#styracosterna

Text

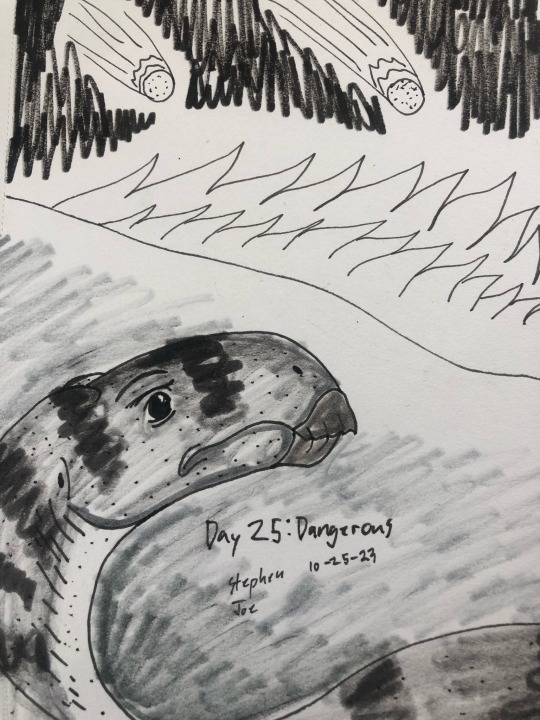

Day 25: Dangerous

A basal styracosterna Calvarius rapidus on the dangerously inferno where the meter showers fell from the sky.

#my art#dinosaur#paleoart#myart#dinosaurs#dinosauria#my drawings#inktober#ink drawing#ornithopoda#iguanodontia#styracosterna#artists on tumblr

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dakotadon

Dakotadon — рід динозаврів із клади Styracosterna інфраряду орнітоподів (Ornithopoda), що включає єдиний вид — Dakotadon lakotaensis. Відомий із формації Лакота на території сучасної Південної Дакоти (США) і датується барремським віком (нижня крейда). Вперше він був описаний під назвою Iguanodon lakotaensis, але в 2008 році Грегорі Пол (Gregory S. Paul) виділив його в окремий рід.…

Повний текст на сайті "Вимерлий світ":

https://extinctworld.in.ua/dakotadon/

#dakotadon#cretaceous#dinosaur#ornithopod#dakota#north america#usa#late cretaceous#styracosterna#paleoart#paleontology#animals#art#daily#extinct#prehistoric#science#illustration#prehistory#fossils#animal art#палеоарт#палеонтологія#ukraine#ukrainian#тварини#україна#українська мова#арт#scientific

1 note

·

View note

Photo

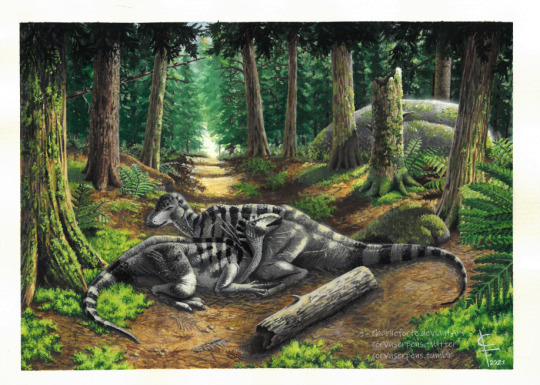

For this #Fossil Friday, I give you the small-to-medium sized Portuguese ornithopod Draconyx loureiroi.

Discovered in 1991 at the Vale de Frades in the Lourinhã Formation, it’s fossils consist of a partial skeleton with no skull, which were described in 2001 by Drs. Octávio Mateus and Miguel Telles Antunes. It was a bipedal herbivore belonging to the Iguanodontia clade, and in a paper published last year by Drs. Filippo Rotatori, Miguel Moreno-Azanza and Octávio Mateus, in which unreported elements of the hand were examined, the genus was tucked into the Styracosterna clade, classifying it as a basal cousin of the famous Iguanodon. Dr. Gregory S. Paul estimated it to be 3.5 meters long.

Draconyx lived during the Late Jurassic period, around 150 million years ago, alongside other dinosaurs such as Miragaia, Allosaurus and Torvosaurus. The holotype specimen ML 357 was around 27 to 31 years old.

Find me on deviantArt and twitter

#palaeoblr#artists on tumblr#dinosaurs#paleoart#fossil friday#palaeoart#dinosaur art#ornithopod#extinct fauna#prehistoric fauna#mesozoic#my art

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 26 of the Juras-Sick Park-Cast: "Control"

is now available on Youtube! Featuring excellent guest @Jordan_Mallon sharing about #tyrannosaurus #triceratops #spiclypeus lumping and splitting and naming new #dinosaurs!

youtube

#JurassicPark #MichaelCrichton

0:00 - Introduction Welcome to the Juras-Sick Park-Cast podcast, the Jurassic Park podcast about Michael Crichton's 1990 novel Jurassic Park, and also not about that, too.

Find the episode webpage at: Episode 26 - Control www.jurassickparkcast.blogspot.com/2022/08/episode-26-control.html

06:17 - Interview with special guest Dr. Jordan Mallon In this episode, my terrific guest Dr. Jordan Mallon returns to chat with me about: Tyrannosaurus imperator, T-regina, and T-rex, amorphous reptile bones, lumping and splitting, species diversity, extinctions, Triceratops trivia, big dinosaurs in Late Cretaceous North America, the bias in the fossil record towards large dinosaurs, naming dinosaurs like Spiclypeus, dinosaur names based on the Jurassic Park film, dinosaurs named in honour of Michael Crichton, dino-mania, styracosterna v. ankylopollexa, comparative anatomy, hadrosaurs v. saurolphines, synonymizing dinosaur names, Gryposaurus, Edmontosaurus v . Ugrunaaluk, phylogenetic mapping, why DNA doesn't preserve (hint, it's water!), and more!

15:00 - Why lumping and splitting different species of dinosaurs?

18:10 - The coolest things about triceratops!

29:15 - Naming dinosaurs, and dinosaurs named after Jurassic Park.

Plus dinosaur news about:

01:25 - Tyrannosaurus imperator, Tyrannosaurus regina and T. rex! Insufficient Evidence for Multiple Species of Tyrannosaurus in the Latest Cretaceous of North America: A Comment on “The Tyrant Lizard King, Queen and Emperor: Multiple Lines of Morphological and Stratigraphic Evidence Support Subtle Evolution and Probable Speciation Within the North American Genus Tyrannosaurus”

03:48 - A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomicrevision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda)

0:33 - Featuring the music of Snale www.snalerock.bandcamp.com/releases

Intro: Supergroovy. Outro: T-Shirts.

The Text: This week’s text is Control, spanning from pages 126 - 133.

01:00:16 - A synopsis of the chapter Control in Jurassic Park Synopsis: As Jurassic Park’s employees conclude their demonstration of all their systems of control, Grant and Malcolm find themselves uneasy with the park’s approach to controlling living, breathing animals in an artificial setting, which is aiming to recreate a natural park setting.

01:06:33 - Analyzing the literary and stylistic techniques

01:13:12 - Discussions surround The Illusion of Control, dinosaurs, Version 4.4, Control is a hoax, Timeline and the God Complex Discussions surround: The Dinosaurs, Version 4.4, Control is a Hoax, the Timeline, and the God Complex.

Side effects: May cause animals like the Gila monster and rattlesnake to share their hemotoxins.

Thank you! The Jura-Sick Park-cast is a part of the Spring Chickens banner of amateur intellectual properties including the Spring Chickens funny pages, Tomb of the Undead graphic novel, the Second Lapse graphic novelettes, The Infantry, and the worst of it all, the King St. Capers. You can find links to all that baggage in the show notes, or by visiting the schickens.blogpost.com or finding us on Facebook, at Facebook.com/SpringChickenCapers or me, I’m on twitter at @RogersRyan22 or email me at ryansrogers-at-gmail.com. Thank you, dearly, for tuning in to the Juras-Sick Park-Cast, the Jurassic Park podcast where we talk about the novel Jurassic Park, and also not that, too. Until next time! #JurassicPark #MichaelCrichton

#Jurassic Park#Michael Crichton#Tyrannosaurus#Triceratops#dinosaurs#novels#podcasts#spiclypeus#paleontology#museums#skeletons#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In a scene very reminiscent of East Africa's Mara River today, a herd of Ouranosaurus steers clear of Sarcosuchus while looking for a place to cross. (The little ornithopods running past are indeterminate and ornamental, according to Luis.)

Ouranosaurus nigeriensis

('brave/courageous reptile from Niger')

Styracosterna Hadrosauriformes

Elrhaz Formation, Ténéré Desert, Agadez, Niger.

Lower Cretaceous, ~112 Ma.

~

Artwork by Luis V. Rey.

Daily Dino Fact #13

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

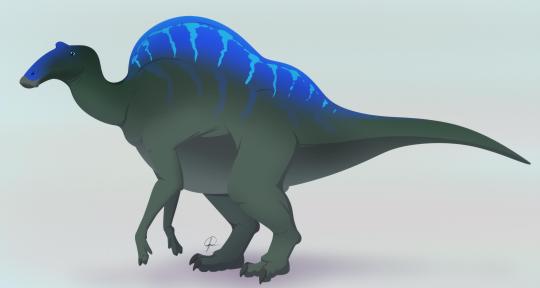

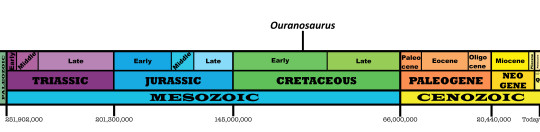

Ouranosaurus nigeriensis

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Brave Reptile of the Sky

First Described By: Taquet, 1976

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Ornithischia, Genasauria, Neornithischia, Cerapoda, Ornithopoda, Iguanodontia, Dryomorpha, Ankylopollexia, Styracosterna, Hadrosauriformes

