#aboriginal history

Photo

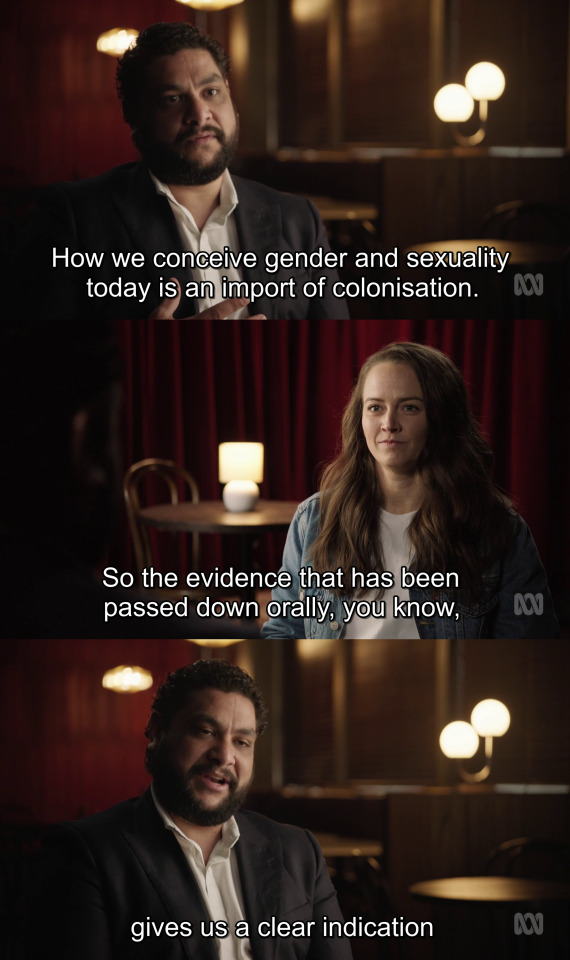

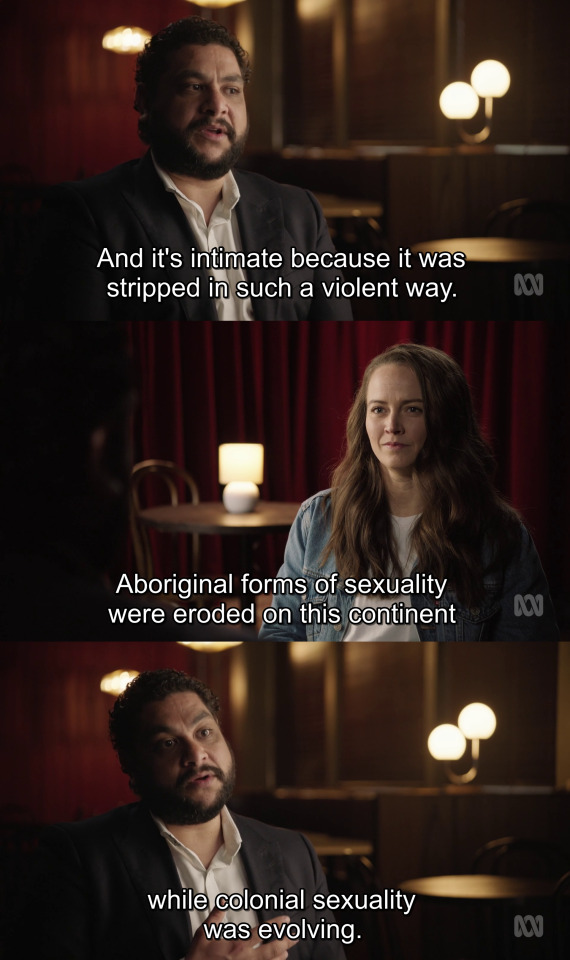

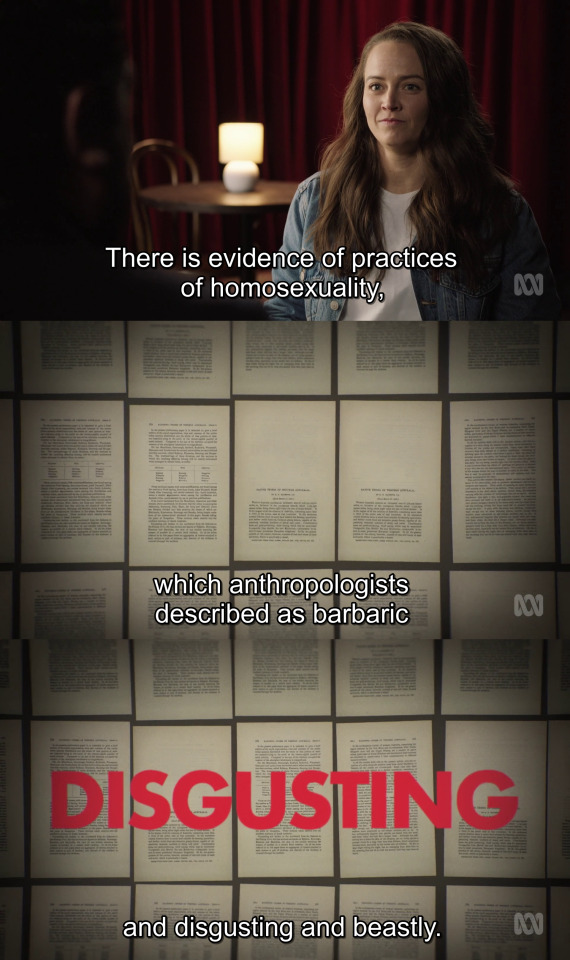

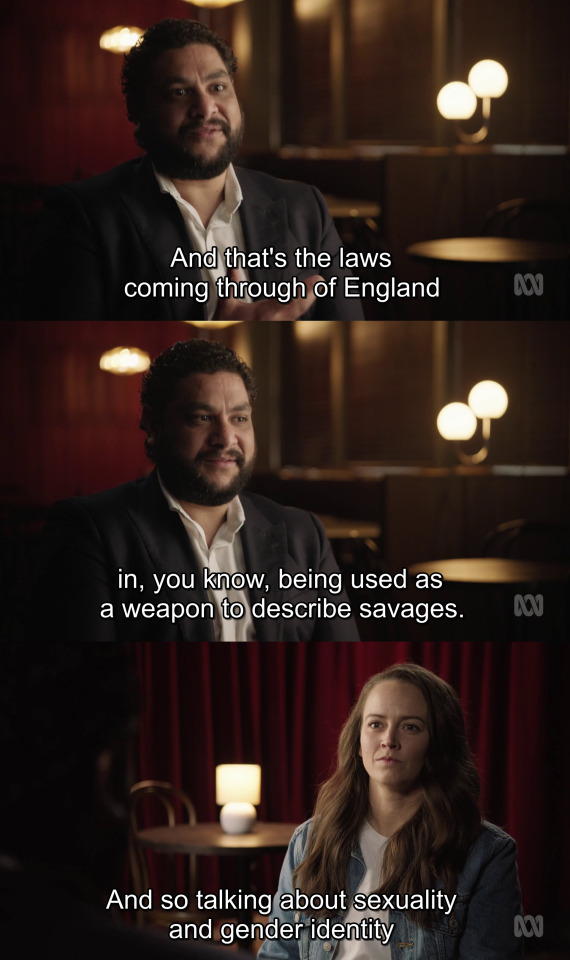

QUEERSTRALIA (2022) Episode 1

dir. Stamatia Maroupas

#queerstralia#documentaryedit#todd fernando#zoe coombs marr#lgbtqai#aboriginal#history#colonisation#aboriginal history#australian history#queer history#lgbt history#australian queer history#racism tw#homophobia tw

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

NAIDOC Week

It’s NAIDOC Week in Australia, a week acknowledging and celebrating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and culture.

If you’d like to learn a bit about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander queer history, we’ve put together a few links to get you started.

Peopling the Empty Mirror: The Prospects for Lesbian and Gay Aboriginal History by the Gays and Lesbians Aboriginal Alliance (1994) - an essay reviewing literature on Aboriginal sexuality, and discussing future of Aboriginal queer history

ATSI Rainbow Archive curated by Andrew Farrell - an online archive active from 2014 to 2021, cataloguing links from across the internet referencing queer Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experiences.

