#royal scots greys

Text

Gordons and Greys to the Front at Waterloo by Stanley Berkeley

#battle of waterloo#waterloo#napoleonic wars#art#stanley berkeley#royal scots greys#scots greys#cavalry charge#cavalry#history#highlanders#stirrups#highlander#great britain#scottish#britain#british#europe#european#napoleonic#eagle#french#battlefield#belgium#france#netherlands#england#english#gordon highlanders#scotland

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Royal Scots Greys was a cavalry regiment in the British army known for their grey horses. In WW1 they were ordered to dye their mounts dark chestnut so they would be less conspicuous and make the regiment harder to identify. While they were in reserve the horses were allowed to have their natural colour.

Scots Greys (1918) by John Singer Sargent (1856–1925). Watercolour paint on paper. (picture source)

Studies for "Scots Greys" (1918) by John Singer Sargent (1856–1925). Graphite on wove paper. (picture source)

Royal Scots Greys on a road in France (1914-1918) a photo from The Dutch National Archives. (picture source)

#john singer sargent#old photography#royal scots greys#scots greys#art#horses#art history#horse#horse art#military#cavalry#1800's art#19th century art#world war 1#ww1#war#drawings#horses in art history

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just watched Waterloo, and given the critique that Ridley Scott gives Napoleon RTS powers, its interesting how Waterloo uses the realities of command and communication for dramatic effect.

The charge of the Union Brigade is a great example.

youtube

At 2:50 in the video, the French lancers are charging out to attack the Scots Greys. Wellington and Uxbridge see them, and realising the Scots Greys are in danger Uxbridge orders their retreat. The trumpeter sounds the order but they can't hear him. He keeps playing over and over as Wellington gets more anxious until he finally shouts for him to stop, knowing there's no way to save Ponsonby and his men now.

Napoleon and Wellington can't just magically make people do what they want, they have to actually tell them. Their officers have their own opinions and talk back, or are already too far to be reached, or like Grouchy were given very clear orders by you and have no way of knowing you changed your mind until they get a letter too late to make any difference. There's tension and drama in that, and if Ridley Scott ignored it it's a real missed opportunity.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

O wae is me my hert is sair, tho but a horse am I.

My Scottish pride is wounded and among the dust maun lie.

I used to be a braw Scots grey but now I'm khaki clad.

My auld grey coat has disappeared, the thocht o't makes me sad.

- Royal Scots Greys, poem recited in reaction to the change their scarlet uniforms and grey horses to khaki.

Formed in 1681, the Royal Scots Greys cavalry unit was Scotland's senior regiment. Its long and distinguished service continued until 1971, when it was merged into The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

The regiment was formed as The Royal Regiment of Scots Dragoons in 1681 from a number of existing troops of cavalry. Its first action was the suppression of the Earl of Argyll’s rising, launched in 1685 in support of the Duke of Monmouth’s revolt.

Following the Glorious Revolution (1688), the regiment went over to King William III, fighting for him against the Jacobites in Scotland. It was ranked as the 4th Dragoons in 1692.

The following year, the entire regiment attended a royal inspection in London mounted on ‘greys’ (horses with white or dappled-white hair). This gained it the nickname ‘Scots Grey Dragoons’. However, this only became part of its official title in 1877, when it was renamed the 2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys).

After a period of home service, it joined the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-14). The regiment fought at Schellenberg (1704), Blenheim (1704), the Passage of the Lines of Brabant (1705), Ramillies (1706), Oudenarde (1708), Tournai (1709), Malplaquet (1709) and Bouchain (1711).

It spent a further period on home service until 1742, when it joined the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48). The regiment deployed to Germany first, fighting at Dettingen (1743). It then moved to Flanders, where it served at Fontenoy (1745), Rocoux (1746) and Lauffeld (1747).

It’s next major battle honour was at the Battle of Waterloo (1815). This was its only Napoleonic battle honour, at which 201 of its men and 228 of its horses were killed attacking a French infantry brigade. In this attack, Sergeant Charles Ewart captured the French 45th Line Infantry Regiment’s eagle. This later became part of the unit’s cap badge.