Status: Extinct

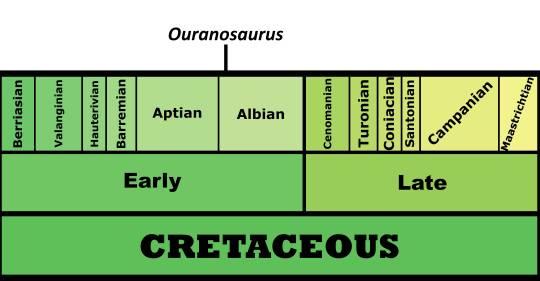

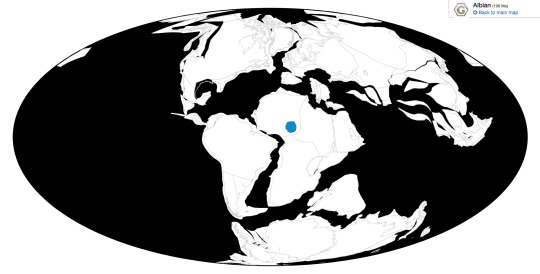

Time and Place: Sometime around 112 million years ago, in the Albian age of the Early Cretaceous

Ouranosaurus is known from the Elrhaz Formation of Agadez, Niger

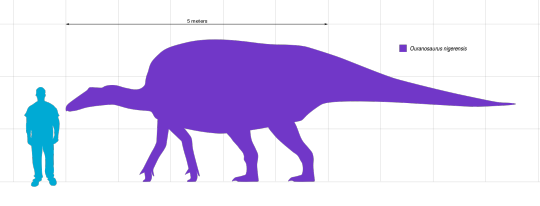

Physical Description: Ouranosaurus is an exceptionally iconic dinosaur, primarily because of its very weird distinguishing physical feature: it has a sail. Probably. The reason for this idea is that Ouranosaurus had extremely high spines on its back, creating a notable ridge along the center of the animal. These spines become thicker and flatten as they go along the body, and bony (ossified) tendons ran across the spines and the tail. The spines grew biggest over the forelimbs, rather than over the hips. This structure may have been a sail; it also could have been a hump containing muscle or fat - similar to living bison and camels. This would have allowed for the storage of energy during the dry season or another time of year. If a sail, this structure would have been primarily one of display, flashing colors and patterns to communicate with other members of the species. It had very long forelimbs with lightly built hands, which had sharp thumb claws and the middle fingers built into a broad hoof-like structure. In short, it was capable of quadrupedal walking. It had very robust hindlimbs as well, and thus was able to walk bipedally in addition to quadrupedally. Ouranosaurus was quite large, reaching 7 meters in length and weighing somewhere around 2.2 tonnes - despite its length, it was fairly lightly built. With its sail, it was just under 3 meters tall. Being of such large size, it is unlikely that Ouranosaurus retained any fluffy covering; if it did, it was sparse and mainly ornamental.

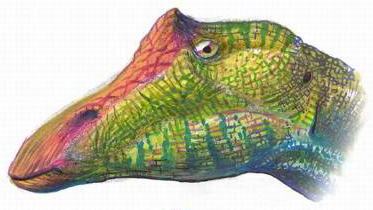

By Slate Weasel, in the Public Domain

It had a very long, flat head, with an even longer snout that greatly surpassed the size of Ouranosaurus’ close relative, Iguanodon. It had a straight beak, rather than a curved one, and no teeth in the front of its snout. The snout also was covered in a sheath of horn, which made it wider and more like something of a beak. This beak was then followed by densely packed batteries of teeth in the cheeks, forming a single surface like those found in the much later Hadrosaurs. The jaws had fairly weak muscles, but this was made up for with a narrow back of the skull, which made the bite ability of the jaws greater to make up for the weak musculature. In short, Ouranosaurus, despite having a very different head than the later Hadrosaurs, was still a strong chewer. Interestingly enough, the eyebrows of Ouranosaurus featured small rounded horns - making Ouranosaurus the only known Ornithopod (Hadrosaurs and their close relatives) with horns. It had highly placed nostrils, and two small bumps between the nose and the eye socket for display.

By Pavel Riha CC BY-SA 3.0

Diet: Ouranosaurus primarily fed on leaves, fruit, and seeds, using its chewing to break up tougher plant material and to gain food from it. Given its decent height, Ouranosaurus would have been a mid-level browser.

By Audrey M. Horn, CC BY-SA 4.0

Behavior: Ouranosaurus would have spent most of its time foraging on a variety of plants in its ecosystem, wandering about the river delta searching for leaves, fruits, and other delicious foods. It is fairly unlikely that Ouranosaurus would have been a herding animal, as herds seemed to have been more of a behavior for Ornithopods more closely related to Hadrosaurs; instead, Ouranosaurus probably wandered about its environment alone, or in small family groups. That said, it almost certainly took care of its young in some capacity, and it did have complex social behaviors if the sail was a sail and used for display - and it used those bumps and horns on its head for display as well. It was also probably at least somewhat vocal. As for the spiked thumbs, those could have been used for defense, as well as in-fighting amongst members of the group. It wouldn’t have been a good runner, but it would have moved on two legs when needing to move at least somewhat faster, and stuck to four legs for most movements throughout the day. It probably would have used that narrow head to selectively grab a variety of foods from in between more dense foliage.

By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Ouranosaurus lived in an extensive river delta, filled with extensive waterways and wetlands. These wide rivers were home to many animals, including a truly extensive number of dinosaurs. Plenty of trees, including ginkgoes and pines, and some flowering plants, in addition to horsetails and ferns, were present for Ouranosaurus to feed on. There were many types of fish and invertebrates, and the turtle Taquetochelys, but the archosaurs were the main stars of the show. There was the duck-croc Anatosuchus, the giant croc Sarcosuchus, and the running croc Araripesuchus on the Crocodylomorph side of things. There was a weirdo sauropod here too, the duck-billed Nigersaurus, which decidedly does not get enough press. As for other ornithopods, there was the fast-running biped Elrhazosaurus, and a close cousin of Ouranosaurus - Lurdusaurus, an equally-weird creature, with a long neck like a sauropod and the ability to live semi-aquatically in the river system. As for theropods, there was the possible Ornithomimosaur Afromimus, the mid-sized carnosaur Eocarcharia, the Abelisaurid Kryptops, and the spinosaur Suchomimus. You will note that Ouranosaurus did not live with Spinosaurus. This is a misconception. The two did not live together - never, not once, not even close, they are not found in the same place. Spinosaurus (probably) comes from later, and while it seems that it did live that southward, it decidedly did not live in the Elrhaz formation, because its job was being done by Suchomimus. As for predators, Ouranosaurus probably had to mostly watch out for Eocarcharia and Kryptops, as they would have been the main land predators of the area.

By Ripley Cook

Other: Ouranosaurus, being a Hadrosauriform, was most closely related to one of the more famous Ornithopods, Iguanodon, and shared the thumb spike in common with it. Interestingly enough, Ouranosaurus wasn’t the only hump or sail backed dinosaur at that point of the family tree; Morelladon, which lived much earlier, also supported some sort of odd structure on its back.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Bailey, J.B. (1997). "Neural spine elongation in dinosaurs: sailbacks or buffalo-backs?". Journal of Paleontology. 71 (6): 1124–1146.

Benton, Michael J. (2012). Prehistoric Life. Edinburgh, Scotland: Dorling Kindersley. p. 338.

Galton, P. M., and P. Taquet. 1982. Valdosaurus, a hypsilophodontid dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Europe and Africa. Géobios 15(2):147-159

Larsson, H. C. E., and B. Gado. 2000. A new Early Cretaceous crocodyliform from Niger. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen 217(1):131-141

McDonald, A.T.; Kirkland, J.I.; DeBlieux, D.D.; Madsen, S.K.; Cavin, J.; Milner, A.R.C.; Panzarin, L. (2010). Farke, Andrew Allen (ed.). "New Basal Iguanodontians from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah and the Evolution of Thumb-Spiked Dinosaurs". PLoS ONE. 5 (11): e14075.

McDonald, A. T., (2011). "The taxonomy of species assigned to Camptosaurus (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda)" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2783: 52–68.

Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 144.

Paul, G.S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press. p. 292.

Sereno, P. C., A. L. Beck, D. B. Dutheil, B. Gado, H. C. E. Larsson, G. H. Lyon, J. D. Marcot, O. W. M. Rauhut, R. W. Sadleir, C. A. Sidor, D. D. Varricchio, G. P. Wilson, and J. A. Wilson. 1998. A long-snouted predatory dinosaur from Africa and the evolution of spinosaurids. Science 282:1298-1302

Sereno, P. C.; H. C. Larsson; C. A. Sidor, and B. Gado. 2001. The giant crocodyliform Sarcosuchus from the Cretaceous of Africa. Science 294. 1516–1519.

Sereno, P. C.; Wilson, J. A.; Witmer, L. M.; Whitlock, J. A.; Maga, A.; Ide, O.; Rowe, T. A. (2007). "Structural extremes in a Cretaceous dinosaur". PLoS ONE. 2 (11): e1230.

Sereno, Paul C., and Stephen L. Brusatte. 2008. Basal abelisaurid and carcharodontosaurid theropods from the Lower Cretaceous Elrhaz Formation of Niger. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 53. 15–49.

Sereno, P. C., and H. C. E. Larsson. 2009. Cretaceous crocodyliformes from the Sahara. ZooKeys 28:1-143

Sereno, P. C., and S. J. ElShafie. 2013. A New Long-Necked Turtle, Laganemys tenerensis (Pleurodira: Araripemydidae), from the Elrhaz Formation (Aptian–Albian) of Niger. In D. B. Brinkman, P. A. Holroyd, J. D. Gardner (eds.), Morphology and Evolution of Turtles 215-250

Taquet, P., 1970, "Sur le gisement de Dinosauriens et de Crocodiliens de Gadoufaoua (République du Niger)", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences à Paris, Série D

Taquet, P. 1976. Geologie et paleontologie du gisement de Gadoufaoua (Aptien du Niger), Cahier Paleont., C.N.R.S. Paris, 1-191

Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp.

#Ouranosaurus nigeriensis#Ouranosaurus#Ornithopod#Dinosaur#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Herbivore#Mesozoic Monday#Dinosaurs#Africa#Cretaceous#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

446 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any resources that could give me a good overall explanation of dinosaur classification? I’m pretty new to paleoblr and I get mixed up with all of the names floating around. Thanks and sorry if I bothered you!

I don’t - but I’ll be happy to write a bit!

1. What is a “Dinosaur”?

This may seem obvious, but it’s a bit more subtle. To scientists, “Dinosauria” is a group containing the most recent creature that was the ancestor of T. rex, Triceratops, and Brontosaurus, and everything descended from that ancestor. This means that birds, as descendants of dinosaurs, are included under that definition, while pterosaurs and most mesozoic sea reptiles like plesiosaurs are not.

This kind of group is called a “node-based group”, and is written as (Tyrannosaurus+Triceratops+Brontosaurus).

