#humbaba#literature#poems#poetry#history#historical lit#gilgamesh

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

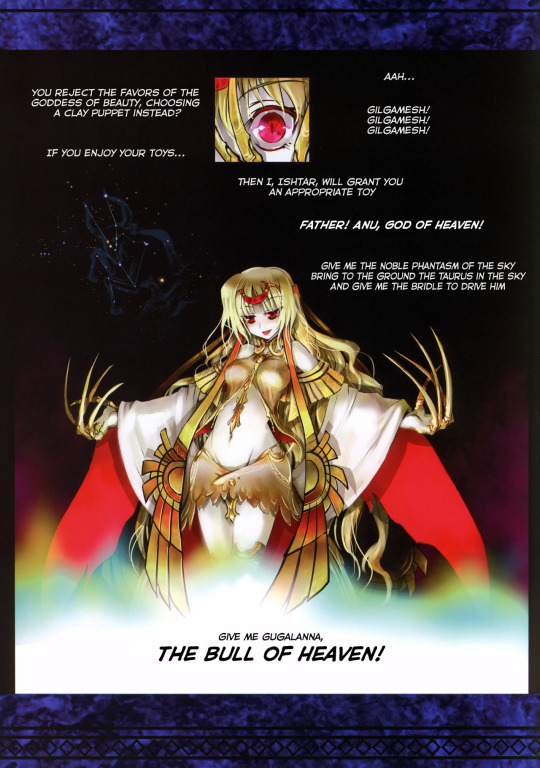

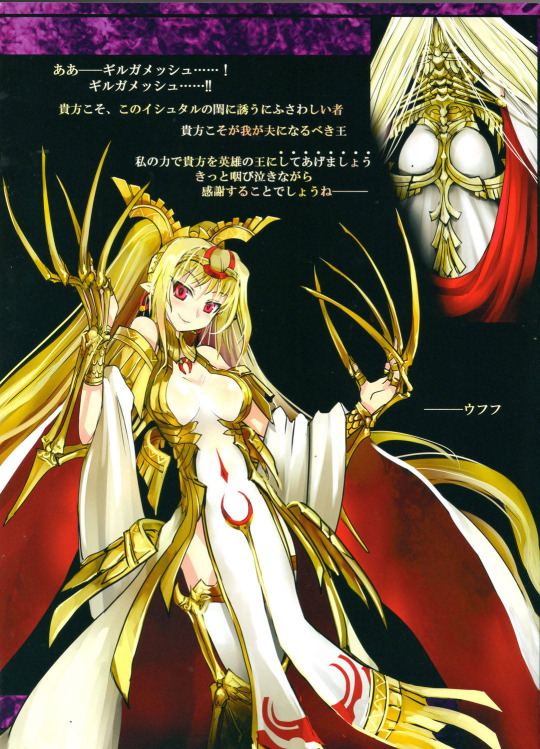

So come to find out that the Ishtar design from PFALZ that got spread around isn't actually from the same doujin where Gugalanna's design comes from (sorry reignsan!). PFALZ actually made two different doujins for different monsters from the Epic of Gilgamesh, and the design that people point to is actually from the doujin for Humbaba/Huwawa and not the one for Gugalanna (Ishtar actually has a different design in that doujin!).

I think the golden skeletal parts get people confused but you can actually see the differences between the two designs here.

I think I also see the idea that this design is canon pop up here and there because of Gugalanna and to be clear, PFALZ wasn't working with Type-Moon when he created these designs. (EDIT: Unsure if I was high as a kite when I wrote this but I have no idea what compelled past me to say this, please disregard this bit) Gugalanna was designed a full five years before it would be put into F/GO but it wasn't canon for a long time. This can also be seen in the fact that his Huwawa design is also not the design Huwawa has in Strange/Fake.

(Although personally, it fucks)

It's a very interesting take on Ishtar but there's nothing to support it being canon.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Epic of Gilgamesh: The World's First Big Budget Adaptation

My Yuletide assignment this year was an excuse for me to reread (and rediscover everything I loved about) The Epic of Gilgamesh ‒ and I can seldom resist the excuse to ramble about this kind of thing, but where do you even start, with a work like Gilgamesh? It’s the world’s oldest (known) work of literature, it features an all-but-canon m/m romance, and (even from incomplete reconstructions from languages which have been dead and alien for millennia) its central themes and most striking imagery still resonate to this day.

