#augustus freeman IV

Photo

Black History Month (2023)

February 1st marks the start of Black History Month. It's my hope to show reverence, love, and appreciation for the Black Community in my own way, which, as usual, is by drawing DC characters. There are many more I would've liked to have added (and maybe that will be a project for next year), but these felt like the essential characters to feature (through that DC lense); historical firsts, groundbreaking, both lore and culturally significant characters.

Anyway, if I can recommend some Black History-centric DC material, John Ridley's (12 Years a Slave, Let it Fall) Other Side of the DC Universe miniseries really is fantastic. For interested parties who would like to further research these characters and learn more about them, I'll list them below, top to bottom, left to right:

Rocket, Icon, Mr. Terrific, Amanda Waller, Cyborg, Steel, Vixen, Mal Duncan (sometimes Herald, sometimes Manhattan Guardian), Bumblebee, Black Lightning, Green Lantern (John Stewart)

#black history month#dc#green lantern#milestone comics#cyborg#raquel ervin#icon#augustus freeman IV#mr terrific#waller#amanda waller#victor stone#rocket#michael holt#justice league#justice society#jsa#doom patrol#teen titans#young justice#herald#manhattan guardian#mal duncan#bumblebee#karen beecher#dc superhero girls#black lightning#jefferson pierce#john stewart#dcau

255 notes

·

View notes

Text

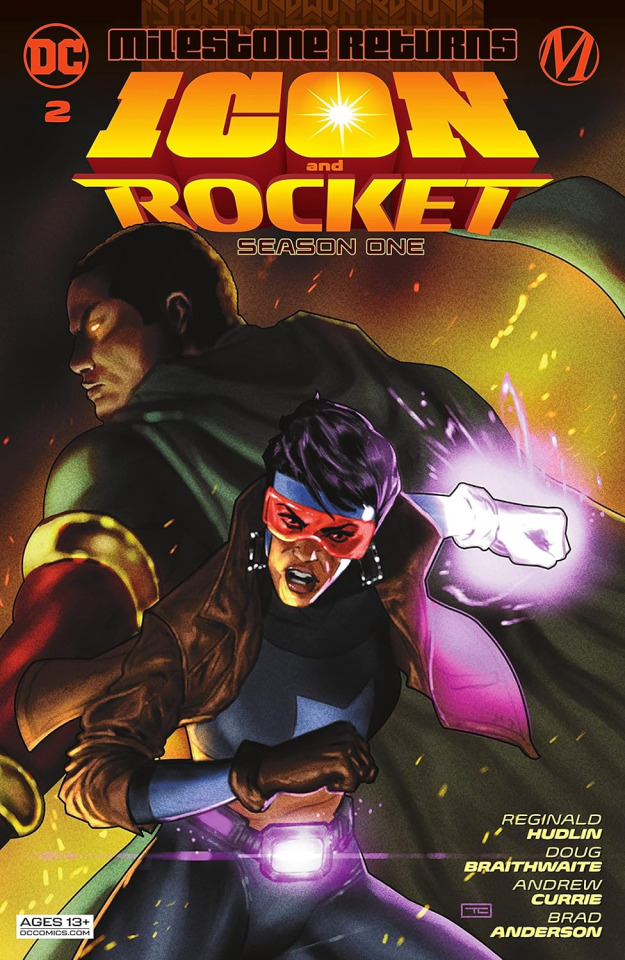

#icon & rocket: season one#icon & rocket#raquel ervin#rocket#arnus#augustus freeman iv#icon#reginald hudlin#milestone comics#dc milestone#dc comics#poll

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Watch the American Climate Leadership Awards 2024 now: https://youtu.be/bWiW4Rp8vF0?feature=shared

The American Climate Leadership Awards 2024 broadcast recording is now available on ecoAmerica's YouTube channel for viewers to be inspired by active climate leaders. Watch to find out which finalist received the $50,000 grand prize! Hosted by Vanessa Hauc and featuring Bill McKibben and Katharine Hayhoe!

#ACLA24#ACLA24Leaders#youtube#youtube video#climate leaders#climate solutions#climate action#climate and environment#climate#climate change#climate and health#climate blog#climate justice#climate news#weather and climate#environmental news#environment#environmental awareness#environment and health#environmental#environmental issues#environmental justice#environment protection#environmental health#Youtube

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Characters I’d love to see in the DCEU now that James Gunn has taken the helm.

