#venera probe

Text

So Venus is my favorite planet in the solar system - everything about it is just so weird.

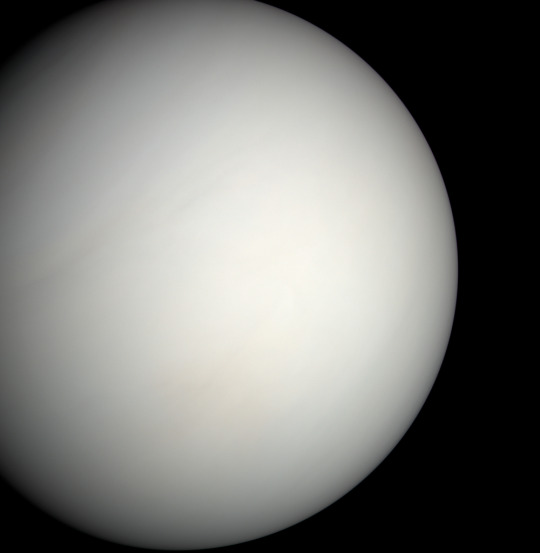

It has this extraordinarily dense atmosphere that by all accounts shouldn't exist - Venus is close enough to the sun (and therefore hot enough) that the atmosphere should have literally evaporated away, just like Mercury's. We think Earth manages to keep its atmosphere by virtue of our magnetic field, but Venus doesn't even have that going for it. While Venus is probably volcanically active, it definitely doesn't have an internal magnetic dynamo, so whatever form of volcanism it has going on is very different from ours. And, it spins backwards! For some reason!!

But, for as many mysteries as Venus has, the United States really hasn't spent much time investigating it. The Soviet Union, on the other hand, sent no less than 16 probes to Venus between 1961 and 1984 as part of the Venera program - most of them looked like this!

The Soviet Union had a very different approach to space than the United States. NASA missions are typically extremely risk averse, and the spacecraft we launch are generally very expensive one-offs that have only one chance to succeed or fail.

It's lead to some really amazing science, but to put it into perspective, the Mars Opportunity rover only had to survive on Mars for 90 days for the mission to be declared a complete success. That thing lasted 15 years. I love the Opportunity rover as much as any self-respecting NASA engineer, but how much extra time and money did we spend that we didn't technically "need" to for it to last 60x longer than required?

Anyway, all to say, the Soviet Union took a more incremental approach, where failures were far less devastating. The Venera 9 through 14 probes were designed to land on the surface of Venus, and survive long enough to take a picture with two cameras - not an easy task, but a fairly straightforward goal compared to NASA standards. They had…mixed results.

Venera 9 managed to take a picture with one camera, but the other one's lens cap didn't deploy.

Venera 10 also managed to take a picture with one camera, but again the other lens cap didn't deploy.

Venera 11 took no pictures - neither lens cap deployed this time.

Venera 12 also took no pictures - because again, neither lens cap deployed.

Lotta problems with lens caps.

For Venera 13 and 14, in addition to the cameras they sent a device to sample the Venusian "soil". Upon landing, the arm was supposed to swing down and analyze the surface it touched - it was a simple mechanism that couldn't be re-deployed or adjusted after the first go.

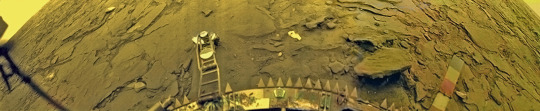

This time, both lens caps FINALLY ejected perfectly, and we were treated to these marvelous, eerie pictures of the Venus landscape:

However, when the Venera 14 soil sampler arm deployed, instead of sampling the Venus surface, it managed to swing down and land perfectly on….an ejected lens cap.

#space#space history#venus#NASA#Venera#spost#I will talk all day about venus#ask me about venus floating sky cities#unpopular opinion venus > mars#this is probably my favorite space history story#the surface of venus is made of lens caps#don't try to tell me the universe doesn't have a sense of humor#well#I guess its more that people have a sense of humor and we happen to live in the universe

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

So, I was reading about the Soviet Venera Venus probes and realized that the best picture we have (of about two) the surface of Venus would coincide (kinda) with Apollo-Soyuz in the FAM timeline. (That's right, we have pictures of the surface of Venus from 1975 and 1982.)

So.

****

Margo entered the room with a large print out. “Sergei, I must admit that I’m impressed with the image from Venera that you just released.”

He looked up from his work. “I’m glad they finally released them.”

She shook her head, trying to calculate how the Soviets built a probe that survived the surface of Venus. “Someday, you will have to tell me how y’all did it.”

He smirked. “Superior Soviet engineering.”

She rolled her eyes in irritation. “So superior that one of the lens caps failed and you got half an image.”

He looked around the room with a smile. “I must have missed the American probe that landed on Venus.”

“We were too busy with the Voyagers and the outer planets.”

“Ah,” he replied. “Those were pretty pictures. But there’s nothing like, is the phrase, ‘boots on the ground’? Like the first boots we put on the moon?”

She crossed her arms and huffed. “You only won because I wasn’t in charge of NASA then. I’m gonna make sure we kick your ass to Mars.”

He laughed.

“What? You don’t believe me?”

He looked at her. It was one of those looks that she felt in the pit of her stomach and tried to ignore the feeling. “Margo, if you told me you were going to plant the American flag on Jupiter, I’d believe you.”

She could feel her face warm and looked away.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

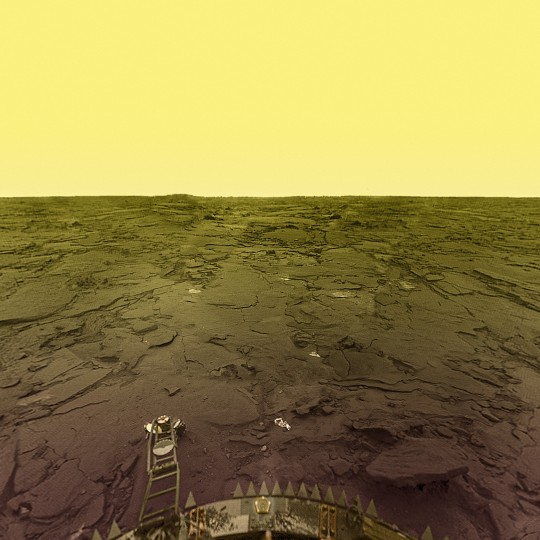

Only 4 spacecraft have ever returned images from Venus’ surface. The world next door doesn’t make it easy, with searing heat and crushing pressure that quickly destroy any lander.

In 1975 and 1982, 4 of the Soviet Union’s Venera probes captured our only images of Venus’ surface. The Veneras, which mean “Venus” in Russian, scanned the surface back and forth to create panoramic images of their surroundings. They revealed yellow skies and cracked, desolate landscapes that were both alien and familiar—views of a world that may have once been like Earth before experiencing catastrophic climate change.

Ted Stryk, a philosophy professor at Roane State Community College in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, specializes in reconstructing images from early space missions. Using data from the Russian Academy of Sciences, he has over time reconstructed the best-possible versions of the original Venera panoramas.