What do we know about queer Indigenous history? by James Findley (2018) - an article in which Findley speaks to queer Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people about their understandings and experiences of queer Indigenous history.

Colouring the Rainbow: Blak Queer and Trans Perspectives edited by Dino Hodge (2015) - an anthology of essays and personal stories by twenty-two First Nations people exploring identity, culture and queerness.

We are far from experts so if you have links to more sources feel free to add them.

#naidoc week#naidoc#aboriginal history#torres strait islander history#atsi history#australia#lgbt#lgbtq#queer#queer histroy

450 notes

·

View notes

Text

On This Day In History

July 12th, 1971: The Australian Aboriginal Flag is flown for the first time.

#this is a great flag just from a design perspective#history#flag#vexillology#australia#australian history#aboriginal history#land rights

355 notes

·

View notes

Text

In High School, we spent half the year in history learning about the Kennedy assassination from my conspiracy theorist rightwing nutjob history teacher. We were made to watch endless hours of History Channel documentaries about various bunk theories and our final was a paper on which theory we thought was correct. 2000 words in year 10 I believe. We set up a prop car to analyse where the bullet marks were. We read testimony from CIA agents about their investigation. We looked at the product catalogue for the store where Oswald bought his rifle. Not once, in my entire primary and secondary education, were the wars between colonisers and indigenous peoples discussed.

I’m Australian.

I found out about the Frontier Wars a few months ago browsing Wikipedia. The fraudulent Terra Nullius narrative has been the only voice in this country for almost my entire life. And we’re voting soon on a constitutional change that requires an indigenous Voice to Parliament.

#kennedy assassination#australia#australian history#indigenous history#aboriginal history#voice to parliament#frontier wars#australian frontier wars

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

For those who didn't know, Archie Roach died this year. I haven't been on this blog much, and I apologise - I burnt myself out this year and am finally starting to recover.

But first I have to post about Archie Roach. I'm not big into music or anything but this guy was, and still is, a big deal.

youtube

If you know any of his songs it will be that one.

Archibalie was an Australian singer, songwriter and Aboriginal activist. Also known as "Uncle Archie", Roach was a Gunditjmara and Bundjalung elder who campaigned for the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The song "took the children away" is about the stolen generation- when white people decided it would be best if aboriginal children where taken from their families to be raised the white way.

His songs are amazing and always give me goosebumps. All Aussies should know of him, and at least this one song of his, if not others. Archie himself was a stolen child and you can hear his real life experience in the song.

Paul Kelly, musician: "I first heard about Archie through my guitar player, Steve Connolly, who’d seen him on a TV show called Blackout and said, “You gotta hear this guy.” We wanted to do something special for our Hamer Hall show in 1990 so we tracked down Archie [to support]. He finished [his set] with Took the Children Away. There was this stunned silence; he thought he’d bombed. Then this wave of applause grew and grew; I’d never heard anything like it."

Adam Briggs, musician: "It wasn’t until I was older that I grasped the importance and weight of his songs. Took the Children Away is a pivotal song for Australia. That line – “This story’s right, this story’s true, I would not tell lies to you” – sums up his whole career and why he resonates with everybody. I reckon if you don’t like Archie Roach, there’s something wrong with you."

#archie roach#took the children away#aboriginal history#australian music#stolen generation#songs that give you goose bumps#massive respect#Youtube

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

damn y'all really out here with a tumblr. anyways, im coming to the library for my second time ever tomorrow. what do i have to check out?

Hello!

Sorry we didn’t get back to you sooner on this, but we hope you had a great time! Just in case you’ll be coming back again in the future, here are a couple of fantastic things to take a look at:

Black Opium by Fiona Foley is a permanent art installation that can be viewed from the middle of the knowledge walk, though the best place (in my opinion) to see the work is from the balconies on level four. Foley’s work is layered with meaning, exploring a time when Aboriginal people were often paid for their labours with opium, robbing them of their health, and in some cases, their lives. It was inspired by her research into the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 and its impacts upon the lives of Aboriginal and Chinese Australian workers.

