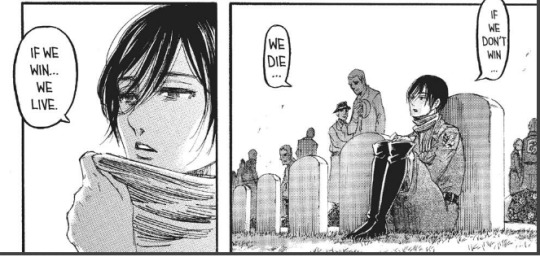

#the protagonist starts off already knowing the thematic truth

Text

Friendly reminder that the suffering and torment Xie Lian experienced actually made him LESS kind, and the lessons he learned as a result of that pain were that human life is meaningless and compassion is worthless and people don't deserve your help or care or love for them. Xie Lian had to backtrack and reject these new lessons in favor of the old ones he had already known in order to return to being kind.

Xie Lian losing everything he loved and knew, being stripped of his power, autonomy, safety, and community, and being ridiculed and humiliated, did not teach him anything worth knowing. He did not learn any valuable or important lessons from it. In fact, he needed to consciously decide that he wasn't going to let it change him and work to go back to the person he was before all that shit happened in order to avoid turning evil.

#TGCF#Xie Lian#Heaven Official's Blessing#i thought we were past this discourse but it's on my dash again#xie lian did not need to endure all that crap to learn any lessons#xie lian does not have a hero's journey!#TGCF is a flat arc#the protagonist starts off already knowing the thematic truth#it's the rest of the world that believes a lie

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Principles of the Steadfast, Flat-arc Protagonist

Last week I debunked six myths about the steadfast (also known as the flat-arc) character. Now, I would like to share 6 principles of writing a positive steadfast protagonist.

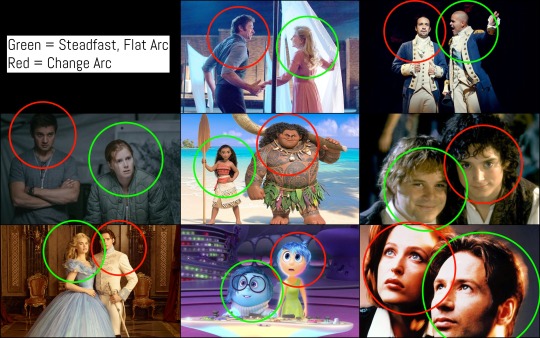

Steadfast/flat-arc characters are characters who don't drastically change their worldviews over the course of the story. In contrast, a change character will do largely a 180 flip in worldview from the beginning of the story to the end of the story.

For example, in Wonder Woman, Diana begins the story with the perspective that we should fight for the world we believe in. At the end of the story, she proves that true by using it to defeat the antagonist (this helps make up the story's theme). But in Frozen, Elsa begins the story with the worldview that one must be closed off to be safe and authentic. Because of the story, she learns that, actually, we must be open to be loved authentically (that might mean we get hurt, but some love is worth the hurt). This enables her to set things right, which proves that perspective true (and helps make up the story's theme).

Both flat-arc characters and change characters have negative versions: a character who remains steadfast to an inaccurate worldview and suffers punishment for it, and a character who changes from a true worldview to an inaccurate one and suffers punishment for it. Negative versions of each type are harder to find, but not nonexistent.

Almost all protagonists are positive change-arc protagonists. This means that almost all writing resources help writers write positive change-arc protagonists. This also means there are very few resources to help writers write steadfast protagonists.

You often can't apply change-arc advice to steadfast characters. It doesn't work.

Luckily, whichever protagonist type you're writing, each story actually has pretty much the same structural pieces--they're just arranged differently. Some are reversed while others receive more emphasis.

Today I'm going to explain how these pieces are different for a positive steadfast protagonist story, in comparison to the common positive change protagonist story.

This is a little like being left-handed in a right-handed world. That's it--the steadfast protagonists are the lefties of the storytelling world.

First, I would like to acknowledge those in the industry who have helped me understand the flat-arc protagonist and therefore influenced this post. If you want to learn more about this protagonist, check out these resources:

K. M. Weiland's Character Arc Series (Katie is amazing and this is honestly the best resource I've found so far on flat-arc characters.)

Character Arcs by Jordan McCollum (This book has a brief section on the flat arc.)

"Character Arcs 102: Flat Arcs" at The Novel Smithy (Lewis succinctly breaks down the flat-arc protagonist's three-act structure.)

Dramatica Theory (I already mentioned last week how Dramatica uses the term "steadfast" instead of "flat arc")

Writing Characters Without Character Arcs by Just Write (Youtube video)

I'll also be doing more posts on this protagonist type in the future.

1. Reversing Orientation: Change <--> Steadfast

Despite being the "lefties," almost every story will feature a key flat-arc character, like I mentioned last week:

In stories that have a change protagonist, the steadfast character will be the Influence Character. The Influence Character is typically someone the protagonist has an important relationship with, especially through the middle of the story. This is usually a love interest, mentor, or sidekick, but it can be almost anything. Of course, there are variations to the Influence Character, and you can learn more about them in my article on them. The Influence Character also serves as a thematic opponent, to some degree.

Why is the change protagonist most commonly paired with a steadfast character?

Dramatica Theory argues that it's because in order for a story to feel "complete" or "whole"--to properly mimic the human experience--we need to witness each perspective. Otherwise, it feels like something is missing.

It's not impossible to have a change protagonist be paired up with another change character, it's just that when this happens, usually an outsider who is steadfast gets involved and becomes the real Influence Character for both of them. It's also not impossible for the "Influence Character" to be more than one person. A story may have multiple Influence Characters, or even have a group that functions as the Influence Character.

In a story that features a flat-arc protagonist, the types are reversed. The Influence Character becomes a change character:

Moana is steadfast while Maui is change.

In Arrival, Louise Banks is steadfast while Ian is change.

In Cinderella, Ella is steadfast while the prince is change.

In Princess Mononoke, Ashitaka is steadfast while San is change.

In Wonder Woman, Diana is steadfast while Steve is change. (Steve's change isn't as drastic, but if you watch, he moves from disbeleiving the world Diana talks about, to believing in it.)

Usually, this pairing is positive steadfast protagonist and positive change Influence Character. This means that the Influence Character will usually start on the inaccurate worldview--the opposing side of the thematic argument. They will at least voice or tap into it in some way. By the end, they will have an accurate worldview, adopting the steadfast protagonist's perspective.

Generally speaking, anyway, as there are of course exceptions and variations.

So in a sense, when working with a steadfast protagonist, you are reorienting the structure to focus on the steadfast character, instead of the change one.

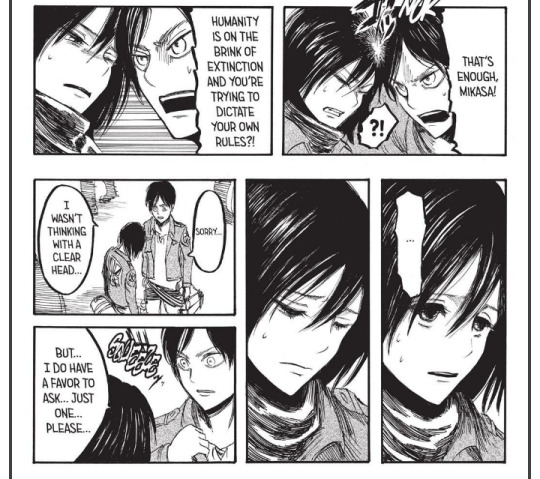

2. Inaccurate Worldview: Within <--> Without

The positive change protagonist has an inaccurate worldview in the beginning--this is sometimes referred to as the "lie" (as K. M. Weiland says it), "misbelief" (as Lisa Cron says it), or "flaw." He will overcome this on his journey and embrace the accurate worldview--the "truth." The truth is also the thematic statement.

The positive steadfast protagonist has the "truth," the accurate worldview, the thematic statement, from the beginning. This means that the inaccurate worldview needs to come from outside them. They need to encounter it in the environment.

You need to have the inaccurate worldview present. Otherwise, there is no opposing argument, no moral conflict.

A theme is essentially an argument about how we live our lives. You can't win an argument if no one is disagreeing. Someone needs to oppose the truth--I like to think of this opposition as the anti-theme. It is essentially the "lie," "misbelief," or "flaw." It is the worldview that is proven wrong by the end of the story.