There’s also “stem-based groups”, which is “everything closer related to X than to Y”. A good example of this is reptilia, which is something like (Alligator>Homo) [that is, everything closer to alligators than to people!].

2. 3 main groups

There’s three main groups of dinosaurs - theropods, sauropodomorphs, and ornithischians. The simplest (though not always accurate) way of thinking about these is that theropods are two-legged meat-eaters, sauropodomorphs are long-necked plant eaters, and ornithischians are beaked plant-eaters.

For a long time it was accepted that theropods and sauropodomorphs were each others’ closest relatives, in a group called saurischia, and that this group was in turn the closest relatives of ornithischians. Recent analyses show that this may not be entirely accurate - it may be that theropods and ornithischians are united in a group called ornithoscelida, and that sauropodomorphs are the closest relative of this group. There’s good reasons to think each is true, and there’s going to need to be more research done in the future, and hopefully more fossils will straighten things out.

3. Ornithischia

Nearly all ornithischians have three things in common:

They’re mainly herbivores

They have a special bone on their lower jaw called a predentary that formed part of a beak

Part of their hips faces backwards, allowing more room for guts (important because plants are hard to digest!)

There’s three main groups of ornithischians, as well as a bunch that don’t really fit into any of those groups.

The most significant of these “oddballs” are the heterodontosaurs, a group of early ornithischians that mainly lived in the jurassic and triassic periods. They’re generally small (60-200cm in length) two-legged omnivores or herbivores that had big fangs that were probably used for display. They’re kind of the weird cousins of all other ornithischians.

Thyreophorans

This literally means “shield bearers”, and as you might expect it includes the armoured dinosaurs like Stegosaurus and Ankylosaurus. It also includes some weird early forms like Scutellosaurus. It’s defined as (Ankylosaurus>Triceratops).

>Eurypods

This is specifically (Stegosaurus+Ankylosaurus), so it’s contained within thyreophora.

>>Ankylosauria

This is (Ankylosaurus>Stegosaurus), and contains the most heavily armoured dinosaurs. It’s divided into Ankylosauridae (ones with tail clubs), Nodosauridae (which have bigger shoulder spikes), and possibly also Polacanthidae (which have more sticky-up spikes, but also might just be nodosaurids)

>>Stegosauridae

This is (Stegosaurus>Ankylosaurus), and contains the familiar plated dinosaurs. It includes Stegosauridae (the big ones like Stegosaurus) and Huayangosauridae (some smaller Chinese forms).

Neornithischia

This group is defined as (Parasaurolophus>Stegosaurus/Ankylosaurus). It contains two major groups - the Marginocephalians and the Ornithopods, but also a bunch of important basal members, like Thescelosauridae, Kulindadromeus and Hypsilophodon - animals that were once thought to be ornithopods but probably aren’t.

Marginocephalia

This is (Pachycephalosaurus+Triceratops). The name means “rimmed head”, because….both major groups have big stuff around their heads.

>Pachycephalosauria

These are the “bone-headed” dinosaurs like Pachycephalosaurus. It’s (Pachycephalosaurus>Triceratops)

>Ceratopsia

This is (Triceratops>Pachycephalosaurus), and contains the beakiest of all dinosaurs. Chaoyangosaurids are frill-less, hornless, 2-legged forms; Bagaceratopsids, Leptoceratopsids, and Protoceratopsids are hornless but increasingly frilled and 4-legged groups.

>>Ceratopsidae

This is (Centrosaurus+Triceratops), and contains the big, 4-legged, horned guys. Centrosaurines usually have smaller frills with big horns around them, smaller brow horns, and bigger nose horns, while Chasmosaurines usually have bigger frills, bigger brow horns, and smaller nose horns.

Ornithopoda

This is (Parasaurolophus>Triceratops). It used to contain a bunch more stuff, but now it mostly contains just Iguanodonts, so for most purposes those are the same thing (except for some southern forms called Elasmaria that don’t come up much). Doesn’t matter as much as it used to; them’s the breaks. It includes Rhabdodontids, a weirdogroup of small bipedal guys from Europe, and Dryomorpha.

>>Dryomorpha

This is (Dryosaurus+Iguanodon). It contains Dryosauridae, a group of fast-running ornithopods, and Ankylopollexians, the group that had the famous “thumb-spikes).

>>>Styracosterna

Except for a few species, this is about the same as Ankylopollexia. It contains a bunch of species, most of which used to just be called Iguanodon, as well as the Hadrosauriformes, which contains the Hadrosauroids, which contains the Hadrosauromorphs, which contains the Hadrosaurids (whew!)

>>>>Harosauridae

These are the “Duck-bills”. It contains the Lambeosaurines, which had big long hollow crests they could use to HONK !, as well as the Hadrosaurines, which didn’t have hollow crests.

4. Sauropodomorpha

This group is mainly made up of long-necked plant eaters. It starts off with a bunch of things we used to call “Prosauropods”, but now call…….basal sauropodomorphs. It may include Herrersauridae (Pedants be quiet), a group of early, early predators. It probably includes Guaibasaurids, a group of small omnivores from the triassic. It also includes Plateosaurids, a group of larger (but still bipedal), long-necked herbivores. From here we go into Massopoda, a group that includes Massospondylids and Riojasaurids, which…are similar to plateosaurids, as well as Sauropodiformes.

Sauropodiformes is where we start to get more sauropod-y, though we still have to zoom through Anchisauria to get to actual sauropods. We’re there now.

Sauropoda

These guys are actually quadrupedal! Here we’ve got….more sliding groups. There’s a bunch of early sauropods that are quite cool, but I’m not gonna name them. The fun group is Gravisauria. This includes some early guys calls Vulcanodonts, and Eusauropods,

Eusauropods include – you guessed it! More grades. There’s some interesting features here though - Mamenchisaurids are a bunch of Chinese forms with super long necks, and I can’t say I know anything remarkable about Turiasaurs. You’ll have to talk to John about that one.

Neosauropoda

Here’s where you’ll start recognising things if you haven’t already. This is (Saltasaurus+Diplodocus), and contains the most famous sauropods. It’s split into two main groups.

>Diplodocoidea

There are the “whip-tails” (again, pedants be quiet!). It contains Dicraeosaurids, a few weird, short-necked, double sailed things, Rebbachisaurids, a group of wide-mouthed weirdos, and Diplodocids, the famous great swan-necked ones that are some of the largest dinosaurs ever.

>Macronaria

This group contains some basal forms like Camarasaurus, and two main groups (Maybe?? This is kind of a contentious area). Brachiosaurids include the giant, super-tall ones, and some little ones also. Then there’s the monster that is Somphospondyli. This contains….more grades, the Euhelopodids, and the Titanosaurs.

>>Titanosauria.

This is a real monster, let me tell you. It includes more grades – yay! – and Lithostrotia.

>>>Lithostrotia

This is where titanosaurs start getting armoured (except it’s not really that simple, since others have armour, and it may have evolved multiple times, and…..lots of stuff). It also includes the real giants like Lognkosaurs, Aeolosaurs, and Saltasaurs.

5. Theropods

These are the two-legged meat-eaters – although many are omnivorous or herbivorous! They include some early forms and Neotheropods. (From here on, except when notes, groups in big font include the rest of the groups listed below).

Neotheropods

These include the early, long-necked Coelophysoids and Dilophosaurids (which may well be more advanced possibly even Tetenurans!). This group also contains the:

Averostrans

Literally “bird beaks”, although they didn’t all have beaks. It includes the Ceratosaurs, a group that contains some weird forms, and the Abelisaurs (large, short-armed, and bulldog faced) and the Noasaurs (Small, longer arms, need a good orthodontist).

Averostrans also include the:

Tetenurans

Named after their stiffened tails, around here is where theropods lost their fourth finger. After some basal forms it includes the:

>Megalosauroids

These consist of two main groups - the heavily built Megalosaurids and the fish-specialist Spinosaurids.

Tetenurae also includes the:

Avetheropods

This consists of the Carnosaurs and the Coelurosaurs.

>Carnosaurs

These are your big sauropod killers. They include Metriacanthosaurids and Allosaurids, as well as Carcharodontosaurians. This last group is divided into Carcharodontosaurids, which includes some of the largest predators ever to walk the Earth, and the Neovenatorids, a smaller group that MAY contain the Megaraptorans.

The other group of avetheropods is the:

Coelurosaurs

This is the earliest that we can definitively say, with pretty good certainty, that all members had feathers. It includes some basal forms and the:

Tyannoraptors

….which hands-down win the coolest name competition. This group includes the Tyrannosauroids, which I’m sure need no introduction.

It may also include the famously small Compsognathids, but those may also be outside tyrannoraptora.

It also contains the:

Maniraptoriformes

This group is the earliest we can say that all members had wings. It includes the famous “ostrich dinosaurs” or Ornithomimosaurs, and the:

Maniraptora

This group is where we first see the wing-folding ability like in modern birds. It includes the tiny, 1-fingered Alvarezsauroids and, at the other end of the spectrum, the giant, long-necked, pot-bellied, wickedly-clawed, plant-eating Therizinosaurs. It also includes the:

Pennaraptors

This group is the earliest place we see true vaned feathers. It includes the Oviraptorosauria, a group of typically beaked and crested omnivores and herbivores, as well as the

Eumaniraptors

AKA Paravians - it’s the difference between a stem-based and node-based group, but they’re essentially the same.

This group includes the really birdy things, like Anchiornis and the dragon-like Scansoriopterygids (really rolls off the tongue after some practice, I promise!). It also includes the famous “Raptors” – the Dromaeosaurids. There’s also the sickle-clawed but more omnivorous or herbivorous Troodontids, famous for their brains. This latter group may be a sister group to Dromaeosauridae, or it may be closer to:

Avialae

This is (Passer>Troodon, Deinonychus). It’s what most scientists would call “birds”. It includes some early forms exemplified by Archaeopteryx and Jeholornis, as well as:

Pygostylia

This is birds with shortened, fused tails. It’s (Confuciusornis+Passer), and includes the cool streamer-tailed Confuciusornithids. It also includes:

Ornithothoraces

This group of birds is (Enantiornis+Passer). It includes the very successful and widespead (but now extinct) bird group called the Enantiornithines. It also includes the

Euornithines

This is where we first see birds with modern-style tails. It includes some basal forms at the

Ornithuromorphs

This group contains some early groups, the Hongshanornithids and the Songlingornithids, and the:

Ornithurans

This is sort of the “last burst” before we get to true birds! It includes the seagull-like Ichthyornis and the seal-like Hesperornithines. From here on out, everything is included in the:

Neornithines

We’ve made it! This is true birds - no teeth here. From here we’re divided into – What, did you think we were done? – we’re divided into the Palaeognaths and the Neognaths.

