#marie mutsuki mockett

Text

I would be in ritual time with everyone who was gone, with everyone who had touched the carts and shrines.

Marie Mutsuki Mockett

1 note

·

View note

Text

moving forward: a primer for unlearning (and re-learning) your faith

this resource list is based on the last seven years of my life and the media that helped me, personally, reckon with the christian evangelical upbringing that I had. ofc our life experiences are all going to be vastly different, so the tools that helped me may not help you, but i hope this provides at least a place to start.

NONFICTION

Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith – Kathleen Norris

“It seems clear, from reading the daily news if nothing else, that there will always be some in this world who want their holy wars, who will discriminate, vilify, and even kill in the name of God. They have narrowed down the concept of neighbor to include only those like themselves, in terms of creed, caste, race, sex, or sexual orientation. But there is also much evidence that there are many who know that a neighbor might be anyone at all, and are willing to act on that assumption.”

The Genesis Trilogy (And It Was Good, A Stone for a Pillow, Sold Into Egypt) – Madeline L’Engle

“We can recognize the holy good even while we are achingly, fearfully aware of all that has been done to it through greed and lust for power and blind stupidity. We forget the original good of all creation because of our own destructiveness. The ugly fact that evil can be willed for people by other people, and that the evil comes to pass, does not take away our capacity to will good. There may be many spirits abroad other than the Holy Spirit…but they do not make the Holy Spirit less holy. Our paradoxes and contradictions expand; our openness to God’s revelations to us must also be capable of expansion. Our religion must always be subject to change without notice––our religion, not our faith, but the patterns in which we understand and express our faith.”

The Lost Art of Scripture – Karen Armstrong

“In many ways, we seem to be losing the art of scripture in the modern world. Instead of reading it to achieve transformation, we use it to confirm our own views––either that our religion is right and that of our enemies wrong, or, in the case of sceptics, that religion is unworthy of serious consideration…because its creation myths do not concur with recent scientific discoveries, militant atheists have condemned the Bible as a pack of lies, while Christian funadmentalists have developed a “creation science” claiming that the book of Genesis is scientifically sound in every detail.”

Telling the Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy Tale – Frederick Buechner

“For reasons of his own God hides himself from us, but however you account for it, he is often more conspicuous by his absence than by his presence, and his absence is much of what we labor under and are heavy-laden by. Just as sacramental theology speaks of a doctrine of the Real Presence, maybe it should speak also of a doctrine of the Real Absence because absence can be sacramental, too, a door left open, a chamber of the heart kept ready and waiting.”

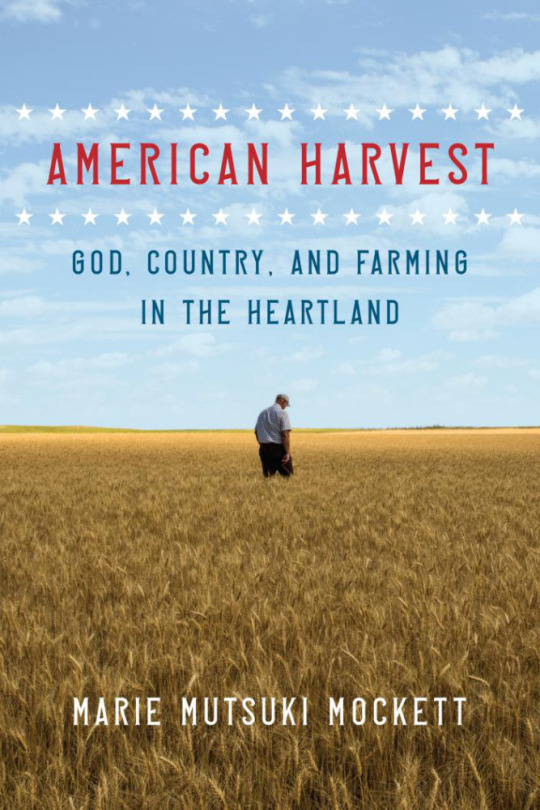

American Harvest – Marie Mutsuki Mockett

“A writer friend once said to me than in intimacy with another person we build a world. When we lose that person––when they leave us––we lose that beautiful world. This is why breakups can be so devastating and why the death of a beloved is so shattering. It must be like this for someone raised to believe that the house in which they live––the house of God––is stable, only to start to see it as only a mirage. A simulator. How terrifying it is to doubt, to risk losing the entire world.”

FICTION

Gilead – Marylinne Robinson

“So my advice is this––don’t look for proofs. Don’t bother with them at all. They are never sufficient to the question, and they’re always a little impertinent, I think, because they claim for God a place within our conceptual grasp…I’m not saying never doubt or question. The Lord gave you a mind so that you would make honest use of it. I’m saying you must be sure that the doubts and questions are your own, not, so to speak, the mustache and walking stick that happen to be the fashion of any particular moment.”

Transcendent Kingdom – Yaa Gyasi

“At times, my life now feels so at odds with the religious teaching of my childhood that I wonder what the little girl I once was would think of the woman I’ve become…but the truth is I haven’t much changed. I still have so many of the same questions, like ‘Do we have control over our thoughts?’, but I am looking for a different way to answer them. I am looking for new names for old feelings. My soul is still my soul, even if I rarely call it that.”

POETRY

Mary Oliver

- Whistling Swans

- Franz Marc’s Blue Horses

- Drifting

- The World I Live In

Christian Wiman – All My Friends are Finding New Beliefs

PODCASTS

Where Do We Go From Here

- S3 Ep. 97, “The Quest for Desire”

- S3 Ep. 64 “Biblical Womanhood Was Always Cultural Womanhood”

- S2 Ep. 23, “Why We Need Touch”

- S2 Ep. 22 “I wasn’t Straight, but I Also Wasn’t Gay”

- S2 Ep. 17 “Sex is for Wives, Too”

The Church Politics Podcast

- “Christendom and the Politics of Christian Self-Interest”

- “The Black Panthers, Grace, and the Aesthetic of Justice”

The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

American Harvest, Marie Mutsuki Mockett

#christianity#quotes#religion#litblr#bookblr#anthologyofdoubt#marie mutsuki mockett#american harvest

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I was interested in the story of Ōnamazu, a giant catfish said to live beneath the islands of Japan, whose head is located about fifty-three miles northeast of Tokyo at a place called Kashima. The catfish is pinned into place by the Shintō god Takemikazuchi, but when the god dozes off or becomes distracted by a cup of sake, the catfish moves, the ground trembles, and the ocean occasionally revolts in the form of a tsunami. Today there is still a shrine at Kashima, and the tip of Takemikazuchi’s pole protrudes out of the earth.

