#topoi

Text

Self pegging

Porn free gay guy male camp Jimmy sits down though and captures

Janessa Brazil Masturbating In Shiny Bikini On Webcam

grandpa fucks horny teen

Cumtribute rico

Dresden gets her warm mouth fucked by the LP Officers dominating man meat

Turkish bodybuilding man horny big cock

quick Nut fast in the shower

Sexy shemale dominates her guy by ass fucking him hard

Mi esposa mamando en el monte la verga a un amigo

#unsymptomatic#sumbulic#blind#augites#preenclosed#chansons#topoi#watchable#vaultedly#unexchangeabness#white-eye#subhastation#sensitization#cryptous#ACAS#Loralie#busboy's#protelytropteron#Basidiolichenes#assentatory

0 notes

Text

So does anyone want to read my essay about how Deeper Than The Holler by Randy Travis contains every popular Minnesang trope?😔

#deeper than the holler#randy travis#country#country music#minnesang#this is not a very popular intersection of literary analysis#but I would love to write about it I genuinely would#medieval literature#topoi

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cyberpunk and Neuromanticism, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr.

The Vampire in Science Fiction Film and Literature, Paul Meehan

#words#cyberpunk#horror#cyberpunk and neuromanticism#the vampire in science fiction film and literature#vampires#science fiction#scifi#something about the cyberpunk and horror genres borrowing each other's topoi#parallels#web weaving

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

One day my fellow historians will achieve their ultimate triumph and demonstrate that polytheism has never existed, we've all been transcendental monotheists forever and we still are actually (sorry neopagans :( )

#joke to be clear#i am neither academic-bashing nor neopagan-bashing#it's just quite funny to me how many different religions#and regions and areas#seem to become dramatically leas polytheist the more you read into the scholarship#pre-islamic arabia which all the islamic sources describe as being fully of pagans worshipping rocks and stones and all the usual topoi?#all evidence of polytheism there vanishes a century before muhammad was born#ancient greece? allow me to introduce you to the ambiguities of the singular usage of Ζεύς and stoic notions of a universal divine#the frontiers roll ever back :(

0 notes

Text

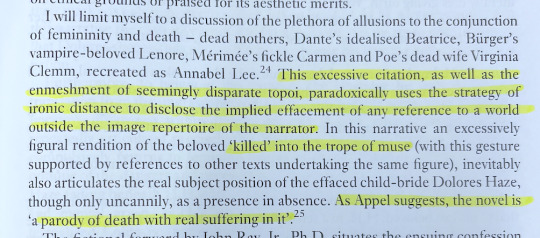

[ID 1: I will limit myself to a discussion of the plethora of allusions to the conjunction of femininity and death — dead mothers, Dante’s idealized Beatrice, Bürger’s vampire-beloved Lendore, Mérimee’s fickle Carmen and Poe’s dead wife Virginia Clemm, recreated as Annabel Lee. This excessive citation, as well as the enmeshment of seemingly disparate topoi, paradoxically uses the strategy of ironic distance to disclose the implied effacement of any reference to a world outside the image repertoire of the narrator. In this narrative an excessively figural rendition of the beloved ‘killed’ into the trope of muse (with this gesture supported by references to other texts undertaking the same figure), inevitably also articulates the real subject position of the effaced child-bride Dolores Haze, though only uncannily, as presence in absence. As Appel suggests, the novel is ‘a parody of death with real suffering in it.’

ID 2: More crucially, perhaps, by having his infatuated poet explicitly designate her death as the condition for a reading of his text, her actual death completes his figural killing. Their final scene of meeting in fact works on the basis of a transposition of the actual into the imaginary. When H.H., invoking Carmen one last time, asks Dolores to come with him and she replies ‘No,’ he writes ‘Then I pulled out my automatic — I mean, this is the kind of fool thing a reader might suppose I did. It never even occurred to me to do it.’ Yet in the next sentence, the parody of a murder fantasy is undone, for the girl waving goodbye is described as ‘my American sweet immortal dead love; for she is dead and immortal if you are reading this’ (278).

The movement of signifiers is from a literary death (Carmen’s) to its parodic disruption, to a metaphor where the girl stands for his dead love, to its literalization by virtue of a reference to an anticipated real death. This movement from death fantasy, through banalization, to literalization of the trope also occurs in respect to her maternity. Upon seeing Dolores again, H.H. admits, ‘the death I had kept conjuring up for three years was as simple as a bit of dried wood. She was frankly and hugely pregnant’ (267). Yet reality catches up and confirms this fantasy in the sense that, if figurally a nymphet dies once she turns mother, Lolita dies giving birth. What the narrative frame states on the surface, then, is that while for H.H. Lolita merely dies figurally into irretrievable absence (her smiling ‘no’) and into a trope (‘immortal dead love’), she actually dies as Dolly Schiller for Nabokov; her corpse feeds the text not the narrator. Yet by implications, H.H. invokes her actual death even as he also invokes her eternal survival as a signifier. He can accept her rebuttal, the loss of this desired object, because in his narrative representation he immediately exchanges the actual girl chanting ‘Good-by-aye’ with a premonition of the text he will have written about her. As in the ‘fort-da’ game, he translates her forced absence into his symbolic representation where he has seeming control over her death and her immortality; the one being the condition, the other the result of his poetic activity.

