#this is what studying mesopotamia is like too

Note

What is your opinion on the article "Mesopotamian or Iranian? A New Investigation on the Origin of the Goddess Anāhitā" by Alireza Qaderi?

He proposes that Anahita is possibly the syncretism of an Iranian Water goddess with Annunitum, and while it largely makes a lot of sense to me, especially with how it points out that we can't treat the Avesta as we know it as identical to the Avesta in Zarathustra's time,

it also assumes the Central Asian goddess Ardokhsho comes from Aredvi Sura instead of Arti, and everything else I've seen just says Ardokhsho comes from Arti, although I haven't seen much literature on either deity tbh

Sorry it took me a few days to answer this ask even though it’s basically laser focused on my interests. I had some other stuff to read and unpleasant work duties to perform and couldn’t properly go through the recommended paper.

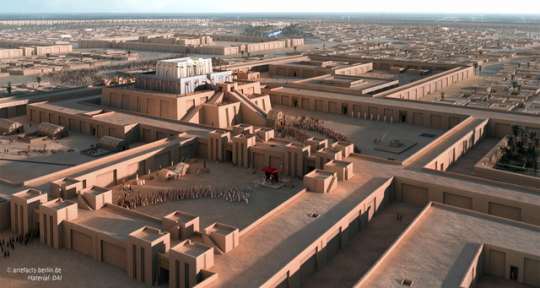

My feelings about the paper are mixed. I think anyone who remembers Annunitum was a distinct deity as early as in the late third millennium BCE deserves at least some credit. The notion of interchangeability of goddesses still haunts the field, fueled by Bible scholars, Helsinki hyperdiffusionists and the like. Overall the author shines in the sections dedicated only to the evaluation of the broadly Iranian material, but as soon as the focus switches to Mesopotamia things fall apart, sadly.

More under the cut. Hope you don’t mind that I’ll also use this as an opportunity to talk about Annunitum in Sippar in general. I've been gathering sources to improve her wiki article further (don’t expect that any time soon though).

The Iranian material

Criticizing the vintage attempts at equating Anahita with Sarasvati is sound and sensible. Same with stressing that she is distinct from Nanaya and Oxus. The criticism of theories depending on lack of familiarity with the historical range of the beaver was a nice touch too, it demonstrates well that the author wanted to cover as much previous literature as possible. However, I also have no clue what’s up with “ΑΡΔΟΧΡΟ has an ambiguous relationship with Arədvī Sūrā”, I’ve also only ever seen this name explained as a derivative of Ashi/Arti save for a single paper trying to force a link to Oxus which was met with critical responses. It’s entirely possible this is an argument I simply haven’t seen though, I’m also not really familiar with this matter.

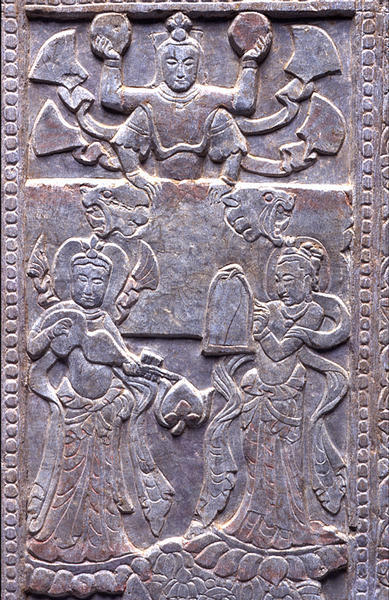

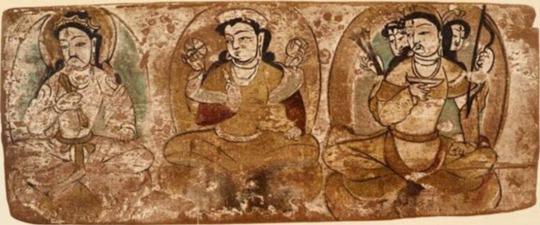

Overall the arguments against seeking Anahita’s origin in the east are perfectly sensible, and line up with the evidence well - no issues at all with this part of the paper. Following a more detailed list of Anahita’s easter attestations from Shenkar’s Intangible spirits and graven images. She appears on some Kushano-Sasanian coins, but this seems to reflect importing her from the west relatively late on since she appears in neither Kushan nor Bactrian sources. The coins are even exclusively inscribed in Middle Persian, with no trace of the local vernacular.

For unclear reasons Anahita caught on to a degree even further east in Sogdia, but attestations are limited to the period between fourth and sixth centuries. Since they’re largely just generic theophoric names, it is hard to call her anything but a minor deity of indeterminate character in this context, though. I’ve seen the argument that the popularity of Oxus in the east might have been the obstacle to introducing her. Oxus was a bigger deal in Bactria than in Sogdia so it could even explain why Sogdians were slightly more keen on her, arguably, even if they and Bactrians came into contact with her cult under similar circumstances.

Back to the article, the section dealing with the western attestations starts on a pretty strong note too. The need for reevaluation if it’s fair to talk about Achaemenid rulers as “Zoroastrian” is a mainstay of studies published over the past 10-15 years or so. I can’t weigh on the linguistic arguments because I know next to nothing about that.

I’m not sure if I follow the argument that it makes no sense Iranian population wouldn’t need a royal order to start worshipping a new deity as long as they were Iranian, tbh - linguistic or cultural affiliation doesn’t come prepackaged with automatically updated list of deities one is obliged to instantly adopt as soon as they pop up into existence. Following this logic, why didn’t Sargon’s Akkadian speaking subjects in Syria just adopt Ilaba before being obliged to do so? You will find literally hundreds of cases like this, it’s a very weird argument to me.

The Mesopotamian material

The biggest problems start once the coverage of Mesopotamia begins. The rigor evident in the strictly Iranian sections of the article just… vanishes and it’s incredibly weird.

Herodotus as a source is… quite something. The phrase “ a goddess with a Semitic character” is… well, quite something too (Reallexikon generally advises against defining anything but languages as “Semitic” in Mesopotamian context - Mesopotamian is a perfectly fine label to use, and accounts for the fact that Sumerian, Hurrian and Kassite are not a part of the Semitic language family). It keeps repeating later and admittedly I’m not very fond of this. Especially when it pertains to the west of Iran, where deities originating in Mesopotamia were worshiped since the late third millennium BCE - they were more Elamite than Mesopotamian by the time Persians showed up, really. The matter is covered in detail in Wouter Henkelman’s Other Gods who Are with Adad in the Persepolis Fortification Archive as a case study.

Cybele was by no means Mesopotamian (with each new study she keeps becoming more strictly Phrygian, with earlier Anatolian, let alone Mesopotamian, influence becoming less and less likely) so I'm not sure what she's doing here, Nanaya’s associations with lions is almost definitely an Iranian innovation and not attested before the late first millennium BCE; despite earlier sound arguments against ascribing strictly Avestan Zoroastrian sensibilities to people in the late first millennium BCE, that’s basically what happens here. Lions were evidently viewed favorably by at least some Persians and especially Bactrians and Sogdians.

The less said about the part trying to link evidence from Palmyra to Inanna and Dumuzi (what does a marginal spouse deity like Dumuzi, entirely absent from Palmyra, have to do with Sabazius, a veritable pantheon head equated with Zeus?), the better. Frazerian bit, if I have to be honest.

I’m not sure about the enthusiasm for Boyce’s argument that it makes little sense for Anahita to simultaneously be a river goddess and to bestow victory in battle. The latter characteristic lines up well with her elevation to the position of a deity tied to investiture of kings, which in turn is something which boils down to personal preference of a given dynasty. The character of deities isn’t necessarily supposed to be one-dimensional and having distinct spheres of activity because of historical factors is hardly unusual.

Stressing that it’s not possible to treat Anahita and Ishtar as interchangeable is commendable. However, I don’t think it’s possible to claim continuity between the religious beliefs reflected in the relief of Anubanini and first millennium BCE Media. The argument is not pursued further, to be fair, but it’s still weird.

The next huge issue is the treatment of the late “Anu theology”. A good recent overview of this matter can be found in Krul’s 2018 monograph (shared by the author herself here).

For starters, it’s completely baffling to declare Anu had no spouse at first; Urash and Ki are both attested in the Early Dynastic period already - and the former appears reasonably commonly in this role in literary texts and god lists. Even Antu might already be present in the Abu Salabikh list.

Attributing Inanna prominence in Uruk and in the Eanna in particular to identification with Antu is utterly nightmarish and one of the worst Inanna takes I’ve ever seen; the fact it’s contradicted by information of the same page makes it pretty funny, admittedly. Inanna’s ties to the city go back literally to the beginning of recorded history (some of the oldest texts in the world are demands aimed at cities under the control of Uruk to provide offerings for Inanna ffs), and probably even further back. Meanwhile, Anu for most of his history was an abstract hardly worshiped deity; Krul stresses this in the beginning of her book linked above. I’m not a fan of ancient matriarchy takes which are often lurking in the background when the cases of earliest city goddesses like Inanna, Nisaba and Nanshe are discussed but I do think the need to downplay Inanna’s prominence and elevate Anu which pops up every few years in scholarship is suspect and probably motivated by sexism, consciously or not, tbh.