VENUS SURFACE PANORAMA FROM VENERA 9 This 1975 panorama from the Soviet Union's Venera 9 probe includes the first images ever taken from the surface of another planet.Image: Russian Academy of Sciences / Ted Stryk

VENUS SURFACE PANORAMA FROM VENERA 10 The Soviet Union's Venera 10 probe captured this panorama of Venus's surface in 1975.Image: Russian Academy of Sciences / Ted Stryk

VENUS SURFACE PANORAMA FROM VENERA 13 FRONT CAMERA The Soviet Union's Venera 13 probe captured two color panoramas of Venus's surface in 1982. This panorama came from the front camera.Image: Russian Academy of Sciences / Ted Stryk

VENUS SURFACE PANORAMA FROM VENERA 13 REAR CAMERA The Soviet Union's Venera 13 probe captured two color panoramas of Venus's surface in 1982. This panorama came from the rear camera.Image: Russian Academy of Sciences / Ted Stryk

VENUS SURFACE PANORAMA FROM VENERA 14 FRONT CAMERA The Soviet Union's Venera 14 probe captured two color panoramas of Venus's surface in 1982. This panorama came from the front camera.Image: Russian Academy of Sciences / Ted Stryk

VENUS SURFACE PANORAMA FROM VENERA 14 REAR CAMERA The Soviet Union's Venera 14 probe captured two color panoramas of Venus's surface in 1982. This panorama came from the rear camera.Image: Russian Academy of Sciences / Ted Stryk

youtube

#Venus#Russian Academy of Sciences#Venera#Ted Stryk#Venera 14#Venera 13#Venera 9#Venera 10#space#astronomy#astrophotography#religion is a mental illness#Youtube

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

People rightly get emotional about the perceived humanity of the Mars rovers but I just have to go off for a moment about the Soviet Venera program of the 60s-80s and how it gets me feeling just as emotional.

I think part of the appeal of the Mars rovers is their longevity—they have stuck around far longer than their projected lifespans, occasionally performing little rituals that reinforce the connection between these robots and their human parents (eg. the “happy birthday” song).

In contrast, the final and most sophisticated Venera landers lasted barely 2 hours on the surface of Venus. Why? Venus is a fucking hellscape that’s like 850°F (454°C) on the surface, with an atmospheric pressure 95 times higher than Earth’s, cloaked in corrosive clouds. Despite these insane conditions, Soviet scientists and engineers sent 16 spacecraft to Venus.

They failed a lot. The first two probes didn’t even get there. Venera 3 made it all the way. On board it carried a variety of scientific sensors, and a set of Soviet medallions. It impacted the surface in March 1966, but its instruments failed long before it could send back anything relevant. It was pulverized by the pressure and melted down into slag by the heat.

A year later, a reinforced Venera 4 managed to send back the atmospheric data its sibling hadn’t been able to capture. It was the first spacecraft to take these measurements on another planet. As it descended down into the hell that it was analyzing (91°F...200°F...oh...346°F... 504°F...oh god), the probe cracked open at the top and was crushed before reaching the surface. Like an egg. Like a skull.

Due to the data it sent back, the mission was considered a success, but its engineers had actually hoped that it would have been able to endure and make a soft landing. They had designed it to survive even in the unlikely event that it landed in water, and had equipped it with a battery that would last up to 100 minutes. Initially did not want to accept that it had not reached the surface intact.

In 1970, Venera 7 was the first probe to succeed in landing, but not without its own struggles. Things were going well until just before touchdown, when its parachute failed. The probe hit harder than expected, but it was so incredibly overbuilt that this time its titanium skull did not crack, merely toppling over onto its side and throwing its transmitter out of alignment. It was presumed dead, but, as scientists would only realize weeks later, it fought on for another 23 minutes, transmitting a faint stream of data back to its home millions of miles away before succumbing to the temperature and pressure.

Into the 80s, the Soviet Union landed 6 more spacecraft on the surface of Venus. They took color photographs (the first from another planet), recorded sound, and analyzed the soil. They allowed us to pull back Venus’s poisonous veil and see something we were not designed to see. These later landers were rated to last only 30 minutes on the surface, but they generally doubled or tripled that time. Under stifling heat, toxic air, and immense pressure, they gave their best until they ultimately boiled away.

If Mars ain’t the kind of place to raise your kids, Venus is worse. The Mars rovers are like children you can watch grow up and slowly become more distant with age. The Venera probes/landers were children that their Soviet parents poured their time and energy and love into all the while knowing that they were going to be consumed in a blaze of glory turned miserable death. That their useful lifespans would be measured in mere minutes.

Maybe this is just me ascribing feelings that weren’t there to the engineers and anthropomorphizing the robots too much, I’m no scientist, but emotionally that is gut wrenching. When I first learned about these missions I cried. And not only because I feel for the spacecraft. This is also a story about a nation and culture that no longer physically exists (paralleling the landers themselves). Throwing a bunch of progressively more overbuilt stuff at a seemingly crazy task is one of the most stereotypically Soviet things I can think of. All of the Venera missions carried special medallions engraved with Soviet imagery and made out of titanium so as to withstand the Veniusian environment. On some other planet, possibly the only evidence of human existence is a bunch of melted metal and possibly a few representations of something that no longer exists, something that a lot of people at the time believed in, that held their hopes and dreams—that is haunting. To me the Venera program encapsulates a lot of the same elements of unexpected humanity as the saga of the Mars rovers, but is more tragic because it has a different level of temporality.

#feeling emotional about some hunks of metal again tonight lads#long post#sorry about that#I only meant for this to be like 1 paragraph and then realized I couldn't fit in it all in to just that#also like even if you hate the soviet union I think we can agree there is something to this#like on a human sociological level#venera#venera program#ussr#venus#mars#Soviet Space Program

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

ESA approves EnVision

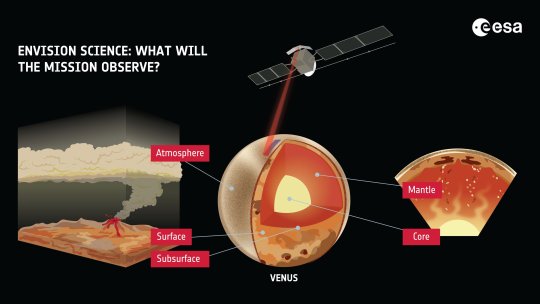

ESA's next mission to Venus was officially "adopted" today by the Agency's Science Program Committee. EnVision will study Venus from its inner core to its outer atmosphere, giving important new insight into the planet's history, geological activity and climate.

Being adopted means that the study phase is complete and ESA commits to implementing the mission. Following selection of the European industrial contractor later this year, work will soon begin to finalize the design and build the spacecraft. EnVision is foreseen to launch on an Ariane 6 rocket in 2031.

"Since the mission was selected back in 2021, we have advanced from broad science goals to a concrete mission plan," says ESA EnVision study manager Thomas Voirin. "We're very excited about moving to the next step. EnVision will answer longstanding open questions about Venus, arguably the least understood of the solar system's terrestrial planets."

Venus is Earth's closest neighbor—much closer than Mars—and very similar to our home planet in mass and size. Unlike Earth, however, it is not a pleasant place to visit. Of the solar system's rocky bodies, it has the densest atmosphere, and it is completely covered by layers of thick clouds made mostly of sulfuric acid. The surface of Venus is a scorching 464°C on average, with a crushing air pressure 92 times bigger than we experience on Earth's surface. This leaves us to wonder: How and when did Earth's twin become so inhospitable?

Science with EnVision

The measurements EnVision makes will help unravel key mysteries of our hot neighbor. For example, EnVision will reveal how volcanoes, plate tectonics and asteroid impacts have shaped the Venusian surface, and how geologically active the planet is today. The mission will also investigate the planet's insides, collecting data on the structure and thickness of Venus's core, mantle and crust. Last, it will study the weather and climate on Venus, including how they are affected by geological activity on the ground.

"Special to EnVision is the mission's approach to studying the entire planet as a system. It will investigate Venus's surface, interior and atmosphere with unprecedented accuracy, allowing us to understand how they work and interact with each other. For example, EnVision will use multiple measurement techniques to search for signatures of active volcanism at the surface and in the atmosphere," explains Anne Grete Straume-Lindner, the mission's project scientist.

