#Koryos

Text

Youth-Warriors of the Indo-European Wolf-Cult

The kóryos is a hypothetical iniatory military fraternity theorised to have existed in Proto-Indo-European society based on traditions found in sundry Indo-European socities, such as the Irish fianna.

This is a largely fictional depiction of a warrior-youth partaking in a kóryos initiation-ritual. Since the kóryos is largely a reconstructed rite, without any written accounts, and scant archaeological evidence, this sketch is a composite based on the imagery of the Kernosovskiy Idol, the Torslunda Plate Beserkr, and the Warrior of Hirshladen.

Another illustration inspired by the kóryos tradition, this time focusing on the possible connection between the cult-fraternities and the origin of the werewolf in pan-European mythology. The kóryos iniation rite is believed to have involved a ritual wherein the youths "died" and were reborn as wolves filled with a warrior frenzy (see: Cú Chulainn, Berserkr). During their summer rangings, these frenzied youths would raid other settlements and engage in theft, murder and rape; all sins commited while "in wolf-shape" were believed to be cast off when a second ritual to excise the warrior frenzy was performed.For example, after the young Cú Chulainn slew the three sons of Necht and was overcome with battle-fury, the household of Conchubar mac Nessa had to literally boil away the boy's rage. One taboo which werewolves are frequently shown transgressing is cannibalism, and the above illustration shows a kóryos member with man-blood still fresh on his lips.

#barbarian#berserker#berserkr#cannibal#celtic#werewolf#indoeuropean#wolfcult#koryos#mannerbund#kóryos#männerbund#boytroop#sonoftheland#torslunda#kernosovskiy#hirshladen

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Call of the Koryos

For what do we work our hands, Down to wretched, arching bones,

When our ancestors did no such thing, But lived by force of arms alone?

For what glory do we toil, So that we might have meagre bread,

When those before us weapons drew, And lived by their iron instead?

Why do we work as chided slaves, Tilling someone else’s land, When not so many years ago,

Our people lived with sword in hand?

-

Is it not glory that you seek?

Not battle for which you yearn?

Do you not want that fire and life,

Once held in your eyes to return?

Well it won’t come with life as this, Only Misery and woe it brings,

For here only monotony, Is fit to reign as tyrant king.

So will you sit and work away,

Until your days of youth are spent?

I for one shall freedom take, Or I shall die in the attempt.

-

Are we not sons of Father Mars?

Does not His blood run through our veins?

To see us hunched in such a state, He surely hangs His head in shame.

I wish to break these scathing bonds, Before my fleeting time elapsed,

I won’t remain a prisoner here, A workhorse caged and beat and trapped.

Will you choose dull and pitter peace, Or thunder of a bloody war?

You are free to choose your fate,

But I will suffer this no more.

- Poetica Atelli, Call of the Koryos

#Koryos#Männerbund#wildermensch#wildermann#wild men#beast men#beastial#primordial#nature#wild nature#poem#poems#manosphere#War#Peace#Glory#Might#beast#battle#fighting#barbarism#savagery

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

Our species is unique in that we are both extremely social, and incredibly diverse in our cultures. The eusocial insects are a match for us in gregariousness, with their colonies of millions, but their social structures are far less multifarious and hew closely to particular prescribed forms species by species. Army ants advance as columns in their millions, fungus-farming ants cultivate their “crops” peacefully, while bees swarm in colonies that split like clockwork upon reaching a predetermined population size. Human societies do not exhibit such fixed regularities and may morph within a single generation, or vary radically on opposite slopes of a mountain. Human culture is marvelously plastic, and it can be adaptive due to intense selection pressure, or simply buffeted by the winds of randomness and whimsy.

But despite the likely role of chance in our social evolution, the shape of human cultural phenomena always rests upon a bedrock of our inherited biology overlaid with environmental influences dictated by place and time. Our societies develop their characteristic outlines at the intersection of fixed eternal instincts and protean social innovations. Despite our cultural diversity, it is little surprise that under similar conditions, we often converge on similar outcomes. As James C. Scott articulates in Against The Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, cereal-based agriculture reliably results in states that control and sequester surplus production, and then use it to support a military or cultural elite. Whether in ancient Mesopotamia, China or Mesoamerica, early cereal-based societies evolved progressively toward tighter social integration and class stratification, as well as achieving an increase in political scale.

