#asia insect

Text

Citrus Longhorn Beetle - Anoplophora chinensis

We return to lovely Sunrise Peak in South Korea to have another look at this starry-night shelled specimen. From the initial batch sent to me, there were extra images leftover for another post, but 4 years is a long time for an update! Previously, I gushed over this find, so this post will examine more facts. The first thing I'd like to clarify is the size of this Longhorn Beetle as the images make it appear giant! The wooden beam it travels on isn't a massive rail. In actuality, specimens have been measured fall in the range of 20 - 40mm (2-4cm) long. Like their distant cousins, the red Milkweed Beetle, females tend to be larger than the males. That's just talking about body size; if antenna length was included, these insects became much longer, but in different ways. Female Citrus Longhorn antennae is just slightly longer than the length of the body, while males have antennae that are 1.5 times as long as their body (or longer)! Given the antennae length, it's likely that the individual in these pictures is a female Longhorn. In addition, the tip of the abdomen appears to be more rounded compared a male's narrowing abdomen, but I'm not relying on that as a whole since the wingcase position (having recently been opened) makes abdomen examination difficult. Secondly, all this talk about size only applies to the adults, as the larvae can get much longer, larger and heavier.

They're soft-bodied and lack some of the more sophisticated structures that the adults have, such as wings and long antennae, so they can afford it until pupation. Whichever tree specie the eggs are laid inside, the larvae begin to feed beneath the bark on the tree's pith and tissues near the base. Feeding there also allows access to tree's roots which the larvae may also feed on using gnawing mandibles. Since the larvae dwell in the bottom of the tree, feeding will eventually translate to the whole tree as nutrients are cut off and their innards become damaged and prone to arboreal diseases. What makes them so notorious as pests is that damage done tends to be invisible until the tree's health begins to deteriorate or the adult emerges from the tree, leaving behind an escape hole appears as if it was perfectly drilled from the inside. Since they can remain undetected without close inspection of trees and wood products, it's no wonder that human transport has accidentally introduced them to Europe and North America where efforts aim to contain or eradicate them. It's a shame that the larvae swarm and feed so voraciously since the adult Beetle is so ornate and eye-catching.

Furthermore, the adults only eat leaves and nibble at the outer parts of the tree. Though beautiful, we need to monitor for them and manage them carefully to prevent critical damage to trees and forest, similar to its close relative (recently eradicated in Ontario), the Asian Longhorn Beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis). We would be hard-pressed to naturalize them in a manner like the White Spruce Sawyer Beetle, especially since the latter feeds on dead wood, while the Citrus Longhorn feeds on fresh tree innards. It seems so easy at first given how similar the two species appear to each other, but it's often the details that are important with introduced species. To conclude on the subject of details, North American bug hunters should be extra observant not to confuse the White Spruce Sawyer for the Citrus Longhorn. Though both share dark-colored bodies, pronotum side-spikes and long antennae, the latter will always be more robust in shape, have a spotted wingcase and ringed antennae. If you can get close enough to the front of the wingcase, examine carefully for the presence of 2 small white tubercular structures (one on each wingcase) as these are distinctive to the Citrus Longhorn, and aren't found on the Asian Longhorn.

Pictures were taken on July 21, 2019 in South Korea with a Google Pixel. And with that, every successfully identified insect from the yearlong Asia trip has been posted! You've been amazing, my dearest Sarali! Thank you for sharing your amazing, life-changing voyage with me, and for all of these lovely creatures! Godspeed to all your future endeavors and dreams!

#jonny’s insect catalogue#asia insect#beetle#citrus longhorn beetle#longhorn beetle#insect#coleoptera#south korea#korea#july2019#2019#nature#entomology#invertebrates

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via " Chinese Moon Moth" Essential T-Shirt for Sale by Guess4best)

#findyourthing#redbubble#asian moon moth#insect#asia#asia insect#chinese moon moth#female chinese moon moth#tshirt#t-shirt design#caps#tote bag#pin

1 note

·

View note

Text

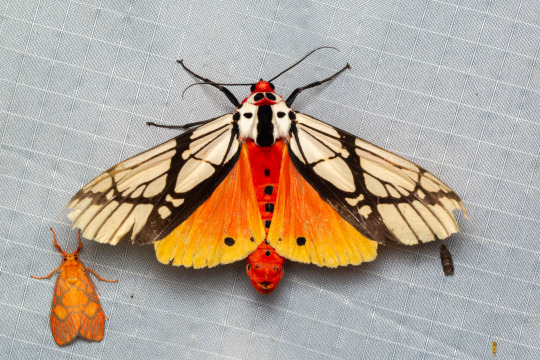

Tiger Moth (Areas galactina), family Erebidae, MCM Nature Discovery Villa, Fraser's Hill, Malaysia

photograph by David Fischer

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Cinnabar moth

A poisonous moth? Yes. The cinnabar moth (Tyria jacobaeae), found in Europe and Asia, has wings decorated with bright-red patches that scream, "Do not eat!"

