#Contemporary English Version

Text

The Soul who Sins will Die

Just as we will die because of Adam, we will be raised to life because of Christ.

Because I do not have pleasure in the death of a dead person, says THE LORD OF LORDS, but return and live.

— 1 Corinthians 15:21 and Ezekiel 18:32 | Contemporary English Version (CEV) and Aramaic Bible in Plain English (ABPE)

The Holy Bible, Contemporary English Version Copyright © 1995 by American Bible Society and The Aramaic Bible in Plain English 8th edition; Copyright © 2013 All rights reserved.

Cross References: Job 37:23; Isaiah 31:6; Ezekiel 18:23; Ezekiel 33:11; Romans 5:12; Romans 5:17; 1 Timothy 2:4

#Adam#sin#death#Jesus Christ#resurrection#eternal life#God#repent#repentance#return#Lord of Lords#1 Corinthians 15:21#Ezekiel 18:32#Old Testament#New Testament#CEV#Contemporary English Version#Aramaic Bible in Plain English#ABPE#American Bible Society#Holy Bible

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

happy week of tests day 2 today they're gonna make us read and analyse a text from the puritan movement in 17th century unadulterated english fingers crossed i can understand it

#test lasts 6 hours too god..... yesterday was 7h and i actually used 6h55 of that time#i dont understand why they wouldn't give us the contemporary english version of that text so that we may understand something#NOOOOO#pure unadulterated transcription of old manuscripts with missing letters and everything#p

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

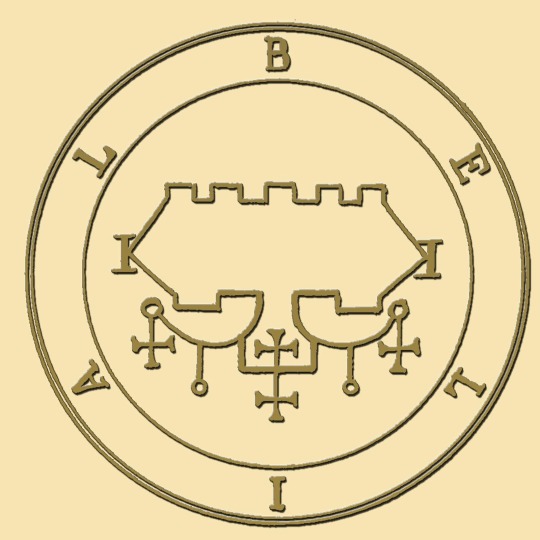

How did magicians back in the day make seals? Was there a science behind it or was it intuitive?

That's a really good question! The answer is extremely complicated!

When most people these days think of seals they think of goetic seals. But the terminology of "seals" actually comes from the idea of sealing a letter. Specifically, it refers to one of the many apocryphal versions of the story of Solomon and Ashmedai, in which king Solomon uses a signet ring with a special magical symbol on it to command demons.

Now, this is one of those biblical stories that people went absolutely nuts for. Jews, Christians, Muslims, damn near every abrahamic faith has their own take on the story, because let's be honest here it's cool as fuck.

But! The original story from the Tanakh doesn't refer to the seal at all, and focuses much more on controlling the sheyd with manacles inscribed with a secret name of God. The inherent magical power of names of God is a common trope in Jewish literature, but later versions of the tale also include greco-egyptian ideas about the inherent magical properties of language, forms, and mathematics.

So when we look at a contemporary English version of a goetic seal, we are looking at something with literally thousands of years of compiled knowledge behind it. I wouldn't necessarily call it science, or intuition, I would describe it as systematic, and narrative. Closer to how campfire stories are improved over generations as people tell and retell them.

Look at this seal of Belial:

The idea of the seal itself? That goes back to Babylonian Jewish ideas about written text having power to control supernatural entities. (Google Babylonian curse bowls if you haven't already.)

See how the letters are spaced? That's important. That goes back to neopythagorean ideas about regular polygons being fundamental building blocks of the universe.

The little crosses? Those are probably cruciforms! That's how you can tell Christians were involved at some point.

See how some of the lines of the seal end in little loops? That goes back to ptolmaic Egyptian ideas about magic. If the crosses are cruciforms, these are probably ankh-forms! You see shapes like that all over magical texts from the 2nd-6th century Mediterranean!

These symbols are the result of dozens of cultures and people and languages collectively yes-anding each other for literally thousands of years. They are DENSE with meaning.

948 notes

·

View notes

Text

Limahl - The NeverEnding Story

1984

"The NeverEnding Story" is the title song from the English version of the 1984 film The NeverEnding Story. It was produced and composed by Italian musician Giorgio Moroder and performed by English pop singer Limahl. He released two versions of the song, one in English and one in French. The English version featured vocals by Beth Andersen, and the French version, "L'Histoire Sans Fin", featured vocals by Ann Calvert.

It was a success in many countries, reaching #1 in both Norway and Sweden, #2 in Austria, West Germany and Italy, #4 in the UK, #6 in Australia and on the US Billboard Adult Contemporary chart.

The song was composed by Giorgio Moroder with lyrics by Keith Forsey, though it (and other electronic pop elements of the soundtrack) is not present in the German version of the film, which features Klaus Doldinger's orchestral score exclusively.

In the final episode of the third season of Stranger Things, set in 1985, "The NeverEnding Story" is sung by Dustin and his long-distance girlfriend Suzie as a way to reconnect after not seeing each other for some time. Following the season's release on July 4, 2019, interest in "The NeverEnding Story" surged; viewership of the original music video had increased by 800% within a few days according to YouTube (not linked to here), while Spotify reported an 825% increase in stream requests for the song.

It recieved a total of 68,2% yes votes!

youtube

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading Tolkien’s annotated translation of Beowulf, and learning all kinds of things about LOTR and the Silm from it!

First:

Leave here your warlike shields [from Beowulf]

[Tolkien’s commentary; bold mine:] Note the prohibition of weapons or accoutrements of battle in the hall. To walk in with spear and shield was like walking in nowadays with your hat on. The basis of these rules was of course fear and prudence among the ever-present dangers of a heroic age, but they were made part of the ritual, of good manners. Compare the prohibition against drawing a sword in the officers’ mess. Swords of course also were dangerous; but they were evidently regarded as part of a knight’s attire, and he would not in any case be willing to lay aside his sword, a thing of great cost and often an heirloom.

This gives me some perspective around Tolkien’s probable intended tone for the moment in Meduseld in The Two Towers where Aragon strongly protests against being told to leave Andúril (a sword of very great value and ancientry, and very much an heirloom) with the door-warden. From a contemporary perspective it’s easy to read it as Aragorn being unnecessarily prideful and combative, but this passage strongly indicates that Tolkien intends it to be Théoden who is being unreasonable in that event, an indication - along with many others in the scene, prior to Gandalf dislodging Saruman’s influence - that Théoden is being discourteous and behaving in a manner unworthy of a king who is recieving heroes offering aid. (The fact of Meduseld being a ‘golden hall’ like famous Heorot in Beowulf may be deliberate to strengthen the parallel.)

Second (immediately following the above commentary):

But against this danger [from swords] very severe laws existed protecting the ‘peace’ of a king’s hall. It was death in Scandanavia to cause a brawl in the king’s hall. Among the laws of the West Saxon king Ine is found: ‘If any man fight in the king’s house, he shall forfeit all his estate, and it shall be for the king to judge whether he be put to death or not.’

This adds context to the incident in the story of Túrin in The Silmarillion where Saeros taunts Túrin in Menegroth and Túrin responds by throwing a heavy drinking-vessel at him and injuring him (it’s indicated the injury is serious, so I’d take it along the lines of him giving him a broken nose and knocking out some teeth.) It is stated in at least some versions of the story that death is the punishment for drawing weapons in the king’s hall, in line with the historical customs mentioned here. This gives a further emphasis that what actually happens - Túrin is not punished at all and Mablung strongly reprimands Saeros for provoking him - illustrates that Túrin is, Saeros’ behaviour notwithstanding, in very high favour in Menegroth. (Saeros as the king’s counsellor is also in roughly the same position as Unferth in Beowulf, who taunts the titular character - Beowulf responds heatedly but without violence. Tolkien may be setting up a deliberate contrast here.)

