#author: francesca coppa

Text

Back to school edition: “So you want to be a Fan Studies scholar?” (aka "My 2¢, YMMV")

As a professor, I often supervise undergraduates who are interested in fan studies topics, often as independent studies or senior theses. Some of these students want to go on to do graduate work in fan studies–but that can be complicated, because fan studies is such an interdisciplinary subject. So I ask them: do they just want to continue studying fandom in an organized way, or are they considering grad school because they actually want to get a job / earn a living as a scholar or teacher? Let’s ignore the state of the market in higher ed (many ugh, much gross) for the moment, and talk purely about the intellectual issues involved in studying fandom.

Like, for instance, there really aren’t fan studies departments per se (and few institutions even have television studies) and hiring is still overwhelmingly a departmental thing. (That’s changing, but academia isn’t known for its lightning-fast pivots.) So what department would you looking to be hired into? Students often don’t know–they like literary study, they like media and communications, they like television and film, they like anthropology. So I ask them the question another way: if you got hired as a professor, what introductory courses do you think you’d enjoy teaching? Are your bread and butter courses going to be, say, Intro to British Literature I and II or Media and Society? Or maybe it would be Intro to Anthropology or Intro to Film Studies. Maybe it would be some form of Rhetoric and Composition. It might also be Intro to Marketing–some of the people most interested in fandom studies are business or economics professors, looking to better understand consumer behavior.

But the larger point is: few professors get to teach their exact areas of specialization all the time, and most professors teach one or more of their department’s intro courses. (You might also end up teaching high school: how does your fan studies interest overlap with a high school’s curricular needs?) So don’t just think about your research interest when you’re considering graduate schools and departments: think about how your research interests fit into and overlap with the broad knowledge base that you’ll need for a degree and a career.

–Francesca Coppa, Fanhackers volunteer

#fanhackers#fan studies#graduate school#academia: not known for its quick pivots!#happy back to school everyone#author: francesca coppa

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

TWC 42: Fandom and Platforms [Special Issue]

Editorial

Maria K. Alberto, Effie Sapuridis, and Lesley Willard; Putting forward platforms in fan studies

Article

David Kocik, PS Berge, Camille Butera, Celeste Oon, and Michael Senters; "Imagine a place:" Power and intimacy in fandoms on Discord

Kimberly Kennedy; "It's not your tumblr": Commentary-style tagging practices in fandom communities

Axel-Nathaniel Rose; #web-weaving: Parallel posts, commonplace books, and networked technologies of the self on Tumblr

Sam Binnie; Using the Murdoch Mysteries fandom to examine the types of content fans share online

Gamze Kelle; How Covid-19 has affected fan-performer relationships within visual kei

Rhea Vichot; The expression of sehnsucht in the Japanese city pop revival fandom through visual media on Reddit and YouTube

Welmoed Fenna Wagenaar; Discord as a fandom platform: Locating a new playground

Sourojit Ghosh and Cecilia Aragon; Leveraging community support and platform affordances on a path to more active participation: A study of online fan fiction communities

Paul Ocone; Fandom and the ethics of world-making: Building spaces for belonging on BobaBoard

Amber Moore; Analyzing an archive of allyish distributed mentorship in "Speak" fan fiction comments and reviews

Jionghao Liu and Ling Yang; Censorship on Japanese anime imported into mainland China

Lin Zhang; Boys’ love in the Chinese platformization of cultural production

Matt Griffin and Greg Loring-Albright; Platforming the past: Nostalgia, video games, and A Hat in Time

Irissa Cisternino; Players, production and power: Labor and identity in live streaming video games

Symposium

Yvonne Gonzales and Celeste Oon; Public versus private aca-fan identities and platforms: An academic dialogue

Dawn Walls-Thumma; The fading of the elves: Techno-volunteerism and the disappearance of Tolkien fan fiction archives

Martyna Szczepaniak; The differences between author’s notes on FanFiction.net and AO3

Muxin Zhang; Fandom image-making and the fan gaze in transnational K-pop fan cam culture

Sabrina Mittermeier; "One day longer, one day stronger": Online platforms, fan support and the 2023 WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes

Book review

Sebastian F. K. Svegaard reviews "Vidding: A history" by Francesca Coppa

Laurel P. Rogers reviews "Fandom, the next generation," edited by Bridget Kies and Megan Connor

Axel-Nathaniel Rose reviews "Mediatized fan play: Moods, modes and dark play in networked communities," by Line Nybro Petersen

Multimedia

Naomi Jacobs, Katherine Crighton, and Shivhan Szabo; Building the spear: A demonstration in faking and remaking real feelings for an imaginary work

Rachel Loewen; "Darkness never prevails": Doctor Who Covid-19 videos as keystones for pandemic engagement

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

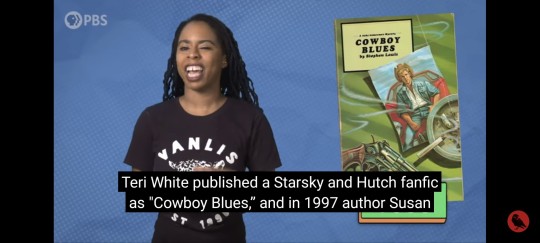

Pic sources:

youtube

The Case for Fan Fiction (feat. Lindsay Ellis and Princess Weekes) | It’s Lit by Storied

#fanfiction#writing#fandoms#history#pbs#video essays#screengrabs#quotes#comments#OC#OCs#Youtube#interviews#podcasts#imaginary worlds podcast#female representation

1 note

·

View note

Text

Very interesting podcast episodes about

fanfiction

fanfiction history

creation of AO3

The woman interviewed is Francesca Coppa author of the book "The fanfiction reader."

#ao3#archive of our own#fanfiction#fanfics#fanfic writing#fanfic writers#podcast recommendations#Spotify

0 notes

Note

Most of the gift economy stuff happens in prompt collections, like Yuletide or bingo based ones. But building the cornerstones for that happened off site, and it’s mostly short fiction, which isn’t as popular in some fandoms.

--

Haha.

Nonnie...

A "gift economy" does not refer to the direct exchange of literal gifts.

It's an economic system a whole culture has instead of having, say, a barter economy where you exchange goods for goods or a market economy where you exchange money for goods.

It's a technical term.

