#longbow

Text

All girls dungeon squad! by HanPixe

#HanPixe#the party#greatsword#longbow#spear#shield#sword#chainmail#helmet#brigandine#hood#tankard#fighter#barbarian#ranger#cleric

292 notes

·

View notes

Text

TASTE THE RAINBOW 🌈

(Longbow LGB-7Q)

Still a W.I.P. along with Falconer in the back and Urbanmech not pictured. Hopefully this one will be leading my Alphastrike force.

I think the Pilot will be named "Skittles"

#battletech#mechwarrior#miniatures#tabletop miniatures#wargaming#mech#miniature painting#tabletopminiatures#miniature wargaming#longbow#lgb-7q#falconer#wip

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

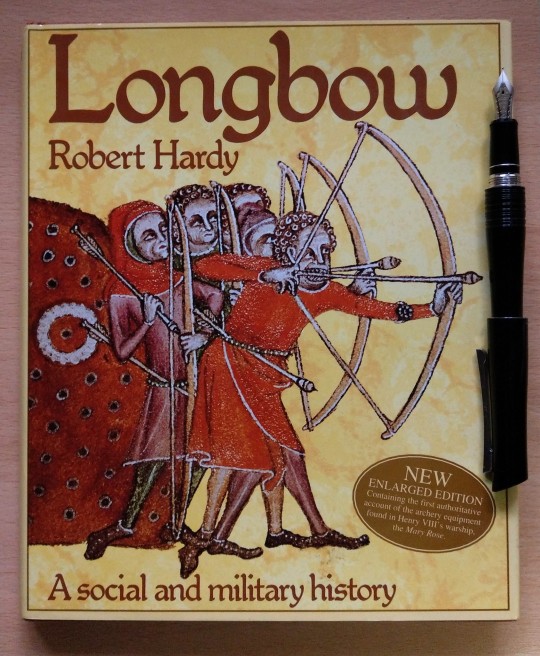

Anyone remember a documentary from long ago (1973) entitled "Chronicle - The Longbow" and presented by actor Robert Hardy?

It's not on YouTube, and I haven't seen it for years - but I do have the associated book...

...so this next bit isn't just from memory.

Besides history of the bow itself, the documentary included several dramatised reconstructions of notable longbow incidents, including a couple from the 1180s as described by chronicler Gerald of Wales.

He tells, for instance, of a mounted man-at-arms in service to Lord William de Braose who was shot through the thigh and nailed to his horse. When he turned the horse to flee, he was nailed through the other thigh as well. That qualifies as Pinning Stuff with Arrows in my book (and in Hardy's, which is where I confirmed my recollection of it).

The arrowhead would have looked like this...

...or maybe this.

...and this image by Robbie McSweeney of Guillaume de Mello ca. 1185 shows armour similar to what that man-at-arms would have been wearing:

If Gerald isn't "drawing the long bow" himself - which means "exaggerating for the sake of a good yarn", and is an idiom still sometimes heard today - then each arrow would have penetrated:

the skirt of his hauberk (chainmail coat),

the gambeson (padded under-coat) beneath,

the chausse (chainmail stocking) under that,

one side of his linen braies (long pants),

his thigh muscles,

the other side of the braies and chausse,

the leather saddle-skirt,

and finally, as much depth of horsemeat as qualifies for nailing or pinning.

Um...

OUCH!

88 notes

·

View notes

Note

I understand that knights normally followed a fairly set career path: start as a page, get taken on as a squire, and then if they merit it and have resources, knighthood. How did it work for other classes of soldier? How would one go about becoming say, a man at arms, or a specialist like a long bowman or a crossbowman or a pikeman for example?

Ah, excellent question!

One preliminary thing, you do have to be mindful of the distinction between actual training and social organization. Let's take your "career path" for knights, for example - at its heart, the whole page/squire thing was essentially a two-stage apprenticeship, but there was both a mix of actual martial training (I'll get into the curriculum in a bit) and what we would think of as socialization into the noble class - things like music, dancing, literacy, manners, and so forth aren't really directly related to the job of an armored heavy cavalryman, after all.

