#inuhiko yomota

Text

書物は声だな

わたしはこのフィルムに非常に感動しました。「そうか、書物のない世界になってしまったら、人間が書物になるしかないんだ」と。いろいろな人たちが次々と声を出し、自分自身を語っている・・・・・・その映像を見て、「書物は声だな」とつくづく思いましたね。情報量のない書物はダメだと思いますが、にもかかわらず、書物は情報の束ではないのです。

『人間を守る読書』

四方田犬彦<著>

文春新書

0 notes

Text

Tomino no Jigoku.

Su hermana mayor vomitó sangre, su hermana menor vomitó fuego.

Y el lindo tómino vomitó cuentas de vidrio.

Tomino cayó al infierno solo.

El infierno está envuelto en oscuridad, e incluso las flores no crecen.

¿Es la persona con el látigo la hermana mayor de Tomino?

Me pregundo de quién será ese látigo.

Golpea, golpea, sin golpear.

Un solo camino del infierno familiar.

Lo guiarias al oscuro infierno?

Hacía la oveja de oro? hacia el ruiseñor?

Me pregunto cuánto habrá puesto en el bolsillo de cuero.

Para la preparación del viaje por el infierno familiar.

La primavera llega incluso en el bosque y vapor.

Incluso en el vapor del oscuro infierno.

El ruiseñor en la jaula, la oveja en el carro.

Lagrimas en los ojos del lindo Tomino.

Llora, ruiseñor, por el bosque lluvioso.

Sus gritos de que ha perdido a su pequeña hermana.

El llanto reberveró por todo el infierno.

Los pimpollos de peonias.

Haciendo círculos en torno a las siete montañas y a las siete corrientes del infierno.

El viaje solitario del lindo Tomino.

Si están en el infierno, traemelos.

La aguja de las tumbas.

No voy a perforarlos con la aguja roja.

En el hito del pequeño Tomino.

Yomota Inuhiko 1919?

#textos#escritos#Tomino#tomino's hell#Yomota Inuhiko#adios#infierno#soledad#peonia#dead roses#death#red roses#rose 🌹

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

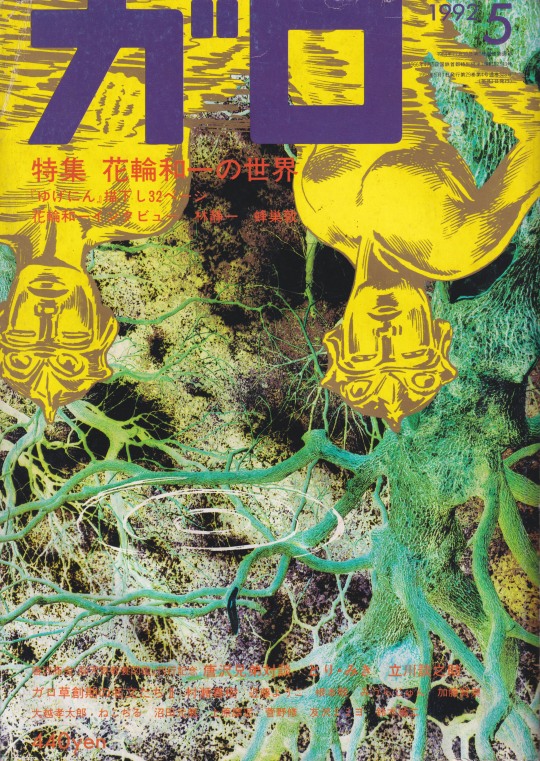

Garo 1992-05 has been scanned by Choolete and is uploading here.

Contains an interview with Kazuichi Hanawa.

1992-05 328 [表紙] ヒョウシ [Cover] Front cover

1992-05 328 [目次] モクジ [Table of Contents] Editor's Announcements

1992-05 328 [インタビュー/対談/座談会] インタビュータイダンザダンカイ [Interview / Dialogue / Roundtable] Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 花輪和一 Kazuichi Hanawa ゆげにん ユゲニン Yugenin Manga works

1992-05 328 蜂巣敦 蜂巣敦 因果の破壊者、花輪和一 インガノデストロイヤーハナワカズイチ Kazuichi Hanawa, the destroyer of causality Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 林静一 Seiichi Hayashi 黒っぽいコマ絵 クロッポイコマエ Blackish frame picture Manga works

1992-05 328 鈴木翁二 Oji Suzuki 少年存在学ノート ショウネンソンザイガクノート Boy Existence Notebook Manga works

1992-05 328 唐沢俊一/唐沢なをき 唐沢俊一/唐沢なをき 失われたギャグを求めて ウシナワレタギャグヲモトメテ In search of the lost gag Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 唐沢俊一 唐沢俊一 脳天気教養図鑑拾遺 ノウテンキキョウヨウズカンシュウイ Collection of brain weather culture pictorial book Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 唐沢なをき 唐沢なをき よくわかる小6理科 ヨクワカルショウ6リカ Easy-to-understand small 6 science Manga works

1992-05 328 立川談之助 立川談之助 怪人 唐沢俊一 カイジンカラサワシュンイチ Phantom Shunichi Karasawa Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 鹿野景子 鹿野景子 唐沢兄弟の秘密 カラサワキョウダイノヒミツ The secret of the Karasawa brothers Manga works

1992-05 328 とり・みき とり・みき 戦友に愛をこめて センユウニアイヲコメテ With love for your comrades Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 礒田ゆり子 礒田ゆり子 覗き ノゾキ Peep Manga works

1992-05 328 安彦麻理絵 安彦麻理絵 寝すごした朝 ネスゴシタアサ Morning spent sleeping Manga works

1992-05 328 泉晴紀 泉晴紀 うきーで一発 ウキーデイッパツ One shot at Uki Manga works

1992-05 328 上原摩泥 上原摩泥 NO NO NO 霊脳サイバネKID NONONOレイノウサイバネKID NO NO NO Rei Brain Cybernetics KID Manga works

1992-05 328 杉作J太郎 Jeitarô Sugisaku 宇宙縁談ゴリ・激突篇 ウチュウエンダンゴリゲキトツヘン Space Marriage Gori / Crash Hen Manga works