Trying to make the “Anu theology” which developed in the late first millennium BCE an influence on the entirety of Mesopotamia and beyond is puzzling. Sabazius appearing in Palmyra with a spouse is tied to Anu, somehow? The fact that deities had spouses is? Atargatis ties into this somehow? I’m sorry, but I’m not following. Also, Uruk was no longer a theological center of the Mesopotamian world in the first millennium BCE. Babylon was, and before that Nippur. There is no need to speculate, there are thousands of texts to back it up. The late sources from Uruk in particular show that Babylon was somewhat forcefully influencing the city, not the other way around.

The Anu theology was a display of local “nationalism” of Uruk and had a very limited impact. There is evidence for some degree of late theological cooperation between Uruk and Nippur, and possibly Der as well (Der itself despite being located with certainty has yet to be excavated, though, so caution is necessary), but nothing of this sort is to be found in the late sources from other locations.

Annunitum = Anahita?

Finally, let’s look at the core idea behind the article.

Right off the bat I feel it’s necessary to stress Annunitum generally wasn’t regarded as an astral deity. In the Old Babylonian period, the Venus role was evidently handled by Ninsianna in Sippar; later on they aren’t even attested there but the regular Ishtar is. Seems doubtful it would actually be Annunitum who got to be an astral deity there at any point in time.

This claim is also highly dubious. There is no evidence that Antu was ever worshiped in Sippar, let alone that she was equated there with Annunitum; she doesn’t show up at all in Jennie Myers’ 2002 thesis The Sippar pantheon: a diachronic study. Paul-Alain Beaulieu stresses her lack of importance all across Mesopotamia save for first millennium BCE Uruk here. There is also no evidence that the late Anu theology impacted Sippar in any capacity. Shamash retained his position in the city until the death of cuneiform. Even in Uruk, Annunitum in the late sources appears only in association with Ishtar and Nanaya, not Anu and Antu. I will repeat how I feel about the need to assert Anu’s importance where there is no trace of it.

Overall it feels like unrelated Mesopotamian and adjacent sources from different areas and time periods are used indiscriminately; which is ironically the criticism employed in the article wrt the treatment of Iranian textual sources by other researchers.

The Assyriological sources employed leave a bit to be desired, too. In particular Abusch’s Ishtar entry in the Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible is a nightmare (he’s good when he covers incantations but his broader “theological” proposals are… quite something), here are some quotes from it to show how awful it is is a central point of reference:

Of the other authors cited, Jacobsen is Jacobsen and a lot changed since the 1960s. Roberts was criticized right after his study was published by researchers like Aage Westenholz. Langdon’s study from the early 1900s is an outdated nightmare, I guess we know what’s up with the Dumuzi hot takes now. Beaulieu is great but his papers and monographs aren’t really utilized to any meaningful extent, I feel.

Other criticisms aside, I’m unsure if Annunitum was important enough in the fifth century BCE to be noticed by Artaxerxes II as postulated here, especially since Shamash was right next door and definitely retained some degree of prominence. Most if not all cases of Mesopotamian deities influencing Persian or broader Iranian tradition reflect widespread cults of popular deities - Nanaya, Nabu (via influence on Tishtrya), Nergal (in the west, around Harran) - as opposed to a b-list strictly local deity. And it’s really hard to refer to Annunitum differently. Let’s take a quick look at her position in the twin cities of Sippar - as far as I am aware, the most recent treatment of this matter is still Myers’ thesis, and that’s what I will rely on here.

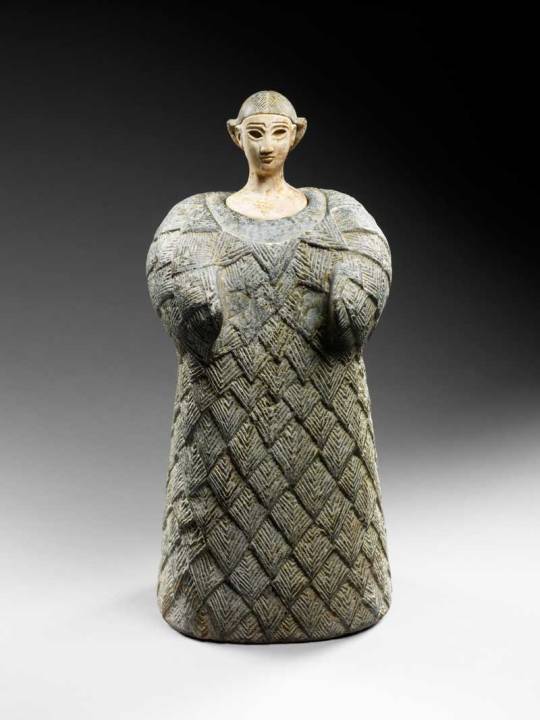

Annunitum is first attested in Sippar in the Old Babylonian period, during the reign of Sabium, though as a deity already locally major enough to appear in an oath formula alongside Shamash. In the Early Dynastic period Sippar-Amnanum was likely associated with an enigmatic figure designated by the logogram ÉREN+X who doesn’t seem to be related to her. When and how exactly the tutelary deity change occurred is not presently possible to determine and admittedly of no real relevance here.

Evidently Annunitum’s cult in Sippar was influenced to some degree by the Sargonic tradition she originated in, her temple was even called Eulmaš just like that in Akkad. It’s not impossible it was even originally founded by one of the members of the Sargonic dynasty, but in absence of pre-OB evidence caution is necessary. There is no shortage of later rulers who wanted to partake in the Sargonic legacy, after all. By the earliest documented times, it was the second most important temple in the Sippar agglomeration, and the only one beside the Ebabbar to have its own administrative structure.

Annunitum was even referred to as the “queen of Sippar” (Šarrat Sippar; note that by the Neo-Babylonian period this title came to function as a distinct goddess, though). In Sippar-Amnanum there was a street, a gate and a canal named after her. A bit over 6% of the inhabitants of both cities bore theophoric names invoking her, also.

Sippar-Amnanum was abandoned for some 200 years after the reign of Ammi-saduqa, but it seems the clergy simply moved to the other Sippar next door. Next few centuries are very sparsely documented at this site, but supposedly Shagarakti-Shuriash rebuilt Annunitum’s temple (the matter is discussed in detail here).

Inscriptions of Tiglath-pileser I dealing with the conquest of northern Babylonia affirm that Annunitum continued to be viewed as the goddess of Sippar through the Neo-Assyrian period. According to an inscription of Nabonidus her temple, and Sippar-Amnanum as a whole, were razed by Sennacherib (he also blames “Gutians” for it though by then this is a label as generic as “barbarian”). This might be why her cult had to be relocated to the other part of Sippar again. In the Neo-Babylonian period it returned to Sippar-Amnanum under Neriglissar, though her temple was only rebuilt by Nabonidus. It survived at least until the reign of Darius, though it was only a small sanctuary (É.KUR.RA.MEŠ) like those of Adad and Gula.

There is very little evidence for popular worship of her so late on: only two theophoric names have been identified…. For comparison, Shamash appears in 208 (out of 823 theophoric names, out of a total of 1243 total). Nergal, Gula, Adad and even Amurru are all more common. Aya is also absent, but unlike Annunitum despite her prominence in earlier periods she was actually never common in theophoric names, save for the names of naditu; and naditu ceased to be a thing after the OB period.

Offering lists complicate the matter further. From the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, Annunitum started to lose ground to a duo introduced from Dur-Kurigalzu: a manifestation of Nanaya associated with this city and Ishtar-tashme. Why they suddenly appeared in Sippar and why they overshadowed Annunitum is uncertain, perhaps Dur-Kurigalzu just failed to recover from decline after the end of the Kassite period and eventually the decision was made to start transferring local deities to other nearby major urban centers. The process reversed during the reign of Nabonidus, who ordered an increase in offerings made to her. This might’ve been motivated by his general concern for Sin and any deities considered members of his immediate family - essentially, a display of personal devotion. This elevation is still evident in offering lists from the reign of Cyrus, though.