A long period of home service followed until the Crimean War (1854-56). There, the regiment won two Victoria Crosses charging uphill against 3,000 Russian cavalry at Balaklava (1854).

On returning home, it saw no further active service until the Boer War (1899-1902) in 1899. During this campaign, it camouflaged its white horses with khaki dye. In the years since Balaclava, much had changed about warfare. Gone were the red coats and bearskin shakos. The Scots Greys would now fight wearing khaki. In fact, with the popularity of wearing khaki that accompanied the start of the Boer War, the Scots Greys went so far as to dye their grey mounts khaki to help them blend in with the veldt. It took part in the Relief of Kimberley, fighting at Paardeberg (1900), before joining the advance to Bloemfontein and later Pretoria, service that included the Battle of Diamond Hill (1900). It also fought in the anti-guerrilla campaign in 1901-02.

After returning home in 1905, the Scots Greys stayed in Britain until August 1914, when it moved to France.

It fought on the Western Front as both cavalry and infantry, winning several battle honours including the Retreat from Mons (1914), Marne (1914), Ypres (1914), Neuve Chappelle (1915), Arras (1917) and Amiens (1918).

According to a report in Scottish newspapers of the time it was decided to paint the horses khaki as their grey coats were too visible to German gunners. This gave rise to a comic poem posted above, of which this is the first verse.

**Royal Scots Dragoon Guards set off from Edinburgh Castle

#royal scots greys#royal scots dragoon guards#regiment#british army#scotland#soldier#horses#horse riding#edinburgh castle#military#traditions#military traditions

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edinburgh, 2023

#edinburgh#edinburgh castle#princes street#royal scots greys#scotland#street photography#photography#2023

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A British soldier and dog at the officers' mess kitchen of the Royal Scots Greys at their camp, October 1916.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tudor Bedroom 👑🌹

#tudor#tudors#henry viii#princess margaret#princess mary#catherine of aragon#anne boleyn#jane seymour#anne of cleves#katherine howard#katherine parr#edward VI#lady jane grey#mary I#elizabeth I#mary queen of scots#royal doulton#wedgwood#coalport#HRP dolls#brenda price dolls

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review - 'The Pocket Guide to Royal Scandals' by Andy K. Hughes

Book Review – ‘The Pocket Guide to Royal Scandals’ by Andy K. Hughes

A fun romp through royal history, looking at some of the most scandalous royals and what they did. There is very much a focus on English history, with just some of the more famous foreign rulers thrown in like Catherine the Great and Vlad the Impaler. The focus is also largely on the modern period, with nearly half of the book covering just the 20th century. There is only one Roman Emperor…

View On WordPress

#andy hughes#andy k hughes#Anne Boleyn#Book#Book Review#catherine the great#Elizabeth I#Henry VIII#Jane Grey#Katherine Howard#Lady Jane Grey#Mary Queen of Scots#monarchs#Monarchy#Pen and Sword#pocket guide#Review#royal#royal scandals#Scandal#scandals#vlad the impaler

0 notes

Text

"Ferguson" Breech-Loading Rifle from Aberdeen, Scotland dated to 1776 on display at the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards Museum in Edinburgh Castle, Scotland

These rifles were invented by Lieut-Colonel Patrick Ferguson of Pitfour, Aberdeenshire. Ferguson's improved quick thread breech-loading rifle was an improvement on an earlier invention. He served as a subaltern in the Royal North British Dargoons (Scots Greys) from 1759 to 1762. Ferguson was killed in South Carolina at the Battle of King's Mountain in 1780 during the American Revolutionary War.

Photographs taken by myself 2023

#military history#18th century#hanover#gerogian#british empire#scotland#scottish#royal scots dragoon guards museum#edinburgh#barbucomedie

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Am Fear Liath Mòr

Am Fear Liath Mòr is the name for a presence or creature which is said to haunt the summit and passes of Ben Macdui, the highest peak of the Cairngorms and the second highest peak in British Isles after Ben Nevis.