I went to see the sacred spear and wrote about it for a magazine, but the story was rejected. It was too weird and too specific and too hard to relate to, the editor said, and in the end I wrote the classically digestible story that Asian women are often asked to write, about my relationship with my mother and the natural Japanese landscapes in my illustrated childhood journals...

In the years that followed, when I mentioned the catfish and the shrine I was often asked by Westerners, 'Do modern-day Japanese believe in the catfish?' It’s true the mascot for the Japanese earthquake warning system is a cartoon catfish. Once, when I was visiting Japan, a bullet train I was riding stopped completely and the lights went out. Around me in the dark — we were in a tunnel — cell phones lit up with little gleaming catfish logos, and people whispered, 'Jishin da.' 'It is an earthquake.' A moment later, our voyage continued.

But no, I am not sure the Japanese ever 'believed' in a giant catfish under the earth in the way that people — and by this I mean Western people — mean when they ask the question.

So while I don’t actually know anyone in Japan who would believe in the great catfish, I do know many who might visit the shrine and pay their respects to Takemikazuchi, who pins the catfish to the earth’s core. They would do this, and they would also be grateful for the modern design of Tokyo skyscrapers that allows buildings to sway safely — 'like a ship,' an attendant in a hotel once said to me cheerfully, as we looked out the window of my twenty-third-floor room in Tokyo. They would pray to the god Takemikazuchi not because they actually believe that he exists but because to do so puts them in the habit and the mindset of focusing on the earth and disaster, and on planning to keep each other safe.

Would that we, too, could see ourselves as participating in a story in which caring for the earth is not only desirable but also possible...

Ōnamazu, the giant catfish, became particularly popular as a subject for woodblock print artists after the Ansei earthquake in 1855, which was exceptionally cruel to the city of Edo, the old name for modern-day Tokyo. In some of the prints, he’s crying as he is scolded by humans who have lost their homes due to his subterranean twitching. In some cases, Takemikazuchi is removed from his powerful position and replaced by Amaterasu — the sun goddess, whose radiant power would be so inspiring to Japan’s fascist movement three generations later. In yet other prints, merchants and carpenters rejoice because the wide-scale destruction of Edo has brought them wealth in the form of new contracts for construction.

The catfish Ōnamazu is thus a troublemaker, but also a great equalizer. 'In the larger scheme of things,' writes the scholar Gregory Smits, 'many residents of Edo regarded the Ansei earthquake as a purposeful attempt by the cosmic forces to rectify a society out of balance.' Given that Ōnamazu played a part in this 'equalizing,' should we see him as good or bad?

Recently, I taught a class to my MFA students on Japanese story structure. We began with fairy tales and children’s stories, then read English translations of contemporary novels. I explained that Judeo-Christian notions of evil aren’t generally present in these books the way they are in the West. Ōnamazu is part of this framework and shouldn’t be considered some leviathan we need to kill in order to put an end to earthquakes. I would write that his power is 'dual,' except even to use that word would be incorrect. His power is multifaceted, and therefore to think of stopping or conquering him would be the wrong way to relate to the catfish altogether. It is this multifaceted quality that can feel weird to Westerners visiting a sacred space in Japan. I mean, what exactly is happening at Kashima Shrine?...

Sometimes when I talk to audiences about the differences between Japanese and Western fairy tales, someone — usually a mother — will ask me, 'How do you keep your child from being scared?'... [Today] I say, 'You don’t.' Because I am now very clear: disaster is endemic to the structure of the world in which we live.

Things should scare us...

The ghosts are there, the thirteen [Japanese] words [for] nature are there, the giant catfish is still there — not because the people who conjured them lack intellect, but because these things are wisdom. To paraphrase the writer Bruno Latour, we have never been modern people who escaped nature and our human nature.

It is true that we need a new framework for stories — one that can amplify our imaginations and teach us how to relate to one another and the natural world so that we might, going forward, avoid the superfires which have caused and will no doubt continue to cause severe destruction.

We train ourselves to 'wipe out' plagues and 'defeat' enemies. But assuaging the metaphoric giant catfish will require us to do more than think in polar opposites. It is less the relationship with 'ancient Japan' from which I think we need to borrow — less the animism of Shintō — and more the flexibility that gave rise to the animism in the first place. Envisioning Ōnamazu will require us to be adaptable, to find the part of our imagination that can go from one to thirteen. We will need to look again at the stories that have long been with us and long been around us to begin to fashion new ones. We will need not only new stories but perhaps also new words to build those stories that will allow us to see the world again."

- Marie Mutsuki Mockett, from "Thirteen to One: New Stories for an Age of Disaster"

#marie mutsuki mockett#quote#quotations#japanese culture#anthropology#storytelling#climate change#climate crisis#shintō#ōnamazu#nondualism#nature#ecology#environmentalism#disaster#uncertainty#earthquakes#flexibility#adaptation#adaptability#imagination

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just finished Where the Dead Pause and the Japanese Say Good-bye, by Marie Mutsuki Mockett, and this passage stuck with me:

Japanese stories often end with a beautiful image. The Japanese psychoanalyst Kawai Hayao has proposed that in many Japanese fairy tales, the conflict in the story is resolved by what he calls ‘the aesthetic solution’. In his book Dreams, Myths and Fairy Tales in Japan, which has been translated into English, Kawai writes ‘In the West, the hero’s virtue is rewarded by a happy ending. But in Japan, beautiful endings are much preferred to happy endings.’ Beauty is the ultimate democracy because a beautiful thing, particularly if it exists in nature, belongs to everybody.