But perhaps my favourite thing is that it’s also what amounts to the world’s first ever big-budget adaptation of an existing story, complete with extra of sex and violence, a tropey bromance between its male leads, gratuitous cameos from other popular mythic figures, and even this one wonderfully confusing deleted bonus-scene, tacked on at the end like a DVD extra. I’m not even kidding.

Let me explain.

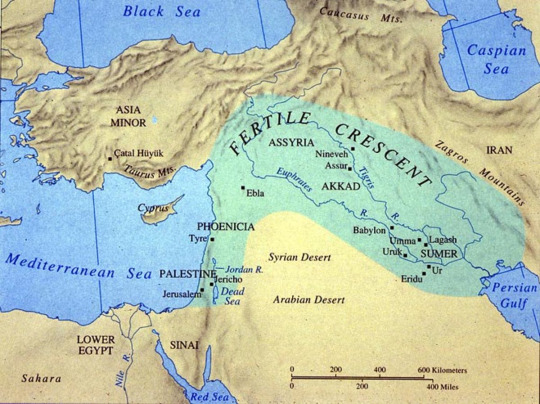

The oldest surviving stories about Gilgamesh – a semi-divine, semi-mythical Sumerian king – were inscribed on clay tablets in ancient Mesopotamia (modern day Saudi Arabia) somewhere around 2000 BC. Five distinct poems from this era have survived in variously-complete format. Gilgamesh and Akka tells of how Gilgamesh gained independence for Uruk from the kingdom of Kish (ruled by the titular Akka, in what seems to be the one Gilgamesh tale most likely to have some real historical basis). Gilgamesh and Huwawa and Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven both recount his battles with their respective monsters. Gilgamesh and the Netherworld deals with the death of his servant Enkidu, whose shade is briefly allowed to return to the mortal realms to report on what awaits in the hereafter. And finally, The Death of Gilgamesh deals with Gilgamesh’s death from illness, the gods decreeing that semi-divine isn’t sufficient for immortality.

But these aren’t the best-known version of Gilgamesh. A few centuries later, someone took those existing tales and reworked them into a single, cohesive epic, spanning 11 tablets (plus one confusing bonus tablet that we’ll get to later on). The new, integrated epic promotes Enkidu from merely a servant to Gilgamesh’s equal: created to be his companion by the gods, in answer to prayers of the people, exhausted by Gilgamesh’s tyrannical rule.

In all the best traditions of modern shonen manga, Gilgamesh and Enkidu meet, fight, and then become fast friends. Together, they battle both Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven, in episodes only lightly reworked from the original poems. But this time, these acts anger the gods, and their punishment is Enkidu’s death. Distraught at the loss of his friend, and faced with the horror of his own mortality, Gilgamesh goes on a quest to find the one man the gods ever made immortal: Utnapishtim, the Sumerian Noah (our gratuitous cameo). But Utnapishtim can only tell Gilgamesh that, short of saving the world from another biblical flood, his quest is a fool’s errand. Finally accepting his own mortality, Gilgamesh returns home. (This is, of course, a very summarised version of the full epic, but you get the general gist.)

Comparing the epic to the ‘original’ poems can be a little fraught, considering that even after reconstruction from multiple different partially-preserved copies, there are still gaps in both versions. We can only speculate whether there might have been other Sumerian poems that haven’t survived ‒ let alone how many other variations existed in oral tradition throughout the region and beyond. But for all the epic version adds and changes, what stands out most is how they’ve picked up and expanded on what was already the strongest running theme of the Sumerian stories: mortality – whether that be the desire to leave behind a record of great deeds to be remembered by (such as the slaying of monsters), or more explicitly in those final two poems, dealing with Enkidu and Gilgamesh's deaths.

For all that’s been added, the promotion of Enkidu to Gilgamesh’s equal does have more basis in the Sumerian originals that it might first appear. Though explicitly only 'a servant', Enkidu is the only other character appearing (or at least mentioned) in every poem, aiding his king in his struggles against Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven. In sending Gilgamesh to the netherworld upon his death, the gods even note that he will be reunited with his ‘beloved’ Enkidu, whose death he so fervently mourned. And though everything else in the circumstances of Enkidu’s death has been changed, both versions render it a major event, and one that leaves Gilgamesh heartbroken.