Pic by mlappas on deviantart

Although there have been many purported encounters with the Big Grey Man, few eyewitnesses have actually seen the creature. It is reported to be very thin and over ten feet tall, with dark skin and hair, long arms, and broad shoulders. Most often, the creature remains unseen in the fog of the mountain, with encounters limited to the sound of crunching gravel as it walks behind climbers and a general feeling of unease around the mountain. Tangible evidence of its existence is limited to a few photographs of unusual footprints, so the majority relies on the credibility of eyewitness encounters.

The figure has many similarities with the Brenin Llwyd (English: Grey King) of Welsh mythology, this figure is also semi-corporeal, silent and uses the mists as a cloak to prey on unwary travellers. Unlike the Am Fear Liath, Brenin Llwyd is found in mountainous locations across Wales, and is particularly noted to prey on children.

In 1925, J. Norman Collie gave the first recorded account of a Grey Man encounter. A noted hiker, professor, and member of the Royal Geographical Society, Collie recounted a terrifying experience he had as he hiked alone near the summit of Ben Macdui years earlier in 1891.

"I was returning from the cairn on the summit in a mist when I began to think I heard something else than merely the noise of my own footsteps. Every few steps I took I heard a crunch, and then another crunch, as if someone was walking after me but taking steps three or four times the length of my own. I said to myself, this is all nonsense. I listened and heard it again but could see nothing in the mist. As I walked on and the eerie crunch, crunch sounded behind me, I was seized with terror and took to my heels, staggering blindly among the boulders for four or five miles nearly down to Rothiemurchus Forest. Whatever you make of it, I do not know, but there is something very queer about the top of Ben Macdui and I will not go back there again."

Collie's account was reported in the local press, which started a debate between sceptics and believers within the community. Other climbers came forward with their own encounters, which they had previously been afraid to share. One climber, Hugh D. Welsh, said that he hiked the summit with his brother in 1904, where throughout the day and night they heard "slurring footsteps, as if someone was walking through water-saturated gravel." Both felt "frequently conscious of something near us, an eerie sense of apprehension."

In 1945, Pete Densham was participating in rescue work in the Cairngorm mountains during World War II. One day, he reported hearing strange noises, mist closing in on his location, and increasing pressure around his neck. He fled before seeing anything concrete. A friend of his, climber Richard Frere, wrote about his sense of "a Presence, utterly abstract but intensely real" on the mountain and heard "an intensely high singing note" a few years later in 1948. Frere also presented the encounter of another mutual friend, who wished to remain anonymous, while he camped on Ben Macdui. He reported waking up feeling an inescapable feeling of dread, and looked out of his tent to see a large figure with dark hair standing in front of the moon in silhouette.

In 1958, naturalist and mountaineer Alexander Tewnion published an article in The Scots magazine about an encounter with the Grey Man in 1943.

"I spent a 10-day leave climbing alone in the Cairngorms. One afternoon, just as I reached the summit cairn of Ben MacDhui, mist swirled across the Lairig Ghru and enveloped the mountain. The atmosphere became dark and oppressive, a fierce, bitter wind whisked among the boulders, and... an odd sound echoed through the mist – a loud footstep, it seemed. Then another, and another... A strange shape loomed up, receded, came charging at me! Without hesitation I whipped out the revolver and fired three times at the figure. When it still came on I turned and hared down the path, reaching Glen Derry in a time that I have never bettered. You may ask was it really the Fear Laith Mhor? Frankly, I think it was.

No photographs of the Big Grey Man have ever been taken. Photographer John A. Rennie supposedly found a series of footprints in Spey Valley, measuring 19 inches (48 centimetres) long and 14 inches (36 centimetres) wide. These were published in a book, but he later discovered that they were a natural phenomenon caused by rainfall eroding the snow.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The maverick heroics of MI6 agent James Bond may actually be based on the true story of one brave soldier, who took on the Germans and won again and again. In this archive piece, we look back on Patrick Dalzel-Job's stranger-than-fiction life

If the dashing hero of Ian Fleming's best-selling spy thrillers were among us, is it likely he could be found living alone on a far-away hill by the sea in Scotland?

