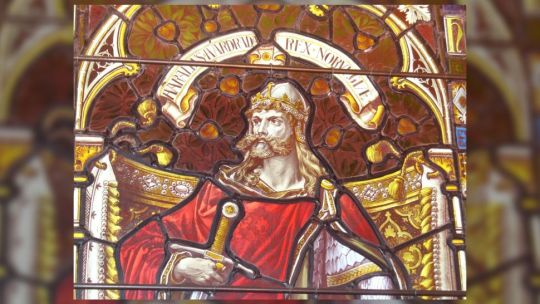

#magnus olafsson

Text

Day 27: Water - Magnus the Good

Did he actually drown or did we just make that up? I don’t even remember at this point

#jenstober23#magnus the good#magnus olafsson#king of norway#vikings#vikings valhalla#netflix valhalla#valhalla hype#medieval norway#north sea empire#water#11th century#history art#traditional art#twttwba#inktober#inktober 2023#drawtober#drawtober 2023#artober#artober 2023#witchtober#witchtober 2023#day 27#scandinavian tag

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irish Coin Daily: Norwegian Imitation of an Hiberno-Norse, Phase VI (Class A, Type 1c) Penny

Date: c. 1102-1103

A Norwegian imitation of an Hiberno-Norse Penny (Phase VI) struck for Norway’s King Magnus III Barefoot (1093-1103) c.1095-1110

This is where it gets really complicated for students of Hiberno-Scandinavian coinage

Is this penny a Norwegian (or Danish) copy of an Irish-made coin, or;

Is it a Norwegian (or Danish) copy of an English-made coin?

If it is the former, where was the…

View On WordPress

#hiberno-scandinavian#King Magnus Barefoot#king of dublin#King of Mann#King of the Northern Isles#King of the Southern Isles#Magnús Óláfsson#Magnús berfœttr#Magnus Barefoot#Magnus Berrføtt#Magnus III Olafsson#Magnus Olavsson#penny#Phase VI (Class A#rare#silver#silver penny#viking dublin#viking penny#vikings#Dublin#hiberno-norse#Type 1c)

0 notes

Text

A Thing Of Vikings Chapter 22: A Ruff But Magnus Wedding

Chapter 22: A Ruff But Magnus Wedding

According to nearly all primary sources, the marriage between Ruffnut Thicknutsdoittor clan Thorston and King Magnus Olafsson of House Fairhair was a love-match, despite the political considerations that instigated both their betrothal and their atypically quick marriage. Both were staunch patrons of the arts, which apparently was the basis of their initial bond. For the duration of their marriage, there is no record of either of them straying into affairs, or of Magnus taking official concubines. This was an uncommon occurrence in medieval Scandinavia to say the least, where approximately a quarter of all monarchs between 700 and 1100 were of illegitimate issue by acknowledged concubines, including Magnus, and Magnus had himself sired an illegitimate daughter several years before his wedding. However, the number of children and love poems that the pair produced speaks volumes for their mutual devotion on its own…

In addition to their personal compatibility, Ruffnut and Magnus were known to have fought alongside each other on multiple occasions. One point that is dryly noted by both their biography-sagas and other primary sources is that the number of enemies slain by her hands was significantly higher than his, due to a combination of her own martial prowess and enemies underestimating her on the basis of her build or gender or both. The most significant portion of these kills apparently came from the Siege of Roskilde, where Ruffnut guarded the stairway that led to their children's nursery, and the skalds and other eyewitness accounts reported that the bodies formed a battlement…