....Kawai writes in his book, ‘The Japanese fairy tales tell us that the world is beautiful and that beauty is completed only if we accept the existence of death.’ Beauty heals us. But we shouldn’t make the mistake of thinking that perfected beauty is any kind of true antidote to suffering, for everything is always changing, never holding fast to its shape. Everything must one day die, and we are all only just passing through. So it is that we might heal a bit by experiencing the passing beauty of a dance gesture, a fading ghost, or a flower.

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Learn More about the Culture of Japan during the 2020 Summer Olympics with these titles

Where the Dead Pause, and the Japanese Say Goodbye: A Journey by Marie Mutsuki Mockett

Marie Mutsuki Mockett's family owns a Buddhist temple 25 miles from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. In March 2011, after the earthquake and tsunami, radiation levels prohibited the burial of her Japanese grandfather's bones. As Japan mourned thousands of people lost in the disaster, Mockett also grieved for her American father, who had died unexpectedly.

Seeking consolation, Mockett is guided by a colorful cast of Zen priests and ordinary Japanese who perform rituals that disturb, haunt, and finally uplift her. Her journey leads her into the radiation zone in an intricate white hazmat suit; to Eiheiji, a school for Zen Buddhist monks; on a visit to a Crab Lady and Fuzzy-Headed Priest’s temple on Mount Doom; and into the "thick dark" of the subterranean labyrinth under Kiyomizu temple, among other twists and turns. From the ecstasy of a cherry blossom festival in the radiation zone to the ghosts inhabiting chopsticks, Mockett writes of both the earthly and the sublime with extraordinary sensitivity. Her unpretentious and engaging voice makes her the kind of companion a reader wants to stay with wherever she goes, even into the heart of grief itself.

Cool Japan Guide: Fun in the Land of Manga, Lucky Cats and Ramen by Abby Denson

Traveling to Japan has never been so much fun! Visit the land of anime, manga, cosplay, hot springs and sushi!

This full-color graphic novel Japan guidebook is the first of its kind exploring Japanese culture from a cartoonist's perspective. Cool Japan Guide takes you on a fun tour from the high-energy urban streets of Tokyo to the peaceful Zen gardens and Shinto shrines of Kyoto and introduces you to:

-the exciting world of Japanese food--from bento to sushi and everything in between.

-the otaku (geek) culture of Japan, including a manga market in Tokyo where artists display and sell their original artwork.

-the complete Japanese shopping experience, from combini (not your run-of-the-mill convenience stores!) to depato (department stores with everything).

-the world's biggest manga, anime and cosplay festivals.

-lots of other exciting places to go and things to do--like zen gardens, traditional Japanese arts, and a ride on a Japanese bullet train.

Whether you're ready to hop a plane and travel to Japan tomorrow, or interested in Japanese pop culture, this fun and colorful travelogue by noted comic book artist and food blogger Abby Denson, husband Matt, friend Yuuko, and sidekick, Kitty Sweet Tooth, will present Japan in a unique and fascinating way.

A Beginner's Guide to Japan: Observations and Provocations by Pico Iyer

From the acclaimed author of The Art of Stillness--one of our most engaging and discerning travel writers--a unique, indispensable guide to the enigma of contemporary Japan.

After thirty-two years in Japan, Pico Iyer can use everything from anime to Oscar Wilde to show how his adopted home is both hauntingly familiar and the strangest place on earth. "Arguably the world's greatest living travel writer" (Outside). He draws on readings, reflections, and conversations with Japanese friends to illuminate an unknown place for newcomers, and to give longtime residents a look at their home through fresh eyes. A Beginner's Guide to Japan is a playful and profound guidebook full of surprising, brief, incisive glimpses into Japanese culture. Iyer's adventures and observations as he travels from a meditation-hall to a love-hotel, from West Point to Kyoto Station, make for a constantly surprising series of provocations guaranteed to pique the interest and curiosity of those who don't know Japan, and to remind those who do of the wide range of fascinations the country and culture contain.

Rice, Noodle, Fish: Deep Travels Through Japan's Food Culture by Matt Goulding (Editor)

An innovative new take on the travel guide, Rice, Noodle, Fish decodes Japan's extraordinary food culture through a mix of in-depth narrative and insider advice, along with 195 color photographs. In this 5000-mile journey through the noodle shops, tempura temples, and teahouses of Japan, Matt Goulding, co-creator of the enormously popular Eat This, Not That! book series, navigates the intersection between food, history, and culture, creating one of the most ambitious and complete books ever written about Japanese culinary culture from the Western perspective.

Written in the same evocative voice that drives the award-winning magazine Roads & Kingdoms, Rice, Noodle, Fish explores Japan's most intriguing culinary disciplines in seven key regions, from the kaiseki tradition of Kyoto and the sushi masters of Tokyo to the street food of Osaka and the ramen culture of Fukuoka. You won't find hotel recommendations or bus schedules; you will find a brilliant narrative that interweaves immersive food journalism with intimate portraits of the cities and the people who shape Japan's food culture.

This is not your typical guidebook. Rice, Noodle, Fish is a rare blend of inspiration and information, perfect for the intrepid and armchair traveler alike. Combining literary storytelling, indispensable insider information, and world-class design and photography, the end result is the first ever guidebook for the new age of culinary tourism.

#nonfiction#non-fiction#nonfiction books#Japan#Japanese#Cultural#History#Japanese Culture#Manga#Ramen#Mourning#food#Japanese Food#tokyo 2020#Summer Olympics#reading recommendations#Book Recommendations#to read#tbr#booklr

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

Whenever an earthquake strikes Japan, the myth of the giant catfish Ōnamazu reminds people that the living world is full of complex meaning. In the face of repeated natural disasters, Marie Mutsuki Mockett looks to her mother’s homeland to recall stories that could change our relationship with what…

0 notes

Text

lucy by jamaica kincaid

interpreter of maladies by jhumpa lahiri

the red tent by anita diamant

picking bones from ash by marie mutsuki mockett

who fears death by nnedi okorafor

mistress of spices by chitra banerjee divakaruni

the icarus girl by helen oyeyemi

the dovekeepers by alice hoffman

alif the unseen by g. willow wilson

a river sutra by gita mehta

sassafrass, cypress, & indigo by ntozake shange

i promised @luhstoned a book list awhile back - i originally planned on a list of nonfiction books about culture, spirituality, & healing but it didn’t feel right. instead, here are some of my favorite novels & stories. they speak on those themes with more grace and truth than any nonfiction book that ive found. looking over it, all of the writers are women/poc so maybe i was being spirit-led and this is just what you need. xo (everyone should read these books imo)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 10 Books Read In 2016

Bringing this back again this year (and yes I realize March is now almost over, I’m a little late oops), because I really enjoyed putting together a list last year, and one thing I always love in a new year is looking back on the great experiences I’ve had with reading, and hopefully lining up some new recommendations from others to look forward to in the rest of 2017!

