#alice through the looking glass 1966

Text

I want the 1966 Alice through the looking glass to get popular so there can be minor passive aggressive discourse about how people only like the movie for the "clowncore" character like what happened with 1976's "The Adventures of Buratino" in 2021

#i actually made a few people watch this movie because of an edit of this guy. one of the jabberwock too#alice through the looking glass 1966#alice through the looking glass#alice's adventures in wonderland#the adventures of buratino#alice in wonderland#clowncore#jester core#jester#clownblr

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

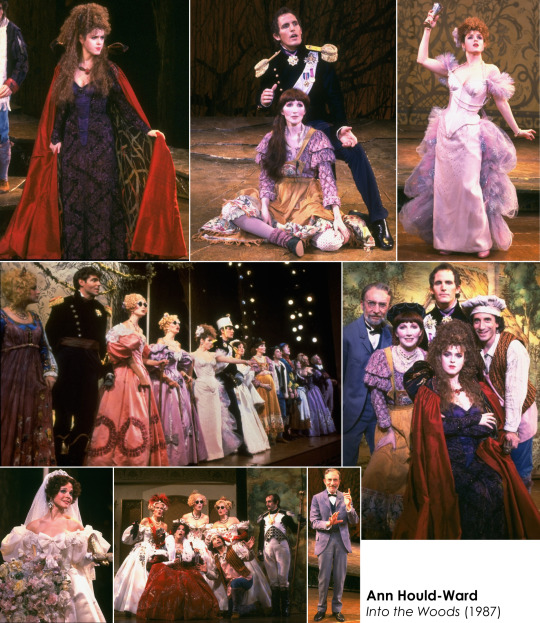

Court Gowns from Alice Through The Looking Glass (1966).. Costumes created by Bob Mackie..

535 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice Through the Looking Glass 1966

This adaptation was okay... Not the best, not the worst. This Alice was kind of mellow? I don't have much else to say. I wanted to draw her with her smile, which was a challenge. Expressions are hard! But I like when Alice has more than the usual "huh?" expression.

#alice#curiouserandcuriouser#curiouser and curiouser#through the looking glass#alice through the looking glass#alice in wonderland#lewis carroll#movie#alice timeline#1966#movie adaptation#illustration#alice liddell#drawing of the week#pen drawing#drawing#pen sketch#sketch#stippling#traditional art#my art

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

auctioned dresses from the show, alice through the looking glass (1966)

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

A retrospective on some of Broadway’s most important female costume designers across the last century

How much is our memory or perception of a production influenced by the manner in which we visually comprehend the characters for their physical appearance and attire? A lot.

How much attention in memory is often dedicated to celebrating the costume designers who create the visual forms we remember? Comparatively, not much.

Delving through the New York Public Library archives of late, I found I was able to zoom into pictures of productions like Sunday in the Park with George at a magnitude greater than before.

In doing so, I noticed myself marvelling at finer details on the costumes that simply aren’t visible from grainy 1985 proshots, or other lower resolution images.

And marvel I did.

At first, I began to set out to address the contributions made to the show by designer Patricia Zipprodt in collaboration with Ann Hould-Ward. Quickly I fell into a (rather substantial) tangent rabbit hole – concerning over a century’s worth of interconnected designers who are responsible for hundreds of some of the most memorable Broadway shows between them.

It is impossible to look at the work of just one or two of these women without also discussing the others that came before them or were inspired by them.

Journey with me then if you will on this retrospective endeavour to explore the work and legacy that some of these designers have created, and some of the contexts in which they did so.

A set of podcasts featuring Ann Hould-Ward, including Behind the Curtain (Ep. 229) and Broadway Nation (Eps. 17 and 18), invaluably introduce some of the information discussed here and, most crucially, provide a first-hand, verbal link back to this history. The latter show sets out the case for a “succession of dynamic women that goes back to the earliest days of the Broadway musical and continues right up to today”, all of whom “were mentored by one or more of the great [designers] before them, [all] became Tony award-winning [stars] in their own right, and [all] have passed on the [craft] to the next generation.”

A chronological, linear descendancy links these designers across multiple centuries, starting in 1880 with Aline Bernstein, then moving to Irene Sharaff, then to Patricia Zipprodt, then to the present day with Ann Hould-Ward. Other designers branch from or interact with this linear chronology in different ways, such as Florence Klotz and Ann Roth – who, like Patricia Zipprodt, were also mentored by Aline Bernstein – or Theoni V. Aldredge, who stands apart from this connected tree, but whose career closely parallels the chronology of its central portion. There were, of course, many other designers and women also working within this era that provided even further momentous contributions to the world of costume design, but in this piece, the focus will remain primarily on these seven figures.

As the main creditor of the designs for Sunday in the Park with George, let’s start with Patricia (Pat) Zipprodt.

Born in 1925, Pat studied at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in New York after winning a scholarship there in 1951. Through teaching herself “all of costume history by studying materials at the New York Public Library”, she passed her entrance exam to the United Scenic Artists Union in 1954. This itself was a feat only possible through Aline Bernstein’s pioneering steps in demanding and starting female acceptance into this same union for the first time just under 30 years previously.

Pat made her individual costume design debut a year after assisting Irene Sharaff on Happy Hunting in 1956 – Ethel Merman’s last new Broadway credit. Of the more than 50 shows she subsequently designed, some of Pat’s most significant musicals include:

She Loves Me (1963)

Fiddler on the Roof (1964)

Cabaret (1966)

Zorba (1968)

1776 (1969)

Pippin (1972)

Mack & Mabel (1974)

Chicago (1975)

Alice in Wonderland (1983)

Sunday in the Park with George (1984)

Sweet Charity (1986)

Into the Woods (1987) - preliminary work

Other notable play credits included:

The Little Foxes (1967)

The Glass Menagerie (1983)

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1990)

Yes. One person designed all of those shows. Many of the most beloved pieces in modern musical theatre history. Somewhat baffling.

Her work notably earned her 11 Tony nominations, 3 wins, an induction into the Theatre Hall of Fame in 1992, and the Irene Sharaff award for lifetime achievement in costume design in 1997.

By 1983, Pat was one of the most well-respected designers of her era. When the offer for Sunday in the Park with George came in, she was less than enamoured by being confined to the ill-suited basements at Playwright’s Horizons all day, designing full costumes for a story not even yet in existence. From-the-ground-up workshops are common now, but at the time, Sunday was one of the first of its kind.

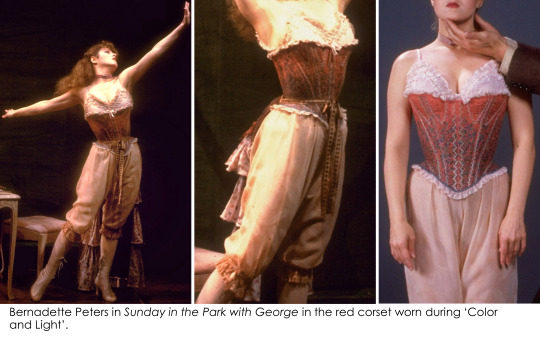

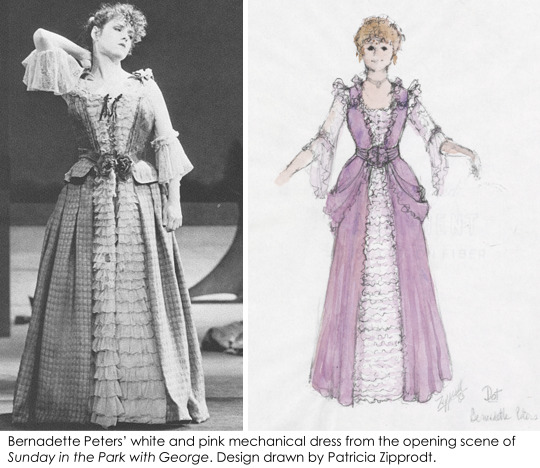

Rather than flatly declining, she asked Ann Hould-Ward, previously her assistant and intern who had now been designing for 2-3 years on her own, if she was interested in collaborating. She was. The two divided the designing between them, like Pat creating Bernadette’s opening pink and white dress, and Ann her final red and purple dress.

Which indeed leads to the question of the infamous creation worn in the opening number. No attemptedly comprehensive look at the costumes in Sunday would be complete without addressing it or its masterful mechanics.

To enable Bernadette to spring miraculously and seemingly effortlessly from her outer confines, Ann and Pat enlisted the help of a man with a “Theatre Magics” company in Ohio. Dubbed ‘The Iron Dress’, the gasp-inducing motion required a wire frame embedded into the material, entities called ‘moonwalker legs and feet’, and two garage door openers coming up through the stage to lever the two halves apart. The mechanism – highly impressive in its periods of functionality – wasn’t without its flaws. Ann recalls “there were nights during previews where [Bernadette] couldn’t get out of the dress”. Or worse, a night where “the dress closed up completely. And it wouldn’t open up again!”. As Bernadette finished her number, there was nothing else within her power she could do, so she simply “grabbed it under her arm and carried it off stage.”

What visuals. Evidently, the course of costume design is not always plain sailing.

This sentiment is exhibited in the fact design work is a physical materialisation of other creators’ visions, thus foregrounding the tricky need for collaboration and compromise. This is at once a skill, very much part of the job description, and not always pleasant – in navigating any divides between one’s own ideas and those of other people.

