#Laboratory for Nuclear Science

Text

Ronald Garcia Ruiz named a Popular Science “Brilliant 10”

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/ronald-garcia-ruiz-named-a-popular-science-brilliant-10/

Ronald Garcia Ruiz named a Popular Science “Brilliant 10”

Popular Science magazine has named Ronald Fernando Garcia Ruiz, assistant professor with MIT’s Department of Physics and a researcher in the Laboratory for Nuclear Science, as one of its Brilliant 10 for 2023.

Garcia Ruiz is featured in the Dec. 5 issue.

The Garcia Ruiz Lab (the Laboratory for Exotic Molecules and Atoms) focuses its research on the development of laser spectroscopy techniques to investigate the properties of subatomic particles using atoms and molecules made up of short-lived radioactive nuclei. Garcia Ruiz’s experimental work provides unique information about the fundamental forces of nature, the properties of nuclear matter at the limits of existence, and the search for new physics beyond the Standard Model of particle physics.

Garcia Ruiz obtained his bachelor’s degree in physics at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, a master’s degree in physics at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, and his PhD degree at KU Leuven in Belgium. Garcia Ruiz was based at CERN during most of his PhD, working on laser spectroscopy techniques for the study of short-lived atomic nuclei. After his PhD, he became a research associate at The University of Manchester. In 2018, he was awarded a CERN Research Fellowship to lead the local team of the Collinear Resonance Ionization Spectroscopy experiment. At CERN, he has led several experimental programs motivated by modern developments in nuclear science.

Garcia Ruiz joined the MIT faculty in 2020. Over the last few years, his team and collaborators developed the Resonance Ionization Spectroscopy Experiment (RISE) at the new U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Facility for Rare Isotope Beams. This unique facility worldwide will facilitate the study of rare atoms and molecules containing nuclei with extreme proton-to-neutron ratios, enabling new opportunities in the study of nuclear matter and searches for new physics.

Garcia Ruiz and his collaborators have pioneered the study of radioactive molecules for the investigation of nuclear and particle physics phenomena. In particular, radioactive molecules with octupole-deformed nuclei are predicted to offer unprecedented sensitivity to study the violation of the fundamental symmetries that are suggested to play a critical role in the origin and evolution of our visible universe.

Among his previous honors and awards, Garcia Ruiz received a Sloan Research Fellowship 2023, the Stuart Jay Freedman Award in Experimental Nuclear Physics from the American Physical Society in 2022, the IUPAP Young Scientist Prize in Nuclear Physics 2022, the National Academic Award in Science, Alejandro Angel Escobar Prize, Colombia in 2021, and the DOE Early Career Award 2020.

The 10 awardees, chosen from hundreds of nominations, are reviewed by peers in the field. Popular Science’s annual Brilliant 10 list was first published in 2002. Eight other MIT researchers have received this distinction since the list’s inception.

#2022#2023#atomic#atomic nuclei#atoms#Awards#honors and fellowships#career#development#Developments#energy#Evolution#experimental#Faculty#Featured#Fundamental#isotope#Laboratory for Nuclear Science#laser#LED#list#matter#mit#model#molecules#nature#neutron#nuclear#Nuclear physics#nuclear science

0 notes

Text

Brookhaven Graphite Research Reactor, New York, active from 1950 to 1968. (Flickr)

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Large Hadron Collider (LHC)

#Large Hadron Collider#lhc#photography#particle collider#CERN#European Organization for Nuclear Research#Nuclear Research#tunnel#france#Switzerland#geneva#Higgs boson#science#energy#colored#laboratory#colors

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

#nuclear symbol#garden bros nuclear circus#effective nuclear charge trend#naval nuclear laboratory#watts bar nuclear plant#nuclear power plants in nc#nuclear power plant nj#national museum of nuclear science & history#united nuclear#b83 nuclear bomb#north anna nuclear power plant#nuclear lamina#nuclear pore#nuclear sclerosis in dogs#mcguire nuclear station#nuclear cataract#nuclear wasabi#nuclear explosion gif#comanche peak nuclear power plant#oconee nuclear station#nuclear power plants in south carolina#nuclear sign#nucular vs nuclear#bomba nuclear#nuclear circus#which molecules do not normally cross the nuclear membrane?#calvert cliffs nuclear power plant#grand gulf nuclear station#nuclear physicist salary#nuclear medicine technologist jobs

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the beginning of the thirties, during the same period in which politics had so brutally invaded the quiet world of the laboratories, nuclear science also knocked at the door of politics.

"Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists" - Robert Jungk, translated by James Cleugh

#book quotes#brighter than a thousand suns#robert jungk#james cleugh#nonfiction#30s#1930s#politics#laboratory#nuclear science

0 notes

Link

Operating the whole project still took more energy and it was all very expensive to boot, so there's still a long way to go before we're all roasting our fusion burgers, but the results "exceeded expectations," and "advances in recent years mean the technology is likely to be widely used in 'a few decades' rather than 50 or 60 years as previously expected."

#government and politics#fusion#physics#particle physics#science#Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory#us government#nuclear physics#lasers

0 notes

Photo

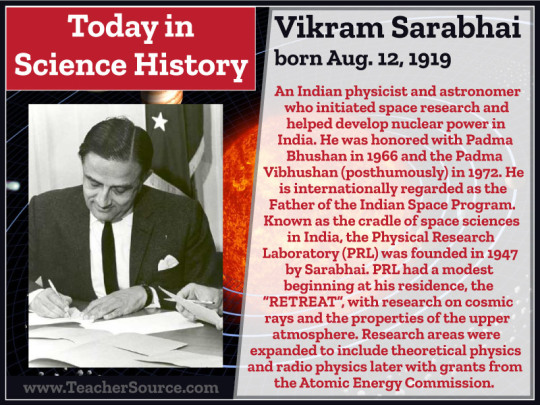

Vikram Sarabhai was born on August 12, 1919. An Indian physicist and astronomer who initiated space research and helped develop nuclear power in India. He was honored with Padma Bhushan in 1966 and the Padma Vibhushan (posthumously) in 1972. He is internationally regarded as the Father of the Indian Space Program. Known as the cradle of space sciences in India, the Physical Research Laboratory (PRL) was founded in 1947 by Sarabhai. PRL had a modest beginning at his residence, the “RETREAT”, with research on cosmic rays and the properties of the upper atmosphere. Research areas were expanded to include theoretical physics and radio physics later with grants from the Atomic Energy Commission.

#vikram sarabhai#physics#astronomy#indian space program#physical research laboratory#PRL#nuclear power#science#science birthdays#science history#on this day#on this day in science history

1 note

·

View note

Text

More favourite mad science tropes:

Flashy explosions as a result of errors in procedures that have no conceivable reason to involve any explosive substance

Lab coats in non-laboratory settings

All mad scientists being versed in mad psychology regardless of their ostensible mad field of study

“It comes to life and starts eating people” being a potential failure mode of literally every experiment

WIldly unethical ways of accomplishing goal that could have been achieved more easily without the crimes against humanity

[noun] reaction/inversion/overload, where [noun] is something that one would not customarily regard as being capable of reacting/inverting/overloading

The way that you can pinpoint the popular anxieties of the era of the story’s publication by looking at the form factor of the thing that turns people into face-eating monsters (e.g., weird potion versus nuclear radiation versus psychiatric fuckery, etc.)

QuAnTum

World-ending superweapons that are also people even though being a person has no bearing on the world-ending part

“What in God’s name?” “God had nothing to do with it!”

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

NASA's delayed Dragonfly drone mission to Saturn's largest moon Titan is on track to launch in July 2028, the space agency confirmed late Tuesday (April 16).

The highly anticipated decision greenlights the mission team to proceed to final mission design and testing in preparation for the revised launch date.