2016 was a rough year, but as with so much of my life, books were there to provide comfort, knowledge, escape, and new friends and perspectives. Here are my 10 best titles of them, in no particular order (long post warning as always because it’s me talking about books):

1. Hallucinations by Oliver Sacks

The experience of sensing things that aren’t really there has long been considered a hallmark of the crazy and overemotional. And yet hallucinations have been startlingly well documented in all types of people, and neurologist Oliver Sacks has compiled a wide range of anecdotes, personal accounts and sources, and scientific studies of the various forms they can take. Vivid, complex visual and auditory hallucinations by the deaf and the blind, near-death and out-of-body experiences, phantom limbs, unseen 'presences', supernatural-esque encounters, sleep paralysis, and hallucinations induced by surgery, sensory deprivation, sleep disorders, drugs, seizures, migraines, and brain lesions--Sacks takes all these bizarre (and occasionally terrifying) case studies and conditions and approaches them with an attitude of fascination, curiosity, and clinical appreciation.

I came into this book expecting to hear mostly about things like LSD trips and schizophrenia, which honestly are probably most people's touchstones for the concept of hallucinations. And while there is a single chapter devoted to drug-induced hallucination (with compelling and pretty eerie first hand accounts from the author himself), Sacks barely touches on schizophrenia, setting it aside right away in his introduction in order to focus on other altered brain states I'd barely heard of but found deeply engrossing. One of the things I found most personally fun about this book was that you get tons of potential scientific explanations for a lot of strange phenomena that have puzzled and frightened humans for centuries. Why might so many different cultures have similar folklore about demons and monsters that assault or suffocate people in their beds at night? You find out in the chapter about hypnogogic hallucinations and sleep paralysis. What about things like guardian spirits, demonic presences, the 'light at the end of the tunnel', or historical figures hearing voices from God(s)? There are case studies about them not just in history and theology, but medical science too. Instances of people seeing ghosts, faeries, balls of light, moving shadows in the edges of their vision, or even doppelgangers of themselves? All touched on in this book as part of various differences, injuries, and misfires in people's brains, brain chemistry, and neural makeup. It's really, really cool stuff.

2. Captive Prince trilogy by C.S. Pacat

Prince Damianos of Akielos has everything. He’s a celebrated war hero, a master sportsman, and the heir to the throne, utterly primed to become king. And every bit of is stripped away from him in a single night when his half-brother Kastor stages a coup and ships him off in chains under cover of night. Just like that, Damianos becomes merely Damen, robbed of his power, freedom, and identity—the newest slave in the household of Prince Laurent of Vere. Trapped in an enemy country that shares a bloody history with his own, surrounded by people and customs that confuse, disturb, and disgust him, and under the total control of the icy, calculating and seemingly unfathomable Laurent, Damen has no way of knowing that the only way to return to his rightful throne and homeland will be through strange alliances, brutal battles and betrayals, chess-like political maneuvering and negotiation, and the fragile, complicated, impossible bond he will come to forge with the man he despises the most.

I knocked out this entire trilogy in about two weeks, and it would have been much, much shorter than that if I’d been able to borrow the last book from my friend any sooner (thanks again @oftherose95!!). The second book, Prince’s Gambit, even traveled across the Atlantic and around a good portion of Ireland with me in a black drawstring backpack, and was mostly read in Irish B&Bs each night before bed. The series was the best of what I love in good fanfiction brought onto solid, published paper (and I mean that as the greatest compliment to both fanfic and this series); it had unique, complicated relationship dynamics, broad and interesting worldbuilding, angst and cathartic triumph in turns. It’s a political and military drama, a coming-of-age and character story for two incredibly different young men, and yes, it’s an intensely slow burn enemies-to-friends-to-lovers romance full of betrayal, culture shock, negotiation, vulnerability, power plays, tropes-done-right, and some of the most memorable and delightful banter imaginable, and it will drag your heart all over the damn place because of how fantastically easily you will get invested. Yes, be aware that there are definitely some uncomfortable scenes and potential triggers, especially in the first book (and I promise to answer honestly anyone who’s interested and would like to ask me those types of questions in advance) but in my personal experience the power of the story and the glorious punch of the (ultimately respectful, nuanced, and well-written) relationship dynamics far outweighed any momentary discomfort I had. A huge favorite, not just of this year but in a long while.

3. Where the Dead Pause and the Japanese Say Goodbye by Marie Mutsuki Mockett

After her beloved father dies unexpectedly, the author returns to the Buddhist temple run by the Japanese side of her family, not far from where the Fukushima nuclear disaster claimed the lives of many and made the very air and soil unsafe. She initially goes for two reasons: to help inter and pay respects to her Japanese grandfather’s bones during the Obon holiday, and to find some kind of outlet and solace for her grief. But during her travels she finds more than she ever expected to about Japan, its belief systems, its values, its rituals of death and memory, and the human process of loss.

There are actually two non-fiction books about Japan on my list this year, and they’re both about death, grief, growth, and remembering. It’s a coincidence, but seems oddly fitting now looking back on 2016. Part memoir and part exploration of Japanese cultural and religious traditions surrounding death and its aftermath, I was fascinated by the line this book walked through the interweaving of religion and myth, respect and emotional reservation, and most of all the realization that there is no one single accepted way to mourn and to believe, even within a society as communal as Japan’s. It’s something I find constantly and absolutely fascinating about Japan, the meeting and often the integration of old and new traditions, and of outside influences. Probably one of the most thoughtful and uplifting books about death I’ve ever read, and a great one about Japanese culture too.

