#Latin American authors

Photo

A Visit with Alonso Cueto

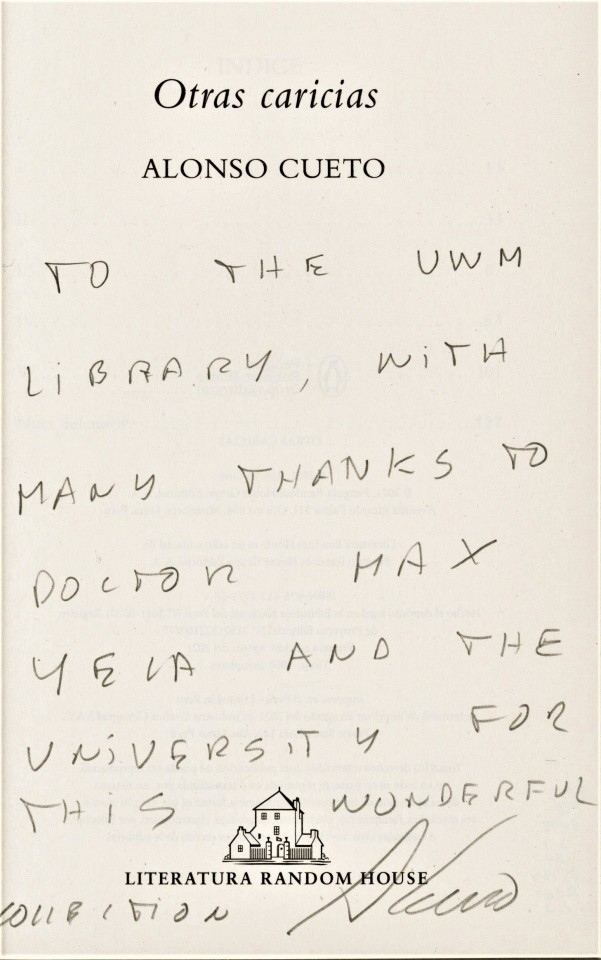

Last week UWM Special Collections co-sponsored a lecture by the internationally-acclaimed, award-winning Peruvian writer Alonso Cueto, who was here to discuss his current writing project on the first Mestiza in South America, Francisca Pizarro, who was also the daughter of Francisco Pizarro, the Spanish conquistador responsible for exploring and subjugating Peru.

The next day, Dr. Cueto made a visit to Special Collections where we spent a bit of time discussing many things, but particularly the writings of Melville and Joyce. He was enraptured by our first and very rare second printings of Moby Dick (the first printing is actually held by our sibling department, the American Geographical Society Library); our John Rodker/Egoist Press second printing of James Joyce’s Ulysses in its original blue paper wrappers and the 1935 Limited Editions Club printing of Ulysses, with original etchings by Henri Matisse, one of only 250 copies signed by both the author and the artist; as well as several incunables.

In return, besides scintillating conversation, Cueto inscribed a copy of his latest published novel to add to our comprehensive collection of signed works by him, Otras caricias (Other Caresses), printed in Peru in 2021 and published in Spanish by Random House, the same publishers of the first American edition of Joyce’s Ulysses in 1934.

Muchas gracias, Alonso, and I hope to spend time with you in Peru one day, mi amigo. Abrazos!

Ver una visita anterior con Alonso Cueto.

-- MAX, Head, Special Collections

#Spotlight#Alonso Cueto#Peruvian writers#South American authors#Latin American authors#Special Collections events

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prank phone calls were known as cachadas and they were as old as the invention of the phone itself. We had a wide array of tactics, all aimed at annoying an unsuspecting interlocutor; pissing them off, riling them up. Somewhere around the middle of high school Chiri and I became experts in the art. We were telephone magicians. But then a sad event forced us to abandon our calling. To this day, the story is a reminder of the evil that resides within us.

We began, like everyone does, as children. When telephones were black, rotary, and state-issued. The first infantile prank calls are always made to someone with the last name Gallo, (no one knows why, but that’s the way it is). In the Mercedes municipal phone book there were nine listings under Gallo, which means rooster in Spanish. We called them one by one.

“Hello, the Gallos?”

“Yes,” they said on the other end.

“Is Remigio there?”

“There’s no Remigio here.”

“Sorry, I guess I have the wrong henhouse,” and we hung up, dying of laughter.