In the last sentence of his memoirs, anticipating his own death and invoking that of his lost beloved, H.H. in a sense places himself and his Lolita between the absent and the double, when he claims that his finished fiction is ‘the only immortality you and I may share, my Lolita’ (307). From the perspective of the poet, this is a gesture defying death, for he eternalizes not only his image of her, ‘my Lolita,’ and concomitant the fiction of their love (their shared immortality), but above all his signature. In respect to the represented woman, however, this gesture commemorates the absence of Dolores in the text. Invisible beneath the tropes and allusions to feminine figures of death, she marks the site where absence inscribes itself rhetorically into the text only to be recuperated on one side by death and on the other by the poet’s recourse to symbolic immortality — to ‘prophetic sonnets, the refuge of art’.

Framed within the context of the event leading up to its writing — namely Dolores Schiller’s refusal to leave her husband — the first paragraph of H.H.’s memoirs can be read as an apostrophe in a dual sense. He not only addresses a beloved who is by implication dead but also one who is decontextualized: ‘Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins… She was Lo… She was Lola… She was Dolly… She was Dolores… But in my arms she was always Lolita’ (9). This list of names in part serves to show the various roles she could be associated with as well as the chain of supplementary signifiers attached to her body. Above all, however, by addressing her without a patronymic, the narrator weakens her representation as a historical person and emphasizes her function as a freely floating signifier, an empty sign he possesses and on to which he can impose anterior meanings to produce a supplementary textual matrix. By privileging language over the body, restructuring Dolores Haze into the sign Lolita (‘My sin, my soul’), H.H. undertakes a figural ‘murder of the soma’, a blindness toward this girl’s irrreducible alterity, so as to make her signify his desire. He can master her material absence (the fort of the mother-to-be), by virtue of a symbolic control over her presence.

Because the real beloved is absent she must be represented and because the woman’s body is missing, stereotypes of femininity that seem to assure the narrator are possible. Yet, in this recreation, the perturbing difference she marked throughout in a somatic and a semiotic sense — because she eventually succeeded in running away from him even as his designations repeatedly missed their mark — is only imperfectly elided. Like a fetishist, H.H. commemorates with this narrative the castrative wound to his narcissism it is meant to negate, namely that Dolores successfully eludes his grasp because his love is a non-reciprocated fiction. end ID]

elisabeth bronfen on lolita, from over her dead body: death, femininity, and the aesthetic

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen of England, Countess of Angoulême, mother of fourteen surviving children, Isabella of Angoulême was a woman who spent most of her life in a position of power. Her reputation was ultimately shaped by the failings of her husband. She became an easy target for misogynistic tropes and topoi deployed by monastic chroniclers interested in explaining John’s failures as King. Yet a more careful analysis of the surviving historical record reveals a Queen who was anything but vanished who, from the age of just 12, performed an active and important role at the royal court and who, even after the death of her first husband, continued to wield power and hold influence. Up until her death, Isabella acted in a way which suggests she fully understood how to wield power and expected to be afforded the dignity and reverence which her position as queen consort was due.

-Sally Spong, "Isabella of Angouleme: The Vanished Queen", "Norman to Early Plantagenet Consorts: Power, Influence and Dynasty"

#historicwomendaily#isabella of angouleme#angevins#13th century#english history#king john#ig#queue#my post

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Walking, which alternately follows a path and has followers, creates a mobile organicity in the environment, a sequence of phatic topoi.

And if it is true that the phatic function [..] is already characteristic of the language of talking birds, just as it constitutes the ‘first verbal function acquired by children,’ it is not surprising that it also gambols, goes on all fours, dances, and walks about, with a light or heavy step, like a series of ‘hellos’ in an echoing labyrinth, anterior or parallel to informative speech.”

Michel de Certeau

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

honestly, i love editing nonfiction so much???? im editing a bunch of textbooks for seminary students rn, which is, you know, not the Thing I'm Into, but i also love deep diving into topics that have nothing to do with me? I love knowing what euaggelion and ecumenism mean, the difference between ecclesiastical and ecclesial, the history of proselytizing in the Philippines. Today I learned that the plural of topos is topoi?? I love editing??? it's like the perfect thing for the person who wanted to major in everything in uni

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think I cannot hold myself back anymore, so I will say it.

The fact that Sasuke and Naruto decide to marry two stereotypical, canonical, a-characterized girls is not a sign of a necessarily brotherly (merely platonic) bond.

In the medieval Japanese culture, in fact, true love often could be found only between two man (‘cause they are similar creatures and they can understand each other better than man/women couples - yeah, I know, how sexist, but we are talking about the 13th century sooo). It is possible to recognise the same idea in the antique Greece (even if usually the relationship is between teacher and his student - but the concept is, more or less, the same - you can see Platon about it). Marriage is a tool to grant reproduction and connection (Sasuke’s idea about “I want to repopulate the clan”, -yeah, alone and far away from home for 12 fucking years (r’u okay, dude?) Naruto dream of becoming hokage - never at home after:

-Hashirama that went for a walk everyday with his bff

-his brother who spent more time masturbating on proibite jutsu than actually ruling

-the third that, like the first, went for a walk but with Naruto instead

-the fourth: a loveable father and husband that had dinner at home with her wife and cooked as well

-tsunade: alcoholic, gambler, one of the sannins AND medic nin

-kakashi… well, you all know about his addiction for porn

-NARUTO: orphan, love-starved for life, can’t find the force to stay at home, shitty dad ecc ecc in time of peace.