A mildly spoken gentleman who lived to his eighties, then grey and a little stooped—could he have been secret agent 007? Come on.

Ah, but life is stranger than fiction.

Some of those who know best have always believed that Fleming based his superspy on a wartime comrade named Patrick Dalzel-Job—yes, our elderly gentleman who lived his final days in the Highlands.

There were other influences, of course. Bond's love of vodka martinis and handmade cigarettes came, in fact, from Ian Fleming himself; and whereas 007 tumbled into bed with a different beauty every few pages, Patrick Dalzel-Job (pronounced Deal-Jobe), loved only one woman all his life.

But there is something here. Consider:

Job, like Bond, was half Scots, a one-time naval officer, a master of languages who in real life performed precisely the kinds of derring-do Fleming later attributed to his flamboyant make-believe hero.

By the time Dalzel-Job walked into Commander Ian Fleming's Admiralty office one day in 1944 looking for a new assignment, he had already seen service as a seaman, commando, submariner and spy, and had just become probably the first naval officer to qualify for army parachute wings.

Fleming, an ex-journalist who had broadcast his intention of becoming a best-selling author some day, was then building up the clandestine army of naval intelligence officers and Royal Marine commandos which was to move out in front of the assault troops on D-Day and capture secret enemy documents and weapons.

He saw in Patrick's flinty blue eyes the look of a man whose mettle has been tested, and promptly signed him on.

Says veteran BBC broadcaster Charles Wheeler, who served with both: "Who could be surprised if a kind of James Bond seed were planted then and there?"

An unconventional childhood

Patrick Dalzel-Job, born in Twickenham, Middlesex, in 1913, was three years old when his father, an infantry officer, was killed in France. His mother, a small, spirited woman, brought him up alone.

They lived on the Sussex coast, then moved to Berkhamsted in Hertfordshire, where Patrick went to school. But he was a sickly boy, inept at team sports and home with mysterious bouts of fever more often than he was in class.

When he was 14, his mother took him to Switzerland, where the mountain air restored his health and he became an expert skier. He continued to read widely in French and English, but his formal education was over.

Drawn to Norway by stories he'd read as a boy, in 1937—the summer of his twenty-fourth birthday—he set sail from Scotland in a 37-foot schooner, Mary Fortune, whose deck work and interior he had built himself.

With his mother as crew, he spent the next two years exploring a wilderness of fiords and islands from Bergen in the south-west to Nordkapp, on the northernmost coast of Europe.

His mother knew nothing of seamanship, but an ingenious array of ropes, chains and pulleys enabled Patrick to man the rugged little schooner single-handed.

Soon he was speaking Norwegian like a native and making friends up and down the western coast. A deep-rooted love for Norway and its people became a cornerstone of his life.

Falling in love with Norway

Wherever he sailed through the complex of waterways, he drew detailed charts, convinced they would be of use to the Royal Navy if war came. But when he sent them to the Admiralty, they were accepted with indifference.

And three years later, when the Germans invaded Norway and coastal charts of any kind were desperately needed, his could not be found.

Meanwhile Patrick, preparing the Mary Fortune for a voyage north to the Arctic Ocean, decided he needed another hand on board and turned to friends in Tromso, the Bangsunds: might one of their children be interested?

The keenest was 13-year-old Bjørg, with her wide blue eyes and a laugh that was the most beautiful sound Patrick had ever heard.

All through that spring and summer, Bjørg was a valiant and valuable shipmate, cheerfully helping out in the galley and learning how to handle the tiller. Then, in early September, their radio brought news that the war had come.

Mary Fortune headed back to Tromso, where all the Bangsunds came to see off Patrick and his mother, their possessions reduced to what they could carry in two suitcases, on the coastal steamer.

As the ship ploughed through the night towards Britain, Patrick found a scrap of paper from Bjørg under his pillow. "I love you," it said.

The nazis and the Norwegians

In April 1940 Patrick, now an officer in the Royal Navy, was again bound for his beloved Norway.