There are dozens of these basic jokes, and we copied our older siblings or cousins, who had already moved on to more elaborate pranks. As you can see, the main objective of our first incursions into the art of the prank call was laughter: a clean cackle that didn’t cause any major harm to the victim.

Oh, if only we could’ve remained in our childhood innocence, free from evil and guilt. But no: we have to mature. And mature we did.

There are always rumors circulating in small towns, facts and details about neighbors who are easy targets for prank calls. Neighbors considered “prickly.” It was generally a certain type of old man who, when he received a prank call, would unleash the full force of his fury and seemed incapable of hanging up the phone. Around age ten or twelve, we got a reliable tip: you have to call Mr. Toledo and say the magic word.

“Hello, is this the Toledo residence?”

“Yes.”

“Is ‘Trumpeter’ there?”

This was the word that triggered Mr. Toledo, who had a high-pitched, strident voice like a horn, to begin his steam of insults and curses, punctuated with hilarious huffs and wild neologisms. Chiri and I would crowd around the receiver and imagine Toledo at his house, in his underwear, his cheeks a deep red color and smoke shooting out of his ears. Ten minutes in, when his diatribe began to lose steam and his lungs to lose air, all we had to say was “don’t get so worked up, Trumpeter,” and he’d start all over again. Mission accomplished.

But a boy must grow, and with him, ambition, dramatic structure, and a still-dormant evil begins to take shape. It wasn’t long before Chiri and I became bored with invisible Gallos and Toledos, who were merely disembodied voices on the other end of the line, so we moved into the realm of three-dimensional pranks, with live victims.

Every afternoon the bald man who ran the shop across the street would close up for the day and head home following hours of total boredom without having sold anything. We could see him, resigned, from the dining room window. Right when the bald guy lowered the heavy metal shutter over his storefront, just before he wrapped the chain around the latch, we called him on the phone. The poor man, who didn’t want to lose a sale, desperately raised the shutter, ran to the back of the shop and, on the fifth or sixth ring, panted: “Pontoni Carpets, good afternoon.”

And we hung up.

A little while later we’d see him once again, humiliated and defeated, lowering his gigantic shutter; it was twice as heavy this time. His life was shit, you could see it in his eyes and in the curve of his spine. Then the bald man once again heard the phone ring inside the shop. “If it’s the same person who called before, they must need carpeting urgently,” the shopkeeper thought, and once again his heart pounded, and once again he raised the shutter, once again he ran to the back of the shop, and once again he said, “Pontoni Carpets, good evening,” with a thread of a voice.

We hung up. We always hung up.

One day we repeated the trick so many times that on the umpteenth fake call the bald man had no other recourse than to say, “Pontoni Carpets, good evening.”

We would’ve gone on like that until the end of time, but a year later we crashed headlong into the future. One day, on the first ring, old bald Pontoni pulled out a brick with an antennae on it and said “Hello.” He’d bought a cordless phone.

Far from deterring us, the advent of technology afforded new opportunities. When we got a second phone at my house (one with a cord, one without) Chiri and I invented something we called telecomedy. This type of prank involved two voices and a passive receptor. It consisted of calling any random number and making the victim believe they were interrupting a private conversation.

VICTIM: “Hello?”

CHIRI (in a woman’s voice): “. . . you like it when I do that.”

VICTIM: “Excuse me?”

HERNÁN (in a man’s voice): “What I like is to lick your ass.”

CHIRI: “Mmmm, don’t say that, you’re getting my nipples all hard.”

VICTIM: “Who is this?”

HERNÁN: “What’s getting hard is my cock,” et cetera.

The objective of this dramatic exercise was to get the interlocutor to stop saying “hello” and start listening to our obscene conversation, like someone hidden underneath a hotel bed. The better our stories, the longer the victim took to get bored and hang up. It was, I suppose, great practice in plotting, which would serve us—in the future—to keep our readers hooked. One day, after ten minutes of telecomedy, one of our victims started panting, and it grossed us out.

By age sixteen or seventeen, we considered ourselves radio theater professionals. We’d learned presence and emotional expression, and had developed a natural reflex for improvisation. Chiri and I skipped our afternoon gym class to shut ourselves up at home with two or three telephones, a little Sanyo recorder, and some props that could make sounds like rain, traffic, fire, or blizzard. We also had egg whites on hand, in case we wanted to change the pitch of our voices.