If you are already on level four it is also worth taking a look at the Talbot Family Treasures Wall, where we display some of the most unusual, striking, and significant items within our collections. Nearby is also the Australian Library of Art Showcase, where you can see exceptional and unique ‘artist’s books’ on display, as well as our history and art of the book collection containing everything from cuneiform tablets and Latin funerary inscriptions to early colour-print popup books for children.

If you would like to personally look at some of our treasures from within the repositories, you can call out items with assistance from the librarians on level four - some of my favourite treasures include the signed World War Two American Baseball and Queen Victoria’s stockings .

If you’re interested in creative and physical activities, we also have an entire building dedicated to our makerspace, The Edge, which contains 3D printers, laser cutters, soldering equipment, sewing machines, a podcasting and recording space, and tonnes more.

Happy hunting!

#library#librarian#libraries#black history#aboriginal history#asks#ancient egypt#cuneiform#latin#roman#roman history#visit your libraries kids#support libraries#support your library#state library of queensland

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three postcards produced by the Australian Queer Archives (formerly Australian Gay and Lesbian Archives, though always fully inclusive in practice), where I volunteer. My write-up below is paraphrased from the text on the reverse.

The first shows Aboriginal South Sea Islander man Malcolm Cole dressed as Captain Cook for the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Parade of 1988. Text on back notes that this was a camp response to Bicentennial celebrations, in which Cole and friends created the first official First Nations float. It was a ‘ship’, pulled the length of the parade by white ‘convict’ men. Malcolm was a dancer, founding member of the Aboriginal Islander Dance Theatre and a HIV/AIDS activist. More about Cole, including footage of him at Mardi Gras, can be found at the Blak History Month website (which is also a great repository of Aboriginal history in general).

The second postcard shows Lyn Cooper, wearing her ‘I Am a Lesbian’ shirt at the International Women’s Day celebrations in Adelaide, 1974. Cooper was a photographer and member of both the Women’s and Gay Liberation movements in Australia, specifically Adelaide. Her image remains popular and commonly posted in pride images and celebrations of lesbian visibility.

The third postcard shows the bushrangers Andrew Scott (Captain Moonlite- spelling intentional) and James Nesbitt, who met in Pentridge Prison (where, as an aside, Nesbitt repeatedly got in trouble for caring for Scott by bringing him things). They lived together after their release, before commencing their bushranging career across the colonial border in New South Wales. Famously, Nesbitt was killed in a police shoot-out, where the depth of Scott’s emotional response- he was reported to have kissed him as he lay dying in his arms- was remarked on even in the newspapers, without mockery. Scott wore a lock of Nesbitt’s hair as a ring, which he passed on to Nesbitt’s mother prior to his own hanging, writing to her as her ‘other son’. While the courts refused Scott’s request to be buried with Nesbitt, admirers later disinterred Scott and moved his remains to the same location as Nesbitt’s, finally fulfilling the request.

#queer history#gay history#lesbian history#lgbtq+ history#history of sexuality#20th century#wlw history#history#19th century#blak history#aboriginal history#australian history#images of deceased people

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Always Was Always Will Be Aboriginal Land Indigenous Inspirational Activism Gift Aboriginal People Classic T-Shirt by norhan2000)

#findyourthing#redbubble#Always Was Always Will Be Aboriginal Land#Indigenous#activism#Aboriginal#australia#Aboriginal people#Aboriginal land#freedom#culture#lastoffer#norhan2000#inspirational#love#Aboriginal history#aboriginal flag#Aboriginal gift

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Girrakool -place of waters

Brisbane Water National Park was originally established in 1959 when an area of 6,000 hectares was dedicated for public recreation, the park is now more than 12,000ha in size.

Girrakool picnic area was established soon after the appointment of the first ranger, Mr Jack Higgs, in 1961.

The establishment of a picnic area and development of walking trails at Girrakool was carefully planned to provide access to the beautiful waterfalls and abundant native flora. Girrakool was officially opened on 11 September 1965.

This beautiful reserve takes its name from nearby Brisbane Water which can be seen from a number of places within the park. The park is a combination of rugged bushland, beautiful wildflowers and spectacular waterfalls and creeks.

Aboriginal people have used the area for centuries and there are Aboriginal engravings on many of the sandstone outcrops.

