#literary studies

Text

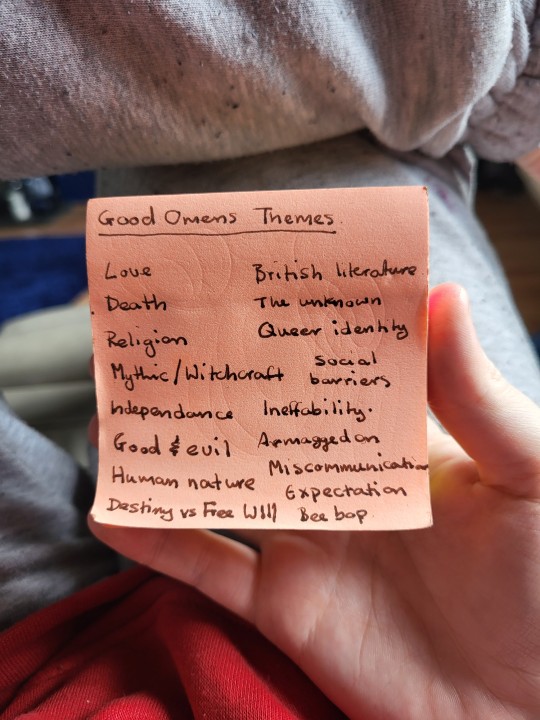

Doing some foreword thinking

My college art project next year will be based on a story and of course Good Omens is my go-to. This is my list of themes in the story (book and show)

Are there any more that I've missed? Or any input/ideas I can work with next year?

#thank you in advance#<3#good omens#crowley#aziraphale#ineffable husbands#david tennant#michael sheen#good omens 2#neil gaiman#college art#art#artwork#art study#literary studies#english literature

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

#school#notes#study#student#study aesthetic#studying#studyblr#high school#study notes#studyspo#dark academia#english#aesthetic#literature#study hard#academia#productivity#light academia#literary studies#cottage academia#romantic academia#chaotic academia#mind map#picture#collage#vibe#mood#august

561 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've seen a couple of folks talking about wanting to learn more about the history of BL, and this is the most comprehensive, up-to-date collection of English-language academic material on the topic I know of. It's maintained by BL scholar Sam Aburime. The website linked above is mostly write-ups with sources cited but a good starting point. If you'd rather dig right into the academic sources, they also keep a spreadsheet with an overview of all the sources cited on the webpage here:

Want to know more about how the BL genre started out? Want to know about the evolution of the genre name from the 1970's tanbi to today's BL? Want to learn about how BL traditions diverged in different cultures that got onto the train of the genre, and what they still share? The genre's place in the history of manga overall? What definitions academics currently use to talk about it? Something else? Chances are there's something for you in there. Go, read, learn!

#academia#bl history#boys love#manga studies#literary studies#queer studies#bl genre#bl meta#bl fandom#fandom studies#(sorta)#my nonsense#resource#reference

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Matthew Wynn Sivils, “Gothic Landscapes of the South” from The Palgrave Handbook of the Southern Gothic

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

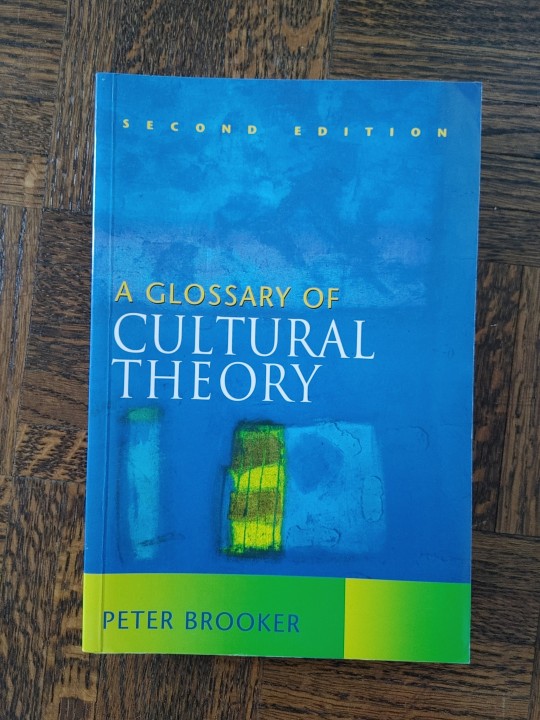

"(...) attempts to find general laws on literature have always failed."