We didn’t need to talk to each other: we communicated solely through gestures and glances, like radio announcers behind the glass. We worked magic. We could send a stranger down to City Hall to pick up a non-existent tax bill, seduce the receptionist at a doctor’s office, make a firetruck siren sound whenever we felt like it, and convince the owner of the kiosk on the corner of 19th and 30th that he was speaking to us live on-air from a radio station in Luján.

We thought we were gods, and perhaps this hubris is what caused us to fall so quickly from the zenith of our glory and hit rock bottom.

It was the middle of 1988. I remember because we were wearing digital watches to time ourselves. It was dark and my parents weren’t home. For hours, Chiri and I had been playing an enthralling game: make the victim stay on the line as long as possible at all costs. When you become a professional prank caller you go back to the basics. The game consisted of calling a random number and pulling a conversation out of thin air. The clock started at “hello” and ran until the click of the hang up.

That night Chiri had put on a perfect performance: he’d maintained a conversation for seventeen minutes twelve seconds with an old lady, telling her he was calling from the dry cleaner’s. They’d had a hilarious exchange about ironing and drying and ended up singing a duet of “Nostalgias” together. Chiri had the woman wrapped around his little finger, with masterful winks and touches of genius. It would be impossible to outdo him.

I rolled the dice. I got 24612. I dialed the number. Chiri had the stopwatch in his hand and he looked smug. When the voice of an old lady said “Hello” the seconds began to tick away.

I had developed a system—my house brand if you will—that I could pull out at any critical moment. It was a risky strategy that involved using a standard male voice, a monotonous, slow voice, and urging the victim to guess my identity. That night, in what would be the last prank call of my life, I used this technique.

“Who is it?” the old lady asked after my “hello.”

“Oh great,” I said. “You don’t even recognize my voice?”

This was a king’s pawn game. A classic opening. It generated a feeling of familiarity in the other. There’s always some grown nephew whose voice has changed, or a godson. Always.

“I don’t know,” said the old lady. “Who are you trying to call?”

“You, you old bag!”

Super risky move. I was placing the queen in the center of the board. Very few people would call a lady “an old bag.” But if I wanted to beat Chiri’s time, I had to behave like a kamikaze. It worked:

“Daniel?!” she said, in that tone halfway between a question and an exclamation. The tone is called “wishful thinking.”

The way she pronounced that name gave me a million clues. Daniel wasn’t a nephew or a godson, because the old lady’s scream had been deafening. It could be no less than a son. Possibly an only son. And that same piece of evidence led me to another conclusion: the son lived far away and he didn’t call his mother often. I dove in headfirst.

“Of course, Mom! Who else would it be?”

“Danny, little Dan!” the old woman sobbed, as Chiri silently took an imaginary hat off of his head, surrendering to my move.

Now, time was on my side. I paced around with the cordless so that Chiri couldn’t try to make me laugh. He sat listening in on the regular phone. After five minutes I’d learned that Daniel lived in the South (“is it cold down there?” the old lady asked in the middle of September), and also that in recent years the relationship between them hadn’t been very warm.

“Dad would’ve liked you to be at his funeral.”

“It’s not easy, Mom. There are open wounds, life isn’t that simple.”

I learned that Daniel had a wife—Negra—and two kids. The youngest, Carlitos, had never met his grandmother. I also learned that the city Daniel lived in was Comodoro Rivadavia, and that he worked in a television factory. At twelve minutes into the conversation, when I was on track to beat Chiri’s record, the old lady began to suspect something was up. She started asking ambiguous questions, I had to improvise.

“How is it that you sound so close, son?” she wanted to know.

She left me with no choice. “Mom,” I said, surprised by my cruelty. “I’m here, at the station.”

Silence from the other end of the line, and then a muffled sob. I turned around and made eye contact with Chiri, who was staring at me, his face pale. He wasn’t smiling. I felt, from deep inside, the pull of evil. I felt it for the first time in my life. It came from my stomach, my cock, and my brain all at the same time, like a diabolical holy trinity. With a gesture, I asked Chiri how long I’d been talking. Sixteen minutes.

“Don’t cry, Ma,” I said.

“Have you come to Mercedes before?” she asked in a broken voice. “Sometimes I dream that you come, at night, and you don’t stop by the house . . .”