Buuut oookkkkaaaayy?!).

Many aspects of Kishi’s plot and characters are inspired by historical Samurai’ customs and figures (also, the ninja world’ structure described by Kishi is more similiar to Samurai’ than that’s of true ninjas - whose usually are mercenaries and more similiar to bandits than heroes).

ALSO, who knows something, even if only the basics, about literature, can easily read in the entire story the most important iconographic topoi of romance and LOVE.

I will summarize some of them because there are many:

-Romeo and Juliet: “I’m the only one who can bear the full brunt of your hate! It’s my job, no one else’s! I’ll bear the burden of your hatred… And we’ll die together!”. Then, summarising the rest: “in the afterlife I will not be the vessil anymore; you will not be an uchiha ecc ecc”= Capuleti and Montecchi: Juliet and Romeo tried to bear the hatred that their families had for each other; finally only death permits them to love and realise their dream to stay in each other arms.

-in their afterlife (pre-mortem experience) Sasuke and Naruto are found together (no itachi, no parents - only the two of them)

-Achille and Patroclo (I think I won’t speak about that because I could spend VOLUMES)

-the love triangle

-star-watching while whispering the name of smone we love (or desire)

Anyway I have no watched Boruto and I don’t intend to: everything after the second Valley of End is no more than “found raising” (without charity) and politically correct (that of 15 years ago - especially in Eastern Countries). Same thing about The Last and these other craps: BULLSHIT: Naruto, suddenly, DON’T understand love anymore… came on, are u serious man?

PS when I think about chakras of two siblings I cannot not think about soulmates:

- chakra, like soul, have NO gender (and we all know that Naruto and Sasuke are not brother)

-if you insist about they being siblings thanks Indra’ and Asura’ chakras I have to remind you that VERY OFTEN in EVERY MYTHOLOGIES of the world (yeah, in Japan as well) between deities there is no incest concept and ooops Indra and Asura WERE SEMI-DEITIES, so..

I would thank my current occupation as phd student in History and Religion: that has helped a lot to understand the implicit tune of the show/manga

PSS the shit about “clingy Sakura yelp cause sasuke taps her forehead” is, precisely, bullshit: Itachi (sasuke’s real brother) did the same thing to keep away sasuke. When he says “I will always love you” he doesn’t do that, no SIR; also, when sasuke asks Naruto what he really means by “friend”, Naruto, at the very end says “I DON’T FUNCKIN KNOW, but when you hurt I hurt”. He is the one that really understands Sasuke NOT SAKURA

Also, Naruto frees Kurama (8 tails) after Hinata’s (fake) death, okay but, seriously? The seal is merely there at this point, everyone is dead, she tried to help him but cannot do it because is not a real ninja and he got LIVID. I understand that.. than he forget all that she had said

When the kages asks for sasuke elimination, Naruto is not angry, Naruto is broken and has a real panic attack, so… I think there are some difference due the circumstances.

The hints ‘bout canonical ships during the series are, really, unuseful like an ass with no hole.

So, I have to stop here. This is my deposition, your honor.

Sorry if I made mistakes but it’s late here, I’m tired and English is not my native language

#sasunaru#narusau#naruto#boruto#love#sasuke xnaruto#saske uchiha#uchihasasuke#naruto uzumaki#naruto universe#medieval#samurai#naruto x sasuke#Narutolovessasuke#sasuke loves Naruto#medieval Japan#ninjas#kishimoto#valley of the end

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Randomly stumbled upon this and YES. Infinity x YES!!! The people who made Episode IX never lost the plot on Star Wars. Certain audiences (the Very Online(TM) "fans" and critics) did.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animism is the ‘Big Step’ for our culture to make – acquiring the understanding, the sense, that the elements of the non-human world are animate in some way and have a spiritual nature: rocks, rivers, soil, not to mention all the other-than-human entities (which include not only plants and living organisms but also what are called ‘spirits’ in old parlance). It requires our mainstream cultural re-education as to the nature of reality, and the shedding of a number of received prejudices about the nature of mind. As it stands, animism is utter anathema to modern thought. But it has been a reality, a spiritual fact, to the countless ages of humanity that have preceded us.

Such mythopoetic relationship with the environment was one example of what the ethnologist Lucien Lévy-Bruhl called participation mystique. By this is meant a local relationship with the land that went beyond mere utility and subsistence. To the indigenous person, ‘Earth and sea are to him as living books in which the myths are inscribed,’ Levy-Bruhl stated (1935). Another anthropologist, A. P. Elkin, put it more specifically when writing about indigenous Australasian peoples: ‘The bond between a person and his (or her) country is not merely geographical or fortuitous, but living and spiritual and sacred. His country … is the symbol of, and gateway to, the great unseen world of heroes, ancestors, and life-giving powers which avail for man and nature’ (cited in Lévy-Bruhl, 1935, p.43).