(Image credit: Roger Tidman)

394 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Open Your Home to the Common House Centipede

A common sight in homes throughout Europe, Asia, the Americas, and Australia the common house centipede (Scutigera coleoptrata) is a medium-sized species of centipede originally from the Mediterranean. In the wild, they prefer grasslands and deciduous forests where they can hide under rocks, logs, or leaf litter. These insects have also adapted well to urban development, and are frequently found in basements, bathrooms, and garages, as well as gardens and compost piles.

Like other centipedes, the common house centipede has less than 100 legs; in fact, they only have 15 pairs, with the front pair used only for holding prey or fending off threats. All those legs let the common house centipede move up to 0.4 meters per second (1.3 ft/s) over a variety of surfaces, including walls and ceilings. The actual body of S. coleoptrata is only 25 to 35 mm (1.0 to 1.4 in) long, but the antennae are often as long as the body which can give this insect a much larger appearance. However, they can be hard to spot, especially in their natural environments; their tan and dark brown coloration allows them to blend in seamlessly to surrounding vegetation.

Though they pose little threat to humans, house centipedes are predatory. Their primary food source is other arthropods, including cockroaches, silverfish, bed bugs, ticks, ants, and insect larvae. S. coleoptrata is a nocturnal hunter, and uses its long antennae to track scents and tactile information. Their compound eyes, unusual for centipede species, can distinguish daylight and ultraviolet light but is generally used as a secondary sensory organ. When they do find prey, house centipedes inject a venom which can be lethal in smaller organisms, but is largely harmless to larger animals. This makes them important pest controllers. In the wild, house centipedes are the common prey of rodents, amphibians, birds, and other insects.

The mating season for S. coleoptrata begins in the spring, when males and females release pheromones that they can use to find each other. Once located, the male spins a silk pad in which he places his sperm for the female to collect. She then lays fertilized eggs in warm, moist soil in clutches of 60-150. These eggs incubate for about a month, and the young emerge with only four pairs of legs. Over the next three years, juvenile house centipedes molt 7 times, each time gaining new pairs of legs. After they grow their last pair of legs, immature house centipedes molt an additional 3 times, at which time they become sexually mature. If they can avoid predation, individuals can live up to 7 years in the wild.

Conservation status: The common house centipede has not been evaluated by the IUCN, as it is relatively common both in the wild and in urban areas. Although they have been introduced to areas outside their native range, no detrimental environmental effects have been associated with their spread.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Joseph Berger

David Paul

Conrad Altman via iNaturalist

#common house centipede#Scutigeromorpha#Scutigeridae#centipedes#myriapoda#myriapods#insects#arthropods#deciduous forests#deciduous forest arthropods#grasslands#grassland arthropods#urban fauna#urban arthropods#europe#north america#south america#asia#australia#oceania#animal facts#zoology#biology

621 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thousands of ducks are sent to eat insects in a rice paddy after harvest.

386 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Oriental Blue Clearwing Moth: these moths were regarded as a "lost species" for more than 130 years, until they were finally sighted again in 2013

For more than 130 years, the Oriental blue clearwing moth (Heterosphecia tawonoides) was known only from a single, badly damaged specimen that was collected in Sumatra in 1887. There were no recorded sightings of this species again until 2013, when entomologist Dr. Marta Skowron Volponi unexpectedly found the moths feeding on salt deposits that had accumulated along the riverbanks in Malaysia's lowland rainforest.

These moths were observed by researchers again in 2016 and 2017, and research indicates that the moths are actually bee-mimics, as they mimic the appearance, sound, behavior, and flight patterns of local bees. Their fuzzy, bright blue appearance might seem a little out of place for a bee-mimic, but those features do appear in several different bee species throughout Southeast Asia.

When the moths are in flight, they bear a particularly strong resemblance to the bees of the genus Thyreus (i.e. cuckoo bees, otherwise known as cloak-and-dagger bees), several of which are also bright blue, with banded markings, dark blue wings, fuzzy legs, and smooth, rounded antennae. The physical resemblance is compounded by the acoustic and behavioral mimicry that occurs when the moths are in flight.