Third:

The word hádor is an adjective meaning ‘clear, bright’…it is almost always found in reference to the sky (or the sun or stars). But that association is in description of brightness…

This was one a lightbulb moment: oh, in the name of Hador Goldenhead (the ancestor of Húrin, Túrin, and Tuor in The Silmarillion), ‘Goldenhead’ isn’t an additional name/epessë so much as it’s a glossed translation of ‘Hador’! The guy with bright, golden hair.

Fourth: Going back to the Rohirrim - Edoras, the name of their capital city/royal court, is basically just the Old English for ‘courts’:

under was very frequently used in describing position within, or movement to within, a confined space, especially of enclosures or prisons, ‘within four walls’. Cf. in under eoderas (eoderas being the outer fences of the courts), ‘in amid the courts’….‘eoder’ means both ‘fence (protection)’ and ‘fenced enclosure, a court’.

I’m also learning a lot about Beowulf - Tolkien’s notes are clarifying a lot of tone and nuances, not to mention the political/diplomatic relationships between the different kingdoms, which were confusing me - but it’s amazing how much it reveals about ways that Tolkien’s knowledge informed his legendarium!

#tolkien#the silmarillion#the lord of the rings#rohan#aragorn#theoden#turin#hador#edain#beowulf#translation

596 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cross-posting an essay I wrote for my Patreon since the post is free and open to the public.

Hello everyone! I hope you're relaxing as best you can this holiday season. I recently went to see Miyazaki's latest Ghibli movie, The Boy and the Heron, and I had some thoughts about it. If you're into art historical allusions and gently cranky opinions, please enjoy. I've attached a downloadable PDF in the Patreon post if you'd prefer to read it that way. Apologies for the formatting of the endnotes! Patreon's text posting does not allow for superscripts, which means all my notations are in awkward parentheses. Please note that this writing contains some mild spoilers for The Boy and the Heron.

Hayao Miyazaki’s 2023 feature animated film The Boy and the Heron reads as an extended meditation on grief and legacy. The Master of a grand tower seeks a descendant to carry on his maddening duty, balancing toy blocks of magical stone upon which the entire fabric of his little pocket of reality rests. The world’s foundations are frail and fleeting, and can pass away into the cold void of space should he neglect to maintain this task. The Master’s desire to pass the torch undergirds much of the film’s narrative.

(Isle of the Dead. Arnold Böcklin. 1880. Oil on Canvas. Kunstmuseum. Basel, Switzerland.)

Arnold Böcklin, a Swiss Symbolist(1) painter, was born on October 16 in 1827, the same year the Swiss Evangelical Reformed Church bought a plot of land in Florence from the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Leopold II, that had long been used for the burials of Protestants around Florence. It is colloquially known as The English Cemetery, so called because it was the resting place of many Anglophones and Protestants around Tuscany, and Böcklin frequented this cemetery—his workshop was adjacent and his infant daughter Maria was buried there. In 1880, he drew inspiration from the cemetery, a lone plot of Protestant land among a sea of Catholic graveyards, and began to paint what would be the first of six images entitled Isle of the Dead. An oil on canvas piece, it depicts a moody little island mausoleum crowned with a gently swaying grove of cypresses, a type of tree common in European cemeteries and some of which are referred to as arborvitae. A figure on a boat, presumably Charon, ferries a soul toward the island and away from the viewer.

(Photo of The English Cemetery in Florence. Samuli Lintula. 2006.)

The Isle of the Dead paintings varied slightly from version to version, with figures and names added and removed to suit the needs of the time or the commissioner. The painting was glowingly referenced and remained fairly popular throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The painting used to be inescapable in much of European popular culture. Professor Okulicz-Kozaryn, a philologist (someone with a deep interest in the ways language and cultural canons evolve)(2) observed that the painting, like many other works in its time, was itself iterative and became widely reiterated and referenced among its contemporaries. It became something like Romantic kitsch in the eyes of modern art critics, overwrought and excessively Byronic. I imagine Miyazaki might also resent a work of that level of manufactured ubiquity, as Miyazaki famously held Disney animated films in contempt (3). Miyazaki’s films are popularly aspirational to young animators and cartoonists, but gestures at imitation typically fall well short, often reducing Miyazaki’s weighty films to kitschy images of saccharine vibes and a lazy indulgence in a sort of empty magical domestic coziness. Being trapped in a realm of rote sentiment by an uncritical, unthoughtful viewership is its own Isle of Death.

(Still from The Boy and the Heron, 2023. Studio Ghibli.)

The Boy and the Heron follows a familiar narrative arc to many of Miyazaki’s other films: a child must journey through a magical and quietly menacing world in order to rescue their loved ones. This arc is an echo of Satsuki’s journey to find Mei in My Neighbor Totoro (1988) and Chihiro’s journey to rescue her parents Spirited Away (2001). To better understand Miyazaki’s fixation with this particular character journey, it can be instructive to watch Lev Atamanov’s 1957 animated film, The Snow Queen (4)(5), a beautifully realized take on Hans Christian Andersen’s 1844 children’s story (6)(7). Mahito’s journey continues in this tradition, as the boy travels into a painted world to rescue his new stepmother from a mysterious tower.

Throughout the film, Miyazaki visually references Isle of the Dead. Transported to a surreal world, Mahito initially awakens on a little green island with a gated mausoleum crowned with cypress trees. He is accosted by hungry pelicans before being rescued by a fisherwoman named Kiriko. After a day of catching and gutting fish, Mahito wakes up under the fisherwoman’s dining table, surrounded by kokeshi—little wooden dolls—in the shapes of the old women who run Mahito’s family’s rural household. Mahito is told they must not be touched, as the kokeshi are wards set up for his protection. There is a popular urban legend associated with the kokeshi wherein they act as stand-ins for victims of infanticide, though there seems to be very little available writing to support this legend. Still, it’s a neat little trick that Miyazaki pulls, placing a stray reference to a local legend of unverifiable provenance that persists in the popular imagination, like the effect of fairy stories passed on through oral retellings, continually remolded each new iteration.

(Still from The Boy and the Heron, 2023. Studio Ghibli.)

Kiriko’s job in this strange landscape is to catch fish to nourish unborn spirits, the adorable floating warawara, before they can attempt to ascend on a journey into the world of the living. Their journey is thwarted by flocks of supernatural pelicans, who swarm the warawara and devour them. This seems to nod to the association of pelicans with death in mythologies around the world, especially in relationship to children (8). Miyazaki’s pelicans contemplate the passing of their generations as each successive generation seems to regress, their capacity to fulfill their roles steadily diminishing.

(Still from The Boy and the Heron, 2023. Studio Ghibli.)

As Mahito’s adventure continues, we find the landscapes changing away from Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead into more familiar Ghibli territories as we start to see spaces inspired by one of Studio Ghibli’s aesthetic mainstays, Naohisa Inoue and his explorations of the fantasy realms of Iblard. He might be most familiar to Ghibli enthusiasts as the background artists for the more fantastical elements of Whisper of the Heart (1995).

(Naohisa Inoue, for Iblard Jikan, 2007. Studio Ghibli.)

By the time we arrive at the climax of The Boy and the Heron, the fantasy island environment starts to resemble English takes on Italian gardens, the likes of which captivated illustrators and commercial artists of the early 20th century such as Maxfield Parrish. This appears to be a return to one of Böcklin’s later paintings, The Island of Life (1888), a somewhat tongue-in-cheek reaction to the overwhelming presence of Isle of the Dead in his life and career. The Island of Life depicts a little spot of land amid an ocean very like the one on which Isle of the Dead’s somber mausoleum is depicted, except this time the figures are lively and engaged with each other, the vegetation lush and colorful, replete with pink flowers and palm fronds.

(Island of Life. Arnold Böcklin. Oil on canvas. 1888. Kunstmuseum. Basel, Switzerland.)

In 2022, Russia’s State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg acquired the sixth and final Isle of the Dead painting. In the last year of his life, Arnold Böcklin would paint this image in collaboration with his son Carlo Böcklin, himself an artist and an architect. Arnold Böcklin spent three years painting the same image three times over at the site of his infant daughter’s grave, trapped on the Isle of the Dead. By the time of his death in 1901 at age 74, Böcklin would be survived by only five of his fourteen children. That the final Isle of the Dead painting would be a collaboration between father and son seemed a little ironic considering Hayao Miyazaki’s reticence in passing on his own legacy. Like the old Master in The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki finds himself with no true successors.