Fully-fledged pastoral nomadism emerged far later than sedentary agriculture, and its social and political configuration is markedly different than cereal-based agricultural societies’. As I noted, pastoral nomads are patrilineal and patriarchal, in contrast to sedentary agriculturists who exhibit more variety in the expectations of their gender relations. And notably, nomadic pastoralists put a particular demographic in the driver’s seat: groups of young men shaped, bonded and tempered by their experiences both protecting their tribe’s wealth from enemies and plundering that of others. Collective acts of shocking and transgressive violence were traditionally the fires that kindled into existence these young men’s cohesion and ferocity, and thus the culture that they subsequently shaped. If a thousand platoons bound society together, these cadres of adolescents and young men drove their tribes forward at the literal tip of their spears.

…

Maasai practices may strike some in the industrialized world as strange, but they are eerily redolent of traditions that have been recorded by chroniclers and unearthed by archaeologists from many of our forebear societies across Eurasia. Anyone who has seen the 2007 film 300 knows that Spartan male citizens were initiated into age-sets to harden and train them. Their toughening rites of passage involved activities like being forced to steal food, as well as an autumn ritual where they were given license to kill agricultural slaves, and punished if they couldn’t bring themselves to do so. The Spartans here were clearly replicating the form of the Indo-European koryos.

The koryos were bands of unmarried men who lived on the edge of their communities, just as fledgling Maasai warriors do today. With no possessions or real wealth, these young men raided for much of the year to survive. Formally expelled from respectable society for a period of years, they stole, killed, and committed sexual assault as a matter of course, and their savagery was tolerated, so long as the brutality was directed outward, to victims beyond the community.

The striking ubiquity of the young-warrior tradition among Indo-European peoples (and the similarities of the institution across them) is preserved in disparate mythologies and customs. Warriors of the descendant variants of the koryos often enter into battle nude or without armor, in berserker fury, perhaps inebriated, intoxicated or drugged. The Romans repeatedly describe this phenomenon among the Celtic and Germanic tribes they battled, while Norse berserkers and Indian Vedic youth are known to have entered battle wearing wolf skins. The legend of Norwegian king Harald Fairhair’s wolf-skin-clad warrior bodyguard corps still lives on more than a millennium after his 9th-century reign.

…

The association between the koryos and canids, dogs and wolves, is a recurring motif. Vedic boys were initiated into the koryos by dog-priests, while in ancient Iranian tradition these warriors were described as evil “two-footed dogs.” The Irish Achilles, Cuchulainn, named himself the “hound of Cullen,” while frenzied Scandinavian warriors might wear wolf-skins during their anti-hero’s journey (vividly depicted in the contemporary film The Northman). Meanwhile, in glorious Athens, the ephebos, an institution that trained young men to be soldiers and citizens, was under the patronage of Apollo, who curiously was also associated with wolves in Greek mythology.

…

But the loyal dog, man’s best friend? Here, our intimacy with contemporary domesticated dog breeds risks leading us to a misapprehension of the nomadic context millennia ago; the dogs of that period would be far closer behaviorally to their wolf ancestors. Perhaps here we see the peak fit of the dog/wolf trope to wayward, unrestrained bands of males on the precipice of adulthood. Their potential to coalesce into a powerfully disciplined, loyal and hierarchical pack is undeniable. But until they are fully tamed, trained and their wild impulses fully curbed, they are for all intents and purposes as actual wolves in the midst of society’s hen house. Little wonder then that pastoralist societies conventionally exiled them en masse as far from the center of civilization as possible until that developmental period of peak danger safely passed. Or that they referred to them as dogs and wolves. Often the greatest threat to the stability of society was literally in its midst. Male adolescence was… an inexhaustible reservoir of dogs.

…

It is important to note that the human relationship with dogs long predates pastoralism, as they are the only animal whose domestication occurred during the Pleistocene. Dogs likely began to be associated with our species thousands of years before the peak of the last Ice Age, at least 23,000 years ago. A dog guarding the underworld is a commonplace in pan-Eurasian myth that has persisted over tens of thousands of years. Indeed, it is even present among some North American peoples, who share ancient 25,000-year-old Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) Paleo-Siberian heritage with the ancestors of the Indo-Europeans. The common genetic origins of the human populations 25,000 years ago, along with the domestication of the dog in Northern Eurasia at this time, is strong circumstantial evidence for the shared roots of the similar myths about dogs from the European Atlantic all the way to the heart of North America. In fact, portions of the koryos’ enduring canid mythology might then even date to modern humans’ first settlement of northern Eurasia, nearly 40,000 years ago, when our ancestors first faced off against Siberian wolves.

