#polykleitos

Text

Polykleitos (Greek, 480 BC-420 BC)

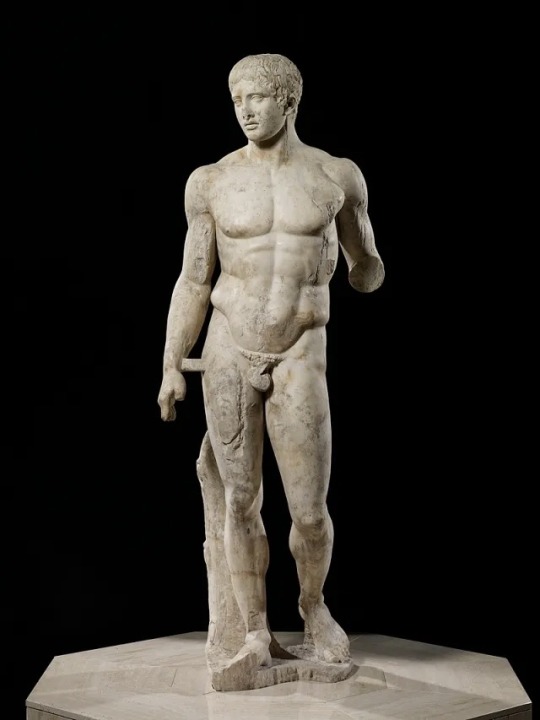

Doryphoros (Spearbearer) of Polykleitos, ca.440 BC

Contrapposto (Italian pronunciation: [kontrapˈposto]) is an Italian term that means "counterpoise". It is used in the visual arts to describe a human figure standing with most of its weight on one foot, so that its shoulders and arms twist off-axis from the hips and legs in the axial plane.

#Polykleitos#greek#grecian#art#southern europe#cradle of civilization#mediterranean#fine art#european art#classical art#europe#european#fine arts#europa#sculpture#sculptor#male figure#contrapposto#statue#western civilization

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

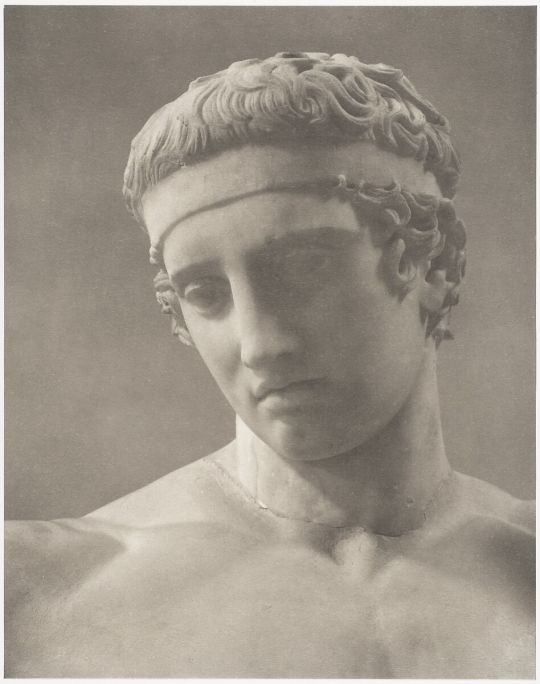

Statue of Diadoumenos. Roman Copy of a Greek Original by Polykleitos

Charles Sheeler

ca. 1943

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

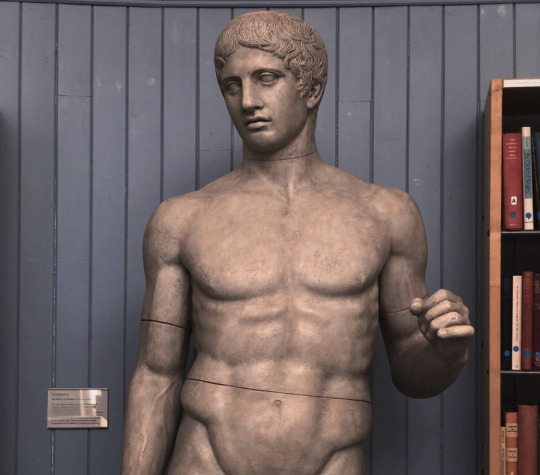

Doryphoros

Doryphoros was created by the Greek Sculpter Polykleitos c.450-440 BCE. This - of course - is not the original statue, rather a cast of the Roman copy of the original, which has been lost :) This particular lad is at home in the HCA Library of the University of Edinburgh! x