—House Fairhair And The Grand Thing, Oslo, Norway, 1667

AO3 Chapter Link

~~~

My Original Fiction | Original Fiction Patreon

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Silver Coin Featuring Famous Viking King Discovered in Hungary

A metal detectorist in Hungary has unearthed a tiny silver coin marked with the name of a famous Viking king that was lost almost 1,000 years ago.

A metal detectorist has discovered a small silver coin marked with the name of a famous Viking king. However, it was unearthed not in Scandinavia, but in southern Hungary, where it was lost almost 1,000 years ago.

The find has baffled archaeologists, who have struggled to explain how the coin might have ended up there — it's even possible that it arrived with the traveling court of a medieval Hungarian king.

The early Norwegian coin, denominated as a "penning," was not especially valuable at the time, even though it's made from silver, and was worth the equivalent of around $20 in today's money.

"This penning was equivalent to the denar used in Hungary at the time," Máté Varga, an archaeologist at the Rippl-Rónai Museum in the southern Hungarian city of Kaposvár and a doctoral student at Hungary's University of Szeged, told Live Science in an email. "It was not worth much — perhaps enough to feed a family for a day."

Metal detectorist Zoltán Csikós found the silver coin earlier this year at an archaeological site on the outskirts of the village of Várdomb, and handed it over to archaeologist András Németh at the Wosinsky Mór County Museum in the nearby city of Szekszárd.

The Várdomb site holds the remains of the medieval settlement of Kesztölc, one of the most important trading towns in the region at that time. Archaeologists have made hundreds of finds there, including dress ornaments and coins, Varga said.

There is considerable evidence of contact between medieval Hungary and Scandinavia, including Scandinavian artifacts found in Hungary and Hungarian artifacts found in Scandinavia that could have been brought there by trade or traveling craftsmen, Varga said.

But this is the first time a Scandinavian coin has been found in Hungary, he said.

Who was Harald Hardrada?

The coin found at the Várdomb site is in poor condition, but it's recognizable as a Norwegian penning minted between 1046 and 1066 for King Harald Sigurdsson III — also known as Harald Hardrada — at Nidarnes or Nidaros (opens in new tab), a medieval mint at Trondheim in central Norway.

The description of a similar coin (opens in new tab) notes that the front features the name of the king "HARALD REX NO" — meaning Harald, king of Norway — and is decorated with a "triquetra," a three-sided symbol representing Christianity's Holy Trinity.

The other side is marked with a Christian cross in double lines, two ornamental sets of dots, and another inscription naming the master of the mint at Nidarnes.

Harald Hardrada ("Hardrada" translates as "hard ruler" in Norwegian) was the son of a Norwegian chief and half-brother to the Norwegian king Olaf II, according to Britannica (opens in new tab). He lived at the end of the Viking Age, and is sometimes considered the last of the great Viking warrior-kings.

Traditional stories record that Harald fought alongside his half-brother at the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030, where Olaf was defeated and killed by the forces of an alliance between Norwegian rebels and the Danish; Harald fled in exile after that, first to Russia and then to the Byzantine Empire, where he became a prominent military leader.

He returned to Norway in 1045 and became its joint king with his nephew, Magnus I Olafsson; and he became the sole king when Magnus died in battle against Denmark in 1047.

Harald then spent many years trying to obtain the Danish throne, and in 1066 he attempted to conquer England by allying with the rebel forces of Tostig Godwinson, who was trying to take the kingdom from his brother, King Harold Godwinson.

But both Harald and Tostig were killed by Harold Godwinson's forces at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in northern England in 1066; whereupon the victor and his armies had to cross the country in just a few weeks before the Battle of Hastings against William of Normandy — which Harold Godwinson lost, and with it the kingdom of England.

Medieval travels

Advertisement

The penning found at Várdomb could have been lost more than 100 years after it was minted, but it's more likely that it was in circulation for between 10 and 20 years, Varga and Németh said.

That dating gives rise to a possible connection with a medieval Hungarian king named Solomon, who ruled from 1063 to 1087.

According to a medieval Hungarian illuminated manuscript known as the "Képes Krónika" (or "Chronicon Pictum" in Latin), Solomon and his retinue (a group of advisors and important people) encamped in 1074 "above the place called Kesztölc" — and so the archaeologists think one of Solomon's courtiers at that time may have carried, and then lost, the exotic coin.

"The king's court could have included people from all over the world, whether diplomatic or military leaders, who could have had such coins," Varga and Németh said in a statement.

Another possibility is that the silver coin was brought to medieval Kesztölc by a common traveler: the trading town "was crossed by a major road with international traffic, the predecessor of which was a road built in Roman times along the Danube," the researchers said in the statement.

"This road was used not only by kings, but also by merchants, pilgrims, and soldiers from far away, any of whom could have lost the rare silver coin," they wrote.

Further research could clarify the origins of the coin and its connection with the site; while no excavations are planned, Varga said, field surveys and further metal detection will be carried out at the site in the future.

By Tom Metcalfe.

#Silver Coin Featuring Famous Viking King Discovered in Hungary#King Harald Sigurdsson III#Harald Hardrada#archeology#archeolgst#metal detector#coin#silver#silver coin#ancient artifacts#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#penning#viking history#viking culture

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fine we can talk about the English

So. King Knut (Canute) was ruling in England, at least the York area. He conquered him some Denmark. He conquered him some Norway too, and drove Olaf and son Magnus to outlawry. Olaf made a bid to reclaim his kingdom, failed. Knut installed his sons as kings in England, Denmark, and Norway, and, being an old man, promptly died. (Charles take note.)

So in England, Knut's son Harald takes over, but then he dies and Knut's next son Hortha-Knut comes back from Scandinavia to rule, and he sticks around for a few years. Long enough for Magnus Olafsson to come back from Kiev and retake his country, and make a deal with Hortha-Knut that they are such good buddies that if one of them dies without a male heir, the other will inherit.

Ynglings are. Very accustomed to sharing crowns, I have discovered.

So Hortha-Knut dies. Magnus is a bit busy with this dude Svein who keeps trying to conquer Denmark on the grounds that Magnus gave it to him as jarl and who cares if Svein declares himself king and independent, it's his now, don't you know who his father is?? Anyway Edward (Eadward) takes over in England.

Magnus gets shut of Svein, finally, largely by inspiring his army with stories of how Svein's daddy might be a king but Magnus's daddy is a saint, and God is on their side, the daddy of all daddies. So once he's feeling confident in his hold over Norway and Denmark, he sends a message back to England all, "Hey, remember this deal I had with Hortha-Knut?"

And Eadward, that badass pushover, sends a message back, saying, "Look. My dad was king of England, and I was well. When he died my eldest brother Eadmund was king, and I was well. After him my stepfather Knut ruled England, and I was well. And when he died my brother Harald ruled, and I was well. And when he died my brother Hortha-Knut ruled, and I stood by, and all was well, but let me remind you that I yet of the brothers had no kingdom to govern.

"So now you want to come over here and declare yourself king? Let me just say, over my dead body.

"And I will make it easy for you. If you come, I will not raise an army, you can march right in. But you will very much have to kill me with your own hands."

Which Magnus abstains to do.

#it's a very Much Adooooo sort of a message#one woman is fair yet I am well#that she raised me I likewise give her most humble praise#but that I WILL RAISE MY BUGLE ---#Norsebinge#icy sagas#while I'm at it: my word choice in that last line is a deliberate reference to Donne's “Woman's Constancy”

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

The account formerly known as hawkeyezx was followed by: malte, both Alex's parents, Magnus, Alex's cousin and Alexander Olafsson. Explain to me why they would follow some silly account?

Thank you for sharing! 😊 And I agree with you, they wouldn’t. But this also raises some questions… if it’s really Alex, why would all of them, all of a sudden, stop following their friend/family member’s private account? One could argue that Alex removed them as followers, but why? And why go through all that trouble, especially for an account that’s seemingly dormant now? Wouldn’t it be easier to delete and create a new one, if he wanted some kind of “clean slate”? And also, given the fact that this account is private, as well as those of Alex’s parents, how could people see that they were following him? 🤔

0 notes

Photo

List of the kings of Norway (II)

#Olaf II#Olaf II Haraldsson#Canut the Great#Knútr#Cnut the Great#Sweyn Knutsson#Haakon Ericsson#Magnus Olafsson#Magnus I#Harald Hardrada#Harald III#Harald Sigurdsson#Magnus II#Olaf III#Haakon Magnusson#Magnus III#Magnus Barefoot

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

8th October, 1275- The Battle of Ronaldsway

(The area around Ronaldsway, at the south end of the Isle of Man, from the air. Picture from Wikimedia Commons)