The Nazis, in a brutal move to assure command of the northern sea lanes, had invaded their neutral neighbour, and an Allied expeditionary force was steaming north in an attempt to dislodge them.

Patrick was assigned the task of disembarking the troops at Harstad, 150 miles north of the Arctic Circle, and conveying them to combat staging areas.

This he did by organising fisherman friends, and their friends, into a flotilla of more than 100 of their boats. The objective was nearby Narvik, an ice-free port seized by the Germans as a base from which to protect their supply of vital iron ore from neutral Sweden.

The Norwegians did as Patrick said because they trusted him and he spoke their language; also because he never hesitated to fire a round from his father's old service revolver across their bows when they forgot this was war and not just another fishing trip.

Wearing an unmarked greatcoat over his sub-lieutenant's insignia and barking orders as if born to command, he even had senior officers calling him "Sir".

The Allies captured Narvik—but held it only briefly. They were too few and had come too late. By the end of May, all but a small force had been withdrawn. No one doubted that Luftwaffe bombers would soon be rumbling across the sky, aiming to drive off the rest.

A daring rescue

On May 29 Patrick, standing offshore of the town with his ragtag fishing fleet, learned to his horror that no provision had been made to evacuate the townspeople.

His urgent enquiries only prompted a stern message from force headquarters: he was to hold his boats in reserve and not—"repeat not"—concern himself with the civilian population.

At midnight, a crisis meeting of the city council was still agonising about how they could evacuate the people to the designated safe areas. The then mayor, Theodor Broch, tells what happened next:

"There was a commotion by the door. A young Englishman said he had to talk to me, that we had to evacuate the town. I barked at him that we had no boats."

"I have the boats," said Patrick. "Let's go."

His providential appearance in defiance of strict orders; that clipped self-assurance; rescuing the population of a doomed city—what could have been more James Bondian?

Within the hour, under Patrick's close supervision, women and children were being handed down into the boats.

"I have never forgotten him," says Gerd Carlsson, who was 21 and boarding with her sister and baby nephew. "There was shooting from land and sea, and lines of waiting people, and such a babble of shouting. But he shook each person's hand warmly and was so calm that although I didn't even know where I was going, I wasn't afraid."

During the next two days and nights, 4,500 people were ferried to safety in dozens of communities along the surrounding waterways.

Early on June 2, Patrick and Mayor Broch walked together through Narvik's empty streets, making sure no one was left behind. By then, even the last of the troops had slipped away.

But hours later, while Patrick was still there, the bombers came, turning the town's neat wooden buildings into an inferno, reducing most of them to splinters and ashes.

Patrick watched as Narvik burned, heartsick because he knew there was nothing in the town of military value, only people's homes.

Wartime intelligence

On June 8, Patrick went back to Britain, disillusioned by the Allied defeat, bitter that he hadn't managed to stay behind and organise a Norwegian resistance—and dreading a message from the Admiralty that he was to be court-martialled for gross disobedience of orders at Narvik.

Instead, the Admiralty signalled him with a message from King Haakon VII of Norway: His Majesty would be in London shortly and he would personally present Lieutenant Dalzel-Job with the Knight's Cross of St Olav, Norway's highest order, for saving the people of Narvik.

After that, nothing was heard about a court-martial. But Patrick was relegated to a series of converted merchantmen that zigzagged across the South Atlantic intercepting blockade-breakers or convoying Allied freighters safely to port.

"All this", he recalled in the book he later wrote (and published) about his adventures, "seemed terribly monotonous to me."

Just as he began thinking the war had passed him by, Lord Louis Mountbatten summoned him to London and put him in charge of motor torpedo boat (MTB) operations in Norway. It was particularly dangerous work, for the Germans were throwing all they had into defending Norway's coast.

But Patrick knew plenty of narrow entrance channels that the Germans didn't. His MTBs raised havoc with commando raids, sabotage and attacks on enemy ships.

It forced the Germans to step up defensive operations and induced trepidation quite out of proportion to the number of MTBs employed against them.