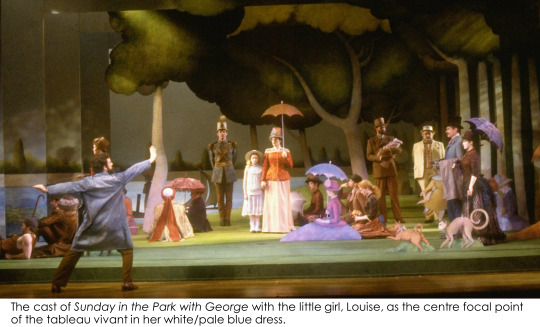

Sunday in the Park with George was no exception in requiring such a moment of compromise and revision. With the show already on Broadway in previews, Stephen Sondheim decreed the little girl Louise’s dress “needs to be white” – not the “turquoisey blue” undertone Pat and Ann had already created it with. White, to better spotlight the painting’s centre.

Requests for alterations are easier to comprehend when they are done with equanimity and have justification. Sondheim said he would pay for the new dress himself, and in Seurat’s original painting, the little girl is very brightly the focal centre point of the piece. On this occasion, all agreed that Sondheim was “absolutely right”. A new dress was made.

Other artistic differences aren’t always as amicable.

In Pat Zipprodt’s first show, Happy Hunting with Ethel Merman in 1956, some creatives and directors were getting in vociferous, progress-stopping arguments over a dress and a scene in which Ethel was to jump over a fence. Then magically, the dress went missing. Pat was working at the time as an assistant to the senior Irene Sharaff, and Pat herself was the one to find the dress the next morning. It was in the basement. Covered in black and wholly unwearable. Sharaff had spray painted the dress black in protest against the “bickering”. Indeed, Sharaff disappeared, not to be seen again until the show arrived on Broadway.

Those that worked with her soon found that Sharaff was one to be listened to and respected – as Hal Prince did during West Side Story. After the show opened in 1957, Hal replaced her 40 pairs of meticulously created and individually dyed, battered, and re-dyed jeans with off-the-rack copies. His reasoning was this: “How foolish to be wasting money when we can make a promotional arrangement with Levi Strauss to supply blue jeans free for program credit?” A year later, he looked at their show, and wondered “What’s happened?”

What had happened was that the production had lost its spark and noticeable portions of its beauty, vibrancy, and subtle individuality. Sharaff’s unique creations quickly returned, and Hal had learned his lesson. By the time Sharaff’s mentee, Pat, had “designed the most expensive rags for the company to wear” with this same idiosyncratic dyeing process for Fiddler on the Roof in 1964, Hal recognised the value of this particularity and the disproportionately large payoff even ostensibly simple garments can bring.

Irene Sharaff is remembered as one of the greatest designers ever. Born in 1910, she was mentored by Aline Bernstein, first assisting her on 1928’s original staging of Hedda Gabler.

Throughout her 56 year career, she designed more than 52 Broadway musicals. Some particularly memorable entities include:

The Boys from Syracuse (1938)

Lady in the Dark (1943)

Candide (1956)

Happy Hunting (1956)

Sweet Charity (1966)

The King and I (1951, 1956)

West Side Story (1957, 1961)

Funny Girl (1964, 1968)

For the last three productions, she would reprise her work on Broadway in the subsequent and indelibly enduring film adaptations of the same shows.

Her work in the theatre earned her 6 Tony nominations and 1 win, though her work in Hollywood was perhaps even more well rewarded – earning 5 Academy Awards from a total of 15 nominations.

Some of Sharaff’s additional film credits included:

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944)

Ziegfeld Follies (1946)

An American in Paris (1951)

Call Me Madam (1953)

A Star is Born (1954) – partial

Guys and Dolls (1955)

Cleopatra (1963)

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966)

Hello Dolly! (1969)

Mommie Dearest (1981)

It’s a remarkable list. But it is too more than just a list.

Famously, Judy’s red scarlet ballgown in Meet Me in St. Louis was termed the “most sophisticated costume [she’d] yet worn on the screen.”

It has been written that Sharaff’s “last film was probably the only bad one on which she worked,” – the infamous pillar of camp culture, Mommie Dearest, in 1981 – “but its perpetrators knew that to recreate the Hollywood of Joan Crawford, it required an artist who understood the particular glamour of the Crawford era.” And at the time, there were very few – if any – who could fill that requirement better than Irene Sharaff.

The 1963 production of Cleopatra is perhaps an even more infamous endeavour. Notoriously fraught with problems, the film was at that point the most expensive ever made. It nearly bankrupted 20th Century Fox, in light of varying issues like long production delays, a revolving carousel of directors, the beginning of the infamous Burton/Taylor affair and resulting media storm, and bouts of Elizabeth’s ill-health that “nearly killed her”. In that turbulent environment, Sharaff is highlighted as one of the figures instrumental in the film’s eventual completion – “adjusting Elizabeth Taylor’s costumes when her weight fluctuated overnight” so the world finally received the visual spectacle they were all ardently anticipating.

But even beyond that, Sharaff’s work had impacts more significantly and extensively than the immediate products of the shows or films themselves. Within a few years of her “vibrant Thai silk costumes for ‘The King and I’ in 1951, …silk became Thailand’s best-known export.” Her designs changed the entire economic landscape of the country.

It’s little wonder that in that era, Sharaff was known as “one of the most sought-after and highest-paid people in her profession.” With discussions and favourable comparisions alongside none other than Old Hollywood’s most beloved designer, Edith Head, Irene deserves her place in history to be recognised as one of the foremost significant pillars of the design world.

In this respected position, Irene Sharaff was able to pass on her knowledge by mentoring others too as well as Patricia Zipprodt, like Ann Roth and Florence Klotz, who have in turn gone on to further have their own highly commendable successes in the industry.

Florence “Flossie” Klotz, born in 1920, is the only Broadway costume designer to have won six Tony awards. She did so, all of them for musicals, and all of them directed by Hal Prince, in a marker of their long and meaningful collaboration.

Indeed, Flossie’s life partner was Ruth Mitchell – Hal’s long-time assistant, and herself legendary stage manager, associate director and producer of over 43 shows. Together, Flossie and Ruth were dubbed a “power couple of Broadway”.

Flossie’s shows with Hal included:

Follies (1971)

A Little Night Music (1973)

Pacific Overtures (1976)

Grind (1985)

Kiss of the Spiderwoman (1993)

Show Boat (1995)

And additional shows amongst her credits extend to:

Side by Side by Sondheim (1977)

On the Twentieth Century (1978)

The Little Foxes (1981)

A Doll’s Life (1982)

Jerry’s Girls (1985)

Earlier in her career, she would first find her footing as an assistant designer on some of the Golden Age’s most pivotal shows like:

The King and I (1951)

Pal Joey (1952)

Silk Stockings (1955)

Carousel (1957)

The Sound of Music (1959)

The original production of Follies marked the first time Florence was seriously recognised for her work. Before this point, she was not yet anywhere close to being considered as having broken into the ranks of Broadway’s “reigning designers” of that era. Follies changed matters, providing both an indication of the talent of her work to come, and creating history in being commended for producing some of the “best costumes to be seen on Broadway” in recent memory – as Clive Barnes wrote in The New York Times. Fuller discussion is merited given that the costumes of Follies are always one of the show’s central points of debate and have been crucial to the reception of the original production as well as every single revival that has followed in the 50 years since.

In this instance, Ted Chapin would record from his book ‘Everything Was Possible: The Birth of the Musical ‘Follies’ how “the costumes were so opulent, they put the show over-budget.” Moreover, that “talking about the show years later, [Florence] said the costumes could not be made today. ‘Not only would they cost upwards of $2 million, but we used fabrics from England that aren’t even made anymore.’” Broadway then does indeed no longer look like Broadway now.

This “surreal tableau” Flossie created, including “three-foot-high ostrich feather headdresses, Marie Antoinette wigs adorned with musical instruments and birdcages, and gowns embellished with translucent butterfly wings”, remains arguably one of the most impressive and jaw-dropping spectacles to have ever graced a Broadway stage even to this day.

As for Ann Roth, born in 1931, she is still to this day making her own history – recently becoming the joint eldest nominee at 89 for an Oscar (her 5th), for her work on 2020′s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. Now as of April 26th, Ann has just made history even further by becoming the oldest woman to win a competitive Academy Award ever. She has an impressive array of Hollywood credits to her name in addition to a roster of Broadway design projects, which have earned her 12 Tony nominations.

Some of her work in the theatre includes:

The Women (1973)

The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1978)

They're Playing Our Song (1979)

Singin' in the Rain (1985)

Present Laughter (1996)

Hedda Gabler (2009)

A Raisin in the Sun (2014)

Shuffle Along (2016)

The Prom (2018)

Making her way over to Hollywood in the ‘70s, she has left an indelible and lasting visual impact on the arts through films like:

Klute (1971)

The Goodbye Girl (1977)

Hair (1979)

9 to 5 (1980)

Silkwood (1983)

Postcards from the Edge (1990)

The Birdcage (1996)

The Hours (2002)

Mamma Mia! (2008)

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020)

It’s clear from this branching 'tree' to see how far the impact of just one woman passing on her time and knowledge to others who are starting out can spread.