Overall the paper is quite convincing - outstanding, even - when it comes to the Iranian material alone, and between mediocre and nightmarish once the author shifts to Mesopotamia.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

DC x DP prompt/ficlet

Throwing my hat in the ring with this idea that has been doing the zoomies in my brain for days. The Tim/Danny Accidental Ghost Marriage to Fake Dating to Friends to Lovers AU:

Pariah Dark was a piece of shit. Before his imprisonment, mortals would sometimes manage to bargain with the Ghost King for scraps of power. One of the "standard" deals was to send PD a "Bride" to play with and feed on (because I HC he feeds on fear and pain) and what better way than a little mortal battery that couldn't get away from him? The deal was sealed with a cursed amulet. Now in one instance, the contract was never fulfilled (maybe the petitioner died before he could complete his half) and the amulet was lost. After Pariah was imprisoned and couldn't make deals anymore the knowledge of the rituals needed was gradually forgotten since they didn't work anymore...

Eventually the amulet gets dug up by archeologists (maybe in Egypt or Mesopotamia?) and ends up in a traveling exhibit in Gotham. A Rogue robs the place (Riddler? Two-Face? doesn't really matter). When the Bats show up to foil the robbery, during the fight with the goons a drop of Red Robin's blood gets on the amulet, there's a blinding flash of green light and the amulet is suddenly glued to him.

While everyone is dazed by the ghostly magic flashbang, Fright Knight pops out of a portal, yoinks Red Robin across his saddle and jumps back through the portal before anyone can stop him. Cue the Bats trying to frantically figure out what in the multi-dimensional occult hell happened and where RR went?!

Meanwhile, Danny is disturbed to receive a ghostly missive in his college dorm to tell him that his Mail Order Bride has been delivered to his Ghost Zone Palace and is awaiting him so they can consummate their Unholy Matrimony.

----------------

Danny: Wtf I have to study I don't have time to get MARRIED

Fright Knight: I'm sorry my liege, but according to the laws of ghosts, gods and magic you already ARE

Danny: Wtf. How did this happen?

RR: I would like to know that too

Danny: Oh shit, you're a superhero. Frighty, you can't just kidnap people! Especially not SUPERHEROES!

RR: While that's good to hear, I would really like to know about this supposed marriage..?

FK: I am not aware of the exact details, I was merely summoned to retrieve the Bride of the Ghost King. There used to be standard magical contracts for this, which went into effect when the Bride bled on the King's Token...

RR: Shit

Danny: Hold on, PARIAH got married? Multiple times??

FK: ...but we can always consult the Royal Archivist, if we can dig him out from under the several thousand years worth of paperwork that piled up while there was no King actively ruling...

Danny: Oh ancients, am I gonna have to deal with that?? I have exams to prepare for, dude!

RR: ...the dead still have to do exams? And paperwork?? *horror*

-------------

Some time and explanations later...

Royal Archivist: It took some digging, but I believe I have found the contract in question. You are one Timothy Drake-Wayne, correct?

Tim: Fml

RA: Ahem. The contract was sealed with your mortal blood, as is standard procedure. Congratulations, you are officially King-Consort of the Infinite Realms! Until death do you part, and all that

Danny: Can I see that contract? ...This isn't in English

RA: Oh dear, looks like we will have to schedule your Royal Highness classes in reading cuneiform/hieroglyphics

Tim: Okay, does it say anywhere in that contract how to dissolve it? What's the procedure for a ghost divorce? Fright Knight mentioned the previous king being married multiple times

RA: Well usually, when Pariah tired of a consort he would simply devour their soul...

Danny: Ewwwww I am so not doing that

Tim: I concur. I can't imagine my soul would taste good anyway

Danny: That's what you took from that??

RA: ...but when you die and your soul passes into the Afterlife proper, the contract will be fulfilled. As long as you're not resurrected again.

Tim: Nuts, there goes that loophole

RA: Until then you are the Consort and duty-bound to fulfill his Royal Highness' every whim; ghostly, spiritual, carnal...

Danny: *sinks through the floor in embarrassment*

Tim: Can't he just... release me from the contract? Take the amulet off me or something?

RA: Not without obliterating your soul, no

Danny and Tim: Fuck

--------------

Some time later, while Danny is away consulting other ghosts on possible ways of dissolving the contract, they discover the nasty little clause that if Tim isn't in regular physical contact with Danny the amulet starts draining his life force. To prevent victims from escaping you see... Danny really really hates Pariah right now.

They eventually return to the mortal plane to explain to the Batfam what the hell is going on and that they're still trying to fix it. In the meantime, Danny can't miss any more classes (studying areospace engineering at MIT or sth) and Tim has to stick close to him because of the curse...

Alfred: Oh dear, looks like Master Timothy will have to go to college after all *unflappable British Smugness*

Bruce pulls a lot of strings to fast track Tim getting his high school diploma and let him attend classes with Danny (he's not officially enrolled yet, but Money, Dear Boy). They never know when Danny has to respond to a ghost emergency or Red Robin to a Bat emergency, so they stay pretty much joined at the hip in their civilian lives. Of course there's gonna be rumors. Why did the Wayne CEO suddenly drop everything to go to college? So they make up a story about Danny and Tim having been secret boyfriends for a while and Tim becoming so smitten that he moves with him to Boston...

Cue the fake dates, interviews with magazines, couple photoshoots to really sell the bit... and the two young men gradually becoming friends... and then "Feelings?? But what do I do?? He was forced into this?" etc.

#dcxdp#dpxdc#dp x dc#dc x dp#dc x dp crossover#dc x dp prompt#danny phantom#tim drake#red robin#danny fenton#ficlet#batman#batfam#accidental marriage#arranged marriage

948 notes

·

View notes

Text

outfit control ↪ leon s. kennedy

DI!Leon / fem!reader

age gap implied, power dynamics at play, soft dom leon

mdni - 18+

First of all, this man is not doing a 24/7 dynamic. He doesn’t mind playing, and he doesn’t mind power dynamics outside the bedroom from time to time, but he is so goddamn tired. He cannot be responsible for your every action. He’s going to snap if he has to micromanage you. He requires a firm ‘scene start’ and ‘scene end’.

Look me in my eyes and tell me where Leon ‘You’re Pulling Me Off Furlough Again?’ Scott Kennedy has found the time to be an experienced dominant.

Dude spent years unable to form lasting relationships. He’s got experience, but he’s rarely had the chance to cultivate anything close to a dynamic with someone.

So, yeah, not exactly ‘World’s No. 1 Dom’. He’s doing his best out here, and his best is fumbling and awkward and endearing.

Sex? No prob.

Communicating openly about his wants and desires? Hm. Perhaps a slight prob.

He wasn’t even sure he was going to like having all the control that you wanted to give him.

However.

If there’s one thing about Leon, it’s that he’s gonna study. He’s gonna learn the ins and outs, and he’s going to improve. Dude likes to learn. He goes down rabbit holes all the time. If you look through his bookmarks, half of it is just wikipedia articles he hasn’t finished reading yet. When you ask him to try this with you, it’s like you’re handing him homework. He takes this shit seriously.

He’s not gonna ask you about what you want, he’s going to go on a several hour long deep dive.

He’s holed up in his office in the late hours of the night, scouring the internet and leaving behind a very incriminating search history. You don’t even know how many burner accounts this guy has. Ever since you showed him the power of adding ‘reddit’ to the end of a google search, he’s been unstoppable.

(“Did you know that the origins of BDSM date back to Mesopotamia.” “Leon, it’s four in the morning. Please just come to bed.”)

He eased you into it, more for his sake than for yours. Straight up picking out your outfits was a little much for him, especially if you were actually planning on leaving the house that day. It’s not a humiliation thing for him, it’s more the thrill of control and seeing you all dressed up like he wants.

So he starts small. Picks out your jewelry, asks you to wear your hair a certain way, things that are somewhat innocuous in his mind.

Once he gets comfortable with that, he asks you to select a couple outfits for him to pick from. Send him a picture of you wearing the outfit he picked, he’s gonna be thinking about it all day long.

Sometimes he’ll pick out every piece of your outfit himself, but he still has you pick out options for him to choose pretty often. He knows your wardrobe pretty well by this point, and he puts together surprisingly competent outfits that you never would have paired yourself.

He’ll put together an outfit for you and sometimes there’s just? A new dress? New panties? You have never seen these before. He denies buying them for you, insists that you just have too many clothes to know what you have in your closet. He delights in spoiling you, and even more in surprising you with clothes like this.

This is absolutely not an everyday thing. (Again, see above – too busy. Would explode if he had to take full responsibility for your well-being.) He’s only just starting to take care of himself, don’t make him try to take care of you, too.

Gets legitimately pouty if you don’t wear what he picked out for you. God help you if you changed clothes without asking him.

Wanna see a grown man mope around? Wear a different shirt.

His idea of a punishment is a funishment. Good luck getting him to actually punish you. He’d much rather overstimulate you until you’re crying, your hand fisted tight in his hair, pleading for him.

Highkey wants you to pick his clothes out too. He’s not going to tell you this. You’ll have to read his mind.

You picked out his tie for him exactly one time and he’s been riding that high ever since. He would much rather try to trick you into picking things out for him.