To enable this holistic investigation, EnVision will carry an extensive set of scientific instruments. It will be the first mission to directly probe beneath Venus's surface, using its subsurface radar sounder. A second radar instrument, VenSAR, will map the surface with a resolution down to 10 meters and determine properties such as surface texture. Three different spectrometers will study the make-up of the surface and atmosphere. And a radio science experiment will use radio waves to study the planet's internal structure and properties of the atmosphere.

Strong heritage and fruitful cooperation

EnVision will join ESA's science fleet of solar system explorers. These missions address two top-level science themes of ESA's Cosmic Vision 2015–2025, namely: What are the conditions for planet formation and the emergence of life? and How does the solar system work?

It will be the second European mission to Venus. ESA's Venus Express (2005–2014) focused on the planet's atmosphere, but also made dramatic discoveries that pointed to possible volcanic hotspots on the planet's surface. The study of the atmosphere has continued with JAXA's Akatsuki mission, which is still actively tracking atmospheric movement and Venusian weather.

Longer ago, NASA's Mariner and Pioneer Venus missions (1960s and 1970s), the Soviet Union's Venera and Vega missions (1960s to 1980s), and NASA's Magellan radar mapping mission (1990–1994) painted a picture of a dry world, with landscapes shaped by volcanoes and intense geological activity. They discovered vast plains marked by lava flows, bordered by highlands and mountains. EnVision's VenSAR instrument, expected to be contributed by NASA, will map the Venusian surface at a much higher resolution than Magellan, distinguishing surface features more than ten times smaller.

This time around, EnVision will not be alone on its trip to Venus. Expecting a fruitful collaboration, NASA has also selected two new missions to Venus as part of its Discovery Program: DAVINCI (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging) and VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy). Together, EnVision, DAVINCI and VERITAS will provide the most comprehensive study of Venus ever.

TOP IMAGE....Artist impression of ESA's EnVision mission at Venus. Credit: ESA/VR2Planets/Damia Bouic

LOWER IMAGE....EnVision science: what will the mission observe? Credit: ESA (acknowledgement: work performed by ATG under contract to ESA), CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 3.5

1953 – Joseph Stalin, the longest serving leader of the Soviet Union, dies at his Volynskoe dacha in Moscow after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage four days earlier.

1960 – Indonesian President Sukarno dismissed the Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat (DPR), 1955 democratically elected parliament, and replaced with DPR-GR, the parliament of his own selected members.

1963 – American country music stars Patsy Cline, Hawkshaw Hawkins, Cowboy Copas and their pilot Randy Hughes are killed in a plane crash in Camden, Tennessee.

1963 – Aeroflot Flight 191 crashes while landing at Aşgabat International Airport, killing 12.

1965 – March Intifada: A Leftist uprising erupts in Bahrain against British colonial presence.

1966 – BOAC Flight 911, a Boeing 707 aircraft, breaks apart in mid-air due to clear-air turbulence and crashes into Mount Fuji, Japan, killing all 124 people on board.

1967 – Lake Central Airlines Flight 527 crashes near Marseilles, Ohio, killing 38.

1968 – Air France Flight 212 crashes into La Grande Soufrière, killing all 63 aboard.

1970 – The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons goes into effect after ratification by 43 nations.

1973 – An Iberia McDonnell Douglas DC-9 collide in mid-air with a Spantax Convair 990 Coronado over Nantes, France, killing all 68 people abord the DC-9, including music manager Michael Jeffery.

1974 – Yom Kippur War: Israeli forces withdraw from the west bank of the Suez Canal.

1978 – The Landsat 3 is launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

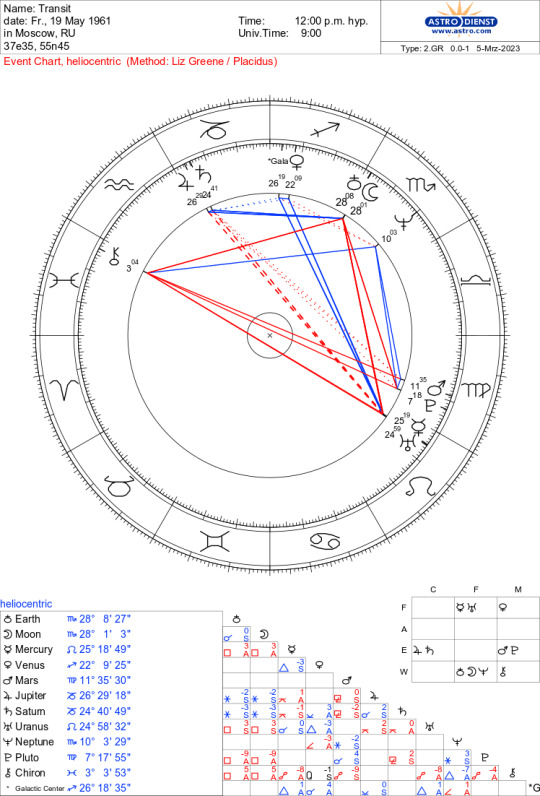

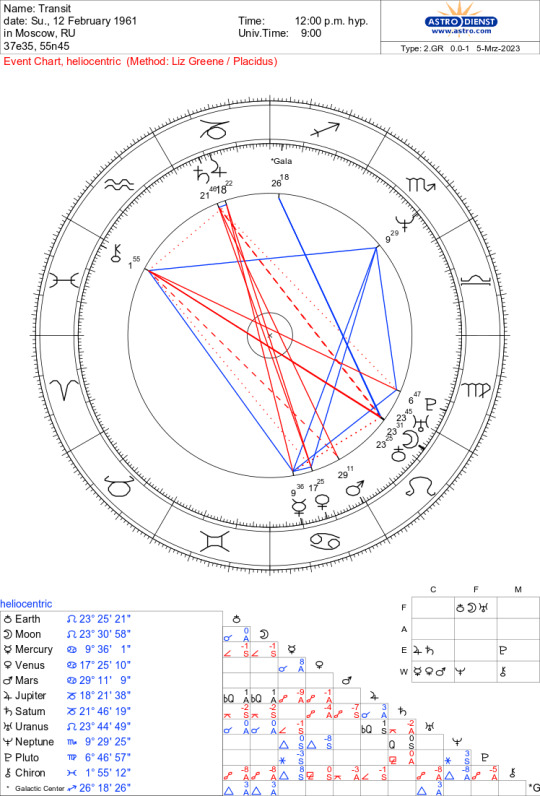

1979 – Soviet probes Venera 11, Venera 12 and the German-American solar satellite Helios II all are hit by "off the scale" gamma rays leading to the discovery of soft gamma repeaters.

1981 – The ZX81, a pioneering British home computer, is launched by Sinclair Research and would go on to sell over 11⁄2 million units around the world.

1982 – Soviet probe Venera 14 lands on Venus.

1991 – Aeropostal Alas de Venezuela Flight 108 crashes in Venezuela, killing 45.

1993 – Palair Macedonian Airlines Flight 301 crashes at Skopje International Airport in Petrovec, North Macedonia, killing 83.

2001 – In Mina, Saudi Arabia, 35 pilgrims are killed in a stampede on the Jamaraat Bridge during the Hajj.

2002 – An earthquake in Mindanao, Philippines, kills 15 people and injures more than 100.

2003 – In Haifa, 17 Israeli civilians are killed in the Haifa bus 37 suicide bombing.

2011 – An Antonov An-148 crashes in Russia's Alexeyevsky District, Belgorod Oblast during a test flight, killing all seven aboard.