#Doryphoros#Polykleitos#ancient greek sculpture#greek sculpture#greek art#University of Edinburgh#University of Edinburgh HCA#History classics and archaeology#Edinburgh university#Roman sculpture#Art of Antiquity#greek art and archaeology#greek archaeology#roman archaeology#roman art#archaeology#ancient history#scottish youtuber#archaeolorhi

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Neuroaesthetic studies have revealed that strong aesthetic preference induces enhanced neural activity in the sensory region corresponding to the modality of a presented stimulus... implicated in aesthetic emotional and reward processing...

From antiquity to the present day, it’s a common view that the contrapposto posture elevates the aesthetic appeal of the artwork. Humans have evolved aesthetics preferences as a result of preferences for sexual and social partners, as well as food and habitat, etc., and these evolved preferences that are rooted in our evolutionary past appear to have engaged and influenced the artists of the Renaissance era as much as today's artists and art appreciators (Di Dio et al., 2007;Swami et al., 2007;Wassiliwizky & Menninghaus, 2021).

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back in Naples - weeks before Covid -soon we were all told to stay home.

On the 6th January 2020 I returned to Naples not realising it was going to be my last foreign journey anywhere for two years. On 31st January two Chinese tourists in Rome were tested positive for the Covid virus and the Italian government declared a state of emergency. The first case of Covid was documented in the UK that day too, followed by a series of lockdowns beginning in March.

Soon we…

View On WordPress

#Cappella Sansvero Naples#Caravaggio#Church of Pio monte della Misericordia Naples#covid#Cristo Velato#Doryphorus#Farnese Atlas#Farnese Bull#Farnese Hercules#Farnese marbles#Farnese Runners#Giuseppe Sanmartino#Italian holidays#Italy#Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli#naples#National Archaeological Museum Naples#Polykleitos#Raphael#sculpture#statues#The Veiled Christ#Titian

0 notes

Text

had to do a portrait of that one polykleitos statue in art class today. i did my best 😭

1 note

·

View note

Text

Polykleitos Rengos (Greek, 1903-1984), Paraportiani à Mykonos [Church of Panagia Paraportiani, Mykonos], 1925. Oil on cardboard, 50 x 38.5 cm.

602 notes

·

View notes

Text

Polykleitos Rengos - Sunset over Aghia Sophia viewed from Yildiz Palace, Istanbul (1950)

151 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Spitallamm dam, Grimselsee, Switzerland, 1932

VS

Ancient Theatre, Epidaurus, Greece, 4th century BC

#Spitallamm#Grimselsee#dam#Arch dams#Hydropower#barrage#architecture#engineering#Epidaurus#greece#ancient greece#theatre#ancient theatre#Polykleitos the Younger#Pausanias#argolis#archaeology#greek archaeology#landscape architecture#Asclepius#World Heritage Site#UNESCO

940 notes

·

View notes

Photo

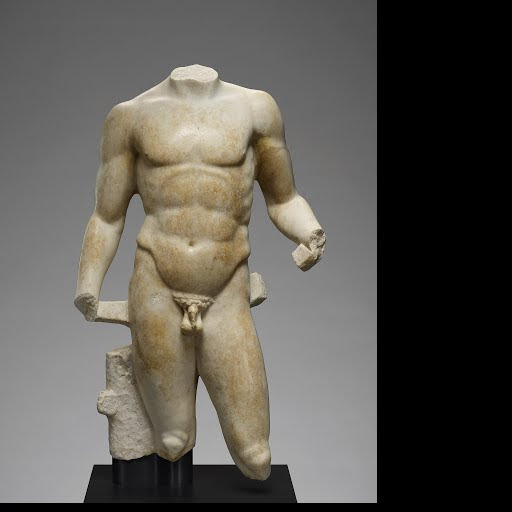

A ROMAN MARBLE TORSO OF THE DIADUMENOS OF POLYKLEITOS

CIRCA 1ST CENTURY B.C.-1ST CENTURY A.D.