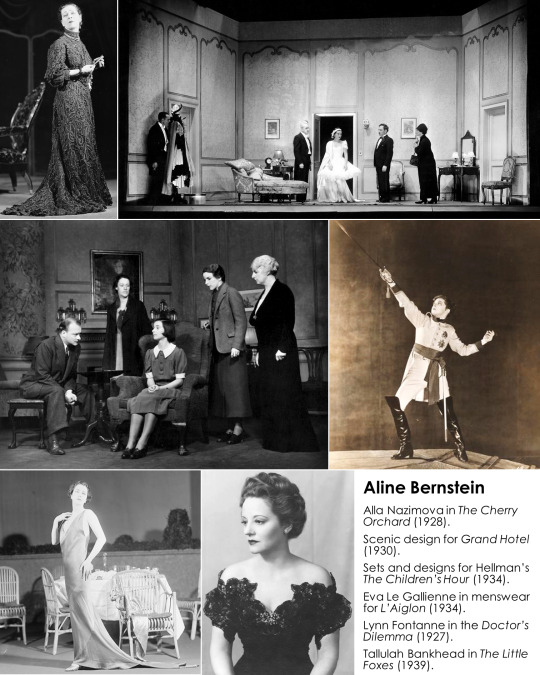

This art of acting as a conduit for valuable insights was something Irene Sharaff had learned from her own mentor and predecessor, Aline Bernstein. Aline was viewed as “the first woman in the [US] to gain prominence in the male-dominated field of set and costume design,” and was too a strong proponent of passing on the unique knowledge she had acquired as a pioneer and forerunner in the field.

Born in 1880, Bernstein is recognised as “one of the first theatrical designers in New York to make sets and costumes entirely from scratch and craft moving sets” while Broadway was still very much in its infancy of taking shape as the world we know today. This she did for more than one hundred shows over decades of her work in the theatre. These shows included the spectacular Grand Street Follies (1924-27), and original premier productions of plays like some of the following:

Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler (1928)

J.M Barrie’s Peter Pan (1928)

Grand Hotel (1930)

Phillip Barry’s Animal Kingdom (1932)

Chekov’s The Seagull (1937)

Both Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour (1934) and The Little Foxes (1939)

Beyond direct design work, Bernstein founded what was to become the Neighbourhood Playhouse (the notable New York acting school) and was influential in the “Little Theatre movement that sprung up across America in 1910”. These were the “forerunners of the non-profit theatres we see today” and she continued to work in this realm even after moving into commercial theatre.

Bernstein also established the Museum of Costume Art, which later became the Costume Institute of the Met Museum of Art, where she served as president from 1944 to her death in 1955. This is what the Met Gala raises money for every year. So for long as you have the world’s biggest celebrities parading up and down red carpets in high fashion pieces, you have Aline Bernstein to remember – as none of that would be happening without her.

During the last fifteen years of her life, Bernstein taught and served as a consultant in theatre programs at academic institutions including Yale, Harvard, and Vassar – keen to connect the community and facilitate an exchange of wisdom and information to new descendants and the next generation.

Many designers came somewhere out of this linear descendancy. One notable exception, with no American mentor, was Theoni V. Aldredge. Born in 1922 and trained in Greece, Theoni emigrated to the US, met her husband, Tom Aldredge – himself of Into the Woods and theatre notoriety – and went on to design more than 100 Broadway shows. For her work, she earned 3 Tony wins from 11 nominations from projects such as:

Anyone Can Whistle (1964)

A Chorus Line (1975)

Annie (1977)

Barnum (1980)

42nd Street (1980)

Woman of the Year (1981)

Dreamgirls (1981)

La Cage aux Folles (1983)

The Rink (1984)

One of the main features that typify Theoni’s design style and could be attributed to a certain unique and distinctive “European flair” is her strong use of vibrant colour. This is a sentiment instantly apparent in looking longitudinally at some of her work.

In Ann Hould-Ward’s words, Theoni speaks to the “great generosity” of this profession. Theoni went out of her way to call Ann apropos of nothing early in the morning at some unknown hotel just after Ann won her first Tony for Beauty and the Beast in 1994, purring “Dahhling, I told you so!” These were women that had their disagreements, yes, but ultimately shared their knowledge and congratulated each other for their successes.

Similar anecdotal goodwill can be found in Pat Zipprodt’s call to Ann on the night of the 1987 Tony’s – where Ann was nominated for Into the Woods – with Pat singing “Have wonderful night! You’re not gonna win! …[laugh] but I love you anyway!”

This well-wishing phone call is all the more poignant considering Pat was originally involved with doing the costumes for Into the Woods, in reprise of their previous collaboration on Sunday in the Park with George.

If, for example, Theoni instinctively is remembered for bright colour, one of the features that Pat is first remembered for is her dedicated approach to research for her designs. Indeed, the New York Public Library archives document how the remaining physical evidence of this research she conducted is “particularly thorough” in the section on Into the Woods. Before the show finally hit Broadway in 1987 with Ann Hould-Ward’s designs, records show Pat had done extensive investigation herself into materials, ideas and prospective creations all through 1986.

Both Ann and Pat worked on the show out of town in try-outs at the Old Globe theatre in San Diego. But when it came to negotiating Broadway contracts, the situation became “tricky” and later “untenable” with Pat and the producers. Ann was “allowed to step in and design” the show alone instead.

The lack of harboured resentment on Patricia’s behalf speaks to her character and the pair’s relationship, such that Ann still considered her “my dear and beloved friend” for over 25 years, and was “at [Pat’s] bed when she died”.

Though they parted ways ultimately for Into the Woods, you can very much feel a continuation between their work on Sunday in the Park with George a few years previously, especially considering how tactile the designs appear in both shows. This tactility is something the shows’ book writer and director, James Lapine, was specific about. Lapine would remark in his initial ideas and inspirations that he wanted a graphic quality to the costumes on this occasion, like “so many sketches of the fairy-tales do”.

Ann fed that sentiment through her final creations, with a wide variety of materials and textures being used across the whole show – like “ribbons with ribbons seamed through them”, “all sorts of applique”, “frothy organzas and rembriodered organzas”. A specific example documents how Joanna Gleason’s shawl as the Baker’s Wife was pieced together, cut apart, and put back together again before resembling its final form.

This highly involved principle demonstrates another manner of inventive design that uses a different method but maintains the aim of particularity as discussed previously with Patricia and Irene’s complex dyeing and re-dyeing process. Pushing the confines of what is possible with the materials at hand to create a variety of colours, shades, and textures ultimately produces visual entities that are complex to look at. Confusing the eye like this “holds attention longer”, Ann maintains, which makes viewers look more intricately at individual segments of the production, and enables the costume design to guide specific focus by not immediately ceding attention elsewhere.

Understanding the methods behind the resultant impacts of a show can be as, if not more, important and interesting than the final product of the show itself sometimes. A phone call Ann had last August with James Lapine reminds us this is a notion we may be treated more to in the imminent future, when he called to enquire as to the location of some design sketches for the book he is working on (Putting It Together: How Stephen Sondheim and I Created 'Sunday in the Park with George') to document more thoroughly the genesis of the pair’s landmark and beloved musical.

In continuation of the notion that origin stories contain their own intrinsic value beyond any final product, Ann first became Pat’s intern through a heart-warming and tenacious tale. Ann sent letters to three notable designers when finishing graduate school. Only Patricia Zipprodt replied, with a message to say she “didn’t have anything now but let me think about it and maybe in the future.” It got to the future, and Ann took the encouragement of her previous response to try and contact Pat again. Upon being told she was out of town with a show, Ann proceeded to chase Pat through various phone books and telephone wires across different states and theatres until she finally found her. She was bolstered by the specifics of their call and ran off the phone to write an imploring note – hinging on the premise of a shared connection to Montana. She took an arrow, stabbed it through a cowboy hat, put it in a box with the note that was written on raw hide, and mailed it to New York with bated breath and all of her hopes and wishes.

Pat was knife-edgingly close to missing the box, through a matter of circumstance and timing. Importantly, she didn’t. Ann got a response, and it boded well: “Alright alright alright! You can come to New York!”

Subsequently, Ann’s long career in the design world of the theatre has included notable credits such as:

Sunday in the Park with George (1984)

Into the Woods (1987, 1997)

Falsettos (1992)

Beauty and the Beast (1994, 1997)

Little Me (1998)

Company (2006)

Road Show (2008)

The People in the Picture (2011)

Merrily We Roll Along (1985, 1990, 2012, segment in Six by Sondheim 2013)

Passion (2013)

The Visit (2015)

The Color Purple (2015)

The Prince of Egypt (2021)

From early days in the city sleeping on a piece of foam on a friend’s floor, to working collaboratively alongside Pat, to using what she’d learnt from her mentor in designing whole shows herself, and going on to win prestigious awards for her work – the cycle of the theatre and the importance of handing down wisdom from those who possess it is never more evident.

As Ann summarises it meaningfully, “the theatre is a continuing, changing, evolving, emotional ball”. It’s raw, it’s alive, it needs people, it needs stories, it needs documentation of history to remember all that came before.

In periods where there can physically be no new theatre, it’s made ever the more clear for the need not to forget what value there is in the tales to be told from the past.

Through this retrospective, we’ve seen the tour de force influence of a relatively small handful of women shaping a relatively large portion of the visual scape of some of Broadway’s brightest moments.

But it’s significant to consider how disproportionate this female impact was, in contrast with how massively male dominated the rest of the creative theatre industry has been across the last century.

Assessing variations in attitudes and approaches to relationships and families in these women in the context of their professional careers over this time period presents interesting observations. And indeed, manners in which things have changed over the past hundred years.