There’s even a trace of epic!Gilgamesh’s tyranny in Gilgamesh and the Netherworld, where he so exhausts the men of Uruk with his games and contests (similar accusations to the first chapter of the epic) that the gods themselves step in, arranging for his favourite toys to fall through a crack in the earth into the Netherworld (prompting Enkidu to volunteer to retrieve them… and you can see where this is going).

But for all the adaptation takes from those old poems, some of its most striking chapters are (as far as we know) completely new – including all of Enkidu’s backstory. The Gilgamesh of the epic is still respected as a wise and powerful ruler, and he still exhausts the men of Uruk with his contests, but now, he’s also been asserting his right to droit de signeur (yes, really – that trope goes this far back), and his people aren’t happy. The gods’ solution is to make the semi-divine Gilgamesh an equal: Enkidu the wild man, raised in the wilderness by beasts. Nearly as huge and powerful as Gilgamesh himself, Enkidu soon becomes a problem for hunters trying to make their living nearby.

How do you solve a problem like a wild man? Well, obviously, you introduce him to sex.

Gilgamesh’s solution to the Enkidu-problem is to send Shamhat, a cultic prostitute of the temple of Ishtar (ritual sex was apparently a Big Thing in some ancient fertility cults) – and it works. After a full seven days of sex with Shamhat (look, this is why you send a professional), Enkidu finds he can now understand the language of men, but the wild animals reject him. Something stirs in him when Shamhat tells him of Uruk and Gilgamesh, but the tipping point comes when he learns Gilgamesh is due to make a scheduled appearance at an upcoming wedding (ifyouknowwhatimean). Enkidu rushes to Uruk, intercepts Gilgamesh on the very doorstep of the bride in question, and the two demi-gods proceed to throw down. And then become instant BFFs. Seriously, I wasn’t kidding about how very Shonen Jump it is; I don’t know what else to tell you.

Now, to what degree these new intro chapters were an excuse to sex things up and get the audience’s attention, I can only speculate – but there is a lot of sex in these first two tablets (and next to none afterwards). Regardless, this feels like the perfect place to segue into what for many will be the more pressing question: just how gay is the Epic of Gilgamesh?

Because I mean, just on a surface level, it’s already pretty suggestive: Enkidu, having newly discovered sex, shows up to pointedly cockblock Gilgamesh’s appointment with a young lady, and one round of (ahem) "wrestling" later, suddenly they really like each other. And the mere fact the gods’ solution to "this guy keeps exhausting all our men and fucking all our women!" is to send him Enkidu… you’ve got to wonder if he’s just a wrestling partner on Gilgamesh’s own level, or is he meant to satisfy other needs as well?

But you really don’t need slash-goggles to find subtext in this tale. Even the academics are here for this one.

Significantly, Enkidu’s coming is foretold to Gilgamesh in a series of prophetic dreams, helpfully interpreted for him by the goddess Ninsun, his mother. In the first, Enkidu is represented by a meteor that falls down before Gilgamesh – and to quote George’s translation directly, Gilgamesh recalls, “Like a wife I loved it, caressed and embraced it.” This is not what you'd call ambiguous wording. His mother corrects this only in that the meteor is to be a man – and to drive this point home, Enkidu spends much of the rest of the poem being described as having strength “as mighty as a rock from the sky.” If that wasn’t all suggestive enough, one might also note that Enkidu does his share of “caressing and embracing” (that same wording, presumably going all the way back to the original language) of Shamhat during their week-long sex marathon too.

Then Gilgamesh has his second dream – almost beat-for-beat identical to the first, except that now Enkidu appears as an axe rather than meteor. This is a little more confusing. Both are certainly dangerous objects which hit hard, but axes don’t generally fall from the sky, and Enkidu is never compared to an axe again. So why include it?

The most compelling (and really the only) academic explanation I’ve seen put forward is that both objects may be playful Akkadian puns. Kisru (meteor) evokes kezru, and hassinu (axe) evokes assinnu – and both kezru and assinnu are apparently terms for types of male cultic prostitute: men who have sex with other men. Lest you wonder if this might be reaching, that amazing “Like a wife I loved it” line is still right there. It all adds up.