Got another battle for you today folks, in keeping with the fact that earlier the Battle of Largs was covered on this blog. That battle, though perhaps not quite so game-changing and pivotal in British history as some sources would have us believe, was still an important moment in the process that saw sovereignty over the islands and western seaboard pass from Norway to the Scottish Crown. With the death of Haakon IV in late 1263, any hopes the Norwegians had of soon resuming their campaign and recouping losses were stymied and King Alexander III quickly capitalised on the situation, sending a force into the Hebrides under the Earl of Buchan and Alan Durward, whose forces simultaneously wreaked devastation and brought home the message of Scottish ascendancy. Hostages were taken for good behaviour and while some of the Hebridean rulers still refused to give into Scottish demands of overlordship, others, including several notable members of the House of Somerled, came into the king of Scotland’s peace more readily.

The story of how the Western Isles were incorporated into the kingdom of Scotland is reasonably well known- or at least the popular, if not wholly accurate and somewhat sanitised, version of the story is more likely to be covered in a Scottish history class than that of the Isle of Man. Nonetheless for a short while this territory also came under the control of the Scottish Crown. At around the same time as Buchan and Durward were sent into the Hebrides, an expedition was also fitted out for the Isle of Man. However, Magnus Olafsson, the King of Man, who was probably quite rightly anxious to avoid a Scottish army being set loose in his own land, pre-empted Alexander’s intervention and met with the king of Scots at Dumfries. There, he did homage and received Alexander’s promise of protection and shelter in Scotland should the king of Norway attempt to take reprisals against him, in return for agreeing to provide military service of ten galleys.

How this new relationship between the kings of Man and Scotland would have panned out in time is impossible to say, as Magnus died at Castle Rushen in late 1265. After this, control of Mann was put in the hands of a succession of royal bailiffs (Lewis and Skye, which were also part of the kingdom of Mann, were put under the control of the Crown and the Earl of Ross respectively) and Alexander’s sovereignty over the island was confirmed by Norway as a result of the Treaty of Perth in 1266. At some point seven hostages were taken for good behaviour as well, and kept by the Sheriff of Dumfries on behalf of the king. To all intents and purposes, Man was to be treated as a possession of the Scottish Crown, whether the Manx liked it or not (this also must have stuck in the throat of the king of England, who lost the opportunity to finally bring Mann under English control as a result of being distracted by domestic strife). However while there was little significant trouble in the Hebrides in the decades after the Treaty of Perth, Man was a different matter and not only were the baillies unpopular, but in general the island’s loss of autonomy and subjugation to the Scottish Crown did not go down well. And thus we are brought to the autumn of 1275, when that simmering discontent came to a head and the Manxmen rose in revolt.

(A seal of Alexander III of Scotland, last king of the House of Dunkeld)

The leader of this movement was Guðrøðr Magnusson (name may also be rendered as Godfrey or Godred), an illegitimate son of the late Magnus, who appears to have been viewed by the majority of the Manx political community as the right man to succeed his father. Quickly gathering support, he soon seized the main castles and strongholds on the island, turfing out the Scots there, and making a bid to reestablish the primacy of the Crovan dynasty. Members of this kindred had ruled in Mann since at least the twelfth century, though at other times their power also extended to the Outer Hebrides, especially Lewis (their main competitors, meanwhile, were the branches of the Mac Somhairle clan in the Inner Hebrides and Argyll- who gave rise to the MacDonalds, MacDougalls, and MacRuaidhris- whose members had occasionally also ruled in Mann). But Godred’s attempts to claim the kingship of Mann that his ancestors once held, naturally aroused the wrath of Alexander III, who immediately acted to prevent the situation getting any further out of hand.

Having raised a force from Galloway and the Hebrides, a fleet was soon on its way south to Mann, landing at Ronaldsway on the south side of the island on the seventh of October. Its leaders were King Alexander’s second cousin John de Vesci, lord of Alnwick; John ‘the Black’ Comyn, lord of Badenoch; Alexander MacDougall lord of Argyll, whose sister had been married to the late Magnus Olafsson; Alan MacRuairi, who twelve years earlier had raided the west coast of Scotland on behalf of Hakon IV of Norway; and Alan, a son of the Earl of Atholl and grandson to Roland/Lachlan of Galloway. Of these the last had already been one of the Crown’s bailiffs of Mann, while two more- MacDougall and MacRuairi- belonged to two of the most prominent septs of the House of Somerled, and their role in the suppression of the Manx revolt says a lot about Alexander’s new power in the Hebrides and on the west coast of the Scottish mainland (nevertheless, Alan MacRuairi’s older brother Dubhgall, the head of the MacRuairis, remained in rebellion and had taken himself off to plunder Ireland a few years before, so not everyone was wholly happy with the situation in the Hebrides, even if it was more accepted than in Mann). Meanwhile the ability to raise men in the Hebrides and Galloway was a testament to the strength of the campaigns of Alexander III and his father respectively in those parts, and the Hebridean galleys were a strong addition to the naval power of the Scottish Crown, which had already shown its ability to exploit the advantages of the galley in its earlier campaigns in the west.

Sources for the Manx side of things are even less informative, though for all his early success Guðrøðr’s force does not seem to have been anywhere near as well-equipped as its enemy. When the Scots landed on the seventh, they sent a peace embassy to offer terms if the Manx surrendered, but Guðrøðr and his counsellors firmly rejected this option. Early the next day- the eighth of October- battle was joined before the sun was even in the sky. It is perhaps rather disappointing, given all the lead-up, that Guðrøðr’s short rebellion ended so swiftly and that the skirmish can be summed up in a few sentences, but the sources, though unfortunately short, make it clear that Ronaldsway was an overwhelming defeat for the Manxmen. Accounts of the battle describe the latter as being ‘naked and unarmed’ and they were almost immediately beaten back by the crossbowmen, archers, and other soldiers of the Scots. Very soon they turned and fled, with the Scots in hot pursuit, cutting down any they could catch and not stopping to spare people on account of sex or rank, to the result that over five hundred are alleged to have died in the battle itself. As Ronaldsway is, even today, very close to the important settlement of Castletown (so named for Castle Rushen, then the main political centre of the island), the flight of the Manx brought the Scots into contact with non-combatants and, both in the chase and after the battle was technically over, the invaders brought destruction to the area. As well as slaying many, they are also supposed to have sacked Rushen Abbey, a significant foundation of the Crovan dynasty and a hugely important religious centre for the Isle of Man.

The Chronicle of Man provided a versified toll of the dead:

‘Ten L’s, three X’s, with five and two to fall,

Manxmen take care lest future evils call.’

Or, in Latin:

‘L decies, X ter et penta, duo cecidere,

Mannica gens de te dampua futura cave.’

(Castle Rushen, in the thirteenth century the main political centre of the Isle of Man, and not far from Ronaldsway. Not my picture.)

Scottish control was quickly- and brutally- reestablished over Mann, while Guðrøðr, is supposed to have fled to Wales with his wife and followers. He was not to be the last of the Crovan dynasty to lay claim to Mann, but for the rest of Alexander III’s reign the island does not appear to have caused any significant trouble. To the Scottish Crown this settled the matter and the young Prince Alexander, son of the Scottish king, was named lord of Man until his early death in 1284, though it is doubtful if he ever played much active role in its governance and the real administration of the island was once again placed in the hands of bailiffs.

However, some historians argue that the aftermath of the Battle of Ronaldsway, since it can hardly have inspired positive feelings towards Scotland, may have promoted the further growth of an anti-Scottish faction in the Manx political community. When Margaret- the infant daughter of Eric II of Norway and granddaughter of Alexander III- inherited the throne of Scotland upon the death of her maternal grandfather in 1286, she also succeeded to the title Lady of Mann. However, when her great-uncle Edward I of England annexed the island a little while before her premature death in September of 1290, nobody on the Isle of Man appears to have complained. After all, the Battle of Ronaldsway- and the destruction that followed- had only occurred fifteen years before, and even prior to that the majority of the Manx had not shown any particular enthusiasm for Scottish sovereignty. The territory was formally restored to King John by Edward I in 1293, though quite some time after the rest of the Scottish realm, and was to pass back and forth between Scotland and England for several more decades, but after the mid-fourteenth century Scottish claims to Mann were largely abandoned and at the end of the century it formally came under English control. The Crovan dynasty, however, would never again hold the title Kings of Mann.

(References below cut)

The Furness continuation of William of Newburgh’s ‘Historia Reru Anglicarum’ in ‘Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II and Richard’, ed. Richard Howlett

The Chronicle of Man in ‘Monumenta de Insula Manniae, or a Collection of National Documents Relating to the Isle of Man’, transl. and ed. J. R. Oliver

‘Early Sources of Scottish History’, A.O. Anderson