The Master of the Tower's beautiful islands of painted glass fade into nothing as Mahito, his only worthy descendant, departs to live his own life, fulfilling the thesis of Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 book How Do You Live?, published three years after Carlo Böcklin’s death. In evoking Yoshino and Böcklin’s works, Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron suggests that, like his character the Master, Miyazaki himself must make peace with the notion that he has no heirs to his legacy, and that those whom he wished to follow in his footsteps might be best served by finding their own paths.

(Isle of the Dead. Arnold and Carlo Böcklin. Oil on canvas. 1901. The State Hermitage Museum. Saint Petersburg, Russia.)

INFORMAL ENDNOTES

1 - Symbolists are sort of tough to nail down. They were started as a literary movement to 1 distinguish themselves from the Decadents, but their manifesto was so vague that critics and academics fight about it to this day. The long and the short of it is that the Symbolists made generous use of a lot of metaphorical imagery in their work. They borrow a lot of icons from antiquity, echo the moody aesthetics from the Romantics, maintained an emphasis on figurative imagery more so than the Surrealists, and were only slightly more technically married to the trappings of traditionalist academic painters than Modernists and Impressionists. They're extremely vibes-forward.

2 - Okulicz-Kozaryn, Radosław. Predilection of Modernism for Variations. Ciulionis' Serenity among Different Developments of the Theme of Toteninsel. ACTA Academiae Artium Vilnensis 59. 2010. The article is incredibly cranky and very funny to read in parts. Contains a lot of observations I found to be helpful in placing Isle of the Dead within its context.

3 - "From my perspective, even if they are lightweight in nature, the more popular and common films still must be filled with a purity of emotion. There are few barriers to entry into these films-they will invite anyone in but the barriers to exit must be high and purifying. Films must also not be produced out of idle nervousness or boredom, or be used to recognise, emphasise, or amplify vulgarity. And in that context, I must say that I hate Disney's works. The barrier to both the entry and exit of Disney films is too low and too wide. To me, they show nothing but contempt for the audience." from Miyazaki's own writing in his collection of essays, Starting Point, published in 2014 from VIZ Media.

4 - You can watch the movie here in its original Russian with English closed captions here.

5 If you want to learn more about the making of Atamanoy's The Snow Queen, Animation Obsessive wrote a neat little article about it. It's a good overview, though I have to gently disagree with some of its conclusions about the irony of Miyazaki hating Disney and loving Snow Queen, which draws inspiration from Bambi. Feature film animation as we know it hadonly been around a few decades by 1957, and I find it specious, particularly as a comic artistand author, to see someone conflating an entire form with the character of its content, especially in the relative infancy of the form. But that's just one hot take. The rest of the essay is lovely.

6 - Miyazaki loves this movie. He blurbed it in a Japanese re-release of it in 2007.

7 - Julia Alekseyeva interprets Princess Mononoke as an iteration of Atamanov's The Snow Queen, arguing that San, the wolf princess, is Miyazaki's homage to Atamanoy's little robber girl character.

8 - Hart, George. The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods And Goddesses. Routledge Dictionaries. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Routledge. 2005.

#hayao miyazaki#the boy and the heron#how do you live#arnold böcklin#carlo böcklin#symbolists#symbolism#animation#the snow queen#lev atamanov#naohisa inoue#the endnotes are very very informal aksjlsksakjd#sorry to actual essayists

505 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hamlet’s Age

Not to bring up an age-old debate that doesn’t even matter, but I have been thinking recently how interesting Hamlet’s age is both in-text and as meta-text.

To summarize a whole lot of discussion, we basically only have the following clues as to Hamlet’s age:

Hamlet and Horatio are both college students at Wittenberg. In Early Modern/Late Renaissance Europe, noble boys typically began their university education at 14 and usually completed at their Bachelor’s degree by 18 or 19. However, they may have been studying for their Master’s degrees, which was typically awarded by age 25 at the latest. For reference, contemporary Kit Marlowe was a pretty late bloomer who received a bachelor’s degree at 20 and a master’s degree at 23.

Hamlet is AGGRESSIVELY described as a “youth” by many different characters - I believe more than any other male shakespeare character (other than 16yo Romeo). While usage could vary, Shakespeare tended to use “youth” to mean a man in his late teens/very early 20s (actually, he mostly uses it to describe beardless ‘men’ who are actually crossdressing women - likely literally played by young men in their late teens)

King Hamlet is old enough to be grey-haired, but Queen Gertrude is young enough to have additional children (or so Hamlet strongly implies)

Hamlet talks about plucking out the hairs of his beard, so he is old enough to at least theoretically have a beard

In the folio version, the gravedigger says he became a gravedigger the day of Hamlet’s birth, and that he’s be “sixteene here, man and boy, thirty years.” However, it’s unclear if “sixteene” means “sixteen” or “sexton” (ie has he worked here for 16 years but is 30 years old, or has he been sexton there for thirty years?)

Hamlet knew Yorick as a young child, and the gravedigger says Yorick was buried 23 years ago. However, the first quarto version version of Hamlet says “dozen years” instead of “three and twenty.” This suggests the line changed over time. (Or that the bad quarto sucks - I really need to make that post about it, huh…)

Yorick is a skull, and according to the gravedigger’s expertise, he has thus been dead for at least 7-8 years - implying Hamlet is at least ~15yo if he remembers Yorick from his childhood

One important thing sometimes overlooked - Claudius takes the throne at King Hamlet’s death, not Prince Hamlet. That is mostly a commentary on English and French monarchist politics at the time, but it is strange within the internal text. A thirty year old Hamlet presumably would have become the new monarch, not the married-in uncle (unless Gertrude is the vehicle through which the crown passes a la Mary I/Phillip II - certainly food for thought)

Honestly, Hamlet is SO aggressively described as being very young that I’m fairly confident the in-text intention is to have him be around 18-23yo. Placing his age at 30yo simply does not make much sense in the context of his descriptors, his narrative role, and his status as a university student.

However, it doesn’t really matter what the “right” answer is, because the confusion itself is what makes the gravedigger scene so interesting and metatextual. We can basically assume one of the following, given the folio text:

Hamlet really is meant to be 30yo, and that was supposed to surprise or imply something to the contemporary audience that is now lost to us

Older actors were playing Hamlet by the time the folio was written down, and the gravedigger’s description was an in-text justification of the seeming disconnect between age of actor and description of “youth”

Older actors were playing Hamlet by the time the folio was set down, and the gravedigger’s description was an in-text JOKE making fun of the fact that a 30-something year old is playing a high-school aged boy. This makes sense, as the gravedigger is a clown and Hamlet is a play that constantly pokes fun at its own tropes and breaks the fourth wall for its audience

The gravedigger cannot count or remember how old he is, and that’s the joke (this is the most common modern interpretation whenever the line isn’t otherwise played straight). If the clown was, for example, particularly old, those lines would be very funny

Any way you look at it, I believe something is echoing there. It seems like this is one of the many moments in Hamlet where you catch a glimpse of some contemporary in-joke about theater and theater culture* that we can only try to parse out from limited context 430 years later. And honestly, that’s so interesting and cool.

*(My other favorite example of this is when Hamlet asks Polonius about what it was like to play Julius Caesar in an exchange that pokes fun of Polonius’ actor a little. This is clearly an inside-joke directed at Globe regulars - the actor who played Polonius must have also played Julius Caesar in Shakespeare’s play, and been very well reviewed. Hamlet’s joke about Brutus also implies the actor who played Brutus is one of the main cast in Hamlet - possibly even the prince himself, depending on how the line is read).