Francesca Coppa, an academic who sometimes writes on fandom, popularized it as a way of looking at fanfic circles—specifically the kind of Livejournal-y, slash fandom-y circles AO3 came out of. (At least... I think she's the one. Maybe one of the other acafans did it first. I'm too lazy to look this up, but feel free to add citations, everyone.)

The point of calling fandom this term is to point out certain social forces that Coppa thinks are present in "fandom"—and that are desirable and worthy of respect/protection/academic study.

Ooh, look, Wikipedia even says: "Some authors argue that gift economies build community,[7] while markets harm community relationships.[8]"

Basically, a gift economy is like your grandma making you cookies. Grandma doesn't expect money from you, and she doesn't expect a 1:1 exchange of labor or goods. She does expect some kind of ongoing grandparent-grandchild familial relationship. There's no charge, monetary or otherwise, for the cookies. On a wider, less emotionally intimate level, this looks like a person paying the sum total of their labor, goods, personal emotional support, etc. into some communal fund of Who I Am To The Community. In exchange, they get all the benefits of community membership.

This model confuses people because we rarely hear about whole societies that actually operate on this model. Even so-called "primitive" societies we learn about in school often operate more on a barter system.

So I meant what I said before:

My payment into the fandom gift economy is things like years of labor to build AO3, educational posts for the good of the community, my fic that I wrote for myself and for fun but that I chose to share.

The direct benefit I receive is social capital.

I am a member of the community by virtue of... well... doing community member things. They can be small things too, like bookmarking or commenting, not just big things like being able to produce longfic people love.

My gifts from the community, aside from social capital, include people's comments on my fic or interesting asks in my inbox, but they also include fics other people wrote for fun and chose to share. Those other people don't know me from Adam or may actively dislike me. They didn't write the fics for me. But I benefit from the general AO3 environment where I can get my free reading material just as other people benefit from me helping to build AO3.

The account I was paying into wasn't I Deserve Patreon Supporters or even I Deserve Comments. It was AO3 Exists And We All Benefit or it was I'm A Member of Fandom.

I write fic and now you comment in exchange is a barter economy.

Support my patreon so I can write more fic is a market economy.

I write fic and so do other people and now there's more fic for the fandom to enjoy is a gift economy.

I comment a lot to encourage writers so we can all have more fic is also a gift economy.

When we try to extract too much direct barter or cash from people in a gift economy, it fucks it up. It's like trying to pay Grandma for her cookies. Maybe Grandma gained $1, but she lost a huge amount of intangible benefit. The relationship is harmed by trying to monetize the tip of the iceberg while failing to see the part under the water.

This is confusing because the only places we encounter gift economies tend to be:

Fandom

Those 'buy nothing' groups on Facebook that are about building local community gift economies, decluttering, and reducing waste

Poorly-written accounts of white settlers destroying indigenous economies in the Americas

Here's Buy Nothing attempting to explain gift economies.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Saw this post on lack of comments/interactivity in fic making its round through some of my mutuals and it reminded me of this segment from Francesca Coppa’s “Writing Bodies in Space: Media Fan Fiction as Theatrical Performance” from The Fan Fiction Studies Reader.

The third theatrical quality I want to discuss in terms of fan fiction is the need for a live audience. A live audience has always been a precondition for fandom. Longtime fanzine editor and archivist Arnie Katz (n.d.) explains that science fiction magazines—particularly their letter pages—were essential to the genesis of science fiction fandom. As Katz notes, “Science fiction and fantasy were widely available for many years before fandom erupted. . . . Those who wanted to be more than readers couldn’t do much while books remained the main delivery vehicle for science fiction. It’s hard to interact with a book, other than to write a letter to the author in care of the publisher.” Science fiction fans have a saying: “fandom is a way of life”—which is to say, science fiction literature fandom is more than a celebration of texts; it’s a series of practices. This may be why most academic works on fandom are ethnographies, or analyses of social organizations and cultural performances. As Katz points out, fandom is essentially interactive in a way beyond the traditional reader-writer relationship. Fan fiction, too, is a cultural performance that requires a live audience; fan fiction is not merely a text, it’s an event.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ‘Does this make sense?’ check - Introduction, Part 1

Fanfiction does many of the things book historians are interested in, yet it is understudied from a book historical point of view. Fanfiction studies includes copyright and publishing history, reader-author relationships, communal reading practices, and material production. Writing and sharing fanfiction provides insight into contemporary, pop cultural reading practices and creative responses to multimedia texts. Fanfiction offers many entry points for book historians to consider textual production, the future of textual media and the digital book, and reader response. Fanfiction writers and readers alike engage with texts in myriad ways that unsettle many assumptions that book historians take for granted, including Robert Darnton’s communication circuit, the reexamination of which anchors this dissertation.

This dissertation relies on Francesca Coppa’s definition of fanfiction, which articulates six characteristics that illuminate the relationships between fic writers, fic readers, and distributing platforms. These six characteristics of fic are critical to the fic communication circuit: they place fic adjacent to Darnton’s standard model, they challenge ownership and for-profit motives of textual production, and they illustrate a more immediate reader response and creative interpretation than is typical in analogue media:

Fic is ‘created outside of the literary marketplace’, that is, without the intent for profit and without the institutional recognition of traditional publishing.

Fic ‘rewriters and transforms other stories’, and

Fic ‘rewrites and transforms other stories currently owned by others’. Coppa elaborates: ‘it is only in such a system—where storytelling has been industrialized to the point that our shared culture is owned by others—that a category like “fanfiction” makes sense’ [1]. That is to say, in a system where stories can be bought or sold, the transformative, for-pleasure work of fanfiction is defined in contradistinction to for-profit story production and distribution; in a system without purchase and ownership of stories, the work of fanfiction would be called ‘folklore’.

Fic is ‘written within and to the standards of a particular fannish community’: fic writers signal to their readers their understanding of a fandom and place within it using intertextuality and other methods.

Fic is speculative in that it is (often) more interested in ‘character rather than about the world’. Fic provides space to elaborate on internal motivations, examine secondary characters in the source text, and explore how circumstances change a character.

Fic is ‘made for free, but not “for nothing”’, meaning that while fic is rarely made and shared for profit, participants receive satisfaction in the form of kudos, feedback, art, and friendship [2].