2012 – Tropical Storm Irina kills over 75 as it passes through Madagascar.

2012 – Two people are killed and six more are injured in a shooting at a hair Salon in Bucharest, Romania.

2018 – Syrian civil war: The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) pause the Deir ez-Zor campaign due to the Turkish-led invasion of Afrin.

2021 – Pope Francis begins a historical visit to Iraq amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

2021 – Twenty people are killed and 30 injured in a suicide car bombing in Mogadishu, Somalia.

2023 – The 2023 Estonian parliamentary election is held, with two centre-right liberal parties gaining an absolute majority for the first time.

2023 – A group of four prisoners escape from the Nouakchott Civil Prison, before being caught the next day.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Honestly we as a society should talk more about the '78 - '83 Venera probes the Soviets sent to Venus. It's not only a huge achievement, not only the only images of another planet's surface we had for two decades, but it's also just a wild story in general of repeated partial failures that the soviet space program just wouldn't accept. It's a wild tale of a space program both being too fast and loose with science and million dollar equipment, but also pure tenacity to not allow equipment failures that still bore fruit to stop a frenzied attempt to get full findings. Other people would've looked at equipment failure that still took partial photos and said, 'that's enough for us', but they just refused again and again until they had that full picture with no failures.

#I wish programs still had this tenacity and drive for success and exporation#but it's also a wild story of absolute incompetent and reckless spending and engineering#but y'know#anyway#Venus#Space Exploration

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Voyager, Juno, Viking, Venera, Huygens, Curiosity, Philae Lander, New Horizons, Pioneer, and Ingenuity: These extraordinary spacecraft are a testament to our pursuit of knowledge and exploration beyond the confines of our home planet. And this holographic-style sticker pack celebrates each of them.

I'm also quit fond of Kepler, Hubble, and JWST. ✨🛰✨

Get 17% off with code: TKSST

Get this sticker pack

#space#science#technology#Science and Technology#teens#grown ups#2023#party favors#amazon alternatives#history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok sorry to keep talking about that stupid image but. they’re including Gemini, the Redstone rocket, and the Atlas rocket too i think on the US side. all they gave the USSR was the fucking LK lander and the N1, they didn’t include Vostok, Sputnik, Mir, Soyuz, any of the Luna probes, Venera, none of that

just the two failures the program had in the late 60s

#my posts#sorry I know it’s just an idiot on the internet but god it makes me angry when people go USA NUMBER ONE BOOTPRINTS ON THE MOON WOOOO#like shove it

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I guess there's some buzz about the OceanGate CEO wanting to make a floating colony on Venus, and a lot of people are (rightfully) pointing out what a waste of resources this is.

But the concept of a cloud city there goes way back and there are some compelling reasons for that.

Venus' surface is hot: 475 C or 900 F depending on your measurement system of choice. This heat creates a shit ton of pressure (well, 75 atmospheres specifically) as well. The longest lasting probe we sent was the Soviet Union's Venera 13, which lasted for 127 minutes before being crushed and melted. It sent back color photos, by the way.

So, the surface is clearly a no-go. But that high pressure and the makeup of the atmosphere (mostly CO2, tiny amount of oxygen and actually a decent amount of nitrogen) means that breathable air would act as a lifting gas, like hydrogen or helium on Earth.

On top of that, around 55 km above the surface, the atmosphere's pressure, temperature, and gravity is very similar to that on Earth's surface! Its cloud cover reflects much of the solar radiation that hits it and absorbs a lot of what's left (Earth is protected by a magnetic field) A cloud city there... would actually be pretty ideal. I wouldn't necessarily want to be living in one if a storm hit, but that's a surmountable problem (something something handwave handwave). This is actually a more hospitable environment than Mars, which is quite cold most of the time and the atmosphere is so thin any habitat would need to be very pressurized. Mars doesn't have a magnetosphere to protect it, so its surface is bombarded by solar radiation. Mars also has about a third the gravity of Earth, which could present some significant problems for a colony's longevity because we don't even know if people can carry a pregnancy in lower gravity.

This isn't to say Venus doesn't have issues. First, we still haven't figured out how to maintain a closed, self sufficient ecosystem for any length of time. The ISS relies on a steady supply of resources from Earth. On Venus, this is actually worse than Mars because of something called deltaV. Long story short, to get to Venus from Earth is more expensive in terms of deltaV, and by extension expensive in terms of fuel, and expensive in terms of construction of your craft (because every. single. kilogram. matters in space), than it is to get to Mars.

Second, Venus' atmosphere isn't just toxic: it's corrosive. It's gonna pop your balloons. It's gonna burst your bubble, Guillermo. There may be a solution to this one day, but wow I wouldn't bet 1 life on it let alone the 1,000 Söhnlein wants to send.

One last point in Venus' favor, because this kind of thing is my Special Interest and I like talking about it, is logistical. Optimal transfer windows (times it's good to send a rocket somewhere else) open up from Venus pretty often. On top of that, the deltaV from Venus to anywhere else is lower than from Earth. And it has a lot of nitrogen, which you really need if you want to cultivate agriculture elsewhere in the Solar System not Earth. It would be one of its biggest exports. So we probably have not heard the last of Venus colonies, even if it's a long shot and spearheaded by people who think safety regulations are a suggestion (hate hate hate hate hate that btw).

I only hope if they do send people there, Söhnlein has the guts to go himself. By 2050 Venus will have the opportunity to do the funniest thing a planet's ever done.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

NEW FROM FINISHING LINE PRESS: Soviets on Venus by Thomas Simmons

ADVANCE ORDER: https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/soviets-on-venus-by-thomas-simmons/

#Soviets on #Venus explores a remote jeweled casket. It construes an alien neighbor as it reconceptualizes an underrated scientific breakthrough: the series of unnamed probes piloted to #Venus by the #USSR between 1961 and the mid-80’s. The missions were called the Venera program. These fantastical spacecraft transmitted data, vivid photographs, and poetic energy back to Earth. Some piloted through the morning star’s magma-hot, swampy atmosphere as balloons. A few smashed themselves into aeolian canyons or upon alien tufa. A handful simply melted away into silvery pools. And several ended in disaster. These fantastic probes form a sediment of verse from which a strange beauty emerges.

PRAISE FOR Soviets on Venus by Thomas Simmons

Only the dexterity of a poet like Simmons could illuminate the tragic furrows where the trauma of socialist politics overtakes legitimate scientific inquiry. There is a revelation here, and a quiet restlessness.

—Gregory Kipp, Geological Engineer

Weaving thoughts and images and historical facts together in a poetry which maintains a sparse lyricism, Simmons’ narrative is not only vastly more entertaining than most prose histories, but it gives the reader a unique advantage to imagine and reimagine the story that is being told.

–Cliff Cunningham, Research Fellow, University of Southern Queensland and author of Asteroids

Is the verse collection Soviets on Venus good or bad? Yes. Find out for yourself!