30 in. (76.2 cm.) high.

This superb muscular torso can be recognized as a Roman copy of Polykleitos’ Diadumenos, or fillet-binder, one of the most celebrated sculptures from antiquity. The pelvic thrust to the left and the accompanying curvatures of the lower abdomen, plus the articulation of the shoulders resulting from the arms once being raised, are all exactly matched on several more complete versions of the now-lost original (for the best preserved example see the figure from Delos, now in Athens, pl. 176 in H. Beck, P.C. Bol, and M. Bückling, Polyklet, Der Bildhauer der griechischen Klassik).

The Diadumenos is referred to by the Roman writers Lucian, Pliny, and Seneca, who praised it for its beauty and value. The original does not survive, but based on these literary descriptions, it is securely recognized in Roman copies. Where the original once stood and what precisely was depicted is not known, and the ancients are quiet on these points. Undoubtedly, Polykleitos' creation was in bronze, and would have been commissioned to celebrate an athletic victory and set up in one of the Panhellenic sanctuaries.

Polykleitos was one of the most famous and influential sculptors of the High Classical period. A native of Argos in the Peloponnesus, his artistic career flourished from circa 450-420 B.C. In addition to the Diadumenos, several other of his works are described in ancient literature and are recognized in surviving Roman copies, including the Doryphoros or Spear-Bearer, as well as his Kyniskos, identified as the Westmacott Athlete since the 19th Century. His Amazon of Ephesus was famed for having been chosen in a competition over works by the sculptors Pheidias and Kresilas, while his most magnificent creation was the colossal gold and ivory cult statue of Hera from the Heraeum of his native Argos. Pliny tells us that Polykleitos wrote about his theories of rhythm and proportion. This sculptural Canon emphasized the juxtaposition of antithetical pairs, such as right and left, straight and curved, relaxed and tensed, rest and movement. The Doryphoros is considered the embodiment of Polykleitos's canon, while the Diadumenos beautifully demonstrates the canon's "inexhaustible possibilities".

#A ROMAN MARBLE TORSO OF THE DIADUMENOS OF POLYKLEITOS#CIRCA 1ST CENTURY B.C.-1ST CENTURY A.D.#marble#marble sculpture#roman sculpture#ancient sculpture#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#anicent rome#roman history#roman empire#roman art

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marble statue of a wounded Amazon. Roman 1st–2nd century CE. x

In Greek art, the Amazons, a mythical race of warrior women from Asia Minor, were often depicted battling such heroes as Herakles, Achilles, and Theseus. This statue represents a refugee from battle who has lost her weapons and bleeds from a wound under her right breast. Her chiton is unfastened at one shoulder and belted at the waist with a makeshift bit of bridle from her horse. Despite her plight, her face shows no sign of pain or fatigue. She leans lightly on a pillar at her left and rests her right arm gracefully on her head in a gesture often used to denote sleep or death. Such emotional restraint was characteristic of classical art of the second half of the fifth century B.C.

The original statue probably stood in the precinct of the great temple of Artemis at Ephesos, on the coast of Asia Minor, where the Amazons had legendary and cultic connections with the goddess. The Roman writer Pliny the Elder described a competition held in the mid-fifth century B.C. between five famous sculptors, including Phidias, Polykleitos, and Kresilas, who were to make a statue of an Amazon for the temple. This type of statue is generally associated with that contest.

430 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue of a youthful, beardless Greek hero, Herakles (Roman - Hercules) 2nd CE , a Roman copy of a Greek original attributed to famous sculptor Polykleitos. Herakles holds the Nemean lion skin (his first labor) as he leans on his club, National Museum of Rome

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Body Fat in Greco-Roman Antiquity (transcribed article)

A long time ago I made a post about the depictions of Dionysos/Dionysus/Bacchus as fat. You can read it here if you want - but that was just me going on about stuff taken left and right, nothing too serious, just thoughts.