These features place fanfiction (and the fanfiction communication circuit) outside of traditional publishing, maintained by different criteria. As a textual practice often associated with women’s crafts, fanfiction shares characteristics with coterie manuscript practices: non-profit driven, for pleasure, and privately produced. Catherine Coker argues that this gendering reinforces the ‘hierarchies of value between print and digital that emphasize traditional patriarchal and public practices of reading and writing over private coterie practices’ [3]. She notes that fanfiction, which is dominated by women and gender-nonconforming people, was born from and is a continuation of these ‘private coterie practices’ that were not valued precisely because they were ‘women’s work’ and ‘not-for-profit’ [4]. In examining the function of writer, reader, and fannish response in the succeeding chapters, I argue that fanfiction attains value and success through community and gift-giving, rather than the norms of profit and mainstream circulation.

Darnton presents a sufficient and adaptable model for describing the relationship between author, printer, publisher, distributor, and reader in his communication circuit [5]. Padmini Ray Murray and Claire Squires note that in a reconstructed circuit for the digital publishing age, ‘the traditional value chain, …is being disrupted and disintermediated at every stage’ [6]. This disruption in the traditional circuit holds true for the production, dissemination, and consumption of fanfiction. Because fanfiction mostly exists in tandem to the source text upon which it is based and, by extension, the literary marketplace, I model the fanfiction communication circuit in tandem with, rather than superimposed upon, Darnton’s communication circuit. Murray and Squires argue that in digital publishing, the author and publisher roles and the publisher and distributor roles are conflated. In fanfiction (hereafter referred to as fic), production and distribution are similarly conflated, as the publishing (rather, posting) and distributing platforms are one and the same for many interfaces, and the fic writer has sole control over posting their work. These conflations merit a ‘re-examination’ of Darnton’s model, in which I outline a fandom communications circuit in tandem with Darnton’s circuit to parallel, rather the superimpose upon, the circulation of fic text with source text [7].

This dissertation examines transformative works: works that change, even ever so slightly, the metatext unto a given purpose. In 2002, a representative at LucasFilm said, ‘“We've been very clear all along on where we draw the line. We love our fans, we want them to have fun. But if in fact somebody is using our characters to create a story unto itself, that's not in the spirit of what we think fandom is about. Fandom is about celebrating the story the way it is”’ [8]. This statement marks the difference between affirmational and adaptive-transformational fandom (and the notion that creatively responding to a work is somehow not celebrating it) [9]. Transformational fandom is less interested in taking the work as it is, as LucasFilm attempts to dictate, and more interested in intervening in a source text for new or continued storytelling. Transformative fanfiction turns commonly-accepted models of Anglo-American book production on its head: book history often operates under a precept to follow the money. In the case of fanfiction, there is typically no financial compensation, and we must instead follow the fan community. The return is in the gift-economy, comprising kudos, likes, favorites, follows, art, feedback, comments, and further works inspired by one’s own.

Citations

Francesca Coppa, The Fanfiction Reader: Folk Tales for the Digital Age (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2017), p.7.

Coppa, The Fanfiction Reader, pp.2-14.

Catherine Coker, ‘The margins of print? Fan fiction as book history’, Transformative Works and Cultures, 25 (2017)<https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/1053>1.2.

Coker, ‘The margins of print?...’, 2.2.

Robert Darnton, ‘What is the history of books?’, Daedalus, 111, pp.65-83.

Padmini Ray Murray and Claire Squires, ‘The digital publishing communications circuit’, Book 2.0, 3 (2013), p.3.

Murray and Squires, ‘The digital publishing communications circuit’, p.4.

Amy Harmon, ‘“Star Wars” Fan Films Come Tumbling Back to Earth’, The New York Times, 28 April, 2002; Maciej Ceglowski, ‘Fan is A Tool-Using Animal’, 6 Sep 2013, <https://idlewords.com/talks/fan_is_a_tool_using_animal.htm>.

obsession_inc, ‘Affirmational fandom vs. Transformational fandom’, dreamwidth, 2009 <https://obsession-inc.dreamwidth.org/82589.html>.

#does this make sense check#dissertation#research#introduction#fanfiction communication circuit#fanfiction definition#Francesca Coppa#Catherine Coker#Robert Darnton#Padmini Ray Murray#Claire Squires#Amy Harmon#obsession_inc#transformational vs affirmational

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Slash/drag: Appropriation and Visibility in the Age of Hamilton” by Francesca Coppa

(from A Companion to Media Fandom and Fan Studies)

“Slash fiction, a genre of erotic fan fiction written by women authors about male characters, is perhaps the most notorious art form to come out of media fandom. This chapter contextualizes slash fiction in terms of the theory and history of drag performance. In classic drag, gay men embody highly overdetermined female characters to say something about gender and identity that cannot be said through their own, everyday personas. It is argued that, similarly, slash writers stage highly overdetermined male characters and performances for similar purposes and with similar community‐building effects. Like drag, slash can be seen as a form of appropriation, but it is argued that in both slash and drag, what is being performed is in fact original and artistically significant, and that these performances make new meanings possible and other meanings visible. Both performances are critical analyses that show‐do gendered behavior and create space for new sexual‐social roles.”

#slash#fan studies#francesca coppa#i wanted to quote this whole essay but that would make a bad tumblr post#it is not without problems in framing but it raises so VERY MANY valid points in fun ways#i love it when academic writing is just fucking... clear about what it's saying#and playful#and mentions ray kowalski#:')))

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Q&A:

Hello! Sorry for the belated question-answering. My concussion symptoms got a lot worse for a hot second, but I’m feeling better now and ready to tackle my inbox. So I have over 30 academic-related questions and they mostly fall into these groups:

Can I read your dissertation/are you going to publish it?

Yes! And hopefully. The plan is to publish it as a book once it is complete, but even if that doesn’t happen I’ll share it (maybe even on AO3) with anyone who wants to read it.

What is your dissertation about?

That is a dangerous question. The shortest possible answer: my dissertation is essentially an ethnographic study of the interconnected online platforms that facilitate transformative digital fan culture and the people that use them. I consider fic literature and fic archives repositories for both this textual literature but also the metatextual and paratextual elements of fan culture. My focus is on the AO3 as a groundbreaking archive that has changed how transformative fandom operates, is treated legally, and is viewed publicly.

How are you getting a PhD in fandom? Is that a thing? Did you take classes for it?

Fandom studies is a thing! When you get an English PhD you specialize in certain things, and fandom studies is one of my specialties. Alas, I did not take classes in it, though I did do a significant amount of directed reading on my own/in preparation for exams. PhD coursework prepares you for the broad range of English classes you may be called upon to teach as a professor. So I took multiple courses in my primary fields (see below) but only took classes for my first two subfields. I also took Victorian lit, British lit, American lit, etc.