It's just that with the flat-arc protagonist, that will hit them more from the outside. They will either:

- Enter a society run by the inaccurate worldview

- Have the inaccurate worldview enter their society

- Already live in a society riddled with the inaccurate worldview

Remember, a "society" is simply a collective--it can be as small as a school club or as big as a global government.

I don't know for sure that it always has to be a collective, but even if it's primarily an individual, the inaccurate worldview will still be within the surrounding characters--so in a sense, still part of the environment and society.

In Arrival, Louise is quickly surrounded by people who don't value or understand communication, or how it can avoid confrontation. She does. But she has to put up with that opposition and convince others to share her perspective.

In Princess Mononoke, a demonic boar full of hate and rage enters Ashitaka's peaceful society. After killing it, Ashitaka must journey far away to a land ruled by hate--where he is the only person who stands for peace.

In Wonder Woman, Diana must leave her society behind and enter a world war where humankind doesn't simply fight for a better world, but actively kills the innocent.

Rather than the protagonist transforming within, the positive steadfast protagonist will transform those around them, making the environment a better place as they hold steadfast to the true, accurate, worldview.

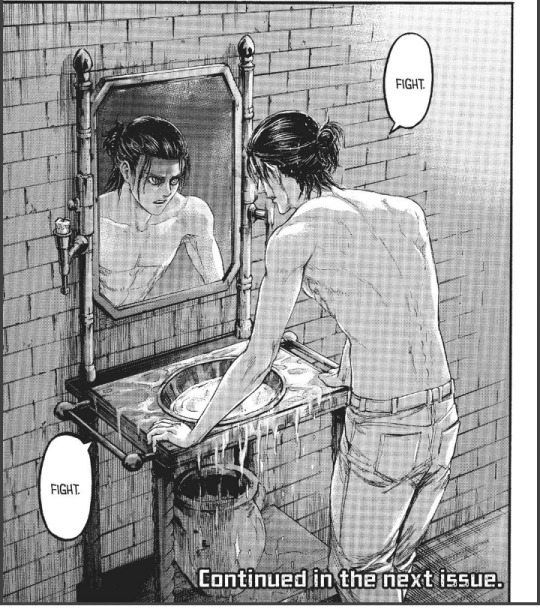

3. Internal Journey: Changed vs. Challenged

There is sometimes this idea, this . . . inaccurate worldview 😉 in the writing community that steadfast protagonists can't have rich internal journeys. As someone who loves the internal journey the best out of the plotlines, and who loves many steadfast protagonists the best, I don't find this to be true. Some of the most emotional internal journeys I've experienced, have come from positive steadfast protagonists. And one doesn't have to look far to find examples: The story of Jesus in the New Testament has moved whole nations.

It's fair to say that some steadfast protagonists don't have much of an internal plotline, like classic Superman or 007, but that has more to do with structuring plotlines than it does with character arcs.

For the change protagonist, the internal journey will largely be about transformation--a change. It's a journey to become a better person, and that can be a rich journey indeed.

For the steadfast protagonist, the internal journey will be a test of their beliefs--a challenge. It's a journey about ultimately choosing to hold strong in what you believe in, even if it seems the whole world is against you, (and for a steadfast protagonist journey, that's probably a good idea).

In a strange way, though, these two internal journeys are two sides of the same coin. After all, the change protagonist believes his worldview is the accurate worldview--that's why he has it! He doesn't believe, or at least doesn't clearly see, that he needs to change. The obstacles of the plot will reveal to him he could be wrong, that he needs to fix something about himself. Similarly, the steadfast protagonist believes she's right, and the obstacles of the plot will challenge that by suggesting she could be wrong and needs to bend to the opposing force.

One might argue that the main difference, then, is that the positive change protagonist succeeds at the end by changing, and that the positive steadfast protagonist succeeds at the end by not changing. But I think most of us would agree it'd be more helpful if we differentiated them a little more.

Because the transformation aspect is missing from the steadfast character, it becomes arguably more important to nail the other features of the internal journey. It's not that those features don't exist in the change journey, it's just that without the change itself, they carry more weight and become more centre stage (generally speaking).

One of the aspects that becomes critical, is that the steadfast protagonist needs to pay a high cost. If having an accurate worldview and using it to change the world around them is about as difficult as a stroll in the park, it can become annoying fast. Real life just isn't like that. Even when we are doing good, we still experience hardship, suffering, and opposition. If the steadfast protagonist doesn't have to pay a cost, then they're not really having their beliefs tested.

While a change protagonist's pain may come more from being wrong and having to change--in a sense being "punished" for being wrong--a steadfast protagonist's pain will come from being right and suffering for it, and having to remain true despite that. Essentially they embody the adage, "No good deed goes unpunished."

For example, in Princess Mononoke, in Ashitaka's quest to bring peace to a world at war, Ashitaka must endure a bullet, stabbing, and face death. He's no one's enemy, but he sometimes gets treated as one. He would likely suffer less if he just joined the war efforts and embraced the inaccurate worldview, or if he simply left. Likewise, Jesus holding true to his beliefs in the New Testament, led to him being crucified.

As the obstacles of the plot mount, the steadfast protagonist will be asked to doubt their worldview. Some steadfast protagonists entertain doubt more than others. This may lead to the protagonist wavering in his or her beliefs. Ashitaka entertains doubt only a little, while in Wonder Woman, Diana is brought to her knees by doubt, nearly turning her back on her beliefs. Doubt will usually be strongest at the end of the middle--what some call "The Ordeal," which will lead into the “All is Lost” and "Dark Night of the Soul" moments.

Often, in order for this to work well, the opposing argument needs to appear valid. It needs to look as if the inaccurate worldview could actually be the accurate worldview. It needs to look like the anti-theme could actually be the theme. Like the "lie" could actually be the "truth." This means it becomes perhaps even more important, for you as the writer, to show the legitimate strength of the opposing perspective. If it's obvious the theme is the "truth," then there is no need for the protagonist to experience doubt. There isn't even a need to have a thematic argument. The protagonist may also (or sometimes, instead) doubt his ability or worthiness to live and spread the truth. For more on the power of doubt with flat-arc characters, check out K. M. Weiland's article "Why Doubt is the Key to Flat Character Arcs."

Like costs, stakes become more critical. Stakes are potential consequences. They put pressure on the protagonist and give their choices meaning. If sticking to their worldview means they must suffer steep consequences, their actions carry more weight. It's easy to do what is right when you have nothing to lose. If I found a lost dog, it would be easy for me to look at its tags and return it to its owner. If I found a mean dog trying to bite my hand the evening before my piano recital, wrangled it, saw it belonged to my worst enemy, and still chose to return it--that reveals just how committed I am to saving those lost.

The steadfast protagonist needs to be challenged and tested--one of the best ways to do that is to raise the stakes. Raise them high enough to get them to hesitate, to doubt, to pay a steep cost. In a rich internal journey, we want to push the steadfast protagonist to her limits. What is it going to take to get your protagonist to consider the opposing side? To tempt her to give up her beliefs? In a sense, through the middle, we are really throwing temptations at the protagonist, trying to get her to give in to the opposing argument. Sometimes the most powerful way to do this, is to give the protagonist conflicting wants.

In reality, the audience can't fully see just how steadfast the protagonist is, if she doesn't have to suffer costs, legitimate doubts, and high stakes. It's only in the face of adversity, can we measure true character.

That is the meat of the steadfast protagonist's inner journey.

* I would like to add just one warning, however. In your quest to make your steadfast protagonist struggle, it's important he or she still has some victories along the way. Just as it becomes annoying if the steadfast protagonist never has to struggle, it can also become annoying if the steadfast protagonist never has any success.

4. Ghost/Wound: Inaccurate Belief <--> Accurate Belief

(This is a repeat section from last week. I just thought it would be helpful to have all these elements on the same post.)

A "ghost" is a past, significant, often traumatic event that motivates the character to adopt an inaccurate worldview (the "anti-theme" or the "lie" or the "misbelief"--depending on your preferred terminology). In the industry, this is also sometimes called a "wound." You can learn all about ghosts/wounds in my article, "Giving Your Protagonist a Ghost."