Before we get too carried away with pre-historic queer representation though, it’s notable that even in a time where apparently no-one batted an eye at male cultic prostitutes, the Gilgamesh/Enkidu subtext would be left largely as the stuff of implication – but the pattern is also weirdly familiar. Like modern media adaptations from Sherlock to Captain America: Winter Soldier, it’s plain the screenwriters absolutely want to imbue their central male/male relationships with all the intensity and pathos (and maybe even a bit of wink-wink-nudge-nudge) of a romance, and yet stop short of making it explicit. I cannot begin to guess whether the same forces were in play here, but the resonance is still pretty striking.

We’re still not done with gay-Gilgamesh-shenanigans though, because we’ve still got to cover that mysterious, DVD-extra of a 12th tablet, which may-or-may-not include an actual, textual statement of how much Gilgamesh likes handling Enkidu’s dick.

This one is going to need some more context. See, the 12th and final tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh consists of a fairly-literal Akkadian translation of the latter half of the original Sumerian poem, Gilgamesh and the Netherworld. Narratively speaking, this is a bit of a record-scratch moment, because not only has the epic already reached its logical conclusion as of the end of tablet 11, Gilgamesh and the Netherworld is the one that revolves around the death of Enkidu – and in the new epic version, Enkidu has already died in completely different circumstances, way back in tablet 7. So what the hell is it doing here?

The best guess as to why anyone felt the need to include this episode in its original form is that the bulk of the original Sumerian poem relays a detailed account of how one’s actions in life will affect one’s prospects in the hereafter. Enkidu’s shade dutifully reports that a Sumerian citizen who hopes to be comfortable in the netherworld must have plenty of sons (to make offerings in the name of their departed father), must show respect to the gods, must die peacefully – the list goes on. The material has transcended the world of poetry and moved into scripture – and that may have been considered worth preserving long after the original tales were lost.

So where does the dick-touching come in? Brace yourselves: Enkidu’s account of the netherworld includes some graphic details about what happens to your junk. That crotch you touched, so that your heart rejoiced, is filled with dust like a crack in the ground. And so on.

Here’s where making definitive statements about this passage get messy. There are at least two different versions (the original Sumerian and the one from the epic) in different languages, and not always preserved well enough that all the words are still legible. So I’ve seen translations where it seems to be Enkidu’s own body that Gilgamesh ‘rejoiced to touch’. I’ve seen versions where it seems to be some unnamed woman’s body instead. Or maybe Enkidu’s saying that even having a wank isn’t worth much rejoicing in the afterlife (and for the record, I’ve seen all the above in just the work of just one author, Andrew George. Consensus is not a luxury we have here). There’s some ambiguity there, and I have no idea how much of that is down to interpretation, translation, or the actual state of the text. The 12th tablet of the epic of Gilgamesh remains a mystery stuffed into an enigma (then presumably filled in with dust).

Anyhow, back to the main text of the epic. From the meeting of Enkidu and Gilgamesh, things happen surprisingly fast. Gilgamesh immediately proposes a trip to the cedar forest to slay the monster Huwawa: an act which so impresses the goddess Ishtar that she hits on Gilgamesh, he rejects her, and she sends the Bull of Heaven to punish him. Angered by the death of both Huwawa and the bull, the gods inflict a fatal illness on Enkidu, whose death leaves Gilgamesh heartbroken. Like screenwriters trying to cram everything from Captain America’s origin story to his emergence from the ice into a single movie, the complete tale of Gilgamesh’s time with his literally-god-given-soulmate seems like it’s been compressed down to maybe a couple of months, max. But such is the nature of adaptations like this one.

But the best parts of the epic are hardly over. Gilgamesh’s search for Utnapishtim, the one man ever made immortal by the gods, will see him meet scorpion men and stone men, will take him across a sea whose very touch is death, and force him to race the sun through the tunnel it takes each night under the earth. He finds the man he seeks at the end of the world – which is our poet’s excuse to include the entire Sumerian flood myth in the narrative, as Utnapishtim recites exactly what he had to do to earn his immortality.