John of Fordun’s ‘Chronica Gentis Scotorum’, ed. by W. F. Skene

‘Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000-1306′, G.W.S. Barrow

‘The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland’s Western Seaboard, c. 1100- c.1336′, R. Andrew MacDonald

“The Wars of Scotland, 1214-1371″, by Michael Brown

#Isle of Man#Manx history#Scottish history#Scotland#English history#British Isles#thirteenth century#Magnus Olafsson#Alexander III#Godred Magnusson#Crovan dynasty#House of Somerled#Clann Somhairle#Western Isles#warfare#battles#Norway#Kingdom of Mann and the Isles#House of Dunkeld

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Legbiter”, sword of King Magnus Olafsson of Norway (1073-1103)

288 notes

·

View notes

Text

Norwegian / old norse names and places

Every now and then I come across a book, movie, TV-series, fanfic, game or whatever, that mention a fictional "Norwegian" or "norse" place or person, and it just sounds so wrong it makes me either cringe or ROFL. Really. I still haven't recovered from the 1995 X-files episode, "Død Kalm", which took us to the port of "Tildeskan" where we met "Henry Trondheim", "Halverson" and "Olafsson".

Hopefully this list will keep others from being that “creative” with names. :)

Common names for places, towns and villages in Norway

These names are very generic and suitable for a place, village or town anywhere (and pretty much any time) in Norway. Mix and match prefixes with suffixes for diversity.

Bonus: All of these can also be used as surnames.

Name (meaning) - usage

Nes (headland, cape, ness) - Standalone

Bø (fenced-in field on a farm) - Standalone

Fjell (mountain) - Standalone or prefix/suffix: Fjell- / -fjell

Haug (small hill / large mound) - Standalone or prefix/suffix: Haug- / -haug

Vik, Viken, Vika (inlet, the inlet, the inlet) - Standalone or prefix/suffix: Vik- / -viken / -vika

Ås, Åsen (hill, the hill (larger than "Bakken")) - Standalone or prefix/suffix:

Dal, Dalen (valley, the valley) - Standalone or prefix/suffix:

Berg (small mountain) - Standalone or prefix/suffix: Berg(s)- / -berg

Sand (sand) - Standalone or prefix/suffix: Sand- / -sand

Strand (beach) - Standalone or prefix/suffix: Strand- / -strand

Li (hill) - Standalone or prefix/suffix: Li- / -li

Gran (spruce) - Standalone or prefix: Gran-

Bratt (steep) - prefix only: Bratt-

Myr (bog, mire) - prefix only: Myr-

Neset, Nesset (the headland, the cape, the ness) - Standalone or suffix: -neset / -nesset

Odden (foreland, headland) - Standalone or suffix: -odden

Våg (cove, bay) - Standalone or suffix: -våg

Lund (grove) - Standalone or suffix: -lund

Sund (sound, strait) - Standalone or suffix: -sund

Skog (forest) prefix/suffix: Skog- / -skog

Øy (island) prefix/suffix: Øy- / -øy

øya (the island) - suffix only: -øya

bakken (the hill) - suffix only: -bakken

gard / gård / gården (farm / farm / the farm) - suffix only: -gard / -gård / -gården

elv, -elva (river, the river) suffix only: -elv / -elva

stad (old word for town/place) suffix only: -stad

vannet (the lake) - suffix only: -vannet

Common words that can be used as prefix to any of the suffixes above

Svart- (black)

Lille- (little/small)

Sol- (sun)

Brei-/Bred- (wide)

Stor- (big)

Lang- (long)

Common Norwegian surnames (contemporary)

Heredatory surnames didn't become mandatory in Norway until 1923. Many took the name from the farm or place they lived, or just changed their primary patronyms into hereditary patronyms. Example: Helgessønn/Helgesdatter (son of Helge / daughter of Helge) became Helgesen.

Alm

Andersen

Anderssen

Antonsen

Aspelund

Bakke

Bakken

Bang

Berg

Bjerkan

Bråthen

Christensen

Corneliussen

Dahl

Dahlberg

Danielsen

Dyrnes

Dørum

Eide

Ellingsen

Erdal

Eriksen

Falch

Fredriksen

Foss

Fure

Fylling

Gabrielsen

Gran

Grønning

Halvorsen

Hansen

Hanssen

Hay

Hoff

Holm

Holt

Husby

Isaksen

Iversen

Jacobsen

Jensen

Jenssen

Johansen

Karlsen

Klausen

Konradsen

Kristensen

Kristiansen

Larsen

Larssen

Lie

Lien

Lund

Løvold

Magnussen

Meyer

Mikalsen

Mo

Moen

Myhre

Myklebust

Mørk

Ness

Nilsen

Olavsen

Olsen

Paulsen

Pettersen

Prestegård

Rasmussen

Riise

Rogstad

Ruud

Simonsen

Solbakken

Solli

Stokke

Strøm

Sund

Svendsen

Thorvaldsen

Torp

Thune

Tønnesen

Ueland

Ulven

Urdal

Vik

Vinje

Wahl

Wik

Wilhelmsen

Zakariassen

Ødegård

Årseth

Årvik

Ås, Aas

Åsen, Aasen

Common Norwegian names -- 1980 - present

Men

Anders

André

Andreas

Are

Arne

Atle

Bjørn

Cato

Chris

Christian, Kristian

Christoffer, Kristoffer

Daniel

David

Dennis

Elias

Emil

Espen

Erik, Eric

Eirik

Fredrik

Filip

Geir

Harald

Helge

Hans

Henning

Håkon, Haakon

Håvard

Isak

Jan

Joachim

Johan

Johannes

John, Jon

Johnny

Jonas

Jonathan

Kim

Kristian, Christian

Kristoffer, Christoffer

Lars

Lucas, Lukas

Mads, Mats

Magnus

Martin

Michael, Mikael

Morten

Niklas

Nils

Odin

Ole

Ove

Paul

Per

Peter, Petter

Preben

Pål

Richard, Rikard

Roger

Sebastian

Simen

Simon

Sindre

Sondre

Stian

Terje

Thomas

Thor, Tor

Thore, Tore

Vegard

Werner

William

Øystein

Åge

Åsmund

Women

Andrea

Ane, Anne

Anette, Annette

Annika, Anniken

Astrid

Bente

Camilla

Carina

Cathrine

Celine

Charlotte

Christin, Kristin

Christina, Kristina

Christine, Kristine

Elin, Eline

Elise

Elisabeth

Emilie

Eva

Frida

Grete, Grethe

Hanne

Hege

Heidi

Helene

Hilde

Ida

Ine

Ingrid

Ingvill, Ingvild

Isabel, Isabell, Isabelle

Iselin

Jannicke

Janine

Jeanette

Jennie, Jenny

Julia, Julie

Karoline (Kine)

Katrin, Katrine

Kristin, Christin

Lea, Leah

Lena, Lene

Linda

Line

Linn

Linnea

Lise, Lisa

Liv, Live

Mai, May

Maja

Malin

Margrete, Margrethe

Mari, Maria, Marie

Mariann, Marianne

Marte, Marthe

Mette

Monica

Nina

Nora

Oda

Pia

Ragnhild

Randi

Rikke

Sara, Sarah

Silje

Siv

Stina, Stine

Susann, Susanne

Tanja

Tina, Tine

Tiril

Tone

Trine

Vilde

Vera

Veronica

Wenche

Åse

Åshild

Common Norwegian names - 1800 - 1980

Men

Aksel

Albert

Anders

Andreas

Anker

Ansgar

Arne

Arnt

Arve

Asle

Atle

Birger

Bård

Charles

Edmund

Edvard

Egon

Erling

Even

Fred

Fredrik

Frode

Geir

Georg

Gunnar

Gunvald

Gustav

Harald

Helge

Hilmar

Håkon, Haakon

Ivar

Ingvar

Jens

Jesper

Jørgen

Joakim

Karl

Karsten, Karstein

Kjell

Klaus

Kolbein

Kolbjørn

Kristian

Kåre

Lars

Lavrans

Leif

Lossius

Ludvig

Magne

Magnus

Nikolai

Nils

Odd

Oddvar

Odin

Ola

Olai

Olaf

Olav

Ole

Omar

Oscar, Oskar

Peder

Per

Petter

Philip, Phillip

Pål

Ragnar

Rikard

Roald

Roar (also Hroar)

Rolf

Rune

Sigurd

Sigvard, Sigvart

Simon

Svein

Sverre

Tarjei

Terje

Toralf, Thoralf

Torbjørn, Thorbjørn

Torleif, Thorleif

Torstein, Thorstein

Torvald, Thorvald

Trond

Ulf

Ulrik

Valdemar

Wilhelm

Willy

Åge

Women

Albertine

Alice, Alise

Alma

Anita

Anna

Annbjørg

Asbjørg

Astrid

Aud

Bente

Berit

Birgit

Birgitte

Bjørg

Bjørgun

Bodil

Borghild

Dagny

Dagrun

Edel

Ella

Ellen

Elsa

Fredrikke

Frida

Gerd

Gjertrud

Gunhild

Gyda

Hanna, Hannah

Helga

Henny

Herdis

Hilda

Hilde

Hjørdis

Ingeborg

Inger

Irene

Johanna, Johanne

Jorun, Jorunn

Josefine

Judith

Kari

Karin

Kirsten

Kitty

Kjersti

Laila

Lilli, Lilly

Lisa, Lise

Liv

Lovise

Mathilde

Margaret

Marit

Martha

Molly

Nanna

Oddrun

Oddveig

Olga

Ragna

Ragnhild

Rigmor

Sara

Signe

Sissel

Solbjørg

Solveig

Solvår

Svanhild

Sylvi

Sølvi

Tora

Torhild, Toril, Torill

Torun, Torunn

Tove

Valborg

Ylva

Åse

Åshild

Names usage

Double names, like Ragnhild Johanne or Ole Martin are common in Norway. Just keep them as two names and don't use "-", and you'll be safe, even if it ends up a tongue twister. Using only one of two given names is also common practice.

In Norway everyone is on a first name basis. Students call teachers and other kids' parents by their first name, workers call their boss by their first name, we call our Prime Minister by her first name (journalists will use her title when speaking to her though). Some senior citizens still use surnames and titles when speaking of or to people their own age.

There are some exceptions. For example, a doctor may be referred to as Dr. Lastname when we speak of them, but first name is used when speaking to them. A priest is "the priest" when speaking of him/her and their first name is used when spaking to them. In the millitary only surnames (and ranks) are used. If you meet Harald, the King of Norway, in an official setting you will refer to him as "Kongen" (the king). If you run into him at the gas station, or while hiking, he is "Harald".

If you don't know someone's name it is okay to use their title, or just say "you".

Names for pets (contemporary)

Dogs

Laika (f)

Bamse (m) (bear)

Tinka (f)

Loke/Loki (m)

+ characters from TV/film/books...

Cats

Melis (m/f) (powdered sugar)

Mango (m/f) (mango)

Pus (f) (kitty)

Mons (m) (tomcat)

Nala (f)

Pusur (m) (Garfield)

Felix (m)

Simba (m)

+ characters from TV/film/books...

Horses

Pajazz (m)

Mulan (f)

Balder (m) - cold blood

Kompis (m) (pal)

Freya (f) - cold blood

+ characters from TV/film/books...

Rabbits

Trampe (m) (Thumper)

Trulte (f)

+ characters from TV/film/books...

Cows (yes, I am serious)

Dagros

Rosa

Mira

Luna

Sara

+ characters from TV/film - Disney is popular, as are the Kardashians :)

Road and street names

Storgata (usually the main street)

Kongens gate (the king's street)

Dronningens gate (the queen's street)

Jernbanegata (railroad street)

Jernbaneveien (railroad road)

Sjøgata (ocean street)

Sjøveien, Sjøvegen (ocean road)

Skolegata (school street)

Torvgata (plaza street)

Industrigata (industrial street)

Industriveien (industrial road)

Prefixes

Blåbær- (blueberry)

Bringebær- (raspberry)

Bjørke- (birch)

Aspe- (asp)

Kastanje- (chestnut)

Solsikke- (sun flower)

Blåklokke- (blue bell)

Nype- (rosehip)

Kirke- (church)

Park- (park)

Suffixes

-veien, -vegen (the road)

-stien (the path)

Other

Torvet (the plaza) - standalone or suffix: -torvet

Havna (the port) - standalone or suffix: -havna

Kaia (the port) - standalone or suffix: -kaia

Safe solution: use a first name or surname as prefix.

Old norse

Men’s names

Agnarr (Agnar)

Alfr (Alf)

Ámundi (Amund)

Ánarr

Árngrimr (Arngrim)

Askr (Ask)

Auðun (Audun)

