#labour history

Text

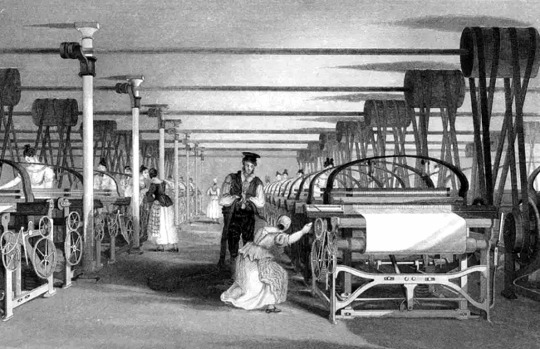

Almost 200 years since the first mill strike in the United States, which took place in my ancestral hometown of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, in 1824:

In late May 1824, a group of Pawtucket mill owners decided to make some drastic changes. Citing a “general depression,” they announced a plan to extend the workday by an hour, reduce the worker’s mealtime, and cut wages by 25%.

Workers in town did not accept these new conditions. About one hundred women walked out of the mills, causing them to shut down. From May 26th to June 3rd, 1824, a large number of additional textiles workers joined them in going on strike.

It was specifically women workers who were targeted by the mill owners, who claimed they made what was "'generally considered to be extravagant wages for young women.' The owners believed the young women would passively accept such wage decreases." The Pawtucket Mill Strike would inspire other working class uprisings such as Rhode Island's Dorr Rebellion.

Power looms in 1835: illustration from NPS article.

#may day#labor history#labour history#1820s#mill strike#pawtucket#rhode island#new england#mayday#working class#history#textiles#us history#classism#blackstone river valley#blackstone river

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

In light of the current WGA and SAG AFTRA Strikes still going strong at well over 100 days at this point, I thought that it would be interesting to cover another strike by creative folk in Hollywood: the 1941 Disney Animators Strike.

For context, by 1941 the other major animation studios in Hollywood by this point had unionised, following the first being the 1937 Fleischer Studios Strike which produced the first union contracts, while over at Disney the studio remained a firm holdout.

However, due to a series of incidents, including Disney not following through on the promise to share profits from the phenomenally successful Snow White (trade papers at the time reported that Disney’s studio was going to distribute an estimated 20% of Snow White’s earnings among the studio’s 800 employees, the actual bonuses those artists received were equal to or less than what they had previously received for the studio’s short films, with some Snow White animators, including Art Babbitt, did not receive any bonuses for their work), the alienating behaviour of Gunther Lessing (the lawyer responsible for Disney copyrighting Micky Mouse), and other factors (such as Disney's management style consisting of playing favourites, stealing credit and so on) understandably led to tensions rising within the company.

Things came to a head in 1941, when Art Babbitt, his highest-paid animator, resigned as president of the Disney company union to join the Animation Guild. After Disney fired Art in retaliation three days later, the strike was on.

The strike went on for five weeks, and destroyed the somewhat communal atmosphere some felt that the studio had amongst its staff at the time. Support came in the form of labour organiser Herbert Sorrell, a former boxer, who had successfully lead some other Hollywood strikes, including one with the Screen Actors Guild in the mid-1940s that brought him into conflict with their president, a man by the name of Ronald Reagan.

A notable incident involving Sorrell came when rumours of hired goons were coming to break the strike, leading to Sorrell send a gang of Lockheed aircraft mechanics with monkey wrenches to guard the tents of the striking animators which were pitched on the land across from the Disney Studio. It turned out to be merely a rumor and no damage was done, although Walt did reportedly almost get into a fight with Art

Eventually, FDR ended up having to send a federal negotiator to resolve the dispute, where they found in favour of the strikers in every issue. Disney, for his part, reportedly had been nearing a mental breakdown over the animators' "betrayal" left on a tour of Latin America to try and ease tensions.

Disney never forgave the strikers for the strike, and would maintain for years that rather than it being due to any mismanagement on his part, it was due to the animators being infiltrated by communists. Specifically, Herbert Sorrell, whom Disney would later report to the House of Un-American Activities Committee in 1947 as a communist infiltrator who was trying to turn his employees against him.

Y'know, so he learned nothing.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part one on my video essay series on the Fleischer Studios strike of 1937: the very first animation strike in history !

