#susan gubar

Text

Reading the writing of women from Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë to Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf, and Sylvia Plath, we were surprised by the coherence of theme and imagery that we encountered in the works of writers who were often geographically, historically, and psychologically distant from each other. Indeed, even when we studied women's achievements in radically different genres, we found what began to seem a distinctively female literary tradition, a tradition that had been approached and appreciated by many women readers and writers but which no one had yet defined in its entirety. Images of enclosure and escape, fantasies in which maddened doubles functioned as asocial surrogates for docile selves, metaphors of physical discomfort manifested in frozen landscapes and fiery interiors—such patterns recurred throughout this tradition, along with obsessive depictions of diseases like anorexia, agoraphobia, and claustrophobia.

The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar

#the madwoman in the attic#sandra m. gilbert#susan gubar#quote#literature#dark things#feminist literature#dark academia#aesthetic#jane austen#Charlotte Brontë#emily dickinson#virginia woolf#sylvia plath#on writing

716 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Looking Oppositely: Emily Brontë’s Bible of Hell’, in The Madwoman in the Attic, Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar

#trying again#wuthering heights#emily bronte#the madwoman in the attic#sandra m. gilbert#susan gubar

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 'killing' of oneself into an art object -- the pruning and preening, the mirror madness

- from The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination, Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

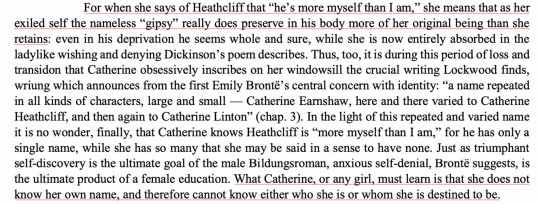

August Wrap Up

Well, this month has sucked. And that’s all I have to say about that.

Books Read: 15

But at least I read a lot. My favorite by far was Babel, and I really don’t have a least favorite. There was nothing under 3.5 stars. But seriously, go check out Babel, it’s freaking amazing. Books marked with ® are rereads.

Belinda by Maria Edgeworth - 5 stars

Blood, Bread, and Poetry: Selected Prose, 1979-1985 by Adrienne Rich - 4 stars

New Woman Fiction: Women Writing First-Wave Feminism by Ann Heilmann - 4 stars

Hard Times by Charles Dickens - 4.5 stars ®

Lady Windermere’s Fan by Oscar Wilde - 4 stars

The Clever Woman of the Family by Charlotte Mary Yonge - 4 stars

The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar - 4 stars

The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde - 4 stars

Victorian Women’s Fiction: Marriage, Freedom, and the Individual by Shirley Foster - 4 stars

The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer: Ideology as Style in the Works of Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley, and Jane Austen by Mary Poovey - 3.5 stars

Kim by Rudyard Kipling - 3 stars

Babel, or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution by R. F. Kuang - 5 stars

Marcella by Mary Ward - 3.5 stars

Mrs. Warren’s Profession by George Bernard Shaw - 4 stars ®

The ‘Improper’ Feminine: The Women’s Sensation Novel and the New Woman Writing by Lyn Pykett - 4 stars

On Tumblr:

There’s some stuff here; mostly tags, but I did participate in the first half or so of the 1K Pages Readathon.

1K Pages Readathon August 2022

July Wrap Up

Book Quotes: Babel by R. F. Kuang

Tagged: Sequel Stack Challenge

Tagged: Pink Book Stack

Tagged: Yellow Book Stack

Reblogged: Queer Fantasy Recommendations

On the Blog:

Hey, look, there’s something here! What a miracle!

Book Review: Babel: An Arcane History by R. F. Kuang

On YouTube:

And there’s a nice selection here, as usual.

My INSANE August TBR

July Wrap Up - 8 Books for Jane Austen July and Exams!

A Bookish Birthday Haul

Underrated Victorian Recommendations #3

Currently Reading 8/15/22

GarbAugust Trashy Book Tag

#booklr#august wrap up#book photography#monthly wrap up#books#wrap up#the madwoman in the attic#sandra gilbert#susan gubar#new woman fiction#ann heilmann#the clever woman of the family#charlotte mary yonge#blood bread and poetry#adrienne rich#marcella#mary augusta ward#belinda#maria edgeworth#oscar wilde#the importance of being earnest#hard times#charles dickens#kim#rudyard kipling

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

I enjoyed Ash Del Greco’s Paglian disdain for contemporary gender pieties. Which other authors have influenced your views on gender?