–Frank Pommersheim, Professor Emeritus, Knudson School of Law and author of Braid of Feathers

Please share/repost #flpauthor #preorder #AwesomeCoverArt #read #poems #literature #poetry #USSR #venus #space

#poetry#preorder#flp authors#flp#poets on tumblr#finishing line press#small press#book cover#books#publishers#poets#poem#smallpress#poems#venus#space science#ussr (former soviet union)

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

During the 1960s, the first robotic explorers began making flybys of Venus, including the Soviet Venera 1 and the Mariner 2 probes. These missions dispelled the popular myth that Venus was shrouded by dense rain clouds and had a tropical environment. Instead, these and subsequent missions revealed an extremely dense atmosphere predominantly composed of carbon dioxide. The few Venera landers that made it to the surface also confirmed that Venus is the hottest planet in the Solar System, with average temperatures of 464 °C (867 °F). These findings drew attention to anthropogenic climate change and the possibility that something similar could happen on Earth. In a recent study, a team of astronomers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) created the world’s first simulation of the entire greenhouse process that can turn a temperate planet suitable for Life into a hellish, hostile one. Their findings revealed that on Earth, a global average temperature rise of just a few tens of degrees (coupled with a slight rise in the Sun’s luminosity) would be sufficient to initiate this phenomenon and render our planet uninhabitable. The study was conducted by Guillaume Chaverot and Emeline Bolmont, a postdoctoral scholar and an Astrophysics Professor with the Observatoire Astronomique de l’Université de Genève (UNIGE) and its Life in the Universe Center (LUC) (respectively). They were joined by Martin Turbet, a research scientist with UNIGE, the Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique (LMD), and the Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux (LAB). The paper that describes their simulation and research findings recently appeared in Astronomy & Astrophysics. Just a few degrees difference in temperature can trigger a runaway greenhouse effect, according to new research. Credit: NASA Triggering the Effect Belmont is the director of the LUC, which leads state-of-the-art interdisciplinary research projects regarding the origins of Life on Earth and other planets. According to the team’s simulations, the key to a runaway greenhouse effect is the water content of an atmosphere. Water vapor prevents solar irradiation absorbed by Earth’s surface from being radiated back to space as thermal radiation, effectively trapping heat in our atmosphere. While a limited greenhouse effect is essential for maintaining stable temperatures and habitability, too much will increase ocean evaporation and (therefore) the level of water vapor in the atmosphere. In previous climatological studies, researchers have focused on either the planet’s conditions before the runaway greenhouse effect or its inhabitable state after the runaway occurred. What Chaverot and his colleagues did was create the first-ever 3D global climate model that examines the transition itself and how the climate and the atmosphere evolve during that process. One of the key points in this transition involves the appearance of a specific cloud pattern that increases the runaway effect and makes the process irreversible. Based on their new climate models, the team determined that a very small increase in solar irradiation, causing an average global temperature increase of a few tens of degrees, would be enough to trigger this irreversible runaway greenhouse effect on Earth. As Chaverot explained in a UNIGE press release: “There is a critical threshold for this amount of water vapor, beyond which the planet cannot cool down anymore. From there, everything gets carried away until the oceans end up getting fully evaporated and the temperature reaches several hundred degrees.” “From the start of the transition, we can observe some very dense clouds developing in the high atmosphere. Actually, the latter does not display anymore the temperature inversion characteristic of the Earth atmosphere and separating its two main layers: the troposphere and the stratosphere. The structure of the atmosphere is deeply altered.” Comparison of the dayside temperature of TRAPPIST-1 b as measured using Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), based on computer models. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech Implications for Exoplanets This discovery of this specific cloud pattern could prove very useful for exoplanet researchers. In recent years, the field has transitioned from the discovery process to characterization, where astronomers rely on transit spectra and direct imaging to determine the chemical composition of exoplanet atmospheres – thus allowing them to place tighter constraints on their habitability. By identifying this cloud pattern in exoplanet atmospheres, astronomers could identify those that are about to experience a runaway greenhouse effect. “By studying the climate on other planets, one of our strongest motivations is to determine their potential to host Life. After the previous studies, we suspected already the existence of a water vapor threshold, but the appearance of this cloud pattern is a real surprise!” Said Blomont. “We have also studied in parallel how this cloud pattern could create a specific signature, or ‘‘fingerprint’’, detectable when observing exoplanet atmospheres. The upcoming generation of instruments should be able to detect it,” added Turbet. Chaverot and his colleagues recently received a research grant to continue this study at the Institut de Planétologie et d’Astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG). As per this grant, they will focus on how a runaway greenhouse effect could happen here on Earth. Implications for Climate Mitigation One of the main points stressed in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change‘s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report is the need to curb greenhouse gas emissions to limit the average global temperature increase to 1.5 °C by 2050. With their new grant, Chaverot and his team will assess whether greenhouse gases can trigger the runaway process in the same way a slight increase in solar luminosity would. If so, then it is absolutely crucial to determine what the threshold is so the IPCC and environmental organizations worldwide can establish a red line that cannot be crossed. As Chaverot concludes: “Assuming this runaway process would be started on Earth, an evaporation of only 10 meters of the oceans’ surface would lead to a 1 bar increase of the atmospheric pressure at ground level. In just a few hundred years, we would reach a ground temperature of over 500°C. Later, we would even reach 273 bars of surface pressure and over 1,500°C, when all of the oceans would end up totally evaporated.” So the good news is that our planet will not become a hellish landscape any time soon, at least not by an increase in our Sun’s luminosity. Whether or not we affect that change (assuming it is possible) remains to be seen. Further Reading: EurekAlert!, Astronomy & Astrophysics The post It Doesn't Take Much to Get a Runaway Greenhouse Effect appeared first on Universe Today.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Estudio para Combina Orbital #2- ECO#2 (Study for Orbital Combine #2 - SOC#2) 2023, Malanga plant gathered from the Puerto Rican rain forest, ABS plastic, wood, plywood, PVC plastic, steel, rubber hosing, vinyl hosing, enamel paint, casters, various electronics, 3gal water container, 114” X 51” x 34” inches.

Estudio para Combina Orbital #2- ECO#2 is the product of a post- geographical daydream and an object that I first thought of in 2011. It is the second iteration of a speculative structure that I first imagined as an untethered spar oil rig. Its upper superstructure replaced with a small tropical rainforest full of fruits while its main lower cylinder would contain living spaces and workshops for the DIY inventors and engineers that will inhabit it. In time, this free-floating island would be joined by other, similar human-made islands in the hopes of creating a self-sufficient nomadic archipelago.

As this basic concept slowly drifted in my head for 8 years it's DNA gradually spliced itself with that of space exploration probes. In this second version I was heavily inspired by the configuration/shape of the MIR space station and other Soviet spacecraft like the Zond 1 and Venera 4.

ECO#2 contains a small Malanga plant that I gathered from my family’s coffee farm in the town of Lares, Puerto Rico. I mailed this plant to myself in Roswell, New Mexico against USDA rules.

This act of contraband is to me a gesture of political disobedience against our colonial rule, and my first step in the terraforming of the mainland US. Just as the US turned its gaze to Central & South America after the success of the westward expansion during the late 19th century, I'll return the gaze from the 21st. This time from the Caribbean - a form of inverted colonialism and a twisted reflection of the Monroe Doctrine.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

https://mesonstars.com/space/venera-13-images-of-the-surface-of-venus/

Venera 13 images of the surface of Venus

The soil of Venus photographed by Venera 13 (USSR)

On March 1, 1982, the Soviet Venera 13 probe sent the image below these lines. She had just landed in the hell of Venus and would die two hours and seven minutes later, rendered useless by the demonic temperatures of the planet. Now, a team of scientists have created an electronic system that would have survived for many months: a radio on a chip that could be vital to the future of our planet.

Apart from several photos and the first sound recorded on a planet in the solar system, the data collected by the Venera 13 probe in those 127 minutes show that it endured a temperature of 457 degrees Celsius while an atmospheric pressure of 89 terrestrial atmospheres crushed it against the surface.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apollo

Doubt thou the stars are fire; Doubt that the sun doth move; Doubt truth to be a liar; But never doubt I love.