1992-05 328 杉作J太郎 Jeitarô Sugisaku ギャンブル新聞 ギャンブルシンブン Gambling newspaper Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 友沢ミミヨ 友沢ミミヨ だーるまさんがころんだ ダールマサンガコロンダ Daruma-san fell Manga works

1992-05 328 沼田元氣 Genki Numata 憩写真帖 イコイシャシンチョウ Rest Photo Album Photographs and gravures

1992-05 328 Q.B.B. Q.B.B. オトナは37564 オトナハ37564 Adults are 37564 Manga works

1992-05 328 松井雪子 松井雪子 アパート夫人 アパートフジン Mrs. Apartment Manga works

1992-05 328 みうらじゅん Jun Miura アイデン&ティティ アイデン&ティティ Aiden & Titi Manga works

1992-05 328 ねこぢる ねこぢる ねこぢるうどん ネコヂルウドン Nekojiru Udon Manga works

1992-05 328 菅野修 Osamu Kanno 幻のゆくえ マボロシノユクエ Whereabouts of the illusion Manga works

1992-05 328 加藤賢崇 加藤賢崇 がんばれ!いぬちゃん ガンバレイヌチャン Good luck! Inu-chan Manga works

1992-05 328 三本義治 三本義治 淘太でドーダ トウタデドーダ Doda at Shouta Manga works

1992-05 328 近藤ようこ 近藤ようこ 妖霊星 ヨウレイセイ Youkai Star Manga works

1992-05 328 大越孝太郎 Kotaro Ogoshi 星にねがいを ホシニネガイヲ Give a wish to the stars Manga works

1992-05 328 大越孝太郎 Kotaro Ogoshi パノラマ大百貨店 パノラマダイヒャッカテン Panorama Department Store Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 イタガキノブオ Itaga Kinobuo ヴァリアント ヴァリアント Variant Manga works

1992-05 328 中ザワヒデキ 中ザワヒデキ しーじー少女椿 シージーショウジョツバキ Shiji Shoujo Tsubaki Manga works

1992-05 328 三橋乙揶 Mihashi Otoko OM短報号外 OMタンポウゴウガイ OM Extra Special Feature Articles

1992-05 328 土橋とし子 土橋とし子 青空脳天満腹画報 アオゾラノウテンマンプクガホウ Blue Sky Brain Tenman Stomach Pictorial Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 [特集] トクシュウ [Special feature] Special Feature Articles

1992-05 328 特殊漫画博覧会記念・根本敬・関西紀行(抄) 梵悩・悟り・宇宙、そしてコンビニエンス トクシュマンガハクランカイキネンネモトタカシカンサイキコウショウボンノウサトリウチュウソシテコンビニエンス Special Comic Exhibition Memorial, Takashi Nemoto, Noriyuki Kansai (Excerpt) Anxiety, Enlightenment, Space, and Convenience Special Feature Articles

1992-05 328 MEGARO MIX MEGAROMIX MEGARO MIX Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 四方田犬彦 Inuhiko Yomota 犬も歩けば イヌモアルケバ If the dog walks too Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 久住昌之 Masayuki Kusumi 出たとこ勝ぶ デタトコショウブ Win when it comes out Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 高杉弾 Dan Takasugi 倶楽部イレギュラーズ クラブイレギュラーズ Club Irregulars Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 松沢呉一 Kureichi Matsuzawa 飲尿自転車男業界漫遊記 インニョウジテンシャオトコギョウカイマンユウキ Urophagia Bicycle Man Industry Manyuuki Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 上野昂志 Koshi Ueno 黄昏映画館 タソガレエイガカン Twilight cinema Novels and reading materials

1992-05 328 読者サロン ドクシャサロン Reader Salon Submission Page

43 notes

·

View notes

Link

Halloween Day Three

I am not the biggest Creepypasta fan, probably because I am old, but there are a few of them that I find irresistibly disturbing and peculiar. Tomino’s Hell, amongst the more famous, is one of them.

Tomino’s Hell is a poem by Saizo Yaso, published in 1919 about a little boy traveling through Buddhist hell. In the early 70s a movie inspired by it was made, and the director/writer died sometime after, leading to rumor that the poem would curse anyone who read it aloud.

Around 2018 it became a Creepypasta and there were scads of videos of people reading the poem aloud on line. Mostly in Japanese, which seems to be a requirement for the curse to be activated. As to what happened to the readers? Who can say?

There is something about this poem. Maybe the clearly fake legend around it, maybe that it is about a child going through hell, maybe the simple, slightly singsong rhythm that is clear even in translation. Something about it unsettles me, which is almost better than fear.

Here, for the brave amongst you, is Tomino’s Hell - translated to English - which even if it isn’t cursed, isn’t exactly pleasant. If you do decide to read it outloud please let me know if anything interesting happens.

Tomino’s Hell

Elder sister vomits blood,

younger sister’s breathing fire

while sweet little Tomino

just spits up the jewels.

All alone does Tomino

go falling into that hell,

a hell of utter darkness,

without even flowers.

Is Tomino’s big sister

the one who whips him?

The purpose of the scourging

hangs dark in his mind.

Lashing and thrashing him, ah!

But never quite shattering.

One sure path to Avici,

the eternal hell.

Into that blackest of hells

guide him now, I pray—

to the golden sheep,

to the nightingale.

How much did he put

in that leather pouch

to prepare for his trek to

the eternal hell?

Spring is coming

to the valley, to the wood,

to the spiraling chasms

of the blackest hell.

The nightingale in her cage,

the sheep aboard the wagon,

and tears well up in the eyes

of sweet little Tomino.

Sing, o nightingale,

in the vast, misty forest—

he screams he only misses

his little sister.

His wailing desperation

echoes throughout hell—

a fox peony

opens its golden petals.

Down past the seven mountains

and seven rivers of hell—

the solitary journey

of sweet little Tomino.

If in this hell they be found,

may they then come to me, please,

those sharp spikes of punishment

from Needle Mountain.

Not just on some empty whim

Is flesh pierced with blood-red pins:

they serve as hellish signposts

for sweet little Tomino.

—translated by David Bowles

June 29, 2014

Let me know if you want to be added to my taglist!