#10

Icon/Arnus (Alien Name) or Augustus Freeman IV (Human Name) is an alien from Terminus, the Cooperative who in the 1800s landed in a cotton field in the American South and became enslaved, years later he appeared under his human alias and the appearance of a black man who secretly had superpowers, when his house was broken into he used his powers and a person named Raquel Ervin who was a witness of the home invasion convinced Augustus to become Icon, with her becoming his sidekick Rocket, a native to the Dakotaverse before being in the main DC Universe, he has teamed up with the Justice League and is noted as being like Superman in terms of power

#dc comcis#dceu#dakotaverse#augustus freeman iv#arnus#icon#icon dc#rocket#rocket dc#raquel ervin#james gunn#dc#milestone comics

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rocket and Icon

Raquel Ervin heard stories about Augustus Freeman growing up. How he was the fourth man in a row with that, sharing it with his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather. How, despite that, Gus seemed to have no other relatives save his great-great grandmother, Miriam, and grandmother, Estelle. There were other details: Gus was unusual, a recluse; voted Republican, fairly wealthy, a sort of odd local icon.

Of course, while most of this was true, Raquel would find out--during an ill-advised break-in during the night of the “Big Bang”--that something was more true than the rest of it. Augustus was an alien, Arnus from Terminus, altered by his own technology to take human form. Almost two hundred years old, he briefly participated in Diana’s Society during the Golden Age, but would settle for what he felt were less ostentatious, invasive methods of helping others.

As the Big Bang spread throughout the city and left Dakota City with a metahuman population boom unseen since the Dominator Gene Bomb was dropped, Raquel took Arnus’s story and spun it into something new: a new hero, a new chance, and a new world of possibility.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Icon #1 (May 1993) by Milestone / DC Comics

Written by Dwayne McDuffie, drawn Mark Bright and Mike Gustovich.

#Icon#Milestone Comics#Milestone#DC Comics#Dwayne McDuffie#1993#Vintage Comics#Etsy#Mark Bright#Mike Gustovich#Rocket#Augustus Freeman IV#Comic Books#Comics

1 note

·

View note

Photo

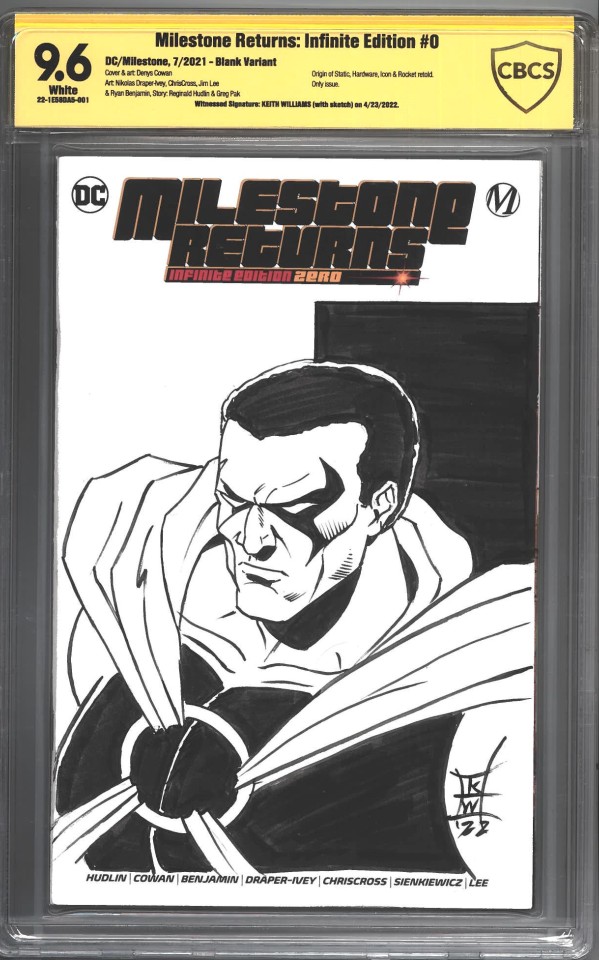

My commission of Icon sketch cover by Keith Williams

#Keith Williams#art commission#sketch cover#sketch cover a#DC Comics sketch cover#Milestone Comics sketch cover#CBCS#Icon#Augustus Freeman IV#Arnus#Milestone#The Cooperative#Terminus#Justice League#JL#Underground Railroad#Union Army#Shadow Cabinet#Milestone Comics#DC Comics#Milestone art#DC Comics art#comic art#comic book art#comics#comic books#superhero#superhero art#comic superhero#comic hero

1 note

·

View note

Text

Today we talk about an alien man named Arnus who was turned into a baby and raised on Earth as Augustus Freeman, and a human woman named Raquel Ervin who saw his powers and convinced him to become the superhero called Icon, with her as his sidekick Rocket.