#hamlet#hamlet meta#hamlet’s age#this obviously does NOT imply anything about being 30yo btw#any age is a good age to be driven to madness by guilt and grief#It’s just very usual for shakespeare to describe somebody well past their apprentice age as a ‘youth’ SO MUCH#and that makes those lines very interesting#shut up e#willy shakes#posting this while EXHAUSTED going to see a million errors and tone problems tomorrow sorry in advance yall#**very unusual#long post#posting Hamlet meta like it’s 2014 hell yeah

821 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the outset of H. G. Wells's The War of the Worlds (1898), Wells asks his English readers to compare the Martian invasion of Earth with the Europeans' genocidal invasion of the Tasmanians, thus demanding that the colonizers imagine themselves as the colonized, or the about-to-be-colonized. But in Wells this reversal of perspective entails something more, because the analogy rests on the logic prevalent in contemporary anthropology that the indigenous, primitive other's present is the colonizer's own past. Wells's Martians invading England are like Europeans in Tasmania not just because they are arrogant colonialists invading a technologically inferior civilization, but also because, with their hypertrophied brains and prosthetic machines, they are a version of the human race's own future.

The confrontation of humans and Martians is thus a kind of anachronism, an incongruous co-habitation of the same moment by people and artifacts from different times. But this anachronism is the mark of anthropological difference, that is, the way late-nineteenth-century anthropology conceptualized the play of identity and difference between the scientific observer and the anthropological subject-both human, but inhabiting different moments in the history of civilization. As George Stocking puts it in his intellectual history of Victorian anthropology, Victorian anthropologists, while expressing shock at the devastating effects of European contact on the Tasmanians, were able to adopt an apologetic tone about it because they understood the Tasmanians as "living representatives of the early Stone Age," and thus their "extinction was simply a matter of … placing the Tasmanians back into the dead prehistoric world where they belonged" (282-83). The trope of the savage as a remnant of the past unites such authoritative and influential works as Lewis Henry Morgan's Ancient Society (1877), where the kinship structures of contemporaneous American Indians and Polynesian islanders are read as evidence of "our" past, with Sigmund Freud's Totem and Taboo (1913), where the sexual practices of "primitive" societies are interpreted as developmental stages leading to the mature sexuality of the West. Johannes Fabian has argued that the repression or denial of the real contemporaneity of so-called savage cultures with that of Western explorers, colonizers, and settlers is one of the pervasive, foundational assumptions of modern anthropology in general. The way colonialism made space into time gave the globe a geography not just of climates and cultures but of stages of human development that could confront and evaluate one another.

The anachronistic structure of anthropological difference is one of the key features that links emergent science fiction to colonialism. The crucial point is the way it sets into motion a vacillation between fantastic desires and critical estrangement that corresponds to the double-edged effects of the exotic. Robert Stafford, in an excellent essay on "Scientific Exploration and Empire" in the Oxford History of the British Empire, writes that, by the last decades of the century, "absorption in overseas wilderness represented a form of time travel" for the British explorer and, more to the point, for the reading public who seized upon the primitive, abundant, unzoned spaces described in the narratives of exploration as a veritable "fiefdom, calling new worlds into being to redress the balance of the old" (313, 315). Thus when Verne, Wells, and others wrote of voyages underground, under the sea, and into the heavens for the readers of the age of imperialism, the otherworldliness of the colonies provided a new kind of legibility and significance to an ancient plot. Colonial commerce and imperial politics often turned the marvelous voyage into a fantasy of appropriation alluding to real objects and real effects that pervaded and transformed life in the homelands. At the same time, the strange destinations of such voyages now also referred to a centuries-old project of cognitive appropriation, a reading of the exotic other that made possible, and perhaps even necessary, a rereading of oneself.

John Rieder, Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction

671 notes

·

View notes

Text

Literally the whole time I was reading the Temeraire series I was constantly thinking about how history is going to view some of the events, most of which must look absolutely wild from the outside.

And anyway I’ve lately come to the conclusion that despite Laurence’s many, many frustrations with the inaccuracies in the way his contemporaries view events that happen around him, he’s going to have the last word in the end because nobody else is writing shit down.

Like, Laurence is a very good corespondent who writes letters constantly and reports diligently, which is not true of most aviators. And considering how much of the series is just Tem&Co traveling all over the place there’s huge swathes of the story for which Laurence’s reports would be the only English-language primary source. Sipho will almost certainly be the one who writes the interesting, descriptive, polished versions, (the ones people actually want to read 200 years later) but he’ll be writing them years after the fact so Laurence’s reports will be the thing to check everything else against.

Which is going to mean there’s a lot of things that will eventually go down in history accurately despite several major colonial powers wishing it otherwise, but it will also make it hilariously difficult puzzle out anything about Laurence’s temperament etc. because the image of his personality that emerges from his oft-cited extremely dry reports and the image that emerges from every outside source is going to just be wildly different. Which will only increase the likelihood that he’s going to be one of those “ask six historians from six countries about him and you’ll get seven answers” historical figures despite the fact that in the English-speaking world at least he’s one of the people with the greatest control over the historical narrative.

#Laurence in his own reports: the most boring proper man imaginable#makes you question if this guy could have possibly been creative enough to commit treason#Laurence as written about by anyone else: a loose canon and a madman#one who’s single-handedley trying to start multiple revolutions at any given moment#temeraire

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

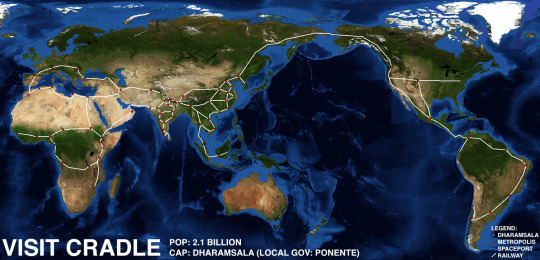

Looking at the time frame of Lancer, it is unlikely that the people of Union speak living languages that look anything like our languages today. Take a look at the oldest writings we have of humanity on Earth, and it's probably closer to us than Union, even at its founding date, let alone five thousand years later. For playing the game, this is irrelevant, unless you want to conlang with your friends. It makes sense to import today's language, mapping today's slang on those people who would use slang in Union. However, place names, which are (mostly, nowadays) independent from languages itself (everyone calls New York some version of New York), are more difficult to justify for some people. To me, it would break my immersion of the names of locations in Union solely reflected contemporary inspirations. At the same time, coming up with nonsensical names is harder and also less inspiring. Therefore, it makes sense that the names of planets and cities on those planets are still informed by English meanings, or old Earth myths and inspirations.

With Cradle, the problem is a bit more difficult, because it is after all the old Earth. There are plenty of towns that have had the same name for thousands of years, but what if a climate apocalypse happens? Aren't most of our oldest cities located on coasts, vulnerable flood plains, or at least reliant on steady agriculture? This is what happens in the Lancer timeline. When Union finally picks up the pieces, they spend more than a thousand years on Earth before they take to the stars. What are they doing?

I like to imagine from the way that Cradle is described, that Union went for a fresh start. Cradle has 2 billion people, but most of the planet is left to nature (and presumably communities living in harmony with nature). 2 billion does not sound like a lot, coming from today's 8 billion, but that was the Earth's population around 1910. Nature had taken a pretty severe beating by then. To avoid a world like our 20th century, I imagine most Terrans live in big metropolises, densely-packed and well-connected. Efficient use of space for living allows for maximum space for both Earth's nature and long human history. Carefully planned cities follow, clustered around the equator where space ports are located, built on top of pre-existing population densities, or close to Massif Vaults, which have likely remained as centres of cultural significance if not population centres outright. Mentioned in the old Field Guide to Harrison Armory is Dharamsala, the cultural capital of Cradle - a city that mostly survived the fall. Struggling with the concept of names, I'll permit the authors at least one name that survived ten thousand years, but I'll leave the rest of the planet unnamed for now.