William Shakespeare, Hamlet, 1601

The matrimony between statecraft and the conquest of the cosmos birthed the space industry in a concerted effort to seize the final frontier. A triumvirate of government, academia and corporations found common cause in the geopolitics of the Cold War to mobilize minds and machines against the Soviets whose Sputnik orbited the earth by 1957. This shot across the bow of a lone satellite in the outlands of the stars rattled American exceptionalism insofar as policymakers perceived it to be an existential threat over their monopoly of the sciences. The slender orb of 83.6kg evoked paranoia due to how swift the Soviet Union transitioned into a knowledge-based economy. Any robust space industry cultivates a panoply of ancillary sectors from vast spillovers to fabricate composite metals, semiconductors, liquid fuels and other things of this ilk. Prima facie the coup was prodigious by itself but the infrastructure behind it left Washington reeling. Manifestly the communists confirmed themselves to be lightyears ahead of their counterparts in the research of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). The postwar propaganda value of boasting the know-how of rocketry to escape earth’s gravity rallied brains and brawn around the flag in a species of a Manhattan Project redux.

In the infancy of the space derby the torrent of Soviet victories intensified rivalries in the bipolar world. The canine Laika became the first mammal to voyage the ether in 1957. Luna 2 probed the Moon’s surface on the maiden trip of its kind in 1959. Luna 3 purveyed to the world its first glimpse of the far side of the Moon in 1959. Venera 1 established a record as the first interplanetary vehicle to effect a flyby of Venus in 1961. Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin followed suit by entering the firmament as the first human in 1961. Cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova defied gender norms as the first woman to orbit earth in 1963. Cosmonaut Alexei Leonov partook in the first spacewalk in 1965. Mars 3 captured immortality as the first manmade craft to land on the Martian planet in 1971. The string of triumphs and their rapid succession aroused awe and dread on terra firma amongst the cognoscenti in the Beltway. Such a truncated turnaround from the ravages of WWII called into question whether in fact the communist model of governance was indeed leaps and bounds ahead of free market capitalism. The gulf of a knowledge gap that differentiated the Soviet space program from the amorphous one in America left skeptics of the former agog. For a time the legion of scientists under the auspices of the politburo’s central planning seemed omniscient.

Such centralization of the bureaucracy unmolested by partisanship or a farrago of stakeholders created small skunkworks under the nomenclature of OKBs wherein discoveries were made at the cadence of a metronome. Not at all enigmatic in retrospect this quantum leap also stemmed from its piracy that was more rapacious than America’s. Whereas Washington acquired intellectual assets via Operation Paperclip the Soviet’s variant of Osoaviakhim in 1946 conscripted a whole brigade of German minds to catapult space exploration. Wernher von Braun and a cohort of his scientists from Peenemünde were spirited away to Washington whilst Moscow’s dragnet repatriated exponentially more in human capital and technology (Neufeld 2004). The poaching of knowledge midwifed the series of records monopolized by the superpower in the incipient years of the space race. The spoils of war from German heuristics wedded to indigenous capabilities proved to be a boon for the Soviets who were keen to parade the merits of communism. Indeed the Kremlin’s industrial complex revolutionized space travel for the sake of ideological warfare against its nemesis. The disparities were quite vast. America’s Project Mercury sought to put an astronaut in orbit as the Soviet’s Luna missions were already plumbing the Moon in 1959.

In the prelude to the moonshot of Apollo the saga of America’s space industry begins with the importation of V-2 rockets from the Nazi regime which whetted the enthusiasm for escaping earth’s gravity. Under Project Hermes the autopsy on these missiles saw the technology reverse engineered in an effort to breach the Karman Line of the upper atmosphere. A whole 300 boxcars of miscellaneous V-2 hardware smuggled from Germany made their way to the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico where 67 units were reassembled between 1946 and 1951 (Buchanan et al. 1984). Telemetry data from subsequent tests telescoped the learning curve to spur the development for Apollo’s workhorse known as the Saturn V rocket whose pedigree veritably traces back to the V-2s. At this early juncture it was the firm General Electric with which Washington rendezvoused so as to scrutinize these artifacts for their ballistics and gyrostabilized guidance systems. A constellation of scientists were contracted to harvest the secrets hidden within the entrails of the V-2s in a bid to marshal propulsion and re-entry technologies into maturity. Borne from this fact-finding mission did GE design avionics that later computed the terabytes of data for the Apollo moonshot. The firm would be the first embraced in the bosom of the space program.

Post the industrial policy of this public-private partnership the space industry sired the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as its guardian in 1958. The institution’s formation heralded a departure from space’s militarization towards its exploration to demystify the mysteries of the cosmos. The separate track charted a course to the stars for civilian ends at variance with the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) that put a premium on technology for martial use. Founded fourth months prior to NASA this other agency’s mandate was written in rebuttal to the USSR’s launch of Sputnik. Within this bifurcation the raison-d’être for each hinged on war in the case of DARPA and peace in the case of NASA. The civilian program’s prime directive as distilled in section 102 of the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 empowered the institution to one end alone of making America a leader in the Olympics of science. NASA wasted no time in engineering a stepwise roadmap between the triad of Projects Mercury, Gemini and Apollo in this chronological order. Each unique phase rested along a spectrum in the mastery of technology beginning with a manned craft in space to orbital docking and finally a lunar expedition. NASA summarily evolved into a hive of innovation.

After GE’s forensics upon reconstituting the hodgepodge of V-2 rocket paraphernalia amidst Project Hermes the next private firms entrusted with reifying America’s curiosity with outer space were Chrysler and McDonnell Aircraft. Industrial policy shovelled $277m or $2.9t in real value for its pecuniary commitment towards the first phase christened Project Mercury (DiLisi et al. 2019). The industrial heritage of Chrysler hitherto as a marque of Plymouths and Dodges appears paradoxical for such high-tolerance engineering but the firm proved its poise in WWII when it mass-produced 25,000 M4 Sherman Tanks (Davis 2007). To segue into this highbrow application the company collaborated with the prodigy von Braun who was the doyen of rocket science. Chrysler would be the proverbial blacksmith for the single-stage Redstone booster whose propulsion from 78,000 pounds of thrust bore astronaut Alan Shepard into suborbital space in 1961 (Bentley 2009). It fell to McDonnell Aircraft to manufacture the spacecraft itself meant to house the life support systems for a solitary occupant in the antipodes of space. Everything from the heat-shield for re-entry to the escape system that jettisoned the capsule with a parachute should the mission be aborted in the event of a catastrophic failure was designed by the firm.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Venera program: Interplanetary probes from behind the Iron Curtain

The Pioneer and Voyager probes the United States sent to explore the outer planets in the 1970s are often, and accurately, lauded as historic interplanetary achievements. That’s partly because, equipped with the Pioneer Plaque and the Voyager Golden Record, these objects are ostensibly meant to be found by aliens someday, helping them easily burrow into public consciousness. Similarly, robotic explorers to Mars, including the Viking landers and the Sojourner, Spirit, Opportunity, and Curiosity rovers, take innumerable headlines, and they’re often even given anthropomorphized personalities.

Almost forgotten, however, are the ambitious Soviet exploration missions of Venus. Beginning at the dawn of the Space Age in the late 1950s, the Soviets worked to design and construct a series of Venus probes. And for almost 30 years, they built and flew the interplanetary spacecraft as part of the Venera program — carrying out rather impressive feats, even by today’s standards.

In the early 1960s, the Cold War was in full swing and the Space Race was on. The Soviets were eager to notch as many “firsts” as they could in all realms of spaceflight. At that time, they had a better heavy-lifting capability than the United States. This allowed them to build and launch larger spacecraft, both manned and unmanned. And by using four-stage rockets and an advanced telemetry system, the Soviets could also mount missions to the difficult-to-reach inner planets.