The car-sized Dragonfly, which is being built by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, will reach Titan in 2034. For the next 2.5 years, the nuclear-powered drone is expected to perform one hop every Titan day — 16 days to us Earthlings — hunting for prebiotic chemical processes at various pre-selected locations on the frigid moon, which is known to contain organic materials.

Continue Reading.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

imperialism and science reading list

edited: by popular demand, now with much longer list of books

Of course Katherine McKittrick and Kathryn Yusoff.

People like Achille Mbembe, Pratik Chakrabarti, Rohan Deb Roy, Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, and Elizabeth Povinelli have written some “classics” and they track the history/historiography of US/European scientific institutions and their origins in extraction, plantations, race/slavery, etc.

Two articles I’d recommend as a summary/primer:

Zaheer Baber. “The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge.” Journal of Contemporary Asia. May 2016.

Kathryn Yusoff. “The Inhumanities.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 2020.

Then probably:

Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Colette Le Petitcorps. “Introduction: Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times.” Global Plantations in the Modern World: Sovereignties, Ecologies, Afterlives. 2023.

Sharae Deckard. “Paradise Discourse, Imperialism, and Globalization: Exploiting Eden.” 2010. (Chornological overview of development of knowledge/institutions in relationship with race, slavery, profit as European empires encountered new lands and peoples.)

Gregg Mitman. “Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia’s Plantation Economy.” Environmental History. 2017, (Interesting case study. US corporations were building fruit plantations in Latin America and rubber plantations in West Africa during the 1920s. Medical doctors, researchers, and academics made a strong alliance these corporations to advance their careers and solidify their institutions. By 1914, the director of Harvard’s Department of Tropical Medicine was also simultaneously the director of the Laboratories of the Hospitals of the United Fruit Company, which infamously and brutally occupied Central America. This same Harvard doctor was also a shareholder in rubber plantations, and had a close personal relationship with the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, which occupied West Africa.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Globalizing the Routes of Breadfruit and Other Bounties.” 2008. (Case study of how British wealth and industrial development built on botany. Examines Joseph Banks; Kew Gardens; breadfruit; British fear of labor revolts; and the simultaneous colonizing of the Caribbean and the South Pacific.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Satellite Planetarity and the Ends of the Earth.” 2014. (Indigenous knowledge systems; “nuclear colonialism”; US empire in the Pacific; space/satellites; the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.)

Fahim Amir. “Cloudy Swords.” e-flux Journal #115, February 2021. (”Pest control”; termites; mosquitoes; fear of malaria and other diseases during German colonization of Africa and US occupations of Panama and the wider Caribbean; origins of some US institutions and the evolution of these institutions into colonial, nationalist, and then NGO forms over twentieth century.)

Some of the earlier generalist classic books that explicitly looked at science as a weapon of empires:

Schiebinger’s Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World; Delbourgo’s and Dew’s Science and Empire in the Atlantic World; the anthology Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World; Canzares-Esquerra’s Nature, Empire, and Nation: Explorations of the History of Science in the Iberian World.

One of the quintessential case studies of science in the service of empire is the British pursuit of quinine and the inoculation of their soldiers and colonial administrators to safeguard against malaria in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia at the height of their power. But there are so many other exemplary cases: Britain trying to domesticate and transplant breadfruit from the South Pacific to the Caribbean to feed laborers to prevent slave uprisings during the age of the Haitian Revolution. British colonial administrators smuggling knowledge of tea cultivation out of China in order to set up tea plantations in Assam. Eugenics, race science, biological essentialism, etc. in the early twentieth century. With my interests, my little corner of exposure/experience has to do mostly with conceptions of space/place; interspecies/multispecies relationships; borderlands and frontiers; Caribbean; Latin America; islands. So, a lot of these recs are focused there. But someone else would have better recs, especially depending on your interests. For example, Chakrabarti writes about history of medicine/healthcare. Paravisini-Gebert about extinction and Caribbean relationship to animals/landscape. Deb Roy focuses on insects and colonial administration in South Asia. Some scholars focus on the historiography and chronological trajectory of “modernity” or “botany” or “universities/academia,”, while some focus on Early Modern Spain or Victorian Britain or twentieth-century United States by region. With so much to cover, that’s why I’d recommend the articles above, since they’re kinda like overviews.Generally I read more from articles, essays, and anthologies, rather than full-length books.

Some other nice articles:

(On my blog, I’ve got excerpts from all of these articles/essays, if you want to search for or read them.)

Katherine McKittrick. “Dear April: The Aesthetics of Black Miscellanea.” Antipode. First published September 2021.

Katherine McKittrick. “Plantation Futures.” Small Axe. 2013.

Antonio Lafuente and Nuria Valverde. “Linnaean Botany and Spanish Imperial Biopolitics.” A chapter in: Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World. 2004.

Kathleen Susan Murphy. “A Slaving Surgeon’s Collection: The Pursuit of Natural History through the British Slave Trade to Spanish America.” 2019. And also: “The Slave Trade and Natural Science.” In: Oxford Bibliographies in Atlantic History. 2016.

Timothy J. Yamamura. “Fictions of Science, American Orientalism, and the Alien/Asian of Percival Lowell.” 2017.

Elizabeth Bentley. “Between Extinction and Dispossession: A Rhetorical Historiography of the Last Palestinian Crocodile (1870-1935).” 2021.

Pratik Chakrabarti. “Gondwana and the Politics of Deep Past.” Past & Present 242:1. 2019.

Jonathan Saha. “Colonizing elephants: animal agency, undead capital and imperial science in British Burma.” BJHS Themes. British Society for the History of Science. 2017.

Zoe Chadwick. “Perilous plants, botanical monsters, and (reverse) imperialism in fin-de-siecle literature.” The Victorianist: BAVS Postgraduates. 2017.

Dante Furioso: “Sanitary Imperialism.” Jeremy Lee Wolin: “The Finest Immigration Station in the World.” Serubiri Moses. “A Useful Landscape.” Andrew Herscher and Ana Maria Leon. “At the Border of Decolonization.” All from e-flux.

William Voinot-Baron. “Inescapable Temporalities: Chinook Salmon and the Non-Sovereignty of Co-Management in Southwest Alaska.” 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “White ants, empire, and entomo-politics in South Asia.” The Historical Journal. 2 October 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “Introduction: Nonhuman Empires.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 35 (1). May 2015.

Lawrence H. Kessler. “Entomology and Empire: Settler Colonial Science and the Campaign for Hawaiian Annexation.” Arcadia (Spring 2017).

Sasha Litvintseva and Beny Wagner. “Monster as Medium: Experiments in Perception in Early Modern Science and Film.” e-flux. March 2021.

Lesley Green. “The Changing of the Gods of Reason: Cecil John Rhodes, Karoo Fracking, and the Decolonizing of the Anthropocene.” e-flux Journal Issue #65. May 2015.

Martin Mahony. “The Enemy is Nature: Military Machines and Technological Bricolage in Britain’s ‘Great Agricultural Experiment.’“ Environment and Society Portal, Arcadia. Spring 2021.

Anna Boswell. “Anamorphic Ecology, or the Return of the Possum.” 2018. And; “Climates of Change: A Tuatara’s-Eye View.”2020. And: “Settler Sanctuaries and the Stoat-Free State." 2017.

Katherine Arnold. “Hydnora Africana: The ‘Hieroglyphic Key’ to Plant Parasitism.” Journal of the History of Ideas - JHI Blog - Dispatches from the Archives. 21 July 2021.

Helen F. Wilson. “Contact zones: Multispecies scholarship through Imperial Eyes.” Environment and Planning. July 2019.

Tom Brooking and Eric Pawson. “Silences of Grass: Retrieving the Role of Pasture Plants in the Development of New Zealand and the British Empire.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. August 2007.