The importance of the area for Aboriginal people is reflected in the two Aboriginal places in the park, Bulgandry Art Site Aboriginal Place and Kariong Sacred Land Aboriginal Place."

#steventure#blog#australia#hike#hiking#bushwalk#brisbane water#waterfall#brisbane water national park#girrakool#piles creek#aboriginal history#bushwalking#bushwalking blog#hiking blog#travel blog#darkinyung#goanna#central coast bushwalks#nsw national park

0 notes

Text

"If we look at the evidence presented to us by the explorers, and explain to our children that Aboriginal people did build houses, did build dams, did sow, irrigate, and till the land, did alter the course of rivers, did sew their clothes, and did construct a system of pan-continental government that generated peace and prosperity, it is likely we will admire and love our land all the more. Admiration and love are not sufficient in themselves, but they are the foundation of a more productive interaction with the continent.

"Behaving as if the First Peoples were mere wanderers across the soil and knew nothing about how to grow and care for food resources is a piece of managerial pig-headedness."

From Dark Emu, by Bruce Pascoe

1 note

·

View note

Text

FANNY COCHRANE SMITH // LINGUIST

“She was an Aboriginal linguist. She was born in Tasmania, as is thought to have been the last fluent speaker of its own language. In her final years, she made wax cylinder recordings of Tasmanian Aboriginal songs and speech, which in 2017 were inducted into the UNESCO Australian Memory of the World Register as the only audio recordings of any of Tasmania’s indigenous languages.”

0 notes

Text

On This Day In History

May 27th, 1967: Australians vote overwhelmingly in favor of a constitutional referendum to permit to the Australian government to count Indigenous Australians in the national census and make laws for their benefit.

#history#world history#australian history#indigenous history#australia#aboriginal history#political history

174 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://www.knewtoday.net/resilience-and-revival-five-stories-of-aboriginal-life-in-australia-after-european-invasion/

Resilience and Revival: Five Stories of Aboriginal Life in Australia After European Invasion

The European invasion of Australia in the late 18th century had a profound and lasting impact on the Aboriginal people, the continent’s original inhabitants. The arrival of European settlers brought significant changes to the social, cultural, and political landscape, leading to a complex and often painful history for Aboriginal communities. However, amidst the challenges and injustices, stories of resilience, cultural revival, and a quest for justice have emerged, painting a picture of a people determined to preserve their heritage and create a better future.

In this collection of stories, we delve into five significant narratives that shed light on the experiences of Aboriginal Australians after the European invasion. These stories highlight both the struggles and the triumphs, offering a glimpse into the diverse ways in which Aboriginal communities have navigated the post-invasion era.

From the heart-wrenching tale of the Stolen Generation, where Aboriginal children were forcibly separated from their families to the inspiring fight for land rights and self-determination, these stories encapsulate the profound impact of European colonization on the Aboriginal people and their ongoing efforts to reclaim their cultural identity.

We will also explore the pivotal moment of reconciliation and apology, as the Australian government acknowledged the injustices of the past, offering hope for healing and unity. Additionally, we will delve into the resurgence of Aboriginal art and cultural expression, as Indigenous artists reclaim their narratives and share their rich heritage with the world.

Lastly, we will uncover the remarkable stories of Aboriginal land and sea management practices, where traditional ecological knowledge blends with modern conservation principles, creating sustainable ecosystems and economic opportunities for Aboriginal communities.

These stories weave together a narrative of strength, resilience, and determination among Aboriginal Australians. They provide a deeper understanding of the ongoing journey toward justice, reconciliation, and the revitalization of Aboriginal culture. Through these tales, we are reminded of the importance of acknowledging and respecting the legacy of the Aboriginal people and working towards a more inclusive and harmonious future.

The Stolen Generation

The Stolen Generation refers to a dark chapter in Australian history when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were forcibly removed from their families by the Australian government and placed into institutions or with non-Indigenous foster families. This policy, which spanned from the late 1800s to the 1970s, aimed to assimilate Indigenous children into Western culture, severing their ties to their families, culture, and land.

The impact of the Stolen Generation on individuals and communities was profound and long-lasting. Children were taken away without consent or understanding, often experiencing trauma, loss of cultural identity, and a sense of displacement. Families were torn apart, and the bonds of kinship and community were shattered. The effects of this policy continue to be felt today, with intergenerational trauma and ongoing struggles for healing and reconciliation.