Thank you! Wait until you see her whole journey: everything just hinted at in this chapter will be elaborated in the next few, including "the death and resurrection of Ari Alterhaus."

On a subject like this, I tend to write from life, not books, or, if from books, then from the sense of life arising from literature. Books that have influenced my thinking on the subject are mostly those that have attempted to synthesize the literary corpus.

After Sexual Personae, with its visionary conflict between male artifice and female nature, I read in college Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar's Madwoman in the Attic, the most persuasive statement of the second-wave feminist position in its examination of middle-class woman's primal self-splitting rage at their sequestration in the domestic. Then I read in graduate school Nancy Armstrong's Desire and Domestic Fiction, which flipped that argument on its head to reveal female domesticity not as a form of oppression but as a form of englobalizing social power that still hangs over us today, to be revised into the techno-authority of the sexless expert class, including literary modernists, as argued in this book by Armstrong's advisee and my advisor.

These are books about Anglophone white middle-class culture, but that's the culture I was born into—sort of, halfway—and the one I tend to write about. I understand this culture, per Armstrong and Paglia in their different ways, to be an essentially female culture. As I've never run away to the whale ship or the war to evade it, I've never done much with masculinity except to read Melville, Conrad, Hemingway, and McCarthy—and Thoreau.

For my broadest sense of modern gender, see my essay on Austen's Sense and Sensibility, which novel Jacob Morrow tells Ash del Greco to read. Two other novels that I always recommend, ones that circumscribe Anglophone white middle-class culture, are Barnes's Nightwood and Morrison's Paradise. The latter concludes with the theophany of a black madonna that cancels, elevates, and preserves perhaps my earliest cosmo-cultural experiences of gender in the mariolatrous Catholic Church.

0 notes

Text

My new favorite way to pass the time is to read classic literary criticism texts and then use them to analyze films. So far I’ve paired:

"Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence" by Adrienne Rich with The Birds (1963).

"A Cyborg Manifesto" by Donna Haraway and Titane (2021). *Got the idea for this from an essay on hyperallergenic.com.

The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar and Little Women (2019).

Next I’m thinking of pairing The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry by Harold Bloom with Scream (1996). Any film/literary criticism nerds out there with other recommended pairings, please let me know your suggestions!

#my own nerdy film club for one#adrienne rich#donna haraway#sandra gilbert and susan gubar#harold bloom#compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence#a cyborg manifesto#the madwoman in the attic#the anxiety of influence#the anxiety of authorship#just film nerd things#english majors in recovery

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Angel in the House

"Man must be pleased; but him to please

Is woman's pleasure; down the gulf

Of his condoled necessities

She casts her best, she flings herself."

In 1854, the English poet Coventry Kersey Dighton Patmore published his poem "The Angel in the House," which depicted his first wife, Emily. Much of his poetry focused on his idealized marriage life, and after Emily's death, a wave of grief haunted the rest of Patmore's work.

The cultural significance of this work is immense. Gender, as a social construct, has been defined and redefined numerous times. Attributes of femininity today differ significantly from the past. Nevertheless, certain ideas and motifs from past centuries remain familiar to us: women occupying a place in society solely determined by men.

"The Angel in the House" became a crucial motif in British and American literature during the 19th century. This term represents a woman imprisoned in the domestic sphere of social life, devoid of economic freedom and any work beyond serving her husband. Thus, economic independence for women was nearly impossible except for the lower economic class where women had to work to make a living. The Cult of Domesticity advocated four cardinal virtues—piety, purity, domesticity, and submissiveness—which defined femininity so distinctly that deviation was impossible. Victorian women either had to be passive angels or active monsters. It is also worth noting that this concept is highly race and class-based, meaning it mainly applies to upper-class white women.

Many other similar motifs appear in literary history like “the mad woman in the attic" in Jane Eyre which later contributed to the feminist approach to literature as a theory holding the same name. Instead of discussing every term and explain what they mean, I want to emphasize the importance of gender as an analytical category in literary studies. The absence or scarcity of female authors in many literary eras is perfectly described by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar as “the anxiety of authorship." Just as Ms. George Eliot crawled during daytime with her doors locked like the hysteric female protagonist of Gilman’s Yellow Wallpaper, European and American women were so repressed by the family dynamics of their time that even the most privileged ones were hesitant to write or publish their writings. They knew they would not be recognized, and they feared the consequences of being more than they were allowed to.