…

Material evidence reflecting the nature of the early koryos would allow scholars to confirm the insights from these myths, and establish independent sources to add to the credibility of the oral histories. This seems to have happened in 2019, when Dorcas Brown and David Anthony published a paper arguing they had discovered the site of an early koryos initiation. In Late Bronze Age midwinter dog sacrifices and warrior initiations at Krasnosamarskoe, Russia they document a coming-of-age ritual of the Srubna Culture, an ancient Iranian people that occupied the Pontic–Caspian steppe for five centuries after 2000 BC.

…

The ranging of these human “wolf-packs” across Eurasia 5,000 years ago altered the course of history, triggering a cascade of changes that reconfigured the Bronze Age world. To get a sense of the magnitude of this cataclysmic overhaul, perhaps we should consider a well-known example of change and transformation temporally closer to us, in the early historical period. Bryan Ward-Perkins’ The Fall of Rome: And the End of Civilization documents the material realities of the Roman Empire’s collapse in the 4th to 6th centuries AD. Rather than spin out extended textually-based arguments, as historians often do, Ward-Perkins, an archaeologist by training, simply points out that pollution deposits left by industry did not regain Roman levels in British ponds for another 1,400 years. The end of the Roman Empire was not just a political collapse; it was a cultural, economic and social catastrophe, recorded and reflected in the material remains. The term “Dark Age” to describe what followed wasn’t hyperbolic, it was dead honest.

I thought of this when J. P. Mallory told me last year that one reason archaeologists studying early Indo-Europeans in Northern Europe rely almost exclusively upon grave goods in their investigations is that for roughly 1,000 years, that is all the material record offers. Mallory, trained as an archaeologist, had an intuitive feel for this issue that I naturally lacked, and it was at that moment that I realized the collapse of the great European Neolithic societies around 3000 BC was a prehistoric “end of civilization.” And despite the catalytic role likely played by cultural decline and climate change, the appearance of aggressive Indo-European agro-pastoralists was responsible for the ultimate extinction of Europe’s Neolithic civilizations. The post-Neolithic Indo-European Bell Beaker and Corded Ware cultures known to us by their distinctive, but indisputably humble vessels, never constructed anything as grand as what had been wrought by the megalith builders of Western Europe, nor did they craft richly vibrant pottery like the Cucuteni–Trypillia of Eastern Europe had. They were among Stonehenge’s inheritors, not its creators. Likewise, in the Indian subcontinent, the Indo-Aryans would not replicate the material accomplishments of the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) for over a millennium after their arrival around 1800 BC. The IVC at its peak, around 2100 BC, boasted a network of vast cities with public sanitation and hydraulic works that spanned 25% of South Asia. But after its decline and collapse, urbanism only regained its footing in the subcontinent after 500 BC. Like the Anglo-Saxons in post-Roman Britain, the early Indo-Europeans ruled over a fallen world. But their reign of barbarity lasted more than a millennium, rather than the century of Anglo-Saxon darkness.

…

Kristiansen, in short, is presenting a theory that argues the koryos, the ‘black youth’ (black was the color associated with Indo-European koryos across many societies) were instrumental in expanding the range of Indo-European culture through aggressive raiding and eventually conquest. Like the early Romans under Romulus and Remus, they procured mates through means violent and foul. This may have been a general Indo-European trend. Sociolinguist Peggy Mohan argues in Wanderers, Kings and Merchants that the Vedas leave open the possibility that the wives of Indo-Aryan warriors and priests did not themselves speak Sanskrit, but a native Indian language. The expansion and conquests spearheaded by the koryos may have been unplanned, but it’s also easy to see their inevitability in the face of a massive social reorganization triggered by steppe nomadism. Just as water flows downhill, the crystallization of the koryos with the rise of steppe nomadism may have rendered conquest of the supercontinent's rich western and southern flanks by nomads nearly inevitable.