#max fleischer#Fleischer studios#popeye#Betty Boop#labor history#labor rights#labor movement#labour rights#labour history#animation industry#video essay#etc.#1940s#1930s#old Hollywood#wga#sagaftra#sag aftra#wga sag aftra strikes#Hollywood strikes#cel animation#cab Calloway

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

On a day like today (February 27th) of 1976, the Spanish police killed the worker Juan Pozierro Punyon during a construction workers’ strike in Barcelona, Catalonia.

When Europa Press published this event, the Government of Spain forced them to publish a “correction” saying that their previous news story had been a mistake and that he wasn’t killed by the police but had died as a result of an accident at his workplace.

He was one of the hundreds of people from national minorities (like Catalans, Basques, Galicians) and leftists who were victims of the Spanish State during the period known as “Transition to Democracy” (after the death of dictator Franco). This Transition is praised by the Spanish parties, including the ones who consider themselves “left” (PSOE, PCE -partially predecessor of Podemos-) as exemplary, peaceful and blood-less.

Why, if there was so much blood, death and torture? I can only guess that they don’t consider the blood of Basques, Catalans and anti-capitalists a blood not to be spilled.

#juan pozierro punyon#transició#transición#història#barcelona#catalunya#history#recent history#1970s#spain#democracy#national minorities#minority rights#minority languages#psoe#españa#catalonia#working class history#labor history#labour history

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

By the late 19th century, several states had passed laws limiting the age of child laborers and establishing maximum working hours. But at the turn of the century, the number of working kids soared. Between 1890 and 1910, 18 percent of children ages 10 to 15 were employed.

In his work for the National Child Labor Committee, Hine journeyed to farms and mills in the industrializing South and the streets and factories of the Northeast. He used a Graflex camera with 5-by-7-inch glass plate negatives and employed flash powder for nighttime and interior shots, hauling upwards of 50 pounds of equipment on his slight frame.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

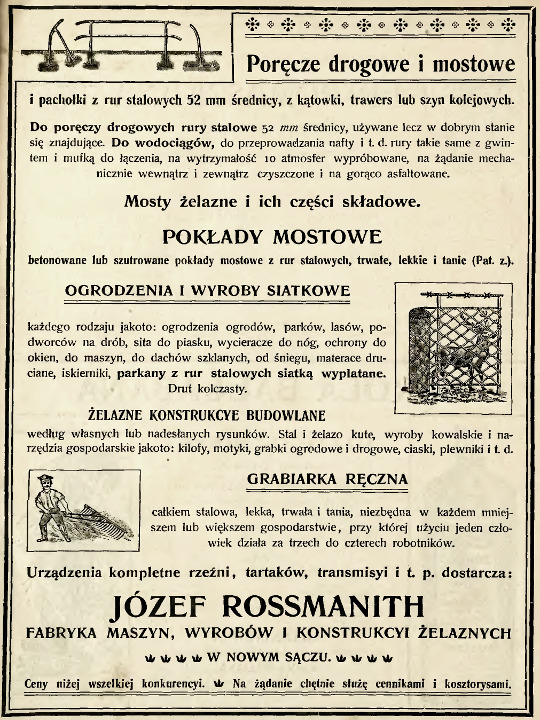

Nowy Sącz

ul. Fabryczna

foto z 16 lutego 2020

Na trzech pierwszych zdjęciach południowy szczyt, resztki dachu i ankier na ścianie hali fabrycznej z 1906 r. Należała do Józefa Rossmanitha, który otworzył tu swoje przedsiębiorstwo najpierw pod nazwą Odlewarni Żelaza, Stali i Metalów, a rozszerzywszy działalność, z czasem przemianował na Fabrykę Maszyn, Wyrobów i Konstrukcyi Żelaznych. Maszyny fabryczne napędzał nurt Młynówki, nieistniejącego dziś sztucznego strumienia zasilanego wodą pobliskiej rzeki Kamienicy. Koło wodne fabryki miało moc 42 koni mechanicznych.

Na dwóch ostatnich zdjęciach frontowa elewacja stojącego obok fabryki domu Rossmanithów z lat 1912-1914 r. projektu Zenona Adama Remiego, z kutą balustradą balkonową, prezentującą możliwości firmy.

Małżeństwo Rossmanithów. Urodzony w czeskiej Opawie, w spolonizowanej rodzinie niemieckiej, Józef poślubił Etelkę Adelajdę von Bartfai z węgierskiej rodziny Grünwaldów, z Bardejowa. Stąd w domu z kutym balkonem mówiono wtedy głównie po węgiersku.