Importantly, when it comes to the distinction between various ranks, we have to keep in mind the importance of both material resources and sociocultural status. As you note, the difference between a squire and a knight was really about whether the squire could afford the full complement of arms, armor, and a horse, and there were more than a few grown men who were squires their whole lives (this is the inspiration for characters like Squire Dalbridge) because they just didn't have the money to advance to knighthood.

At the same time, the difference between a knight and a man-at-arms came down to social class - in order to be a man-at-arms, you had to have the same training as a knight and own the same equipment (arms, armor, and horse), which is why a lot of the written sources simply call all such men men-at-arms whether they were knights or not - although some sources took more pains to distinguish between the milites gregarii (the plain man-at-arms) and the milites nobiles (which, as you probably have guessed, refers to actual knights).

The former tended to be from the gentry rather than the nobility, and as a result of their lower status, they were usually paid half the wage rate of knights despite doing the same work and taking on the significant risk of providing their own equipment. (The fact that they were cheaper also explains why the proportion of actual knights on the campaign rolls dropped rather rapidly between the 13th and 14th centuries - knights were more expensive, so hiring men-at-arms instead meant you could stretch the budget for heavy cavalry.)

The Knightly Curriculum

As I suggested above, the training for knights was essentially an apprentice system where the page and then the squire provided service to their master in exchange for education. When it comes to the actual content of this training, the curriculum was actually pretty ecletic:

As you might expect, training in arms was an important part of the program. However, this training included a lot more than just swordsmanship. While the sword was very culturally important, when it came to the actual military function of a heavy cavalryman, the lance was arguably of greater importance. Training also tended to include other sidearms - axes, maces, and the like. In later periods, as armor got a lot better and mounted frontal charges tended to be de-emphasized in favor of having men-at-arms fight as dismounted heavy infantry, the curriculum expanded to include new weapons like the poleaxe and other polearms that Gary Gygax was obsessed with.

Training in horsesmanship was also a core part of the curriculum. GRRM is not wrong when he says that "jousting was three-quarters horesemanship," and this is why pages and squires were not only taught formal equestrian lessons, but were also taught how to hawk and hunt as part of their training. Hawking and hunting were the past-times of the nobility in no small part because they involved riding horses very fast through difficult terrain while simultaneously handling either a dangerous animal or weaponry, and were thus were considered good training for future cavalrymen. As Hillary Mantel puts it, "la chasse...we usually say, we gentlemen, that the chase prepares us for war."

Training in armor tends to get downplayed or overlooked, but it was considered so important that a major portion of what pages and squires did was deal with armor - carrying it, maintaining it (scrubbing with abrasives to prevent rust, oiling the straps to keep the leather straps supple, polishing - it was really endless labor), repairing it, putting it on their master and taking it off, and so on and so forth - so that they would understand every step of the process and be able to fend for themselves later on if they didn't have attendants of their own. The famous French knight, Jean "Boucicaut" le Maingre, was held up as an example to pages and squires for constantly wearing full armor while undertaking exercise:

youtube

What About the Man-at-Arms?

As you may have noticed, I've been mostly talking about how knights trained rather than men-at-arms. So how did your gentry-born homme d'armes train? Essentially the same as a knight, but with less of the aristocratic bells and whistles of ritualized service and socialization to the nobility. So a son of the gentry would probably be training under the tutelage of their father or other male relative - and given that we're talking about a society in which the overwhelming majority of people did the same jobs as their parents, often being legally bound to do so, this was a very common phenomenon all the way from peasants upwards - or perhaps from a professional tutor who would most likely be a veteran in working retirement.

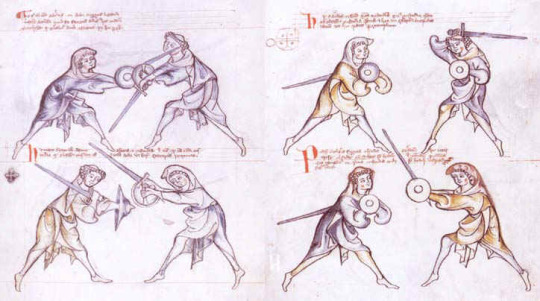

Towards the later Middle Ages, as literacy rates increased and book production expanded to match supply to demand, your more traditional systems of apprenticeship and one-on-one tutoring became supplemented with written manuals of arms. While this genre of military literature goes all the way back to classical antiquity - and indeed, Roman manuals like De re militari were very popular in the Middle Ages, as were translations of Byzantine manuals - these lavishly illustrated manuscripts were both practical teaching tools and status objects for the families who owned them.