One example that highlights the experiences of the Stolen Generation is the story of Doris Pilkington Garimara, as depicted in her book “Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence” (later adapted into a film). Doris, along with her sister and cousin, was forcibly taken from her mother in 1931 when she was just four years old. They were transported to Moore River Native Settlement, hundreds of miles away from their home.

Determined to return to their family and their traditional lands, the three girls embarked on a remarkable journey, following the Rabbit-Proof Fence that stretched across the Western Australian outback. Despite the challenging conditions and the constant threat of capture, they relied on their knowledge of the land and their resilience to navigate their way home.

Doris Pilkington Garimara’s story, along with countless others, sheds light on the courage, strength, and resilience of the Stolen Generation. It serves as a testament to their enduring connection to their culture and their unyielding spirit in the face of adversity.

The recognition of the Stolen Generation and the injustices they suffered led to a national apology by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 2008. The apology aimed to acknowledge the pain and suffering caused by the forced removals and to begin the process of healing and reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

The stories of individuals like Doris Pilkington Garimara and the countless others impacted by the Stolen Generation serve as a reminder of the ongoing need for understanding, compassion, and support for healing the wounds inflicted upon Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. It is through listening, acknowledging, and learning from these stories that a path toward reconciliation and justice can be forged.

Land Rights Movement

The Land Rights Movement in Australia emerged as a response to the dispossession and marginalization of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from their traditional lands following the European invasion. It sought to address the historical injustices, assert Indigenous rights to land, and regain control over their ancestral territories. The movement gained momentum in the 1960s and 1970s, and its efforts have resulted in significant legal and social changes.

One prominent example of the Land Rights Movement is the Gurindji strike and the subsequent Wave Hill Walk-Off in 1966. Led by Vincent Lingiari, the Gurindji people, were working as cattle station laborers in Wave Hill, Northern Territory, demanding better working conditions and the return of their traditional lands.

The Wave Hill Walk-Off was a groundbreaking event that captured national attention. More than 200 Aboriginal workers, together with their families, left the Wave Hill cattle station, camping at Daguragu (formerly known as Wattie Creek) and refusing to work until their demands were met. Their actions sparked a larger movement for land rights and provided a rallying point for Aboriginal activism across the country.

The Gurindji strike and the Wave Hill Walk-Off led to the establishment of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. This legislation recognized Aboriginal land rights in the Northern Territory and paved the way for the return of land to Indigenous ownership. It was a significant milestone in the Land Rights Movement, empowering Aboriginal communities and enabling them to reclaim their ancestral lands.

Another significant example is the Native Title Act of 1993. This legislation recognized the existence of native title, the recognition of Indigenous land rights based on traditional connections to the land, and established a legal framework for Indigenous communities to make native title claims. The Native Title Act aimed to address the historical injustices and provide a pathway for land rights reconciliation.

The Mabo v Queensland (No 2) case, a landmark High Court decision in 1992, played a pivotal role in the recognition of native title. Eddie Mabo, along with other Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal plaintiffs, challenged the doctrine of terra nullius (the notion that Australia was unoccupied prior to European settlement) and successfully argued for the recognition of native title rights.

These examples highlight the activism, perseverance, and collective efforts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in their fight for land rights. The Land Rights Movement has led to the return of significant areas of land to Indigenous ownership, enabling communities to reconnect with their traditional lands, practice cultural traditions, and exercise self-determination.

The struggle for land rights is ongoing, and Indigenous communities continue to assert their rights and negotiate for recognition and control over their lands. The Land Rights Movement remains a critical aspect of the broader movement for Indigenous rights, self-determination, and reconciliation in Australia.

Reconciliation and the Apology

Reconciliation and the Apology refer to significant steps taken in Australia to acknowledge and address the historical injustices and mistreatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples following the European invasion. These initiatives aim to foster healing, understanding, and a path toward unity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Reconciliation: Reconciliation in Australia involves acknowledging the past injustices, promoting understanding, and working towards a more respectful and equitable future for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The concept emphasizes the importance of building positive relationships, respecting Indigenous cultures and heritage, and addressing the ongoing issues faced by Indigenous communities.