@joyfullymassivewhispers @caffiend-queen @myoxisbroken @dangertoozmanykids101 @toozmanykids @punemy-spotted @stupendouslovegardener @sylviefromneptune

18 notes

·

View notes

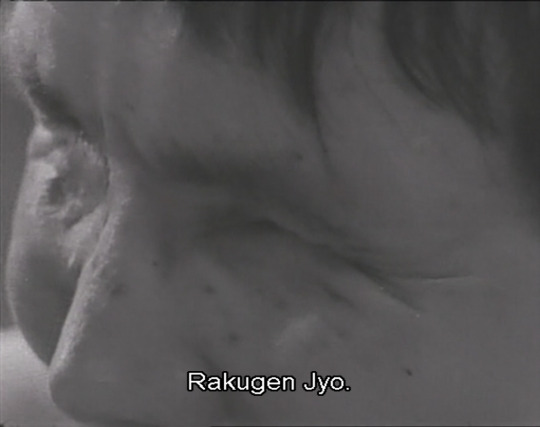

Photo

Now if tears come to the eyes, if they well up in them, and if they can also veil sight, perhaps they reveal, in the very course of this experience, in this coursing of water, an essence of the eye, of man’s eye . . . Deep down, deep down inside, the eye would be destined not to see but to weep. For at the very moment they veil sight, tears would unveil what is proper to the eye. . . . only man knows how to go beyond seeing and knowing [savoir], because only he knows how to weep. . . . Only man knows how to see this [voir ça] – that tears and not sight are the essence of the eye. . . .Contrary to what one believes one knows, the best point of view (and the point of view will have been our theme) is a source-point and a watering hole, a water-point – which thus comes down to tears.

-- Jacques Derrida / Memoirs of the Blind: The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins

Nagisa Oshima

- The Forgotten Imperial Army

1963

#nagisa oshima#Wasurerareta kogun#the forgotten imperial army#the forgotten army#大島渚#ノンフィクション劇場#忘れられた皇軍#jacques derrida#memoirs of the blind#Memoirs of the Blind: The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins#blind#tear#eye#sight#documentary#1963#四方田犬彦#inuhiko yomota#大島渚と日本#nagisa Ōshima#sozosha#創造社#japanese film

228 notes

·

View notes

Photo

真夜中のミサ ポール・ボウルズ作品集Ⅱ

ポール・ボウルズ、越川芳明・訳

四方田犬彦・越川芳明[編]

白水社

装幀=伊勢功治、カバー写真=オノデラユキ

#midnight mass#真夜中のミサ#真夜中のミサ ポール・ボウルズ作品集Ⅱ#paul bowls#ポール・ボウルズ#yoshiaki koshikawa#越川芳明#inuhiko yomota#四方田犬彦#koji ise#伊勢功治#yuki onodera#オノデラユキ#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#book cover

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Issei Sagawa, The Japanese Celebrity Cannibal

On 11 June 1981, Sagawa, then 32, invited his Sorbonne classmate Renée Hartevelt, a Dutch woman, to dinner at his apartment at 10 Rue Erlanger, under the pretext of translating poetry for a school assignment. Sagawa planned to kill and eat her, having selected her for her health and beauty - characteristics he felt he lacked. Sagawa considered himself weak, ugly, and small (he was 144.8 cm (4 ft 9 in) tall) and claims he wanted to absorb her energy. She was 25 years old and 178 cm (5 ft 10 in). After Hartevelt arrived, she began reading poetry at a desk with her back to Sagawa when he shot her in the neck with a rifle. Sagawa said he fainted after the shock of shooting her, but awoke with the realization that he had to carry out his plan. Sagawa had sex with her corpse but he could not bite into her skin because his teeth were not sharp enough, so he left the apartment and purchased a butcher knife. Sagawa consumed various parts of Hartevelt's body, eating most of her breasts and face either raw or cooked, while saving other parts in his refrigerator. Sagawa also took photographs of Hartevelt's body at each eating stage. Sagawa then attempted to dump the remains of Hartvelt's corpse in a lake in the Bois de Boulogne, carrying her dismembered body parts in two suitcases, but was caught in the act and arrested by French police four days later.

Sagawa's wealthy father provided a lawyer for his defense, and after being held for two years awaiting trial, Sagawa was found legally insane and unfit to stand trial by the French judge, Jean-Louis Bruguière, who ordered him held indefinitely in a mental institution. After a visit by the author Inuhiko Yomota, Sagawa's account of his kill was published in Japan under the title In the Fog. Sagawa's subsequent publicity and macabre celebrity likely contributed to the French authorities' decision to deport him to Japan, where he was immediately committed to Matsuzawa Hospital in Tokyo. His examining psychologists all declared him sane and found sexual perversion was his sole motivation for murder. As the charges against Sagawa in France had been dropped, the French court documents were sealed and were not released to Japanese authorities; consequently Sagawa could not legally be detained in Japan. Sagawa checked himself out of the hospital on 12 August 1986, and has subsequently remained free since that day. Sagawa's continued freedom has been widely criticized.

In 2013, Sagawa was hospitalized from a cerebral infarction, which permanently damaged his nervous system. He now lives alone and needs daily assistance, which is provided by his younger brother or from caregivers.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese Cannibal Killer Walking Free…

By: Keeleigh Lennon

Summary

Issei Sagawa is a Japanese man (born on June 11, 1949) who murdered and devoured a Dutch woman (Renée Hartevelt) in 1981.

Early Life

Born to wealthy parents, Sagawa was very well off. Sagawa's father (Akira Sagawa) was a businessman who had served as president of Kurita Water Industries, and his grandfather had been an editor for The Asahi Shimbun. Sagawa was born prematurely leading to a disease of the small intestine. This disease was eventually gotten under control after several injections of potassium and calcium in saline. Due to this health issue though, his health remained fragile. Sagawa, with his already fragile medical state, was also very introverted, leading to a strong interest in literature. Sagawa first experienced these cannibalistic desires when he attended first grade. It is said he saw a mans thigh and imagined "taking a piece of it."