Specialists: Longbowmen, Crossbowmen, and Pikemen

Ok, enough about the upper classes, what about the commoners who served as specialist infantry in Medieval and Renaissance armies?

Well, I've already written a bit about longbow training, but the gist of it is that what started out as a (Welsh) hunting tool was recognized by the English royal government as a vital aspect of military readiness, so laws were promulgated that required essentially all but the poorest to own a longbow and that "that every man in the same country, if he be able-bodied, shall, upon holidays, make use, in his games, of bows and arrows… and so learn and practise archery." This training started at a fairly early age and lasted at least a decade, because it involved both the acquisition of technique and the development of the body (not just the arms, but also crucially the back muscles, as the "special sauce" of the English longbowman was his ability to "lay my body in my bow" rather than relying solely on the arms) - such that archeologists can identify longbowmen from the over-development of the shoulder and arm bones.

What about crossbowmen? Well, as I've already written a bit about, one of the major advantages of the crossbow over the longbow is that you could train someone to be a crossbowman in as little as four months, compared to the decade at minimum for a longbowman, because most of what you were teaching them was accuracy in shooting (hence why the recruitment process often involved eye exams) and the procedures for loading and cocking the crossbow - which required a certain amount of physical strength to pull back the string to the nut that would hold it in place, or to work the winch or the lever or the gaffe or the windlass if you were using a heavier crossbow, but nothing like the physical conditioning required for a longbow.

One of the reasons why the term "Genoese" is so often associated with the crossbow is that the Republic of Genoa established a corps of crossbowmen to serve both in the army and as marines in the navy and these experienced soldiers in turn provided a ready supply of labor for mercenary companies. While the captains who recruited on behalf of the great companies might have to put in the up-front investment of equipment (the crossbow and its accessories, pavise shields, armor,and sidearms), they were able to essentially outsource the training costs to the Republic.

When it comes to training, pikemen were somewhere in the middle between the longbowman and the crossbowman. Because pikemen have to fight shoulder-to-shoulder with lots of other pikemen without stabbing one another accidentally or getting their polearms tangled up, coordinating movement and action was vitally important. Hence, pikemen learned a series of quite complicated drills to teach them how to move in formation in different directions, how to change formations from line to square and back, how to switch from pike to sidearm and back, how to work with missile infantry, and so forth.

As I've talked about before, a big part of the reason why Swiss pikemen were so feared on the battlefield is that, because they were very well-drilled and disciplined due to the policies of universal military service adopted by the Swiss cantons, they could execute these drills very quickly, which meant that the Swiss pikemen could turn on a dime from an impenetrable defensive pike square to a shockingly fast and aggressive deep column which beat the ever-loving shit out of the Burgundians, the Hapsburgs, the Italians, the French, and pretty much everyone - until the Swiss ran up against a nasty combination of the German Landsknecht and the Spanish tercio.

#history#military history#knights#men-at-arms#medieval warfare#mercenaries#longbow#crossbow#pike#medieval history#swiss pikemen

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m basically a ranger. Yeah sure I don’t have the hot cloak, or a seaxe and throwing knife- but like, I can do it until I get it right and uh- uh- I can stalk a rabbit! Im ready for my silver oak leaf, please daddy Gilan, make Will take me under his wing.

#rangercore#gilan davidson#fantasy#rangers apprentice#medieval#i love archery#archery#dnd#woods#roving#longbow

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Making process of “The Elegy for the End”

(Best weapon in Genshin Impact)

#genshin fanart#genshin venti#genshin#gaymer#genshing impact#genshin weapons#fantasy#fantasy weapons#stained glass#fantasycore#longbow

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some photos from the Abbey Tournament 2023 at the warbow display featuring myself in the blue tunic.