The journey toward reconciliation encompasses various aspects, including education, awareness, community engagement, and policy changes. It involves acknowledging and respecting the diverse cultures, languages, and histories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, as well as supporting self-determination and empowering Indigenous communities.

Apology: The Apology refers to the formal apology delivered by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd on behalf of the Australian government to the Stolen Generations on February 13, 2008. The Stolen Generations were the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were forcibly removed from their families and communities under government policies of assimilation.

In his speech, Rudd acknowledged the pain, trauma, and injustices suffered by the Stolen Generations and their families. The Apology sought to provide recognition, validation, and healing, aiming to restore dignity and respect to those who had endured the devastating impacts of forced removal.

The Apology represented a significant moment in Australian history, symbolizing a national commitment to acknowledging past wrongs and working towards reconciliation. It sparked hope for a renewed relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, promoting understanding, healing, and a shared future.

Following the Apology, various initiatives and programs have been implemented to support reconciliation efforts, including increased funding for Indigenous education, health services, and community development. National Reconciliation Week, held annually from May 27 to June 3, provides an opportunity for Australians to reflect on the importance of reconciliation and to participate in events that promote understanding and unity.

Reconciliation and the Apology are ongoing processes, requiring continued commitment, understanding, and meaningful actions from all Australians. The goal is to create a more inclusive, just, and equitable society where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can thrive, celebrate their cultures, and contribute to the nation as equal partners.

These initiatives mark important milestones in Australia’s journey towards healing, recognition, and forging stronger relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. They represent a commitment to learning from the past, acknowledging the ongoing impacts of colonization, and working towards a shared future of reconciliation and justice.

Land and Sea Management

Land and Sea Management in Australia refers to the Indigenous-led practices and initiatives aimed at preserving and sustainably managing the natural environment, including land, waterways, and marine ecosystems. These practices combine traditional ecological knowledge with modern conservation principles to ensure the long-term sustainability of ecosystems while supporting Indigenous cultural connections to the land and sea.

Indigenous land and sea management initiatives recognize the deep understanding and stewardship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who have maintained sustainable relationships with the environment for thousands of years. These initiatives encompass various activities, such as fire management, cultural mapping, species monitoring, habitat restoration, and sustainable fishing practices.

One notable example of Indigenous land and sea management is the work of the Yolngu people in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory. Through their organization, the Dhimurru Aboriginal Corporation, the Yolngu people have been actively involved in caring for their ancestral lands and coastal areas.

Dhimurru’s initiatives include fire management practices, where controlled burning is utilized to maintain healthy ecosystems, reduce the risk of wildfires, and promote the regeneration of native plants and animals. The Yolngu people also engage in sea management, monitoring and protecting marine species, and implementing sustainable fishing practices to ensure the preservation of coastal resources.

Another example is the Djelk Rangers program in West Arnhem Land. The program, established by the traditional owners of the region, involves Indigenous rangers working to conserve and manage the land, rivers, and coastal areas. The Djelk Rangers are involved in activities such as weed and pest management, cultural site protection, and land and waterway monitoring. They also collaborate with scientists and researchers to combine traditional knowledge with scientific approaches, fostering a holistic approach to land and sea management.

Indigenous land and sea management practices not only contribute to biodiversity conservation but also support cultural preservation, economic development, and community empowerment. These initiatives provide employment and training opportunities for Indigenous communities, enabling them to reconnect with their cultural heritage, pass on traditional knowledge to future generations, and assert their rights and responsibilities as custodians of the land and sea.

The success of Indigenous land and sea management programs has led to increased recognition and support from government, non-governmental organizations, and the broader community. Collaborative partnerships have been formed, enabling Indigenous communities to have a greater say in land management decisions and policies.

Overall, Indigenous land and sea management initiatives exemplify the intersection of environmental conservation, cultural preservation, and community development. These practices demonstrate the importance of traditional ecological knowledge and the role of Indigenous communities as custodians of the land and sea, leading to more sustainable and inclusive approaches to environmental stewardship.