In the West, this kind of relationship was noted at least as long ago as ancient Greece, where there were two words for subtly different senses of place, chora and topos. Chora is the older of the two terms, and was an holistic reference to place: place as expressive, place as a keeper of memory, imagination and mythic presence. Topos, on the other hand, signified place in much the way we think of it nowadays – simple location, and the objective, physical features of a locale. Topography. But, ultimately, even sacred places have become topoi.

[...]

Concepts of animism can take various forms. For many ancient societies the land was so alive it had a voice in their dreams. A clear account of this was provided by a Paiute Indian, Hoavadunuki, who was a hundred years old by the time he was interviewed by ethnographers in the 1930s. The old Indian stated that a local peak, Birch Mountain, spoke to him in his dreams, urging him to become a ‘doctor’ (shaman). The Paiute resisted, he said, because he didn’t want the pressures and problems that would come with that (Steward, 1934). Communication from this mountain occurred a number of times throughout the old man’s long life and was not seen as strange or peculiar by him – indeed, the idea of the land being capable of speaking to humans was probably widespread in ancient sensibility.

[...]

Sacred soundscapes were simply a natural corollary of that sensibility. The basic notion of the land having speech, or of being read like a text, was lodged deeply in some schools of Japanese Buddhism – in early medieval Shingon Esoteric Buddhism, founded by Kūkai, for instance. He likened the natural landscape around Chuzenji temple and the lake at the foot of Mount Nantai, near Nikko, to descriptions in the Buddhist scriptures of the Pure Land, the habitation of the buddhas. Kūkai considered that the landscape not only symbolised but was of the same essence as the mind of the Buddha. Like the Buddha mind, the landscape spoke in a natural language, offering supernatural discourse. ‘Thus, waves, pebbles, winds, and birds were the elementary and unconscious performers of the cosmic speech of buddhas and bodhisattvas,’ explains Allan Grapard (1994).

-- Jack Hunter (ed.), Greening the Paranormal: Exploring the Ecology of Extraordinary Experience

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Came across the word "topoi" in a book on rhetoric, described as model passages and oratory formulae atop which orators could structure their own spiel. The talk of bite-sized, widely circulated speech formats sounded kinda meme-ish so I ran a search and found this article from 2015 using Romney's viral "binders full of women" gaff to organize a comparison of the two. A good read, though I'm skeptical of the electoral impact the author ascribes to memes.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In the Greek world magic could be attributed both to intrinsic superhuman abilities and to knowledge of special tools. While some figures had innate ability, because of a link to divinity, others were understood to have access to magic via knowledge. Individuals, both in mythology and in real life, could be said to be using ‘magic’ when they used their knowledge of herbs to achieve various effects. The term pharmakis (female), or pharmakeus/pharmakos (male), is often used in this context; it is no coincidence that the term gives us the medical ‘pharmaceutical’, for in a pre-scientific age knowledge of medicine could often be seen as supernatural (see Lloyd, 1979). In Greek mythology there are many examples of figures who used magical herbs for different purposes. In the Odyssey Helen uses magic to soothe her guests (Book 4), while Kirke uses magic to transform men into animals (Book 10), and Hermes shows Odysseus how to use the magic Moly plant for protection. Kirke and Helen had links to the divine, but other people who used magic in ancient literature used more prosaic methods, relying on the magic of the plants, rather than the essential nature of the practitioner.

Such practices were often associated with women, particularly in the area of love charms. In tragedy, Deianeira, the wife of Herakles, killed him by using an ill-chosen love potion (the story told in Sophocles’ Trachiniae); the nurse in Euripides’ Hippolytus speaks of using a love charm to help Phaidra; and in Euripides’ Andromache, Hermione accuses Andromache of making her barren by using herbal charms against her (vv. 29–35, 155–60). The use of magic for erotic purposes is also seen in Idyll 2 by the Hellenistic poet Theocritos, who shows Simaithea attempting to win back her lover. Medea herself can be seen as a victim of love charms, as in Pindar Pythian 4. 214 ff. when Aphrodite deliberately sets out to help Jason. In Apollonios’ Argonautica, Medea is subjected to a violent attack by Eros, as we will discuss further in Chapter 7.

This idea of the witch is not confined to mythology, for there were legal cases which centred around accusations of witchcraft, as in the case of Demosthenes, Against Aristogeiton 79–80 (c. 330 BC) which alleges that Theoris was a witch (pharmakis) who killed her family with drugs. This case indicates how there are several areas of overlap between sociohistorical issues and literary topoi.

Medea has the attributes of a pharmakis, as her ability with drugs is central to her magical abilities. The collection of magical herbs is the central idea behind Sophocles’ Rhizotomoi, and in Ovid’s account of her involvement in the death of Pelias (Metamorphoses Book 7), it is the crucial omission of the magical herbs from the cauldron which causes the rejuvenation to fail. In the Greek tradition, this associates her strongly with the erotic use of magic, and with eastern traditions, for such abilities were generally believed to be strongest in Asiatic lands. The use of herbs was not the only aspect of magic which could be accessed by mortals, for the use of spells was also important – in the case of Deianeira and Simaithea, there is an important series of rituals to be performed to ensure the efficacy of the drug. Language was seen as a powerful magical tool in both mythological and real-life situations. In mythology, we think of the power of Orpheus, who was able to charm the rocks with his song, or the Sirens who lured sailors to their death. There are also many historical examples of how words were believed to have power, as individuals wrote spells or created objects with words on them to achieve magical ends. We have surviving examples of papyri and amulets, and many examples of curse tablets, particularly binding curses, called in Greek katadesmoi or in Latin defixiones. In this context, the power of Medea’s voice is important, in that she has the ability to deceive, tricking those around her, be they her own family or the daughters of Pelias.