I want to bring you today a serious article about the perception of the fat body in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. This article is actually a page hosted on "Google Arts and Culture", titled "In the Flesh: Body Fat in Ancient Art". It was created by the J. Paul Getty Museum, and you can read it all here. But the website has a really specific design that makes it hard for some people to read the page, so I thought why not help share it around by copying it below. Of course, nothing belongs to me, I am just transcribing it all (plus copying the images). All credits go to the J. Paul Getty Museum.

In the Flesh: Body Fat in Ancient Art

Ancient Greek and Roman writers criticized bodies of different sizes for a variety of reasons. But in works of art, body fat was often depicted in ways that defy our expectations.

A Different Ideal

Terms like "overweight" and "underweight" originate in modern medicine's concept of an ideal body weight. Calculated to minimize mortality risk, this medically desirable weight varies based on such factors as height, age, and fitness.

Ancient Greeks and Romans compared the appearance of their bodies with respect to a more abstract ideal.

For the ancient physician Galen, measurements for the ideal body were expressed centuries earlier in the Canon, a treatise on statue proportions by the 5th-century BC sculptor Polykleitos:

(Male torso, about A.D. 100, Unknown)

"[Neither the overweight nor the underweight body] is in due proportion. But the body which equals the Canon of Polykleitos reaches the summit of complete symmetry."

— Galen, Ars Medica K 343

For the ancient Greeks, precisely measured weight was less important than the perception of symmetry and balance.

They had a term for this desirable state of wellness: εὔσαρκος (eusarkos), meaning "well-fleshed" or "fleshy."

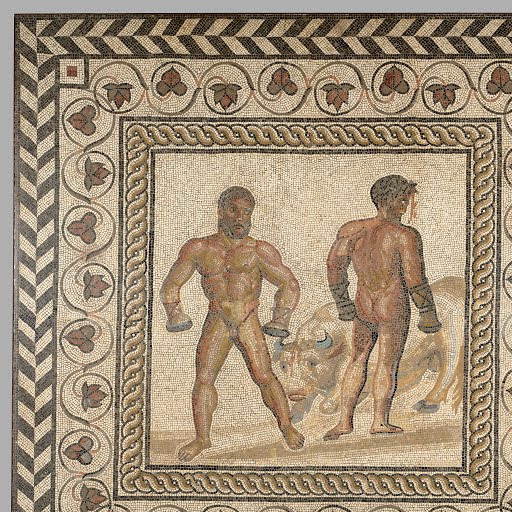

(Mosaic floor with combat between Dares and Entellus, A.D. 175-200, Unknown)

Because the Greeks prized moderation in all things, bodies or behaviors that stood out from this ideal were targets of criticism. Perhaps surprisingly, this criticism also applied to muscular athletes, such as wrestlers and boxers, who required constant high-calorie diets.

(Statuette of a boxer, unknown)

Big Bodies in Comedy

Mockery of those who ate more or less than necessary was one way to impose social compliance and maintain political order.

(Apulian red-figure bell krater, 370-360 BCE, Cotugno painter)

Many Greek and South Italian vases often depict comic actors wearing "fat suits" (as well as a mask and a phallus) to embody popular character types.

Actors used such props as comic gags, and vase painters often represented them with great care.

On this Apulian mixing bowl, lines extending across the actor's chest make clear that his large, sagging breasts are artificial. His belly is unnaturally circular and hangs too low — further evidence that he is wearing a costume.

It seems that the painter wanted to pointedly emphasize the exaggerated nature of such costumes.

Ample Satyrs

Not all depictions of larger bodies were mocking. Animal ears and the double flute identify this figure as a satyr, or a woodland deity. He reclines in a pose that would remind viewers of the satyrs' master, the wine god Dionsyos, who is often depicted reclining at a banquet.

Instead of on a fancy couch, the chubby old satyr rests on a full wineskin!

(Fragment of an Apulian squat Lekythos, 350-325 BC, Darius painter)

Under tufts of gray hair, lines accentuate the curving folds of the old satyr's body. Unlike the ridiculously artificial bodies of the padded actors, the satyr's big, hairy body is gentle and soft.

Like the plump pillow on which he rests, the satyr appears comfortable and at ease. This scene is meant to be lighthearted, and does not appear cruel or mocking.