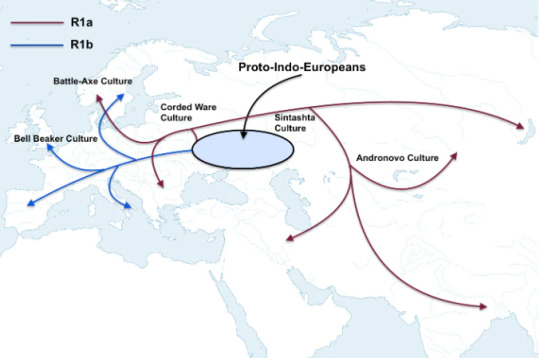

The thesis then is that a migration of males drove the cultural shift is supported by copious genetic evidence. Data from both Europe and India indicate that steppe ancestry was brought by males and that the maternal lineage (mtDNA) of modern Europeans and Indians is predominantly indigenous. More concretely, the expansion of Indo-Europeans is associated with the spread of two paternal lineages, haplogroup R1b and R1a. Haplogroup R1b appears mostly in Central and Western Europe, while haplogroup R1a is today found in Eastern Europe, and across the Indo-Iranian world. The genetic separation between European and Indo-Iranian R1a lineages dates to about 3500 BC, suspiciously close to when the Yamnaya seem to have adopted nomadism.

But perhaps the most striking thing about R1a and R1b is that these lineages found throughout Indo-European-speaking populations are characterized by a massive demographic expansion that occurred so fast the mutations we usually count on to differentiate the branching structure of a phylogeny had no time to accumulate. As you can see below, R1b and R1a exhibit very broad “rake” topologies on a cladogram. The demographic process that drove this was an incredible population explosion of men carrying these Y haplogroups. A 2015 paper comparing genetic diversity between Y chromosomes and mitochondrial (maternal) lineages, found that over 4,000 years ago, for dozens of generations, more than ten women had children for every man in the regions characterized by expansionary Yamnaya. These genetic data make the case for massive levels of de facto polygamy among these early elite Indo-European kindreds.

…

It is our biological legacy as a species that boys in late adolescence, on the cusp of manhood, are prone to impulsive violence and aggression in the course of proving their fitness and establishing their position within their status hierarchy. But bound together in age-set cohorts tasked to range across vast territories as they tended to flocks and defended herds, the koryos tapped into that synergy and cohesion that emerges naturally among bands of young men. They leveraged their newly formed brotherhood toward an explosive outward expansion, enabled by the adoption of nomadism so that their ambitions were born out on a scale never before seen. Separate, they were thin reeds easily snapped, but bundled together, they were deadly and undeniable. Wandering the vast open spaces of Eurasia, the koryos discarded any attachments of family, community or morality and grasped the possibilities of conquest without reservation. From the verdant forests of Western Europe to the pastures of Western Mongolia and the monsoon jungles of India, all was to become their dominion. If the aspiration of a mature society is to inculcate virtue and maintain order, the dream of youth is to be awesome and fearsome.

The evidence from genetics makes it clear that these young men conquered the world for their people, from the Atlantic to the Indian ocean, taking whatever they could grasp without compunction. Myth and language both pointed to the likelihood that the early Indo-European cultures were patrilineal and patriarchal, but genetics and archaeology confirm these facts. The extremely rapid demographic increase of a select few male lineages 4,000 years ago tells us that koryos were not just any members of the community, but the elite, the elect from the families of the warrior caste. From India to Germany, these young wolves established exogamous and patrilocal communities, and just like Comanche Indian braves 4,000 years later, they abducted local women to bear their sons whenever they wished.

…

In the new age after the dark receded, the brutal barbarism wrought by the koryos would be reined in, channeled in the service of the polis, undeniable strength wedded to justice, and the warrior caste, the kshatriya, for example, charged with protecting the weak rather than preying upon them. Impersonal material forces transformed the prehistoric world, unleashing the anti-culture. But after this interregnum of waste and destruction, it was force of mind, it was new ethical religions and philosophies that ultimately banished our terrifying, innate wolf energy back to the periphery of polite society. And from there, it has haunted our dreams and pervaded our myths ever since.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bg3 has neither an Asian nor monk companion so I took matters into my own hands.