Still only a lieutenant, Patrick was next posted to a detachment of midget submarines. In September 1943, he briefed their four-man crews on the remote Arctic estuary where the German battleship Tirpitz was moored in apparent safety; three of the tiny craft crept into the fiord and crippled her in a raid that earned VCs for two of the participants.

Next, equipped with a radio transmitter, he was put ashore on a Norwegian island, on a one-man intelligence mission to track supply convoy patterns through the inland waters.

He knew that capture meant summary execution, on Hitler's own orders. Yet he remembers those three weeks, alone and utterly dependent on his own wit for survival, as among the most exhilarating of his life.

Taken off the island by pre-arrangement, he assuaged his reluctance to leave by directing the MTB that picked him up to a German merchantman whose anchorage he had noted. Two torpedoes finished her off.

James Bond rises through the ranks

On June 10, D-Day-plus-4, Patrick landed on Utah beach in Normandy as a member of Commander Ian Fleming's intelligence hit squad, the 30th Assault Unit (30 AU)—a name intended to mislead, since it was never meant to assault anything and probably took its number from an office door in the Admiralty.

Patrick, promoted to lieutenant-commander, was in command of Team 4, reporting by courier directly to Fleming.

All the way through Normandy, Belgium and into Germany, Team 4 operated ahead of the assault troops in enemy-held territory, getting their hands on German documents, weapons and installations before they could be destroyed by the Germans or by Allied artillery.

Patrick revelled in it; this kind of war, where he was free to set the level of risk, was the kind he wanted to fight. And he sent back a steady stream of data and captured equipment.

He found the control centre for the long-range bombing of Allied convoys in the Atlantic; he recovered intact a new and dangerously effective midget submarine; reaching Cologne 24 hours before any other Allied troops, Team 4 walked unhindered into the vast Schmidding metalworks and took it over.

Patrick's audacity was sometimes breathtaking. When some nuns showed him a heavy safe used by the Germans, he promptly blew it open, breaking every window in the convent. He gave the money in the safe to the nuns for repairs and sent the documents in it to London.

His reports from the field to the desk-bound Ian Fleming kept fleshing out a portrait of the kind of man the would-be writer was conjuring up for his fictional hero. But Patrick's most stunning exploit was still to come.

An impossible stunt

The target was the vast Deschimag shipyard in Bremen where, he had heard from prisoners, there could be as many as 20 of the newest high-speed German submarines—a prize of enormous intelligence value.

But winning it would be a race: the 52nd Lowland Division, following on close behind 30 AU, was planning on blasting the shipyard into oblivion.

In the afternoon of April 26, 1945, Team 4 entered Bremen's deserted central square. A fretful policeman appeared. Please, he said to Patrick in the lead Jeep, would the commander accompany him to the city hall where the mayor was waiting?

Patrick found the mayor, dressed in formal black, alone in the empty, echoing chamber.

"He wanted me to accept the surrender of the city of Bremen and all its services," Patrick recalled, "and he gave me assurances of vigorous police action against any who failed to co-operate fully."

Patrick went at once to radio Army Command that organised military resistance was ended and whatever the Allies wanted would be done. "I told them that, except for some sniping, the city was secure. They didn't have to shell the shipyard."

But the Army did not see it that way. They were going to open fire that very evening, they replied, as soon as they came within range.

Furious, Patrick climbed into his scout car and set out alone for the shipyard, staking his life that there really was no resistance there, and that his presence would keep the Army from shelling it.

Then, at the very gates of the shipyard, his scout car sputtered and died—it had run out of petrol. And when he tried to radio for help, all he got was static; contact had been cut by interference from surrounding buildings.

It's like a bad film, Patrick remembers thinking. But what would happen in the last reel?

He considered going ahead on foot, but needed the rest of his team with the radio truck. Without it, how could he tell the Army he was inside the shipyard? He would only get killed there.

Spotting some workers, he grabbed a bicycle from one of them. Frantically he pedalled back through the sunset to his unit—aware that there was still enough daylight for a sniper to put a bullet in his back.