As Ann Hould-Ward speaks of her experiences, one of her reflections is how much this was a “very male dominated world”. And one that didn’t accommodate for women with families who also wanted careers. As an intern, she didn’t even feel she could tell Patricia Zipprodt about the existence of her own young child until after 6 months of working with her. With all of these male figures around them, it would be often questioned “How are you going to do the work? How are you going to manage [with a family]?”, and that it was “harder to convince people that you were going to be able to do out-of-towns, to be able to go places.” Simply put, the industry “didn't have many designers who were married with children.”

Patricia herself in the previous generation demonstrates this restricting ethos. “In 1993, Zipprodt married a man whose proposal she had refused some 43 years earlier.” She had just newly graduated college and “she declined [his proposal] and instead moved to New York.” Faced with the family or career conundrum, she chose the latter. By the 1950s, it then wasn’t seen as uncommon to have both, it was seen as impossible.

Her husband died just five years after the pair were married in 1998, as did Patricia herself the following year. One has to wonder if alternative decisions would’ve been made and lives lived differently if she’d experienced a different context for working women in her younger life.

But occupying any space in the theatre at all was only possible because of the efforts of and strides made by women in previous generations.

When Aline Bernstein first started designing for Broadway theatre in 1916, women couldn’t even vote. She became the first female member of the United Scenic Artists of America union in 1926, but only because she was sworn in under the false and male moniker of brother Bernstein. In fact, biographies often centralise on her involvement in a “passionate” extramarital love affair with novelist Thomas Wolfe – disproportionately so for all of her remarkable contributions to the theatrical, charitable and academic worlds, and instead having her life defined through her interactions with men.

As such, it is apparent how any significant interactions with men often had direct implications over a woman’s career, especially in this earlier half of the century. Only in their absence was there comparative capacity to flourish professionally.

Irene Sharaff had no notable relationships with men. She did however have a significant partnership with Chinese-American painter and writer Mai-mai Sze from “the mid-1930s until her death”. Though this was not (nor could not be) publicly recognised or documented at the time, later by close acquaintances the pair would be described as a “devoted couple”, “inseparable”, and as holding “love and admiration for one another [that] was apparent to everyone who knew them.” This manner of relationship for Irene in the context of her career can be theorised as having allowed her the capacity to “reach a level of professional success that would have been unthinkable for most straight women of [her] generation”.

Moving forwards in time, Irene and Mai-mai presently rest where their ashes are buried under “two halves of the same rock” at the entrance to the Music and Meditation Pavilion at Lucy Cavendish College in Cambridge, which was “built following a donation by Sharaff and Sze”. I postulate that this site would make for an interesting slice of history and a perhaps more thought-provoking deviation for tourists away from being shepherded up and down past King’s College on King’s Parade as more usually upon a visit to Cambridge.

In this more modern society at the other end of this linear tree of remarkable designers, options for women to be more open and in control of their personal and professional lives have increased somewhat.

Ann Hould-Ward later in her career would no longer “hide that [she] was a mother”, in fear of not being taken seriously. Rather, she “made a concerted effort to talk about [her] child”, saying “because at that point I had a modicum of success. And I thought it was supportive for other women that I could do this.”

If one aspect passed down between these women in history are details of the craft and knowledge accrued along the way, this statement by Ann represents an alternative facet and direction that teaching of the future can take. Namely, that by showing through example, newer generations will be able to comprehend the feasibility of occupying different options and spaces as professional women. Existing not just as designers, or wives, or mothers, or all, or one – but as people, who possess an immense talent and skill. And that it is now not just possible, but common, to be multifaceted and live the way you want to live while working.

This is not to say all of the restrictions and barriers faced by women in previous generations have been removed, but rather that as we build a larger wealth of history of women acting with autonomy and control to refer back to, things can only get easier to build upon for the future.

Who knows what Broadway and theatre in general will look like when it returns – both on the surface with respect to this facet of costume design, and also more deeply as to the inner machinations of how shows are put together and presented. The largely male environment and the need to tick corporate and commercial boxes will not have vanished. One can only hope that this long period of stasis will have foregrounded the need and, most importantly, provided the time to revaluate the ethos in which shows are often staged, and the ways in which minority groups – like women – are able to work and be successful within the theatre in all of the many shows to come.

Notable sources:

Photographs – predominantly from the New York Public Library digital archives.

IBDB – the Internet Broadway Database.

Broadway Nation Podcast (Eps. #17 and #18), David Armstrong, featuring Ann Hould-Ward, 2020.

Behind the Curtain: Broadway’s Living Legends Podcast (Ep. #229), Robert W Schneider and Kevin David Thomas, featuring Ann Hould-Ward, 2020.

Sense of Occasion, Harold Prince, 2017.

Everything Was Possible: The Birth of the Musical ‘Follies’, Ted Chapin, 2003.

Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954–1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes, Stephen Sondheim, 2010.

The Complete Book of 1970s Broadway Musicals, Dan Deitz, 2015.

The Complete Book of 1980s Broadway Musicals, Dan Dietz, 2016.

Inventory of the Patricia Zipprodt Papers and Designs at the New York Public Library, 2004 – https://www.nypl.org/sites/default/files/archivalcollections/pdf/thezippr.pdf

Extravagant Crowd’s Carl Van Vecten’s Portraits of Women, Aline Bernstein – http://brbl-archive.library.yale.edu/exhibitions/cvvpw/gallery/bernstein.html

Jewish Heroes & Heroines of America: 150 True Stories of American Jewish Heroism – Aline Bernstein, Seymour Brody, 1996 – https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/aline-bernstein

Ann Hould-Ward Talks Original “Into the Woods” Costume Designs, 2016 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4EPe77c6xzo&ab_channel=Playbill

American Theatre Wing’s Working in the Theatre series, The Design Panel, 1993 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9sp-aMQHf-U&t=2167s&ab_channel=AmericanTheatreWing

Journal of the History of Ideas Blog, Mai-mai Sze and Irene Sharaff in Public and in Private, Erin McGuirl, 2016 – https://jhiblog.org/2016/05/16/mai-mai-sze-and-irene-sharaff-in-public-and-in-private/

Irene Sharaff’s obituary, The New York Times, Marvine Howe, 1993 – https://www.nytimes.com/1993/08/17/obituaries/irene-sharaff-designer-83-dies-costumes-won-tony-and-oscars.html

Obituary: Irene Sharaff, The Independent, David Shipman, 2011 – https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-irene-sharaff-1463219.html

Broadway Design Exchange – Florence Klotz – https://www.broadwaydesignexchange.com/collections/florence-klotz

Obituary: Florence Klotz, The New York Times, 2006 – https://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/03/obituaries/03klotz.html

#bernadette peters#sunday in the park with george#costume design#costume designers#stephen sondheim#sondheim#broadway#theatre#tony awards#oscars#academy award nominations#ethel merman#judy garland#into the woods#theater#musical theater#fashion#dresses#meryl streep#elizabeth taylor#old hollywood#film#costumes#movies#musicals#writing#long reads#hollywood#actresses

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

Мастер-пост Alice in Wonderland

Я делал в 2018 году марафон по экранизациям “Алисы в Стране Чудес”. Теперь вот решил собрать все в один пост, хотя по тегу, конечно, все тоже прекрасно ищется. Но что поделать - я люблю списки! ^_^

Кстати, я нашел еще пару экранизаций и, как будет время, тоже внесу их в список (вместе с обзорами, конечно).

1903 - Alice in Wonderland (короткометражный фильм)

1910 - Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (короткометражный фильм)

1915 - Alice in Wonderland (фильм)

1931 - Alice in Wonderland (фильм)

1933 - Alice in Wonderland (фильм)

1949 - Alice in Wonderland (фильм)

1951 - Alice in Wonderland (мультфильм)

1954 - Alice in Wonderland (телеспектакль)

1966 - Alice in Wonderland (фильм)

1966 - Alice Through the Looking Glass (телеспектакль)

1966 - Alice in Wonderland, or What’s a Nice Kid Like You Doing in a Place Like This? (мультфильм)

1972 - Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (фильм)

1973 - Alice in Wonderland (короткометражный мультфильм)

1981 - 1982 - Алиса в Стране Чудес. Алиса в Зазеркалье (мультсериалы)

1985 - Alice in Wonderland. Part 1 (фильм)

1985 - Alice in Wonderland. Part 2 (фильм)

1986 - Alice Through the Looking Glass (мультфильм)

1988 - Alice in Wonderland (мультфильм)

1988 - Něco z Alenky (фильм)

1995 - Alice in Wonderland (мультфильм)

1998 - Alice Through the Looking Glass (фильм)

1999 - Alice in Wonderland (фильм)

2007 - Alice in Wonderland (мультфильм)

2008 - Abby in Wonderland (спецвыпуск Sesame Street)

2009 - Alice in Wonderland (мультфильм)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fool

— Tout Les Jours (Every Day), by René Magritte (1966).