0 notes

Photo

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History of Greece are neither manageable nor necessary for any but regular scholars of the original authorities. But there are sections of his work of peculiar value and well within the scope of the general reader. These are: the account of the Athenian democracy (vol. iv. ch. 31); of the Athenian empire (vol. v. ch. 45); the famous chapters on Socrates and the Sophists (vol. viii. ch. 67, 68), and the account of Alexander’s expedition (vol. xii.). For the general description of Greece, Curtius is unrivalled, and in many things he is a valuable corrective of Grote’s pedantic radicalism. But it is a serious drawback to Curtius as a historian that with his purist Hellenic sympathies he treats the history of Greece as closed by Philip of Macedon, whereas in one sense it may be said that the history of a nation then only begins. The histories of Greece too often end with the death of Demosthenes, or the death of Alexander, though Freeman and Mahaffy have shown that neither the intellect nor the energy of the Greek race was at all exhausted. The German work of Holm, pronounced by Mahaffy to be amongst the very best, will soon be open to the English reader.

The historians of Rome, with two exceptions, are too diffuse, or too fragmentary: such mere epitomes or such uncritical compilations, that they have no such value for the general reader as the great historians of Greece. Yet there are few more memorable pages in history than are some of the best bits from the delightful story-teller Livy. We cannot trust his authority; he has no pretence to critical judgment or the philosophic mind. He is no painter of character; nor does he ever hold us spellbound with a profound thought, or a monumental phrase private tours istanbul.

But his splendid vivacity and pictorial colour, the epic fulness and continuity of his vast composition, the glowing patriotism and martial enthusiasm of his majestic theme, impress the imagination with peculiar force. It is a prose AEneid — the epic of the Roman commonwealth from AEneas to Augustus. It is inspired with all the patriotic fire of Virgil and with more than Horatian delight in the simple virtues of the olden time. For the first time a great writer devoted a long life to record the continuous growth of his nation over a period of eight centuries, in order to do honour to his country’s career and to teach lessons of heroism to a feebler generation. Had we the whole of this stupendous work, we should perhaps more fully respect the originality as well as the grandeur of this truly Roman conception.

The loss of the 107 books

One of the abiding sorrows of literature is the loss of the 107 books, out of the 142 which composed the entire series. They were complete down to the seventh century: now we have to be content with the ‘epitomes,’ or general table of contents. But 35 books, a little short of one quarter of the whole, have reached us. In these times of special research and critical purism, the merits of Livy are forgotten in the mass of his glaring defects. Uncritical he is, uninquiring even, nay, almost ostentatiously indifferent to exact fact or chronological reality.

He seems deliberately to choose the most picturesque form of each narrative without any regard to its truth; nay, he is too idle to consult the authentic records within reach. But we are carried away by the enthusiasm and stately eloquence of his famous Preface: we forgive him the mythical account of the foundation of Rome for the beauty and heroic simplicity of the primitive legends, and the immortal pictures of the early heroes, kings, chiefs, and dictators. Where the facts of history are impossible to discover, it is something to have epic tales which have moved all later ages. And we may more surely trust his narrative of the Punic wars, which is one of the most fascinating episodes in the roll of the Muse of History.

0 notes

Photo

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History of Greece are neither manageable nor necessary for any but regular scholars of the original authorities. But there are sections of his work of peculiar value and well within the scope of the general reader. These are: the account of the Athenian democracy (vol. iv. ch. 31); of the Athenian empire (vol. v. ch. 45); the famous chapters on Socrates and the Sophists (vol. viii. ch. 67, 68), and the account of Alexander’s expedition (vol. xii.). For the general description of Greece, Curtius is unrivalled, and in many things he is a valuable corrective of Grote’s pedantic radicalism. But it is a serious drawback to Curtius as a historian that with his purist Hellenic sympathies he treats the history of Greece as closed by Philip of Macedon, whereas in one sense it may be said that the history of a nation then only begins. The histories of Greece too often end with the death of Demosthenes, or the death of Alexander, though Freeman and Mahaffy have shown that neither the intellect nor the energy of the Greek race was at all exhausted. The German work of Holm, pronounced by Mahaffy to be amongst the very best, will soon be open to the English reader.

The historians of Rome, with two exceptions, are too diffuse, or too fragmentary: such mere epitomes or such uncritical compilations, that they have no such value for the general reader as the great historians of Greece. Yet there are few more memorable pages in history than are some of the best bits from the delightful story-teller Livy. We cannot trust his authority; he has no pretence to critical judgment or the philosophic mind. He is no painter of character; nor does he ever hold us spellbound with a profound thought, or a monumental phrase private tours istanbul.

But his splendid vivacity and pictorial colour, the epic fulness and continuity of his vast composition, the glowing patriotism and martial enthusiasm of his majestic theme, impress the imagination with peculiar force. It is a prose AEneid — the epic of the Roman commonwealth from AEneas to Augustus. It is inspired with all the patriotic fire of Virgil and with more than Horatian delight in the simple virtues of the olden time. For the first time a great writer devoted a long life to record the continuous growth of his nation over a period of eight centuries, in order to do honour to his country’s career and to teach lessons of heroism to a feebler generation. Had we the whole of this stupendous work, we should perhaps more fully respect the originality as well as the grandeur of this truly Roman conception.