But in a positive steadfast protagonist, this is often flipped. The ghost is often a past, significant, sometimes traumatic event that motivates the character to adopt the accurate worldview (the "theme" or the "truth" if you prefer).

For example, Cinderella's mother, while on her deathbed, tells Cinderella to always be kind. This motivates Cinderella to do just that.

Of course, not every character will have a ghost addressed in the story.

For the positive steadfast protagonist, the ghost may be largely resolved.

But not always. They may not have complete closure and peace. And it's possible they are still traumatized by the event.

Sometimes adhering to what is true can be nearly as haunting as having regrets. It's just that the haunting will come from either the cost of the truth, or, a lack of power--a lack of control--during the ghost. Generally speaking anyway.

In The X-Files, Fox Mulder, in the overall story and theme, is a positive steadfast character. The ongoing theme is an argument of belief vs. disbelief. (The motifs, "I want to believe" and "The truth is out there" speak to that.) However, Mulder has an unresolved, traumatizing ghost: his little sister was abducted by aliens.

This event cements him to the thematic truth of belief and motivates him to investigate anything unnatural. But this happened at the cost of his sister.

Sometimes the trauma comes from not being able to do anything, just as Mulder was powerless to stop the abduction.

Other times it may come from not being able to stop a loved one from choosing the inaccurate worldview--the "lie," "anti-theme," or "misbelief." The steadfast character may be haunted by the outcome of someone else choosing the lie.

5. Want vs. Need <--> I Want the Need

For all other character arcs, what the character wants and what the character needs will be two different things. You can learn about want vs. need in depth here.

In a positive change arc, the protagonist will want something that will manifest in concrete goals, which helps make up the plot of the story. Elsa wants to live in isolation to be herself, so she runs away and creates an ice castle (accidentally freezing the kingdom in the process). The need will be a realization that is thematic--it will be the thematic statement. Elsa needs to learn to be open to love to be authentic--that's what will actually solve her problems.

For the positive steadfast protagonist, the want and the need will be more closely aligned. The protagonist wants what is needed. In a sense, he starts the story with the need. However, the need still has to be applied to the concrete world, which isn't necessarily easy. In a sense, we are taking the need that is within, and trying to apply it to the "real world," which is without. For example, if I know I need to exercise to be healthy, then I probably also want to do that. But that means I still need to put in the work. It also doesn’t mean I know everything about the process--because I may not have full experience with it. I might need to learn a new skill, like how to swim properly.

In Moana, Moana already knows who she is on the inside (thematic statement)--she knows she and her people are meant to sail--but she still has to learn how to sail.

Ashitaka knows the world needs peace, but he doesn't know how to make peace happen within a war. He knows how to have an inner peace, but he doesn't know how to make the external world--the societies around him--peaceful. He's trying to figure it out along the way. He's trying to figure out how to apply a personal experience to the public environment.

The protagonist may still need a greater, more complete understanding of the need, the theme, and how to properly apply it to the real world. We all want to solve world hunger--but how do we actually do that?

On top of that, as the protagonist struggles to meet the need, you may want to tempt him with a conflicting want. In Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 2, Peter Parker both wants what is needed (to be a self-sacrificing hero) and wants a personal want (to live an ordinary life with Mary Jane Watson). This creates inner turmoil. (And also gives more meat to the internal journey.)

As tests and doubts get heavy, the other want may appear more "right" and enticing. It will almost certainly appear easier.

As tests and doubts get heavy, the flat-arc protagonist may lose sight of the need. In Wonder Woman's "All is Lost" moment, Diana doesn't want to fight for the world she believes in anymore. The world doesn't deserve it. She loses sight of the need, the theme.

In short, the struggle comes from trying to apply the need, being tempting with another want, and/or losing sight of the need.

6. Protagonist Changes <--> Cast Changes

I touched on this earlier, but it's worth giving its own section.

In many positive change protagonist stories, the protagonist will change to the worldview some of the cast members around him have. In Spider-verse, Miles Morales must learn to persevere like the other spider people around him.

In many flat-arc protagonist stories, the cast around the protagonist will change their worldviews to match hers. Moana's journey changes not only Maui's understanding of himself, but Te Fiti's, and everyone's on the island as well.

In some flat-arc stories, this can be critical at the "All is Lost" moment, because if the protagonist is suffering serious doubt, the supporting cast can bolster her by now acting on the accurate worldview, which is essentially what happens in Wonder Woman. As Diana crumbles under doubt, all of her team members enter the fray, prepared to die to make the world a better place. Their selfless sacrifices wake her up, and she recommits to the theme, finding the strength to take on Ares.

Some stories may emphasize these changes more than others, but pretty much always, the Influence Character will at least experience a noticeable change--usually demonstrated near the same place in structure that the change protagonist will change.

But applying the steadfast protagonist to story structure will be for another day (hopefully in the coming weeks). Stay tuned!

#writing tips#writing tips and tricks#writeblr#fanfic#nanowrimo#writing reference#writing advice#protagonist#steadfast protagonist#flat-arc protagonist#moana#arrival#princess mononoke#wonder woman#character#character arcs#writing help

264 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can't speak for anyone else but I for one would love an incoherent rant about the dark age of the law plotline

Alright buckle up kiddos.

So I have a lot of complaints with Dual Destinies as a whole. It’s a poorly paced mess, the final confrontation was deeply underwhelming, it has all these weird “Gotcha” moments where they put in the most bizarre, logic breaking plot twists and then undo them within ten minutes completely for shock value. And yet, despite all of these issues, there is nothing in this world that pisses me off more than the words “The Dark Age of the Law.”

I hate the Dark Age of the Law subplot more than literally any other thing in Ace Attorney. It is a complete failure of a story in literally every possible way. It not only doesn’t work within the context of Dual Destinies, it also completely flies in the face of everything we understand about the original trilogy! It!!!! Sucks!!!!

But no. That was too coherent. I think we should break this down.

First I’m going to start on a macro level. The Dark Age of the Law is the clearest indication to me that the writers of Dual Destinies never played another Ace Attorney game. They treat this Dark Age of the Law thing like this big bad, this shiny new toy, this never before seen wonder, but??? Corruption has been a CENTRAL part of every single AA game since game one!! Since case 2 even!!!

The Dark Age of the Law is this whole idea that people have lost their trust in the court system. And what do they site as the catalyst for this breaking of trust? Phoenix Wright’s disbarment and Simon Blackquill’s arrest.

And okay. Phoenix Wright’s disbarment is a reasonable one. Phoenix was sort of known for being this paragon of truth and justice, this man willing to do what it took to find the truth and protect people in need. His name being smeared through the mud could very well shake up the foundations of trust that the people had in the court system.

But Simon Blackquill? Simon FUCKING Blackquill shook up people’s faith in the court system?? Simon Blackquill is the reason that people are convinced that the entire system is full of lies and deceit? SIMON CONFESSED!! He didn’t even do anything corrupt!! He murdered a woman, sure, but he then immediately lets everyone know “Yes, I super did this murder. No one else.” And they treat it like it’s this big turning point??

LANA SKYE!! You guys remember Lana Skye? The Chief Prosecutor at the time, who was accused of murder, and who still went to prison for doing like a million other crimes after being blackmailed by the chief of police.

SPEAKING OF WHICH the fucking CHIEF OF POLICE was a murderous monster who blackmailed people and also murdered. Did that have no effect on people’s trust in the courts?

Manfred von Karma? Never lost a case in 40 years, literally everyone talked about how he and Miles were KNOWN to be corrupt? Also, you know, murdered a man in cold blood?

Blaise Debeste??? Chairman of the fucking ETHICS BOARD???????? Like!!! That’s some deep fucking corruption right there!!!! And he constantly talks about the mysterious disappearances around him of people who disagreed with him, does that not shake your faith?!

In Turnabout Sisters, as early as case 1-2, Redd White calls up the Chief Prosecutor (who also is not Lana, just to be clear) and demands his complicitness in covering up his own crimes. That’s how central corruption is to the entirety of Ace Attorney.

And you’re going to look me in the fucking EYES and tell me Simon Blackquill, some 21 year old nobody with no power or influence, who theoretically stabbed a woman and made no effort to cover that up, is the reason the courts have lost the faith of the people? You have the NERVE??? the AUDACITY??? the fucking GALL????? to tell me that SIMON is what caused this? The system was never trustworthy, and if it was, what the FUCK did Simon have to do with changing that???