When he rounded the last corner, his anxiously waiting men hauled him on board the lead vehicle, bicycle and all, and the column sped off for the shipyard at breakneck speed.

Inside, they found 16 brand new submarines and two destroyers, and forestalled their imminent demolition by the shipyard technicians and directors.

Patrick and his men took them all prisoner, and in a night-long search found technical papers detailing the most recent German naval research, as well as machine tools of highly advanced design.

They had not heard the last from the Army. Early next morning, when submarine experts had already begun a detailed study of the captured U-boats, all of the new high-speed Type 21, a British Army staff officer appeared and asked Patrick to sign a receipt for them—implying that the 52nd Division had captured them.

This was the last straw for Patrick. He slammed the gate and had a sign posted on it to the effect that the entire shipyard was the property of 30 AU: "Keep Out!"

Bond gets the girl

The war ended soon after. Patrick never saw Ian Fleming again, nor did the British government reward his wartime valour with even a single honour or citation.

Among those who still wonder why is Rear Admiral Jan Aylen, then a Commander in 30 AU, who calls Patrick "one of the most enterprising, plucky and resourceful people that the Second World War produced".

The reason is not complicated. Frequently Patrick committed the unforgivable offence of disagreeing with senior officers and, worse, being proved right.

Just like James Bond.

As soon as the fighting ended, Patrick responded to the great hunger in his heart and returned to Norway.

Six years had passed; Bjørg was 19 now, a different person. He was different. But as soon as they saw each other, they knew they had only been marking time. They married three weeks later.

The James Bond years, about to begin for Ian Fleming, were over for Patrick. He and Bjørg went to Canada, where Patrick served in the Canadian navy and their son lain grew up.

In 1960 they settled near Plockton in the West Highlands, prepared to continue living happily ever after. Patrick taught in the village school and Bjørg became a pillar of the community until her death, in 1986, of cancer.

Patrick, brave as ever, soldiered on alone. He finally passed away in 2003.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A scout of the Scots Greys reporting by Hermanus Willem Koekkoek

#hermanus willem koekkoek#art#hussars#huzaren#history#europe#cavalry#british#scout#royal scots greys

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Scots Greys Sherman II with a holed barrel and hull cheek in the Netherlands

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

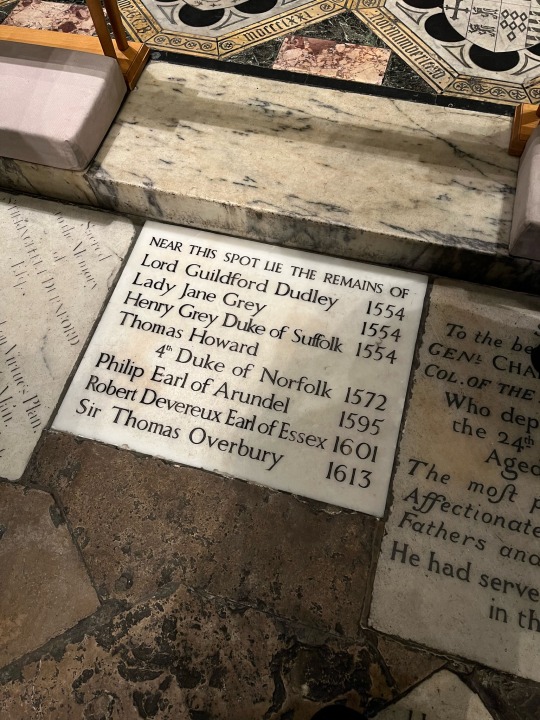

Since I was in the Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula, there were a lot of famous dead people beneath my feet. Under the advent candle in the first photo lie three queens of England: Anne Boleyn, Catherine Howard, and Lady Jane Grey. The stone in the second picture records the location of the remains of Lady Jane Grey’s husband (Lord Dudley) and father (Henry Grey).

Thomas Howard, planned to marry Mary Queen of Scots and also conspired with the Spanish king in the Ridolfi plot to put Mary on the throne.