Kirsten Greer. “Zoogeography and imperial defence: Tracing the contours of the Neactic region in the temperate North Atlantic, 1838-1880s.” Geoforum Volume 65. October 2015. And: “Geopolitics and the Avian Imperial Archive: The Zoogeography of Region-Making in the Nineteenth-Century British Mediterranean.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2013,

Marco Chivalan Carrillo and Silvia Posocco. “Against Extraction in Guatemala: Multispecies Strategies in Vampiric Times.” International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. April 2020.

Laura Rademaker. “60,000 years is not forever: ‘time revolutions’ and Indigenous pasts.” Postcolonial Studies. September 2021.

Paulo Tavares. “The Geological Imperative: On the Political Ecology of the Amazon’s Deep History.” Architecture in the Anthropocene. Edited by Etienne Turpin. 2013.

Kathryn Yusoff. “Geologic Realism: On the Beach of Geologic Time.” Social Text. 2019. And: “The Anthropocene and Geographies of Geopower.” Handbook on the Geographies of Power. 2018. And: “Climates of sight: Mistaken visbilities, mirages and ‘seeing beyond’ in Antarctica.” In: High Places: Cultural Geographies of Mountains, Ice and Science. 2008. And:“Geosocial Formations and the Anthropocene.” 2017. And: “An Interview with Elizabeth Grosz: Geopower, Inhumanism and the Biopolitical.” 2017.

Mara Dicenta. “The Beavercene: Eradication and Settler-Colonialism in Tierra del Fuego.” Arcadia. Spring 2020.

And then here are some books:

Africa as a Living Laboratory: Empire, Development, and the Problem of Scientific Knowledge, 1870-1950 (Helen Tilley, 2011); Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Londa Schiebinger, 2004)

Red Coats and Wild Birds: How Military Ornithologists and Migrant Birds Shaped Empire (Kirsten A. Greer); The Empirical Empire: Spanish Colonial Rule and the Politics of Knowledge (Arndt Brendecke, 2016); Medicine and Empire, 1600-1960 (Pratik Chakrabarti, 2014)

Anglo-European Science and the Rhetoric of Empire: Malaria, Opium, and British Rule in India, 1756-1895 (Paul Winther); Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Sadiah Qureshi, 2011); Unfreezing the Arctic: Science, Colonialism, and the Transformation of Inuit Lands (Andrew Stuhl)

Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture (Britt Rusert, 2017); Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022); Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar (Jonathan Saha)

The Nature of German Imperialism: Conservation and the Politics of Wildlife in Colonial East Africa (Bernhard Gissibl, 2019); Curious Encounters: Voyaging, Collecting, and Making Knowledge in the Long Eighteenth Century (Edited by Adriana Craciun and Mary Terrall, 2019)

Frontiers of Science: Imperialism and Natural Knowledge in the Gulf South Borderlands, 1500-1850 (Cameron B. Strang); The Ends of Paradise: Race, Extraction, and the Struggle for Black Life in Honduras (Chirstopher A. Loperena, 2022); Mining Language: Racial Thinking, Indigenous Knowledge, and Colonial Metallurgy in the Early Modern Iberian World (Allison Bigelow, 2020); The Herds Shot Round the World: Native Breeds and the British Empire, 1800-1900 (Rebecca J.H. Woods); American Tropics: The Caribbean Roots of Biodiversity Science (Megan Raby, 2017); Producing Mayaland: Colonial Legacies, Urbanization, and the Unfolding of Global Capitalism (Claudia Fonseca Alfaro, 2023)

Domingos Alvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World (James Sweet, 2011); A Temperate Empire: Making Climate Change in Early America (Anya Zilberstein, 2016); Educating the Empire: American Teachers and Contested Colonization in the Philippines (Sarah Steinbock-Pratt, 2019); Soundings and Crossings: Doing Science at Sea, 1800-1970 (Edited by Anderson, Rozwadowski, et al, 2016)

Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai’i and Oceania (Maile Arvin); Overcoming Niagara: Canals, Commerce, and Tourism in the Niagara-Great Lakes Borderland Region, 1792-1837 (Janet Dorothy Larkin, 2018); A Great and Rising Nation: Naval Exploration and Global Empire in the Early US Republic (Michael A. Verney, 2022); In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850-1960 (Alice Conklin, 2013)

Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (Daniela Cleichmar, 2012); Tea Environments and Plantation Culture: Imperial Disarray in Eastern India (Arnab Dey, 2022); Drugs on the Page: Pharmacopoeias and Healing Knowledge in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Edited by Crawford and Gabriel, 2019)

Cooling the Tropics: Ice, Indigeneity, and Hawaiian Refreshment (Hi’ilei Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart, 2022); In Asian Waters: Oceanic Worlds from Yemen to Yokkohama (Eric Tagliacozzo); Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans (Urmi Engineer Willoughby, 2017); Turning Land into Capital: Development and Dispossession in the Mekong Region (Edited by Hirsch, et al, 2022); Mining the Borderlands: Industry, Capital, and the Emergence of Engineers in the Southwest Territories, 1855-1910 (Sarah E.M. Grossman, 2018)

Knowing Manchuria: Environments, the Senses, and Natural Knowledge on an Asian Borderland (Ruth Rogaski); Colonial Fantasies, Imperial Realities: Race Science and the Making of Polishness on the Fringes of the German Empire, 1840-1920 (Lenny A. Urena Valerio); Against the Map: The Politics of Geography in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Adam Sills, 2021)

Under Osman’s Tree: The Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Environmental History (Alan Mikhail, 2017); Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science (Jim Endersby); Proving Grounds: Militarized Landscapes, Weapons Testing, and the Environmental Impact of U.S. Bases (Edited by Edwin Martini, 2015)

Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World (Multiple authors, 2007); Space in the Tropics: From Convicts to Rockets in French Guiana (Peter Redfield); Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850 (Andrew Togert, 2015); Dust Bowls of Empire: Imperialism, Environmental Politics, and the Injustice of ‘Green’ Capitalism (Hannah Holleman, 2016); Postnormal Conservation: Botanic Gardens and the Reordering of Biodiversity Governance (Katja Grotzner Neves, 2019)

Botanical Entanglements: Women, Natural Science, and the Arts in Eighteenth-Century England (Anna K. Sagal, 2022); The Platypus and the Mermaid and Other Figments of the Classifying Imagination (Harriet Ritvo); Rubber and the Making of Vietnam: An Ecological History, 1897-1975 (Michitake Aso); A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Kathryn Yusoff, 2018); Staple Security: Bread and Wheat in Egypt (Jessica Barnes, 2023); No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (Keith Pluymers); Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1768-1941 (Lynn Hollen Lees, 2017); Fish, Law, and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia (Douglas C. Harris, 2001); Everywhen: Australia and the Language of Deep Time (Edited by Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker, and Jakelin Troy); Subject Matter: Technology, the Body, and Science on the Anglo-American Frontier, 1500-1676 (Joyce Chaplin, 2001)

American Lucifers: The Dark History of Artificial Light, 1750-1865 (Jeremy Zallen); Ruling Minds: Psychology in the British Empire (Erik Linstrum, 2016); Lakes and Empires in Macedonian History: Contesting the Water (James Pettifer and Mirancda Vickers, 2021); Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity (Pratik Chakrabarti); Seeds of Control: Japan’s Empire of Forestry in Colonial Korea (David Fedman)

Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination (Julie Cruikshank); The Fishmeal Revolution: The Industrialization of the Humboldt Current Ecosystem (Kristin A. Wintersteen, 2021); The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (Ralph O’Connor); An Imperial Disaster: The Bengal Cyclone of 1876 (Benjamin Kingsbury, 2018); Geographies of City Science: Urban Life and Origin Debates in Late Victorian Dublin (Tanya O’Sullivan, 2019)

American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe (John Krige, 2006); Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule (Ann Laura Stoler, 2002); Rivers of the Sultan: The Tigris and Euphrates in the Ottoman Empire (Faisal H. Husain, 2021);