Cloak-and-Dagger Bees: the image at the top shows an Indo-Malayan cloak-and-dagger bee (Thyreus novaehollandiae) in a sleeping position, holding itself upright with its mandibles clamped onto a twig, while the image at the bottom shows a Himalayan cloak-and-dagger bee (T. himalayensis) resting in the same position

The moths also engage in "mud-puddling" among the various bees that congregate along the riverbanks; mud-puddling is the process whereby an insect (usually a bee or a butterfly) draws nutrients from the fluids found in puddles, wet sand, decaying plant matter, carrion, animal waste, sweat, tears, and/or blood. According to researchers, the Oriental blue clearwing moth was the only lepidopteran that was seen mud-puddling among the local bees.

Dr. Skowron Volponi commented on the unusual appearance and behavior of these moths:

You think about moths and you envision a grey, hairy insect that is attracted to light. But this species is dramatically different—it is beautiful, shiny blue in sunlight and it comes out during the day; and it is a master of disguise, mimicking bees on multiple levels and even hanging out with them. The Oriental blue clearwing is just two centimeters in size, but there are so many fascinating things about them and so much more we hope to learn.

This species is still incredibly vulnerable, as it faces threats like deforestation, pollution, and climate change. The president of Global Wildlife Conservation, which is an organization that seeks to rediscover "lost species," added:

After learning about this incredible rediscovery, we hope that tourists visiting Taman Negara National Park and picnicking on the riverbanks—the home of these beautiful clearwing moths—will remember to tread lightly and to take their trash out of the park with them. We also recommend that Americans learn about palm oil production, which is one of the primary causes of deforestation in Malaysia.

Sources & More Info:

Phys.org: Bee-Mimicking Clearwing Moth Buzzes Back to Life After 130 Years

Mongabay News: Moth Rediscovered in Malaysia Mimics Appearance and Behavior of Bees to Escape Predators

Journal of Tropical Conservation Science: Lost Species of Bee-Mimicking Clearwing Moth, H. tawonoides, Rediscovered in Peninsular Malaysia's Primary Rainforest

Frontiers in Zoology: Southeast Asian Clearwing Moths Buzz like their Model Bees

Royal Society Publishing: Moving like a Model - mimicry of hymenopteran flight trajectories by clearwing moths of Southeast Asian rainforests

Medium: Rediscovery in a Glint of Blue

re:wild.org: The "Search for Lost Species" Project

#lepidoptera#moths#heterosphecia tawonoides#oriental blue clearwing moth#entomology#insects#cute bugs#nature#animals#lost species#mimicry#evolution#bees#southeast asia#Malaysia#colorful moths#bee mimic#science

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Insects and Grasses, Yamamoto Baiitsu, 1847

#art#art history#Asian art#Japan#Japanese art#East Asia#East Asian art#Yamamoto Baiitsu#genre painting#insects and grasses#scroll#handscroll#ink and color on silk#Edo period#19th century art#Metropolitan Museum of Art

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

By SREEJITH VISWANATHAN - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

#hammerhead worm#broadhead planarian#land planarian#planarian#worm#these are invasive in the u.s. canada and europe#but i'd still like it if we didn't go too wild with the “ahhh kill it” in the notes. it's not like i can stop you though#this guy's portrait was taken in asia where he's supposed to be 👍#for blacklist:#bug#insect

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Gaudy Baron (Euthalia lubentina), Tungareshwar National Park, Maharashtra, India

photograph by Sagar Sarang | Wikipedia CC

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grasshopper Robber Fly - Philodicus sp. (?)

While researching the identity of this insect, the genus Promachus kept popping up as a topic of interest. That genus is fairly popular due to the presence of giant species among Robber Flies. Some of the examples observed (found in Asia) were similar in appearance to this specimen, but not a perfect match. Furthermore, it's hard to judge the scale of this insect, so it may not be so large that it is considered a giant. This large, predaceous insect is likely very formidable if its size is any indication! As impressive as it is, to be perfectly honest I can't declare with certainly the branch within Asilidae (Robber Flies) that this hunter sits on. Looking into other genera for more clues, Philodicus was found and I've settled on it (for now). Compared to Promachus, there is a much closer similarity between the images here sent to me by SaraLi and other specimens observed in the wild and subsequently photographed (including a large collection on iNaturalist). I've kept my attention towards the wings and patterns along the back of the thorax and entirety of the abdomen.

On the assumption that is a Philodicus Fly, a part of its diet seems to be revealed by its common name: Grasshoppers! No easy feat to catch one since Grasshoppers tend to blend into their environment, only to explosively launch and fly away from danger. Recall as well how Robber Flies hunt: lie in wait, ready to ambush prey mid-flight, grapple them and finish them with their sharp proboscis. If this genus does hunt Orthopterans, it will need to rely heavily on its eyesight and any sensory hairs/spines lining its body in order to locate one! Hunting them may be an ultimate waiting game, but a successful catch should provide ample nutrition for a patient Assassin Fly. Perhaps it would have better luck catching a juvenile (wingless) Grasshopper on the descent to the ground for higher vegetation? Of course, if the collections of photographs I've seen are any indication, Philodicus Flies are content with catching small prey if there is need or the opportunity arises, including other smaller Flies.