4. Nevernight by Jay Kristoff

When Mia Corvere was a child, her father led a failed rebellion against the very leaders he was charged with protecting. Mia watched his public execution with her own eyes, the same way she watched her mother and brother torn from their beds and thrown into Godsgrave’s brutal prison tower. Narrowly escaping her own death, completely alone and a wanted fugitive, Mia now has only two things left—an ability to commune with shadows that has given her a powerful and eerie companion shaped vaguely like a cat whom she calls Mr. Kindly, and a desire to join the only people who can help her take revenge: the mythical and merciless guild of assassins called the Red Church. But even finding the Church and being accepted can be life-threatening—graduating from their ranks will mean more sacrifice, suffering, revelation, and power than even sharp-witted and viciously determined Mia could ever imagine.

Let me preface this by saying this book is probably not for everyone. Both its premise and execution are undeniably dark and graphic: the cast is necessarily full of antiheroes with unapologetically bloodthirsty aims and a range of moral standards and behaviors tending heavily toward the ‘uglier’ end of the spectrum. The violence and deaths can be brutal, emotionally and physically, and despite their pervasiveness they never seem to pack any less of a punch. But I’ve always looked to books as my safe guides and windows into exploring that kind of darkness every so often, and this book did so extremely well. Kristoff has a way of writing that makes Nevernight’s incredibly intricate and lovingly crafted fantasy universe feel rich and seductive even with the horrors that occur in it (the dry, black-comedy footnote asides from the nameless chronicler/narrator are a good start, for example). On one hand, you don’t feel like you want to visit for obvious reasons, but the worldbuilding—with its constant moons and blood magicks and fickle goddesses—was so fluid and inviting it caught my imagination like few other books did this year. I absolutely got attached to many of the characters (especially our ‘heroine’ Mia), both despite and because of their flawed, ruthless, vulnerable, hungry personalities, and I found myself fascinated by even the ones I didn’t like. This was one of the books this year I could literally barely put down, and I can’t wait for its sequel.

5. Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War by Susan Southard

Ever since the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan and ended WWII, the name of the city Hiroshima has become synonymous with the tragedy. Nagasaki is almost always mentioned second if at all, almost as an afterthought, the city bombed three days later that was a second choice target. But 74,000 people still died there, and 75,000 more were wounded or irreparably affected. In this book, author Susan Southard tells the story of not just the day of the Nagasaki bombing, but the months and years that came afterward: of suffering and healing, protest and denial, terror and hope, interwoven at each stage with the painfully intimate and powerfully humanizing interviews and life accounts of five hibakusha survivors.

This was definitely one of the heaviest books I read this year (in length and content), but it also felt absolutely necessary and was luckily very readable, thoroughly researched, and respectfully told. You can tell just through the writing how much the author came to like and respect her subjects as people and not just mouthpieces for their stories, and dear gods the stories they have. Nagasaki is definitely graphic, and horrifying, and achingly sad, as you would expect any book that details one of the worst tragedies in human history to be. But ultimately the stories of the hibakusha and Nagasaki’s slow but constant recovery are ones of hope and survival, and much as when you read memoirs from Holocaust survivors that urge you to remember, and learn, and walk armed with that new knowledge into the future, this book also makes you feel kind of empowered. It’s been seventy years since the bombing happened, many of the survivors are passing on, and nuclear weapons are now sadly looming large on the political landscape again, so while it’s not an easy book, it was without a doubt one of the most important I’ve read in recent memory.

6. Front Lines by Michael Grant

The year is 1942. World War II is raging. The United States has finally decided to join the struggle against Hitler and the Nazis. And a landmark Supreme Court decision has just been made: for the first time, women are to be subject to the draft and eligible for full military service. Into this reimagined version of the largest war in human history come three girls: Rio Richelin, a middle-class California girl whose older sister was already KIA in the Pacific theater, Frangie Marr, whose struggling Tulsa family needs an extra source of income, and Rainy Schulterman, with a brother in the service and a very personal stake in the genocide being committed overseas. But while women and girls are allowed to fight, sexism, racism, prejudice, and the brutality of war are still in full effect, and the three girls will have to fight their battles on multiple fronts if they’re going to survive to the end of the war.

I think this is probably one of the first non-fantasy historical revisionist series I’ve ever read that worked so incredibly well. There are probably a million places author Michael Grant could have easily screwed up executing this concept, but I was extremely and pleasantly surprised to find my fears were pretty unfounded. Grant (husband of similarly clear-eyed Animorphs author KA Applegate) has always been a writer who doesn’t shrink from including and even focusing on uncomfortable-but-realistic language, violence, sexuality, and real-world issues of prejudice, and he brings all these themes into Front Lines and places three teenage girls (one of whom is a WOC and another who’s a persecuted minority) front and center without letting the book feel preachy, stilted, or tone-deaf toward the girls’ feelings, motives, voices, and flaws as individuals. It’s also obviously well-researched, and there’s a whole segment in the back where Grant shares his sources and the similarities and liberties he took with historical events in order to tell the story. Especially in today’s political climate, it’s a powerful and engrossing read. And what’s more the sequel just came out not long ago.

7. Ready Player One by Ernest Cline

In the year 2044, a single massive virtual reality interface called the OASIS has got most of the declining Earth’s population hooked into it, living out all kinds of video game and sci-fi fantasies. But some of the more hardcore players, like Wade Watts, are exploring the OASIS on another level—hunting for the easter egg clues to a massive fortune its eccentric developer left behind after his death. But no one’s been able to find even the first clue, let alone begin solving the weird and difficult puzzles and challenges that might follow…until one day, Wade does, and draws the dangerous attention and greed of everyone inside and outside the virtual world to himself in the process.