(“Can you grab my tie for me?” “Sure, which one?” “...Oh, y’know.”)

It’s like pulling teeth to get this guy to tell you what he wants in this regard, I’m so serious.

Also he’d love to coordinate outfits, especially for special occasions. He’s not into matching, but he loves to have a theme, something that unifies the both of you. If it’s subtle and it signifies the two of you as together without screaming it to the world, then he absolutely adores it.

"Excuse me."

Your step pauses. Leon's practically pouting from his seat on the couch, arms folded over his broad chest.

“What?” You ask, smothering a smile.

“I don’t think that’s what I set out for you.”

He taps his thigh, waving for you to come over to him. You gravitate towards him and stop short. You know damn well that he wants you to sit on his lap. You give a little spin instead, showing off the outfit you had selected. His brow furrows, his forehead creasing at your brazen display.

“You don’t like it?” You ask, innocently enough.

Leon scoffs. His hand encircles your wrist, tugging you closer.

“I didn’t say that,” he says, urging you to his lap. This time, you relent. “You look very nice. But that’s not what I set out for you, is it?”

You shrug. Play dumb. He can’t prove shit. “Your memory must be going, old man.”

Leon tuts, tugging at a lock of your hair. His hand splays over your thigh, warm and encompassing. To his credit, he keeps his eyes on yours, not on the enticing expanse of skin that’s been bared to him so readily.

“Pretty sure the dress I picked out for you was longer than this. You trying to tell me something?”

“I plead the fifth.”

“I guess we’ll take it to a jury of your peers, then.”

#leon kennedy x reader#leon kennedy x you#leon kennedy imagine#leon kennedy headcanons#resident evil x reader#resident evil#leon kennedy#hi my name's delphi and i like kink negotiation more than actual kink sometimes

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

2024 Book Review #4 – War in Human Civilization by Azar Gat

This is my first big history book of the year, and one I’ve been rather looking forward to getting to for some time now. Its claimed subject matter – the whole scope of war and violent conflict across the history of humanity – is ambitious enough to be intriguing, and it was cited and recommended by Bret Devereaux, whose writing I’m generally a huge fan of. Of course, he recommended The Bright Ages too, and that was one of my worst reads of last year – apparently something I should have learned my lesson from. This is, bluntly, not a good book – the first half is bad but at least interesting, while the remainder is only really worth reading as a time capsule of early 2000s academic writing and hegemonic politics.

The book purports to be a survey of warfare from the evolution of homo sapiens sapiens through to the (then) present, drawing together studies from several different fields to draw new conclusions and a novel synthesis that none of the authors being drawn from had ever had the context to see – which in retrospect really should have been a big enough collection of dramatically waving red flags to make me put it down then and there. It starts with a lengthy consideration of conflict in humanity’s ‘evolutionary state of nature’ – the long myriads between the evolution of the modern species and the neolithic revolution – which he holds is the environment where the habits, drives and instincts of ‘human nature’ were set and have yet to significantly diverge from. He does this by comparing conflict in other social megafauna (mostly but not entirely primates), archaeology, and analogizing from the anthropological accounts we have of fairly isolated/’untainted’ hunter gatherers in the historical record.

From there, he goes on through the different stages of human development – he takes a bit of pain at one point to disavow believing in ‘stagism’ or modernization theory, but then he discusses things entirely in terms of ‘relative time’ and makes the idea that Haida in 17th century PNW North America are pretty much comparable to pre-agriculture inhabitants of Mesopotamia, so I’m not entirely sure what he’s actually trying to disavow – and how warfare evolved in each. His central thesis is that the fundamental causes of war are essentially the same as they were for hunter-gatherer bands on the savanna, only appearing to have changed because of how they have been warped and filtered by cultural and technological evolution. This is followed with a lengthy discussion of the 19th and 20th centuries that mostly boils down to trying to defend that contention and to argue that, contrary to what the world wars would have you believe, modernity is in fact significantly more peaceful than any epoch to precede it. The book then concludes with a discussion of terrorism and WMDs that mostly serves to remind you it was written right after 9/11.

So, lets start with the good. The book’s discussion of rates of violence in the random grab-bag of premodern societies used as case studies and the archaeological evidence gathered makes a very convincing case that murder and war are hardly specific ills of civilization, and that per capita feuds and raids in non-state societies were as- or more- deadly than interstate warfare averaged out over similar periods of time (though Gat gets clumsy and takes the point rather too far at times). The description of different systems of warfare that ten to reoccur across history in similar social and technological conditions is likewise very interesting and analytically useful, even if you’re skeptical of his causal explanations for why.

If you’re interested in academic inside baseball, a fairly large chunk of the book is also just shadowboxing against unnamed interlocutors and advancing bold positions like ‘engaging in warfare can absolutely be a rational choice that does you and yours significant good, for example Genghis Khan-’, an argument which there are apparently people on the other side of.

Of course all that value requires taking Gat at his word, which leads to the book’s largest and most overwhelming problem – he’s sloppy. Reading through the book, you notice all manner of little incidental facts he’s gotten wrong or oversimplified to the point where it’s basically the same thing – my favourites are listing early modern Poland as a coherent national state, and characterizing US interventions in early 20th century Central America as attempts to impose democracy. To a degree, this is probably inevitable in a book with such a massive subject matter, but the number I (a total amateur with an undergraduate education) noticed on a casual read - and more damningly the fact that every one of them made things easier or simpler for him to fit within his thesis - means that I really can’t be sure how much to trust anything he writes.

I mentioned above that I got this off a recommendation from Bret Devereaux’s blog. Specifically, I got it from his series on the ‘Fremen Mirage’ – his term for the enduring cultural trope about the military supremacy of hard, deprived and abusive societies. Which honestly makes it really funny that this entire book indulges in that very same trope continuously. There are whole chapters devoted to thesis that ‘primitive’ and ‘barbarian’ societies possess superior military ferocity and fighting spirit to more civilized and ‘domesticated’ ones, and how this is one of the great engines of history up to the turn of the modern age. It’s not even argued for, really, just taken as a given and then used to expand on his general theories.

Speaking of – it is absolutely core to the book’s thesis that war (and interpersonal violence generally) are driven by (fundamentally) either material or reproductive concerns. ‘Reproductive’ here meaning ‘allowing men to secure access to women’, with an accompanying chapter-length aside about how war is a (possibly the most) fundamentally male activity, and any female contributions to it across the span of history are so marginal as to not require explanation or analysis in his comprehensive survey. Women thus appear purely as objects – things to be fought over and fucked – with the closest to any individual or collective agency on their part shown is a consideration that maybe the sexual revolution made western society less violent because it gave young men a way to get laid besides marriage or rape.

Speaking of – as the book moves forward in time, it goes from being deeply flawed but interesting to just, total dreck (though this also might just me being a bit more familiar with what Gat’s talking about in these sections). Given the Orientalism that just about suffuses the book it’s not, exactly, surprising that Gat takes so much more care to characterize the Soviet Union as especially brutal and inhumane that he does Nazi Germany but it is, at least, interesting. And even the section of World War 2 is more worthwhile than the chapters on decolonization and democratic peace theory that follow it.

Fundamentally this is just a book better consumed secondhand, I think – there are some interesting points, but they do not come anywhere near justifying slogging through the whole thing.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

random ducktales headcanons in whatever order I think of them

Louie likes math. He acts like he doesn’t because he thinks it’s dumb and nerdy, but he likes math.

In a human AU, Huey would wear cargo pants, track pants, or jeans on occasions. Dewey is a jeans every day type-of-guy, he doesn’t own any pants besides jeans. Louie always wears sweatpants or track pants.

Researching Scrooge really got Webby into American history. She loves learning about Scrooge when he was in America. Some of her favorite periods to learn about; The Gold Rush, the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, primarily the early Gilded Age.

As Dewey gets older, he gets a passion for writing. His overactive imagination is a tool for this. He also uses inspiration from his childhood fantasies and incorporates them into his stories. For example, he makes references only he would get about Dewey High in his writing. He does primarily action/adventure and realistic fiction.

Louie gets easily embarrassed about his hobbies. He starts by doing them nonchalantly, but when he realizes people are noticing, he starts doing them in secret.

Huey does not get art, primarily poetry, plays, or anything written. It just goes right over his head. He hates English class and Shakespeare.

When Lena likes something, she draws it a lot. Whether it be her magic, people, friendship bracelets, or even just a little trinket she found, she’ll draw it. These drawings go into her most beloved sketchbooks. But she also has the Sketchbook of No Return, in which she draws things she hates as a way of getting her emotions out. Sometimes she even blacks out the page after drawing it.

Violet introduces Webby to Ancient Civilizations. They study early history together, from Mesopotamia to India to Greece.

Huey and Violet get competitive when they do Junior Woodchuck things, but they get along really well otherwise. They both have passions for science and nature.