The Sanitation of Brazil: Nation, State, and Public Health, 1889-1930 (Gilberto Hochman, 2016); The Imperial Security State: British Colonial Knowledge and Empire-Building in Asia (James Hevia); Japan’s Empire of Birds: Aristocrats, Anglo-Americans, and Transwar Ornithology (Annika A. Culver, 2022)

Moral Ecology of a Forest: The Nature Industry and Maya Post-Conservation (Jose E. Martinez, 2021); Sound Relations: Native Ways of Doing Music History in Alaska (Jessica Bissette Perea, 2021); Citizens and Rulers of the World: The American Child and the Cartographic Pedagogies of Empire (Mashid Mayar); Anthropology and Antihumanism in Imperial Germany (Andrew Zimmerman, 2001)

The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century (Multiple authors, 2016); The Nature of Slavery: Environment and Plantation Labor in the Anglo-Atlantic World (Katherine Johnston, 2022); Seeking the American Tropics: South Florida’s Early Naturalists (James A. Kushlan, 2020); The Postwar Origins of the Global Environment: How the United Nations Built Spaceship Earth (Perrin Selcer, 2018)

The Colonial Life of Pharmaceuticals: Medicines and Modernity in Vietnam (Laurence Monnais); Quinoa: Food Politics and Agrarian Life in the Andean Highlands (Linda J. Seligmann, 2023) ; Critical Animal Geographies: Politics, intersections and hierarchies in a multispecies world (Edited by Kathryn Gillespie and Rosemary-Claire Collard, 2017); Spawning Modern Fish: Transnational Comparison in the Making of Japanese Salmon (Heather Ann Swanson, 2022); Imperial Visions: Nationalist Imagination and Geographical Expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840-1865 (Mark Bassin, 2000); The Usufructuary Ethos: Power, Politics, and Environment in the Long Eighteenth Century (Erin Drew, 2022)

Intimate Eating: Racialized Spaces and Radical Futures (Anita Mannur, 2022); On the Frontiers of the Indian Ocean World: A History of Lake Tanganyika, 1830-1890 (Philip Gooding, 2022); All Things Harmless, Useful, and Ornamental: Environmental Transformation Through Species Acclimitization, from Colonial Australia to the World (Pete Minard, 2019)

Practical Matter: Newton’s Science in the Service of Industry and Empire, 1687-1851 (Margaret Jacob and Larry Stewart); Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Setller Colonialism (Jarrod Hore, 2022); Timber and Forestry in Qing China: Sustaining the Market (Meng Zhang, 2021); The World and All the Things upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration (David A. Chang);

Deep Cut: Science, Power, and the Unbuilt Interoceanic Canal (Christine Keiner); Writing the New World: The Politics of Natural History in the Early Spanish Empire (Mauro Jose Caraccioli); Two Years below the Horn: Operation Tabarin, Field Science, and Antarctic Sovereignty, 1944-1946 (Andrew Taylor, 2017); Mapping Water in Dominica: Enslavement and Environment under Colonialism (Mark W. Hauser, 2021)

To Master the Boundless Sea: The US Navy, the Marine Environment, and the Cartography of Empire (Jason Smith, 2018); Fir and Empire: The Transformation of Forests in Early Modern China (Ian Matthew Miller, 2020); Breeds of Empire: The ‘Invention’ of the Horse in Southeast Asia and Southern Africa 1500-1950 (Sandra Swart and Greg Bankoff, 2007)

Science on the Roof of the World: Empire and the Remaking of the Himalaya (Lachlan Fleetwood, 2022); Cattle Colonialism: An Environmental History of the Conquest of California and Hawai’i (John Ryan Fisher, 2017); Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819-1942 (Timothy P. Barnard, 2019)

An Ecology of Knowledges: Fear, Love, and Technoscience in Guatemalan Forest Conservation (Micha Rahder, 2020); Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta: The Making of Calcutta (Debjani Bhattacharyya, 2018); Imperial Bodies in London: Empire, Mobility, and the Making of British Medicine, 1880-1914 (Kristen Hussey, 2021)

Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950 (Jeannie N. Shinozuka); Coral Empire: Underwater Oceans, Colonial Tropics, Visual Modernity (Ann Elias, 2019); Hunting Africa: British Sport, African Knowledge and the Nature of Empire (Angela Thompsell, 2015)

326 notes

·

View notes

Text

X-ray lasers: Why does brighter mean darker?

When we illuminate something, we usually expect that the brighter the source we use, the brighter the resulting image will be. This rule also works for ultra-short pulses of laser light—but only up to a certain intensity. The answer to the question why an X-ray diffraction image 'darkens' at very high X-ray intensities not only deepens fundamental understanding of the light-matter interaction, but also offers a unique perspective for the production of laser pulses that have significantly shorter pulse duration than those currently available.

The more light, the brighter? This observation might sound trivial, were it not for the fact that it is not always true. When silicon crystals are illuminated with ultrafast laser pulses of X-ray light, the resulting diffraction images are indeed initially brighter the more photons fall on the sample, i.e., the higher the beam intensity. Recently, however, a counterintuitive effect has been observed: when the intensity of the X-ray beam starts to exceed a certain critical value, the diffraction images unexpectedly weaken.

This puzzling phenomenon has just been explained, thanks to the efforts of the experimental and theoretical physicists from Japanese, Polish and German research institutions, including the RIKEN SPring-8 Centre in Hyogo, the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IFJ PAN) in Cracow and the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL) at the DESY laboratory in Hamburg.

Read more.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

New SpaceTime out Monday....

SpaceTime 20231016 Series 26 Episode 124

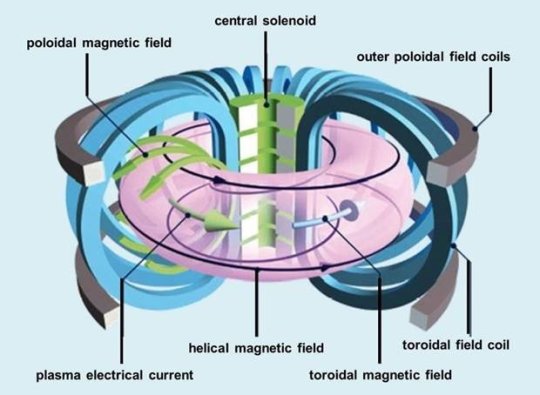

Australia’s first nuclear fusion reactor.

The University of New South Wales is to develop Australia’s first nuclear fusion tokamak.

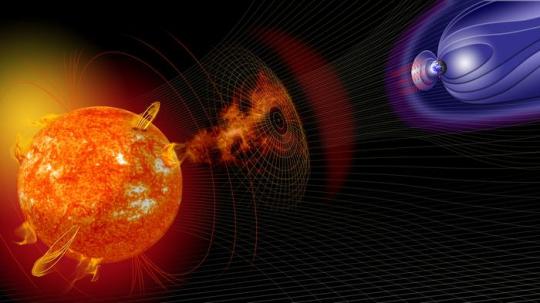

Earth’s largest ever solar storm

Scientists have discovered evidence of what may have been the largest ever solar storm to hit the Earth.

Russian ISS segment springs third leak in under a year

The Nauka multipurpose logistics laboratory module on the Russian segment of the International Space Station has sprung a coolant leak.

The Science Report

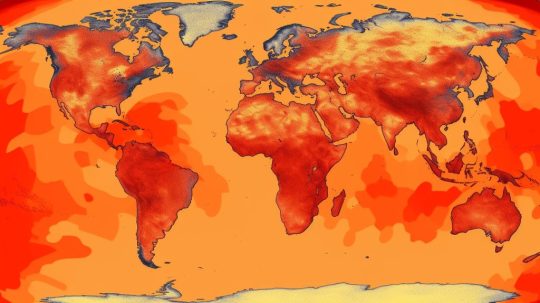

Earth has just had had its hottest September on record.