-

Day after day

Alone on a hill

The man with the foolish grin

Is keeping perfectly still

But nobody wants to know him

They can see that he's just a fool

And he never gives an answer

But the fool on the hill

Sees the sun going down

And the eyes in his head

See the world spinning round

Well on the way

Head in a cloud

The man of a thousand voices

Talking perfectly loud

But nobody ever hears him

Or the sound he appears to make

And he never seems to notice

But the fool on the hill

Sees the sun going down

And the eyes in his head

See the world spinning round

And nobody seems to like him

They can tell what he wants to do

And he never shows his feelings

But the fool on the hill

Sees the sun going down

And the eyes in his head

See the world spinning round, oh oh oh, round round round round

He never listens to them

He knows that they're the fools

They don't like him

The fool on the hill

Sees the sun going down

And the eyes in his head

See the world spinning round

Oh, round round round round, oh

-

‘I see somebody now!’ [Alice] exclaimed at last. ‘But he’s coming very slowly—and what curious attitudes he goes into!’ (For the messenger kept skipping up and down, and wriggling like an eel, as he came along, with his great hands spread out like fans on each side.)

‘Not at all,’ said the King. ‘He’s an Anglo-Saxon Messenger—and those are Anglo-Saxon attitudes. He only does them when he’s happy. His name is Haigha.’ (He pronounced it so as to rhyme with ‘mayor.’)

‘I love my love with an H,’ Alice couldn’t help beginning, ‘because he is Happy. I hate him with an H, because he is Hideous. I fed him with—with—with Ham-sandwiches and Hay. His name is Haigha, and he lives—’

‘He lives on the Hill,’ the King remarked simply, without the least idea that he was joining in the game, while Alice was still hesitating for the name of a town beginning with H. ‘The other Messenger’s called Hatta. I must have two, you know—to come and go. One to come, and one to go.’

— in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871).

-

Paul then went back to his guitar and started to sing and play a very slow, beautiful song about a foolish man sitting on the hill. John listened to it quietly, staring blankly out of the window, almost as if he wasn’t listening. Paul sang it many times, la-la-ing words he hadn’t thought of yet. When at last he finished, John said he’d better write the words down or he’d forget them. Paul said it was OK. He wouldn’t forget them. It was the first time Paul had played it for John. There was no discussion.

— in Hunter Davies’ The Beatles: The Authorised Biography (1968).

-

JOHN: Who’s the fool on the hill, Paul?

PAUL: John.

-

Thank You Girl (1963): I know, little girl, only a fool would doubt our love

Another Girl (1965): You're making me say that I've got nobody but you / But as from today, well I've got somebody that's new / I ain't no fool and I don't take what I don't want / For I have got another girl, another girl

Girl (1965): She's the kind of girl who puts you down when friends are there / You feel a fool

The Fool On The Hill (1967): And nobody seems to like him / They can tell what he wants to do / And he never shows his feelings

Sexy Sadie (1968): Sexy Sadie, what have you done? / You made a fool of everyone

Hey Jude (1968): And anytime you feel the pain, hey Jude, refrain / Don't carry the world upon your shoulders / For well you know that it's a fool who plays it cool / By making his world a little colder

Glass Onion (1968): I told you 'bout the fool on the hill / I tell you man he living there still

Maxwell’s Silver Hammer (1968): Back in school again Maxwell plays the fool again / Teacher gets annoyed

Come And Get It (1969): If you want it, here it is, come and get it / Make your mind up fast / If you want it, anytime, I can give it / But you better hurry 'cause it may not last | Did I hear you say / That there must be a catch? / Will you walk away / From a fool and his money?

Dear Friend (1970): Dear friend, throw the wine / I'm in love with a friend of mine / Really truly, young and newly wed / Are you a fool, or is it true?

Some People Never Know (1971): No one else will ever see how much faith you have in me / Only fools would disagree that it's so / Some people never know | Like a fool I'm far away / Every night I hope and pray / I'll be coming home to stay and it's so / Some people never know [...] Only love can stand the test / Only you outshine the rest / Only fools take second best, and it's so / Some people never know

Sally G (1974): Somewhere to the south of New York City / Lies the friendly state of Tennessee / Down in Nashville town then I met a pretty / Who made a pretty big fool out of me

Memories (1979): Wondering, wondering / Is that really me / Running ’round in circles like a fool? / Off in such insanity / It’s a wonder how I survived / Ah, angels have been good to me / And I’m glad to be alive

The Other Me (1982): The other me would rather be the glad one / The other me would rather play the fool / I want to be the kind of me / That doesn't let you down as a rule

Your School (1984): Never thought I’d learn so much / Just a poor fool in love / Your school / I never felt the gentle touch until I met you

-

[Note: This term is very common in the vocabulary of the 50′s songs they grew up with. It’s not as specific to them as other motifs. Still, I was keen to track when and how they used it; with what meaning. Suggestions of additions, as always, are welcome.]

#who is the fool on the hill?#The Fool On The Hill#Thank You Girl#Another Girl#Girl#Sexy Sadie#Hey Jude#glass onion#maxwell silver hammer#Come And Get It#dear friend#some people never know#Sally G#Memories#the other me#Your School#The Epistolary#my stuff#René Magritte#Lewis Carroll

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Todos os filmes em que as cenas de sexo foram para valer

A Bula reuniu em uma lista todos os filmes da história do cinema nos quais os atores se envolvem em atos sexuais reais, não simulados. A diferença entre esses longas e a pornografia é que, embora possam ser considerados eróticos, a trama deles não é meramente pornográfica. Ao todo, a lista conta com 264 títulos.

A Bula reuniu em uma lista todos os filmes da história do cinema nos quais os atores se envolvem em atos sexuais reais, não simulados. Nos Estados Unidos, esse tipo de cena era proibido no cinema convencional, mas a partir dos Anos 1960 os cineastas começaram a ultrapassar os limites. A diferença entre esses longas e a pornografia é que, embora possam ser considerados eróticos, a trama deles não é meramente pornográfica. A maioria deles foi lançada nos anos 1970 e 80, com predominância de dois diretores: o espanhol Jesús Franco e o italiano Joe D’Amato. Por repetidas vezes, também aparecem os nomes de cineastas consagrados atualmente, como Lars von Trier, Gaspar Noé e Yorgos Lanthimos.

1 — Gift (1966), Knud Leif Thomsen

2 — They Call Us Misfits (1968), Stefan Jarl

3 — F*uck (1969), Andy Warhol

4 — 99 Mulheres (1969), Stefen Thrower

5 — Double Face (1969), Riccardo Freda

6 — Quiet Days in Clichy (1970), Jens Jørgen Thorsen

7 — Groupie Girl (1970), Drek Ford

8 — The Deviates (1970), Eduardo Cemano

9 — Bacchanale (1970), John Amero

10 — Kama Sutra ’71 (1970), Raj Devi

11 — Cry Uncle! (1971), John G. Avildsen

12 — Slaughter Hotel (1971), Fernando Di Leo

13 — Uma Lagartixa num Corpo de Mulher (1971), Lucio Fulci

14 — Luminous Procuress (1971), Steven F. Arnold

15 — Secret Rites (1971), Drek Ford

16 —A Clockwork Blue (1972), Eric Jeffrey Haims

17 — Pink Flamingos (1972), John Waters

18 — Who Killed the Prosecutor and Why? (1972), Giuseppe Vari

19 — La Verità Secondo Satana (1972), Ronato Polselli

20 — So Sweet, So Dead (1972), Rose et Val

21 — The Red Headed Corpse (1972), Renzo Russo

22 — Commuter Husbands (1972), Derek Ford

23 — Delirium (1972), Renato Polselli

24 — Christina, the Devil Nun (1972), Sergio Bergonzelli

25 — Danish Pastries (1973), Finn Karlsson

26 — Ingrid the Streetwalker (1973), Brunello Rondi

27 — Thriller – Um Filme Cruel (1973), Bo Arne Vibenius

28 — Revelations of a Psychiatrist on the World of Sexual Perversion (1973), Renato Polselli