Boyd and Huey are best friends, and hang out all the time. Despite being a robot, like all Gearloose’s inventions Boyd feels human emotions. Huey finds this extremely fascinating. Louie likes to tease Huey about being friends with a robot, but Louie doesn’t really have many friends himself so he can’t say much.

Gosalyn feels awkward at the huge sleepovers the Duck and Vanderquack family are always hosting. Her only friend at them is Dewey, while everyone else knows each other. Even Boyd knows Lena and Violet. Plus, Gosalyn doesn’t even know the rest of the Duck boys. But, eventually she warms up to everyone after being super competitive in games and sort of cold as a defense mechanism.

Lena and Violet dye their hair together sometimes.

Panchito and José eventually become known as Uncle Panchito and Uncle José.

Huey, being terrified of Dewey’s carelessness, finds Louie to be his Comfort Sibling™

Louie is kind-of into knitting???

Fethry, Gladstone, Donald, and Della always came to Scrooges for the Holidays. Every Holiday. Winter and Spring break too. They all got pretty close. Plus, adventuring was not Donald and Della exclusive.

Donald is the only one who can tell the triplets apart when they do their hair the same way and wear the same clothes.

One time Louie stole Webby's skirt because he wanted to know what it was like to wear one. He's also done this with Scrooge's clothes.

Dewey cannot cook for the life of him, but Huey is a master chef. Huey also makes the best soup-and-salad combos. Louie is in the middle ground, but for some reason finds baking much easier.

One time Della, Donald, Fethry and Gladstone played War together, but on teams. Donald and Gladstone wanted to see whose luck would outweigh the others, so they teamed up. The game was cut short because the table got knocked over and the cards fell through the floorboards. They looked for the cards but couldn’t find them.

May loves drawing and June loves reading, and they like to write books together. Daisy gives May fashion tips for her characters, and reads the books June recommends.

Webby likes to photobomb Dewey's selfies.

Gosalyn and Louie scam people together.

Webby and Lena have a playlist of both their favorite songs. They sing to all of them at their one-on-one sleepovers.

Lena and Violet both like heavy metal.

Gosalyn was extremely girly as a child.

Lena reminds Scrooge of Donald when he was younger.

Drake adopted Gosalyn (obviously).

Lena and Huey lowkey have beef.

Dewey was actually laid first.

One time Dewey accidentally called Storkules his Uncle Storkules. The man was never happier.

Panchito became a sky pirate once but Don Karnage booted him.

Boyd really likes listening to Huey talk about his passions, which is good since Huey goes on and on about them. Donald thinks it's so sweet that Huey has such a good friend. Boyd is Donald's favorite of all of the boys' friends.

Louie's khopesh is his favorite treasure ever.

Della was Donald's best man at his and Daisy's wedding. It didn't matter that she wasn't a man.

Launchpad and Drake nerd out together for at least three hours a week.

Drake cannot handle affection. He gets all awkward when someone tells him they love him or when someone hugs him.

When Louie isn't around, Boyd is the number two comfort buddy for Huey.

Violet and Boyd get along really well, and Huey gets jealous of Violet. But they primarily hang out in JW meetings so it isn't crazy.

#ducktales#ducktales 2017#headcanons#ducktales headcanon#ducktales 2017 headcanon#Huey Duck#Dewey Duck#Louie Duck#Webby Vanderquack#donald duck#Della Duck#Scrooge McDuck#Lena Sabrewing#Lena De Spell#Violet Sabrewing#Boyd#B.O.Y.D.#Gosalyn#Ducktales Gosalyn#gosalyn mallard#gosalyn waddlemeyer#the three cabarellos#panchito x josé#Fethry#Cousin Fethry#Gladstone#Gladstone Gander#May Duck#June Duck#may and june duck

303 notes

·

View notes

Text

I like the idea of Vio adopting some Gerudo traditions as a way of mourning Shadow and coping with his loss.

I base a lot of my Gerudo culture headcanons on ancient Egypt, even though my specialty is Mesopotamia and “ancient Egypt” is about as vague as saying “yeah I have a mammal in my house”. The time frame we’re looking at- ancient Egypt is so vast that actual ancient Egyptians had their own archaeologists studying their own past. So. Read my uncited and sleep-deprived fandom post with that in mind, and maybe go look up Hathor’s significance as a goddess of both mining and makeup, or the origin of the dog star. People seem to think Egypt was all about death.

Still, I’m here for goth blorbo posting, so talk of death it is!

For my personal headcanons, and Hyrule Historia’s debatable take on Shadow being made from Ganondorf AND Link- I think he was both an attempt at mocking Link, but also possibly an attempt to create a Gerudo hero. It must sting that not only can Ganondorf never win, but even his people suffer the short end of the stick. I’ll leave Shadow’s creation and the motives behind it up in the air, but- I do like the idea of him being somewhat racially Gerudo, if not raised in it culturally. Shadow is alone, running on emotions and instincts that might be his and might be the old hate of an endlessly reincarnated demon. His brain keeps spitting up random facts about the divine ritual significance of the king, flooding season and how to respectfully summon ghosts, and he has no idea what to do with any of this.

Until, of course, one day he brings home a cute nerdy twink to the evil castle and Shadow wants this guy’s attention So Bad. Cue poorly planned and half-understood infodumping that still earns him Vio’s complete undivided attention and possibly even cuddles. We don’t know what they were doing while Blue and Red tried not to die. Maybe they painted eachother’s nails while Shadow awkwardly coughed up random facts about Gerudo noun modifiers. (It would work on me)

Let’s fast forward.

Shadow is, for all intents and purposes, very dead by the end of things. While I love the idea of Vio descending into the guts of occult research hell to bring him back, there’s time between the end of the adventure and when- or even if- his attempts work. Research is one coping mechanism. How else does he want to remember Shadow?

Shadow wanted to be a person, above all else. Real, someone to be looked in the eye and respected. Nobody else is going to mourn him- who else would have cared enough, known him enough? The other parts of Link might try to understand for Vio’s sake, but they didn’t live it. They didn’t drink with him and toss around awful villain greetings like “vile morning your wretchedness”. The only people who don’t get graves or rites or anything are��� well, being deliberately treated as less than people. And even if Shadow was a magic construct made of half a dozen things and the kitchen sink, enough of him was Gerudo for him to cling to it and say this, this is evidence that I’m a person too.

Something about the practice of religion that might not be immediately apparent to the average white American Protestant or culturally Christian atheist is that orthopraxy and orthodoxy are two different things. Correct action versus correct belief, essentially. In the ancient world, it often didn’t matter if you “believed” in a god, especially if you were in a high political position- the motions still had to be performed. It was taken as a matter of fact that the ghosts needed to be given bread and the rash on your neck was a sign of a god’s displeasure that could be interpreted via medical divination.

I’m vastly simplifying it because this is a fandom post and I’m running on two hours of sleep, so I’ll cut to the chase- it doesn’t matter if Vio “follows” the goddess of the sands or any other deity, or even none at all. If he thinks Shadow would have wanted beer and bread left out for his ghost, according to how any real person would be honored, I don’t think it’s out of the question that he might just do that. Plus, I think Vio would be invested enough in how Shadow would want his memory to be treated that he’d do the reading and maybe hop over to the Desert of Doubt to ask the Gerudo for proper funerary details in person. Again, it’s not like Shadow would have any other family or friends to fill the role.

Vio absolutely has a little sketch of Shadow in his room with a glass of water and a little plate next to it, and when Blue leaves a giant platter of stress-baked cookies outside his door he shares them with his dead boyfriend. I’m just saying. The guy may be dead but the love is not.

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I have a humble ask for you if you have a bit of time to indulge me. While I understand from your name that your interest is primarily in the late republic, I was wondering if you had any recommendations for me regarding a slightly later period:

I’ll be taking a class on the Roman Empire and its emperors (+Julius probably) next semester. I’ve got more of a background in Classical Greek history than Roman, so I’m a bit out of my depth. I did a brief survey of some of the early big names in high school (mostly I just remember J Seas, October August, Capri Pants Tibby, Little Booties, Neckbeard Zero, and Ostrich Boy, though I’m sure we covered others), but I was wondering if you had any recommendations for interesting figures in and around the imperial court at really any time during the centuries of Roman Empire to look out for and/or stan in the coming year. I tend to find that being able to latch on to interesting people with lots of personality or story about them makes it easier to study the surrounding events, so I’m hoping for some help from fellow tumblr nerds to get a head start on that. Thank you for reading (and perhaps replying)!

Welcome, dear reader! It sounds like you're in the market for a blorbo...or perhaps a punching bag!

You already know the Julio-Claudian Clusterfuck, so I'll skip them. (I recommend all of them though!) If you enjoyed their family drama, you'll find even more of it in the Severan dynasty. Starting with Rome's first African-born emperor, through his fratricidal sons, to Elagabalus - who might've been what we now call transgender, but it's hard to tell. These folks make the Julio-Claudians look stable.