First Attempt

At the age of 24, while attending university in Tokyo, Sagawa planned to cannibalize a fellow German classmate by slicing off part of her buttocks. With this intention, Sagawa followed the tall German woman home, then broke into her apartment while she was sleeping. Fortunately, she woke up and pushed him to the ground. Police captured Sagawa and was charged with attempted rape of the woman. These charges were eventually dropped when Sagawa's father paid off the victim.

The Urges Grew Stronger

Later, at the age of 27, Sagawa moved to France to pursue a Ph.D. in literature at the Sorbonne in Paris. Sagawa claims that while living in Paris he would bring a prostitute home almost every night and try to shoot them. Luckily for them, he couldn't bring himself to pull the trigger.

The Killing of Renée Hartevelt

On June 11, 1981, Sagawa, 32 at the time, Invited his Classmate Renée Hartevelt to dinner, claiming to discuss some poetry assignment for their school. Sagawa claims he chose Hartevelt to kill and eat because of her health and beauty, which he felt he lacked. He wanted to "absorb her energy." As soon as Hartevelt arrived, she sat at a desk and began reading her poetry with her back to Sagawa. He then shot her in the neck with a rifle. Sagawa states that he fainted due to shock after shooting her, but soon awoke realizing that he had to actually follow through with his plan. Sagawa had sexual relations with her corpse and attempted to bite off her skin, but his teeth were not sharp enough. Needing to fulfill his cannibalistic urges, Sagawa purchased a butcher knife and consumed various parts of Hartevelt's body. He ate most of her breasts and face, both raw or cooked, while keeping other body parts in the refrigerator.

Very Graphic Warning

(Photograph taken by Sagawa on left, and the body of Hartevelt on the right)

Attempted Disposal Leading to Capture

Sagawa attempted to dispose of Hartevelt's remains in a lake, carrying her dismembered body parts in two suitcases. Sagawa was caught in the act and arrested by French police four days later.

Trial

Sagawa's wealthy father provided a lawyer in his defense, and after awaiting trial for two years, Sagawa was found legally insane and unfit to stand trial by a French judge. He was then ordered to be indefinitely held in a mental institution.

Transfer Back to Japan

After a visit from author Inuhiko Yomota, Sagawa's story was published in Japan under the title In the Fog. Sagawa's publicity and fame likely contributed to his deportation back to Japan. Once arrived to Japan, he was immediately committed to Matsuzawa Hospital in Tokyo. All of his examining psychologists found him to be sane and claimed that his sole motivation for the murder was his sexual perversion. As the charges against Sagawa were dropped in France, the case was sealed and not released to authorities in Japan. Making it impossible to legally detain Sagawa. On August 12, 1986, Sagawa checked himself out of the hospital and has remained free although widely criticized.

Present Day

In 2013, Sagawa was hospitalized from a cerebral infarction, which has left him with a permanent nervous system issue. He now lives alone and needs daily assistance, which is provided by his younger brother or other caregivers.

Thanks so much for reading my story! If you enjoyed, make sure to tune in next Wednesday for another story. Also DM me on Instagram @crimecellar for any story requests. I love hearing from all of you. Until next week...stay safe out there.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

トミノの地獄 by 四方田 犬彦 (Tomino's Hell)

The death poem (Tomino's Hell - El infierno de Tomito - トミノの地獄) is a Japanese poem written by Yomota Inuhiko (四方田犬彦) in 1919 in the book of poems "The heart is like a rolling stone". (The heart is like a rolling stone - 心は転がる石のように)

According to the same poem it said that if it was recited aloud you could have some kind of accident, but in most cases death would come to the unwary who dared to do so.

It was not so well recognized until a few years ago a Japanese radio host who was dedicated to paranormal phenomena began to read it for all listeners, although he only read half of it. Days later, the announcer was injured, even having to put stitches on him.

The poem in question can be easily found on the Internet, both in its original version and in Spanish, although it is true that there are some who say it is not the original.

The story became popular on the Japanese website 2ch, where multiple users posted photos and videos of themselves reading the poem. There were many users who said that nothing happened, but there were also several topics in which the user did not return to communicate the results.

Romanized Japanese

姉は血を吐く、妹(いもと)は火吐く、

ane wa chi wo haku, imoto wa hihaku

可愛いトミノは 宝玉(たま)を吐く。

kawaii tomino wa tama wo haku

ひとり地獄に落ちゆくトミノ、

hitori jihoku ni ochiyuku tomino

地獄くらやみ花も無き。

jigoku kurayami hana mo naki

鞭で叩くはトミノの姉か、

muchi de tataku wa tomino no aneka

鞭の朱総(しゅぶさ)が 気にかかる。

muchi no shubusa ga ki ni kakaru

叩けや叩きやれ叩かずとても、

tatake yatataki yare tataka zutotemo

無間地獄はひとつみち。

mugen jigoku wa hitotsu michi

暗い地獄へ案内(あない)をたのむ、

kurai jigoku e anai wo tanomu

金の羊に、鶯に。

kane no hitsu ni, uguisu ni

皮の嚢(ふくろ)にやいくらほど入れよ、

kawa no fukuro ni yaikura hodoireyo

無間地獄の旅支度。

mugen jigoku no tabishitaku

春が 来て候(そろ)林に谿(たに)に、

haru ga kitesoru hayashi ni tani ni

暗い地獄谷七曲り。

kurai jigoku tanina namagari

籠にや鶯、車にや羊、

kagoni yauguisu, kuruma ni yahitsuji

可愛いトミノの眼にや涙。

kawaii tomino no me niya namida

啼けよ、鶯、林の雨に

nakeyo, uguisu, hayashi no ame ni

妹恋しと 声かぎり。

imouto koishi to koe ga giri

啼けば反響(こだま)が地獄にひびき、

nakeba kodama ga jigoku ni hibiki

狐牡丹の花がさく。

kitsunebotan no hana ga saku

地獄七山七谿めぐる、

jigoku nanayama nanatani meguru

可愛いトミノのひとり旅。

kawaii tomino no hitoritabi

地獄ござらばもて 来てたもれ、

jigoku gozarabamo de kitetamore

針の御山(おやま)の留針(とめはり)を。

hari no oyama no tomebari wo

赤い留針だてにはささぬ、

akai tomehari date niwa sasanu

可愛いトミノのめじるしに。

kawaii tomino no mejirushini

Continue reading:

English links

- https://horrorobsessive.com/2020/08/18/tominos-hell-the-cursed-poem-not-meant-to-be-read-out-loud/

- https://davidbowles.us/poetry/tominos-hell-by-saijo-yaso/

- https://indie88.com/tominos-hell-the-cursed-japanese-poem-you-shouldnt-read-out-loud/

Spanish links (Translate these sites)

- https://creepypasta.fandom.com/es/wiki/El_infierno_de_Tomino

- http://agorahabla.com/opinion/articulo/el-poema-de-la-muerte-tominos-hell-leyendas-urbanas-japonesas

- https://caracterurbano.com/literatura/poema-de-tomino

- https://k-magazinemx.com/asia/cultura/el-infierno-de-tomino-el-poema-maldito/

< - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - >

El poema de la muerte (El infierno de Tomino - El infierno de Tomito - トミノの地獄) es un poema japonés escrito por Yomota Inuhiko (四方田犬彦) en 1919 en el libro de poemas "El corazón es como una piedra rodante". (El corazón es como una piedra rodante - 心は転がる石のように)

Según el mismo poema decía que si se recitaba en voz alta se podía tener algún tipo de accidente, pero en la mayoría de los casos la muerte le llegaría al incauto que se atreviera a hacerlo.

No fue tan reconocido hasta hace unos años un locutor de radio japonés que se dedicaba a los fenómenos paranormales comenzó a leerlo para todos los oyentes, aunque solo leyó la mitad. Días después, el locutor resultó herido, debiendo incluso ponerle puntos de sutura.

El poema en cuestión se puede encontrar fácilmente en Internet, tanto en su versión original como en español, aunque es cierto que hay quienes dicen que no es el original.

La historia se hizo popular en el sitio web japonés 2ch, donde varios usuarios publicaron fotos y videos de ellos mismos leyendo el poema. Hubo muchos usuarios que dijeron que no pasó nada, pero también hubo varios temas en los que el usuario no volvió a comunicar los resultados.

Japonés romanizado

姉は血を吐く、妹(いもと)は火吐く、

ane wa chi wo haku, imoto wa hihaku

可愛いトミノは 宝玉(たま)を吐く。

kawaii tomino wa tama wo haku

ひとり地獄に落ちゆくトミノ、

hitori jihoku ni ochiyuku tomino

地獄くらやみ花も無き。

jigoku kurayami hana mo naki

鞭で叩くはトミノの姉か、

muchi de tataku wa tomino no aneka

鞭の朱総(しゅぶさ)が 気にかかる。

muchi no shubusa ga ki ni kakaru

叩けや叩きやれ叩かずとても、

tatake yatataki yare tataka zutotemo

無間地獄はひとつみち。

mugen jigoku wa hitotsu michi

暗い地獄へ案内(あない)をたのむ、

kurai jigoku e anai wo tanomu

金の羊に、鶯に。

kane no hitsu ni, uguisu ni

皮の嚢(ふくろ)にやいくらほど入れよ、

kawa no fukuro ni yaikura hodoireyo

無間地獄の旅支度。

mugen jigoku no tabishitaku

春が 来て候(そろ)林に谿(たに)に、

haru ga kitesoru hayashi ni tani ni

暗い地獄谷七曲り。

kurai jigoku tanina namagari

籠にや鶯、車にや羊、

kagoni yauguisu, kuruma ni yahitsuji

可愛いトミノの眼にや涙。

kawaii tomino no me niya namida

啼けよ、鶯、林の雨に

nakeyo, uguisu, hayashi no ame ni

妹恋しと 声かぎり。

imouto koishi to koe ga giri

啼けば反響(こだま)が地獄にひびき、

nakeba kodama ga jigoku ni hibiki

狐牡丹の花がさく。

kitsunebotan no hana ga saku

地獄七山七谿めぐる、

jigoku nanayama nanatani meguru

可愛いトミノのひとり旅。

kawaii tomino no hitoritabi

地獄ござらばもて 来てたもれ、

jigoku gozarabamo de kitetamore

針の御山(おやま)の留針(とめはり)を。

hari no oyama no tomebari wo

赤い留針だてにはささぬ、

akai tomehari date niwa sasanu

可愛いトミノのめじるしに。

kawaii tomino no mejirushini

Sigue leyendo:

Enlaces en ingles (Traducir estos sitios)

- https://horrorobsessive.com/2020/08/18/tominos-hell-the-cursed-poem-not-meant-to-be-read-out-loud/

- https://davidbowles.us/poetry/tominos-hell-by-saijo-yaso/

- https://indie88.com/tominos-hell-the-cursed-japanese-poem-you-shouldnt-read-out-loud/

Enlaces en español:

- https://creepypasta.fandom.com/es/wiki/El_infierno_de_Tomino

- http://agorahabla.com/opinion/articulo/el-poema-de-la-muerte-tominos-hell-leyendas-urbanas-japonesas

- https://caracterurbano.com/literatura/poema-de-tomino

- https://k-magazinemx.com/asia/cultura/el-infierno-de-tomino-el-poema-maldito/

#poetic#poems on tumblr#tomino's hell#cursed#cursed poem#interesting#everything#links#creppy#legend#poetry#poesia#poema#horror#maldición#poesía#el infierno de tomito#interesante#leyenda#español#english

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tomino's Hell

"The Poem You Should Never Read Aloud"

A writer named Yomota Inuhiko once wrote a poem called "Hell of Tomino." There is a legend that anyone who reads the poem aloud will face something terrible.

If there's one thing the Japanese are known for, it's scary stories.

I've always liked everything that includes the words "horror" and "thriller", but this poem definitely shook me to the core.

"Hell of Turin" was written in the book "The Heart is Like a Moving Stone", and then included in the book by Saijo Yaso, the twenty-seventh collection of poems in 1919, and now let's look at the poem itself. * translated, the poem does not pose any danger *

The older sister vomits blood, the younger sister breathes fire.

While the cute little Tomino just spits out the jewelry.

All by himself, Tomino falls into that hell, a hell of complete darkness, without even flowers. Is Tomino's older sister the one whipping him?

The purpose of the flogging hangs dark in his mind.