In short, literature written by women is itself feminist liberation—a powerful urge that led women all around the world to fight for each other's existence. This aspect must be taken into consideration as a part of the historical background when examining the literary works of the past centuries. As Andrea Dworkin puts it more explicitly, "No woman could be Nietzsche or Rimbaud without ending up in a whorehouse or lobotomized."

William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience

p.s. If you enjoyed reading this, I will also be posting short articles on Medium. I would appreciate the support *-*

#feminism#literature#study#studyblr#poetry#literary studies#study notes#art#woman#gender studies#gender#struggle#analysis#victorian#19th century#victorian literature

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Madwoman in the Attic, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

On bed rotting, a day of rest, and an anniversary.

I can't remember the last time I voluntarily spent the day in bed. My grandmother, born in 1906 spoke of 'taking to bed' - something the energetic but sickly child I was could not understand unless one was ill. As I grew older, weekends became productive time - to study, do homework, write papers, maintain my living space, run errands. The cup of life ran over and drowned the calendar. No rest, or precious little of it even as my body began to fail under a diagnosis of fibromyalgia in 2007. I'd had viral meningitis in 2004, and my immune system never turned off.

Then there came the time when all I could do was rest, but it was miserable instead of restorative. Sickness, growing debility that I tried to deny and rationalize and bring to a doctor. Then hospitalization, tests and scans, diagnosis, preparation, and Stage 4a aggressive treatment. I came home and would sleep until I had to wake up and take Zofran, or in the really bad cases Ativan, or Clonazipine in order not to vomit myself into dehydration. After surgery, nothing but bed. Unable to lift anything heavier than a gallon of milk from November to April.

Today is second Monday in November, the anniversary of my big surgery, the removal of six feet of colon and intestines followed by a resection that literally gave me a new asshole. They removed my uterus and ovaries where the cancer had begun to spread. They re-sectioned my left ureter and bladder because the cancer was spreading there, too. They placed a uretal stent while I healed. I had an ileostomy done so my stitched-together innards could close. Finally, they removed 22 lymph nodes of which seven were found to be precancerous or cancerous. They say you forget the pain, and to an extent that is true. You forget the physical sensation, but you never forget waking up screaming, passing out, waking up again, and begging to die.

I know what a ten on the pain scale is like now. It's been revised up and up. Just when I thought I knew ten, I found out differently. My torso is marked by scars that look as if they were drawn in black Sharpie. I'm in remission, and far from wanting to be the busy, productive person I used to be, I find that I don't want to be anything. With my mother's death in the spring, the burden of daughterhood to a cluster b disordered woman, of shepherding her through dementia as I shepherded myself through cancer was lifted. I grieved the mother I wished for and she could sometimes be, but I was relieved that this stranger who came to wear my mother's body was finally gone. She could rest, and now so can I now that her energy has returned to the universe.

I am still working, but I am selfish now. My weekends are just for me. Despite being in remission, I don't know how many more I will have. That makes them precious. I cook, make jewelry, and 'watch telly' as Gran used to say. It was while I was rotting in bed on Sunday - my pre-Recession habit revived - that I came upon this interview in the Washington Post. Susan Gubar was a formative writer of my teen years, a time when the ERA failed because the male-dominated worldview (with a pushback spearheaded by 'traditional' women) didn't think we needed more rights than we already had, if anything they thought we had too many.

The Madwoman in the Attic, For Adult Users Only: The Dilemma of Violent Pornography, No Man's Land: The Place of the Woman Writer in the Twentieth Century : The War of the Words all ended up in my mother's shelves - she laid claim to my library when I moved out. With her death, I now get them back, plus more. My ten boxes of books donated in the first spate of Swedish Death Cleaning are nothing compared to my mother's hoard of books over her 80+ years of life. On top of that there are the books that she borrowed from me, that somehow also became hers.