Or maybe you'd prefer a more relatable guy like Marcus Aurelius. He's one of the few emperors whose inner personality we can really see, thanks to his diary surviving and getting renamed the Meditations. I think many people struggling with depression, anxiety or existential dread might find a lot in common with Marcus' writings. He was a good guy who tried his best, despite never wanting to be emperor and facing horrible luck. His predecessor Antoninus Pius was also a very cool dude, the kind who did good quietly and resolved issues with diplomacy instead of war. They're two of the few emperors I think were actually good people.

If military history's your thing, you can't go wrong with Trajan, Aurelian or Constantine. Trajan conquered Dacia and Mesopotamia, making the empire bigger than ever. Aurelian's superb leadership and character helped to end a 40-year civil war. People seem to either love Constantine or hate him. He was also the first Christian emperor, and played a huge role in shaping Christianity as an institution and orthodox set of beliefs. Whether that was good for Christianity is a question in itself...Constantine's family had tons of drama, too!

If you'd rather pray to Jupiter than Jesus, you'll probably like Julian, Rome's last pagan emperor and a Huge Fucking Nerd. He's a favorite of alternate history buffs for what paganism and Christianity might've turned into if he lived longer. Also, he wrote satirical fanfiction about other emperors for fun!

Vespasian, Titus and Hadrian are interesting if you're into Jewish history. Well, "interesting" in a bad way...You can blame the first two for the destruction of the Second Temple, and Hadrian for the atrocities of the Bar Kokhba revolt. I liked reading Flavius Josephus' account of the first Jewish revolt, which characterizes Vespasian, Titus and Herod (that Herod) quite vividly. It's a very bloody tragedy, and all the trigger warnings apply, but it really brings this time period to life. (Get an edition with a Jewish translator, if possible - older Christian-led translations tend to shove antisemitic junk in there.)

Titus was the emperor when Mt. Vesuvius erupted, so the ruins of Pompeii and Pliny the Elder's wacky Natural History date to Titus' time. Some people really connect with Hadrian's famous gay love affair with Antinous, and he was an incredibly well-traveled man who left monuments like Hadrian's Wall all over the empire...but his genocide in Judea overshadows everything else for me.

But hey, maybe you're fascinated by the awful ones. Or maybe you think some emperors have been misunderstood. There's been a lot of discussion in recent years over whether Tiberius, Nero, Domitian and Commodus were as bad as they're usually portrayed. I'm only really acquainted with Tiberius. In his case, I found not a monster, just a deeply troubled man who'd been put into the worst job possible against his will.

I don't know many imperial women, but I gotta give shout-outs to Livia, Julia the Elder, Agrippina the Elder and Younger, Empress Theodora (wife of Justinian), and Empress Irene (whom Charlemagne wanted to marry!).

Readers, feel free to chime in with your favorite emperors, empresses and court-adjacent Romans! The wilder the stories, the better!

#just roman asks#local-queer-classicist#roman emperors#suetonius is also a lot of fun for reading about the first twelve emperors#even if he's blatantly wrong sometimes. especially when he's wrong#A+ source of imperial gossip#genocide mention#jlrrt essays

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Good evening, Dr. Reames

I wanted to ask you something, a long time ago I read that during the XIX century there was a lot of discussion about the veracity of the figure of Alexander, like: Did he really exist or is he a legendary character?

What do you think about it? Thank you very much, I love your work very much.

Did Alexander the Great Actually Exist?

Skepticism about historical figures was part of a larger development in the discipline of history: the critical evaluation of our sources.

“Historiography,” or the history of history. Instead of just taking sources at face value, historians began to interrogate them: who wrote it, when, and what was that person’s perspective?

These are just the most basic questions. As time progressed, historiography became ever more refined. I’ve discussed some of these refinements before in my longer posts here. For instance, the difficulty in untangling imperial Roman tropes/themes overlying anecdotes about Alexander. We work for awareness of layering, narrative context, big-picture themes….

Yet sometimes the pendulum swings too far, at least IMO. Scholarly trends can get out of hand. Shiny new toys (ideas) are fun, but must be woven into the larger scholarly conversation, not suck all the air out of the room. History has fads just like anything else—including undue skepticism. Some things I warn my own students about:

Smoke does not always equal fire. That is, don’t assume the negative report is true over a neutral or positive one; especially the latter can be denigrated as whitewashing. Fact is, people love dirt and lie about or exaggerate bad things just as much as they polish up events or a person’s image.

Things can be exaggerated rather than invented out of whole cloth. Without solid evidence to support pure invention, I’ll tend to assume exaggeration. Layers of “truth” exist. It gets tricky.

Back to historiographic development….

The Enlightenment led to the questioning of much received truth. That’s the era of Darwin, of historical Biblical criticism, Reason over Faith, the birth of archaeology, etc. As part of the critical evaluation of ancient sources, scholars began to doubt the existence of heroes such as Agamemnon, Achilles, Theseus, and events too, such as the Trojan War. In fact, all events in Greek myth/history before 776 BCE—the date of the first Olympics—were regarded as fictional. As archaeology took over Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Italy, Greece was fighting for freedom from Ottoman control, archaeology new there—bronze-age Greece yet uncovered.

In any case, as part of the new en vogue skepticism, some scholars questioned not only heroes and myths, but historical figures too, especially those further back in time. Did Solon exist? Cyrus? Croesus? Or even … Jesus? (Radical!)

Proposing Alexander as mythical falls into that same hyper-skeptical period. The fact all our biographies were written so long after he lived made it easier to hypothesize he was a myth!

Yet recall… archaeology was new, epigraphy (study of stone inscriptions) just starting. A lot of information we have now simply didn’t exist at that time.

Today, trying to argue that Alexander wasn’t real is ridiculous. We have coins minted in his reign, epigraphical evidence from his own day naming him, oodles and oodles of images, archaeological evidence from Macedonia itself, etc. There’s no question Alexander of Macedon existed, and he conquered a hella lot of his known world. The basic outlines of his campaign are documented in hard evidence.

We can, however, (and should!) question many of the stories and anecdotes about his campaign. Even the outlines of some battles. Two mutually-exclusive versions of the Battle of Granikos exist. Some famous events probably didn’t happen at all (the whole proskynesis affair). Others didn’t happen as they’re told. After all, we have competing stories in the original sources themselves—take the Gordion Knot episode. That’s where we apply our critical historiographic eye now.

But to return to our story of burgeoning historiography in the 19th and early 20th centuries….

In 1870, Heinrich Schliemann began to dig at Troy, which opened up the Greek bronze age and put a hard skid on the “it’s all fiction” trend. Now, that shithead Schliemann did boatloads of damage and has earned his rep as a lying little Colonialist weasel who’s roundly cursed by most modern archaeologists. But you gotta give him that small sliver: he reversed the trend that regarded Greek myth as entirely false.

Then the pendulum swung the other way. If the Trojan War had really happened, was myth just barnacle-encrusted history? That notion wasn’t so different from what the ancients had believed about their own myths, in fact.

Many historians sought to “purify” myth: find the truth behind it. The trend remained popular well into the 20th century in both academic history as well as historical fiction (see Mary Renault’s The King Must Die and Bull from the Sea). It also encouraged periodic “searches” for mythical places. The seemingly never-ending “Search for Atlantis” is the most obvious example. (Newsflash: Plato made that shit up. It’s a philosophical metaphor, y’all.)

Today, most professional historians regard Greek heroes as fictional. Instead, we trace how myths and heroes morphed over time and across cultures. So, Greek Herakles translated into Etruscan Hercle, then into Roman Hercules, plus Greek Herakles’s probable antecedent in ancient near eastern myths of Gilgamesh, Marduk, Sampson, Melquart, etc.

We’re also interested in how myths/legends embed reality at the edges to make them realistic to their hearers. It’s not barnacle-encrusted history but may still convey reality…much as fiction does today. If you watch a TV show about, say, hospital emergency rooms, most people don’t assume the characters are actual doctors or the events real except in broad brushstrokes. Yet we do rate such shows for how well they approximate ER experience. World build. That’s how modern historians and Classicists tend to approach myths today.

Myths are the stories a culture tells itself about itself.

What a culture valued, emulated, and how it wanted to think about itself can be found in myths.

These are the same things reception studies consider, btw. They’re less about what actually happened in history, than what people later wanted to believe happened. That’s as interesting a question (to my mind) as the truth of the event itself.