Załoga fabryki w drugiej dekadzie XX w. Pośrodku widoczna prawdopodobnie Maria Maak, główna księgowa, a po śmierci Józefa Rossmanitha w 1914 r. kierowniczka firmy. W latach świetności, w fabryce pracowało 60 robotników. W 1920 r. zastrajkowali, czym wywalczyli sobie ośmiogodzinny dzień pracy.

Ogłoszenia reklamowe firmy z 1906…

…i 1912 r.

><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><

Nowy Sącz, Poland

Fabryczna Street

taken on 16 February 2020

First three photos show the southern facade, remains of the roof and an anchor plate on the wall of a factory hall built in 1906 r. It was a property of Józef Rossmanith who started his business here first as Iron, Steel and Metals Foundry and after diversifying the production renamed it Factory of Machines, Iron Products and Constructions. The factory equipment was powered by a waterwheel generating 42 hp thanks to nonexistent today Młynówka, an artificial stream supplied by the nearby Kamienica river.

Two latter photos show the front facade of the nearby Rossmaniths house from 1912-1914, designed by Zenon Adam Remi. The wrought iron balcony used to present the factory's abilities.

[the married Rossmanith couple]

Józef, born in Opava in a family of polonised Germans, married Etelka Adelajda von Bartfai née Grünwald, a Hungarian from Bardejov. Hence the default language of their household behind the iron balcony was Hungarian.

[the factory crew in 1910s]

In the center is most likely Maria Maak, the main accountant and after Józef Rossmanith's death in 1914 also the main manager. In the prime years up to 60 people used to work there. In 1920 they went on a strike that ended succesfully with an agreement for the 8h workday.

[the Rossmanith factory's ads from 1906]

[and 1912]

#historical facts#factories#industrial architecture#labour history#vintage ads#photographers on tumblr#original photography#Central Europe#Eastern Europe#Poland#Polska#Nowy Sącz#Nowy Sacz#balconies#wrought iron#eagles in art#retro#local history#family business#early capitalism

10 notes

·

View notes

Link

From mining to sex work and from the classroom to the docks, violence has always been a part of work. This collection of essays highlights the many different forms and expressions of violence that have arisen under capitalism in the last two hundred years, as well as how historians of working-class life and labour have understood violence. The editors draw together diverse case studies, integrating analysis of class, age, gender, sexuality, and race into the scholarship.

Essays span the United States and Canadian border, exploring gender violence, sexual harassment, the violent kidnapping of union organizers, the violence of inadequate health and safety protections, the culture of violence in state institutions, the mythology of working-class violence, and the changing nature of violence in extractive industries. The Violence of Work theorizes and historicizes violence as an integral part of working life, making it possible to understand the full scope and causes of workplace violence over time.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is often argued that the industrial revolution and the fossil fuel economy were driven by a need to increase productivity.

The reality is quite different: industrial machinery was first deployed by the capitalist class as a weapon against strikes.

#marxism#politics#communist#leftism#philosophy#socialism#communism#theory#ecology#machinery#machines#karl marx#history#labour history#working class#strikes#labor rights#worker solidarity#unions

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

@peat-moss-and-starlight

My replies are broken right now, sorry!! Bread and roses is a line from a speech given by women's vote and labour activist Helen Todd circa her work with textile unionizing.

It inspired a poem and was subsequently used as a slogan by various women's rights AND labour groups in the US, Canada and (lesser extent) UK. The poem is as follows:

Bread and Roses

As we come marching, marching, in the beauty of the day,

A million darkened kitchens, a thousand mill-lofts gray

Are touched with all the radiance that a sudden sun discloses,

For the people hear us singing, "Bread and Roses, Bread and Roses."

As we come marching, marching, we battle, too, for men—

For they are women's children and we mother them again.

Our days shall not be sweated from birth until life closes—

Hearts starve as well as bodies: Give us Bread, but give us Roses.

As we come marching, marching, unnumbered women dead

Go crying through our singing their ancient song of Bread;

Small art and love and beauty their trudging spirits knew—

Yes, it is Bread we fight for—but we fight for Roses, too.

As we come marching, marching, we bring the Greater Days—

The rising of the women means the rising of the race.