Horrible. Terrible. Disgusting.

BUT

Let’s pretend for a moment that Dual Destinies existed in a vacuum. First Ace Attorney game you’ve ever played. Never touched another one in your life. If you were unfamiliar with the world that Ace Attorney has already spent six games establishing, does the Dark Age of the Law subplot hold up?

No. No it doesn’t.

So as I’ve said a million times before, it was clear that Dual Destinies should not have tried to juggle three protagonists. It just didn’t work. They learned their lesson and booted Athena out of that protagonist title in SoJ, and as much as I hated that decision, it was at least a much stronger overarching story for it.

Now. There were three main throughlines in Dual Destinies. Athena’s story centered on introducing her, of course, but it also was about her struggle to save a friend who needed saving from the law and also himself. It was very AA1 in that way.

Apollo’s story was a little harder to outline, because a lot of it is saved for the last couple of cases, but it’s really about his relationship with Athena. Coming to trust her, his trust in her being shaken, struggling to overcome that, grief, loss, yadda yadda, and I have my criticisms of how it’s handled, but that’s the gist of it.

And Phoenix needed a story. So they made up this stupid fucking bullshit garbage and dumped it in his lap and said “Here you go, best friend! Our dear money maker! This is what you’re working with!” And then they proceeded to use it to beat the shit out of Phoenix until he started spitting out dollar bills.

Okay no sorry I have no idea what the fuck I just said but liSTEN

The Dark Age of the Law storyline was clearly supposed to have some significant thematic relevance to the story, given how hard they were hammering it into us in case three. It was supposed to mean something, and I think it was supposed to mean something to Phoenix in particular. After all, he and Miles won’t stop TALKING ABOUT IT GOD MAKE THEM SHUT UP

The Dark Age of the Law subplot had nothing to do with that final case. Remove it, and nothing changes, because, again, Simon had nothing to do with the corruption in the first place, and the Phantom certainly had nothing to do with corruption. It’s so surface level. “Uh oh, people don’t like the courts. If you can solve this unrelated crime, everything will be fixed.” And then he does (also Athena should’ve been the one to win the case, but that’s a different problem) and nothing ever comes of it, other than “Hooray, you fixed the corruption!” He didn’t??? Miles what the fuck are you talking about????

If they had woven in the corruption throughout the story somehow, maybe it would’ve found some way to be impactful? But it was a floundering, half-thought-out subplot in an already bloated game that failed to give any meaning or help anyone develop as a character. Hell, it kept falling out of relevancy and only popped in to rear its head when the writers remembered it existed and decided to have yet another person remind us that THIS IS IMPORTANT GUYS NO REALLY.

Like! Okay. What if they tied it more to AA4? I mean Phoenix’s disbarment and subsequent return could’ve actually affected the plot. Have people actively mistrust Phoenix or something. Or maybe have it affect anyone in any way. Sure it divides the fucking high schoolers for that mess of a “power of friendship” storyline, but so could a plot about, I don’t know, electing a homecoming queen or something. It affected Athena for one case, but what did that even teach her other than “Trust your gut, sweetie, don’t do lawyer crimes!” Phoenix didn’t have an arc in this game, and he shouldn’t have had to, unless it was coming to grips with the fact that he was never going to get those 7 years of his life back and the smears against his character were always going to linger. But they didn’t do that, they just needed him in there for brand recognition.

I can handle a lot of bullshit in these bullshit lawyer games. That’s part of the appeal. But unlike most of the other bullshit, this particular threat was unsatisfying, meandering, and unnecessary.

#ace attorney#dual destinies#i love dual destinies guys really#but if miles says dark age of the law one more time#also was this coherent at all?#j#spoilers#meta

122 notes

·

View notes

Note

Advice on how to write subplots/weave them into the main story?

ohhh Subplots are fun. And very important for fleshing out your supporting cast, your setting, whatever you need to say that is tough to squeeze into the Main Plot.

This is all stuff I've learned from stuff other writers have said, from writing A Lot, and just trying to be aware of narratives in Everything I consume. It’s not a Universal Constant, you can and should experiment to find what makes things work for you, but this is what I’ve gathered on the topic:

1. I do think it's important to know some of your (potential) subplots from the very start. If you're writing fanfic or something based off another story, this makes it easy. If you're following a side character, the canon main plot becomes a subplot, other subplots fill in the gaps. You'll already know which characters you want to explore in greater depth.

If you're writing something from scratch, it means you have to explore your own secondary characters. How many allies does the protagonist have? What are they in it for? Is something threatening them? Are your characters going to be travelling? If so, what in the setting will they encounter? If you have even a vague idea of the things you want to examine in greater depth, then you can set them aside and either pepper them into your outline when action/tension seems low, or you need to fill a gap. If you're pantsing it'll mean you have a list of ideas in case you ever get stuck.

Pantsing makes it easier and harder to do subplots: it can become very simple to get lost chasing a plot bunny, but it can also be difficult to expand if you aren't aware of extra characters and setting details. This happened to me in November--I had a basic idea and because I was making up characters on the fly, I never fleshed them out and gave them their own motivations. So I never really got to include any subplots--I’m left with something very simple and concise. I’ll have to add in subplots in a rewrite.

2. All your subplots should be strongly connected to the main plot in some way. This could be a direct, physical connection (Ally 1 was displaced by Main Threat and is now looking to achieve X, MacGuffin was stolen by Antagonist or Underling and we must retrieve it for Encounter 2, Ally 2 has a history with Underling and wants revenge/to save them/etc).

Or, it could be thematic. Your story might boil down to one ideal, or a specific dichotomy, or a philosophical 'what if' question. Try to keep your subplots related to that--they can oppose the main theme, or compliment it, or bolster it. Whatever you think would be the most fun to write.

Subplots can also get the Protagonist something that strengthens them for the Final Confrontation. Succeeding at a subplot, or even failing, can win them allies, or tools to succeed later, or help them realize that something they are doing is wrong. It could even help only the reader to see that perhaps the Protagonist is doing something wrong, thus building tension as they wonder how the hero will overcome their flaw/whether they'll be able to succeed.

If you're a planner, make charts, connect pins with little strings, whatever you need to while you’re constructing your outline. If you’re a pantser, make notes as you go to either revisit ideas later, or fit in later as your characters make their own plans. Ask questions of everything and upturn as many stones as possible looking for surprises. Write hypothetical scenes/chapters and see if they offer you any ideas.

3. Don't add everything at once. Start off with the main plot, or an offshoot of that--just a bit of information. Add a little at a time, one or two new ideas per chapter, gradually expanding the world of your story. Subplots should never have higher stakes than the main plot, but they can add a sense of urgency if they have steadily escalating intensity. If they reveal things about the Main Plot, be it a truth about a character, or about the magic of the world, or some horrible secret, it'll make them feel Integral to the story. If you tried to extricate them, you'd tear up half the story. That's good. See if you can attach a Main Plot Point to a subplot whenever possible.

4. Sometimes it'll feel like it's getting cluttered. Maybe you have too many main players, too much going on. Look at examples of stories that have a lot going on. I found that in particular, Good Omens (Neil Gaiman, Terry Pratchett) and The Dark Lord of Derkholm (Diana Wynne Jones), dealt with that really well. These writers break things up, compartmentalizing all the subplots. Separate events and characters and points of view to cover more ground and flick back and forth between them. Do so in relation to how much is happening.

5. In the end, you have to bring everything together, and it's at that point that you need to strip back all the subplots.

Build the tension. Make it clear how everything has been building up towards the Final Confrontation. Show how much is at stake, not just for your Protagonist, but Ally 1 and Ally 2 and all the little encounters you had on the road. I’m not saying write out a summary of the entire story thus far, but show the growth, show what your characters are feeling about what’s to come, and what would happen if they failed. Show the themes that you’ve been building up.

Then, let them fall back to the reader's subconscious. It's time for the Main Plot. All that your characters have learned and experienced in the subplots, all the themes contrasting and supporting the main theme, will come to fruition now. It should result in catharsis, and drama, and a release of all the tension that you’ve been carefully piling on, and feel satisfying to the reader. You don’t have to conclude every subplot, but you should acknowledge the big ones at the very least.