Here’s my idea for a companion character. He’s not supposed to be tav/durge but a character you would recruit and have on your party like Gale or Karlach. And yes, he would be romanceable.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how he would fit into the storyline and gameplay. Here’s the notes I have on my phone regarding his companion quest and hypothetical game mechanics:

Upon first recruiting him, he will tell the group he got captured amidst their pilgrimage across Faerun but in actuality Yeon Ryang was searching for their brother, a leading figure in a growing Kara-Turan crime syndicate

Complicated sibling relationship™

Pretty early on you will learn of his keen disliking of Kozakura and its people. Prying further you’ll discover that he was refugeed as a young child due to a particularly violent Kozakuran invasion attempt of Koryo.

Traveling with Yeon Ryang and garnering approval from him will allow you to refer to him as just Ryang. You will also learn that before he was a monk, he was a criminal. A petty thief at first but his sense of entitlement grew alongside the severity of his crimes. It’s a past he holds ever so shamefully and the reason why he blames himself for his brother’s upcomings.

You’ll learn this past after interacting with the Zhentarim and later the Guild which activate unique cutscenes for him. He will strongly disapprove if you earnestly work for these crime groups and approve if you fight against them. If you romance him and help the Zhentarim overthrow the Guild, he will break up you as well, believing the Zhent to be the greater of two evils.

After learning said past, you also learn that Ryang is highkey obsessed of cleansing himself of his past sins and of all sins entirely. Ryang refuses to let go of his shame over himself and part of his companion is quest is helping him get over it for better or for worse. In the end, either he’ll become cynical to his shame and uses it to justify his return to crime or he’ll acknowledge that his shame will always be a part of him that he can only accept it and try to better himself as much as possible.

Romancing him will give you the dialogue option to ask about his missing pinkie fingers in which he’ll explain to you that it was in fact the head monk of his monastery who severed them as a show of reform and discipline to Ryang. Yeon Ryang doesn’t resent his teacher for this and instead sees it as a deserving punishment and reminder.

Later on it’s revealed that his brother, Yeon San who is currently operating under the name Sanjong, is in alliance with the cult of Bhaal and thus the cult of the absolute by supplying them with paralytic poisons from Kara-Tur (the same Dolor uses). He is hoping that when the Absolute takes control over Faerun, that’ll they extend a hand in an assault against Kozakura

If you encounter Sanjong and kill him without Ryang in your party or kill him without talking to Ryang beforehand, you’ll have to pass a dc30 persuasion check to keep Ryang from leaving your party permanently

His companion quest ends with a showdown between him and his brother where you’ll have to fight Sanjong and his goons. Once you bring him to low health or knock him prone, a cutscene occurs where you can convince Ryang to either spare or kill Sanjong. Remaining silent will result in him sparing his brother and leaving the two to repair their relationship

Whether Sanjong is killed or not, the player will have another choice in influencing whether Ryang will either join the ranks of the Kara-turan crime guild or continue pursuing total redemption

Basic rundown: His companion quest centers around the idea of plausibility of change and Yeon Ryang’s feelings of responsibility over his younger sibling. Either you can lead him down the path of rejecting his monastic ways and reverting back to his criminal life (either alongside his brother or replacing him) or you can inspire him to continue traversing across Toril (with or without his brother) to truly realize enlightenment.

#bg3#baldurs gate fanart#bg3 oc#original character#companion oc#companion character bg3#baldur's gate 3#bg3 fanart#bg3 tav#bg3 companion oc#digital art#baldur's gate iii#dnd#dungeons and dragons#koryo#fan character

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

"My son, you came into this world for one reason: revenge."

REVENGE (1988) dir. Yermek Shinarbayev

#revenge#worldcinemaedit#filmgifs#filmauteur#userkino#Yermek Shinarbayev#soviet cinema#kazakh cinema#revenge 1990#revenge 1989#Месть#central asian cinema#ermek shinarbaev#Ermek Bektasuly Shynarbaev#anatoli kim#kazakh new wave#koryo saram#myfilmgallery#ellisgifs#queue

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

They're in Koryo in the title card. It's the same clothes they wore back then.

Aha! Thank you! I knew that dress was familiar but I couldn't place it for the life of me. Thanks for clearing that up!