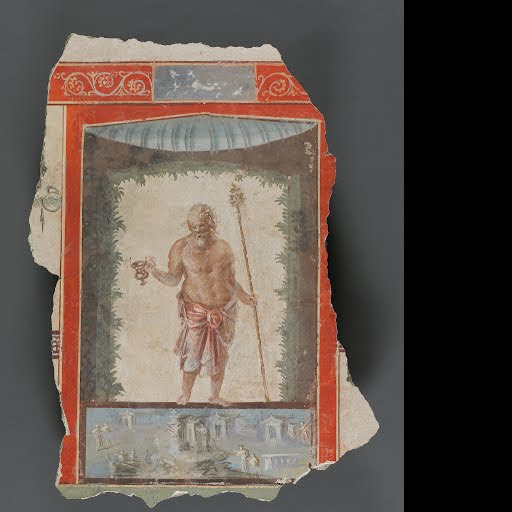

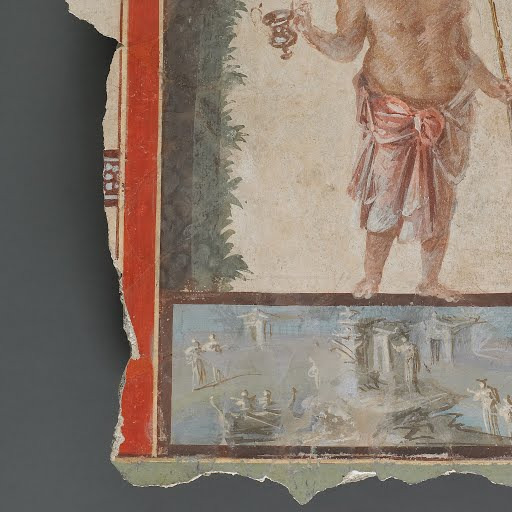

(Fresco fragment depicting an old Silenos with kantharos and thyrsos, AD 1-79, Unknown)

Similar attention to detail can be seen in this Roman wall painting of the old satyr Silenus. The painter’s skillful use of red shadows and pink highlights builds up the volume of his chest and stomach, which appear both soft and sturdy at the same time.

These fleshly older satyrs were symbols of pleasure-seeking and leisure.

Fragile Bodies on the Margins

Skinny or underweight bodies were also criticized, in part because of the association between emaciation and illness. Thinness could also negatively reflect on one's character.

(Miniature skeleton, unknown)

Ancient authors often noted a person's skinny frame as a way of pointing out their intellectual or social irrelevance.

The association of thinness and powerlessness is sometimes exploited in representations of enslaved individuals, domestic servants, and those otherwise marginalized in society.

(Finial with a resting youth, unknown)

On this figurine of a resting youth, the individually shaped ribs might suggest that the figure is undernourished.

In depictions of older individuals, such as this statuette of an old woman, underweight features are often used to indicate frailty.

(Statuette of an old woman, 100-001 BCE)

Such subjects were popular in the Hellenistic period (c. 330-31 BC) —a time of unprecedented social inequality — and consciously aestheticized:

"When we see emaciated people we are distressed, but we look upon statues and paintings of them with pleasure, because imitation, as such, is attractive to the mind's nature."

- Plutarch, Quaestiones convivales 5.1.

Size and Gender

Body fat was also linked to gender, especially in the Roman Empire. While bodies of women were routinely criticized by Roman authors, fluctuation in weight did not render them less feminine. By contrast, both fat and skinny men were explicitly mocked as effeminate, lacking either physical strength or stamina.

Biographies of unpopular Roman emperors often weaponize their body size in this way. Of the emperor Galba, the biographer Suetonius writes, "it is said that he was a heavy eater," immediately before turning to rumors about his inclinations towards "unnatural desires."

Such fat-shaming seems not to have mattered to the emperors themselves. Their official portraits show little concern for concealing the fullness of their faces.

(Torso of a cuirassed statue, unknown)

The situation may have been different in military affairs. The anxieties Roman men felt about their bodies can be seen in their choice of armor. Their bronze breastplates were decorated with chiseled pectorals and washboard abs, creating the illusion of a skin-tight fit.