"Most of these 'laws' (...) could not tell us anything really significant about the processes of literature."

"(...) no work of art can be wholly 'unique' since it then would be completely incomprehensible."

Theory of Literature, René Wellek and Austin Warren, 1948

#the only writing advice you need is: read#writers and poets#writers on tumblr#writeblr#ivatalks#poetry#writers on writing#on writing#about writing#literature#theory of literature#contemporary literature#classic literature#literary analysis#literary studies#studyblr#dark academia#study#theory#reading#writing advice#tumblr writers#how to write#writing tip

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

you've heard of cottagecore, you've heard of goblincore, but have you heard of cambridgecore

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Telling names, what are telling names you may ask?

Well, they hint at certain character traits (implicit) and are a type of authorial explicit characterisation.

For example:

Odo (latin: 'odo' Means 'I give shape' or 'I create') which is a telling name because as we know, he is a changeling

DATA (I don't have to explain Data, do I?)

Scotty (Scottish heritage)

#star trek#odo#ds9#Data#Scotty#tos#tng#literary studies#telling names#i am going insane please help me#my exam is in a few hours

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"People don't help much."

He wanted to explain how people were never quite what you thought they were.

- Lord of the Flies, Sir William Golding

#lord of the flies#sir william golding#william golding#literary quotations#literary quotes#literature#literature quotes#book quotations#book quotes#literature study notes#literary criticism#book quote#quotes#novel quotes#novel#novels#reading#books#book quotation#literary studies

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conventionally, escape, when used of "escape literature," implies a general evasion of responsibilities on the part of the reader who should, after all, spend his time on "serious literature." This is a pernicious dichotomy that derives from two misconceptions: first, that "seriousness" is better than "escape"; second, that escape is an indiscriminate rejection of order. Both these misconceptions owe something to the Protestant work ethic.

Escape literature includes adventure stories, detective stories, tales of fantasy, pornography, westerns, science fiction, and, when read for pleasure by adults, fairy tales.

Escape literature, according to the conventional wisdom, "aims at no higher purpose than amusement." But in the notions of "higher purpose" and of adults reading in a genre "beneath" them, we see that even today we maintain vestiges of the old prescriptive criticism: some kinds of literature are inherently better than other kinds. However, whatever virtues this position may have, it does not help us address questions of the uses of the fantastic.

The escape offered by these popular genres comes from their ability to exchange the confining ground rules of the extra-textual world not for chaos but for a diametrically opposed set of ground rules that define fantastic worlds. In so doing, authors create for us such works as The Odyssey, Oedipus, and Metamorphoses, to name just one each of "adventure stories, detective stories, tales of fantasy." These are not "beneath" anyone, and their escape is just as potent, and derives from precisely the same reconfiguration of ground rules, as To Hell and Back, And Then There Were None, and Pinocchio, respectively. The theme of a work may seem trivial, its characters uninteresting, its conflicts irrelevant, but if it offers escape, it is in that regard structurally akin to some of the world's great literature.

Escape in literature is a fantastic reversal, and therefore not a surrender to chaos. In its mundane uses, escape may be defined as "emerge from restraint; break loose from confinement." In the United States, the only country that calls its prisons penitentiaries, escape surely must imply a delinquent evasion of responsibilities. Since prison is an inherently displeasing environment with onerous ground rules, escape comes to mean any change, escape to anywhere. But escape from the prison of the mind is not so easily had. If the restraint is grounded in one's perceptions of oneself or of the nature of the world, mere change is not enough: one needs a compensating change, a diametric reversal. If boredom is the sign of the mind's one-track fixity, then its opposite, excitement, is what we need. Alice descends into Wonderland, not into Morris' Nowhere or Voltaire's garden. Escape, then, is neither inherently frivolous nor inherently unrestrained; we need feel no guilt in reading escape literature. In the literature of the fantastic, escape is the means of exploration of an unknown land, a land which is the underside of the mind of man.

—Eric S. Rabkin, The Fantastic in Literature, 1976

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

To shed some light on the topic of "Crime and punishment doesn't make any sense, I didn't understand it, therefore it's a bad book", I've decided to point out some topics of the novel. (Because certain people called me a pretentious fuck and became aggressive when I tried explaining that the book isn't badly written, but their tastes are on other lands. I have two russian friends, one of them hates this book because he was forced to read it in school at a young age, not because it was bad!!!! The second one told me they enjoyed it, and it was kinda good).