#Koryo flashback means others as well right???#We've been good! We deserve flashback!#replies#zduhacz#Nick also talks about other things#tsubasa#Vol 206

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

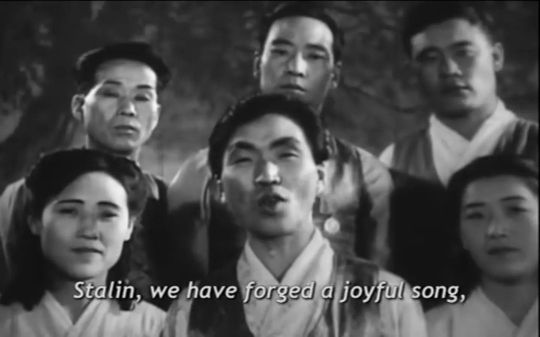

Koryo Saram - Korean Diaspora of the Soviet Union

In the late 1800s thousands of people mostly from Northern Korea went to East Russia to escape famine. Decades later another mass migration from Korea to Russia happened as people fled from Japanese invaders and were attracted by the Bolshevik's promise of free land for peasants. The Korean community thrived in the Soviet Union during the earlier years with many becoming high ranking Communist Party officials, but by 1937 even the family of these high ranking officials would be rounded up and shipped off in cattle trains to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan during Stalin's ethnic deportations. Some people did not survive the harsh conditions of this trip and their corpses would be left unburied at the train stops. Despite all of what they endured in the past, today majority of the Koryo Saram still live in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan where they've kept their traditional Korean customs mixed with the cultures of Central Asians, Russians and other ex-Soviet nationalities.

#Koryo Saram#Korean#Korea#South Korea#North Korea#USSR#Joseph Stalin#Soviet Union#Soviet History#Asia#Central Asia

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

via @olekshyn on Twitter

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

KORYO HOTEL - NORTH KOREA

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

FANTASY KOREA EXISTS IN TORIL?????

#Varksa’s mom and [unnamed fey touched bard] are both from Koryo now#ohhhhh I’m stoked#korean representation in prodominantly western based fantasy…??? YEAAAA#t3xt#SILLA JUST EXISTS??;?? HFJDGHFHH OH MY GOD#wait so does 고구려 why’s 백제 the only one with a weird name#oh my god. the vaguely chinese names. this feels like a fever dream#not the fucking ancient korean japan conflict#ITS ALL (VAGUELY) CHINESE????#hey wotc just because we used Chinese letters doesn’t mean we didn’t have our own WORDS for thing goddamn#ninja…………….#YAKUZA??#Ik Ik it’s bc the class system names need to be consistent but this is so unintentionally hilarious

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it's really funny how in the forgotten realms Faerûn is vaguely European all over with no particular region corresponding to any real part of Europe whereas Kara-Tur has one-to-one fantasy version of every major Eastasian ethnic group

#funnier still sometimes they come up with names like shou for china or kozakura for japan#but then theres fucking#koryo#even worse is the island of bawa#where they speak bavanese#notreblogs#dnd#forgotten realms

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Korean Middle Ages and Unification of the Korean Peninsula

The Korean Middle Ages and Unification of the Korean Peninsula

12th Century Celadon Vase

Episode 26: Korea – The Koryo

Foundations of Eastern Civilization

Dr Craig Benjamin (2013)

Film Review

King Taejo, founder of the Koryo[1] Dynasty (935-1392 AD), attempted to unite the country’s warring nobles by inviting them to serve at court. The fourth Koryo king Kwangjong (925-975 AD) would crush rebellious nobles via the following measures:

Passing the Slave…

View On WordPress

#celadon#feng sui#geomancy#igiong#jurchen#kaeisang#khitan#kongmin#koryo#kwangjong#ming dynasty#mongols#taejo#zen

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Grading In Progress... #koryo #worldtaekwondo #worldtaekwondofederation #taekwondomalaysia (at Kompleks Sukan Komuniti Pulau Penarik) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ck0IH5kB_JV/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

By "stevetranv"

#liminal spaces#liminality#airplane#air travel#2000s#doilies#weirdcore#nostalgia#nostagiacore#retro#vintage#dprk#north korea#air koryo#korea#everyday

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

2018: Japanese blog on Buddhism and Temple Visits

As I brush up on my Japanese I came across these blog entries from the Yasuda Prayer Bead Shop [Japanese language page 安田念珠店] written a few years ago. I used DeepL to do a translation, fiddled and corrected it very slightly and replaced Japanese URL links with English ones — sometimes running a Japanese link through Google Translate.

You may want to skip my boring commentary below and skip…

View On WordPress

#Buddhism#China#Chinese studies#韓國#高麗史#Google Translate#Goryeosa#Japan#Korea#Koryo-sa#Religion#Shinto#sinology#中国

0 notes