Susan Gubar is a cancer patient in remission, and I have downloaded her two books on cancer and survivorship. Memoir of a Debulked Woman: Enduring Ovarian Cancer, and Reading and Writing Cancer: How Words Heal. I plan to rot in bed this pre-Thanksgiving weekend, and read. Also of note, her recent book Still Mad: American Women Writers and the Feminist Imagination. I'm delighted to find her all over again, a writer whose 1979 work spoke to me as much as Virginia Woolf's 'A Room of One's Own.'

Hey. Mom had my copy of that, too, dangit.

Perhaps I can get my library back. A snapshot of myself circa 1991. I know she borrowed my Bell Hooks and Audre Lorde. Angela Davis was someone Mom knew somehow and bought her books on principle. I read a lot of Second and Third Wave feminism, queer theory, psychology, sci-fi, fantasy, and comic books. My first copy of 'Our Bodies: Ourselves' - Mom had to buy that one for me, the bookstore owner refused to sell it to me despite my being female I was not a woman. My old D&D guides.

Perhaps my remission Sundays need to be spent rotting in bed, rediscovering the voracious reader I was all those years, before the busy-ness of life nibbled my time away.

It's a resolution, voted, and carried.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

re. your post about nonfiction, do you have any nonfiction books that you would recommend to people who haven't read any ever?

these are some of the ones i've read that i either loved or just ones that i think offer a bit to the conversation. if anyone has more recs for me, please send some <3

know my name, chanel miller (10/10)

crying in h mart, michelle zauner

i'm glad my mom died, jennette mccurdy

everything i know about love, dolly alderton

trainwreck: the women we love to hate, mock, and fear...and why, sady doyle

dead blondes and bad mothers: monstrosity, patriarchy, and the fear of female power, sady doyle

trick mirror: reflections on self-delusion, jia tolentino (there are people who hate this one, and then there are communications students. i'm a communications student)

bad feminist: essays, roxane gay (really great introductory book to nonfiction/feminist theory)

all about love: new visions, bell hooks

call them by their true names: american crises, rebecca solnit

empireland: how imperialism has shaped modern britain, sathnam sanghera (a little tedious for me, but an important read nevertheless)

the madwoman in the attic: the woman writer and the nineteenth-century literary imagination, sandra m. gilbert & susan gubar

mediocre: the dangerous legacy of white male power, ijeoma oluo (READ THIS!!!!)

men who hate women: from incels to pickup artists, the truth about extreme misogyny and how it affects us all, laura bates

a curious history of sex, kate lister (served absolute cunt)

#answered#Anonymous#books#i didn't like all of these but i do think everyone should at least give these a try

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Succession Tom/Logan Hybrid Senseability and Transformation Part 1: Denial of Death

Part 2

Masterlist

Part Two

(The references are spilt in peices because there's so many) No Succession Ep References

The Heart's Forest. A Study of Shakespeare's Pastoral Plays by David Young/Violence and the Sacred by René Girard/In a Disused Graveyard by Robert Frost/ Violence and the Sacred by René Girard/ Violence and the Sacred by René Girard/Dead Hands by Katherine Rowe/

Knight Moves by Suzanne Vega/Dead Hands by Katherine Rowe/Violence and the Sacred by René Girard / Violence and the Sacred by René Girard/ Who Are You, Really? by Mikky Ekko/The Old Oak Tree's Last Dream by Hans Christian Andersen/The Old Oak Tree's Last Dream by Hans Christian Andersen/

/Dead Hands by Katherine Rowe/Mean Girls 2004/Gothic Forms of Feminine Fiction by Susanne Becker/The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar/My Love My Life by Abba/The Heart's Forest. A Study of Shakespeare's Pastoral Plays by David Young/

/Violence and the Sacred by René Girard/No Magic, No Metaphor Fredric Jameson on ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude/Dead Hands by Katherine Rowe/Who Are You, Really? by Mikky Ekko/Dead Hands by Katherine Rowe/Mother and Child by Louise Glück/The Heart's Forest. A Study of Shakespeare's Pastoral Plays by David Young

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Both in life and in art, we saw, the artists we studied were literally and figuratively confined. Enclosed in the architecture of an overwhelmingly male-dominated society, these literary women were also, inevitably, trapped in the specifically literary constructs of what Gertrude Stein was to call "patriarchal poetry." For not only did a nineteenth-century woman writer have to inhabit ancestral mansions (or cottages) owned and built by men, she was also constricted and restricted by the Palaces of Art and Houses of Fiction male writers authored. We decided, therefore, that the striking coherence we noticed in literature by women could be explained by a common, female impulse to struggle free from social and literary confinement through strategic redefinitions of self, art, and society.