To beat him and beat him, ah!

But it never hurts him.

A safe path to Avici, eternal hell.

In this darkest hell I direct it now, I pray to the golden sheep, to the nightingale. How much did he put in that leather bag to prepare for his journey to eternal hell?

Spring comes in the valley, in the forest, in the spiral precipices of the blackest hell. The nightingale in her cage, the sheep on board the van, and tears invade the sweet little Tomino's eyes.

Sing, O nightingale, in the vast, misty forest he shouts that only his little sister is missing.

His weeping despair echoes through hell - a fox peony opens its golden petals.

Down the seven mountains and the seven rivers of hell, the lonely journey of the sweet little Tomino.

If they are found in this hell, let them then come to me, those sharp jumps of punishment from Needle Mountain.

Not only on some empty whim the flesh is pierced with blood-red pins:

they serve as hellish pointers for the sweet little Tomino.

#novel writing#art#storytelling#story#long reads#writer#read more#creepypasta#anime#follow#likeback#comment reply#commentforcomment#torino#japan

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books read so far during while cooped up:

Woman in the Dunes by Kobo Abe: haven’t watched the movie yet. the book was okay, a bit disappointing, although some of that may have been due to the translation by e. dale saunders; the prose was sometimes a slog, but mostly it’s incredibly effective at conveying the incredibly unpleasant experience of sand covering your skin and clogging every orifice and being held against your will and heat and thirst. abe doesn’t seem to be a huge fan of women.

The Plague by Albert Camus: really good. much more plot driven than the stranger or the fall, fairly reassuring at the moment as it reminds you that none of these experiences are new and in the face of horror and sickness people have banded together and done what needs doing (another difference from the stranger and the fall is the growing sense of community and friendship experienced by the characters as they work with each other to fight the plague); it’s also pretty funny.

What Is Japanese Cinema? A History by Yomota Inuhiko: the book covers more than a century of japanese cinema in about 200 pages, so it doesn’t go into great depth, but it’s a useful and very readable primer on the decade by decade trends of the film industry in japan, it’s literary and theatrical roots, the territory and signature filmmakers of each studio, etc. it gives you lots of things to research further.

The Loved One by Evelyn Waugh: i watched the film adaptation of this a little while ago and was disappointed (although haskell wexler’s widescreen b&w cinematography is worth seeking out the film for) but i knew it was a departure from the book that fans of the book were generally not into so i hoped the book would be better. the book was also a disappointment, although at least it’s a bit nastier and meaner than the film. wikipedia says that the new yorker declined to publish it because they felt the territory had already been covered better by satirists like nathanael west (the loved one pokes fun a hollywood and advice columnists, the subjects of the day of the locust and miss lonelyhearts respectively). i’m inclined to agree; the loved one is shooting fish in a barrel, but you get the sense that waugh, being among the snobbiest of english snobs, didn’t care to learn about americans during his visit to hollywood so he doesn’t know enough to be able to do anything but graze the fish in the barrel. it goes for shocks; it barely elicited a shrug. at least it’s short, but just read miss lonelyhearts and day of the locust instead (they’re also short and have retained their essential ugliness and intensity, especially miss lonelyhearts, in spite of being older than the loved one),

On Parole by Akira Yoshimura: helped by a good translation, a very stripped down story of a man paroled after 16 years in prison and his attempts to readjust to life outside. he was given an indefinite sentence (basically a life sentence) so even though he’s out of prison, he’ll spend the rest of his life on parole. quick, gripping read. went into it knowing nothing about it (got it for $1 at a library book sale) and was pleasantly surprised. apparently shohei imamura’s film the eel (which tied for the palme d’or with taste of cherry) is “inspired by” on parole, although nothing i know about the eel sounds like it has much to do with on parole; from the wikipedia synopsis of the eel it sounds like the opening of the film has the protagonist committing a similar (but not the same) crime and then it picks up with him being paroled before the rest of the movie turns into something entirely different.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

TOMİNO NUN CEHENNEMI

Şiir okumayı seviyorsunuz ve Yomota Inuhiko nun "Tomino nun Cehennemi" adlı şiiri okumak istediniz. Eğer sesli bir şekilde olursanız ya ölürsünüz ya da başınıza büyük bir felaket gelir . Tabiki bu bir söylenti ama siz bu riski almayın.

Ablası kan kustu, kız kardeşi alev

Ve sevimli Tomino da cam bilyeler

Tomino cehenneme tek başına düştü

Cehennem karanlığa sarınmıştı, çiçekler dahi açmıyordu hatta

Şu kamçılı kişi Tomino'nun ablası mı

Kamçısının hedefi kim acaba

Vur, vur hiç durmadan

Tanıdık Cehennem tek bir yol

Ona karanlık cehennemde eşlik eder miydin

Altın koyuna, çalı bülbülüne

Deriden cebine ne kadar koydu acaba

Bu tanıdık cehenneme giden yolculuk için

Ormana da ırmağa da geliyor bahar

Hatta karanlık cehennemin ırmağına da

Kafesteki çalı bülbülü, yük arabasındaki koyun

Sevimli Tomino'nun gözlerindeki yaşlar

Ağla çalı bülbülü, yağmur yağan ormana doğru

Kız kardeşini özlediğini söylüyor

Ağlayan çığlıkları cehennemde yankı yapıyor

Tilki şakayıkları açıyor

Cehennemin yedi dağı ve ırmağını dolaşır

Sevimli Tomino'nun yalnız yolculuğu

Eğer cehennemdelerse getir onları bana

Mezarlardaki iğneleri.

Kırmızı iğneyle işaretlemeyeceğim

Sevimli Tomino'nun hedeflerini

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Godzilla [1954] was made at a time of rising anti-American sentiment. A flood of popular novels and magazines critical of American policy, as well as radio programs and newsreels, had appeared after the Occupation. There were 210,000 US troops stationed in Japan, and accounts of GIs and ex-servicemen committing rape, murder, and other crimes with impunity fanned the flames of resentment; anti-US views were espoused by college students and conservative politicians alike. Several Japanese movies exposed the ugly American and his arrogance; even [Ishiro] Honda's Young Tree and Inao would make brief asides on the subject a few years later. Simultaneously, the Americanization of Japanese populat culture that began in the 1920s continued, as youths embraced American fashion, jazz music, and movies. And the surging economic recovery was dependent on America, which was Japan's primary trade and also using its influence to help Japan enter European markets.