(original image credit CC BY-SA 4.0 Maulucioni)

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

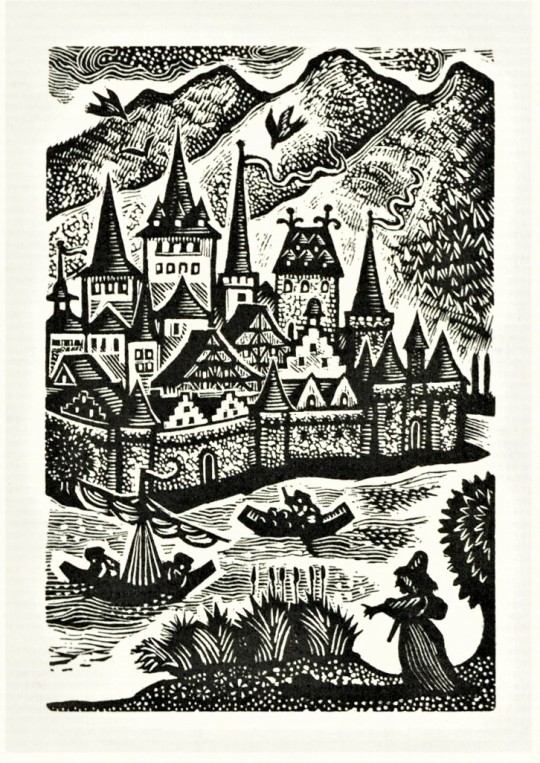

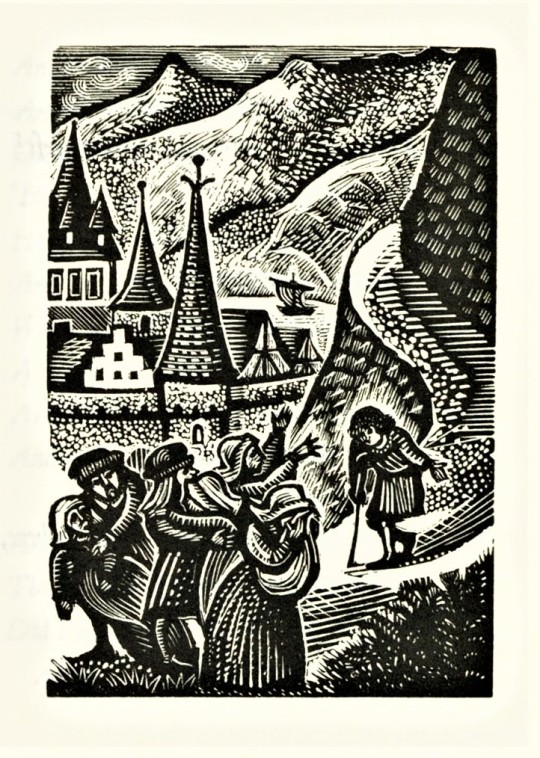

Wood Engraving Wednesday

JOHN LAWRENCE

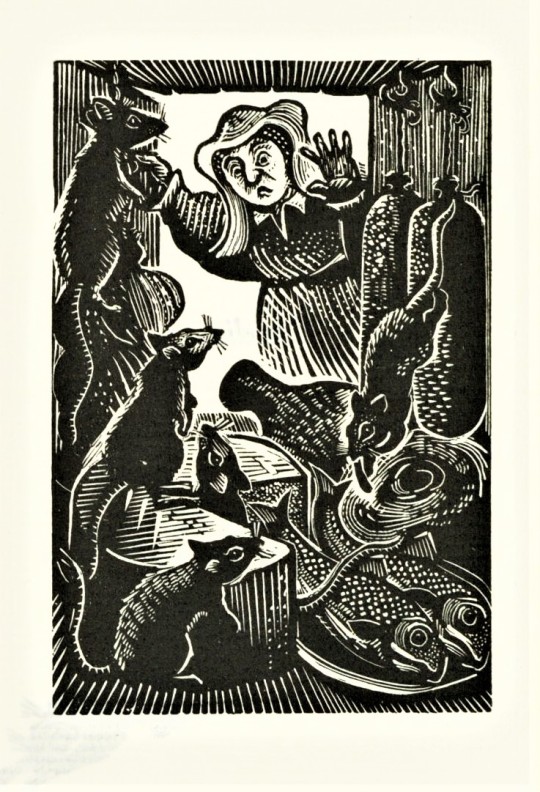

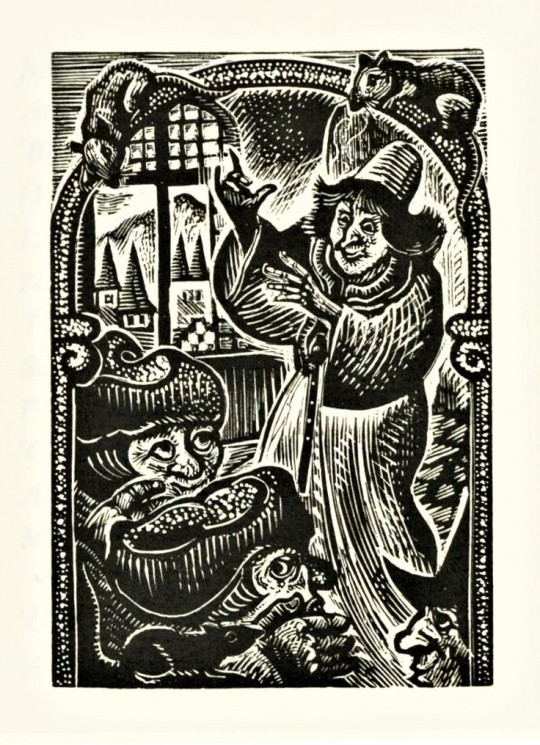

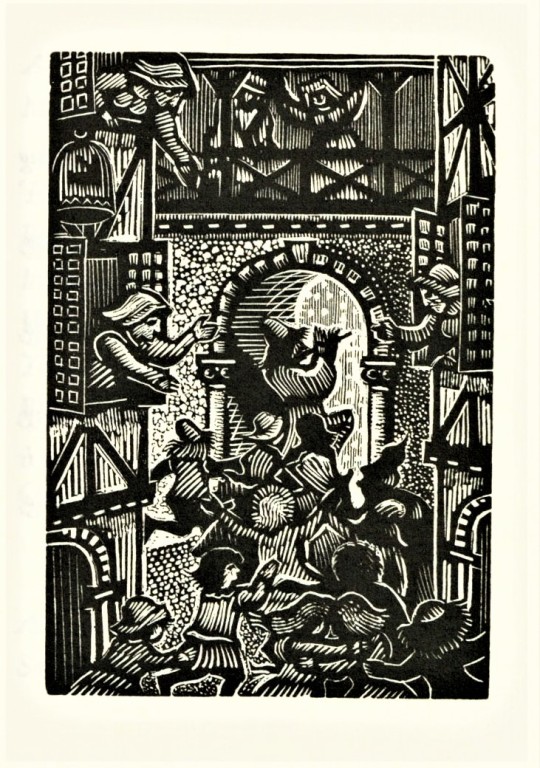

Once again we turn to the fanciful engravings of English illustrator and wood engraver John Lawrence (b. 1933), this time from a small (4.25" x 3") 1992 Folio Society edition of Robert Browning's version of The Pied Piper of Hamelin, printed at The Bath Press in Bath, England on Fabriano Ingres laid paper. The engravings themselves are only 3" x 2", but they are vivid and richly detailed.

John Lawrence, whose career spans nearly 70 years, is one of England's most-respected living wood engravers. He has illustrated well over 200 books and has taught his craft at the Brighton School of Art, Camberwell School of Art, and Cambridge School of Art from the 1960s to 2010. He has influenced generations of noted contemporary wood engravers, and was himself a student of Gertrude Hermes (view some wood engravings by Hermes we have posted).

Our copy of the Folio Society's Pied Piper is yet another donation from the estate of our late friend and colleague Dennis Bayuzick. The book was originally bound in full moire silk by Hunter and Foulis, but our copy was specially rebound in 2001 by English bookbinder Stephen Conway (see below).

View more posts with wood engravings by John Lawrence.

View other illustrations for the Pied Piper by Kate Greenaway and Sarah Chamberlain.

View other books from the collection of Dennis Bayuzick.

View more posts with wood engravings!

#Wood Engraving Wednesday#wood engravings#wood engravers#John Lawrence#Robert Browning#The Pied Piper of Hamelin#Pied Piper of Hamelin#The Folio Society#Folio Society#The Bath Press#Fabriano paper#bookbinding#Stephen Conway#Dennis Bayuzick

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christ Redeemed Us

10 Anyone who tries to please God by obeying the Law is under a curse. The Scriptures say, “Everyone who doesn't obey everything in the Law is under a curse.” 11 No one can please God by obeying the Law. The Scriptures also say, “The people God accepts because of their faith will live.”