No more the drudge and idler—ten that toil where one reposes—

But a sharing of life's glories: Bread and Roses, Bread and Roses.

— James Oppenheim, 1911.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

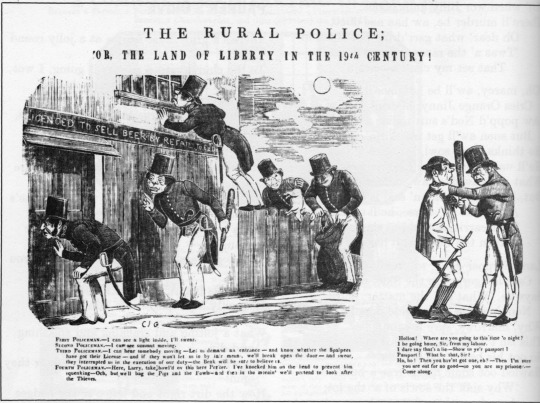

Illustration from 1839: the Chartist Insurrection by David Black and Chris Ford. A cartoon in the Penny Satirist 22 Aug 1840 on government plan to establish county police forces. Shows police raiding a pub, stealing chickens and pigs, and demanding to see a man’s passport.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

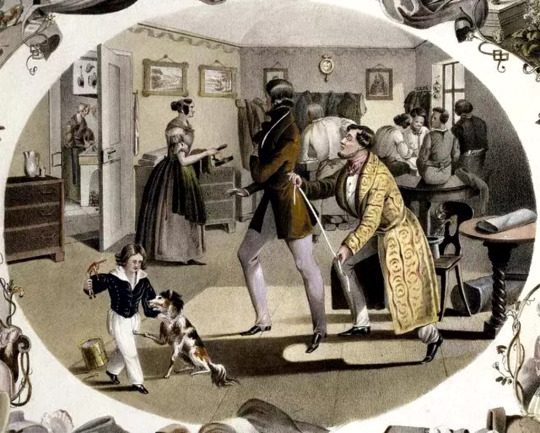

'La M. de la Corsets': c. 1832 lithograph showing a dressmaker or tailoress and client. The undergarments depicted include sleeve-plumpers.

1830s Thursday: Big sleeves, and even bigger dreams for women’s rights.

The growing vulnerability of working women in industrial society provoked a forceful response. In 1825 hundreds of them went out on strike against New York City clothing houses. In 1831 these same women organized themselves into a mass-membership United Tailoresses’ Society. At a time when journeymen were still devoting their political efforts to a defense of artisanal prerogatives in the master’s shop, these “tailoresses” (the appellation itself testified to an advanced degree of industrial consciousness, excluding as it did the more traditional dressmaking of the “sempstress”) already understood that in a capitalist economy no aspect of the work relationship remained non-negotiable. [...]

No one can help us but ourselves, Sarah Monroe, a leader of the United Tailoresses’ Society, declared. Tailoresses should consequently organize a trade union with a constitution, a plan of action, and a strike fund. Only then could we “come before the public in defense of our rights.” The Wollstonecraftian rhetoric was conscious. Lavinia Wright, the society’s secretary, argued that the tailoresses’ low wages and hard-pressed circumstances were a direct result of the way power was organized throughout society to ensure women’s subordination in all social relations.

— Michael Zakim, Ready-Made Democracy: A History of Men's Dress in the American Republic, 1760-1860

I was disappointed in my search for pictures of Sarah Munroe, Lavinia Wright, or really anything to do with the United Tailoresses’ Society. One online article outright stated, “We know very little about this speaker, Sarah Monroe, other than that she was a garment worker and president of the newly formed United Tailoress Society -- the first women-only union in the United States.”

I am in awe of this working-class woman, Sarah Monroe, who is quoted by Michael Zakim as saying in 1831:

It needs no small share of courage for us, who have been used to impositions and oppression from our youth up to the present day, to come before the public in defense of our rights; but, my friends, if it is unfashionable for the men to bear oppression in silence, why should it not also become unfashionable with the women?

'The Tailor's Shop': 1838 lithograph by Carl Kunz and Johann Geiger

#1830s#fashion history#labor history#labour history#us history#sarah monroe#Eighteen-Thirties Thursday#united tailoresses' society#michael zakim#women's history#also i have been sleeping on michael zakim's book it's really good#there were many strikes by female garment workers in the time period#amazingly forward-thinking they were trying to get sick pay and retirement benefits#they also campaigned against prison labour#tailors#dress history#inequality#industrial relations#19th century

380 notes

·

View notes

Link

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

*foaming at the mouth* hey do you know who Mary Anne Walkley was. Please let me tell you about Mary Anne Walkley.