The actual topics behind the plot are definitely not murder or the criminal desire, but the torment and guilt that affect the murderer. We discover that after the murder (crime part of the title), the torment follows shortly (the punishment part of the title, lol). It's extremely visible, we can say hidden in plain sight even, that for Raskolnikov, the guilt in itself is the punishment, and he deeply desires to liberate himself from it. He achieves this by going back and forth between a dreamlike state and reality while acting as though he has gone insane. Because there is so much more going on in the novel, we frequently become disconnected from him, which makes us more curious about what will ultimately happen to our tormented hero.

This is a fragment from my review, and now, I get why this book can be very unappealing to readers, the amount of characters, the names, the relations between each of them, the PLOTLINES (because there are many). I must admit that I personally felt completely disoriented (at times). The perspective contributed to the confusion without a doubt. The narration is not first person, but a rather weirdly put third person with a focus on Raskolnikov (our main character). And to top this, the novel is clownish at times! It's memeable, Tumblr worthy. Yes, it's tough to get through if you don't have any support (friends that likes it and help you understand the plot when you get lost) or desire to read it.

I am not stating this is a book for everyone or that if you read it, you must like it. I'm simply saying it has a specific tone and aesthetic that you have to be in yourself at the right time in order to comprehend. I read this book for months, when I was alone, abroad, studying, and yet, I kept returning to it. Maybe I wanted to please my beloved, maybe i wanted to show myself I can and I will read it. I still don't know, but I know I read it, and I liked it. And I won't stand people telling me it's a bad book because they don't understand it. You just don't like it, and this doesn't make the book bad.

Thank for coming to my Ted talk

#yes i will never stop#i have to make my point#this is the continuation of the story where a person called me pretentious for pointing out the novel is not inherently bad#and maybe i am a pretentious fuck#after all I'm a lit student#and Dostoievsky isn’t my first rodeo#dark academia#literary analysis#literary studies#crime and punishment#dostoievsky

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The semester is coming to an end. It has been horrible :D. I’m taking a break from uni for the next couple of semesters :))

#light acamedia#study motivation#studyblr#studying#studyspo#university#dark academia#dark aesthetic#art history#bookshelf#light academism#dark academism#college#art historian#literary studies#literature

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Angel in the House

"Man must be pleased; but him to please

Is woman's pleasure; down the gulf

Of his condoled necessities

She casts her best, she flings herself."

In 1854, the English poet Coventry Kersey Dighton Patmore published his poem "The Angel in the House," which depicted his first wife, Emily. Much of his poetry focused on his idealized marriage life, and after Emily's death, a wave of grief haunted the rest of Patmore's work.

The cultural significance of this work is immense. Gender, as a social construct, has been defined and redefined numerous times. Attributes of femininity today differ significantly from the past. Nevertheless, certain ideas and motifs from past centuries remain familiar to us: women occupying a place in society solely determined by men.

"The Angel in the House" became a crucial motif in British and American literature during the 19th century. This term represents a woman imprisoned in the domestic sphere of social life, devoid of economic freedom and any work beyond serving her husband. Thus, economic independence for women was nearly impossible except for the lower economic class where women had to work to make a living. The Cult of Domesticity advocated four cardinal virtues—piety, purity, domesticity, and submissiveness—which defined femininity so distinctly that deviation was impossible. Victorian women either had to be passive angels or active monsters. It is also worth noting that this concept is highly race and class-based, meaning it mainly applies to upper-class white women.

Many other similar motifs appear in literary history like “the mad woman in the attic" in Jane Eyre which later contributed to the feminist approach to literature as a theory holding the same name. Instead of discussing every term and explain what they mean, I want to emphasize the importance of gender as an analytical category in literary studies. The absence or scarcity of female authors in many literary eras is perfectly described by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar as “the anxiety of authorship." Just as Ms. George Eliot crawled during daytime with her doors locked like the hysteric female protagonist of Gilman’s Yellow Wallpaper, European and American women were so repressed by the family dynamics of their time that even the most privileged ones were hesitant to write or publish their writings. They knew they would not be recognized, and they feared the consequences of being more than they were allowed to.