— Galatians 3:10-11 | Contemporary English Version (CEV)

The Holy Bible, Contemporary English Version Copyright © 1995 by American Bible Society.

Cross References: Genesis 4:11; Deuteronomy 27:26; Jeremiah 11:3; Habakkuk 2:4; Romans 1:17; Romans 4:15; Galatians 2:16; Hebrews 10:38

#God#faith#Jesus#justice#Redeemer#Galatians 3:10-11#The Epistle of Galatians#New Testament#CEV#Contemporary English Version#Holy Bible#American Bible Society

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

Third shelf, median book

Get Secret Doctrine'd lol.

This is my copy of Mme. Helena Blavatsky's The Secret Doctrine. This particular version is a two-volume 1977 reprint. This is the first of the two volumes.

A cornerstone of western Esotericism. Blavatsky lays out a sweeping, evocative pseudohistory in an attempt to syncretize and unify all human spirituality. Everything from holy texts to archeological evidence to folk tales are treated as evidence of a hidden true religion from which all spirituality branched.

It is difficult to describe the impact this text had on the English speaking world. In 1888, this was many readers first and only exposure to Buddhism and Hinduism. The theory that all religions shared a common "true" ancestor was not a new idea. What made Balavatsky unique was that she had actually been to southeast Asia, and she made clever use of ideas from popular contemporary novels to help sell her ideas. This text was an absolute bombshell for a certain type of guy in 1888.

It's influence on western history is bizarre and --in my opinion-- under-discussed. It's shadow can be seen in everything from authors like Arthur Conan Doyle, and Lovecraft, to painters like Kandinsky and Mondrian, to the early Nazi party.

The text did not spark interest in eastern religion, but it was gasoline for the fire. It set up Theosophy to be an umbrella mythology, which combined several disparate popular myths and ideas into a single, cohesive system.

450 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www.tumblr.com/thebaconsandwichofregret/189924928150/comepraisetheinfanta-thebaconsandwichofregret

whenever i see people rbing the op without the additions i die a little inside so i thought you should have a go at debunking it 🫠

So these are the tweets from the post. I had blissfully not come across it before. This is one of the weirdest takes I have ever seen. It's amazing to see these fashion history takes that are so boldly and confidently wrong and inaccurate.

It's honestly hilariously ignorant to think that a massive cultural and societal shift that took couple of centuries, was all because one guy. It's so reductive and even goes to the great man territory to pick one person to blame for something like this that really had much more broad and complex reasons than "a guy did it". It's stressed in this tread that Beau Brummell was not noble or a gentile and "just some guy", so how would he singlehandedly change the fashions and concept of masculinity of the whole western world? He was a London socialite, it's not like most of his contemporaries in continential Europe knew about him. Like maybe the French, but does anyone really believe people in Eastern-Europe or Nordic countries or in the Mediterranean knew about? Not to mention places like US. Yet everyone dressed like that in his lifetime, so how could his influence reach so far so quickly? Not even kings and queens could so directly and massively shift the fashions. So in the face of it the whole claim is ridiculous, but it's also full of inaccuracies.

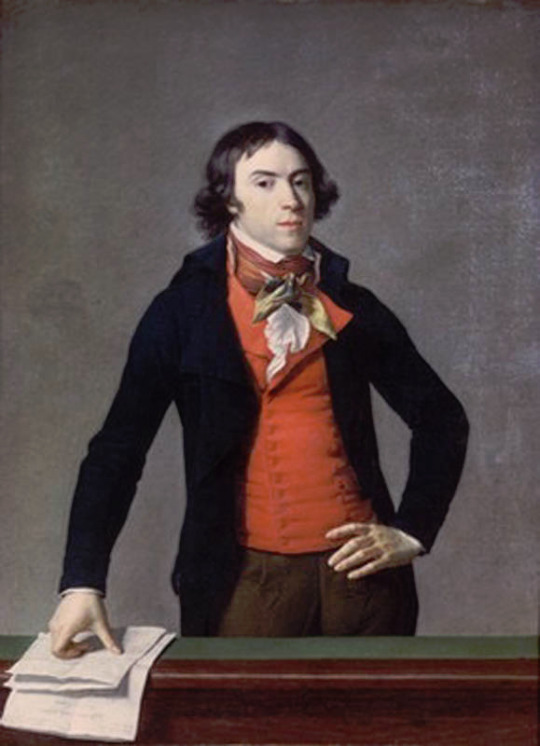

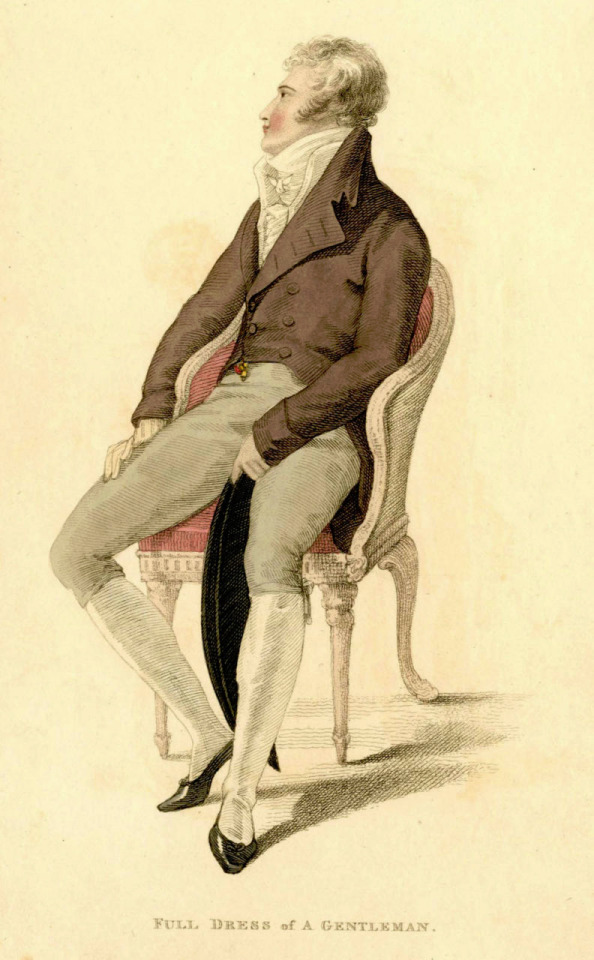

The shift from Rococo fashion to regency fashion was extremely stark and quick in both men and women's fashion, but it happened during 1780s and 1790s, before Beau Brummell became a well known figure in the London society (he was born in 1778 and became well-known in the society after his military career, during which he befriended the Prince of Wales, around the end of 1790s). Here's first an example from 1780s and then from 1793-94 and 1797.

The one from 1780s still has some rococo elements like the wig, but it's already much more toned down and the coat is already turning from frock coat to a tail coat. It's an example of the more casual men's countryside dress from the period. The court dress was still quite elaborate, though also toned down from the 1770s. But there's a big shift when it comes to the examples from 1790s. They are unmistakably Regency fashion. All of these example are French too. I'm sure these people had no idea and gained no influence from an unknown middle class English officer. So what did actually happen? Well, I'm pretty sure the French Revolution in 1789 had a little bigger impact on the European society and fashion than Beau Brummell.

I'm not going to go too deep into this, since I'm working on an in depth post about the masculinity and fashion in the modern era and I go into detail about how the French Revolution had a massive part in shaping them. But the short version is that the French revolutionaries rejected the elaborate fashions of the Rococo French nobility (in both men and women's fashion) as those over the top fashions stood as symbols of the excess wealth of the nobility and the extreme wealth gap between then and the rest of the people. This is also why the high fashion was getting toned down thorough the 1780s before the Revolution. The anger towards the ruling class was mounting at the time and it encouraged the nobility to down down and try to act a little more palatable in their aesthetics to maybe appease the angry people without doing any actual change to address the wealth gap and the centralized power.