The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar

#the madwoman in the attic#sandra m. gilbert#susan gubar#quote#literature#dark academia#dark things#feminist literature#feminism#feminist art#misogyny#gertrude stein#on writing#patriarchal poetry

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heathcliff’s presence gives the girl a fullness of being that goes beyond power in household politics, because as Catherine’s whip he is an alternative self or double for her, a complimentary addition to her being who fleshes out all her lacks the way a bandage might staunch a wound. Thus in her union with him she becomes, like Manfred in his union with his sister Astarte, a perfect androgyne.

‘Looking Oppositely: Emily Brontë’s Bible of Hell’, in The Madwoman in the Attic, Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

@quarkfcker asked me to compile a list of my favorite works of critical theory - here you go! if anyone is interested in the titles i’ll try to find links later (i’m currently stuck in bed with an endometriosis flare up and posting this from my phone lol)

Susan Sontag - Illness as Metaphor (deals critically with attaching morality to health; in one of my favorite sections Sontag discusses the vocabulary around getting better - “fighting” cancer, “beating” a disease, etc)

Cassie Pedersen - “Encountering Trauma ‘Too Soon’ and ‘Too Late’: Caruth, Laplanche, and the Freudian Nachträglichkeit” in Topography of Trauma: Fissures, Disruptions, and Transfigurations (Deconstruction of Freud’s notion that trauma is time-based and only recurrent after the action)

Judith Butler - Gender Trouble (one of my favs forever)

Eve Sedgewick - “Epistemology of the Closet” and “Between Men” (Between Men especially)

I would try very hard to muscle through a little bit of Jacques Lacan just to understand the concept of the Other. It’s not gonna be easy or fun though.

Sigmund Freud - “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality” (I know I know boo we hate your pussy Sigmund but I think it’s important to read Freud so you can have a leg to stand on when you’re arguing against him. He also wasn’t wrong all the time, and a lot of his theory gets picked up by feminist scholars, especially these essays. I think often it’s a matter of needing someone who wasn’t a misogynist to contextualize his work.)

Edward Saïd - Orientalism

Frantz Fanon - Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth (both are postcolonialist theory. Fanon is a huge name in poco that you should know.)

Louis Althusser - “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” (don’t fuck with the working class etc. This one gives you cool and smart-sounding words like The Superstructure.)

Rosi Braidotti - The Posthuman (Good way to dip your toes into the never ending pool of posthumanism.)

Deleuze and Guattari are interesting but I would watch some Youtube videos explaining their work rather than just reading them because it is not brain friendly to me. Check out “The Body without Organs” and “Rhizomes” specifically. However be mindful that reading firsthand is always a good start to understanding, and videos should be supplemental.

Walter Pater and Matthew Arnold are dear to me because I’m a Romantic/Victorian scholar but if you’re not then you probably won’t get as much out of them. I still think Arnold’s Stones of Venice and Pater’s Studies in the History of the Renaissance are good foundational reads to understand a lot of the basis of art and criticism today.

Sigmund Freud (again) - “The Uncanny”

Zora Neale Hurston is incredible and a good name to keep in your pocket. She was a Black anthropologist and a lot of her work is deeply astoundingly moving.

FUCK SIMONE DE BEAUVOIR

Roland Barthes - “Death of the Author” (this is required reading for everyone.)

Peruse a good bit of Foucault.

Jacques Derrida - “Spectres of Marx,” “Hauntology,” etc. (I LOVE DERRIDA!!!! I’d definitely read an introduction to deconstruction first.)

Toni Morrison - “Unspeakable Things Unspoken: The Afro-American Presence in American Literature” (you should already be reading Toni Morrison.)

Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar - The Madwoman in the Attic (Loove this one. Feminist reading of Victorian literature.)

Hélène Cixous is a good name to know and have in your filing cabinet, as is Julia Kristeva.

Any and all bell hooks you can find, especially “Postmodern Blackness” and Feminism is for Everyone. If you’re planning on being anywhere near the sphere of education, check out Teaching to Transgress.