Venera 1, the first probe in the series of Soviet Venus missions, weighed in at an impressive 1,400 pounds (at just 184 pounds, the first satellite, Sputnik 1, was a mere featherweight in comparison). Somewhat resembling a Dalek from Doctor Who, the Venera 1 probe was spin stabilized and packed with instruments, including a magnetometer, Geiger counters, and micrometeorite detectors. And like many of its successors, the interior of the probe was pressurized to just over one atmosphere with nitrogen gas to help the instruments function at a stable temperature.

However, the first Venera 1 probe never made it out of Earth orbit. And the second attempt, launched February 12, 1961, failed en route to Venus, though it did pass within about 62,000 miles (100,000 kilometers) of the planet.

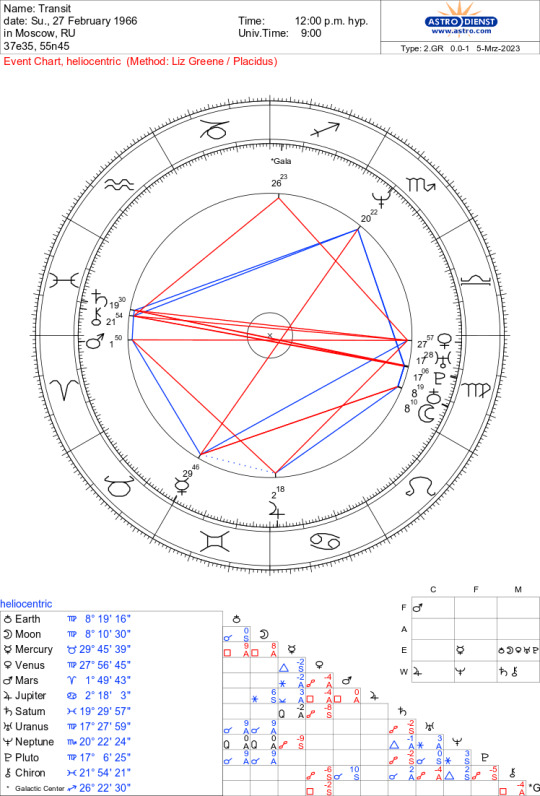

Venera 2, which greatly resembled Venera 1, was built to fly past Venus, during which it would record information and transmit it back to Earth. And the probe did complete its flyby on February 27, 1966, coming within about 15,000 miles (24,000 km), but it also overheated and was never heard from again. It’s still unclear whether Venera 2 failed before or after it zipped by the distant world.

The Soviets designed the next four probes, Venera 3 through 6, to more closely study the atmosphere of our hellish neighbor. Generally weighing about 2,000 pounds (900 kilograms) each, these probes contained a suite of instruments and a detachable pod (known as a descent module) equipped with a second collection of devices that included a barometer, a radar altimeter, gas analyzers, and thermometers. Not all of these probes ended in success, though.

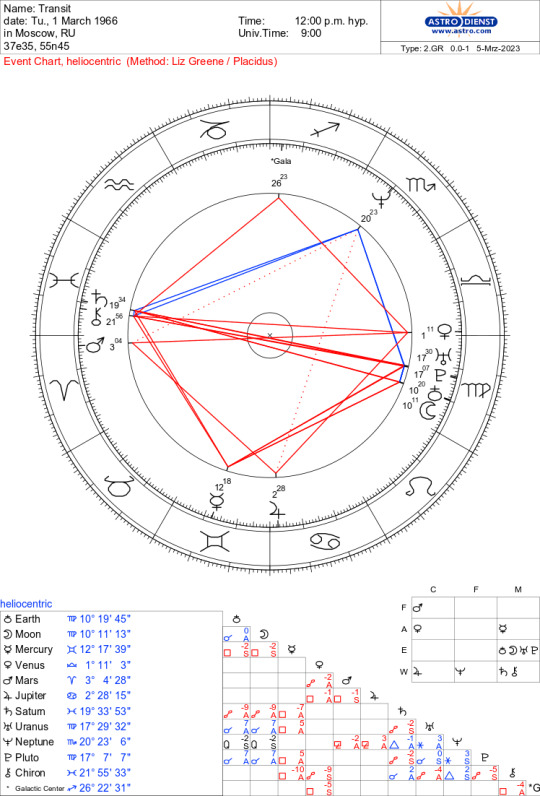

Venera 3 planned to land on the venusian surface, but it instead slammed into it on March 1, 1966 — officially making it the first spacecraft to crash into another planet.

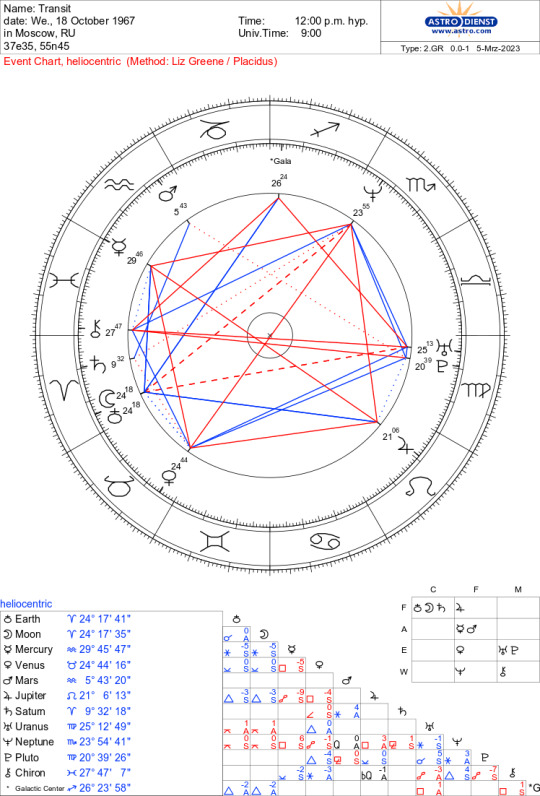

Venera 4, however, spent more than 90 minutes taking measurements as it slowly floated down through the dense atmosphere of Venus on October 18, 1967. It also detected very elevated levels of carbon dioxide in the air, as well as a lack of a global magnetic field. And as expected, it eventually succumbed to the planet’s intense heat and pressure.

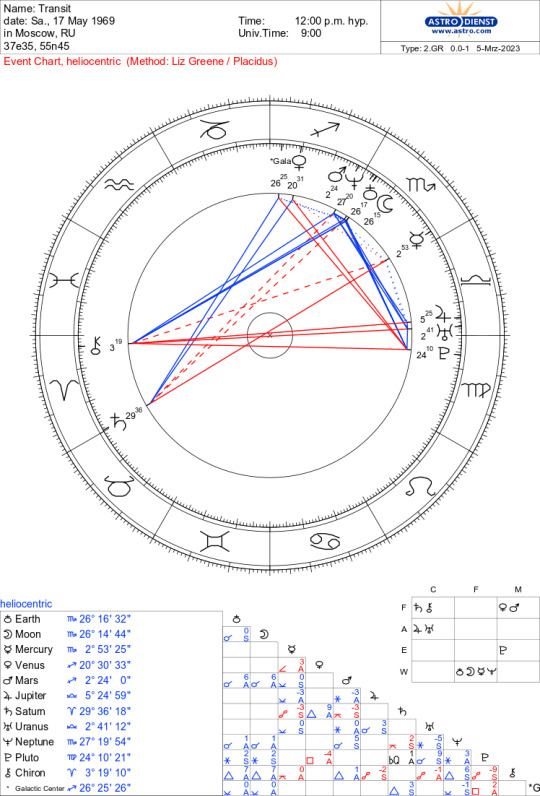

Both Venera 5 and Venera 6 were likewise successes, transmitting back data for more than 50 minutes as they parachuted through the atmosphere of Venus on May 16 and May 17, 1969. By helping scientists further characterize the atmospheric composition of world, these probes made it clear that Venus is highly unlikely to host life; romantic hopes of Venus as an earthly paradise were dashed.