Gratuitous as it may be, this is not a complaint. I kind of love the pre-biblical Sumerian version of this story – not least because, despite being initiated by the most revered of the gods, the deluge sent to punish mankind for their ills is unambiguously framed as a mistake. Mankind is saved only because Ea, wisest of the gods, sneakily breaks his oath of secrecy by alerting Utnapishtim to the danger and directing him to build his ark – and Ea gets away with it by directing his warning not to the man himself but to the fence outside his home, so he can honestly tell the other gods “Who me? I didn’t tell anyone, I only whispered it to a fence!” (I like to imagine him walking away from that initial meeting with the other gods rolling his eyes, going, “Well someone’s gonna regret this in the morning, you just wait. Alright, alright, damage control time…”)

And the gods absolutely do regret the deluge. When at last the rain stops, and Utnapishtim lights some incense in ritual thanks to the gods for his survival, the text describes the parched gods clustering around the smoke of the offering like flies. To find something like that – that comes so close to suggesting that the gods themselves depend on humanity for some measure of their power and comfort – in a text this old blows my mind a little. It’s also a hell of an image.

In any version of Gilgamesh, the general attitude to the gods has a lot of commonalities to what you’d find in, say, Greek mythology. The gods are absolutely divine and worthy of worship, but also come across as one huge, long-running soap opera of privilege, dysfunction and pettiness. Even the Athenians, though, generally kept the image of their patron goddess Athena reasonably clean. By contrast, when Uruk’s own patroness Ishtar appears in the tale, her role is to hit on Gilgamesh, be rejected, go crying to her father for help, and send the Bull of Heaven down for revenge. Gilgamesh insults her, kills the bull, and even hurls part of its carcass at her as a parting blow. He then makes flasks of its horns and presents them to her own temple in her honour. For bonus confusion, the original Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Netherworld also opens with a passage where Gilgamesh does Ishtar a much-appreciated favour in clearing out the demons infesting a divine tree. What on earth are we supposed to make of it all? The worship of Ishtar must have taken some truly god-level compartmentalisation.

Much as I love Gilgamesh, some of it is inescapably pretty impenetrable to the casual modern reader. If you were paying attention back at that very first bit about Gilgamesh and the Netherworld, for example, you might have caught that plot point where the great king Gilgamesh so exhausted all the men of Uruk with his games that the gods themselves had to step in and take his toys away. What those toys were isn’t totally clear, but the best guess seems to be a ball and a mallet. These were made of wood from that divine tree, but even so – was ancient Sumerian croquet really that intense? You’ll run into stuff like this a lot reading any version of Gilgamesh – scholars will do their best, but some of it just doesn’t translate, reminding you you’re reading something written in a cultural context no-one’s seen in over 4000 years.

But that only makes it all the more fascinating when (like finding bits of Shakespeare in the infinite monkey cage) you run into the stuff that does still resonate. I could not tell you why Gilgamesh begins his case for why they should rebel against Kish with a spiel about the digging and/or operation of wells – but then you get to the bit where Akka compares Uruk with its great city walls of Uruk to a cloudbank sitting on the earth, or the part where Enkidu finally responds to Akka’s repeated demands of, “Slave, is that man your king?” with, “That man is indeed my king!” – and even separated from the poet by several millennia and the hard work of so many archaeologists to piece this thing back together, the words and the imagery still get me.

I could go on here. There’s so much I love in the various versions of Gilgamesh, so much that fascinates me and confuses me (and has very much tipped me back down multiple research rabbit-holes trying to get my head around it). But as both a gigantic nerd and fanfic writer, my favourite thing might still be learning just how far back the human tradition of telling and retelling old stories goes, recreating and adapting them in new formats, to resonate with new audiences. There isn’t a doubt in my head that even way back in ancient Akkadia, there were grumpy old fans arguing that this modern newfangled epic isn’t a patch on the proper old Sumerian poems – look at all the good bits they skipped and all the stuff they got wrong! Why, you realise they aren’t even teaching scribes proper Sumerian in school anymore? Pah, no respect for the classics!

Anyway, if you’ve never read the Epic of Gilgamesh in full (and it’s really not so long it’ll take you long to do), this would be my cue to recommend you Stephen Mitchell’s version as probably the most accessible English language introduction. This one is (in his own words) explicitly a version, not a translation: Mitchell isn’t a Mesopotamian scholar, but a poet, and his goal was to create something in semi-modern verse that captures as much of the original as possible in a format more accessible to the contemporary English-speaking reader ‒ patching over the holes as best as possible. And I can only applaud him the effort: after all, it’s nothing people haven’t already been doing with Gilgamesh for thousands of years.