Yet, despite the tremendous shadow it cast, America is conspicuously absent from Godzilla. International advisers arrive in Tokyo; but except for several Caucasian faces in the back of the room, the West is invisible throughout the film. The American military's complete uninvolvement in the crisis might be interpreted as a reflection of national anxiety over the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, which was signed by Japan and Washington in September 1951. Known by the acronym AMPO in Japanese, the lopsided pact allowed the United States to keep military bases in Japan as an Asian bulwark against Soviet communism and required Japan to defray part of the cost. America was permitted to defend Japan against external threats and to suppress internal ones, yet the treaty did not explicitly guarantee protection by the US military, an omission that would make AMPO a political lightning rod for years. The treaty also remilitarized Japan by authorizing the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF), a contingent of 150,000 ground, sea, and air troops established in March 1954. Yet under Article 9 of Japan's US-written 1947 constitution, Japan had renounced "war as a sovereign right of the nation." There were concerns that the constitution prohibited Japan from defending itself, worries that the JSDF was too small and underequipped, and fears that America would not honor its role as Japan's primary defender. Notably, in the film Japan battles Godzilla without American help.

"The story proceeds as a purely domestic affair", notes historian Yoshikuni Igarashi. "Godzilla...is subsequently killed by Japanese without external assistance...In 1954, the concerted attack that the film portrays would have been possible only with the help of American forces. Nevertheless, the [Self-Defense Forces]...are solely responsible for the attacks against Godzilla. If the [monster] indeed embodied American nuclear threats, it is only logical that the Japanese forces alone should attack. The American forces by definition could not." Anxieties about national security are mirrored: Japan's fledgling military cannot halt the monster's massive onslaught, though fighter planes eventually succeed in driving it back to the sea, to the cheers of civilians. The EIRIN ratings board, in approving the screenplay on July 8, 1954, included a requirement that the film portray Japan's new military "with the upmost care and respect."

As Igarashi points out, "There is not even a hint of [American] responsibility in the...destruction of Tokyo by the monster." Godzilla's ties to the atomic bomb have nevertheless led some Western critics to mischaracterize Honda's film as anti-American. Several contemporary Japanese scholars, meanwhile, have interpreted Japan's military self-reliance and the monster's reenactment of wartime destruction as "ambivalent notions of nationalism and anti-nuclear ideology," writes critic Inuhiko Yomota. In recent decades, influential film scholars have interpreted Godzilla as evoking a powerful national trauma, with the monster symbolizing the restless ghosts of Japanese soldiers lost in the Pacific War, a concept inspired by the postwar essays of folklorist Kunio Yanagita. Among those popularizing this view is prominent critic Saburo Kawamoto, whose 1994 book Revisiting Postwar Japanese Film theorized that these souls had taken the form of Godzilla and returned; as evidence, Kawamoto offers the monster's deference to the prewar order. "Those who died in the war are still under the spell of Japan's emperor," Kawamoto writes, therefore "Godzilla cannot destroy the Imperial Palace."

However, Honda's own attitudes toward Godzilla, the bomb, America, and his own country are more nuanced and complex; the film is not an anti-US polemic but an even-handed treatment of the tenuous and asymmetrical Japan-US relationship, casting light on both the invisible hand of American hegemony and the spineless politicians who are more concerned about safeguarding Japan's client-state relationship with Washington than about the welfare of the nation. Just as some real-life leaders tried to downplay the Lucky Dragon incident, legislators move to suppress information about Godzilla's ties to the H-bomb, wary of antagonizing Uncle Sam. As Godzilla approaches Tokyo, one politician frets not about the threat to public safety, but to international shipping. Godzilla doesn't think much of national leadership. It demolishes the Diet building, Japan's equivalent of Capitol Hill.

Honda does not depict all Western influence, Occupation reforms, and new attitudes negatively. Women's suffrage was enacted in 1945, and the first female member of the Imperial Diet was elected in 1946, changes mirrored by the fiery women's caucus that insists Godzilla's radioactivity be revealed. Emiko's decisive role in the drama and her rejection of arranged marriage also point to the changing times. Emiko is openly dating Ogata, with no fear that her father will forbid their relationship. Issues of class status, and clashes between old and new values, create less conflict than in Honda's other works. Yamane is respected and well off, evidenced by his large home and television set (broadcasting began in 1953, and only the affluent could afford a TV as yet); but he allows his daughter to date a working-class sailor, and he adopts the poor island orphan Shinkichi (Toyoaki Suzuki) into his family. The Odo people are backwater folk - there is a funny moment when their mayor awkwardly tells the senate about cows and pigs eaten by Godzilla - yet the Tokyoites don't ridicule their superstitions, as Ryo Ikebe did in The Blue Pearl. Yamane names the monster after an Odo Island legend, simultaneously linking Godzilla to modern science and old mythology, and to America's atomic bomb and indigenous Japanese folklore and culture. In this way, Honda shrouds the monster's origin in mystery. It's not perfectly clear whether Yamane's theory is correct, or if the creature is a god, or both.

An early draft of Kayama's story began with the Lucky Dragon No. 5 returning to Japan, directly linking Godzilla's birth to America's hydrogen bomb. Honda saw his monster not as an indictment of America but of a symbol of a global threat, so he rewrote the scene. The vessel destroyed in the opening scene is a fictional one, though a lifebuoy on deck is labeled "No. 5."

"I did not want to [reference] the Lucky Dragon," Honda said. "If I did, I would have to [show how the] creature was born from that explosion. The screenplay is written with the 'speculation' that this creature was a result of a nuclear test, you see. I think that if I visually showed that [the bomb created the monster], that would have gone too far and I would not be surprised if people came out to protest such a film."

"Putting a real-life incident into a fictional story with a monster would not be appropriate. Instead, it became a matter of...the feeling that I was trying to create as a director. Namely, an invisible fear...the creation of the atomic bomb had become a universal problem. I felt this atomic fear would hang around our necks for eternity."