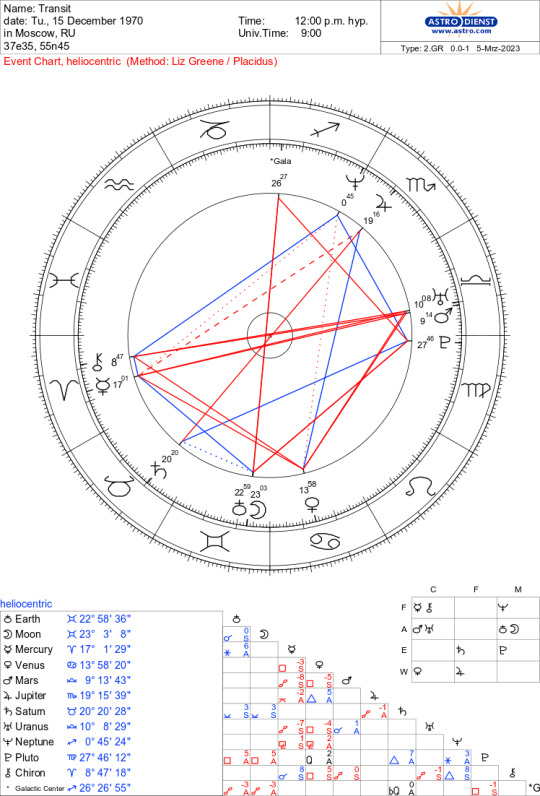

Venera 7 included an even more ambitious descent module designed to make a soft landing on Venus, which included heavy fortifications so it could briefly survive the inhospitable conditions on the surface. Launched August 17, 1970, the flight was a success of sorts. The lander made it to the surface on December 15, 1970, but it got there after its parachute ripped, causing it to fall faster than planned for nearly 30 minutes before smacking into the surface at about 38 miles per hour (61 km/h).

Initially thought to have failed, Venera 7 did manage to transmit meaningful data for a short period of time. For example, the lander measured a surface temperature of almost 900 degrees Fahrenheit (475 Celsius), or about as hot as a brick pizza oven. Although the probe’s pressure sensor failed during descent, researchers were able to use its measurements to estimate a surface pressure of about 92 bars, which is about what you would experience if you were more than a half mile (900 meters) underwater.

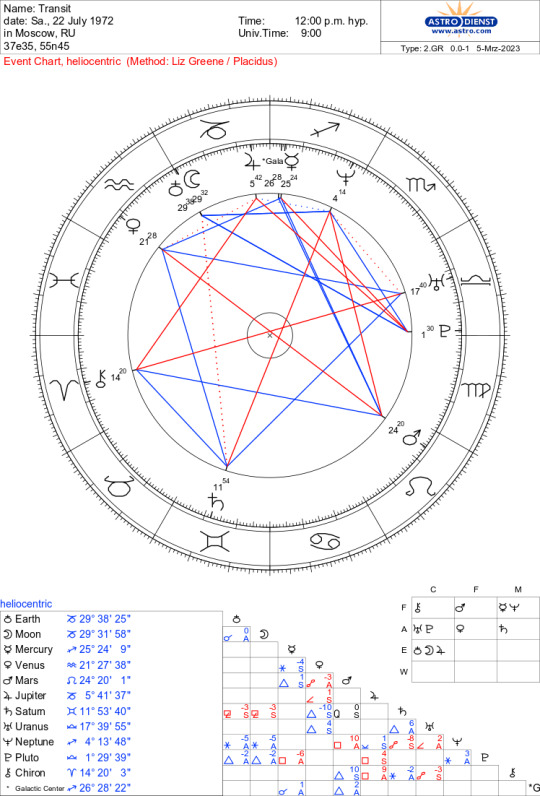

Venera 8 repeated much of the Venera 7 mission, albeit without its lander falling over when it reached the surface of Venus on July 22, 1972. Venera 8’s functioning pressure sensor confirmed Venus’ oppressive atmosphere, but it also took measurements of ambient light levels on the surface, confirming that future cameras should be able to capture the venusian sights.

Of all the Soviet missions to Venus, Venera 9 through Venera 12, weighing roughly 11,000 pounds (5,000 kg) each, are the best remembered to this day. That’s mainly because their landers carried cameras that could directly image the surface.

Venturing to Venus between 1975 and 1978, several of the cameras on these probes failed, usually due to their lens caps not coming off. But nonetheless, a few managed to take and transmit the very first images from the surface of our solar system’s second planet.

The early snapshots obtained by Venera 9 and Venera 10 are haunting. Crisp, clear, and spherically distorted by their wide-angle lenses, they depict a harsh and rocky alien landscape extending out to the horizon. But the images also managed to capture the edges of the landers themselves, which reveals their distinctly Soviet design.

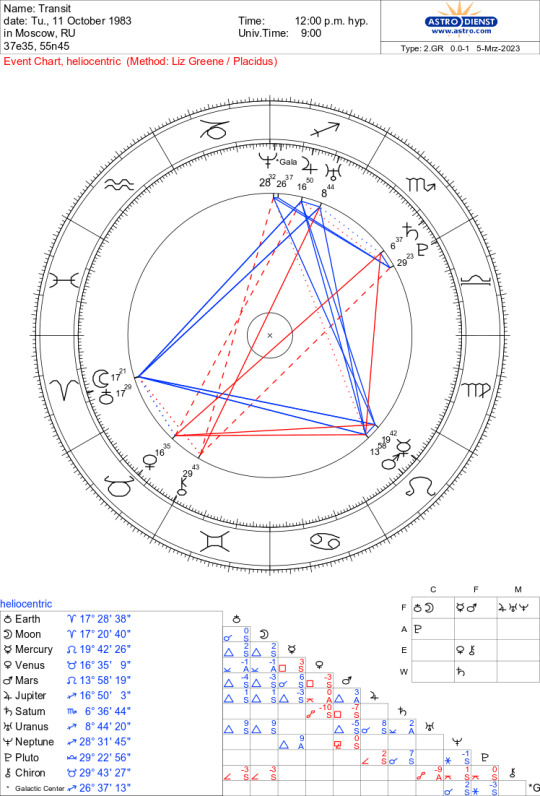

Venera 13 and Venera 14, both launched in 1981, were more advanced versions of the Venera 9 through 12 probes, carrying landers equipped with sophisticated acoustic devices that could tune in to the Venusian wind to gauge its speed.

Venera 15 and Venera 16, each weighing just under 9,000 pounds (4,100 kg), did not carry landers. In their place they brought highly advanced radar-based imaging systems that could map the blistering world from elliptical orbits. The Pioneer 12 probe may have been first to map Venus using radar, but Venera 15 and 16 did it better, reaching a resolution of about a mile (1 to 2 km) per pixel. The images returned by these probes were fantastically detailed, revealing broad swaths of the harsh landscape, complete with impact craters, dramatic rises, and lava-flooded basins.

The U.S. made its mark on the exploration of Venus through missions like Pioneer 12 and the wildly successful Magellan, and other craft sent by the European and Japanese Space Agencies also contributed to our understanding of our planetary neighbor next door. Still, the Soviet Venera program remains the most intense and sustained series of missions to Venus yet.

And at least for now, that doesn’t look like it’s going to change soon.

0 notes