It is unlikely that such breastplates were meant to deceive, any more than the fat suits of comic actors. What they offered to their wearers was the illusion of inhabiting — for a moment — the ideal body of a Polykleitan statue.

Divine Softness

A closer look at ancient art reveals that the bodies of gods were sometimes less harshly judged than those of mortals.

Depictions of certain gods regularly focus on the softer parts of their bodies.

(Bowl with a medallion depicting Dionysos and Ariadne, unknown artist, -100)

The maker of this Hellenistic silver medallion went out of their way to show the curvy bodies of the wine god Dionysus and his wife Ariadne, engraving lines under their bellies to highlight the sensuality of their encounter.

Some popular representations of the love goddess Venus, such as the so-called "Crouching Venus" type, unquestionably emphasize the fleshiness of her body.

Statue of a Crouching Venus Statue of a Crouching Venus, Unknown, A.D. 100–150, Provenant de la collection : The J. Paul Getty Museum

Modern observers have highlighted the positive associations between fleshiness and fertility expressed by a variety of Greek and Roman authors, but there is more to the story.

The rolls of flesh on the goddess's belly also gave the ancient sculptor a means of creating a very intimate encounter between viewer and goddess.

To ancient viewers of all ages and genders, accustomed to seeing gods represented solemn and upright, the crouching pose allowed a glimpse into the goddess's private world.

The crouching goddess seemed more approachable to worshippers, in part because her body moved in ways they could recognize from their own lived experience. The softness of Venus’s body made the cold, hard marble come to life.

#ancient greece#ancient rome#body positivity#fatphobia#greek gods#body fat#venus#dionysus#dionysos#ariadne#roman emperors#satyrs#underweight#satyr#silenus#ancient art#ancient greek art#body types#art#weight#ancient greek society#roman empire

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Doryphoros (Roman copy after Polykleitos), 27 BCE - AD 68, Minneapolis Institute of Art x Shawn Mended out in Los Angeles, September 2022.

#shawn mendes#art#ancient greece#ancient rome#marble statue#he's just the human form of those silly little gay marble statues the greek and romans did thousands of years ago

268 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Polycleitos (Argos, 5th c BC)

_

Diadumenos (diadem-bearer) / Youth Tying a Headband. The Athens example, copy of bronze original ca. 420 BC. Marble: 1.95 m H. National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

Winner of an athletic contest, lifting his arms to knot the diadem. The figure stands in contrapposto. “The thorax and pelvis of the Diadumenos tilt in opposite directions, setting up rhythmic contrasts in the torso that create an impression of organic vitality. The position of the feet poised between standing and walking give a sense of potential movement. This rigorously calculated pose, found in almost all works attributed to Polykleitos, became a standard formula used in Greco-Roman and, later, western European art."

Doryphoros (spear-bearer). Rendered somewhat above life-size: 2.12 m (6 feet 11 inches), the lost bronze original of the work would have been cast circa 440 BC, but it is today known only from later (mainly Roman period) marble copies.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Doryphoros.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doryphoros

Polykleitos - Alchetron, The Free Social Encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diadumenos

Photographs of the first excavations at Delos island, where both sculptures were unearthed. From the 19th c. French archaeologists book “Delos 1873-1913″.https://greekreporter.com/2022/05/13/excavations-greek-island-delos/

Kararadaygum Photography: Diadumenos portrait (top)

https://kararadaygum.tumblr.com/post/672887937879408640

https://kararadaygum.tumblr.com/

thnx didoofcarthage & ancientprettythings

#Polycleitos#sculpture#Diadumenos#Doryphoros#archaeology#Delos#gr#copy#marble#beauty#male#classic#contrapposto

509 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a bronze statue of an athlete demonstrating "Apoxyomenos" where an athlete scrapes sweat and sand and oil from his body with a strigil. The strigil was in the right hand but has been lost over time. This process was usually accompanied by strong deep tissue massage depending on the wealth and success level of the individual. A Roman copy of the bronze original by the Greek Polykleitos ca. 320 B.C. It is on display in the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna.

15 notes

·

View notes