“No. No, no . . . It’s the first time I’ve been back, I swear. But I didn’t want to just show up, out of nowhere. That’s why I called.”

“Son!” she shouted, heartbroken. “Hang up and hurry over, come home!”

Almost seventeen minutes, I needed something else. I clenched my left fist as I decided what to say. I think the evil had taken full control of me by that point. I don’t think I was even the one speaking. Something indefinable, the thing that makes us human and horrible, was now rooted deep within me and I was its puppet.

“I have to do a few things first, then I’ll come home,” I said. “Listen, Mom. Will you make cannelloni? I’m starving.”

“Of course, Danny.”

“I miss your cannelloni.”

“Hurry up, I’ll make them now.”

“Bye.”

“Bye, son. I’m trembling all over, hurry up.”

And the woman hung up the phone.

I looked at Chiri, who was staring down at the floor. He refused to make eye contact, I guess he couldn’t look me in the face. He didn’t remember to stop the clock, so we never even found out who won. We sat on the couch for a while, not saying a word. Half an hour later we knew that somewhere in Mercedes there was a house, and in that house there was a table, and on that table sat a steaming dish.

And we knew that our childhood would be over the moment Daniel’s cannelloni grew cold.

- Cannelloni by Hernán Casciari. 19 april, 2007

#short story#literature#latin american literature#latin american authors#cannelloni#canelones#argentina#argentine literature#hernan casciari#coming of age#family drama#prank calls#pranks#fiction

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

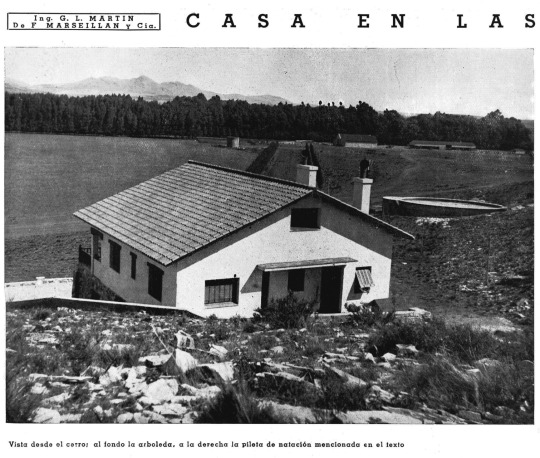

Hoy les voy a presentar a un estudio que realizó muchísima obra en la PBA, solo superado en número por Francisco Salamone. Se trata del estudio bahiense Francisco Marseillán SRL.

Hace unas semanas les conté cómo en el marco de la ley 4017, numerosos municipios tuvieron vía libre del Gobierno para renovar su infraestructura pública contratando a profesionales independientes. Si bien este plan se ejecutó con más fuerza entre 1936-1940, cuando FM y cía ya estaban instalados en CABA, el estudio trabajó desde mediados de los 1920s en territorio bonaerense.

🧑🏻🎓Ahora bien, quién fue Marseillán? Aunque nació en Coronel Dorrego en 1894, fue educado en Francia, Bahía Blanca, la UBA y Estados Unidos, donde el ingeniero se especializó en pavimentos y caminos.

👷🏻Ya de regreso en Bahía, fue director de Obras Particulares, y en 1923 fundó Francisco Marseillán y cía. asociado al Ingenerio Segundo Fernández Long. El estudio estaba dividido en varias secciones: obras, arquitectura, agrimensura, obras sanitarias, administración de propiedades, venta de materiales y administración.

El Departamento de Arquitectura estuvo a cargo del Ingeniero platense Guillermo Martín, responsable de la mayoría de los edificios que iremos viendo. En las oficinas trabajaban unos 50 empleados, llegando a emplear hasta 2000 obreros en los proyectos.

Aunque algunas obras fueron asignadas a Salamone durante años (municipalidades de Mar Chiquita, Urdampilleta o Pirovano), en general el estudio no realizó proyectos tan llamativos. No obstante, merecen su lugar dentro del patrimonio arquitectónico al ser pioneros en el ingreso de la PBA a la modernidad.

Manejaron un amplio repertorio de estilos, pasando por el neoclásico, el art decó, el racionalismo y el neo colonial, entre otros.

Curiosamente, Marseillán falleció el 2 de marzo de 1959, apenas unos meses antes que Francisco Salamone.