What did you take your quals in?

Primary Fields: (these are things that make colleges want to hire you)

Book history/archival (focus movement from print-digital)

Feminist/queer theory

20/21st century lit

Subfields: (these are the things that you think are neat if not included in the things that will make colleges want to hire you)

disability studies

minority literature

comics studies

fandom studies

Where do you go to school?

SMU. In Dallas. We have great libraries and lots of white people who wear Vinyard Vines apparel.

You’re the xiaq that wrote LRPD/AHTU/Strut! Are you going to talk about your own fic in your dissertation? Yes. And yes! I’ll speak as a 3rd party academic observer in chapter 1-3 and 5, but chapter 4 will be a case study/interlude where I speak in depth about my experience writing and posting LRPD (https://archiveofourown.org/works/11304786?view_full_work=true). I’m doing this for 2 reasons: 1. The project asserts that there is nothing shameful about participating in fandom and fan works/archives ought to be shown respect and appreciation. I want both fandom folks and academic folks to know that I’m “all in” as it were. 2. When I sat down with my chair to plan my case study chapter, we decided I needed a “top-ranked” work within any moderate to large fandom with over 50,000 hits and over 5,000 comments, and I needed to ask the author detailed questions about their writing, editing, posting, sharing, and comment-answering/interactive habits. LRPD fits that criteria and I don’t have to ask anyone else invasive questions.

Who all have you interviewed?

Cesperanza/Astolat and a couple other AO3 founding folks. Several people currently volunteering for the OTW, one of the volunteer coordinators, communications staff, and a LOT of fan writers (over 50 at this point)—including BNFs like Kryptaria, Earlgreytea68, Emmagrant01 and (much) more. And then a bunch of academic folks too—Karen Hellekson, Abigail De Kosnik, Francesca Coppa, Rukmini Pande, Suzanne Scott (who is on my committee as an outside reader!) and more. Every single person I’ve spoken to was very kind and generous with their time and I love everyone in this bar.

And these were three specific questions that didn’t fall into those categories:

You look so young—is that just good genetics or did you skip a few grades?

Thank you! Well. I skipped getting my masters. Sort of. Most PhD programs require an undergraduate and a masters degree before you can apply. SMU is one of the few that does not and has an extended program that essentially gives folks straight from undergrad extra intensive coursework and a masters upon completion of 2 yrs in the program. It’s difficult to get accepted without a masters, so consider me an outlier and not the standard. I’m also on course to (hopefully) graduate a year early—which means I’ll have my doctorate before I turn 30! You too can be an overachiever with the help of OCD, anxiety, and sleep deprivation (not an endorsement, tho).

what does otw mean in your ao3 post about academics being assholes

Organization for Transformative Works! The OTW formed before the AO3 did. You can read more about it here: https://fanlore.org/wiki/Organization_for_Transformative_Works

Concerning your post on AO3 and the pettiness of academics - you mentioned the real, serious negative issues concerning AO3. Might you expand more on that? What do you find to be the negative aspects of AO3?

Ah yes. So there is one “big” thing that occasionally came up as a negative in my interviews and research. Fandom has a long and storied history of racism. It’s not isolated to the AO3, but several of the POC I spoke to said they dislike the fact that there’s no way to mark a work as racist, or warn others about it (usually, if an individual points out that, say, an author has treated Finn as a Big Black Dick and not, you know, a human being, the author isn’t particularly interested in noting that their own work is problematic. See also: slave AUs. Where Finn is a slave.Yikes.). While the majority of POC I spoke to didn’t advocate for some sort of censure of these works in the terms of use (some did), what most wanted was a way of being able to warn others, or receive a warning, that a work is racist. Implementing something like that is, obviously, complex (if not impossible) however. Personally? I doubt it will happen.

Related, and perhaps more important, when POC tend to speak critically about the erasure or infantilization or animalization of non-white characters, white authors often 1. police tone rather than engage with the criticism, 2. focus more on defending themselves rather than actually examining their, maybe accidental, biases/stereotypes or 3. cry bullying or kinkshaming instead of actually listening to what POC are saying. Again, not an issue isolated to the AO3, but an issue nonetheless that we, as a community, need to recognize (for more on this history, check out, for example, https://fanlore.org/wiki/RaceFail_%2709).

There’s also the whole “should illegal sexual things--like underage or pedophilia-- be allowed,” which I don’t have the energy to dissect right now, but the overwhelming majority of folks I spoke to were of the “if you don’t like it, don’t read works with that tag. If it’s not tagged correctly, close the tab” school of thought. The AO3 has always purported itself as a hosting, not a policing, organization, so I doubt that will ever change.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE NARNIA NOVEL IS NOT FANFICTION. FANFICTION IS BETTER.

[Image: this still from the Narnia film is Aslan and Edmund judging this foolishness.]

You may have heard that a male writer of “award-winning adult literature” wrote an “unauthorized Narnia novel” and now (as in every time this kind of thing happens) everyone is all ‘ooooooh amaaaazing’ and ‘gosh isn’t this a cool art form’ and ‘maybe copyright law should allow for this kind of thing!’

If you’re like me, your eyes rolled so hard they almost fell out of your head. You might have also had the same reaction as @themarysue, which is that we should call this what it is: fanfiction. Which makes a ton of sense because there’s an infuriating, gendered double standard here; “I guess it gets a fancy title if a man writes it.”

But I don’t want to call this fanfiction. Because fanfiction is better.

In Francesca Coppa’s book The Fanfiction Reader: Folk Tales for the Digital Age, she introduces "five things fanfiction is and one thing it isn't." One thing it is, is "written within and to the standards of a particular fannish community." Fanfiction isn't just produced outside the market; it's produced inside fandom. Granted, this doesn't mean that fanfiction must be SHARED in order to be fanfiction, but someone who is completely disengaged from fandom (having no knowledge of it, not even a lurker) is, in my opinion, probably creating something that's somewhat different.

So the really infuriating thing is when someone creates something with the same surface characteristics as fanfiction but suddenly it is more legitimate and not worthy of scorn, BECAUSE IT IS OUTSIDE OF FANDOM.

I don't need this Narnia thing to be called fanfiction, because it's not as awesome as fanfiction is, because it's not part of fandom. But for those who look down on fanfiction or think it's not "real" writing or whatever, THE SAME THING should be true for that “unauthorized novel.” In other words, Spufford’s book doesn’t get to be fanfiction. But there’s no way it’s better or more legitimate than fanfiction.