Palaeognaths include giant flightless birds like ostriches and emus, as well as the kiwi and the chicken-like Tinamids.

Neognaths

This contains all the familiar birds.

One major group is the Galloanserans.

These include the Odontoanseres, possibly* including the albatross-like Pelagornithids as well as the famous “horse-eating” (but actually vegetarian) Gastornithids and Dromornithids, and ducks, geese, swans, and screamer birds in Anseriformes.

*Pelagornithids may be more basal galloanserans or neognaths

Galloanserae also includes Pangalliformes, which consists of megapode fowl, chickens, turkeys, pheasants, peacocks, the whole shebang.

Neognathae also includes the:

Neoaves

From here taxonomy does get a bit muddled for a while. I’ll present the two major hypotheses.

1. Columbea/Passerea hypothesis

The Columbimorphs consists of Columbiformes or pigeons and doves, Pteroclidoformes or sandgrouse, and Mesitornithiformes or Mesites.

Columbimorphs may be closest to Mirandornithes, which consists of Phoenicopteriformes or flamingoes, and Podicepidiformes or grebes. If so, this clade is called Columbea.

The rest of the birds in this hypothesis belong in a clade called Passerea.

Otidomorphs are a group consisting of Otidids or bustards, Cuculiformes or cuckoos, and Musopagoformes or turacos.

Otidomorphs may be closest to Strisores, which include Apodiformes (Hummingbirds and swifts) and Caprimulgiformes (Nightjars, owlet-nightjars, and frogmouths). In this case their clade is Otidae, not to be confused with Otididae.

The rest of the birds in this hypothesis clade together in a clade called Litoritelluraves.

Gruae may be a group consisting of Opisthocomids (Hoatzins), Charadriiformes (Gulls, terns, puffins, plovers, sandpipers), and Gruiformes (Cranes, rails).

The rest of the birds in this hypothesis clade together in an unnamed clade.

This group contains the Telluraves (more on them later!) and the:

Ardeae

This consists of Eurypygimorphs, consisting of Eurypigids (Sunbitterns) and Phaethoniformes (Tropicbirds).

Ardeae may also include:

Aequornithes

This group of waterbirds includes Gaviiformes (divers/loons), Austrodyptornithes (a clade that includes Sphenisciformes [Penguins] and Procellariiformes [Albatrosses, petrels]), Ciconiiformes (Storks), Suliformes (Boobies, gannets, cormorants), and Pelicaniformes (Pelicans, herons, ibises).

2. Columbaves Hypothesis

Strisores may be the earliest to branch off of Neoaves.

Columbimorphs may alternatively be closest to Otidomorphs, If so, this clade is called Columbaves.

The rest of the birds in this hypothesis clade together in an unnamed clade.

Gruiformes may have been the earliest to branch off in this clade.

The rest of the birds in this hypothesis clade together in an unnamed clade.

The Aequorlitornithes (Not to be confused with Aequornithes) may consist of Mirandornithes clading with Charadriiformes as a sister group to a clade between Eurypygimorphs and Aequornithes.

Also included in this unnamed clade is the

Inopaves

This may consist of Opisthocomids and Telluraves.

Telluraves – Back to your regularly scheduled program

There’s actually, to my knowledge, some degree of concensus here. It’s divided into two main groups - Afroaves and Australaves.

Australaves consists of Cariamiformes (seriemas and terror birds) and Eufalconimorphae.

>Eufalconimorphae consists of Falconiformes (Falcons, kestrels, and caracaras), as well as Psittacopasserans.

>>Psittacopasserans consist of Psittacoformes (Parrots and their ilk) and Passeriformes (Perching birds, which I’m not going into more detail on because I’d be here for a month).

Afroaves

This clade consists of Accipterimophs (New-world vultures, hawks, eagles, old-world vultures, kites), and an unnamed clade.

Unnamed clade

This clade consists of Strigiformes (owls and kin) and Coraciimorphs.

Coraciimorphs

This clade consists of Coliiformes (mousebirds), the cuckoo-roller, and Cavitaves.

Cavitaves

This clade consists of the Trogonids (Trogons and Quetzals) and the Picocoraciae.

Picocoraciae

This clade consists of Bucerotiformes (Hornbills, hoopoes, woodhoopoes) and the Picodynastornithes.

Picodynastornithes

Last one! This consists of Coraciiformes (Kingfishers, rollers, motmots, and bee eaters), and the Piciformes, or toucans, barbets, and woodpeckers.

230 notes

·

View notes

Text

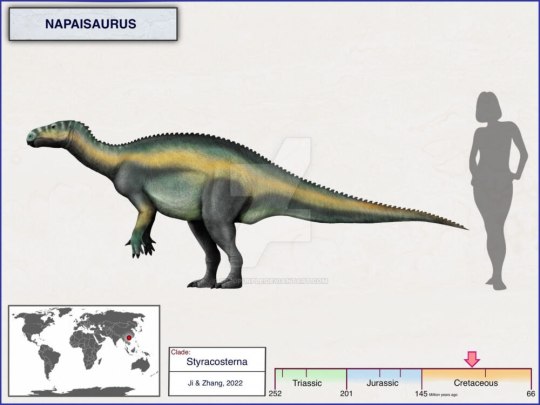

Napaisaurus

Napaisaurus (лат.) – рід птахотазових динозаврів клади Styracosterna, відомий по викопним решткам з відкладень нижньокрейдової формації Сіньлун на півдні Китаю. Включає єдиний вид – Napaisaurus guangxiensis.

Повний текст на сайті "Вимерлий світ":

https://extinctworld.in.ua/napaisaurus/

#napaisaurus#styracosterna#napaisaurus guangxiensis#china#cretaceous#cretaceous period#paleontology#paleoart#палеоарт#палеонтологія#prehistoric#вимерлі тварини#доісторичні тварини#extinct animals#made in ukraine#ukraineposts#ukraine

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

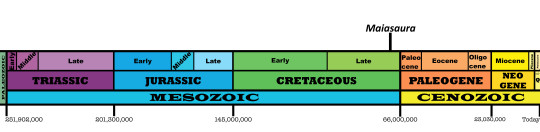

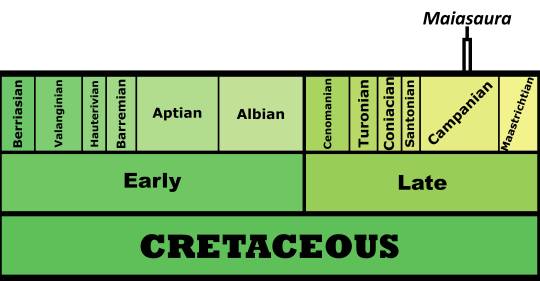

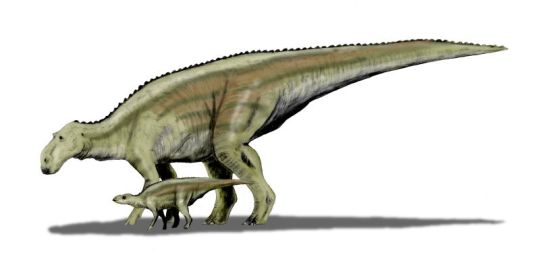

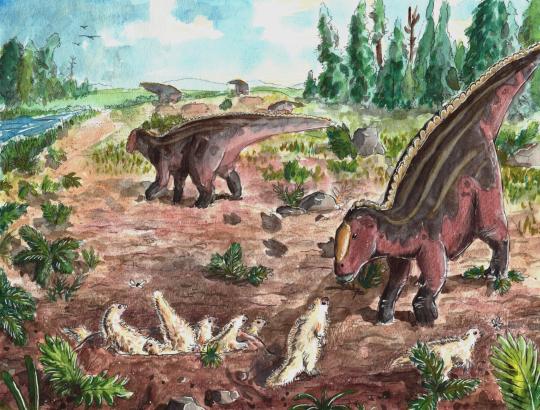

Maiasaura peeblesorum

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Good Mother Reptile

First Described By: Horner & Makela, 1979

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Ornithischia, Genasauria, Neornithischia, Cerapoda, Ornithopoda, Iguanodontia, Dryomorpha, Ankylopollexia, Styracosterna, Hadrosauriformes, Hadrosauroidea, Hadrosauromorpha, Hadrosauridae, Euhadrosauria, Saurolophinae, Brachylophosaurini

Status: Extinct

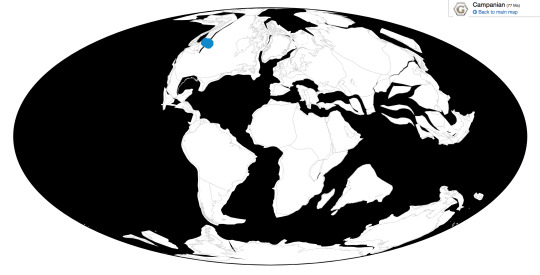

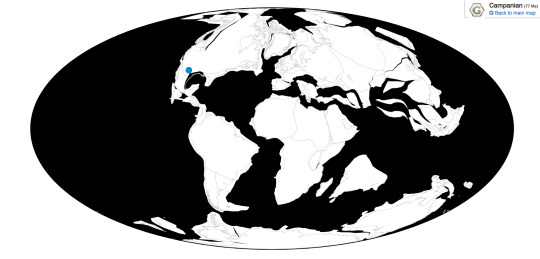

Time and Place: Between 77.2 and 76.3 million years ago, in the Campanian of the Late Cretaceous

Maiasaura is known from the Upper member of the Two Medicine Formation in Montana

Physical Description: Maiasaura was a medium-sized hadrosaur - aka, a “duck-billed” dinosaur. Famed for being known from hundreds of individual skeletons, we have a general idea of the appearance of this dinosaur at every stage of its life cycle. Baby Maiasaura were around 0.4 meters in length and were positively tiny in weight, weighing less than 250 kilograms. These babies were adorable in appearance: with large eyes, small heads, and small limbs. The limbs were very weak and skinny at this point in life. Despite this extremely small size, Maiasaura young grew quickly - growing to 1.5 meters in length by the first year, and reaching sexual maturity at about the age of three or so, when they weighed around 1250 kilograms. Full skeletal maturity then came at about five years of age. At this point, Maiasaura were as much as 3000 kilograms in weight, and reaching 9 meters in length. Maiasaura adults were much beefier than the young - with thick, strong hind legs and somewhat more gracile front legs, it was almost as if they had deer front legs and elephant hind legs. The front feet formed hoof-like structures - with the pinky and thumb both sticking out, the middle three fingers were fused together. The hind limbs were typical ornithopod feet, with three toes splayed out like that of a very thick bird. Their tails were thick and muscular, and their torsos also very beefy. They had very thick, muscular necks as well.