Dato de color: FM estudió y escribió algunos libros dedicados al ciencismo, una disciplina que estudiaba cómo obtener el máximo rendimiento a la capacidad de trabajo del hombre.

Fuentes: El rotariano argentino. Rotary club Buenos Aires.

Gobernación Fresco: Plan de Obras Públicas Municipales (1936-40). El “Estudio del Ingeniero Civil Francisco Marseillán srl.” René Longoni.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Science Fiction From Latin America, With Zombie Dissidents and Aliens in the Amazon

A new wave of writers is making the genre its own, rooting it in local homelands and histories.

By Emily Hart

A spaceship lands near a small town in the Amazon, leaving the local government to manage an alien invasion. Dissidents who disappeared during a military dictatorship return years later as zombies. Bodies suddenly begin to fuse upon physical contact, forcing Colombians to navigate newly dangerous salsa bars and FARC guerrillas who have merged with tropical birds.

Across Latin America, shelves labeled “ciencia ficción,” or science fiction, have long been filled with translations of H.P. Lovecraft, Ray Bradbury, William Gibson and H.G. Wells. Now they might have to compete with a new wave of Latin American writers who are making the genre their own, rerooting it in their homelands and histories. Shrugging off rolling cornfields and New York skylines, they set their stories against the dense Amazon, craggy Andean mountainscapes and unmistakably Latin American urban sprawl.

The avalanche of original science fiction is timely, arriving as many readers and writers in Latin America feel choked by the folksy tropes of magical realism and desensitized by realist depictions of the region’s struggles with violence.

READ MORE

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m still not sure what happened, but Thirsty, the first book in my friend Mia Hopkins’s Eastside Brewery trilogy, went out of print a couple of years ago. I kept trying to recommend it because it’s steamy and sexy and gritty and working class, and the characters get a happy ending even if one of them is a reformed gang member trying to stay out of prison.

Guess what — it’s back! And now I can recommend it again!

#romance recs#contemporary romance#Latine romance#inclusive romance#diverse books#diverse reads#latinx romance#asian american author#filipina american author

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Selva Almada

youtube

Selva Almada was born in 1973 in Villa Elisa, Argentina. Almada is regarded as one of the most powerful voices in contemporary Argentine and Latin American literature. Her first novel The Wind That Lays Waste was nominated for Argentinian Book of the Year upon its publication in 2012. In 2019, when it was published in English, it won the Edinburgh International Book Festival's First Book Award. Almada has been compared to William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, and Flannery O'Connor. She has been a finalist for the Tigre Juan Award, the Rodolfo Walsh Award, shortlisted for the Vargas Llosa Prize for Novels, and longlisted for the International Booker Prize. Almada's work has been translated into several languages, including Portuguese, French, Turkish, Swedish, and Italian.

#writers#woman writers#authors#books#argentina#latin america#latin american literature#latina#hispanic#south america#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I finally started reading "Cien Años de Soledad" by Gabriel García Márquez, a book that I have been meaning to read for a few years now. And I need to read more books by Latin American authors in Spanish because, although Spanish is my first language, I sometimes sound like a "no sabo” kid to other native Spanish speakers.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

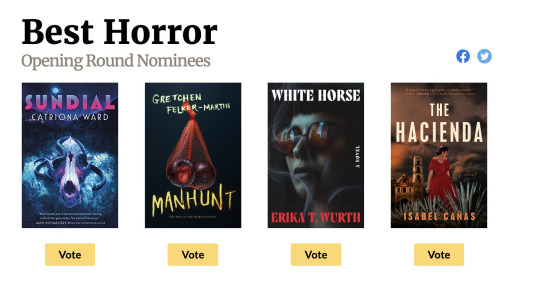

THE HACIENDA is up for TWO Goodreads Choice Awards!

I am absolutely thrilled to announce that THE HACIENDA is up for a Goodreads Choice Award in two categories, Horror and Debut Novel!! 😭 If you have a Goodreads account, I would be honored if you cast a vote for your friendly neighborhood hot priest 🕯️

(Especially in the Horror category.)

#goodreads#horror books#Gothic books#Mexican Gothic#witchcraft#hot priest#writeblr#writers of tumblr#authors of color#BIPOC books#bipoc horror#creative writing#Rebecca#latin american culture#mexican books#mexican author#writing advice

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

#unite against book bans#american library association#ownvoices#book recs#diverse books#queer books#queer authors#poc authors#black authors#latine authors#trans authors#protect queer kids#protect trans kids

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i can acutely feel the thrum between my temples and the ache of my fingers picked apart. my eyes carry the weight of my affliction, my mouth trembling and serving as a lock and key.

the ache in all of my muscles renders me almost lifeless but does not commit to killing my anxieties, my torments, or my shame.