The loss of the 107 books

One of the abiding sorrows of literature is the loss of the 107 books, out of the 142 which composed the entire series. They were complete down to the seventh century: now we have to be content with the ‘epitomes,’ or general table of contents. But 35 books, a little short of one quarter of the whole, have reached us. In these times of special research and critical purism, the merits of Livy are forgotten in the mass of his glaring defects. Uncritical he is, uninquiring even, nay, almost ostentatiously indifferent to exact fact or chronological reality.

He seems deliberately to choose the most picturesque form of each narrative without any regard to its truth; nay, he is too idle to consult the authentic records within reach. But we are carried away by the enthusiasm and stately eloquence of his famous Preface: we forgive him the mythical account of the foundation of Rome for the beauty and heroic simplicity of the primitive legends, and the immortal pictures of the early heroes, kings, chiefs, and dictators. Where the facts of history are impossible to discover, it is something to have epic tales which have moved all later ages. And we may more surely trust his narrative of the Punic wars, which is one of the most fascinating episodes in the roll of the Muse of History.

0 notes

Photo

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History of Greece are neither manageable nor necessary for any but regular scholars of the original authorities. But there are sections of his work of peculiar value and well within the scope of the general reader. These are: the account of the Athenian democracy (vol. iv. ch. 31); of the Athenian empire (vol. v. ch. 45); the famous chapters on Socrates and the Sophists (vol. viii. ch. 67, 68), and the account of Alexander’s expedition (vol. xii.). For the general description of Greece, Curtius is unrivalled, and in many things he is a valuable corrective of Grote’s pedantic radicalism. But it is a serious drawback to Curtius as a historian that with his purist Hellenic sympathies he treats the history of Greece as closed by Philip of Macedon, whereas in one sense it may be said that the history of a nation then only begins. The histories of Greece too often end with the death of Demosthenes, or the death of Alexander, though Freeman and Mahaffy have shown that neither the intellect nor the energy of the Greek race was at all exhausted. The German work of Holm, pronounced by Mahaffy to be amongst the very best, will soon be open to the English reader.

The historians of Rome, with two exceptions, are too diffuse, or too fragmentary: such mere epitomes or such uncritical compilations, that they have no such value for the general reader as the great historians of Greece. Yet there are few more memorable pages in history than are some of the best bits from the delightful story-teller Livy. We cannot trust his authority; he has no pretence to critical judgment or the philosophic mind. He is no painter of character; nor does he ever hold us spellbound with a profound thought, or a monumental phrase private tours istanbul.

But his splendid vivacity and pictorial colour, the epic fulness and continuity of his vast composition, the glowing patriotism and martial enthusiasm of his majestic theme, impress the imagination with peculiar force. It is a prose AEneid — the epic of the Roman commonwealth from AEneas to Augustus. It is inspired with all the patriotic fire of Virgil and with more than Horatian delight in the simple virtues of the olden time. For the first time a great writer devoted a long life to record the continuous growth of his nation over a period of eight centuries, in order to do honour to his country’s career and to teach lessons of heroism to a feebler generation. Had we the whole of this stupendous work, we should perhaps more fully respect the originality as well as the grandeur of this truly Roman conception.

The loss of the 107 books

One of the abiding sorrows of literature is the loss of the 107 books, out of the 142 which composed the entire series. They were complete down to the seventh century: now we have to be content with the ‘epitomes,’ or general table of contents. But 35 books, a little short of one quarter of the whole, have reached us. In these times of special research and critical purism, the merits of Livy are forgotten in the mass of his glaring defects. Uncritical he is, uninquiring even, nay, almost ostentatiously indifferent to exact fact or chronological reality.

He seems deliberately to choose the most picturesque form of each narrative without any regard to its truth; nay, he is too idle to consult the authentic records within reach. But we are carried away by the enthusiasm and stately eloquence of his famous Preface: we forgive him the mythical account of the foundation of Rome for the beauty and heroic simplicity of the primitive legends, and the immortal pictures of the early heroes, kings, chiefs, and dictators. Where the facts of history are impossible to discover, it is something to have epic tales which have moved all later ages. And we may more surely trust his narrative of the Punic wars, which is one of the most fascinating episodes in the roll of the Muse of History.

0 notes

Photo

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History of Greece are neither manageable nor necessary for any but regular scholars of the original authorities. But there are sections of his work of peculiar value and well within the scope of the general reader. These are: the account of the Athenian democracy (vol. iv. ch. 31); of the Athenian empire (vol. v. ch. 45); the famous chapters on Socrates and the Sophists (vol. viii. ch. 67, 68), and the account of Alexander’s expedition (vol. xii.). For the general description of Greece, Curtius is unrivalled, and in many things he is a valuable corrective of Grote’s pedantic radicalism. But it is a serious drawback to Curtius as a historian that with his purist Hellenic sympathies he treats the history of Greece as closed by Philip of Macedon, whereas in one sense it may be said that the history of a nation then only begins. The histories of Greece too often end with the death of Demosthenes, or the death of Alexander, though Freeman and Mahaffy have shown that neither the intellect nor the energy of the Greek race was at all exhausted. The German work of Holm, pronounced by Mahaffy to be amongst the very best, will soon be open to the English reader.