P.S. If you saw the ridiculous “Technically, though, all fanfic writers are in breach of the law and could be prosecuted” line in the other Guardian piece, rest assured that that’s total lion poop.

(This rant first appeared on Twitter but my frustration could not be contained in micro-blogging.)

Edit for clarification: (though who knows who will see, because reblogs :) ) To be clear, as OTW says, you’re a fan if you say you’re a fan. Which means that you write fanfiction if you say you write fanfiction. There aren’t any barriers to entry! So if this author wanted to embrace that this is fanfiction he still could--but if he doesn’t want to I don’t think we should force the label onto it. :)

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introductions and Definitions

Hello and welcome to Archive of my Academics the site where I, Chris, Master’s student at the University of Arizona and self identified nerd, attempt to dive into fanfiction culture to understand it better.

I should start with a little background. I’ve always been a fan of things (Harry Potter, Twilight for half a second, the MCU, and Yuri!!! on Ice to name a few) but I don’t necessarily know that I’ve always participated in fandom (though that depends on your definition of fandom, which I’ll get to in a second.) Don’t get me wrong, I’ve written fanfic before, but I was never super participatory in whatever culture and conversation might have been going on in my fandom, aside from following a few tags on Tumblr, and maybe a few specific accounts I found by searching those tags. I never even read much fanfic, to be completely honest. Only four or five in recent memory.

Given all of that you might be asking yourself, “Chris, why did you agree to explore the topic of fanfic for class for a whole semester? It doesn’t even seem like you’re all that invested in it.” And that, dear reader, is where you are wrong. I absolutely adore the few fanfics I read, and I really enjoyed the few that I’ve written. I’m just...not a joiner. My social circle has always been small and that pertains to my online presence as well as IRL. But just because the volume of my participation is low does not mean my enjoyment of and investment in the community is.

So with that out of the way, let me get to the main event.

What the heck is fanfic anyway? Definitions are important, a way to place borders on subjects so I don’t lose my mind amidst a pile of miscellaneous academia and the internet. To that end I’m going to attempt to define “fanfic”, a task which turns out to me much more herculean than I’d originally thought.

Let’s start with the easiest definition first:

Merriam-Webster saves the day again. What would we do without the dictionary?

Well, for one thing, we might have less discourse regarding the difference between fan fiction and fanfiction. (I’ll be referring to it as fanfic for the duration of my study.)

Back to the definition. This one from the dictionary was lacking, to me. It doesn’t capture the complexities of the genre. Would you just define romance as books about people in love? Or science fiction as books about time travel? No, the definitions are more nuanced. So, too, is fanfic. So I moved on and left the dictionary behind.

In “The Promise and Potential of Fan Fiction”, Stephanie Burt explores what fanfic can mean to a wider audience. She quotes Francesca Coppa, author of The Fan Fiction Reader who defines fanfic as “creative material featuring characters [from] works whose copyright is held by others.” This definition is definitely narrower, but is it right? That would mean every canonical/in universe novel written about Star Wars but not by George Lucas would be fanfic, which isn’t quite true either.

I think the best answer to this question can from the podcast Fansplaining. In 2017 Flourish Klink (who’s name makes me want to write a short story about a witch who lives in a cozy cottage in the woods drinking tea with her cats, but that’s neither here nor there) and Elizabeth Minkel posted a survey asking their listeners what fanfic actually is and boy howdy did their listeners respond! Over 3,400 people answered a few multiple choice questions then held forth in long answer form on what fanfic meant to them.

The answers ranged from funny to serious, from hard lines to soft edges. Some find, like the dictionary, that any story written by a fan is fanfic. Some think that fanfic must be written by someone active in the fandom. Others maintain that you must receive no money for your work. Some, like Elizabeth herself in the episode where the two hosts discuss the survey, hold that it’s all about intent. Did you intend to write a transformative* story about the characters you love so dearly? Congratulations, you’re a fanfic author!

By some of these definitions I have written fanfic, while by others I haven’t. Is this the part where I should introduce the shrug emoji and move on with my life? Maybe, but I want to offer a few more thoughts first.

Part of defining fanfic means defining the term fandom, and even the term fan itself. In another episode of the podcast, Flourish and Elizabeth debate the definitions of both terms. Is fandom comprised of only people who interact with each other about the topic in question? That would mean lurkers (which I kind of consider myself to be) aren’t really part of it? But they’re still fans, as long as they like the thing, right? Or do you have to interact with the fandom (even just lurking) to be considered a fan? Would someone living on an ice floe with a copy of Pride and Prejudice really be considered a fan if they couldn’t at least stand at the border of the community and see what’s going on?

The answer the two come to, which I fundamentally agree with, is that it’s all in the intent. If you like the thing and you think you’re a fan, congratulations and welcome to the tribe! The fandom is yours for the taking! But just like the geographical kingdoms of yore, fandom is comprised of many counties, each with their own culture and interpretation. And there are many fandoms, not just media fandoms but sports and bands and inanimate objects (yes, there is a candle fandom.)

So there it is. A confusing, not at all settled definition of fanfic. But a definition is not the thing. A definition doesn’t necessarily tell you what the thing means. So that’s what I’m going to spend the rest of the semester trying to figure out. What is fanfic, what does it mean to the people who write it and read it, the people who laud it and denigrate it?

I’ll leave you with this section from Burt’s article, describing what fanfic can be:

“What is fan fiction especially, or uniquely, good at, or good for? Early defenses presented the practice as a way station, or an incubator. Writers who started out with fanfic and then found the proper mix of critique and encouragement could go on to publish “real” (and remunerated) work. Other defenses, focussed on slash, described it as a kind of safety valve: a substitute for desires that could not be articulated, much less acted out, in our real world. If women want to imagine sex between people who are both empowered, and equal, the argument ran, we may have to imagine two men. In space.

It’s true that a lot of fanfic is sexy, and that much of the sex is kinky, or taboo, or queer. But lots of fanfic has no more sex than the latest “Spider-Man” film (which is to say none at all, more or less). Moreover, as that shy proto-fan T. S. Eliot once put it, “nothing in this world or the next is a substitute for anything else.” It’s a mistake to see fanfic only as faute de mieux, a second choice, a replacement. Fanfic can, of course, pay homage to source texts, and let us imagine more life in their worlds; it can be like going back to a restaurant you loved, or like learning to cook that restaurant’s food. It can also be a way to critique sources, as when race-bending writers show what might change if Agent Scully were black. (Coppa has compared the writing of fanfic to the restaging of Shakespeare’s plays.)