29 — A Scream in the Streets (1973), Carl Monson

30 — The Devil In Miss Jones (1973), Gerard Damiano

31 — Fleshpot on 42nd Street (1973), Andy Milligan

32 — The Other Side of the Mirror (1973), Jess Franco

33 — Diary of a Nynphomaniac (1973), Jesús Franco

34 — A Virgem e os Mortos (1973), Jesús Franco

35 — O Reduto dos Monstros (1973), Vidal Raski

36 — The Devil’s Plaything (1973), Joseph W. Sarno

37 — Anita (1973), Torgny Wickman

38 — The Sex Thief (1973), Martin Campbell

39 — The Porn Brokers (1973), John Lindsay

40 — Emmanuelle (1974), Just Jaeckin

41 — The Eerie Midnight Horror Show (1974), Mario Gariazzo

42 — Zelda (1974), Alberto Cavallone

43 — I Tyrens Tegn (1974), Werner Hedman

44 — Score (1974), Radley Metzger

45 — Riot on a Women’s Prison (1974), Brunello Rondi

46 — The Girls of Kamare (1974), René Viénet

47 — La Bonzesse (1974), François Jouffa

48 — Sweet Movie (1974), Dušan Makavejev

49 — Fiossie (1974), Marie Forsa

50 — Contos Imorais (1974), Walerian Borowczyk

51 — Lorna: O Exorcista (1974), Jesús Franco

52 — Countess Perverse (1974), Jesús Franco

53 — Carnal Revenge (1974), Alfredo Rizzo

54 — Keep It Up, Jack! (1974), Derek Ford

55 — The Hot Girls (1974), John Lindsay

56 — Voodoo Sexy (1974), Osvaldo Civirani

57 — Nude for Satan (1974), Luigi Batzella

58 — In the Sign of the Gemini (1974), Werner Hadman

59 — Come To My Bedside (1975), John Hillbard

60 — The Image (1975), Radley Metzger

61 — Número Dois (1975), Jean-Luc Godard

62 — The Teenage Prostitution Racket (1975), Carlo Lizzani

63 — Emanuelle Nera (1975), Bitto Albertini

64 — Emanuelle’s Revenge (1975), Joe D’Amato

65 — Felicia (1975), Max Pécas

66 — But Who Raped Linda? (1975), Jesús Franco

67 — A Maldição da Vampira (1975), Jesús Franco

68 — Les Chatouilleuses (1975), Jesús Franco

69 — L’Éventreur de Notre-Dame (1975), Jesús Franco

70 — Justine e Juliette (1975), Mac Ahlberg

71 — The Bloodsucker Leads the Dance (1975), Alfredo Rizzo

72 — Lábios de Sangue (1975), Jean Rollin

73 — Rêves Pornos (1975), Max Pécas

74 — Wham! Bam! Thank You, Spaceman! (1975), William A. Levey

75 — Breaking Point (1975), Bo Arne Vibenius

76 — Rolls-Royce Baby (1975), Erwin C. Dietrich

77 — Girls Come First (1975), Joseph McGrath

78 — The Sexplorer (1975), Derek Ford

79 — Le Sexe qui Parle (1975), Claude Mulot

80 — Barbie Wire Dolls (1975), Jesús Franco

81 — Emanuelle em Bangkok (1975), Joe D’Amato

82 — Lust (1976), Max Pécas

83 — The Opening of Misty Beethoven (1976), Radley Metzger

84 — Alice in Wonderland: An X-Rated Musical Fantasy (1976), Bud Townsend

85 — Bedside Sailors (1976), John Hillbard

86 — In The Sign of the Lion (1976), Werner Hedman

87 — O Império dos Sentidos (1976), Nagisa Oshima

88 —Through the Looking Glasses (1976), Jonas Middleton

89 — A Real Young Girl (1976), Catherine Breillat

90 — Die Marquise von Sade (1976), Jesús Franco

91 — Girls in the Night Traffic (1976), Jesús Franco

92 — The French Governess (1976), Demofilo Fidani

93 — Inhibition (1976), Paolo Poetti

94 — Around the World in 80 Beds (1976), Jesús Franco

95 — Sex Express (1976), Derek Ford

96 — Keep It Up Downstairs (1976), Robert Young

97 — Secrets of a Superstud (1976), Morton L Lewis

98 — The Office Party (1976), David Grant

99 — The Angel and The Woman (1976), Gilles Carle

100 — Agent 69 in the Sign of Scorpio (1977), Werner Hedman

101 — Shining Sex (1977), Werner Hedman

102 — Fate la nanna coscine di pollo (1977), Amasi Damiani

103 — Blue Rita (1977), Jesús Franco

104 — Emanuelle na América (1977), Joe D’Amato

105 — Emanuelle Around the World (1977), Joe D’Amato

106 — Sister Emanuelle (1977), Giuseppe Vari

107 — Nazi Love Camp 27 (1977), Mario Caiano

108 — Under The Bed (1977), David Grant

109 — The Mark (1977), Ilias Mylonakos

110 — The Cerimony (1977), Omiros Efstratiadis

111 — Monsieur Sade (1977), Jacques Robin

112 — Caligula’s Hot Nights (1977), Roberto Bianchi

113 — Agent 69 Jensen in the Sign of Sagittarius (1978), Werner Hedman

114 — Behind Convent Walls (1978), Walerian Borowczyk

115 — Blue Movie (1978), Alberto Cavallone

116 — Sister of Ursula (1978), Enzo Milloni

117 — The Coming of Sin (1978), José Ramón Larraz

118 — Pleasure Shop on the Avenue (1978), Joe D’Amato

119 — You’re Driving Me Crazy (1978), David Grant

120 — Immoral Women (1979), Walerian Borowczyk

121 — Caligula (1979), Bob Guccione

122 — Images In a Convent (1979), Joe D’Amato

123 — Play Model (1979), Mario Gariazzo

124 — Giallo a Venezia (1979), Mario Landi

125 — Malabimba (1979), Andrea Bianchi

126 — A Prisão (1980), Oswaldo de Oliveira

127 — Beast in Space (1980), Alfonso Brescia

128 — Blow Job (1980), Alberto Cavallone

129 — La Gemella Erotica (1980), Alberto Cavallone

130 — Erotic Nights of the Living Dead (1980), Joe D’Amato

131 — Orgasmo Nero (1980), Joe D’Amato

132 — Flying Sex (1980), Joe D’Amato

133 — Libidomania (1980), Bruno Mattei

134 — When love is obscenity (1980), Roberto Polselli

135 — Hard Sensation (1980), Joe D’Amato

136 — Hotel Paradise (1980), Edoardo Mulargia

137 — Sex and Black Magic (1980), Joe D’Amato

138 — Porno Esotic Love (1980), Joe D’Amato

139 — The Porno Killers (1980), Roberto Mauri

140 — Sem Controle (1980), Paul Verhoeven

141 — Táxi para o Banheiro (1980), Frank Ripploh

142 — Os Frutos da Paixão (1981), Shuji Terayama

143 — Emmanuelle in Soho (1981), David Hughes

144 — Porno Holocaust (1981), Joe D’Amato

145 — Calígula: A História que Não Foi Contada (1982), Joe D’Amato

146 — Scandale (1982), George Mihalka

147 — Apocalipsis Sexual (1982), Carlos Aured

148 — Aphrodite (1982), Robert Fuest

149 — Il Nano Erotico (1982), Alberto Cavallone

150 — My Nights With Messalina (1982), Jaime J. Puig

151 — The Virgin for Caligula (1982), Jaime J. Puig

152 — Luz del Fuego (1982), David Neves

153 — Perdida em Sodoma (1982), Nilton Nascimento

154 — Killing of the Flesh (1983), Cesari Canevari

155 — Satan’s Baby Doll (1983), Mario Bianchi

156 — Taking Tiger Mountain (1983), Tom Huckabee

157 — Emmanuelle 4 (1984), Francis Leroi

158 — Lilian, The Perverted Virgin (1984), Jesús Franco

159 — Alcova (1985), Joe D’Amato

160 — James Joyce’s Women (1985), Michael Pearce

161 — Diabo no Corpo (1986), Marco Bellocchio

162 — Emmanuelle 5 (1987), Walerian Borowczyk

163 — Emmanuelle 6 (1988), Bruno Zincone

164 — Hotel St. Pauli (1988), Svend Wan

165 — Kindergarten (1989), Jorge Polaco

166 — Kinski Paganini (1989), Klaus Kinski

167 — Tokyo Decadence (1992), Ryu Murakami

168 — The Soft Kill (1994), Eli Cohen

169 — A Vida de Jesus (1997), Bruno Dumont

170 — Os Idiotas (1998), Lars von Trier

171 — O Tédio (1998), Cédric Kahn

172 — Fiona (1998), Amos Kollek

173 — Jesus is a Palestinian (1999), Lodewijk Crijns

174 — Romance (1999), Catherine Breillat

175 — Pola X (1999), Leos Carax

176 — The Man-Eater (1999), Aurelio Grimaldi

177 — Olhe por Mim (1999), Davide Ferrario

178 — Vampire Strangler (1999), William Hellfire

179 — Baise-moi (2000), Virginie Despentes

180 — Scrapbook (2000), Eric Stanze

181 — Intimacy (2001), Patrice Chéreau

182 — O Pornógrafo (2001), Bertrand Bonello

183 — Lucia e o Sexo (2001), Julio Medem

184 — Dias de Cão (2001), Ulrich Seidl

185 — O Centro do Mundo (2001), Wayne Wang

186 — La Novia de Lázaro (2002), Fernando Merinero

187 — Le loup de la côte Ouest (2002), Hugo Santiago

188 — Eternamente Sua (2002), Apichatpong Weerasethakul

189 — Coisas Secretas (2002), Jean-Claude Brisseau

190 — Ken Park (2002), Larry Clark

191 — Brown Bunny (2003), Vincent Gallo

192 — Faça Isto (2003), Tinto Brass

193 — Rossa Venezia (2003), Andreas Bethmann

194 — The Principles of Lust (2003), Penny Woolcock

195 — Anatomia do Inferno (2004), Catherine Breillat

196 — 9 Canções (2004), Michael Winterbottom

197 — Story of The Eye (2004), Georges Bataille

198 — Kärlekens språk (2004), Anders Lennberg

199 — Garotinho Bobo (2004), Lionel Baier

200 — All About Anna (2005), Jessica Nilsson

201 — 8mm 2 (2005), J. S. Cardone

202 — Beijando na Boca (2005), Joe Swanberg

203 — O Sabor da Melancia (2005), Tsai Ming-Liang

204 — Princesas (2005), Fernando Léon de Aranoa

205 — Deite Comigo (2005), Clement Virgo

206 — Destricted (2006), Gaspar Noé e outros

207 — Shortbus (2006), John Cameron Mitchell

208 — Taxidermia (2006), Gyorgy Pálfi

209 — Os Anjos Exterminadores (2006), Jean-Claude Brisseau

210 — Amour Fou (2007), Felicitas Korn

211 — Ex Drummer (2007), Koen Mortier

212 — Its Fine. Everything is Fine! (2007), David Brothers

213 — The Story of Richard O (2007), Damien Odoul

214 — Import Export (2007), Ulrich Seidl

215 — Serviço (2008), Brillante Mendoza

216 — Tropical Manila (2008), Sang-woo Lee

217 — Otto, ou Viva Gente Morta (2008), Bruce LaBruce

218 — À l’aventure (2008), Jean-Claude Brisseau

219 — Amateur Porn Star Killer 2 (2008), Shane Ryan