#the ghost in the looking glass#the song of the shirt#Mary Anne Walkley#dress history#labor history#or rather#labour history#because she was British#textile history#Christina Walkley#who is the author of the book I’m currently reading about the exploitation of seamstrssses in 19th c England#but I have to imagine she’s related because British families are just like that#probably a distant relative considering the 130 year space in between them#but still

0 notes

Text

On this International Workers' Day we remember Isavel Vilà i Pujol, known as "Isabel Cinc Hores" ("Isabel Five Hours" in the Catalan language), fighter for children's rights.

Born in Calonge in 1843, she came from a working class family who worked in the cork stopper industry. In that time, the stopper industrial areas showed huge social inequalities. While the working class had a life expectancy of 48, the priests and other Church members lived on average to 64 years old. The workers' reduced life was a result of abusive work conditions and long hours (12 to 13 hours of work each day). They were not recognised a right to strike nor to unionize, and the owners fired anyone they wanted at any moment without giving explanations nor payments for it. Women were paid half as much as men for the same job, and children started working in the cork stopper factories at 6 years old for very little pay. The factories were humid and workers often dealt with toxic materials, which added to their insufficient diet, often caused illnesses and workplace accidents.

Isavel started working at a young age, and though she could barely read and write she was decided that she wanted to study and learn. In her free time, she studied and visited the ill. She took part in the republican uprisings against the Savoia Spanish monarchy and Spanish centralism, which were widespread protests in Catalonia, and joined the AIT (International Workers' Association) anarchist union. She decided to become a teacher, and while studying criticized the difficult spelling rules, which she considered too strict just like social rules in life (she simplified her name, from "Isabel Vila" to "Isavel Vila", since in her and most dialects of Catalan, b and v are pronounced the same).

She organized the workers of Llagostera (the town where she lived) and nearby Sant Feliu, and worked together with other women to protest for the abolition of the military draft, the separation of Church and state and freedom of religion.

She was most well-known for her fight for children's rights. The government passed a law limiting children's labour to 5 hours for boys under 13 and girls under 14 and to 8 hours for boys under 15 and girls under 17, but this law was not applied. She confronted local authorities demanding this law be respected, insisting that children need to grow healthy and that child labour perpetuates illiteracy. She was ridiculed for it both by the local bourgeoisie and by fellow trade unionists, who did not understand that children shouldn't be at work.

The coup in 1874 and the restoration of the Bourbonic monarchy illegalized the International and workers' associations. The government issued an arrest order for Isavel, who crossed the border with France and went on exile in Carcassona (Occitania). A rich Freemason family (the Muntada family) hosted her at their home, and during her exile Isavel could study to become a teacher.

She could come back to Catalonia 7 years later, when there was some political change. For the rest of her life, she worked as a teacher and created non-religious schools for working class children with new pedagogic methods. She quickly gained recognition as a great professional, but was excluded by other leftist school organizations. She spent her last years teaching in a free school for girls that she had founded in Sabadell, until she died in 1896.

#isabel cinc hores#isabel vilà i pujol#isavel vilà i pujol#història#history#international workers day#may 1st#labour history#children's rights#labor history#working class history#catalunya#catalonia#anarchism#anarchist#ait#child labor#llagostera#sabadell#calonge

48 notes

·

View notes

Link

The French lunch break wasn't always about bistros, leisurely meals and 90 minutes of amiable conversation. Many workers originally rejected the idea of leaving the workplace at all.

So what did it take for the French to finally take a break?

It turns out that the French lunch break was born during a public health crisis and was nearly killed in another.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Surrounded by deafening crashes of thunder, lightning of sizzling intensity, and violent, churning seas, the seaman often dangled at the edge of eternity, suspended between life and death. The sea's natural terror, its inescapable threat of apocalypse, imparted a special urgency to maritime social and cultural life."

-Marcus Rediker, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Seas

#take to the sea#quotes#age of sail#labour history#maritime history#this book was excellent both as an academic text and also in terms of readability#i zoomed through this

1 note

·

View note