By Ripley Cook

The heads of Maiasaura were rectangular and long, with flattened duck bills in the front. In the jaws, there were rows upon rows of densely packed teeth, forming a single surface. This surface was essentially serrated with the number of teeth packed in there. The upper jaws could then expand, allowing the lower jaws to slide upwards into them, creating a chewing motion. The more duck-like front bill was used to snip off plants and bring them into the jaw. Maiasaura also had a very large nose, forming a sort of lump in the front of the snout - this would have helped keep the head cool, and also allowed Maiasaura to make a variety of calls without a hollow crest attached. Above the eyes the skull of Maiasaura was domed with the brain area. In front of the eyes, on the top of the skull, there was a little ridged crest for display. It is logical to suppose that said crest would be somewhat patterned or even colorful, for display.

By Nobu Tamura, CC BY 3.0

Scale impressions from Maiasaura are known. Adults of this species were entirely scaley, with almost a pebble-like texture of scales covering the entire body. These small round patches didn’t seem to overlap much, but were densely packed and not leaving much in the way of bare skin showing. Very small ones no longer than 2 millimeters were interspersed with bigger, more hexagonal ones at five to ten millimeters long. It is possible that fuzz would extend between the scales, but they would have looked rather like plants growing between sidewalk scales, and fairly impossible to see ultimately. The back was bumpy from the spine, and rather high over the animal - making Maiasaura itself quite tall. The scales were even bigger on this portion of the animal. Though skin impressions are known from Maiasaura adults and close relatives, baby Maiasaura do not have preserved skin impressions. What this means is that, while it seems very logical they’d also be scaly, there is a possibility they were fluffy to stay warm, given their smaller size. We present one hypothetical reconstruction of such for you all below, with the caveat that it is purely speculation at this time.

By Diane Ramic

Diet: Maiasaura, like other hadrosaurs, fed mainly on soft, wet vegetation at low and middle levels of browsing (rather more tough, hard, dry vegetation like scrub plants and desert brush). So, it would favor leaves, berries, and more tender shoots, as well as plants in sources of water.

By Madchester, in the Public Domain

Behavior: Maiasaura was a highly social, active animal - warm blooded in energy levels, these dinosaurs would have spent most of their time, each and every day, wandering around looking for food and socializing with other members of the herd. They spent a good portion of their time taking care of their young, of course, but that was only during the breeding season. Nests were made in large breeding colonies, not unlike their modern bird relatives such as seabirds, with gaps between nests only 7 meters long - less than the length of the adults that had to move between them! Between thirty and forty eggs were laid in a dense spiral pattern, and these eggs were the size of an ostrich’s today. Rotting vegetation was placed upon the nest to keep it warm. The babies, not able to take care of themselves upon hatching, entirely relied on their parents to bring them back chewed up food and look out for their safety. Sadly, most of the young would still die in the first year of life - mainly due to disease and predation, up to 90% of the young would die in the first year of life. Still, the parents did their best - with the young having features associated with cuteness, indicating dependence on the parents for survival until they reached larger sizes.

By Debivort, CC BY-SA 3.0

Past that point, however, as the young grew faster, they fared better in terms of mortality - dropping down to 12% mortality until reaching old age again. They began to move on their own and keep up with the herd as it moved about. Young Maiasaura would walk on two legs, and as they got heavier they would switch to four, still sometimes only using the hind limbs when needed. Upon reaching sexual maturity at around three years of age, they began to get even bulkier. The Maiasaura would live in herds hundreds of individuals large, which would have been very noisy - using those bulky nostrils to make very loud, differing calls. Come mating time, they would display to each other with the ridges on their heads and other patterns. It is uncertain who was in charge of caring for the young, as sexual dimorphism isn’t seen in the skeletons of Maiasaura - if it was just the mother, both parents, just the father, or even the parents and previous children, we do not know at this time. The herd structure would protect the young, the sick, and the old from predators, and they would probably call to each other to ensure that they stayed safe in the face of predation. That being said, most of the rest of Maiasaura would then die in old age, with the death rate jumping up to 44% at the oldest ages of 12 to 14, when their own weight, slowness, and illness would leave them more vulnerable to predators.

By Fabrizio De Rossi, retrieved from Earth Archives

Ecosystem: The Two Medicine Formation was one of the most iconic dinosaur ecosystems of all time, sort of a precursor in many ways to the more famous Hell Creek, but with more variety and dinosaur diversity! Here was a very large floodplain, filled with rivers and deltas and associated plantlife on sandy riverbanks. This environment was highly associated with the ever-present Western Interior Seaway, much like the later Hell Creek. It was seasonally arid, with rainshadows from the nearby Cordilleran Highlands, which may have been at least somewhat volcanic. This made the Two Medicine Environment positively volatile - with flash flooding, droughts, dehydration, and volcanic activity all allowing for the animals in this region to be wonderfully preserved (allowing us to know so much about Maiasaura)! Plants would grow very rapidly each wet season, making the area a very lush habitat for about half the year, allowing for all these dinosaurs to congregate here. This environment was filled with conifers and pine trees primarily, though there were also other types of plants as well. There were non-dinosaurs here as well - the pterosaurs Montanazhdarcho and Piksi, the Choristodere Champsosaurus, unnamed crocodylians, lizards like Magnuviator, mammals such as Cimexomys, Paracimexomys and Alphadon, and a wide variety of turtles like Basilemys.

By Sam Stanton

Still, dinosaurs were the primary feature of the later (Upper) Two Medicine environment where Maiasaura frequented. There were four different types of Ceratopsians: the flat-nosed Achelosaurus, the curved-horned Einiosaurus, the giant-horned Rubeosaurus/Styracosaurus (depending on who you talk to, lumping-wise), and the small herbivore Prenoceratops. Ankylosaurs came in three different varieties - the large-spined but wiggle-taled Edmontonia, and the wide tail-clubbed Dyoplosaurus and Scolosaurus. Other hadrosaurs shared this environment with Maiasaura, like the large-nosed Gryposaurus, the round-crested Hypacrosaurus, and the small pointed crest having Prosaurolophus. There was also the small, active burrower Orodromeus. As for theropods, there were two different raptors - Bambiraptor and Richardoestesia - which would have been major problems for younger Maiasaura and the babies and eggs. The predatory opposite-bird, Gettyia, would have also been a predator of these smaller individauls. The troodontid Saurornitholestes would have been a major danger to these young Maiasaura along with its close cousins. The adults, on the other hand, had not one but two different species of tyrannosaur to contend with: the bulky and rarer Daspletosaurus, and the more slender Gorgosaurus that has been hypothesized to feed more on hadrosaurs than its cousin (though this is under hot debate). In short, this was the place to be to see just how diverse and fascinating non-avian dinosaurs were right at the end of their tenure, and Maiasaura was a major part (if not the most common part) of that ecosystem.

By Scott Reid

Other: Maiasaura is the closest thing non-avian dinosaurs get to a “model organism” - a creature with enough specimens, research, and data about it to use it as an example for other animals which we know less about. With hundreds of specimens found and counting, we have recorded a complete growth sequence of this dinosaur, knowing what the trajectory of a typical Maiasaura life was like. This is of vital importance, as hadrosaurs were some of the most diverse dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous - the end of the time of non-avian forms. It is also fascinating for how much the life history of Maiasaura - a dinosaur not close to being a bird by any stretch of the imagination - is so similar to birds. With similar rapid growth rates as their warm-blooded cousins, and similar nesting and group living strategies, Maiasaura showcases how complex behavior and lifestyles were common over the entirety of the dinosaur group. Maiasaura is also of fundamental importance because, with its discovery and descriptions in the late 1970s, it served with Deinonychus to show how dinosaurs weren’t slow, sluggish, giant lizards - but active, warm-blooded avian precursors. Dinosaurs were active, behaviorally complex, and took care of their young - something that was a truly revolutionary statement before these dinosaurs were named! So, despite not really looking like much, Maiasaura is probably one of the most important dinosaur discoveries ever found. Maiasaura itself is closely related to dinosaurs such as Brachylophosaurus, and is in general part of the “crestless” hadrosaur group, along with the contemporary Gryposaurus and the later Edmontosaurus.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Arbour, Victoria M.; Currie, Philip J. (8 May 2013). "Euoplocephalus tutus and the Diversity of Ankylosaurid Dinosaurs in the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada, and Montana, USA". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e62421.

Atterholt, J.; J. Howard Hutchison; Jingmai K. O’Connor (2018). "The most complete enantiornithine from North America and a phylogenetic analysis of the Avisauridae". PeerJ. 6: e5910.

Bailleul, A. M., B. K. Hall, and J. R. Horner. 2013. Secondary cartilage revealed in a non-avian dinosaur embryo. PLoS ONE 8(2):e56937:1-5

Bell, P. R. 2014. A review of hadrosaurid skin impressions. In D. A. Eberth & D. C. Evans (ed.), Hadrosaurs 572-590

Bell, P. R., R. Sissons, M. E. Burns, F. Fanti, and P. J. Currie. 2014. New saurolophine material from the upper Campanian-lower Maastrichtian Wapiti Formation, west-central Alberta. In D. A. Eberth & D. C. Evans (ed.), Hadrosaurs 174-190

Bonaparte, J. F., Novas, F. E., & Coria, R. A. (1990). Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte, the horned, lightly built carnosaur from the Middle Cretaceous of Patagonia. Contributions in Science. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 416, 1-42.

Campione, N. E., K. S. Brink, E. A. Freedman, C. T. McGarrity, and D. C. Evans. 2013. ‘Glishades ericksoni’, an indeterminate juvenile hadrosaurid from the Two Medicine Formation of Montana: implications for hadrosauroid diversity in the latest Cretaceous (Campanian-Maastrichtian) of western North America. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments 93:65-75

Carr, Thomas D.; J. Varricchio, David; C. Sedlmayr, Jayc; M. Roberts, Eric; R. Moore, Jason (30 March 2017). "A new tyrannosaur with evidence for anagenesis and crocodile-like facial sensory system". Scientific Reports. 7: 1–11.