Fanfic can also let writers, and readers, ask and answer speculative and reflective questions about our own lives, in a way that might get others to pay attention. What will college be like? What should summer camp have been like? How can an enemy become a friend? Should I move to Glasgow? What would that be like?”

What would that be like? I’m going to take some time to find out.

*I’ll be discussing the meaning and importance of the word “transformative” in the one of my next posts. Something to look forward to!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fictophilia

If I were to simplify (okay, fine: oversimplify) the field of fan studies, I’d say that scholars typically take one of two broad disciplinary approaches: either they look at fan works (and come from fields like literary studies, media and film studies, etc.) or they look at fan cultures and social organizations (ethnography, anthropology.) But other academic disciplines produce research that might be pertinent to fans and fan studies–for instance, psychology.

I recently came across an article called “Fictosexuality, Fictoromance, and Fictophilia: A Qualitative Study of Love and Desire for Fictional Characters,” (2020) written by Veli-Matti Karhulahti and Tanja Välisalo in the journal Frontiers of Psychology. The abstract explains:

Fictosexuality, fictoromance, and fictophilia are terms that have recently become popular in online environments as indicators of strong and lasting feelings of love, infatuation, or desire for one or more fictional characters. This article explores the phenomenon by qualitative thematic analysis of 71 relevant online discussions. Five central themes emerge from the data: (1) fictophilic paradox, (2) fictophilic stigma, (3) fictophilic behaviors, (4) fictophilic asexuality, and (5) fictophilic supernormal stimuli. The findings are further discussed and ultimately compared to the long-term debates on human sexuality in relation to fictional characters in Japanese media psychology. Contexts for future conversation and research are suggested.

The article is generally descriptive and nonjudgmental, and the authors note that “the present intention is not to propose fictophilia as a problem or a disorder,” but instead to assert that most people are “fully aware of the love-desire object’s fictional status and the parasocial nature of the relationship.” (In other words, we’re mostly pretty sane!) The essay also cites some interesting work that I’ve not seen typically referenced in literary or ethnographic fan studies works, including the proto-fan studies text Imaginary Social Worlds, by John L. Caughey (1984). While Caughey’s book (like many works of the 1980s) starts by evoking the figure of crazy or even homicidal fan (think Mark David Chapman or John Hinkley), his goal is to argue that ‘fantasy relationships’ are actually pretty normal. The book looks at “fantasy relationships” across history, connecting fan crushes on characters and celebrities “to the lifelong bonds that people in different cultures have conventionally had with gods, monarchs, spirits, and other figures that they may never have had the chance to meet in person.” While Caughey’s book is focused on Western history, Karhulahti and Välisalo’s “Fictosexuality” takes its examples primarily from Japan, examining numerous psychological studies of “Japan and its fiction-consuming ‘otaku’ cultures.” This gives it a global take not always seen in English-language fan studies texts (which tend to deal primarily with Western media.) “Fictosexuality” is also unusual for its interest in making connections between asexuality and fictophilia, asexuality also being underrepresented (and under-theorized) in fan studies texts.

Fans have historically been wary of any attempt to psychoanalyse them–and fair enough: after all, it was only recently that people stopped assuming that all fans were out-of-control “fanatics,” and there’s been a lot of creepy and misleading work on fandom done by outsiders. (If you want agita, look up SurveyFail on Fanlore.) But psychology and related fields may also have methods which allow us to understand fans and fandom in new ways.

–Francesca Coppa, Fanhackers volunteer

#author: Francesca Coppa#fanhackers#psychology#fictophilia#I love many imaginary people#and some real ones :D

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

We Want the Wilderness Intro: Works Cited

Abad-Santos, Alex. “Brie Larson Calls for More Women and Critics of Color to Be Writing about Movies.” Vox, 14 Jan. 2018, www.vox.com/culture/2018/6/14/17464006/brie-larson-representation-film-criticism.

Baudrillard, Jean. For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign. Telos P, 1981.

Betancourt, David. “Let’s Talk about the Shocking Ending of ‘Avengers: Infinity War.’” WashingtonPost.com, 30 Apr. 2018, www.washingtonpost.com/news/comic-riffs/wp/2018/04/30/lets-talk-about-the-shocking-ending-of-avengers-infinity-war-do-the-deaths-mean-anything/?utm_term=.f8f5347387d2.

Bolland, Brian. “On Batman: Brian Bolland Recalls The Killing Joke.” DC Universe: The Stories of Alan Moore, by Alan Moore. DC Comics, 2006. p. 247.

Bourdieu, Pierre. The Field of Cultural Production, edited by Randall Johnson, Columbia UP, 1993.

---. The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, translated by Susan Emanuel, Stanford UP, 1995.

Breznican, Anthony. “Rogue One: Alternate Ending Revealed: A Lifesaving Escape.” Entertainment Weekly, 20 Mar. 2017, ew.com/movies/2017/03/20/rogue-one-alternate-ending-revealed/.

Brooks, Dan. “SWCE 2016: 15 Things We Learned from the Rogue One: A Star Wars Story Panel.” Star Wars, 15 Jul. 2016, www.starwars.com/news/swce-2016-15-things-we-learned-from-the-rogue-one-a-star-wars-story-panel.

Buckley, Cara. “When ‘Captain Marvel’ Became a Target, the Rules Changed.” The New York Times.com, 13 Mar. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/03/13/movies/captain-marvel-brie-larson-rotten-tomatoes.html?login=email&auth=login-email.

Cattani, Gino, Simon Ferriani, and Paul D. Allison. “Insiders, Outsiders, and the Struggle for Consecration in Cultural Fields: A Core-Periphery Perspective.” American Sociological Review, Vol. 79, no. 2, 2014, pp. 258-81.

Certeau, Michel de. The Practice of Everyday Life. U of California P, 1984.

Coppa, Francesca. “An Archive of Our Own: Fanfiction Writers Unite!” Fic: Why Fanfiction is Taking Over the World, edited by Anne Jamison, Smart Pop, 2013, pp. 302-308.

Couch, Aaron. “Marvel Movies: The Complete Timeline of Upcoming MCU Films and Disney+ Shows.” The Hollywood Reporter, 20 Sept. 2016, www.hollywoodreporter.com/lists/marvel-movies-upcoming-timeline-release-dates-phase-3-929626.