220 — Gutterballs (2008), Ryan Nicholson

221 — House of Flesh Mannequins (2009), Domiziano Cristopharo

222 — Anticristo (2009), Lars von Trier

223 — Viagem Alucinante (2009), Gaspar Noé

224 — The Band (2009), Anna Brownfield

225 — Canino (2009), Yorgos Lanthimos

226 — Angels With Dirty Wings (2009), Roland Reber

227 — Now & Later (2009), Philippe Diaz

228 — Bedways (2010), Rolf Peter Kahl

229 — Rio Sex Comedy (2010), Jonathan Nossiter

230 — The Bunny Game (2010), Adam Rehmeier

231 — Ano Bissexto (2010), Michael Rowe

232 — Gandu (2010), Qaushiq Mukherjee

233 — LelleBelle (2011), Mischa Kamp

234 — Desire (2011), Laurent Bouhnik

235 — O Amor é um Saco! (2011), Scud

236 — Caged (2011), Stephan Brenninkmeijer

237 — Léa (2011), Bruno Rolland

238 — The Wrong Ferrari (2011), Adam Green

239 — Clip (2011), Maja Milos

240 — Uma Estranha Amizade (2012), Sean S. Baker

241 — Paradise: Faith (2012), Ulrich Seidl

242 —And They Call It Summer (2012), Paolo Franchi

243 — I Want Your Love (2012), Travis Mathews

244 — Crônicas Sexuais de Uma Família Francesa (2012), Pascal Arnold

245 — Azul é a Cor Mais Quente (2013), Abdellatif Kechiche

246 — Ninfomaníaca (2013), Lars von Trier

247 — Pornopung (2013), Johan Kaos

248 — O Desconhecido do Lago (2013), Alain Guiraudie

249 — Zonas Úmidas (2013), David Wnendt

250 — Pasolini (2014), Abel Ferrara

251 — Diet of Sex (2014), Borja Brun

252 — Angry Painter (2015), Kyu-hwan Jeon

253 — Love (2015), Gaspar Noé

254 — Muito Amadas (2015), Nabil Ayouch

255 —Theo e Hugo (2016), Olivier Ducastel

256 — Tenemos la Carne (2016), Emiliano Rocha Minter

257 — Needle Boy (2016), Alexander Bak Sagmo

258 — Love Machine (2016), Pavel Ruminov

259 — A Noite (2016), Edgardo Castro

260 — A Thought of Ecstasy (2017), Rolf Peter Kahl

261 — Ana, Meu Amor (2017), Calin Peter Netzer

262 — Picture of Beauty (2017), Maxim Ford

263 — Marfa Girl 2 (2018), Larry Clark

264 — Mektoub, My Love: Intermezzo (2018), Abdellatif Kechiche

Todos os filmes em que as cenas de sexo foram para valer Publicado primeiro em https://www.revistabula.com

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

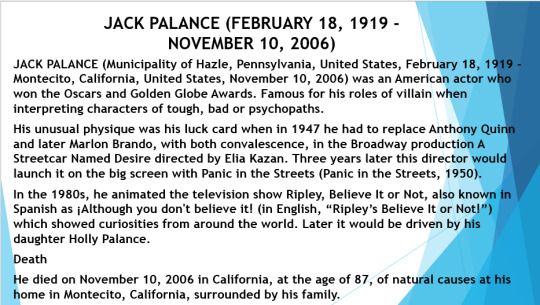

JACK PALANCE.

Filmography

1050 Panic in the streets

1951 Halls of Montezuma

1953 Deep roots or Shane, the unknown

1953 Man in the Attic

1953 Bonfire of Hates

1954 The Silver Chalice

1954 Sign of the Pagan

1955 I Died a Thousand Times

1956 Requiem for a Heavyweight

1956 Attack, by Robert Aldrich

1957 A lonely man

1959 Ten Seconds to Hell

1959 May Flower

1960 Revak, the rebel or Revenge of the rebel

1961 ll giudizio universale

1961 The Mongols

1961 Barabbas

1963 Le mépris

1966 Alice Through the Looking Glass

1966 The Professionals

1967 In the west you can make ... friend

1968 Wage to kill

1968 The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

1968 Zero Hour: Operation Rommel

1969 Che!

1969 The Marquis de Sade: Justine

1971 Pride of Race: The Horsemen

1972 Dracula (1972)

1972 Tedeum (1972)

1974 Craze - Demon Master

1976 Six bullets ... a revenge ... a prayer

1979 The World to Come

1980 without warning

1980 Hawk the Slayer

1982 Alone in the Dark

1987 Bagdad Café

1988 Young Gun

1989 Batman

1989 Tango and Cash

1991 Friends, always friends

1991 City Cowboys

1993 Cyborg 2

1994 That cop is a panoli

1994 City Slickers II: The Legend of Curly's Gold

2001 The return of Prancer.

Créditos: Tomado de Wikipedia

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Palance

#HONDURASQUEDATEENCASA

#ELCINELATELEYMICKYANDONIE

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

1966 'Alice through the looking glass'

Bob Mackies 1966 adaption of ‘Alice through the looking glass’ has very innovative costumes. They used experimental materials to create the famous character. Such as the chess pieces look similar to Michelin man with large rolls up the body. The films take on the Queens cards and courtiers mixing historical dress with fantasy and mostly made from felt. They use block colour and have the similar silhouette of 1830/40s day dresses. I think the costumes are used very effectively within the film to clearly distinguish each character.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

What Alice adaptations do you like best??

This post is going to be very long (I'm going to talk about 4 different adaptations)

(also this is a warning that if you're scared of the 1933 Alice in wonderland &/or creepy looking puppets, animal suits claymation or stop motion that I will have photos of those things in this post)

The 1972 Alice in wonderland has been my favorite for a while. It has my favorite Alice, and everything about the movie is just beautiful. The soundtrack isn't great and it can get a bit boring, but I'm very emotionally attached to this movie.

(also I love the frog footman in this movie)

Also, the 1949 Alice in wonderland is great. When I watched it I was really frustrated with how much time they spent on lewis Carroll's personal life 😭 but the rest of the movie is claymation & live action (with Alice being the only thing live action in it) and it's just so cool. Claymation I think is the coolest form of animation and I didn't even know this movie was claymation until I watched it

The 1933 Alice in wonderland is also one of my favorites, I think it's really great and I can't even explain why. I'm biased towards any Alice in wonderland adaptation with puppets in it. Sterling Holloway was also in this movie, he played the frog foot man, who's one of my favorite Alice in wonderland characters.

Another is the 1981 Alice in wonderland & through the looking glass, both about 30 minutes long because I believe they aired on tv. These were in a language I don't speak, but there's captioned & dubbed versions of it. It's my favorite animated adaptation, the art is extremely creative and the style is just beautiful. I like it a lot.

Lastly my favorite through the looking glass adaptation, the 1966 film. I can't even put it into words, I never stopped thinking about it since I had watched it. It's such a creative story and the sets are amazing and the songs are great and it's funny and it's interesting and it's just a really good movie. I don't know where these films get Alice's jester side kick from (please tell me if you do😭) but to be fair I've never even read ttlg. I do adore Lester tho, his song was my favorite, it's always in my head. The jabberwocky was a creative character as well, I didn't like his voice tho. But I liked his character. The plot kind of didn't make any sense but that doesn't really matter at least to me

I am this movie's biggest fan

Also I saw this question last night but I had to keep myself from staying up and writing this

#alice in wonderland 1933#alice in wonderland#alices adventures in wonderland#alice in wonderland 1981#Alice in wonderland 1972#Alice through the looking glass#alice through the looking glass 1966#aspiring clown#clownblr

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Agnes Moorehead as The Red Queen in Alice Through The Looking Glass (1966)

#agnes moorehead#judi rolin#roy castle#robert coote#nanette fabray#ricardo montalban#alice through the looking glass#red queen#off with his head#off with their heads#myedit#mygif#stgedit

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

First lines from the books I read in 2018

Hawksmoor by Peter Ackroyd: Thus is 1711, the ninth year of the reign of Queen Anne, an Act of Parliament was passed to erect seven new Parish Churches in the Cities of London and Westminster, which commission was delivered to Her Majesty’s Office of Works in Scotland Yard.

Métamorphose en bord de ciel by Mathias Malzieu: Les oiseaux, ça s'enterre en plein ciel.

Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen: The family of Dashwood had been long settled in Sussex.

Le plus petit baiser jamais recensé by Mathias Malzieu: Le plus petit baiser jamais recensé.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll: Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, “and what is the use of a book,” thought Alice, “without pictures or conversations?”

Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There by Lewis Carroll: One thing was certain, that the white kitten had had nothing to do with it -it was the black kitten’s fault entirely.

Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson: Ba-room, ba-room, ba-room, baripity, baripity, baripity, baripity-Good.

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin: Dear James: I had begun this letter five times and torn it up five times.

The Secret in Their Eyes by Eduardo Sacheri: Benjamín Miguel Chaparro stops short and decides he’s not going.

At the Mountains of Madness by H. P. Lovecraft: I am forced into speech because men of science have refused to follow my advice without knowing why.