If magical knowledge can be accessed by mortals, Medea also exhibits magical behaviours which are more in keeping with her divine ancestry, and which testify to an innate supernatural ability. She is said to have control over the forces of nature, ability to control the weather and animals, and the ability to fly (albeit with the aid of a chariot). In Corneille’s seventeenth-century tragedy Medea has a magic wand and a magic ring, attributes which link her with figures of Faerie. A particular feature of Medea’s myth is the ability to inflict psychological harm, a complement to her power to deceive with language. The most powerful demonstration of this ability comes from Apollonios’ description of how she causes the death of Talos by casting the evil eye and causing him to fall (Argonautica 4. 638–88). . . An alternative version is given by Apollodorous, who suggests that Medea may have caused Talos’ death by the same powers of persuasion she used against Pelias: ‘According to some she drove him mad with her drugs, while according to others, she promised to make him immortal and pulled out the nail, causing him to die when all the ichor flowed away’ (Bibliotheca 1.9.26, trans. Hard, 1997).”

- Emma Griffiths, Medea

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

On one end of the scale was criminal neglect or infanticide, perpetrated by sinful mothers; on the other was benign neglect or abandonment, practiced by saintly mothers. The crucial factor, here as elsewhere in medieval ethics, was not the effect of an action on its object, but the motive of the agent.

Unfortunately, it is the motive that most often eludes a historian's gaze. Since we learn of saintly mothers who abandoned their children primarily through their hagiographers, we cannot know with confidence how they actually felt about this decision. It is probably safest to assume a variety of motivations and mixed feelings on the part of women who are said to have renounced their children or accepted their deaths with composure. But it is no accident that this motif often follows hard on the heels of another topos—the young girl who would have preferred to remain a virgin, but obediently complied with her parents' wish that she marry. If these topoi give access to reality at all, even as refracted through an idealizing lens, it is likely that at least some of the mothers who eventually played Paula or Griselda to their young ones had borne them with reluctance from the start. After a survey of the evidence, we may be able to disentangle some of the complex strands of resentment, resignation, and idealism that transformed these 'monstrous mothers' into maternal martyrs.

Barbara Newman, excerpt from ‘“Crueel Corage”: Child Sacrifice and the Maternal Martyr in Hagiography and Romance’ from From Virile Woman to WomanChrist: Studies in Medieval Religion and Literature

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

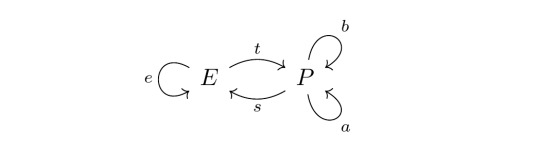

Subobject classifiers of graphs-as-presheaves

Following up on these posts where we view (directed multi-) graphs as set-valued contravariant functors (a.k.a. presheaves) on the small category Q = V ⇉ A, with s,t: V -> A the non-identity morphisms. There's another way in which categories of presheaves such as Q^hat are interesting: they are topoi. An (elementary) topos, following Mac Lane, is a category E that has all finite limits, is cartesian closed, and has a subobject classifier. Supposedly all presheaf categories have this, so let's examine how this manifests itself in graphs.

In particular, I want to check out subobject classifiers. Maybe we'll do limits and cartesian closure at a later date. So in a category C, a subobject of an object A is an isomorphism class of specific kinds of morphisms into A. Let us construct the category Mono(A), whose objects are the monomorphisms into A. A monomorphism (or a morphism that is monic) into A is a C-morphism m: B -> A from some object B such that if f,f': C -> B are parallel morphisms into B such that m ∘ f = m ∘ f', then f = f'. That is, the monos are exactly the left-cancellative morphisms. In the categories of sets, groups, vector spaces, and various other algebraic categories the monos are exactly the morphisms whose underlying set functions are injective, which is why we look at monomorphisms to define subobjects.

The morphisms of Mono(A) from m: B -> A to m': C -> A are the C-morphisms p: B -> C such that m = m' ∘ p. Let's call such morphisms 'factoring morphisms'. If there is a factoring morphism m -> m', we say that m 'factors through' m', denoted m ≤ m'. Clearly the relation ≤ is reflexive and transitive. If both m ≤ m' and m' ≤ m hold, then there are p: B -> C and q: C -> B such that m = m ∘ q ∘ p and m' = m' ∘ p ∘ q. Because m and m' are monic we can cancel them on the left in these equations, from which we find that q ∘ p = id_B and p ∘ q = id_C, so m and m' are isomorphic in Mono(A). Any two isomorphic monos embed their domain into A 'in the same way', so a subobject of A is defined to be an isomorphism class of monos into A. Let Sub(A) denote the set of subobjects of A (technical note: these isomorphism classes may be proper classes, rather than sets; in the case of Q^hat we can pick canonical representatives of the classes, which resolves the issue). The factoring through relation ≤ induces a partial ordering on Sub(A), which coincides with subobject containment in all the familiar cases.