Baldr (Balder)

Beinir

Bjørn

Burr

Borkr

Dagfinnr (Dagfinn)

Davið (David)

Drengr

Durinn

Einarr (Einar)

Eirikr (Eirik)

Eivindr (Eivind)

Erlingr (Erling)

Fafnir

Flóki

Freyr (Frey)

Fuldarr

Galinn

Gautarr (Gaute)

Gegnir

Geirr (Geir)

Glóinn

Grímarr (Grimar)

Hafli

Hakon

Hallsteinn (Hallstein)

Haraldr (Harald)

Haukr (Hauk)

Heðinn (Hedin, Hedinn)

Helgi (Helge)

Hrafn, Hrafni (Ravn)

Hrafnkell (Ravnkjell)

Iarl (Jarl)

Ingolfr (Ingolf)

Iuar (Ivar)

Jafnhárr

Jón

Jóngeirr

Kál

Kiaran

Klaus

Knútr (Knut)

Kolgrimr (Kolgrim)

Kolr (Kol)

Leifr (Leif)

Loki

Lyngvi

Magnus

Mikjáll (Mikal, Mikkel)

Mór

Morði

Nesbjørn

Nokkvi

Oddr (Odd)

Oddbjørn

Oðin (Odin)

Olafr (Olaf)

Ormr (Orm)

Otr

Ouden

Pálni

Pedr

Ragnarr (Ragnar)

Ragnvaldr (Ragnvald)

Randr (Rand)

Róaldr (Roald)

Rólfr (Rolf)

Salvi

Sigarr (Sigar)

Sigbjørn

Sigurðr (Sigurd)

Skarpe

Snorri (Snorre)

Steinn (Stein)

Sveinn (Svein)

Teitr

Þor (Thor/Tor)

Þórbjørn (Thorbjørn/Torbjørn)

Þorsteinn (Thorstein/Torstein)

Tryggr (Trygg)

Týr

Ulfár

Ulfheðinn (Ulvhedin)

Ulfr (Ulf)

Vakr

Vani

Veigr

Viðarr (Vidar)

Yngvarr (Yngvar)

Æsi

Women's names

Anna

Arnfriðr (Arnfrid)

Ása

Bera

Bergdís (Bergdis)

Biørg (Bjørg)

Cecilia

Cecilie

Christina

Dagný (Dagny)

Dagrún (Dagrun)

Dís

Dísa

Edda

Elin

Ellisif (Ellisiv)

Freyja (Freya)

Friða (Frida)

Frigg

Gerðr (Gerd)

Gertrud

Grima

Gyða (Gyda)

Hadda

Hallbéra

Hallkatla

Herdís (Herdis)

Hildigunnr (Hildegunn)

Huld

Hvít

Ida

Iðunn (Idun, Idunn)

Ingríðr (Ingrid)

Johanna

Jórunn (Jorun, Jorunn)

Juliana

Katla

Katrine

Kristín (Kristin)

Leikný (Leikny)

Lif (Liv)

Magnhildr (Magnhild)

Mjøll

Myrgiol

Nál

Nanna

Nótt

Oda

Oddný (Oddny)

Ólaug (Olaug)

Rafnhildr (Ragnhild)

Rán

Rannveíg

Ríkví (Rikvi, Rikke)

Rúna (Runa)

Roskva

Sága (Saga)

Sif (Siv)

Sigriðr (Sigrid)

Skaði (Skadi)

Skuld

Svana

Sýn

Solveig

Tekla

Tóra (Tora)

Trana

Ulfhildr (Ulfhild)

Una

Urðr (Urd)

Valborg

Vigdís (Viigdis)

Vírún

Yngvildr (Ingvill, Ingvild)

Yrsa

Bynames

Bynames, or nicknames, could be neutral, praising or condescending. Usually bynames described a person's

body, bodyparts, bodily features

age

kinship and descent

territorial origin

knowledge, belief, spirituality

clothing, armour

occupation, social position

nature

Examples:

Eirik Blodøks (Eirik Blood-Axe), Gammel-Anna (old Anna), Halte-Ása (limping Ása).

I suggest that you stick with English for bynames, or use (relatively) modern language if you are writing in Norwegian.

Surnames

Surnames weren't really a thing until 1923 when they became mandatory. Before 1923 patronyms (son/daughter of) were used, and the name of the farm you lived on was often added as an address.

For instance: Helgi Eiriksøn (Helgi, son of Eirik), who lived at the farm called Vollr (grass field), would be called Helgi Eiriksøn Vollr. If he moved to the farm called Haugr his name would change to Helgi Eiriksøn Haugr.

Patronyms

Men: Use father's first name and add -sen /-son /-sønn

Women: Use father's first name and add -dotter / -dottir / -datter

Farm names

Farm names were usually relevant and derived from either the location, a nearby landmark, nature or from occupation.

I suggest you stick with the modern forms for farm names.

Old Norse (meaning) - modern

Bekkr (stream) - Bekk, Bekken

Dalr (valley) - Dal, Dahl

Horn (horn) - Horn

Vollr (field) - Vold, Volden

Lundr (grove) - Lund

The list of common names for places/villages/towns is still valid, although the spelling is modern. Just keep it simple and make "clever" combos based on meaning.

536 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arheologii au confirmat că au descoperit primul coif viking din Regatul Unit

Coiful a fost descoperit în 1950 și deși nu existau dubii legate de origine acestuia, vârsta reprezenta un mister.

În anii 1950, în Yarm, o localitate din North Yorkshire, arheologii au descoperit un coif din fier, care, după stilul în care fusese realizat părea a avea origini vikinge. Un studiu recent, realizat de către oamenii de știință de la Universitatea Durham, Regatul Unit a stabilit proveniența acestuia.

Analizele au indicat faptul că acest coif din fier a fost realizat în jurul secolului al X-lea în nordul Angliei și că are, într-adevăr o proveniență anglo-scandinavă. Trebuie precizat faptul că deși modalitatea în care a fost realizat indica o astfel de origine, oamenii de știință aveau dubii legate de vechimea acestuia, notează The History Blog.

Un coif unic în lume

Cercetătorii explică faptul că acest coif este unic în lume și asta deoarece deși mai există un singur coif viking în lume, acestea sunt realizat în stiluri diferite. Cel de al doilea coif despre care se știe sigur că are origini vikinge a fost descoperit în anul 1943, în Haugsbygd, Norvegia.

Situația coifurilor vikinge este una paradoxală, în mod intuitiv am crede faptul că de la primul raid asupra Lindisfarne care a avut loc în 793 și până la ultimele raiduri ale regelui Magnus Olafsson (1093-1103), ar fi trebuit să rămâne o cantitate mare de artefacte vikinge, printre care și coifuri.

Din nefericire, situația de la fața locului este diferită, arheologii reușind să descopere doar coifuri care precedau era vikingă în insulele britanice. O posibilă explicație pentru acest fenomen ar putea fi reprezentată de creștinarea anglo-scandinavilor , ceea ce a dus la schimbarea obiceiurilor funerare.

Coiful descoperit în Norvegia făcea parte din ofrandele funerare oferite unei persoane decedate. De asemenea, lângă acesta au fost descoperite arme și chiar și o cămașă de zale. Coiful descoperit la Yarm nu făcea parte dintr-o ofrandă și, cel mai probabil, a fost aruncat în apa unui râu.

Istoricii explică faptul că în secolul al X-lea elitele saxonilor foloseau coifuri decorate pentru a-și demonstra autoritatea și puterea. Cel mai probabil astfel de coifuri, precum cel din Yarm, erau folosite de către războinicii obișnuiți, având utilizări practice.

Coiful precede fondarea satului Yarm, a fost descoperit pe malul estic al râului Tees, care poate fi fost un chei înainte de înființarea orașului. Este confecționat din plăci subțiri simple de fier nituite împreună cu benzi de fier. În partea de sus a benzii laterale artizanii au pus un buton decorativ.

Studiul The Yarm Helmet a fost publicat în Medieval Archeology.

Citește și:

Prima excavare a unei nave funerare a vikingilor din ultimul secol va avea loc în Norvegia

Un obiect din vremea vikingilor, descoperit în Estonia

Ruinele unei săli a miedului, unul dintre cele mai importante locuri ale vikingilor, au fost descoperite în nordul Regatului Unit

Descoperire impresionantă în Islanda: cea mai veche așezare vikingă și un tezaur de mare valoare

Articolul Arheologii au confirmat că au descoperit primul coif viking din Regatul Unit apare prima dată în Descopera.ro.

0 notes

Text

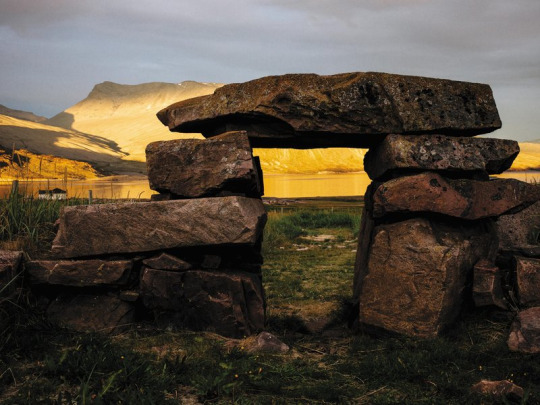

Why Did Greenland’s Vikings Vanish?

*** This is a very long post. Longest I have ever posted. Prepare to scroll ***

For more pictures please visit the http://www.smithsonianmag.com

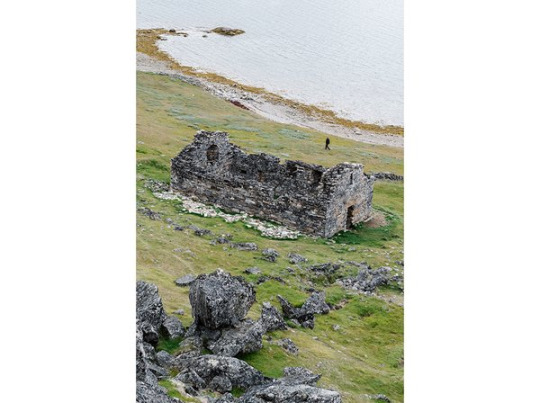

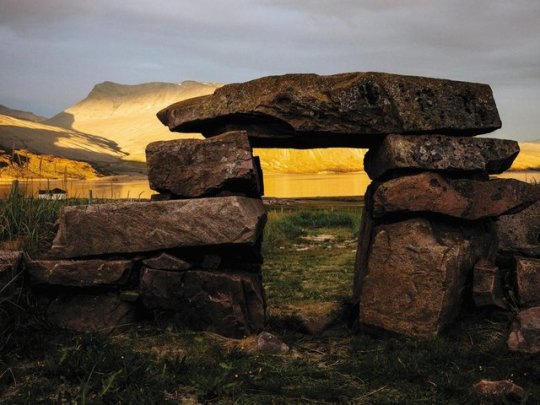

On the grassy slope of a fjord near the southernmost tip of Greenland stand the ruins of a church built by Viking settlers more than a century before Columbus sailed to the Americas. The thick granite-block walls remain intact, as do the 20-foot-high gables. The wooden roof, rafters and doors collapsed and rotted away long ago. Now sheep come and go at will, munching wild thyme where devout Norse Christian converts once knelt in prayer.

The Vikings called this fjord Hvalsey, which means “Whale Island” in Old Norse. It was here that Sigrid Bjornsdottir wed Thorstein Olafsson on Sunday, September 16, 1408. The couple had been sailing from Norway to Iceland when they were blown off course; they ended up settling in Greenland, which by then had been a Viking colony for some 400 years. Their marriage was mentioned in three letters written between 1409 and 1424, and was then recorded for posterity by medieval Icelandic scribes.

Another record from the period noted that one person had been burned at the stake at Hvalsey for witchcraft.But the documents are most remarkable—and baffling—for what they don’t contain: any hint of hardship or imminent catastrophe for the Viking settlers in Greenland, who’d been living at the very edge of the known world ever since a renegade Icelander named Erik the Red arrived in a fleet of 14 longships in 985. For those letters were the last anyone ever heard from the Norse Greenlanders.

They vanished from history.“If there was trouble, we might reasonably have thought that there would be some mention of it,” says Ian Simpson, an archaeologist at the University of Stirling, in Scotland. But according to the letters, he says, “it was just an ordinary wedding in an orderly community.”Europeans didn’t return to Greenland until the early 18th century.

When they did, they found the ruins of the Viking settlements but no trace of the inhabitants. The fate of Greenland’s Vikings—who never numbered more than 2,500—has intrigued and confounded generations of archaeologists.Those tough seafaring warriors came to one of the world’s most formidable environments and made it their home. And they didn’t just get by: They built manor houses and hundreds of farms; they imported stained glass; they raised sheep, goats and cattle; they traded furs, walrus-tusk ivory, live polar bears and other exotic arctic goods with Europe. “These guys were really out on the frontier,” says Andrew Dugmore, a geographer at the University of Edinburgh. “They’re not just there for a few years. They’re there for generations—for centuries.”So what happened to them?

Thomas McGovern used to think he knew. An archaeologist at Hunter College of the City University of New York, McGovern has spent more than 40 years piecing together the history of the Norse settlements in Greenland. With his heavy white beard and thick build, he could pass for a Viking chieftain, albeit a bespectacled one. Over Skype, here’s how he summarized what had until recently been the consensus view, which he helped establish: “Dumb Norsemen go into the north outside the range of their economy, mess up the environment and then they all die when it gets cold.”