The historians of Rome, with two exceptions, are too diffuse, or too fragmentary: such mere epitomes or such uncritical compilations, that they have no such value for the general reader as the great historians of Greece. Yet there are few more memorable pages in history than are some of the best bits from the delightful story-teller Livy. We cannot trust his authority; he has no pretence to critical judgment or the philosophic mind. He is no painter of character; nor does he ever hold us spellbound with a profound thought, or a monumental phrase private tours istanbul.

But his splendid vivacity and pictorial colour, the epic fulness and continuity of his vast composition, the glowing patriotism and martial enthusiasm of his majestic theme, impress the imagination with peculiar force. It is a prose AEneid — the epic of the Roman commonwealth from AEneas to Augustus. It is inspired with all the patriotic fire of Virgil and with more than Horatian delight in the simple virtues of the olden time. For the first time a great writer devoted a long life to record the continuous growth of his nation over a period of eight centuries, in order to do honour to his country’s career and to teach lessons of heroism to a feebler generation. Had we the whole of this stupendous work, we should perhaps more fully respect the originality as well as the grandeur of this truly Roman conception.

The loss of the 107 books

One of the abiding sorrows of literature is the loss of the 107 books, out of the 142 which composed the entire series. They were complete down to the seventh century: now we have to be content with the ‘epitomes,’ or general table of contents. But 35 books, a little short of one quarter of the whole, have reached us. In these times of special research and critical purism, the merits of Livy are forgotten in the mass of his glaring defects. Uncritical he is, uninquiring even, nay, almost ostentatiously indifferent to exact fact or chronological reality.

He seems deliberately to choose the most picturesque form of each narrative without any regard to its truth; nay, he is too idle to consult the authentic records within reach. But we are carried away by the enthusiasm and stately eloquence of his famous Preface: we forgive him the mythical account of the foundation of Rome for the beauty and heroic simplicity of the primitive legends, and the immortal pictures of the early heroes, kings, chiefs, and dictators. Where the facts of history are impossible to discover, it is something to have epic tales which have moved all later ages. And we may more surely trust his narrative of the Punic wars, which is one of the most fascinating episodes in the roll of the Muse of History.

0 notes

Text

youtube

Watch the American Climate Leadership Awards 2024 now: https://youtu.be/bWiW4Rp8vF0?feature=shared

The American Climate Leadership Awards 2024 broadcast recording is now available on ecoAmerica's YouTube channel for viewers to be inspired by active climate leaders. Watch to find out which finalist received the $50,000 grand prize! Hosted by Vanessa Hauc and featuring Bill McKibben and Katharine Hayhoe!

#ACLA24#ACLA24Leaders#youtube#youtube video#climate leaders#climate solutions#climate action#climate and environment#climate#climate change#climate and health#climate blog#climate justice#climate news#weather and climate#environmental news#environment#environmental awareness#environment and health#environmental#environmental issues#environmental justice#environment protection#environmental health#Youtube

7K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History of Greece are neither manageable nor necessary for any but regular scholars of the original authorities. But there are sections of his work of peculiar value and well within the scope of the general reader. These are: the account of the Athenian democracy (vol. iv. ch. 31); of the Athenian empire (vol. v. ch. 45); the famous chapters on Socrates and the Sophists (vol. viii. ch. 67, 68), and the account of Alexander’s expedition (vol. xii.). For the general description of Greece, Curtius is unrivalled, and in many things he is a valuable corrective of Grote’s pedantic radicalism. But it is a serious drawback to Curtius as a historian that with his purist Hellenic sympathies he treats the history of Greece as closed by Philip of Macedon, whereas in one sense it may be said that the history of a nation then only begins. The histories of Greece too often end with the death of Demosthenes, or the death of Alexander, though Freeman and Mahaffy have shown that neither the intellect nor the energy of the Greek race was at all exhausted. The German work of Holm, pronounced by Mahaffy to be amongst the very best, will soon be open to the English reader.

The historians of Rome, with two exceptions, are too diffuse, or too fragmentary: such mere epitomes or such uncritical compilations, that they have no such value for the general reader as the great historians of Greece. Yet there are few more memorable pages in history than are some of the best bits from the delightful story-teller Livy. We cannot trust his authority; he has no pretence to critical judgment or the philosophic mind. He is no painter of character; nor does he ever hold us spellbound with a profound thought, or a monumental phrase private tours istanbul.