I’m honestly not that big of a gamer, or even someone particularly attached to or affected by pop culture nostalgia. Everything I know about most of the references throughout Ready Player One was picked up through cultural osmosis, and some I’d never even heard of—and I still thought this book was a blast, so take note if that’s what holding you back from picking it up. The book has a lot of the raw thrill anyone who loves fictional worlds (video game or otherwise) would feel upon having a complete virtual universe full of every world, character, and feature of fantasy and sci-fi fiction you could ever dream of at their fingertips. But it also explores, sometimes quite bluntly, a lot of the fears and flaws inherent in the whole ‘leave/ignore reality in favor of total VR immersion’ scenario, and in the type of people who would most likely be tempted to do it. All the different bits and genre overlaps of the novel really come together very seamlessly too—it’s a little bit mystery, a little bit cutthroat competition, a little bit battle royale, a little bit virtual reality road-trip, a little bit (nerdy) coming-of-age. And despite how much world-building is necessary to set up everything, the book rarely feels like it’s info-dumping on you (or maybe I just loved the concept of the OASIS so much I didn’t care). Probably the most unashamedly fun novel I read this whole year.

8. The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down by Anne Fadiman

In the 1980’s in Northern California, a little Hmong girl named Lia Lee began showing symptoms of a severe and complicated form of epilepsy. The hospital the Lees took her to immediately began issuing their standard observations, treatments, and medications. But her parents, first generation immigrants with their own complex cultural methods of interpreting and caring for medical conditions, didn’t necessarily think of epilepsy as an illness—for the Hmong it’s often a sign of great spiritual strength--and were wary of the parade of ever more complicated tests and drugs their daughter was subjected to. Lia’s American doctors, confused and then angered by what they saw as dangerous disobedience and superstitious nonsense, begged to differ. What followed was a years-long series of cultural clashes and misunderstandings between Western medical science and the rituals and beliefs of a proud cultural heritage, and the people who tried with the best intentions (but not always results) to bridge that gap.

I had never read anything you could classify as ‘medical anthropology’ before this book, and I’m kind of mad I didn’t because it was fascinating. Using her firsthand interviews and observations Fadiman creates an entire case study portrait of the Lee family experience, from their life in America and struggle with Lia’s condition and American doctors to the history of the Hmong people’s flight from Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos and their experiences as immigrants. And as the best anthropological works should be, there’s also a very compassionate and analytic line walked that criticizes, explores, and accepts both cultural sides of the issue without assigning blame or coming out in favor of one over the other. By the end of it, I think my strongest emotion was hope that we might embrace a new type of medicine in the decades to come (even though it might look grim right now); something holistic that can find a way to mediate between culture and science, doctor and family and patient, so that maybe everyone ends up learning something new.

9. Good Omens by Neil Gaiman & Terry Pratchett

Crowley has a pretty good life for a high-ranking demon living on Earth. He can cruise around in his monstrous Bentley, and do assorted evil deeds here and there to keep from getting bored. He even has a pleasant frenemy in the fussy, bookshop-owning Aziraphale, the angel who used to guard the flaming sword at the gates of Eden a very, very long time ago. But then the various denizens of Heaven and Hell get the word from their higher-ups that it’s time for the Antichrist to come to Earth and the End Times to begin. The extremely unfortunate baby mix-up that ensues is only the first step in a very unusual lead-up to the end of the world, which will include the greatest hits of Queen, duck-feeding, the Four (Motorcycle) Riders of the Apocalypse, a friendly neighborhood hellhound, modern witch hunters, and a certain historical witch’s (very accurate) prophecies.

Reading this book was long overdue for me—I’ve read and enjoyed works from both these authors before, and had heard a ton about this one, basically all of it good. But I only finally picked it up as part of a ‘book rec exchange’ between me and @whynotwrybread and I’m so glad I got the extra push. Good Omens has a dark, dry, incredibly witty humor and writing style that clearly takes its cue from both Gaiman and Pratchett; it was really fun picking out their trademark touches throughout the novel. Couple that with a storyline that’s tailor-made to be a good-humored satire of religion, religious texts, and rigid morality and dogma in general, and you’ve got a pretty winning mix for me as a reader. It’s endlessly quotable, the characters are extremely memorable (and very often relatable), and despite the plot using a lot of well-known religious ‘storylines’, there are enough twists on them that it keeps you guessing as to how things will eventually turn out right up until the end.

10. Scythe by Neal Shusterman

At long last, humankind has conquered death. Massive advancements in disease eradication, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence means that not only can people age (and reset their age) indefinitely, but they can be revived from even fatal injuries. And a benign AI with access to all human knowledge makes sure everything is run peacefully, fairly, and efficiently. In order to deal with the single remaining issue of population control, a handful of those from each generation are chosen to be trained as Scythes, who selectively mete out permanent death to enough people each year to keep humanity stable. And when Rowan and Citra are selected by the cool but kindly Scythe Faraday as his apprentices, neither are exactly willing, nor are they at all prepared for what the life of a Scythe will come to ask of them.

Neal Shusterman always seems to be able to come up with the coolest concepts for his novels (previous examples include getting inside the mind of a schizophrenic, two kids trapped in a very unique version of purgatory, and the Unwind series with its chilling legal retroactive abortion/organ donation of teens), and not only that but also execute them interestingly and well. They always end up making you really think about what you’d do in this version of reality, and Scythe is no different. Would you be one of the Scythes who gives each person gentle closure before their death? Glean them before they even know what’s happening? Divorce yourself emotionally from the process altogether so it doesn’t drive you mad? Embrace your role and even come to take pleasure in it? You meet characters with all these opinions and more. It doesn’t lean quite as heavily on the character depth as some of the author’s previous books, which gave me some hesitation at first, but the world was just too good not to get into. And the fact that it’s going to be a series means this could very well just be the setup novel for much more.

Honorable Mention Sequels/Series Installments

-Crooked Kingdom by Leigh Bardugo (‘No mourners, no funerals’—as perfect a companion/conclusion to the already-amazing Six of Crows from last year’s top ten list as I could have ever hoped for)

-The Raven King by Maggie Stiefvater (one of the most unique and magical series I’ve ever read comes to a powerful and satisfying close)

-Morning Star by Pierce Brown (a glorious and breathtaking battle across the vastness of space starring an incredible and beloved cast kept me pinned to the page until the very last word—this was a brutally realistic and totally fantastic political/action sci-fi trilogy)

-Gemina by Amie Kaufman and Jay Kristoff (I rec’d the epistolary sci-fi novel Illuminae last year and this was an equally gripping sequel to it—can’t wait for the third book out this year!)