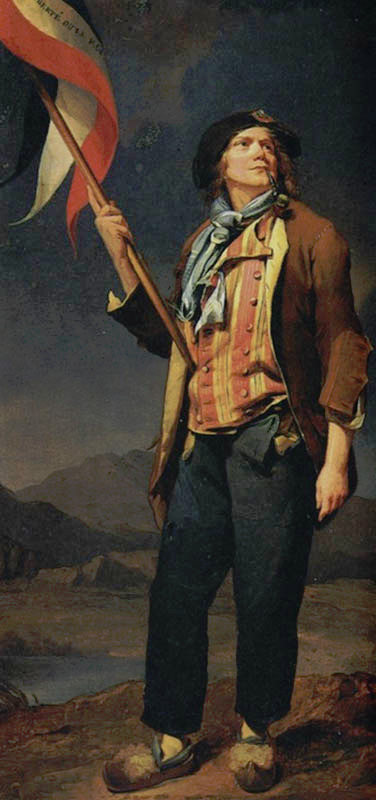

The revolutionaries looked for ideal masculinity and femininity elsewhere then. To contrast themselves against the ruling class, they looked to the antiquity and it's simplicity as well as the peasantry and the country gentleman fashion. Romanticism was the driving force behind the artistic expression of the Revolution. It weaved nationalism to the class struggle that was at the core of the revolutionary movement. So the Revolution was not just the working class and peasantry against the ruling class, but the French People against the nobility. This is when physical labour, militarism, dominance and leadership, really became intrinsically attached to masculinity, as the ideal man of the revolutionaries was a working peasant, who with military power took the the power back to the people from the nobility. The democracy would not last long, but it's not a mistake that only men could vote under the new democracy after the Revolution was won. It's also not a mistake that even when the post-Revolution France eventually abolished slavery (but not without some push-back first and a couple of slave revolts to force their hands) they did not give most people of color rights to vote. Since colonialism whiteness had become intrinsic part of masculinity and femininity, which was part of the dehumanization of everyone else, and the new form of masculinity and femininity born out of the Revolution did not contest that. In fact the Enlightenment philosophy that had laid the ground work for the Revolution and the Romantic movement and it's nationalism that were driving force in it, in no way contested colonialism or it's white supremacy. Which is why the power in the new democracy went to the (mostly) white men.

These elements were in the new men's fashion too. Nationalism, the idealization of militarism and antiquity seen as the origins of democracy made it and especially Antique Rome perfect inspiration for the Revolutionary France. The short hairstyle was inspired from the Roman fashion seen in statues. The fashionable tail coat was influenced by military uniforms and the short jackets of the working class. The long trousers also came from working class dress. Here's examples of the revolutionary fashion from first 1792 and then around 1790.

To be very clear, the revolutionaries were not a single entity with single ideology. They were collection of movements, who were united in their shared desire to overthrow the ruling class and establish some sort of democracy. But inside the movement were much more radical movements than what eventually ended in power after the French nobility. Socialists, abolitionists, feminists, slaves and others also fought for the Revolution and there was a lot of internal struggle too. Romantic movement was also very varied and contained extremely nationalistic elements as well as outright socialist elements.

Beyond the direct and stark effect the French Revolution had in especially France, but everywhere in the western world, the 18th century fashion was never as extreme as in France. If you put the most elaborate French court fashions of mid 1700s and Beau Brummell's style next to each other the difference is certainly massive, but fashion for men as well as women was always much more restrained and somber in England. Here's an English example from 1755-65 and for comparison a French example from 1755.

In fact as the tensions were rising in France the upper class begun to adopt the more toned down English styles. After the Revolution the new Republican styles would spread to Britain too. In Britain though Romanticism had a more pronounced effect as it stayed firmly monarchist. Therefore the English fashion was especially influenced by the styles worn by country side gentlemen.

There's another claim in the thread that fully fails to understand the broad implications of fashion and societal gender and how these things change and evolve. It's the claim that Beau Brummell created the modern men's suit and he's the reason the suit has long trousers. We already went through how long trousers got into men's fashion and it was not him. But the writer is not wrong in saying that Beau Brummell's outfit in this picture is a direct ancestor of modern men's suit. It is.

But you know what else is a direct ancestor of men's suit? This.

The modern three piece suit has it roots as far as in late 17th century. Before suit men wore doublets, which style resembled women's fashion much closer than the suits would after it (as seen in these examples from 1630s). However the distinction between men and women's fashion had started to grow much earlier. A big shift that happened during the 16th century was that men stopped wearing skirts. Men and women wore the same garments for centuries before that. The styles and silhouettes for men and women had some differences (the skirts were often shorter for men for example) but they were parallel to each other. I wrote a whole very long post about how skirts stopped being acceptable for men. In it I write about how the shift in men's fashion was part of the large shift from feudalism to colonialism and capitalism, that needed a new hierarchy to justify the new system after the previous divinely justified feudal hierarchy was no longer an option. The new hierarchy was white supremacist patriarchy and therefore needed a clearer distinction between white men and white woman, that would also help distinct white people from the racialised people.

But such fundamental changes in the societal structure and culture are long processes. The process was continuing in the latter half of the 17th century, when Orientalism first became very popular. Orientalism is the dehumanization and fetishization of Asia and North-Africa, and it was born as the European colonial project was properly getting going in Asia. Colonialism in Asia and North-Africa took a little different form. I suspect it was because it was not that long ago, when Europeans had felt inferior to many of the peoples and empires in Asia and North-Africa, which they had always had much closer relationships with than the rest of Africa and certainly the Americas. I think that's why Orientalism is such a mix of coveting Asian and North-African cultures and bodies in a very fetishistic ways, while also demeaning and diminishing them. Nevertheless, Orientalism had a huge impact on European fashion in late 17th century. Both the way men and women's clothing was made after that to this day was strongly impacted by Orientalism. The coat and waistcoat combination was an adaptation of Turkish fashion. The three piece suit became popular in 1670s and fully took over men's fashion in 1680s (an example from 1687). The cravat was also adopted around the same time to men's wear from a light cavalry mercenary army in the Habsburgian Empire known as the Croats or Cravats. They were mainly Croatian, which to Western European was almost "Oriental" due to their proximity to Asia and Turkey in particular, and therefore the popularization of cravats as a fashion item was also influenced by Orientalism.

The Regency three piece suit also has all the same elements as the suit 150 years earlier, the individual pieces had just evolved into different different cuts. The three piece suit in fact still has the same elements to this day, they have just kept evolving.

My point is not to in any way deny Beau Brummell's influence on Regency fashion. He was the most influential fashion icon for men in his era after all. I hope this just made it very clear that these bigger changes are not about individual people but much larger shifts and movements in society and culture. His actual influence was popularizing some of the English countryside styles mentioned before in the fashionable London society, making extremely elaborate cravats into the fashionable items of the day and becoming the image of the English dandy.

The picture of him above shows him the typical English countryside suit with dark blue tail coat, white cravat and light pantaloons with polished hessian boots. He helped to make the outfit and pantaloons in general fashionable. Breeches would stay as the formal leg wear for some a decade still, till young fashionable men would start to use black or gray pantaloons in formal events too. Pantaloons were very fitted, but the trousers, that were fashionably quite narrow at the time, but looser, really came into the casual fashion in 1810s. As seen before their roots come from the working class fashion that was first popularized in the French Revolution, but they had been very informal and while they were still not quite as formal to be able to use in a formal event, they became acceptable in more casual events. Beau Brummell is credited for inventing or at least popularizing pants that have strap to go under the foot in order to keep them straight. Here's first a painting from of a gentleman in a very country style emphasized by the setting. Then a illustration from 1810 of a full formal dress with breeches and a fashion plate from 1817 of day wear with trousers.