TL:DR

The Main Plot: The basic pitch/premise/thread of your story, 'Protagonist faces X with the result of Y'

The Subplots: Exploring supporting character motives, the Setting, the Villains, etc, all with the purpose of propelling the reader towards the conclusion of the Main Plot.

Subplots make us care about the world and the supporting cast, they increase tension, they move us towards the Conclusion. They can feel to the characters like distractions/diversions from their goal, but in the background, they should always be used by the writer as a tool for furthering/strengthening the plot, directly or not.

#writing#writing asks#plot#subplot#keep in mind i'm essentially self-taught#but plot is a special interest of mine#i hope this is helpful to you!#also longer pieces will naturally have room for more subplots#test and learn the limits of your story

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you been asked yet to rank Trust eps? Cos I'm asking! But your the criteria for ranking I leave to you to decide.

Ahahahaha I’ll have you know I put way too much thought into this. :-D

Ok so first of all, there is no such thing as a bad episode of Trust. The whole thing is really tightly written, every character and plot thread has a purpose, and even the episodes that I haven’t watched over and over again are important to the overall story. And a lot of the impact of the show comes from things that are cumulative over multiple episodes.

That being said, I do have favorites. Since the definitive ranking of Primo’s outfits has already been taken care of, here is my ranking from least to most favorite based on some nebulous criteria of artistic/narrative effectiveness and emotional impact, my judgement of which is obviously highly subjective and also correct.

Under the cut because this got ummm unbelievably, ridiculously long.

10. The House of Getty (episode 1)

Sorry Danny Boyle and Simon Beaufoy, the pilot is my least favorite episode. Still think it was the wrong choice to open with a flashy (and, I can tell, expensive) sequence showcasing the death of a character we literally never see again. And, look, I’m an impatient viewer. If I don’t get someone to root for/emotionally identify with/otherwise catch my interest early on in a narrative, I’ll tune out. And Old Paul is not only unlikeable--far from a mortal sin in dramatic storytelling--he’s boring. I don’t care about any of his rich people problems, and I’m not the kind of viewer who can be kept engaged just by hating someone and watching them be terrible.

Some of the secondary characters in the Getty household do have interesting plotlines, but we don’t get to learn very much about them in the first episode. And I do think things get interesting once Little Paul shows up (although I maintain that the whole episode is more interesting if we understand what the stakes are for Paul getting the money), but if I had started watching this show with no context I wouldn’t have made it past Old Paul’s pre-coital erotica listening routine.

If this had been anything other than the first episode I might not have ranked it last, but extra penalty points for leading with your least interesting characters.

9. Lone Star (episode 2)

This episode is, I think, saddled by the fact that it has to do a lot of heavy lifting in terms of exposition and setup. It mostly works because Chace is an entertaining narrator, and once we get to Italy with Gail I think things zip along at a pretty good pace. Opens with an attempted rape to show how Bad the Bad Guys are, which is...not my favorite trope.

Once again, I think a lot of the information in this episode would have worked better if episode 3 had been episode 1. (We’d already know who Berto was when Chace meets him; we’d already know about the box of guns in the apartment; we’d know when certain characters are lying.) This whole show runs on the suspense of the audience being the only party who knows what’s going on with all the characters at once; I think trading mystery for suspense here was the wrong move. I also can’t help thinking there was pressure to front-load the well-known American actors in the beginning of the show at the expense of the strongest narrative choices.

Imo the best thing about this episode is the sort of...multiple competing images of Paul that emerge. His mom sees him as an innocent victim who couldn’t possibly have planned any of this. Chace sees him as a spoiled rich kid trying to swindle his granddad. Neither one of them has the complete truth.

Next we get into some episodes that are certainly not bad, but their greatness is more on the level of some bangin’ individual scenes than a whole package.

8. John, Chapter 11 (episode 6)

Again, this isn’t a bad episode. The main reason I put it near the end of the list is that the first time through I got sort of impatient during the first half. We, the audience, by virtue of our extra-textual knowledge, know that Paul can’t be dead, and we spend about half the episode before we know what really happened to him, which felt a bit too long to me.

This episode does have some fantastic individual scenes including: Leo talking Primo down in the farmhouse, Leo and Paul’s conversation about Angelo’s death, Gail being an absolute badass, and the meeting between Salvatore and Old Paul. A lot of these scenes are essential on a thematic level, but I don’t think the episode as a whole is the most streamlined.

7. Consequences (episode 10)

I debated for a while where to put this episode because the overall feeling of 57 Chekov’s guns going off in the space of one episode is SO satisfying, and the resolutions of some of the individual plotlines are delicious. Ultimately I would have liked more space for Paul and Gail and less Old Paul being grumpy about his substitute child museum’s mediocrity (although the scene with the bad reviews is hilarious). Once again I feel like the show creators felt they had to pull the focus back to Old Paul to wrap things up and I just. don’t care.

That being said. The resolution of Primo’s storyline? SO SATISFYING. And tbh I don’t dislike the scenes that exist with Paul and Gail; even the happy scenes have this poignant tone to them. I think they were trying to deal with the fact that his irl story is just...incredibly fucking tragic, and you can see a bit of the strain showing.

6. Kodachrome (episode 7)

I know episode 7 is not one of your personal favorites, but it’s the one where I think jumping between multiple plotlines/sets of characters is used to the most satisfying dramatic effect. It has this sense of dramatic irony that feels like some Shakespearean family tragedy. The whole episode, we are hoping that Paul Jr. will finally do the thing we want him to do, which is stand up to his father. And he does it--but at the absolute worst, most selfish and destructive moment possible.

Paul Jr. may be the literal worst, but I do have compassion for him in the flashbacks, mostly because it seems painfully apparent that no matter what he does, he will never be able to please his father. But he doesn’t seem to realize this, and he keeps trying, even as it’s destroying him and his relationship with his family. Credit to Michael Esper for his performance for making me feel a smidgen of compassion for this bastard.

I think the other thing this episode shows is how both of Paul’s parents keep putting him, a child, into roles and circumstances that he shouldn’t really be in. He’s wandering around through what seem like very much adult environments with his dad and Talitha in Morocco. In the Trust version of events he’s there when Talitha ODs and is the one trying to revive her while his dad is having a breakdown in the corner. Gail seems like the more responsible parent but there’s something about her bringing Paul as her “date” on a night out, and the understanding that this is a thing that happens regularly...to me the disturbing part is not so much bringing a young kid to a party with adults but the unspoken expectation that Little Paul will fill the void of companionship that his father has left empty. (Gettys expecting Little Paul to step in to cover for the failings of his father is a repeated theme, and it even plays into the ear thing. His family has failed to pay the ransom, so this is now a problem he has to solve himself.) Combine this all with Leonardo going, um, excuse me but what the actual fuck is wrong with your family? and I think it makes a very effective episode. And the last couple minutes had me yelling NOOOOOOOO GODDAMMIT because you can see what’s going to happen and you’re just watching it unfolding like a car wreck. Also has one of my hands-down favorite scenes, of Paul and Primo in the car waiting for the ransom.

5. White Car in a Snowstorm (episode 9)

The ~ D R A M A !!! ~ This episode is an opera. I mean this whole show is dramatique but episode 9 really leans into the vivid imagery--that snowy highway in the mountains above the sea, the all-white ransom exchange, Paul clinging to the pole at the shuttered Getty gas station, some Very Serious Mobsters throwing the ransom money around like idiots in a moment where you’re encouraged to be happy along with them.

This is also one of my favorite episodes for Primo and for Primo and Paul’s weird sometimes-alliance. Primo walking away from Salvatore to go tell Paul “they always pay in the end”? Primo and Paul teaming up to argue with Salvatore about why Paul shouldn’t die? Primo being all threateny to the doctor treating Paul because somewhere deep down he is worried (that’s my take and you’ll never convince me otherwise)? Primo dressing up to fake-scab on a postal strike in order to find a misplaced severed ear? All gold.

Fun fact: the letter Gail writes to President Nixon did happen in real life, but as far as I can tell the phone call did not. The real details of who convinced Old Paul to finally pay (some) of the ransom are considerably less cinematic. They’re the same amount of sexist though!

Ok now we are getting to the top tier...