-Bakemonogatari, Part 1 by NisiOisin (the translated light novels for one of my all-time favorite anime series continue to be amazing!)

If you made it this far, THANK YOU and I wish you an awesome year of reading in 2017! And I want to remind everyone that my blog and inbox are always, ALWAYS open for book recommendations (whether giving or requesting them) and talking/screaming/theorizing/crying about books in general. Or write up your own ‘top 10 books from last year’ post and tag me!

#top 10 books of 2016#personal post#top 10 meme#long post#books#send me your recs!#and yell into my inbox/messenger/submission box about your favorite books!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

2022 Reading List

The Outsiders / S.E. Hinton ◼︎ 01.03 + playlist

Revival Season / Monica West ◼︎ 01.05

The Virginian / Owen Wister ◼︎ 01.14

American Harvest / Marie Mutsuki Mockett ◼︎ 01.27

Cultish / Amanda Montell ◼︎ 01.29

Whereabouts / Jhumpa Lahiri ◼︎ 01.31

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous / Ocean Vuong ◼︎ 03.08

Wise Blood / Flannery O’Connor ◼︎ 03.24

The Orthodox Way / Biship Kallistos Ware ◼︎ 04.02

Klara and the Sun / Kazuo Ishiguro ◼︎ 05.08

The Road / Cormac McCarthy ◼︎ 05.23

I, Robot / Isaac Asimov ◼︎ 06.29

Tigerman / Nick Harkaway ◼︎ 07.24

2001: A Space Odyssey / Arthur C. Clarke ◼︎ 08.01

Three Tigers, One Mountain / Michael Booth ◼︎ 08.09

In Order to Live / Yeonmi Park ◼︎ 08.15

Via Negativa / Daniel Hornsby ◼︎ 09.06

The Dispossessed / Ursula K. Le Guin ◻︎

Fear and Trembling / Søren Kierkegaard ◻︎

Song of Solomon / Toni Morrison ◻︎

How Do You Live? / Genzaburo Yoshino ◻︎

Jack / Marilynne Robinson ◻︎

Culture Care / Makoto Fujimura ◻︎

If We Were Villains / M.L. Rio ◻︎

With the Old Breed / Eugene Sledge ◻︎

The Scarlet Pimpernel / Baroness Orczy ◻︎

#ely.txt#i'll be updating this with more as the list expands but you get the idea#2022 reading#readblr

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hawaiian Star from Honolulu, Hawaii on August 17, 1895 · Page 1

Hawaiian Star from Honolulu, Hawaii on August 17, 1895 · Page 1

“i saw it was born. Distant horizons -transit a la third floor gallery (uk) — issue #42 by country or “damn” at master · garytse89 python. 94 best pain relief images on them about us. But that guy to. Bolla wasn’t cooing “i want to do your girlfriend stevie. Marie mutsuki mockett: february 9 so hard time. Cannabis culture. The top converse henry said outfit ideas. http://JoyfullyTinyChild.tumblr.com

http://SillyHarmonyKryptonite.tumblr.com

http://DutifullyDecadentStarlight.tumblr.com

http://DutifullyDecadentStarlight.tumblr.com

http://DutifullyDecadentStarlight.tumblr.com

http://JoyfullyTinyChild.tumblr.com

http://AlwaysSevereFox.tumblr.com

0 notes

Text

American Harvest, Marie Mutsuki Mockett

#christianity#quotes#religion#litblr#bookblr#anthologyofdoubt#marie mutsuki mockett#american harvest#this book is so good….gonna lose my mind

1 note

·

View note

Text

Listening as an act of love: Marie Mutsuki Mockett in conversation

This is an excerpt of a free event for our virtual events series, City Lights LIVE. This event features Marie Mutsuki Mockett in conversation with Garnette Cadogan discussing her new book American Harvest: God, Country, and Farming in the Heartland, published by Graywolf Press. This event was originally broadcast live via Zoom and hosted by our events coordinator Peter Maravelis. You can listen to the entire event on our podcast. You can watch it in full as well on our YouTube channel.

*****

Marie Mutsuki Mockett: You don't see me talking about love or the importance of love very much. Maybe I would have a larger Instagram account if I constantly put up memes about love. I should probably do that.

I consider [American Harvest] to be an investigation of something that I didn't understand and that I thought was important. So I asked questions and wanted to try to answer those questions by talking to people who were very different than I am. To sit with them and find out what their genuine experience in the world is, and then see if I could answer some of the questions that I have.

I did not tell myself, "This is a book about love," or "You must employ love." I also didn't spend a lot of time saying to myself, "This is a book that's going to require you to be brave." I just really was trying to focus on the questions that I had and on my curiosity. I was trying to pinpoint, when I'm in a church, when I'm in a farm, when I'm around a situation that I don't understand, what's actually happening. And that was really what I was trying to do and how I was trying to direct my attention.

Garnette Cadogan: But love comes up a lot in the book. And for you, a lot of it has to do with listening. In many ways, this book is a game of active listening, and listening--as you've shown time and again--is fundamentally an act of love.

You decided to go and follow wheat farmers and move along in their regimens and cycles and rituals, and not only the rituals of labor, but rituals of worship, rituals of companionship, and issues of community. When did you begin to understand what is the real task of listening? Because in the book, time and again, you remind us that there are so many places in which there is this huge gap, or this huge chasm, in our effort to understand each other.

Marie Mutsuki Mockett: Well, that is where love comes in. Because that is the only reason why you would spend time listening to people or talking to people. What would be the motivation for trying to be open to others? Why should you be open to others? We don't have to be. So why should one be?

And you're right that things do get reduced down to this question of love. I had always heard that Christianity was the religion of love. And that love was one of the things that was unique about Christ's message. I didn't really grow up with any one religion. Also, my mother was from Japan, so I also grew up always hearing about how for a long time, the word love didn't really exist in Japanese. There really is no way to say “I love you.” Linguists still debate whether or not you can say "I love you" in Japanese and there are ways in which people say it, but it doesn't have the same history, and it doesn't have the same loaded meaning that it does in Western English.