In a category C with a terminal object 1, a subobject classifier is an object Ω of C together with a monomorphism T: 1 -> Ω such that for all objects A,B and monos m: B -> A there is a unique morphism ξ: A -> Ω such that m is a pullback of T along ξ. Rather than unwrap these definitions fully immediately, let's see what this looks like in Set.

If we take Ω = {true,false}, the set of Boolean values, and we let T: {0} -> {true,false} be defined as T(0) = true, then I claim that this forms a subobject classifier for Set (where we assume some background logic of our set theory that includes the principle of excluded middle; otherwise the subobject classifier is more complicated). Let A be a set, and let B ⊆ A be some subset. Let ξ: A -> {true,false} be the function such that ξ(x) = true if x ∈ B and ξ(x) = false if x ∉ B. In Set, a construction of the pullback object of two functions f: Y -> X and g: Z -> X is the set {(y,z) ∈ Y × Z : f(y) = g(z)}. The 'pullback of f along g' is then the projection of this set to Z, and similarly for g along f. What's the pullback of T along ξ? The pullback object is (up to a canonical bijection) the set {(x,0) ∈ A × {0} : ξ(x) = T(0) = true}. There is a canonical bijection between this set and B, and more importantly the inclusion of B into A does the same thing as the projection of the pullback set onto A, because B contains exactly those points x for which ξ(x) = true. It follows that the inclusion function B ↪ A is a pullback of T along ξ.

So, the moral of the story is that Ω is the (object part of the) subobject classifier of some category C if the subobjects Sub(A) of an object correspond naturally to morphisms A -> Ω. We think of ξ: A -> Ω as analogous to the indicator function of a subset, we think of Ω as the set of truth values for 'internal logic' of the category, and we think of T as picking out the subobject of Ω that corresponds to 'true'. I could spin a yarn about why defining this in terms of pullbacks gets you exactly what you want it to be, but this post is long enough already. Tl;dr categorical limits are cool and powerful.

What does Ω look like in Q^hat, our category of graphs? First we would like to know when a graph homomorphism φ: G₁ -> G₂ is monic. A good first guess would be that φ is monic when its vertex and arrow functions φ_V: G₁(V) -> G₂(V), φ_A: G₁(A) -> G₂(A) are injective. This is exactly correct. If we assume that φ_V is not injective, then there are two vertices of G₁ that get mapped onto the same vertex in G₂. It follows that there are two distinct graph homomorphisms from the graph that just has one vertex and no arrows into G₁ such that postcomposing with φ gives you the same homomorphism into G₂ (i.e. φ is not monic). The same holds true if φ_A is not injective, but then there are distinct homomorphisms from the graph that has two vertices and an arrow between them. It is no coincidence, by the way, that these are the graphs よ(V) and よ(A) from my first post on this subject. The representable presheaves always generate the category of presheaves, in the sense that the morphisms out of them together can always 'differentiate' two distinct morphisms. Anyway. If both φ_V and φ_A are injective, then φ is indeed monic, for the same reason that injective functions are monic in Set (it's a nice exercise to work out!).

We've discovered that the subobjects of graphs are exactly the subgraphs. Let's give ourselves a pat on the back for that one. What graph can serve as Ω? Well, the arrow set Ω(A) must contain 5 elements, corresponding to the 5 subgraphs of よ(A). The vertex set Ω(V) has 2 elements, for the 2 subgraphs of よ(V), call them E and P, for 'empty' and 'point'. The source function Ω(s): Ω(A) -> Ω(V) maps a subgraph of よ(A) onto E if it does not contain the source vertex of よ(A) and onto P if it does. The target function Ω(t): Ω(A) -> Ω(V) does the same but for the target vertex instead. Let us write Ω(A) = {a,b,s,t,e}, for 'arrow', 'both points', 'source point', 'target point', and 'empty'. I'm sure you can image which names refer to which subgraph. Both a and b are loops on the vertex P. s is an arrow from P to E. t is an arrow from E to P. e is a loop on E.

The terminal object 1 in Q^hat is the constant functor on a one point set, so as a graph it has a single vertex and a single loop on it. The 'truth' morphism T: 1 -> Ω is the graph homomorphism that picks out the vertex P and the loop a in Ω. On any graph G, we can specify a subgraph G' uniquely by picking out a subset of the vertices and a subset of the arrows of G, such that the source and target of any arrow of G'(A) is also a vertex of G'(V). We construct the indicator homomorphism ξ: G -> Ω as mapping all vertices of G' onto P and all vertices not in G' onto E. Furthermore, an arrow gets mapped onto a if and only if it is an arrow of G'. This is actually enough to uniquely specify ξ, but let's work it out some more. Arrows that connect vertices that are not in G' get mapped onto e. Arrows from a vertex of G' to one outside it get mapped to s. The other way round get mapped to t. Arrows between vertices of G' that are not arrows of G' get mapped to b. And there you go! The subobject classifier for the category of graphs :)