A new study claims eating grapes is good for eye health.

Scientists discover that cats purr differently than previously thought.

Skeptics guide to foolish fact checkers

SpaceTime covers the latest news in astronomy & space sciences.

The show is available every Monday, Wednesday and Friday through Apple Podcasts (itunes), Stitcher, Google Podcast, Pocketcasts, SoundCloud, Bitez.com, YouTube, your favourite podcast download provider, and from www.spacetimewithstuartgary.com

SpaceTime is also broadcast through the National Science Foundation on Science Zone Radio and on both i-heart Radio and Tune-In Radio.

SpaceTime daily news blog: http://spacetimewithstuartgary.tumblr.com/

SpaceTime facebook: www.facebook.com/spacetimewithstuartgary

SpaceTime Instagram @spacetimewithstuartgary

SpaceTime twitter feed @stuartgary

SpaceTime YouTube: @SpaceTimewithStuartGary

SpaceTime -- A brief history

SpaceTime is Australia’s most popular and respected astronomy and space science news program – averaging over two million downloads every year. We’re also number five in the United States. The show reports on the latest stories and discoveries making news in astronomy, space flight, and science. SpaceTime features weekly interviews with leading Australian scientists about their research. The show began life in 1995 as ‘StarStuff’ on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s (ABC) NewsRadio network. Award winning investigative reporter Stuart Gary created the program during more than fifteen years as NewsRadio’s evening anchor and Science Editor. Gary’s always loved science. He studied astronomy at university and was invited to undertake a PHD in astrophysics, but instead focused on his career in journalism and radio broadcasting. He worked as an announcer and music DJ in commercial radio, before becoming a journalist and eventually joining ABC News and Current Affairs. Later, Gary became part of the team that set up ABC NewsRadio and was one of its first presenters. When asked to put his science background to use, Gary developed StarStuff which he wrote, produced and hosted, consistently achieving 9 per cent of the national Australian radio audience based on the ABC’s Nielsen ratings survey figures for the five major Australian metro markets: Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, and Perth. The StarStuff podcast was published on line by ABC Science -- achieving over 1.3 million downloads annually. However, after some 20 years, the show finally wrapped up in December 2015 following ABC funding cuts, and a redirection of available finances to increase sports and horse racing coverage. Rather than continue with the ABC, Gary resigned so that he could keep the show going independently. StarStuff was rebranded as “SpaceTime”, with the first episode being broadcast in February 2016. Over the years, SpaceTime has grown, more than doubling its former ABC audience numbers and expanding to include new segments such as the Science Report -- which provides a wrap of general science news, weekly skeptical science features, special reports looking at the latest computer and technology news, and Skywatch – which provides a monthly guide to the night skies. The show is published three times weekly (every Monday, Wednesday and Friday) and available from the United States National Science Foundation on Science Zone Radio, and through both i-heart Radio and Tune-In Radio.

#science#space#astronomy#physics#news#nasa#esa#astrophysics#spacetimewithstuartgary#starstuff#spacetime

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The First Light of Trinity

— By Alex Wellerstein | July 16, 2015 | Annals of Technology

Seventy years ago, the flash of a nuclear bomb illuminated the skies over Alamogordo, New Mexico. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

The light of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. This is because the heat of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. Seventy years ago today, when the first atomic weapon was tested, they called its light cosmic. Where else, except in the interiors of stars, do the temperatures reach into the tens of millions of degrees? It is that blistering radiation, released in a reaction that takes about a millionth of a second to complete, that makes the light so unearthly, that gives it the strength to burn through photographic paper and wound human eyes. The heat is such that the air around it becomes luminous and incandescent and then opaque; for a moment, the brightness hides itself. Then the air expands outward, shedding its energy at the speed of sound—the blast wave that destroys houses, hospitals, schools, cities.

The test was given the evocative code name of Trinity, although no one seems to know precisely why. One theory is that J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the U.S. government’s laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and the director of science for the Manhattan Project, which designed and built the bomb, chose the name as an allusion to the poetry of John Donne. Oppenheimer’s former mistress, Jean Tatlock, a student at the University of California, Berkeley, when he was a professor there, had introduced him to Donne’s work before she committed suicide, in early 1944. But Oppenheimer later claimed not to recall where the name came from.

The operation was designated as top secret, which was a problem, since the whole point was to create an explosion that could be heard for a hundred miles around and seen for two hundred. How to keep such a spectacle under wraps? Oppenheimer and his colleagues considered several sites, including a patch of desert around two hundred miles east of Los Angeles, an island eighty miles southwest of Santa Monica, and a series of sand bars ten miles off the Texas coast. Eventually, they chose a place much closer to home, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on an Army Air Forces bombing range in a valley called the Jornada del Muerto (“Journey of the Dead Man,” an indication of its unforgiving landscape). Freshwater had to be driven in, seven hundred gallons at a time, from a town forty miles away. To wire the site for a telephone connection required laying four miles of cable. The most expensive single line item in the budget was for the construction of bomb-proof shelters, which would protect some of the more than two hundred and fifty observers of the test.

The area immediately around the bombing range was sparsely populated but not by any means barren. It was within two hundred miles of Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and El Paso. The nearest town of more than fifty people was fewer than thirty miles away, and the nearest occupied ranch was only twelve miles away—long distances for a person, but not for light or a radioactive cloud. (One of Trinity’s more unusual financial appropriations, later on, was for the acquisition of several dozen head of cattle that had had their hair discolored by the explosion.) The Army made preparations to impose martial law after the test if necessary, keeping a military force of a hundred and sixty men on hand to manage any evacuations. Photographic film, sensitive to radioactivity, was stowed in nearby towns, to provide “medical legal” evidence of contamination in the future. Seismographs in Tucson, Denver, and Chihuahua, Mexico, would reveal how far away the explosion could be detected.

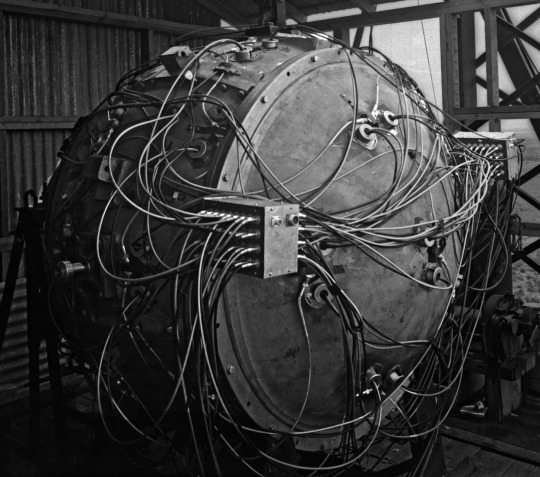

The Trinity test weapon. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

On July 16, 1945, the planned date of the test, the weather was poor. Thunderstorms were moving through the area, raising the twin hazards of electricity and rain. The test weapon, known euphemistically as the gadget, was mounted inside a shack atop a hundred-foot steel tower. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of wires, screws, switches, high explosives, radioactive materials, and diagnostic devices, and was crude enough that it could be tripped by a passing storm. (This had already happened once, with a model of the bomb’s electrical system.) Rain, or even too many clouds, could cause other problems—a spontaneous radioactive thunderstorm after detonation, unpredictable magnifications of the blast wave off a layer of warm air. It was later calculated that, even without the possibility of mechanical or electrical failure, there was still more than a one-in-ten chance of the gadget failing to perform optimally.

The scientists were prepared to cancel the test and wait for better weather when, at five in the morning, conditions began to improve. At five-ten, they announced that the test was going forward. At five-twenty-five, a rocket near the tower was shot into the sky—the five-minute warning. Another went up at five-twenty-nine. Forty-five seconds before zero hour, a switch was thrown in the control bunker, starting an automated timer. Just before five-thirty, an electrical pulse ran the five and a half miles across the desert from the bunker to the tower, up into the firing unit of the bomb. Within a hundred millionths of a second, a series of thirty-two charges went off around the device’s core, compressing the sphere of plutonium inside from about the size of an orange to that of a lime. Then the gadget exploded.