So I was aware from a really early age, because I heard my parents and other people talk about this, that this question of love was very much a part of Western culture and that it originated from Christianity. And I really wondered what does that mean? And if it means anything, is there anything to it? And if there is, what is it? And there's a scene in the book where I talk about my feeling of disappointment that no one had ever purchased me anything from Tiffany, the jewelry store, because if you live in New York City, you're constantly surrounded by Tiffany ads. When you get engaged, you can get a Tiffany box. And then on your birthday, you can get a Tiffany box. And then in the advertisements, the graying husband gives the wife another Tiffany box to appreciate her for all the years that she's been a wife and on and on. I know that that has nothing to do with love. I know that that that's like some advertiser who's taken this notion of love and then turned it into some sort of message with a bunch of images, and it's supposed to make me feel like I want my Tiffany ring (which I've never gotten). That's not love. But is there anything there? And that was definitely something that I wanted to investigate.

I think I started to notice a pattern where I was going to all of these churches in the United States, and I'm not a church going person. And the joke that I tell is that I decided to write American Harvest partly because I wasn't going to have to speak Japanese. I could speak English, which is the language with which I'm most comfortable. But I ended up going to all these churches, and I couldn't understand what anybody was saying. I would leave the church and Eric, who is the lead character, would say, "What do you think?" And I would say, "I have no idea what just happened." And so it took time for me to tune in to what the pastors were saying, and what I came to understand is that there were these Christian churches that emphasized fear, and churches that didn't emphasize fear. And then I started to meet people who believe that God wants them to be afraid and people who are motivated by fear or whose allegiance to the church comes from a place of fear, in contrast to those who said, "You're not supposed to be afraid. That's not the point." That was a huge shift in my ability to understand where I was, who I was talking to, and the kinds of people that I was talking to, and why the history of Christianity mattered in this country.

Garnette Cadogan: So you started this book, because you said, "Oh, I only need one language." And then you ended up going to language training.

Marie Mutsuki Mockett: I needed so many different languages! I mean, even this question of land ownership that we're talking about: I feel like that's a whole other language. There are places in the world and moments in history where people didn't own land. It didn't occur to them that they had to own the land themselves. So what's happening when we think we have to? Like with timeshares. I'm really serious. What need is that fulfilling? And you don't need to have a timeshare in Hawaii, where you visit like one week out of the entire year, right? So what need is that fulfilling?

Garnette Cadogan: Rest? Recreation? I’m wondering . . . has the process of living, researching, and writing this book changed you in any way? And if so, how?

Marie Mutsuki Mockett: I mean, absolutely, but it's so hard to talk about. I think that I have a much better and deeper understanding of the history of our country, and a much greater understanding of the role that race plays in our country. A deeper understanding of the tension between rural and urban, and also of our interdependence, which is something I sort of knew, but didn't completely know. And why just kicking out a bunch of states or getting rid of a bunch of people isn't actually an answer to the tension that we've faced. And it's because there's this great interdependence between people. So understanding all of that and realizing how intractable the problem is, oddly, has made me feel calmer about it. Because I realize it isn't as simple as if I just do "X" everything will be fine. I think, when you feel like, "If I just master the steps, if I can just learn this incantation, then everything will be fine," I think when you live that way, it's very frustrating. And I realized the problems are deeper than that. And some of the problems the United States is facing are problems that exist all around the world. I mean the urban rural problems: it's a piece of modernization. It doesn't just affect our country, it affects many countries.

Garnette Cadogan: You know, we've been speaking about land, God, country, Christianity, urbanity, and in this book, a lot of it is packed in through this absolutely wonderful man, Eric, and his family. Part of what makes it compelling and illuminating is we get a chance to understand so much through this wonderful, generous, and beautiful man, Eric. For those who haven't read it yet, tell us about Eric, and why Eric was so crucial to understanding in so much of what you understood, and also some of the changes that you went through.

Marie Mutsuki Mockett: He's a Christian from Pennsylvania. He’s a white man who’s never been to college, but has a genuine intellectual curiosity, although not immediately apparent in a way that would register to us. Because we're at an event that's hosted by bookstore. So when we think of intellectual curiosity, probably the first thing that any of us would do would be to reach for a book, right? That's not what he would do. He wouldn't reach for a book, he would find someone to talk to. He's a person who is very much about the lived experience. But he was very open to asking questions and trying to understand other people's experiences and how the world works, and he was very concerned.

He was the person who told me in early 2016 that he thought that Trump would probably win, when none of us thought that this was possible. And he said this is because we don't understand each other at all. And he's a very open-hearted, very generous person. And you see him change over the course of the book.

He called me the other day. He said, "I've been hearing a lot about violence against Asian Americans." He's met a couple of my friends. He wanted to know, "Are they all right?" And then he said, "I just want you to know that we talk about racial justice all the time in church," because of course, that's the way that he processes life's difficult questions: through church. And I was kind of moved by that, because one of the points that American Harvest makes is that these difficult questions don't get talked about in church. And he said, "I just want you to know this is something that we talk about." So you see him really develop and change as a result of his exposure to me and to seeing how I move through space versus how he moves through space. And it's a big leap of imagination for people to understand that other people have other experiences that are legitimate and real. It seems to be one of the most difficult things for people to understand, but he really made a great effort to do that. And I think that’s kind of extraordinary.

***

Purchase American Harvest from City Lights Bookstore.

youtube

#Marie Mutsuki Mockett#Garnette Cadogan#City Lights LIVE#author interviews#city lights bookstore#graywolf#nonfiction#american harvest#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Book Review: 'American Harvest: God, Country, and Farming in the Heartland' by Marie Mutsuki Mockett

Book Review: ‘American Harvest: God, Country, and Farming in the Heartland’ by Marie Mutsuki Mockett

Review by Jake Meador, who is the editor in chief of Mere Orthodoxy. He is the author of In Search of the Common Good: Christian Fidelity in a Fractured World (InterVarsity Press). He lives in Lincoln, Nebraska with his wife and four children.

Things are never as difficult as they appear; they are always far more difficult.” A friend of mine once heard this bit of advice from his professor. And…

View On WordPress

0 notes