4. That’s All Folks! (episode 4)

This is definitely the episode that took me from “ok this is fun” to “oh holy shit I’m invested now.” It’s the episode where we get introduced to most of the Calabrian characters and their world. It’s also the episode where we start to realize that Primo is not just a fun antagonist but is really a parallel protagonist to Little Paul, with his own set of relationships and motivations that we start to see from his POV. (I’d argue that, with the exception of his very first scene, we’ve mostly seen Primo through other characters’ gaze up until episode 4, and this is the point where we start watching him as like, the character whose pursuit of a goal we’re following over the course of the scene.)

This episode ranks high for capturing so much of the weird mix of tones that makes Trust work. It can be very funny. (I never fail to fuckin lose it when Fifty is on the phone with Gail the first time and when he’s talking to the thoroughly unimpressed newspaper switchboard operator.) It has this weird unexpected intimacy between characters you wouldn’t think would connect with each other. (Primo and Paul, Paul and Angelo; in retrospect the arc of the relationship between Primo and Leo gets started in that scene in Salvatore’s kitchen.) And it has one of the show’s absolute best record-scratch tone shifts when Primo gets the ransom offer. I remember saying “oh FUCK” out loud the first time I watched the end of that episode, when Primo comes back to the house, visibly drunk and clearly furious. We’ve seen him be violent plenty before now in the show, but always in a controlled, calculated way. This is the first time we see his potential for out-of-control rage-fueled violence and he’s terrifying!

3. La Dolce Vita (episode 3)

I stand by my claim that this episode (with a few minor continuity adjustments) should have been the pilot. Can you imagine a title card that’s like “Rome 1973” and then away we go with Paul snorting coke and taking racy photos and jumping on cops and fucking his girlfriend in what is definitely not proper museum etiquette, and then the smash cut to Primo intimidating and robbing and murdering people? And that’s the opening of the whole show? And you’re like how are these characters connected and then they meet each other and it’s the fucking sunflower field scene??

Anyway aside from the fact that I think knowing the information in this episode would have made episodes 1 and 2 more interesting...it’s just a great fucking episode. It’s kinetic and propulsive and funny and tense and violent and features Primo’s sniper skills and his ass in those cornflower blue trousers. I rest my case.

2. Silenzio (episode 5)

I’ll be honest, I went back and forth on the top two a bunch. Silenzio is definitely my personal favorite episode, and I’d argue that it’s the best written, in terms of what it accomplishes narratively, which is to keep you emotionally invested in both Paul and Angelo trying to escape with their lives, and Primo and Leonardo hunting them down. That’s so fucking hard!! And yes some of it is great acting but it starts from the foundation of the writing. It’s just such a perfect little self-contained horror movie, and it has this profound sense of fatalism to it, because you know from the beginning (if only by virtue of only being halfway through the series) that Paul is not going to escape, and you sort of know that there is only one way this will end for Angelo. And yet they escape by the skin of their teeth so! many! times!

It’s also the episode where you see how much power the ‘Ndrangheta has over people’s lives in this community: Salvatore is like God, calling his servants to him with the church bells. Combine that with the visuals of two characters running for their lives mostly on foot through this unforgiving landscape, and you really get the sense of this environment as a harsh place where most people have a very constrained set of choices, and the claustrophobia of that. You get the sense in this episode that everyone is trapped in these expectations of violence and duty and honor. Angelo did what anyone with compassion would do, and saved Paul from what seemed like certain death, and he’s doomed for it. At the same time Primo is doing exactly what anyone would expect him to do in response to a subordinate who disobeyed him. In some ways the end of the episode feels inevitable, unsurprising, and yet they do SUCH a good job of winding up the tension until the literal last seconds of the episode, and then releasing it with a big dramatic bang. It’s so good!!

1. In the Name of the Father (episode 8)

Ok I’ll be honest the ONLY reason In the Name of the Father edged out Silenzio for the top spot is that it is really clear they pulled out all the stops in terms of making this episode feel extra heightened in a show where everything is already heightened. Like, the cinematography is different? They still use handheld a lot but I swear there are more still shots and more extreme, editorial camera angles like that shot of Francesco looking upward in church where the camera is looking down from above him. I can’t tell if they actually tweaked the color grading or if the bright white and blood red just stand out against the Calabrian color palette which is mostly earth tones, browns and greens and blues.

There are just. So many layers to this episode. The imagery! The literal sacrificial lamb at the beginning, Francesco being guided by Leonardo through an act of violence against an animal, something that I’m sure they don’t even see as violence but just part of farm life, part of survival and in this case part of a celebration, but something that fathers teach their sons how to do as part of becoming a man in this world. Paul as the metaphorical sacrificial lamb later, drawing parallels to Jesus (the lamb of God), Isaac (a father sacrificing his son), any number of martyred saints, pick your Catholic imagery. The blood of the lamb on the tree stump and Paul’s blood on the stone. The communion wafer (the body and blood of Christ) and Francesco at the end with Paul’s blood and a literal piece of his body held in his hands the same way.

And then there is like, the suspense of watching everyone marking time through the steps of this community ritual that’s supposed to be a joyful, communal celebration, while we know that there is a secret ticking away under the surface. The slow unfolding of the lie told to one person spreading to everyone in the village, and then the knowledge that Salvatore knows spreading to all the people who’ll be in trouble for that. The relationship arcs between the main Calabrian characters...not resolving, but sliding into place for the final act. Primo finally being done with Salvatore. Primo and Leo’s alliance being cemented and Leo physically stepping between Primo and Salvatore, to protect Primo. (No one ever protects Primo!! Still not over it!!!!) The confirmation celebration as a mirror of the Getty party in episode 1, the parallels drawn between the 3 Pauls and Salvatore-Primo-Francesco and how Primo reacts to being passed over as heir vs. how Paul Jr. reacts. Little Paul having two whole minutes of screen time and managing to break your heart with them. Regina! Just...Regina’s whole everything. The music going all-instrumental for an episode and having this haunting, dreamlike but still tense quality to it. And the fact that we never cut away from Calabria to another plotline gives the whole episode this hypnotic, all-encompassing quality. It’s just. SO GOOD!!!!

#fadagaski#asks answered#trust fx#long post#so so long omg#i can't believe how long i spent writing this but HERE IT IS#trust alternate watch order

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

The History & Evolution of Home Invasion Horror

Here’s my prediction: In the next couple of years, we’re going to be seeing a sudden surge of home invasion movies hit the market. For many of us, 2020 has been a year of extreme stress compounded by social isolation; venturing outside means being exposed to a deadly plague, after all.

And while many people have already predicted that we’ll see an influx of pandemic and virus horrors (see my post on those: https://ko-fi.com/post/Pandemic-and-Pandemonium-Sickness-in-Horror-T6T21I201), I actually think a lot of us are going to be processing a different type of fear -- anxiety about what happens when your home, which is supposed to be a literal safe space, gets invaded. Because if you’re not safe in your own house...you’re not safe anywhere.

Home invasion movies have been around a long time -- arguably as long as film, with 1909′s The Lonely Villa setting down the formula -- and they share many of the same roots as slasher films in the 1970s. But somewhere along the way, they separated off and became their own distinct subgenre with specific tropes, and it’s that separation and the stories that followed it that I want to focus on.

The Origins of the Home Invasion Movie

In order to really qualify as a home invasion movie, a film has to meet a few requirements:

The action must be contained entirely (or almost entirely) to a single location, usually a private residence (ie, the home)

The perpetrator(s) must be humans, not supernatural entities (no ghosts, zombies, or vampires -- that’s a different set of tropes!)

In most cases, the horror builds during a long siege between the invader and the home-dweller, including scenes of torture, capture, escape, traps, and so forth.

To an extent, home invasion movies are truth in television. Although home invasions are relatively rare, and most break-ins occur when a family is away (the usual goal being to steal things, not torture and kill people), criminals do sometimes break into people’s homes, and homeowners are sometimes killed by them.

In the 1960s and 70s, this certainly would have been at the forefront of people’s minds. Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood detailed one such crime in lavish detail, and the account was soon turned into a film. Serial killers like the Boston Strangler, BTK Killer and the “Vampire of Sacramento” Richard Chase also made headlines for their murders, which often occurred inside the victim’s home. (Chase, famously, considered unlocked doors to be an invitation, which is one great reason to lock your doors).