Carroll, R. L.. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Carroll, N. REASSIGNMENT OF MONTANAZHDARCHO MINOR AS A NON-AZHDARCHID MEMBER OF THE AZHDARCHOIDEA, SVP 2015.

Chapman, R., and M. K. Brett-Surman. 1990. Morphometric observations on hadrosaurid ornithopods. In K. Carpenter and P. J. Currie (eds.), Dinosaur Systematics: Perspectives and Approaches, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 163-177

Chinnery, Brenda J.; Horner, John R. (2007). "A New Ceratopsian Dinosaur Linking North American and Asian Taxa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (3): 625–641.

Cruzado-Caballero, P., X. Pereda-Suberbiola, and J. I. Ruiz-Omeñaca. 2010. Blasisaurus canudoi gen. et sp. nov., a new lambeosaurine dinosaur (Hadrosauridae) from the latest Cretaceous of Arén (Huesca, Spain). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 47:1507-1517

Cruzado-Caballero, P., and J. E. Powell. 2017. Bonapartesaurus rionegrensis, a new hadrosaurine dinosaur from South America: implications for phylogenetic and biogeographic relations with North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 37(2):e1289381:1-16

Cubo, Jorge; Woodward, Holly; Wolff, Ewan; Horner, John R. (2015). "First Reported Cases of Biomechanically Adaptive Bone Modeling in Non-Avian Dinosaurs". PLoS ONE. 10 (7): e0131131.

Currie, Trexler, Koppelhus, Wicks and Murphy (2005). "An unusual multi-individual tyrannosaurid bonebed in the Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) of Montana (USA)." P.p. 313-324 in Carpenter, K. (ed.), The Carnivorous Dinosaurs. III. Theropods as living animals.

Czerkas, S. A. (1992). Discovery of dermal spines reveals a new look for sauropod dinosaurs. Geology, 20(12), 1068-1070.

D’Emic, M. D. 2015. Comment on “Evidence for mesothermy in dinosaurs.” Science 348 (6238): 982.

Davis, M. (2012). Census of dinosaur skin reveals lithology may not be the most important factor in increased preservation of hadrosaurid skin. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 59(3), 601-605.

Dilkes, D. W. 1999. Appendicular myology of the hadrosaurian dinosaur Maiasaura peeblesorum from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) of Montana. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 90 (2): 87 - 125.

Dilkes, D. W. 2001. An ontogenetic perspective on locomotion in the Late Cretaceous dinosaur Maiasaura peeblesorum (Ornithischia: Hadrosauridae). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 38(8), 1205-1227.

Dodson, P. 1975. Taxonomic implications of relative growth in lambeosaurine hadrosaurs. Systematic Zoology 24:37–54.

Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B. The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 116-117.

Dodson, P., C.A. Forster, and S.D. Sampson. 2004. Ceratopsidae in Weishampel, D.B., P. Dodson, and H. Osmolska (eds.) The Dinosauria. 2nd Edition, University of California Press.

Farke, A. A., D. J. Chok, A. Herrero, B. Scolieri, and S. Werning. 2013. Ontogeny in the tube-crested dinosaur Parasaurolophus (Hadrosauridae) and heterochrony in hadrosaurids. PeerJ 1:e182.

Farlow, James O.; Pianka, Eric R. (2002). "Body size overlap, habitat partitioning and living space requirements of terrestrial vertebrate predators: implications for the paleoecology of large theropod dinosaurs". Historical Biology. 16 (1): 21–40.

Federico L. Agnolin & David Varricchio (2012). "Systematic reinterpretation of Piksi barbarulna Varricchio, 2002 from the Two Medicine Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of Western USA (Montana) as a pterosaur rather than a bird" (PDF). Geodiversitas. 34 (4): 883–894.

Forster, C. A., and P. C. Sereno. 1994. Phylogenetic analysis of hadrosaurid dinosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14(3, suppl.):25A

Forster, C. A. 1997. Hadrosauridae. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 293-299

Fowler, D. W. 2017. Revised geochronology, correlation, and dinosaur stratigraphic ranges of the Santonian-Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) formations of the Western Interior of North America. PLoS ONE 12 (11): e0188426.

Gates, T. A., J. R. Horner, R. R. Hanna and C. R. Nelson. 2011. New unadorned hadrosaurine hadrosaurid (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) from the Campanian of North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31(4):798-811

Godefroit, P., Z.-M. Dong, P. Bultynck, H. Li, and L. Feng. 1998. New Bactrosaurus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauroidea) material from Iren Dabasu (Inner Mongolia, P. R. China). Bulletin de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre 68(supplement):3-70

Godefroit, P., V. R. Alifanov, and Y. L. Bolotsky. 2004. A re-appraisal of Aralosaurus tuberiferus (Dinosauria, Hadrosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Kazakhstan. Bulletin de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Science de la Terre 74(supplement):139-154

Godefroit, P., S. Hai, T. Yu and P. Lauters. 2008. New hadrosaurid dinosaurs from the uppermost Cretaceous of northeastern China. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 53(1):47-74

Grady, J. M., B. J. Enquist, E. Dettweiler-Robinson, N. A. Wright, F. A. Smith. 2014. Evidence for mesothermy in dinosaurs. Science 344 (6189): 1268-1272

Guenther, M. F. 2009. Influence of sequence heterochrony on hadrosaurid dinosaur postcranial development. The Anatomical Record 292:1427-1441

Horner, J. R., and R. Makela. 1979. Nest of juveniles provides evidence of family structure among dinosaurs. Nature 282:296-298

Horner, J. R. 1983. Cranial osteology and morphology of the type specimen of Maiasaura peeblesorum (Ornithischia: Hadrosauridae), with discussion of its phylogenetic position. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 3(1):29-38

Horner, Jack and Gorman, James. (1988). Digging Dinosaurs: The Search that Unraveled the Mystery of Baby Dinosaurs, Workman Publishing Co.

Horner, J. R. 1992. Cranial morphology of Prosaurolophus (Ornithischia: Hadrosauridae) with descriptions of two new hadrosaurid species and an evaluation of hadrosaurid phylogenetic relationships. Museum of the Rockies Occasional Paper 2:1-119

Horner, J. R., A. De Ricqles, K. Padian. 2000. Long bone histology of the hadrosaurid dinosaur Maiasaura peeblesorum: growth dynamics and physiology based on an ontogenetic series of skeletal elements. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20 (1): 115 - 129.

Horner, J. R., Schmitt, J. G., Jackson, F., & Hanna, R. (2001). Bones and rocks of the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine-Judith River clastic wedge complex, Montana. In Field trip guidebook, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 61st Annual Meeting: Mesozoic and Cenozoic Paleontology in the Western Plains and Rocky Mountains. Museum of the Rockies Occasional Paper (Vol. 3, pp. 3-14).

Horner, J. R., D. B. Weishampel, and C. A. Forster. 2004. Hadrosauridae. In D. B. Weishampel, H. Osmolska, and P. Dodson (eds.), The Dinosauria (2nd edition). University of California Press, Berkeley 438-463

Hunt, A. P., and S. G. Lucas. 1992. Stratigraphy, paleontology and age of the Fruitland and Kirtland formations (Upper Cretaceous), San Juan Basin, New Mexico. In S. G. Lucas, B. S. Kues, T. E. Williamson & A. P. Hunt (eds.), New Mexico Geological Society, 43rd Annual Fall Field Conference, San Juan Basin IV, Guidebook 43:217-239

Kirkland, J. I., R. Hernández-Rivera, T. A. Gates, G. S. Paul, S. J. Nesbitt, C. I. Serrano-Brañas, and J. P. Garcia-de Garza. 2006. Large hadrosaurine dinosaurs from the latest Campanian of Coahuila, Mexico. In S. G. Lucas and R. M. Sullivan (eds.), Late Cretaceous Vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 35:299-315

Lehman, T. M., 2001, Late Cretaceous dinosaur provinciality: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, pp. 310–328.

Lehman,T. M., S. L. Wick, and J. R. Wagner. 2016. Hadrosaurian dinosaurs from the Maastrichtian Javelina Formation, Big Bend National Park, Texas. Journal of Paleontology 90(2):333-356

McFeeters, B., Evans, D., & Maddin, H. (2018, May). Variation in the braincase and cranial ornamentation of Maiasaura peeblesorum (Ornithischia, Hadrosauridae) from the Campanian Two Medicine Formation of Montana: implications for brachylophosaurin ontogeny and evolution. In 6th Annual Meeting Canadian Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology May 14-16, 2018 Ottawa, Ontario (p. 37).

McGarrity, C. T.; Campione, N. E.; Evans, D. C. (2013). "Cranial anatomy and variation in Prosaurolophus maximus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 167 (4): 531–568.

Morris, W. J. 1970. Hadrosaurian dinosaurs bills–morphology and function. Los Angeles County Museum Contributions in Science 193:1–14.

Osborn, H. F. (1912). Integument of the iguanodont dinosaur Trachodon. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History v. 1

Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 148.

Penkalski, P. (2013). "A new ankylosaurid from the late Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana, USA". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Pereda-Suberbiola, X., J. I. Canudo, P. Cruzado-Caballero, J. L. Barco, N. López-Martínez, O. Oms, and J. I. Ruiz-Omeñaca. 2009. The last hadrosaurid dinosaurs of Europe: a new lambeosaurine from the uppermost Cretaceous of Aren (Huesca, Spain). Comptes Rendus Palevol 8:559-572

Prieto-Márques, A., R. Gaete, G. Rivas Galobart and M. Boada. 2006. Hadrosauroid dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Spain: Pararhabdodon isonensis revisited and Koutalisaurus kohlerorum, gen. et. sp. nov. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26(4):929-943

Prieto-Márquez, A. 2010. Glishades ericksoni, a new hadrosauroid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Late Cretaceous of North America. Zootaxa 2452:1-17

Prieto-Marquez, A., and G. C. Salinas. 2010. A re-evaluation of Secernosaurus koerneri and Kritosaurus asutralis (Dinosauria, Hadrosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30(3):813-837

Prieto-Márquez, A., and J. R. Wagner. 2010. Pararhabdodon isonensis and Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus: a new clade of lambeosaurine hadrosaurids from Eurasia. Cretaceous Research 30:1238-1246

Prieto-Marquez, A. 2013. Skeletal morphology of Kritosaurus navajovius(Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of the North American south-west, with an evaluation of the phylogenetic systematics and biogeography of Kritosaurini. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology

Prieto-Márquez, A.; Wagner, J.R. (2013). "A new species of saurolophine hadrosaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of the Pacific coast of North America". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 58 (2): 255 - 268.