-"

- Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, From Godzilla to Kurosawa, by Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is Japanese cinema? : a history

What might Godzilla and Kurosawa have in common? What, if anything, links Ozu’s sparse portraits of domestic life and the colorful worlds of anime? In What Is Japanese Cinema? Yomota Inuhiko provides a concise and lively history of Japanese film that shows how cinema tells the story of Japan’s modern age.

Discussing popular works alongside auteurist masterpieces, Yomota considers films in light of both Japanese cultural particularities and cinema as a worldwide art form. He covers the history of Japanese film from the silent era to the rise of J-Horror in its historical, technological, and global contexts. Yomota shows how Japanese film has been shaped by traditonal art forms such as kabuki theater as well as foreign influences spanning Hollywood and Italian neorealism. Along the way, he considers the first golden age of Japanese film; colonial filmmaking in Korea, Manchuria, and Taiwan; the impact of World War II and the U.S. occupation; the Japanese film industry’s rise to international prominence during the 1950s and 1960s; and the challenges and technological shifts of recent decades. Alongside a larger thematic discussion of what defines and characterizes Japanese film, Yomota provides insightful readings of canonical directors including Kurosawa, Ozu, Suzuki, and Miyazaki as well as genre movies, documentaries, indie film, and pornography. An incisive and opinionated history, What Is Japanese Cinema? is essential reading for admirers and students of Japan’s contributions to the world of film.

1 note

·

View note

Text

2022/03/29 English

I saw a dream. I was making sashimi at a department store I worked as a part-timer. I had to make sashimi on every tray. I used blue trays which let us imagine a chilling atmosphere for summer. A general employee came here and said "Follow the manual and use the black trays". I said that "We have these blue trays as the most many stocks. How should we do if the stocks would end?". But the chief staff who came from the center of our company also came here and said "Don't be selfish!". I woke up there. A bad feeling remained. Yes, I had such an event.

During the afternoon break, I read Takashi Akutsu's "The journal of reading" at the office's cafeteria. Akutsu exactly reads various books. It says that he has his original way of reading. Of course, reading books means just watching and understanding the lines on every page. I also do that. But 'serious' readers read books and try to find something actual or useful in the books or for reading. They aren't 'satisfied with reading itself' as Kenichi Yoshida says. They can't do 'just reading'. Akutsu seems trying to let himself go deeper into the sea (or web) of text in every book I guess.

Inuhiko Yomota says the anima reading. He recommends not reading for creative purposes as they can be useful for studying or working but reading for only enjoying fun or pleasant. I want to be on his side. It's fun, and that's enough. Therefore I read books that never make money as Fernando Pessoa's "The book of disquiet". If I go back to Akutsu, he reads books that his antenna leads him to do so. Yes, it is a very loose activity. I thought that I also should do that 'loose' reading to be an expert.

At the night, I watched the hot movie, Ryusuke Hamaguchi's "Drive My Car". I don't think that it is a masterpiece. Yes, it was a well-made one but his past "Happy Hour" must be more vivid than it. But I admit that he didn't remake or copy "Happy Hour". He tried to open his new road and made "Drive My Car" so I have to praise his courage. Referring to Beckett and Chehov, he made this epic poem which tries to talk about "lost and found". So I have to say that I can't climb up the stage to praise this movie. I have to read Haruki Murakami's original novel "Men Without Women". Or I might have to read Haruki's career by starting "Hear The Wind Sings".

0 notes

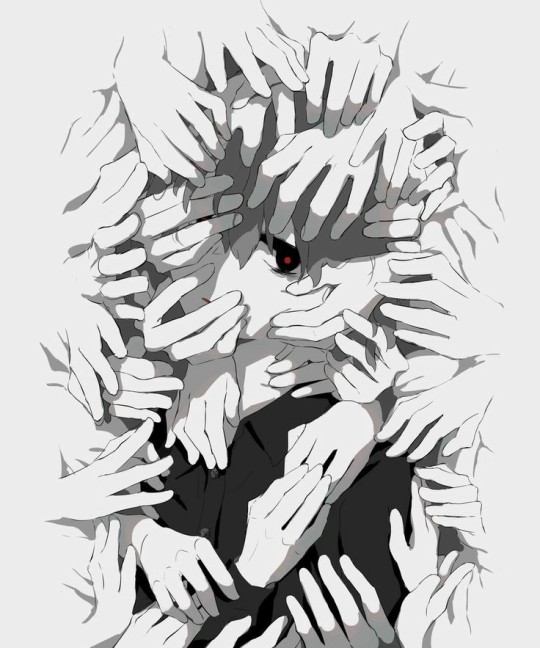

Photo

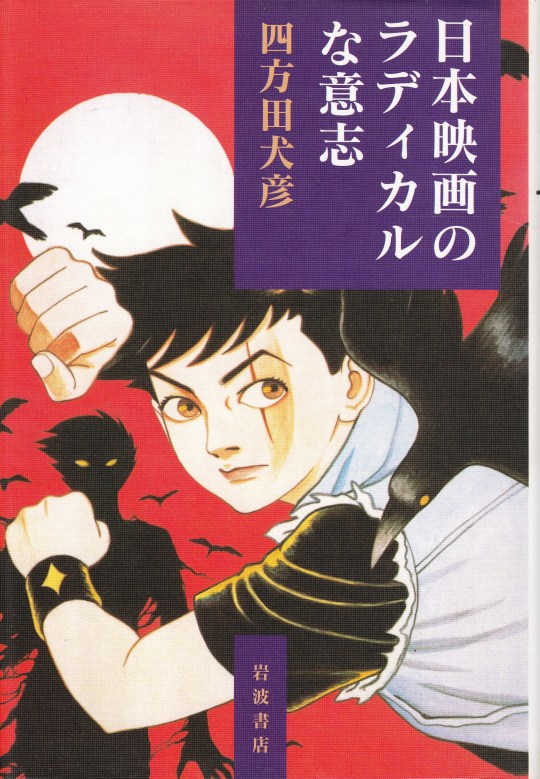

日本映画のラディカルな意志 四方田犬彦

岩波書店

装画:丸尾末広

16 notes

·

View notes