But if you’d like to go a bit further down the rabbit hole, my other key source was Andrew George’s translation. George is an academic, and his version is a far more literal translation, preserving the gaps where we still don’t know exactly what’s missing, but including as much as possible from the various different versions which survive to us in different places – including those original Sumerian poems. Both Michell’s and George’s books are available quite cheaply as ebooks. (George’s much-longer and much-more-academic two volume work on Gilgamesh isn’t available as an ebook, alas, but can also be found in pdf format pretty easily on the web too).

Finally, I’ve got to rec you Irving Finkel’s talk on his work on even older versions of that flood myth – it’s only tangentially related to Gilgamesh, but damn, it’s fascinating too!

106 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello! i have two questions for you:

how did the hittites(?) adopt gods into their pantheon? did they change any major parts of the myths or was it just eating them whole? something else?

what was the phd-obtaining process like?

I have two answers for you! They are both long; brace yourself.

1. The short answer is: yes, they totally changed all sorts of stuff, except when they maybe didn't. The long answer is complicated and difficult, because we have almost zero examples of the original myths/rituals/etc: most of the people from whom the Hittites adopted gods didn't keep written records of their own. So we can't do a side-by-side comparison of, say, a myth from Kizzuwatna (a territory in southeastern Turkey that was conquered early on) and the same myth from the Hittite archives, because the Hittite documents are the only ones we have - the origins are lost. We also don't actually have much straight-up narrative myth; there's a lot more ritual description and incantation (sometimes involving bits of myths along the way). But! We can still work with what we've got.

So, for example, there are some rituals that exist at Hattusa in a shorter form in Hurrian (the language of Kizzuwatna), and then in a longer, modified form in Hittite. Our understanding of Hurrian is not awesome, and all of these texts are super broken and incomplete, but stuff has clearly been changed and added and moved around between the two versions. There's also a record of Puduhepa, a Hittite queen who was the daughter of a Kizzuwatnean priest, attempting some syncretism: that is, she states that the Hittite Sun-Goddess, the female head of the pantheon, is the same as the Hurrian head goddess Hebat. She just goes by different names in the different places, says Puduhepa. So here the two traditions are being fully merged.

This is a pretty extreme example, because Kizzuwatna was incorporated into the Empire quite early, and because there was a lot of intermarriage, so the Hurrian traditions/language ended up deeply interwoven with the central Anatolian traditions by the end of the Empire (at least in the upper class). There are other rituals attested at Hattusa - for example, ones with incantations in a language called Palaic - that don't seem to have been modified in the same way? We have Palaic incantations (which we mostly cannot read) bracketed by pretty basic ritual acts (offerings, libations, etc). These seem to have been adopted into the Hittite festival calendar without much modification. But we can't really know that, because we don't have the original rituals from Pala - and further, there could have been a modified Hittite version with translated incantations and we just haven't found it.

A final example is the one single text that we can compare to a native version, which is Gilgamesh! There is a Hittite version of Gilgamesh, and it is SO GREAT: the Hittites skip the whole beginning part at Uruk. They could not give LESS of a shit about Uruk. What do they care about southern Mesopotamian cult cities? NOTHING. But the bit where Gilgamesh and Enkidu come north into Syria to face Huwawa/Humbaba, up near Hittite stomping grounds, gets lots and lots of attention. Such beautiful country! Such impressive cedar trees! They really linger over it and it is fantastic.

2. The PhD-obtaining process was pretty gruelling! as PhDs always are, really. I did a combined MPhil/PhD, and all told it took eight years, which is pretty normal for the field and even kind of speedy for my university. (Though it is still longer than any human being should spend in graduate school.) First two years were coursework and the Master's thesis - I did an edition of a text for my Master's, which is like - you look at all the fragments of your text, including copies if any. (You are looking usually mostly at published drawings of clay tablets, with reference to photos where available; if you and/or your project are big and important you might go to visit some of the fragments in person if possible.) You make a composite transliteration, which is a transcription of the cuneiform into Latin script, where you match up the fragments as best you can and restore gaps based on copies if they exist, and then a translation. Then you write a commentary where you talk about any difficult grammatical stuff and say whatever you have to say about the content. If you're doing graduate work in cuneiform studies - and other kinds of philology too - you gotta learn how to do this and do a good job at it, and it is incredibly painstaking and difficult, woof.