By the 1960s and 70s, too, people were more and more often beginning to live in cities and larger neighborhoods where they did not know their neighbors. Anxieties about being surrounded by strangers (and, let’s face it, racial anxieties rooted in newly-mixed, de-segregated neighborhoods) undoubtedly fueled fears about home invasion.

Early Roots of the Home Invasion Genre

Home invasion plays a part in several crime thrillers and horror films in the 1950s and 60s, including Alfred Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder in 1954, but it’s more of a plot point than a genre. In these films, home invasion is a means to an end rather than a goal unto itself.

We see some early hints of the home invasion formula show up in Wes Craven’s Last House on the Left in 1972. The film depicts a group of murderous thugs who, after torturing and killing two girls, seek refuge in the victim’s home and plot the deaths of the rest of the family. In 1974, the formula is refined with Bob Clark’s Black Christmas, which shows the one-by-one murder of members of a sorority house and chilling phone calls that come from inside the home.

Even closer still is I Spit on Your Grave, directed by Meir Zarchi in 1978. Although it’s generally (and rightly) classified as a rape-revenge film, the first half of the movie -- where an author goes to a remote cabin and is targeted and brutally assaulted by a group of men -- hits all the same story beats as the modern home invasion story: isolation, mundane evil, acts of random violence, and protracted torture.

Slumber Party Massacre, directed by Amy Holden Jones in 1982, also hits on both home invasion and slasher tropes. Although it is primarily a straightforward slasher featuring an escaped killer systematically killing teenagers (with a decidedly phallic weapon), the film also shows its victims teaming up and fighting back -- weaponizing their home against the killer. This becomes an important part of the genre in later years!

In 1997, Funny Games, directed by Michael Haneke, provides a brutal but self-aware look at the genre. Created primarily as a condemnation of violent media, the film nevertheless succeeds as an unironic addition to the home invasion canon -- from its vulnerable, suffering family to the excruciating tension of its plot to the nihilistic, motive-free criminality of its villains, it may actually be the purest example of the home invasion movie.

Home Invasions Gone Wrong

Where things start to get interesting for the home invasion genre is 1991′s The People Under the Stairs, another Wes Craven film. Here the script is flipped: The hero is the would-be robber, breaking and entering into the home of some greedy rich landlords. But this plan swiftly goes sideways when the homeowners turn out to be even worse people than they’d first let on.

This is, as far as I can tell, the origin of the home-invasion-gone-wrong subgenre, which has gained immense popularity recently -- due, perhaps, to a growing awareness of systemic issues, a differing view of poverty, and a viewership sympathetic to the plight of down-on-their-luck criminals discovering that rich homeowners are, indeed, very bad people.

Home Invasion Film Explosion of the 2000s

The home invasion genre really hit the ground running in the 2000s, due perhaps to post-911 anxieties about being attacked on our home turf (and increasing economic uneasiness in a recession-afflicted economy and a growing awareness of the Occupy movement and wealth inequality). We see a whole slew of these films crop up, each bringing a slightly different twist to the formula.

* It’s also worth noting that the 2000s saw remakes of many well-known films in the genre, including Funny Games and Last House on the Left.

In 2008, Bryan Bertino directed The Strangers, a straightforward home invasion involving one traumatized couple and three masked villains. By this point, we’re wholly removed from the early crime movie roots; these are not people breaking in for financial gain. Like the killers in Funny Games, the masked strangers lack motive and even identity; they are simply a force of evil, chaotic and senseless.

The themes of “violence as a senseless, awful thing” are driven further home by Martyrs, another 2008 release, this one from French director Pascal Laugier. A revenge story turned into a home-invasion-gone-wrong, the film is noteworthy for its brutality and blunt nihilism.

2009′s The Collector, directed by Marcus Dunstan, is another home-invasion-gone-wrong movie. Like Martyrs, it dovetails with the torture porn genre (another popular staple of the 2000s), but it has a lot more fun with it. The film follows a down-on-his-luck thief who breaks into a house only to encounter another home invader set on murdering the family that lives there. The cat-and-mouse games between the two -- which involve numerous traps and convoluted schemes -- are fun to watch (if you like blood and guts).

In a similar vein, we see You’re Next in 2013, which starts off as a standard home invasion movie but takes a sharp twist when it’s revealed that one of the victims isn’t nearly as helpless as she appears. Director Adam Wingard helps to redefine the concept of “final girl” in this move in a way that has carried forward right into the next decade with no sign of stopping.

2013 of course also introduced us to The Purge, a horror franchise created by James DeMonaco. If there was ever any doubt as to the economic anxieties at the root of the genre, they should be alleviated now -- The Purge is such a well-known franchise at this point that the term has entered our pop culture lexicon as a shorthand for revolution.

Don’t Breathe, directed be Fede Alvarez in 2016, is one of the creepiest modern entries into the “failed home invasion” category, and one that (ha ha) breathed some new life into the genre. Much like The People Under the Stairs, it tells the story of some down-on-their-luck criminals getting in over their heads when they target the wrong man. However, there is not the same overt criticism of wealth inequality in this film; it’s a movie more interested in examining and inverting genre tropes than treading new thematic ground. The same is true of Hush that same year. Directed by Mike Flanagan, the film is most noteworthy for its deaf protagonist.

But lest you start to think the home invasion genre had lost its thematic relevance, 2019 arrived with two hard-hitting, thoughtful films that dip their toes in these tropes: Jordan Peele’s Us and Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, which both tackle themes of privilege in light of home invasion (albeit a nontraditional structure in Parasite -- its inclusion here is admittedly a bit of a stretch, but I think it falls so closely in the tradition of The People Under the Stairs that it deserves a spot on this list).

What Does the Future Hold?

I’m no oracle, so I can’t say for certain where the future of the home invasion genre might lead. But I do think we’re going to start seeing more of them in the next few years as a bunch of creative folks start working through our collective trauma.

Income inequality, racial inequality, political unrest and systemic issues are all at the forefront of our minds (not to mention a deadly virus), and those themes are ripe for the picking in horror.

I know that Paul Tremblay’s novel The Cabin at the End of the World has been optioned for film, so we might be seeing that soon -- and if so, it might just usher in a fresh wave of apocalypse-flavored home invasion stories.

Like my content? You can support more of it by dropping me some money in my tip jar: https://www.ko-fi.com/post/Home-Invasion-Stories-A-History-R6R72RV7Y

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rey as a Palpatine and Why it’s Grown on Me

Hello my lovelies!

I think it’s been quite a while since I posted any kind of essay on here. Between work and other things I honestly haven’t had much time for it. However in recent days I’ve felt very motivated to work on a very particular kind of essay; a subject that I’ve been stewing over since December of last year.

Obviously from the title you already know what I’m going to be talking about. I’m not going to deny that this is a rather heated subject for some Star Wars fans, particularly those who disliked this plot choice and The Rise of Skywalker in general. As per usual in my essays, my goal is not to change anyone’s mind or argue over who’s opinion is “more right”. Plain and simple, this is just going to be me talking about MY thoughts and MY observations about Rey’s journey and lineage in The Rise of Skywalker. I hope this doesn’t need to be said but if you read something in this essay that you disagree with, I politely ask that you keep it to yourself and move on. At the end of the day, we are just talking about a movie, and this is all just for fun.

Now, with that being said, let’s get started! This essay is definitely going to be a bit more structured than my usual efforts and I hope this will result in a much more straightforward and clear-cut essay. Enjoy!

1. My Initial Reaction

While I don’t want this to be a major part of the essay, I do think it makes sense to start this off with a little story about the time I first saw TROS in the theatre. I can remember it pretty well. My whole body was tense, my eyes glued to the screen for what I knew was about to be some kind of major reveal in the story (even if it felt very late in the film for such a scene). Then came those shocking and irreversible words from Kylo Ren: “You’re his Granddaughter. You are a Palpatine.”

Wait…what?

My mind recoiled at this statement. My heart sank into my stomach with complete rejection. This can’t be right. He must be lying. I don’t like it. I don’t like it one bit. A man behind me just snorted with laughter and I can totally see why. Rey being related to Palpatine sounds more like a crazy Youtube fan theory than something that could actually be canon in the Star Wars universe. We had always thought she might be related to Luke or even Obi-Wan, but…Emperor Palpatine? Darth Sidious? No, just no.