Philip Howard, Earl of Arundel and son of the man above, was a Catholic martyr and was imprisoned in the tower for ten years before dying of dysentery. He was canonised by Pope Paul VI in 1970.

Robert Devereux, was a general for Elizabeth I. First trial he failed to “subdue” the Irish (good, bastard) and was forbidden from returning to England. Did anyway and marched into the queens chambers when she didn’t have makeup or a wig on. Basically naked in those times. Got banished so tried to stage a coup d’état against Elizabeth. Lost his head.

Sir Thomas Overbury was a poet who had an affair with the daughter of the Earl of Sussex, she tried to make him be rude to Queen Anne, the queen got upset with him so James I/VI offered him to do some pro-Protestant/anti-Catholic ambassadorship that was all the rage at the time (lmao understatement), turned it down, became friends with a man called Robert Carr (who coincidentally married the daughter of the Earl of Sussex), the king was very jealous because he wanted to be friends with Carr and how dare he turn down the job he offered, and threw him in the tower. Where he died after five months.

Anyway that was your random history lesson for the evening

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

The reward of one duty is the power to fulfil another.

George Eliot

HRH Prince Edward, Duke of Kent is one of the most underrated members of the Royal Family, always stoic he’s always been dependable and never flusters, the world needs more 'Steady Eddies'.

There’s no question that the Duke of Kent’s dedication to serving the crown and the country is beyond reproach. For over 50 years, the Duke of Kent has been performing royal duties and on behalf of the monarchy. HRH Prince Edward at a young age filled a huge role vacated by the untimely death of his father in 1942. Since then, the Duke of Kent has ceaselessly spent much of his time performing ceremonial functions, attending charitable causes and supporting various organisations on behalf of his cousin Queen Elizabeth II and the British Monarchy. He has represented Her Majesty in the independence celebrations in the former British colonies of Sierra Leone, Uganda, Guyana, and Gambia. Most recently he has attended the 50th Independence Anniversary Celebration of Ghana. He has also acted as Counselor of State during periods of the Queen's absence abroad.

What is often forgotten is that HRH Prince Edward was a fine soldier. Much like the late Duke of Edinburgh’s naval service was subsumed by his royal persona, the Duke of Kent has never let his royal duties interfere with his army career.

Prince Edward attended Ludgrove in Berkshire for his preparatory education. He then proceeded to Eton College and later in Le Rosey in Switzerland. After school, he attended the Royal Military Academy in Sandhurst, where he won the Sir James Moncrieff Grierson prize for foreign languages. After graduating from Sandhurst in 1955, the duke joined the Royal Scots Grey as Second Lieutenant. That was the start of a military career that spanned over 20 years, one which took him to various places around the world.

In 1961, he was promoted Captain; Major in 1967; and Lieutenant Colonel in 1973. In 1970 the Duke commanded a squadron of his regiment serving in the British Sovereign Base Area in Cyprus, part of the UN force enforcing peace between the Greek and Turkish halves of the island. The duke also spent time commanding a unit in Northern Ireland shortly after the Troubles in the 1970s broke out, but was recalled early on grounds of security.

The duke now maintains his link with the services mainly through honorary rank, which includes that of Colonel of the Scots Guards. He was personal aide-de-camp to his cousin Queen Elizabeth II who promoted him supernumerary Major General on her official birthday in 1983. He was later made a Field Marshal in 1993.

HRH Prince Edward is the longest-serving royal colonel in history. Not just of the Scots Guards but of any regiment in the British Army.

#eliot#george eliot#quote#HRH Prince Edward#duke of kent#british army#british monarchy#monarchy#service#duty#honour#scots guards#regiment#royal scots grey#britain#british

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 June 1971

Queen Elizabeth II, Princess Anne and the Duke of Edinburgh at Horse Guards Parade for the Ceremony of Beating Retreat by Pipes and drums of all Regiments of the Scottish Division, the Scots Guards and the Royal Scots Greys.

#from my drafts#fave trio#queen elizabeth ii#princess anne#princess royal#prince philip#duke of edinburgh

72 notes

·

View notes