General Thomas Farrell, the deputy commander of the Manhattan Project, was in the control bunker with Oppenheimer when the blast went off. “The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun,” he wrote immediately afterward. “It was golden, purple, violet, gray, and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse, and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. It was that beauty the great poets dream about but describe most poorly and inadequately.” Twenty-seven miles away from the tower, the Berkeley physicist and Nobel Prize winner Ernest O. Lawrence was stepping out of a car. “Just as I put my foot on the ground I was enveloped with a warm brilliant yellow white light—from darkness to brilliant sunshine in an instant,” he wrote. James Conant, the president of Harvard University, was watching from the V.I.P. viewing spot, ten miles from the tower. “The enormity of the light and its length quite stunned me,” he wrote. “The whole sky suddenly full of white light like the end of the world.”

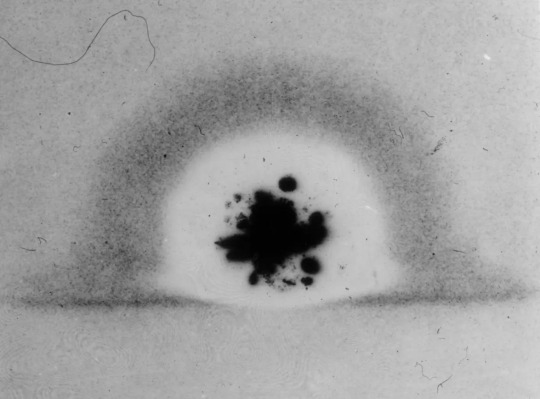

In its first milliseconds, the Trinity fireball burned through photographic film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Trinity was filmed exclusively in black and white and without audio. In the main footage of the explosion, the fireball rises out of the frame before the cameraman, dazed by the sight, pans upward to follow it. The written accounts of the test, of which there are many, grapple with how to describe an experience for which no terminology had yet been invented. Some eventually settle on what would become the standard lexicon. Luis Alvarez, a physicist and future participant in the Hiroshima bombing, viewed Trinity from the air. He likened the debris cloud, which rose to a height of some thirty thousand feet in ten minutes, to “a parachute which was being blown up by a large electric fan,” noting that it “had very much the appearance of a large mushroom.” Charles Thomas, the vice-president of Monsanto, a major Manhattan Project contractor, observed the same. “It looked like a giant mushroom; the stalk was the thousands of tons of sand being sucked up by the explosion; the top of the mushroom was a flowering ball of fire,” he wrote. “It resembled a giant brain the convolutions of which were constantly changing.”

In the months before the test, the Manhattan Project scientists had estimated that their bomb would yield the equivalent of between seven hundred and five thousand tons of TNT. As it turned out, the detonation force was equal to about twenty thousand tons of TNT—four times larger than the expected maximum. The light was visible as far away as Amarillo, Texas, more than two hundred and eighty miles to the east, on the other side of a mountain range. Windows were reported broken in Silver City, New Mexico, some hundred and eighty miles to the southwest. Here, again, the written accounts converge. Thomas: “It is safe to say that nothing as terrible has been made by man before.” Lawrence: “There was restrained applause, but more a hushed murmuring bordering on reverence.” Farrell: “The strong, sustained, awesome roar … warned of doomsday and made us feel that we puny things were blasphemous.” Nevertheless, the plainclothes military police who were stationed in nearby towns reported that those who saw the light seemed to accept the government’s explanation, which was that an ammunition dump had exploded.

Trinity was only the first nuclear detonation of the summer of 1945. Two more followed, in early August, over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing as many as a quarter of a million people. By October, Norris Bradbury, the new director of Los Alamos, had proposed that the United States conduct “subsequent Trinity’s.” There was more to learn about the bomb, he argued, in a memo to the new coördinating council for the lab, and without the immediate pressure of making a weapon for war, “another TR might even be FUN.” A year after the test at Alamogordo, new ones began, at Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands. They were not given literary names. Able, Baker, and Charlie were slated for 1946; X-ray, Yoke, and Zebra were slated for 1948. These were letters in the military radio alphabet—a clarification of who was really the master of the bomb.

Irradiated Kodak X-ray film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

By 1992, the U.S. government had conducted more than a thousand nuclear tests, and other nations—China, France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union—had joined in the frenzy. The last aboveground detonation took place over Lop Nur, a dried-up salt lake in northwestern China, in 1980. We are some years away, in other words, from the day when no living person will have seen that unearthly light firsthand. But Trinity left secondhand signs behind. Because the gadget exploded so close to the ground, the fireball sucked up dirt and debris. Some of it melted and settled back down, cooling into a radioactive green glass that was dubbed Trinitite, and some of it floated away. A minute quantity of the dust ended up in a river about a thousand miles east of Alamogordo, where, in early August, 1945, it was taken up into a paper mill that manufactured strawboard for Eastman Kodak. The strawboard was used to pack some of the company’s industrial X-ray film, which, when it was developed, was mottled with dark blotches and pinpoint stars—the final exposure of the first light of the nuclear age.

#Hiroshima | Japan 🇯🇵 | John Donne | Manhattan Project | Monsanto#Nagasaki | Japan 🇯🇵 | Nuclear Weapons | Second World War | World War II#The New Yorker#Alex Wellerstein#Los Alamos National Laboratory#New Mexico#J. Robert Oppenheimer#John Donne#Jean Tatlock#University of California Berkeley#Jornada del Muerto | Journey of the Dead Man#General Thomas Farrell#Nobel Prize Winner Physicist Ernest O. Lawrence#Luis Alvarez#US 🇺🇸#China 🇨🇳#France 🇫🇷#Soviet Union (Now Russia 🇷🇺)#Alamogordo | New Mexico#Eastman Kodak#Nuclear Age

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

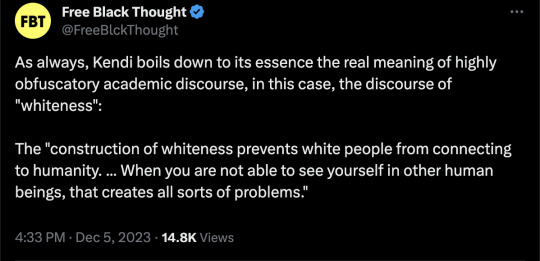

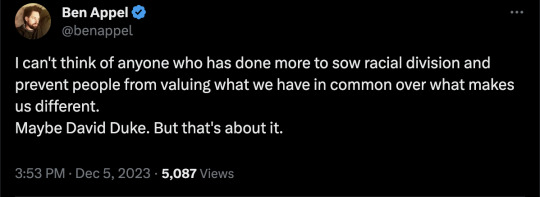

He's such a shallow thinker that you can always trust Kendi to blurt out the quiet part.

But what's interesting is the projection. He's correct, but not in the way he thinks. Because he's talking about himself and his own personality flaws and mental disorders. This is a quote from his best-selling screed:

I DID NOT knock on Clarence’s door that day to discuss Welsing’s “color confrontation theory.” Or Diop’s two-cradle theory. He had snickered at those theories many times before. I came to share another theory, the one that finally figured White people out.

“They are aliens,” I told Clarence, confidently resting on the doorframe, arms crossed. “I just saw this documentary that laid out the evidence. That’s why they are so intent on White supremacy. That’s why they seem to not have a conscience. They are aliens.”

-- Ibram X. Kendi, "How to Be an Antiracist"

"White supremacy" in this sense isn't the KKK or the Nazis. It's "the white man's science," and "objectivity is white supremacy," and "merit is white supremacy," and "math is white supremacy," and "the U.S. Constitution is a tool of white supremacy."