In short, literature written by women is itself feminist liberation—a powerful urge that led women all around the world to fight for each other's existence. This aspect must be taken into consideration as a part of the historical background when examining the literary works of the past centuries. As Andrea Dworkin puts it more explicitly, "No woman could be Nietzsche or Rimbaud without ending up in a whorehouse or lobotomized."

William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience

p.s. If you enjoyed reading this, I will also be posting short articles on Medium. I would appreciate the support *-*

#feminism#literature#study#studyblr#poetry#literary studies#study notes#art#woman#gender studies#gender#struggle#analysis#victorian#19th century#victorian literature

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

*anything mildly inconvenient happens*

*sighs* picks up pen and journal

#school#notes#study#student#study aesthetic#studying#studyblr#high school#study notes#studyspo#dark academia#aesthetic#english#literature#academia#productivity#study hard#light academia#literary studies#romantic academia#writing#writer

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

sparrowinlondon

#london#neighbourhoods#streets#hampstead heath#winter#snow#literary studies#fictions & imagination#ivy#history#victorian#red brick walls

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Indeed, in so many gothic works the landscape represents more than just a setting; it is a threatening embodiment of the land itself, of that oft abused supplier of our human needs. Such landscapes not only foster an important element of terror, but also represent a sort of warehouse of cultural and individual anxieties relating to the social issues in play.

Matthew Wynn Sivils, “Gothic Landscapes of the South” from The Palgrave Handbook of the Southern Gothic