Prieto-Marquez, A., & Guenther, M. F. (2018). Perinatal specimens of Maiasaura from the Upper Cretaceous of Montana (USA): insights into the early ontogeny of saurolophine hadrosaurid dinosaurs. PeerJ, 6, e4734.

Ramírez-Velasco, A. A., M. Benammi, A. Prieto-Marquez, J. Alvarado Ortega, and R. Hernández-Rivera. 2012. Huehuecanauhtlus tiquichensis, a new hadrosauroid dinosaur (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda) from the Santonian (Late Cretaceous) of Michoacán, Mexico. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 49:379-395

Rogers, R.R. (1990). "Taphonomy of three dinosaur bone beds in the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of northwestern Montana: evidence for drought-related mortality". PALAIOS. 5 (5): 394–413.

Russell, D. A. (1970). "Tyrannosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of western Canada". National Museum of Natural Sciences Publications in Paleontology. 1: 1–34.

Russell, D. A. 1984. A check list of the families and genera of North American dinosaurs. Syllogeus 53:1-35

Sullivan, R. M.; Lucas, S. G. (2006). "The Kirtlandian land-vertebrate "age"–faunal composition, temporal position and biostratigraphic correlation in the nonmarine Upper Cretaceous of western North America". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 35: 7–29.

Tan, Q. W., H. Xing, Y.-G. Hu, L. Tan, and X. Xing. 2015. New hadrosauroid material from the Upper Cretaceous Majiacun Formation of Hubei Province, central China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 53(3):245-264

Trexler, D., 2001, Two Medicine Formation, Montana: geology and fauna: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, pp. 298–309.

Varricchio, D.J. (1995). "Taphonomy of Jack's Birthday Site, a diverse dinosaur bonebed from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 114 (2–4): 297–323.

Varricchio, D. J. 2001. Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaur (Theropoda) dinosaurs from Montana. pp. 42–57 in D. H. Tanke and K. Carpenter (eds.), Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Versluys, J. 1923. Der Schädel des Skelettes von Trachodon annectens im Senckenberg-Museum. Abhandlungen Der Senckenbergischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft 38:1–19.

Weishampel, D. B., and J. B. Weishampel. 1983. Annotated localities of ornithopod dinosaurs: implications to Mesozoic paleobiogeography. The Mosasaur 1:43-87

Weishampel, D. B., and J. R. Horner. 1990. Hadrosauridae. In D. B. Weishampel, H. Osmolska, and P. Dodson (eds.), The Dinosauria. University of California Press, Berkeley 534-561

Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp.

Woodward, H. N., E. A. Freedman Fowler, J. O. Farlow, J. R. Horner. 2015. Maiasaura, a model organism for extinct vertebrate population biology: a large sample statistical assessment of growth dynamics and survivorship. Paleobiology 41 (4): 503-527.

Woodward, H. N. (2019). Maiasaura (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) Tibia Osteohistology Reveals Non-Annual Cortical Vascular Rings in Young of the Year. Frontiers in Earth Science, 7, 50.

#Maiasaura peeblesorum#Maiasaura#Dinosaur#Hadrosaur#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#factfile#Saurolophine#Cretaceous#Mesozoic Monday#Palaeoblr#Dinosaurs#North America#Herbivore#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

358 notes

·

View notes

Text

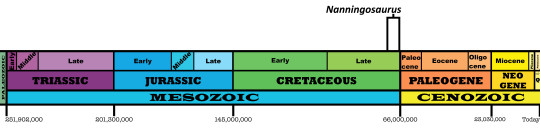

Nanningosaurus dashiensis

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Nanning City Reptile

First Described By: Mo et al., 2007

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Ornithischia, Genasauria, Neornithischia, Cerapoda, Ornithopoda, Iguanodontia, Dryomorpha, Ankylopollexia, Styracosterna, Hadrosauriformes, Hadrosauroidea, Hadrosauromorpha, Hadrosauridae, Euhadrosauria, Lambeosaurinae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Sometime in the Maastrichtian age of the Late Cretaceous, between 72 and 66 million years ago

Nanningosaurus is known from the Dashi Site in Guangxi, China

Physical Description: Nanningosaurus is, sadly, only known from a very incomplete and partial skeleton, which does include parts of the skull and jaws. Thus, it is difficult to say what it would have looked like beyond being a Hadrosaur. It seems most likely that it was a Lambeosaurine, or Hollow-Crested Hadrosaur, though of course we don’t know if it actually had a crest or not. As such, all we can know is that it would have been a fairly bulky animal, covered in scales, with a duck-like beak and potential display or communication structures on its head. It also may have had hooves, like other hadrosaurs, on its front feet. Because of course they did.

Diet: Being a hadrosaur, Nanningosaurus would have mainly fed upon soft, wet plants, such as those found around or in sources of water. It would have then used its thousands of teeth to mash it up into a paste, to make the leaves easier to swallow.

Behavior: Obviously, we don’t know a lot about the behavior of Nanningosaurus because, again, we don’t have a lot of fossils of it. As hadrosaurs, they would have been very social animals, living in large herds. It would have taken care of its young, potentially in communal nesting grounds with large mounds to hold the eggs in and rotting vegetation to keep the eggs warm. It probably would have had somewhat complex social displays, potentially using color and sound, in order to communicate with other members of the herd and to find mates. It also may have used this communication to warn the herd of predators, though no predators were found with Nanningosaurus.

Ecosystem: Nanningosaurus is not known from a very well studied fossil site - it doesn’t even have a formation name! It does seem to have been a muddy environment, indicating some sort of source of fresh water and probable frequent rains. Here, Nanningosaurus lived alongside the titanosaur Qingxiusaurus, which is also only known from limited remains.

Other: While the exact nature of Nanningosaurus is rather murky, it is a very important fossil discovery - it’s one of the most Southern Asian Hadrosaurs! As such, as we learn more about it, we will be able to piece together the evolutionary puzzle of this wonderful dinosaur group a little clearer.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Cruzado-Caballero, P., and J. E. Powell. 2017. Bonapartesaurus rionegrensis, a new hadrosaurine dinosaur from South America: implications for phylogenetic and biogeographic relations with North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 37(2):e1289381:1-16.

Mo, J., Z. Zhao, W. Wang and X. Xu. 2007. The first hadrosaurid dinosaur from southern China. Acta Geologica Sinica 81(4):550-554.

Mo, J.-Y., C.-L. Huang, Z.-R. Zhao, W. Wang, and X. Xu. 2008. A new titanosaur (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Guangxi, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 46(2):147-156.

Xu, S.-C., H.-L. You, J.-W. Wang, S.-Z. Wang, J. Yi and L. Jia. 2016. A new hadrosauroid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Tianzhen, Shanxi Province, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 54(1):67-78.

#Nanningosaurus dashiensis#Nanningosaurus#Dinosaur#Hadrosaur#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Cretaceous#Eurasia#Herbivore#Mesozoic Monday#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

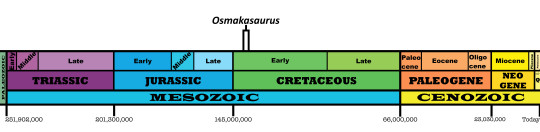

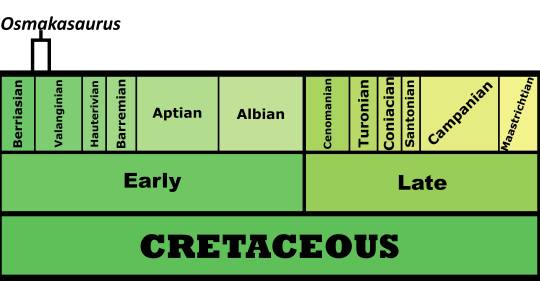

Osmakasaurus depressus

By Jack Wood

Etymology: Reptile from the Canyon

First Described By: McDonald, 2011

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Ornithischia, Genasauria, Neornithischia, Cerapoda, Ornithopoda, Iguanodontia, Dryomorpha, Ankylopollexia, Styracosterna

Status: Extinct

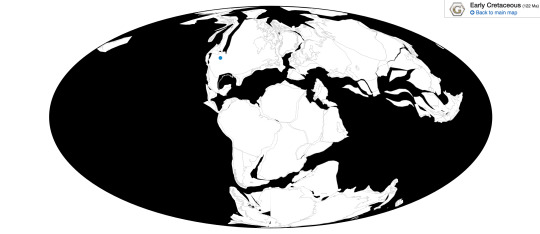

Time and Place: Between 140 and 137 million years ago, from the Berriasian to the Valanginian ages of the Early Cretaceous

Osmakasaurus is known from the Chilson member of the Lakota Formation in South Dakota

Physical Description: Osmakasaurus was an animal fairly like Camptosaurus, a bulky bipedal herbivore with short arms and thick legs. It probably ranged between 4 and 5 meters long, and compared to its close relatives it had a fairly narrow and weirdly-shaped hip, though of course very little else is known of it to determine how else it may have differed from its close relatives. Osmakasaurus would have been primarily scaly, though it may have had some residual tufts of feathers or a feather cape of some sort for display.

Diet: Osmakasaurus would have been a mid-level browser, feeding on bushes and low-lying tree branches, probably specializing on tough vegetation like its close relatives.

Behavior: Osmakasaurus probably wasn’t a herding sort of animal - dinosaurs in this group of Ornithopods tend to be more solitary than the earlier flocks of small bipedal friends and the later magnificent herds of the later hadrosaurs. Instead, Osmakasaurus would have been fairly solitary, moving around its environment and trying to stick to places of denser vegetation in order to stay hidden. It is possible that it formed family groups during the mating season - it almost decidedly took care of its young, so it is not unreasonable to suppose that mated pairs would care for the young during the season together, but that would probably be the extent of its social behavior after leaving the families. They would have been somewhat slow animals, given their size, but able to run when needed.

Ecosystem: The Chilson environment was a sandy floodplain, filled with winding rivers and greatly affected by seasonal ebbs and flows of water. As such it was mainly filled with plants able to deal with these changes - hardy conifers and seed ferns, though there were some leptosporangiate ferns as well. These rivers, though fickle, hosted a wide variety of animals in addition to Osmakasaurus. There were many types of fish, as well as mammals such as Bolodon, Passumys, Lakotalestes, and Infernolestes. Other dinosaurs mainly included other herbivores - an ankylosaur, Hoplitosaurus; some sort of large sauropod; and a more Iguanodon-like Ornithopod, Dakotodon.