David Duke didn't get millions of academic funding and an entire institute created for him by Boston University. David Duke didn't get a $10m donation from a co-founder of one of the most powerful social media platforms. David Duke's didn't publish a bestsellng insane manifesto. David Duke's ideology hasn't permeated K-12 in every state in the country. David Duke's ideology hasn't been the basis for reeducation programs conducted through everything from the medical profession to soft drink manufacturers to government nuclear laboratories.

When people insist that "woke" is "just about being kind" or "just about being aware of racism," they're lying. I don't mean they're mistaken, I mean they're lying. It's been a third of a decade since activists cut the brake-line and pulled out all the stops. The idea that we don't know what this is, what's going on, is dishonest.

Next time you hear it, show the person this video and ask them, do you agree with Kendi? They won't know what to say. It's the same as when you ask a moderate Xian whether they agree with their god that you deserve to be tortured for eternity. They know there's an ideologically correct answer, "yes," and they know there's a morally correct answer, "no." They'll refuse to answer the question: "I don't make the rules, god does," and "you send yourself there" are classic tactics to avoid being honest.

This is the same thing. They have to agree with him ideologically, because they can't claim he's Not a True Scotsman. But if they do agree with him, they've exposed the whole "it's just about being kind" lie.

Of course, this won't work on the fundamentalist True Believers. If you ask someone from Westboro the hell question, they won't even blink, they'll say, "yes, absolutely." Again, same thing applies.

It's one thing for Kendi himself to have these ideas. A much larger problem is the fact that the thunderous applause from the audience shows how far and how normalized the moral corruption has set in.

People who endorse Kendi should be regarded by society in the same way as those who endorse David Duke.

#Ibram X. Kendi#Free Black Thought#Wanjiru Njoya#Ben Appel#Kendi is a racist#racial division#racism#neoracism#whiteness#white supremacy#dehumanization#critical race theory#antiracism#antiracism as religion#woke#wokeness#wokeness as religion#cult of woke#wokeism#religion is a mental illness

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Xisuma. Mr. Void. Server daddy. Bone dude. How are you?”

Xisuma looked up from his desk and took off his glasses. “I hate half of that sentence, and I really don’t like the way you’re smiling at me right now. What do you want, Zedaph?”

“It’s nothing, really. Silly thing. Could you sign this piece of paper? No need to read it or anything, just need your autograph, you know!” Zedaph slid the paper along Xisuma’s desk. Xisuma picked it up and put back on his glasses. “No! I mean, no, haha, reading is for nerds don’t do that, you don’t want to be a nerd, do you?”

Xisuma, ignoring Zed, read the whole paper, and with each line, he looked more and more tired.

“Zed, I swear we’ve done this song and dance before. Is this another off-server permission slip?”

“Okay, yes, maybe, but it’s another very cool opportunity, and I need an admin’s signature in order to do it. Please?” Zed gave Xisuma the biggest puppy dog eyes he could.

“What is it exactly you’ll be doing? The summary of the trip is very lacking in detail.”

“Uh, testing. Stuff. It’s like my science experiments from last season. I’m meeting with a grizzled war veteran to help him test a few things. Casual stuff, really.” Zedaph definitely wasn’t sweating.

Xisuma sighed. “You know what, fine. I am not coming to pick you up early if you throw up or something, got it?”

“Yes, yes yes! Oh thank you Admin Big Bone!” Zedaph clapped and pranced around the room.

“…you can just call me by my name, Zed.” Xisuma said, signing the paper and wishing he could resign as admin. “So, where is this Snowchester, anyway?”

——

“YOOOOO!!! HOLY SHIT YOU’RE HERE!!!”

“I am, and I am so, so excited!” Zedaph was almost knocked over by a dude in a big brown coat. “Tubbo, my man, how are you?”

“How am I? I’ve never been better!” Tubbo grinned, shaking Zedaph’s hand. “My friend, we’ve got nukes to build and test. They’re all waiting for us in the laboratories I built, and I secured a testing sight.”

“One question: will there be lab coats?” Zedaph asked.

“Of fucking course! What kind of nuclear scientists would we be without lab coats?” Tubbo exclaimed.

“Well, what are we waiting for, then? Let’s go!” Zedaph said, and they high-fived as they made their way to Snowchester and the nuclear bomb testing site. Needless to say, the phrase “nuclear bomb” had been purposely left out of the permission slip, because there was no way in hell Xisuma would have let Zed go otherwise.

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amid a desert landscape a visionary unveils an invention that will forever change the world as we know it.

That’s the climactic scene of the Christopher Nolan biopic Oppenheimer, about the eponymous J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb.” It’s also the opening scene of the Barbie movie, directed and co-written by indie auteur Greta Gerwig, which opened on the same day as Oppenheimer.

Despite the two films’ radically different subject matter and tone—one a dramatic examination of man’s hubris and the threat of nuclear apocalypse and the other a neon-drenched romp about Mattel’s iconic fashion doll—they have far more in common than just their release date. Both movies consider the complicated legacies of two American icons and how to grapple with and perhaps even atone for them.

In Oppenheimer, the desert scene depicts the Trinity test, the world’s first detonation of a nuclear bomb near Los Alamos, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945. A brilliant but flawed theoretical physicist and the rest of his team work frantically to develop the weapon for the United States before the Nazis can beat them to the punch; they then gather on bleak, lunar-white sands near their secret laboratory to test the terrifying creation.

The countdown timer ticks to 00:00:00, the proverbial big red button is pushed, and a blast ignites the sky—a blinding white flash that quickly morphs into a towering inferno. Everything goes silent as Oppenheimer stares in awe from behind a makeshift protective barrier at what he has created.

Suddenly, he begins experiencing flashes of a different kind, premonitions of the human horror and suffering his weapon will wreak. Nolan is unambiguously signaling to the audience that this is a pivotal moment for the world, and for Oppenheimer personally, as what was once merely a theoretical idea has become monstrously real. The fallout, both literally and figuratively, will be out of Oppenheimer’s control.

Barbie’s critical desert scene comes not at the film’s climax but at its very beginning. The movie opens with a parody of the famous “The Dawn of Man” scene from Stanley Kubrick’s classic 1968 science fiction film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. As a red-orange sunrise breaks across a rocky desert landscape, a voiceover (from none other than Dame Helen Mirren) begins: “Since the beginning of time, since the first little girl ever existed, there have been dolls. But the dolls were always and forever baby dolls.” On screen, underscored by the ominous notes of Richard Strauss’s “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” little girls sit amid dusty canyon walls playing with baby dolls.

“Until…” Mirren says. And then comes the reveal: The little girls look up to see a massive, monolith-sized Margot Robbie, dressed in the black and white-striped swimsuit of the very first Barbie doll. She lifts her sunglasses and winks. The little girls are stunned—and, like the apes in the classic sci-fi movie, they begin to angrily dash their baby dolls against the ground.

This is Barbie’s mythic origin story: Once upon a time, little girls could only play with baby dolls meant to socialize them into wanting to be good wives and, eventually, mothers. Then came Ruth Handler, who in 1959 decided to create a doll with an adult woman’s body, adult women’s fashions, and adult women’s careers so that little girls could dream of being more than just wives and mothers. And the rest is history. Thanks to such iterations as doctor Barbie, chef Barbie, scientist Barbie, professional violinist Barbie, and beyond, Barbie opened up young girls to a world of possibilities and, Mirren says, “All problems of feminism and equal rights [were] solved.”

Well, not so fast: Mirren adds one final, snarky beat: “At least,” she says, “that’s what the Barbies think.”

Thus Gerwig introduces the central tension that animates the movie: Handler set out to create a feminist toy to empower and inspire young girls. But we sitting in the audience in 2023 know that things worked out a little differently. In the intervening years, Barbie would come under fire from feminists and other critics for a whole host of sins: encouraging unrealistic and harmful beauty standards that contribute to negative body image issues, eating disorders, and depression among pre-adolescent girls; lacking diversity and perpetuating white supremacy, ableism, and heteronormativity; objectifying women; promoting consumerism and capitalism; and even contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.