Accordingly, the Vikings were not just dumb, they also had dumb luck: They discovered Greenland during a time known as the Medieval Warm Period, which lasted from about 900 to 1300. Sea ice decreased during those centuries, so sailing from Scandinavia to Greenland became less hazardous. Longer growing seasons made it feasible to graze cattle, sheep and goats in the meadows along sheltered fjords on Greenland’s southwest coast. In short, the Vikings simply transplanted their medieval European lifestyle to an uninhabited new land, theirs for the taking.

But eventually, the conventional narrative continues, they had problems. Overgrazing led to soil erosion. A lack of wood—Greenland has very few trees, mostly scrubby birch and willow in the southernmost fjords—prevented them from building new ships or repairing old ones. But the greatest challenge—and the coup de grâce—came when the climate began to cool, triggered by an event on the far side of the world.

In 1257, a volcano on the Indonesian island of Lombok erupted. Geologists rank it as the most powerful eruption of the last 7,000 years. Climate scientists have found its ashy signature in ice cores drilled in Antarctica and in Greenland’s vast ice sheet, which covers some 80 percent of the country. Sulfur ejected from the volcano into the stratosphere reflected solar energy back into space, cooling Earth’s climate. “It had a global impact,” McGovern says. “Europeans had a long period of famine”—like Scotland’s infamous “seven ill years” in the 1690s, but worse. “The onset was somewhere just after 1300 and continued into the 1320s, 1340s. It was pretty grim. A lot of people starving to death.”

Amid that calamity, so the story goes, Greenland’s Vikings—numbering 5,000 at their peak—never gave up their old ways. They failed to learn from the Inuit, who arrived in northern Greenland a century or two after the Vikings landed in the south. They kept their livestock, and when their animals starved, so did they. The more flexible Inuit, with a culture focused on hunting marine mammals, thrived.

That is what archaeologists believed until a few years ago. McGovern’s own PhD dissertation made the same arguments. Jared Diamond, the UCLA geographer, showcased the idea in Collapse, his 2005 best seller about environmental catastrophes. “The Norse were undone by the same social glue that had enabled them to master Greenland’s difficulties,” Diamond wrote. “The values to which people cling most stubbornly under inappropriate conditions are those values that were previously the source of their greatest triumphs over adversity.”

But over the last decade a radically different picture of Viking life in Greenland has started to emerge from the remains of the old settlements, and it has received scant coverage outside of academia. “It’s a good thing they can’t make you give your PhD back once you’ve got it,” McGovern jokes. He and the small community of scholars who study the Norse experience in Greenland no longer believe that the Vikings were ever so numerous, or heedlessly despoiled their new home, or failed to adapt when confronted with challenges that threatened them with annihilation.

“It’s a very different story from my dissertation,” says McGovern. “It’s scarier. You can do a lot of things right—you can be highly adaptive; you can be very flexible; you can be resilient—and you go extinct anyway.” And according to other archaeologists, the plot thickens even more: It may be that Greenland’s Vikings didn’t vanish, at least not all of them.

Lush grass now covers most of what was once the most important Viking settlement in Greenland. Gardar, as the Norse called it, was the official residence of their bishop. A few foundation stones are all that remain of Gardar’s cathedral, the pride of Norse Greenland, with stained glass and a heavy bronze bell. Far more impressive now are the nearby ruins of an enormous barn. Vikings from Sweden to Greenland measured their status by the cattle they owned, and the Greenlanders spared no effort to protect their livestock. The barn’s Stonehenge-like partition and the thick turf and stone walls that sheltered prized animals during brutal winters have endured longer than Gardar’s most sacred architecture.

Gardar’s ruins occupy a small fenced-in field abutting the backyards of Igaliku, an Inuit sheep-farming community of about 30 brightly painted wooden houses overlooking a fjord backed by 5,000-foot-high snowcapped mountains. No roads run between towns in Greenland—planes and boats are the only options for traversing a coastline corrugated by innumerable fjords and glacial tongues. On an uncommonly warm and bright August afternoon, I caught a boat from Igaliku with a Slovenian photographer named Ciril Jazbec and rode a few miles southwest on Aniaaq fjord, a region Erik the Red must have known well. Late in the afternoon, with the arctic summer sun still high in the sky, we got off at a rocky beach where an Inuit farmer named Magnus Hansen was waiting for us in his pickup truck. After we loaded the truck with our backpacks and essential supplies requested by the archaeologists—a case of beer, two bottles of Scotch, a carton of menthol cigarettes and some tins of snuff—Hansen drove us to our destination: a Viking homestead being excavated by Konrad Smiarowski, one of McGovern’s doctoral students.

The homestead lies at the end of a hilly dirt road a few miles inland on Hansen’s farm. It’s no accident that most modern Inuit farms in Greenland are found near Viking sites: On our trip down the fjord, we were told that every local farmer knows the Norse chose the best locations for their homesteads.

The Vikings established two outposts in Greenland: one along the fjords of the southwest coast, known historically as the Eastern Settlement, where Gardar is located, and a smaller colony about 240 miles north, called the Western Settlement. Nearly every summer for the last several years, Smiarowski has returned to various sites in the Eastern Settlement to understand how the Vikings managed to live here for so many centuries, and what happened to them in the end.

This season’s site, a thousand-year-old Norse homestead, was once part of a vital community. “Everyone was connected over this huge landscape,” Smiarowski says. “If we walked for a day we could visit probably 20 different farms.”

He and his team of seven students have spent several weeks digging into a midden—a trash heap—just below the homestead’s tumbled ruins. On a cold, damp morning, Cameron Turley, a PhD candidate at the City University of New York, stands in the ankle-deep water of a drainage ditch. He’ll spend most of the day here, a heavy hose draped over his shoulder, rinsing mud from artifacts collected in a wood-framed sieve held by Michalina Kardynal, an undergraduate from Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University in Warsaw. This morning they’ve found a delicate wooden comb, its teeth intact. They’re also finding seal bones. Lots of them.

“Probably about 50 percent of all bones at this site will be seal bones,” Smiarowski says as we stand by the drainage ditch in a light rain. He speaks from experience: Seal bones have been abundant at every site he has studied, and his findings have been pivotal in reassessing how the Norse adapted to life in Greenland. The ubiquity of seal bones is evidence that the Norse began hunting the animals “from the very beginning,” Smiarowski says. “We see harp and hooded seal bones from the earliest layers at all sites.”

A seal-based diet would have been a drastic shift from beef-and-dairy-centric Scandinavian fare. But a study of human skeletal remains from both the Eastern and Western settlements showed that the Vikings quickly adopted a new diet. Over time, the food we eat leaves a chemical stamp on our bones—marine-based diets mark us with different ratios of certain chemical elements than terrestrial foods do. Five years ago, researchers based in Scandinavia and Scotland analyzed the skeletons of 118 individuals from the earliest periods of settlement to the latest. The results perfectly complement Smiarowski’s fieldwork: Over time, people ate an increasingly marine diet, he says.

It’s raining heavily now, and we’re huddled beneath a blue tarp next to the midden, sipping coffee and ingesting some terrestrial chemical elements in the form of cookies. In the earliest days of the settlements, Smiarowski says, the study found that marine animals made up 30 to 40 percent of the Norse diet. The percentage steadily climbed, until, by the end of the settlement period, 80 percent of the Norse diet came from the sea. Beef eventually became a luxury, most likely because the volcano-induced climate change made it vastly more difficult to raise cattle in Greenland.

Judging from the bones Smiarowski has uncovered, most of the seafood consisted of seals—few fish bones have been found. Yet it appears the Norse were careful: They limited their hunting of the local harbor seal, Phoca vitulina, a species that raises its young on beaches, making it easy prey. (The harbor seal is critically endangered in Greenland today due to overhunting.) “They could have wiped them out, and they didn’t,” Smiarowski says. Instead, they pursued the more abundant—and more difficult to catch—harp seal, Phoca groenlandica, which migrates up the west coast of Greenland every spring on the way from Canada. Those hunts, he says, must have been well-organized communal affairs, with the meat distributed to the entire settlement—seal bones have been found at homestead sites even far inland. The regular arrival of the seals in the spring, just when the Vikings’ winter stores of cheese and meat were running low, would have been keenly anticipated.

“People came from different farms; some provided labor, some provided boats,” Smiarowski says, speculating. “Maybe there were several centers organizing things along the coast of the Eastern Settlement. Then the catch was divided among the farms, I would assume according to how much each farm contributed to the hunt.” The annual spring seal hunt might have resembled communal whale hunts practiced to this day by the Faroe Islanders, who are the descendants of Vikings.