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

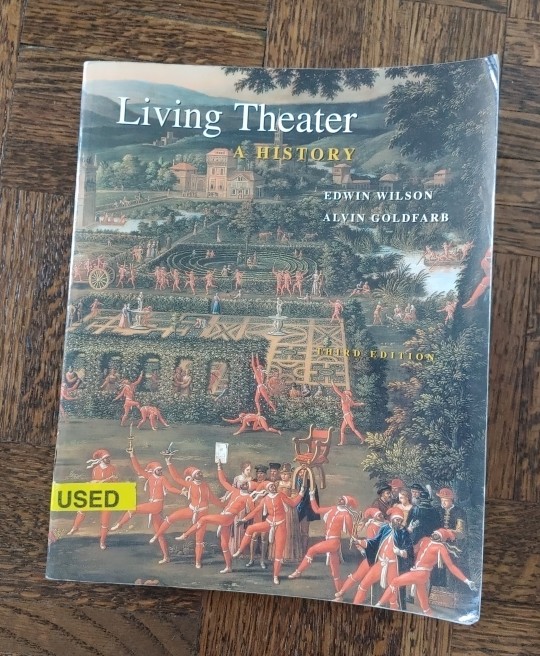

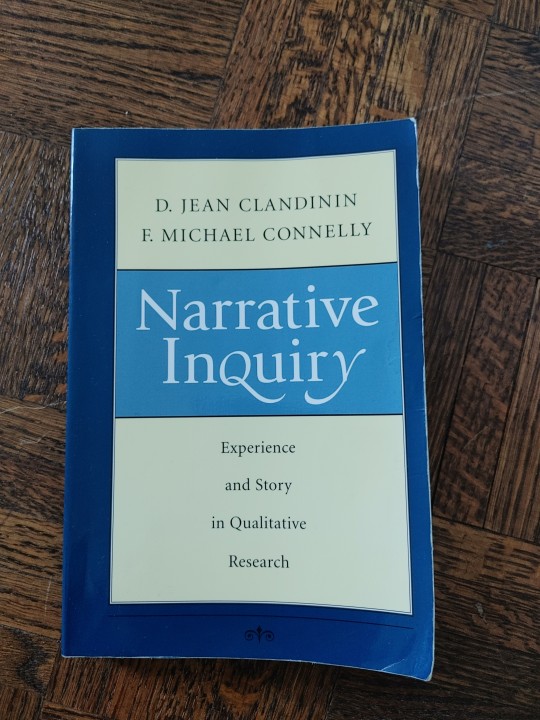

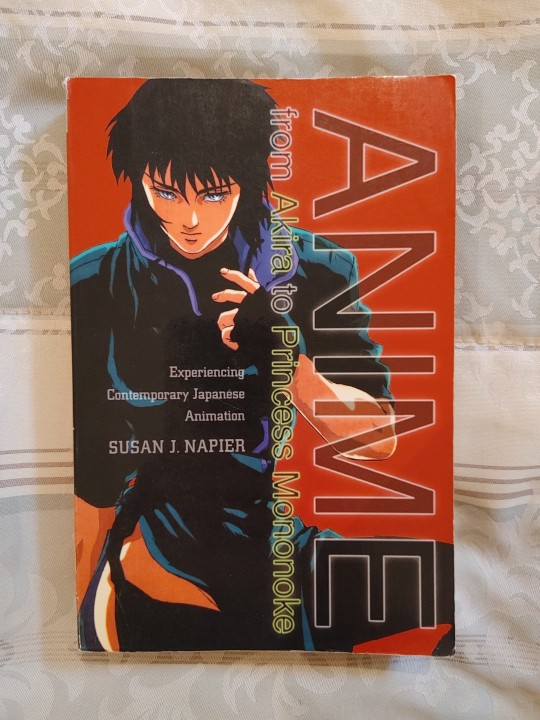

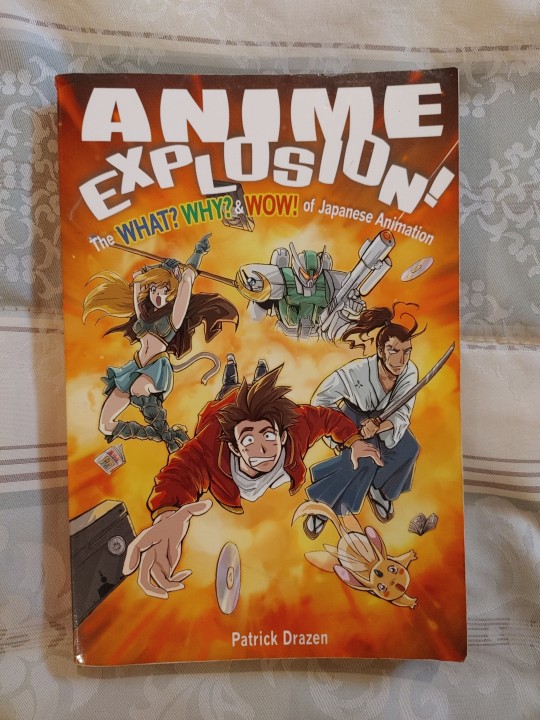

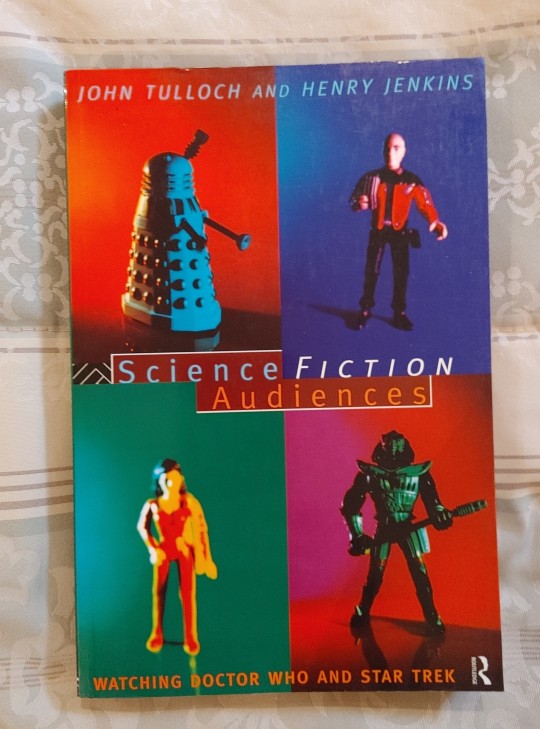

Attention Scholars and Students! I am purging the last of my texts from my theatre and communicatios/literary theory/fandom studies.

I would far rather these books go to someone who's going to use them for their own school work than to just throw them in a Little Free Library.

Message me and I will send you the book!

#fandom#acafan#acafandom#academic#fandom scholar#fanthropology#fanthropological#fandom studies#anime studies#doctor who#wheadon#media research#media studies#literary studies#audience studies#free textbooks#narrative studies#narrative inquiry#journal of popular culture#cultural theory

23 notes

·

View notes