And here is the core parallel between Barbie and Oppenheimer: Two iconic American creators who ostensibly meant well but whose creations caused irreparable harm. And two iconic American directors (Nolan is British-American) who set out to tell their stories from a very modern perspective, humanizing them while also addressing their harmful legacies.

But while Nolan obviously had the much harder task—no matter how much harm you think Barbie has done to the psyches of young girls over the years, there’s simply no comparison to the human toll of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the environmental impact of decades of nuclear testing, or the cost of the nuclear arms race—oddly enough, it’s Gerwig who ends up taking her job of atonement far more seriously.

As its opening scene shows, the Barbie movie lets the audience know right from the start that it’s self-aware. It knows that Barbie is problematic. And it’s going to go there.

And it does—almost to the point of overkill. The basic plot of the movie is this: Barbie is living happily in Barbie Land, a perfect pink plastic world where she and her fellow Barbies run everything from the White House to the Supreme Court and have everything they could ever want, from dream houses to dream cars to dreamy boyfriends (Ken)—the last of which they treat as little more than accessories.

But suddenly, things start to go wrong in Barbie’s happy feminist utopia, and to fix it, she is forced to journey into the real world—our world—accompanied by Ken, who insists on going with her. When she does, she realizes that contrary to what she believed (as Mirren told us in the opening scene), the invention of Barbies didn’t solve gender inequality in the real world. In the real world, Barbie is confronted not only with the dominance of the patriarchy (she discovers, for instance, that Mattel’s CEO is a man, played by Will Ferrell), but also with the fact that young girls seem to hate her.

In a crucial early scene, Robbie’s Barbie encounters ultracool Gen-Z teen Sasha (played by Ariana Greenblatt), who delivers a scathing monologue about everything that’s wrong with Barbie, the doll and cultural symbol—basically a checklist of all the criticisms lobbed at Barbie over the years, from promoting unrealistic beauty standards to destroying the planet with rampant capitalism. Barbie is crestfallen.

Meanwhile, there’s a subplot involving Ken’s parallel discovery of patriarchy, and how awesome and different it seems to be from his subjugated life in Barbie Land. Ken proceeds to go full men’s rights, heading back to Barbie Land and seizing power. He transforms Barbie’s dream house into Ken’s Mojo Dojo Casa House, where Barbies serve men and “every night is boys’ night!”

Barbie enlists the help of Sasha and her mom (played by America Ferrera)—a Mattel employee who secretly dreams up ideas for new, more realistic Barbies such as anxiety Barbie—to unseat Ken and restore female power in Barbie Land. Along the way, Ferrera’s character delivers the film’s other major feminist monologue, about how hard it is being a woman in the real world.

The monologues are unsubtle, as are the repeated mentions of concepts like the patriarchy. In every scene and nearly every line, the movie hits the audience over the head with the pro-feminism message. Gerwig knows what her job is—to atone for Barbie’s sins (and, yes, help Mattel sell more dolls)—and she makes sure everyone knows that she has fully understood the assignment.

But it’s in the film’s quieter, more tender moments that Gerwig’s background as an indie filmmaker and her true talent shine through, and where she’s able to communicate the message in a subtler, but ultimately more impactful, way. The scene where Barbie in the real world sees an elderly woman for the first time (old people and wrinkles don’t exist in Barbie Land, obviously) and is stunned at how beautiful she is, wrinkles and all. Or the scenes where Barbie talks quietly with her deceased creator, an elderly Handler (played by Rhea Perlman), who explains that the name Barbie was an homage to Handler’s daughter, Barbara, who inspired her to make the doll.

The overall result is a movie that, even if a bit ham-fisted in its over-the-top messaging, doesn’t shy away from the uglier parts of Barbie’s legacy. It looks them right in the face, wrinkles and all.

I said above that the Trinity test scene is the climactic scene in Oppenheimer, but that’s not really the case. For a movie about the complicated life and legacy of the man credited with creating the world’s most destructive weapon, it should be the climax. You might imagine it would follow with a denouement of the inventor confronting the reality that his creation is used to kill tens of thousands of Japanese civilians and sparks an arms race that threatens to destroy all of humanity.

These scenes are in there, but they are given short shrift next to the other story Nolan wants to tell: that of how Oppenheimer, once considered an American hero, was mistreated by his country in the postwar years. As McCarthy-era fears of communist infiltration grip the country, Oppenheimer’s previous ties to the Communist Party (he never joined the party himself, but he had close family members and friends who were members, and he supported various left-wing causes) are mysteriously brought to the FBI’s attention despite already being well documented. His security clearance is revoked, and his career working with the U.S. government on nuclear issues ends.

It is this storyline—not the apocalyptic destruction of two Japanese cities—that is given the most pathos. Much of the movie’s three-hour run time—and nearly all of its third act—centers on what we are clearly meant to see as the great evil that was done to this man who did so much for his country. The real climax of the film is not the Trinity test, nor even the bombings of Japan (which are not even shown in the movie), but rather the moment we learn who betrayed Oppenheimer by handing over his security file to the FBI.

This is the shocking revelation that is meant to induce gasps in the audience, not the images of charred and irradiated bodies. In fact, those images aren’t even shown to us, the viewers. In the scene where Oppenheimer and his team are shown photos of the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the camera stays tight on Oppenheimer’s face as he reacts to the images—a reaction that consists of him putting his head down to avoid seeing them.

It is an act of cowardice on Oppenheimer’s part, yes, but also on Nolan’s. Indeed, the only glimpses we get of the macabre effects of the atom bomb take place in Oppenheimer’s fevered imagination, and even then, they are brief flashes used for shock value: skin flapping off the beautiful face of an admiring female colleague; the charred, faceless husk of a child’s body Oppenheimer accidentally steps on; a male colleague vomiting from the effects of radiation. Of the Japanese victims, there is nothing. They remain theoretical, faceless.

Nolan has said that he chose not to depict the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki not to sanitize them but because the film’s events are shown from Oppenheimer’s point of view. “We know so much more than he did at the time,” Nolan said at a screening of the movie in New York. “He learned about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the radio, the same as the rest of the world.”

But in reading the numerous interviews he’s given about the movie, it’s also clear that Nolan fundamentally sees Oppenheimer as a tragic hero—Nolan has repeatedly called Oppenheimer “the most important person who ever lived”—and Oppenheimer’s story as a distinctly American one. “I believe you see in the Oppenheimer story all that is great and all that is terrible about America’s uniquely modern power in the world,” he told the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. “It’s a very, very American story.”

That Nolan’s film devotes so much runtime to Oppenheimer’s point of view and how he was tragically betrayed by his country is partly due to the fact that the film is not an original story but rather an adaptation of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of the great scientist, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. That book also places Oppenheimer being stripped of his security clearance at its center. But that didn’t mean Nolan had to do the same in his adaptation. That was a choice. And the end result is what military technology writer Kelsey Atherton aptly described as “a 3 hour long argument that the greatest victim of atomic weaponry was Oppenheimer’s clearance.”

At a time when Americans are struggling to reckon with their country’s past and how it has shaped the present—from fights over how (or even whether) to teach children about the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow; to debates, including in these very pages, over the role (or lack thereof) of NATO expansion in Russia’s decision to wage war on Ukraine; to retrospectives on the myriad failures of the U.S. war in Afghanistan; and beyond—the fact that the two biggest films in theaters right now are attempting to confront the legacies of two American icons, the nuclear bomb and Barbie, is understandable and perhaps even impressive.

But the impulse to look away from the ugliest parts of those legacies remains strong, and Oppenheimer never fully faces them.

24 notes

·

View notes