#math#holy fuck this was longer than i thought it was gonna be#but what a cool result!#in the original draft i wanted to fully prove that Q^hat is an elementary topos#but on second thought i think i'll save finite completeness and cartesian closure for later :p

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Von der Unbeständigkeit

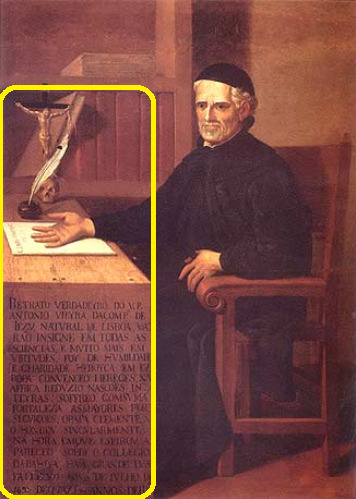

1.

In Kapitel III seines Buches über die Unbeständigkeit der wilden Seele erinnert Eduardo Viveiros de Castro an Antonio Vieira, also an den jesuitischen Rhetor, dessen Bildnis oben in beiden Spalten der ersten Zeile auftaucht. Das Gemälde stammt aus dem 18. Jahrhundert, der Name des Malers ist verloren gegangen, er hatte das Bild nicht an Vieira adressiert und nicht mit seinem Namen signiert. Das Bild ist schon auf Leinwand gemalt, nicht mehr auf den Holztafeln, die der Tafel den Namen gegeben haben. Der Maler malt aber eine Holztafel auf die Leinwand, darauf Schreibpapier, darauf liegt, ich würde sagen verdreht und so präsentierend, mit dem Handrücken zum Papier auf der Fläche und der offenen Fläche der Hand in den Raum hinein, die Hand des Rhetor, ein wichtiges Instrument. Auf der Seite der Holztafel steht ein Text, das ist ein Bildkommentar.

Ich halte das Objekt, auf dem auf dem erst das Papier, dann die Hand sitzt, für eine Stele, für die Form einer Augentäuschung und wegen der Beschriftung auch für ein 'fotografisches Element'. Der Maler malt an einr Täuschung, an einem Austausch und an einer Austauschbarkeit, er arbeitet dazu noch an dem Bestand, den Worte, Schreiben und Bilder haben. Davids Bild des toten Marat ist auch ein Bild, in dem David an Austausch und Austauscharkeiten arbeitet, unter anderem einem Austausch der Signatur, einem Austausch von Worten, von Geld und von Personen, Gesellschaftsformen und Regierungen. Das steht alles nicht unbedingt im 'Zentrum des Bildes' und ist alles nicht das, was man vielleicht den eigentlichen Inhalt nennen würde. Es sind Formen, die dort an den Bildern vorkommen und dort bewegt werden (schon weil sie anders als an anderen Stellen vorkommen, sie werfen auf das Bild bewegt, ohne sich dort unbedingt bewegen zu müssen). Sie werden dort auch bewegend, sie afffizieren zum Beispiel Betrachter oder animieren Maler, auch solche Formen auf ihre Bilder zu bewegen. Man muss Formen, die am Rand sein können, nicht ernst nehmen, kann das aber tun.

2.

Viveiros de Castro erinnert an den jesuitischen Rhetor, weil der, so heißt es in dem Kapitel, einen der mächtigsten topoi der jesuitischen Literatur über die indigene Bevölkerung entwickelt habe. Die sei schwer missionierbar. Vieira ist jemand, der andere missionieren, bekehren will, wie es heute Aktivisten mit einem wollen.

Bekehren ist eine Kulturtechnik, mit der man jemanden eindringlich in eine Richtung kehren will, meist Richtung eines Glaubens, seiner Dogmen und Praktiken. Man kann das von der Erziehung unterscheiden, aber es hängt zusammen. Die indigene Bevölkerung ist dem Jesuiten also auch ein Problem, weil er sie zwar erziehen, sie sich aber schwer erziehen lassen. Der Topos kommt nicht nur in der jesuitischen Rhetorik Brasiliens vor und nicht nur in Bezug auf eine indigene Bevölkerung, aber dort kommt er besonders vor. Antonio Vieira mag ein Sonderling, jemand Besonderes sein, aber nicht, weil er missionieren und erziehen will, was schwer missionier- und erziehbar ist.

Besonders ist er durch die Art und Weise, wie er die Situation erklärt, denn das ist der erwähnte Topos. In seinem Kommentar schreibt Eduardo Viveiros de Castro dazu:

Die Heiden dieses Landes lassen sich nur schwer konvertieren. Nicht, weil sie aus widerständigem und sprödem Material waren; im Gegenteil: Neuen Formen durchaus offen, waren sie dennoch zu jeder dauerhaften Prägung unfähig. Für alle Gestalten empfänglich, aber jeder dauerhaften gestaltung verschlossen, war die indigene Bevölkerung, um eine weniger europäische Analogie als die Myrtestatue zu benutzen, wie der Urwald, der sie umgab: stets im Begriff, sich über den von der Kultur mühsam eroberten Räumen wieder zu verschließen.