Jack Halberstam - “Female Masculinity” (Butchness and how it differs from male masculinity)

Rob Nixon - “Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor”

E. Ann Kaplan - Trauma Culture: The Politics of Terror and Loss in Media and Literature (connection between the individual and cultural trauma)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Cultural Capital” emerged when literature departments were in the throes of the “canon wars.” These were curricular skirmishes fought between progressives, who wanted to “open the canon” to work by authors from marginalized groups, and conservatives, who feared that identity politics was being elevated over aesthetic value. Guillory’s insight was that these differences of opinion were, at root, almost secondary, less structural than cosmetic. Progressives and conservatives alike were participating in a system whose main function was the production of what the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called “cultural capital”: the distinctive styles of speaking, writing, and reading that marked degree holders as members of the educated class. To be the kind of person who could translate the Iliad in 1880, or do a close reading of a poem in 1950, or “queer” a work in 2010, was to be manifestly the product of a university, and to reap economic and social rewards because of it. Any claim about what should be taught had to be seen in light of the academy’s institutional role. Whether one spoke of the Western canon (as Bloom did), the feminist canon (as Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar did), or the African American canon (as Henry Louis Gates did), the idea of a literary canon was a form of cultural capital.

At the same time, the shifting economic order has made the cultural capital of literature less valuable in market terms. The professoriat has struggled to demonstrate a connection between the skills cultivated in literature classrooms and those required by the professional-managerial jobs that many students are destined for. (Writing the previous sentence, I was startled to recall, for the first time in years, the lyrics of the song “What Do You Do with a B.A. in English?,” from the Broadway musical “Avenue Q”: “Four years of college and plenty of knowledge / Have earned me this useless degree. / I can’t pay the bills yet, / ’Cause I have no skills yet.”) As a result, literary study has contracted. State legislatures have slashed funding for the arts and humanities; administrators have merged or shut down departments; and the number of tenure-track jobs for graduate students has dwindled. Since the nineteen-sixties, the proportion of students pursuing degrees in English has dropped by more than half.

x

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

House Of Leaves Reading Part 1

So, originally my plan was to do updates every 100 pages or so. Buuut, this book is so odd, and of course nothing can be easy. So far I have read the introduction, the first five chapters, and Appendix II-D and Appendix II-E. Also worth noting I am reading both The Navidson Record and the footnotes together. Does that probably make comprehension harder, yeah, but it also feels like the more authentic experience to me. I'm not completely sure what these posts are going to be, or what they should be. First impressions, reading notes, and maybe a little bit of review. Mostly, it's just for me, so I can get my thoughts out without constantly spewing nonsense at my irl friends. Obviously spoilers ahead for the sections I have read, and I would appreciate no one adding spoilers past this point in the book.

The book is full of unreliable narrators, and it is hard to get a feel for what the actual story is trying to "tell" you. If it is at all. I think with a story this large and this meta, in the end it really is going to be about what a reader takes away from it, more than what the author intended. But also, I want to analyze the author's brain, how do you make something this overly convoluted. I will definitely be searching out more information on the author later, just for my own curiosity, but have waited to do so to avoid potential spoilers. What I think is perhaps most interesting about the unreliable narrators is the potential for hidden identities. We only see The Navidson Record through Zampanó, who we see through Johnny's collection of his notes, and we only see those through the Editors. The audience cannot be certain that everything is accurate. Johnny admits to changing a detail about the water heater/ heater on page 16. We also see in the appendices that details about Johnny's parents have been obscured. That names have been changed, has Johnny's name been changed? His mother's? His father's last name is omitted, perhaps meant to indicate that Truant is not Johnny's real last name either.

There's a part in Appendix II-E, The Three Attic Whalestoe Institute Letters, (also, the name attic being include and it being a mental institute, is this perhaps a refrence to Jane Eyre, and the idea of "The Madwoman in the Attic", written by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar? Unclear, perhaps accidental coincidence.) where Johnny's mother says, "Practicing my smile in a mirror the way I did when I was a child" (page 615) which stuck out to me because Karen is described as, "composing that smile in front of a blue plastic handled mirror." (page 58) but of course Karen has two children, and Johnny grew up as an only child, so they can't be the same person, right? If I find out Daisy dies though, I'm coming back to this theory. But of course, Johnny also tells us there is no record of the Navidson Record.

There's just so many layers, and I am enjoying that. But I think that if someone tried to find a "one true answer" to this book, they would lose their mind and likely be disappointed.

2 notes

·

View notes