So then! Two more years of coursework! It's a hell of a lot of coursework; most doctorates do not make you take this much. But you have to learn so many, many languages. I did Akkadian, Sumerian, Hittite, Hurrian, Luwian, and then the more minor Anatolian languages (Lydian, Lycian, etc.) which are only very poorly attested and so you just kind of do your best with what's there and move on with your life. I also had to know how to read French (which I came in with) and German (which I came in with a tiny bit of) and Italian (which I did not know) for research purposes, which was extremely necessary - most of the secondary sources for my dissertation were in German. Those three languages had to be done outside of regular coursework. (Also sometimes other languages! One of my favorite grad school stories is when I was taking a class that was just two of us in my advisor's office, doing abovementioned obscure Anatolian languages, and he turned around at the end of class with two hefty printouts in his hands and said, "Do you two read Spanish?" and we were like, "no," and he was like, "Well, you're going to have to! Read this for next time," and handed us each a forty-page article in Spanish. GOOD TIMES.)

Anyway. After coursework came comprehensive exams, which are almost as fun as they sound - ours were four eight-hour tests, to be taken over seven business days, covering what we had learned in class the previous four years. Then I had to prepare a dissertation topic - this was also when my funding was starting to run out, so I had to start working as a TA and writing instructor, and as a copyeditor for a journal published out of our department. So I proposed my dissertation at the end of my fifth year, and then worked and wrote for three years, which: every year of the last three years was more difficult than any that had come before it. But then I finished! And now I am Doctor Frostfire, the end.

So yeah, it was really - it was quite tough. I don't regret doing it, but it would be hard for me to in good conscience recommend that anyone else do it, because it's really not very good for you to do all that. I was certainly in a much, much worse state of physical and mental health at the end than at the beginning. But I am very proud of it; I wrote a really good dissertation, and one of the nice things about such a tiny obscure field is that you can really witness your own impact on it, even while still a graduate student. And! I am now in a position to dispense Hittite facts basically endlessly, because eight years teaches you A LOT. Hooray!

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

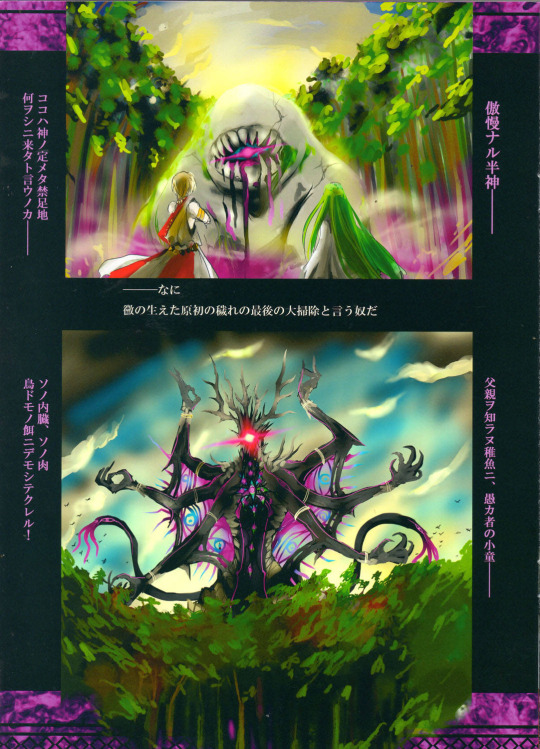

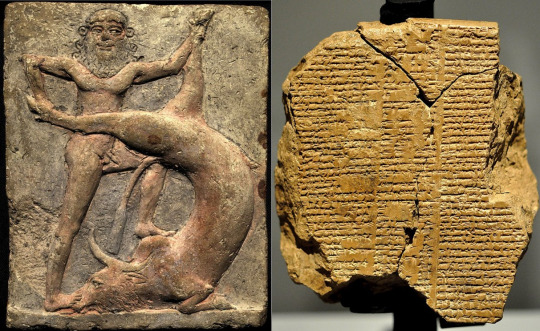

Humbaba [Akkadian/Mesopotamian mythology]

In ancient Akkadian mythology, the pantheon of gods lived in a magical and sacred cedar forest. This mystical place was protected by a mighty creature called Humbaba (Huwawa in the Babylonian version), who was appointed as the forest’s guardian by the deity Enlil. In modern interpretations, the creature is sometimes called an ogre or a demon.