My bow is a 95lb @ 30 inch draw Hedeby bow

That puts me at 15lbs more than Will, and 5lbs less than Halt from Ranger's Apprentice, aiming eventually for 120lbs@ 30 inches

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

British Army AH-64D Longbow thrilling the crowd at the 2016 Berlin Airshow

#Army Helicopter#AH-64#Longbow#Airshow#Attack helicopter#gunship#Military aviation#Helicopter#Army Air Corps

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is an archer without his arrows? In Medieval warfare, bowmen were also skilled melee fighters, ready to fight up close when their arrow supply ran dry.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

tf2 gameplay

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Inspired by this video)

#poll blog#random polls#silly polls#stupid polls#polls#silly poll#tumblr polls#poll#sports poll#sports#athletic poll#athleticism#physical art#pole fitness#pole dance#pole dancing#archery#bow and arrow#longbow#fitness poll#fitness#exercise#hobbies#fun polls#this or that#pick one#would you rather#gay things#autistic poll#special interest

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

by rampart1028

431 notes

·

View notes

Text

More free hand practise. Letters hard.

#battletech#mechwarrior#miniatures#tabletop miniatures#wargaming#mech#miniature painting#tabletopminiatures#miniature wargaming#longbow#lgb7q#taste the rainbow

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

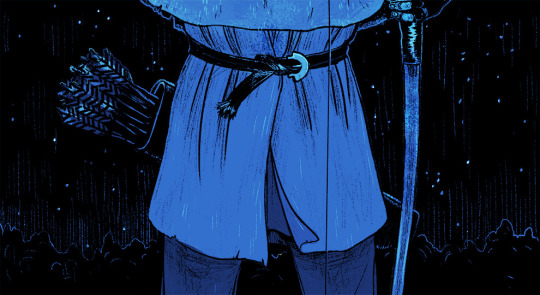

Night Bowman

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

How come the longbow is so associated with the English and their use of the longbow?

I imagine that there have been multiple societies that used the longbow (before or at the same time as the English), but it seems that the English are the most well known users of the longbow (at least in popular culture/thought).

The longbow was originally Welsh, but the English very quickly adopted it as one of their main weapons of war during and after the Edwardian conquest of Wales - that campaign ended in 1283, and by the time of the Battle of Falkirk in 1298, we see the English army now mainly made up of longbowmen (a lot of them Welshmen).

Moreover, the English monarchy enacted laws that reinforced this shift to a longbow-based army: the original Assize of Arms of 1181 had focused on requring freemen of England to own chainmail (or gambesons if you owned less than ten marks), helmets (or just an iron cap if you had ten marks or less), and lances as their main weapon. By the Assize of Arms of 1252, freemen with nine marks or more were required to "array with bow and arrow." By the time of the Statute of Winchester of 1285, even the poorest freemen is expected to have "bows and arrows out of the forest, and in the forest bows and pilets."

Thus, when Edward III starts up the Hundred Years War, the armies that win stunning victories at Crecy and Poitiers (and establish the lasting associaion between England and the longbow) were based on his grandfather's model. Edward would further reinforce royal policy towards longbows by enacting the Archery Law of 1363, which required that "every man … if he be able-bodied, shall, upon holidays, make use, in his games, of bows and arrows… and so learn and practise archery." Thus, longbow practice every Sunday and feast/saint's day became mandatory in England.

The English love affair with the longbow also continued much longer than in other nations. Even after the French began to use cannons against the formations of English longbowmen, and thus regained the upper hand in the Hundred Years War, (something often attributed to their adoption of the longbow, but in reality artillery was the main French adaptation) the English kept on fielding armies of mostly longbowmen. The Battle of Flodden in 1513 was largely fought with longbows; when Henry VIII's flagship the Mary Rose went down in 1545 she had 250 longbows on board (which form the material basis for a lot of our archaelogical understanding of medieval longbows); when the English militia was called up to fight the Spanish Armada in 1588, longbowmen still made up about 10% of their forces.

67 notes

·

View notes