Pictures were taken on July 8, 2019 in South Korea with a Google Pixel. If anyone can help me clarify the identity of this insect, please let me know. Until then, this insect will be tagged as 'unidentified'.

#jonny’s insect catalogue#insect#fly#grasshopper robber fly#philodicus sp#philodicus robber fly#robber fly#diptera#south korea#korea#asia insect#july2019#2019#nature#entomology#unidentified#invertebrates

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Attacus atlas

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Easter Egg" Weevil (Pachyrhynchus cf. erichsoni), family Curculionidae, Mindanao, Philippines

photographs by Bald Guy With a Camera

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Mormolyce phyllodes, commonly known as the violin beetle, is a species of ground beetles in the subfamily Lebiinae which is native to the tropical rainforests of Southeast Asia including the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Java, Malaysia, and Sumatra. These typically nocturnal insects spend much of there time living in cracks in the soil, leaf litter, and inside rotten logs or underneath tree bark. Here they primarily feed upon other insects particularly grubs and other larvae. Violen beetles are themselves preyed upon by several species of birds and bats. Because of this in addition to there camouflage they also secrete poisonous butyric acid which they use for defense purposes. Reaching around 2.4 to 3.9 inches (6.1 to 9.91cms) in length, these beetles possess an elongated head and pronotum, slender legs and large antennae. The body is flat and leaf-shaped, typically a shiny black or brown in color with a distinctive violin-shaped translucent elytra hence there common name: the violin beetle. There breeding habits are not well known but they tend to lay there eggs inside of large hard bracket fungi. Upon hatching the larvae spend the next nine months digging tunnels throughout the fungus feeding upon both the fungus and any invertebrates they come across. They then pupate and exit there fungi home. On average adult violin beetles live 3 to 5 months.

#pleistocene pride#pleistocene#pliestocene pride#pliestocene#cenozoic#ice age#stone age#bug#insect#beetle#violin#violin beetle#asia

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spare a Moment for the Asparagus Beetle

Crioceris asparagi, more often known as the common asparagus beetle, is a species native to Europe and Asia; is has also been introduced to North America. As the name implies, it is almost exclusively found on asparagus plants, making it a common sight in agricultural fields and grasslands with wild asparagus.

The common asparagus beetle is easy to spot, due to its distinctive markings. Both males and females are black, with a red thorax and a red ring around their wing casings (elytra). Each individual also has three large, white or cream spots on each of their elytra. But for all their flashy markings, C. asparagi are quite small, reaching only 7 mm (0.28 in) in length.

The bright markings of the asparagus beetle are thought to mimic those of another type of stinging beetle, as a way to deter predators. However, this defense is not very effective, as C. asparagi are a popular food for birds including ducks and chickens, as well as larger beetles and wasps. If its bright coloration fails to ward off threats, the beetle will flee to another plant or play dead. For its part, the asparagus beetle only feeds on one thing: asparagus.

Breeding for C. asparagi occurs in April or May and lasts throughout the spring. Males court females by riding on their abdomens and guarding them from other males; females in turn will often attempt to avoid male attention by moving away or kicking them. A female will often mate with several males, and only retains the sperm of the male she prefers. Following copulation, she lays 4-8 eggs on the underside of an asparagus leaf. The eggs can take anywhere from three to twelve days to hatch, and the larvae immediately begin feeding on their host plant. After several weeks, during which time the larvae go through for molting periods or instars, they pupate and emerge as adults. Several generations can occur in a single season. When the weather grows colder, the asparagus beetle burrows into the soil or leaf litter to hibernate through the winter. Most adults only live about a year or so.

Conservation status: The common asparagus beetle has a large, robust population and has not been evaluated by the IUCN. In both its native and introduced range, it is often considered a pest for asparagus farmers.

If you send me proof that you’ve made a donation to UNRWA or another organization benefiting Palestinians– including esim donations– I’ll make art of any animal of your choosing.

Photos

Tom Murray

David Gould

Phil Myers

#common asparagus beetle#Coleoptera#Chrysomelidae#leaf beetles#beetles#insects#arthropods#urban fauna#urban arthropods#grasslands#grassland arthropods#europe#asia#north america#animal facts#biology#zoology#ecology

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Macro Monday!

For all those who love the living natural beauty of our world as well as that which is preserved in rock, here is a gorgeous specimen of Creobroter gemmatus, the Jeweled Flower Mantis. A lovely species native to Asia.

7 notes

·

View notes