Kerbt man ihnen etwas ein, schliesst sich Bresche wieder: eventuell beschreibt der Kommentar auch so etwas. Der Jesuit beschreibt die indigene Bevölkerung wie (Luh-)man(n) eine vague Assoziation beschreiben kann, deren Wille schwach und nicht augeprägt ist, getrieben mit dem Wind wie die Wellen und darum getrieben in Wellen, mit oberflächlichen Gefühlen.

Vielleicht kann man il selvaggio è mobile, das ist ein kursiv gesetzer Satz in dem Aufsatz, noch einmal so übersetzen: Die aus und in den Tropen sind, die sind nicht kontrafaktisch stabilisiert. Der Kommentar von Viveiros de Castro bezieht sich auch auf eine Passage Sermao do Espirito Santo von 1657. Da schreibt Antonio Vieira:

Es gibt Völker, die von Natur aus hart sind, zähl und dauerhaft, die nur schwer den Glauben annehmen und mit den Verfehlungen ihrer Vorfahren brechen; sie widersetzen sich mit Waffengewalt, zweifeln mit ihrem Verstand, wehren sich mit starkem Willen, versperren sich, sträuben sich, diskutieren, wiedersprechen und es kostet große Mühen, sie zu bezwingen; sind sie aber einmal bezwungen, haben sie einmal den Glauben angenommen, dann glauben sie fest und beständig, wie Statuen aus Marmor. Und es gibt dagegen andere Völker - und zu diesen gehören die brasilianischen - die alles, was man sie lehrt, mit großer gelehrigkeit und Leichtigkeit aufnehmen, ohne zu diskutieren, zu widersprechen, zu zweifeln oder sich zu widersetzen; aber sie sind wie Stauen aus Myrte, die, wenn man sie der Hand und der Gartenschere entzieht, ihre neue Form bald wieder verlieren und ihre alte und natürliche Roheit wieder annehmen und zu demselben Gestrüpp werden, das sie zuvor gewesen sind.

3.

Exkurs: Das Bild, dessen Urheber seinen Namen verlor und dessen Urbild Antonio Vieira heißt, hängt heute in einem Weingut und gehört mit dem Weingut dem Haus Schönborn. Dieses Weingut wird von Teresa Gräfin Alvares Pereira von Schönborn-Wiesentheid geleitet. Wenn Beständigkeit, dann schon richtig, aber ist das richtig?

Die Indianer, so sehen das die Jesuiten, trinken die falschen fermentierten Getränke, sie trinken Cauim. In den Texten ist manchmal von Wein die Rede und davon, dass die Jesuiten die Leute vom Wein abbringen wollten, das scheint mir seltsam. Vom Cauim wollten sie die Leute abbringen. In Europa trinken die Leute, um zu vergessen; in den Tropen, um nicht zu vergessen. Da muss demnächst Ricardo Spindola noch einmal genauer von berichten, das ist alles noch sehr verwirrend.

4.

Bei der Unbeständigkeit, über die Viveiros de Castro, wie er schreibt, ein wenig aufklären will, handele es sich sicherlich, das sagt er so, um etwas ganz Reales. Wenn es schon keine Seinsweise sei, sei es eine Weise, in der die Gesellschaft der Tupinamba in den Augen der Missionare erschien. Der Autor spricht von einer Erscheinungsweise, die der energeia verwandt ist. Dieser Begriff wird in der Rhetorik unter verwendet, um ein Verfahren zubeschreiben, mit dem was etwas vor Augen stellt oder, etwas komplizierter und im Hinblick auf Aby Warburg gedacht, vor Augen lädt (vor Augen polar bewegt/ vor Augen wendet/ vor Augen kehrt/ vor Augen kippt). In der Rhetorik wird der Begriff freilich auf eine Kulturtechnik bezogen, die in der Hand des Rhetors liegen soll: er lässt erscheinen. Viveiros de Castro sprich aber von einer Weise, die etwas Reales sei und der Gesellschaft der Tupinamba zu kam; die Gesellschaft erscheint, sie ist zumindest darin involviert, dem Rhetor zu erscheinen.

Viveiros de Castro möchte die Unbeständigkeit nicht als bloße Fiktion, nicht als bloßes Klischee, nicht als reines Bild beschreiben, nicht als Phantasma, dessen Medium allein die Kolonialherren und die Missionare waren. Dass die Tupinamba wirklich unbeständig waren, das will Viveiros de Casto auch, aber nicht nur sagen, weil diese Unbeständigkeit auch durch symbolische, phantasmatische Verhälltnisse und künstlichen Welten, durch einen normativen Kosmos getragen gewesen sein soll, zu dem man ohne Distanzschaffen und ohne Austauschmanöver (auch zwischen den Tupinamba und den Missionaren) keinen Zugang bekommt. Hoffentlich einfacher gesagt, sagt Viveiros de Castro, man müsse die Unbeständigkeit in ein größes Bild einordnen, also auch das Reale daran immer noch in ein Bild einordnen oder auf auf einer Tafel sortieren. Die Padres seien und bleiben verzweifelt gewesen, und das habe an einer wundersamen (magisch-rationalen?) Beziehung zum Glauben gelegen:

Dazu veranlagt, alles zu verschlingen, sträubten sie sich, wenn es ihnen einen Vorteil versprach und begannen, die 'alten Bräuche wieder auszukotzen (Achieta, 1555)

2 notes

·

View notes