But his splendid vivacity and pictorial colour, the epic fulness and continuity of his vast composition, the glowing patriotism and martial enthusiasm of his majestic theme, impress the imagination with peculiar force. It is a prose AEneid — the epic of the Roman commonwealth from AEneas to Augustus. It is inspired with all the patriotic fire of Virgil and with more than Horatian delight in the simple virtues of the olden time. For the first time a great writer devoted a long life to record the continuous growth of his nation over a period of eight centuries, in order to do honour to his country’s career and to teach lessons of heroism to a feebler generation. Had we the whole of this stupendous work, we should perhaps more fully respect the originality as well as the grandeur of this truly Roman conception.

The loss of the 107 books

One of the abiding sorrows of literature is the loss of the 107 books, out of the 142 which composed the entire series. They were complete down to the seventh century: now we have to be content with the ‘epitomes,’ or general table of contents. But 35 books, a little short of one quarter of the whole, have reached us. In these times of special research and critical purism, the merits of Livy are forgotten in the mass of his glaring defects. Uncritical he is, uninquiring even, nay, almost ostentatiously indifferent to exact fact or chronological reality.

He seems deliberately to choose the most picturesque form of each narrative without any regard to its truth; nay, he is too idle to consult the authentic records within reach. But we are carried away by the enthusiasm and stately eloquence of his famous Preface: we forgive him the mythical account of the foundation of Rome for the beauty and heroic simplicity of the primitive legends, and the immortal pictures of the early heroes, kings, chiefs, and dictators. Where the facts of history are impossible to discover, it is something to have epic tales which have moved all later ages. And we may more surely trust his narrative of the Punic wars, which is one of the most fascinating episodes in the roll of the Muse of History.

0 notes

Photo

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History of Greece are neither manageable nor necessary for any but regular scholars of the original authorities. But there are sections of his work of peculiar value and well within the scope of the general reader. These are: the account of the Athenian democracy (vol. iv. ch. 31); of the Athenian empire (vol. v. ch. 45); the famous chapters on Socrates and the Sophists (vol. viii. ch. 67, 68), and the account of Alexander’s expedition (vol. xii.). For the general description of Greece, Curtius is unrivalled, and in many things he is a valuable corrective of Grote’s pedantic radicalism. But it is a serious drawback to Curtius as a historian that with his purist Hellenic sympathies he treats the history of Greece as closed by Philip of Macedon, whereas in one sense it may be said that the history of a nation then only begins. The histories of Greece too often end with the death of Demosthenes, or the death of Alexander, though Freeman and Mahaffy have shown that neither the intellect nor the energy of the Greek race was at all exhausted. The German work of Holm, pronounced by Mahaffy to be amongst the very best, will soon be open to the English reader.

The historians of Rome, with two exceptions, are too diffuse, or too fragmentary: such mere epitomes or such uncritical compilations, that they have no such value for the general reader as the great historians of Greece. Yet there are few more memorable pages in history than are some of the best bits from the delightful story-teller Livy. We cannot trust his authority; he has no pretence to critical judgment or the philosophic mind. He is no painter of character; nor does he ever hold us spellbound with a profound thought, or a monumental phrase private tours istanbul.

But his splendid vivacity and pictorial colour, the epic fulness and continuity of his vast composition, the glowing patriotism and martial enthusiasm of his majestic theme, impress the imagination with peculiar force. It is a prose AEneid — the epic of the Roman commonwealth from AEneas to Augustus. It is inspired with all the patriotic fire of Virgil and with more than Horatian delight in the simple virtues of the olden time. For the first time a great writer devoted a long life to record the continuous growth of his nation over a period of eight centuries, in order to do honour to his country’s career and to teach lessons of heroism to a feebler generation. Had we the whole of this stupendous work, we should perhaps more fully respect the originality as well as the grandeur of this truly Roman conception.

The loss of the 107 books

One of the abiding sorrows of literature is the loss of the 107 books, out of the 142 which composed the entire series. They were complete down to the seventh century: now we have to be content with the ‘epitomes,’ or general table of contents. But 35 books, a little short of one quarter of the whole, have reached us. In these times of special research and critical purism, the merits of Livy are forgotten in the mass of his glaring defects. Uncritical he is, uninquiring even, nay, almost ostentatiously indifferent to exact fact or chronological reality.

He seems deliberately to choose the most picturesque form of each narrative without any regard to its truth; nay, he is too idle to consult the authentic records within reach. But we are carried away by the enthusiasm and stately eloquence of his famous Preface: we forgive him the mythical account of the foundation of Rome for the beauty and heroic simplicity of the primitive legends, and the immortal pictures of the early heroes, kings, chiefs, and dictators. Where the facts of history are impossible to discover, it is something to have epic tales which have moved all later ages. And we may more surely trust his narrative of the Punic wars, which is one of the most fascinating episodes in the roll of the Muse of History.