The Minds of Billy Milligan by Daniel Keyes: This books is the factual account of the life, up to now, of William Stanley Milligan, the first person in U.S. history to be found not guilty of major crimes, by reason of unsanity, because he possessed multiple personalities.

The Bad Beginning by Lemony Snicket: If you are interested in stories in happy endings, you would be better off reading some other book.

Puckoon by Spike Milligan: Several and a half metric miles North East of Sligo, split by a cascading stream, her body on earth, her feet in water, dwells the microcephalic community of Puckoon.

Piercing by Ryu Murakami: A small living creature asleep in its crib.

The Reptile Room by Lemony Snicket: The stretch of the road that leads out of this city, past Hazy Harbor and into the town of Tedia, is perhaps the most unpleasant in the world.

And the Mountains Echoed by Khaled Hosseini: So, then.

The Shape of Water by Guillermo Del Toro and Daniel Kraus: Richard Strickland reads the brief from General Hoyt.

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell: He’d stopped trying to bring her back.

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell: The Rue du Coq d’Or, Paris, seven in the morning.

We Were Liars by E. Lockhart: Welcome to the beautiful Sinclair family.

The Book Thief by Markus Zusack: First the colors. Then the humans. That’s usually how I see things. Or at least, how I try.

The Wide Window by Lemony Snicket: If you didn’t know much about the Baudelaire orphans, and you saw them sitting on their suitcases at Damocles Dock, you might think they were bound for an exciting adventure.

The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson: No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream.

Battles in the Desert by José Emilio Pacheco: I remember, I don’t remember.

The Miserable Mill by Lemony Snicket: Sometime during your lifetime -in fact, very soon- you may find yourself reading a book, and you may notice that a book’s first sentence can often tell you what sort of story your book contains.

The Age of American Unreason by Susan Jacoby: The word is everywhere, a plague spread by the President of the United States, television anchors, radio talk show hosts, preachers in megachurches, self-help gurus, and anyone else attempting to demostrate his or her identification with ordinary, presumably wholesome American values.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare: Theseus, duke of Athens, is planning the festivities for his upcoming wedding to the newly captured Amazon, Hippolyta.

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert: We were in study hall when the headmaster walked in, followed by a new boy not wearing a school uniform, and by a janitor carrying a large desk.

The Austere Academy by Lemony Snicket: If you were going to give a gold medal to the last delightful person on Earth, you would have to give that medal to a person named Carmelita Spats, and if you didn’t give it to her, Carmelita Spats was the sort of person who would snatch it from your hands anyway.

Lord of the Flies by William Golding: The boy with fair hair lowered himself down the last few feet of rock and began to pick his way toward the lagoon.

The Taming of the Shrew by William Shakespeare: Christopher Sly, a drunken beggar, is driven out of an alehouse by its hostess.

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee: When he was nearly thirteen, my brother Jem got his arm badly broken at the elbow.

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro: My name is Katy H.

Hear the Wind Sing by Haruki Murakami: “There’s no such thing as a perfect piece of writing.”

The Ersatz Elevator by Lemony Snicket: The book you are holding in your two hands right now -assuming that you are, in fact, holding this book, and that you have only two hands- is one of two books in the world that will show you the difference between the words “nervous” and the word “anxious.”

Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare: Two households, both alike in dignity, (In fair Verona, where we lay our scene), From ancient grudge break to new mutiny, Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

Adventure Time: The Enchiridion & Marcy’s Super Secret Scrapbook!!!: My Devoted Evil Daighter, Marceline, I admit we’ve had a somewhat volatile father-daughter relantionship ever since the regrettable Fry Incident.

A Game of Thrones by George R. R. Martin: Ser Waymar Royce glanced at the sky with desinterest.

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley: You will rejoice to hear that no disaster has accompanied the commencement of an enterprise which you have regarded with such evil forebodings.

Pinball, 1973 by Haruki Murakami: I used to love listening to stories about faraway places.

The Vile Village by Lemony Snicket: No matter who you are, no matter where you live, and no matter how many people are chasing you, what you don’t read is often as important as what you do read.

Dracula by Bram Stoker: 3 May. Bistritz. –Left Munich at 8:35 P.M., on 1st May, arriving at Vienna early next morning; should have arrived at 6:43, but train was an hour late.

The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare: I know this hartred mocks all Christian virtue, but They I loathe: their very sight abhors me.

On the Road by Jack Kerouac: I first met Dean not long after my wife and I split up.

A Wild Sheep Chase by Haruki Murakami: It was a short one-paragraph item in the morning edition.

The Hostile Hospital by Lemony Snicket: There are two reasons why a writer would end a sentence with the word “stop” written in entirely in capital letters STOP.

The Most Beautiful: My Life with Prince by Mayte Garcia: The chain-link fence around Praisley Park is woven with purple ribbons and roses, love notes, tributes, and prayers for peace.

Hamlet by William Shakespeare: Who’s there?

A Clash of Kings by George R. R. Martin: The comet’s tail spread across the dawn, a red slash that bled above the crags of Dragonstone like a wound in the pink and purple sky.

Out of Africa by Isak Dinensen: I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of Ngong Hills.

Carrie by Stephen King: News item from the Westover (Me.) weekly enterprise, August 19, 1966: RAIN OF STONES REPORTED.

The Carnivorous Carnival by Lemony Snicket: When my workday is over, and I have closed my notebook, hidden my pen and sawed holes in my rented canoe so it cannot be found, I often like to spend the evening in conversation with my few surviving friends.

Forgive Me, Leonard Peacock by Matthew Quick: The P-38 WWII Nazi handgun looks comical lying on the breakfast table next to a boal of outmeal.

The Turn of the Screw by Henry James: The story had held us, round the fire, sufficiently breathless, but except the obvious remark that it was gruesome, as, on Christmas Eve on an old house, a strange tale should essentially be, I remember no comment uttered till somebody happened to say that it was the only tale he had met in which such a visitation had fallen on a child.

Carmilla by Sheridan J. Le Fanu: Upon a paper attached to the Narrative which follows, Doctor Hesselius has written a rather elaborated note, which he accompanies with a reference to his Essay on the strange subject which the MS. illuminates.

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson: No one has ever suffered as I have.

The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka: One morning, when Gregor Samsa woke from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a horrible vermin.

House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski: I still get nightmares.

Othello by William Shakespeare: In the streets of Venice, Iago tells Roderigo of his hatred for Othello, who has given Cassio the lieutenancy that Iago wanted and has made Iago a mere ensign.

Dance, Dance, Dance by Haruki Murakami: I often dream about the Dolphin Hotel.

The Slippery Slope by Lemony Snicket: A man of my acquaintance once wrote a poem called “The Road Less Traveled,” describing a journey he took through the woods along a path most travelers never used.

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou: “What you looking at me for? I didn’t come to stay…”

A Most Haunted House by G. L. Davies: The house first came to my attention a few years ago.

Ghost Sex, The Violation by G. L. Davies: I met with Lisa at her home in Pembroke Dock.

Any Man by Amber Tamblyn: Am I in a body?

A Head Full of Ghosts by Paul Tremblay: “This must be so difficult for you, Meredith.”

A Storm of Swords by George R. R. Martin: The day was grey and bitter cold, and the dogs would not take the scent.

Macbeth by William Shakespeare: When shall we three meet again in thunder, lightning, or in rain?

You by Caroline Kepnes: You walk into the bookstore and you keep your hand on the door to make sure it doesn’t slam.

The Grim Grotto by Lemony Snicket: After a great deal of examining oceans, investigating rainstorms and staring very hard at several drinking fountains, the scientists of the worlds developed a theory regarding how water is distributed around our planet, which they have named “the water cycle.”

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys: They say when trouble comes close ranks, and so the white people did.

Mansfield Park by Jane Austen: About thirthy years ago, Miss Maria Ward, of Huntingdon, with only seven thousand pounds, had the luck to captivate Sir Thomas Bertram, of Mansfield Park, in the country of Northampton, and to be thereby raised to the rank of a baronet’s lady, with all the comforts and consequences of a handsome house and a large income.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë: My name is Gilbert Markham, and my story begings in October 1827, when I was twenty-four years old.

The Tempest by William Shakespeare: Boatswain!

Lucky by Alice Sebold: In the tunnel where I was raped, a tunnel that was once an underground entry to an amphitheather, a place where actors burst forth from underneath the seats of a crowd, a girl had been murdered and dismembered.

The Penultimate Peril by Lemony Snicket: Certain people had said that the world is like a calm pond, and that anytime a person does even the smallest thing, it is as if a stone has dropped into the pond, spreading circles of ripples further and further out, until the entire world has been changed by one tiny action.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alice reaction gifs from 1966 Alice Through the Looking Glass, 1970

Les aventures d'Alice au pays des merveilles (this is the actual translation of this line; thanks to @ravenwitch), 1974 Nel Mondo di Alice, and 1976 Alicia en el país de las maravillas. I had a hard time thinking of gif idea for these Alices so if you have any, please feel free to request. More Alice reaction gifs here.

P.S. click here if you need a explanation for the Mabel one.

#Alice in Wonderland#carrollian#Alice Through the Looking Glass#Judi Rolin#Milena Vukotic#1966 judi rolin#1970#Mónica Vont Reust#1974#Nel Mondo di Alice#1976#my gifs#reaction gifs

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Matrix 4 Trailer Song White Rabbit Has Cut Holes in Reality for Years

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J