Humbaba was thought to be undefeatable, for not only was he a physically powerful giant, he was also clad in 7 magical radiances (called ‘auras’ in some translations) that protected the fearsome creature. He was a giant, humanlike creature with a strange face that resembled the entrails of a slain animal (which, if I understand it correctly, was a reference to the Mesopotamian practice of ‘reading’ the guts of animals to find omens. In addition, if the entrails happened to resemble the pattern on Humbaba’s face, this was considered a specific omen). His hands ended in dangerous lion-like claws. When Humbaba spoke, his voice was like thunder and his breath was deadly. It was said that his speech was (like) fire, but I’m uncertain whether this was meant to be taken literally.

Georg Burckhardt’s translation of the Gilgamesh epic provides a more detailed physical description: the monster’s head was adorned with bull-like horns, his body was clad in scales, his feet ended in bird-like talons and his penis was a snake. Humbaba also had a tail, which also ended in a snake. To my great annoyance, I have not been able to acquire a copy of this translation so I had to contact someone who did own a copy and ask for the description.

But I’m digressing. As it turned out, even the mighty Humbaba proved no match for the eponymous hero of the Epic of Gilgamesh. After Gilgamesh and Enkidu travelled to the sacred forest to find the creature, Humbaba appeared before them to deny the heroes entry to the sacred forest. He fought fiercely, but the god Shamash commanded the winds themselves to blind Humbaba (as Gilgamesh was favoured by the sun god Shamash). After a long and fierce clash, the monster was defeated. He pleaded and begged for his life, but was slain nonetheless. Gilgamesh and Enkidu then cut down some of the holy cedar trees to make a giant door, with which they adorned the temple of Enlil.

It is also worth noting that effigies/images of Humbaba were used to protect against evil. Also, Humbaba might originally have been derived from the Elamite deity Humban. To my knowledge, this theory remains unproven.

Sources:

George, A., 1999, The Epic of Gilgamesh: The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other texts in Akkadian and Sumerian, Penguin Books, Great Britain, 228 pp.

Burkhardt, G., 1922, Gilgamesh, Brandus, Berlin (secondhand description)

Black, J. and Green, A., 1992, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: an illustrated dictionary, University of Texas Press, 192 pp.

(image source 1: Citrushark on Twitter and Reddit. I had to cut the bottom part of the picture because someone said I shouldn’t post a penis snake. Here is the full image, in all its uncensored Mesopotamian glory)

(image 2: an idol representing the head of Humbaba. Image source: Osama Amin on worldhistory.org)

#Mesopotamian mythology#Akkadian mythology#demons#monsters#humanoid creatures#mythical creatures#myths#mythology

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two-sided .925 sterling silver talisman with the face of Terrible Humbaba on one side, and his epithet in Sumerian cuneiform on the other.

Humbaba / Humwawa is a giant monster made by Utu the sun, and set by the god Enlil to protect the cedar forests where the gods lived. "When he looks at someone, it is the look of death."[Gilgamesh and Huwawa] "Humbaba's roar is a flood, his mouth is death and his breath is fire! He can hear a hundred leagues away any [rustling?] in his forest! Who would go down into his forest!"[Epic of Gilgamesh]

Some texts describe his face as leonine, others say he is more exotically monstrous. My image is based on photographs clay figurines which were carried for protection.

Each piece is hand-made, cast and finished from a mold which I also made. Each piece is unique, with unique variations in texture and finish, including some small defects which are an inevitable part of the process.

#Occult Art#Talismanic Jewelry#Witchcraft#Pagan#Jewelry#Art Jewelry#Jewelry Art#Witch Jewelry#Humbaba#Humbawa#Apotropaic#Sorcerer’s Workbench

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

more huwawa expressions from an expression sheet I found cause I suck at expressions

3 notes

·

View notes