Cranswick, Amie. “Kevin Feige Names Black Panther As the Best Movie that Marvel Has Made.” The Flickering Myth, 11 Jun. 2018, www.flickeringmyth.com/2018/06/kevin-feige-names-black-panther-as-the-best-movie-that-marvel-has-made/.

Dockterman, Eliana. “Here’s a Complete List of All the Upcoming Marvel Movies.” Time.com, 17 Apr. 2018, time.com/5167535/upcoming-marvel-movies/.

Dunn, Robert. "Television, Consumption and the Commodity Form." Theory Culture & Society, Vol. 3, no. 1, 49-64.

Ebiri, Bilge. “Ten Years Later, ‘The Dark Knight’ and It Vision of Guilt Still Resonate.” The Village Voice.com, 18 July 2018, www.villagevoice.com/2018/07/18/10-years-later-the-dark-knight-and-its-vision-of-guilt-still-resonate/.

Fiske, John. “The Cultural Economy of Fandom,” The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media, edited by Lisa A. Lewis. Routledge, 1992, pp. 30-49.

Foundas, Scott. “Cinematic Faith.” Film Comment.com. The Film Society of Lincoln Center, 28 Nov. 2012, www.filmcomment.com/article/cinematic-faith-christopher-nolan-scott-foundas/.

Ford, Rebecca. “Director Gareth Edwards Reveals ‘Star Wars: Rogue One’ Centers on Death Star Heist.” The Hollywood Reporter, 19 Apr. 2015, www.hollywoodreporter.com/heat-vision/director-gareth-edwards-reveals-star-789951.

Gray, Jonathan, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington. Introduction: Why Study Fans? Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World, edited by Johnathan Gray, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington, New York UP, 2007. pp.1-16.

Hills, Matt. “Absent Epic, Implied Story Arcs, and Variation on a Narrative: Doctor Who (2005-8) as Cult/Mainstream Television.” Third Person: Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives, edited by Pat Harrington and Noah Wardrip-Fruin. MIT Press, 2009, pp. 333-42.

Hood, Cooper. “Kevin Feige Says Black Panther is the MCU’s Best Movie to Date.” Screenrant, 17 Feb. 2018, https://screenrant.com/black-panther-best-mcu-movie-kevin-feige/.

Jenkins, Henry. Textual Poachers: Televisions Fans and Participatory Culture. Routledge, 2003.

Jones, Craig Owen. “Life in the Hiatus: New Doctor Who Fans, 1989-2005. Fan Phenomena: Doctor Who, edited by Paul Booth, University of Chicago Press, 2013, pp. 36-43.

Karim, Anhar. “How the Spider-Man Trailer May Hurt ‘Avengers: Endgame.’” Forbes.com, 20 Jan. 2019, www.forbes.com/sites/anharkarim/2019/01/20/how-the-spider-man-trailer-may-hurt-avengers-endgame/#25a0d5ad5056.

McMillan, Graeme. “‘Captain Marvel’ Targeted by Negative Online Reviews Prerelease,” 19 Feb. 2019, www.hollywoodreporter.com/heat-vision/captain-marvel-targeted-by-negative-online-reviews-pre-release-1188109?fbclid=IwAR1xyzXBkHMA53aM-BpvEh8xR8WzmTnnYFt8RuebMR6htoZdn9VpCXuBKnw.

---. “What Happens When ‘Star Wars’ Is Just a War Film?” The Hollywood Reporter, 20 Apr. 2015, www.hollywoodreporter.com/heat-vision/what-happens-star-wars-is-790216.

McVey, Ciara. “Ryan Coogler Explains Why ‘Black Panther’ Is a Political Film.” The Hollywood Reporter, 18 Dec. 2018, www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/ryan-coogler-explains-why-black-panther-is-a-political-film-watch-1170585.

Perryman, Neil. “Doctor Who and the Convergence of Media: A Case Study in ‘Transmedia Storytelling.’” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, Vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 21–39.

Polo, Susana. “The Batman Comics That Inspired The Dark Knight’s Hyper-realism.” Polygon, 17 Jul. 2018, www.polygon.com/comics/2018/7/17/17564454/batman-comics-that-inspired-christopher-nolan-dark-knight.

Rahmanan, Anna Ben Yehuda. “Rotten Tomatoes Looking to Change Audience Reviews Process to Fight Trolls.” Forbes.com, 15 Mar. 2019, www.forbes.com/sites/annabenyehudarahmanan/2019/03/15/rotten-tomatoes-looking-to-change-audience-reviews-process-to-fight-trolls/#6fada91668de.

Raftery, Brian. “Trolls Are Tanking Captain Marvel’s Rotten Tomatoes Reviews. But They Can’t Stop Its Box Office Haul.” Fortune.com, 9 Mar. 2019, fortune.com/2019/03/08/captain-marvel-rotten-tomatoes-review/fortune.com/2019/03/08/captain-marvel-rotten-tomatoes-review/.

Romano, Aja. “The Archive of Our Own is Now a Hugo Nominee. That’s Huge for Fanfiction.” Vox, 11 April 2019, www.vox.com/2019/4/11/18292419/archive-of-our-own-hugo-award-nomination-related-work.

Sandvoss, Cornel. Fans: The Mirror of Consumption. Polity Press, 2005.

---, Johnathan Gray, and C. Lee Harrington. Introduction: Why Still Study Fans? Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World, edited by Johnathan Gray, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington, 2nd ed. New York UP, 2017. pp.1-26.

Schick, Michal. “Archive of Our Own’s Hugo Nomination is a Win for Marginalized Fandom.” Hypeable, 4 April 2019, www.hypable.com/archive-of-our-own-hugo-awards-fandom/.

Serwer, Adam. " The Tragedy of Erik Killmonger." The Atlantic.com, 28 Feb. 2018, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2018/02/black-panther-erik-killmonger/553805/.

Sims, David. “A Change for Rotten Tomatoes Ahead of Captain Marvel.” The Atlantic.com, 4 Mar. 2019, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/03/rotten-tomatoes-captain-marvel-review-ratings-system-online-trolls/584032/.

---. “The Complicated Legacy of Batman Begins.” The Atlantic.com, 10 Jun 2015, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/06/the-complicated-legacy-of-batman-begins/395477/.