So yeah, suffice to say that my first reaction towards this plot twist was not very positive. I admit that even once the movie was over, I still didn’t like this reveal. I don’t even think I began to warm up to it until my 3rd or 4th viewing of TROS. I had become so used to the idea that Rey had no special lineage and she was just a very force-sensitive girl from nowhere that it was extremely hard to let go of that. And honestly, if JJ and everyone else involved had chosen to keep it that way, I would have been perfectly content. So why…you might ask, has Rey’s true lineage grown on me in the last several months?

Now, don’t get me wrong…there’s still a part of me that thinks it was a very odd choice to introduce a reveal like this considering what happened in the previous installment. However…this fact has already been discussed to death and this essay is intended to be more of a story exploration rather than a critical film review. So let’s talk more about Rey being Palpatine’s Granddaughter and how I have actually grown to love the idea.

2. Rey’s Journey

Throughout the trilogy, Rey has had to overcome quite a few challenges in her path to becoming a Jedi. Her journey has been one of mostly self-discovery and personal growth. In The Force Awakens, Rey discovers that she is strong in the force and can do things she never imagined. In The Last Jedi, Rey’s strength in the force grows stronger and she learns to accept that her parents were nobodies and that some things do not turn out the way we expect.

And so, thematically, it would almost seem like Rey has reached the end of her character arc. This is Rey at her most powerful. There’s nothing left to learn, and there are no more secrets to be revealed…right? Well, we know that this is not the case. Even from the first scene with Rey we know that something is wrong. She knows that something is wrong. There is a darkness inside of her; she fears for her destiny and who she is meant to become. It’s not until later that we understand why these feelings have come to the surface.

Up until TROS, we didn’t truly know who Rey was or where she came from. However, by this point in the story anyone should be able to describe her as a character. Kind. Brave. Resourceful. Curious. Compassionate. Strong. Rey has proven time and time again that she is an incredibly kind and capable individual who wants to do the right thing. Although both TLJ and TROS strongly hint towards Rey possibly turning to the dark side, we know that our protagonist never actually would because we know who Rey is.

And this a huge reason as to why the Rey Palpatine reveal works so well for me. There is an incredible juxtaposition with Rey being the most heroic, kind-hearted person imaginable, and yet she is related to the most evil man in the galaxy. There is something deeply profound about the last living Jedi having Sith blood in her veins. Part of the reason why this reveal is so shocking is because the two characters are complete polar opposites in terms of good and evil. Rey is absolutely nothing like Palpatine and so the familial connection seems impossible. It doesn’t just seem like an unlikely truth, it feels entirely incorrect. And yet, that is also what makes it (again, in my opinion) so interesting and bold.

3. Meaning and Impact

Apart from giving Rey one last emotional challenge in the final installment, I think this choice was made for other reasons as well (3 to be precise).

1. It made Rey even more similar to Kylo as he too is grappling with the dark influence from his Grandfather

2. This decision subverts a long-existing trope in fantasy stories

3. Used to further tie the 9 films together as a story about the Skywalker and Palpatine bloodlines

Since The Force Awakens, it was made very clear early on that Rey and Kylo were connected in some way; their destinies were intertwined. Although this was further explored in TLJ, we would not truly understand just how similar their journeys would become until the final installment. The dynamic between Rey and Kylo is infinitely interesting because at first glance they seem like completely opposite people, when in reality they share a very similar struggle, especially in The Rise of Skywalker.

Both Rey and Kylo experience the overwhelming darkness of their respective families. Kylo even says it quite bluntly before the lightsaber duel on the ruined Death Star: “The dark side is in our nature, surrender to it.” He is quite obviously trying to use Rey’s lineage against her in an attempt to turn her over to his side. What makes this so interesting is that we know Kylo himself is not yet completely taken over by the dark side. Despite his evil deeds, he has always been conflicted during this story.

When Rey finds out that she is related to Emperor Palpatine, she becomes withdrawn, angry, afraid and unstable. This is the closest to the dark side that we have ever seen Rey at. Indeed there are some moments where she almost seems to be channeling behaviour that would be more suited for Kylo (snapping at her friends, using anger as power). Although Rey eventually comes to her senses and realizes what is happening to her, she was clearly affected by her Grandfather’s dark influence, just as Kylo was.

Despite the fact that both Rey and Kylo come from families with a history of the dark side, the film makes it very clear that one character’s lineage is far “worse” than the other. This is where the subversion of a common fantasy trope takes place. Now, to be clear, this is only my interpretation and I don’t claim this to be exactly what the filmmakers were going for; however this subversion is yet another reason why I enjoy the Rey Palpatine reveal.

How many times have you watched a movie or a TV show where a character’s lineage was a significant part of the story? It’s probably more times than you can count on one hand, right? My point is that the idea of a character’s lineage/family history becoming a main plot element in a story is nothing new, we’ve seen this before a million times. For example, in Disney’s “Tangled” (2010) Rapunzel learns that she is the long lost princess who was taken away from her family when she was an infant. Disney influence aside, does this sound somewhat similar to Rey’s story? Yes, it absolutely does…but not in the traditional or conventional sense.

This is where Rey Palpatine (for me at least), becomes extremely appealing. This reveal is like the evil, twisted version of a heroine discovering that she is the secret heir to a royal family. And instead of the protagonist being overjoyed and enlightened by this information, the reveal comes with great personal shock and emotional turmoil. In this case, Rey is the Granddaughter of Emperor Palpatine, which essentially makes her Sith royalty if we’re being really comparable. Am I the only one who (for lack of better words) thinks this is insanely cool? Not only is it a direct subversion of a very common story trope, it directly ties into Kylo’s arc and it also parallels Luke’s family revelation in “The Empire Strikes Back.” Coincidentally, this also makes Rey’s journey similar to Luke’s in that regard, but I’ll get back to that later.

Now as you’ve probably heard before, as we look back on all 9 films in the Star Wars saga we can see that this is clearly a story about the Skywalker and Palpatine families. Granted, the Palpatine bloodline is largely unexplored in comparison to the former. We know that Rey’s Father was the son of the Emperor, but we still don’t know his name or who he really was. Ultimately this information is not relevant to the story as a whole, but it’s clear that Emperor Palpatine has been pulling the strings throughout basically the entire saga.

More specifically, Palpatine himself has always been tied to the Skywalkers. He seduced Anakin Skywalker to the dark side and later tried to do the same to Luke. Via Snoke he was also able to turn Ben Solo, who shares a dyad with Rey, Palpatine’s Granddaughter. It kind of comes full circle and it’s really quite clever in my opinion. The Villain of the ST is related to the Heroes of the OT, and the Hero of the ST is related to the Villain of the OT (Did I just blow your mind?).

Put simply, Rey being a Palpatine makes a lot more sense thematically when you examine the story that came before her. Families are complicated and messy, especially in Star Wars. Rey’s experience echoes this, but in a much darker and harsher way. Her journey is meant to resemble Luke Skywalker’s in many ways, but their stories do have differences. In Luke’s case, he actually got to see and interact with Anakin, the real face of who his Father was. Anakin Skywalker was certainly not a perfect person, but in his last moments he turned to the light and saved his son’s life.

Rey, of course, did not get to experience a moment even close to this. Palpatine is about as evil as evil gets. There is no hope or chance of redemption. She was forced to look upon her own flesh and blood and see nothing but a monster. It would be unfair to turn this into a competition of “who had the most devastating family reveal”, but the point I’m trying to make is that Rey and Luke’s journeys are undeniably similar, which serves to further strengthen the connection of Skywalker and Palpatine in these 9 films.

4. Conclusion: The Power of Choice

I feel I must end on the note of choice, because this is how The Rise of Skywalker chooses to end. Despite everything I have mentioned and how much I have grown to love the idea of Rey Palpatine, there is something that I love much more than this: Rey Skywalker. Even just reading it or saying it out loud fills with me an indescribable amount of joy.

To put it bluntly, Rey did not have an easy life. In fact, she probably had one of the most challenging upbringings of any Star Wars protagonist. Yes, Anakin was a slave at a very young age, but he also had friends and a mother who supported him. Luke was even better off with a relatively normal childhood, friends and parental figures who loved him as if he was their own son.

Rey had nothing and no one.