So perhaps all those fads in history tell us as much about the historians who purvey them as what they were uncovering. 😉

#historiography#Alexander the Great#classics#tagamemnon#asks#birth of archaeology#myth as history#purpose of myth#skepticism in historical thought#did Alexander the Great exist?#ancient Greece#Greek history

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the topic of Speaking in tongues

When I had just found God I was in university in Scotland. I was on fire for God even though I really didn't know anything. I'm grateful God found me. I studied theology and met young people from all over the world and we formed a little community. We were from different denominations and from different backgrounds. Some of us came from very christian backgrounds, some of us were from less christian backgrounds. It was fun to discuss religion! And it was fun to pray with different people. Especially for me who had just found Christ.

...and that's when I found myself praying with a girl from Kazakhstan. She was very cool. Exmuslim, had found Christ and defied her parents. Very mentally strong. She had several bibles with passages highlighted and I could tell she was trying to teach me. It was nice. Until she took my hands, closed her eyes and started praying. It started normally with words in English. Then it switched over to nonsense words. She was from the pentecostal church. I found it very strange, I remember opening my eyes and just looking at her. After the praying was done, she told me that it was praying words you don't understand because it's a divine language. Me, who didnt know anything, thought she was right. So the following days I tried to pray like that. But my heart is too traditionally Lutheran to manage.

Now that I'm older and - God help me - wiser I no longer believe that talking in tongues the way that the pentecostal church does is a thing. Tongues means language, like English, Swedish, Arabic etc. If I can bring your attention to The Book of Acts chapter 2:

The Holy Spirit Comes at Pentecost

2 When the day of Pentecost came, they were all together in one place. 2 Suddenly a sound like the blowing of a violent wind came from heaven and filled the whole house where they were sitting. 3 They saw what seemed to be tongues of fire that separated and came to rest on each of them. 4 All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues[a] as the Spirit enabled them.

5 Now there were staying in Jerusalem God-fearing Jews from every nation under heaven. 6 When they heard this sound, a crowd came together in bewilderment, because each one heard their own language being spoken. 7 Utterly amazed, they asked: “Aren’t all these who are speaking Galileans? 8 Then how is it that each of us hears them in our native language?" 9 Parthians, Medes and Elamites; residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia,[b] 10 Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya near Cyrene; visitors from Rome 11 (both Jews and converts to Judaism); Cretans and Arabs—we hear them declaring the wonders of God in our own tongues!” 12 Amazed and perplexed, they asked one another, “What does this mean?”

Above it says that when The Holy Spirit entered them they started speaking in different tongues. At that time there were Jews from all over the world there and they understood what the apostles were saying. The human Jews understood what the early Christians were saying. If it had been words that no humans could understand it wouldn't have been so.

They even ask "Aren’t all these who are speaking Galileans? Then how is it that each of us hears them in our native language?" Which again they would only ask if they could understand what was being said.

It's a huge miracle that the Galileans could suddenly speak languages of the world that they had never spoken before! And that's that in my head.

...thanks for reading!

#jesus#christian#bible#christianity#christian living#bible quote#lgbt christian#jesus christ#queer christian#god#pentecostal#speaking in tongues

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

We Walk Into A Bar

so there's this post which talks about the earliest known example of a bar joke ("x walks into a bar and...") which no one knows or understands the punch line of, if it even has one, since it's a proverb.

it is followed up by selected screencaps of a (now deleted) thread wherein someone claims to have deciphered it all (with - also deleted - linguistic receipts) and figured out the pun.

with me so far?

okay let's go down a rabbit hole.

How We Found Out: https://www.tumblr.com/bending-sickle/723007901258711040

We Know Nothing: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bar_joke

“[Assyriologist Dr. Seraina] Nett suggests that the punchline could be a pun that is incomprehensible to modern readers, or a reference to some figure who was well known at the time but similarly unfamiliar to us today. Gonzalo Rubio, another Assyriologist, cautions that this ambiguity ultimately means it is simply not possible to definitely categorize the proverb as a joke, though he and other scholars like Nett do point to the recurring use of innuendo in such proverbs as indicating that many were indeed intended to be humorous.”

We Know Nothing, Part 2: Podcast Boogaloo

“What makes the world’s first bar joke funny? No one knows.” Endless Thread podcast, August 5, 2022 https://www.wbur.org/endlessthread/2022/08/05/sumerian-joke-one

Hosts: Amory Siverston & Ben Brock Johnson

Guests:

Dr. Seriana Nett (Assyriologist and researcher at the Department of Linguistics and Philology at Uppsala University, Sweden)

Dr. Gonzalo Rubio (Assyriologist and Associate Professor of Classics & Ancient Mediterranean Studies at Pennsylvania State University, USA)

Dr. Philip Jones (Associate Curator and Keeper of Collections of the Babylonian section at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, a.k.a. the Penn Museum, USA).

Excerpts:

Amory: Seraina Nett works at Uppsala University in Sweden, where she studies ancient Mesopotamia, including a region called Sumer and its language Sumerian. She spends a lot of time translating Sumerian, looking for clues about early human development.

[…]

Ben: Seraina was one of several thousands of people who happened upon this joke in March on Reddit and initially on Twitter.

Amory: That’s where the account @DepthsOfWiki posted a screenshot from an unlinked, unnamed Wikipedia page. It reads like this: “One of the earliest examples of bar jokes is Sumerian, and it features a dog.”

[…]

Amory: The humor of the dog-in-a-bar joke was probably related to those Sumerian ways of life, perhaps the middle class or well-off, people with downtime and drinking shekels.

Ben: But while some experts know some things about Sumer, the nuances have been lost, and it’s the nuances that bring jokes to life.

[…]

Seraina: It could have been a pun that we don’t understand. It could have been a reference, I don’t know, to a local politician or some famous figure. So it’s very hard for us to tell.

[…]

Seraina: This proverb is in no way special. It’s part of a larger collection of many, many, many proverbs.

Amory: The bar joke — or proverb — is Number 5.77 in a collection of hundreds of other proverbs about dogs, donkeys, husbands. Some read like sayings. Others like weird short stories. But jokes? Depends on how you see things. Like this other proverb Gonzalo told us:

Gonzalo: It’s something like, “Behold! Watch out! Something that has never occurred since time immemorial; the young woman did not fart in her husband’s lap.”

Ben: Sorry, I’m going to be really dumb for a second.

Amory: I am too because this is—

Ben: I’m not sure I get the joke. Is the joke that the woman would never admit that she farted in her husband’s lap? Or is the joke that the woman always farts in her husband’s lap? And that’s the joke, that we’re suggesting that it’s never happened before.

Gonzalo: I think the joke is precisely the latter. The joke is that it is expected to happen. To set up the joke by saying, “Watch out, this is something that has never happened, not once.” And then the sentence is, well, “The young woman did not fart in her husband’s lap.”

[…]

Seraina: There’s quite a lot of innuendo — things like sexuality or, I don’t know, excrement. For example, one of my favorite ones is, “A bull with diarrhea leaves a long trail.”

[…]

Gonzalo: The word for tavern, “ec-dam,” for us, it conveys the idea of a pub or a bar. But really, in ancient Mesopotamia, a tavern is also a place where sex trade takes place. So it’s a tavern, but you could also translate it as a brothel.

[…]

Seraina: It could have been the dog walks into the bar with his eyes closed; “Let me open this,” as in the eyes. Or open, I don’t know, a door. There is also a word that sounds very similar to one of the words that is a word for female genitalia.

[…]

Ben: There’s another complication, though, because it still doesn’t make sense. Or, at least, we’re not laughing. Plus, the translations are too loose and feel kind of unreliable. We mentioned this to Seraina, who dropped one more tantalizing clue about the clay tablet — or tablets that hold our proverb.

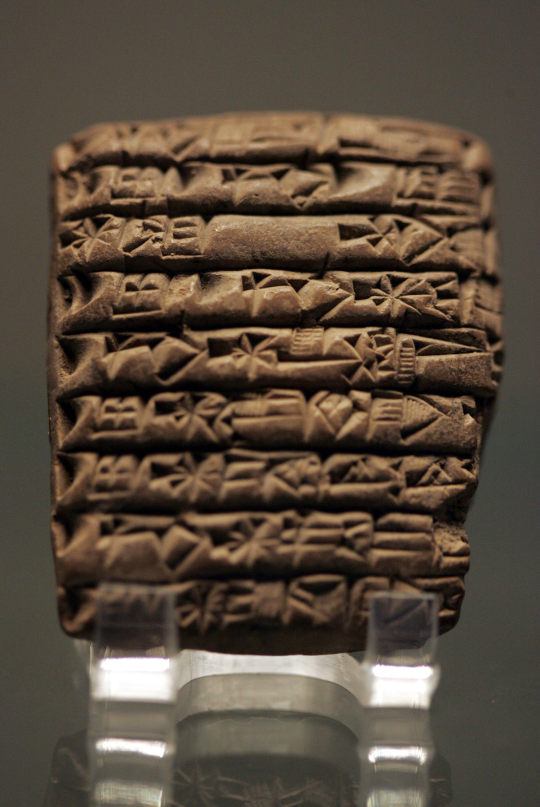

Seraina: So this particular proverb is attested on two different versions of the text. And actually, they’re not identical. So, already, somebody screwed up. One of them is also a little bit broken, so it’s hard to tell.