0 notes

Photo

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History of Greece are neither manageable nor necessary for any but regular scholars of the original authorities. But there are sections of his work of peculiar value and well within the scope of the general reader. These are: the account of the Athenian democracy (vol. iv. ch. 31); of the Athenian empire (vol. v. ch. 45); the famous chapters on Socrates and the Sophists (vol. viii. ch. 67, 68), and the account of Alexander’s expedition (vol. xii.). For the general description of Greece, Curtius is unrivalled, and in many things he is a valuable corrective of Grote’s pedantic radicalism. But it is a serious drawback to Curtius as a historian that with his purist Hellenic sympathies he treats the history of Greece as closed by Philip of Macedon, whereas in one sense it may be said that the history of a nation then only begins. The histories of Greece too often end with the death of Demosthenes, or the death of Alexander, though Freeman and Mahaffy have shown that neither the intellect nor the energy of the Greek race was at all exhausted. The German work of Holm, pronounced by Mahaffy to be amongst the very best, will soon be open to the English reader.

The historians of Rome, with two exceptions, are too diffuse, or too fragmentary: such mere epitomes or such uncritical compilations, that they have no such value for the general reader as the great historians of Greece. Yet there are few more memorable pages in history than are some of the best bits from the delightful story-teller Livy. We cannot trust his authority; he has no pretence to critical judgment or the philosophic mind. He is no painter of character; nor does he ever hold us spellbound with a profound thought, or a monumental phrase private tours istanbul.

But his splendid vivacity and pictorial colour, the epic fulness and continuity of his vast composition, the glowing patriotism and martial enthusiasm of his majestic theme, impress the imagination with peculiar force. It is a prose AEneid — the epic of the Roman commonwealth from AEneas to Augustus. It is inspired with all the patriotic fire of Virgil and with more than Horatian delight in the simple virtues of the olden time. For the first time a great writer devoted a long life to record the continuous growth of his nation over a period of eight centuries, in order to do honour to his country’s career and to teach lessons of heroism to a feebler generation. Had we the whole of this stupendous work, we should perhaps more fully respect the originality as well as the grandeur of this truly Roman conception.

The loss of the 107 books

One of the abiding sorrows of literature is the loss of the 107 books, out of the 142 which composed the entire series. They were complete down to the seventh century: now we have to be content with the ‘epitomes,’ or general table of contents. But 35 books, a little short of one quarter of the whole, have reached us. In these times of special research and critical purism, the merits of Livy are forgotten in the mass of his glaring defects. Uncritical he is, uninquiring even, nay, almost ostentatiously indifferent to exact fact or chronological reality.

He seems deliberately to choose the most picturesque form of each narrative without any regard to its truth; nay, he is too idle to consult the authentic records within reach. But we are carried away by the enthusiasm and stately eloquence of his famous Preface: we forgive him the mythical account of the foundation of Rome for the beauty and heroic simplicity of the primitive legends, and the immortal pictures of the early heroes, kings, chiefs, and dictators. Where the facts of history are impossible to discover, it is something to have epic tales which have moved all later ages. And we may more surely trust his narrative of the Punic wars, which is one of the most fascinating episodes in the roll of the Muse of History.

0 notes

Photo

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History of Greece are neither manageable nor necessary for any but regular scholars of the original authorities. But there are sections of his work of peculiar value and well within the scope of the general reader. These are: the account of the Athenian democracy (vol. iv. ch. 31); of the Athenian empire (vol. v. ch. 45); the famous chapters on Socrates and the Sophists (vol. viii. ch. 67, 68), and the account of Alexander’s expedition (vol. xii.). For the general description of Greece, Curtius is unrivalled, and in many things he is a valuable corrective of Grote’s pedantic radicalism. But it is a serious drawback to Curtius as a historian that with his purist Hellenic sympathies he treats the history of Greece as closed by Philip of Macedon, whereas in one sense it may be said that the history of a nation then only begins. The histories of Greece too often end with the death of Demosthenes, or the death of Alexander, though Freeman and Mahaffy have shown that neither the intellect nor the energy of the Greek race was at all exhausted. The German work of Holm, pronounced by Mahaffy to be amongst the very best, will soon be open to the English reader.

The historians of Rome, with two exceptions, are too diffuse, or too fragmentary: such mere epitomes or such uncritical compilations, that they have no such value for the general reader as the great historians of Greece. Yet there are few more memorable pages in history than are some of the best bits from the delightful story-teller Livy. We cannot trust his authority; he has no pretence to critical judgment or the philosophic mind. He is no painter of character; nor does he ever hold us spellbound with a profound thought, or a monumental phrase private tours istanbul.