Other: Osmakasaurus used to be a species of Camptosaurus, since the latter was a wastebasket taxon in which large, bipedal ornithopods that weren’t quite Iguanodon-like enough were dumped into. It was since separated out, but not much more has been said about it. It was close to being Iguanodon, but not quite, and so still was in the group of generic-Camptosaurus-esque things. It is only known from scattered remains.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Cifelli, R.L., Davis, B.M., and Sames, B. 2014. Earliest Cretaceous mammals from the western United States. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 59 (1): 31–52.

D'Emic, M. D., & J.R. Foster (2014) The oldest Cretaceous North American sauropod dinosaur. Historical Biology (advance online publication) DOI:10.1080/08912963.2014.976817

Gilmore, C.W., 1909. Osteology of the Jurassic reptile Camptosaurus, with a revision of the species of the genus, and description of two new species. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 36: 197-332.

McDonald, A.T., 2011. The taxonomy of species assigned to Camptosaurus (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda). Zootaxa 2783: 52-68.

Ruiz-Omeñaca, L. Piñuela, J. C. García-Ramos. 2012. New ornithopod remains from the Upper Jurassic of Asturias (North Spain). 10th Annual Meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Palaeontologists. ¡Fundamental! 20: 219 - 222.

Sames, B., Cifelli, R.L., and Schudack, M. 2010. The nonmarine Lower Cretaceous of the North American Western Interior foreland basin: new biostratigraphic results from ostracod correlations, and their implications for paleontology and geology of the basin—an overview. Earth-Science Reviews 101: 207–224.

#Osmakasaurus#Osmakasaurus depressus#Dinosaur#Ornithopod#Ankylopollexian#Palaeoblr#Cretaceous#North America#Herbivore#Mesozoic Monday#Dinosaurs#Prehistoric Life#Factfile#paleontology#prehistory#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jinzhousaurus yangi

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Reptile from Jinzhou

First Described By: Wang & Xu, 2001

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Ornithischia, Genasauria, Neornithischia, Cerapoda, Ornithopoda, Iguanodontia, Dryomorpha, Ankylopollexia, Styracosterna, Hadrosauriformes, Hadrosauroidea

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Jinzhousaurus lived about 124.4 million years ago, in the Aptian of the Early Cretaceous

Jinzhousaurus is known from the Dawangzhangzi Beds of the Yixian Formation

Physical Description: Jinzhousaurus was a Hadrosauroid, a type of dinosaur closely related to the duck-billed dinosaurs (Hadrosaurids) of the late Cretaceous - and a member of the group from which they evolved. This group experimented a lot with how they chewed and acquired food, mainly in order to deal with the rapidly changing environment of the Cretaceous Period. As the late Cretaceous turned into a very humid landscape, however, most of these forms died out, giving way to the Hadrosaurids to take over with their specialized-for-mushy-plant-food mouths. Jinzhousaurus was a fairly medium-sized dinosaur, reaching about 7 meters in length with a skull a half a meter long. It had very large nose holes and a wide back of the skull, with a small crest. It probably would have moved back and forth between walking on two legs versus four. It had three toes on each foot and five fingers on each hand, though only the first three fingers had claws - so it wasn’t really evolving the hoof-like front limbs seen in the Hadrosaurids proper. Its snout wasn’t a duckbill, but more like that of Iguanodon, with a rounded bulky beak - but different enough that it probably had a different feeding strategy than its cousin. Its back was stiffened extensively, making it rigid for balance and the tail mainly inflexible.

Diet: Jinzhousaurus primarily ate plants at the medium-browsing level - so mainly coniferous trees and the like.

Behavior: Jinzhousaurus probably didn’t live in groups but, rather, was mainly solitary. It would have spent most of its time wandering through its environment, grazing on plants alone, and remaining vigilant for danger. It also probably would have taken care of its young, though little else is known about its behavior.

By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Jinzhousaurus lived in the Yixian Formation, a highly diverse ecosystem showcasing the variety and evolution of birdie dinosaurs at the beginning of the Cretaceous period. This was a diverse coniferous forest in a temperate, seasonal climate. Very humid, it’s likely that Jinzhousaurus would have seen snow on a regular basis. There were notable dry seasons as well, leading to more tough vegetation for Jinzhousaurus to chew on. There were many flowering plants there too, along with ferns, horsetails, ginkgoes, cycads, seed ferns, and so many others - all good food for Jinzhousaurus. This was also a dense freshwater lake environment, with abundant minerals due to volcanic eruptions - leading to periodic environmental turnover.

Jinzhousaurus lived alongside many other kinds of dinosaurs, as this was an exceptionally diverse community. Here there was the ankylosaurid Liaoningosaurus, another ornithopod called Bolong, and an unnamed titanosaur in terms of other herbivores. There were many kinds of small fluffy dinosaurs - the Compsognathid Sinosauropteryx; the raptors Zhenyuanlong, Changyuraptor, Sinornithosaurus, and Tianyuraptor; the Troodontid Jianianhualong; the protobirds Jeholornis, Confuciusornis, and Zhongornis; the Anchiornithid Yixianosaurus; the Opposite Birds Dalingheornis and Shanweiniao; and the early nearly-true-birds Archaeorhynchus, Eogranivora, Yanornis, Hongshanornis, and Longicrusavis. Non-dinosaurs were of course also present - many types of fish, amphibians, and lizards; mammals such as Akidolestes, Sinobaatar, Sinodelphys, Chaoyangodens, and the famous Eomaia; Choristoderes like Hyphalosaurus and Monjurosuchus; and pterosaurs like Cathayopterus and Ningchengopterus. Essentially, a beautiful snapshot of the Early Cretaceous.

Other: Jinzhousaurus is sort of a mix between earlier ornithopods and the later hadrosaurs, so its classification was difficult to place for a while. But now it seems to be a basal member of the group that lead to the Hadrosaurids, rather than more close to Iguanodon proper.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Amiot, R., X. Wang, Z. Zhou, X. X. Wang, E. Buffetaut, C. Lécuyer, Z. Ding, F. Fluteau, T. Hibino, N. Kusuhashi, J. Mo, V. Suteethorn, Y. Y. Wang, X. Xu, F. Zhang. 2011. Oxygen isotopes of East Asian dinosaurs reveal exceptionally cold Early Cretaceous climates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (13): 5179 - 5183.

Barrett, P. M., R. J. Butler, W. Xiao-Lin, X. Xing. 2009. Cranial anatomy of the Iguanodontoid Ornithopod Jinzhousaurus yangi from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of China. Acta Paleontologica Polonica 54(1): 35-48.

McDonald, A. T., D. G. Wolfe, J. I. Kirkland. 2010. A new basal hadrosauroid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Turonian of New Mexico. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30(3): 799-812.

Meng, F.X.; Gao, S.; Liu, X.M. (2008). "U-Pb zircon geochronology and geochemistry of volcanic rocks of the Yixian Formation in the Lingyuan area, western Liaoning, China". Geological Bulletin of China. 27: 364–373.

Wang, X., & X. Xu. 2001. A new iguanodontid (Jinzhousaurus yangi gen. et sp. nov.) from the Yixian Formation of western Liaoning, China. Chinese Science Bulletin 46(19): 1669-1672.

Wang, Y., S. Zheng, X. Yang, W. Zhang, Q. Ni. 2006. The biodiversity and palaeoclimate of confier floras from the Early Cretaceous deposits in western Liaoning, northeast China. International Symposium on Cretaceous Major Geological Events and Earth System: 56A.

Zhou, Z. 2006. Evolutionary radiation of the Jehol Biota: chronological and ecological perspectives. Geological Journal 41: 377-393.

#Jinzhousaurus#Jinzhousaurus yangi#Dinosaur#Ornithopod#Hadrosauroid#Palaeoblr#Cretaceous#Jehol Biota#Eurasia#Herbivore#Terrestrial Tuesday#Factfile#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

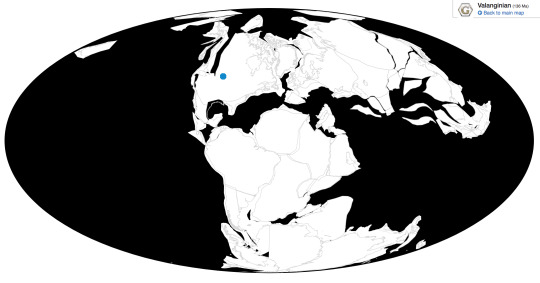

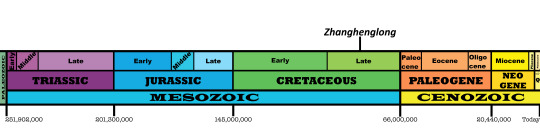

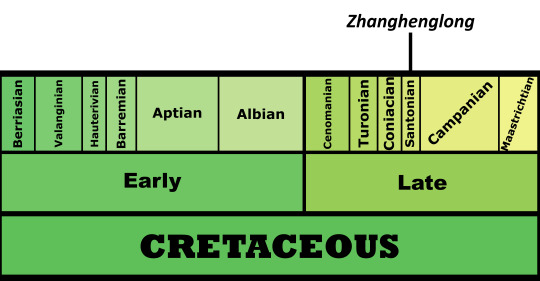

Zhanghenglong yangchengensis

By Jack Wood

Etymology: Dragon from Zhang Heng

First Described By: Xing et al., 2014

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Ornithischia, Genasauria, Neornithischia, Cerapoda, Ornithopoda, Iguanodontia, Dryomorpha, Ankylopollexia, Styracosterna, Hadrosauriformes, Hadrosauroidea

Status: Extinct

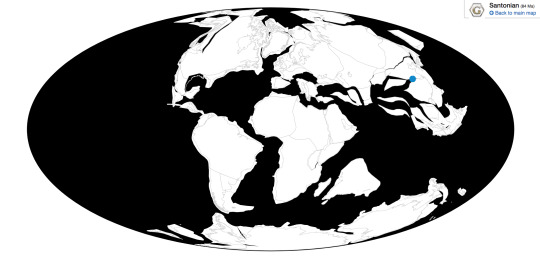

Time and Place: 85 million years ago, in the Santonian age of the Late Cretaceous

Zhanghenglong is known from the Majiacun Formation in Xixia, Henan, China