The Norse harnessed their organizational energy for an even more important task: annual walrus hunts. Smiarowski, McGovern and other archaeologists now suspect that the Vikings first traveled to Greenland not in search of new land to farm—a motive mentioned in some of the old sagas—but to acquire walrus-tusk ivory, one of medieval Europe’s most valuable trade items. Who, they ask, would risk crossing hundreds of miles of arctic seas just to farm in conditions far worse than those at home? As a low-bulk, high-value item, ivory would have been an irresistible lure for seafaring traders.

Many ivory artifacts from the Middle Ages, whether religious or secular, were carved from walrus tusks, and the Vikings, with their ships and far-flung trading networks, monopolized the commodity in Northern Europe. After hunting walruses to extinction in Iceland, the Norse must have sought them out in Greenland. They found large herds in Disko Bay, about 600 miles north of the Eastern Settlement and 300 miles north of the Western Settlement. “The sagas would have us believe that it was Erik the Red who went out and explored [Greenland],” says Jette Arneborg, a senior researcher at the National Museum of Denmark, who, like McGovern, has studied the Norse settlements for decades. “But the initiative might have been from elite farmers in Iceland who wanted to keep up the ivory trade—it might have been in an attempt to continue this trade that they went farther west.”

Smiarowski and other archaeologists have unearthed ivory fragments at nearly every site they’ve studied. It seems the Eastern and Western settlements may have pooled their resources in an annual walrus hunt, sending out parties of young men every summer. “An individual farm couldn’t do it,” he says. “You would need a really good boat and a crew. And you need to get there. It’s far away.” Written records from the period mention sailing times of 27 days to the hunting grounds from the Eastern Settlement and 15 days from the Western Settlement.

To maximize cargo space, the walrus hunters would have returned home with only the most valuable parts of the animal—the hides, which were fashioned into ships’ rigging, and parts of the animals’ skulls. “They did the extraction of the ivory here on-site,” Smiarowski says. “Not that many actually on this site here, but on most other sites you have these chips of walrus maxilla [the upper jaw]—very dense bone. It’s quite distinct from other bones. It’s almost like rock—very hard.”

How profitable was the ivory trade? Every six years, the Norse in Greenland and Iceland paid a tithe to the Norwegian king. A document from 1327, recording the shipment of a single boatload of tusks to Bergen, Norway, shows that that boatload, with tusks from 260 walruses, was worth more than all the woolen cloth sent to the king by nearly 4,000 Icelandic farms for one six-year period.

Archaeologists once assumed that the Norse in Greenland were primarily farmers who did some hunting on the side. Now it seems clear that the reverse was true. They were ivory hunters first and foremost, their farms only a means to an end. Why else would ivory fragments be so prevalent among the excavated sites? And why else would the Vikings send so many able-bodied men on hunting expeditions to the far north at the height of the farming season? “There was a huge potential for ivory export,” says Smiarowski, “and they set up farms to support that.” Ivory drew them to Greenland, ivory kept them there, and their attachment to that toothy trove may be what eventually doomed them.

When the Norse arrived in Greenland, there were no locals to teach them how to live. “The Scandinavians had this remarkable ability to colonize these high-latitude islands,” says Andrew Dugmore. “You have to be able to hunt wild animals; you have to build up your livestock; you have to work hard to exist in these areas....This is about as far as you can push the farming system in the Northern Hemisphere.”

And push it they did. The growing season was short, and the land vulnerable to overgrazing. Ian Simpson has spent many seasons in Greenland studying soil layers where the Vikings farmed. The strata, he says, clearly show the impact of their arrival: The earliest layers are thinner, with less organic material, but within a generation or two the layers stabilized and the organic matter built up as the Norse farmwomen manured and improved their fields while the men were out hunting. “You can interpret that as being a sign of adaptation, of them getting used to the landscape and being able to read it a little better,” Simpson says.

For all their intrepidness, though, the Norse were far from self-sufficient, and imported grains, iron, wine and other essentials. Ivory was their currency. “Norse society in Greenland couldn’t survive without trade with Europe,” says Arneborg, “and that’s from day one.”

Then, in the 13th century, after three centuries, their world changed profoundly. First, the climate cooled because of the volcanic eruption in Indonesia. Sea ice increased, and so did ocean storms—ice cores from that period contain more salt from oceanic winds that blew over the ice sheet. Second, the market for walrus ivory collapsed, partly because Portugal and other countries started to open trade routes into sub-Saharan Africa, which brought elephant ivory to the European market. “The fashion for ivory began to wane,” says Dugmore, “and there was also the competition with elephant ivory, which was much better quality.” And finally, the Black Death devastated Europe. There is no evidence that the plague ever reached Greenland, but half the population of Norway—which was Greenland’s lifeline to the civilized world—perished.

The Norse probably could have survived any one of those calamities separately. After all, they remained in Greenland for at least a century after the climate changed, so the onset of colder conditions alone wasn’t enough to undo them. Moreover, they were still building new churches—like the one at Hvalsey—in the 14th century. But all three blows must have left them reeling. With nothing to exchange for European goods—and with fewer Europeans left—their way of life would have been impossible to maintain. The Greenland Vikings were essentially victims of globalization and a pandemic.

“If you consider the world today, many communities will face exposure to climate change,” says Dugmore. “They’ll also face issues of globalization. The really difficult bit is when you have exposure to both.”

So what was the endgame like in Greenland? Although archaeologists now agree that the Norse did about as well as any society could in confronting existential threats, they remain divided over how the Vikings’ last days played out. Some believe that the Norse, faced with the triple threat of economic collapse, pandemic and climate change, simply packed up and left. Others say the Norse, despite their adaptive ingenuity, met a far grimmer fate.

For McGovern, the answer is clear. “I think in the end this was a real tragedy. This was the loss of a small community, a thousand people maybe at the end. This was extinction.”

The Norse, he says, were especially vulnerable to sudden death at sea. Revised population estimates, based on more accurate tallies of the number of farms and graves, put the Norse Greenlanders at no more than 2,500 at their peak—less than half the conventional figure. Every spring and summer, nearly all the men would be far from home, hunting. As conditions for raising cattle worsened, the seal hunts would have been ever more vital—and more hazardous. Despite the decline of the ivory trade, the Norse apparently continued to hunt walrus until the very end. So a single storm at sea could have wiped out a substantial number of Greenland’s men—and by the 14th century the weather was increasingly stormy. “You see similar things happening at other places and other times,” McGovern says. “In 1881, there was a catastrophic storm when the Shetland fishing fleet was out in these little boats. In one afternoon about 80 percent of the men and boys of the Shetlands drowned. A whole bunch of little communities never recovered.”

Norse society itself comprised two very small communities: the Eastern and Western settlements. With such a sparse population, any loss—whether from death or emigration—would have placed an enormous strain on the survivors. “If there weren’t enough of them, the seal hunt would not be successful,” says Smiarowski. “And if it was not successful for a couple of years in a row, then it would be devastating.”

McGovern thinks a few people might have migrated out, but he rules out any sort of exodus. If Greenlanders had emigrated en masse to Iceland or Norway, surely there would have been a record of such an event. Both countries were literate societies, with a penchant for writing down important news. “If you had hundreds or a thousand people coming out of Greenland,” McGovern says, “someone would have noticed.”

Niels Lynnerup, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Copenhagen who has studied Viking burial sites in Greenland, isn’t so sure. “I think in Greenland it happened very gradually and undramatically,” he tells me as we sit in his office, beneath a poster of the Belgian cartoon character Tintin. “Maybe it’s the usual human story. People move to where there are resources. And they move away when something doesn’t work for them.” As for the silence of the historical record, he says, a gradual departure might not have attracted much attention.

The ruins themselves hint at an orderly departure. There is no evidence of conflict with the Inuit or of any intentional damage to homesteads. And aside from a gold ring found on the skeletal finger of a bishop at Gardar, and his narwhal-tusk staff, no items of real value have been found at any sites in Greenland. “When you abandon a small settlement, what do you take with you? The valuables, the family jewelry,” says Lynnerup. “You don’t leave your sword or your good metal knife....You don’t abandon Christ on his crucifix. You take that along. I’m sure the cathedral would have had some paraphernalia—cups, candelabras—which we know medieval churches have, but which have never been found in Greenland.”