But his splendid vivacity and pictorial colour, the epic fulness and continuity of his vast composition, the glowing patriotism and martial enthusiasm of his majestic theme, impress the imagination with peculiar force. It is a prose AEneid — the epic of the Roman commonwealth from AEneas to Augustus. It is inspired with all the patriotic fire of Virgil and with more than Horatian delight in the simple virtues of the olden time. For the first time a great writer devoted a long life to record the continuous growth of his nation over a period of eight centuries, in order to do honour to his country’s career and to teach lessons of heroism to a feebler generation. Had we the whole of this stupendous work, we should perhaps more fully respect the originality as well as the grandeur of this truly Roman conception.

The loss of the 107 books

One of the abiding sorrows of literature is the loss of the 107 books, out of the 142 which composed the entire series. They were complete down to the seventh century: now we have to be content with the ‘epitomes,’ or general table of contents. But 35 books, a little short of one quarter of the whole, have reached us. In these times of special research and critical purism, the merits of Livy are forgotten in the mass of his glaring defects. Uncritical he is, uninquiring even, nay, almost ostentatiously indifferent to exact fact or chronological reality.

He seems deliberately to choose the most picturesque form of each narrative without any regard to its truth; nay, he is too idle to consult the authentic records within reach. But we are carried away by the enthusiasm and stately eloquence of his famous Preface: we forgive him the mythical account of the foundation of Rome for the beauty and heroic simplicity of the primitive legends, and the immortal pictures of the early heroes, kings, chiefs, and dictators. Where the facts of history are impossible to discover, it is something to have epic tales which have moved all later ages. And we may more surely trust his narrative of the Punic wars, which is one of the most fascinating episodes in the roll of the Muse of History.

0 notes

Photo

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History

The twelve volumes of Grote’s History of Greece are neither manageable nor necessary for any but regular scholars of the original authorities. But there are sections of his work of peculiar value and well within the scope of the general reader. These are: the account of the Athenian democracy (vol. iv. ch. 31); of the Athenian empire (vol. v. ch. 45); the famous chapters on Socrates and the Sophists (vol. viii. ch. 67, 68), and the account of Alexander’s expedition (vol. xii.). For the general description of Greece, Curtius is unrivalled, and in many things he is a valuable corrective of Grote’s pedantic radicalism. But it is a serious drawback to Curtius as a historian that with his purist Hellenic sympathies he treats the history of Greece as closed by Philip of Macedon, whereas in one sense it may be said that the history of a nation then only begins. The histories of Greece too often end with the death of Demosthenes, or the death of Alexander, though Freeman and Mahaffy have shown that neither the intellect nor the energy of the Greek race was at all exhausted. The German work of Holm, pronounced by Mahaffy to be amongst the very best, will soon be open to the English reader.

The historians of Rome, with two exceptions, are too diffuse, or too fragmentary: such mere epitomes or such uncritical compilations, that they have no such value for the general reader as the great historians of Greece. Yet there are few more memorable pages in history than are some of the best bits from the delightful story-teller Livy. We cannot trust his authority; he has no pretence to critical judgment or the philosophic mind. He is no painter of character; nor does he ever hold us spellbound with a profound thought, or a monumental phrase private tours istanbul.

But his splendid vivacity and pictorial colour, the epic fulness and continuity of his vast composition, the glowing patriotism and martial enthusiasm of his majestic theme, impress the imagination with peculiar force. It is a prose AEneid — the epic of the Roman commonwealth from AEneas to Augustus. It is inspired with all the patriotic fire of Virgil and with more than Horatian delight in the simple virtues of the olden time. For the first time a great writer devoted a long life to record the continuous growth of his nation over a period of eight centuries, in order to do honour to his country’s career and to teach lessons of heroism to a feebler generation. Had we the whole of this stupendous work, we should perhaps more fully respect the originality as well as the grandeur of this truly Roman conception.

The loss of the 107 books

One of the abiding sorrows of literature is the loss of the 107 books, out of the 142 which composed the entire series. They were complete down to the seventh century: now we have to be content with the ‘epitomes,’ or general table of contents. But 35 books, a little short of one quarter of the whole, have reached us. In these times of special research and critical purism, the merits of Livy are forgotten in the mass of his glaring defects. Uncritical he is, uninquiring even, nay, almost ostentatiously indifferent to exact fact or chronological reality.

He seems deliberately to choose the most picturesque form of each narrative without any regard to its truth; nay, he is too idle to consult the authentic records within reach. But we are carried away by the enthusiasm and stately eloquence of his famous Preface: we forgive him the mythical account of the foundation of Rome for the beauty and heroic simplicity of the primitive legends, and the immortal pictures of the early heroes, kings, chiefs, and dictators. Where the facts of history are impossible to discover, it is something to have epic tales which have moved all later ages. And we may more surely trust his narrative of the Punic wars, which is one of the most fascinating episodes in the roll of the Muse of History.

0 notes