Torgersen, Brad R. “Sad Puppies 3: The Unraveling of an Unreliable Field.” Brad R. Torgersen: Blue Collar Speculative Fiction, 4 Feb. 2015, bradrtorgersen.wordpress.com/2015/02/04/sad-puppies-3-the-unraveling-of-an-unreliable-field/.

Tulloch, John. “’We’re Only a Speck in the Ocean: The Fans as Powerless Elite.” Science Fiction Audiences: Watching Doctor Who and Star Trek, by John Tulloch and Henry Jenkins, Routledge, 1995. pp.144-172.

Ugwu, Reggie. "The Stars of 'Black Panther ' Waited a Lifetime for This Moment." The New York Times, 12 Feb. 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/12/movies/black-panther-marvel-chadwick-boseman-ryan-coogler-lupita-nyongo.html.

VanDerWerff, Todd. “Avengers: Infinity War’s ending is incredibly bold. And maybe a little cheap.” Vox, 27 Apr. 2018, www.vox.com/summer-movies/2018/4/27/17281060/avengers-infinity-war-spoilers-ending-who-dies.

Wilbur, Brock. “Alan Moore Has A Lot To Say About ‘The Killing Joke.” Inverse, 28 Apr. 2016, www.inverse.com/article/14967-alan-moore-now-believes-the-killing-joke-was-melodramatic-not-interesting.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Imaginary Worlds Ep. 98

Last year, I interviewed Francesca Coppa for my episode Fan Fiction (Don't Judge.) She's the author of the book "The Fanfiction Reader," and one of the founders of the site Archive of Our Own, where people post and read fan fiction. Francesca was such a great source of information that I always regretted the fascinating parts of our interview which ended up on the proverbial cutting room floor. So this week, I'm featuring a full version of that conversation because her argument about the gendered ways in which SF gets judged is more relevant than ever.

#*#here have a podcast about the history of fanfic#along with a request that you not be a dick to the fic writers in this fandom#or any fandom#kthxbai#imaginary worlds

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 11 Act of Literary Creation

This week we watched Ruby Sparks for the subject of Literary creation and the movie explores that. A young acclaimed writer has been struggling to follow up the success of his first book. He starts writing about a woman in his imagination and she becomes his ideal girlfriend. His creation then comes to life as a living person and he starts to live out his fantasy. I thought this movie was interesting because it explores this idea of how having the perfect person can be a gift and a curse at the same time. Also, it shows how having perfect person in your imagination will still fall short of your standards. Later in the movie he starts to get more attached to Ruby that he cannot fathom being away from her.

We read two articles for this week and they both perfectly relate to subject at hand. The first one by Shelly Cobb is discussing the subject of fidelity in literature and the criticism that it receives. This is explored throughout the article as it relates to adaptation and being true to an original source. Often times a adaptation can be criticized for not being true to the original source and it takes place in public discourse. "The public trial for film adaptations takes place within the public discourse of newspaper, magazine, television, and new media reviews and in academic articles and books that inveigh against the film’s adulterous tendencies, using various terms for being inconstant, disloyal, untrue, false, a cheat, and a betrayal, words that recent scholarship insistently and rightly reject." (Cobb) The article also goes into the same but from a standpoint of how we discuss feminine stand point.

Francesca Coppa writes about fan fiction in the first chapter of her book. She breaks down all elements what makes fan fiction. The first is that it is created by people who are outsiders to the literary world. It also reimagines other stories that already exist but in mind of fan of the original story and it reimagines stories written by that author. It is also inspired by a fandom that exists and is made to cater to that fandom. Finally, it is more speculative fiction about a character or story as opposed to the universe. The one it is not made for nothing since the authors still see a profit in made fan fiction.

0 notes

Note

Hi! So I just read that one post by three-rings about why women like gay romance, and since I've had so many fights with a friend of mine about this, I wondered if you have some input: Basically, her argument is that it doesn't matter why women like to read gay romance, because it fetishizes gay men in such a way that the fact that gay men exist in the real world and are not represented faithfully by these books, gets ignored. Basically, cis (sometimes straight) women 'take away' representation?

Well, answer #1 is: “What the actual fuck does FETISHIZE mean anyway?”

On Tumblr, no one can answer this properly, and it always turns into “Girls have pants feelings, and that’s not okay.”

Women have a right to a fantasy life. Sometimes, those barbie dolls we’re dressing up look like men. Big whoop.

Answer #2 is: “Do you watch Drag Race?”

The answer is basically always yes. Women who shit on other women for liking slash are aaaaaaall over misogynist gay male appropriation from women. Because things men do are original and creative, but things women do are stealing, and we should go caretake instead of having hobbies.

The reality is that it is fine, healthy, and desirable to have an outlet for your inner feelings that is not a direct and literal representation of your outer form. “Representation” is much more complicated than “Their face looks like mine”.

For more on this, she could read David Halperin’s book How to be Gay or Francesca Coppa’s book chapter I linked to in that other post, which draws the very obvious analogy between Halperin’s work and slash fandom.

Answer #3 is that the vast majority of professional queer media used to be by, for, and about cis gay men. Now, that media still exists, but there’s also this other set of media which is m/m by and for AFAB people (not all of us women). We have not taken anything away. We have simply made media for ourselves.

But women aren’t allowed to do things for ourselves, only for others, so this is a problem.

Cis gay men still make their cis gay man media. It looks like cis straight man media except that the token love interest is a hot guy with no personality instead of a hot girl with no personality. And there are more dick measurements.

Okay, okay, cis gay men also write lots of depressing literary stuff about the pain of being a minority. Yay.

Women invented slash fandom. Previously, there was nothing. Then we made a thing. Literally no territory was stolen from queer men.

These dumb arguments are usually coming from cis women white knighting for cis gay men (who don’t give two shits about this debate and are busy watching gay porn on pornhub, not arguing about text romance novels). A few are coming from trans men who resent that their preferred media is mostly made by chicks.

For more on this, she should read this take on m/m romance as a professional industry by one of the few authors I think is probably not lying about being a cis man. His analysis is that there would not be any m/m romance novels if female authors in slash fandom had not caused there to be a market for pro work.

https://jamiefessenden.com/2014/06/28/my-take-on-women-writing-mm-romance/

Your friend is a misogynist asshole pulling a Not Like The Other Girls. Maybe one day she’ll get her head out of her ass. It’s a phase a lot of us go through, and misogynist culture rewards us for shitting on other women, so it can be hard to realize that’s what one is doing.

128 notes

·

View notes