Aboriginal Art and Cultural Revival

Aboriginal Art and Cultural Revival in Australia has played a vital role in preserving and celebrating Indigenous traditions, stories, and cultural heritage. Aboriginal art encompasses a wide range of artistic expressions, including paintings, sculptures, carvings, weaving, and more. It is deeply rooted in the spiritual and cultural beliefs of Aboriginal communities and serves as a powerful medium for storytelling and connection to the land.

Aboriginal art has gained international recognition for its unique styles, vibrant colors, and intricate designs. It provides a visual representation of the rich cultural diversity and deep connection to Country held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

One example of Aboriginal art and cultural revival is the Western Desert Art Movement. It emerged in the 1970s in remote communities of Central Australia, such as Papunya, and is often credited as the catalyst for the contemporary Aboriginal art movement. Artists like Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri and Emily Kame Kngwarreye played significant roles in popularizing Aboriginal art and introducing it to a broader audience.

The Western Desert Art Movement revitalized traditional art practices and storytelling techniques, leading to the establishment of art centers in Aboriginal communities. These art centers provide a space for artists to create and share their work, ensuring cultural knowledge is passed down to future generations.

Contemporary Aboriginal artists draw inspiration from Dreamtime stories, ancestral connections, and the natural environment. They employ a diverse range of styles and techniques, ranging from dot paintings to intricate cross-hatching and more abstract forms. Each artwork holds deep cultural significance and often carries messages related to identity, land rights, spirituality, and social issues.

The success and recognition of Aboriginal art have also brought economic opportunities to Indigenous communities. Art sales, exhibitions, and licensing agreements provide a sustainable income source for artists and their communities, fostering self-determination and empowering Aboriginal individuals and art centers.

In recent years, Aboriginal art has been increasingly incorporated into public spaces, galleries, and museums, both in Australia and internationally. It serves as a means of education, raising awareness about Aboriginal culture and history, and challenging stereotypes and misconceptions.

The cultural revival facilitated by Aboriginal art extends beyond visual representations. It has influenced other creative disciplines, including music, dance, storytelling, and film, contributing to a broader renaissance of Indigenous cultural practices and expressions.

Aboriginal art and cultural revival not only provide a platform for Indigenous voices and narratives but also contribute to a deeper understanding and appreciation of Australia’s rich cultural tapestry. They serve as a testament to the resilience and ongoing presence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and their commitment to preserving and sharing their cultural heritage with the world.

#Aboriginal Art#Aboriginal History#Cultural Revival#European Invasion#Indigenous Knowledge#Land Rights Movement#Reconciliation#Stolen Generation

0 notes

Text

MY AUSTRALIAN ADVENTURE, PT. XVII - A VISIT TO THE MUSEUM/ART GALLERY IN PERTH

MY AUSTRALIAN ADVENTURE, PT. XVII – A VISIT TO THE MUSEUM/ART GALLERY IN PERTH

Wherever I travel, I always make a point of visiting the museums and art galleries to get a better understanding of time, place, culture, history…and back home in Perth was no exception. I grew up and was educated there in the 60s under the old colonial school system that had been so white-washed as to obscure any references to the first Australians, the aboriginal guardians of the land, sea and…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

there was a swedish guy in like the early 1900s that literally just traveled to Australia, attended a funeral of an indigenous person and then HE CAME BACK A FEW WEEKS LATER TO DIG UP THE BONES TO KEEP IN HIS COLLECTION!!!!

DO YOU HEAR ME??!!!

HE WENT ON A FUNERAL AND THEN CAME BACK TO DIG UP THE BONES!!!!!!!

Thankfully the aboriginal people there had heard he had dug up bones previously and they moved the grave.

AND WHEN HE DISCOVERED THIS HE GOT MAD AND SAID THE ABORIGINAL PEOPLE COULDN'T BE TRUSTED

AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH

#the guys name was Erik Mjöberg for anyone wondering#he was absolutely disgusting AND SMUGGLED BONES OF ABORIGINAL PEOPLE OUT OF AUSTRALIA#If this doesn't tell you about attitudes at the time towards indigenous people from europeans#I don't know what does#Sweden#History#aboriginal#hate crimes tw#i don't know if this counts as a hate crime but I'll still put it there to be safe#regardless it's still definitely a crime towards and disgusting treatment of indigenous people

1K notes

·

View notes