Amory: This thing that everyone’s struggling to understand: No fricken wonder! Because there are two copies. They’re actually both broken, and they don’t match.

[…]

Ben: These two ancient tablets, he tells us, were etched around 1700 B.C.E. At first, this means nothing to us, really, but Phil explains. By that time, Sumer had actually been overtaken by the Babylonian empire. The culture was pretty similar, except that the Sumerian language had already died out.

Amory: Kids at the time spoke Babylonian, also called Akkadian. Only scribes continued to learn Sumerian. It was considered more dignified — kind of like learning Latin today. Knowing this, it seems now even more likely to us that there are mistakes in the text. For instance:

[…]

Ben: Ignoring the random non-Sumerian word, the dog enters the taverny brothel or brothely tavern. He can’t see a thing. He opens this one. Only, Phil says the word “open” is very similar to the word for “close.”

Phil: I mean, not in this case. I think it obviously means to—. Well? It obviously means to open in this case because they do spell—

Amory: Are you sure?

Ben: Yeah, you sound unsure.

Phil: I think I’m fairly sure because normally, if they mean “to close,” they’ve ended up using a different spelling than this one.

[…]

Amory: But he [Phil] adds that everyone’s missing some very important context about the dog.

Phil: The dog is a specific character type. It’s a guard dog whose job is to keep the wolves from the sheep. And in the proverbs, you know, it’s operating on the basis that it’s a personality type that is fairly brutal and not really to be messed with.

Ben: Interesting. That puts like a whole ‘nother layer on this thing because I feel like I wasn’t making any assumptions about the dog other than its general doggyness.

[…]

Phil: I think usually in proverbs, when they say “this,” it refers to something you’ve already heard in the proverb, not to something new. So I think the idea that he’s opening rooms and revealing, you know, couples in flagrante doesn’t quite go with how I would see the word “this” functioning. So I did wonder whether this is more the idea that letting the guard in negates his use because, basically, he wants to see out, he’s going to open the door, and so everybody else outside the tavern can now see in. I mean, I think that’s a legitimate way of looking at it.

Ben: Phil covers the old clay. We wistfully shuffle out. And, at this moment, we buy his theory. A brothel’s guard dog is sitting outside the door under the bright Sumerian sun. He’s scaring away unwelcome Peeping Toms. But then he leaves his post.

Amory: He goes inside, and his eyes aren’t used to the dark, so he can’t see anything. He opens the front door again, propping it to let in a little light. Now, outside, all those Toms are looking in, seeing their politicians and neighbors in flagrante, as Phil said. The guard dog messed up. Get it?

Reddit Redux: User serainan (Seraina Nett) To The Rescue

1 - https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/tbgetc/this_bar_joke_from_ancient_sumer_has_been_making/

"We usually translate the word esh-dam as 'tavern'. Yes, they are associated with prostitution, but it is not primarily a brothel. There is eating and drinking and sex. So, the joke could be sexual, but doesn't necessarily have to be.

The verb ngal2--taka4 in its basic meaning means 'to open' without any sexual connotation. However, there's a noun gal4-la that sounds similar and means 'vulva', so there could be some double-entendre there...

Essentially, the interpretation of the proverb depends on the demonstrative 'ne-en' 'this' and what it refers to – grammatically, I'd agree with you and say it seems to refer to the eye, but there's really no way of knowing for sure.

The problem with jokes is really that they are so culture-specific. Maybe this joke makes fun of a local politician or it is using a very crude word that is not otherwise attested in our sources (written texts, particularly in ancient cultures, of course only cover a limited part of the vocabulary).

Bottom line: We don't get the joke! ;) ”

The Unknown and Deleted: A Story in Four Sources

1 - https://twitter.com/lmrwanda/status/1505648702119202823?t=IHkQWeElTa0T63o3lbr12Q&s=19

2 - https://twitter.com/lmrwanda/status/1505646738627088389?t=06aHTTZkf1ZaJyCDhWUzTg&s=19

3 - https://www.podchaser.com/podcasts/subversive-walex-kaschuta-1979505/episodes/lin-manuel-rwanda-the-twilight-158022618

4 - http://im1776.com/author/lin-manuel

There was one person on Twitter claiming the joke was, “A friendly dog walks into a bar. His eyes do not see anything. He should open them.” Or “He should crack one open.” (1) They add “It’s a ‘man walks into a bar and hurts his head’ tier dad joke, basically. The ‘pun’ in Sumerian is centered on the fact that the verb ‘to see’ also literally means ‘open (one’s) eye’.” This was at the end of a long word-by-word translation thread (which I can’t judge the quality of, and no other experts were chiming in) dated March 20, 2022 (2). I did not save the thread and Twitter is saying the page doesn’t exist anymore, so that’s a dead end now.

I hesitate to trust this source because I can’t find any of their qualifications (are they an assyriologist? A linguist? A candlestick maker?) and other experts in the field do not seem aware of this (if true) ground-breaking cracking of the highly-debated pun. (Dr. Seraina Nett’s gave an interview five months after this thread was made, and still called the actual pun a mystery.) I could only find out that their Twitter name is “Lin-Manuel Rwanda, @lmrwanda, Epistemic trespasser” and that, according to the podcast Subversive w/ Alex Kaschuta (December 14, 2022) (3), they are “a Twitter poster” with essays on the online magazine IM-1776, where they are credited as “Lin Manuel” (4). (Their introduction in the podcast also reveals they are a British national and resident, but the host is very coy about revealing even that. Lin Manuel corrects them, adding that they are “half Rwandan”, which explains the Twitter name. I am not listening to the whole hour and a half to look for more clues.)

#hey kids wanna learn about an obscure joke#you can see why i can't put this in a fanfic footnote#and putting it in an appendix is just...insane#anyway this has been eating my brain for a while#randomness#and now you know#a dog walks into a bar#linguistics

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The most important deity you've never heard of: the 3000 years long history of Nanaya

Being a major deity is not necessarily a guarantee of being remembered. Nanaya survived for longer than any other Mesopotamian deity, spread further away from her original home than any of her peers, and even briefly competed with both Buddha and Jesus for relevance. At the same time, even in scholarship she is often treated as unworthy of study. She has no popculture presence save for an atrocious, ill-informed SCP story which can’t get the most basic details right. Her claims to fame include starring in fairly explicit love poetry and appearing where nobody would expect her. Therefore, she is the ideal topic to discuss on this blog.

This is actually the longest article I published here, the culmination of over two years of research. By now, the overwhelming majority of Nanaya-related articles on wikipedia are my work, and what you can find under the cut is essentially a synthesis of what I have learned while getting there. I hope you will enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed working on it.

Under the cut, you will learn everything there is to know about Nanaya: her origin, character, connections with other Mesopotamian deities, her role in literature, her cult centers… Since her history does not end with cuneiform, naturally the later text corpora - Aramaic, Bactrian, Sogdian and even Chinese - are discussed too. The article concludes with a short explanation why I see the study of Nanaya as crucial.

Dubious origins and scribal wordplays: from na-na to Nanaya

Long ago Samuel Noah Kramer said that “history begins in Sumer”. While the core sentiment was not wrong in many regards, in this case it might actually begin in Akkad, specifically in Gasur, close to modern Kirkuk. The oldest possible attestation of Nanaya are personal names from this city with the element na-na, dated roughly to the reign of Naram-Sin of Akkad, so to around 2250 BCE. It’s not marked in the way names of deities in personal names would usually be, but this would not be an isolated case.

The evidence is ultimately mixed. On one hand, reduplicated names like Nana are not unusual in early Akkadian sources, and -ya can plausibly be explained as a hypocoristic suffix. On the other hand, there is not much evidence for Nanaya being worshiped specifically in the far northeast of Mesopotamia in other periods. Yet another issue is that there is seemingly no root nan- in Akkadian, at least in any attested words.

The main competing proposal is that Nanaya originally arose as a hypostasis of Inanna but eventually split off through metaphorical mitosis, like a few other goddesses did, for example Annunitum. This is not entirely implausible either, but ultimately direct evidence is lacking, and when Nanaya pops up for the first time in history she is clearly a distinct goddess.

There are a few other proposals regarding Nanaya’s origin, but they are considerably weaker. Elamite has the promising term nan, “day” or “morning”, but Nanaya is entirely absent from the Old Elamite sources you’d expect to find her in if Mesopotamians imported her from the east. Therefore, very few authors adhere to this view. The hypothesis that she was an Aramaic goddess in origin does not really work chronologically, since Aramaic is not attested in the third millennium BCE at all. The less said about attempts to connect her to anything “Proto-Indo-European”, the better.