Jette Arneborg and her colleagues found evidence of a tidy leave-taking at a Western Settlement homestead known as the Farm Beneath the Sands. The doors on all but one of the rooms had rotted away, and there were signs that abandoned sheep had entered those doorless rooms. But one room retained a door, and it was closed. “It was totally clean. No sheep had been in that room,” says Arneborg. For her, the implications are obvious. “They cleaned up, took what they wanted, and left. They even closed the doors.”

Perhaps the Norse could have toughed it out in Greenland by fully adopting the ways of the Inuit. But that would have meant a complete surrender of their identity. They were civilized Europeans—not skraelings, or wretches, as they called the Inuit. “Why didn’t the Norse just go native?” Lynnerup asks. “Why didn’t the Puritans just go native? But of course they didn’t. There was never any question of the Europeans who came to America becoming nomadic and living off buffalo.”

We do know that at least two people made it out of Greenland alive: Sigrid Bjornsdottir and Thorstein Olafsson, the couple who married at Hvalsey’s church. They eventually settled in Iceland, and in 1424, for reasons lost to history, they needed to provide letters and witnesses proving that they had been married in Greenland. Whether they were among a lucky few survivors or part of a larger immigrant community may remain unknown. But there’s a chance that Greenland’s Vikings never vanished, that their descendants are with us still.

161 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Why Did Greenland’s Vikings Vanish?

Newly discovered evidence is upending our understanding of how early settlers made a life on the island — and why they suddenly disappeared

By Tim Folger

Source: Smithsonian Magazine

March 2017

On the grassy slope of a fjord near the southernmost tip of Greenland stand the ruins of a church built by Viking settlers more than a century before Columbus sailed to the Americas. The thick granite-block walls remain intact, as do the 20-foot-high gables. The wooden roof, rafters and doors collapsed and rotted away long ago. Now sheep come and go at will, munching wild thyme where devout Norse Christian converts once knelt in prayer.

The Vikings called this fjord Hvalsey, which means “Whale Island” in Old Norse. It was here that Sigrid Bjornsdottir wed Thorstein Olafsson on Sunday, September 16, 1408. The couple had been sailing from Norway to Iceland when they were blown off course; they ended up settling in Greenland, which by then had been a Viking colony for some 400 years. Their marriage was mentioned in three letters written between 1409 and 1424, and was then recorded for posterity by medieval Icelandic scribes. Another record from the period noted that one person had been burned at the stake at Hvalsey for witchcraft.

But the documents are most remarkable—and baffling—for what they don’t contain: any hint of hardship or imminent catastrophe for the Viking settlers in Greenland, who’d been living at the very edge of the known world ever since a renegade Icelander named Erik the Red arrived in a fleet of 14 longships in 985. For those letters were the last anyone ever heard from the Norse Greenlanders.

They vanished from history.

“If there was trouble, we might reasonably have thought that there would be some mention of it,” says Ian Simpson, an archaeologist at the University of Stirling, in Scotland. But according to the letters, he says, “it was just an ordinary wedding in an orderly community.”

Europeans didn’t return to Greenland until the early 18th century. When they did, they found the ruins of the Viking settlements but no trace of the inhabitants. The fate of Greenland’s Vikings—who never numbered more than 2,500—has intrigued and confounded generations of archaeologists.

Those tough seafaring warriors came to one of the world’s most formidable environments and made it their home. And they didn’t just get by: They built manor houses and hundreds of farms; they imported stained glass; they raised sheep, goats and cattle; they traded furs, walrus-tusk ivory, live polar bears and other exotic arctic goods with Europe. “These guys were really out on the frontier,” says Andrew Dugmore, a geographer at the University of Edinburgh. “They’re not just there for a few years. They’re there for generations—for centuries.”

So what happened to them?

**********

Thomas McGovern used to think he knew. An archaeologist at Hunter College of the City University of New York, McGovern has spent more than 40 years piecing together the history of the Norse settlements in Greenland. With his heavy white beard and thick build, he could pass for a Viking chieftain, albeit a bespectacled one. Over Skype, here’s how he summarized what had until recently been the consensus view, which he helped establish: “Dumb Norsemen go into the north outside the range of their economy, mess up the environment and then they all die when it gets cold.”

Accordingly, the Vikings were not just dumb, they also had dumb luck: They discovered Greenland during a time known as the Medieval Warm Period, which lasted from about 900 to 1300. Sea ice decreased during those centuries, so sailing from Scandinavia to Greenland became less hazardous. Longer growing seasons made it feasible to graze cattle, sheep and goats in the meadows along sheltered fjords on Greenland’s southwest coast. In short, the Vikings simply transplanted their medieval European lifestyle to an uninhabited new land, theirs for the taking.

But eventually, the conventional narrative continues, they had problems. Overgrazing led to soil erosion. A lack of wood—Greenland has very few trees, mostly scrubby birch and willow in the southernmost fjords—prevented them from building new ships or repairing old ones. But the greatest challenge—and the coup de grâce—came when the climate began to cool, triggered by an event on the far side of the world.

In 1257, a volcano on the Indonesian island of Lombok erupted. Geologists rank it as the most powerful eruption of the last 7,000 years. Climate scientists have found its ashy signature in ice cores drilled in Antarctica and in Greenland’s vast ice sheet, which covers some 80 percent of the country. Sulfur ejected from the volcano into the stratosphere reflected solar energy back into space, cooling Earth’s climate. “It had a global impact,” McGovern says. “Europeans had a long period of famine”—like Scotland’s infamous “seven ill years” in the 1690s, but worse. “The onset was somewhere just after 1300 and continued into the 1320s, 1340s. It was pretty grim. A lot of people starving to death.”

Amid that calamity, so the story goes, Greenland’s Vikings—numbering 5,000 at their peak—never gave up their old ways. They failed to learn from the Inuit, who arrived in northern Greenland a century or two after the Vikings landed in the south. They kept their livestock, and when their animals starved, so did they. The more flexible Inuit, with a culture focused on hunting marine mammals, thrived.

That is what archaeologists believed until a few years ago. McGovern’s own PhD dissertation made the same arguments. Jared Diamond, the UCLA geographer, showcased the idea in Collapse, his 2005 best seller about environmental catastrophes. “The Norse were undone by the same social glue that had enabled them to master Greenland’s difficulties,” Diamond wrote. “The values to which people cling most stubbornly under inappropriate conditions are those values that were previously the source of their greatest triumphs over adversity.”

But over the last decade a radically different picture of Viking life in Greenland has started to emerge from the remains of the old settlements, and it has received scant coverage outside of academia. “It’s a good thing they can’t make you give your PhD back once you’ve got it,” McGovern jokes. He and the small community of scholars who study the Norse experience in Greenland no longer believe that the Vikings were ever so numerous, or heedlessly despoiled their new home, or failed to adapt when confronted with challenges that threatened them with annihilation.

“It’s a very different story from my dissertation,” says McGovern. “It’s scarier. You can do a lot of things right—you can be highly adaptive; you can be very flexible; you can be resilient—and you go extinct anyway.” And according to other archaeologists, the plot thickens even more: It may be that Greenland’s Vikings didn’t vanish, at least not all of them.

**********

Lush grass now covers most of what was once the most important Viking settlement in Greenland. Gardar, as the Norse called it, was the official residence of their bishop. A few foundation stones are all that remain of Gardar’s cathedral, the pride of Norse Greenland, with stained glass and a heavy bronze bell. Far more impressive now are the nearby ruins of an enormous barn. Vikings from Sweden to Greenland measured their status by the cattle they owned, and the Greenlanders spared no effort to protect their livestock. The barn’s Stonehenge-like partition and the thick turf and stone walls that sheltered prized animals during brutal winters have endured longer than Gardar’s most sacred architecture.

Gardar’s ruins occupy a small fenced-in field abutting the backyards of Igaliku, an Inuit sheep-farming community of about 30 brightly painted wooden houses overlooking a fjord backed by 5,000-foot-high snowcapped mountains. No roads run between towns in Greenland—planes and boats are the only options for traversing a coastline corrugated by innumerable fjords and glacial tongues. On an uncommonly warm and bright August afternoon, I caught a boat from Igaliku with a Slovenian photographer named Ciril Jazbec and rode a few miles southwest on Aniaaq fjord, a region Erik the Red must have known well. Late in the afternoon, with the arctic summer sun still high in the sky, we got off at a rocky beach where an Inuit farmer named Magnus Hansen was waiting for us in his pickup truck. After we loaded the truck with our backpacks and essential supplies requested by the archaeologists—a case of beer, two bottles of Scotch, a carton of menthol cigarettes and some tins of snuff—Hansen drove us to our destination: a Viking homestead being excavated by Konrad Smiarowski, one of McGovern’s doctoral students.