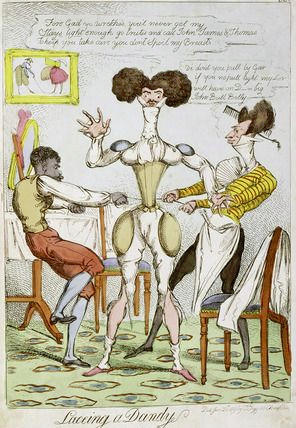

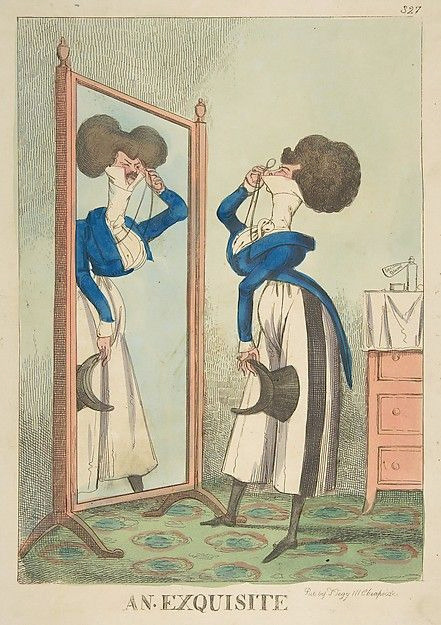

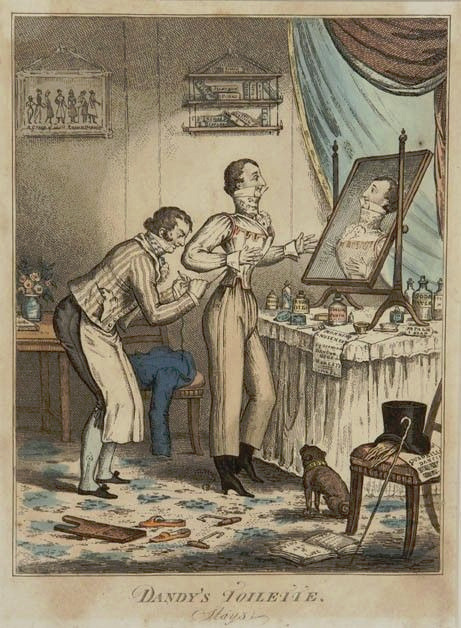

The thread also misses what dandy really was. Dandy was the embodiment of the middle class social mobility of the modern era. He was the "self-made man", the fashionable middle class and the new celebrity of a post-feudal era. He dressed in refined fashionable countryside middle class clothing and was celebrated for his style and refinement, not for his birth. Ironically though, there was a distinct reactionary quality to the Regency dandy. After all dandy did not embody social equality, but mobility. He was the ideal man of the capitalist hierarchy. A bit of dilemma for the dandy was that being extremely fashionable was central to the dandy, but after the French revolution being too fashionable and too concerned about looks had been associated with the aristocracy and was now therefore unmanly. Which is why dandy quickly came to be seen as effeminate. There is a lot of satiric cartoons from the time period that make fun of dandies and their preoccupation with fashion and looks. Here's couple from around 1810s.

In conclusion it's pretty ridiculous to say modern men's fashion was all created by one guy. The real reason why men's formal suit (and to be clear more colorful and elaborate styles have come and gone from men's informal fashion during that time) has been what it is for more than hundred years is because much bigger changes, like capitalism, colonialism, Orientalism and white supremacist patriarchy.

#fashion history#dress history#history#regency fashion#historical fashion#men's historical fashion#18th century fashion#answers#anon

362 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thrawn nation this fanfic needs more attention because it’s mind-blowingly fucking brilliant.

Essentially, Thrawn gets picked up by the corrupt Palpatine-led Republic on a planet in the unknown regions, and says he’s a contemporary artist. The republic is divided by bigotry and xenophobia and corruption and Thrawn makes art and literally starts a revolution. He and Eli make movies too. They live in an apartment. There’s Twitter. They befriend Obi-Wan who is fucking hilarious and Hera is an activist and the OCs are wonderful and it’s just great ok. Thrawn’s history with the Ascendancy is complicated. Palpatine is a terrible guy. Thrawn thinks he can get the best of Palpatine alone and shuts out his friends and becomes the worst version of himself, there’s angst, but it’s done so well. Thrawn’s characterisation is also just amazing.

So yeah sometimes I’ll just be living my life and I’ll remember that someone came up with the best alternate universe fic I’ve ever read in my life.

For context I’m an English major and extremely snobby about writing quality but let me tell you this is insanely good.

Guys I’m just saying this fic is a masterpiece and you’re all sitting on it.

It’s rated E but explicit scenes can be skipped JUST GIVE IT A GO GUYS PLEASE it should literally be top on a03 in the Thrawn tag I don’t even care. Complex and well written AU fics like this never get the attention they deserve and I’m not having it. Pls rb if you’ve read it or just to support fanfic writers idc 💛

#hope the author doesn’t mind me posting this!!!#fanficion#Star Wars#Star Wars fanfiction#thrawn#mitthrawnuruodo#mitth'raw'nuruodo#grand admiral thrawn#eli vanto#thranto#ao3 fanfic#ahsoka series#star wars rebels#thrawn alliances#thrawn trilogy#aralani#thrawn treason#thrawn ascendancy#thrawn fanfiction

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please mind the #wineposting tag. Regardless: are you asking, "Should I watch this adaptation of Les Misérables?" I'll give you advice, though I suspect if you are reading this blog post you have watched all of these anyway (and quite possibly a few more, besides!).

'25 (Fescourt): Probably! If you are a Brick fan none of the adaptation choices will startle you, but having visuals to go with key scenes is a treat. This is a loyal piece. Toulout as Javert, Gabrio as Valjean, Milovanoff as Fantine, and Nivette as Éponine all give excellent performances. Be prepared for a lukewarm Cosette. You might struggle with silent film conventions, length, and French intertitles.

'34 (Bernard): Probably! This is a fairly loyal adaptation of the Brick that makes internally consistent choices where it deviates from its source (sometimes it has goofy continuity errors—politely ignore). Baur as Valjean and Gaël as Cosette give fabulous performances. Moments of silliness do not detract from the quality. Another long haul.

'35 (Boleslawski): Probably not. As an adaptation of Les Misérables this film is bad. That being said, Charles Laughton is a lauded actor, and you can't say he didn't put his whole laughussy into his performance. Because it is accessible and prominent, a lot of LM fans will have seen this film, and you might benefit from shared context if you're in fandom. Speaking personally, I'm glad I saw it, but I'm not sure you will be.

'52 (Milestone): No. Most likely based on '35 rather than on the book, this film is also a bad adaptation of Les Misérables. There are no notable performances. Because it is accessible, this is another adaptation many fans are familiar with, but understanding jokes about Valjean's boyfriend Robert and Javert's sentient hat probably don't justify sitting through the movie.

'58 (Le Chanois): No. Not the English dub, at least. "Bland" is the word of the day. Contemporary French audiences wildly disagree with me per Wikipedia.

'72 (Bluwal): Strong maybe. If you are an intense fan of the Brick, yes. Its use of a narrator to draw from the novel directly and its focus on the Amis makes this adaptation unique on this list. You might not end up liking it but you will have had an experience. If you have zero investment in Les Misérables but are still reading this post for some reason: no, do not watch this.

'78 (Jordan): At some point I will talk about this film and not make a gay joke but today is not that day. If you are not queer, get off my blog, you cis straight, begone. Everyone else: yes, watch this movie, c'mon. Perkins. That performance. At some point I need to make a serious post about queerness and '78 but right now all I've got is Javert's literal on-screen boner. Jesus Christ. Not a great adaptation of the novel but a virtuoso example of unintentional homoeroticism.

'82 (Hossein): No. This is an odd little adaptation without the charisma of a '35 or '78, somehow not as bad as either of those but not as good either. The GIF of the Amis walking in heavy wind is the best this film has to offer.

'98 (August): No—but I stared into my wine glass for a long, long time before typing those two letters. If we are judging adaptations by how they handle the source material, this is a disaster. As a film? I'm sure entertained. I call it bitchslap Les Mis. I should note here I am also a huge fan of Uma Thurman. Possibly I should recuse myself. I don't know, pal. IDK.

2012 (Hooper): I dwell bitterly on the fact that this is our film version of the musical. Brick fans are restless, musical fans are restless. People who first encountered Les Mis via this version are making feral noises. I'm afraid. I'm moving on.

2018 (Davies): It's really unfortunate that I am at my most drunk while commenting on this adaptation. Sure, watch it, it's one of those BBC series that has watchability sheerly because of production value and proximity to contemporary narrative/film expectations/standards. Personally I hate it. My partner is so tired of the tone in which I utter the syllables "Oyelowo".

The Musical: yes c'mon. Bootleg that good bitch.

132 notes

·

View notes