#my jottings#writing#writeblr#latina#latine#chicana#mexicana#mexican american#latine author#chicana writer#bipoc writers#original poem#creative writing#heartbreak

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been slapped in the face by hubris. I’m gonna read Honduras in Spanish. And Nicaragua too

#Nicaragua is poetry so doable#Honduras is a novel AND I have an English option that I could go for but#since I pussied out of Costa Rica and am trying to order the German translation…. 😂#I gotta make up for it#and Honduras seems readable for my Spanish level#which is a small miracle man the Latin American authors all speak in riddles! 😂#shut up Sam

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jorge Luis Borges was ‘the most British of Latin America’s writers’

Argentina’s most famous author holds great attraction for British writers, scientists, artists and filmmakers – no surprise given his family history and command of both the Spanish and English written word.

Borges with his mother on Westminster Bridge, London

by Pablo San Roman

"Jorge Luis Borges is probably the most British of Latin American writers," says Cynthia Stephens, author of the book The Borges Enigma. Mirrors, Doubles, and Intimate Puzzles, summing up how experts on Spanish-language literature in the United Kingdom feel about the legendary Argentine author.

Borges’ links with the United Kingdom and Anglo-Saxon literature were predictable, given that he learned Spanish and English at the same time through speaking with his paternal grandmother, Frances Anne Haslam, born in the Midland county of Staffordshire.

"Apart from eminent literary figures in the United Kingdom, scientists, artists and filmmakers have been attracted by the complexity of the Borges fictional universe," points out Stephens, a member of the Association of Hispanists of Great Britain and Ireland.

READ MORE

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goodreads recommended books for hispanic heritage months is so funny because it's really easy to tell when a book was written by a latin american and when one was written by a usamerican with latin american heritage.

Like. The children of immigrants always seem to use words and names in spanish mixed with english to make it known that they are latines. Like the hacienda, hello mi amor or whatever. The books whole appeal are about them being hispanic

Meanwhile latin american authors get translated and they give no hint of any heritage in the title until you read their name. Because for them the experience of being latin american is not the main part of the plot, but the background

No shade. It's just interesting how there's this whole market that uses the "exotism" of being latin american in the us that romanticizes an idea that is often very different from the reality

#personally i find the whole thing kind of ridiculous#some of these authors romantizice the whole 'latin experience' when they have lived in the us their whole lives#and have no idea what it is like to live in latam#like yeah i get that their experiences are different from white usamericans#but its also not the same as being actually latin american#latam

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

a couple years ago I was dismayed to realize that I had a piss poor competency at recognizing and understanding metaphor, and started working on trying to improve that. Jump to the present where now I am sitting in white knuckled furious frustration because now I am picking up on metaphor pretty well but have only become more aware that almost nobody else is, no matter how blunt they are.

#Tender is the Flesh is driving me insane because it is such a straightforward blunt metaphor#Hey imagine a future where society responded to a meat shortage by imprisoning and slaughtering humans for consumption#And this structure is upheld by comprehensively dehumanizing them in a variety of ways#Most prominent among them simply being language#And how this is used to uphold structural brutality for the benefit of privileged classes#The author says this explicitly in every Latin American press interview I've found#But in the English speaking press almost every review is just like Wow!!!!! Fucked up story about how eating meat is wrong#A story about dehumanization? Surely this means nothing about human society and the people being slaughtered and treated like animals#Should be read as literally being animals rather than people who are being dehumanized

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

#books#literature#book recommendations#quotes#literature quotes#classics#classic literature#latin american literature#gabriel garcía márquez#one hundred years of solitude#reading#novels#magical realism#fiction#booklr#colombian authors#this was a strange book ngl

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

booktubers: trying to reinvent magical realism into "curio fantasy"

latinos:

#bookblr#can we stop. trying to separate these influences from their post colonial Latin American roots pls and thank.#latino authors have continued stories with magical realism into modern day#and now we have people trying to micro trend it into 'curio fantasy' bleh.#boils my piss

5 notes

·

View notes